ABSTRACT

We tested three compounds for their ability to inhibit the RNase H (RH) and polymerase activities of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase (RT). A high-resolution crystal structure (2.2 Å) of one of the compounds showed that it chelates the two magnesium ions at the RH active site; this prevents the RH active site from interacting with, and cleaving, the RNA strand of an RNA-DNA heteroduplex. The compounds were tested using a variety of substrates: all three compounds inhibited the polymerase-independent RH activity of HIV-1 RT. Time-of-addition experiments showed that the compounds were more potent if they were bound to RT before the nucleic acid substrate was added. The compounds significantly inhibited the site-specific cleavage required to generate the polypurine tract (PPT) RNA primer that initiates the second strand of viral DNA synthesis. The compounds also reduced the polymerase activity of RT; this ability was a result of the compounds binding to the RH active site. These compounds appear to be relatively specific; they do not inhibit either Escherichia coli RNase HI or human RNase H2. The compounds inhibit the replication of an HIV-1-based vector in a one-round assay, and their potencies were only modestly decreased by mutations that confer resistance to integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs), nucleoside analogs, or nonnucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTIs), suggesting that their ability to block HIV replication is related to their ability to block RH cleavage. These compounds appear to be useful leads that can be used to develop more potent and specific compounds.

IMPORTANCE Despite advances in HIV-1 treatment, drug resistance is still a problem. Of the four enzymatic activities found in HIV-1 proteins (protease, RT polymerase, RT RNase H, and integrase), only RNase H has no approved therapeutics directed against it. This new target could be used to design and develop new classes of inhibitors that would suppress the replication of the drug-resistant variants that have been selected by the current therapeutics.

KEYWORDS: HIV-1, RNase H, active site inhibitors, magnesium chelating, structure

INTRODUCTION

While significant progress has been made in the treatment of HIV-1 infections, drug resistance continues to be a problem, and new drugs will be a needed for the foreseeable future. Generally speaking, the most effective anti-HIV drugs have targeted three of the four enzymatic activities of HIV. There are FDA-approved drugs that target protease (PR), integrase (IN), and the polymerase activity of reverse transcriptase (RT). However, despite serious efforts, there are no approved drugs that target the RNase H (RH) activity of RT (1–7).

After infection of a cell by HIV-1, the single-strand RNA genome (there are two copies of the viral RNA in HIV virions) must be converted into a linear double-stranded DNA. The ends of this linear viral DNA are the substrates for integration into the host cell DNA; therefore, the ends of the viral DNA must be appropriate substrates for the viral enzyme IN. HIV-1 RT carries out the conversion of the single-stranded RNA into double-stranded DNA. RT is a heterodimer, comprising a larger p66 subunit and a smaller p51 subunit. The p66 and p51 proteins are initially synthesized as part of the Gag-Pol polyprotein and are produced, in the maturing virion, by cleavage of Gag-Pol by the viral enzyme PR. The p66 subunit of RT contains the DNA polymerase active site; the polymerase can use either RNA or DNA as the template. Like most DNA polymerases, RT needs a primer to initiate DNA synthesis. The p66 subunit also contains an RH activity, which degrades the RNA strand only if the RNA strand is in an RNA-DNA heteroduplex, leaving a 5′ phosphate group after cleavage. The p51 subunit does not have any enzymatic activity and appears to play a structural role. Structural analyses of RT with bound nucleic acid template/primers show that the 3′ end of the primer strand is preferentially bound at the polymerase active site. The double-stranded portion of the nucleic acid spans the region between the two active sites, which are approximately 17 nucleotides (nt) apart. The template strand passes near the RH active site. If the template strand is RNA, RH can interact with it and cleave the phosphate backbone (for a current review, see reference 8).

Viral RNA is sense (plus) strand. Once the polymerase has begun copying the RNA genome, generating minus-strand viral DNA and creating an RNA-DNA duplex, RH is able to cleave the RNA template. Although the RH preferentially cleaves at some positions in an RNA-DNA duplex, most of the cleavages of the duplex are relatively nonspecific. However, there are specific RH cleavages that play an essential role in the synthesis of the linear viral DNA. The polymerase activity of RT requires a primer, and RH generates the RNA primers that are used to initiate synthesis of the second viral DNA strand (plus strand). One of these plus-strand primers is particularly important, the polypurine tract (PPT) primer. There is a second related sequence called the central PPT (cPPT), which is in the IN-coding region; this second PPT presumably undergoes similar processing. The RH cleavage at the 3′ end of the PPT sequence in the RNA-DNA hybrid determines the site where plus-strand DNA synthesis is initiated. The remaining PPT sequence appears to be resistant to RH cleavage (possibly due to its structure), and it is not certain whether the cleavage at the 5′ end of the PPT is really necessary. Once the cleavage at the 3′ end of the PPT occurs, the resulting RNA primer can be used to initiate second-strand DNA synthesis. RH is also responsible for the site-specific cleavage of the junction between the PPT RNA primer and the newly created DNA strand; this cleavage determines the upstream end of the viral DNA. Lastly, RH cleaves near the junction of the tRNA Lys3 primer (which serves as the primer for minus-strand DNA synthesis) and the viral DNA. This cleavage takes place 1 nucleotide from the RNA-DNA junction, leaving a riboA attached to the 3′ end of the minus-strand DNA (8).

Compounds referred to as “integrase strand transfer inhibitors,” or INSTIs, that selectively interfere with the second, or strand transfer, step of integration have been developed. INSTIs chelate the two magnesium ions that are present at the IN active site, and other parts of the compounds interact with both IN and the 3′ ends of the viral DNA. Both HIV-1 RH and HIV-1 IN belong to the functionally diverse superfamily of DDE(D) nucleotidyltransferases. These enzymes all have two magnesium ions bound at their active sites, which interact with the acidic amino acids of the DDE(D) motif. We have previously reported 4-amino-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,8-naphthyridine-containing compounds that were designed to inhibit IN and showed that some of the compounds could also inhibit the RH and polymerase activities of RT (9). Based on these promising results, we developed a series of compounds that were specifically intended to bind to the RH active site. These compounds are based on the aforementioned INSTI scaffold, which consists of a 1,8-naphthyridine ring with a chelating motif formed from a 1-N-hydroxyl group, the 2-oxo group, and the 8-naphthyridine nitrogen. However, the new compounds lack the 2′,4′-difluorobenzyl moiety, which was, in the parental compounds, linked via a carboxamide to the 3-position of the heterobicyclic core. The function of the modified benzyl ring is to stack with the penultimate dC at the 3′ end of the incoming viral DNA when the compounds are bound to HIV-1 IN. Here, we report that three compounds, XZ456, XZ460, and XZ462, interfere with the RH and polymerase activities of HIV-1 RT in enzymatic assays and block HIV-1 replication in cultured cells. We also present a high-resolution crystal structure which demonstrates that one of the compounds, XZ462, is bound at the RH active site.

RESULTS

The compounds inhibit the replication of an HIV-1 vector in a one-round assay.

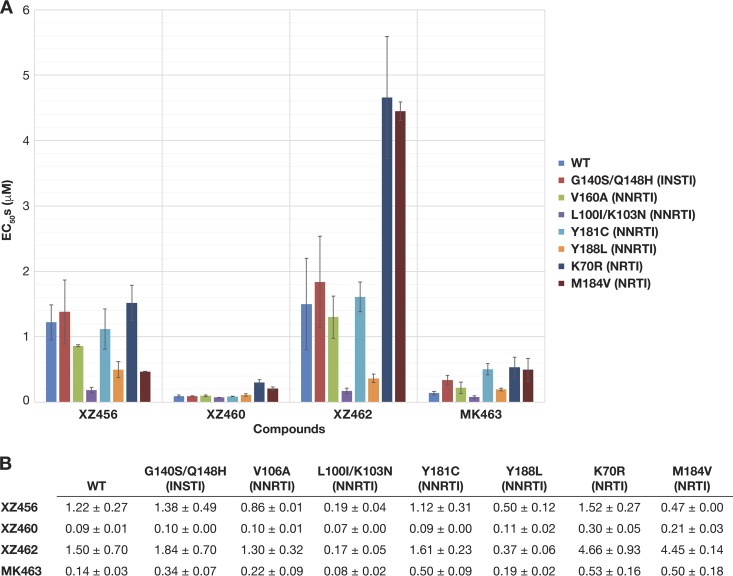

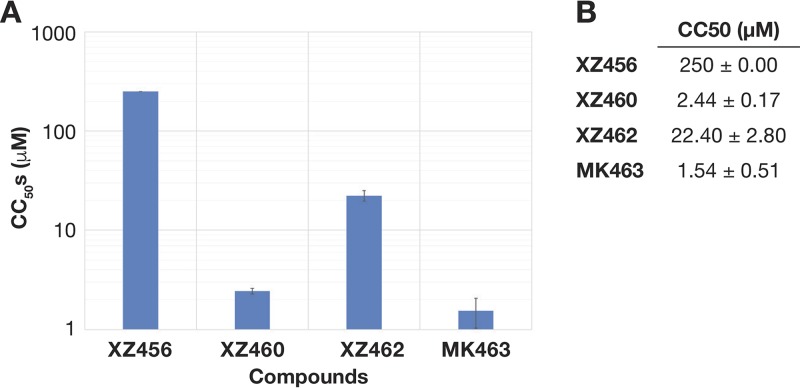

The compounds XZ456, XZ460, XZ462, and MK463 (Fig. 1), which is a reference Merck compound (patent number WO2008010964), were tested for their abilities to inhibit the replication of HIV-based vectors in one-round viral replication assays. XZ456 and XZ462 weakly inhibited wild-type (WT) HIV-1, with 50% effective concentrations (EC50s) of 1.22 μM and 1.5 μM, respectively, while XZ460 and MK463 were more potent at inhibiting WT HIV-1 (EC50s of 94 nM and 139 nM, respectively) (Fig. 2A and B). In parallel, these compounds were also tested for toxicity by using a sensitive assay that measures the level of ATP in treated cells. Many RH inhibitors are toxic to cells, presumably because the compounds can bind to host cellular enzymes that belong to the nucleotidyltransferase superfamily. XZ456 had no detectable toxicity, with a 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of >250 μM, while XZ462 had minor toxicity, with a CC50 of 22.4 μM, which is a toxicity level similar to that seen in several FDA-approved nonnucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTIs). XZ460 and MK463 showed some toxicity, with CC50s of 2.44 μM and 1.54 μM, respectively (Fig. 3A and B). Thus, XZ456 had a therapeutic index of >200, while the therapeutic indexes for XZ460 and XZ462 were 26 and 15, respectively, which are better than that of MK463, which is 11 (6).

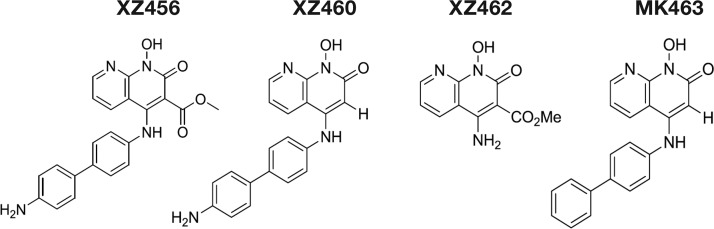

FIG 1.

Structures of the compounds. Depiction of the chemical structures of XZ456, XZ460, XZ462, and MK463.

FIG 2.

Antiviral activities of XZ456, XZ460, XZ462, and MK463 against HIV-1 vectors that carry well-known INSTI, NNRTI, and NRTI resistance mutations. (A) Graphical representation of the EC50s (μM) of XZ456, XZ460, XZ462, and MK463 against WT HIV-1 and several INSTI-, NNRTI-, and NRTI-resistant mutants, represented in different colors. The EC50s were measured using a single-round infection assay. Error bars represent standard deviations of results of independent experiments, n = 4. (B) Table showing the numerical values of the EC50s ± standard deviations.

FIG 3.

Cytotoxicities of XZ456, XZ460, XZ462, and MK463. (A) Graphical representation of the cellular cytotoxicities of XZ456, XZ460, XZ462, and MK463. The CC50 values (μM) of the compounds were measured by monitoring the ATP levels in HOS cells. Error bars represent standard deviations of results of independent experiments, n = 4. (B) Table showing the numerical values of cellular cytotoxicities of the compounds ± standard deviations.

If this series of compounds selectively targets the RH active site of HIV-1 RT, then HIV-1-resistant mutants that affect the potency of INSTIs, NNRTIs, and NRTIs should not cause a significant change in the potency of the compounds relative to WT HIV-1. We first tested the ability of these compounds to inhibit the INSTI-resistant G140S/Q148H mutant. XZ456, XZ460, and XZ462 inhibited the G140S/Q148H double mutant with efficacies similar to that of WT HIV-1, and the G140S/Q148H double mutant displayed a 2-fold drop in susceptibility to MK463 compared to WT HIV-1 (Fig. 2A and B). This initial screen suggests that these compounds do not target HIV-1 IN. Previous assays done with the FDA-approved INSTIs raltegravir and elvitegravir showed 475-fold and 891-fold losses in potency, respectively, with this particular resistant double mutant. We also tested these compounds against the well-known NNRTI-resistant V106A, Y181C, Y188L, and L100I/K103N mutants. XZ456, XZ460, and XZ462 inhibited these NNRTI-resistant mutants with antiviral activities equivalent to that against WT HIV-1; however, there was, in some cases, an apparent increase in potency. We have no good explanation for this result. MK463 inhibited all of the NNRTI-resistant mutants with efficacies similar to that against WT HIV-1, except for the Y181C mutant, which caused a minor drop in susceptibility. Lastly, we tested the compounds against the NRTI-resistant M184V and K70R mutants to see if there was any evidence that the compounds could bind at the polymerase active site. XZ456 and XZ460 both inhibited these NRTI mutants with efficacies similar to their antiviral activities against WT HIV-1. Conversely, the NRTI-resistant mutants caused a 3- to 4-fold reduction in susceptibility to XZ462 and MK463 (Fig. 2A and B). Although the data obtained with the viral mutants suggest that XZ462 could be interacting with the polymerase active site, both the biochemical data and the crystallographic data (presented below) show that XZ462 binds to and inhibits RH. Even if XZ462 binds at both the polymerase active site and the RH active site, the most potent compound, XZ460, was not significantly affected by the mutations we tested.

Crystal structure of XZ462 in a complex with HIV-1 RT.

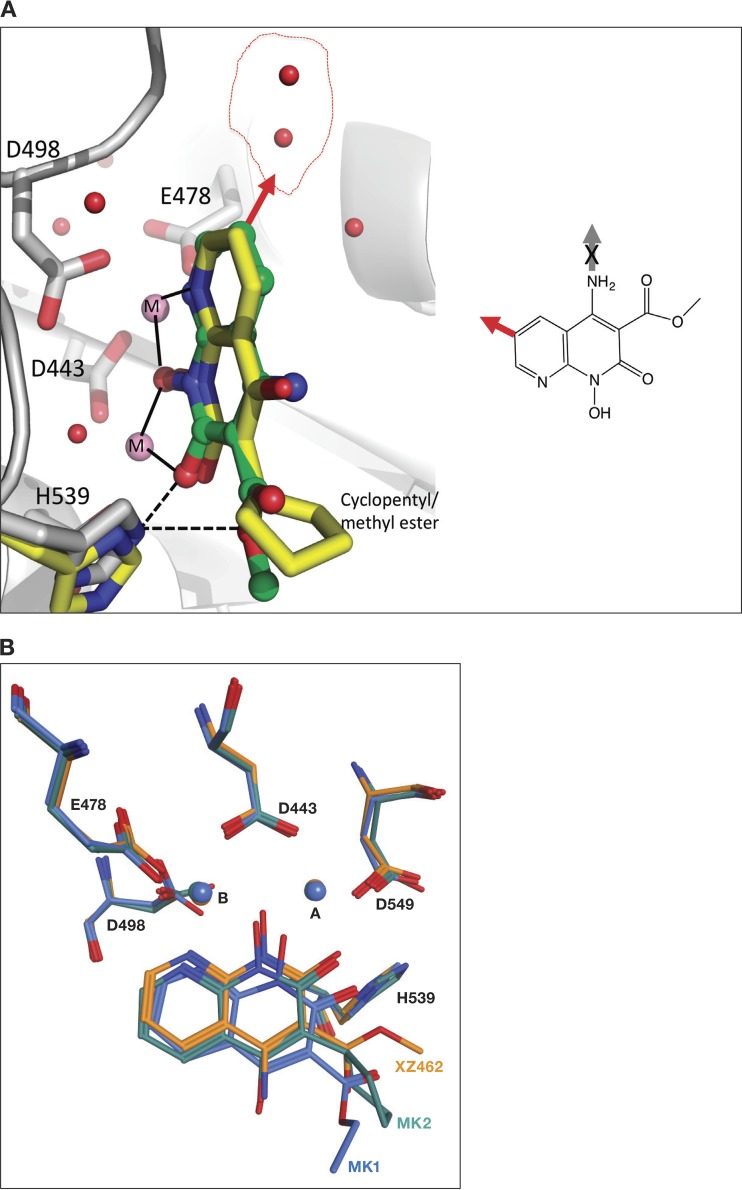

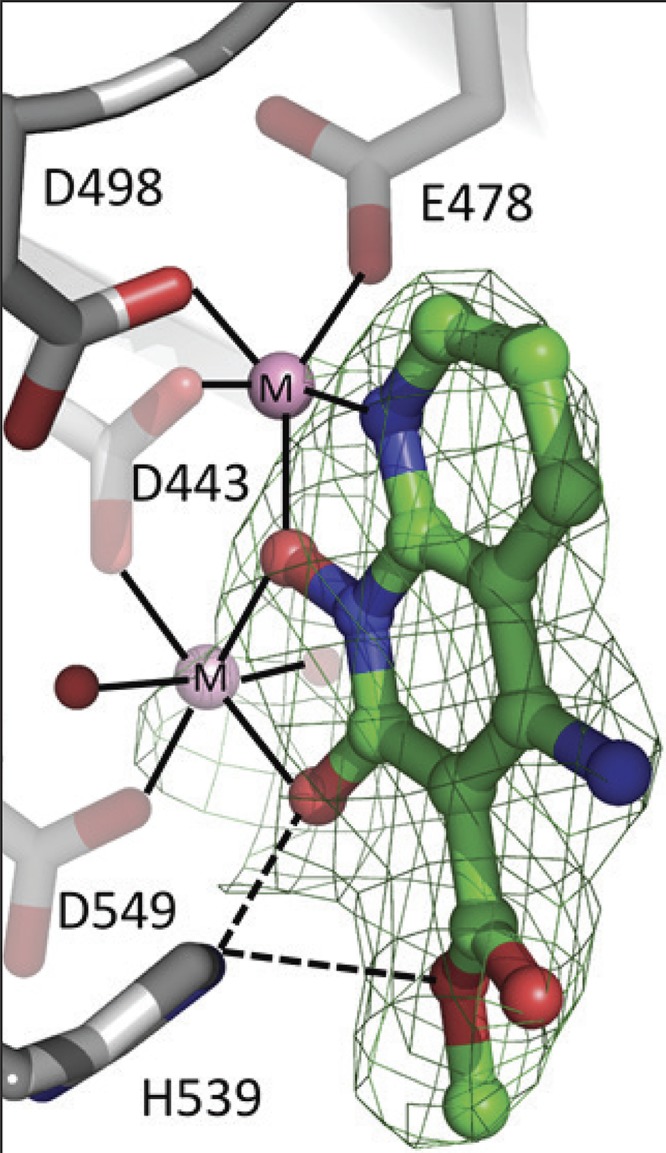

To better understand the interaction between the RH inhibitors and the RH active site of HIV-1 RT, crystals of HIV-1 RT were grown in a complex with the NNRTI drug rilpivirine (RPV) (10). RPV, which binds in a hydrophobic pocket about 10 Å from the polymerase active site, helps to prepare crystals that diffract to high resolution (11). Because the RPV was bound ∼50 Å from the RH active site, binding did not affect the structure of the RH domain, nor should it affect the binding of the RH inhibitors. Preformed RT-RPV crystals were soaked in solutions that contained each of the three RNase H inhibitors. When the structures of the RT complexes in the three sets of soaked crystals were solved, only the RT that was soaked with XZ462 showed the electron density for a bound inhibitor. The XZ462 complex structure was solved at a resolution of 2.2 Å, making it possible to unambiguously position the inhibitor at the RH active site (Fig. 4; Table 1). As expected, the inhibitor chelates the two magnesium ions at the active site, which are coordinated by the RH active site residues D443, E478, D498, and D549. The binding of XZ462 is similar to the binding of MK1 and MK2 seen in previously solved structures (12). The inhibitor is bound in close proximity (∼4.5 Å) to residues G444, S499, Q500, A538, and H539. Superposition of the RT-XZ462 and RT-MK2 crystal structures shows structural differences in the contacts made by different constituents that protrude from the 3′ position of the naphthyridine pharmacophore. The methyl ester modification of XZ462 and the cyclopentyl group of MK2 occupy a similar spatial orientation; however, the methyl ester group of XZ462 has a hydrogen-bonding interaction with conserved residue H539 of RH (Fig. 5A). In addition, superposing the RT-MK1 structure with the corresponding RT-XZ462 and RT-MK2 structures suggests that the longer ethyl ester of MK1 likely prevents it from interacting with H539 of RH. In the crystal structure, this functionality extends away from the RH active site (Fig. 5B). There were, in the RT-XZ462 structure, several ordered water molecules near the RH active site. These ordered water molecules were not seen in the previously solved RH inhibitor structures. The methyl ester modification of XZ462 interacts with two water molecules within ∼3.15 Å, while three water molecules are located within ∼4 Å of the 6′ position on the naphthyridine core (Fig. 5A, red arrow), and one water molecule is 3.8 Å away from the 7′ position of the naphthyridine ring (data not shown). The close proximities of these water molecules to the inhibitor suggest that there are chemically feasible substitutions of the naphthyridine ring that could mimic the bound water molecules and enhance the interactions of the compounds with the RH domain (Fig. 5A, red arrow). Lastly, the RT-XZ462 structure shows that there are two water molecules that interact with the magnesium A ion, giving it 6 coordinating ligands; the other magnesium ion (B) has 5 coordinating ligands (Fig. 5A), which was not observed in the previously solved RH inhibitor structures (12).

FIG 4.

Relative position of XZ462 in the RNase H active site of HIV-1 RT, showing contacts with residue H539. The crystal structure of XZ462 bound to the RNase H active site of HIV-1 RT shows the contacts made between XZ462 (green) and the RNase H active site residues (gray). The chelating motif of the hydroxylnaphthyridine scaffold binds the magnesium ions (shown in pink), while the methyl ester group of XZ462 forms a hydrogen bond with H539 of HIV-1 RT. Several ordered H2O molecules are shown in red.

TABLE 1.

Crystallographic data and refinement statistics for HIV-1 RT-XZ462 complex

| Parametera | Value for RT-XZ462b |

|---|---|

| PDB ID | 6ELI |

| Data collection date | 18 November 2015 |

| Data collection source | CHESS F1 |

| Data collection statistics | |

| Space group | C2 |

| Cell parameters | 163.12, 72.92, 109.25 Å; 90, 101.36, 90° |

| Resolution (highest-resolution shell) (Å) | 70.7–2.20 (2.25–2.20) |

| Rmerge (%) | 0.06 (0.82) |

| CC1/2 | 0.997 (0.623) |

| No. of unique reflections | 63,950 (4,480) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.9) |

| Multiplicity | 5.1 (5.0) |

| I/σ(I) | 12.3 (1.9) |

| Mosaicity | 0.51 |

| Wilson B (Å2) | 45.9 |

| Refinement statistics | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 53–2.2 |

| Cutoff criteria | F < 0 |

| No. of reflections (R-free set) | 63,981 (1,932) |

| Rwork/Rfree | 0.184/0.221 |

| No. of atoms refined | 8,407 |

| Stereochemistry (RMSD) | |

| Bond length (Å) | 0.005 |

| Bond angle (°) | 0.842 |

, where ai and bi are the intensities of unique reflections merged across the observations, and ā and b̄ are their averages; where li(hkl) and Ī(hkl) are intensity of reflection i and average intensity, respectively; RMSD, root mean square deviation; I, intensity; σ, standard deviation.

Values in parentheses are for the highest-resolution shell, 2.25–2.2 Å.

FIG 5.

Superposing the crystal structures of XZ462 and MK2 in the RNase H active site of HIV-1 RT. (A) The crystal structures of XZ462 (green) and MK2 (yellow) in the RNase H active site of HIV-1 RT were superposed to show the different contacts between the inhibitor and residues that comprise HIV-1 RT RNase H active site and how the chelating motif interacts with the two magnesium ions (pink). Superposing both structures revealed that XZ462 (green) forms a hydrogen bond interaction with HIV-1 RT H539 (gray); MK2 (yellow) does not interact with its respective H539 (yellow). The chemical structure of XZ462 is shown in the inset. It is flipped relative to the structure shown in Fig. 1. The red arrow pointing from the 6′ position of the XZ462 pharmacophore indicates sites where modifications could be made. The red arrow in the larger figure represents the same 6′ position and indicates where modifications could be made based on the contacts with water (depicted as red spheres inside the red circle). (B) Comparison of the binding contacts of XZ462, MK1, and MK2 in the HIV-1 RT RH active site. The crystal structures of XZ462 (orange), MK1 (blue), and MK2 (green) in their respective HIV-RT RH active sites were superposed. HIV-1 RT RH active site residues D443, E478, D498, and D549, as well as H539 and the magnesium ions A and B, are also shown.

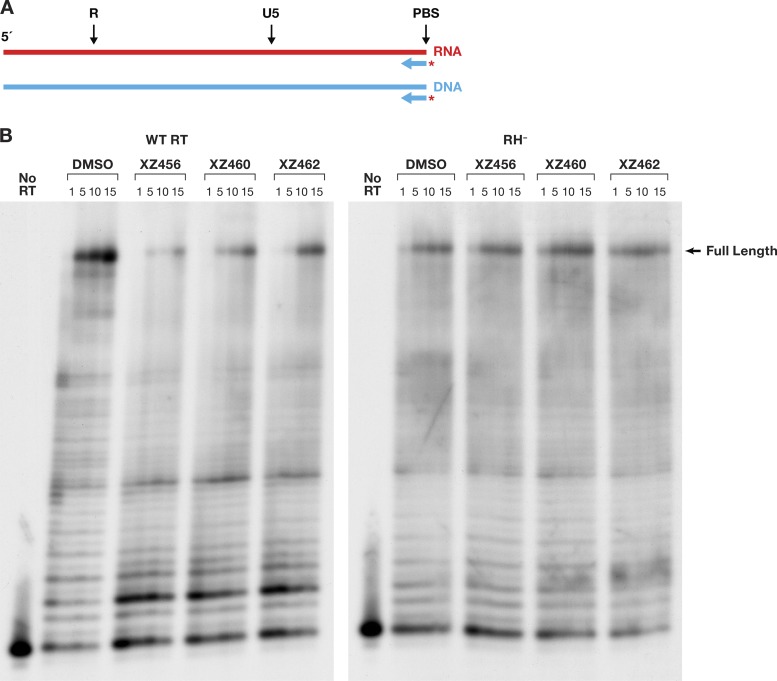

Polymerase-independent RH assays.

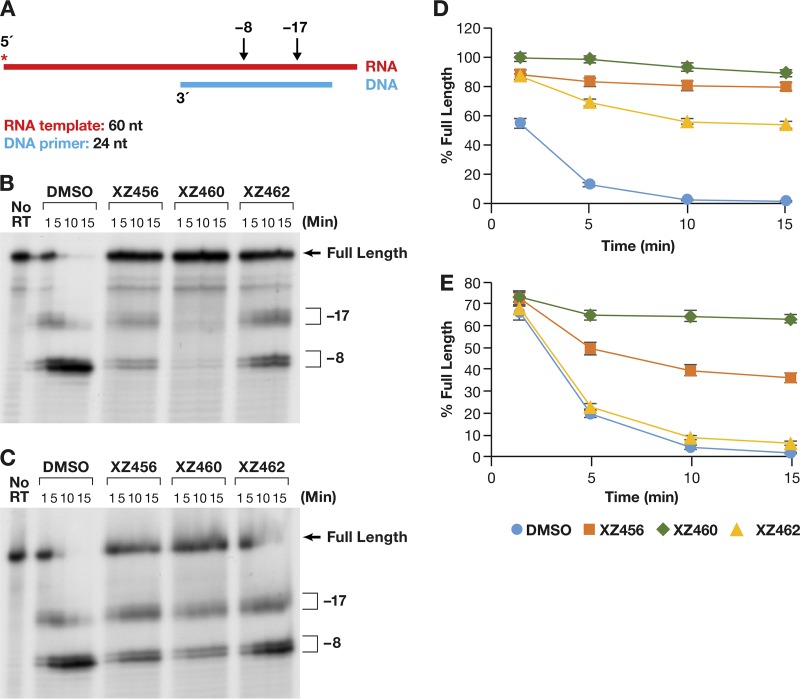

Polymerase-independent RH assays do not contain deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), and there is, in these assays, no primer extension by the polymerase. However, RT is free to move along the template/primer (T/P) substrate. The first substrate we tested falls into a class of substrates that are designated to be DNA 3′end-directed substrates (13–16). In our version of this assay, the 5′ end of the RNA was labeled and then annealed to a shorter DNA oligonucleotide. This creates a recessed end with the 5′ end of the RNA extending past the 3′ end of the DNA primer (Fig. 6A). This substrate has been previously described (17). The results of typical assays are shown in Fig. 6B and C. Figure 6B shows a time course in which the RT and the compounds were allowed to interact before the radioactive T/P was added to the reaction. Because the compounds were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), the reaction mixture in the control lane had the same amount of DMSO added, but with no compound. As can be seen in Fig. 6B, the RH of HIV-1 RT generated, from this substrate, two families of RNA fragments designated −17 and −8. These are described in more detail in Discussion. As seen in Fig. 6B, the compounds interfered with the cleavages that give rise to both the −17 and −8 products. Phosphoimager analysis makes it possible to quantitate the results; the graph is shown in Fig. 6D. “Percent full-length” (shown on the y axis) indicates the amount of the starting full-length RNA that remained at a given time. The DMSO control lane indicates that in the absence of an inhibitor, RH cleaved the substrate efficiently. The compounds prevented this cleavage (to various degrees), and significantly more full-length RNA remained (Fig. 6D). XZ460 is the most potent of the tested inhibitors, followed by XZ456 and then XZ462.

FIG 6.

Effects of the compounds on RH cleavage (3′-end-directed cleavage). (A) Overall structure of the template/primer (T/P) used for the DNA 3′-end-directed RH assay. Red, RNA; blue, DNA. The asterisk indicates the 32P end label. The locations of the RH cleavages shown in the figure are indicated above the nucleic acid. (B) Cleavages when RT and compounds were allowed to interact before the T/P was added. The control lane (no RT) indicates the size of the intact, full-length RNA. The DMSO lanes had no inhibitor present, while the other lanes had a 10.0 μM concentration of the indicated compound in the reaction. The sizes of the cleavage fragments are based on their distance from the 3′ end of the DNA oligonucleotide located at the polymerase active site. −17 is approximately the distance (in bp) between the polymerase active site and the RH active site. (C) Cleavages when compounds and T/P were mixed together first and the addition of RT was used to initiate the reaction. (D) Graphic representation of the Phosphoimager data of the RH cleavage fragments in panel B. The amount of the full-length RNA template present at a given time was measured as a percentage of the total amount of cleaved and uncleaved RNA in the reaction. For all of the polymerase-independent RH assays, the same amount of T/P and the same amount of RT was used, allowing direct comparisons to be made among the various assays. Differences in the extent of cleavage depends only on how well the RT can bind to the T/P and how well RH is able to cleave the RNA. The error bars represent standard deviations of results of individual experiments as calculated by Excel. n = 3. (E) Graphic representation of the Phosphoimager data of the RH cleavage fragments in panel C. The assay is similar to the assay described for panel D, except that the compounds and T/P are mixed together first. The reaction was initiated by the addition of the RT, so that the compounds and T/P competed for binding to RT. The error bars represent standard deviations of results of individual experiments as calculated by Excel. n = 3.

We then asked how the compounds behave when they are required to compete with the T/P for binding to RT. The reaction was initiated by the addition of RT to the reaction, which already contained the compound being tested (if any) and the labeled RNA-DNA. The pattern of RNA fragments (−17 and −8) produced by the RH was not altered in this reaction in comparison to reactions in which RT and the compounds were allowed to interact before the substrate was added (Fig. 6C). However, there were differences in the abilities of the compounds to inhibit RH. The order of the compounds' abilities to inhibit was still XZ460 > XZ456 > XZ462. However, in the competition assay, XZ462 had little impact on the extent of cleavage. XZ460 was slightly less effective in the competition assay than it was when it was able bind to RT without T/P being present. XZ456 was significantly less active in blocking RH cleavages in the competition assay than in the initial assay (Fig. 6E). This suggests that if T/P is already bound, it can compete with the compounds for binding to RT. We will revisit this question below in the section that discusses the effects of the compounds on polymerization by RT.

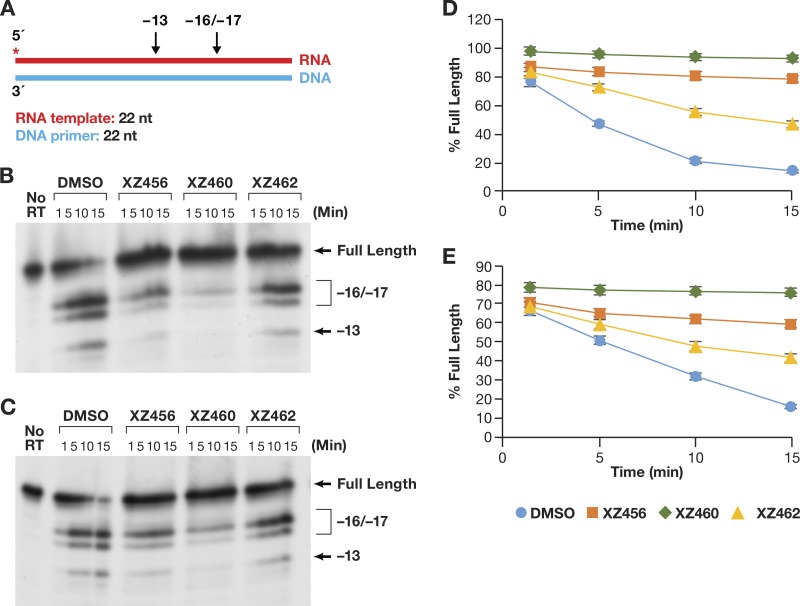

Another mode of RH activity has been designated RNA 5′ end directed (13–16, 18). In this case, a relatively short 5′-end-labeled RNA was annealed to a longer DNA fragment (Fig. 7A). The 5′ end of the RNA was recessed. It is unclear how the 5′ end of the RNA directs the positioning of the T/P, because if the RNA strand is cleaved, it must contact the RH active site. This means that the RNA strand must still be acting as the template. When the compounds and the RT were allowed to interact before the T/P was added, the amount of RH cleavage was much less than what was seen for the DNA 3′-end-directed T/P substrate (Fig. 7B), even in the DMSO control lane (see Discussion). However, the order of effectiveness of the compounds was the same (XZ460 > XZ456 > XZ462) (Fig. 7D). When the T/P and a compound were allowed to interact with RT at the same time (the reaction was initiated by the addition of RT), the pattern of cleavages remained the same (Fig. 7C) but the amount of cleavage was reduced (Fig. 7E). The inhibition curves were more tightly clustered than they were in the assays done with the DNA 3′-end-directed template.

FIG 7.

Effects of the compounds on RH cleavage (5′-end-directed cleavage). (A) Overall structure of the template/primer (T/P) used for the RNA 5′-end-directed RH assay. Red, RNA; blue, DNA. The asterisk indicates the 32P end label. The locations of the RH cleavages shown in the figure are indicated above the nucleic acid. (B) Cleavages when RT and compounds were allowed to interact before the T/P was added. The control lane (no RT) indicates the size of the intact, full-length RNA. The DMSO lanes had no inhibitor present, while the other lanes had a 10.0 μM concentration of the indicated compound in the reaction. The sizes of the cleavage fragments are based on their distance from the 5′ end of the RNA oligonucleotide located at the polymerase active site. −17 is approximately the distance (in bp) between the polymerase active site and the RH active site. (C) Cleavages when compounds and T/P were mixed together first and the addition of RT was used to initiate the reaction. (D) Graphic representation of the Phosphoimager results from panel B. The error bars represent standard deviations of results of individual experiments as calculated by Excel. n = 3. (E) Graphic representation of the Phosphoimager data from panel C. The error bars represent standard deviations of results of individual experiments as calculated by Excel. n = 3.

One of the last modes of polymerase-independent RH reactions has been designated internal cleavages (13, 19). The T/P is flush on both ends; there are no recessed ends (Fig. 8A). The pattern of cleavages seen in this assay (Fig. 8B and C) was similar to that seen for the RNA 5′-end-directed reaction (Fig. 7B and C). This indicates that the RT tends to bind with the 3′ OH group of the DNA strand located at the polymerase active site and with the RNA acting as the template strand. RT seems to be able to bind to this substrate more efficiently than the 5′-end-directed substrate. Again, the effect of the compounds on the amount of RH cleavage was greater when the compounds were allowed to bind to RT before the nucleic acid substrate was added (Fig. 8D) than when the compounds competed against the T/P (Fig. 8E). The pattern of cleavages was not altered (Fig. 8B and C), and the hierarchy of the compounds was the same (XZ460 > XZ456 > XZ462), whether the compounds were added before the T/P or at the same time.

FIG 8.

Effects of the compounds of RH cleavage (internal cleavage substrate). (A) Overall structure of the template/primer (T/P) used for the internal RH assay. Red, RNA; blue, DNA. The asterisk indicates the 32P end label. The location of the RH cleavages shown in the figure are indicated above the nucleic acid. (B) Cleavages when RT and compounds were allowed to interact before the T/P was added. The control lane (no RT) indicates the size of the intact, full-length RNA. The DMSO lanes had no inhibitor present, while the other lanes had a 10.0 μM concentration of the indicated compound in the reaction. The sizes of the cleavage fragments are based on their distance from the 3′ end of the DNA oligonucleotide located at the polymerase active site. −17 is approximately the distance (in bp) between the polymerase active site and the RH active site. (C) Cleavages when compounds and T/P were mixed together first and the addition of RT was used to initiate the reaction. (D) Graphic representation of the Phosphoimager data from panel B. The error bars represent standard deviations of results of individual experiments as calculated by Excel. n = 3. (E) Graphic representation of the Phosphoimager data from panel C. The error bars represent standard deviations of results of individual experiments as calculated by Excel. n = 3.

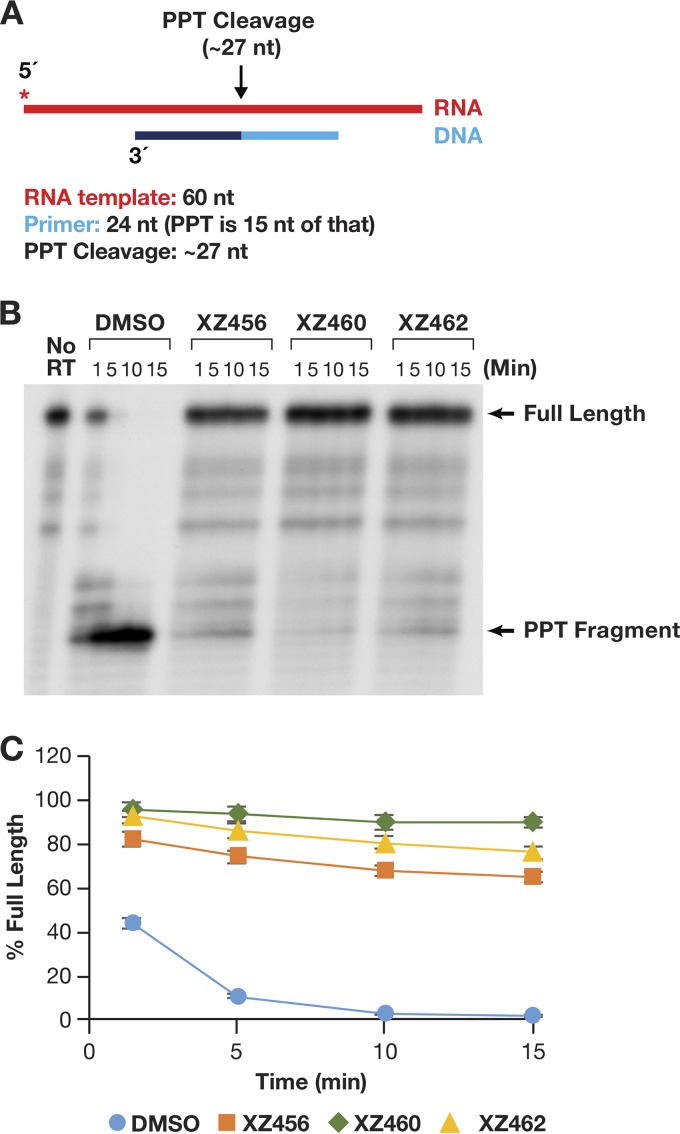

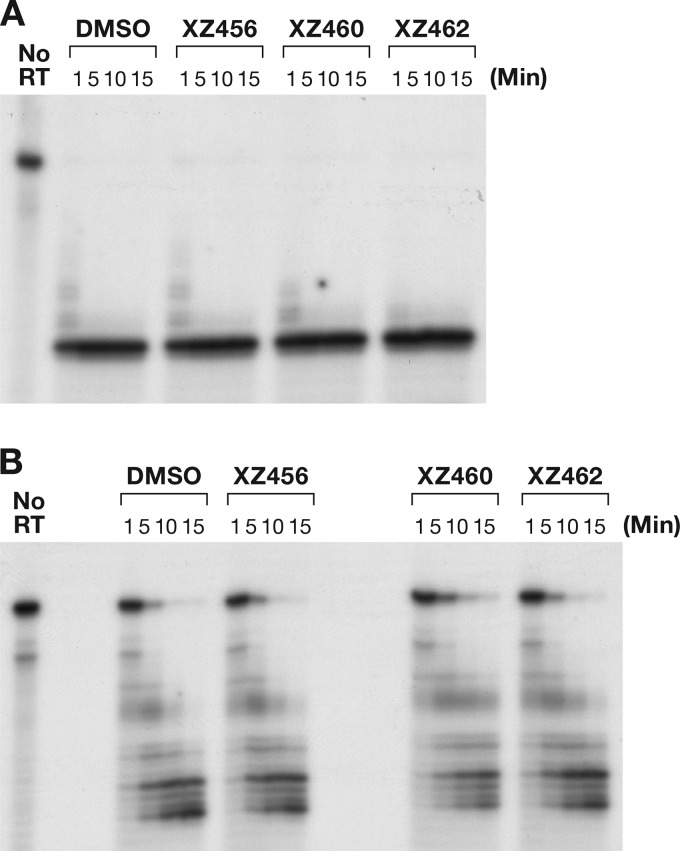

PPT cleavage.

As described in the introduction, there are a few cases in which specific RNA primers must be generated and/or removed by the activity of RH. The cleavage at the 3′ end of the RNA PPT is one of two RH cleavages that generate the RNA primer that is used to initiate second-strand viral DNA synthesis (8). As shown in Fig. 9A, an RNA-DNA heteroduplex was used to test cleavage at the PPT site. In the absence of any compound, the initial RNA product was a bit longer than the expected size (probably due to the 17-nt spacing between the polymerase and RH active sites). This fragment was quickly processed to the correct size (Fig. 9B). There was no evidence of further processing of the secondary RNA product to produce smaller-sized fragments. This supports the consensus that the PPT sequence is generally resistant to RH degradation. The compounds were all able to potently inhibit this specific RNA cleavage (Fig. 9B and C). In this assay, it appeared that XZ462 was somewhat more potent than XZ456 (Fig. 9C). However, the results were similar enough that it is difficult to be certain whether this apparent difference is significant.

FIG 9.

Effects of the compounds on RH cleavage (PPT substrate). (A) Overall structure of the template/primer (T/P) used for the PPT assay. Red, RNA; dark and light blue, DNA (the PPT region is dark blue). The asterisk indicates the 32P end label. The locations of the RH cleavages shown in the figure are indicated above the nucleic acid. (B) Cleavage products produced in the presence and absence of the compounds. The control lane (no RT) indicates the size of the intact, full-length RNA. The DMSO lanes had no inhibitor present, while the other lanes had a 10.0 μM concentration of the indicated compound in the reaction. The location of the PPT fragment is shown. (C) Graphic representation of the Phosphoimager data for the PPT substrate (see the text). The amount of full-length product was calculated as a percentage of the total amount of RNA in the assay. The error bars represent standard deviations of results of individual experiments as calculated by Excel. n = 3.

Polymerase-dependent RNase H activity and polymerase assays.

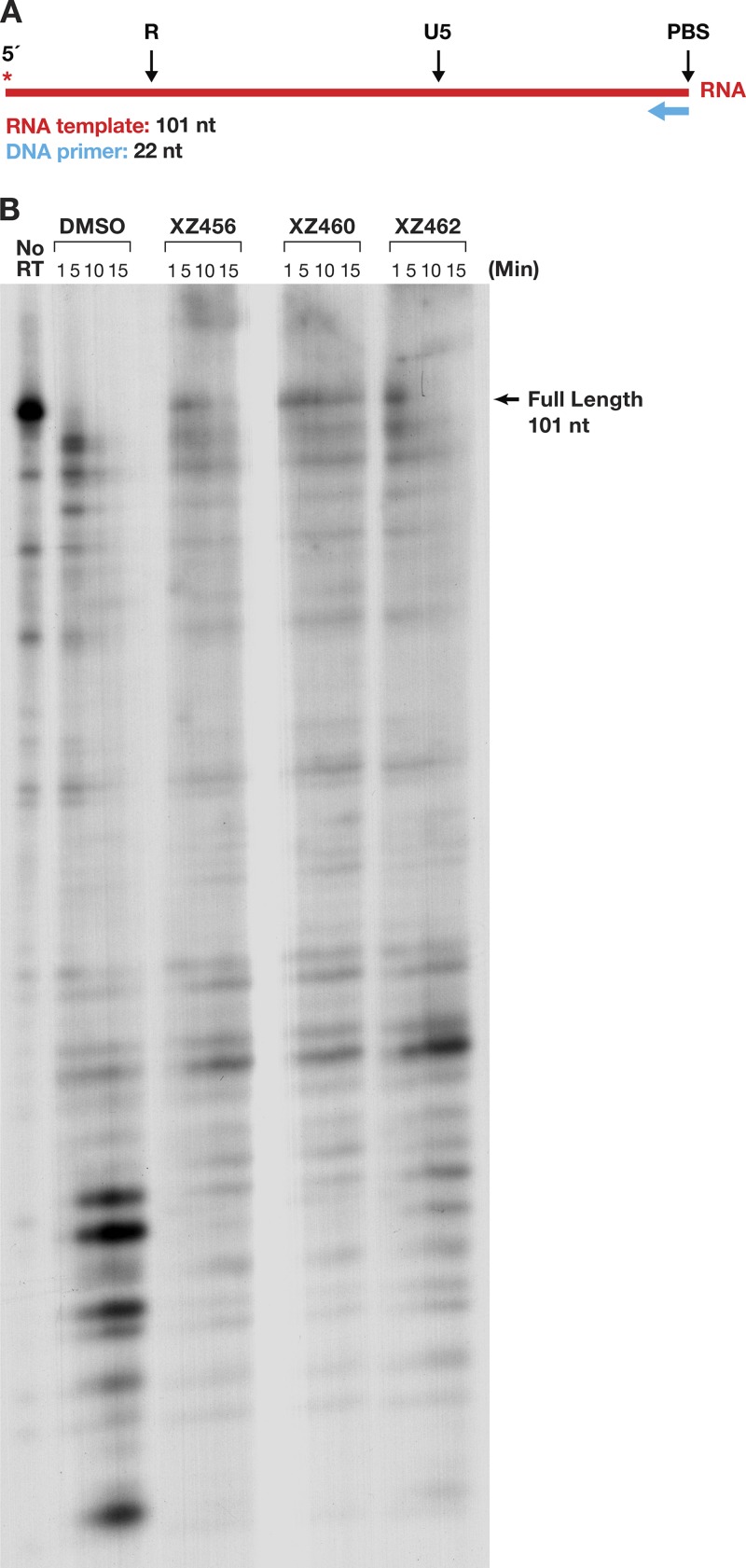

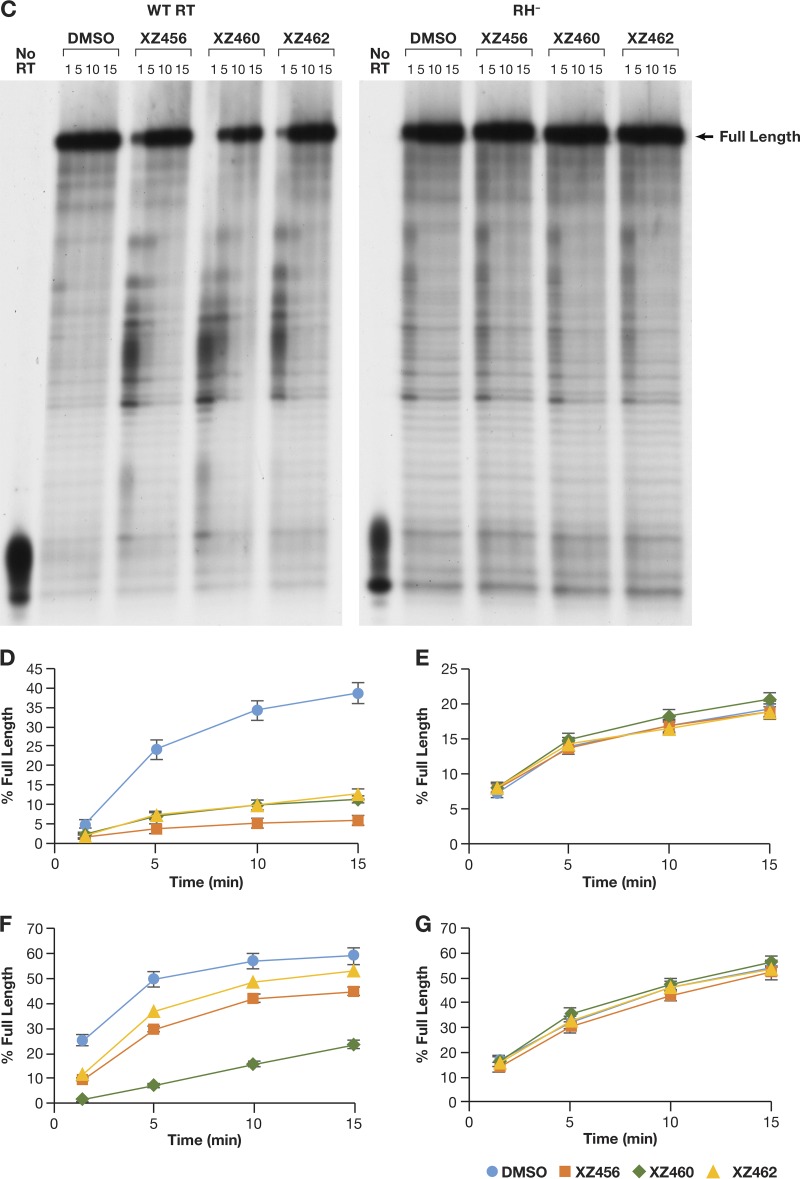

We prepared an RNA-DNA substrate in which the 5′-end-labeled RNA template strand was 101 nt long, and a small DNA oligonucleotide was annealed to this RNA (Fig. 10A). The RT was allowed to polymerize in the presence of a 20.0 μM concentration of each dNTP. As shown in the DMSO control lane (Fig. 10B), most of the prominent cleavages were made near the 5′ terminus of the RNA, where RT slowed down as it neared the end of the template. Because the cleavage pattern was complicated, we used the amount of residual full-length RNA to monitor the ability of the compounds to inhibit the RH activity and showed that the effectiveness of the compounds was XZ460 > XZ456 > XZ462 (Fig. 10B). The data also suggest that the polymerase activity of RT may have been affected by the compounds, a possibility that is addressed below.

FIG 10.

Effects of the compounds and polymerization on RH cleavages. (A) Template/primer (T/P) used for the polymerase-dependent RH assay. Red, RNA; blue, DNA. The asterisk indicates the 32P end label. (B) RH cleavages made when the RT was polymerizing (polymerase-dependent RH activity). The control lane (no RT) indicates the size of the intact, full-length RNA. The DMSO lanes had no inhibitor present, while the other lanes had a 10.0 μM concentration of the indicated compound in the reaction.

To test the effects of the compounds on the polymerase activity directly, the same RNA-DNA substrate was used, but in this case, the 5′ end of the primer DNA was labeled (Fig. 11A). This makes it possible to monitor the sizes of the DNA extension products that were produced by RT by using RNA as the template (RNA-dependent DNA polymerase [RDDP] assay). An RT that is deficient in RH activity (RH−) was included in this assay. This RH-defective RT has two of the active site aspartic acid residues changed to alanines (D443A/D549A). There are two magnesium ions at the RH active site of RT (designated magnesium A and magnesium B), and the aspartic acid residues D443 and D549 interact with the same magnesium ion at the RH active site (magnesium A). With both of the aspartic acids changed to alanine, RT should not be able to effectively bind magnesium A (13). The reason an RH− RT was included was to address the possibility that the compounds could interact with other parts of RT, including the polymerase active site (which also has two bound magnesium ions). The loss or distortion of the binding of one of the magnesium ions at the RH active site should decrease the ability of the compounds to bind at this location, which helped us determine whether the effect of the compounds on the polymerase activity was direct (through the polymerase active site) or indirect (through the RH active site). Figures 11B and D show the RDDP activity of the WT RT. The presence of the compounds significantly decreased the ability of the WT RT to extend the DNA primer. However, the polymerase activity of the RH− RT was similar in the presence or the absence of the compounds, indicating that the polymerase inhibition was due to the compounds interacting with the RH active site (Fig. 11B and E). Another substrate, a DNA-DNA nucleic acid, was also tested. The sequence of the DNA template was the same as that of the RNA template (Fig. 11A). This allowed us to determine the effects of the compounds on the DNA-dependent DNA polymerase (DDDP) activity of RT. The results were similar to those obtained in the RDDP assay. The compounds were able to inhibit the DDDP activity; in this case, their ability to inhibit the polymerase activity was the same as their ability to inhibit RH activity (XZ460 > XZ456 > XZ462) (Fig. 11C and 11F). As was seen with an RNA template, the polymerase activity of the RH− RT was not affected by the addition of the compounds (Fig. 11C and G).

FIG 11.

Effects of the compounds on polymerization on RNA and DNA templates. (A) T/Ps used for the polymerization assays. The long DNA and RNA templates have identical sequences and are identical in sequence to the template in Fig. 10A. The asterisk indicates the 32P end label. (B) RDDP assays done in the presence or absence of the compounds. The WT RT is shown on the left, while the RH− RT is on the right. “Full-length” indicates the extension of the primer to the end of the RNA template. The control lane (no RT) indicates the size of the DNA primer. The DMSO lanes had no inhibitor present, while the other lanes had a 10.0 μM concentration of the indicated compound in the reaction. (C) The assays are similar to those in panel B, except that the template is DNA (DDDP assay). (D) Graphic representation of the Phosphoimager data for the RNA-dependent DNA polymerase (RDDP) assay using the WT RT (panel B). The error bars represent standard deviations of results of individual experiments as calculated by Excel. n = 3. (E) Graphic representation of the Phosphoimager data for the RDDP assay using the RH− RT (D443A D549A) (panel B). The error bars represent standard deviations of results of individual experiments as calculated by Excel. n = 3. (F) Graphic representation of the Phosphoimager data for the DNA-dependent DNA polymerase (DDDP) assay using the WT RT (panel C). The DNA template has the same sequence as the RNA template. The error bars represent standard deviations of results of individual experiments as calculated by Excel. n = 3. (G) Graphic representation of the Phosphoimager data for the DNA-dependent DNA polymerase (DDDP) assay using the RH− RT (panel C). The error bars represent standard deviations of results of individual experiments as calculated by Excel. n = 3.

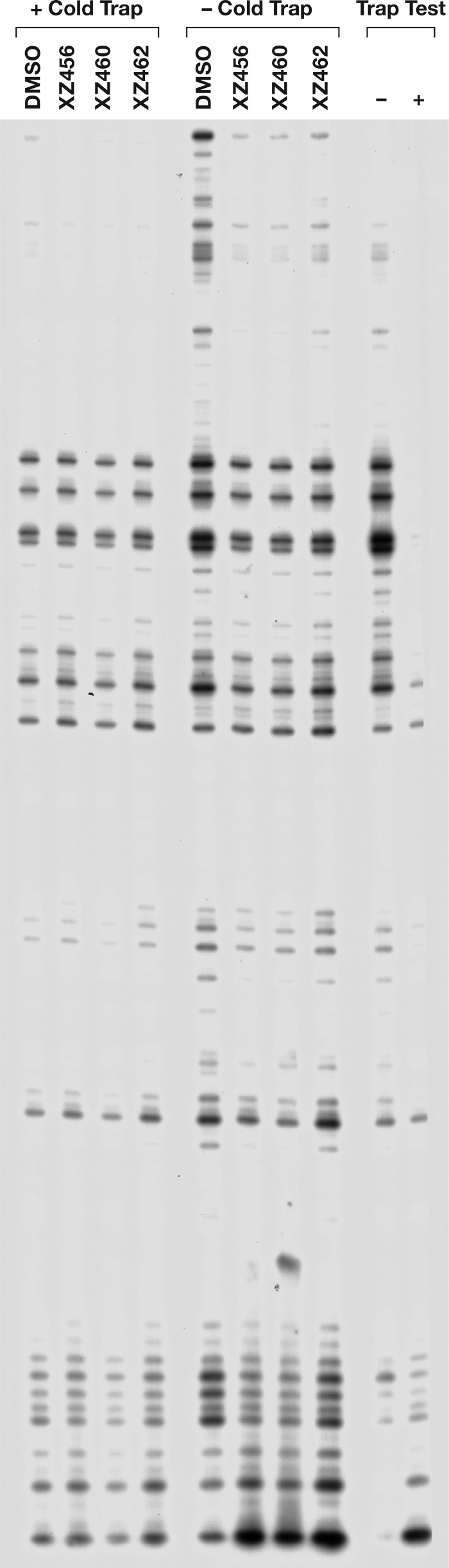

To ask whether the compounds could bind to RT if it was already bound to a T/P, we did an experiment in which RT was allowed to bind to the labeled T/P before the compounds were added. The reaction was initiated by the addition of the dNTPs and the inhibitors, in either the presence or absence of an unlabeled nucleic acid trap. This is basically a variation on a processivity assay. When a cold trap is present, whenever the prebound RT falls off the labeled T/P, it will likely bind to the unlabeled nucleic acid trap (which is present in excess) rather than rebinding to a labeled T/P, and, as a consequence, all of the polymerization of the labeled primer that occurs involves the prebound RT. Thus, if there is any measurable inhibition of the polymerase reaction, the inhibitor must have been able to bind to the complex of RT and the T/P. As shown in Fig. 12, none of the compounds had any measurable effect in the reactions that included the cold trap. Thus, the compounds were not able to inhibit the WT RT polymerization by a prebound RT to any significant extent, suggesting that if the T/P is already bound to the RT, the compounds are not able to bind to the RH active site (see Discussion).

FIG 12.

Effects of the compounds on polymerization in the presence of a cold trap. For each reaction, RT was allowed to bind to the T/P for 5 min in the reaction mixture. The reaction was initiated by the addition of a mixture containing dNTPs, the compound to be tested (10.0 μM in the final reaction buffer, or an equal volume of DMSO for the control lane), and either poly(rC)-oligo(dG) for the “+ trap” reactions or an equal volume of water for the “− trap” reactions. In the “Trap Test,” allowing the cold trap to bind to the RT before addition of the labeled T/P (+ lane) caused a marked reduction in the extension of the labeled primer compared to when no trap (−) is added. This indicates that the cold trap is able to sequester the RT from the labeled T/P.

General RH inhibition.

Because the compounds target the catalytic magnesium ions in the HIV-1 RH, there is a concern that the active sites of other RHs could be targeted as well. It has been reported that many RH enzymes share similar structures, even if the amino acid homologies are low. In human cells, two RH proteins (RNase H1 and RNase H2) are known, and loss of either one causes significant cell morbidity (20). The Escherichia coli RNase HI enzyme and the human RNase H2 enzyme were tested against the compounds. The substrate was the same as that used in Fig. 6A. Neither enzyme has an appended polymerase domain that would dictate how the RH would bind to the nucleic acid substrate, and both enzymes should cleave at many sites in the RNA strand in the heteroduplex. As seen in Fig. 13A and B, the compounds did not have a significant effect on the activity of either of these enzymes. This result supports the idea that the RH active site of HIV-1 RT is sufficiently different from the active sites of these two cellular enzymes that compounds can be developed as selective inhibitors of viral RH.

FIG 13.

The compounds do not affect the cleavage by E. coli RNase HI or human RNase H2. (A) RNA cleavage fragments generated by E. coli RNase HI; (B) fragments generated by human RNase H2.

DISCUSSION

Considering the multiple roles the RH of HIV-1 RT has in the generation of double-stranded DNA from the single-stranded RNA genome, it is an attractive target for anti-HIV therapy. The two magnesium ions bound at the RH active site are essential for the cleavage of the RNA phosphate backbone; compounds that interact with these ions can block the activity of the enzyme. However, there are large number of host enzymes for which catalysis depends on two bound two magnesium ions. To be useful as antiviral drugs, compounds should have chemical substituents that make them specific for the RH of HIV-1 RT. We examined the abilities of three compounds to interfere with the RH activity of HIV-1 RT and inhibit viral replication. The compounds are able to inhibit the replication of a one-round HIV vector in a cell-based assay. The hierarchy of potency is the same in the vector-based experiments and the in vitro assays. This, taken together with the fact that mutations that reduce the susceptibility of the vectors to several NNRTIs and IN inhibitors did not reduce the susceptibility of the vectors to the new compounds, supports the idea that the inhibitors inhibit viral replication by binding to the RH active site. It appears that the potency of one of the compounds, XZ462, was reduced by mutations in the polymerase active site of RT (K70R and M184V) that affect the susceptibility of viral replication to nucleoside analogs. It is possible that this compound may bind at both the polymerase and the RH active sites; however, this is the least potent of our compounds. Moreover, the crystal structure of XZ462 in a complex with HIV-1 RT shows that this compound can bind to the RH active site, and there is no structural evidence that it binds at the polymerase site. While all three compounds interfered with RH activity, they differed in their potencies, which probably reflects their abilities to bind at the RH active site.

From the known structures of RT bound to nucleic acid, it appears that for RH to cleave the RNA strand, the DNA strand must act as the primer and the RNA strand must act as the template. This configuration allows the RNA to be near the RH active site, where it could interact with the magnesium ions, and be cleaved. The 3′ OH group of the DNA primer is known to preferentially bind at the P site of the polymerase active site, in a configuration that allows an incoming dNTP to bind at the N site. In the absence of an inhibitor, RNA templates are cleaved, first at −17 (relative to the end of the DNA primer) and then at −8. The polymerase and RH active sites are approximately 17 bp apart, which explains why −17 is a favored site for cleavage. To carry out the −8 cleavages, RT must move relative to that T/P so that the 3′ end of the primer is closer to the RH site. The addition of the compounds to the RH assay did not alter the pattern of cleavage fragments that were produced by the RH of HIV RT. This would match the proposed model in which the compounds bind at the RH active site. If binding of the compounds interfered indirectly with the binding of the nucleic acid substrate and/or altered the ways in which RT bound the nucleic acid substrate, the compounds might have altered the cleavage pattern. Although the compounds did not alter the pattern of cleavage, they reduced the amount of cleavage; the potency of inhibition was XZ460 > XZ456 > XZ462.

The assays were repeated, but the reactions were initiated by the addition of RT, so that the compounds and T/P competed for binding to the RT. The pattern of RH cleavage products was not affected, but the ability of the compounds to inhibit the activity of RH was reduced. XZ462 is only modestly effective against HIV-1 RH in this assay. This indicates that XZ462 weakly competes with the T/P for binding to the RH active site. The T/P, which was present in the assay in excess, relative to the compounds, is known to bind to RT at nanomolar concentrations. HIV-1 RT, both in the virion and in these assays, is free to associate and disassociate from the T/P, providing an opportunity for the compounds to bind to the free RT. Although XZ460 can still inhibit RH in the competition assay, it is more effective if it is allowed to associate with RH before the T/P is added. The results obtained with XZ456 suggest that it is a better than XZ462 in terms of its ability to compete with the T/P but is less effective than XZ460.

The RNA 5′-end-directed substrate does not seem to be a favored one for RH cleavage. It is probable that the single-stranded portion of the DNA oligonucleotide affects the ability of RT to bind to the T/P in a way that facilitates RH cleavage. Inappropriate or ineffective binding would cause a reduction in the amount of RH cleavage. However, the ability of the compounds to inhibit RH cleavage was unaffected: XZ460 > XZ456 > XZ462.

It has been suggested that a substrate with blunt ends would not have a recessed end to influence how RT binds to the T/P (13, 14, 19). It has also been suggested that this would allow the RH to cleave at multiple places within the nucleic acid substrate (13, 14, 19). It is not clear, given the structure of RT around the polymerase active RT, just how it could bind to the internal portion of a long RNA-DNA duplex. We found, when using this type of substrate, that the pattern of cleavages was similar to that seen for the RNA 5′-end-directed assay. The cleavages were apparently not directed by RT binding internally on the substrate but rather by binding at the 3′ end of the DNA strand. The same pattern was seen in the RT-initiated reactions. The compounds, as before, inhibit in the order XZ460 > XZ456 > XZ462. This order was seen both in the experiments in which the compounds were allowed to bind to RT first and in the competition assays. However, the amount of RH cleavage is reduced for all samples relative to the first substrate (DNA 3′ end directed) we tested.

We also tested the impact of the compounds on one of the sites where specific cleavage is essential for HIV replication, the cleavage that gives rise to the PPT primer. The compounds were all able to inhibit this RH cleavage. Interestingly, the order of effectiveness was changed to XZ460 > XZ462 > XZ456. It has been suggested that the PPT region in an RNA-DNA heteroduplex has a somewhat distorted structure compared to a “normal” nucleic acid heteroduplex. The data suggest that the compounds might be interacting with this structure differently than they do with the other RT-substrate complexes.

All of the assays described above are polymerase independent, i.e., the RT is not polymerizing and the assay measures only RH activity. For RH cleavage by HIV-1 RT, the polymerase domain helps bind the T/P and orient it so that the RNA strand is in the proper location for cleavage to occur. In the polymerase-dependent RH activity assay, we used a long RNA template (101 nt) to examine the pattern of RH cleavages. There is evidence that there is little, if any, RNase H cleavage during active polymerization (13, 21, 22), although there have been suggestions that the nucleic acid can interact with both active sites simultaneously (1, 23). In agreement with the idea that there is little RH cleavage during polymerization, we found relatively few cleavages in the body of the long RNA template. The inhibition order was the same as in the 3′-end-directed assay: XZ460 > XZ456 > XZ462.

Because we know how well the compounds inhibit RH activity in assays using these substrates, the effects of the compounds on RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RDDP) and DNA-dependent DNA polymerase (DDDP) activities can be examined. One possible problem is that if the polymerase activity is inhibited, the compounds could be bound not only at the RH active site but also at some other site, possibly the polymerase active site, which has two bound magnesium ions. To address this issue, we prepared an RT variant with two of the RH active site acidic residues mutated (D443A/D539A). These two residues interact with the magnesium ion A in the RH active site, and their removal should affect the binding of this magnesium ion, which should reduce the ability of the compounds to bind at the RH active site. When tested with WT RT, all of the compounds inhibited polymerization; however, none of the compounds inhibited the ability of the RH mutant to polymerize. When a DNA template was used, the compounds still inhibited polymerization with the same hierarchy as they did in the RH inhibition assays (XZ460 > XZ456 > XZ462), suggesting that the polymerase inhibition is a result of the compounds binding at the RH active site. These data provide a strong support for the idea that the inhibition of the polymerase reaction that was seen with the WT RT was due to the binding of the compounds to the RH active site. We think it is likely that the bound inhibitor interferes with polymerization by inhibiting translocation of RT along the T/P.

To ask whether a bound T/P could prevent the compounds from binding at the RH active site, we used a nucleic acid cold trap. In this type of assay, once RT falls off the labeled T/P, the trap prevents the RT from rebinding to the labeled T/P. In the presence of the cold trap, the compounds had no measurable effect on polymerization; thus, the compounds are unable to inhibit polymerization with a prebound template primer. The simplest explanation is that the presence of the bound template primer prevented the compounds from binding to the RH active site. This explanation fits the observation that the compounds are more effective if they are allowed to bind to RT before the T/P is added to the reaction. Fortunately, both in in vitro assays and in infected cells, RT falls off the template frequently, which gives the compounds a chance to bind to the RH active site.

One last challenge for any inhibitor of the RH of HIV-1 RT is its specificity. Human cells contain two RH enzymes, RH1 and RH2 (16). The RH domain of HIV-1 RT and the human RH1 and RH2 enzymes share structural similarities. Inhibition of either of these human RH enzymes has catastrophic results for the cells. We did not have human RH1 and tested the related RHI from E. coli. None of the compounds were able to inhibit the E. coli RHI nor did the compounds inhibit human RH2. The fact that the compounds did not inhibit these cellular RHs helps to explain the observation that the best compound (XZ460) has a respectable therapeutic index (∼26) in assays done with cultured cells. More importantly, these data show that it is possible to develop compounds that are able to inhibit the RH of HIV-1 without also inhibiting related host enzymes.

The compounds we describe here are not the first that have been developed to bind to the RH active site. The magnesium ions provide a site where inhibitors can bind; the RH active site is relatively flat. Chelation of the crucial magnesium ions would prevent the RH from cleaving the RNA strand of the RNA-DNA heteroduplex (for a review, see reference 3). Given the need for a close association between the magnesium ions and the RNA template for cleavage, it is not surprising that neither of our compounds, nor those described by others, can bind to the RH active site if the nucleic acid substrate is bound first. This conclusion is based on biochemical data and is supported by crystal structures of the compounds bound to the RH active site (Fig. 4 and 5A and B), as well as by other structures of the RH domain bound with RH inhibitors (for examples, see references 2, 12, 24, and 25). However, there are differences in the behavior of our compounds and those that have been described by others. First, some of the compounds that have been reported to inhibit the RH of purified HIV RT do not inhibit viral replication (e.g., 2). There are several possible explanations (low cell permeability, binding to proteins in the medium, etc.); however, in terms of being a useful lead for drug development, a compound should be able to inhibit viral replication with low cytotoxicity. Second, our compounds inhibit both the initial primary and secondary RNase H cleavages. A number of previously described compounds mainly inhibit the secondary cleavages but have little or no effect on the primary cleavages (3, 4). Third, our compounds inhibit the polymerase activity of HIV-1 RT, with either an RNA and/or a DNA template, apparently by binding to the RH active site. The compounds described by others have not been reported to show this effect. We suggest that the ability of the compounds to inhibit the polymerase activity (as well as the RNase H activity) of HIV-1 RT by binding to the RNase H active site is an advantage. By interfering with both activities, the compounds will further decrease the replication efficiency of the virus. Whether this might make it more difficult for RT to develop resistance is unclear. Finally, having a high-resolution crystal structure of XZ462 bound at the HIV-1 RH active site which shows the surrounding ordered water molecules should help us develop derivatives of these compounds with increased binding affinity and greater potency.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of XZ456, XZ460, XZ463, and XZ462. (i) General procedures.

Proton (1H) and carbon (13C) NMR spectra were recorded on a Varian 400 MHz spectrometer or a Varian 500 MHz spectrometer and are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to tetramethylsilane (TMS) and referenced to the solvent in which the spectra were collected. Solvent was removed by rotary evaporation under reduced pressure, and anhydrous solvents were obtained commercially and used without further drying. Purification by silica gel chromatography was performed using Combiflash with an ethyl acetate (EtOAc)-hexane solvent system. Preparative high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) was conducted using a Waters Prep LC4000 system having photodiode array detection and Phenomenex C18 columns (catalog no. 00G-4436-P0-AX; 250 mm by 21.2 mm, 10-μm particle size, 110-Å pore size) at a flow rate of 10 ml/min. Binary solvent systems consisting of 0.1% aqueous trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) (A) and 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile (B) were employed with gradients as indicated. Products were obtained as amorphous solids following lyophilization. Electrospray ionization-mass spectrometric (ESI-MS) data were acquired with an Agilent liquid chromatography-mass selective detector (LC-MSD) system equipped with a multimode ion source. The purities of samples subjected to biological testing were assessed using this system and shown to be ≥95%.

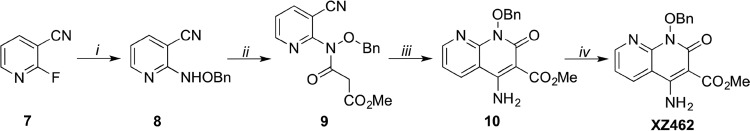

(ii) Scheme 1 (Fig. 14). (a) Methyl 4-((4′-amino-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)amino)-1-(benzyloxy)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate (compound 3).

FIG 14.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of compounds XZ456, XZ460, and XZ463. Reagents and conditions were as follows: (i) trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride, triethylamine (TEA), CH2Cl2, 0°C; (ii) benzidine or 4-aminobiphenyl, N,N-diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF); (iii) H2, Pd/C (10%), H; (iv) sodium methoxide (NaOMe), MeOH; (v) HBr/HOAc (33%), H2O, 80°C.

Methyl 1-(benzyloxy)-2-oxo-4-(((trifluoromethyl)sulfonyl)oxy)-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate (compound 2, 277 mg, 0.61 mmol) was dissolved in dimethylformamide (DMF) (1.0 ml) (21). Benzidine (134 mg, 0.73 mmol) and N-ethyl-N-isopropylpropan-2-amine (0.25 ml, 1.46 mmol) were added to the clear solution. A brown solution was formed. The reaction is exothermic. The reaction mixture was stirred (room temperature, 30 min). The mixture was purified by silica gel column chromatography. Methyl 4-((4′-amino-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)amino)-1-(benzyloxy)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate (compound 3) was provided as a yellow oil in an 81% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.52 (s, 1H), 8.54-8.53 (m, 1H), 7.82 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.33-7.28 (m, 5H), 6.98 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 6.80 (dd, J = 8.2, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 6.68 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 5.25 (s, 2H), 3.89 (s, 3H), 3.73 (bs, 2H).13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.35, 157.22, 153.25, 152.79, 149.59, 146.21, 139.90, 138.37, 137.09, 134.44, 130.07 (2C), 129.96, 128.89, 128.36 (2C), 127.68 (2C), 127.38 (2C), 123.34 (2C), 117.13, 115.42 (2C), 108.92, 102.69, 78.00, 52.61. ESI-MS m/z: 493.1 (MH+).

(b) Methyl 4-((4′-amino-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)amino)-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate (compound XZ456).

Methyl 4-((4′-amino-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)amino)-1-(benzyloxy)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate (compound 3, 800 mg, 0.81 mmol) was suspended in methanol (MeOH) (12 ml). Palladium on carbon (Pd/C) (10%, 80 mg) was added. After degassing, the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature under hydrogen for 1 h. The mixture was filtered and concentrated. The residue was purified by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 0 to 40% B over 30 min; retention time, 24.4 min) and provided methyl 4-((4′-amino-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)amino)-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate (XZ456, 56 mg) as a yellow solid in a 17% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.03 (s, 1H), 8.72 (dd, J = 4.5, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 8.56-8.54 (m, 1H), 7.58 (dd, J = 12.5, 8.5 Hz, 4H), 7.37 (dd, J = 8.1, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 7.09 (dd, J = 8.3, 6.8 Hz, 4H), 3.20 (s, 3H). ESI-MS m/z: 403.1 (MH+).

(c) 1-(Benzyloxy)-4-hydroxy-1,8-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (compound 4).

A suspension of methyl 1-(benzyloxy)-4-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate (compound 1, 1.34 g, 4.13 mmol) in MeOH (30 ml) was mixed with NaOH (1.0 N, 20 ml) (26). The white suspension was heated to boiling. After 1 h, the reaction mixture turned to a clear solution. The solvent was evaporated, and the residue was refluxed (16 h). The reaction mixture was cooled with ice and adjusted to pH 2 with concentrated HCl (aqueous). The formed suspension was filtered, and the white solid was collected and dried. Compound 1-(benzyloxy)-4-hydroxy-1,8-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (compound 4, 1.11 g) was provided as a white solid in a 98% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 12.08 (brs, 1H), 8.72 (dd, J = 4.7, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.27 (dd, J = 7.9, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.66-7.63 (m, 2H), 7.45-7.39 (m, 3H), 7.35 (dd, J = 7.8, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 6.05 (s, 1H), 5.14 (s, 2H), 4.05 (s, 4H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 160.40, 159.81, 151.79, 148.67, 135.27, 133.14, 129.83 (2C), 129.16, 128.73 (2C), 118.92, 111.71, 99.36, 77.58. ESI-MS m/z: 269.1 (MH+) (26, 27).

(d) 1-(Benzyloxy)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl trifluoromethanesulfonate (compound 5).

1-(Benzyloxy)-4-hydroxy-1,8-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (compound 4, 0.88 mg, 3.30 mmol) was dissolved in CH2Cl2 (15 ml). Triethylamine (1.1 ml, 7.91 mmol) and trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride (3.95 ml, 3.95 mmol, 1.0 M in CH2Cl2) were added dropwise at 0°C. The solution was stirred at 0°C for 30 min. The resultant reaction mixture was concentrated and purified by silica gel column chromatography. The title compound (compound 5, 0.99 g) was provided as a white solid in a 75% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.80 (dd, J = 4.8, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 8.09 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.67-7.65 (m, 2H), 7.40-7.34 (m, 4H), 6.86 (s, 1H), 5.32 (s, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 400.9 (MH+).

(e) 4-((4′-Amino-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)amino)-1-(benzyloxy)-1,8-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (compound 6a).

1-(Benzyloxy)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl trifluoromethanesulfonate (compound 5, 167 mg, 0.41 mmol) and benzidine (92 mg, 0.50 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (1.0 ml) in a sealed vial. The solution was microwave heated (140°C, 1 h). The resultant mixture was purified by silica gel column and provided 4-((4′-amino-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)amino)-1-(benzyloxy)-1,8-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (compound 6a, 73 mg) as a yellow solid in a 40% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.94 (s, 1H), 8.75 (dd, J = 4.6, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.69 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.67-7.63 (m, 4H), 7.44-7.41 (m, 6H), 7.35 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 6.70 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 5.85 (s, 1H), 5.15 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 159.49, 151.55, 148.72, 148.15, 148.05, 137.71, 137.62, 135.40, 132.80, 129.82 (2C), 129.13, 128.74 (2C), 127.74, 127.48 (2C), 126.70 (2C), 124.70 (2C), 118.47, 115.11 (2C), 110.74, 94.52, 77.52. ESI-MS m/z: 435.1 (MH+).

(f) 4-((4′-Amino-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)amino)-1-hydroxy-1,8-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (XZ460).

The mixture of 4-((4′-amino-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)amino)-1-(benzyloxy)-1,8-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (compound 6a, 73 mg, 0.17 mmol) in HBr in acetic acid (33%, 2.0 ml) and H2O (1.0 ml) was heated and stirred (80°C, 1 h). The solvent was removed by vacuum, and the residue was triturated with acetonitrile and filtered. The solid was purified by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 0 to 40% B over 30 min; retention time, 24.5 min) and provided 4-((4′-amino-[1,1′-biphenyl]-4-yl)amino)-1-hydroxy-1,8-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (compound XZ460, 24 mg) as yellow flurry solid in 80% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 9.05 (s, 1H), 8.77 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.70 (dd, J = 4.9, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.85-7.81 (m, 2H), 7.79-7.75 (m, 2H), 7.49-7.42 (m, 5H), 6.03 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 159.67, 149.82, 148.07, 146.82, 140.12, 139.84, 135.00, 133.99, 131.21, 128.18 (2C), 128.12 (2C), 124.18 (2C), 123.81 (2C), 117.86, 110.95, 95.66. ESI-MS m/z: 345.1 (MH+).

(g) 4-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-ylamino)-1-(benzyloxy)-1,8-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (compound 6b).

Compounds 1-(benzyloxy)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridin-4-yl trifluoromethanesulfonate (compound 5, 143 mg, 0.36 mmol) and [1,1′-biphenyl]-4-amine (121 mg, 0.72 mmol) were dissolved in DMF (1 ml). The solution was microwave heated (140°C, 2 h). The resultant brown mixture was purified by silica gel column chromatography. 4-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-ylamino)-1-(benzyloxy)-1,8-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (compound 6b, 106 mg) was produced as a yellow solid in a 70% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.70 (dd, J = 4.6, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.18 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.69-7.67 (m, 2H), 7.60-7.55 (m, 4H), 7.46-7.42 (m, 2H), 7.38-7.31 (m, 7H), 6.76 (bs, 1H), 6.27 (s, 1H), 5.29 (s, 2H). ESI-MS m/z: 420.1 (MH+), 442.0 (MNa+), 861.0 (M2Na+).

(h) 4-([1,1′-Biphenyl]-4-ylamino)-1-hydroxy-1,8-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (compound XZ463).

The mixture of 4-([1,1′-biphenyl]-4-ylamino)-1-(benzyloxy)-1,8-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (compound 6b, 62 mg, 0.15 mmol) in HBr-HOAc (33%, 2.0 ml) and H2O (1.0 ml) was heated and stirred (80°C, 1 h). The solvent was removed by vacuum, and the residue was mixed with acetonitrile and filtered. The yellow residue was purified by preparative HPLC (with a linear gradient of 20% B to 80% B over 30 min; retention time, 21.9 min) and provided 4-([1,1′-biphenyl]-4-ylamino)-1-hydroxy-1,8-naphthyridin-2(1H)-one (compound XZ463, 37 mg) as a yellow fluffy solid in a 75% yield. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.91 (s, 1H), 8.70 (dd, J = 4.6, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.65 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.70 (s, 2H), 7.49 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.43 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.40-7.36 (m, 2H), 6.01 (s, 1H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 159.89, 151.18, 148.86, 146.88, 140.02, 139.77, 136.36, 132.65, 129.43 (2C), 128.07 (2C), 127.70, 126.86 (2C), 123.84 (2C), 117.81, 110.39, 95.53. ESI-MS m/z: 330.1 (MH+), 681.0 (M2Na+) (27, 28).

(iii) Scheme 2 (Fig. 15). (a) 2-((Benzyloxy)amino)nicotinonitrile (compound 8).

FIG 15.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of compound XZ462. Reagents and conditions were as follows: (i) BnONH2, DMSO, 120°C; (ii) methyl 3-chloro-3-oxopropanoate, TEA, CH2Cl2; (iii) NaOMe, MeOH; (iv) H2, Pd/C (10%), MeOH.

2-Fluoronicotinonitrile (compound 7, 1.59 g, 13.0 mmol) and O-benzylhydroxylamine (4.55 ml, 39.0 mmol) were dissolved in DMSO (2.0 ml). The reaction mixture was microwave heated and stirred (120°C, 10 h). The reaction mixture was extracted with EtOAc. The organic phase was washed by brine and dried by sodium sulfate. After filtration and concentration, the residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography. Compound 2-((benzyloxy)amino)nicotinonitrile (compound 8, 2.78 g) was provided as a yellow oil in a 95% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.22 (dd, J = 1.8, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (brs, 1H), 7.84 (dd, J = 1.6, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.46-7.44 (m, 2H), 7.39-7.33 (m, 3H), 6.87 (dd, J = 5.2, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.04 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.90, 151.83, 143.21, 135.71, 129.24 (2C), 128.61 (3C), 116.80, 116.17, 94.32, 78.73. ESI-MS m/z: 226.1 (MH+) (21, 22).

(b) Methyl 3-((benzyloxy)(3-cyanopyridin-2-yl)amino)-3-oxopropanoate (compound 9).

To a solution of 2-((benzyloxy)amino)nicotinonitrile (compound 8, 3.03 g, 13.4 mmol) and triethylamine (5.64 ml, 40.3 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (50 ml), methyl 3-chloro-3-oxopropanoate (4.45 ml, 40.3 mmol) was added dropwise. The mixture was stirred (room temperature, 2 h) and then filtered and concentrated. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography. Compound methyl 3-((benzyloxy)(3-cyanopyridin-2-yl)amino)-3-oxopropanoate (compound 9, 3.85 g) was provided as a brown oil in an 88% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.62 (dd, J = 2.0, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (dd, J = 2.0, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.33-7.31 (m, 2H), 7.28-7.23 (m, 4H), 4.96 (s, 2H), 3.70 (s, 3H), 3.59 (s, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.83, 166.67 (2C), 152.90, 152.16, 141.96, 133.30, 129.97 (2C), 129.26, 128.57 (2C), 122.48, 114.52, 78.85, 52.54, 41.39. ESI-MS m/z: 326.1 (MH+).

(c) Methyl 4-amino-1-(benzyloxy)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate (compound 10).

To a solution of methyl 3-((benzyloxy)(3-cyanopyridin-2-yl)amino)-3-oxopropanoate (compound 9, 3.85 g, 11.8 mmol) in MeOH (50 ml) was added sodium methanolate (6.77 ml, 25% in MeOH). The formed yellow suspension was stirred (room temperature, 15 h). The reaction mixture was brought to pH 3 by the addition of HCl (aqueous, 1.0 N). The mixture was extracted by EtOAc and dried by sodium sulfate. The solution was filtered and concentrated. The residue was purified by silica gel column chromatography. Compound methyl 4-amino-1-(benzyloxy)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate (compound 10, 926 mg) was provided as a brown oil in a 24% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.65 (dd, J = 1.6, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 8.17 (dd, J = 1.6, 8.4 Hz, 1H), 7.65-7.63 (m, 2H), 7.31-7.29 (m, 3H), 7.08 (dd, J = 4.8, 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.21 (s, 2H), 3.91 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.48, 157.92, 155.38, 153.33, 148.88, 134.31, 132.28, 129.96 (2C), 128.84, 128.30 (2C), 118.15, 108.25, 94.27, 77.94, 52.08. ESI-MS m/z: 326.1 (MH+), 348.1 (MNa+).

(d) Methyl 4-amino-1-hydroxy-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate (compound XZ462).

Methyl 4-amino-1-(benzyloxy)-2-oxo-1,2-dihydro-1,8-naphthyridine-3-carboxylate (compound 10, 158 mg, 0.48 mmol) was suspended in MeOH (12.0 ml) and EtOAc (3.0 ml). Pd/C (100 mg, 10%) was added. The mixture was stirred under hydrogen (1 h) and filtered, and the solution was concentrated. The residue was purified by preparative reverse-phase HPLC (linear gradient of 0 to 40% B over 30 min; retention time, 20.8 min) and provided the title compound (compound XZ462, 86 mg) as a pale yellow solid in a 76% yield. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.60 (dd, J = 4.6, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 8.57 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 8.25 (bs, 1H), 7.23 (dd, J = 8.0, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 3.70 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 168.88, 157.45, 153.99, 153.04, 148.90, 134.15, 117.91, 108.34, 94.09, 51.87. ESI-MS m/z: 236.0 (MH+), 258.0 (MNa+), 493.0 (M2Na+) (29).

Polymerase-independent RH assays.

The general protocol for the RNase H (RH) assays has been previously described (17). The RNA-DNA heteroduplexes that were used in the assays are shown in the figures. The RNA oligonucleotides were obtained from Dharmacon Research, Inc. The DNA oligonucleotides were from IDT. For all of the polymerase-independent RH assays, the RNA in 2.0 μl of a 10.0 μM stock was 5′ end labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase (NEB) and [γ-32P]ATP. After purification, the RNA oligonucleotides were annealed to synthetic DNA oligonucleotides by heating and slow cooling. Therefore, all of the assays had identical amounts of template/primer (T/P) and of RT, making comparisons accurate. The compounds were dissolved in DMSO. For reactions in which RT and the inhibitors were allowed to bind first, 10.0 μM compound (or an equal volume of DMSO for the control) was added to a reaction mixture to give a final concentration of 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM MgCl2, 100 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml, 10 mM CHAPS (3-[(3-cholamidopropyl)-dimethylammonio]-1-propanesulfonate), 50.0 ng RT, and 1 U of Superasin (Ambion)/μl. After the samples were allowed to equilibrate, the reactions were initiated by the addition of the labeled T/P. The final reaction volume was 12 μl (T/P at 0.2 μM), and the reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C. Aliquots were removed at the indicated time points (as shown on the figures), and the reactions were halted by the addition of 2× gel loading buffer. The reaction products were heated to 100°C and fractionated on a 15% polyacrylamide sequencing gel. Products were visualized by exposure to X-ray film and also analyzed using a Phosphoimager screen. Reactions in which RT interacted with the T/P and compounds at the same time are similar. The compounds (10.0 μM) and the T/P were added to a reaction mixture to give a final concentration of 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM MgCl2, 100 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml, 10 mM CHAPS, and 1 U of Superasin (Ambion)/μl. After equilibration, the reactions were initiated by the addition of 50 ng RT and treated as described above.

For the E. coli RNase HI assay, 0.1 U was used (NEB). For the human RNase H2 assay, 10.0 nM protein was used (generous gift of Robert Crouch, Section on Formation of RNA, Division of Developmental Biology, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

For the DNA 3′-end-directed cleavages, the RNA to be labeled was 5′-GGGCCACUUUUUAAAAGAAAAGGGGGGACUGGAAGGGCUAAUUCACUCACAACGAAGAAA-3′. The sequence comes from the boundary between the PPT and U3. The PPT sequence is underlined. The DNA oligonucleotide was 5′-GAGTGAATTAGCCCTTCCAGTCCC-3′. For the RNA 5′-end-directed cleavages, the RNA to be labeled was 5′-ACCAGAUCUGAGCCUGGGAGCU-3′ and the DNA oligonucleotide was 5′-AGCTCCCAGGCTCAGATCTGGTCTAACCAG-3′. The internal cleavage assay used an RNA with the sequence 5′-ACCAGAUCUGAGCCUGGGAGCU-3′; the DNA sequence was 5′-AGCTCCCAGGCTCAGATCTGGT-3′. For the PPT cleavage assay, the RNA sequence was 5′-AAAAGAAAAGGGGGGACTGGAAGGGCTAATTCACTC-3′ (the PPT sequence is underlined; the remainder of the sequence is the adjoining U3). The DNA sequence was 5′-GAGTGAATTAGCCCTTCCAGTCCCCCCTTTTGTTTTAAAAAGTGG-3′ (the PPT complement is underlined).

Polymerase-dependent RH and polymerase assays.

The polymerase-dependent RH and polymerase assays were similar to those described above. For the polymerase-dependent RH assay, the RNA was 101 nt long and the sequence was derived from the sequence from the U5-PBS boundary region (5′-GUGUGCCCGUCUGUUGUGUGACUCUGGUAACUAGAGAUCCCUCAGACCCUUUUAGUCAGUGUGGAAAAUCUCUAGCAGUGGCGCCCGAACAGGGACCUGA-3′) (the PBS complement sequence is underlined). The RNA oligonucleotide was 5′ end labeled and then annealed to a DNA oligonucleotide (5′-TCAGGTCCCTGTTCGGGCGCCA-3′) (the PBS complement sequence is underlined). After annealing, the T/P was added to start the reaction in mixtures that contained (final concentration) 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM MgCl2, 100 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml, 10 mM CHAPS, 10.0 μl each dNTP, 10.0 μM compound, 0.5 μg of RT (because the template was long, the amount of RT was increased), and 1 U of Superasin (Ambion)/μl. The final reaction volume was 12 μl. Compounds and RT were allowed to interact first, before the T/P was added. The samples were incubated at 37°C. Aliquots were removed at the indicated time points (as shown on the figures), and the reaction was halted by the addition of 2× gel loading buffer. The reaction products were heated to 100°C and then fractionated on a 15% polyacrylamide sequencing gel. Products were visualized by exposure to X-ray film and also analyzed using a Phosphoimager screen.

For the RNA-dependent DNA polymerase (RDDP) and DNA-dependent DNA polymerase (DDDP) assays, the DNA oligonucleotide was 5′ end labeled and annealed to either a long RNA template (described above) or a long DNA template (containing the same sequence as the RNA). As described above, the T/P was added to start the reaction in mixtures containing 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM MgCl2, 100 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml, 10 mM CHAPS, 10.0 μl each dNTP, 10.0 μM compound, 0.5 μg (∼85 nM) of RT, and 1 U of Superasin (Ambion)/μl (if an RNA template). The final reaction volume was 12 μl. Incubation was at 37°C. Aliquots were removed at the indicated time points (as shown on the figures), and the reaction was halted by the addition of 2× gel loading buffer. The reaction products were treated as described above.

Processivity assay with the RH compounds.

The processivity assay with the RH compounds is similar to the DDDP assay described above. Two microliters of −47 primer (5′-CGCCAGGGTTTTCCCAGTCACGAC-3′) was 5′ end labeled and then purified. The purified, labeled oligonucleotide was annealed to single-stranded M13mp18 DNA (NEB) by heating and slow cooling. For each reaction, 0.25 μg of RT (∼40 nM in the final reaction) was allowed to bind to the T/P for 5 min in a reaction mixture containing 25 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 5.0 mM MgCl2, 100 μg of bovine serum albumin/ml, and 10 mM CHAPS. The reaction was initiated by the addition of a mixture containing dNTPs (10.0 μM in final reaction buffer), compounds to be tested (10.0 μM in the final reaction buffer or an equal volume of DMSO for the control lane), and either poly(rC)-oligo(dG) (25 U/ml stock; 3.25 U/ml in the final reaction) for the “+ trap” reactions or an equal volume of water for the “− trap” reactions. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 5 min. The reactions were halted by the addition of 1 volume of a 1:1 mixture of phenol-chloroform. After thorough mixing, the phases were separated using a microcentrifuge. The nucleic acids in the aqueous portion of the mixture were precipitated with ethanol, collected by sedimentation in a microcentrifuge, resuspended in 2× gel loading buffer, heated to 100°C, and fractionated on a 6.0% polyacrylamide sequencing gel. The gel was transferred to 3-mm paper (grade 3MM Chr cellulose chromatography papers; Whatman) and dried, and then the products were visualized by exposure to X-ray film, as well as by use of a Phosphoimager.

For the trap test, the RT was treated as described above but in the presence (+) or absence (−) of the cold trap. The reaction was initiated by the addition of dNTPs and the labeled T/P. The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 5 min. The reactions were halted by the addition of 1 volume of phenol-chloroform. The nucleic acids in the aqueous phase were precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in 2× gel loading buffer. The samples were then treated as described above.

Viral replication and cytotoxicity assays.

Human embryonic kidney cell culture cell line 293 was acquired from the American type Culture Collection (ATCC). The human osteosarcoma cell line HOS was obtained from Richard Schwartz (Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI) and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 5% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum, 5% newborn calf serum, and penicillin (50 U/ml) plus streptomycin (50 μg/ml; Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD). The transfection vector pNLNgoMIVR−ΔLUC was made from pNLNgoMIVR−ΔEnv.HSA by removing the HSA reporter gene and replacing it with a luciferase reporter gene using the NotI and XhoI restriction sites (30, 31).

Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G)-pseudotyped HIV vectors were produced by transfections of 293 cells as described previously (30). Briefly, 293 cells were plated on 100-mm-diameter dishes at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells per plate and transfected the next day with 10 μg of pNLNgoMIVR−ΔLUC and 1.5 μg of pHCMV-g (obtained from Jane Burns, University of California, San Diego, CA) by using the calcium phosphate delivery method. Approximately 6 h after the calcium phosphate precipitate was added, the 293 cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with fresh medium for 48 h. The virus-containing supernatants were then harvested, clarified by low-speed centrifugation, filtered, and diluted for use in antiviral infection assays. Antiviral compounds were screened for cellular cytotoxicity by treating cells with compounds using a concentration range of 250 μM to 0.05 μM and then incubating them at 37°C for 48 h. Toxicity was measured using the ATPlite luminescence detection system as described previously (31). The EC50s of the antiviral compounds in single-round infectivity assays were determined using standard methods (31).

Vector constructs.

The G140S Q148H HIV-1 integrase drug-resistant mutant was prepared previously (32–34). The preparation of the NNRTI-resistant mutants has been described previously (35). The NRTI-resistant mutants were prepared as follows: the RT codon reading frame was removed from pNLNgoMIVR−ΔEnv.LUC (between the SpeI and SalI sites) and placed between the SpeI and SalI sites of pBluescript II KS+. Using that construct as the wild-type template, we prepared the K70R and M184V HIV-1 RT drug-resistant mutants using the QuikChange II XL (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) site-directed mutagenesis protocol. The following sense with cognate antisense (not shown) oligonucleotides (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA) were used in the mutagenesis: K70R, 5′-AAGAAAAAAGACAGTACTAGATGGAGAAAATTAGTAGAT-3′; M184V, 5′-GTTATCTATCAATACGTTGATGATTTGTATGTA-3′. The DNA sequence of each construct was verified independently by DNA sequence determination. The mutant RT coding sequences from pBluescript II KS+ were then subcloned into pNLNgoMIVR−ΔEnv.LUC (between the SpeI and SalI sites) to produce the full-length mutant HIV-1 RT constructs. The DNA sequences of the final plasmids were also checked independently by DNA sequence determination.

Computer modeling.

All computer modeling was performed using MOE2016.1001 software (Chemical Computing Group, Montreal, Quebec, Canada). The coordinates of the following retroviral RT-RT inhibitor structures were used: HIV RT-MK1 (PDB ID 3LP0) and HIV RT-MK2 (PDB ID 3LP1) (12).

X-ray crystallography.