Abstract

Understanding how individual cells make fate decisions that lead to the faithful formation and homeostatic maintenance of tissues is a fundamental goal of contemporary developmental and stem cell biology. Seemingly uniform populations of stem cells and multipotent progenitors display a surprising degree of heterogeneity, primarily originating from the inherent stochastic nature of molecular processes underlying gene expression. Despite this heterogeneity, lineage decisions result in tissues of a defined size and with consistent proportions of differentiated cell types. Using the early mouse embryo as a model we review recent developments that have allowed the quantification of molecular inter-cellular heterogeneity during cell differentiation. We first discuss the relationship between these heterogeneities and developmental cellular potential. We then review recent theoretical approaches that formalize the mechanisms underlying fate decisions in the inner cell mass of the blastocyst stage embryo. These models build on our extensive knowledge of the genetic control of fate decisions in this system and will become essential tools for a rigorous understanding of the connection between noisy molecular processes and reproducible outcomes at the multicellular level. We conclude by suggesting that cell-to-cell communication provides a mechanism to exploit and buffer inter-cellular variability in a self-organized process that culminates in the reproducible formation of the mature mammalian blastocyst stage embryo that is ready for implantation into the maternal uterus.

Keywords: specification, blastocyst, heterogeneity, noise, modeling

Graphical abstract

Introduction

Understanding the mechanisms that control fate decisions within individual cells and their coordination across a population of cells is a fundamental aim of developmental and stem cell biology. Recent technical advances in single-cell analyses have revealed a surprising degree of heterogeneity in seemingly uniform populations of stem cells and multi-potent progenitors. This variability has many origins, most prominently the inherent stochastic nature of molecular processes underlying gene expression. Despite the resulting transcriptional noise and inter-cellular heterogeneity, lineage decisions in progenitor cells result in tissues with consistent proportions of differentiated cell types during development and homoeostasis. Thus, a key challenge is to understand how the structure of gene regulatory networks connects stochastic behavior at the single cell level with reproducible cell fate decisions across populations.

The preimplantation mammalian embryo is a paradigm system for studying the fundamental rules that govern fate decisions in individual cells and their coordination during the formation of simple tissues. Due to its small size with limited number of cells and cell types, semi-transparency and robust ex utero development in minimal medium, the preimplantation embryo is a highly tractable system for analysis and manipulation at the single-cell level. By the time of its implantation into the maternal uterus, the mammalian embryo consists of three distinct cell types. Cells of the embryonic epiblast (Epi) lineage generate most of the embryo-proper, while two extra-embryonic lineages, the trophectoderm (TE) and primitive endoderm (PrE) generate tissues to support the embryo during its development (Chazaud & Yamanaka, 2016; Schrode et al., 2013). These three cell types arise through what are considered to be two successive binary cell fate decisions. The first cell fate decision specifies outer cells as TE, while inner cells form the inner cell mass (ICM). The second cell fate decision bifurcates the ICM into the PrE and Epi lineages.

Genetic and pharmacological experiments have provided insights into the transcriptional and signaling mechanisms controlling lineage decisions in the preimplantation embryo. However, despite our detailed understanding of the genetic circuits that execute decisions, the factors that initially bias cells towards a specific fate remain unknown: are biases in cell fate pre-determined or might they be initiated by stochastic events (Graham & Zernicka-Goetz, 2016; Martinez Arias, Nichols, & Schroter, 2013)? Addressing this question requires measuring cell-to-cell variability in the embryo, understanding its origin, and determining its functional relevance for subsequent fate decisions.

Here we review recent developments that have allowed the quantification of molecular inter-cellular heterogeneity with unprecedented resolution. We discuss the meaning of these findings in the context of developmental cellular potential and the genetic control of fate decisions in this system. We summarize theoretical approaches to formalize the mechanisms underlying fate decisions in the ICM, and conclude by suggesting that cell-to-cell communication provides a mechanism to exploit and buffer inter-cellular variability in a self-organized process that culminates in the reproducible formation of a blastocyst. Such theoretical frameworks help identifying general strategies of cellular decision-making, and can highlight the importance of biological inputs into decisions that are difficult to access experimentally. Throughout this review we focus on the decision between the Epi and the PrE fate, and center on the mouse as the most extensively studied model system for preimplantation development. We conclude by discussing commonalities and differences in preimplantation development between different mammalian species.

Origin of the three cell types comprising the mammalian blastocyst

During the first few days of development the mouse embryo undergoes a series of distinct morphological and cellular events to transition from a single totipotent cell, the zygote, to a ~200 cell embryo comprising three distinct, spatially arranged cell types at around embryonic day (E) 4.5 (see Fig. 1 for an overview of preimplantation development and staging methods). Initially, the zygote undergoes successive rounds of cell division (referred to as cleavages), and at the 8-cell stage, cells compact and polarize to form the morula (Johnson & Ziomek, 1981). Cells acquire different positional environments and polarity through symmetric and asymmetric divisions and rearrangements with neighbors (McDole, Xiong, Iglesias, & Zheng, 2011; Sutherland, Speed, & Calarco, 1990; Watanabe, Biggins, Tannan, & Srinivas, 2014). The first cell fate decision to become TE or ICM occurs around the 16–32 cell stage (~E3.0). Outside cells are specified to the TE lineage, whereas inside cells become ICM. At E3.25 cavitation occurs and the embryo is termed a blastocyst.

Figure 1. Staging and lineage specification during mouse preimplantation development.

(A) Approximate relationship between developmental time in embryonic days from fertilization and cell number in the embryo. This relationship differs slightly between mouse strains and exact conditions of husbandry. Staging by cell number is thus preferable to facilitate comparison between studies. (B) Schematic representation of the morphological and cell fate specification events that convert the single-cell totipotent zygote from fertilization at embryonic day (E) 0.5 to the ~200 cell blastocyst comprising of three spatially distinct lineages prior to implantation at E4.5. The first cell fate choice bifurcates totipotent blastomeres to outer trophectoderm (TE; green) cells and the inner cell mass (ICM; purple). The second fate choice further subdivides the ICM into primitive endoderm (PrE; blue) and pluripotent epiblast (EPI; red), which initially arise interspersed in a seemingly random pattern, prior to sorting into two distinct layers. Zygotic Genome Activation (ZGA).

Cells of the ICM initially co-express a subset of Epi and PrE-related genes. For example, the Epi-associated homeobox transcription factor NANOG and the PrE-associated zinc-finger transcription factor GATA6 are co-expressed in all cells of the embryo at the 8-cell stage (Plusa, Piliszek, Frankenberg, Artus, & Hadjantonakis, 2008). NANOG / GATA6 co-expression within the ICM is gradually and asynchronously resolved between the 32- and 100-cell stages (~E3.25-E3.75) into a mutually exclusive expression pattern that is the first known molecular signature of the Epi/PrE cell fate decision (Chazaud, Yamanaka, Pawson, & Rossant, 2006; Plusa et al., 2008; Saiz, Williams, Seshan, & Hadjantonakis, 2016). Cell fate specification in the ICM occurs concurrently with extensive cell sorting, resolving randomly interspersed cell types into a layer of epithelial PrE cells residing adjacent to the blastocyst cavity, and overlaying the pluripotent Epi cells (Meilhac et al., 2009; Morris et al., 2010; Plusa et al., 2008). Mature Epi cells express the transcription factors (TFs) NANOG, SOX2, OCT4 and the signaling ligand FGF4, whereas the mature PrE is characterized by expression of the TFs GATA6, GATA4, SOX17, SOX7 and the signaling receptors PDGFRA and FGFR2 (Boroviak & Nichols, 2014; Chazaud et al., 2006; Guo et al., 2010; Kanai-Azuma et al., 2002; Koutsourakis, Langeveld, Patient, Beddington, & Grosveld, 1999; Plusa et al., 2008).

Dynamics of cellular developmental potential in the blastocyst

Relating the establishment of lineage-specific gene expression patterns in ICM cells with the restriction of cellular developmental potential requires functional assays. Early lineage tracing studies, and chimera experiments, suggested that ICM cells commit to their prospective fates at the 64-cell stage (E3.5) (Chazaud et al., 2006). However, live-imaging experiments observed bi-lineage contribution of individual ICM cells between the 64–100-cell stage, arguing against a strict fate commitment of the entire ICM at the mid-blastocyst stage (Morris et al., 2010). A similar conclusion was reached by Yamanaka et al. in 2010, who, using cell labeling, live imaging and FGF signaling inhibition, found that ICM cells are not committed at the 32-cell stage, but progressively lose plasticity after E4.0 (Yamanaka, Lanner, & Rossant, 2010). Further support for a comparatively late restriction of cellular potential in the ICM came from Grabarek et al. (2012), who detected bi-lineage contribution from single transplanted cells isolated from ~120-cell stage late blastocysts (~E4.5). This study also found a later loss of plasticity in PrE- compared to Epi-progenitors (Grabarek et al., 2012). Increased plasticity of PrE-biased progenitors has also been observed via live-imaging of the PrE-marker Pdgfra, which showed that PrE-biased cells do rarely adopt an Epi fate, whereas the reverse transition never occurred (Xenopoulos, Kang, Puliafito, Di Talia, & Hadjantonakis, 2015). Thus, most of the experimental evidence available to date suggests that undetermined cells persist within the ICM until approximately the late blastocyst stage. The somewhat contradictory conclusions of lineage tracing studies when trying to pinpoint the exact timing of cell commitment within the ICM may be explained by the finding that cell commitment across the ICM population is an asynchronous process (Saiz et al., 2016).

Transcription factor networks regulating cell fate decisions in the blastocyst

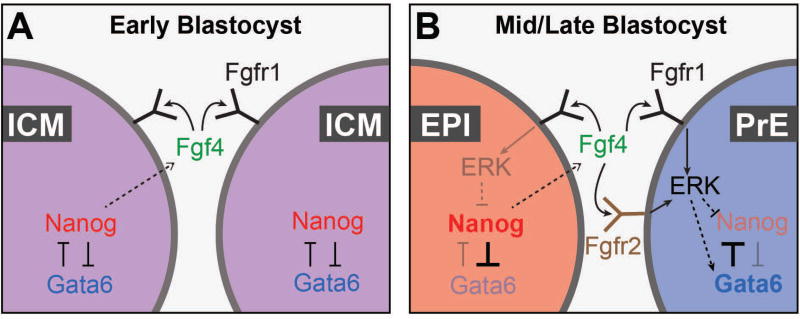

Cell fate specification and the restriction of cellular potential in the ICM are driven by a small transcription-factor network. NANOG and GATA6 play crucial functional roles in this network. Embryos lacking Nanog fail to form Epi, consequently all ICM cells convert to a PrE-like identity initially expressing GATA6 (S. Frankenberg et al., 2011). Conversely, in Gata6-deficient embryos the PrE lineage is not established, and the ICM converts to an Epi-like identity with all cells expressing NANOG (Bessonnard et al., 2014; Schrode, Saiz, Di Talia, & Hadjantonakis, 2014). Interestingly, the relative level of GATA6 impacts the proportion of cells in each lineage and the timing of their specification: Gata6 heterozygotes specify fewer PrE cells and later than wild-type embryos (Bessonnard et al., 2014; Schrode et al., 2014), while no such effect has been detected for Nanog heterozygotes (S. Frankenberg et al., 2011; Miyanari & Torres-Padilla, 2012). Levels of Nanog and Gata6 transcripts co-expressed in wild-type ICM cells are comparable to levels in specified Epi and PrE cells, indicating that cell fate specification occurs not by upregulation, but by downregulation of one of these markers within ICM cells (Guo et al., 2010). Therefore, expression of each factor is critical for the acquisition of proper cell fate identity, and for the repression of the opposing lineage program. Functional and biochemical studies of in vitro stem cell models of the blastocyst lineages have provided evidence for direct regulatory interactions between these transcription factors (Schroter, Rue, Mackenzie, & Martinez Arias, 2015; Singh, Hamazaki, Hankowski, & Terada, 2007; Wamaitha et al., 2015). Thus, mutual inhibition of Nanog and Gata6 has been proposed to constitute the core of the gene regulatory network driving ICM cell fate specification (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Gene regulatory networks orchestrating lineage divergence in the inner cell mass (ICM).

Gene regulatory networks within cells of the ICM. (A) At the early blastocyst stage, uncommitted progenitor ICM cells initially co-express the transcription factors Nanog and Gata6, and the FGF receptor Fgfr1, with a subset of ICM cells expressing Fgf4. (B) Epiblast cells (EPI) exclusively express Nanog, and Fgf4, and primitive endoderm (PrE) cells exclusively express Gata6 and Fgfr2. EPI-derived FGF4 signals in a paracrine manner to PrE via both Fgfr1 and Fgfr2, and in an autocrine manner via Fgfr1 in EPI cells.

The dynamic behavior of a mutual repression circuit has been widely studied and can lead to bistability (Arkin, Ross, & McAdams, 1998; Cherry & Adler, 2000; Gardner, Cantor, & Collins, 2000; Glass & Kauffman, 1973; Thomas, 1981). Depending on the appropriate set of parameters and initial conditions, gene expression in a cell will evolve into one of two mutually exclusive states with one of the two genes of the circuit being expressed, while the other is switched off (Fig. 3A). Chickarmane et al. (2008) were the first to show theoretically that a mutual repression circuit between Nanog and Gata6 could lead to bistability and govern Epi versus PrE choice (Chickarmane & Peterson, 2008). Schröter et al. (2015) experimentally tested this idea using an inducible ESC system to model the Epi versus PrE decision. Through measuring gene expression over time, Schröter et al. showed that the experimentally observed dynamics can be recapitulated by a simple circuit in which NANOG and GATA transcription factors mutually repress each other’s genes (Schroter et al., 2015). They also found that individual cells adopted a PrE-like fate when they exceeded specific threshold levels of inducible GATA factors, which is a central prediction of the mutual repression model. Nissen et al., (2017) recently applied this mutual repression switch between NANOG and GATA6 to model fate decisions within the ICM in the context of a 2D and 3D model of blastocyst development.

Figure 3. Properties of candidate genetic circuits executing cell fate decisions in the inner cell mass (ICM).

Cell fate decisions are coordinated by regulatory interactions between the transcription factors Nanog and Gata6. These dynamic networks can be modeled to generate quasi-potential landscapes for each genetic circuit. Stable attractor states are represented as minima on the potential state-space. These stable states correspond to ICM (purple), EPI (red) and PrE (blue). (A) In a mutual repression circuit there are two stable attractor states, EPI and PrE, whereas the ICM is unstable. The circuit results in a bistable fate choice. (B) In a mutual repression and auto-activation circuit, there is tri-stability; three stable attractor states, ICM, EPI and PrE. (C) When cells are coupled through FGF4/ERK signaling to the cell autonomous Nanog/Gata6 mutual repression auto activation circuit, cell fate choice is coordinated across the population to establish appropriate ratios of EPI:PrE. For small numbers of EPI cells, low levels of FGF4 shift the potential landscape in favour of generating more EPI. Conversely, for large numbers of EPI cells, high levels of FGF4 shift the potential landscape in favour of generating more PrE. Modified from Huang, 2013.

A gene regulatory circuit consisting exclusively of mutually repressive interactions between two genes (or nodes) has a maximum of two stable states (bi-stability). As such, this network can only capture the resolution of the NANOG/GATA6 co-expression state in the ICM, but not its establishment. This implies that additional mechanisms regulate the expression of Nanog and Gata6 in uncommitted ICM cells. For example, their initial activation may be driven by an orthogonal process that is sufficient to overcome the cross-repressive interactions. Alternatively, NANOG-GATA6 mutual repression may depend on co-factors expressed at different stages of development, and thus exerts a temporal window for the cross-inhibition circuit. These possibilities would provide an explanation for the counter-intuitive finding that NANOG levels are not elevated in individual cells in Gata6 mutants throughout development, even at stages where wild-type ICM cells normally co-express NANOG and GATA6 (Schrode et al., 2014).

Alternatively, a third stable state characterized by co-expression of lineage-specific factors can be modeled when the two nodes in a mutual repressor circuit positively regulate their own expression (tri-stability, Fig. 3B) (Huang, Guo, May, & Enver, 2007). This motivated Bessonnard et al., (2014) to use a genetic circuit model of NANOG and GATA6 auto-activation and cross-inhibition for modeling gene expression dynamics within the ICM. The authors identified a set of parameters in which the circuit is tri-stable at the single cell level corresponding to a NANOGONGATA6OFF Epi state, a NANOGOFFGATA6ON PrE state, and a NANOGONGATA6ON ICM bi-potent progenitor state. When simulated in a 5×5 grid of 25 cells that communicate via FGF/ERK signaling (Fig. 3C, discussed below), Bessonard et al.’s model recapitulated quantitative fate decision phenotypes in wild-type and mutant embryos, e.g. the establishment and resolution of the ICM state and, most remarkably, the reduced number of PrE cells in the Gata6 heterozygous mutant as well as the precocious commitment of Epi cells, that was observed experimentally in this study. The close agreement between phenotypes in the embryo and Bessonnard et al.’s model makes a strong case for a tri-stable network driving fate decisions in the ICM, however, not all of the regulatory interactions in Bessonnard et al.’s model have been independently verified. While both NANOG and GATA6 protein have been shown to bind to their own genes’ promoters in ESCs (Boyer et al., 2005; Wamaitha et al., 2015), recent studies suggest that NANOG negatively, rather than positively, regulates its own expression in ESCs (Feigelman et al., 2016; Fidalgo et al., 2012; Navarro et al., 2012). Furthermore, the function of GATA6 binding at the Gata6 promoter has not been directly investigated.

In Bessonnard et al.’s model FGF/ERK signaling triggers the exit of cells from the NANOG/GATA6 double positive state through regulation of NANOG and GATA6 expression (see later). This leads to the destabilization of the ICM progenitor attractor state (see glossary) and hence the systems’ transition from tri-stability (Fig. 3B) to bi-stability (Fig. 3A). This effect is reminiscent of the function of cytokines that control the decision between myeloid and erythroid fates in hematopoietic cells (Huang et al., 2007). However, in contrast to the hematopoietic system, where extracellular signals are thought to act symmetrically on the circuit parameters, resulting in a stochastic choice between two states, FGF/ERK signaling differentially affects NANOG and GATA6 expression and therefore acts partly as an instructive signaling cue. In either scenario changes in signaling inputs drive the intracellular network across a bifurcation (destabilization of one or two attractor states) and thus form the basis for temporal control of cell fate specification (Huang et al., 2007).

Irrespective of the exact mechanism that establishes and resolves NANOG/GATA6 co-expression progenitor state, the data discussed suggest that basic genetic networks with a mutual repression motif at their core are a central component of the machinery that regulates the decision between the Epi and the PrE fate. Mutual repression motifs(Alon, 2007), such as the one between NANOG and GATA6, are employed in several contexts where opposing lineages need to be specified from a common precursor during embryonic development and tissue homeostasis. A similar mutual repression circuit between OCT4 and CDX2 has been proposed to execute the binary decision between an ICM and TE fate, and antagonism between GATA1 and PU.1 in hematopoietic cells has long been thought to initiate specification of erythroid versus myeloid hematopoietic lineages (Graf & Enver, 2009), although a recent live imaging study has called this simple idea into question (Hoppe et al., 2016). Mutual repression circuits function by transforming small differences in the activities of the network’s core components into discrete stable states that are defined by the attractors of the system. As such, they execute fate decisions that are set by the initial conditions, i.e. the relative activities of the nodes in the network, but they are not concerned with what sets the different initial conditions in individual cells. Mutual repression circuits in single cells also do not provide a means to coordinate fate decisions in cell populations, unless they are coupled to systems mediating cell-to-cell communication, such as signaling networks.

Signaling control of the Epi/PrE cell fate decision

FGF/ERK signaling plays critical roles in cell fate specification within the ICM. Blocking FGF signaling results in the entire ICM adopting an Epi-like fate and expressing abnormally high levels of NANOG (Kang, Piliszek, Artus, & Hadjantonakis, 2013; Saiz et al., 2016; Schrode et al., 2014). This phenotype is observed in genetic loss-of-function mutants for Fgf4 and for the receptor adaptor Grb2 (Chazaud et al., 2006; Kang et al., 2013). It also occurs upon combined loss of both receptors Fgfr1 and Fgfr2, as well as with chemical inhibition of FGFR or MEK activity in wild-type embryos (Chazaud et al., 2006; Kang, Garg, & Hadjantonakis, 2017; Krawchuk, Honma-Yamanaka, Anani, & Yamanaka, 2013; Krupa et al., 2014; Molotkov, Mazot, Brewer, Cinalli, & Soriano, 2017; Nichols, Silva, Roode, & Smith, 2009; Yamanaka et al., 2010). In Fgf4 homozygous mutant embryos, cells of the ICM initially co-express NANOG and GATA6, implying FGF4 is not required for the establishment of NANOG/GATA6 double-positive ICM state, but drives the specification of PrE from a common progenitor. In agreement with this, stimulation of the FGF pathway with FGF2 or FGF4 ligands directs ICM cells to a PrE fate (Yamanaka et al., 2010).

Transient perturbation of FGF signaling at the early blastocyst stage leads to transient changes in the expression of fate markers, but cells with PrE and Epi marker expression still emerge when blastocysts are transferred to basal medium at E3.75 (Yamanaka et al., 2010). Through carefully timed signaling manipulation, Saiz et al., (2016) could further show that sensitivity to FGF/ERK signaling manipulation is asynchronously lost by individual cells in the ICM. The number of cells that respond to FGF signaling inhibition changes with the number of cells that co-express GATA6 and NANOG, and diminishes around the same time that bi-lineage potential is lost from the ICM.

Transcriptome analyses revealed that Fgf4 is the first gene to be bimodally expressed across cells of the ICM prior to overt cell fate specification (~E3.25) (Ohnishi et al., 2014). From E3.5 (~64 cell stage) onwards, there is a reciprocal expression of Fgf4 in Epi and Fgfr2 in PrE- biased cells (Guo et al., 2010; Ohnishi et al., 2014). This has led to a model in which the mutually exclusive expression of Fgf4 or Fgfr2 breaks the developmental symmetry among ICM cells, and in which FGF4 signals received by FGFR2-expressing cells drive PrE specification. The association of FGFR2 with PrE competence is however inconsistent with observations that from early stages all ICM cells respond to exogenous FGF4 to specify PrE (Kang et al., 2017; Kang et al., 2013; Krawchuk et al., 2013; Molotkov et al., 2017; Yamanaka et al., 2010; K. Yu et al., 2003), suggesting the presence of another critical FGF receptor expressed by all cells of the ICM. Recent transcriptomic and reporter-allele studies have revealed pan-ICM expression of Fgfr1 from E3.25 (~32 cells) at the time when the ICM cells begin to make lineage decisions (Kang et al., 2017; Molotkov et al., 2017; Ohnishi et al., 2014). Loss of Fgfr1 critically impairs PrE specification. This effect is exacerbated by additional loss of Fgfr2, such that combined loss of Fgfr1 and Fgfr2 completely abolishes PrE-specification and phenocopies Fgf4 mutants (Kang et al., 2017; Molotkov et al., 2017). By contrast, Fgfr2 single mutant embryos exhibit only delayed PrE specification. Exogenous FGF4 treatment efficiently converts all ICM cells of Fgfr1+/+;Fgfr2−/− embryos to PrE, but not in Fgfr1−/−;Fgfr2+/+ embryos. Together, this indicates that FGFR1 is the predominant receptor to promote PrE cell fate choice, and FGFR2 plays a secondary role in PrE lineage commitment.

FGF/ERK signaling interfaces with the transcriptional circuits that control cell differentiation in the ICM in multiple ways (Fig. 2). NANOG is required for Fgf4 expression (S. Frankenberg et al., 2011), and in turn, FGF/ERK signaling represses Nanog expression(S. Frankenberg et al., 2011; W. B. Hamilton & Brickman, 2014). Although FGF/ERK activity is not required for initial Gata6 expression between the 8–32 cell stage, from the blastocyst stage (>32 cells) FGF/ERK activity maintains Gata6 expression within the PrE (Kang et al., 2013). FGF/ERK regulation of later Gata6 expression is likely indirect, mediated by the alleviation of NANOG repression of the Gata6 promoter within the PrE (S. Frankenberg et al., 2011). Moreover, FGF/ERK activity may be reinforced within the PrE by GATA6-mediated upregulation of Fgfr2, as suggested by the direct binding of GATA6 to the Fgfr2 promoter upon GATA6 induced PrE-like fate from ESCs, and the positive correlation of Gata6 and Fgfr2 expression within individual cells of the embryo (Guo et al., 2010; Molotkov et al., 2017; Ohnishi et al., 2014; Wamaitha et al., 2015). FGF/ERK signaling thus connects the cell-autonomous genetic circuits that control the Epi versus PrE decision at the tissue level. Therefore, models based on a minimal gene-regulatory network of NANOG-GATA6 auto-activation and cross-inhibition can be extended to include coupling through FGF4/ERK signaling (Fig. 3C) (Bessonnard et al., 2014; Schroter et al., 2015).

In Bessonard et al.’s multicellular model, differences in FGF signaling strength between cells are a central for allocating cells to distinct lineages. These signaling heterogeneities do not directly determine fate in each cell, but rather serve to establish differences between cells and thus break symmetry within the system. Because FGF signaling leads to Nanog repression and consequently a potential decrease in FGF4 production, signaling differences impinge on the activity of transcriptional circuits in individual cells and percolate through the system, leading to the emergence of specific proportions of Epi and PrE. While pan-ICM expression of Fgfr1 argues against the idea that selective receptor expression between cells generates a simple ON/OFF switch in FGF/ERK signaling that drives ICM lineage specification, quantitative differences in FGF/ERK signaling may exist between individual cells. Cell-to-cell variation in signal response may be mediated by differing receptor complement, distinct feedback mechanisms and/or cell-type specific downstream effectors. The importance of FGF signaling heterogeneity in symmetry breaking within the ICM is also supported experimentally. Administration of exogenous FGF4 to Fgf4 null embryos cannot rescue the emergence of both Epi and PrE cells from the ICM, but rather the ICM exhibits a binary response in which all cells adopt either an Epi-like or a PrE-like identity, depending on the concentration of FGF4 applied (Kang et al., 2013). Due to the failed attempts to obtain robust and reproducible phospho(p)ERK antibody staining in preimplantation stage mouse embryos (Corson, Yamanaka, Lai, & Rossant, 2003; S. Frankenberg et al., 2011), the direct visualization of FGF signaling using appropriate reporters for signal production and signal reception (de la Cova, Townley, Regot, & Greenwald, 2017; Komatsu et al., 2011; Regot, Hughey, Bajar, Carrasco, & Covert, 2014) will be required to further elucidate the origins and roles of FGF signaling heterogeneities in the ICM.

Cell-to-cell variability – a driver of fate decisions

Deciphering the logic of genetic circuits helps to understand how fate decisions are executed, but does not provide insight into how initial differences arise between cells. This shortcoming is reflected in the deterministic nature of the theoretical models discussed so far, in which the fate of a single cell is fixed by the initial conditions of the system. If we aim to understand how cell fates diverge, we need to discover what determines these initial conditions in individual cells and how functionally relevant cell-to-cell variability arises within the ICM. To approach this question, we review here our current understanding of the extent and the origins of cell-to-cell variability in the preimplantation embryo.

Transcriptional heterogeneity in the embryo

Technological advances have made it possible to analyze the transcriptome of single cells and to measure the abundance of large numbers of RNA species either through multiplexed quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR), microarray analysis or RNA sequencing. These experimental approaches capture global gene expression states, thereby offering a huge depth of information, which can help identify novel markers and uncover intermediate cell states in developing tissues. On the global level, single cell transcriptomics have detected a large degree of cell-to-cell variability between individual ICM cells preceding overt lineage specification (Deng, Ramskold, Reinius, & Sandberg, 2014; Tang et al., 2010; Tang et al., 2011).

To elucidate the relationship of these heterogeneities with the genetic networks that regulate cell fate decisions, two studies have specifically focused on analyzing expression of the genes that have known or expected functions in lineage allocation in the ICM. Guo et al., (2010) used single-cell qRT-PCR to transcriptionally profile cells of the preimplantation mouse embryo. This study uncovered considerable transcriptional heterogeneity of ICM cells at the 32-cell (~E3.25) stage, a result that was later confirmed and extended by a microarray-based study (Ohnishi et al., 2014). In early ICM cells, these approaches detected co-expression of genes that are lineage-specific EPI and PrE markers at later stages. Importantly, the distribution of expression levels suggested random or stochastic expression of individual genes, with little or no correlation between genes of either lineage. However, after the 64-cell (~E3.5) stage, an inverse correlation between PrE- and EPI- related genes develops, reminiscent of the emergence of the “salt and pepper” protein expression pattern. At this stage (~E3.5), a hierarchical relationship emerges between lineage-specific genes as they become robustly and sequentially expressed during lineage specification, while the expression of the opposing lineage markers is suppressed. The lack of correlation in early co-expression of lineage-specific genes argues against a pre-patterned model for lineage allocation and instead suggests stochastic emergence of EPI and PrE progenitors from a multi-lineage primed progenitor. Intriguingly, Fgf4 is the first bimodally expressed gene observed within the ICM at 32 cells (~E3.25), prior to ICM cell fate choice (Ohnishi et al., 2014). Furthermore, as Fgfr2 is not required for initial specification events (Kang et al., 2017; Molotkov et al., 2017) (see above), the mutually exclusive expression of Fgf4 and Fgfr2 for the Epi-vs-PrE fate decision concluded from Guo’s study is a signature of lineage acquisition (Guo et al., 2010). This successive emergence of correlation in expression levels provides orthogonal evidence to support the genetic network models discussed above.

One caveat to bear in mind when interpreting the cell-to-cell variability observed in single-cell approaches is the introduction of experimental noise. Due to the very low levels of starting material, single-cell transcriptomic approaches are prone to measurement error (Brennecke et al., 2013). Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) have reduced experimental noise, for example by the use of spike-in controls, unique molecular identifiers to count individual mRNAs from a given cell, and improved computational analyses to distinguish signal from noise. Even if measurement error could be further reduced, it is important to bear in mind that transcriptome measurements provide a snapshot of a cell state that is potentially highly dynamic. Transcription occurs in bursts (see later), and mRNAs tend to be less stable than most proteins (Schwanhausser et al., 2011). Expression bursts that are uncoordinated across the ICM would manifest as noise across the population at fixed time points, which may not necessarily be functionally relevant. Furthermore, although mRNA and protein expression levels are correlated for most genes when assayed in bulk conditions (Schwanhausser et al., 2011; Tian et al., 2004), recent studies have shown that this is not necessarily true at the single-cell level (Albayrak et al., 2016; Taniguchi et al., 2010). It is therefore necessary to validate conclusions drawn from transcriptomic studies with measurements of protein expression in the embryo.

Protein heterogeneities in the ICM

Quantification of protein levels by immunofluorescence microscopy, in contrast to single-cell transcriptomics, can only capture a handful of markers concurrently, but has the added advantage of providing more precise embryonic staging and spatial information at single-cell resolution. In addition, and in contrast to mRNA-based methods, it captures the molecular species that likely drive fate decisions. The most extensively studied protein heterogeneities are that of the critical lineage-associated transcription factors, NANOG and GATA6. Immunofluorescence staining has revealed that, prior to the mutually exclusive expression pattern of NANOG/GATA6 protein at ~E3.5 (Chazaud et al., 2006), co-expression of both factors in individual cells occurs as early as the 8-cell stage (~E2.75) (Plusa et al., 2008). Quantification of GATA6 and NANOG immunofluorescence staining found no correlation between expression levels in embryos at <30 cell stage, with a large range in staining intensity. Between the 32–100 cell stage, cells are progressively specified to either (Epi or PrE) lineage, and a negative correlation between the two factors emerges. Restriction of NANOG expression to the Epi establishes bimodal NANOG expression across the ICM. Furthermore, NANOG expression becomes more homogenous throughout the Epi upon lineage specification (Plusa et al., 2008; Saiz et al., 2016; Schrode et al., 2014; Xenopoulos et al., 2015). Therefore, quantitative immunostaining studies support the conclusions drawn from transcriptomic measurements, namely that uncorrelated expression heterogeneities change into a mutually-exclusive expression pattern at the single-cell level over time.

Just as for transcriptome measurements, fixed-immunofluorescence analysis lacks the temporal component that follows expression heterogeneities in single cells over time. This requires time-lapse imaging of suitable live reporters for heterogeneously expressed genes in the ICM. Plusa et al. (2008) performed the first study of this kind, using a nuclear-localized reporter of Pdgfra expression (T. G. Hamilton, Klinghoffer, Corrin, & Soriano, 2003; Plusa et al., 2008), which is associated with the PrE. This reporter is initially heterogeneously expressed throughout the ICM, and live imaging revealed the gradual transition to an expression pattern where the reporter marks the nascent PrE layer. However, this study did not track fluorescence intensity in individual cells over time and thus could not address how temporal heterogeneities in reporter expression related to ultimate fate choice. Recently, Xenopoulos et al. (2015) achieved this, finding that levels of a nuclear-localized Nanog transcriptional reporter fluctuated within individual cells over time prior to lineage specification (<60 cells). Expression stabilized over time so that at the late blastocyst stage when cells are committed to Epi or PrE there are minimal fluctuations in expression. Together, these experiments confirm the transcriptome studies discussed earlier and suggest that there is a high degree of biological heterogeneity within the ICM during cell fate specification. Moreover, there exists a continuum of expression in the ICM, ranging from subtle variations between functionally equivalent cells at early stages of development to the distinct differences between fully differentiated cells. This leads to several open questions pertaining the origins of cell-to-cell variability within the ICM, and how might these observations be reflected in theoretical models of the fate decision process?

Origins of cell-to-cell variability

Origins of cellular heterogeneity may either be stochastic, or pre-determined by earlier events occurring in the embryo. Due to the small number of molecules involved, gene expression and especially transcription is a stochastic process that can lead to considerable heterogeneity between otherwise identical cells. The analysis of transcriptional dynamics in several simple model systems has revealed that transcription is a discontinuous process that occurs in bursts (Raser & O'Shea, 2005). In preimplantation mouse embryos scRNA-seq and allele-specific reporters have revealed abundant monoallelic gene expression, consistent with stochastic allelic transcriptional bursting(Deng et al., 2014; Miyanari & Torres-Padilla, 2012; Tang et al., 2011). Simulations of transcriptome-wide expression suggest that discontinuous promoter activation coupled with transcriptional amplification govern the observed increase in gene-expression noise from the 8-cell to blastocyst stage (Piras, Tomita, & Selvarajoo, 2014). This suggests that noise in transcriptional processes contributes significantly to the inter-cellular heterogeneity observed within the ICM.

Stochastic events during the process of gene expression that lead to cell-to-cell variability are commonly referred to as intrinsic noise sources (Elowitz, Levine, Siggia, & Swain, 2002). Intrinsic noise will differentially affect two copies of the same gene inside a single cell. Extrinsic noise by contrast affects both copies of the same gene in a cell to the same degree, but generates differences between cells in a population. Many possible extrinsic noise sources exist in the mammalian preimplantation embryo. Asynchronous cell cycle timing will lead to heterogeneity amongst ICM cells with respect to age, positional history and cell cycle phase. Due to its small size, each position in the ICM will expose cells to a distinct extracellular signaling environment and mechanical cues. Partitioning errors during cell division and differential activity of epigenetic modifiers can lead to further cell-to-cell variability and result in the differential expression of signaling components, leading to variable sensitivity to extracellular signals. Partitioning errors have been shown to cause transcriptional differences between the blastomeres of 2-cell stage embryos, with some genes continuing to become more heterogeneously expressed after ZGA, and it has been suggested that these asymmetries in lineage specifiers between 4-cell stage blastomeres might bias future lineage decisions (Biase, Cao, & Zhong, 2014; Goolam et al., 2016; Piras et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2015).

The extent and functional relevance of cell-to-cell heterogeneities have not yet been fully explored. To date, the only case where a pre-patterned, extrinsic source of variability has been linked to subsequent Epi versus PrE fate choice is the study by Morris et al. (2010). Here, the authors detected a correlation between the round of cell division that led to the internalization of an ICM cell, and its eventual cell fate (Morris et al., 2010). This observation has subsequently been explained to be the consequence of the preferential expression of Fgfr2 in cells that were internalized in the 16–32-cell transition (Krupa et al., 2014; Morris, Graham, Jedrusik, & Zernicka-Goetz, 2013), as well as increased Fgf4 mRNA expression in cells internalized in the 8- to 16-cell transition (Krupa et al., 2014). However, Yamanaka et al. (2010) detected no evidence for the lineage bias reported by Morris et al. (2010), a discrepancy that may be due to the difference in proportion of cells internalized at each round of division or the experimental methods used in the two studies (Morris, 2011; Morris et al., 2013; Morris et al., 2010; Yamanaka et al., 2010)

A recent study noted that while ICM cell fate specification occurs at the ~32-cell stage, commitment to ICM occurs later at the ~64-cell stage, coincident with the emergence of Epi and PrE progenitors (Posfai et al., 2017). This raises the possibility that the first and second fate decisions are intimately linked. As such, it is an attractive hypothesis that division history generated in the TE versus ICM decision is the extrinsic source of FGF heterogeneity required to drive the Epi versus PrE decision. However, the fact that chimera aggregation experiments and a second lineage tracing study found no functional association between wave of cell internalization and an EPI or PrE bias(Krupa et al., 2014; Yamanaka et al., 2010), together with new data suggesting only an accessory role for FGFR2 in specifying the PrE fate (Kang et al., 2017; Molotkov et al., 2017), question the relevance of this mechanism. Due to the highly regulative nature of the preimplantation embryo, perhaps the most likely scenario is that extrinsic factors such as a cell’s history as well as its position act concurrently with heterogeneity arising from the intrinsic properties of noisy biological processes to drive a largely stochastic and probabilistic lineage divergence.

Using noise to make cell fate decisions

How would cell-to-cell variability be expected to influence the behavior of multi-stable genetic circuits? Variability in cell cycle timing underlies fate decisions in the model recently proposed by Nissen et al., (2017) because fates are assigned immediately after cell division, and cells dividing at different times experience different signaling environments. The effects of gene expression noise on fate decisions within the ICM have recently been investigated by De Mot et al., (2016) in the model of coupled tri-stable switches originally proposed by Bessonnard et al., (2014). They showed that, when accounting for intrinsic noise sources, the model recapitulated the establishment of an ICM identity, followed by the emergence of a stable ratio of cells with Epi and PrE identity even in the absence of FGF signaling heterogeneity (De Mot et al., 2016) (Fig. 4A). Depending on the degree of noise in the system, cells spent variable amounts of time in the ICM state and exhibited different frequencies of cell fate switching events, which are rarely seen in vivo (Xenopoulos et al., 2015). While the exact relationship between transcriptional noise and cell fate choice remains to be determined, De Mot’s model suggests that stochastic gene expression is a further candidate mechanism to break symmetry and establish initial heterogeneities between cells that are then translated into fate decisions by gene regulatory networks (Fig. 4B,C).

Figure 4. Evolution of cell-cell variability in different models of the Epi-vs-PrE fate decision.

(A) In GRNs containing a mutual repression motif between NANOG and GATA6, small initial differences in the concentrations of the two factors will be amplified, leading to the emergence of two distinct fates. FGF/ERK signaling can be included in those models (Schroter et al., 2015), but is usually assumed to be equal between cells. (B) In the tristable model by Bessonnard et al. (2014), GATA6 and NANOG are initially expressed from low levels with similar rates, but FGF/ERK signaling is assumed to differ between cells. This drives some cells towards the NANOG-expressing Epi-state, and other cells towards the GATA6-expressing PrE-state. (C) Extension of the Bessonnard-model in De Mot et al., (2016). When considering transcriptional noise in GATA6- and NANOG expression, this can break the symmetry between cells and lead to differential signaling between cells that further locks in fates. However, in some parameter regimes this model leads to unrealistic fate switching events (not shown).

An additional role for gene expression noise during fate patterning in the preimplantation embryo has been suggested by Holmes et al., (2017), who studied TE versus ICM cell fate specification in a 3D model of the blastocyst. Holmes et al. focused on a mutual repression switch between OCT4 and CDX2 as the core gene regulatory network that executes the binary decision between an ICM and TE fate. In their model, this switch is controlled by a Hippo pathway signaling input which relays cell-cell contact mediated positional information across the population. Crucially, they showed how noise in CDX2 and OCT4 expression can allow for plasticity within a critical time window to correct mistakes in patterning. Interestingly, they identify an optimal noise level, above which unrealistic cell fate switching events occur, similar to the De Mot model. Thus, both the first and second cell fate decisions in the embryo can be modeled by transcriptional noise in antagonistic pairs of TFs (OCT4/CDX2 or GATA6/ NANOG) that breaks symmetry in conjunction with cell signaling.

The concept of noise-driven fate decisions in the mammalian blastocyst resonates with several paradigms of stochastic fate decisions in which molecular noise has been shown to break symmetry. In the phage lambda for example, fluctuations in the expression of CI and Cro, form a bistable switch that regulates the decision between lysis and lysogeny, and can partition an initially homogeneous cell population into phenotypically distinct subpopulations (Arkin et al., 1998). In Drosophila retina development, the stochastic expression of the transcription factor spineless controls rhodopsin subtype expression in R7 photoreceptor cells and thus the mosaic specification of ~30% pale and ~70% yellow ommatidia (Rister, Desplan, & Vasiliauskas, 2013; Wernet et al., 2006). Stochastic gene expression in these contexts can generate reproducible outcomes in a probabilistic manner because of the large numbers of cells involved. Fate decisions in the mammalian embryo however operate in a system with only a dozen or so cells, thus requiring mechanisms to counteract the unpredictable outcomes of stochastic decisions in single cells.

Cell fate specification in the ICM - the output of a multicellular self-organizing network

Coupling of cell-intrinsic gene regulatory networks with cell communication systems can mitigate and exploit noisy processes to generate reproducible outcomes even across small numbers of cells. As discussed earlier, FGF/ERK signaling and transcriptional networks are connected through reciprocal (or recursive) interactions at the tissue level. Therefore, signaling heterogeneities cannot be separated from transcriptional noise, as both are interconnected and influence one-another. What seems more appropriate is to view the entire ICM as an integrated multi-cellular network. In this network, cell communication exploits and buffers noise to enable the self-organized formation of a tissue with reproducible proportions of two cell types. Theoretically, this function of cell communication has been well established for generic models of cell populations with interacting genetic switches, as well as in a multi-scale model for fate decisions in the blastocyst (Koseska & Bastiaens, 2017; Tosenberger et al., 2017). In the ICM, this process would start from a primed, bipotent progenitor, and restriction of potency would occur through two routes that interact recursively: (1) transcription factor networks in single cells evolve towards certain fates under the modulation of FGF/ERK signaling, and (2) individual cells modulate the FGF signal in the ICM through ligand and/or receptor expression.

In such an integrated view of cell fate decision-making within the ICM, cell-to-cell heterogeneity is a crucial element, which is transformed through FGF/ERK signaling into the reproducible formation of the mature blastocyst. It can thereby reconcile our emerging knowledge about the diverse and pervasive nature of cellular variability with the remarkable fidelity of embryo development, and provides a basis to understand the regulative nature of early mammalian development. It also reveals parallels between the mammalian blastocyst and other fate decision paradigms (reviewed in Johnston & Desplan, 2010), where noise and cell-cell communication combine to generate robust developmental outcomes.

Lateral inhibition mediated by Delta-Notch signaling is such a mechanism – an initial stochastic decision by one cell prevents its neighbor(s) from making the same decision, ultimately leading to reproducible tissue architecture. For example, in the Drosophila proneural cluster, transcriptional noise leads to one cell producing more ligand, Delta, than its surrounding cells, hence stimulating the Notch pathway in its neighbors. This asymmetry is then reinforced through feedback mechanisms: increased Notch activity leads to both increased receptivity and decreased ligand production, and vice-versa. The Delta producing cell with low Notch activity adopts a neural precursor fate, while neighbor cells with high Notch activity adopt an epidermal fate (Seugnet, Simpson, & Haenlin, 1997; Simpson, 1997). A Delta-Notch lateral inhibition mechanism also acts in C. elegans gonadogenesis, but here heterogeneity in the timing of cell division, and subsequent exposure to differential Notch signaling environments, primes the initial stochastic decision to adopt ventral uterine precursor (VU) or anchor cell (AC) fate (Karp & Greenwald, 2003; Newman, White, & Sternberg, 1995).

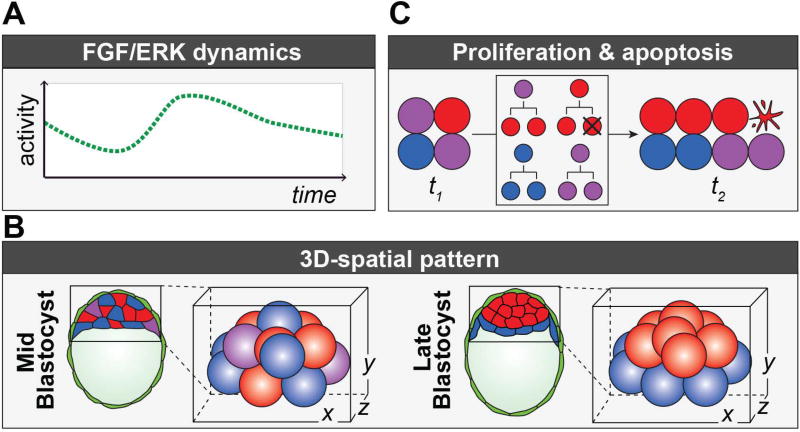

Delta-Notch signaling in these examples of lateral inhibition, and FGF/ERK signaling in the Epi/PrE decision thus perform conceptually similar functions, as both promote fate decisions and communicate them between cells. However, while Delta-Notch signaling relies on direct cell-cell contact to exert its function, FGF ligands are in principle diffusible (S. R. Yu et al., 2009), and could thus act to coordinate fate decisions in small tissues across several cell diameters. In this context, it is interesting to note that most theoretical models for the Epi/PrE fate decision assume a Delta-Notch-like nearest-neighbor signaling via FGF. Quantitative investigation of the biochemical parameters of the FGF signaling system, such as its spatial range and the response functions associated with the signal, are therefore prime targets for experimental measurements that will crucially inform models of fate decisions taking place within the ICM, and our conceptual understanding of the role of FGF signaling in general (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5. Towards a fully integrated model of ICM lineage specification.

Advancement of current models of ICM lineage specification require the integration of (A) FGF/ERK dynamics. Current models are dependent on the assumption that there is heterogeneity between cells in FGF/ERK. Direct quantitation of the intra-cellular FGF/ERK signaling activity over time is required to validate this assumption, and understand how heterogeneities arise and spatially pattern the system. (B) 3D-spatial pattern. At the mid-blastocyst stage DP, EPI and PrE cells are arranged in a seemingly random pattern, and later sort into distinct layers at the late blastocyst stage. Whether the initial pattern is truly random or dependent on the identity of nearest neighbours remains to be investigated. (C) Proliferation and apoptosis. Current models are based on a fixed number of cells, however in the embryo cells proliferate over time (t1 → t2). EPI (red) cells give rise to EPI progeny, PrE (blue) cells give rise to PrE progeny, and ICM double positive (DP) progenitors (purple) may give rise to either DP, EPI or PrE progeny (boxed region). In addition, some cells undergo apoptosis (illustrated by blebbing cell). Generation of a reproducible ratio of PrE:EPI can be fine-tuned by allocating DP cells to either PrE or EPI lineage, but could also be achieved by lineage-specific modulation in the rate of proliferation and/or apoptosis and should be measured and accounted for in future models.

Another frontier for a more comprehensive understanding of fate decisions in the ICM is the measurement of positional information and incorporation into theoretical models. For example, how the embryo’s size, relative position and identity of neighbouring ICM cells, and interactions with the TE might influence cell fate specification. In generic models of locally coupled genetic networks, the system’s behavior critically depends on its size and geometry (Koseska & Kurths, 2010). It is thus an open question if the results obtained in the 5×5 square grid studied by Bessonnard et al. and De Mot et al. represent a generalizable or specific case. To overcome these limitations, future models will need to take into account quantitative datasets on cell position and protein expression states throughout preimplantation development that have recently become available (Fischer, Corujo-Simon, Lilao-Garzon, Stelzer, & Munoz-Descalzo, 2017; Saiz et al., 2016). The model by Tosenberger et al., (2017) is the first to use a more realistic 3D geometry. What remains to be done, however, is to adjust the assumptions and compare the predictions of this model with experimental measurements (Fig. 5B).

Lastly, theoretical models need to be constrained with measurements of cell division events, to correctly capture the growth in cell number, heterogeneities in birth timing and the role of changing cell positions within the developing blastocyst as cells make lineage decisions (Fig. 5C). Extending theoretical descriptions in this direction also allows a critical test of robustness of any theoretical model of ICM cell fate specification: it needs to reproduce the scalability of the embryo, reflected in the observation that relative ratio of Epi-to-PrE scales with embryo size in experimentally generated half- and double-sized embryos (Nissen et al., 2017; Saiz et al., 2016).

ICM differentiation across species – similar networks, different pathways?

The mouse blastocyst is a paradigm for studying cell fate decisions in a small multi-cellular network. It parallels other animal systems that execute cell fate decisions using mutually repressive transcription factor networks, and cell-to-cell signaling to re-enforce and co-ordinate initial stochastic choice. Can the models of ICM lineage decision developed in the mouse system be applied to other mammalian species? The blastocyst is a universal stage of mammalian embryonic development, but despite the morphology and much of the gene regulatory network (GRN) being conserved there are interspecies differences in cell fate specification (Blakeley et al., 2015; S. R. Frankenberg, de Barros, Rossant, & Renfree, 2016; Rossant & Tam, 2017). The expression patterns of the lineage-associated transcription factors CDX2 (TE), NANOG, OCT4, SOX2 (Epi), and GATA6, GATA4, SOX17 (PrE) are highly conserved across human, monkey and cow (Kuijk et al., 2012; Nakamura et al., 2016; Roode et al., 2012), indicating that the core GRN orchestrating lineage divergence may be functionally equivalent. However, the timing of lineage-restricted expression differs between species. For example, while in mouse restriction of CDX2 to the prospective TE occurs at the morula stage, in primates CDX2 is only detected from the early blastocyst stage (Nakamura et al., 2016; Niakan & Eggan, 2013). TE versus ICM specification thus occurs relatively late in these species, implying that the timing between the first and second fate decisions is greatly reduced. This was corroborated by recent scRNA-seq studies of human blastocysts, which revealed that the three blastocyst lineages are specified almost simultaneously from the early blastocyst stage (E5), and only resolve to a mutually exclusive expression pattern at the late blastocyst stage (E7) (Petropoulos et al., 2016).

During ICM specification in the marmoset monkey, cow and human, a similar pattern of co-expression of NANOG/GATA6 has been observed in uncommitted ICM progenitors prior to the sorting of cells with mutually exclusive expression into distinct layers (Boroviak et al., 2015; Kuijk et al., 2012). However, while the divergence of Epi and PrE lineages in the mouse depends exclusively on FGF signaling(Yamanaka et al., 2010), in bovine and marmoset MEK/FGF signaling inhibition reduces, but does not fully abolish the GATA6-positive hypoblast (PrE) lineage (Boroviak et al., 2015; Kuijk et al., 2012), indicating that other signaling pathways must regulate the core GRN. In the marmoset, this was shown to be WNT signaling, as combinatorial inhibition of both WNT and MEK signaling completely ablated hypoblast formation (Boroviak et al., 2015). Strikingly, in human embryos MEK inhibition has no effect on lineage specification, and it remains an open question what signal(s) drive Epi and hypoblast segregation in this context (Kuijk et al., 2012; Roode et al., 2012). These observations raise the intriguing possibility that although the network motifs underlying blastocyst development may be conserved between mammalian species, different molecular pathways have been co-opted to function as specific nodes. In order to generalize knowledge gained in mouse system it will be important to determine how much of the core-transcription factor network has been conserved, and to what extent there are key species-specific differences (for example in signaling factors).

Acknowledgments

We thank Sui Huang for developing many of the ideas that have inspired the field and help explain how cellular populations execute robust fate decisions at the single cell level, and for generously providing the vector diagrams, which we modified for Figure 3. We thank Hui Ma, Aneta Koseska, Pau Rue and members of the Hadjantonakis lab for discussions and comments on this review. Work in the Hadjantonakis laboratory is supported by grants from the NIH (R01DK084391, P30CA008748) and NYSTEM (C029568); work in the Schröter laboratory is supported by the Max Planck Society.

Table of Definitions (Glossary)

- Cell fate

The developmental destiny of a cell to become a particular cell type.

- Specification

Allocation of cell fate. If left unperturbed in its natural environment, a specified cell will differentiate to the specified cell type. Cell fate at specification is not fixed, but can at times be reversed to correct developmental errors or during experimental manipulation

- Determination

Fixation of cell fate. Even when its natural environment is perturbed, a determined cell will differentiate to the determined cell type. Cell fate at determination is fixed, and developmental potential is restricted.

- Cell state

The molecular profile of a cell, i.e. the concentration and activity state of each molecular species in the cell.

- Developmental (cellular) potential

The range of different cell types one cell can give rise to.

- Developmental (cellular) plasticity

The ability of a cell to deviate from its specified fate and adopt an alternative fate.

- Bias

An increased propensity of a cell to give rise to one cell type over another.

- Cellular heterogeneity

Variation in gene-expression between individual cells across a population.

- Noise

Variability of cell states in a population exposed to the same external conditions; also: Undirected variability of the state of a single cell over time.

- Stochastic process

A process where individual events cannot be accurately predicted but happen randomly according to a probability distribution.

- Bi- / Tri- / Multi-stability

Property of a dynamical system. The concentration of the components of the system (e.g. a cell) will change until one of two, three or multiple stable states are reached.

- Attractor

Stable state of a dynamical system that the system will evolve towards.

- Gene regulatory network

A set of genes that interact and regulate each other. GRNs can be cell-intrinsic (e.g. transcription factor networks), or involve cell-cell signaling.

- Non-linearity

A regulatory interaction displays non-linearity if the relative response of gene A to a change in the concentration of regulator B depends on the absolute concentration of B. Arises e.g. through cooperativity in the function of B and is often required for multi-stability.

References

- Albayrak C, Jordi CA, Zechner C, Lin J, Bichsel CA, Khammash M, Tay S. Digital Quantification of Proteins and mRNA in Single Mammalian Cells. Mol Cell. 2016;61(6):914–924. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alon U. Network motifs: theory and experimental approaches. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(6):450–461. doi: 10.1038/nrg2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkin A, Ross J, McAdams HH. Stochastic kinetic analysis of developmental pathway bifurcation in phage lambda-infected Escherichia coli cells. Genetics. 1998;149(4):1633–1648. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.4.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessonnard S, De Mot L, Gonze D, Barriol M, Dennis C, Goldbeter A, Chazaud C. Gata6, Nanog and Erk signaling control cell fate in the inner cell mass through a tristable regulatory network. Development. 2014;141(19):3637–3648. doi: 10.1242/dev.109678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biase FH, Cao X, Zhong S. Cell fate inclination within 2-cell and 4-cell mouse embryos revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Genome Res. 2014;24(11):1787–1796. doi: 10.1101/gr.177725.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeley P, Fogarty NM, del Valle I, Wamaitha SE, Hu TX, Elder K, Niakan KK. Defining the three cell lineages of the human blastocyst by single-cell RNA-seq. Development. 2015;142(18):3151–3165. doi: 10.1242/dev.123547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroviak T, Loos R, Lombard P, Okahara J, Behr R, Sasaki E, Bertone P. Lineage-Specific Profiling Delineates the Emergence and Progression of Naive Pluripotency in Mammalian Embryogenesis. Dev Cell. 2015;35(3):366–382. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroviak T, Nichols J. The birth of embryonic pluripotency. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2014;369(1657):20130541. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer LA, Lee TI, Cole MF, Johnstone SE, Levine SS, Zucker JP, Young RA. Core transcriptional regulatory circuitry in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2005;122(6):947–956. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke P, Anders S, Kim JK, Kolodziejczyk AA, Zhang X, Proserpio V, Heisler MG. Accounting for technical noise in single-cell RNA-seq experiments. Nat Methods. 2013;10(11):1093–1095. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazaud C, Yamanaka Y. Lineage specification in the mouse preimplantation embryo. Development. 2016;143(7):1063–1074. doi: 10.1242/dev.128314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazaud C, Yamanaka Y, Pawson T, Rossant J. Early lineage segregation between epiblast and primitive endoderm in mouse blastocysts through the Grb2-MAPK pathway. Dev Cell. 2006;10(5):615–624. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry JL, Adler FR. How to make a biological switch. J Theor Biol. 2000;203(2):117–133. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2000.1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chickarmane V, Peterson C. A computational model for understanding stem cell, trophectoderm and endoderm lineage determination. PLoS One. 2008;3(10):e3478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corson LB, Yamanaka Y, Lai KM, Rossant J. Spatial and temporal patterns of ERK signaling during mouse embryogenesis. Development. 2003;130(19):4527–4537. doi: 10.1242/dev.00669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Cova C, Townley R, Regot S, Greenwald I. A Real-Time Biosensor for ERK Activity Reveals Signaling Dynamics during C. elegans Cell Fate Specification. Dev Cell. 2017;42(5):542–553. e544. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Mot L, Gonze D, Bessonnard S, Chazaud C, Goldbeter A, Dupont G. Cell Fate Specification Based on Tristability in the Inner Cell Mass of Mouse Blastocysts. Biophys J. 2016;110(3):710–722. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Q, Ramskold D, Reinius B, Sandberg R. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals dynamic, random monoallelic gene expression in mammalian cells. Science. 2014;343(6167):193–196. doi: 10.1126/science.1245316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elowitz MB, Levine AJ, Siggia ED, Swain PS. Stochastic gene expression in a single cell. Science. 2002;297(5584):1183–1186. doi: 10.1126/science.1070919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigelman J, Ganscha S, Hastreiter S, Schwarzfischer M, Filipczyk A, Schroeder T, Claassen M. Analysis of Cell Lineage Trees by Exact Bayesian Inference Identifies Negative Autoregulation of Nanog in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell Syst. 2016;3(5):480–490. e413. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidalgo M, Faiola F, Pereira CF, Ding J, Saunders A, Gingold J, Wang J. Zfp281 mediates Nanog autorepression through recruitment of the NuRD complex and inhibits somatic cell reprogramming. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(40):16202–16207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208533109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer SC, Corujo-Simon E, Lilao-Garzon J, Stelzer EHK, Munoz-Descalzo S. Three-dimensional cell neighbourhood impacts differentiation in the inner mass cells of the mouse blastocyst. bioRxiv. 2017 doi: 10.1101/159301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg S, Gerbe F, Bessonnard S, Belville C, Pouchin P, Bardot O, Chazaud C. Primitive endoderm differentiates via a three-step mechanism involving Nanog and RTK signaling. Dev Cell. 2011;21(6):1005–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankenberg SR, de Barros FR, Rossant J, Renfree MB. The mammalian blastocyst. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Dev Biol. 2016;5(2):210–232. doi: 10.1002/wdev.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner TS, Cantor CR, Collins JJ. Construction of a genetic toggle switch in Escherichia coli. Nature. 2000;403(6767):339–342. doi: 10.1038/35002131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass L, Kauffman SA. The logical analysis of continuous, non-linear biochemical control networks. J Theor Biol. 1973;39(1):103–129. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(73)90208-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goolam M, Scialdone A, Graham SJ, Macaulay IC, Jedrusik A, Hupalowska A, Zernicka-Goetz M. Heterogeneity in Oct4 and Sox2 Targets Biases Cell Fate in 4-Cell Mouse Embryos. Cell. 2016;165(1):61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabarek JB, Zyzynska K, Saiz N, Piliszek A, Frankenberg S, Nichols J, Plusa B. Differential plasticity of epiblast and primitive endoderm precursors within the ICM of the early mouse embryo. Development. 2012;139(1):129–139. doi: 10.1242/dev.067702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf T, Enver T. Forcing cells to change lineages. Nature. 2009;462(7273):587–594. doi: 10.1038/nature08533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham SJL, Zernicka-Goetz M. The Acquisition of Cell Fate in Mouse Development: How Do Cells First Become Heterogeneous? Current Topics in Developmental Biology. 2016 doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, Huss M, Tong GQ, Wang C, Li Sun L, Clarke ND, Robson P. Resolution of cell fate decisions revealed by single-cell gene expression analysis from zygote to blastocyst. Dev Cell. 2010;18(4):675–685. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton TG, Klinghoffer RA, Corrin PD, Soriano P. Evolutionary divergence of platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor signaling mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(11):4013–4025. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.11.4013-4025.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton WB, Brickman JM. Erk signaling suppresses embryonic stem cell self-renewal to specify endoderm. Cell Rep. 2014;9(6):2056–2070. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WR, Reyes de Mochel NS, Wang Q, Du H, Peng T, Chiang M, Nie Q. Gene Expression Noise Enhances Robust Organization of the Early Mammalian Blastocyst. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(1):e1005320. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppe PS, Schwarzfischer M, Loeffler D, Kokkaliaris KD, Hilsenbeck O, Moritz N, Schroeder T. Early myeloid lineage choice is not initiated by random PU.1 to GATA1 protein ratios. Nature. 2016;535(7611):299–302. doi: 10.1038/nature18320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S. Hybrid T-helper cells: stabilizing the moderate center in a polarized system. PLoS Biol. 2013;11(8):e1001632. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Guo YP, May G, Enver T. Bifurcation dynamics in lineage-commitment in bipotent progenitor cells. Dev Biol. 2007;305(2):695–713. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.02.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MH, Ziomek CA. The foundation of two distinct cell lineages within the mouse morula. Cell. 1981;24(1):71–80. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90502-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston RJ, Jr, Desplan C. Stochastic mechanisms of cell fate specification that yield random or robust outcomes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:689–719. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai-Azuma M, Kanai Y, Gad JM, Tajima Y, Taya C, Kurohmaru M, Hayashi Y. Depletion of definitive gut endoderm in Sox17-null mutant mice. Development. 2002;129(10):2367–2379. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.10.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M, Garg V, Hadjantonakis AK. Lineage Establishment and Progression within the Inner Cell Mass of the Mouse Blastocyst Requires FGFR1 and FGFR2. Dev Cell. 2017;41(5):496–510. e495. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M, Piliszek A, Artus J, Hadjantonakis AK. FGF4 is required for lineage restriction and salt-and-pepper distribution of primitive endoderm factors but not their initial expression in the mouse. Development. 2013;140(2):267–279. doi: 10.1242/dev.084996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp X, Greenwald I. Post-transcriptional regulation of the E/Daughterless ortholog HLH-2, negative feedback, and birth order bias during the AC/VU decision in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2003;17(24):3100–3111. doi: 10.1101/gad.1160803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komatsu N, Aoki K, Yamada M, Yukinaga H, Fujita Y, Kamioka Y, Matsuda M. Development of an optimized backbone of FRET biosensors for kinases and GTPases. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22(23):4647–4656. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-01-0072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koseska A, Bastiaens PI. Cell signaling as a cognitive process. EMBO J. 2017;36(5):568–582. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koseska A, Kurths J. Topological structures enhance the presence of dynamical regimes in synthetic networks. Chaos. 2010;20(4):045111. doi: 10.1063/1.3515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutsourakis M, Langeveld A, Patient R, Beddington R, Grosveld F. The transcription factor GATA6 is essential for early extraembryonic development. Development. 1999;126(9):723–732. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.9.723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krawchuk D, Honma-Yamanaka N, Anani S, Yamanaka Y. FGF4 is a limiting factor controlling the proportions of primitive endoderm and epiblast in the ICM of the mouse blastocyst. Dev Biol. 2013;384(1):65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupa M, Mazur E, Szczepanska K, Filimonow K, Maleszewski M, Suwinska A. Allocation of inner cells to epiblast vs primitive endoderm in the mouse embryo is biased but not determined by the round of asymmetric divisions (8-->16- and 16-->32-cells) Dev Biol. 2014;385(1):136–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuijk EW, van Tol LT, Van de Velde H, Wubbolts R, Welling M, Geijsen N, Roelen BA. The roles of FGF and MAP kinase signaling in the segregation of the epiblast and hypoblast cell lineages in bovine and human embryos. Development. 2012;139(5):871–882. doi: 10.1242/dev.071688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Arias A, Nichols J, Schroter C. A molecular basis for developmental plasticity in early mammalian embryos. Development. 2013;140(17):3499–3510. doi: 10.1242/dev.091959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDole K, Xiong Y, Iglesias PA, Zheng Y. Lineage mapping the pre-implantation mouse embryo by two-photon microscopy, new insights into the segregation of cell fates. Dev Biol. 2011;355(2):239–249. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meilhac SM, Adams RJ, Morris SA, Danckaert A, Le Garrec JF, Zernicka-Goetz M. Active cell movements coupled to positional induction are involved in lineage segregation in the mouse blastocyst. Dev Biol. 2009;331(2):210–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.04.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyanari Y, Torres-Padilla ME. Control of ground-state pluripotency by allelic regulation of Nanog. Nature. 2012;483(7390):470–473. doi: 10.1038/nature10807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molotkov A, Mazot P, Brewer JR, Cinalli RM, Soriano P. Distinct Requirements for FGFR1 and FGFR2 in Primitive Endoderm Development and Exit from Pluripotency. Dev Cell. 2017;41(5):511–526. e514. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SA. Cell fate in the early mouse embryo: sorting out the influence of developmental history on lineage choice. Reprod Biomed Online. 2011;22(6):521–524. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SA, Graham SJ, Jedrusik A, Zernicka-Goetz M. The differential response to Fgf signalling in cells internalized at different times influences lineage segregation in preimplantation mouse embryos. Open Biol. 2013;3(11):130104. doi: 10.1098/rsob.130104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris SA, Teo RT, Li H, Robson P, Glover DM, Zernicka-Goetz M. Origin and formation of the first two distinct cell types of the inner cell mass in the mouse embryo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(14):6364–6369. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0915063107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura T, Okamoto I, Sasaki K, Yabuta Y, Iwatani C, Tsuchiya H, Saitou M. A developmental coordinate of pluripotency among mice, monkeys and humans. Nature. 2016;537(7618):57–62. doi: 10.1038/nature19096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro P, Festuccia N, Colby D, Gagliardi A, Mullin NP, Zhang W, Chambers I. OCT4/SOX2-independent Nanog autorepression modulates heterogeneous Nanog gene expression in mouse ES cells. EMBO J. 2012;31(24):4547–4562. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AP, White JG, Sternberg PW. The Caenorhabditis elegans lin-12 gene mediates induction of ventral uterine specialization by the anchor cell. Development. 1995;121(2):263–271. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niakan KK, Eggan K. Analysis of human embryos from zygote to blastocyst reveals distinct gene expression patterns relative to the mouse. Dev Biol. 2013;375(1):54–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichols J, Silva J, Roode M, Smith A. Suppression of Erk signalling promotes ground state pluripotency in the mouse embryo. Development. 2009;136(19):3215–3222. doi: 10.1242/dev.038893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen SB, Perera M, Gonzalez JM, Morgani SM, Jensen MH, Sneppen K, Trusina A. Four simple rules that are sufficient to generate the mammalian blastocyst. PLoS Biol. 2017;15(7):e2000737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2000737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi Y, Huber W, Tsumura A, Kang M, Xenopoulos P, Kurimoto K, Hiiragi T. Cell-to-cell expression variability followed by signal reinforcement progressively segregates early mouse lineages. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16(1):27–37. doi: 10.1038/ncb2881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petropoulos S, Edsgard D, Reinius B, Deng Q, Panula SP, Codeluppi S, Lanner F. Single-Cell RNA-Seq Reveals Lineage and X Chromosome Dynamics in Human Preimplantation Embryos. Cell. 2016;165(4):1012–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piras V, Tomita M, Selvarajoo K. Transcriptome-wide variability in single embryonic development cells. Sci Rep. 2014;4:7137. doi: 10.1038/srep07137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]