Abstract

Background

Delayed return to work is common after acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), but has undergone little detailed evaluation. We examined factors associated with the timing of return to work after ARDS, along with lost earnings and shifts in healthcare coverage.

Methods

Five-year, multisite prospective, longitudinal cohort study of 138 2-year ARDS survivors hospitalised between 2004 and 2007. Employment and healthcare coverage were collected via structured interview. Predictors of time to return to work were evaluated using Fine and Grey regression analysis. Lost earnings were estimated using Bureau of Labor Statistics data.

Results

Sixty-seven (49%) of the 138 2-year survivors were employed prior to ARDS. Among 64 5-year survivors, 20 (31%) never returned to work across 5-year follow-up. Predictors of delayed return to work (HR (95% CI)) included baseline Charlson Comorbidity Index (0.77 (0.59 to 0.99) per point; p=0.04), mechanical ventilation duration (0.67 (0.55 to 0.82) per day up to 5 days; p<0.001) and discharge to a healthcare facility (0.49 (0.26 to 0.93); p=0.03). Forty-nine of 64 (77%) 5-year survivors incurred lost earnings, with average (SD) losses ranging from US$38 354 (21,533) to US$43 510 (25,753) per person per year. Jobless, non-retired survivors experienced a 33% decrease in private health insurance and concomitant 37% rise in government-funded coverage.

Conclusions

A cross 5-year follow-up, nearly one-third of previously employed ARDS survivors never returned to work. Delayed return to work was associated with patient-related and intensive care unit/hospital-related factors, substantial lost earnings and a marked rise in government-funded healthcare coverage. These important consequences emphasise the need to design and evaluate vocation-based interventions to assist ARDS survivors return to work.

INTRODUCTION

With advances in critical care, the short-term mortality of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) has improved, resulting in a growing population of ARDS survivors.1 Consequently, research is increasingly focused on understanding and improving the survivorship experience after ARDS,2 given the high prevalence of long-lasting functional sequelae.3–6 Among post-ARDS sequelae, survivors often experience delayed return to work (ie, paid employment), with up to one-half being jobless at 12 months after ARDS.6,7

Delays in return to work have major financial implications for patients and their families, employers and society.8 Despite its importance, there is an incomplete understanding of the timing of survivors’ return to work and related economic implications, along with associated patient-related and hospital-related risk factors. Such data are important to understand the magnitude of this issue and aid in identifying at-risk individuals for vocational rehabilitation interventions.9–12 Hence, in a cohort of long-term ARDS survivors longitudinally followed for 5 years, our objectives are to: (1) assess return to work 5 years after ARDS; (2) evaluate factors associated with timing of return to work and (3) evaluate lost earnings and changes in healthcare coverage for jobless survivors.8

METHODS

Study design and participants

This analysis was conducted as part of the Improving Care of ALI Patients (ICAP) study, a prospective longitudinal cohort study evaluating patient outcomes out to 5 years after ARDS. From 2004 to late 2007, patients were enrolled from 13 intensive care units (ICUs) in 4 teaching hospitals in Baltimore, Maryland. We enrolled consecutive mechanically ventilated adult patients meeting the American–European consensus conference criteria for acute lung injury,13 in effect at the time of the study. Hereafter, the term ARDS (rather than acute lung injury) is used, consistent with newer Berlin criteria.14 Exclusion criteria included: (1) pre-existing comorbidity with a life expectancy not exceeding 6 months (eg, metastatic cancer), (2) pre-existing cognitive impairment or communication/language barriers, (3) homelessness or no fixed address for follow-up, (4) hospital transfer with pre-existing ARDS of >24 hours duration, (5) mechanically ventilated for >5 days before ARDS onset, (6) prior lung resection, and (7) a physician order for no escalation of care (eg, no vasopressors) at ARDS onset. Neurological specialty ICUs were not included to avoid enrolling patients with primary neurological disease or trauma.

This analysis focused on the timing of return to work in long-term survivors of ARDS who reported full-time or part-time employment prior to ARDS. Long-term survivors were defined as those surviving for ≥2 years after ARDS. Written informed consent was obtained after patients regained capacity (or via proxies if the patient was incapacitated). The institutional review boards of all participating study sites approved this research.

Employment status and return to work outcome variable

Employment data were collected using a self-report survey instrument similar to that used in prior research,15 which included employment status and number of hours working per week. Baseline employment status, prior to ARDS, also was recorded based on interview with proxies and/or patients during hospitalisation, and re-confirmed during a follow-up interview. Timing of return to work was assessed longitudinally via a one-time, retrospective structured interview at 2-year follow-up, and every 4 months thereafter until completion of 5-year follow-up. At initial 2-year post-ARDS follow-up, survivors’ responses regarding time to return to work after hospital discharge were used to determine employment status 1 year after ARDS.

Calculation of estimated lost earnings

Lost earnings were estimated for all patients reporting fulltime or part-time employment before ARDS. Estimated lost earnings were defined as the difference between estimated and potential earnings. As performed in prior research,16 earnings were estimated for each survivor using annual age-matched and sex-matched weekly wage data from the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics (www.bls.gov). Matched weekly wages were then divided by 40 hours per week to estimate hourly wages, and subsequently multiplied by patient-reported work hours per week to estimate weekly wages or by pre-hospitalisation work hours per week to estimate potential weekly wages. Weekly wages were multiplied by 50 weeks to derive annual estimates. Survivors working, but not reporting number of hours (2 of 113 [2%] cases), were assumed to work the same number of hours as the next time point, if reporting a similar employment status. If future hours were unavailable or employment status never recurred, survivors working full-time or part-time, respectively, were assumed to work at 100% and 50% of pre-ARDS hours. Those who were retired or dead were assumed to incur zero lost earnings. Lost earnings were adjusted to 2017 US dollars using the US consumer price index (www.bls.gov). Finally, post-hoc sensitivity analyses were performed involving different methods to calculate lost wages, including imputing wages based on sex and self-reported occupation and excluding survivors ≥65 years of age (online supplementary file 1).

Healthcare coverage

Healthcare coverage (categorised as private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid or no coverage) was reported by patients or their proxies at the initial 2-year and each subsequent post-ARDS assessment. Baseline coverage, immediately prior to ARDS, was collected during follow-up interviews with patients, or if unavailable, from the medical record. To minimise the contribution of age-related government-funded (ie, Medicare or Medicaid) coverage, our evaluation only focused on healthcare coverage among survivors <65 years old at each follow-up.

Quality of life and hospitalisations

Survivors’ health-related quality of life status 2, 3, 4 and 5 years after ARDS was evaluated using the Medical Outcomes Study Short-Form 36 version 2 (SF-36) and inpatient hospitalisations occurring since the prior follow-up period were reported.17

Patient and Hospital-Related exposure variables

Patient baseline characteristics evaluated included age, sex, race, years of full-time education, pre-ARDS residence (ie, home or other) and comorbidities (evaluated using the Charlson18 and the Functional19,20 Comorbidity Indices). ICU-related exposures included admission diagnosis category; Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score21; mean daily Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score22; mechanical ventilation; ICU and hospital stay; and discharge location (ie, home, nursing home and rehabilitation facility).23

Statistical analysis

Data were summarised using median and IQR for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables, and compared, as appropriate, in unadjusted analyses using Wilcoxon rank-sum and χ2 tests. Survival analysis was used to evaluate the primary outcome of time to return to work in survivors employed prior to ARDS. Before returning to work, survivors could experience one of two competing risks: retirement and death. Incorporating these competing risks, we performed Fine and Grey regression analysis24 evaluating the association of the primary outcome with patient-related and ICU/hospital-related exposures, with HR <1 indicating longer time to return to work. Survivors who neither experienced a competing risk nor returned to work were censored at 60-month follow-up. Appropriate modelling of continuous variables was confirmed by visually inspecting scatterplots of residuals using locally weighted scatterplot smoothing (LOWESS).25 Non-linear associations were present for patient age and mechanical ventilation duration, and were addressed by modelling each variable using a linear spline with a ‘knot’ at 40 years old and 5 days of mechanical ventilation, respectively; thus, permitting different linear associations of each variable with the primary outcome before and after the designated ‘knot’.26

Multivariable regression models were created by including all exposure variables with a crude association of p≤0.20 with the primary outcome. Potential overfitting of the final multivariable model was prevented by performing separate multivariable models for baseline and hospital variables, and from these two models, subsequently selecting all covariates with p≤0.20 for a final multivariable model. Post-hoc sensitivity analyses were performed to (1) evaluate for potential effects of age-related changes in employment and (2) select variables for the multivariable model using a backward stepwise approach27 (online supplementary file 1).

The linearity of each exposure variable was confirmed using LOWESS of Martingale residuals from the regression models. A Schoenfeld residual plot for each variable confirmed no violation of the proportional hazards assumption.28 For all multivariable models, multicollinearity was evaluated using variance inflation factors, with collinearity observed between APACHE II score, mean daily SOFA score, duration of mechanical ventilation and hospital length of stay (LOS). Collinearity was addressed by omitting the non-significant variables (APACHE II, mean daily SOFA and hospital LOS) from the final multivariable model. From the final multivariable analysis, the adjusted hazard of returning to work was illustrated using a cumulative incidence function, with median times to return to work estimated and compared using prototypical values for variables that were statistically significant in the multivariable model (ie, Charlson Comorbidity Index [median=0 vs 75th percentile=2], mechanical ventilation duration [median=9 days] and discharge location [home vs healthcare facility]). Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided p<0.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata V.14.2 (College Station, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

Patient flow and characteristics

Of the 138 long-term survivors of ARDS who completed the initial 2-year follow-up interview, 67 (49%) were employed prior to ARDS (table 1) and 87% (54 of 67) worked full-time. Overall, the 67 previously employed survivors were 63% men, with a median (IQR) age of 46 (39, 54) years and 12 (11, 14) years of full-time education. Four of 67 (6%) were ≥65 years old prior to ARDS. These survivors had a median (IQR) APACHE II score of 23 (18, 28), and received 9 (5, 17) days of mechanical ventilation. Following hospitalisation, 37 (55%) of these survivors were discharged to a healthcare facility. These variables were relatively similar for the 71 survivors who were not employed prior to ARDS (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and ICU variables of long-term ARDS survivors (n=138)

| Working prior to ARDS (n=67), stratified by post-ARDS outcome | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Not working prior to ARDS (n=71) |

All patients (n=67) |

Ever returned to work (n=45) |

Never returned to work (n=17) |

Retired or died (n=5) |

|

| Demographic variables* | |||||

| Age, median (IQR) (year) | 49 (40, 58) | 46 (39, 54) | 44 (36, 49) | 45 (41, 49) | 50 (40, 61) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 32 (45%) | 42 (63%) | 31 (69%) | 9 (53%) | 2 (40%) |

| White race, n (%) | 40 (56%) | 38 (57%) | 23 (51%) | 10 (59%) | 5 (100%) |

| Full-time education, median (IQR) (year) | 12 (11, 14) | 12 (11, 14) | 12 (12, 16) | 12 (12, 14) | 12 (11, 14) |

| Living at home before admission, n (%) | 66 (93%) | 65 (97%) | 44 (98%) | 16 (94%) | 5 (100%) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score, median (IQR) | 1 (1, 4) | 1 (0, 2) | 0 (0, 1) | 2 (1, 4) | 1 (1, 3) |

| Functional Comorbidity Index, median (IQR) | 1 (1, 3) | 1 (0, 2) | 1 (0, 2) | 2 (0, 3) | 1 (1, 3) |

| Hospital variables | |||||

| Admission diagnosis | |||||

| Respiratory failure/pneumonia | 39 (55%) | 36 (54%) | 23 (51%) | 10 (59%) | 3 (60%) |

| Sepsis (non-pulmonary)/infectious disease | 8 (11%) | 13 (19%) | 8 (18%) | 4 (24%) | 1 (20%) |

| Trauma | 2 (3%) | 8 (12%) | 8 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 7 (10%) | 5 (7%) | 4 (9%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other† | 15 (21%) | 5 (7%) | 2 (4%) | 2 (12%) | 1 (20%) |

| APACHE II score, median (IQR) | 24 (19, 29) | 23 (18, 28) | 20 (17, 26) | 25 (20, 28) | 24 (19, 29) |

| Mean daily SOFA score, median (IQR) | 5 (4, 7) | 5 (4, 7) | 4 (3, 5) | 5 (4, 8) | 5 (4, 7) |

| Days with delirium, median (IQR) | 2 (1, 7) | 3 (1, 7) | 3 (1, 7) | 4 (1, 8) | 3 (1, 7) |

| Days with coma, median (IQR) | 3 (1, 8) | 3 (1, 8) | 3 (1, 6) | 5 (3, 6) | 3 (1, 8) |

| Days on mechanical ventilation, median (IQR) | 8 (5, 17) | 9 (5, 17) | 9 (6, 13) | 12 (7, 17) | 8 (5, 17) |

| ICU LOS, median (IQR) (day) | 14 (8, 23) | 14 (9, 22) | 14 (11, 20) | 16 (12, 24) | 14 (8, 23) |

| Hospital LOS, median (IQR) (day) | 23 (16, 45) | 23 (16, 35) | 21 (16, 28) | 32 (26, 37) | 23 (16, 45) |

| Hospital discharge location | |||||

| Home | 31 (44%) | 30 (45%) | 24 (53%) | 6 (35%) | 0 (0%) |

| Rehabilitation facility | 28 (39%) | 34 (51%) | 19 (42%) | 10 (59%) | 5 (100%) |

| Long-term ventilator facility | 2 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Nursing home | 8 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other hospital | 2 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

Missing data (n, %): full-time education (5 of 71 [7%] not working and 1 of 67 [1%] working).

Among survivors not working before ARDS, ‘other’ diagnoses included neurological (n=1, 1%), cardiovascular (n=4, 6%), rheumatological/orthopaedic (n=1, 1%), endocrine (n=2, 3%), haematologic (n=2, 3%) and other (n=5, 7%). Among survivors working before ARDS, diagnoses included neurological (n=3, 4%), cardiovascular (n=1, 1%) and rheumatological/orthopaedic (n=1, 1%).

APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; ICU, intensive care unit; LOS, length of stay; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Outcomes and risk factors related to delayed return to work

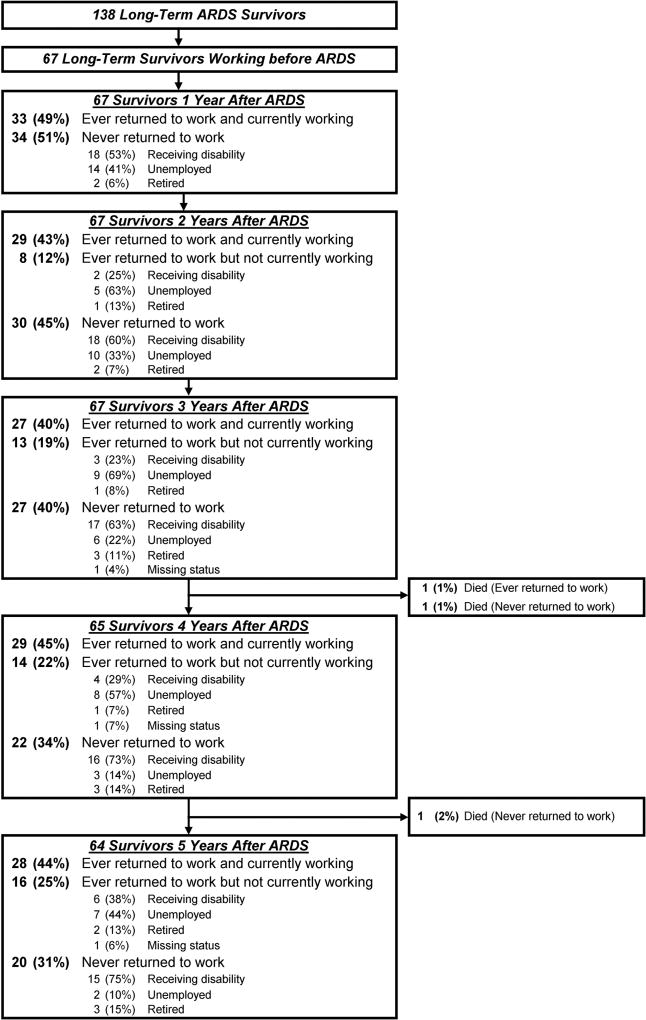

The cumulative proportion of previously employed long-term survivors who were alive and had not returned to work at 1, 2 and 5 years after ARDS was 51%, 45% and 31%, respectively (figure 1). Among the 34 survivors who had not returned to work by 1 year, 22 (65%, including 2 who died) never returned to work over 5-year follow-up. Five years after ARDS, the majority (58%) of previously employed survivors who were not working were receiving disability (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Long-term employment status up to 5 years after ARDS. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Forty-five (67%) survivors returned to work over 5-year follow-up. These survivors comprised 38 of 54 (70%) and 7 of 13 (54%) survivors who worked full-time and part-time before ARDS, respectively. Notably, among the 33 survivors who returned to work 1 year after ARDS, 12 (36%) subsequently became jobless over the 5-year follow-up period. Among these 12 survivors, 6 (50%) became jobless due to health-related reasons or disability.

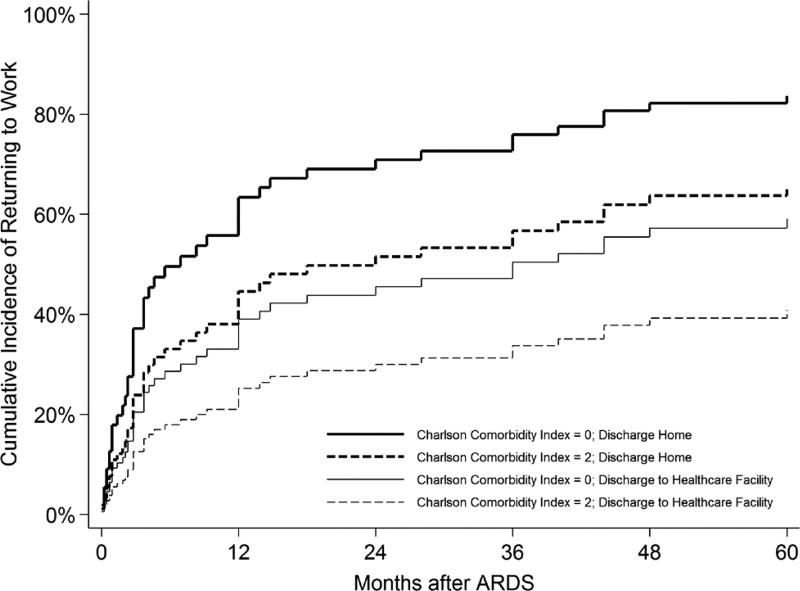

Unadjusted associations of patient-related and hospital-related factors with the time to return to work are presented in online supplementary eTable 1. The final multivariable model (table 2) demonstrated an independent association of three variables with a longer time to return to work: Charlson Comorbidity Index (hazard ratio (95% CI) 0.77 (0.59 to 0.99); p=0.04), mechanical ventilation duration (0.67 per day up to 5 days (0.55 to 0.82); p<0.001) and hospital discharge to a healthcare facility (0.49 (0.26 to 0.93); p=0.03). When adjusted for these three variables, we estimated a 67% cumulative incidence of survivors ever returning to work over 5-year follow-up, with a median (IQR) time to return to work of 14 (3, 60) months. Having a Charlson Comorbidity Index of 2 (versus 0) was associated with a 16%–18% absolute reduction in 5-year return to work, while discharge to a healthcare facility (versus home) was associated with an incremental absolute reduction of 24%–26%. Hence, assuming a median of 9 days of mechanical ventilation, two baseline comorbidities and hospital discharge to a healthcare facility, an estimated 45% of such survivors would return to work, with a median (IQR) time to return to work of 60 (9, 60) months. In contrast, assuming the same duration of mechanical ventilation, zero baseline comorbidities and discharge to home, an estimated 87% would return to work, with a median time of 4 (2, 18) months (figure 2). In post-hoc sensitivity analyses of the multivariable regression model, there were no important differences in results (Online supplementary file 1).

Table 2.

Multivariable predictors of returning to work within 5 years of ARDS*

| Characteristic | HR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Model 1: baseline variables | ||

| Age at ARDS diagnosis, per year ≤40 years | 0.99 (0.95 to 1.04) | 0.79 |

| Age at ARDS diagnosis, per year >40 years | 0.97 (0.93 to 1.02) | 0.28 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, per point | 0.75 (0.56 to 0.99) | 0.05 |

| Functional Comorbidity Index, per point | 0.93 (0.72 to 1.20) | 0.55 |

| Model 2: ICU and discharge variables | ||

| Mechanical ventilation, per day ≤5 days | 0.66 (0.54 to 0.81) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation, per day >5 days | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) | 0.22 |

| Discharge to rehabilitation or other healthcare facility | 0.41 (0.21 to 0.78) | 0.01 |

| Model 3: final multivariable model | ||

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, per point | 0.77 (0.59 to 0.99) | 0.04 |

| Mechanical ventilation, per day ≤5 days | 0.67 (0.55 to 0.82) | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation, per day >5 days | 1.02 (0.99 to 1.05) | 0.20 |

| Discharge to rehabilitation or other healthcare facility | 0.49 (0.26 to 0.93) | 0.03 |

HR calculated using Fine and Grey regression models, with a HR <1 indicating a slower time to return to work. To build multivariable models, covariates having univariable associations at p≤0.20 with the primary outcome (online supplementary eTable 1) were included in multivariable models. To prevent overfitting of the multivariable regression models, submodels were created, involving baseline patient variables (model 1) and ICU and hospital discharge variables (model 2). In these sub-models, multicollinearity was observed between APACHE II score, mean daily SOFA score, duration of mechanical ventilation and hospital LOS and addressed by omitting the non-significant variables (APACHE II, SOFA and hospital LOS) from the final model. Remaining variables from models 1 and 2 with an association of p≤0.20 were subsequently included in the final multivariable model (model 3). APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; LOS, length of stay; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

Figure 2.

Estimated adjusted cumulative incidence of return to work after ARDS, among survivors who were employed prior to ARDS. Estimates are based on the median duration of mechanical ventilation duration (ie, 9 days) and adjusted for all covariates in the final multivariable model (table 2). ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Estimated lost earnings after ARDS

By 5-year post-ARDS follow-up, 49 of 64 (77%) survivors had incurred any estimated lost earnings, with a 5-year cumulative mean (SD) total of $US180 221 ($US 110 285) (table 3). Not working due to disability status accounted for 55% of cumulative estimated lost earnings, while unemployment accounted for 31%, and a decrease in work hours from baseline (eg, change from full-time to part-time) accounted for 14%. Finally, the post-hoc sensitivity analyses of lost earnings were similar to the primary analysis (Online supplementary file 1).

Table 3.

Estimated lost earnings following ARDS (n=67)*

| Follow-up time point after ARDS | Year 1† | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| n (%) | Lost earnings, US$ | n (%) | Lost earnings, US$ | n (%) | Lost earnings, US$ | n (%) | Lost earnings, US$ | n (%) | Lost earnings, US$ | |

| Employment status leading to lost earnings‡ | ||||||||||

| Working less than before ARDS, US$ | 13 (19%) | 264 197 | 13 (19%) | 307 556 | 9 (13%) | 240 593 | 13 (19%) | 204 110 | 9 (13%) | 211 991 |

| Receiving disability, US$ | 18 (27%) | 817 812 | 20 (30%) | 946 214 | 20 (30%) | 975 399 | 20 (30%) | 1 100 536 | 21 (31%) | 1 124 516 |

| Unemployed, US$ | 14 (21%) | 643 929 | 15 (22%) | 644 999 | 15 (22%) | 682 008 | 11 (16%) | 447 192 | 9 (13%) | 360 382 |

| Total per year, US$ | 1 725 938 | 1 898 768 | 1 898 000 | 1 751 838 | 1 696 889 | |||||

| Mean (SD) per year, US$§ | 38 354 (21 533) | 39 558 (21 857) | 43 136 (23 189) | 40 740 (24 600) | 43 510 (25 753) | |||||

| Cumulative over time, US$ | 1 725 938 | 3 624 706 | 5 522 706 | 7 274 544 | 8 971 433 | |||||

| Mean (SD) cumulative over time, US$§¶ | 38 354 (21 533) | 74 808 (43 010) | 111 810 (63 062) | 146 343 (86 189) | 180 221 (110 285) | |||||

All values represent estimated lost earnings in US dollars. Includes only study participants with full-time or part-time work before ARDS. Annual estimates based on pre-ARDS hours working and age-based and gender-based estimates of hourly wages from the Bureau of Labour statistics. Based on this earnings estimation, patients reporting full-time (n=54 of 67, 81%) and part-time (n=13 of 67, 19%) work, respectively, had US$2 941 296 (mean (SD) per person, US$54 468 [US$17 146]) and US$260 350 (US$20 027 [US$9995]) of estimated annual earnings immediately before ARDS.

Determined from patient-reported employment status at the 2-year initial follow-up survey. Patients reporting return to work by 1 year were assumed to have obtained employment status similar to their 2-year status (if employed at 2 years) or baseline status (if not employed at 2 years). If return to work did not occur by 1 year, employment status category was based on year 2 employment status.

Survivors ‘Working less than before ARDS’ were working following ARDS, but reporting less hours than their baseline work. At year 1, 3 of 18 (17%) survivors receiving disability were working any hours per week, while at years 2, 3, 4 and 5, 100% reported 0 hours of work per week, and therefore had US$0 of estimated potential earnings. At years 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, retired, unknown employment status or dead subjects represented 2 (3%), 3 (4%), 5 (7%), 7 (10%) and 9 (12%) of participants, respectively, and were assumed to have US$0 estimated earnings or estimated lost earnings.

Per non-retired survivor attaining any estimated lost earnings at this time point.

At years 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5, the cumulative proportion of survivors accruing estimated lost earnings equaled 67% (45 of 67 survivors), 75% (50 of 67), 75% (50 of 67), 77% (50 of 65) and 77% (49 of 64). The mean cumulative lost earnings over time represents average lost earnings accrued by these survivors, and hence does not equal the sum of the mean annual lost earnings, which is the average lost earnings for survivors during that year alone.

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

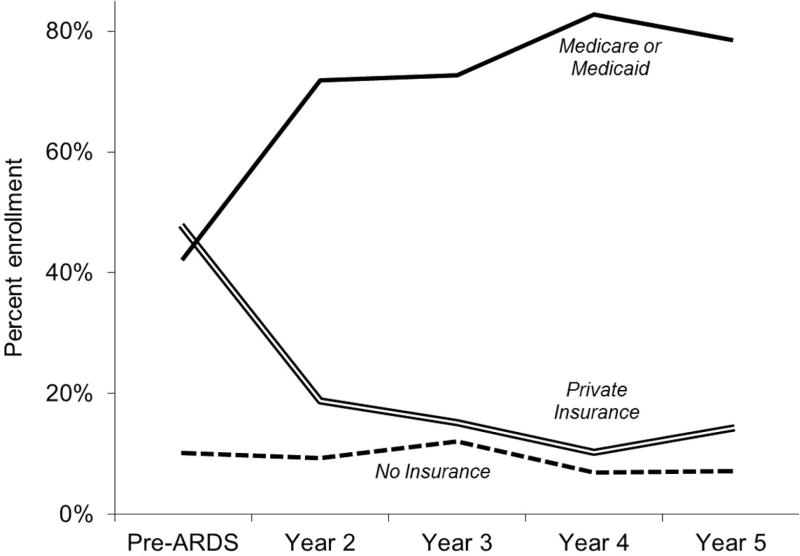

Healthcare coverage

At baseline, prior to ARDS, healthcare coverage among survivors <65 years old at the time was as follows: 47% private insurance; 42% government-funded (all Medicaid) and 10% no coverage. At each post-ARDS follow-up time point, survivors <65 years old who were jobless and not retired demonstrated a marked decline in private insurance enrolment (33% absolute reduction over 5-year follow-up) and a concomitant rise in government-funded coverage (37% absolute increase; Medicare increase 29% and Medicaid increase 8%), and little change in no coverage status (3% absolute reduction) (figure 3). Conversely, survivors <65 years old working at each follow-up time point exhibited a rise in private health insurance enrolment (17% absolute increase over 5 years) and decline in government-funded coverage (10% absolute reduction; Medicare 12% increase and Medicaid 22% decline) and no coverage (6% absolute reduction).

Figure 3.

Primary healthcare coverage among survivors employed prior to ARDS, and <65 years old, jobless and non-retired at each follow-up time point. Baseline healthcare coverage was known for 59 of 63 (94%) survivors who were employed and <65 years old prior to ARDS. At follow-up years 2, 3, 4, and 5, healthcare coverage was known for 61 of 63 (97%), 61 of 62 (98%), 56 of 57 (98%) and 54 of 56 (96%) of previously employed survivors who were <65 years old. ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Quality of life and hospitalisations

As compared with survivors who were working at 2–5 year post-ARDS follow-up, those who were not working consistently reported worse physical health-related quality of life scores and had experienced more frequent hospitalisations in the prior year (online supplementary eTable 2).

DISCUSSION

In this multisite, 5-year prospective, longitudinal cohort study of 67 long-term ARDS survivors who were working prior to ARDS, delayed return to work was common, with nearly one-half and one-third never returning to work by 2-year and 5-year follow-up, respectively. Among the survivors who had not returned to work by 1-year follow-up, 65% never returned to work over 5-year follow-up. Comorbidity burden prior to ARDS, longer duration of mechanical ventilation (up to 5 days), and discharge to a healthcare facility were associated with slower return to work, which resulted in substantial estimated lost earnings, averaging almost US$200 000 over 5 years. Moreover, compared with pre-ARDS status, joblessness was associated with a 70% relative decrease in private health insurance and near doubling of government-funded coverage (Medicare and Medicaid).

In our cohort, the cumulative proportion of survivors ever returning to work 1, 2 and 5 years following ARDS were 49%, 55% and 69%, respectively. Our 49% 1-year return to work rate was consistent with other US ARDS studies7,29 and a recent US study of general ICU survivors.30 However, our 1-year (49%) and 5-year (69%) rates were lower than the 63% (40 of 64 previously employed survivors) and 92% (49 of 53 survivors), respectively, reported in a Canadian ARDS study,6 with differences in temporal, socioeconomic or geographic factors potentially explaining these differences.

Notably, 38% of survivors who successfully returned to work during follow-up were subsequently unemployed, on disability, retired or dead at 5-year follow-up. Almost two-thirds of survivors who had not returned to work at 1 year never returned to work, and, among those who did return to work, only 50% were working at 5-year follow-up. As many of these survivors subsequently lost their jobs due to health-related issues or disability, these findings suggest that returning to work after ARDS is not only challenging for survivors, but may be short-lived.

In our study, age was not associated with the timing of return to work, despite prior non-ICU studies demonstrating worse employment outcomes after illness in older patients.31,32 This difference in findings may be explained by our survivor population being relatively young (median: 46 years old). Additionally, we found no association between years of education and delayed return to work, similar to a recent study of 1-year employment outcomes in general ICU survivors.30

Regarding variables associated with delayed return to work, the Charlson Comorbidity Index and discharge to a healthcare facility (vs home) were both significant. In our cohort, compared with an ARDS survivor with no baseline comorbidities who required 9 days of mechanical ventilation, discharge to a healthcare facility (vs home) is associated with an absolute incremental reduction in 5-year return to work of 24%–26%; and if the survivor had two comorbidities, there was an added absolute incremental reduction of 16%–18%. These variables, though non-modifiable, may aid in identifying survivors at highest risk of delayed return to work, which can subsequently help in determining the best target populations for future interventions.

We also note that for each additional day of mechanical ventilation (up to 5 days), survivors had a significant delay in return to work. The lack of a further delay in return to work beyond 5 days of mechanical ventilation may reflect surpassing a threshold of severity of illness beyond which survivors’ employment outcomes do not worsen.

Despite these risk factors, the precise mechanism for delayed return to work after ARDS remains unknown. Earlier studies of survivors of ARDS33,34 and critical illness30 demonstrated that joblessness is associated with depression and cognitive impairment. Additionally, we found that survivors who were not working reported worse physical quality of life scores. However, given the cross-sectional nature of these associations, their directionality is unclear. Nevertheless, the baseline risk factors identified in our study may predispose patients to depression35 and cognitive dysfunction,36 which may be mediators of baseline and hospital variables’ associations with delayed return to work after ARDS.

Additionally, we inferred that non-retired survivors not returning to pre-ARDS work status incurred estimated lost earnings of US$38 354–US$43 510 annually and US$180 221 over 5-year follow-up. These estimates are similar to, or greater than, studies of survivors of traumatic brain injury37 and ischaemic stroke.38 Moreover, estimated lost earnings rose annually, due, in part, to persistent unemployment or subsequent job loss of survivors who had initially returned to work after hospital discharge.

From a health insurance perspective, over time, jobless, non-retired survivors experienced a marked decline in private insurance and rise in government-funded (ie, Medicare or Medicaid) healthcare coverage. Notably, jobless survivors <65 years old had increased from 0% to 29% in Medicare enrolment, suggesting that post-ARDS disability contributed to this transition to government-funded healthcare. This payer shift affects survivors’ access to healthcare, out-of-pocket expenditures and overall healthcare costs,17,39,40 the magnitude of which represents an interesting area of future investigation.

Strengths and limitations

This study has several strengths, including its 5-year longitudinal follow-up period, high patient retention, estimation of lost earnings and evaluation of changes in health insurance status. Nevertheless, this study has several potential limitations. First, the study may have been underpowered to detect all potentially important patient-related and hospital-related associations with delayed return to work. Second, as an observational study, we cannot attribute a cause–effect association of the risk factors with delay in return to work; there may have been unmeasured confounders affecting these associations. Nevertheless, these findings may be used to inform the design and evaluation of interventions for reducing joblessness after critical illness. Third, the generalisability of our findings to other ICU survivor populations may be limited. However, we observed 1 year return to work rates which paralleled those of other US post-ARDS studies,7,29 including a national study enrolling patients from 41 hospitals.7 Subsequent larger multisite studies are needed. Fourth, lost earnings were calculated based on estimated, rather than actual, earnings. However, we performed this estimation using age- and sex-matched Bureau of Labor Statistics data in order to produce estimates that were more nationally representative, rather than specific to this study cohort, thus, enhancing generalisability. Fifth, our study involved a US population and use of US-specific labour data for estimating wages. While these lost earnings estimations may not be generalisable outside of the USA, they provide an important foundation for future research in other international cohorts. Finally, we may have overestimated the financial impact experienced by survivors as we did not incorporate possible compensatory income, such as disability benefits or worker’s compensation. However, such issues may have been counterbalanced by not accounting for potential lost earnings incurred by family members and other informal caregivers. These issues represent important areas for future research.

CONCLUSION

In our multisite study of return to work after ARDS, approximately one-third of long-term survivors never returned to work and almost one-half were unemployed or receiving disability at 5 year follow-up. Moreover, among survivors not working 1 year after ARDS, only one-third ever returned to work over subsequent 4-year follow-up. Delayed return to work resulted in lost earnings for ~80% of survivors with a 5-year cumulative average estimated at nearly US$200 000. Finally, survivors experiencing these delays experienced a 70% relative decrease in private insurance, and doubling in government-issued healthcare coverage. These major economic implications emphasise the need for designing and evaluating occupation-based rehabilitation interventions for at-risk ARDS survivors.

Supplementary Material

Key messages.

What is the key question?

-

▶

What are the risk factors, lost earnings and shifts in healthcare coverage associated with joblessness over 5-year prospective, longitudinal follow-up in long-term acute respiratory distress syndrome survivors?

What is the bottom line?

-

▶

Prolonged joblessness is common over 5-year follow-up. Delayed return to work is associated with greater baseline comorbidity, a longer duration of mechanical ventilation and discharge to a healthcare facility (vs home), and is accompanied by substantial lost earnings and a shift toward government-funded healthcare coverage.

Why read on?

-

▶

In addition to its negative long-term medical consequences, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) results in substantial lost earnings and shifts toward government-funded healthcare coverage, highlighting a need for designing and evaluating vocation-based rehabilitation interventions to help ARDS survivors return to work.

Acknowledgments

Funding BBK is supported by a grant through the UCLA Clinical Translational Research Institute (CTSI) and the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000124&UL1TR001881). This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (P050HL73994, R01HL088045, and K24HL088551), along with the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) (UL1 TR 000424)06).

Footnotes

Correction notice This article has been corrected since it was published Online First. The ’Trial registration number’ has been removed from the abstract. This is an observational study and not linked to a clinical trial.

Contributors DMN and BBK: contributed to conception and design of the manuscript; are responsible for the overall content as guarantors; and affirm that the manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained. BBK, KAS, RKL, VDD, EC, TMvW and DMN: contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. BBK: drafted the manuscript and all other authors critically revised it for important intellectual content. All authors: gave final approval of the manuscript version to be published.

Competing interests None declared.

Ethics approval The University’s Institutional Review Boards of all participating sites approved this study.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Spragg RG, Bernard GR, Checkley W, et al. Beyond mortality: future clinical research in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:1121–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201001-0024WS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iwashyna TJ. Survivorship will be the defining challenge of critical care in the 21st century. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:204–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-153-3-201008030-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Desai SV, Law TJ, Needham DM. Long-term complications of critical care. Crit Care Med. 2011;39:371–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181fd66e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Needham DM, Dinglas VD, Morris PE, et al. Physical and cognitive performance of patients with acute lung injury 1 year after initial trophic versus full enteral feeding. EDEN trial follow-up. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:567–76. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201304-0651OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bienvenu OJ, Colantuoni E, Mendez-Tellez PA, et al. Cooccurrence of and remission from general anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after acute lung injury: a 2-year longitudinal study. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:642–53. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herridge MS, Tansey CM, Matté A, et al. Functional disability 5 years after acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1293–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Needham DM, Dinglas VD, Bienvenu OJ, et al. One year outcomes in patients with acute lung injury randomised to initial trophic or full enteral feeding: prospective follow-up of EDEN randomised trial. BMJ. 2013;346:f1532. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f1532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coopersmith CM, Wunsch H, Fink MP, et al. A comparison of critical care research funding and the financial burden of critical illness in the United States. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:1072–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823c8d03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Briand C, Durand MJ, St-Arnaud L, et al. Work and mental health: learning from return-to-work rehabilitation programs designed for workers with musculoskeletal disorders. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2007;30:444–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan F, Ng L, Turner-Stokes L. Effectiveness of vocational rehabilitation intervention on the return to work and employment of persons with multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD007256. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007256.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Selander J, Marnetoft SU, Bergroth A, et al. Return to work following vocational rehabilitation for neck, back and shoulder problems: risk factors reviewed. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24:704–12. doi: 10.1080/09638280210124284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turkstra LS, Flora TL. Compensating for executive function impairments after TBI: a single case study of functional intervention. J Commun Disord. 2002;35:467–82. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9924(02)00118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernard GR, Artigas A, Brigham KL, et al. The American-European Consensus Conference on ARDS. Definitions, mechanisms, relevant outcomes, and clinical trial coordination. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:818–24. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.3.7509706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, Thompson BT, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin definition. JAMA. 2012;307:2526–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Radford K, Phillips J, Drummond A, et al. Return to work after traumatic brain injury: cohort comparison and economic evaluation. Brain Inj. 2013;27:507–20. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2013.766929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corso P, Finkelstein E, Miller T, et al. Incidence and lifetime costs of injuries in the United States. Inj Prev. 2006;12:212–8. doi: 10.1136/ip.2005.010983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruhl AP, Huang M, Colantuoni E, et al. Healthcare resource use and costs in long-term survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome: a 5-Year longitudinal cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:196–204. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D’Hoore W, Sicotte C, Tilquin C. Risk adjustment in outcome assessment: the Charlson comorbidity index. Methods Inf Med. 1993;32:382–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Groll DL, Heyland DK, Caeser M, et al. Assessment of long-term physical function in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients: comparison of the Charlson comorbidity index and the functional comorbidity Index. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2006;85:574–81. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000223220.91914.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan E, Gifford JM, Chandolu S, et al. The functional comorbidity index had high interrater reliability in patients with acute lung injury. BMC Anesthesiol. 2012;12:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-12-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APAC HE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13:818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, et al. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the working group on sepsis-related problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707. doi: 10.1007/BF01709751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol Methods. 2002;7:147–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diggle P. Analysis of longitudinal data. 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vittinghoff E, Glidden DV, Shiboski SC, et al. Regression methods in biostatistics linear, logistic, survival, and repeated measures models. statistics for biology and health. 2. Boston, MA: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans MJ, Harrell FE, et al. Prognostic modeling with logistic regression analysis: in search of a sensible strategy in small data sets. Med Decis Making. 2001;21:45–56. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoenfeld D. Partial residuals for the proportional hazards regression model. Biometrika. 1982;69:239–41. [Google Scholar]

- 29.McHugh LG, Milberg JA, Whitcomb ME, et al. Recovery of function in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;150:90–4. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.150.1.8025779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norman BC, Jackson JC, Graves JA, et al. Employment outcomes after critical illness: an analysis of the bringing to light the risk factors and incidence of neuropsychological dysfunction in icu survivors cohort. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:2003–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Boer AG, Verbeek JH, Spelten ER, et al. Work ability and return-to-work in cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:1342–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hess DW, Ripley DL, McKinley WO, et al. Predictors for return to work after spinal cord injury: a 3-year multicenter analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:359–63. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(00)90084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adhikari NKJ, Tansey CM, McAndrews MP, et al. Self-reported depressive symptoms and memory complaints in survivors five years after ARDS. Chest. 2011;140:1484–93. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rothenhäusler HB, Ehrentraut S, Stoll C, et al. The relationship between cognitive performance and employment and health status in long-term survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome: results of an exploratory study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23:90–6. doi: 10.1016/s0163-8343(01)00123-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hopkins RO, Key CW, Suchyta MR, et al. Risk factors for depression and anxiety in survivors of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:147–55. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilcox ME, Brummel NE, Archer K, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in ICU patients: risk factors, predictors, and rehabilitation interventions. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:S81–98. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a16946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnstone B, Mount D, Schopp LH. Financial and vocational outcomes 1 year after traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2003;84:238–41. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2003.50097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor TN, Davis PH, Torner JC, et al. Lifetime cost of stroke in the United States. Stroke. 1996;27:1459–66. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.9.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruhl AP, Lord RK, Panek JA, et al. Health care resource use and costs of two-year survivors of acute lung injury. An observational cohort study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:392–401. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201409-422OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruhl AP, Huang M, Colantuoni E, et al. Healthcare utilization and costs in ARDS survivors: a 1-year longitudinal national US multicenter study. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43:980–91. doi: 10.1007/s00134-017-4827-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.