Abstract

Perceived discrimination has been found to increase risk for depression in emerging adulthood, but explanatory cognitive mechanisms have not been well studied. We examined whether the brooding and reflective subtypes of rumination would mediate the relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among racial/ethnic minority, versus White, emerging adults, and whether a strong ethnic identity would buffer against this effect. Emerging adults (N = 709; 70% female; 68% racial/ethnic minority), ages 18–25, completed measures of perceived discrimination, rumination, depressive symptoms, and ethnic identity. Perceived discrimination was positively associated with depressive symptoms among racial/ethnic minority and White participants. Brooding – but not reflection – mediated this relation only among racial/ethnic minorities. Ethnic identity, though negatively associated with depressive symptoms, did not buffer against the mediating effect of brooding on the discrimination-depression relation. Interventions for depression among racial/ethnic minority emerging adults should address maladaptive cognitive responses, such as brooding, associated with perceived discrimination.

Keywords: Perceived Discrimination, Rumination, Depression, Emerging Adulthood

Epidemiological data show that racial and ethnic minorities are at highest risk for the onset of depression between ages 18 and 25 (Algería et al. 2007; Kim & Choi 2010; & Williams et al. 2007), a period known as emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000). Although racial and ethnic minorities tend to be at lower risk of experiencing depressive symptoms, in general, compared to White individuals (Riolo, Nguyen, Greden & King, 2005), the 12-month prevalence of depression is higher for racial and ethnic minorities compared to White individuals (Kessler et al., 2003). Given this risk, it is important to understand whether culturally related experiences prevalent among racial/ethnic minorities, such as perceived discrimination (Kessler, Mickelson & Williams, 1999; Landrine, Klonoff, Corral, Fernandez, & Roesch, 2006; Perez, Fortuna & Alegría, 2008), impact vulnerability to depressive symptoms in racial/ethnic minority emerging adults. Considering the compelling evidence linking perceived discrimination to negative mental health outcomes, particularly depression (Chou, Asnaani & Hofmann, 2012; Pascoe & Richman, 2009; Williams, Neighbors & Jackson, 2003), the need to understand the mechanisms behind this relation becomes more pressing.

Maladaptive cognitive responses to negative moods, such as rumination, have been found to prolong and exacerbate depressive symptoms (see Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubormisky 2008). However, such research has not typically examined racial and ethnic differences in the relation between cognitive risk factors and depressive symptoms, nor have culturally-related factors known to increase vulnerability to depression among racial and ethnic minorities typically been examined in conjunction with cognitive risk factors, with some recent exceptions in rumination (Borders & Liang, 2011; Chang, Tsai, & Sanna, 2010; Hatzenbuehler, Nolen-Hoeksema, & Dovidio, 2009) and hopelessness (Hirsch, Visser, Chang & Jeglic, 2012; Polanco-Roman & Miranda, 2013). Previous research has found that perceived discrimination is associated with ruminative thinking (Borders & Liang, 2011; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009). Nonetheless, no research of which we are aware has examined the association between perceptions of discrimination and the different subtypes of rumination – i.e., brooding and reflection – nor whether these subtypes differentially explain the relation between perceived discrimination and symptoms of depression. Along with such risk factors, recent research has revealed the importance of understanding culturally related factors, such as ethnic identity, that may be protective against the emergence of depressive symptoms (Greene, Way & Pahl, 2006; Torres & Ong, 2010, Polanco-Roman & Miranda, 2013). Despite our knowledge of cognitive and culturally related risk factors for depression, there is little information about the interplay between them. A better understanding of this relation is one avenue through which to combat depression in emerging adults from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds. The present research thus sought to address this gap in the literature by examining the interplay between culturally related and cognitive factors in explaining vulnerability to depressive symptoms among racial/ethnic minority, compared to White, emerging adults.

Rumination and Risk for Depression

Rumination is a cognitive response style employed during distress that is characterized as a repetitive focus on one’s dysphoric mood and on the “…causes and consequences…” of that dysphoric mood (Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008, p. 410). Rumination is associated with the onset and chronicity of depression over time (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000). In addition, it is associated with mental inflexibility, difficulty in finding solutions to problems, and decreased optimism about the future – factors that are also known to be associated with depression (Davis & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Lyubomirsky & Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995). Treynor and colleagues (Treynor, Gonzalez & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2003) have identified two subtypes of rumination. The first, termed brooding, involves dwelling on one’s dysphoric mood. Brooding is considered a maladaptive form of rumination, because it is associated with negative symptom outcomes, such as increases in depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation, concurrently and over time (Burwell & Shirk, 2007; Miranda & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007; O’Connor & Noyce, 2008; Treynor et al., 2003). The second form of rumination, termed reflective pondering, or reflection, involves attempts to try to understand the reasons for one’s dysphoric mood. It is considered a more adaptive form of rumination, and it is associated with decreases in depressive symptoms over time (Burwell & Shirk, 2007; Treynor et al., 2003). However, recent studies provide a mixed view of reflective rumination, given that it has also been found to be associated with higher symptoms of depression among college students low in active coping (Marroquín, Fontes, Scilletta, & Miranda, 2010), and with suicidal ideation among emerging adults with a history of a suicide attempt (Surrence, Miranda, Marroquín, & Chan, 2009). It has also been found to predict higher risk for suicidal ideation over time, independently of depression (Miranda & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007).

There is evidence to suggest racial/ethnic differences in the relation between rumination and depression. For example, Chang and colleagues (2010) found that Asian American college students were more likely to ruminate compared to European American college students, and they also reported a weaker concurrent association between rumination and depressive symptoms among Asian Americans than among European Americans. At the same time, rumination was more uniquely associated with depressive symptoms among Asian Americans than it was among European American individuals, when adjusting for other factors such as positive and negative affectivity. In comparison, Borders and Liang (2011) found that rumination partially mediated the concurrent relation between perceived discrimination and measures of psychological distress, including depressive symptoms, among racial/ethnic minority college students but not among White college students.1 That is, perceived discrimination was positively associated with depressive symptoms among racial/ethnic minority students – but not among White students – and this discrimination-depression relation was partially explained by rumination (Borders & Liang, 2011). There is also evidence of an age difference in rumination, with younger adults (e.g., 25–35 year-olds) ruminating more than older adults (Nolen-Hoeksema & Aldao, 2011). Such findings call for a deeper examination of how culturally related factors may combine with ruminative thinking to impact risk for depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood.

Perceived Discrimination and Risk for Depression

Researchers suggest that experiences of racial and ethnic discrimination are highly prevalent among racial/ethnic minorities, with younger age groups (i.e., 18–44 year-olds), reporting more perceived discrimination than older age groups (e.g., ages 45 and above) (Kessler et al, 1999; Perez et al., 2008). For example, Perez and colleagues (2008) found that about 50% of Latinos between ages 18 and 24 from a nationally representative sample reported experiencing moderate to high levels of discrimination, compared to 26% or less of individuals ages 45 and above. Harrell (2000) suggests that racial/ethnic discrimination is a manifestation of racism on an interpersonal level, and while overt displays of discrimination are harmful, ambiguous situations in which discrimination is implicit can be just as harmful. Perceived discrimination is a culturally related stressor, in that it is a source of stress that is culturally bound and involves a subjective experience of prejudiced treatment as a result of an individual’s racial/ethnic group affiliation. Hence, it is a culturally related stressor comparable to negative life events or daily hassles (Landrine & Klonoff, 1996), but it is related to depressive symptoms independently of general negative life events (Polanco-Roman & Miranda, 2013). Perceived discrimination is more strongly associated with psychiatric symptoms among racial and ethnic minorities, compared to White individuals (Landrine et al., 2006). It has been linked to symptoms of depression in African Americans (Kessler et al, 1999; Sellers & Shelton, 2003), Latinos (Torres & Ong, 2010; Hwang & Goto, 2008), and Asian Americans (Gee, Spencer, Chen, Yip & Takeuchi, 2007; Hwang & Goto, 2008). It has also been found to be associated with increases in symptoms of depression over time (Polanco-Roman & Miranda, 2013). While the evidence linking perceived discrimination to increased risk for depression expands, the availability of empirical data to explain this link remains scarce.

Recently, researchers have found a positive association between perceived discrimination and cognitive risk factors for depression. For example, it is positively associated with rumination (Borders & Liang, 2011; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009) and with hopelessness (Polanco-Roman & Miranda, 2013). In a daily diary study of African American and of lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) participants, Hatzenbuehler and colleagues (2009) found that discrimination-related stress predicted greater negative affect over the course of 10 days, and that this relation was mediated by brooding rumination (but not by emotional suppression). While these findings offer a glimpse into the interplay between culturally related stress and cognitive responses to stress, the present study will provide a closer examination by disaggregating the subtypes of rumination – brooding and reflection – as well as considering the potential role of ethnic identity.

Ethnic Identity and Risk for Depression

Just as there are culturally related stressors that increase risk for depression, other culturally relevant factors, such as ethnic identity, appear to buffer against the effects of these stressors. Ethnic identity is the aspect of a person’s self-concept that is defined by how the individual identifies with his or her own ethnic group, and it is achieved over time through exploring the meaning of belonging to such a group (Phinney & Ong, 2007). The development of a self-concept, including ethnic identity, is a defining element of adolescence (Erikson, 1968; Quintana, 2007) and continues throughout emerging adulthood (Arnett, 2000; Phinney, 2006). Phinney’s ethnic identity framework is grounded in the idea that experiences of discrimination spur the development of an ethnic identity to counteract the detrimental effects of future discriminatory experiences (Phinney, 1992). Supporting this theory, one study found that changes in perceived discrimination over time were associated with changes in ethnic identity over time among Black and Latino adolescents. However, the inverse was not observed (Pahl & Way, 2006), suggesting that ethnic identity develops, in part, in response to experiences of discrimination. Compared to adolescents, who are beginning to ascribe meaning to their ethnic group affiliation, emerging adults have had more time to explore their ethnic identity. The protective qualities of an ethnic identity may be more pronounced during this stage of life (Phinney, 2006).

A large body of research demonstrates that ethnic identity is positively correlated with self-esteem and well being, particularly among emerging adults of racial/ethnic minority background (for a meta analytic review, see Smith & Silva, 2011). Further, a higher ethnic identity is associated with lower levels of depressive symptoms in racial/ethnic minorities (Mossakowski, 2003, Polanco-Roman & Miranda, 2013; Torres & Ong, 2010). Ethnic identity has been found to buffer against the negative effects of culturally related stressors by moderating the relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms in racial/ethnic minorities (Greene et al., 2006; Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Mossakowski, 2003; Torres & Ong, 2010). However, some research also suggests that there are aspects of an ethnic identity that may exacerbate the association between discrimination and psychological distress (Noh, Beiser, Kaspar, Hou, & Rummens, 1999; see also Brondolo et al., 2009, for a review).

More recently, however, one study with emerging adults found that ethnic identity buffered against the indirect relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms through hopelessness (Polanco-Roman & Miranda, 2013). That is, at low levels of ethnic identity, perceived discrimination was associated with higher depressive symptoms over time through higher levels of hopelessness. However, there was no statistically significant indirect relation through hopelessness at average or at high levels of ethnic identity, suggesting that ethnic identity buffered against this indirect relation. This finding highlights the complex nature of an ethnic identity, and the need to better understand the underlying cognitive mechanisms linking ethnic identity and perceived discrimination. Thus, while the present evidence for a protective effect of ethnic identity is mixed, to the degree that ethnic identity may serve as a buffer, it may do so by mitigating the effects of maladaptive cognitive responses to perceived discrimination.

Perhaps a strong ethnic identity protects against the detrimental effects of perceived discrimination by promoting active problem solving and discouraging passive perseveration, particularly brooding. Crocker and Major (1989) suggested that individuals from socially stigmatized groups, including racial/ethnic minorities, may ward off the hurt of prejudice and racism by engaging in adaptive strategies such as attributing negative feedback to an external source or selectively valuing or devaluing certain qualities of their group. However, to date, there has been no empirical examination of the relation between brooding and ethnic identity.

The Present Study

The present study aimed to further elucidate the impact of culturally related experiences on risk for depression in emerging adults by examining the relation between perceived discrimination, subtypes of rumination, and depressive symptoms in emerging adults of racially/ethnically diverse backgrounds. More specifically, we examined the association between perceived discrimination and the subtypes of rumination, brooding and reflection. In addition, we examined whether these ruminative subtypes would explain the relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms. Furthermore, given previous evidence that ethnic identity may impact the discrimination-cognition-depression relation (Polanco-Roman & Miranda, 2013), we examined whether ethnic identity would moderate the mediated relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms.

Thus, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 1. A stronger positive association between perceived discrimination and brooding than between perceived discrimination and reflection.

Hypothesis 2. Brooding, but not reflection, would mediate the relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms, more strongly for racial/ethnic minority emerging adults than for White emerging adults.

Hypothesis 3. Ethnic identity would buffer against this indirect relation, such that the indirect relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms, through brooding, would be weaker at higher levels than at lower levels of ethnic identity.

Method

Participants

First- and second-year undergraduates (N = 709; 493 female) from a racially/ethnically diverse public college in the Northeastern United States took part in this study for partial credit toward a research participation requirement in an Introduction to Psychology course. Participants were selected from a larger sample of 1,011 individuals who took part in a study of social-cognitive predictors of suicidal ideation and attempts (Chan, Miranda, & Surrence, 2009), based on their age (i.e., being between ages 18–25) and whether they completed the measures of interest in the present study. The sample included 479 (68%) racial/ethnic minority participants (212 Asian, 139 Hispanic, 78 Black, and 50 of other races/ethnicities) and 230 (32%) White participants.

Measures

Demographic Information

Information about age, sex, and race/ethnicity was collected from each participant.

Schedule of Racist Events (SRE; Landrine & Klonoff, 1996)

The SRE is an 18-item self-report questionnaire used to measure the perceived frequency and stress associated with perceptions of discrimination, as experienced in the previous year or in the respondent’s lifetime. The present study focused on perceived discrimination, as experienced in the previous year. The SRE was developed for use with African-American respondents. Thus, for the present study, language specific to African-Americans was modified to apply to all races/ethnicities (e.g., “How many times have you been treated unfairly by teachers and professors because of your race/ethnicity?”). Individuals rate the frequency of events on a scale from 1 (“Never”) to 6 (“Almost all of the time”) and rate how stressful each event was on a scale from 1 (“Not at all stressful”) to 6 (“Extremely stressful”). Given that the correlation between perceived frequency of and stress associated with discrimination was .81, suggesting they were measuring the same construct, we used the perceived stress measure in the analyses. A total score for stress was calculated by summing relevant ratings across 17 items, and scores can range from 17 to 102. A modified version of this scale has been used reliably with Asian, Black, Latino, and White individuals (see Landrine, Klonoff, Corral, Fernandez, & Roesch, 2006). Internal consistency reliability in the present sample was .87 for White participants and .90 for racial/ethnic minority participants.

Multi-Group Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Phinney, 1992)

The MEIM is a 15-item self-report questionnaire about ethnic group identification. Participants are asked to list the ethnic group with which they most strongly identify, and using a Likert scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree), indicate how strongly they agree with each item. The measure is comprised of two subscales: belonging and affirmation, consisting of 5 items (e.g., “I feel a strong attachment towards my ethnic group”), and exploration and commitment, consisting of 7 items (e.g., “I think a lot about how my life will be affected by my ethnic group”). The remaining 3 items inquire about the ethnic group of the participant, and that of their mother and father. These items were excluded from the total ethnic identity score, which equals the sum of the items from both subscales. The scale has demonstrated good reliability (Phinney, 1992), and construct validity for use with ethnically diverse youth (Roberts et al, 1999). In the present sample, the internal consistency reliability was .87 for White participants and .85 for racial/ethnic minority participants.

Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS; Nolen-Hoeksema, Larson, & Grayson, 1999)

The RRS is a 22-item self-report questionnaire assessing rumination. Five of the items assess the brooding subtype of rumination (e.g., Think “What am I doing to deserve this?”), and 5 items assess the reflection subtype of rumination (e.g., “Analyze recent events to try to understand why you are depressed”) (see Treynor et al., 2003). Individuals are asked to indicate the frequency with which they generally have each of the thoughts when they feel “…down, sad, or depressed” on a scale from 1 (almost never) to 4 (almost always). Treynor and colleagues (2003) suggested removing the other 12 items of the scale that overlapped with symptoms of depression and found that this modified scale was positively associated with concurrent symptoms of depression. However, while the brooding subscale was associated with increases in depressive symptoms over time, the reflection subscale was associated with decreases in depressive symptoms over time. Other factor analyses conducted with the RRS have suggested a similar division into two subscales (see Fresco, Frankel, Mennin, Turk, & Heimberg, 2002). In the present sample, internal consistency reliability for the brooding subscale of the RRS was .78 among racial/ethnic minority participants and .80 among White participants. Internal consistency for the reflection subscale was .72 among racial/ethnic minority participants and .69 among White participants.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Spitzer, Kroenke & Williams, 1999)

The PHQ-9 is a 9-item self-report questionnaire that assesses symptoms of Major Depression, consistent with criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), as experienced in the previous 2 weeks. Each question is rated on a 0–3 scale, ranging from “not at all” to “nearly every day.” Total depression score was computed by summing items 1–9. The PHQ-9 has been shown to have high test-retest reliability (r = .84) and criterion validity with clinician diagnosis of Major Depression (Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001). Internal consistency reliability in the present sample was .80 among racial/ethnic minority participants and .79 among White participants.

Procedure

After providing written informed consent, participants completed a packet of self-report questionnaires in a research laboratory in groups of 2–8 individuals. Questionnaires were administered by post-baccalaureate or Masters-level research assistants. Measures included the SRE, MEIM, RRS, and PHQ-9. After completing the questionnaires, participants were debriefed about the study. Individuals who endorsed 4 or more symptoms on the PHQ-9 for “more than half the days” were provided with information about the college counseling center and were encouraged to make an appointment. These measures and procedure were approved by a full Institutional Review Board.

Results

There were no statistically significant differences between racial/ethnic minority and White participants on measures of rumination (neither brooding, t(706) = 0.51, p = .61, nor reflection, t(703) = 1.28, p = .20) and depressive symptoms, t(704) = 1.01, p = .31. Racial/ethnic minority participants reported higher levels of self-appraised perceived discrimination stress (SRE), compared to White participants, t(643.1) = 7.94, p < .01. However, they also scored higher on the MEIM (ethnic identity), t(388.7) = 4.60, p < .01, compared to White individuals. Means and standard deviations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and summary of means and standard deviations.

| Racial/Ethnic Minority (N = 479) |

White (N = 230) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | N (%) | Female | 338 | (70.6%) | 155 | (67.4%) |

| Male | 141 | (29.4%) | 75 | (32.6%) | ||

| M (SD) | ||||||

| Age | 18.8 | (1.3) | 19.0 | (1.5) | ||

| Perceived Discrimination** | 31.4 | (14.9) | 24.0 | (9.4) | ||

| Ethnic Identity** | 36.2 | (6.0) | 33.7 | (7.2) | ||

| Brooding Rumination | 10.9 | (3.5) | 10.7 | (3.5) | ||

| Reflection Rumination | 9.7 | (3.2) | 9.4 | (3.0) | ||

| Depressive Symptoms | 6.7 | (4.4) | 6.3 | (4.1) | ||

Note.

p < .05;

p < .01

Perceived Discrimination, Rumination, and Depressive Symptoms

We hypothesized that perceived discrimination would be more strongly associated with the brooding subtype than with the reflective subtype of rumination. We also hypothesized that brooding, but not reflection, would mediate the relation between perceived discrimination and symptoms of depression. We expected that this indirect relation would be stronger among racial/ethnic minorities than among White individuals. The relation between perceived discrimination and the subtypes of rumination was tested via 2 sets of multiple linear regression analyses. In the first set of analyses, perceived discrimination was entered as a predictor of brooding, simultaneously adjusting for reflection and ethnic identity. In the second set of analyses, perceived discrimination was entered as a predictor of reflection, simultaneously adjusting for brooding and ethnic identity. These analyses were conducted separately for racial/ethnic minority and for White individuals. Results of these analyses are shown in Tables 2a and 2b. Perceived discrimination was significantly associated with brooding among racial/ethnic minority (b = 0.07, β = 0.29, p < .01) but not among White individuals (b = 0.02, β = 0.07, p = .28). However, perceived discrimination was not associated with reflection, neither among racial/ethnic minority nor among White individuals.

Table 2.

| a. Linear Regression Examining Relation between Perceived Discrimination and Brooding | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Predictor | b | S.E. | β | Partial r | b | S.E. | β | Partial r |

| Racial/Ethnic Minority | White | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Perceived Discrimination | 0.07** | 0.01 | 0.29** | .32** | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | .07 |

| Reflection | 0.44** | 0.04 | 0.40** | .42** | 0.53** | 0.07 | 0.45** | .45** |

| Ethnic Identity | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.03 | −.04 | −0.001 | 0.03 | −0.003 | −0.003 |

| b. Linear Regression Examining Relation between Perceived Discrimination and Reflection | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Predictor | b | S.E. | β | Partial r | b | S.E. | β | Partial r |

| Racial/Ethnic Minority | White | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Perceived Discrimination | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.06 | .06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.10 | .11 |

| Brooding | 0.40** | 0.04 | 0.44** | .42** | 0.39** | 0.05 | 0.45** | .45** |

| Ethnic Identity | 0.05* | 0.02 | 0.09 | .10* | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.07 | −.08 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01

b = Unstandardized regression coefficient.

β = Standardized regression coefficient

We also examined whether perceived discrimination, brooding, and reflection would be associated with depressive symptoms when entered simultaneously into a linear regression that also adjusted for ethnic identity. Analyses were conducted separately for racial/ethnic minority and for White individuals. Results are displayed in Table 3. Both brooding and reflection were significantly associated with depressive symptoms among racial/ethnic minority participants (bbrood = 0.42, βbrood = 0.34, p < .01; breflect = 0.26, βreflect = 0.19, p < .01), when adjusting for perceived discrimination and ethnic identity. Among White individuals, only brooding, but not reflection, was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (bbrood = 0.51, βbrood = 0.43, p < .01; breflect = 0.14, βreflect = 0.10, p = .12), when adjusting for perceived discrimination and ethnic identity. Perceived discrimination was significantly associated with depressive symptoms among racial/ethnic minorities (b = 0.06, β = 0.22, p < .01) but not among White individuals (b = 0.04, β = 0.09, p = .12), when adjusting for the ruminative subtypes and ethnic identity.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Linear Regression for Depressive Symptoms

| Predictor | b | S.E. | β | Partial r | b | S.E. | β | Partial r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racial/Ethnic Minority | White | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Perceived Discrimination | 0.06** | 0.01 | 0.22** | .24** | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.09 | .11 |

| Ethnic Identity | −0.07 | 0.03 | −0.10 | −.12 | −0.04 | 0.03 | −0.07 | −.08 |

| Brooding | 0.42** | 0.06 | 0.34** | .33 | 0.51** | 0.08 | 0.43** | .40** |

| Reflection | 0.26** | 0.06 | 0.19** | .20** | 0.14 | 0.09 | 0.10 | .11 |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01

b = Unstandardized regression coefficient.

β = Standardized regression coefficient

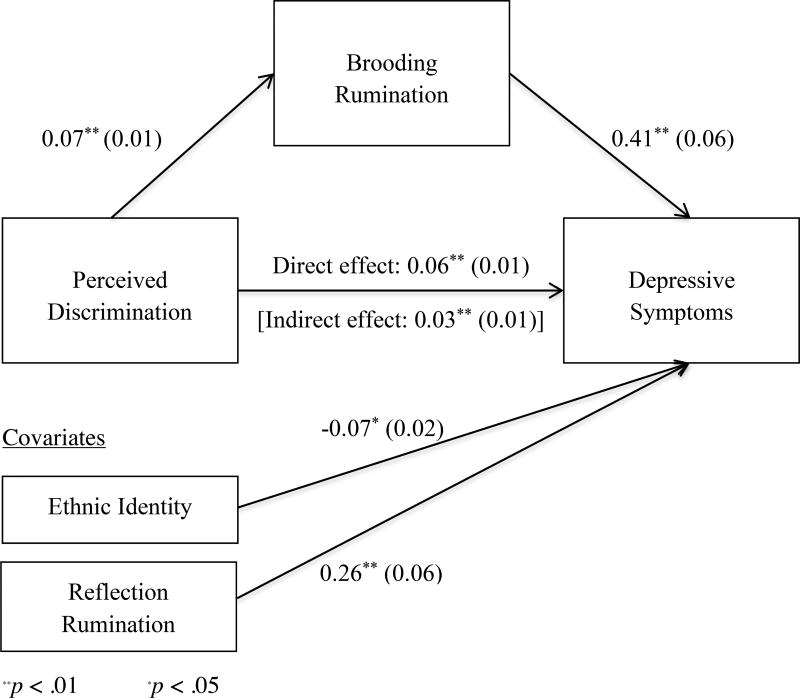

Brooding as a Mediator

MacKinnon and colleagues suggest that tests for mediation may be conducted when a predictor (e.g., perceived discrimination) is significantly related to a proposed mediator (e.g., brooding, reflection) and the proposed mediator to an outcome (e.g., depressive symptoms) (MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman, West, & Sheets, 2002). Given the absence of a statistically significant relation between perceived discrimination and reflection among racial/ethnic minorities and among White individuals, and the absence of a significant relation between perceived discrimination and brooding among White individuals, we focused our analyses on brooding as a potential mediator. Specifically, we examined whether brooding would mediate the relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among racial/ethnic minority individuals, adjusting for ethnic identity and reflection (see Figure 1). Mediation analyses were conducted using the PROCESS computational tool for SPSS (Hayes, 2013; see also Preacher, Rucker, & Hayes, 2007). The data were resampled with replacement 5,000 times using bootstrapping to test the indirect effect of perceived discrimination on depressive symptoms through brooding. The indirect effect was considered statistically significant if its 95% confidence interval did not contain zero. We found that brooding mediated the relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among racial/ethnic minority participants, 95% CI = 0.02–0.04.

Figure 1.

Brooding as a mediator of the relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among racial/ethnic minorities, adjusting for ethnic identity and reflection. Unstandardized regression coefficients are shown, with standard deviations in parentheses.

Buffering Effect of Ethnic Identity

We also examined whether ethnic identity would moderate the mediating effect of brooding on the relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms, adjusting for reflection. This analysis was conducted using a bootstrapping procedure with 5000 resamples, via the PROCESS computational tool for SPSS (Hayes, 2013). We examined the indirect effect of brooding on the relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among racial/ethnic minority individuals at low (1 SD below the mean), average, and high (1 SD above the mean) levels of ethnic identity. We found a statistically significant indirect effect of perceived discrimination on depressive symptoms – through brooding – at low, 95% CI = 0.02–0.05, average, 95% CI = 0.02–0.04, and high levels of ethnic identity, 95% CI = 0.01–0.04. Thus, ethnic identity did not moderate the indirect relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms – through brooding – among racial and ethnic minority individuals.

Discussion

This study sought to elucidate the potential cognitive mechanisms behind the relation between perceived discrimination and depression by investigating racial/ethnic differences in the relation between perceived discrimination, rumination, and depressive symptoms. This is the first study of which we are aware to examine the explanatory role of brooding and reflection, the subtypes of rumination, in the relation between perceived racial/ethnic discrimination and depressive symptoms, along with the moderating role of ethnic identity, among White and racial/ethnic minority emerging adults. Brooding, but not reflection, mediated the concurrent relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms, but only among racial/ethnic minorities and not among White individuals. These findings are consistent with previous research suggesting that rumination mediates the relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among racial/ethnic minorities (Borders & Liang, 2011; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2009), and extend this research by disaggregating the effects of the subtypes of rumination on the perceived discrimination-depression relation. Furthermore, we found that this explanatory relation remained at different levels of ethnic identity, suggesting that ethnic identity did not buffer against the impact of brooding on the relation between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms. Considering the mounting evidence (though mixed) suggesting that ethnic identity protects against depression and buffers against the detrimental effects of perceived discrimination among racial/ethnic minority individuals (Greene et al., 2006; Mossakowski, 2003; Sellers & Shelton, 2003; Torres & Ong, 2010; Polanco-Roman & Miranda, 2013), this finding was unexpected. At the same time, the present study differed from previous findings of a buffering effect of ethnic identity in that it was cross-sectional, while previous studies were either longitudinal (e.g., Greene et al., 2006; Polanco-Roman & Miranda, 2010), involved repeated measures (i.e., daily diary; Torres & Ong, 2010), or examined a specific racial/ethnic minority group (e.g., Filipino-Americans; Mossakowski, 2003; or African-Americans; Sellers & Shelton, 2003), rather than examining different racial/ethnic minority groups as one large group. It is possible that the buffering effect of an ethnic identity may vary by racial/ethnic group and/or may be observed over time, rather than concurrently.

These findings also support previous research suggesting that brooding is a more maladaptive form of rumination than is reflection, which is more benign or adaptive (Burwell & Shirk, 2007; Treynor et al., 2003). Consistent with previous research (Treynor et al., 2003), brooding was found to be positively associated with concurrently assessed depressive symptoms, both among racial/ethnic minority and among White participants. Reflection was also significantly and positively associated with depressive symptoms, but only among racial/ethnic minority participants and not among White participants (in analyses that also adjusted for perceived discrimination and ethnic identity). It should be noted that the present study did not include a follow up, as did some previous studies (Burwell & Shirk, 2007; Treynor et al., 2003), to determine whether brooding would be associated with increased depressive symptoms over time and whether reflection would result in decreases in depressive symptoms over time among both White and racial/ethnic minority individuals. Interestingly, perceived discrimination was not concurrently associated with reflection, suggesting that reflection does not co-occur with perceptions of discrimination, despite its concurrent relation with depressive symptoms among racial/ethnic minorities.

On the other hand, perceived discrimination was positively associated with brooding among racial/ethnic minorities, but not among White individuals. While the absence of longitudinal data prevents an inference of causality, one possible explanation for this finding is that perceived discrimination, because of its greater relevance to racial and ethnic minorities, may increase brooding only among racial/ethnic minority emerging adults but not among White emerging adults. That is, racial and ethnic minority emerging adults may respond to perceived discrimination with brooding, rather than with the more benign reflective rumination, and such a tendency to brood may be associated with higher vulnerability to depressive symptoms. These results are consistent with those of Hatzenbuehler and colleagues (2009), who found that brooding rumination, but not emotional suppression, mediated the relation between daily experiences of discrimination and psychological distress.2 Thus, experiences of racial/ethnic discrimination in conjunction with maladaptive cognitive responses such as rumination may increase risk for depressive symptoms among racial/ethnic minority emerging adults, but ethnic identity may not have enough of an impact to mitigate this detrimental effect.

Strengths and Limitations

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, this was a college-student, primarily female, non-clinical sample, and findings may not generalize to community samples of emerging adults that include a greater proportion of males, nor to clinical samples of females with major depression. At the same time, given that women tend to report higher levels of rumination and of depressive symptoms, compared to men (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 1999; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2001), inclusion of a primarily female sample is appropriate to studying the relation between ruminative thinking and depressive symptoms. However, future research should examine these questions in community and clinical samples.

Although a strength of the present study is that the city and school from which students were recruited was racially/ethnically diverse, the present sample is not representative of more homogenous, albeit traditional, college settings in which White students are represented at a higher proportion than racial/ethnic minorities. At the same time, recent data indicate that the population of racial/ethnic minority college students continues to increase (Fry, 2010).

Third, while the present sample enabled comparison of racial/ethnic minority to White participants, the numbers of Asian, Hispanic, and Black participants were not sufficiently large to allow examination of between-group differences in the mediational relations. Previous research has found that the association between perceived discrimination and depression varies across different racial/ethnic groups. For instance, Latino individuals who reported perceived discrimination were more likely to meet criteria for depression compared to Asian and African American individuals (Chou, Asnaani & Hofmann, 2012; Hwang & Goto, 2008). Therefore, the interplay between cultural experiences and cognitive responses may be distinct within each racial/ethnic minority group. Furthermore, within-group differences have been documented in Latino (Alegría et al., 2007), Asian (Takeuchi et al., 2007) and Black (Williams et al., 2007) individuals, with highly acculturated individuals displaying more risk for psychiatric symptoms than less acculturated individuals. Finally, the present study did not take into account relevant sociodemographic factors, such as immigration status, income, and religion, which may have accounted for variability in depressive symptoms. These variables should be included in future research.

Future Directions

Future research should also examine neurophysiological and behavioral measures in combination with cognitive and culturally related factors. For instance, researchers have found increased levels of cortisol in response to race-related stressors (Richman & Jonassaint, 2008). Additionally, recent research suggests that neural activity during experiences of racial discrimination resembles brain activity while experiencing physical pain, while perceiving an event as racial discrimination is associated with lower distress (Masten, Telzer & Eisenberger, 2011), suggesting that while discriminatory experiences elicit negative physiological responses, cognitive appraisals may be employed to cope with these experiences. These findings highlight the need to integrate multiple perspectives in psychological research to better explain the mechanisms behind the impact of racial discrimination on risk for depression.

Finally, this study has implications for clinical interventions with emerging adults from diverse backgrounds. Our findings suggest a link between perceived discrimination and depression that may be explained by brooding rumination – but only among racial/ethnic minorities, versus White individuals. Thus, clinicians working with racial and ethnic minority emerging adults at risk for depression should not only inquire about their experiences of racial discrimination but also about their cognitive responses to those experiences. Clinicians may then focus on interventions that target brooding rumination and that promote more adaptive forms of cognitive coping with experiences of discrimination.

Conclusion

In sum, the present research suggests that perceived discrimination is associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms among both racial/ethnic minority and White emerging adults. Furthermore, brooding – but not reflection – statistically mediates this relation, and this mediated relation is present regardless of the strength of the individual’s ethnic identity. Interventions to alleviate depressive symptoms among racial and ethnic minorities should not only assess for experiences of discrimination but should also focus on the degree to which those perceived or actual experiences result in a tendency to dwell on negative emotions.

Acknowledgments

This paper was funded by a grant from the APA Office of Ethnic Minority Affairs and by NIH Grant GM060665. Thanks to Valerie Khait, Monique Fontes, Shirley Chan, Michelle Gallagher, Shama Goklani, Judelysse Gomez, Brett Marroquín, and Kai Monde for their assistance with data collection.

Footnotes

Note that Borders and Liang (2011) examined anger rumination, or rumination that occurs in response to experiencing anger.

Note that Hatzenbuehler and colleagues (2009) found this for both African-American individuals and LGB individuals, suggesting that responding to other forms of discrimination (e.g., related to sexual orientation) that are relevant to particular populations may also increase vulnerability to depressive symptoms.

Contributor Information

Regina Miranda, Department of Psychology, Hunter College and The Graduate Center, City University of New York.

Lillian Polanco-Roman, Department of Psychology, The Graduate Center, City University of New York.

Aliona Tsypes, Department of Psychology, Hunter College, City University of New York.

Jorge Valderrama, Department of Psychology, The Graduate Center, City University of New York.

References

- Alegría M, Mulvaney-Day N, Torres M, Polo A, Cao Z, Canino G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders across Latino subgroups in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:68–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borders A, Liang CTH. Rumination partially mediates the associations between perceived ethnic discrimination, emotional distress, and aggression. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2011;17:125–133. doi: 10.1037/a0023357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondolo E, ver Halen N, Pencille M, Beatty D, Contrada RJ. Coping with racism: A selective review of the literature and a theoretical and methodological critique. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:64–88. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9193-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burwell RA, Shirk SR. Subtypes of rumination in adolescence: Associations between brooding, reflection, depressive symptoms, and coping. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:56–65. doi: 10.1080/15374410709336568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S, Miranda R, Surrence K. Subtypes of rumination in the relationship between negative life events and suicidal ideation. Archives of Suicide Research. 2009;13:123–135. doi: 10.1080/13811110902835015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EC, Tsai W, Sanna LJ. Examining the relations between rumination and adjustment: Do ethnic differences exist between Asian and European Americans? Asian American Journal of Psychology. 2010;1:46–56. [Google Scholar]

- Chou T, Asnaani A, Hofmann SG. Perception of racial discrimination and psychopathology across three U.S. ethnic minority groups. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2012;18:74–81. doi: 10.1037/a0025432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B. Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties of stigma. Psychological Review. 1989;96:608–630. [Google Scholar]

- Davis RN, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Cognitive inflexibility among ruminators and non-ruminators. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24:699–711. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: Norton; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Fresco DM, Frankel AN, Mennin DS, Turk CL, Heimberg RG. Distinct and overlapping features of rumination and worry: The relationship of cognitive production to negative affective states. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2002;26:179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Fry R. Minorities and the recession-era college enrollment boom. Pew Research Center; 2010. [June 16, 2010]. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/06/16/minorities-and-the-recession-era-college-enrollment-boom/ [Google Scholar]

- Gee GC, Spencer M, Chen J, Yip T, Takeuchi DT. The association between self-reported racial discrimination and 12-month DSM-IV mental disorders among Asian Americans nationwide. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;64:1984–1996. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, Pahl K. Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:218–238. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrell SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. An introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Nolen-Hoeksema S, Dovidio J. How does stigma “get under the skin”?: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Psychological Science. 2009;20:1282–1289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch JK, Visser PL, Chang EC, Jeglic EL. Race and ethnic differences in hope and hopelessness as moderators of the association between depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation. Journal of American College Health. 2012;60:115–125. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2011.567402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang W, Goto S. The impact of perceived racial discrimination on the mental health of Asian American and Latino college students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2008;14:326–335. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.4.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:208–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Koretz D, Merikangas KR, Wang PS. The epidemiology of Major Depressive Disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Journal of the American Medical Association. 2003;289:3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Choi NG. Twelve-month prevalence of DSM-IV mental disorders among older Asian Americans: Comparison with younger groups. Aging & Mental Health. 2010;14:90–99. doi: 10.1080/13607860903046461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA. The schedule of racist events: A measure of racial discrimination and a study of its negative physical and mental health consequences. Journal of Black Psychology. 1996;22:144–168. [Google Scholar]

- Landrine H, Klonoff EA, Corral I, Fernandez S, Roesch S. Conceptualizing and measuring ethnic discrimination in health research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29:79–94. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9029-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of self-focused rumination on negative thinking and interpersonal problem-solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:176–190. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marroquín BM, Fontes M, Scilletta A, Miranda R. Ruminative subtypes and coping responses: Active and passive pathways to depressive symptoms. Cognition and Emotion. 2010;24:1446–1455. [Google Scholar]

- Masten CL, Telzer EH, Eisenberger NI. An fMRI investigation of attributing negative social treatment to racial discrimination. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2011;23:1042–1051. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2010.21520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Brooding and reflection: Rumination predicts suicidal ideation at 1-year follow-up in a community sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:3088–3095. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossakowski KN. Coping with perceived discrimination: Does ethnic identity protect mental health? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44:318–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, Beiser M, Kaspar V, Hou F, Rummens J. Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: A study of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1999;40:193–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Gender differences in depression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2001;10:173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:504–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Aldao A. Gender and age differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Personality And Individual Differences. 2011;51:704–708. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Larson J, Grayson C. Explaining the gender difference in depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77:1061–1072. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.5.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RC, Noyce R. Personality and cognitive processes: Self-criticism and different types of rumination as predictors of suicidal ideation. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:392–401. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, Way N. Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity among urban Black and Latino adolescents. Child Development. 2006;77:1403–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, Richman LS. Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, Alegría M. Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36:421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7:156–176. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Ethnic identity exploration in emerging adulthood. In: Arnett JJ, Tanner JL, editors. Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 2006. pp. 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Ong AD. Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54:271–281. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Rucker DD, Hayes AF. Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2007;42:185–227. doi: 10.1080/00273170701341316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polanco-Roman L, Miranda R. Culturally-related stress, hopelessness and vulnerability to depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation in emerging adulthood. Behavior Therapy. 2013;44:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM. Racial and ethnic identity: Developmental perspectives and research. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54:259–270. [Google Scholar]

- Richman LS, Jonassaint C. The effects of race-related stress on cortisol reactivity in the laboratory: Implications of the Duke lacrosse scandal. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;35:105–110. doi: 10.1007/s12160-007-9013-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riolo SA, Nguyen TA, Greden JF, King CA. Prevalence of depression by race/ethnicity: Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:998–1000. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.047225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, Romero A. The structure of ethnic identity in young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:301–322. [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Shelton JN. The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1079–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TB, Silva L. Ethnic identity and personal well-being of people of color: A meta analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58:42–60. doi: 10.1037/a0021528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surrence K, Miranda R, Marroquín BM, Chan S. Brooding and reflective rumination among suicide attempters: Cognitive vulnerability to suicidal ideation. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:803–808. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ Primary Care Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi DT, Zane N, Hong S, Chae DH, Gong F, Gee GC, Alegría M. Immigration-related factors and mental disorders among Asian Americans. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:84–90. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.088401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres L, Ong AD. A daily diary investigation of Latino ethnic identity, discrimination, and depression. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:561–568. doi: 10.1037/a0020652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, González HM, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson JM, Sweetman J, Jackson JS. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: Findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93:200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]