ABSTRACT

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is closely associated with type 2 diabetes. We reported that HCV infection induces the lysosomal degradation of hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha (HNF-1α) via interaction with HCV nonstructural protein 5A (NS5A) protein, thereby suppressing GLUT2 gene expression. The molecular mechanisms of selective degradation of HNF-1α caused by NS5A are largely unknown. Chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) is a selective lysosomal degradation pathway. Here, we investigated whether CMA is involved in the selective degradation of HNF-1α in HCV-infected cells and observed that the pentapeptide spanning from amino acid (aa) 130 to aa 134 of HNF-1α matches the rule for the CMA-targeting motif, also known as KFERQ motif. A cytosolic chaperone protein, heat shock cognate protein of 70 kDa (HSC70), and a lysosomal membrane protein, lysosome-associated membrane protein type 2A (LAMP-2A), are key components of CMA. Immunoprecipitation analysis revealed that HNF-1α was coimmunoprecipitated with HSC70, whereas the Q130A mutation (mutation of Q to A at position 130) of HNF-1α disrupted the interaction with HSC70, indicating that the CMA-targeting motif of HNF-1α is important for the association with HSC70. Immunoprecipitation analysis revealed that increasing amounts of NS5A enhanced the association of HNF-1α with HSC70. To determine whether LAMP-2A plays a role in the degradation of HNF-1α protein, we knocked down LAMP-2A mRNA by RNA interference; this knockdown by small interfering RNA (siRNA) recovered the level of HNF-1α protein in HCV J6/JFH1-infected cells. This result suggests that LAMP-2A is required for the degradation of HNF-1α. Immunofluorescence study revealed colocalization of NS5A and HNF-1α in the lysosome. Based on our findings, we propose that HCV NS5A interacts with HSC70 and recruits HSC70 to HNF-1α, thereby promoting the lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α via CMA.

IMPORTANCE Many viruses use a protein degradation system, such as the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway or the autophagy pathway, for facilitating viral propagation and viral pathogenesis. We investigated the mechanistic details of the selective lysosomal degradation of hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha (HNF-1α) induced by hepatitis C virus (HCV) NS5A protein. Using site-directed mutagenesis, we demonstrated that HNF-1α contains a pentapeptide chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA)-targeting motif within the POU-specific domain of HNF-1α. The CMA-targeting motif is important for the association with HSC70. LAMP-2A is required for degradation of HNF-1α caused by NS5A. We propose that HCV NS5A interacts with HSC70, a key component of the CMA machinery, and recruits HSC70 to HNF-1α to target HNF-1α for CMA-mediated lysosomal degradation, thereby facilitating HCV pathogenesis. We discovered a role of HCV NS5A in CMA-dependent degradation of HNF-1α. Our results may lead to a better understanding of the role of CMA in the pathogenesis of HCV.

KEYWORDS: chaperone-mediated autophagy, hepatitis C virus, HNF-1α, HSC70, NS5A

INTRODUCTION

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection often causes chronic hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. HCV is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Flaviviridae family, Hepacivirus genus. The HCV genome consists of a 9.6-kb RNA encoding a polyprotein of 3,010 amino acids (aa). The polyprotein is cleaved co- and posttranslationally into at least 10 proteins by viral proteases and cellular signalases. The viral proteins required for RNA replication include nonstructural protein NS3 (NS3), NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B (1). The development of HCV RNA replicon systems and HCV cell culture systems has enabled the investigation of HCV replication and the HCV life cycle (2–5). The discovery of direct-acting antiviral drugs for HCV has greatly improved the treatment of chronic hepatitis C, but the emergence of drug resistance raises new concerns (6).

HCV infection often causes not only intrahepatic diseases but also extrahepatic manifestations, such as type 2 diabetes. Clinical and experimental studies suggested that HCV infection is an additional risk factor for the development of diabetes (7–9). We reported that in a human hepatoma cell line, HCV suppressed hepatocytic glucose uptake through downregulation of the cell surface expression of glucose transporter 2 (GLUT2) (10). We further reported that HCV infection induces the lysosomal degradation of hepatocyte nuclear factor 1alpha (HNF-1α) protein via interaction with domain I of NS5A protein, thereby downregulating the GLUT2 promoter (11). The POU-specific (POUs) domain of HNF-1α is responsible for the interaction with NS5A protein (12). The molecular mechanisms underlying the selective lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α caused by HCV NS5A are largely unknown.

Autophagy regulates the recycling process that involves the degradation of cellular constituents in the lysosome. There are at least three types of autophagy: macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) (13). Macroautophagy, the best-characterized autophagy pathway, starts with the formation of the limiting membrane of the autophagosome, a double-membrane vesicle, through the assembly of proteins and lipids from different cellular organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, and plasma membrane. Macroautophagy is a nonselective bulk degradation process. In contrast, CMA is a selective degradation pathway that targets only proteins containing a pentapeptide CMA-targeting motif (also known as a KFERQ motif) for lysosomal degradation (14, 15). CMA promotes the degradation of a specific substrate protein that enters into the lysosome through lysosome-associated membrane protein type 2A (LAMP-2A). LAMP-2A functions as a receptor for the selective uptake and degradation of proteins by lysosomes via the CMA-dependent pathway (16).

Substrate proteins of CMA contain the CMA-targeting motif, which is selectively recognized by the cytosolic heat shock cognate protein of 70 kDa (HSC70). The CMA-targeting motif consists of an invariant amino acid, one or two of the positively charged residues lysine (K) or arginine (R), one or two of the hydrophobic residues isoleucine (I), leucine (L), valine (V), or phenylalanine (F), one of the negatively charged residues aspartic acid (D) or glutamic acid (E), and one glutamine (Q) residue on either side of the pentapeptide (17). Although microautophagy involves the selection of a protein cargo by HSC70 using the same pentapeptide motif, microautophagy is independent of LAMP-2A, but it is dependent on endosomal sorting complex required for transport I (ESCRT-I) and ESCRT-III (13, 18).

In this study, we sought to clarify the molecular mechanisms underlying the selective lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α protein induced by HCV NS5A. We investigated the role of CMA in the selective degradation of HNF-1α. A mutational analysis revealed that HNF-1α contains the CMA-targeting motif that is required for recognition by HSC70. Our findings also demonstrate that HCV NS5A protein promotes the association of HNF-1α with HSC70. Knockdown of LAMP-2A by small interfering RNA (siRNA) restored the levels of HNF-1α protein. We propose that HCV NS5A protein promotes the lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α via CMA.

RESULTS

The CMA-targeting motif of HNF-1α is required for the interaction with HSC70.

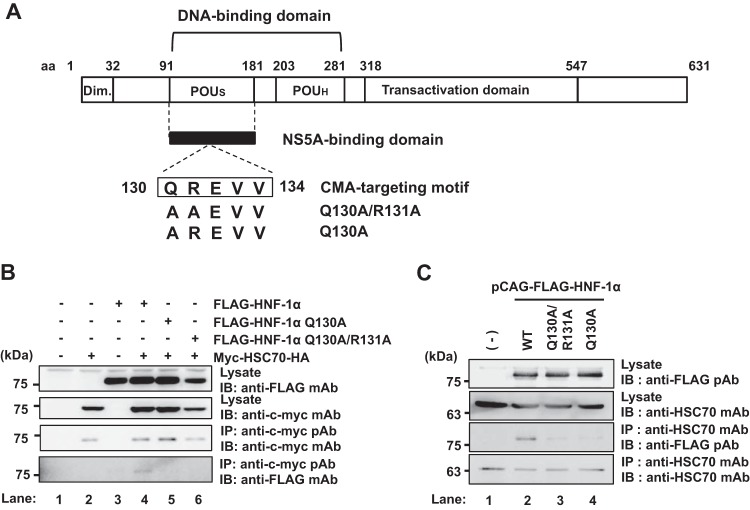

To determine whether HNF-1α contains a CMA-targeting motif, we analyzed the amino acid sequence of HNF-1α based on the rules for the consensus CMA-targeting motif (17). The consensus CMA-targeting motif is based on the physical properties of the amino acid residues as described above. Following this rule, a putative CMA-targeting motif was identified in the region spanning from aa 130 to aa 134 within the POUs domain of HNF-1α (Fig. 1A). The pentapeptide 130QREVV134 completely matches the rules for the CMA-targeting motif.

FIG 1.

HNF-1α contains the CMA-targeting motif that is required for interaction with HSC70 in the POUs domain. (A) Schematic representation of HNF-1α. The CMA-targeting motif resides in the region ranging from aa 130 to aa 134 of the POUs domain of HNF-1α. Expression plasmids for FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A/R131A and FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A were constructed. Dim., dimerization domain; POUh, POU homeodomain. (B) Huh-7.5 cells were transfected with pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α, pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A/R131A, or pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A. At 48 h after transfection, cells were harvested. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated (IP) with rabbit anti-c-myc PAb, followed by immunoblotting (IB) with mouse anti-c-myc MAb (3rd panel) or mouse anti-FLAG MAb (4th panel). Input samples were immunoblotted with either anti-FLAG MAb (1st panel) or anti-c-myc MAb (2nd panel). (C) Huh-7.5 cells were plated at 1.5 × 106 cells/10-cm dish and cultured for 12 h. Cells were transfected with pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α, pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A/R131A, or pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A. At 48 h after transfection, cells were harvested. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with mouse anti-HSC70 MAb, followed by immunoblotting with rabbit anti-FLAG PAb (3rd panel) or mouse anti-HSC70 MAb (4th panel). The expression of FLAG-HNF-1α proteins or endogenous HSC70 was examined using the same cell lysates by immunoblotting with either anti-FLAG PAb (1st panel) or anti-HSC70 MAb (2nd panel).

To determine whether the putative CMA-targeting motif of HNF-1α is required for the HCV-induced lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α, we constructed plasmids expressing FLAG-tagged mutants with mutations of the CMA-targeting motif, pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A (encoding a change of Q to A at position 130) and pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A/R131A. To determine whether the CMA-targeting motif of HNF-1α is required for its interaction with HSC70, we performed a coimmunoprecipitation analysis. Overexpressed myc- and HA (hemagglutinin)-tagged HSC70 (myc-HSC70-HA) interacted with FLAG-HNF-1α (Fig. 1B, 4th panel, lane 4) but not with either FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A or FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A/R131A (Fig. 1B, 4th panel, lanes 5 and 6). Moreover, the coimmunoprecipitation analysis revealed that endogenous HSC70 was coimmunoprecipitated with FLAG-HNF-1α (Fig. 1C, 3rd panel, lane 2). On the other hand, neither FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A nor FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A/R131A was coimmunoprecipitated with endogenous HSC70 (Fig. 1C, 3rd panel, lanes 3 and 4). These results suggest that HSC70 interacts with HNF-1α via the CMA-targeting motif.

HCV NS5A enhances the interaction between HSC70 and HNF-1α.

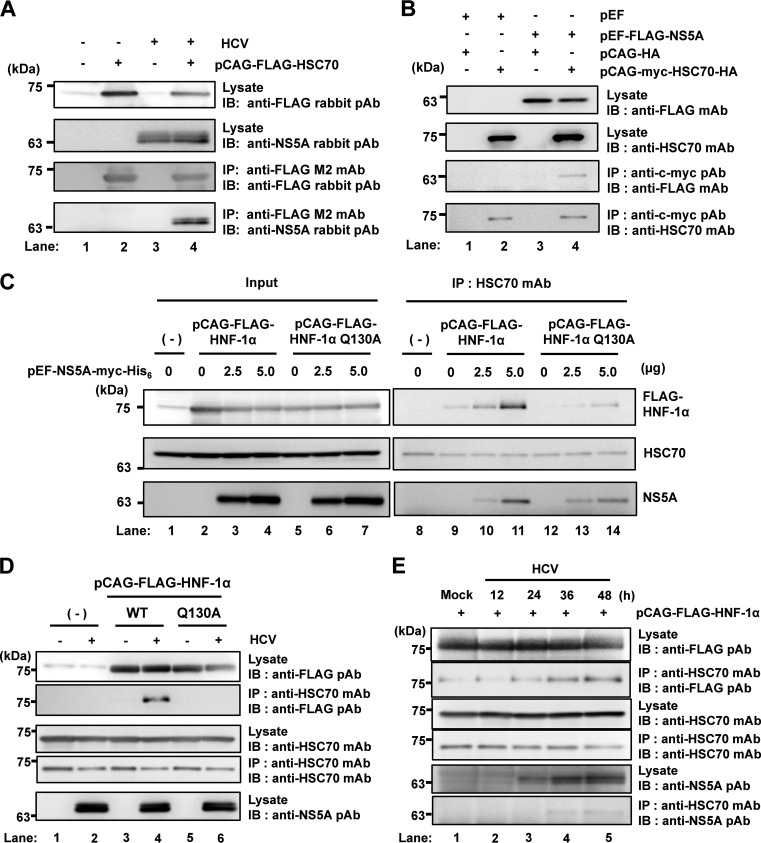

It was reported that HCV NS5A protein interacts with HSC70 in HCV reporter virus FNX-Rluc-infected Huh-7.5 cells (19). To determine whether HCV NS5A can interact with HSC70 in HCV J6/JFH1-infected cells, we infected Huh-7.5 cells with HCV J6/JFH1 and then transfected them with pCAG-FLAG-HSC70. An immunoprecipitation analysis revealed that NS5A protein was coimmunoprecipitated with FLAG-HSC70 (Fig. 2A, 4th panel, lane 4), suggesting that HCV NS5A interacts with HSC70 in HCV J6/JFH1-infected cells.

FIG 2.

HCV NS5A protein enhances the interaction between HSC70 and HNF-1α. (A) Huh-7.5 cells (1.5 × 106 cells/10-cm dish) were infected with HCV J6/JFH1 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1. At 4 h postinfection, cells were transfected with pCAG-FLAG-HSC70 and cultured for 48 h. Cells were harvested and assayed for immunoprecipitation with mouse anti-FLAG M2 MAb, followed by immunoblotting with rabbit anti-FLAG PAb (3rd panel) or rabbit anti-NS5A PAb (4th panel). Input samples were immunoblotted with either rabbit anti-FLAG PAb (1st panel) or rabbit anti-NS5A PAb (2nd panel). (B) Huh-7.5 cells (1.5 × 106 cells/10-cm dish) were transfected with either FLAG-HNF-1α or empty plasmid together with pCAG-myc-HSC70-HA as indicated, and cultured. At 48 h after transfection, cells were harvested. Cell lysates were assayed for immunoprecipitation with rabbit anti-c-myc PAb, followed by immunoblotting with mouse anti-FLAG MAb (3rd panel) or mouse anti-HSC70 MAb (4th panel). Input samples were immunoblotted with either anti-FLAG MAb (1st panel) or anti-HSC70 MAb (2nd panel). (C) Huh-7.5 cells were plated at 1.5 × 106 cells/10-cm dish and cultured for 12 h. Cells were transfected with increasing amounts of pEF1A-NS5A-myc-His6 together with either pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α or pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A. At 48 h after transfection, the cells were harvested. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with mouse anti-HSC70 MAb, followed by immunoblotting with rabbit anti-FLAG PAb (1st panel, right), mouse anti-HSC70 MAb (2nd panel, right), or mouse anti-c-myc MAb (3rd panel, right). Input samples were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG PAb (1st panel, left), anti-HSC70 MAb (2nd panel, left), or anti-c-myc MAb (3rd panel, left). (D) Huh-7.5 cells (1.5 × 106 cells/10-cm dish) were infected with HCV J6/JFH1 at an MOI of 1. At 4 h postinfection, cells were transfected with either pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α or pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A and cultured for 48 h. Cells were harvested and assayed for immunoprecipitation with mouse anti-HSC70 MAb. Bound proteins were immunoblotted with rabbit anti-FLAG PAb (2nd panel) or mouse anti-HSC70 MAb (4th panel). Input samples were immunoblotted with anti-FLAG PAb (1st panel), anti-HSC70 MAb (3rd panel), or anti-NS5A rabbit PAb (5th panel). (E) Huh-7.5 cells (1.5 × 106 cells/10-cm dish) were transfected with pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α. At 24 h posttransfection, cells were infected with HCV J6/JFH1 at an MOI of 0.5 for 12 h, 24 h, 36 h, or 48 h. Cells were harvested and assayed for immunoprecipitation with mouse anti-HSC70 MAb. Bound proteins were immunoblotted with rabbit anti-FLAG PAb (2nd panel) or mouse anti-HSC70 MAb (4th panel). Input samples were immunoblotted with anti-FLAG PAb (1st panel), anti-HSC70 MAb (3rd panel), or rabbit anti-NS5A PAb (5th panel).

To determine whether HCV NS5A interacts with HSC70 in a transient expression system, Huh-7.5 cells were transfected with pEF-FLAG-NS5A together with pCAG-myc-HSC70-HA as indicated in Fig. 2B. The immunoprecipitation analysis revealed that FLAG-NS5A was coimmunoprecipitated with myc-HSC70-HA (Fig. 2B, 3rd panel, lane 4).

To determine whether HCV NS5A affects the interaction between HNF-1α and HSC70, we transfected Huh-7.5 cells with increasing amounts of pEF-NS5A-myc-His6 together with either pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α or pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A. An immunoprecipitation analysis using anti-HSC70 monoclonal antibody (MAb) revealed that increasing the amount of NS5A increased the precipitation of FLAG-HNF-1α (Fig. 2C, 1st panel, lanes 9 to 11) but not of FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A (Fig. 2C, 1st panel, lanes 12 to 14). These results suggest that HCV NS5A enhances the interaction between HNF-1α and HSC70.

To determine whether HCV NS5A affects the interaction between HNF-1α and HSC70 in HCV-infected cells, we infected Huh-7.5 cells with HCV J6/JFH1 and transfected cells with either pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α or pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A. The immunoprecipitation analysis using anti-HSC70 MAb revealed that FLAG-HNF-1α but not FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A was coprecipitated with HSC70 in HCV-infected cells (Fig. 2D, 2nd panel, lanes 4 and 6), whereas FLAG-HNF-1α was not coprecipitated with HSC70 in mock-infected cells (Fig. 2D, 2nd panel, lane 3). These results suggest that HCV NS5A enhances the interaction between HNF-1α and HSC70 via the CMA-targeting motif in HCV-infected cells.

To determine whether HCV infection over time also increases the interaction of HSC70 with HNF-1α, we collected the cells at 12, 24, 36, and 48 h postinfection. The immunoprecipitation analysis using anti-HSC70 MAb revealed that HCV infection over time increased the interaction between HNF-1α and HSC70 (Fig. 2E, 2nd panel, lanes 1 to 5). This result indicates that increasing amounts of HCV NS5A produced from infectious HCV enhanced the interaction between HNF-1α and HSC70.

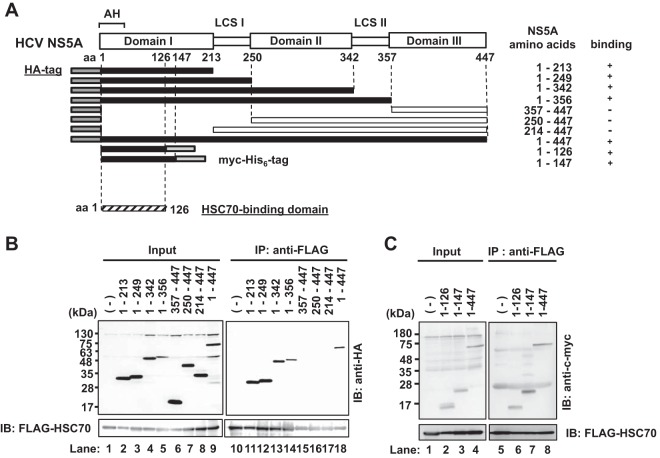

HSC70 interacts with domain I of NS5A protein.

To map the HSC70-binding domain on NS5A protein, we performed coimmunoprecipitation analyses using a series of NS5A deletion mutants (Fig. 3A). Huh-7.5 cells were expressed with FLAG-HSC70 together with a series of NS5A mutants. FLAG-HSC70 was found to be coimmunoprecipitated with all of the HA-NS5A proteins except HA-NS5A(357–447) (deletion mutant with the deletion of aa 357 to aa 447), HA-NS5A(250–447), and HA-NS5A(214–447) (Fig. 3B, 1st panel, lanes 15 to 17), suggesting that domain I of NS5A is important for the HSC70 binding. FLAG-HSC70 protein was also coimmunoprecipitated with NS5A(1–126)-myc-His6 and NS5A(1–147)-myc-His6 (Fig. 3C, 1st panel, lanes 6 to 8). These results indicate that the region from aa 1 to 126 of NS5A is important for the interaction with HSC70. We reported that the region spanning from aa 121 to aa 126 of NS5A is important for its interaction with HNF-1α (12). These two results raise a possibility that the HNF-1α–HSC70 interaction may be bridged by NS5A protein.

FIG 3.

Mapping of the HSC70-binding domain on NS5A protein. (A) Schematic representation of the HCV NS5A protein. NS5A consists of three domains (domains I, II, and III) separated by low-complexity sequences (LCS I and II). The position of the amino-terminal amphipathic helix membrane anchor is shown as “AH.” The NS5A deletion mutants contain amino acids of NS5A as indicated. Each NS5A deletion mutant contains either the HA tag in the N terminus or the myc-His6 tag in the C terminus. The dark gray region represents the HA tag sequence. The light gray region represents the myc-His6 tag. Closed boxes represent proteins that bound specifically to HSC70 protein, and open boxes represent those that did not bind. (B, C) Huh-7.5 cells were transfected with each NS5A mutant plasmid together with pCAG-FLAG-HSC70. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG beads, followed by immunoblotting with rabbit anti-HA PAb (B, upper panel, right) or anti-c-myc PAb (C, upper panel, right). Input samples were immunoblotted with rabbit anti-HA PAb (B, upper panel, left), anti-c-myc PAb (C, upper panel, left), or anti-FLAG MAb (B and C, bottom panels).

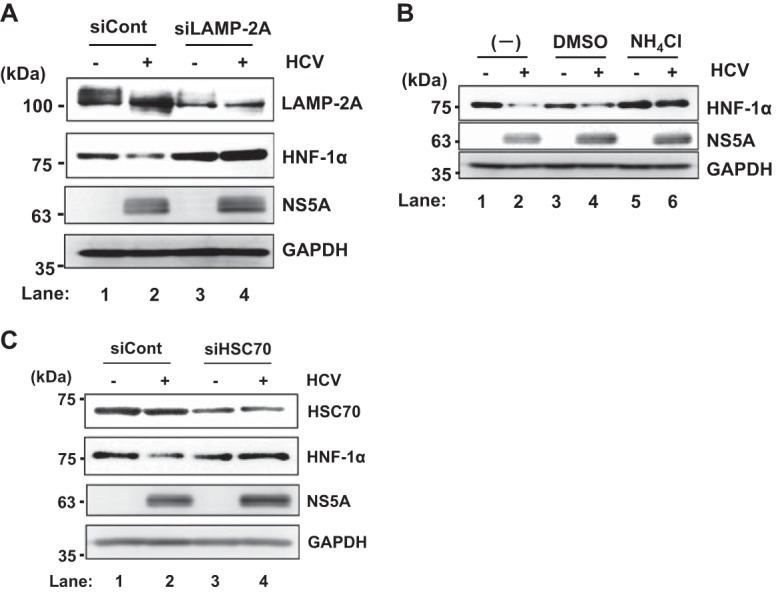

The HCV-induced degradation of HNF-1α protein was restored by siRNA knockdown of lysosomal receptor LAMP-2A.

To determine whether LAMP-2A, a lysosomal receptor, plays a role in the HCV-induced degradation of HNF-1α protein, LAMP-2A mRNA was knocked down by siRNA. We observed that siRNA knockdown of LAMP-2A restored the HCV-induced degradation of HNF-1α protein in HCV J6/JFH1-infected cells (Fig. 4A, 2nd panel, lane 4). This result suggests that LAMP-2A is involved in the HCV-induced degradation of HNF-1α protein.

FIG 4.

HCV infection-induced reduction of HNF-1α is restored by the knockdown of LAMP-2A by siRNA or treatment of the cells with NH4Cl. (A) Huh-7.5 cells (3.0 × 105 cells/6-well plate) were infected with HCV J6/JFH1 at an MOI of 2. At 24 h postinfection, the cells were transfected with either LAMP-2A-specific siRNA duplexes or negative-control scrambled-siRNA duplexes and cultured. At 48 h posttransfection, the cells were harvested and the cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-LAMP-2A PAb, anti-HNF-1α PAb, anti-NS5A PAb, and anti-GAPDH MAb. The level of GAPDH served as a loading control. (B) Huh-7.5 cells were plated at 3.0 × 105 cells/6-well plate and cultured for 12 h. The cells were infected with HCV J6/JFH1 at an MOI of 2 and treated with 5 mM NH4Cl for 24 h. The cells were then harvested, and the cell lysates analyzed by immunoblotting with goat anti-HNF-1α PAb, rabbit anti-NS5A PAb, or anti-GAPDH MAb. The level of GAPDH served as a loading control. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide. (C) Huh-7.5 cells (3.0 × 105 cells/12-well plate) were transfected with either HSC70-specific siRNA or negative-control scrambled siRNA and cultured. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were infected with HCV J6/JFH1 at an MOI of 2. At 48 h postinfection, the cells were harvested and the cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HSC70 MAb, anti-HNF-1α MAb, anti-NS5A PAb, and anti-GAPDH MAb. The level of GAPDH served as a loading control.

The HCV-induced degradation of HNF-1α protein was restored by lysosomal enzyme inhibitor NH4Cl.

To confirm whether the HCV-induced degradation of HNF-1α is due to lysosomal enzymes, we treated HCV J6/JFH1-infected Huh-7.5 cells with a lysosomal enzyme inhibitor, NH4Cl, which is known to neutralize the acidic lysosomal pH. Treatment of the cells with NH4Cl restored the levels of HNF-1α protein (Fig. 4B, 1st panel, lane 6). This result is consistent with the notion that HCV infection induces the lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α protein via CMA.

The HCV-induced degradation of HNF-1α protein was restored by siRNA knockdown of HSC70.

To determine whether HSC70 plays a role in the HCV-induced degradation of HNF-1α protein, HSC70 mRNA was knocked down by siRNA. We observed that siRNA knockdown of HSC70 restored the HCV-induced degradation of HNF-1α protein in HCV J6/JFH1-infected cells (Fig. 4C, 2nd panel, lane 4). This result suggests that HSC70 is involved in the HCV-induced degradation of HNF-1α protein. Taken together, these results suggest that HCV infection induces the lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α protein via CMA.

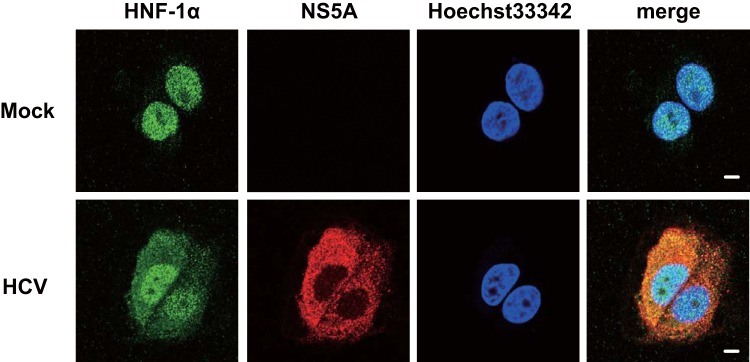

HCV NS5A is colocalized with endogenous HNF-1α in HCV J6/JFH1-infected cells.

To confirm whether NS5A is colocalized with endogenous HNF-1α in HCV-infected cells, we performed immunofluorescence staining. The immunofluorescence staining revealed that HNF-1α was mainly localized in the nucleus in the mock-infected cells. However, HNF-1α was localized both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm in HCV J6/JFH1-infected cells. Immunofluorescence staining demonstrated that NS5A was colocalized with endogenous HNF-1α in the cytoplasm in HCV J6/JFH1-infected cells (Fig. 5, 2nd panel, merge).

FIG 5.

HCV NS5A is colocalized with endogenous HNF-1α in HCV-infected cells. Huh-7.5 cells were plated at 1.0 × 105 cells/24-well plate and cultured for 12 h. Cells were infected with HCV J6/JFH1 at an MOI of 2. At 6 days postinfection, the cells were stained with anti-HNF-1α MAb followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (green) and anti-NS5A PAb followed by Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (red). The cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 for the nuclei (blue). The stained cells were examined using a Zeiss LSM 700 scanning laser confocal microscope and image software. Scale bars, 10 μm.

NS5A is colocalized with endogenous HNF-1α in the lysosome in HCV J6/JFH1-infected cells.

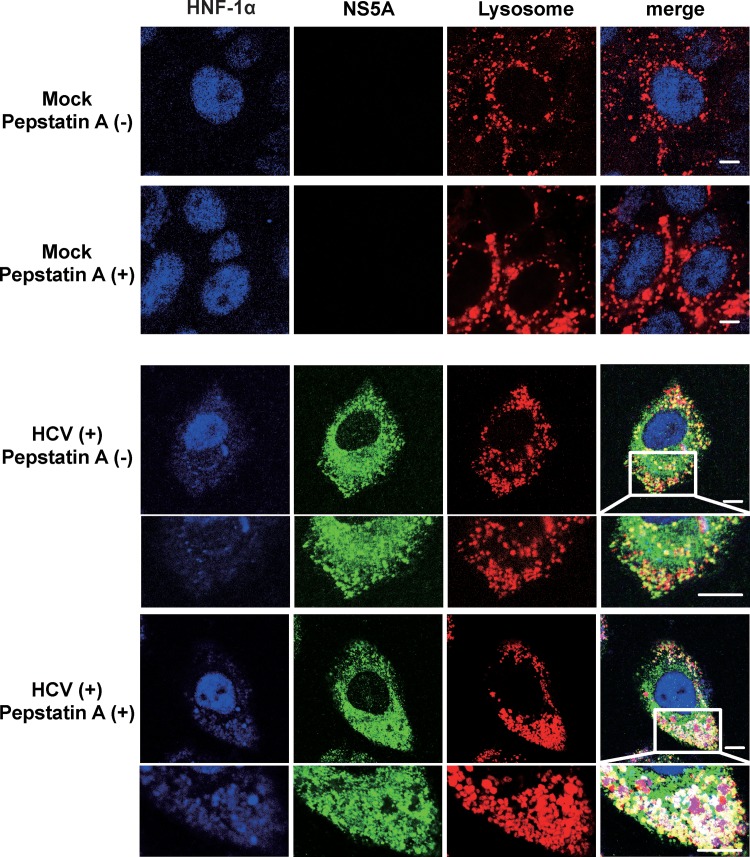

To confirm the subcellular colocalization of NS5A and HNF-1α in the lysosome, we performed immunofluorescence staining using LysoTracker. In the absence of lysosome protease inhibitor pepstatin A, merged white signals were hardly detected in HCV J6/JFH1-infected cells (Fig. 6, 2nd panel, merge, enlarged image). In contrast, merged white signals were clearly observed in the presence of pepstatin A, suggesting that pepstatin A inhibited the lysosomal degradation of FLAG-HNF-1α, and the colocalization of FLAG-HNF-1α with NS5A in the lysosome was detectable (Fig. 6, 3rd panel, merge, enlarged image).

FIG 6.

HCV NS5A is colocalized with HNF-1α in the lysosome. Huh-7.5 cells were plated at 1.0 × 105 cells/24-well plate and cultured for 12 h. Cells were infected with HCV J6/JFH1 at an MOI of 2. At 4 days postinfection, 20 μM pepstatin A was administered to the cells as indicated. At 6 days postinfection, the cells were stained with anti-HNF-1α MAb followed by Alexa Fluor 405-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (blue), anti-NS5A PAb followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (green), and LysoTracker (red). The stained cells were examined using a Zeiss LSM 700 scanning laser confocal microscope and image software. Scale bars, 10 μm.

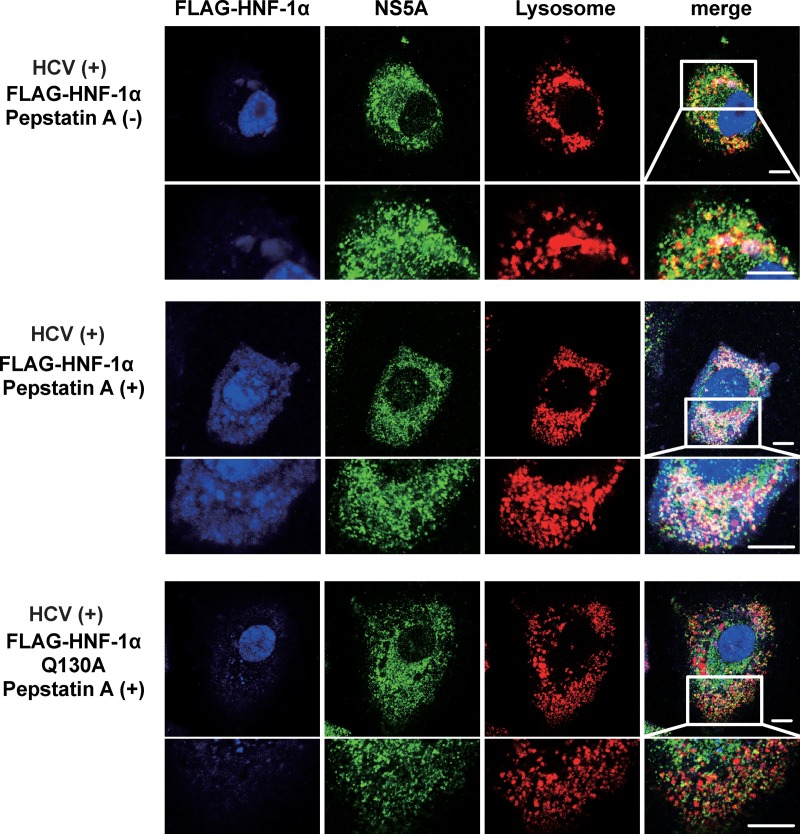

Pepstatin A restored the HCV NS5A-induced, CMA-mediated lysosomal degradation of FLAG-HNF-1α.

To determine whether HCV NS5A promotes the lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α via CMA, Huh-7.5 cells infected with HCV J6/JFH1 were cotransfected with either pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α or pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A and were treated with or without pepstatin A. Immunofluorescence staining revealed that merged white signals were slightly detected in the absence of pepstatin A (Fig. 7, 1st panel, merge, enlarged image), whereas merged white signals were increased in the presence of pepstatin A (Fig. 7, 2nd panel, merge, enlarged image). In contrast, merged white signals were not detected in the cells expressing FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A even in the presence of pepstatin A (Fig. 7, 3rd panel, merge). These results suggest that pepstatin A restored the HCV NS5A-induced, CMA-mediated lysosomal degradation of FLAG-HNF-1α.

FIG 7.

Pepstatin A restored the HCV NS5A-induced CMA-mediated lysosomal degradation of FLAG-HNF-1α. Huh-7.5 cells were plated at 1.0 × 105 cells/24-well plate and cultured for 12 h. Cells were infected with HCV J6/JFH1 at an MOI of 2. At 4 h postinfection, the cells were transfected with either pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α or pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α Q130A. After transfection, 20 μM pepstatin A was administered to the cells as indicated. At 6 days postinfection, the cells were stained with anti-FLAG MAb followed by Alexa Fluor 405-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (blue), anti-NS5A PAb followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (green), and LysoTracker (red). These stained cells were examined using a Zeiss LSM 700 scanning laser confocal microscope and image software. Scale bars, 10 μm.

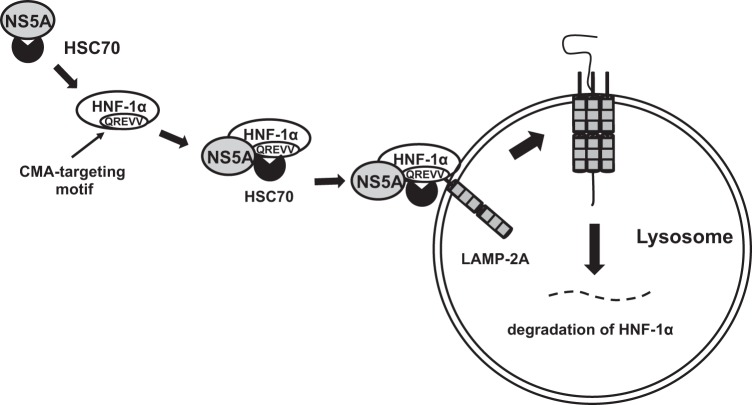

Taken together, we propose a model in which HCV NS5A recruits HSC70 to HNF-1α, leading to recognition of the NS5A-HSC70-HNF-1α protein complexes by LAMP-2A in the cytosolic side of the lysosomal membrane, thereby promoting the lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α protein via CMA (Fig. 8).

FIG 8.

A proposed mechanism of the HCV NS5A-induced lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α via CMA. HCV NS5A interacts with HSC70 and recruits HSC70 to HNF-1α protein through an interaction between NS5A and HNF-1α. HSC70 interacts with HNF-1α at its CMA-targeting motif. Protein complexes are delivered to the lysosome by HSC70. HSC70 is recognized by LAMP2A, a lysosomal membrane protein. HNF-1α protein gets unfolded and translocated into the lysosome. HNF-1α is degraded in the lysosome by lysosomal proteases.

DISCUSSION

Here, we sought to clarify the molecular mechanisms of the HCV NS5A-induced selective lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α protein. We discovered that HNF-1α protein contains a CMA-targeting motif in the region spanning from aa 130 to aa 134 within the POUs domain. Our immunoprecipitation analysis revealed that the CMA-targeting motif is crucial for the interaction between HNF-1α and HSC70 (Fig. 1). Immunoprecipitation analysis also revealed that NS5A interacted with HSC70 and that increasing amounts of NS5A enhanced the association of HNF-1α with HSC70 (Fig. 2).

We mapped the HSC70-binding domain on the HCV NS5A protein and found that the region spanning from aa 1 to aa 126 is important for the interaction with HSC70. Moreover, siRNA knockdown of LAMP-2A recovered the degradation of HNF-1α, indicating that the degradation of HNF-1α induced by HCV infection is dependent on LAMP-2A and HSC70 (Fig. 4). Immunofluorescence staining revealed that NS5A is colocalized with HNF-1α in the lysosome (Fig. 5 and 6). HCV NS5A promotes the lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α via the CMA-targeting motif (Fig. 6 and 7). Taken together, these results suggest that HCV NS5A protein interacts with HSC70 and recruits HSC70 to HNF-1α through a protein-protein interaction, thereby promoting the lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α via CMA (Fig. 8).

The involvement of CMA in the lysosomal degradation of interferon alpha receptor-1 (IFNAR1) in free fatty acid (FFA)-treated, HCV-infected cells was reported previously (20). IFNAR1 interacts with HSC70 and LAMP-2A. IFNAR1 contains a CMA-targeting motif (QKVEV) at aa 34 to aa 38 in the human IFNAR1 protein and is degraded via CMA in HCV-infected, FFA-treated cells (20). In the present study, our analyses demonstrated that HCV NS5A protein interacts with both HNF-1α and HSC70 at domain I of NS5A and recruits HSC70 to HNF-1α, thereby promoting CMA. To our knowledge, this is the first report clarifying the molecular mechanism of CMA induced by HCV infection.

CMA is a highly selective subtype of autophagy that directly carries a substrate protein into the lysosomal lumen using HSC70 and LAMP-2A (17). Substrate proteins contain a CMA-targeting motif. Thus, the cytosolic chaperone HSC70 selectively identifies a target protein, leading to facilitation of the delivery to the lysosomal surface (21, 22). All substrate proteins contain the CMA-targeting motif for the selectivity of CMA. Our present results demonstrated that the HNF-1α protein contains the CMA-targeting motif in its POUs domain (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, HCV NS5A interacts with the POUs domain of HNF-1α (12). These findings suggest that HCV NS5A, HSC70, and HNF-1α form a protein complex. We observed the colocalization of NS5A and HNF-1α in the lysosome when cells were treated with a lysosomal enzyme inhibitor, pepstatin A. We thus propose that HCV NS5A interacts with HSC70 and recruits HSC70 to the substrate HNF-1α, thereby promoting lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α via CMA. Further studies are required to clarify the molecular mechanisms of the unfolding of HNF-1α and the translocation into the lysosome.

A number of studies have suggested that autophagy (i.e., macroautophagy) plays some roles in the HCV life cycle (23). HCV infection induces autophagy both in cell culture and in the hepatocytes of chronic hepatitis C patients (24–26). Several groups have reported that HCV infection may indirectly or directly induce autophagy (27, 28). HCV also uses autophagy to promote its amplification by suppressing innate immune responses (29). Although the exact mechanisms remain to be elucidated, autophagy plays a positive role in HCV replication (23).

CMA is very different from macroautophagy due to the unique way in which its substrates, mainly cytosolic proteins, enter the lysosome (17, 30). Proteins degraded by CMA are identified one-by-one by HSC70, which delivers them to the surface of the lysosome. CMA contributes to two crucial functions in cellular physiology: the maintenance of energy homeostasis and protein quality control (17). Evidence is accumulating that CMA is involved in the pathogenesis of various diseases, including severe neurodegenerative disorders (Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease) (31–33), cancer (34), and renal diseases (35). Little is known about the involvement of CMA in viral diseases. It was reported that CMA targets IFNAR1 for degradation in the lysosome in FFA-treated, HCV-infected cell culture (20, 36) and that CMA protein BAG3 negatively regulates Ebola virus and Marburg virus VP40 matrix protein-mediated egress (37). Here, we demonstrated that HCV NS5A protein plays an important role in the CMA-dependent degradation of HNF-1α. The results of the present study, together with those of our previous studies (10–12), suggest that HCV uses CMA for the selective degradation of HNF-1α, thereby affecting the glucose metabolism in HCV-infected cells. These studies raise the intriguing possibility that other viruses may also manipulate CMA to facilitate viral pathogenesis and/or viral replication.

Our group and many other groups have been investigating NS5A-interacting proteins. More than 130 host proteins have been identified as NS5A-interacting proteins (11, 38–41). We are currently examining the potential CMA-targeting motif in NS5A-interacting proteins. Among the NS5A-interacting proteins, we have already observed that many NS5A-binding proteins contain a potential CMA-targeting motif. Further investigations are required to clarify the physiological relevance of the CMA-dependent degradation of host proteins in HCV infection.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that HCV NS5A protein promotes the association of HNF-1α with HSC70. The knockdown of LAMP-2A restored the HCV-induced lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α protein. We propose that HCV NS5A interacts with HSC70 and recruits HSC70 to HNF-1α, thereby promoting the lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α via CMA. We reported that HCV infection suppresses GLUT2 gene expression via lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α protein and that HCV NS5A interacts with HNF-1α and promotes the lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α protein (11, 12). Taking our previous reports and the current study into account, we propose that HCV NS5A may promote the lysosomal degradation of HNF-1α protein via CMA, thereby suppressing GLUT2 gene expression. Further investigations of HCV NS5A-induced CMA-dependent degradation of host proteins may contribute to our understanding of HCV pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

A human hepatoma cell line, Huh-7.5 (42), was kindly provided by C. M. Rice (The Rockefeller University, NY). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (high glucose) with l-glutamine (Wako, Osaka, Japan) and supplemented with 50 IU/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Biowest, Nuaillé, France), and 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen, New York, NY) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were transfected with plasmid DNA using FuGene 6 transfection reagents (Promega, Madison, WI). The pFL-J6/JFH1 plasmid, which encodes the entire viral genome of a chimeric strain of HCV-2a, JFH1 (5), was kindly provided by C. M. Rice. The HCV genome RNA was synthesized in vitro using pFL-J6/JFH1 as a template and was transfected into Huh-7.5 cells by electroporation (4, 43, 44). The virus produced in the culture supernatant was used for infection experiments (11, 43).

Expression plasmids.

The expression plasmids for NS5A and a series of NS5A deletion mutants constructed as hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged or myc-His6-tagged proteins have been described previously (11, 12, 38, 45). The expression plasmid pEF-FLAG-NA5A (46) was kindly provided by Y. Matsuura (Osaka University, Osaka, Japan). The plasmid pCAG-myc-HSC70-HA (47) was kindly provided by H. Aizaki (National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, Japan).

The cDNA fragment of HSC70 was amplified by PCR using pCAG-myc-HSC70-HA as the template. The specific primers used for the PCR were as follows: sense primer, 5′-TCGAGCTCAGCGGCCGCCATGTCCAAGGGACCTGCA-3′, and anti-sense primer, 5′-AGTGAATTCGCGGCCGCTTAATCAACCTCTTCAAT-3′. The amplified PCR product was purified and inserted into the NotI site of pCAG-FLAG using an In-Fusion HD cloning kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA). The Q130A and Q130A/R131A point mutants of HNF-1α were constructed by overlap extension PCR using pCAG-FLAG-HNF-1α as the template. The specific primers used for that PCR were as follows: sense primer (Q130A), 5′-CACAACATCCCAGCGCGGGAGGTGGTCGAT-3′; antisense primer (Q130A), 5′-ATCGACCACCTCCCGCGCTGGGATGTTGTG-3′; sense primer (Q130A/R131A), 5′-CACAACATCCCAGCGGCGGAGGTGGTCGAT-3′; and antisense primer (Q130A/R131A), 5′-ATCGACCACCTCCGCCGCTGGGATGTTGTG-3′. The sequences of the inserts were extensively verified by sequencing (Eurofins Genomics, Tokyo). The other primer sequences used in this study are available from the authors upon request.

Antibodies.

The mouse monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) used in this study were anti-FLAG (M2) MAb (F-3165; Sigma), anti-HSC70 MAb (B-6; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-c-Myc MAb (9E10; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) MAb (MAB374; Millipore, Billerica, MA). The rabbit polyclonal antibodies (PAbs) used in this study were anti-HA PAb (H-6908; Sigma, St. Louis, MO), anti-LAMP-2A PAb (ab18528; Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and anti-c-Myc PAb (A-14; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The goat PAb used in this study was goat anti-HNF-1α PAb (sc-6548; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA), HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology), and HRP-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used as secondary antibodies.

Immunoblot analysis.

Immunoblot analysis was performed essentially as described previously (11, 44, 48). The cell lysates were separated by 10% or 12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). The membranes were incubated with primary antibody, followed by incubation with a peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. The positive bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Immunoprecipitation.

Cultured cells were lysed with a buffer containing 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 0.1% SDS, 1% sodium deoxycholic acid, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail cOmplete (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The lysate was centrifuged at 12,500 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was immunoprecipitated with appropriate antibodies. Immunoprecipitation was performed as described previously (11, 48). Briefly, the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma) or protein A-Sepharose 4 fast flow (GE Healthcare) incubated with appropriate antibodies at 4°C for 5 h. After being washed with the lysis buffer five times, the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting.

siRNA transfection.

HCV-infected Huh-7.5 cells or uninfected control cells were transfected with 20 pmol of either LAMP-2A-specific siRNA (siLAMP2A; Sigma Genosys, Hokkaido, Japan) or negative-control scrambled siRNA (“siScr” in siRNA designations) duplexes (Sigma Genosys) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) for 48 h according to the manufacturer's instructions. The LAMP2A siRNA target sequences and siScrLAMP2A were as follows: siLAMP2A, 5′-CUGCAAUCUGAUUGAUUAUU-3′, and siScrLAMP2A, 5′-GUGACUUUACAUCAUUUAGU-3′. HSC70 siRNA (sc-29349; Santa Cruz Biotechnologies) was used for knockdown of HSC70 mRNA. The siScrHSC70 target sequence was as follows: 5′-GGAACAUGAACGAUCAACU-3′.

Immunofluorescence staining.

Huh-7.5 cells cultured on glass coverslips were incubated with LysoTracker (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) for 2 h at 37°C. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 15 min. After being washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the cells were permeabilized for 15 min at room temperature with PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and incubated in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin to block nonspecific reactions for 60 min. The cells were incubated with Can Get Signal immunostain solution A (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan) containing mouse anti-DDDDK antibody (PM020; MBL, Nagoya, Japan) and rabbit anti-NS5A antibody at room temperature for 60 min. The cells were washed four times with PBS and incubated with Can Get Signal immunostain solution A containing Alexa Fluor 405-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Life Technologies, Eugene, OR) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Life Technologies) at room temperature for 60 min. The cells were washed four times with PBS, mounted on glass slides, and examined by confocal microscope (LSM 700; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to C. M. Rice (Rockefeller University, New York, NY) for providing us Huh-7.5 cells and pFL-J6/JFH1. We thank Y. Kozaki and Y. Sakahara for secretarial work.

This research was supported by Basic and Clinical Research on Hepatitis from Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, AMED, under grant numbers JP17fk0210304 and JP18fk0210040. This work was also supported in part by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT), Daiichisankyo, Astellas, and Hyogo Science and Technology Association. C.M. is supported by the Program for Promoting the Reform of National Universities of MEXT.

C.M. and I.S. conceived and designed the experiments; C.M., L.D., N.M., and T.A. performed the experiments; C.M., L.D., N.M., T.A., K.K., and I.S. analyzed the data; and C.M. and I.S. wrote the paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ray SC, Bailey JR, Thomas DL. 2013. Hepatitis C virus, p 795–824. In Knipe DM, Howley PM, Cohen JI, Griffin DE, Lamb RA, Martin MA, Racaniello VR, Roizman B (ed), Fields virology, 6th ed, vol 1 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lohmann V, Korner F, Koch J, Herian U, Theilmann L, Bartenschlager R. 1999. Replication of subgenomic hepatitis C virus RNAs in a hepatoma cell line. Science 285:110–113. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5424.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blight KJ. 2000. Efficient initiation of HCV RNA replication in cell culture. Science 290:1972–1974. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5498.1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T, Date T, Miyamoto M, Zhao Z, Murthy K, Habermann A, Krausslich HG, Mizokami M, Bartenschlager R, Liang TJ. 2005. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat Med 11:791–796. doi: 10.1038/nm1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindenbach BD, Evans MJ, Syder AJ, Wolk B, Tellinghuisen TL, Liu CC, Maruyama T, Hynes RO, Burton DR, McKeating JA, Rice CM. 2005. Complete replication of hepatitis C virus in cell culture. Science 309:623–626. doi: 10.1126/science.1114016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hayes CN, Chayama K. 2015. Emerging treatments for chronic hepatitis C. J Formos Med Assoc 114:204–215. doi: 10.1016/j.jfma.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mason AL, Lau JY, Hoang N, Qian K, Alexander GJ, Xu L, Guo L, Jacob S, Regenstein FG, Zimmerman R, Everhart JE, Wasserfall C, Maclaren NK, Perrillo RP. 1999. Association of diabetes mellitus and chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 29:328–333. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Negro F, Alaei M. 2009. Hepatitis C virus and type 2 diabetes. World J Gastroenterol 15:1537–1547. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Negro F. 2011. Mechanisms of hepatitis C virus-related insulin resistance. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 35:358–363. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kasai D, Adachi T, Deng L, Nagano-Fujii M, Sada K, Ikeda M, Kato N, Ide YH, Shoji I, Hotta H. 2009. HCV replication suppresses cellular glucose uptake through down-regulation of cell surface expression of glucose transporters. J Hepatol 50:883–894. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsui C, Shoji I, Kaneda S, Sianipar IR, Deng L, Hotta H. 2012. Hepatitis C virus infection suppresses GLUT2 gene expression via downregulation of hepatocyte nuclear factor 1alpha. J Virol 86:12903–12911. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01418-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matsui C, Sianipar IR, Minami N, Deng L, Hotta H, Shoji I. 2015. A single-amino-acid mutation in hepatitis C virus NS5A disrupts physical and functional interaction with the transcription factor HNF-1alpha. J Gen Virol 96:2200–2205. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.000179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madrigal-Matute J, Cuervo AM. 2016. Regulation of liver metabolism by autophagy. Gastroenterology 150:328–339. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.09.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiang HL, Dice JF. 1988. Peptide sequences that target proteins for enhanced degradation during serum withdrawal. J Biol Chem 263:6797–6805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dice JF. 1990. Peptide sequences that target cytosolic proteins for lysosomal proteolysis. Trends Biochem Sci 15:305–309. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuervo AM, Dice JF. 1996. A receptor for the selective uptake and degradation of proteins by lysosomes. Science 273:501–503. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5274.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaushik S, Cuervo AM. 2012. Chaperone-mediated autophagy: a unique way to enter the lysosome world. Trends Cell Biol 22:407–417. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sahu R, Kaushik S, Clement CC, Cannizzo ES, Scharf B, Follenzi A, Potolicchio I, Nieves E, Cuervo AM, Santambrogio L. 2011. Microautophagy of cytosolic proteins by late endosomes. Dev Cell 20:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khachatoorian R, Ganapathy E, Ahmadieh Y, Wheatley N, Sundberg C, Jung CL, Arumugaswami V, Raychaudhuri S, Dasgupta A, French SW. 2014. The NS5A-binding heat shock proteins HSC70 and HSP70 play distinct roles in the hepatitis C viral life cycle. Virology 454–455:118–127. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kurt R, Chandra PK, Aboulnasr F, Panigrahi R, Ferraris P, Aydin Y, Reiss K, Wu T, Balart LA, Dash S. 2015. Chaperone-mediated autophagy targets IFNAR1 for lysosomal degradation in free fatty acid treated HCV cell culture. PLoS One 10:e0125962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li W, Yang Q, Mao Z. 2011. Chaperone-mediated autophagy: machinery, regulation and biological consequences. Cell Mol Life Sci 68:749–763. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0565-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ebrahimi-Fakhari D, Saidi LJ, Wahlster L. 2013. Molecular chaperones and protein folding as therapeutic targets in Parkinson's disease and other synucleinopathies. Acta Neuropathol Commun 1:79. doi: 10.1186/2051-5960-1-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan ST, Ou JJ. 2017. Hepatitis C virus-induced autophagy and host innate immune response. Viruses 9:E224. doi: 10.3390/v9080224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ait-Goughoulte M, Kanda T, Meyer K, Ryerse JS, Ray RB, Ray R. 2008. Hepatitis C virus genotype 1a growth and induction of autophagy. J Virol 82:2241–2249. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02093-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rautou PE, Cazals-Hatem D, Feldmann G, Mansouri A, Grodet A, Barge S, Martinot-Peignoux M, Duces A, Bieche I, Lebrec D, Bedossa P, Paradis V, Marcellin P, Valla D, Asselah T, Moreau R. 2011. Changes in autophagic response in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Am J Pathol 178:2708–2715. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sir D, Chen WL, Choi J, Wakita T, Yen TS, Ou JH. 2008. Induction of incomplete autophagic response by hepatitis C virus via the unfolded protein response. Hepatology 48:1054–1061. doi: 10.1002/hep.22464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medvedev R, Ploen D, Spengler C, Elgner F, Ren H, Bunten S, Hildt E. 2017. HCV-induced oxidative stress by inhibition of Nrf2 triggers autophagy and favors release of viral particles. Free Radic Biol Med 110:300–315. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aweya JJ, Mak TM, Lim SG, Tan YJ. 2013. The p7 protein of the hepatitis C virus induces cell death differently from the influenza A virus viroporin M2. Virus Res 172:24–34. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shrivastava S, Raychoudhuri A, Steele R, Ray R, Ray RB. 2011. Knockdown of autophagy enhances the innate immune response in hepatitis C virus-infected hepatocytes. Hepatology 53:406–414. doi: 10.1002/hep.24073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cuervo AM. 2011. Chaperone-mediated autophagy: Dice's ‘wild’ idea about lysosomal selectivity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 12:535–541. doi: 10.1038/nrm3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wong E, Cuervo AM. 2010. Autophagy gone awry in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Neurosci 13:805–811. doi: 10.1038/nn.2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Martinez-Vicente M, Kruger U, Kaushik S, Wong E, Mandelkow EM, Cuervo AM, Mandelkow E. 2009. Tau fragmentation, aggregation and clearance: the dual role of lysosomal processing. Hum Mol Genet 18:4153–4170. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu H, Wang P, Song W, Sun X. 2009. Degradation of regulator of calcineurin 1 (RCAN1) is mediated by both chaperone-mediated autophagy and ubiquitin proteasome pathways. FASEB J 23:3383–3392. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-134296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lv L, Li D, Zhao D, Lin R, Chu Y, Zhang H, Zha Z, Liu Y, Li Z, Xu Y, Wang G, Huang Y, Xiong Y, Guan KL, Lei QY. 2011. Acetylation targets the M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase for degradation through chaperone-mediated autophagy and promotes tumor growth. Mol Cell 42:719–730. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sooparb S, Price SR, Shaoguang J, Franch HA. 2004. Suppression of chaperone-mediated autophagy in the renal cortex during acute diabetes mellitus. Kidney Int 65:2135–2144. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dash S, Chava S, Aydin Y, Chandra PK, Ferraris P, Chen W, Balart LA, Wu T, Garry RF. 2016. Hepatitis C virus infection induces autophagy as a prosurvival mechanism to alleviate hepatic ER-stress response. Viruses 8:E150. doi: 10.3390/v8050150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang J, Sagum CA, Bedford MT, Sidhu SS, Sudol M, Han Z, Harty RN. 2017. Chaperone-mediated autophagy protein BAG3 negatively regulates Ebola and Marburg VP40-mediated egress. PLoS Pathog 13:e1006132. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sianipar IR, Matsui C, Minami N, Gan X, Deng L, Hotta H, Shoji I. 2015. Physical and functional interaction between hepatitis C virus NS5A protein and ovarian tumor protein deubiquitinase 7B. Microbiol Immunol 59:466–476. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ross-Thriepland D, Harris M. 2015. Hepatitis C virus NS5A: enigmatic but still promiscuous 10 years on! J Gen Virol 96(Pt 4):727–738. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen M, Gan X, Yoshino K, Kitakawa M, Shoji I, Deng L, Hotta H. 2016. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein interacts with lysine methyltransferase SET and MYND domain-containing 3 and induces activator protein 1 activation. Microbiol Immunol 60:407–417. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minami N, Abe T, Deng L, Matsui C, Fukuhara T, Matsuura Y, Shoji I. 2017. Unconjugated interferon-stimulated gene 15 specifically interacts with the hepatitis C virus NS5A protein via domain I. Microbiol Immunol 61:287–292. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blight KJ, McKeating JA, Rice CM. 2002. Highly permissive cell lines for subgenomic and genomic hepatitis C virus RNA replication. J Virol 76:13001–13014. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.24.13001-13014.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bungyoku Y, Shoji I, Makine T, Adachi T, Hayashida K, Nagano-Fujii M, Ide YH, Deng L, Hotta H. 2009. Efficient production of infectious hepatitis C virus with adaptive mutations in cultured hepatoma cells. J Gen Virol 90:1681–1691. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.010983-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deng L, Adachi T, Kitayama K, Bungyoku Y, Kitazawa S, Ishido S, Shoji I, Hotta H. 2008. Hepatitis C virus infection induces apoptosis through a Bax-triggered, mitochondrion-mediated, caspase 3-dependent pathway. J Virol 82:10375–10385. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00395-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inubushi S, Nagano-Fujii M, Kitayama K, Tanaka M, An C, Yokozaki H, Yamamura H, Nuriya H, Kohara M, Sada K, Hotta H. 2008. Hepatitis C virus NS5A protein interacts with and negatively regulates the non-receptor protein tyrosine kinase Syk. J Gen Virol 89:1231–1242. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83510-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okamoto T, Nishimura Y, Ichimura T, Suzuki K, Miyamura T, Suzuki T, Moriishi K, Matsuura Y. 2006. Hepatitis C virus RNA replication is regulated by FKBP8 and Hsp90. EMBO J 25:5015–5025. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inoue Y, Aizaki H, Hara H, Matsuda M, Ando T, Shimoji T, Murakami K, Masaki T, Shoji I, Homma S, Matsuura Y, Miyamura T, Wakita T, Suzuki T. 2011. Chaperonin TRiC/CCT participates in replication of hepatitis C virus genome via interaction with the viral NS5B protein. Virology 410:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shirakura M, Murakami K, Ichimura T, Suzuki R, Shimoji T, Fukuda K, Abe K, Sato S, Fukasawa M, Yamakawa Y, Nishijima M, Moriishi K, Matsuura Y, Wakita T, Suzuki T, Howley PM, Miyamura T, Shoji I. 2007. E6AP ubiquitin ligase mediates ubiquitylation and degradation of hepatitis C virus core protein. J Virol 81:1174–1185. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01684-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]