Abstract

This study tests a theoretical cascade model in which multiple dimensions of facilitator delivery predict indicators of participant responsiveness, which in turn lead to improvements in targeted program outcomes. An effectiveness trial of the 10-session New Beginnings Program for divorcing families was implemented in partnership with four county-level family courts. This study included 366 families assigned to the intervention condition who attended at least one session. Independent observers provided ratings of program delivery (i.e., fidelity to the curriculum and process quality). Facilitators reported on parent attendance and parents’ competence in home practice of program skills. At pretest and posttest, children reported on parenting and parents reported child mental health. We hypothesized effects of quality on attendance, fidelity and attendance on home practice, and home practice on improvements in parenting and child mental health. Structural Equation Modeling with mediation and moderation analyses were used to test these associations. Results indicated quality was significantly associated with attendance and attendance moderated the effect of fidelity on home practice. Home practice was a significant mediator of the links between fidelity and improvements in parent-child relationship quality and child externalizing and internalizing problems. Findings provide support for fidelity to the curriculum, process quality, attendance, and home practice as valid predictors of program outcomes for mothers and fathers. Future directions for assessing implementation in community settings are discussed.

Keywords: Program Implementation, Fidelity, Quality, Responsiveness, Home Practice, Parenting, Internalizing, Externalizing, Behavioral Observation

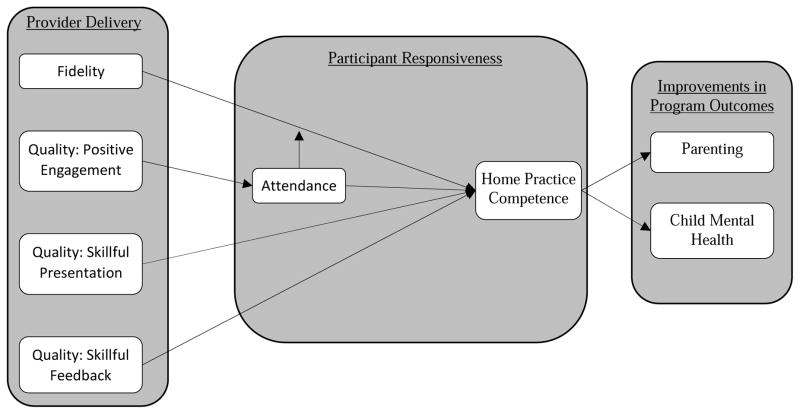

Decades of research have now demonstrated the efficacy of programs targeting parenting practices to prevent an array of negative developmental outcomes for children, including substance use, mental health problems, sexual risk behavior, delinquency, and school failure (NRC/IOM, 2009). These findings provide strong evidence for the potential of programs to have a significant public health impact if they can be implemented widely and effectively in the community. Unfortunately, programs experience declines in implementation as they move from the tight control of efficacy trials to community service delivery settings, and concordant declines in program effects are frequently observed (Gottfredson et al., 2006). To increase public health impact, there is a need to understand how the delivery of programs in community settings affects program outcomes. In addition to the theoretical importance of testing programs’ “action theory” (West, Aiken, & Todd, 1993), this is also necessary to identify critical indicators of successful implementation and provide useful feedback for quality improvement. Multiple dimensions of implementation have been identified as predictive of program outcomes (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). Because collecting program implementation data can be resource intensive (Schoenwald et al., 2011), it is necessary to determine which indicators are most closely associated with target outcomes. Taking a theoretical perspective on how different dimensions of implementation interrelate to influence program outcomes can provide guidance on how programs work and which dimensions are critical to monitor and maintain. A theoretical implementation cascade model (Berkel, Mauricio, Schoenfelder, & Sandler, 2011) suggests facilitator delivery, including fidelity to the curriculum and process quality, influence program outcomes by encouraging aspects of participant responsiveness, such as attendance and competent home practice of program skills (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical Cascade Model Linking Provider Delivery, Participant Responsiveness, and Improvements in Program Outcomes

Participant Responsiveness

Previous taxonomies of implementation have treated responsiveness as a single construct (Dane & Schneider, 1998; Durlak & DuPre, 2008) and several studies have found that composite measures of responsiveness predict positive program outcomes (e.g., Schoenfelder et al., 2012). However, rather than being considered as pieces of one multidimensional construct, these components may more appropriately be seen as dynamically interrelated, but distinct indicators (Berkel et al., 2016). Although attendance is the most commonly assessed component of responsiveness (Durlak & DuPre, 2008), it is likely that merely showing up is not in itself sufficient to create change. Theoretically, participants must actively engage with and use the program content and skills to create meaningful change in their daily context. Completion of home practice assignments has been linked to improvements in program outcomes (Clarke et al., 2015; Riggs, Elfenbaum, & Pentz, 2006; Ros, Hernandez, Graziano, & Bagner, 2016). Moreover, how well participants do home practice may be more predictive of improvements in program outcomes than simply whether assignments are done (Kazantzis, Deane, & Ronan, 2004).

Berkel and colleagues (2016) tested the effects of multiple indicators of home practice on improvements in parenting using data from an effectiveness trial of the New Beginnings Program (NBP; Sandler et al., 2016). NBP is a 10-session evidence-based program targeting parenting skills in several domains (i.e., parent-child relationships, discipline, and protecting children from interparental conflict) to improve child adjustment after divorce (Wolchik, Sandler, Weiss, & Winslow, 2007). Facilitator ratings of parent competence in home practice assignments targeting parent-child relationships and discipline predicted improvements in those respective domains. These effects were above and beyond the effect of attendance, providing support for the program’s action theory that “home practice is the program.”

Facilitator Delivery

Given these findings, it is important to identify aspects of facilitator delivery that promote attendance and home practice competence. Fidelity, or the extent to which the facilitator adheres to the curriculum, is the most commonly studied dimension of facilitator delivery (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). The assessment of fidelity is the only way to determine if content of a program was delivered in the way its developer intended. Some studies have failed to find a link between fidelity and program outcomes (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). Rather than an indication that fidelity to the curriculum is not necessary to achieve program effects, one possible explanation is related to the specificity of measurement (Berkel, et al., 2011). For example, while most studies have assessed the link between fidelity of the program as a whole to program outcomes, we suggest a more targeted approach where fidelity to program activities in which specific skills are taught to improvements in those respective outcomes. In the Strong African American Families program, fidelity to activities targeting racial socialization was linked to increases in racial socialization, whereas global fidelity ratings were not (Berkel, Murry, Roulston, & Brody, 2013). In the current study, we propose mediational pathways in which fidelity to activities in which skills were taught or reinforced predicts improvements in parenting and child adjustment, by increasing competent home practice of those skills.

A second possible reason that some studies have not found an association between fidelity and outcomes is that moderators may inhibit the effects. For example, facilitators’ fidelity to the curriculum is only relevant to the extent that participants are exposed to it. Previous work has found support for a moderational effect of attendance on the association between fidelity and outcomes (Berkel, et al., 2013). In the current study, we also propose a moderational effect of attendance on the link between fidelity and home practice competence.

In addition to fidelity, process quality has also been linked with program outcomes (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). It has been operationalized in a variety of ways, such as the clarity with which the facilitator presents information, their efforts to connect with participants, and their clinical skill in helping participants apply program content to create improvements in their daily lives (Durlak & DuPre, 2008). Although quality has often been treated as a single construct, distinct aspects of quality may uniquely support different aspects of participants’ response to the program. For example, the clarity with which facilitators deliver the program material (which we refer to as “skillful presentation”) and facilitators’ use of constructive feedback (i.e., “skillful feedback”) may enhance participants’ competence in using program skills. On the other hand, a facilitator’s interpersonal rapport building efforts (i.e., “positive engagement”) are likely to influence participants’ attendance (Orrell-Valente, Pinderhughes, Valente, & Laird, 1999), which may indirectly influence home practice competence by giving parents more opportunities to practice and receive feedback on the skills.

Parent Gender

Finally, a third reason fidelity may have limited effects on program outcomes is cultural mismatch when programs are delivered to cultural subgroups who are distinct from the groups in which the program was initially developed and tested. In this case, a lack of an effect of fidelity may indicate a cultural mismatch and suggest that adaptations are required. Because mothers have traditionally been the primary targets of parenting programs, they have also been the primary participants in implementation studies. Over the past decade however, fathers’ involvement with children has been growing, especially for divorcing fathers (Stevenson, Braver, Ellman, & Votruba, 2013). Consequently, NBP went through an adaptation process to ensure relevance for divorcing fathers (Sandler, et al., 2016). NBP was associated with improvements in fathers’ parenting and their children’s mental health (Sandler et al., 2017). Moreover, fathers’ competence in doing home practice explained improvements in parenting (Berkel, et al., 2016). Because this trial was the first time NBP was tested with fathers, it is especially important to determine how to promote home practice competence and subsequent program outcomes for this group. If fidelity to the adapted NBP curriculum is associated with fathers’ competent home practice and improvements in program outcomes, this would bolster our confidence that the program works as intended across gender. In addition, because previous measures of quality have been developed primarily with mothers, we do not know if these processes work similarly with fathers. Moreover, there is some evidence that masculinity norms can inhibit engagement in services (Cusack, Deane, Wilson, & Ciarrochi, 2006; Triemstra, Niec, Peer, & Christian-Brandt, 2016). Consequently, the presence of gender differences with respect to the influence of fidelity and quality is an exploratory question in this study.

In summary, the current study uses data from the NBP to test a theoretical implementation cascade model whereby dimensions of provider delivery influence program outcomes through participant responsiveness. Specifically, we hypothesize that facilitators’ positive engagement will be positively associated with parent attendance, which will in turn be linked with parents’ competence in home practice. We also hypothesize that fidelity, skillful presentation, and skillful feedback will be positively associated with competent home practice. Attendance is tested as a moderator of the effect of fidelity on home practice competence. We expand previous analyses to examine the effects of home practice competence on child mental health and present odds ratios to enhance the clinical significance of the findings. We test indirect effects of facilitator delivery and improvements in parenting and child mental health outcomes through participant responsiveness. Finally, as an exploratory analysis, we assess parent gender as a potential moderator.

Methods

The study uses pretest, posttest, and implementation data from families randomly assigned to the intervention condition of the NBP effectiveness trial, conducted in partnership with four county-level family courts across Arizona (Sandler, et al., 2016). Eligibility criteria for the effectiveness trial were that a parent was divorced or separated within the past 2 years, had a child between 3 and 18 years with whom there was regular contact (i.e., ≥ 3 times per week or 1 overnight every other week), and could complete the program in English. Parents were primarily recruited using a brief video shown during a 4-hour program mandated for all divorcing parents in Arizona. Other recruitment methods were media, word of mouth, or community agents (e.g., judges, lawyers). Because we are interested in the influence of facilitator delivery, inclusion in the current study was limited to the 366 families who ever attended. In terms of race/ethnicity: 31% were Latino, 62% were Non-Latino White, and 8% represented other groups. Fathers represented 45% of the sample. Although there was no intentional effort to recruit multiple parents from the same family, in 28 families, a second parent also participated. The second parent to enroll was assigned to the same condition as the first parent. Of the 682 children whose parent participated in at least one session, 247 children were above 9 and provided interview data; of these, 51% were male.

Program Overview

The NBP targets parenting skills related to positive relationship quality, discipline, and interparental conflict, which have been demonstrated to protect children from the negative impact of divorce (Wolchik, et al., 2007). Single-gender mother (N=26) or father (N=24) groups were implemented over four cohorts. In each NBP session, the facilitator taught new skills related to targeted parenting domains (see Table 1) in didactic activities, then parents role-played those skills in skills practice activities. At the end of each session, the facilitator assigned parents to practice the skills with their children at home. The first activity of the following week’s session consisted of a home practice review during which each parent reported on home practice and received feedback and support from the facilitator and other group members. Home practice was cumulative such that once a skill was taught, it was assigned every week.

Table 1.

Study Measures

| Measure | # of Items | Scale | Rater | Collected | Example | Reliability/Validity | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment Measures | |||||||||||||||

| Acceptance | 16 | 1 – 5 | C | W1; W2 | Your [parent] enjoyed doing things with you | W1 α =.95; W2 α = .95 | |||||||||

| Rejection | 16 | 1 – 5 | C | W1; W2 | Your [parent] acted as though you were in the way | W1 α =.86; W2 α = .88 | |||||||||

| Communication | 10 | 1 – 5 | C | W1; W2 | Your [parent] tried to understand your point of view | W1 α =.92; W2 α = .90 | |||||||||

| Internalizing | 31 | 0 – 2 | P | W1; W2 | [Child] feels worthless or inferior | W1 α =.89; W2 α = .89 | |||||||||

| Externalizing | 35 | 0 – 2 | P | W1; W2 | [Child] gets in many fights | W1 α =.90; W2 α = .90 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Provider Delivery | |||||||||||||||

| Fidelity | M = 25 items per activity (range = 13–48) | 0 – 2 | IO | One activity per session | Explain that Family Fun Time is an important way to start new family traditions that children can count on | Mean item-level ICC =.86, SD = .16 | |||||||||

| Quality | |||||||||||||||

| -Positive Engagement | 8 | 1 – 5 | IO | One activity per session | Reinforced parents for sharing | Mean item level ICC = .67 (.03); Cronbach’s α = .85 | |||||||||

| -Skillful Presentation | 9 | 1 – 5 | IO | One activity per session | Provided helpful examples to clarify program content | Mean item level ICC = .68 (.05); Cronbach’s α = .89 | |||||||||

| -Skillful Feedback | 7 | 1 – 5 | IO | One activity per session | Told parents specifically what they did well | Mean item level ICC = .68 (.06); Cronbach’s α = .72 | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Participant Responsiveness | |||||||||||||||

| Attendance | 1 / session | 0 – 1 | F | Weekly | Did [parent] attend tonight? | NA | |||||||||

| Home Practice Competence | 1 / assigned skill per session (see below) | 1 – 5 | F | Weekly | How do you think [parent] did on Family Fun Time this week? | Convergent validity with parent self-report: r = .59*** | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Parenting Domain | Skill | Session when skill was assigned: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| Relationship Skills | Family Fun Time | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||

| One on One Time | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| Catch ‘em Being Good | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||

| Good Listening | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||

| Interparental Conflict | Keeping Children Out of the Middle | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ||||||||||

| Positive Discipline | Change Plan | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | |||||||||||

Notes: F=Facilitator; IO=Independent Observer; C=Child; P=Parent;

p≤.001;

p≤.01;

p≤.05;

p≤.1

We have previously identified an association between home practice and improvements in parenting outcomes for parent-child relationship skills and discipline skills (Berkel, et al., 2016). Because skill assignments were cumulative (see Table 1), we have more home practice ratings per family for parent-child relationship skills (9) compared to discipline skills (3). Further, attrition over time led to more families having missing data for discipline skills (47%) relative to parent-child relationship skills (17%). Consequently, the current study focuses on program activities and home practice assignments related to developing parent-child relationship skills.

Responsiveness Data Collection and Measures

This study uses two indicators of participant responsiveness: attendance and home practice competence (see Table 1) which were entered by the facilitator into a web-based data collection system following each weekly session. For attendance, a percentage was calculated as the number of sessions attended out of a total possible 10 sessions. Parents reported on their home practice on a worksheet assigned each week. Facilitators used parent responses from the worksheets and home practice review discussions to rate parents’ competence with the skills. If parents forgot their worksheets, facilitators provided another copy to complete during the home practice review activity. Parents who missed a session were able to turn in the worksheet late. If parents missed the session and did not turn in the assignment later, data were coded as missing. The nine weekly ratings for home practice competence of parent child relationship skills were averaged for the current study.

Provider Delivery Data Collection and Measures

Coding of fidelity and quality was conducted by separate teams of independent observers to prevent halo effects (Hogue, Liddle, & Rowe, 1996). Independent observers watched videos of sessions and coded transcripts of the sessions in NVivo. This process promotes transparency of the ratings and allows for segments of the transcript to be used in weekly calibration meetings to support interrater reliability. Using purposeful sampling methods, we selected one activity per session that represented the range of activity types used by the program: didactic activities to teach new skills (N=3), skills practice activities where new skills were role played (N=3), and home practice reviews where parents reported back on how their skills went over the past week (N=4). This resulted in ratings for 500 activities (one activity in each of 10 sessions for 50 groups). The first five sessions (see Table 1) addressed skills to build parent-child relationship quality and were thus included in the current study. This resulted in fidelity and quality ratings for one didactic activity, three home practice reviews, and one skills practice, which were each averaged for the purposes of this study.

Fidelity

We converted each instruction in the manual into a fidelity item. Multiple raters were used to assess Intraclass Correlations for 22% of activities (Cicchetti, 1994); item-level ICCs were in the excellent range (see Table 1). The fidelity score was a percentage calculated for each activity, representing the total number of points received during the activity out of the total possible.

Quality

We created the quality measure by reviewing existing measures (e.g., Eames et al., 2008; Forgatch, Patterson, & DeGarmo, 2005; Lochman et al., 2009) for items that fit the process theory of NBP. Based on the three types of activities in NBP (didactic, skills practice, and home practice review), we created three subscales: positive engagement, skillful presentation, and skillful feedback (see Table 1). Although we speculated that different aspects of quality might be relevant in different types of activities (i.e., positive engagement for all types of activities, skillful presentation for didactic activities, and skillful feedback for skills practice activities or home practice reviews) all subscales were coded for all activities. Intraclass correlations were used to assess interrater reliability on 22% of the activities; item-level ICCs were in the good range (Cicchetti, 1994). Confirmatory Factor Analysis in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 2012) was used to assess the dimensionality of the subscales (see Table 2). A review of modification indices suggested that one item, “Used good body language and eye contact,” should load on the skillful presentation subscale, rather than the positive engagement subscale. With this item moved, all items loaded significantly on their respective subscales and model fit was adequate.

Table 2.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Quality Subscales

| Positive Engagement | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2 | Showed warmth and support | .81 |

| 3 | Reinforced parents for sharing | .70 |

| 4 | Encouraged participation by all members of the group | .69 |

| 5 | Promoted group cohesiveness | .64 |

| 6 | Pointed out similarities between parents | .53 |

| 7 | Used good active listening skills | .62 |

| 8 | Validated and normalized parents experiences | .68 |

| 9 | Respected for all values and belief systems | .46 |

|

| ||

| Skillful Presentation | ||

|

| ||

| 1 | Used good body language and eye contact | .82 |

| 10 | Showed enthusiasm for the material being presented | .86 |

| 11 | Presented the material in a natural manner | .84 |

| 12 | Established professional expertise of themselves or the program | .73 |

| 13 | Demonstrated a good understanding of the material | .75 |

| 14 | Provided helpful examples to clarify program content | .59 |

| 15 | Connected program materials and skills to parents personal situations | .44 |

| 16 | Expressing confidence that the skills will work | .59 |

| 17 | Linking to other parts of the program (forecasting or referring back) | .52 |

|

| ||

| Skillful Feedback | ||

|

| ||

| 20 | Told parents specifically what they did well | .70 |

| 21 | Indicated belief in parents ability to use the skills well | .63 |

| 22b | Gave specific, corrective feedback whenever needed | .55 |

| 23b | Helped parents problem solve | .60 |

| 24 | Provided appropriate guidance on how to use a skill | .70 |

| 25b | Showed flexibility and creativity while sticking to the program’s underlying theory | .53 |

| 26b | Linked skill use to changes in children or relationships | .53 |

Notes: χ2(247) = 753.36, p ≤ .001; RMSEA=.07(.06–.07); SRMR=.06; and CFI=.90; all loading were p ≤ .001

Program Outcome Data Collection and Measures

Assessments were conducted in English via telephone with target parents (N = 366), and with children age nine and above (N = 247), at pre-test (W1) and post-test (W2). W1 occurred up to two months before Session 1 and W2 occurred up to two months after Session 10, with an average of 20 weeks between. Parents provided consent for themselves and for children; children provided assent. Families were reimbursed $100 for parent interviews and $50 for child interviews, but were not compensated for attending the program. Details for the parent-child relationship quality indicators [CRPBI Acceptance and Rejection subscales (Schaefer, 1965) and the Parent Adolescent Open Communication scale (Barnes & Olson, 1982)] and child mental health indicators (Achenbach & Edelbrock, 1983) are presented in Table 1.

Analytic Strategy

Study hypotheses were tested in Mplus, using Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) for missing data (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). Participants were nested within 50 intervention groups; a unique group identifier was used as a cluster variable. When multiple children per family participated in data collection (N=221 families), an average across children was used to avoid an additional layer of nesting. Parent-child relationship was modeled as a latent construct at each wave. W1 program outcome variables (relationship quality and child internalizing and externalizing) were included in the model to control for baseline levels. Multiple fit indices were used to evaluate the adequacy of model fit: either a non-significant 2 or a combination of SRMR ≤ .08, RMSEA ≤ .08, and CFI ≥ .90 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). To test moderation, predictors (fidelity and attendance) were centered prior to the creation of the interaction term and all were entered in the model simultaneously (Aiken & West, 1991). The moderational effect of attendance was probed using Interaction v.1.7 (Soper, 2006–2011). RMediation (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011) was used to assess the significance of indirect effects from provider delivery to program outcomes; confidence intervals are considered significant if they do not cross zero (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). Finally, to test possible gender differences in the path coefficients, we estimated the model constraining one pathway at a time. Wald Tests were used to test whether declines in model fit were significant, indicating gender differences for those specific pathways. Finally, to rule out possible alternative explanations, we conducted a number of alternative models described below.

Results

Correlations, means, and standard deviations are presented in Table 3. Correlations between the quality subscales were high (range = .77–.88), and they were positively correlated with fidelity (range = .13–.25). W1 externalizing negatively predicted home practice competence. Facilitators’ positive engagement and skillful presentation scores were positively correlated with participant attendance, but not with home practice competence or W2 outcomes. Attendance was negatively associated with W2 externalizing. Fidelity and attendance were positively associated with home practice competence. Home practice competence was positively associated with W2 acceptance and communication, and negatively associated with W2 rejection, internalizing, and externalizing. Every unit increase in home practice competence reduced children’s risk of developing a borderline diagnosis for internalizing by half (OR = .51) and for externalizing by 1/3 (OR = .65). Finally, we found higher scores among mothers than fathers on W1 communication, internalizing, and externalizing, and facilitators’ positive engagement, skillful presentation, and fidelity.

Table 3.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations for All Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 1. Acceptance | -- | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Rejection | −.64*** | -- | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Communication | .76*** | −.51*** | -- | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Internalizing | .05 | −.02 | −.01 | -- | |||||||||||||

| 5. Externalizing | −.13 | .19* | −.07 | .62*** | -- | ||||||||||||

| Implementation | |||||||||||||||||

| 6. Positive Engagement | .06 | −.08 | .04 | .05 | .04 | -- | |||||||||||

| 7. Skillful Presentation | .05 | −.11 | .03 | .02 | −.01 | .88*** | -- | ||||||||||

| 8. Skillful Feedback | .06 | −.07 | −.02 | .01 | −.03 | .74*** | .77*** | -- | |||||||||

| 9. Fidelity | .01 | −.02 | .03 | .05 | .01 | .25*** | .15*** | .13** | -- | ||||||||

| 10. Attendance | .19* | −.18* | .12 | −.05 | −.06 | .15*** | .11* | .06 | .04 | -- | |||||||

| 11. Home Practice Competence | .12 | −.15+ | .10 | −.07 | −.15** | −.09 | −.04 | −.05 | .15** | .17** | -- | ||||||

| Wave 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| 12. Acceptance | .61*** | −.47*** | .56*** | .04 | −.14 | .03 | .12 | .07 | .03 | .13 | .34*** | -- | |||||

| 13. Rejection | −.61*** | .70*** | −.40*** | −.11 | .11 | −.02 | −.05 | −.01 | −.10 | −.13 | −.30*** | -.60*** | -- | ||||

| 14. Communication | .56** | −.42*** | .67*** | .00 | −.06 | −.05 | .06 | −.01 | −.06 | .07 | .23** | .83*** | −.50*** | -- | |||

| 15. Internalizing | −.01 | −.08 | −.10 | .66*** | .41*** | .07 | .05 | .08 | .08 | −.08 | −.21*** | −.03 | −.10 | −.03 | -- | ||

| 16. Externalizing | −.05 | .11 | −.03 | .47*** | .78*** | .03 | .03 | .04 | −.02 | −.15** | −.24*** | −.10 | .06 | −.01 | .56*** | -- | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Total Sample | M | 4.1 | 1.8 | 4.1 | 10.5 | 11.7 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.5 | 61.2 | 71.2 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 1.7 | 4.1 | 8.3 | 9.5 |

| SD | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 8.0 | 8.5 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 6.7 | 26.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 7.3 | 7.8 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Fathers | M | 4.0 | 1.7 | 3.9 | 9.1 | 10.4 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 3.5 | 60.0 | 64.3 | 3.2 | 4.0 | 1.6 | 4.0 | 7.5 | 8.9 |

| SD | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 8.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 7.2 | 31.4 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 7.5 | 8.0 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Mothers | M | 4.1 | 1.8 | 4.2 | 11.6 | 12.8 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 62.3 | 65.8 | 3.2 | 4.1 | 1.7 | 4.2 | 8.9 | 9.9 |

| SD | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 8.7 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 6.2 | 30.7 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 7.0 | 7.7 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Mean Differences by Gender | t(144) = −1.0 | t(144) = −1.2 | t(144) = −2.1* | t(359.9) = −3.1** | t(362) = −2.7** | t(312.5) = −5.4*** | t(363) = −3.5*** | t(312.1) = −0.9 | t(363) = −5.4*** | t(363) = −0.5 | t(306) = −0.0 | t(88.2) = −0.4 | t(120) = −1.8+ | t(75.8) = −0.7 | t(303) = −1.8+ | t(302) = −1.1 | |

Notes:

p≤.001;

p≤.01;

p≤.05;

p≤.1

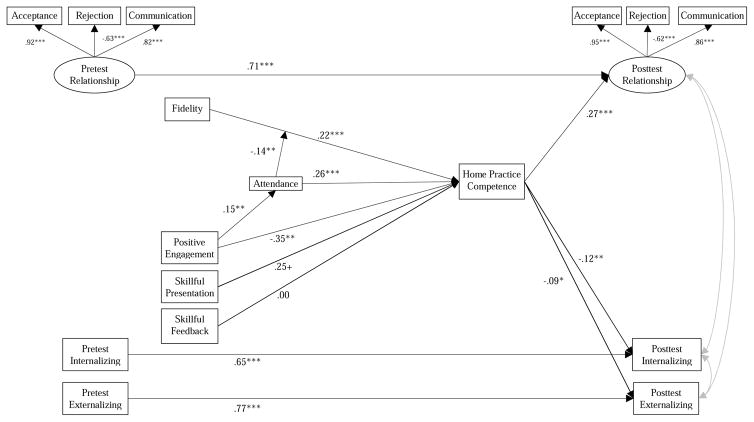

Test of the Theoretical Model

Results of the model testing the cascading effects of implementation on parenting and child mental health are presented in Figure 3. The loadings for the three indicators of the positive relationship construct (i.e., acceptance, communication, and rejection) were above B = .50, p ≤ .001. A path was added between positive engagement and home practice competence based on modification indices. The model demonstrated adequate fit. Standardized Bs demonstrated that fidelity and attendance were positively associated with home practice competence. There was also a trend for an association between skillful presentation and home practice competence. Positive engagement was associated with higher levels of attendance, but unexpectedly, with lower levels of home practice competence. Facilitator ratings of parents’ home practice competence were associated with improvements in child report of relationship quality, and reductions in parent report of child internalizing and externalizing.

Figure 3.

Test of a Theoretical Cascade Model of Implementation

Notes. X2(91) = 125.00, p=.05; RMSEA=.03(.02, .05); CFI=.97; SRMR =.07; ***p≤.001; **p≤.01; *p=.05; +p≤.1

Moderational Effects

Consistent with moderational hypotheses, home practice competence was significantly explained by fidelity (B = 5.04, t(304) = 3.14, p ≤ .001), attendance (B = 0.41, t(304) = 2.92, p = .004), and the fidelity x attendance interaction term (B = −5.06, t(304) = −2.53, p =.01). Figure 2 plots the simple slopes for the interaction at the mean level of attendance, one standard deviation above, and one standard deviation below. At the mean attendance [t(304) = 2.56, p = .01] and at one standard deviation below [t(304) = 3.74, p ≤ .001], fidelity had an influence on home practice competence, whereas fidelity had no effect at higher levels of attendance [t(304) = 0.09, p = .93].

Figure 2.

Fidelity of Relationship Skills Activities on Home Practice Competence of by Number of Sessions Attended

Mediational Effects

Mediation analyses demonstrated support for the hypothesized pathways between facilitator delivery, participant responsiveness, and improvements in parent-child relationship quality and child mental health problems. Specifically, there was a significant indirect effect from positive engagement to attendance to home practice competence (B= .04; 95%CI: .01, .08). There was also a significant indirect effect from fidelity to home practice competence to parent-child relationship quality (B=.06; 95%CI: 0.02, .11) and from fidelity to home practice competence to reductions in parent report of child internalizing (B= −.03; 95%CI: -.05, –.01) and externalizing (B= −.02; 95%CI: -.04, -.003).

Gender Effects

A series of Wald Tests on all path coefficients in the model demonstrated minimal differences by gender. The negative path from positive engagement to home practice competence noted above was significant only for fathers [Wald(1) = 11.15, p ≤ .001; fathers = −.61, p ≤ .001; Bmothers = .35, p = .15]. The path coefficient from skillful feedback to home practice competence was significant only for mothers [Wald(1) = 4.06, p = .04; Bfathers = .17, p = .24; Bmothers = −.16, p = .04]. No other significant differences were found.

Alternative Models

To examine the robustness of effects, we repeated these analyses in several ways and found consistent results with one exception noted below. To address possible multicollinearity effects due to high correlations between quality indicators, we repeated the model dropping skillful presentation and skillful feedback; results were consistent, including the relations between positive engagement and attendance and home practice competence. To address the different sample sizes for parent and child report, we tested effects on parenting and child mental health in separate models; results were consistent. To address possible issues with the 28 families that had two parents attending the program, we repeated the analyses without those 28 families; again results were consistent. Finally, to address the fact that we only have child report of parenting for children who were old enough to provide data (ages 9+) and to determine possible effects of reporter, we tested the model with parent report of their own parenting and child report of their own mental health. Results for parent report were consistent, however, the links between home practice competence and child report of their own mental health were not significant for internalizing or externalizing.

Discussion

The current study was guided by a theoretical cascade model of implementation (Berkel, et al., 2011), in which program facilitator delivery influences participant responsiveness, which in turn leads to improvements in targeted program outcomes (see Figure 1). Results demonstrated support for this model in that an indicator of quality (i.e., positive engagement) predicted parent attendance and attendance moderated the effects of fidelity on parent competence in practicing program skills at home. Home practice competence, in turn, explained increases in parent-child relationship quality and decreases in internalizing and externalizing problems. The significance of each of these findings as well as limitations of the study and directions for future research are discussed.

Importance of Home Practice

In previous work (Berkel, et al., 2016), home practice competence was identified as an important component of participant responsiveness that accounts for improvements in parenting. The current study extended previous findings to demonstrate a direct link between home practice competence and reductions in children’s mental health problems following divorce. Particularly noteworthy were the findings that each unit increase in home practice competence cut the risk of borderline internalizing diagnoses by half and externalizing by one third. Given the negative effects of divorce on child mental health and the current widespread exposure to divorce, ensuring parents’ competence in home practice skills has important implications for achieving public health impact.

Home practice competence was a significant mediator of the effects of fidelity and of quality on improvements in parenting and children’s mental health problems. Given extensive evidence from other evidence-based programs that fidelity and quality predict outcomes (Durlak & DuPre, 2008), the finding that these effects are mediated by home practice competence in this program may have broad implications for effective implementation of other parenting programs. Because home practice competence is a relatively feasible indicator of implementation to collect, it could be used as a practical method to identify groups that need additional supervision or technical assistance when programs are delivered in community settings.

Fidelity and Home Practice Competence

As hypothesized, fidelity and attendance were both positively associated with improvements in program outcomes, mediated by home practice competence. This finding goes beyond previous direct effects analyses (Durlak & DuPre, 2008) to contribute to our understanding of how programs work. Further, also as hypothesized, there was an interaction showing that fidelity was more predictive of home practice competence for parents who attended fewer sessions. This apparent inconsistency with a previous study where higher levels of both fidelity and attendance led to better outcomes (Berkel, et al., 2013) may be at least partially explained by the fact that the current study excluded parents who had never attended. Further, NBP presents information multiple times, especially during the Home Practice Review activities, in which skills are processed cumulatively over the 10 weeks. Higher attending parents are exposed to multiple opportunities to learn and reinforce program skills. However, parents who attend fewer sessions have fewer opportunities to learn the skills, so that fidelity in those cases may be more critical in enabling them to implement the skills well. This has implications for curriculum design, emphasizing the need to reinforce content throughout the program. Noteworthy is that program effects were still found with lower fidelity ratings (~60%), suggesting evidence for the robustness of the program.

Differential Effects of Quality by Parent Gender

Given that limited research has been conducted on how dimensions of implementation interrelate to influence program outcomes and that evidence based parenting programs have typically focused on mothers, we know little about possible differences in how these mechanisms may work across gender. Effects of fidelity were equivalent, indicating support for the notion that adaptations to the program were sufficient to address the needs and cultural context of divorced fathers. Differences across quality subscales were found, however. As predicted, positive engagement was indirectly associated with home practice competence through increases in parent attendance for both mothers and fathers. However, an unexpected negative effect for fathers only was found between positive engagement and home practice competence. While we did not code for content outside of what was scripted in the manual, general impressions were that in some of the father groups, positive engagement strategies of the facilitators were interpreted as invitations for off-topic conversations that diverted time from teaching and processing of program skills. This emphasizes the importance of coding unplanned, additive adaptations during program delivery (Barrera, Berkel, & Castro, 2017). Finally, skillful feedback is an interesting subscale given that many of the items depend on how well the skills are working: if things are going well, there is no need to problem solve or provide additional guidance. Based on mothers’ higher reports of child mental health problems, it may be that facilitators may have been responding to mothers’ need for additional support.

Limitations and Future Directions

A limitation of the current study was that only five of the activities coded addressed the development of positive parent-child relationship quality. This included one didactic activity, three home practice review activities, and one skills practice activity, so there were few opportunities to assess skillful presentation or skillful feedback in the activities where these dimensions are thought to be most salient. Future studies using more extensive coding of different program activities will allow for a more powerful test of whether different aspects of quality are predictive of home practice competence. More extensive coding would also permit an examination relations for other program skills, including discipline and shielding children from interparental conflict, which may also influence child mental health. Finally, other dimensions, such as unplanned, additive adaptations (Barrera, et al., 2017) and the nature of parent interactions (Coatsworth, Duncan, Pantin, & Szapocznik, 2006), would also likely have effects on parent responsiveness, and should be included in future studies.

A second measurement issue was that obtaining interrater reliability assessments for facilitator ratings of home practice competence would be highly infeasible, requiring a secondary coder to review home practice worksheets and attend skills practice and home practice review activities, as well as facilitator attendance at training and calibration meetings. On the other hand, we believe a particular strength of this research is that we have successfully validated an implementation measure that 1) has convergent reliability with parents’ home practice self-ratings, 2) is linked with variability in the delivery of the program, 3) predicts improvement in parenting and child mental health outcomes, and 4) is feasible to collect in community settings.

A final limitation that bears noting is that because measures were averaged across sessions, a lack of temporal precedence means that we cannot be sure about the direction of effects. It is plausible that when parents struggle with home practice, it is more difficult for facilitators to present the session’s content or that when attendance is high, facilitators engage in more rapport-building behaviors with parents. Future research using a cross-lagged approach may shed additional light on these questions. Further, there may also be developmental processes where the relevance of certain aspects of delivery vary over time. For example, whereas positive engagement may be more relevant in early sessions to build rapport with parents and retain them in services, skillful feedback may become more important in later sessions where more difficult discipline and conflict skills are covered. Future work should consider the structure and the timing of the activity in determining the effects of skillful presentation or skillful feedback on home practice.

Conclusions

In summary, results of this study go beyond prior direct effects research (Durlak & DuPre, 2008) to support a theoretical implementation cascade model laying out the mechanisms by which multiple dimensions of provider delivery and participant responsiveness influence outcomes in evidence-based parenting programs. We found that fidelity to the curriculum and three elements of quality (positive engagement, skillful presentation, and skillful feedback) were positively correlated, but functioned differently to explain attendance and home practice competence. The study extended our previous work (Berkel, et al., 2016) by establishing a direct link between home practice quality and child mental health outcomes, above and beyond improvements in parenting. This was the first study to examine the impact of fidelity and multiple components of process quality on home practice of program skills and program outcomes. We found support for hypotheses that rapport building strategies (i.e., facilitators’ use of positive engagement) were associated with higher levels of attendance. Attendance and fidelity were associated with home practice competence, which in turn accounted for improvements in both parenting and child mental health. With minor exceptions, these mechanisms functioned equivalently across parent gender.

An understanding of this implementation cascade is important both from a theoretical perspective to understand how programs work (West, et al., 1993), and for identifying targets for implementation support when programs are delivered in community settings. Specifically, attendance and home practice quality are valid predictors of program outcomes and are relatively efficient to collect. Fidelity and quality data, on the other hand, require independent observations, which are difficult for community agencies (Schoenwald, et al., 2011). Evidence from this study supports the development of a staged, multicomponent monitoring approach in which attendance and home practice competence are monitored regularly, supplemented by assessment of provider delivery when participant responsiveness falls below a defined threshold. Such a system may serve competing needs for feasible and valid methods to monitor implementation of evidence-based programs and promote public health impact.

Acknowledgments

Funding. Support was provided by R01DA026874 (Sandler), R01DA033991 (Berkel & Mauricio), and competitive funding from the Center for Prevention Implementation Methodology (Ce-PIM), P30-DA027828 (Brown/Berkel), and Diversity Supplement R01DA033991-03S1 (Berkel/Gallo).

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards:

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. Sandler and Wolchik are the developers of the NBP and have an LLC that trains providers to deliver the program. Remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of Arizona State University’s IRB and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Achenbach TM, Edelbrock CS. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Behavior Profile. Stowe: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes H, Olson DH. Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale. In: Olson DH, McCubbin HI, Barnes H, Larsen A, Muxen M, Wilson M, editors. Family inventories: Inventories used in a national survey of families across the family life cycle. St. Paul, MN: Family Social Science, University of Minnesota; 1982. pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Barrera M, Berkel C, Castro FG. Directions for the advancement of culturally adapted preventive interventions: Local adaptations, engagement, and sustainability. Prevention Science. 2017;18:640–648. doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0705-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Mauricio AM, Schoenfelder E, Sandler IN. Putting the pieces together: An integrated model of program implementation. Prevention Science. 2011;12:23–33. doi: 10.1007/s11121-010-0186-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Murry VM, Roulston KJ, Brody GH. Understanding the art and science of implementation in the SAAF efficacy trial. Health Education. 2013;113:297–323. doi: 10.1108/09654281311329240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Brown CH, Gallo CG, Chiapa A, Mauricio AM, Jones S. “Home Practice Is the Program:” Parents' practice of program skills as predictors of outcomes in the New Beginnings Program effectiveness trial. Prevention Science. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s11121-016-0738-0. online first. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti DV. Guidelines, criteria, and rules of thumb for evaluating normed and standardized assessment instruments in psychology. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:284–290. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke AT, Marshall SA, Mautone JA, Soffer SL, Jones HA, Costigan TE, Patterson A, Jawad AF, Power TJ. Parent attendance and homework adherence predict response to a family–school intervention for children with ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2015;44:58–67. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.794697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coatsworth JD, Duncan LG, Pantin H, Szapocznik J. Retaining ethnic minority parents in a preventive intervention: The quality of group process. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2006;27:367–389. doi: 10.1007/s10935-006-0043-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cusack J, Deane FP, Wilson CJ, Ciarrochi J. Emotional expression, perceptions of therapy, and help-seeking intentions in men attending therapy services. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2006;7:69–82. [Google Scholar]

- Dane AV, Schneider BH. Program integrity in primary and early secondary prevention: Are implementation effects out of control? Clinical Psychology Review. 1998;18:23–45. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(97)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak J, DuPre E. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;41:327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eames C, Daley D, Hutchings J, Hughes JC, Jones K, Martin P, Bywater T. The Leader Observation Tool: A process skills treatment fidelity measure for the Incredible Years parenting programme. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2008;34:391–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2008.00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgatch MS, Patterson GR, DeGarmo DS. Evaluating fidelity: Predictive validity for a measure of competent adherence to the Oregon model of parent management training. Behavior Therapy. 2005;36:3–13. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7894(05)80049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18:233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson D, Kumpfer K, Polizzi-Fox D, Wilson D, Puryear V, Beatty P, Vilmenay M. The Strengthening Washington D.C. Families Project: A randomized effectiveness trial of family-based prevention. Prevention Science. 2006;7:57–74. doi: 10.1007/s11121-005-0017-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Liddle HA, Rowe C. Treatment adherence process research in family therapy: A rationale and some practical guidelines. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 1996;33:332–345. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L-t, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kazantzis N, Deane FP, Ronan KR. Assessing compliance with homework assignments: Review and recommendations for clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2004;60:627–641. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lochman JE, Boxmeyer C, Powell N, Qu L, Wells K, Windle M. Dissemination of the coping power program: Importance of intensity of counselor training. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:397–409. doi: 10.1037/a0014514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Mplus, Version 7.1. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- NRC/IOM. Preventing Mental, Emotional, and Behavioral Disorders among Young People: Progress and Possibilities. Washington, D.C: NRC/IOM; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orrell-Valente JK, Pinderhughes EE, Valente E, Laird RD. If it's offered, will they come? Influences on parents' participation in a community-based conduct problems prevention program. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1999;27:753–783. doi: 10.1023/a:1022258525075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs NR, Elfenbaum P, Pentz MA. Parent program component analysis in a drug abuse prevention trial. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2006;39:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ros R, Hernandez J, Graziano PA, Bagner DM. Parent training for children with or at risk for developmental delay: The role of parental homework completion. Behavior Therapy. 2016;47:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Gunn H, Mazza G, Tein J-Y, Wolchik SA, Berkel C, Jones S, Porter MM. Effects of a program to promote high quality parenting by divorced and separated fathers. Prevention Science, online first. 2017:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11121-017-0841-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, Berkel C, Jones S, Mauricio AM, Tein J-Y, Winslow E. Effectiveness trial of the New Beginnings Program (NBP) for divorcing and separating parents: Translation from an experimental prototype to an evidence-based community service. In: Israelashvili M, Romano JL, editors. Cambridge Handbook of International Prevention Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer ES. Children's report of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development. 1965;36:413–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfelder E, Sandler IN, Millsap RE, Wolchik SA, Berkel C, Ayers TS. Responsiveness to the Family Bereavement Program: What predicts responsiveness? What does responsiveness predict? Prevention Science. 2012;14:545–556. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0337-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Garland AF, Chapman JE, Frazier SL, Sheidow AJ, Southam-Gerow MA. Toward the effective and efficient measurement of implementation fidelity. Administration & Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research. 2011;38:32–43. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0321-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper D. Interaction v.1.7. 2006–2011 Retrieved from danielsoper.com/Interaction/free.aspx.

- Stevenson MM, Braver SL, Ellman IM, Votruba AM. Fathers, divorce, and child custody. In: Cabrera NJ, Tamis-LeMonda CS, editors. Handbook of father involvement: Multidisciplinary perspectives. 2. NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis; 2013. pp. 379–396. [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, MacKinnon DP. RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods. 2011;43:692–700. doi: 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triemstra KT, Niec LN, Peer SO, Christian-Brandt AS. The influence of conventional masculine gender role norms on parental attitudes toward seeking psychological services for children. Psychology of Men & Masculinity 2016 [Google Scholar]

- West SG, Aiken LS, Todd M. Probing the effects of individual components in multiple component prevention programs. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1993;21:571–605. doi: 10.1007/BF00942173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik S, Sandler I, Weiss L, Winslow E. New Beginnings: An empirically-based program to help divorced mothers promote resilience in their children. In: Briesmeister JM, Schaefer CE, editors. Handbook of parent training: Helping parents prevent and solve problem behaviors. 3. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley; 2007. pp. 25–62. [Google Scholar]