ABSTRACT

Hendra virus (HeV) is a zoonotic paramyxovirus belonging to the genus Henipavirus. HeV is highly pathogenic, and it can cause severe neurological and respiratory illnesses in both humans and animals, with an extremely high mortality rate of up to 70%. Among the genes that HeV encodes, the matrix (M) protein forms an integral part of the virion structure and plays critical roles in coordinating viral assembly and budding. Nevertheless, the molecular mechanism of this process is not fully elucidated. Here, we determined the crystal structure of HeV M to 2.5-Å resolution. The dimeric structural configuration of HeV M is similar to that of Newcastle disease virus (NDV) M and is fundamental to protein stability and effective virus-like-particle (VLP) formation. Analysis of the crystal packing revealed a notable interface between the α1 and α2 helices of neighboring HeV M dimers, with key residues sharing degrees of sequence conservation among henipavirus M proteins. Structurally, a network of electrostatic interactions dominates the α1-α2 interactions, involving residues Arg57 from the α1 helix and Asp105 and Glu108 from the α2 helix. The disruption of the α1-α2 interactions using engineered charge reversal substitutions (R57E, R57D, and E108R) resulted in significant reduction or abrogation of VLP production. This phenotype was reversible with an R57E E108R mutant that was designed to partly restore salt bridge contacts. Collectively, our results define and validate previously underappreciated regions of henipavirus M proteins that are crucial for productive VLP assembly.

IMPORTANCE Hendra virus is a henipavirus associated with lethal infections in humans. It is classified as a biosafety level 4 (BSL4) agent, and there are currently no preventive or therapeutic treatments available against HeV. Vital to henipavirus pathogenesis, the structural protein M has been implicated in viral assembly and budding, as well as host-virus interactions. However, there is no structural information available for henipavirus M, and the basis of M-driven viral assembly is not fully elucidated. We demonstrate the first three-dimensional structure of a henipavirus M protein. We show the dimeric organization of HeV M as a basic unit for higher-order oligomerization. Additionally, we define key regions/residues of HeV M that are required for productive virus-like-particle formation. These findings provide the first insight into the mechanism of M-driven assembly in henipavirus.

KEYWORDS: Hendra, matrix, viral assembly, Hendra virus

INTRODUCTION

The family Paramyxoviridae comprises a collection of single-stranded RNA viruses that can cause a range of diseases in both humans and animals. Within the family, a subset of viruses belonging to the genus Henipavirus distinguish themselves from the other members, as they exhibit significantly larger genomes and display a wider range of host targets. The best-characterized members of the genus Henipavirus are Hendra virus (HeV) and Nipah virus (NiV), both of which are associated with lethal infections in humans, with mortality rates typically ranging between 50 and 100%. Despite this alarming fact, there are currently no effective therapeutic or preventive strategies against henipaviruses in humans, which makes them the only biosafety level 4 (BSL4) agents within the family Paramyxoviridae (1).

Paramyxoviruses are enveloped, pleomorphic, cytoplasmic viruses with a typical particle size of 40 to 1,900 nm (2, 3). The genomic core of paramyxoviruses consists of a helical assembly known as the ribonucleoprotein complex (RNP), encompassing the negative-sense single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) genome bound to the nucleocapsid (N) protein (4). The phosphoprotein (P) and large RNA-dependent RNA polymerase protein (L) also associate with the viral RNP, and they are required for transcription and genomic replication, respectively (5). Two glycoproteins are embedded in the viral membrane, the fusion protein (F) and the attachment protein (G), both of which are important for host membrane attachment and viral entry. The structural protein M (matrix) resides at the inner leaflet of the viral membrane while interacting with the cytoplasmic tail of the G protein (6, 7) and the viral RNP (8, 9). Beyond their structural roles, paramyxovirus M proteins have also been implicated in a wide range of protein-protein interactions with the host (10, 11), including nuclear proteins, such as fibrillarin (12) and ANP32B (13). In agreement with these observations, paramyxovirus M proteins have been demonstrated to undergo nucleus-cytoplasm trafficking during early stages of infection (14–19). This ability, which is a prerequisite for productive virion assembly and budding, was later shown, using Nipah virus M, to be dependent on a bipartite nuclear localizing signal (NLS) and a leucine-rich nuclear export signal (NES) (19, 20).

Many viruses exhibit short linear sequences known as late (L) domains that are required for efficient viral budding (21–27). The canonical sequences of the L domains are defined as P(T/S)AP, PPXY, and YPXL and are often interchangeable between species (28, 29). Mechanistically, the L domains facilitate viral exit by mediating protein-protein interaction with components of the host endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT), which is functionally associated with membrane remodeling and scission (30, 31). Interestingly, while paramyxovirus M proteins do not typically exhibit canonical L sequences, two homologous motifs in NiV M, namely, 62YMYL65 and 92YPLGVG97, have been previously proposed as putative L motifs, as mutations and deletions in these regions resulted in compromised viral budding (32, 33). Nonetheless, how these putative L motifs function remains unclear, as direct interactions between NiV M and components of ESCRT have not been identified to date.

While F, G, and M proteins have all been shown to coordinate budding and morphogenesis of paramyxoviruses to varying extents (34–39), the M protein is generally considered to be the major driving force. Indeed, in human parainfluenza virus type 1 (hPIV1) (35), Sendai virus (40), Nipah virus (32), measles virus (37), and Newcastle disease virus (NDV) (36), the expression of M proteins alone is sufficient to trigger virus-like-particle (VLP) production. Thus, understanding the architecture of M and its mechanism of assembly is an area of interest for many virologists. Currently, our structural knowledge of paramyxovirus M arises mainly from respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (41, 42), human metapneumovirus (hMPV) (43), and NDV (44), although RSV and hMPV have been recently reclassified as members of the Pneumoviridae. None of the henipavirus M proteins have been structurally characterized to date. Paramyxovirus and pneumovirus M proteins typically exist as dimers, and the assembly of virions is thought to occur by repetitive polymerization of dimeric M proteins into a grid-like array (43, 44). Combinational structural approaches have further highlighted discrete regions that mediate intermolecular contacts for higher-order assembly (43, 44). However, the specific residues involved and the nature of the interactions have not been fully elucidated.

The lack of structural information for henipavirus M proteins prompted us to research this theme further, using HeV M as an example. The sequences of M within the genus Henipavirus are highly homologous to that of HeV M, with at least 60% sequence identity in pairwise alignments. In contrast, HeV M is most similar to NDV M among the published M structures, despite limited sequence homology (∼20% sequence identity). Thus, the aim of the study was to develop protocols for the production and isolation of recombinant HeV M for structural characterization in order to better understand the process of viral assembly.

RESULTS

Overall structure of HeV M.

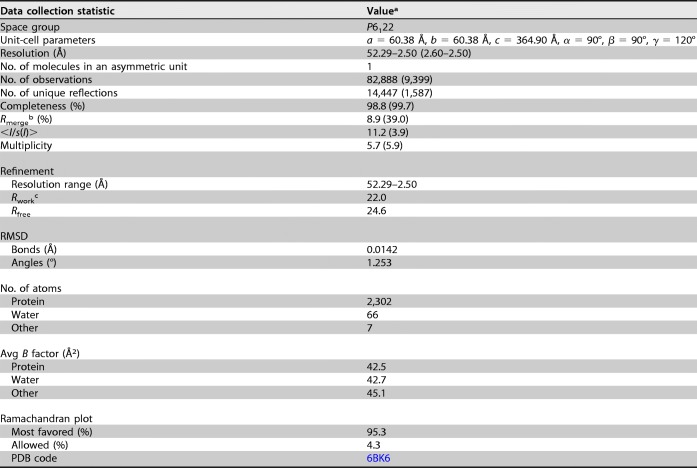

Recombinant HeV M was expressed with an N-terminal His tag followed by a tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease cleavage site. The stringent buffer conditions required for HeV M purification resulted in inefficient cleavage of the His tag (data not shown). Hence, the tagged full-length protein was used for crystallization. The crystal of HeV M, which diffracted to 2.5-Å resolution, belonged to the space group P6122. The structure was solved with molecular replacement using a polyalanine chain, derived from the published coordinate of NDV M (Protein Data Bank [PDB] code 4GIO), with one molecule in the asymmetric unit, as a search model. The data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in Table 1 (Rwork = 0.22; Rfree = 0.24).

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics for HeV M

aValues in parentheses represent the highest-resolution shell.

bRmerge = Σ|Ihkl − Σ<Ihkl>/Σ Ihkl.

cfactor = Σhkl |Fo| − |Fc|/Σhkl|Fo| (for all but 5% of the data, which were used to calculate Rfree).

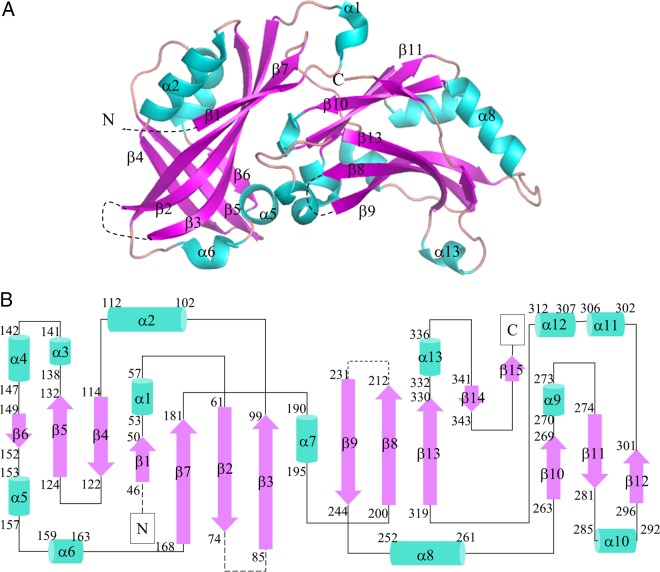

Figure 1 shows the secondary-structure topology of HeV M. HeV M encompasses two structurally similar domains that are positioned roughly perpendicular to each other. The N-terminal domain, which spans residues 1 to 180, is connected to the C-terminal domain (residues 191 to 352) via an 11-residue linker region that lacks secondary-structural features. Within each domain, the structural core is made up of two antiparallel β-sheets that are flanked by a number of α-helices away from the center. Three stretches of HeV M sequence were missing from the model—the entire N-terminal 44 residues, residues 75 to 84, and residues 214 to 231—as they were not seen in the electron density maps. This is likely attributable to the inherent structural flexibility (for all three regions) or to proteolytic degradation associated with the N-terminal region of the construct during the course of crystallization.

FIG 1.

Three-dimensional structure of HeV M protein. (A) The monomeric structure of HeV M comprises two similar domains that are at roughly 90° relative to each other. Each domain contains a β-sandwich core (magenta) and a number of α-helices (cyan). (B) Schematic representation of HeV M highlighting the secondary-structure elements; 280 out of 352 residues of the HeV M protein were modeled into the coordinates. Structurally flexible regions that were not built in the model are shown as dashed lines.

HeV M is dimeric in crystal structure.

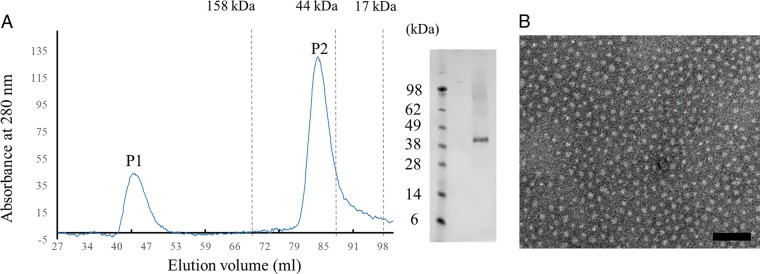

During the purification of HeV M with size exclusion chromatography (Fig. 2A), we observed that the protein eluted significantly earlier than the expected peak for monomeric M, suggesting that HeV M exists as dimers in solution. Additionally, we showed that recombinant HeV M could spontaneously form uniform and spherical particles under electron microscopy (EM), with a typical particle diameter of ∼7.5 nm (Fig. 2B), which is reminiscent of the size and shape of the dimeric M observed in hMPV (43). In agreement with these results, analysis of the packing of monomeric HeV M in the crystal lattice revealed head-to-tail organization of molecules, where the N-terminal domain of one monomer packs against the C-terminal domain of the other, a dimeric organization that is common to paramyxovirus M proteins (Fig. 3).

FIG 2.

Purification profile and electron microscopy image of recombinant HeV M. (A) Purification profile of recombinant HeV M using Superdex 200 10/60 size exclusion chromatography. Peak 1 (P1) represents irrelevant soluble aggregates derived from the culture lysate, while peak 2 contains the dimeric form of HeV M protein. Pooled and concentrated HeV M sample from peak 2 was analyzed by SDS-PAGE. (B) Electron microscopy image of purified recombinant HeV M. Scale bar, 100 nm.

FIG 3.

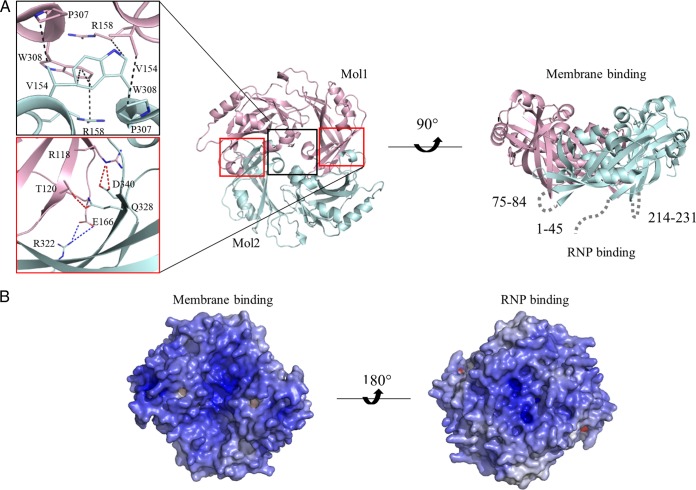

HeV M dimer in the crystal structure. (A) Structural overview of dimeric HeV M, with structurally flexible regions shown as gray dashed lines. The center of the dimerization interface (black box) is stabilized mainly by nonpolar interactions (black dashed lines), while the peripheral interfaces (red boxes) involve a number of side-chain-mediated H bonds (red dashed lines) and salt bridge contacts (blue dashed lines). (B) The electrostatic potential of the HeV M surface (calculated by APBS) is represented in a color scheme ranging from red (−20kBTe−1) to blue (+20kBTe−1).

The dimeric structure of HeV M is diamond shaped. The interface between the two protomers, which we refer to here as Mol1 and Mol2, is approximately 2,275 Å2. The dimerization interface is stabilized by a large number of polar and nonpolar interactions, with many of the side-chain-mediated contacts highly conserved across henipavirus M proteins. In this context, the center of the dimerization interface is driven predominantly by hydrophobic interactions contributed by equivalent residues of Mol1 and Mol2, including Val154 and Arg158 from the α5 helices, as well as Pro307and Trp308 from the α12 helices (Fig. 3A). Two identical sets of reciprocal interactions bridge Mol1 and Mol2, distal from the hydrophobic core. In one site, three side-chain-mediated polar contacts are involved, including Arg118 and Thr120 (Mol1), which establish H bonds with Asp340 and Gln328 (Mol2), respectively. Additional salt bridge contacts are formed between Glu166 (Mol1) and Arg322 (Mol2).

Along and perpendicular to the dimerization axis, the 2-dimensional measurements of the M dimer are approximately 70 Å by 70 Å. The dimer surface is concave on one side and convex on the other (Fig. 3). The concave surface is largely positively charged, which correlates with its primary role of associating with the negatively charged host membrane (45, 46). On the other hand, all three flexible regions in the HeV M model map to the convex surface, which is also positively charged. These loops are also the least conserved in sequence among henipavirus M proteins, particularly those in the N-terminal domain (residues 1 to 44 and 75 to 84) (see Fig. 6C). The combination of its surface charge and the flexible loops in the convex surface may reflect its roles in establishing protein-protein and/or protein-RNA interactions, such as contacting the viral RNP.

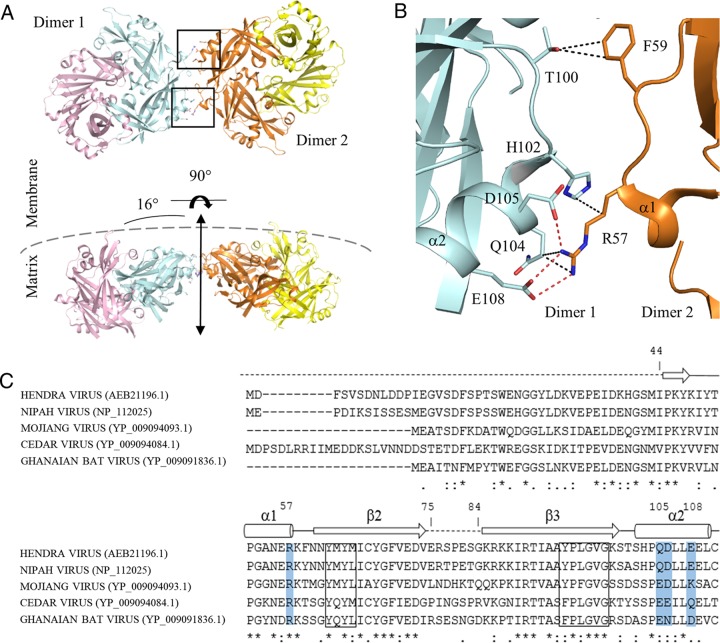

FIG 6.

Assembly of HeV M dimers. (A) Crystal packing of two HeV M dimers involving the α1 and α2 helices. Two sets of identical interactions are boxed in black. (B) Enlarged view of one set of the interdimer interface, focusing on residues in the α1 and α2 helices. Side chains are shown as sticks; the black dashed lines represent van der Waals contacts; the red dashed lines represent electrostatic interactions. (C) Sequence alignment of the N-terminal domains of henipavirus M proteins. The secondary-structural features of HeV M are shown as a guide. Charged side chains at the dimer-dimer interface are shaded in blue. Sequences corresponding to putative L domains are boxed. The accession numbers of the aligned M proteins are in parentheses.

Dimerization is required for HeV M stability and assembly.

Given that dimers of HeV M appear to represent the basic unit for higher-order M protein assembly, we hypothesized that the disruption of the dimerization interface via site-directed mutagenesis of the protomer-protomer contacts could potentially impair M-driven assembly. We tested the hypothesis by generating five alanine mutants of myc-tagged HeV M, targeting residues R118, T120, V154, R158, and E166. We transfected the HeV M variants into HEK293T cells for protein expression and VLP production, and we assessed the efficiency of assembly by comparing these values to those of the wild-type counterpart as a ratio of cellular protein expression to VLP. First, wild-type HeV M was detected both in the total cell lysate and in the medium after a sucrose cushion isolation step (Fig. 4A). This indicated that expression of HeV M alone was sufficient to drive the formation of VLP. The identity of the VLP sample was further confirmed by electron microscopy analysis, which demonstrated the typical morphology of the Hendra M VLP (47), with a particle size ranging between 80 and 120 nm (see Fig. 7C). The R118A, R158A, and E166A variants showed limited or no detectable levels of protein expression from the lysates, suggesting that residues that take part in dimerization of HeV M may be crucial for protein stability. Nevertheless, due to the limited amount of cellular protein expression, these mutants were excluded from our VLP analysis. In contrast, the T120A and V154 mutants demonstrated levels of expression comparable to that of wild-type HeV M, although the efficiency of VLP production (33.6% and 39.4%, respectively) was significantly lower than that of the wild type (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4B). Collectively, these results validated the dimeric configuration of HeV M observed in our structural model and revealed the key role of the HeV M dimers in conferring protein stability and in assembly.

FIG 4.

Residues in the dimerization interface are required for protein stability and VLP assembly. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected to express alanine mutants of HeV M proteins, as indicated. Total cell lysates and VLPs were processed and analyzed by Western blotting and densitometry. (B) The relative efficiency of VLP production was analyzed based on the VLP/total HeV M ratio. All values were normalized to the wild type (WT) (*, P < 0.05). The error bars represent standard errors of the mean from the results of three independent experiments.

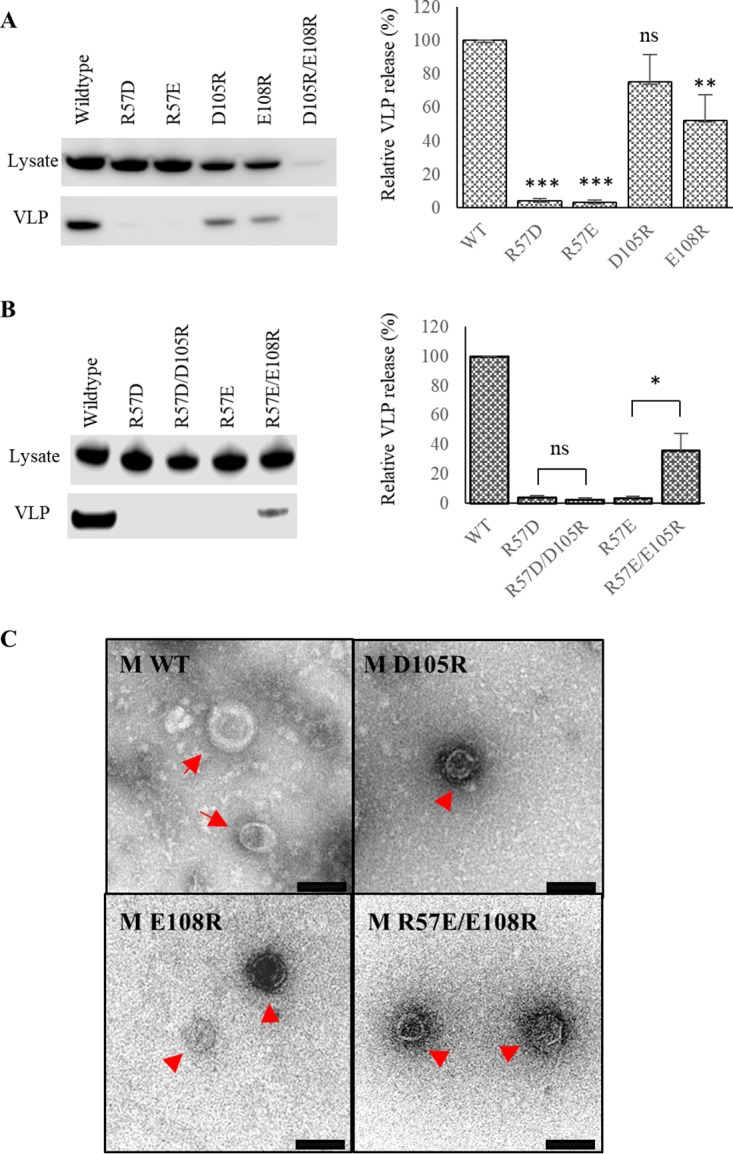

FIG 7.

Residues on the α1 and α2 helices of HeV M are required for VLP production. (A and B) HEK293T cells were transfected to produce charge reversal mutants of HeV M proteins targeting residues Arg57, Asp105, and Glu108. Total cell lysates and VLPs were isolated and analyzed by immunoblotting and densitometry (left). The relative efficiency of VLP production was calculated based on the VLP/total HeV M ratio (right). All values were normalized to the wild type. Three or more independent experiments were performed for each ratio, and the data were analyzed by one-sample t test. The error bars represent standard errors of the mean. (Bottom) Electron microscopy analysis of variants of HeV M VLPs (red arrows). Scale bars, 100 nm.

Structural comparison of paramyxovirus M proteins.

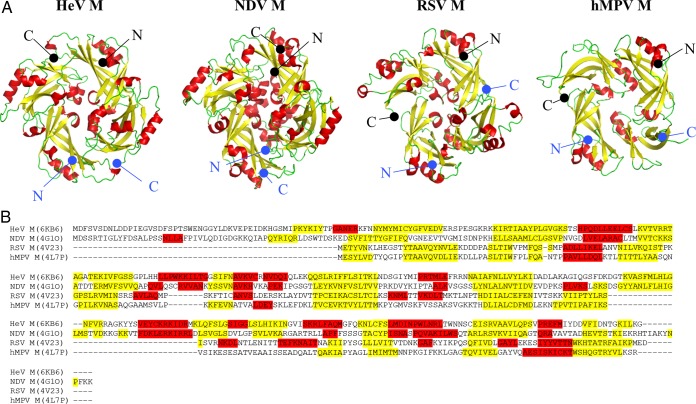

In a comparison of the HeV M coordinates to characterized structures in the Protein Data Bank using PDBefold (48), significant similarities to paramyxovirus and pneumovirus M structure were identified (Fig. 5). The most relevant hit was the NDV M (genus Avulavirus), which shares only ∼20% sequence identity with HeV M. The overall fold and size of NDV M closely resemble those of HeV M, with a root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 1.7 Å over 255 residues in a pairwise structural superimposition. The RSV and hMPV (genus Pneumovirus) M proteins also showed limited but significant structural homology with HeV M (z-scores of 9.9 and 5.5, respectively), despite sequence identities of approximately 10% with HeV M. The structures of the RSV and hMPV M proteins could be superimposed on HeV M with RMSD values of 2.7 over 209 residues and 3.4 over 199 residues, respectively. However, while the architectures of the RSV and hMPV M proteins are homologous to that of HeV M, the complexity of their secondary-structural contents is significantly reduced. This is most pronounced in the context of hMPV M, which comprises only 4 helices in each monomeric chain compared to 13 in HeV M. Nevertheless, the overall similarity of paramyxovirus and pneumovirus M proteins suggests evolutionarily similar mechanisms of viral assembly, although the specific regions or residues involved likely differ, judging from the vast sequence diversity of M proteins.

FIG 5.

Comparison of paramyxovirus and pneumovirus M proteins. (A) Fixed orientations of M proteins from HeV (PDB entry 6BK6), NDV (PDB entry 4G1O [44]), RSV (PDB entry 4V23 [42]), and hMPV (PDB entry 4LP7 [43]). α-Helices and β-strands are colored red and yellow, respectively. The termini of each protomer are labeled in the same color scheme. (B) Sequence alignment between full-length HeV M, NDV M, RSV M, and hMPV M, with residues color coded based on the secondary-structural features.

Crystal packing of HeV M dimers by electrostatic interaction.

A number of studies have proposed how M dimers of paramyxoviruses can polymerize two dimensionally into a protein array to give rise to the virion architecture (43, 44). To investigate this in the context of HeV M, we performed a structural analysis using the PDBePISA sever (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/msd-srv/prot_int/pistart.html) to identify favorable contacts between dimers of HeV M. The analysis revealed three notable interfaces, all of which comprise an interface area of ∼350 Å2. Among the three, the most prominent interface, based on the number of specific polar interactions present, was mediated by the α1 and α2 helices of neighboring M dimers (Fig. 6A). There is an approximately 16° angle between the two abutting dimers (dimer 1 and dimer 2), and the direction of the curvature is analogous to that of the viral membrane. Structurally, the interface between dimer 1 and dimer 2 comprises two sets of identical interactions in reciprocal directions. In one set, Arg57 of the α1 helix (dimer 1, residues 53 to 57) establishes a network of salt bridge contacts with Asp105 and Glu108 of the α2 helix (dimer 2) (Fig. 6B), the latter of which forms more intimate contacts in a head-to-head orientation. Arg57 is further stabilized by Gln104 (dimer 2), whose side chain rotates away from the interface, presumably due to charge repulsion, as well as H102 (dimer 2), both via nonpolar interactions. Additionally, Phe59 from dimer 1, which is located adjacent to the primary contact site, also forms minor van der Waals interactions with Thr100 from dimer 2.

To further understand the roles of the α1 and α2 helices in henipaviruses, we aligned the M protein sequences within the genus, using the secondary structure of HeV M as an additional guide (Fig. 6C). This comparison revealed strong sequence conservation around the α1 helical region, particularly at position 57, which is invariably represented by an arginine. On the opposing interface, positions 104, 105, and 108 are largely dominated by polar or negatively charged side chains. Thus, the α1-α2 interactions observed in the HeV M structure are likely to be homologous among henipavirus M proteins, although key residues on the α2 helix are expected to contribute differently depending on the specific side chains present.

Mutations in the dimer-dimer interface impaired VLP production.

To assess and validate the biological relevance of the above-mentioned dimer-dimer interface, we generated a series of charge reversal mutants, as either single or combinatorial mutations, targeting residues that form the identified electrostatic interactions between the α1 and α2 helices, namely, Arg57, Asp105, and Glu108. It was envisaged that M mutants that failed to establish stable intermolecular electrostatic interactions would not assemble into VLPs as effectively as the wild-type protein. We first investigated the role of Arg57 via two charge reversal mutants, R57D and R57E, both of which resulted in almost complete abrogation of VLP production based on Western blotting and densitometry analyses (P < 0.001) (Fig. 7A). Similarly, the roles of Asp105 and Glu108 in the α2 helix were individually assessed via D105R and E108R mutations, respectively. While the D105R variant did not appreciably impact the level of VLP assembly, the E108R variant led to an ∼50% reduction in VLP formation compared to the wild-type counterpart (P < 0.01), although there was no morphological change associated with these mutants under EM analysis (Fig. 7C). We also generated a double mutant encompassing both D105R and E108R mutations; however, this double mutant could not be expressed comparably to the wild type and was excluded from the analysis.

To establish a direct interaction between the α1 and α2 helices, we used R57D and R57E mutants that produced minimal VLPs as starting points, and we generated double mutants, R57D D105R and R57E E108R, to partly restore intermolecular salt bridge contacts in a reciprocal orientation with respect to wild-type HeV M. The R57D D105R mutant did not increase the efficiency of VLP assembly compared to the R57D mutant, reiterating the dispensable role of Asp105 (Fig. 7B). In contrast, the R57E E108R variant produced a VLP level approximately 40% that of the wild type, which is significantly higher than that of the R57E counterpart (P < 0.05). This result suggested that the salt bridge pair Arg57 and Glu108 dictates effective VLP production in HeV, which is in agreement with the observed structural intimacy between these two polar side chains.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we produced the first structure of a henipavirus M protein using recombinant HeV M produced from an insect cell expression system. While the production and purification protocols of NiV M have been previously documented (49, 50), the strategies employed faced significant challenges with protein solubility or required purification to be conducted under denaturing conditions, both of which represent major hurdles for structural studies. We overcame these challenges by optimizing the buffer conditions, and we showed that the protein behaves as dimers both in solution and in the crystal structure. Electron microscopy analysis further revealed that HeV M existed as small particles approximately 7 nm in diameter, which is reminiscent of dimers of M previously documented in hMPV (43). With the additional alanine substitution experiment, which revealed the critical roles of M-M interactions for HeV M stability and assembly, our observations are in agreement with the notion that the functional unit of paramyxovirus M proteins is dimeric (42–44).

To assemble into a full virion, dimers of M are required to self-organize into repetitive arrays of oligomers. However, the interfaces between dimer-dimer contacts have been only partly implied in the context of NDV and hMPV M proteins (43, 44), both of which display limited sequence homology (≤20%) to HeV M. For NDV M, which is more relevant to HeV M based on sequence homology and structural similarity, the α2 and α9 helices have been proposed to mediate interdimer contacts, although the specific residues involved have not been tested experimentally. In the HeV M structure, the α8 helix, which is equivalent to the α9 helix of the NDV M protein, does not form any specific contact in the crystal packing. Instead, regions around the α1 and α2 helices form a dimer-dimer interface in HeV M, predominantly via electrostatic interactions. While the involvement of the α2 helix is not unprecedented given its proposed role in NDV M, the contribution of the α1 helix is unique to HeV M. Indeed, the α1-equivalent region of the NDV M protein is structurally flexible, as it lacks secondary-structural features (44) and exhibits limited homology across species.

We validated the biological relevance of the salt bridge network by generating HeV M mutants carrying substitutions at residues Arg57, Asp105, and Glu108, and we showed that the polar interactions between Arg57 and Glu108 were crucial for effective VLP assembly. Remarkably, a sequence alignment across henipavirus M proteins has further revealed degrees of sequence conservation on key residues within the dimer-dimer interface, especially on Arg57, which is invariably part (underlined) of the sequence motif 55NE/DRK58. This striking conservation suggests a fundamental role associated with the α1 helix across all henipavirus M proteins and coincides with our findings that the two Arg57 mutants both dramatically compromised VLP production. Conversely, Glu108 of the α2 helix is not always conserved in henipavirus M proteins, but a negatively charged side chain at this position is often accommodated. Exceptions to this could be found in Mojiang and cedar viruses, although this was not completely unexpected, given that the E108R charge reversal mutant also did not fully abrogate VLP production. Nevertheless, the unique and negatively charged Glu104 in Mojiang and cedar virus M proteins likely improves the efficiency of virus assembly by offering additional salt bridge contacts with Arg57, judging from the structural proximity of Arg57 and Gln104 in the HeV M structure.

Beyond its structural role in mediating M-M interactions, the α2 helix of HeV M also harbors one of the two putative NESs that is highly conserved among henipaviruses. Mutations on key leucine residues within the α2 NES (20), or treatment with a specific nuclear export inhibitor, leptomycin B (13), both led to nuclear accumulation of HeV M, indicating a Crm-1-dependent nuclear export machinery. Our HeV M structure reveals that key leucine side chains of the α2 NES are largely buried, as they point directly opposite to the dimer-dimer assembly interface (Fig. 8), which is in marked contrast to the solvent-exposed α8 NLS that is required for importin-dependent nuclear import (20). Nevertheless, the structural arrangement of the NES relative to the α2 helix suggests dynamic control in switching between M protein trafficking and assembly, as the two events compete for the same steric requirement for protein-protein interactions. Similar mechanisms, which involve masking of the NES via protein-protein interactions, have also been well documented in a number of host proteins associated with Crm-1-dependent transport (51–54). It is also likely that the accessibility of the NLS is subject to the same control mechanism, since the α9-eqavalent helix has also been implicated in paramyxovirus M protein assembly (44).

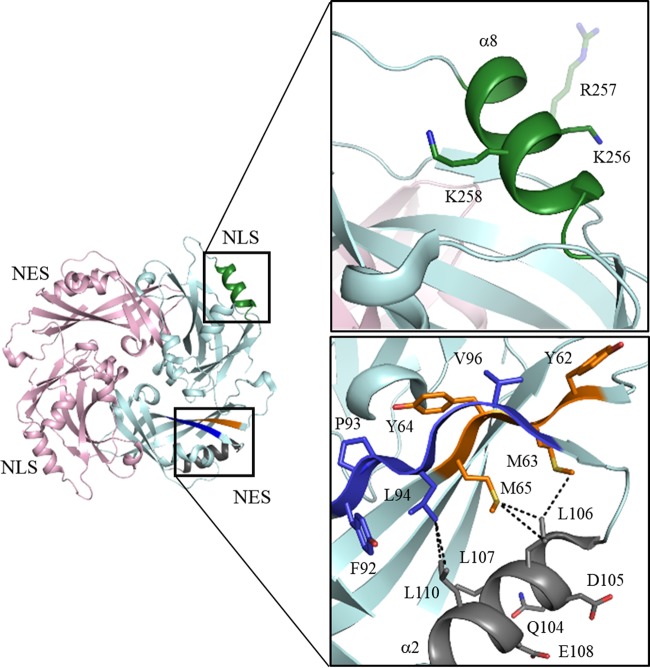

FIG 8.

Structural features of NLS and NES in HeV M. Key residues of the α8 NLS (green) are solvent exposed, with R257 being structurally flexible. The leucine-rich α2 NES (gray) forms intimate interactions with two putative L domains (blue and orange) that are part of the HeV M core structure. Van der Waals contacts are shown as black dashed lines.

Given the close sequence identity between HeV M and NiV M (∼90%), the structure of HeV M allows us to confidently investigate the location and role of the putative L domains (62YMYL65 and 92YPLGVG97) that were previously reported for NiV M (32, 33). Except for the L65M substitution, the HeV M sequence encompasses L motifs identical to those of NiV M. Structurally, the two L motifs map to part of the β-sheet core (β2 and β3) that is only moderately solvent exposed in the direction of the viral membrane, with solvent-exposed residues limited to Tyr62, Tyr64, and Val96 for potential protein-protein or protein-membrane interactions. The majority of the buried residues, including Leu94, Met65, and Met63, are involved in a network of hydrophobic contacts with the NES (mainly Leu110 and Leu116) that is located on the α2 helix (Fig. 8). Based on these structural configurations, our model suggests the two putative domains are more likely to be important for the structural integrity of M, especially in stabilizing the α2 helix that dictates both intracellular trafficking and oligomerization of M (19, 20). Major distortions of the putative L motifs, such as mutations or deletions, would inevitably impact M protein stability, as well as the integrity and accessibility of the α2 NES. These speculations are in agreement with findings made with the Δ62YMYL65 and Δ92YPLGVG97 NiV M mutants, which demonstrated a significant reduction in the protein expression level, as well as elevated nuclear accumulation, presumably due to the impaired machinery of nuclear export (32, 33).

The findings presented here provide a framework for understanding the structural assembly of Hendra virus. This mechanism may be both representative of and unique to the genus Henipavirus on the basis of close sequence homology of henipavirus M proteins. More studies of M proteins within the genus could be beneficial to delineate this mechanism further, such as investigating residues that facilitate VLP production along the other directional axis. It will also be beneficial to explore how some of these M mutants interact with other viral components, such as the F and G proteins, in coordinating virus assembly. Ultimately, these investigations may lead to the development of therapeutic strategies for controlling the deadly henipaviruses by targeting a crucial component of virion production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

HeV M constructs and mutagenesis.

The native DNA sequence of the HeV M gene (GenBank accession no. AEB21223.1) was obtained as a gift from Glenn Marsh of the Australian Animal Health Laboratory (CSIRO). The primers used to amplify the sequence required for various constructs in this study are summarized in Table 2. All molecular-cloning reagents were purchased from NEB. For protein expression, the PCR-amplified fragment was initially digested and ligated into the pET43.1a vector (Novagen) using the BamHI and NheI restriction enzymes and T4 ligase. This construct was subsequently used to clone HeV M into pFastBac1 (Invitrogen) carrying an N-terminal 6-His tag using BamHI and XhoI digestion sites derived from the pET43.1 vector. For expression in HEK293T cells, the HeV M coding region was PCR amplified and ligated into the pCAGGS vector with an N-terminal myc tag, utilizing the SacI and XhoI restriction sites. Mutagenesis was achieved by an overlapping-PCR approach with Phusion polymerase, using the wild-type pCAGGS-Myc-HeVM plasmid, the pCAGGS-Myc-HeVM-R57E plasmid, or the pCAGGS-Myc-HeVM-R57D plasmid as a template for gene amplification.

TABLE 2.

Primers utilized in this study

| Primer name or purpose | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Forward | Reverse | |

| To generate pCAGGS-Myc- HeV M | CCCCGAGCTCATGGATTTTAGTGTGAGTG | TGCTAGCTCGAGTCACCCCTTTAGGATCTTCCC |

| Mutagenesis | ||

| pCAGGS-specific primers | CTACAGCTCCTGGGCAAC | GCCAGAAGTCAGATGCTCAAGG |

| HeV M R57E | CCCCAGGTGCAAATGAGGAGAAATTCAACAAC | GTTGTTGAATTTCTCCTCATTTGCACCTGGGG |

| HeV M R57D | CCCCAGGTGCAAATGAGGACAAATTCAACAAC | GTTGTTGAATTTGTCCTCATTTGCACCTGGGG |

| HeV M E108R | CACCCTCAGGATCTTTTACGAGAGCTATGTTCTTTG | CAAAGAACATAGCTCTCGTAAAAGATCCTGAGGGTG |

| HeV M D105E/E108R | CTTCTCACCCTCAGCGTCTTTTACGAGAGCTATG | CATAGCTCTCGTAAAAGACGCTGAGGGTGAGAAG |

| HeV M R118A | CTTTGAAAGTCACTGTCGCAAGAACAGCTGGGGCTAC | GTAGCCCCAGCTGTTCTTGCGACAGTGACTTTCAAAG |

| HeV M T120A | GTCACTGTCAGAAGAGCAGCTGGGGCTACAGAG | CTCTGTAGCCCCAGCTGCTCTTCTGACAGTGAC |

| HeV M V154A | CAATATTCAATGCTGCCAAGGTTTGCCGCAATG | CATTGCGGCAAACCTTGGCAGCATTGAATATTG |

| HeV M R158A | GCTGTCAAGGTTTGCGCCAATGTGGATCAGATTC | GAATCTGATCCACATTGGCGCAAACCTTGACAGC |

| HeV M E166A | GATCAGATTCAACTGGCGAAACAACAATCATTG | CAATGATTGTTGTTTCGCCAGTTGAATCTGATC |

| To generate pET43-HeV M | CCAAGGATCCGATTTTAGTGTGAGTGATAACCTTGATGATCC | GGTTGCTAGCCCCCCTTTAGGATCTTCCCTGTGTTGTC |

Production of baculovirus stock.

Baculovirus was generated using the Bac-to-Bac expression system (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the pFastBac1 vector containing a HeV M gene fragment was transformed into Escherichia coli DH10Bac competent cells to generate bacmid DNA by site-specific transposition. Colonies bearing the recombinant bacmid were selected based on a blue/white screening method on an LB agar plate containing kanamycin (50 μg/ml), gentamicin (7 μg/ml), tetracycline (100 μg/ml), IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) (40 μg/ml), and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal) (100 μg/ml). The recombinant bacmid containing the HeV M gene was then amplified, isolated, and transfected into Sf9 (Spodoptera frugiperda) cells cultured in Sf-900 II medium (Life Technologies), using Fugene 6 (Promega). The passage 1 (P1) viral stock was collected 3 days after the transfection and was used for two additional rounds of virus amplifications in order to produce a high-titer P3 virus stock.

Expression and purification of recombinant HeV M.

The P3 viral stock was used to infect Sf9 cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 4. The infected cells were cultured for 72 h and harvested by centrifugation at 500 × g for 10 min. The cell pellet was stored at −80°C prior to downstream processing. For protein extraction, the cell pellet was thawed in the presence of buffer A, containing 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1% NP-40, and 20 mM imidazole. An EmulsiFlex-C5 cell homogenizer (Avestin) was utilized to further assist cell lysis at 15,000 lb/in2 on ice. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 30,000 × g for 30 min. Soluble lysate containing the recombinant HeV M was loaded onto a 2-ml Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) resin (Novagen) preequilibrated with buffer A. At least 200 ml of buffer B (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 50 mM imidazole) was passed through the column to remove weakly bound proteins. Elution was conducted with 10 ml of buffer C, containing 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, and 300 mM imidazole. The sample was briefly concentrated using a 10,000-Da-molecular-mass-cutoff concentrator (Merck Millipore) to <5 ml before being subjected to size exclusion chromatography using a HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200 column (GE Healthcare) preequilibrated in buffer D (20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl, 5% glycerol, 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). Fractions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and concentrated to 3 mg/ml based on absorbance at 280 nm.

Crystallization of HeV M.

All crystallization experiments were conducted with vapor diffusion techniques at 20°C. Initial crystallization screens were carried out via the robotic system at the CSIRO Collaborative Crystallisation Centre (C3), Melbourne, Australia (http://www.crystal.csiro.au), using a sitting-drop method by mixing 150 nl of protein and reservoir solutions at a 1:1 ratio. The crystals were optimized manually using the hanging-drop method with 2-μl drops of equal volumes of protein and crystallant and 200 μl of crystallant in the reservoir. Typically, plate-like crystals of HeV M appeared after 2 to 3 days at 3-mg/ml protein concentration, with a reservoir solution comprising 0.2 M Ca acetate, 0.1 M imidazole, pH 7.5, and 5 to 10% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000.

Data collection, processing, structural determination, and analysis.

All crystals were briefly soaked in cryoprotection solution comprising 0.2 M Ca acetate, 0.1 M imidazole, pH 7.5, 5% PEG 8000, and 25% glycerol before being cryocooled directly in liquid nitrogen. A complete data set was collected at the Australian Synchrotron (Clayton, Victoria, Australia) with the Eiger detector on the MX2 beamline at 100 K. Data were processed and scaled with the iMosflm program and Aimless from the CCP4 suites (55), respectively. Molecular replacement was carried out with PHASER (56) using a polyalanine model generated from the published NDV M structure (PDB ID 4G1O) minus the loop regions as a search model. Structural refinements were conducted with the Phenix program (57), and manual building of the model was performed with Coot. Refinement validation was achieved via the online validation tool from the PDB server. Superimposition of structures was carried out using the SSM superpose feature in CCP4, and all graphical representations of the structure were generated with PyMOL (The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 2.0, Schrödinger, LLC).

Virus-like-particle production.

HEK293T cells grown in 12-well plates to 50% confluence were transfected with pCAGGS plasmids encoding wild-type and mutant Myc-HeV M (0.5 μg/dish) using Fugene 6 reagent (Promega). Forty to 48 h posttransfection, culture media were collected and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 5 min to remove cell debris. The clarified supernatants containing VLPs were layered onto a 20% sucrose cushion and centrifuged for 2 h at 100,000 × g. Pellets containing VLPs were resuspended in 100 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To quantitate the total production of HeV M variants, transfected HEK293 cells were lysed in PBS plus 1% NP-40 on ice for 20 min. The detection of HeV M was analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-Myc mouse monoclonal antibody (MAb) (9B11) conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (Cell Signaling).

To prepare VLP samples for electron microscopy, HEK293 cells were transfected with Myc-tagged HeV M variants (2 μg DNA per dish) in 10-cm dishes with Fugene 6 for 48 h. VLPs were first harvested by centrifugation through a sucrose cushion as described previously, resuspended in 200 μl PBS, and layered on top of a continuous sucrose gradient (10 to 50%) prepared in NTE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA). Samples were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 16 h using an SW40 Ti swinging-bucket rotor (Beckman), and 1-ml fractions were collected from the bottom to the top. Fractions containing VLPs, as judged from immunoblotting, were pooled, buffer exchanged, and concentrated in NTE buffer using a 100-kDa-molecular-mass-cutoff concentrator.

Electron microscopy.

Carbon-coated 300-mesh copper grids were rendered hydrophilic by glow discharge in nitrogen. Five microliters of the sample was aliquoted onto each grid for 10 s, and the excess was removed using Whatman 541 filter paper. The grid was then washed two times with water for 1 min each time, stained with 2% aqueous uranyl acetate for 3 s, blotted, and air dried. All the samples were examined using a Tecnai 12 transmission electron microscope (FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) at an operating voltage of 120 kV. Images were taken using a Megaview III charge-coupled-device (CCD) camera and AnalySIS camera control software (Olympus).

Accession number(s).

The atomic coordinate and structure factors of HeV M have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession number 6BK6.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the staff at the Australian Synchrotron and Tom Peat (CSIRO) for their assistance in data collection. We also thank the fermentation team (CSIRO, Node, National Biologics Facility) for helping with large-scale insect cell expression. The EM images were taken by Jacinta White (CSIRO). All crystallisation trials were conducted by the CSIRO collaborative crystallization center (http://www.csiro.au/C3).

Y.C.L. is supported by a CSIRO OCE postdoctoral fellowship.

We declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eaton BT, Broder CC, Middleton D, Wang LF. 2006. Hendra and Nipah viruses: different and dangerous. Nat Rev Microbiol 4:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyatt AD, Zaki SR, Goldsmith CS, Wise TG, Hengstberger SG. 2001. Ultrastructure of Hendra virus and Nipah virus within cultured cells and host animals. Microbes Infect 3:297–306. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(01)01383-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldsmith CS, Whistler T, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, Rota PA, Bellini WJ, Daszak P, Wong KT, Shieh WJ, Zaki SR. 2003. Elucidation of Nipah virus morphogenesis and replication using ultrastructural and molecular approaches. Virus Res 92:89–98. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1702(02)00323-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Halpin K, Bankamp B, Harcourt BH, Bellini WJ, Rota PA. 2004. Nipah virus conforms to the rule of six in a minigenome replication assay. J Gen Virol 85:701–707. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whelan SP, Barr JN, Wertz GW. 2004. Transcription and replication of nonsegmented negative-strand RNA viruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 283:61–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrison MS, Sakaguchi T, Schmitt AP. 2010. Paramyxovirus assembly and budding: building particles that transmit infections. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 42:1416–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takimoto T, Portner A. 2004. Molecular mechanism of paramyxovirus budding. Virus Res 106:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmitt PT, Ray G, Schmitt AP. 2010. The C-terminal end of parainfluenza virus 5 NP protein is important for virus-like particle production and M-NP protein interaction. J Virol 84:12810–12823. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01885-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coronel EC, Takimoto T, Murti KG, Varich N, Portner A. 2001. Nucleocapsid incorporation into parainfluenza virus is regulated by specific interaction with matrix protein. J Virol 75:1117–1123. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1117-1123.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duan Z, Chen J, Xu H, Zhu J, Li Q, He L, Liu H, Hu S, Liu X. 2014. The nucleolar phosphoprotein B23 targets Newcastle disease virus matrix protein to the nucleoli and facilitates viral replication. Virology 452-453:212–222. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bharaj P, Wang YE, Dawes BE, Yun TE, Park A, Yen B, Basler CF, Freiberg AN, Lee B, Rajsbaum R. 2016. The matrix protein of Nipah virus targets the E3-ubiquitin ligase TRIM6 to inhibit the IKKepsilon kinase-mediated type-I IFN antiviral response. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005880. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deffrasnes C, Marsh GA, Foo CH, Rootes CL, Gould CM, Grusovin J, Monaghan P, Lo MK, Tompkins SM, Adams TE, Lowenthal JW, Simpson KJ, Stewart CR, Bean AGD, Wang LF. 2016. Genome-wide siRNA screening at biosafety level 4 reveals a crucial role for fibrillarin in henipavirus infection. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005478. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bauer A, Neumann S, Karger A, Henning AK, Maisner A, Lamp B, Dietzel E, Kwasnitschka L, Balkema-Buschmann A, Keil GM, Finke S. 2014. ANP32B is a nuclear target of henipavirus M proteins. PLoS One 9:e97233. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghildyal R, Baulch-Brown C, Mills J, Meanger J. 2003. The matrix protein of human respiratory syncytial virus localises to the nucleus of infected cells and inhibits transcription. Arch Virol 148:1419–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghildyal R, Ho A, Dias M, Soegiyono L, Bardin PG, Tran KC, Teng MN, Jans DA. 2009. The respiratory syncytial virus matrix protein possesses a Crm1-mediated nuclear export mechanism. J Virol 83:5353–5362. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02374-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coleman NA, Peeples ME. 1993. The matrix protein of Newcastle disease virus localizes to the nucleus via a bipartite nuclear localization signal. Virology 195:596–607. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peeples ME, Wang C, Gupta KC, Coleman N. 1992. Nuclear entry and nucleolar localization of the Newcastle disease virus (NDV) matrix protein occur early in infection and do not require other NDV proteins. J Virol 66:3263–3269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshida T, Nagai Y, Yoshii S, Maeno K, Matsumoto T. 1976. Membrane (M) protein of HVJ (Sendai virus): its role in virus assembly. Virology 71:143–161. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(76)90101-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang YE, Park A, Lake M, Pentecost M, Torres B, Yun TE, Wolf MC, Holbrook MR, Freiberg AN, Lee B. 2010. Ubiquitin-regulated nuclear-cytoplasmic trafficking of the Nipah virus matrix protein is important for viral budding. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001186. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pentecost M, Vashisht AA, Lester T, Voros T, Beaty SM, Park A, Wang YE, Yun TE, Freiberg AN, Wohlschlegel JA, Lee B. 2015. Evidence for ubiquitin-regulated nuclear and subnuclear trafficking among Paramyxovirinae matrix proteins. PLoS Pathog 11:e1004739. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrus JE, von Schwedler UK, Pornillos OW, Morham SG, Zavitz KH, Wang HE, Wettstein DA, Stray KM, Cote M, Rich RL, Myszka DG, Sundquist WI. 2001. Tsg101 and the vacuolar protein sorting pathway are essential for HIV-1 budding. Cell 107:55–65. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harty RN, Brown ME, Wang G, Huibregtse J, Hayes FP. 2000. A PPxY motif within the VP40 protein of Ebola virus interacts physically and functionally with a ubiquitin ligase: implications for filovirus budding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:13871–13876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250277297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kikonyogo A, Bouamr F, Vana ML, Xiang Y, Aiyar A, Carter C, Leis J. 2001. Proteins related to the Nedd4 family of ubiquitin protein ligases interact with the L domain of Rous sarcoma virus and are required for gag budding from cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:11199–11204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201268998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin-Serrano J, Yarovoy A, Perez-Caballero D, Bieniasz PD. 2003. Divergent retroviral late-budding domains recruit vacuolar protein sorting factors by using alternative adaptor proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:12414–12419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2133846100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strack B, Calistri A, Accola MA, Palu G, Gottlinger HG. 2000. A role for ubiquitin ligase recruitment in retrovirus release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97:13063–13068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.VerPlank L, Bouamr F, LaGrassa TJ, Agresta B, Kikonyogo A, Leis J, Carter CA. 2001. Tsg101, a homologue of ubiquitin-conjugating (E2) enzymes, binds the L domain in HIV type 1 Pr55(Gag). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:7724–7729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.131059198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Schwedler UK, Stuchell M, Muller B, Ward DM, Chung HY, Morita E, Wang HE, Davis T, He GP, Cimbora DM, Scott A, Krausslich HG, Kaplan J, Morham SG, Sundquist WI. 2003. The protein network of HIV budding. Cell 114:701–713. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00714-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuan B, Campbell S, Bacharach E, Rein A, Goff SP. 2000. Infectivity of Moloney murine leukemia virus defective in late assembly events is restored by late assembly domains of other retroviruses. J Virol 74:7250–7260. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.16.7250-7260.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parent LJ, Bennett RP, Craven RC, Nelle TD, Krishna NK, Bowzard JB, Wilson CB, Puffer BA, Montelaro RC, Wills JW. 1995. Positionally independent and exchangeable late budding functions of the Rous sarcoma virus and human immunodeficiency virus Gag proteins. J Virol 69:5455–5460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Votteler J, Sundquist WI. 2013. Virus budding and the ESCRT pathway. Cell Host Microbe 14:232–241. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanson PI, Cashikar A. 2012. Multivesicular body morphogenesis. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 28:337–362. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ciancanelli MJ, Basler CF. 2006. Mutation of YMYL in the Nipah virus matrix protein abrogates budding and alters subcellular localization. J Virol 80:12070–12078. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01743-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patch JR, Han Z, McCarthy SE, Yan L, Wang LF, Harty RN, Broder CC. 2008. The YPLGVG sequence of the Nipah virus matrix protein is required for budding. Virol J 5:137. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-5-137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patch JR, Crameri G, Wang LF, Eaton BT, Broder CC. 2007. Quantitative analysis of Nipah virus proteins released as virus-like particles reveals central role for the matrix protein. Virol J 4:1. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coronel EC, Murti KG, Takimoto T, Portner A. 1999. Human parainfluenza virus type 1 matrix and nucleoprotein genes transiently expressed in mammalian cells induce the release of virus-like particles containing nucleocapsid-like structures. J Virol 73:7035–7038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pantua HD, McGinnes LW, Peeples ME, Morrison TG. 2006. Requirements for the assembly and release of Newcastle disease virus-like particles. J Virol 80:11062–11073. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00726-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pohl C, Duprex WP, Krohne G, Rima BK, Schneider-Schaulies S. 2007. Measles virus M and F proteins associate with detergent-resistant membrane fractions and promote formation of virus-like particles. J Gen Virol 88:1243–1250. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82578-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmitt AP, Leser GP, Waning DL, Lamb RA. 2002. Requirements for budding of paramyxovirus simian virus 5 virus-like particles. J Virol 76:3952–3964. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.3952-3964.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Li M, Schmitt PT, Li Z, McCrory TS, He B, Schmitt AP. 2009. Mumps virus matrix, fusion, and nucleocapsid proteins cooperate for efficient production of virus-like particles. J Virol 83:7261–7272. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00421-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugahara F, Uchiyama T, Watanabe H, Shimazu Y, Kuwayama M, Fujii Y, Kiyotani K, Adachi A, Kohno N, Yoshida T, Sakaguchi T. 2004. Paramyxovirus Sendai virus-like particle formation by expression of multiple viral proteins and acceleration of its release by C protein. Virology 325:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Money VA, McPhee HK, Mosely JA, Sanderson JM, Yeo RP. 2009. Surface features of a Mononegavirales matrix protein indicate sites of membrane interaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:4441–4446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805740106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Forster A, Maertens GN, Farrell PJ, Bajorek M. 2015. Dimerization of matrix protein is required for budding of respiratory syncytial virus. J Virol 89:4624–4635. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03500-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leyrat C, Renner M, Harlos K, Huiskonen JT, Grimes JM. 2014. Structure and self-assembly of the calcium binding matrix protein of human metapneumovirus. Structure 22:136–148. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Battisti AJ, Meng G, Winkler DC, McGinnes LW, Plevka P, Steven AC, Morrison TG, Rossmann MG. 2012. Structure and assembly of a paramyxovirus matrix protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:13996–14000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210275109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dombrowsky H, Clark GT, Rau GA, Bernhard W, Postle AD. 2003. Molecular species compositions of lung and pancreas phospholipids in the cftr(tm1HGU/tm1HGU) cystic fibrosis mouse. Pediatr Res 53:447–454. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000049937.30305.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palestini P, Calvi C, Conforti E, Botto L, Fenoglio C, Miserocchi G. 2002. Composition, biophysical properties, and morphometry of plasma membranes in pulmonary interstitial edema. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 282:L1382–L1390. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00447.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cifuentes-Munoz N, Sun W, Ray G, Schmitt PT, Webb S, Gibson K, Dutch RE, Schmitt AP. 2017. Mutations in the transmembrane domain and cytoplasmic tail of Hendra virus fusion protein disrupt virus-like-particle assembly. J Virol 91:e00152-17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00152-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krissinel E, Henrick K. 2004. Secondary-structure matching (SSM), a new tool for fast protein structure alignment in three dimensions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60:2256–2268. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904026460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Subramanian SK, Tey BT, Hamid M, Tan WS. 2009. Production of the matrix protein of Nipah virus in Escherichia coli: virus-like particles and possible application for diagnosis. J Virol Methods 162:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Masoomi Dezfooli S, Tan WS, Tey BT, Ooi CW, Hussain SA. 2016. Expression and purification of the matrix protein of Nipah virus in baculovirus insect cell system. Biotechnol Prog 32:171–177. doi: 10.1002/btpr.2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jeyasekharan AD, Liu Y, Hattori H, Pisupati V, Jonsdottir AB, Rajendra E, Lee M, Sundaramoorthy E, Schlachter S, Kaminski CF, Ofir-Rosenfeld Y, Sato K, Savill J, Ayoub N, Venkitaraman AR. 2013. A cancer-associated BRCA2 mutation reveals masked nuclear export signals controlling localization. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20:1191–1198. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu J, McKeon F. 1999. NF-AT activation requires suppression of Crm1-dependent export by calcineurin. Nature 398:256–260. doi: 10.1038/18473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Craig E, Zhang ZK, Davies KP, Kalpana GV. 2002. A masked NES in INI1/hSNF5 mediates hCRM1-dependent nuclear export: implications for tumorigenesis. EMBO J 21:31–42. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stommel JM, Marchenko ND, Jimenez GS, Moll UM, Hope TJ, Wahl GM. 1999. A leucine-rich nuclear export signal in the p53 tetramerization domain: regulation of subcellular localization and p53 activity by NES masking. EMBO J 18:1660–1672. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.6.1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Winn MD, Ballard CC, Cowtan KD, Dodson EJ, Emsley P, Evans PR, Keegan RM, Krissinel EB, Leslie AG, McCoy A, McNicholas SJ, Murshudov GN, Pannu NS, Potterton EA, Powell HR, Read RJ, Vagin A, Wilson KS. 2011. Overview of the CCP4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 67:235–242. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910045749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCoy AJ. 2007. Solving structures of protein complexes by molecular replacement with Phaser. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 63:32–41. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906045975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Oeffner R, Read RJ, Richardson DC, Richardson JS, Terwilliger TC, Zwart PH. 2010. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]