Abstract

Despite its wide use, not every high-throughput screen (HTS) yields chemical matter suitable for drug development campaigns, and seldom are ‘go/no-go’ decisions in drug discovery described in detail. This case report describes the follow-up of a 4-aroyl-1,5-disubstituted-3-hydroxy-2H-pyrrol-2-one active from a cell-free HTS to identify small-molecule inhibitors of Rtt109-catalyzed histone acetylation. While this compound and structural analogs inhibited Rtt109-catalyzed histone acetylation in vitro, further work on this series was halted after several risk mitigation strategies were performed. Compounds with this chemotype had a poor structure–activity relationship, exhibited poor selectivity among other histone acetyltransferases, and tested positive in a β-lactamase counter-screen for chemical aggregates. Furthermore, ALARM NMR demonstrated compounds with this chemotype grossly perturbed the conformation of the La protein. In retrospect, this chemotype was flagged as a ‘frequent hitter’ in an analysis of a large corporate screening deck, yet similar compounds have been published as screening actives or chemical probes versus unrelated biological targets. This report—including the decision-making process behind the ‘no-go’ decision—should be informative for groups engaged in post-HTS triage and highlight the importance of considering physicochemical properties in early drug discovery.

Keywords: Chemical aggregation, Drug discovery, High-throughput screening, Pan-assay interference compounds, PAINS, Structure-activity relationships

High-throughput screening (HTS) has become an indispensible part of both academic and industrial early drug discovery. Identifying useful chemical matter for drug development campaigns is the goal for most real and virtual HTS. However, not every discovery campaign is a ‘success’ by this metric. Sometimes HTS fails to identify any confirmed actives, which can be the result of assay design, the chemical library employed, and/or the druggability of the target. Other points where discovery campaigns can fail to progress include the post-HTS triage and the hit-to-lead phases. There are many reasons why projects fail to progress past these critical stages: inability to confirm primary assay activity by orthogonal assays, poor lead-like properties, target non-selectivity, or synthetic inaccessibility, to name a few.1 However, despite their potential utility, rarely are the details of the decision-making process behind ‘go/no-go’ decisions described in the scientific literature.2–4

Rtt109 is a fungal histone acetyltransferase (HAT) that catalyzes the acetylation of histone H3 lysine 56 (H3K56ac).5 Rtt109 and H3K56ac are crucial for replication-coupled nucleosome assembly in yeast, and fungi with defects in Rtt109 functioning or H3K56 acetylation show defects in cell growth and proliferation, genomic stability, and resistance to genotoxins.6 Rtt109 forms a stable complex with the histone chaperone Vps75. In vivo, the histone chaperone Asf1 is essential for H3K56ac, and the Asf1–H3–H4 complex is considered the physiological substrate for the Rtt109–Vps75 complex.6 Importantly, there is no known mammalian Rtt109 homolog, which has led to the hypothesis that selective, potent inhibitors of Rtt109-catalyzed histone acetylation can function as minimally-toxic antifungal agents.7–10

Our group reported the results of a cell-free fluorometric HTS to identify small-molecule inhibitors of Rtt109-catalyzed histone acetylation.11 This assay utilized the thiol-scavenging probe N-[4-(7-diethylamino-4-methylcoumarin-3-yl)phenyl]maleimide (CPM) to quantify the amount of free coenzyme A (CoA) byproduct produced by the Rtt109 HAT reaction. The primary assay screened 225 K compounds, and 1.5 K primary actives were initially identified. The post-HTS triage utilized substructure filters to remove pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS), a series of compounds with substructures that are associated with promiscuous bioactivity and assay interference, often due to non-specific thiol reactivity.12–15 These compounds are generally considered nonviable lead compounds. The post-HTS triage also included several counter-screens to remove assay interference compounds. The screening cascade identified only three non-PAINS compounds with confirmed activity suitable for more detailed follow-up studies. Many of the compounds initially discarded were thiol-reactive, and compounds with several prominent chemotypes were shown to form covalent adducts with biological thiols including CoA, glutathione (GSH), and protein cysteines.16

In this case report, we describe the follow-up for one of the three compounds surviving our initial triage, compound 1a. Work on this compound was eventually halted, though only after considerable time and resources were spent investigating it as a potential lead compound. Despite its promising initial in vitro potency and confirmed activity in two orthogonal assays, compound 1a and close analogs failed to show selectivity towards Rtt109 or any meaningful structure–activity relationship (SAR). Several lines of experimental evidence including ALARM NMR suggest the promiscuity of compound 1a is due to its tendency to form chemical aggregates and engage in non-specific compound–protein interactions. Importantly, we describe the rationale for its eventual dismissal as well as the accompanying experimental processes that ultimately drove this decision. We discuss strategies that, in retrospect, could have led to a quicker ‘no-go’ decision. It is hoped this case report can enhance the process of making ‘go/no-go’ decisions, highlight the scholarly importance of investigating the causes behind assay promiscuity, and guide better data- and medicinal chemistry-driven decisions earlier in the discovery process before consuming increasingly precious resources.

As described above, our group screened approximately 225 K small-molecules for inhibitors of Rtt109-catalyzed histone acetylation.11 During an extensive triage, the approximately 1.5 K actives from the primary HTS were triaged by cheminformatics and several counter-screens to yield only three active compounds before the commencement of more in-depth studies such as the ones described in this report. One of these three remaining compounds, named 1a, and its associated 4-aroyl-1,5-disubstituted-3-hydroxy-2H-pyrrol-2-one chemotype 1 (‘chemical structural motif’) are the subjects of this case report. In the primary HTS, it had a single-point percent inhibition of 47% at 10 μM final compound concentration. Notably, this production run of the HTS did not include detergent in the assay buffer. Several descriptors were calculated for compound 1a, indicating it did not possess many ‘lead-like’ properties (Table 1).17,18 However, the paucity of active compounds from the HTS (that were not PAINS) led us to follow-up on this compound, despite its lack of desirable lead-like traits including calculated physicochemical properties. Notably, compound 1a was not flagged as a PAINS in our cheminformatics filters.13 It showed promising activity at low micromolar concentrations in vitro in early dose–response confirmation experiments (Fig. 1A). These follow-up experiments were performed with a standard amount of non-ionic detergent (0.01% Triton X-100), as including detergents is now a standard strategy to mitigate micelle formation in HTS. These data demonstrated that the assay readout for compound 1a in the HTS format was dose-dependent, and that the primary HTS result was not the result of a random error.19–21

Table 1.

Selected descriptors for compound 1a

| Descriptor | Value | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular weight | 491.5 | Pass95 |

| c logP | 5.4 | Fail95 |

| H-bond donors | 1 | Pass95 |

| H-bond acceptors | 6 | Pass95 |

| Rotatable bonds | 6 | Pass96 |

| Stereocenters | 1 | — |

| tPSA | 172 | High|Fail96 |

| Aromatic rings | 4 | — |

| Fsp3 | 0.13 | Calculated in Pipeline Pilot 8.5 |

| PAINS | No | Calculated in Canvas 2.0 |

| REOS | Yes | Canvas 2.0 (−NO2)89 |

| Tier | 7 | Least favorable92 |

Figure 1.

Inhibitory activity of a 4-aroyl-1,5-disubstituted-3-hydroxy-2H-pyrrol-2-one screening compound against Rtt109-catalyzed histone acetylation in vitro. (A) Dose–response curves for compound 1a in library cherry-pick (mean for two replicates) and commercial resupply compound samples (mean ± SD for three replicates). Shown is the chemical structure of compound 1a. (B) HAT inhibition of compound 1a in the orthogonal slot blot assay using the commercial resupply sample.

The activity of compound 1a was quickly re-confirmed with a commercially obtained sample that was re-purified in-house by HPLC prior to re-testing (Fig. 1A). To note, the original library sample of compound 1a was of commercial origin with an unspecified synthetic route. Our in-house purification was performed to mitigate the risk of bioactive compound impurities.22,23 We did not attempt enantiomeric separation on the samples for compound 1a or its analogs, as this project was in the early stage and the chemotype 1 would likely under facile epimerization in solution. As additional quality-control, we confirmed the structural identity and purity of the commercial sample to avoid follow-up on a sample with bioactive impurities or an incorrectly assigned chemical structure (Figs. S1–S5).24–26 We note the structure of compound 1a allows for tautomerization. Ab initio calculations (B3LYP/6-31G⁄⁄; gas-phase) predict compound 1a exists primarily in the tautomeric form depicted throughout this text. However, calculations (SM6/B3LYP/6-31G⁄⁄//B3LYP/6-31G⁄⁄) that also take into account solvation do not rule out some fraction of the molecules existing as other tautomers in solution (Table S1).

Importantly, the inhibitory activity of compound 1a was reconfirmed in an orthogonal slot blot assay, a Western blot that utilizes antibodies to specific histone modifications to directly quantify the acetylated histone products (H3K56ac) in reaction aliquots, rather than the CoA by-product of the HAT reaction (Fig. 1B). These data confirmed that compound 1a was capable of inhibiting Rtt109-catalyzed histone acetylation in vitro in both the primary CPM-based HTS assay (using samples from two independent sources) and an orthogonal antibody-based assay for the commercial re-supply sample.

Although they are relatively straightforward and inexpensive, we and others have demonstrated CPM-based thiol-scavenging HTS assays are prone to a variety of compound-mediated interference mechanisms.9,11,16,27 This includes fluorescence interference, either by fluorescent compounds that can give false-negative readouts, or fluorescence quenchers, which can lead to false-positive readouts.28 Another source of assay interference are reactive compounds that form adducts with the assay reagents. One example is nucleophilic compounds, which can form adducts with the electrophilic CPM to form fluorescent adducts, leading to either false-positive or false-negative readouts depending on the fluorescent properties of the adducts. Another concerning interference mechanism is through electrophilic compounds, which can (1) trap thiol by-products of the enzymatic reaction, leading to a false-positive readout, or (2) react with protein residues, which most often leads to off-target effects and bioassay promiscuity.

As part of the Rtt109 post-HTS triage, we tested compound 1a in a series of counter-screens for the aforementioned interference types. In the context of the CPM-based readout, compound 1a did not form fluorescent adducts with any of the assay reagents (CPM, acetyl-CoA, CoA) nor was it fluorescent in the assay buffer by itself (data not shown). One concern with fluorescence-based assays is fluorescence interference.28–33 Indeed, compound 1a was able to quench the fluorescence readout fluorescence quenching counter-screen, albeit at relatively high compound concentrations (Fig. 2B). Consistent with a quenching mechanism, absorption spectra of compound 1a in assay buffer showed the compound absorbed light in the UV and violet regions (Fig. 2B). Fluorescence emission sweeps of compound 1a in assay buffer did not show appreciable fluorescence when the compound was excited at 405 nm (data not shown). These data show that compound 1a is capable of absorbing the assay excitation wavelength, but not capable of significantly fluorescing in the same wavelength as the fluorescent CPM-CoA adduct when excited at 405 nm. Lastly, we tested compound 1a for evidence of thiol-trapping in another counter-screen and found it showed a nearly identical interference pattern as the quenching counter-screen (Fig. 2C). Given that both the thiol-trapping and quenching counter-screen share the same readouts, one can deduce that the decrease in readout in the thiol-trapping counter-screen is due to fluorescence interference and not CoA-trapping. To summarize to this point, the slot blot data demonstrate compound 1a can inhibit Rtt109-catalyzed histone acetylation in vitro, whereas the CPM assay readout for compound 1a reflects a mixture of true inhibition and assay interference. With this admittedly less-than-ideal profile—and given the scarcity of compounds identified in our HTS that could inhibit Rtt109-catalyzed histone acetylation in vitro—we still chose to cautiously continue more experiments with compound 1a.

Figure 2.

CPM-based assay interference counter-screens for compound 1a. (A) Compound 1a weakly interferes with the HTS assay in a fluorescence quenching counter-screen. BHQ-1 and fluconazole are positive and negative quenching controls, respectively. (B) Absorption profile for compound 1a in assay buffer. (C) Compound 1a does not interfere with the HTS assay readout via CoA-trapping (n.b. compare to panel 2A). PC (positive control; 4-((9H-purin-6-yl)thio)-7-bromo-5-nitrobenzo[c][1,2,5]thiadiazole) and fluconazole are positive and negative thioltrapping controls, respectively.16 Data are mean ± SD for three replicates.

Compound stability is another important consideration throughout the drug discovery process.34 Previously, we and others reported classes of compounds that were not stable to assay conditions.16,35 One class, p-hydroxyarylsulfonamides, decomposed to form a reactive intermediate (likely a quinone) capable of forming covalent adducts with biological thiols including protein cysteines residues.16 Therefore, we assessed the stability of compound 1a. Unremarkably, samples of compound 1a incubated in our HTS-like conditions did not show gross evidence of instability in the assay buffer when analyzed over time by UPLC-MS (Fig. S6). These data demonstrated compound 1a was grossly stable to the assay conditions and that its inhibitory activity in vitro was not due to a degradation product detectable by UPLC-MS.

To reconcile the observed activity in the CPM-based HTS assay and the orthogonal slot blot assay with the assay interference, compound 1a was also tested in a second orthogonal assay. This method utilizes the radiolabeled substrate [3H]-acetyl-CoA and quantifies the amount of [3H]-acetate incorporated into histone substrates. Importantly, this readout is not subject to the interference in the CPM-based method and has an improved signal:noise ratio. However, its throughput is much lower, it is more costly, and it requires additional safety precautions and disposal procedures.36 Compound 1a demonstrated reproducible, low micromolar activity (IC50 = 6 ± 2 μM; Table 2). During the commercial re-supply of compound 1a, we also purchased several close structural analogs that were also commercially available in an attempt to establish preliminary evidence of SAR (‘SAR-by-commerce’). One of the favorable attributes of this series was the number of analogs commercially available. For example, 612 structural analogs with at least 80% 2-D similarity were available from a popular vendor at one point (eMolecules, accessed 2 December 2014). Furthermore, this chemical scaffold appeared amenable to chemical analog expansion by straightforward synthetic routes.37–42 To this end, we obtained commercial analogs 1b–1u and 2a–2l for further testing versus Rtt109–Vps75. In our experience, one major drawback to SAR-by-commerce (compared to performing in-house synthesis) is that the choice of analogs is limited by commercial availability. The plan at the time was to generate more preliminary data with readily available commercial compounds, which if the data showed promise, could then be used to justify a more resource-intensive medicinal chemistry effort.

Table 2.

SAR-by-commerce: inhibitory activity of compound 1a and structural analogs (chemotype 1) using an in vitro [3H]-acetyl-CoA HAT assay

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | R1 | R2 | R3 | Rtt109–Vps75 IC50 (μM) | p300 IC50 (μM) | Gcn5–Ada2–Ada3 IC50 (μM) |

| 1a |

|

|

|

6±2a | 9±5b | 7±2b |

| 1b |

|

|

|

8.5 (6-12) | 14 (5-40) | 22 (10-47) |

| 1c |

|

|

|

7.5 (6.6-8.6) | 12 (6-19) | 12 (9-16) |

| 1d |

|

|

|

9.1 (5.4-15) | 16 (10-26) | 10 (7-15) |

| 1e |

|

|

|

9.5 (4.7-19) | 12 (7-20) | 14 (7-27) |

| 1f |

|

|

|

22 (16-29) | 25 (16-41) | 4.2 (2-10) |

| 1g |

|

|

|

34 (25-45) | 29 (20-40) | 7(3-15) |

| 1h |

|

|

|

29 (4-100) | 14 (3-80) | 21 (10-42) |

| 1i |

|

|

|

18(13-24) | – | – |

| 1j |

|

|

|

20 (12-33) | – | – |

| 1k |

|

|

|

11 (8.9-15) | – | – |

| 1l |

|

|

|

5.0 (4.7-5.4) | – | – |

| 1m |

|

|

|

4.2 (3.0-5.9) | – | – |

| 1n |

|

|

|

43 (19-94) | – | – |

| 1o |

|

|

|

4.6 (2.3-9.1) | – | – |

| 1p |

|

|

|

4.0 (2.4-8.5) | – | – |

| 1q |

|

|

|

Inactive | – | – |

| 1r |

|

|

|

Inactive | – | – |

| 1s |

|

|

|

Inactive | – | – |

| 1t |

|

|

|

Inactive | – | – |

| 1u |

|

|

|

Inactive | – | – |

| 1v |

|

|

|

Inactive | – | – |

| 1w |

|

|

|

Inactive | – | – |

| 1x |

|

|

|

Inactive | – | – |

| iy |

|

|

|

Inactive | – | – |

| 1z |

|

|

|

80 (54-120) | – | – |

Except for the data for compound 1a, the data are IC50 values with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses. Compounds 1v–1z were obtained from the AZ corporate library.

IC50 values shown are means ± SD of six independent experiments.

IC50 values shown are means ± SD of three independent experiments.

The structural analogs 1b–1p all showed low micromolar IC50 values in the same radiolabeled orthogonal HAT assay (Table 2). Notably, compounds with an N-alkyl substituent such as 1s–1u were inactive (Table 2). We additionally tested a small number of compounds from the AZ corporate library, compounds 1v–1z. Of this subset, only compound 1z showed any activity versus Rtt109–Vps75. The other AZ compounds, which had an N-alkyl substituent (1v–1y), were inactive versus Rtt109–Vps75. We also tested the most structurally-similar 4-aroyl-1,5-disubstituted-3-amino-2H-pyrrol-2-ones (chemotype 2, compounds 2a–2l) that were commercially available. All of these analogs failed to inhibit Rtt109-catalyzed histone acetylation at less than 125 μM final compound concentrations (Table 3). These latter data suggested that the 3-hydroxy component was an important structural component for inhibiting Rtt109 activity in vitro. While we were confident that 1a and its close analogs with chemotype 1 could inhibit Rtt109–Vps75 HAT activity, the lack of an interpretable SAR at several structural positions raised our suspicions about non-specific inhibition.12,43

Table 3.

Inactive structural analogs of compound 1a

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ID | R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | Rtt109–Vps75 IC50 (μM) | p300 IC50 (μM) | Gcn5–Ada2–Ada3 IC50 (μM) |

| 2a | −Ph | −Ph |

|

|

Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| 2b |

|

−Ph | −Ph |

|

Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| 2c | −Ph | −Ph | −Ph |

|

Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| 2d | −Ph |

|

−Ph | −NHPh | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| 2e | −Ph | −Ph |

|

|

Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| 2f |

|

−Ph | −Ph |

|

Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| 2g | −Ph |

|

−Ph | −NHPh | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| 2h | −Ph | −Ph |

|

|

Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| 2i | −Ph | −Ph |

|

−NHPh | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| 2j | −H | −Ph | −Ph |

|

Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| 2k | −Ph |

|

−Ph | −NHPh | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| 2l | −Ph | −Ph |

|

|

Inactive | – | – |

Compounds 2 were purchased from commercial vendors and then tested for inhibition of Rtt109–Vps75 activity using the [3H]-acetyl-CoA-based HAT assay. Compounds 2a–2k were purified by standard RP-HPLC procedures and were also tested for inhibition of p300 and Gcn5–Ada2–Ada3 activity in vitro using same HAT assay. All the compounds were ‘Inactive’ (IC50 values >125 μM) versus these HATs. All purified compounds had acceptable purities (>95% by ELS and UV 254 nm) and parent ions consistent with the vendor-supplied structures (LRMS–ESI) when analyzed by UPLC–MS.

With its activity observed in one primary and two orthogonal assays, compound 1a was subsequently assessed for redox-activity, a widely reported source of promiscuous bioactivity.44–46 Using a horseradish peroxidase-phenol red (HRP-PR) surrogate assay for H2O2 production47, compound 1a was found to be only slightly redox-active at relatively high compound concentrations (i.e., 160 μM), independent of DTT in the HAT assay buffer (Fig. S7). Compounds 1l (+DTT only), 2c, 2d, and 2j showed similar low-level redox-activity at high compound concentrations (data not shown). All the other structural analogs of compound 1a were inactive in this assay both in the presence and absence of DTT (data not shown).

Generally consistent with these results at low micromolar compound concentrations, 8/8 (100%) of compound 1a structural analogs were inactive for H2O2 production in a previously reported HTS for redox-active compounds (Table S2).44 In this screen, compounds were tested at 10 μM final concentrations. Along with our observations that Rtt109–Vps75, p300 and Gcn5–Ada2–Ada3 are not overly sensitive to H2O2 in our standard in vitro assay conditions48 and that the production of H2O2 by compound 1a was only observed at concentrations an order of magnitude greater than its anti-HAT IC50 values, the results of this counter-screen demonstrate that compound 1a is highly unlikely to inhibit HAT activity in vitro by the production of H2O2.

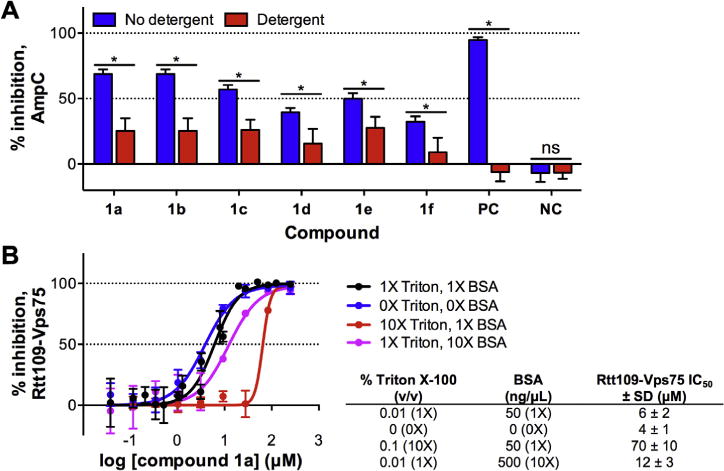

In parallel, we also assessed compound 1a and chemical analogs for promiscuous enzymatic inhibition via chemical aggregation using another surrogate enzymatic assay based on the β-lactamase AmpC, a structurally unrelated enzyme whose activity is sensitive to compound aggregates.49 Compound 1a inhibited AmpC activity in the absence of detergent at low micromolar compound concentrations (10 μM), but this inhibition could be attenuated by the inclusion of detergent (0.01% Triton X-100) in the buffer (Fig. 3A). We also tested several structural analogs that were active versus Rtt109–Vps75, compounds 1b–1f, all of which showed inhibition patterns consistent with chemical aggregate formation (Fig. 3A). We also tested several analogs that were inactive against Rtt109–Vps75, compounds 1q–1t and 2a–2l, and found that all of them did not significantly inhibit AmpC regardless of detergent status (data not shown). These data suggest that the 3-hydroxy group is an important component of AmpC inhibition, and that substitution with a 3-amino group likely prevents AmpC inhibition in the absence of detergent. These data also show alkyl substitutions at the N1 position of chemotype 1 (i.e., compounds 1s and 1t) appear to prevent AmpC inhibition in the absence of detergent.

Figure 3.

Assessment of compound 1a and related analogs for chemical aggregation. (A) β-Lactamase counter-screen for chemical aggregators. Compounds were tested for inhibition of the β-lactamase AmpC ± non-ionic detergent (0.01% Triton X-100) in Tris buffer pH 8.0. Rottlerin and lidocaine were included as positive control (PC) and negative control (NC) compounds, respectively. Data are mean ± SD for three replicates. (B) Inhibition of compound 1a against Rtt109–Vps75 as a function of Triton X-100 and BSA concentration using the [3H]-acetyl-CoA-based HAT assay in the presence of 5 mM DTT. Data are mean ± SD for three replicates. Data shown for compound 1a under standard conditions (1 detergent and BSA) is taken from Table 2.

We note, however, that 24/24 (100%) of compound 1a analogs were not flagged as potential chemical aggregators in an independent HTS using AmpC (Table S3). This observed difference between the two similar assays may result from the differences in assay buffers (Tris–HCl, pH 8.0 versus sodium phosphate, pH 7.0)50 or perhaps more subtle inter-assay differences such as the timing of the assay steps and/or the nature of intra-well solution mixing, both of which can be crucial parameters in this assay.

Since compound 1a was flagged by the aggregation counter-screen, we reasoned structural analogs might also act as chemical aggregators that could contribute to enzymatic inhibition in our assay systems, even though we had included detergent in our post-HTS assays to mitigate this possibility. We therefore investigated the effect of detergent on compound 1a using the [3H]-acetyl-CoA-based HAT assay, given the multiple sources of interference associated with the CPM-based assay. The omission of standard amounts of detergent (0.01% Triton X-100) and BSA (50 ng/μL) led to only a 2-fold more potent inhibition for compound 1a versus Rtt109–Vps75, while higher concentrations of BSA (which may also mitigate the impact of chemical aggregators in biochemical assays51) with standard amounts of Triton X-100 also did not lead to large differences in the IC50 values for compound 1a (Fig. 3B). Surprisingly, the inclusion of 10-fold higher concentrations of Triton X-100 led to an approximate 10-fold less potent inhibition of Rtt109–Vps75 activity by compound 1a (Fig. 3B).

Analysis of dose–response curves is another important consideration in HTS triage and can provide clues about the molecular mechanism(s) of target engagement such as cooperativity.52,53 A promising sign was that compound 1a and all its analogs showed complete dose–responses (i.e., 0–100% inhibition for inhibitors) with two horizontal asymptotes in both the HTS assay and the orthogonal radiolabeled HAT assay. Steeper Hill slopes have also been associated with anomalous binding behavior such as aggregation.53–55 Consistent with this phenomenon, compound 1a had steeper Hill slopes in follow-up assays versus three different HATs (Table 4). In addition, examination of the slot blot results demonstrated a sharp cut-off in activity, consistent with a steeper Hill slope (Fig. 1B).

Table 4.

Hill slopes of compound 1a using an in vitro [3H]-acetyl-CoA HAT assay

| ID | Hill slope, Rtt109–Vps75 | Hill slope, p300 | Hill slope, Gcn5–Ada2–Ada3 |

|

| |||

| 1a | 2.0±0.6a | 1.5±0.3b | 1.8±0.4b |

The calculations are based on the data from Table 2 for compound 1a.

IC50 values shown are means ± SD of six independent experiments.

IC50 values shown are means ± SD of three independent experiments.

While IC50 values are by themselves an imperfect measure of selectivity56, one of our initial project criteria for progression to a ‘hit-to-lead’ (H2L) phase was a compound with at least 5-fold selectivity by IC50 value (but preferably greater) for Rtt109 versus other HATs. In parallel with the aggregation and redox-activity screens, we tested compounds 1a–1h versus two other HATs using the [3H]-acetyl-CoA-based HAT assay. We performed a selectivity counter-screen versus (1) p300, the human HAT that catalyzes H3K56ac and shares only gross tertiary structure with yeast Rtt109, and (2) Gcn5–Ada2–Ada3, a yeast HAT that is implicated in yeast RCNA and acetylates N-terminal H3 residues like H3K27 and H3K9.57,58 Compound 1a inhibited both p300 and Gcn5–Ada2–Ada3 at low micromolar concentrations with no apparent selectivity towards Rtt109 (Table 2). Likewise, analogs 1b–1h showed similar IC50 values and failed to show any convincing selectivity towards Rtt109–Vps75, demonstrating this compound series inhibited HATs non-selectively (Table 2).

Given the lack of any observed selectivity in the HAT counter-screen, we examined whether the observed anti-HAT activity for chemotype 1 was isolated to HATs, or represented even broader target promiscuity as the AmpC counter-screen suggested. Therefore, we tested the ability of compound 1a and its chemical analogs 1b–1f to modulate the conformation of the human La antigen, a protein completely unrelated from Rtt109. This assay, ALARM NMR, has been useful for identifying thiol-reactive compounds, as it contains several cysteines that when covalently modified, induce characteristic peak shifts and line broadening in nearby residues.59,60 Importantly, this method also utilizes an orthogonal detection method (2D 1H–13C HMQC) for assaying target engagement.

As expected for a ‘frequent hitter’ and not a simple, non-specific HAT inhibitor, compound 1a perturbed the La protein conformation as evidenced by the signal decreases relative to DMSO controls, while the inactive analog compound 2i did not perturb the La protein conformation when tested (Fig. 4). The inclusion of DTT in the assay buffer did not attenuate the line broadening for compound 1a, which is consistent with a non thiol-reactive mechanism of action in this experimental setting.59,60 Similar results were observed for compounds 1b–1f (data not shown). This non-specific interaction is consistent with the lack of any apparent in vitro selectivity for chemotype 1 against a panel of HATs. Another possibility is H2O2 production by compound 1a and analogs,59 but this explanation is less likely in our setting given the low levels of redox-activity observed only at relatively high compound concentrations in our HRP-PR counter-screen (see Fig. S7).

Figure 4.

Effect of the 4-aroyl-1,5-disubstituted-3-hydroxy-2H-pyrrol-2-one active (compound 1a) on La protein conformation using ALARM NMR. Shown are 2D 1H–13C HMQC spectra of selected 13C-labelled methyl groups for compound 1a as tested by ALARM NMR. Compounds were incubated with the La protein in either the presence (blue) or absence (red) of 20 mM DTT. 2-Chloro-1,4-naphthoquinone (PC) and fluconazole are shown as positive and negative compound controls, respectively. A scaled-up view of compound 1a is shown (‘1a zoom’). Note the spectra with and without DTT are nearly identical. Compound 2i, an inactive analog, was also included as a negative control compound. Signals were normalized to DMSO controls. Shown are representative results from one of three independent experiments.

We have previously shown certain compound classes can interfere with assay readouts by multiple chemical mechanisms.16 One of the main mechanisms causing non-specific bioactivity is electrophilic reaction of compounds with cysteines on proteins.59–61 Other biologically important thiols include CoA and glutathione (GSH), the latter of which can be used as a surrogate assay for thiol-reactivity.62,63 Since compound 1a was ALARM NMR positive with and without DTT in the reaction mixture, thiol-reactivity could not be clearly established. Therefore, we next sought to determine whether compound 1a was thiol-reactive by alternate assays. We first incubated compound 1a with either CoA or GSH in assay buffer and analyzed reaction aliquots by UPLC-MS. However, we were unable to observe any compound-thiol adducts (data not shown). Using the radiolabeled HAT assay versus Rtt109, we also assessed whether the addition of DTT in the assay buffer could attenuate the inhibitory activity of compound 1a against Rtt109. There was no significant difference between the IC50 values for compound 1a in either the presence or absence of DTT and BSA (p = 0.61, n = 3; Fig. S8). By contrast, the positive control CPM probe showed a significant decrease in IC50 when DTT and BSA were omitted from the reaction mixture. These results suggest that compound 1a is not a thiol-reactive chemotype in our assay conditions. However, we note a related compound has shown evidence of time-dependent and irreversible inhibition using kinetic studies, although isolation of a covalent adduct was not performed.64 These data leave open the possibility this series may be reactive under certain conditions.

Certain compounds can react non-enzymatically with protein lysine side chains.65 As such, we explored this possibility for compound 1a. However, we did not observe any detectable aminecompound 1a adducts by UPLC-MS when compound 1a was incubated with either Nα-acetyl-L-lysine methyl ester or N-butylamine. Furthermore, the addition of excess N-butylamine did not attenuate the perturbation of the La protein conformation by compound 1a when tested by ALARM NMR (data not shown).

We also performed additional experiments to characterize the basic mechanism of Rtt109–Vps75 inhibition by compound 1a using the [3H]-acetyl-CoA HAT assay. One hallmark of reactive compounds (and also slow, tight binders) is time-dependent inhibition. Therefore, we assessed whether the enzymatic inhibition was time-dependent by varying the amount of time compound 1a was allowed to pre-incubate with Rtt109–Vps75 prior to initiating the HAT reaction.56 We found no significant difference in the IC50 values of compound 1a between 5, 15 and 30 min pre-incubation time (Fig. 5A). This result demonstrates Rtt109–Vps75 inhibition by compound 1a is not enhanced by prolonged pre-incubation times.

Figure 5.

Additional mechanistic experiments for compound 1a. (A) Dependence of incubation time on activity of compound 1a against Rtt109–Vps75 activity. Compound 1a was allowed to pre-incubate with Rtt109–Vps75 for 5, 15 or 30 min prior to initiating the HAT reaction with [3H]-acetyl-CoA. Data are mean ± SD for three replicates. (B) Dilution-based experiment to examine reversibility of Rtt109–Vps75 inhibition by compound 1a. Data are mean ± SD for nine replicates.

Another important distinction is whether a compound exerts its mechanism of action by reversible or irreversible means. Making this distinction is important for interpreting experiments and performing structure-based drug design. Compounds that covalently react with their target generally show irreversible target modification, whereas compounds not covalently reacting with their target show reversible modification. Therefore, we also examined for evidence of reversible/irreversible inhibition of Rtt109–Vps75 in vitro HAT activity by compound 1a. We performed a modified jump dilution experiment.56,66,67 We observed that Rtt109–Vps75 activity was restored upon dilution, which is consistent with a reversible type of enzymatic inhibition (Fig. 5B). These data suggest compound 1a, and most likely its other structural analogs, inhibit Rtt109–Vps75 activity in vitro by a non-specific, reversible process. This is consistent with our other data, including the positive AmpC counter-screen, the non-specific compound–protein interactions observed by ALARM NMR, and the lack of observed thiol reactivity in multiple assays.

In a recent report, we advocated for examinations of bioactive compounds in the context of previous studies.1 As such, we examined the scientific literature for reports of bioactivity for compound 1a and close structural analogs. The number of publications and patents invoking screening ‘hits’ similar to compound 1a has grown exponentially in the past decade (Fig. 6). We found that related compounds have been published as active versus targets and/or systems unrelated to our screening target, Rtt109. These include both real and virtual screens, with several of the reported targets being protein-protein interactions.37–40,42,64,68–84

Figure 6.

Publication trend of compound 1a substructure. Shown is the annual number of publications in which compounds containing a compound 1a substructure were reported as being used in ‘biological studies’. The data was obtained from SciFinder using default substructure searching methods. A and B refer to the first reported synthesis and subsequent bioactivity measurements for this substructure, respectively.93,94 Data accessed 29 December 2014.

We also examined repositories of HTS data for indication of bioassay and target promiscuity for compound 1a and structural analogs. There were no reports of compound 1a in any PubChem bioassay. However, analysis of PubChem records showed several analogs of compound 1a were active in a variety of bioassays (Fig. 7).85–87 Furthermore, we also utilized an open-source tool for predicting bioactivity promiscuity, BadApple (Bioactivity data associative promiscuity pattern learning engine). We found that compound 1a and several related substructures were predicted to be highly promiscuous (Table 5).

Figure 7.

Selected examples of bioactive 4-aroyl-1,5-disubstituted-3-hydroxy-2H-pyrrol-2-ones in PubChem. The compounds shown are structurally similar to compound 1a and are active in multiple PubChem bioassays versus a variety of protein targets. There is no PubChem bioactivity data reported for compound 1a. Data accessed 2 December 2014.

Table 5.

BadApple bioactivity promiscuity analysis of compound 1a, 4-aroyl-1,5-disubstituted-3-hydroxy-2H-pyrrol-2-ones and related substructures

| Structural query | Remarks | pScore | BadApple advisory |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Parent compound | 1463 | High |

|

– | 689 | High |

|

– | 944 | High |

|

– | 506 | High |

|

– | 678 | High |

|

– | 176 | Moderate |

A, any atom. pScore: 0–100, low advisory for promiscuity; 101–300, moderate advisory; >300, high advisory. Accessed 1 June 2014 (http://pasilla.health.unm.edu/tomcat/badapple/badapple).

Finally, we examined the HTS records from AZ for evidence of assay promiscuity in an industrial setting.88 These records include over 1 M compounds tested in up to hundreds of HTS campaigns, with wide ranges of assay types. Mining of this screening deck demonstrated that the compound class of 4-aroyl-1,5-disubstituted-3-hydroxy-2H-pyrrol-2-ones showed an increased incidence of promiscuous bioactivity profiles, indicating their frequent-hitting behavior is not exclusive to academic screening campaigns or screening libraries (Table 6). Looking more closely at the substitution patterns of compounds in the corporate data set and their alignment with frequent-hitter behavior in historical assay data, we found that aromatic substitution at all three positions poses the highest risk of such behavior. These data suggest that aliphatic substitutions at any of the three positions lessen the risk of anomalous behavior, as does substitution of the hydroxyl. These observations align closely with our Rtt109 structure–activity data (Fig. 8), suggesting that the empirical observations for the smaller set of compounds in this paper apply to the larger class as well.

Table 6.

3-Hydroxy-pyrrolidin-2-ones bioassay promiscuity analysis in an industrial HTS setting

| Query ID | Substructure querya | Description | Nb | Ndatab | Ab (pBSF >2) | P(a ⩾ A|p = 0.06)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A |

|

Unsubstituted hydroxyl and monosubstituted at R2 position | 537 | 483 | 22 | 0.93 |

| B |

|

Compounds substituted at hydroxyl position; no or disubstitution at R2 position (no monosubstituted examples found) | 28 | 27 | 0 | 1.00 |

| C |

|

Aliphatic non-ring linker at position R1 | 413 | 371 | 1 | 1.00 |

| D |

|

Aromatic group at position R1 | 104 | 93 | 21 | <0.001 |

| E |

|

Aromatic groups at position R1,R2,R3 | 85 | 75 | 20 | <0.001 |

| F |

|

Aromatic groups at position R1,R3; aliphatic at position R2 Note - both compounds are disubstituted at R2 (no mono-substituted examples found) | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1.00 |

| G |

|

Aromatic groups at position R1,R2; aliphatic at position R3 | 19 | 18 | 1 | 0.67 |

Structure–property-relationships-by-data suggest that aromatic substitutions at all three positions R1, R2 and R3 lead to an increased incidence of anomalous behavior. Data patterns suggest that aliphatic substitution at any of the three positions, or substitution of the hydroxyl alleviates this behavior.

Structure annotations: sn, number of nonhydrogen substituents (e.g., “s2”); rn, number of connected ring bonds (e.g., “r2”); u, aromatic bonds.

N is the number of compounds having the substructure, and Ndata designates the subset of compounds for which a pBSF score had been derived. This is dependent on the availability of HTS screening data. A is the count of compounds with a pBSF score ⩾2.

Cumulative binomial probability of seeing A or more compounds with a pBSF score in a set of Ndata compounds when the expected incidence is 0.06. A very low chance (bolded) suggests that the observed count is unexpected, that is, the set of compounds shows an unexpectedly high incidence of anomalous binders. Expected incidence of anomalous binders is 6% (averaged over all compounds with data in the AZ collection).

Figure 8.

Summary of in vitro structure–activity/structure–interference relationships for chemotype 1. Shown is compound 1a, the parent compound originally identified in a cell-free fluorometric HTS for inhibitors of Rtt109-catalyzed histone acetylation.

It remains unclear what properties modulate the indiscriminate binding behavior. Properties of the class, in particular of the polyaromatic examples, are predominantly non-lead-like, with most compounds in this report exhibiting high lipophilicity. Modification of the structure with aliphatic groups or O-substitution will modulate properties including fluorescence, lipophilicity, and acidity of the hydroxyl group, but no clear relationship could be found between promiscuous behavior and predicted pKa, lipophilicity (logP, logD), or polar surface area (Nissink, unpublished observations).

This case report describes the follow-up of a 4-aroyl-1,5-disubstituted-3-hydroxy-2H-pyrrol-2-one active, compound 1a, from a cell-free HTS to identity small-molecule inhibitors of Rtt109-catalyzed histone acetylation. This compound showed publication-quality low micromolar IC50 values in a set of three orthogonal in vitro assays. However, during subsequent experiments, it became clear that this compound and its structural analogs have several problematic features. Due to the conjugated nature of its poly-aromatic structure, compound 1a is able to interfere with the fluorescence-based readout of our CPM-based HTS, and conceivably other optical-based assays as well. Compound 1a showed evidence of redox-activity, but only at relatively high compound concentrations. Compound 1a does not appear to be thiol reactive in our system, as shown by the CoA-CPM counter-screen, the lack of detectable adducts by UPLC-MS, and the additional mechanistic experiments for time-dependence and reversibility. While compound 1a was not flagged as a PAINS, in retrospect it was flagged by the ‘Rapid Elimination of Swill’ (REOS) filters our group periodically employs (Table 1).89

Compound 1a was flagged for its aggregation tendencies in a β-lactamase counter-screen for chemical aggregators. A teaching point is the importance of detergent concentration, as the IC50 values of compound 1a varied by at least an order of magnitude depending on the amount of Triton X-100 present (Fig. 3B). While we and others have used 0.01% Triton X-100 as our default detergent concentration, our data suggest even higher concentrations of detergent can further attenuate the potency of certain compounds like compound 1a. Therefore, if non-specific inhibition or chemical aggregation is suspected, it may be worth testing the effect of additional detergent on the bioactivity of a test compound. One possible explanation for this observation is that aggregate formation may not be completely attenuated at this standard detergent concentration for chemotype 1, or that this additional detergent disrupts some non-aggregate-related compound–protein interactions. There are also examples of screening compounds forming bioactive aggregates in the presence of detergent. For instance, the compound titled ‘1541’ assembles into non-globular nanofibrils capable of activating procaspase-3.90 These and other explanations for the assay behavior of compound 1a and analogs are possible, and are the subject of ongoing studies.

Only after performing extensive studies did our project team abandon further work on this scaffold. A summary of the pros and cons of this scaffold is provided (Table 7). Notable arguments supporting the utility of compound 1a and its analogs include its low micromolar in vitro IC50 values, its activity in several orthogonal assays, its synthetic accessibility and its lack of identifiable redox-activity or thiol-reactivity in our hands. Counter-arguments include its poor calculated physicochemical properties, its lack of selectivity, its tendency to form chemical aggregates in our assay buffer, its perturbation of the unrelated ALARM NMR protein and the bioassay promiscuity of related compounds. One reason this compound was pursued, despite its lack of lead-like characteristics, was because so few compounds were identified in our HTS. Our experience with this compound argues against pursuing compounds with few lead-like characteristics and known liabilities. Of course, we note ours is only a case report and care should be taken to draw broader conclusions, yet it is clear that progression of such compounds with adverse properties incurs a higher risk of failure.

Table 7.

Factors behind a ‘go/no-go’ decision

| ‘Go’ | ‘No-go’ |

|---|---|

| Active in HTS | Lack of lead-like qualities |

| Dose–response confirmed in HTS | Lack of interpretable SAR (‘flat SAR’) |

| Activity confirmed in slot blot orthogonal assay | No apparent selectivity between relevant HATs |

| Activity re-confirmed by commercial re-supply | Positive in aggregation counter-screen (β-lactamase) |

| Moderate aqueous solubilitya; 1a | Fluorescent interference |

| Activity confirmed by radiolabeled HAT assay (second orthogonal assay) | ALARM NMR positive ± DTT |

| Low micromolar activity in multiple in vitro assays | Promiscuous bioactive analogs in PubChem |

| Minimal redox-activity in counter-screen (HRP-PR) | Publications with analogs active versus unrelated targets |

| Synthetically and commercially accessible analogs | Frequent hitters in corporate HTS setting |

| Stable in assay conditions | |

| No thiol adducts detected (UPLC–MS) |

The attributes of compound 1a and its 4-aroyl-1,5-disubstituted-3-hydroxy-2H-pyrrol-2-one chemotype 1 were divided into factors that were generally favorable (‘go’) or unfavorable (‘no-go’) for project progression.

50 μg/mL (PBS, pH 7.4).

Our experiments and cheminformatics analyses provide several insights into the SAR/SIR of chemotype 1 (Fig. 8). For example, the 3-hydroxy position is critical for in vitro activity in multiple assays, including anti-HAT activity, ALARM NMR and an AmpC chemical aggregation counter-screen. Strikingly, all 3-amino analogs that we tested were inactive in these assays. Next, no dramatic differences were observed with regard to anti-HAT activity of the furan and thiophene analogs connected to the C4-position, suggesting these two groups, and possibly other aromatic groups, are interchangeable at this position. The types and positions on the phenyl ring connected at the C5-position were also interchangeable. Similarly, the heteroaromatic substituents anchored at the N1-position appeared interchangeable. Direct N-alkyl substituents at this position showed reduced potency (e.g., compounds 1s–1y), with the exception of compound 1i.

Though N1-alkyl substitution was predicted to have an effect on acidity of the 3-hydroxy group (median predicted pKa 3.8 for polyaromatic compounds; 5.1 for N1-alkyl substituted compounds in the sets E and C from Table 6), acidity of the group was not predictive of anomalous behavior in assays, nor could a relationship be identified with other properties like solubility or lipophilicity. Subsequent measurement of aliphatic-substituted compounds 1w and 1x, and the aromatically-substituted compound 1z suggested that their acidity was even more similar than predicted, with experimental pKa values of 3.3 and 3.6 for 1w and 1x, and 3.0 for 1z (Nissink, unpublished results).

Work on this compound could have been halted earlier with a better-designed post-HTS system and project management. In hindsight, a more thorough literature and database search prior to performing more labor-intensive in vitro assays could have prevented further work on this series. We should also have more strongly weighted the contribution of calculated physicochemical properties in our triage. We also encountered some opposition from members of the project team who had more experience with the biological sciences and were less familiar with medicinal chemistry and HTS. Last but not least, there was also some reluctance to cease work on a project many years in the making; an example of a sunk cost conundrum. In several projects we have encountered hesitancy from non-chemists to make key project decisions based on structural arguments alone, and it was only after generating experimental data that these members of the project could be convinced otherwise. This is in contrast with best practice in corporate screening environments where historical data are available and used extensively to triage HTS outcome upfront and provide annotation of hits.48,88,89,91 Better communication at the start of the project between members of the chemistry and biology arms of the project would likely have led to earlier agreement on a ‘no-go’ decision.

Our experience with chemotype 1 leads us to make several recommendations. It may be useful to include this substructure in future HTS cheminformatics filters, such as those used for flagging PAINS and other liable substructures. Annotation through use of such filters as a first step could highlight issues for scaffolds, or at least alert researchers to the chemotype so that wasteful follow-up can be prevented. Use of such information as an annotation together with a wider ‘body of evidence’ for or against a compound is preferred, as application of such alerts for the purpose of elimination could lead to ‘throwing the baby out with the bathwater’. Some 4-aroyl-1,5-disubstituted-3-hydroxy-2H-pyrrol-2-ones may actually represent true hits and bona fide lead compounds, and data mining of the wider class in a corporate collection suggests that incidence of anomalous behavior is elevated, but not across all of the class. There appears to be one example of this scaffold forming a crystal structure with its proposed target.68 Based on the body of work pertaining to chemotype 1, we believe investigators should carefully consider the wisdom of working with this particular compound class in an early drug discovery setting, unless there is confirmation of useful target engagement (plus selectivity) and ways can be envisaged to move away from the 4-aroyl-1,5-disubstituted-3-hydroxy-2H-pyrrol-2-one chemotype.

The observation that compounds with chemotype 1 are active against a variety of biological targets in multiple assay systems should cause concern and instigate closer inspection if these compounds show up as actives. Of course, the counter-argument is that specificity may be attainable with sufficient medicinal chemistry optimization. This is certainly feasible, but it may not be without expending considerable resources (including financial, animal, and personnel costs) or a high likelihood of failure. One may also invoke this scaffold as ‘privileged’ but the overwhelming majority of reports using this scaffold do not provide evidence of specific and therapeutically-useful target engagement such as proteinligand crystal structures. Because of the concerns raised in this report, we believe those choosing to work with this scaffold should carefully evaluate such compounds for selectivity, stability, redoxactivity, aggregation, and thiol-reactivity in their specific systems. Adverse observations increase the level of risk that a compound will fail, and a researcher should consider the cost of taking on that risk.

Our experience with this scaffold supports the use of ALARM NMR and other triage tools in the post-HTS setting. Compound 1a and some of its analogs were ALARM NMR-positive independent of DTT concentration. This finding supports another (simultaneous) benefit of performing ALARM NMR in HTS triage, as it can help identify compounds that likely non-specifically modulate the conformation of the La antigen. In our case, compounds that can modulate a protein like the La antigen, a target that is completely unrelated to Rtt109, should raise suspicions about their utility as potential therapeutics or chemical probes. Employing such a strategy to gauge off-target modulation is likely broadly applicable to HTS triage.

In summary, the 4-aroyl-1,5-disubstituted-3-hydroxy-2H-pyrrol-2-one chemotype 1 discussed in this report has been shown to have poor properties including indiscriminate binding behavior, and our experience highlights the importance of considering historical knowledge, physicochemical properties and a suitable triaging cascade of post-HTS assays to identify truly promising leads. We also recommend the more frequent publication of ‘no-go’ compound decisions, especially where the compounds are not recognized by known substructure filters.92

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Minnesota Partnership for Biotechnology and Medical Genomics (73-01 to M.A.W. and Z.Z.), the NIH (GM72719 and GM81838 to Z.Z.), the Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research and the Minnesota Supercomputing Institute. J.L.D. was supported by an NIH predoctoral fellowship (F30 DK092026-01), a Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America Foundation predoctoral pharmacology/toxicology fellowship and the Mayo Foundation. Funding for NMR instrumentation was provided by the Office of the Vice President for Research, the University of Minnesota Medical School, the University of Minnesota College of Biological Science, the NIH, the NSF and the Minnesota Medical Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The opinions or assertions contained herein belong to the authors and are not necessarily the official views of the funders.

The authors gratefully acknowledge: Mr. Todd Rappe and Drs. Georges Mer, Chaohong Sun and Youlin Xia for assistance with ALARM NMR; Drs. Sergei Gaidamakov and Richard Maraia for the plasmid containing the full-length human La antigen; Dr. Philip Cole for the p300-BHC plasmid; Dr. Rebecca J. Burgess for producing the Gcn5–Ada2–Ada3 complex; Dr. Matt Wood for providing the experimental pKa measurements; and the Minnesota NMR Center.

Abbreviations

- acetyl-CoA

acetyl coenzyme A

- ALARM NMR

a La assay to detect reactive molecules by nuclear magnetic resonance

- Asf1

anti-silencing function 1

- AZ

AstraZeneca

- BME

β-mercaptoethanol

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CoA

coenzyme A

- CPM

N-[4-(7-diethylamino-4-methylcoumarin-3-yl)phenyl]-maleimide

- dH3–H4

Drosophila histone H3–H4

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- GSH

Glutathione

- H3K9

histone H3 lysine 9

- H3K27

histone H3 lysine 27

- H3K56

histone H3 lysine 56

- H3K56ac

histone H3 lysine 56 acetylation

- HAT

histone acetyltransferase

- HMQC

heteronuclear multiple quantum coherence

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- HRMS

high-resolution mass spectrometry

- HRP-PR

horseradish peroxidase-phenol red

- HTS

high-throughput screen or high-throughput screening

- IC50

half maximal inhibitory concentration

- IPTG

isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside

- logD

distribution coefficient

- logP

partition coefficient

- m/z

mass-to-charge ratio

- LRMS-ESI

low-resolution mass spectrometry–electrospray ionization

- MeCN

acetonitrile

- MeOH

methanol

- MS

mass spectrometry

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- PAINS

pan-assay interference compounds

- pBSF

negative log of binomial survivor function

- REOS

Rapid Elimination Of Swill

- Rtt109

regulator of Ty1 transposition 109

- SAR

structure–activity relationship

- SDS–PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- SIR

structure–interference relationship

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- UPLC

ultra-performance liquid chromatography

- Vps75

vacuolar protein sorting 75

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Files containing these data include: (1) Supporting information, which contains materials and methods, characterization data for compound 1a, Figures S1–S8, Tables S1–S3, and author contributions; (2) a CSV file containing SMILES, InChI, InChIKey and activity data for compounds 1a–1z and 2a–2l; and (3) a corresponding MOL file.

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.08.020. These data include MOL files and InChiKeys of the most important compounds described in this article.

References and notes

- 1.Dahlin JL, Walters MA. Future Med Chem. 2014;6:1265. doi: 10.4155/fmc.14.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wipf P, Arnold D, Carter K, Dong S, Johnston PA, Sharlow E, Lazo JS, Huryn D. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009;9:1194. doi: 10.2174/156802609789753590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huryn DM, Smith AB. Curr Top Med Chem. 2009;9:1206. doi: 10.2174/156802609789753653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devine S, Mulcair M, Debono C, Leung E, Nissink J, Lim S, Chandrashekaran I, Vazirani M, Mohanty B, Simpson J, Baell J, Scammells P, Norton R, Scanlon M. J Med Chem. 2015;58:1205. doi: 10.1021/jm501402x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han J, Zhou H, Horazdovsky B, Zhang K, Xu R, Zhang Z. Science. 2007;315:653. doi: 10.1126/science.1133234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahlin JL, Chen X, Walters MA, Zhang Z. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2014;50:31. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2014.978975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dahlin JL, Kottom TJ, Han J, Zhou H, Walters MA, Zhang Z, Limper AH. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:3650. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02637-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wurtele H, Tsao S, Lépine G, Mullick A, Tremblay J, Drogaris P, Lee E-H, Thibault P, Verreault A, Raymond M. Nat Med. 2010;16:774. doi: 10.1038/nm.2175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopes da Rosa J, Bajaj V, Spoonamore J, Kaufman PD. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2013;23:2853. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2013.03.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lopes da Rosa J, Boyartchuk VL, Zhu LJ, Kaufman PD. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912427107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dahlin JL, Sinville R, Solberg J, Zhou H, Francis S, Strasser J, John K, Hook DJ, Walters MA, Zhang Z. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e78877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baell JB. Future Med Chem. 2010;2:1529. doi: 10.4155/fmc.10.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baell JB, Ferrins L, Falk H, Nikolakopoulos G. Aust J Chem. 2013;66:1483. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baell JB, Holloway GA. J Med Chem. 2010;53:2719. doi: 10.1021/jm901137j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baell J, Walters MA. Nature. 2014;513:481. doi: 10.1038/513481a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahlin JL, Nissink JWM, Strasser JM, Francis S, Zhou H, Zhang Z, Walters MA. J Med Chem. 2015;58:2091. doi: 10.1021/jm5019093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Congreve M, Carr R, Murray C, Jhoti H. Drug Discovery Today. 2003;8:876. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02831-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rishton GM. Drug Discovery Today. 2003;8:86. doi: 10.1016/s1359644602025722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malo N, Hanley JA, Cerquozzi S, Pelletier J, Nadon R. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:167. doi: 10.1038/nbt1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. J Comb Chem. 2000;2:258. doi: 10.1021/cc9900706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gubler H, Schopfer U, Jacoby E. J Biomol Screen. 2013;18:1. doi: 10.1177/1087057112455219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hermann JC, Chen Y, Wartchow C, Menke J, Gao L, Gleason SK, Haynes N-E, Scott N, Petersen A, Gabriel S, Vu B, George KM, Narayanan A, Li SH, Qian H, Beatini N, Niu L, Gan Q-F. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2013;4:197. doi: 10.1021/ml3003296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tarzia G, Antonietti F, Duranti A, Tontini A, Mor M, Rivara S, Traldi P, Astarita G, King A, Clapper JR, Piomelli D. Ann Chim. 2007;97:887. doi: 10.1002/adic.200790073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacob NT, Lockner JW, Kravchenko VV, Janda KD. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:6628. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park J-G, Kahn JN, Tumer NE, Pang Y-P. Sci Rep. 2012;2:631. doi: 10.1038/srep00631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenseth JR, Coldiron SJ. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8:418. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung CC, Ohwaki K, Schneeweis JE, Stec E, Varnerin JP, Goudreau PN, Chang A, Cassaday J, Yang L, Yamakawa T, Kornienko O, Hodder P, Inglese J, Ferrer M, Strulovici B, Kusunoki J, Tota MR, Takagi T. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2008;6:361. doi: 10.1089/adt.2007.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Simeonov A, Jadhav A, Thomas CJ, Wang Y, Huang R, Southall NT, Shinn P, Smith J, Austin CP, Auld DS, Inglese J. J Med Chem. 2008;51:2363. doi: 10.1021/jm701301m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gribbon P. Drug Discovery Today. 2003;8:1035. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02895-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turek-Etienne TC, Small EC, Soh SC, Xin TA, Gaitonde PV, Barrabee EB, Hart RF, Bryant RW. J Biomol Screen. 2003;8:176. doi: 10.1177/1087057103252304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vedvik KL, Eliason HC, Hoffman RL, Gibson JR, Kupcho KR, Somberg RL, Vogel KW. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2004;2:193. doi: 10.1089/154065804323056530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gul S, Gribbon P. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2010;5:681. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2010.495748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jadhav A, Ferreira RS, Klumpp C, Mott BT, Austin CP, Inglese J, Thomas CJ, Maloney DJ, Shoichet BK, Simeonov A. J Med Chem. 2010;53:37. doi: 10.1021/jm901070c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di L, Kerns EH. Chem Biodivers. 2009;6:1875. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200900061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reed D, Shen Y, Shelat AA, Arnold LA, Ferreira AM, Zhu F, Mills N, Smithson DC, Regni CA, Bashford D, Cicero SA, Schulman BA, Jochemsen AG, Guy RK, Dyer MA. J Biol Chem. 2010;287:10786. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.056747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berndsen CE, Denu JM. Methods. 2005;36:321. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gein VL, Bobyleva AA, Levandovskaya EB, Odegova TF, Vakhrin MI. Pharm Chem J. 2012;46:23. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gein VL, Fedorova NL, Levandovskaya EB, Syropyatov BY, Voronina ÉV, Danilova NV, Kovaleva MY. Pharm Chem J. 2011;45:355. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gein VL, Mar’yasov MA, Silina TA, Makhmudov RR. Pharm Chem J. 2014;47:539. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gein VL, Platonov VS, Voronina ÉV. Pharm Chem J. 2004;38:316. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao H, Sun J, Yan C-G. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2013;9:2934. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.9.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhuang C, Miao Z, Zhu L, Dong G, Guo Z, Wang S, Zhang Y, Wu Y, Yao J, Sheng C, Zhang W. J Med Chem. 2012;55:9630. doi: 10.1021/jm300969t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baell J. ACS Med Chem Lett. 2015;6:229. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soares KM, Blackmon N, Shun TY, Shinde SN, Takyi HK, Wipf P, Lazo JS, Johnston PA. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2010;8:152. doi: 10.1089/adt.2009.0247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng BY, Simeonov A, Jadhav A, Babaoglu K, Inglese J, Shoichet BK, Austin CP. J Med Chem. 2007;50:2385. doi: 10.1021/jm061317y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnston PA. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2011;15:174. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnston PA, Soares KM, Shinde SN, Foster CA, Shun TY, Takyi HK, Wipf P, Lazo JS. Assay Drug Dev Technol. 2008;6:505. doi: 10.1089/adt.2008.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pearce BC, Sofia MJ, Good AC, Drexler DM, Stock DA. J Chem Inf Model. 2006;46:1060. doi: 10.1021/ci050504m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Feng BY, Shoichet BK. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:550. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Frenkel YV, Clark AD, Das K, Wang Y-H, Lewi PJ, Janssen PAJ, Arnold E. J Med Chem. 2005;48:1974. doi: 10.1021/jm049439i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McGovern SL, Caselli E, Grigorieff N, Shoichet BK. J Med Chem. 2002;45:1712. doi: 10.1021/jm010533y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Inglese J, Auld DS, Jadhav A, Johnson RL, Simeonov A, Yasgar A, Zheng W, Austin CP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11473. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Prinz H. J Chem Biol. 2012;5:1. doi: 10.1007/s12154-011-0069-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Prinz H. J Chem Biol. 2010;3:37. doi: 10.1007/s12154-009-0029-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shoichet BK. J Med Chem. 2006;49:7274. doi: 10.1021/jm061103g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Copeland RA. Evaluation of enzyme inhibitors in drug discovery: a guide for medicinal chemists and pharmacologists. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tang Y, Holbert M, Wurtele H, Meeth K, Rocha W, Gharib M, Jiang E, Thibault P, Verreault A, Cole P, Marmorstein R. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:738. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Burgess RJ, Zhou H, Han J, Zhang Z. Mol Cell. 2010;37:469. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huth JR, Mendoza R, Olejniczak ET, Johnson RW, Cothron DA, Liu Y, Lerner CG, Chen J, Hajduk PJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:217. doi: 10.1021/ja0455547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huth JR, Song D, Mendoza RR, Black-Schaefer CL, Mack JC, Dorwin SA, Ladror US, Severin JM, Walter KA, Bartley DM, Hajduk PJ. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:1752. doi: 10.1021/tx700319t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rishton G. Drug Discovery Today. 1997;2:382. doi: 10.1016/s1359644602025722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schebb NH, Faber H, Maul R, Heus F, Kool J, Irth H, Karst U. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2009;394:1361. doi: 10.1007/s00216-009-2765-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Epps DE, Taylor BM. Anal Biochem. 2001;295:101. doi: 10.1006/abio.2001.5173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hou X, Li R, Li K, Yu X, Sun J-P, Fang H. J Med Chem. 2014;57:9309. doi: 10.1021/jm500692u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Baeza J, Smallegan MJ, Denu JM. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10:122. doi: 10.1021/cb500848p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Copeland RA. Anal Biochem. 2003;320:1. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Foley TL, Rai G, Yasgar A, Daniel T, Baker HL, Attene-Ramos M, Kosa NM, Leister W, Burkart MD, Jadhav A, Simeonov A, Maloney DJ. J Med Chem. 2014;57:1063. doi: 10.1021/jm401752p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brown CS, Lee MS, Leung DW, Wang T, Xu W, Luthra P, Anantpadma M, Shabman RS, Melito LM, MacMillan KS, Borek DM, Otwinowski Z, Ramanan P, Stubbs AJ, Peterson DS, Binning JM, Tonelli M, Olson MA, Davey RA, Ready JM, Basler CF, Amarasinghe GK. J Mol Biol. 2014;426:2045. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zimmerman SS, Khatri A, Garnier-Amblard EC, Mullasseril P, Kurtkaya NL, Gyoneva S, Hansen KB, Traynelis SF, Liotta DC. J Med Chem. 2014;57:2334. doi: 10.1021/jm401695d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jia J, Xu X, Liu F, Guo X, Zhang M, Lu M, Xu L, Wei J, Zhu J, Zhang S, Zhang S, Sun H, You QD. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e59315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu Z, Chen Y-W, Battu A, Wilder P, Weber D, Yu W, MacKerell ADJ, Chen L-M, Chai KX, Johnson MD, Lin C-Y. J Med Chem. 2011;54:7567. doi: 10.1021/jm200920s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hirayama K, Aoki S, Nishikawa K, Matsumoto T, Wada K. Bioorg Med Chem. 2007;15:6810. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yangthara B, Mills A, Chatsudthipong V, Tradtrantip L, Verkman AS. Mol Pharm. 2007;72:86. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.034496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Arnold LA, Estebanez-Perpina E, Togashi M, Jouravel N, Shelat A, McReynolds AC, Mar E, Nguyen P, Baxter JD, Fletterick RJ, Webb P, Guy RK. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:43048. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506693200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dayam R, Al-Mawsawi LQ, Neamati N. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:6155. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tanrikulu Y, Nietert M, Scheffer U, Proschak E, Grabowski K, Schneider P, Weidlich M, Karas M, Gobel M, Schneider G. Chem Bio Chem. 2007;8:1932. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gein VL, Yushkov VV, Splina TA, Gein LF, Yatsenko KV, Shevtsova SG. Pharm Chem J. 2008;42:255. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rose R, Erdmann S, Bovens S, Wolf A, Rose M, Hennig S, Waldmann H, Ottmann C. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:4129. doi: 10.1002/anie.200907203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vidović D, Busby SA, Griffin PR, Schürer SC. Chem Med Chem. 2011;6:94. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.201000428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Floquet N, Richez C, Durand P, Maigret B, Badet B, Badet-Denisot M-A. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:1966. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.01.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bayry J, Tchilian EZ, Davies MN, Forbes EK, Draper SJ, Kaveri SV, Hill AVS, Kazatchkine MD, Beverley PCL, Flower DR, Tough DF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10221. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803453105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Davies MN, Bayry J, Tchilian EZ, Vani J, Shaila MS, Forbes EK, Draper SJ, Beverley PCL, Tough DF, Flower DR. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e8084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nevin DK, Peters MB, Carta G, Fayne D, Lloyd DG. J Med Chem. 2012;55:4978. doi: 10.1021/jm300068n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Starosylaa SA, Volynetsa GP, Lukashova SS, Gorbatiuka OB, Golubb AG, Bdzholaa VG, Yarmoluk SM. Bioorg Med Chem. 2015;23:2489. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Canny SA, Cruz Y, Southern MR, Griffin PR. Bioinformatics. 2009;28:140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Han L, Wang Y, Bryant SH. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2251. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hu Y, Bajorath J. AAPS J. 2013;15:808. doi: 10.1208/s12248-013-9488-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nissink JWM, Blackburn S. Future Med Chem. 2014;6:1113. doi: 10.4155/fmc.14.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Walters WP, Namchuk M. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2003;2:259. doi: 10.1038/nrd1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zorn J, Wille H, Wolan D, Wells J. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:19630. doi: 10.1021/ja208350u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Metz JT, Huth JR, Hajduk PJ. J Comput Aided Mol Des. 2007;21:139. doi: 10.1007/s10822-007-9109-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Cox PB, Gregg RJ, Vasudevan A. Bioorg Med Chem. 2012;20:4564. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Merchant JR, Hakim MA, Pillay KS, Patell JR. J Med Chem. 1971;14:1239. doi: 10.1021/jm00294a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gein VL, Shumilovskikh EV, Andreichikov YS, Saraeva RF, Korobchenko LV, Vladyko VG, Boreko EI. Khim-Farm Zh. 1991;25:37. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lipinski CA, Lombardo F, Dominy BW, Feeney PJ. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2001;46:3. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Veber DF, Johnson SR, Cheng H-Y, Smith BR, Ward KW, Kopple KD. J Med Chem. 2002;45:2615. doi: 10.1021/jm020017n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.