Abstract

Objective

An association between childhood trauma and adult health outcomes has been widely reported, but little is known about the developmental pathways through which childhood trauma influences adult cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Methods

Hypotheses were tested with a sample of 405 African Americans from the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS). Path modeling was used to test our theoretical model.

Results

Replicating prior research, exposure to childhood trauma was associated positively with increases in symptoms of CVD risk across young adulthood even after controlling for a variety of health-related and health behavior covariates. Further, the association of childhood trauma with CVD risk was mediated by early pubertal maturation. There were no gender differences in the magnitude of this effect.

Conclusion

Our findings support an evolutionary-development perspective (Belsky & Shalev, 2016) suggesting that early adverse life experiences lead to early biologically embedded changes reflected in early physical maturation and that these early changes predict later negative adult health outcomes. The results imply that early pubertal maturation is a precursor to vulnerability to long term health problems. From an intervention standpoint, identifying such developmental pathways may help inform future health-promoting interventions.

Keywords: Childhood trauma, early pubertal maturation, cardiovascular risk, evolutionary-development perspective, African Americans

Children raised in adverse environments are at greater risk for a range of health problems in adulthood (Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011). Indeed, a recent meta-analysis by Basu and colleagues (2017) reported that childhood trauma and maltreatment have been strongly associated with the development of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and type II diabetes in adulthood, even after controlling for sociodemographic and health risk behaviors. In addition, this is particularly relevant for African Americans who are at increased risk for childhood maltreatment (Sedlak, et al., 2010) due to elevated contextual stressors and who experience a greater prevalence of CVD (Thomas et al., 2005). Given these findings, understanding the long-term effects of childhood trauma on CVD risk among African Americans is of considerable interest and importance.

Puberty is the sensitive transitional period between childhood and adulthood, during which a growth spurt occurs, secondary sexual characteristics appear, fertility begins, and marked changes in the neuroendocrine system unfold; however, not all individuals go through maturation at the same time. Researchers recognize that the early environment plays a key role in the timing of pubertal development (Belsky, 2012; Ellis, et al., 2012). When people experience childhood trauma or adversity, the timing of pubertal maturation is often accelerated (Belsky & Shalev, 2016). Further, recent studies (Day et al., 2015) have suggested that the early onset of pubertal development is also related to higher risks of CVD.

In response to this connection, Belsky extended his earlier work on human reproductive strategies (Belsky, 2012) and proposed an evolutionary-development model (Belsky et al., 2015, 2016) whereby early adversity is related to pubertal development which, in turn, is associated with poor health and accelerated biological aging. Similar to life history theory (Ellis et al., 2012), they argued that earlier pubertal development, relative to same-age peers, is part of the biological calibration that occurs in preparation for a future that, based upon adverse childhood experiences, is expected to be harsh and unpredictable. Thus the link between childhood trauma and pubertal development is seen to be “adaptive.” Organisms are expected to trade-off increased risk for future negative health outcomes in favor of early assumption of adult roles and possibly early successful reproduction; with early puberty being both a marker of this accelerated development, and of biological changes that portend early onset of chronic illnesses such as CVD. Based on this theoretical perspective, we test the hypothesis that pubertal development mediates the association between childhood trauma and adult CVD risk and predicts increases in CVD risk across young adulthood net of health behavior and concurrent stressors.

Although the effects of early trauma on early pubertal development have been shown across a variety of domains (e.g., Bale & Epperson, 2017; Sandman, Glynn & Davis, 2013), results are mixed regarding whether the effects on health are conditional on gender (Bluher et al., 2013; Sun & Schubert, 2009). The only study (Belsky et al., 2015) examining associations among early adversity, pubertal development, and self-reported health focused only on girls. Therefore we explore, but do not specifically predict, that the mediating effect of pubertal maturation will be different in magnitude for males and females.

Methods

Participants

We tested this hypothesis using data from the seven waves of the Family and Community Health Study (FACHS) (Beach et al., 2017). FACHS is a longitudinal study of several hundred African American families that was initiated in 1997. The protocol and all study procedures were approved by the University of Georgia Institutional Review Board. At the first wave (1997–1998), the FACHS sample consists of 889 African American fifth-grade children. The mean ages were 10.56 years (SD = .631; range 9–13). The second, third, fourth, fifth, and sixth waves of data were collected in 1999–2000, 2001–2002, 2004–2005, 2007–2008, and 2011–2012 to capture information when the target children were mean ages 12.5, 15.7, 18.8, 21.6, and 23.6, respectively. In 2014–2015 a Wave 7 of data collection was completed that included blood draws. The mean ages were 28.79 years (SD = .848; range 27–31). Given the logistics of scheduling home visits by phlebotomists, only members of the sample residing in Georgia, Iowa, or a contiguous state were identified as eligible. After also excluding persons who were deceased, incarcerated, or otherwise unreachable, we were left with a pool of 545 individuals, 470 (86%) of whom agreed to be interviewed and to provide blood. In the current study, analyses are based on the 405 respondents (159 men and 246 women) who provided blood samples at age 29 and had provided data on all study measures from ages 10 to 29. Comparisons of this subsample with those who were not included in the analysis did not reveal any significant differences with regard to education, income, family poverty, single-parent family, healthy diet, and exercise.

Measures

Childhood trauma was assessed retrospectively by the 23-item short form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ-SF; Bernstein, Stein, Newcomb, Walker, 2003). The instrument asks respondents to report (1 = yes, 0 = no) whether they experienced trauma before the age of 10 years (e.g., prior to age 10, would you say... I was punished with a belt, a board, a cord, or some other hard object; People in my family hit me so hard that it left me with bruises or marks). Coefficient alpha for this scale was .78.

Pubertal maturation was assessed at ages 10 and 12 using the Pubertal Development Scale (PDS) (Petersen et al., 1988). On a scale ranging from 1 (have not begun) to 4 (development completed), the children indicated the extent to which they had experienced pubertal growth in several domains. Children of both genders were asked to report on their body hair development, growth spurt, and skin changes. Boys were asked to rate their facial hair development and voice change, and girls were asked to report on breast development and menarche. The scale yields a mean score from 1 (puberty has not begun) to 4 (puberty is complete) at ages 10 and 12. Coefficient alpha for both males and females were above .70.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk was assessed by combining information from 3 biomarkers measured at age 29. (a) An individual’s body mass index (BMI) score is calculated by weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Mean BMI was 31.40 (SD = 9.45). (b) Resting diastolic and systolic blood pressure (BP) was monitored with Dinamap Pro 100 while the participants sat reading quietly. Three readings were taken every 2 min, and the average of the last two readings was used as the resting index. Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) is calculated according to the following formula: [(systolic BP) + (2 × diastolic BP)]/3. Mean MAP was 93.52 (SD = 11.54). (c) Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is an indicator of average blood glucose concentrations over the preceding 2 to 3 months. Mean HbA1c was 5.34 (SD = .78). Given that these three biomarkers are characterized by a skewed distribution, we applied a log transformation to normalize the distribution. Finally, consistent with prior work (Kimbro et al., 2012), CVD risk was calculated by summing the standardized log-transformed scores of BMI, MAP, and HbA1c. To avoid overestimation, we also controlled for CVD risk at age 18. Only the first two of the three biomarkers were available in the Wave 4 instrument. Thus, CVD risk at age 18 was the summation of the log of BMI (mean before log transformation = 26.97, SD = 7.13) and the log of MAP (mean before log transformation = 86.23, SD = 11.06).

Covariates

To account for measures that could provide plausible rival explanations, all analyses statistically controlled for health-related covariates at Waves 1 and 7. Gender was controlled in all analyses and was examined in exploratory analyses as a potential moderator of response. At Wave 1, covariates included childhood BMI (CDC: BMI calculator for Child and Teen. https://nccd.cdc.gov/dnpabmi/Calculator.aspx), family poverty (US government criteria: an income-to-needs ratio ≤ 1.5) and single-parent family structure (yes = 1). At Wave 7, demographic control variables included level of education, weekly income (in dollars), health insurance (yes = 1) and married or cohabiting with a romantic partner (yes = 1). Participants reported the number of occasions (0 = 0 times, 6 = 40 or more times) during the past month on which they had smoked cigarettes, had a drink of alcohol, or used marijuana. A composite measure of substance use was formed by standardizing and averaging the three scores. Healthy diet was assessed using two items that asked about frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption during the previous 7 days. Responses ranged from 1 (none) to 6 (more than once every day) and were averaged to form the healthy diet variable. Exercise was measured with two items (e.g., On how many of the past 7 days did you exercise or participate in physical activity for at least 30 min that made you breathe hard such as running or riding a bicycle hard?) The response categories ranged from 1 (0 days) to 5 (all 7 days). Scores on the two items were averaged to form the exercise measure.

Analytic strategy

We used path modeling in Mplus 8 to test our model. To control for previous time effects, pubertal maturation at age 10 and CVD risk at age 18 were controlled in the model. To assess goodness-of-fit of the model, we used Steiger’s Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA < .05) and the comparative fit index (CFI > .90). The 95% confidence interval estimated with bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrapping with 1,000 resamples was used to assess the significance of hypothesized indirect effects. Finally, we tested for differences between the models for females and males using the multiple group analysis option in Mplus.

Results

The zero order correlations among the study variables are presented in Table 1. As expected, there was a significant association between childhood trauma and pubertal maturation (r = .124). Childhood trauma (r = .113) and pubertal maturation (r = .153) were significantly associated with CVD risk. The control variables showed little association with CVD risk. The exception was childhood BMI and exercise, for which there was a significant association with CVD risk. And, gender was significantly related to pubertal maturation.

Table 1.

Correlations, Means, and Standard Deviations among the Study Variables (n = 405)

| Variable or statistic | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Childhood trauma (Prior to age 10) | ── | |||||||||||||

| 2. Pubertal maturation (Age 12) | .124* | ── | ||||||||||||

| 3. Cardiovascular risk (Age 29) | .113* | .153** | ── | |||||||||||

| 4. Males | −.049 | −.500** | −.016 | ── | ||||||||||

| 5. Childhood BMI | .021 | .141** | .274** | .121* | ── | |||||||||

| 6. Family poverty (Age 10) | .010 | −.087† | .040 | −.021 | −.114* | ── | ||||||||

| 7. Single family (Age 10) | .076 | .038 | .079 | −.084† | −.074 | .364** | ── | |||||||

| 8. Substance use (Age 29) | .277** | .019 | −.028 | .112* | .047 | −.061 | −.017 | ── | ||||||

| 9. Healthy diet (Age 29) | .076 | .136** | .008 | −.187** | .064 | .013 | −.001 | −.023 | ── | |||||

| 10. Exercise (Age 29) | .089† | −.047 | −.139** | .175** | −.043 | −.014 | −.020 | .141** | .194** | ── | ||||

| 11. Health insurance (Age 29) | .085† | .143** | .013 | −.142** | .050 | −.075 | −.016 | −.076 | .151** | .014 | ── | |||

| 12. Education (Age 29) | .133** | .163** | .015 | −.079 | .045 | −.167** | −.053 | .022 | .162** | .109* | .191** | ── | ||

| 13. Income (Age 29) | .154** | .079 | −.017 | .082 | .064 | −.133** | −.017 | .047 | .048 | .131** | .180** | .298** | ── | |

| 14. Married or cohabiting (Age 29) | .029 | .043 | .032 | .027 | −.017 | .015 | .054 | .050 | .003 | −.001 | .056 | .025 | −.029 | ── |

| Mean | 3.259 | 2.610 | .000 | .390 | 22.340 | .573 | .511 | −.017 | 6.714 | 4.958 | .822 | 13.079 | 441.03 | .262 |

| SD | 3.020 | .649 | 2.029 | .489 | 6.424 | .495 | .500 | .695 | 2.421 | 2.277 | .383 | 1.713 | 337.62 | .440 |

p ≤ .10,

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01 (two-tailed tests).

We first tested a baseline model that assessed the direct effect of childhood trauma on adult CVD risk. As hypothesized, childhood trauma was a significant predictor of adult CVD risk (β = .101, p = .032), even after controlling for covariates and CVD risk at age 18, supporting our hypothesis and previous findings.

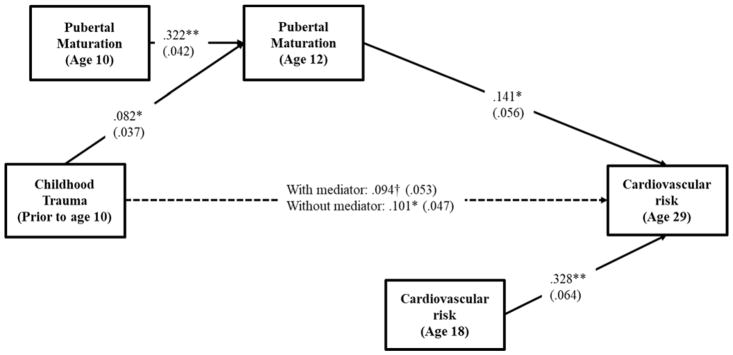

To address the hypothesized mediating effect, pubertal maturation at age 12 was added as a mediator. The results of this analysis appear in Figure 1. The various fit indices suggested that the proposed model provided a good fit to the data ( , p = .048; CFI = .967; RMSEA = .043). As can be seen in figure 1, childhood trauma was associated with pubertal maturation (β = .082, p = .029), which, in turn, was associated with adult CVD risk (β = .141, p = .013). Using a bootstrapping technique with 1,000 replications indicated that the mediating effect of childhood trauma on adult CVD risk through pubertal maturation was significant (indirect effect = .012, 95% CI [.001, .031]) and accounted for about 11.43 percent of the total variance. Accordingly, the findings show strong support for the study hypotheses.

Figure 1.

Effects of childhood trauma on cardiovascular risk through pubertal maturation

Note. Chi-square = 21.164, df = 12, p = .048; CFI = .967; RMSEA = .043. Values are standardized parameter estimates and standard errors are in parentheses. Males, childhood BMI, family poverty, single-parent family, substance use, healthy diet, exercise, health insurance, education, income and married/cohabiting are controlled in these analyses. Changes in pubertal maturation between ages 10 and 12 is calculated by regressing pubertal maturation at age 12 on pubertal maturation at age 10. CVD risk at age 18 is controlled in the model to focus on change in CVD risk between ages 18 and 29.

**p ≤ .01; *p ≤ .05; †p ≤ .10 (two-tailed tests), n = 405.

Next, we repeated the analysis in Figure 1, for each component of CVD risk to determine, for heuristic purposes, which components of risk were most robustly mediated by pubertal maturation. Significant indirect effects appeared for BMI (indirect effect = .011, 95% CI [.001, .029]) and MAP pressure (indirect effect = .010, 95% CI [.001, .028]). The indirect effect of HbA1c, however, only approached significance (indirect effect = .008, 90% CI [.001, .025]).

Finally, multiple group analyses were conducted to test for differences between the models for women and men. We compared a model that constrained all paths to be equal between women and men with an alternative model that allowed them to differ. To determine which paths were different, we freed one path in the constrained model at a time and compared it with the constrained model’s chi-square with one degree of freedom. No paths were significantly different for women versus men (childhood trauma → pubertal maturation: , p = .532; pubertal maturation → CVD risk: , p = .950), indicating no gender difference in the effects of childhood trauma on adult CVD risk through pubertal development.

Discussion

Compared to members of other racial groups, African Americans experience more traumatic events in childhood and more CVD in adulthood (Basu et al., 2017). Despite their increased risk for these outcomes, very little is known about the developmental pathways through which childhood adversity may become biologically embedded and so influence the risk of CVD in adulthood for African Americans. Using a longitudinal sample of African Americans, the current study indicated that (a) childhood trauma was associated positively with adult CVD risk; (b) the association remained significant when health-related covariates were controlled in the analyses; and (c) the association between childhood trauma and CVD risk was mediated by timing of pubertal maturation. Our findings challenge the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease (DOHaD) model which posits non-optimal growth in response to childhood trauma, and resulting long-term health consequences. By contrast, the findings are consistent with an evolutionary-development perspective (Belsky & Shalev, 2016) that early pubertal development in response to childhood trauma may result in more rapid transition to adulthood, allowing individuals to become ready to assume adult roles at an earlier age, but at a long-term health cost. The pattern of results for specific symptoms on our CVD risk index suggested that pubertal maturation is a mediator of effects of childhood trauma on BMI and blood pressure in young adulthood, implying that early pubertal maturation is a precursor to vulnerability to long term health problems. However, effects on HbA1c may be less robust or perhaps slower to emerge in adulthood.

Finally, our findings also suggest that there were no gender differences in the associations among childhood trauma, pubertal maturation, and CVD. This is not surprising in the absence of compelling reasons to expect sex effects for this variable. Indeed, prior work has shown that early maturation is associated with BMI, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease in both women and men (Sun & Schubert, 2009). However, given gender differences in other domains (e.g., Bale & Epperson, 2017; Sandman, Glynn & Davis, 2013), it is also important that our results be replicated with other samples and other dependent variables.

Although a major strength of the present study was its use of multiple sources of data that combined individual- and biological-level measures, it was not without shortcomings. First, our sample was all African American might be viewed as a strength as well as a limitation. Given that differences in discrimination may condition response to trauma and adversity, assessments of childhood trauma may not be fully comparable across ethnic groups even when using similar items. Accordingly, a focus on a single ethnic group seems appropriate for examination of our models. However, the results obtained in the present study clearly need to be replicated from other ethnic groups. Second, we have no prospective measures of early childhood exposure to adverse environments (prior to age 10). Thus, childhood trauma was assessed by a retrospective questionnaire. It is possible that a retrospective measure led to relatively small effect sizes in the current study. While the retrospective childhood trauma questionnaire (CTQ) has been shown to have high reliability and validity, future studies should replicate the current study with a non-retrospective measure.

Despite limitations and the need for future replication, our study provides insights for better understanding the link between childhood trauma and cardiovascular risk in adulthood. The resulting model supports using pubertal timing as a window on biological embedding processes, providing an evolutionary-development perspective on the emergence of long-term health outcomes. From an intervention standpoint, identifying such developmental pathways may help inform future health-promoting interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award Number R01 HL8045 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Award Number R01 HD080749 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, and P30 DA027827 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declarations of Interest: None.

Contributor Information

Man-Kit Lei, Center for Family Research and Department of Sociology, University of Georgia.

Steven R.H. Beach, Center for Family Research and Department of Psychology, University of Georgia

Ronald L. Simons, Department of Sociology, University of Georgia

References

- Bale TL, Epperson CN. Sex as a biological variable: who, what, when, why and how. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;42:386–396. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, McLaughlin KA, Misra S, Koenen KC. Childhood maltreatment and health impact: the examples of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2017;24:125–139. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach SRH, Lei MK, Simons RL, Barr AB, Simons LG, Ehrlich K, Brody GH, Philibert RA. When inflammation and depression go together: The longitudinal effects of parent-child relationships. Development and Psychopathology. 2017;29:957–969. doi: 10.1017/S0954579417001523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. The Development of Human Reproductive Strategies: Progress and Prospects. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2012;21:310–316. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Ruttle PL, Boyce WT, Armstrong JM, Essex MJ. Early trauma, elevated stress physiology, accelerated sexual maturation and poor health in female. Developmental Psychology. 2015;51:816–822. doi: 10.1037/dev0000017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Shalev I. Contextual trauma, telomere erosion, pubertal development, and health: Two models of accelerated aging, or one? Development and Psychopathology. 2016;28:1367–1383. doi: 10.1017/S0954579416000900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, … Zule W. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2003;27:169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bluher S, Molz E, Wiegand S, Otto KP, Sergeyev E, Tuschy S, … Holl RW. Body mass index, waist circumference, and waist-to-height ratio as predictors of cardiometabolic risk in childhood obesity depending on pubertal development. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2013;98:3384–3393. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day FR, Elks CE, Murray A, Ong KK, Perry JR. Puberty timing associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease and also diverse health outcomes in men and women: the UK Biobank study. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:11208. doi: 10.1038/srep11208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Del Giudice M, Dishion TJ, Figueredo AJ, Gray P, Griskevicius V, … Wilson DS. The evolutionary basis of risky adolescent behavior: Implications for science, policy, and practice. Developmental Psychology. 2012;48(3):598–623. doi: 10.1037/a0026220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbro LB, Steers WN, Mangione CM, Duru OK, Ettner SL. The association of depression and the cardiovascular risk factors of blood pressure, HbA1c, and body mass index among patients with diabetes: results from the translating research into action for diabetes study. International Journal of Endocrinology. 2012;2012:747460. doi: 10.1155/2012/747460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological stress in childhood and susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: moving toward a model of behavioral and biological mechanisms. Psychological Bulletin. 2011;137:959–997. doi: 10.1037/a0024768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1988;17:117–133. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandman CA, Glynn LM, Davis EP. Is there a viability-vulnerability tradeoff? Sex differences in fetal programming. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2013;75:327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak AJ, Mettenburg J, Basena M, Petta I, McPherson K, Greene A, Li S. Fourth national incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS–4): Report to congress, executive summary. Washington, DC: Department of HHS, Administration for Children and Families; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Sun SS, Schubert CM. Prolonged juvenile states and delay of cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors: the Fels Longitudinal study. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;155:S7e1–S7.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas AJ, Eberly LE, Davey Smith G, Neaton JD, Stamler J. Race/ethnicity, income, major risk factors, and cardiovascular disease mortality. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:1417–1423. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]