Abstract

Recently, the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines revised the recommendations for diagnosis of chronic hypertension. The new classification system includes a diagnosis of stage 1 hypertension in adults with blood pressures 130-139 mmHg/80-89mmHg. We sought to compare outcomes among women at high-risk for preeclampsia with stage 1 hypertension and assessed whether women with stage 1 hypertension had benefit from aspirin treatment compared to high-risk normotensive women. We performed a secondary analysis of the high-risk aspirin trial and included women with prior preeclampsia or diabetes. Among these women 827 (81%) were classified as normotensive while 193 (19%) were classified as stage 1 hypertensive. Among women receiving placebo, preeclampsia, occurred significantly more often in women with stage 1 hypertension compared to normotensive high-risk women after adjustment for maternal age and BMI (39.1% vs. 15.1%, RR 2.49; 95%CI 1.74-3.55). Further, women with stage 1 hypertension had a significant risk reduction related to aspirin prophylaxis (RR 0.61; 95% CI 0.39-0.94) that was not seen in normotensive high-risk women (RR 0.97; 95%CI 0.70-1.34). Application of the ACC/AHA guidelines in a high-risk population demonstrates that in the setting of other risk factors, the presence of stage 1 hypertension is associated with a significantly increased risk of preeclampsia when compared to high-risk normotensive women. These findings emphasize the importance of recognition of stage 1 hypertension as an additive risk factor in women at high risk for preeclampsia and the benefit of aspirin.

Keywords: chronic hypertension, pregnancy, preeclampsia, aspirin, stage 1 hypertension

Introduction

The American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines have revised the recommendations for diagnosis of chronic hypertension in adults based on compelling evidence that incremental increases in blood pressure (BP) impact the risk of future cardiovascular disease as well as clinical complications and death.1 Formerly classified as “pre-hypertension”, the new parameters now consider stage 1 hypertension as systolic BP measurement between 130 and 139mmHg or diastolic BP measurement between 80 and 89mmHg. Though the updated guidelines extensively outlined the effect of graded blood pressure increases in non-pregnant adults, discussions of pregnancy implications are limited.

It is well-documented that women entering pregnancy with chronic hypertension under the previous guidelines (now classified as stage 2 hypertension) are at increased risk of pregnancy-related morbidity, particularly preeclampsia, small for gestational age (SGA) infants and iatrogenic preterm delivery compared to normotensive women2–4. Women at high risk for preeclampsia, including women with chronic hypertension, pre-existing diabetes, prior preeclampsia, multiple gestations, renal disease, and autoimmune disease are treated with aspirin prophylaxis in early pregnancy to reduce this risk5,6. Prior studies have shown maternal and neonatal benefit, minimal harm, and potential cost-effectiveness of treatment with low-dose aspirin7–10. While the evidence supports the use of aspirin for preeclampsia prevention in women at high risk, the benefit is modest, with most studies showing a 10-15% risk reduction in these groups.9,11

Stage 1 hypertension, previously classified as pre-hypertension, is not included in recommendations for aspirin prophylaxis.5,6 To our knowledge, no studies have yet evaluated maternal and neonatal outcomes in high-risk women entering pregnancy with stage 1 hypertension by the new ACC/AHA guidelines. We sought to compare maternal and neonatal outcomes among high-risk women with newly identified stage 1 hypertension compared to high-risk normotensive women under the revised guidelines, and to assess whether women with an additional risk factor for preeclampsia (i.e. stage 1 hypertension) had further benefit from aspirin treatment compared to high-risk normotensive women.

Methods

Study Design

This is a secondary analysis of data collected in a double-blinded, randomized, placebo controlled trial of low-dose aspirin for prevention of preeclampsia in pregnant women at high-risk for preeclampsia. Study data are publicly available through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) Data and Specimen Hub (DASH), and the original study design and findings have been previously reported.12 Anonymized data and materials have been made publicly available at the NICHD Data and Specimen Hub (DASH) and can be accessed at https://dash.nichd.nih.gov. Briefly, four high-risk pregnant populations [women with 1) chronic hypertension, 2) preexisting insulin-dependent diabetes, 3) multi-fetal gestations, or 4) history of preeclampsia] were recruited and enrolled between 13 and 26 weeks gestation. Participants were randomized to receive either low-dose aspirin (60mg/day) or placebo, and outcome data were collected by study staff and medical record abstraction. The primary outcome of the original study was preeclampsia diagnosis. Studies were carried out as part of the NICHD’s Maternal Fetal Medicine Unit Network (MFMU) at 13 centers, and all studies were approved and monitored by each institution’s respective Institutional Review Board. Subjects provided written informed consent prior to study participation.

Participants and “High-Risk” Criteria

Briefly, pregnant women at high-risk for preeclampsia were recruited between 13 and 26 weeks gestation. Eligibility criteria for the four high-risk groups included: diagnosis of chronic hypertension confirmed by BP of ≥140/90mmH or anti-hypertension medications, diagnosis of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, multi-fetal gestations confirmed by ultrasound, or previous preeclampsia confirmed by medical record or oral history and certain overlaps of high-risk criteria.12 Eligible women were assigned to a single-blind medication compliance test and those who passed were randomly assigned to receive either 60mg aspirin or placebo (lactose) daily from the time of randomization until delivery.

Outcome Variables

For this analysis, we included women in the preexisting diabetes and prior preeclampsia groups. We excluded women in the chronic hypertension group as they had a confirmed diagnosis of stage 2 hypertension and women with multiple gestations as early pregnancy hemodynamic changes in twin gestations have been shown to differ from singleton gestations.13,14 Of the participants with preexisting diabetes or prior preeclampsia, women with data available for enrollment blood pressure and maternal and neonatal outcomes were included. Fifteen women (1.5%) were excluded due to missing outcome data. Forty-two women (4.1%) were excluded due to enrollment blood pressures ≥140/90 (stage 2 hypertension). Maternal blood pressure was measured by study staff in a standardized fashion using a mercury sphygmomanometer as previously described.15 Multiple cuff sizes were available to ensure appropriate cuff size based on arm circumference. Briefly, patients were allowed to rest for at least ten minutes prior to measurement and were seated comfortably during the measurement, which was done in a quiet location with trained staff. For this analysis, participants were classified according to blood pressure measurement at enrollment (≤26 weeks gestation). Women with a systolic blood pressure 130-139mmHg or diastolic blood pressure of 80-89mmHg were classified with stage 1 hypertension under the recent ACC/AHA guidelines1 and compared to women with blood pressure below 130mmHg systolic and 80mmHg diastolic. We also performed a sensitivity analysis restricting our sample to women who were enrolled prior to 20 weeks gestation (n=635).

Our primary outcome was preeclampsia as adjudicated during the original study, which included both mild and severe preeclampsia. Preeclampsia diagnosis was verified in the original study by medical record review by three blinded, MFMU study members. Secondary outcomes included small for gestational age infant, placental abruption, indicated or spontaneous preterm delivery (PTD), and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission. In participants without hypertension or proteinuria at enrollment, preeclampsia was defined using guidelines in place at the time as new onset hypertension (≥140 mmHg systolic or ≥90 mmHg diastolic on two occasions at least 4 hours apart) plus proteinuria (either ≥300mg per 24 hours or 2+ or more by dipstick on two or more occasions). In normotensive participants with proteinuria at enrollment, preeclampsia diagnosis required thrombocytopenia, elevated liver function tests, or hypertension accompanied by either severe headache, epigastric pain, or sudden increase in proteinuria. Severe preeclampsia was defined as severe hypertension (≥160/110mmHg) and proteinuria; urinary protein excretion ≥5 grams per day with any degree of hypertension; hypertension complicated by pulmonary edema or thrombocytopenia (≤100,000); hemolysis, elevated liver function tests and a low platelet count (HELLP syndrome) or eclampsia. Small for gestational age was defined as a birth weight below the 10th percentile for singletons.16 Indicated preterm delivery was defined as delivery prior to 37 weeks gestation for maternal or fetal indications. Spontaneous preterm delivery denotes delivery prior to 37 weeks after spontaneous preterm labor or premature rupture of membranes. Diagnosis of placental abruption was by clinical findings of vaginal bleeding and uterine tenderness. NICU admission was collected from the infant medical record.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using STATA software, version 14 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Continuous variables were compared using student t-tests and Wilcoxon-Mann Whitney tests as appropriate. Categorical variables were analyzed using Chi-square or Fisher’s exact where appropriate. Multivariable analysis included log binomial regression to evaluate the independent association between enrollment systolic and diastolic blood pressure (as a discrete variable: hypertensive versus normal) and preeclampsia in women treated with aspirin and placebo. Adjustment covariates were chosen a priori based on previous literature and included maternal age and pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI). Results were presented as adjusted risk ratios with corresponding 95% confidence intervals, and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons as a priori, preeclampsia was our primary endpoint.

Results

Participants with pre-existing insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus and a history of preeclampsia were included, and those with multi-fetal gestations and preexisting chronic hypertension (now classified as stage 2 hypertension) were excluded. Therefore, of the 2,539 women enrolled in the original study, 1020 were included this analysis (Table 1). The majority of the study population (81%, n= 827/1020) were normotensive at enrollment, and approximately one-fifth (19%, n=193/1020) were newly identified with stage 1 hypertension according to the current ACC/AHA guidelines. Both groups had similar smoking history and infant birth weights, along with similar racial compositions. The women with stage 1 hypertension tended to be slightly older, heavier, and deliver earlier. Women randomized to aspirin prophylaxis started treatment at a mean gestational age of 19.4 ± 4.0 weeks.

Table 1.

Maternal and pregnancy characteristics by hypertensive group.

| Characteristic | Normotension | Stage 1 Hypertension* | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 827 | 193 | |

| Age (years) | 24.9 ± 5.7 | 26.2 ±5.4 | <0.001 |

| Pre-pregnancy body mass index (kg/m2) | 27.1 ± 7.2 | 30.9 ± 8.4 | <0.001 |

| Predominant Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 293 (35.4%) | 76 (39.4%) | |

| African American | 485 (58.7%) | 107 (55.4%) | |

| Hispanic | 45 (5.4%) | 10 (5.2%) | |

| Other | 4 (0.5%) | 0 | 0.6 |

| Smoking | 159 (19.2) | 30 (15.5) | 0.2 |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 37.1 ± 3.7 | 36.3 ± 4.0 | 0.001 |

| Birth weight (grams) | 3140 ± 797 | 3041 ± 903 | 0.3 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg)† | 109 ± 10 | 124 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg)† | 64 ± 8 | 78 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| High-risk group | |||

| Prior preeclampsia | 487 (58.8%) | 107 (55.4%) | |

| Pre-existing diabetes | 340 (41.2%) | 86 (44.6%) | 0.4 |

Stage 1 hypertension: enrollment systolic blood pressure 130-139 mmHg or diastolic 80-89 mmHg

Measured at enrollment (13-26 weeks of pregnancy)

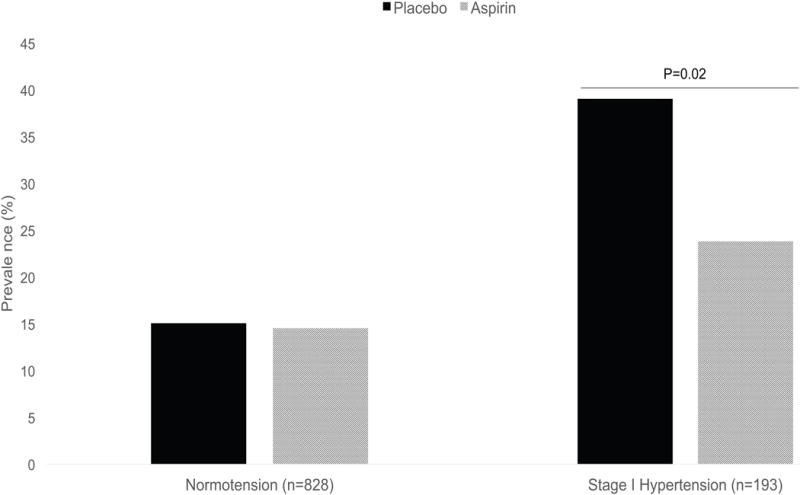

Within this high-risk population, 15.1% (n=63/416) of women entering pregnancy as normotensive and randomized to placebo developed preeclampsia (Table 2). Strikingly, of the women entering pregnancy with stage 1 hypertension and receiving placebo, 39.1% (n=36/92) were diagnosed with preeclampsia (p<0.001 compared to normotensive women). This increased incidence is mainly related to mild preeclampsia, with 8.2% of normotensive women developing mild preeclampsia compared to 27.2% of stage 1 hypertensive women (p=0.002). Thus, in this high-risk population, entering pregnancy with stage 1 hypertension was associated with a greater than two-fold increased risk of preeclampsia (risk ratio (RR) 2.49; 95% CI 1.74-3.55) compared to normotensive women. Stage 1 hypertension did not impact rates of placental abruption, indicated or spontaneous preterm birth, infant birth weight, or NICU admission in our cohort.

Table 2.

Maternal and neonatal outcomes in normotensive and stage 1 hypertensive women among women randomized to receive placebo.

| PLACEBO | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Normotension N=416 n(%) |

Stage 1

Hypertension N=92 n(%) |

p value | Adjusted Relative Risk* (95%CI) |

| Preeclampsia | 63 (15.1%) | 36 (39.1%) | <0.001 | 2.49 (1.74-3.55) |

| Mild Preeclampsia | 34 (8.2%) | 25 (27.2%) | <0.001 | 3.06 (1.89-4.95) |

| Severe Preeclampsia | 29 (7.0%) | 11 (12.0%) | 0.1 | 1.78 (0.89-3.56) |

| Placental abruption | 10 (2.4%) | 1 (1.1%) | 0.6 | 0.60 (0.07-5.10) |

| Small for gestation age | 39 (9.5%) | 5 (5.5%) | 0.2 | 0.57 (0.24-1.38) |

| Indicated PTD | 58 (16.2%) | 15 (20.6%) | 0.1 | 1.46 (0.88-2.41) |

| Spontaneous PTD | 55 (13.3%) | 17 (18.9%) | 0.1 | 1.45 (0.89-2.45) |

| NICU admission | 123 (29.6%) | 29 (31.5%) | 0.6 | 1.10 (0.78-1.54) |

PTD= preterm delivery, NICU= neonatal intensive care unit

Adjusted for maternal age and pre-pregnancy BMI

Interestingly, the incidence of preeclampsia in these high-risk women was not reduced among normotensive women receiving low-dose aspirin when compared to normotensive women receiving placebo (14.6%, n=60/411 vs. 15.1%, n=63/416 respectively). This was true across both mild and severe preeclampsia. As shown in Table 4, aspirin was not effective in reducing preeclampsia in high-risk normotensive women, with a RR 0.97 (95%CI 0.70-1.34) for all preeclampsia, a RR 0.92 (95%CI 0.58-1.47) for mild disease and a RR 1.01 (95%CI 0.62-1.66) for severe disease. However, low-dose aspirin appeared to affect rates of preeclampsia and benefit women entering pregnancy with stage 1 hypertension. In women with stage 1 hypertension, low-dose aspirin was associated with a 39% reduction of preeclampsia (RR 0.61; 95% CI 0.39-0.94) compared to stage 1 hypertensive women receiving placebo, with a 45% reduction in mild disease (RR 0.55; 95%CI 0.31-0.97) and a 25% reduction in severe disease (RR 0.75; 95%CI 0.32-1.71).

Table 4.

Risk of adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes by randomization to placebo or aspirin in normotensive and stage 1 hypertensive women.

| OUTCOME | NOMOTENSION | STAGE 1 HYPERTENSION | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLACEBO N =416 |

ASPIRIN N=411 RR (95%CI) |

PLACEBO N=92 |

ASPIRIN N=101 RR (95%CI) |

|

| Preeclampsia | Ref. | 0.97 (0.70-1.34) | Ref. | 0.61 (0.39-0.94) |

| Mild Preeclampsia | Ref. | 0.92 (0.58-1.47) | Ref. | 0.55 (0.31-0.97) |

| Severe Preeclampsia | Ref. | 1.01 (0.62-1.66) | Ref. | 0.75 (0.32-1.72) |

| Small for gestational age | Ref. | 0.67 (0.42-1.08) | Ref. | 1.09 (0.34-3.47) |

| Spontaneous PTD | Ref. | 0.90 (0.63-1.30) | Ref. | 0.63 (0.32-1.25) |

| NICU admission | Ref. | 0.88 (0.71-1.10) | Ref. | 1.10 (0.73-1.65) |

PTD= preterm delivery, NICU= neonatal intensive care unit

In a sensitivity analysis, we included only women with an enrollment blood pressure measured prior to 20 weeks gestational age (Supplemental Tables S2 and S3) and confirmed our findings. In this analysis, women with stage 1 hypertension have a similar magnitude of increased maternal and neonatal risks as well risk reduction with aspirin as our overall cohort.

Discussion

In this study, application of the current ACC/AHA guidelines in a high-risk population demonstrates that in the setting of other risk factors, the presence of stage 1 hypertension is associated with a significantly increased risk of preeclampsia when compared to high-risk women who are normotensive. In our cohort, women with stage 1 hypertension and an additional risk factor (prior preeclampsia or diabetes) have a preeclampsia incidence of 39.1% compared to 15.1% in normotensive women with prior preeclampsia or diabetes. In the original high-risk aspirin trial, women with stage 2 chronic hypertension without another risk factor, in comparison, had a preeclampsia incidence of approximately 25%.12 We also found that among women with another risk factor and stage 1 hypertension, the efficacy of aspirin is notably increased compared to normotensive high-risk women. These findings emphasize the importance of stage 1 hypertension as a potentially additive risk factor in women at high risk for preeclampsia, and highlight the possible benefit of aspirin prophylaxis in this population.

This study is limited by the fact that it is an unplanned secondary analysis of a randomized trial, which limits our findings. It is further limited by our lack of pre-pregnancy blood pressure measurements for reclassification of chronic hypertension diagnoses. While pre-pregnancy blood pressures would be ideal for diagnosis, prior studies have shown that women do not consistently seek primary care outside of pregnancy. Pre-conception care engagement rates range between 18-45% in reproductive-age women with chronic diseases in the United States, thus early pregnancy blood pressures may be all that is available for the obstetrician.17 Further, patients were recruited into the study up to a gestational age of 26 weeks. We addressed this in a sensitivity analysis in which we included only women with an enrollment blood pressure measured prior to 20 weeks gestation and confirmed our findings (Supplemental Tables S2 and S3). The recently published Combined Multimarker Screening and Randomized Patient Treatment with Aspirin for Evidence-Based Preeclampsia Prevention (ASPRE) trial found that treatment of women at high risk for preterm preeclampsia (based on an algorithm utilizing maternal factors, biophysical and biochemical measurements) with 150mg of aspirin initiated between 11 and 14 weeks gestation resulted in a decreased incidence of preterm preeclampsia compared to placebo.8 Similarly, other studies have shown a substantially reduced risk of preeclampsia in women who initiated treatment prior to 16 weeks. There were a small number of women in our study who were initiated on low-dose aspirin prior to 16 weeks (n=258), limiting our ability to compare our findings to this larger study. Further, the dose of aspirin used in the original trial (60mg) is lower than the dose currently utilized in clinical practice, which ranges from 81mg to 160mg. Our ability to compare our results to the ASPRE trial is limited by our cohort size, with only a small number of women (n=23) women developing early preeclampsia (<34 weeks).

The scientific rigor of the standardized measurement of blood pressure by trained study staff is a strength of our study along with the large sample size considering the challenges and burden of conducting a clinical trial in thousands of pregnant participants. However, it is important to note the small number of women within this trial with blood pressures that met the new ACC/AHA criteria for stage 1 hypertension (n=193). Additionally, this secondary analysis is performed on a cohort recruited between 1989 and 1992. Incontrovertibly, the demographics of this group differ from a contemporaneous cohort with advancing maternal age and increasing rates of obesity.18 However, given that aspirin is now considered the standard of care in a high-risk population, it is unlikely that a placebo-controlled randomized trial to address this question in a contemporaneous cohort would be ethical. Further study on a low-risk population to address the implications of stage 1 hypertension and the effect of aspirin is warranted.

While our findings may not seem particularly innovative in a cohort of women who already meet criteria for aspirin prophylaxis, we contend that there are important implications for both an understanding of the pathophysiology of the disease and intervention as well as identification of target at-risk women for future studies. First, while randomized studies of over 30,000 high-risk women have clearly established the benefit of aspirin, the mechanism of action has not yet been identified.19,20 A deeper understanding of which high-risk pregnant women are most likely to benefit from aspirin is an important step forward for our field and our comprehension of the pathophysiology of preeclampsia.21 Our findings support the hypothesis that there are likely many pathways to disease in preeclampsia, and that aspirin likely acts along one of those pathways. Further, we contend that these pathways almost certainly differ among the subgroups of women who are considered “high-risk” for preeclampsia. We found that women who are normotensive but at “high-risk” for preeclampsia might only have minimal benefit from aspirin. In our cohort, treatment with aspirin in high-risk women entering pregnancy as normotensive reduced the risk of preeclampsia by 3%, compared to a 39% reduction in women entering pregnancy with stage 1 hypertension. Aspirin resistance is a controversial, but documented entity in the cardiology literature that has not been well studied in the obstetric population.22–24 While this may not be especially relevant with administration of a drug that has an extensively studied maternal and fetal safety profile, these findings will become more germane as we begin studying newer interventions for preeclampsia prevention. For example, both statins and metformin are in early stages of randomized trials for preeclampsia risk reduction, both of which have a less favorable risk profile than aspirin.25–29 The obvious extension of this is that, based on our findings, future trials might consider targeting high-risk women who are normotensive entering pregnancy, as those women seem to have possibly have only minimal benefit from aspirin prophylaxis.

Supplementary Material

Figure 1.

Prevalence of preeclampsia in normotensive and stage 1 hypertensive women receiving aspirin or placebo during pregnancy.

Table 3.

Maternal and neonatal outcomes in normotensive and stage 1 hypertensive women among women randomized to receive low-dose aspirin.

| ASPIRIN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Normotension N=411 n(%) |

Stage 1

Hypertension N=101 n(%) |

P value | Adjusted Relative Risk* (95%CI) |

| Preeclampsia | 60 (14.6%) | 24 (23.8%) | 0.03 | 1.59 (1.02-2.50) |

| Mild Preeclampsia | 31 (7.5%) | 15 (14.9%) | 0.02 | 2.03 (1.10-3.75) |

| Severe Preeclampsia | 29 (7.1%) | 9 (8.9%) | 0.5 | 1.16 (0.55-2.47) |

| Placental abruption | 5 (1.2%) | 1 (1.0%) | 0.7 | 0.78 (0.07-8.84) |

| Small for gestational age | 26 (6.4%) | 6 (6.0%) | 0.9 | 1.21 (0.50-2.96) |

| Indicated PTD | 54 (15.0%) | 27 (30.3%) | 0.001 | 2.05 (1.35-3.12) |

| Spontaneous PTD | 49 (12.0%) | 12 (11.9%) | 0.8 | 1.11 (0.58-2.11) |

| NICU admission | 107 (25.7%) | 35 (34.3%) | 0.07 | 1.35 (0.97-1.89) |

PTD= preterm delivery, NICU= neonatal intensive care unit

Adjusted for maternal age and pre-pregnancy BMI

Perspectives.

As the adoption of the ACC/AHA guidelines becomes more widespread, there will be an increasing number of reproductive age women who will fall into the category of stage 1 hypertension.1 Thus, this study provides initial evidence on pregnancy outcomes and an approach to management of these women. Our findings suggest that women entering pregnancy with stage 1 chronic hypertension diagnosed by the current ACC/AHA guidelines and an additional risk factor have an increased rate of maternal complications compared to “high-risk” normotensive women. Our findings also suggest that low-dose aspirin may be particularly effective prophylaxis to reduce the risk of preeclampsia in this population. Further study using contemporaneous cohorts is needed in this high-risk population.

What is New?

High-risk patients with stage 1 hypertension have a high prevalence of maternal and neonatal complications.

Aspirin may be more effective at preeclampsia prevention in women with stage 1 hypertension.

What is Relevant?

The new ACC/AHA guidelines do not directly address hypertension in pregnancy but they may identify a particular group of women at high risk for pregnancy complications.

Understanding which high-risk women respond to aspirin prophylaxis may give some insight into the mechanism of action of aspirin in preeclampsia prevention.

Summary.

Women entering pregnancy with stage 1 chronic hypertension diagnosed by the current ACC/AHA guidelines and an additional risk factor have an increased rate of maternal complications compared to “high-risk” normotensive women.

Our findings also suggest that low-dose aspirin may be particularly effective prophylaxis to reduce the risk of preeclampsia in this population.

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding

Data collection supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD21410, HD21434, HD21366, HD21380, HD19897, HD21414, HD21386, HD21363). This work was supported by the American Heart Association 16SFRNN28930000) (Hubel) supporting EFS, AH, and JMC.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults. Hypertension. 2017 doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000065. November 2017:HYP.0000000000000065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ankumah N-A, Cantu J, Jauk V, et al. Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with mild chronic hypertension before 20 weeks of gestation. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(5):966–972. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sibai BM. Chronic hypertension in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(2):369–377. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02128-2. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12151166. Accessed November 9, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bramham K, Parnell B, Nelson-Piercy C, Seed PT, Poston L, Chappell LC. Chronic hypertension and pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348(apr15 7):g2301–g2301. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts JM, Druzin M, August PA, et al. ACOG Guidelines: Hypertension in Pregnancy. 2012 doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.LeFevre ML. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(11):819–826. doi: 10.7326/M14-1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Werner EF, Hauspurg AK, Rouse DJ. A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Low-Dose Aspirin Prophylaxis for the Prevention of Preeclampsia in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126(6):1242–1250. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rolnik DL, Wright D, Poon LC, et al. Aspirin versus Placebo in Pregnancies at High Risk for Preterm Preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(7):613–622. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Askie LM, Duley L, Henderson-Smart DJ, Stewart LA, PARIS Collaborative Group Antiplatelet agents for prevention of pre-eclampsia: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet. 2007;369(9575):1791–1798. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60712-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberge S, Nicolaides K, Demers S, Hyett J, Chaillet N, Bujold E. The role of aspirin dose on the prevention of preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216(2):110–120.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.09.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henderson JT, Whitlock EP, O’Connor E, Senger CA, Thompson JH, Rowland MG. Low-dose aspirin for prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(10):695–703. doi: 10.7326/M13-2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caritis S, Sibai B, Hauth J, et al. Low-dose aspirin to prevent preeclampsia in women at high risk. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Network of Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(11):701–705. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803123381101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kametas NA, McAuliffe F, Krampl E, Chambers J, Nicolaides KH. Maternal cardiac function in twin pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102(4):806–815. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00807-x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14551012. Accessed March 12, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuleva M, Youssef A, Maroni E, et al. Maternal cardiac function in normal twin pregnancy: a longitudinal study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38(5):575–580. doi: 10.1002/uog.8936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davey DA, MacGillivray I. The classification and definition of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158(4):892–898. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90090-7. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3364501. Accessed March 30, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brenner WE, Edelman DA, Hendricks CH. A standard of fetal growth for the United States of America. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;126(5):555–564. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90748-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steel A, Lucke J, Adams J. The prevalence and nature of the use of preconception services by women with chronic health conditions: an integrative review. BMC Womens Health. 2015;15:14. doi: 10.1186/s12905-015-0165-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sween LK, Althouse AD, Roberts JM. Early-pregnancy percent body fat in relation to preeclampsia risk in obese women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(1):84.e1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cadavid AP. Aspirin: The Mechanism of Action Revisited in the Context of Pregnancy Complications. Front Immunol. 2017;8:261. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dekker GA, Sibai BM. Low-dose aspirin in the prevention of preeclampsia and fetal growth retardation: rationale, mechanisms, and clinical trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168(1 Pt 1):214–227. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(12)90917-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8420330. Accessed March 12, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greer IA, Brenner B, Gris J-C. Antithrombotic treatment for pregnancy complications: which path for the journey to precision medicine? Br J Haematol. 2014;165(5):585–599. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navaratnam K, Alfirevic A, Alfirevic Z. Low dose aspirin and pregnancy: how important is aspirin resistance? BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;123(9):1481–1487. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.13914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snoep JD, Hovens MMC, Eikenboom JCJ, van der Bom JG, Huisman MV. Association of laboratory-defined aspirin resistance with a higher risk of recurrent cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(15):1593–1599. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gasparyan AY, Watson T, Lip GYH. The role of aspirin in cardiovascular prevention: implications of aspirin resistance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(19):1829–1843. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winterfeld U, Allignol A, Panchaud A, et al. Pregnancy outcome following maternal exposure to statins: a multicentre prospective study. BJOG An Int J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;120(4):463–471. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costantine MM, Cleary K, Hebert MF, et al. Safety and pharmacokinetics of pravastatin used for the prevention of preeclampsia in high-risk pregnant women: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(6):720.e1–720.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cleary KL, Roney K, Costantine M. Challenges of studying drugs in pregnancy for off-label indications: Pravastatin for preeclampsia prevention. Semin Perinatol. 2014;38(8):523–527. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2014.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brownfoot FC, Hastie R, Hannan NJ, et al. Metformin as a prevention and treatment for preeclampsia: effects on soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 and soluble endoglin secretion and endothelial dysfunction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(3):356.e1–356.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lautatzis M-E, Goulis DG, Vrontakis M. Efficacy and safety of metformin during pregnancy in women with gestational diabetes mellitus or polycystic ovary syndrome: A systematic review. Metabolism. 2013;62(11):1522–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.