Summary

We aimed to identify biomarkers to guide the decision to add selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) to psychological treatment for social anxiety disorder (SAD). Forty-eight patients with SAD underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging and collection of clinical and demographic variables before treatment with cognitive–behavioural therapy, combined on a double-blind basis with either escitalopram or placebo for 9 weeks. Pre-treatment neural reactivity to aversive faces in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), but not clinical/demographic variables, moderated clinical outcomes. Cross-validated individual-level predictions accurately identified 81% of responders/non-responders. Dorsal ACC reactivity is thus a potential biomarker for SAD treatment selection.

Declaration of interest

None.

Keywords: Functional magnetic resonance imaging, anxiety, prediction, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, cognitive–behavioural therapy, social phobia

Cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) is often combined with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) to treat depression1 and anxiety,2 but the additional efficacy of this combination is debated.3,4 Indeed, for some patients, CBT may be sufficient, and adding further treatment will not increase the effect. Adherence to pharmacotherapy may also be reduced by patient preference and SSRI side-effects. Refined models of treatment selection for individual patients are therefore needed. Indeed, basing treatment choice on personal characteristics of the individual patient is one of the goals of precision psychiatry.5 A recent study showed that pre-treatment brain metabolism could differentially predict outcomes of CBT and SSRI monotherapies for depression,6 indicating the potential of using neuroimaging biomarkers for such treatment selection. However, it is not known whether this extends to combination therapies (SSRI + CBT) and anxiety disorders. Hence, we sought to conceptually replicate these findings6 to identify biomarkers that could guide decisions on whether to add SSRI medication to CBT in patients with social anxiety disorder (SAD). Based on previous treatment response prediction studies,7,8 we hypothesised that activity in the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) would be predictive of treatment response.

Method

This study relates baseline neural, demographic, and clinical data to treatment outcome reported in a previous double-blind randomised controlled trial.3 For a detailed description of participant recruitment, treatment, demographic/clinical measures, neuroimaging pre-processing and first-level analyses, refer to the original publication.3 Briefly, 48 patients with SAD (mean ± SD age 33.2 ± 8.8 years, 24 women) were treated for 9 weeks with internet-based CBT, combined either with the SSRI escitalopram (20 mg) or a pill placebo. The primary outcome measures were treatment response category as measured by the Clinical Global Impression Improvement scale (responders ≤ 2; non-responders ≥ 3) and symptom improvement assessed with the clinician-administered Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale.9 The participants also underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging during a disorder-relevant emotional face-matching task with shape-matching control trials,3 and were assessed regarding demographic/clinical variables age, gender, symptom severity, duration and subtype of SAD, comorbidity, previous treatment, and depression level.

To examine how pre-treatment brain reactivity (faces minus shapes) and demographic and clinical variables moderated the effect of the treatment group (SSRI + CBT or placebo + CBT) on clinical response category and symptom improvement, we conducted separate regression analyses for each outcome measure and for each variable of interest using the glm function in R.10 Each voxel and demographic/clinical predictor variable was thus entered into a separate regression model, together with the treatment group and interactions between the variable and the treatment group. The interaction term was our focus here, as it is a measure of differential prediction of clinical outcome in the two treatment groups (i.e. moderation). The threshold for voxel-wise brain analyses was set at P < 0.005 with a cluster size >10 voxels, to balance type I and type II errors.11 For demographic and clinical variables, we used the standard P < 0.05 threshold for significance. It should be noted that, in order to be stringent, we required moderation of both outcome measures at these statistical thresholds.

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board, Uppsala, and the Medical Products Agency in Sweden. All participants were fully informed about the study aims and procedures and gave written informed consent prior to inclusion.

Results

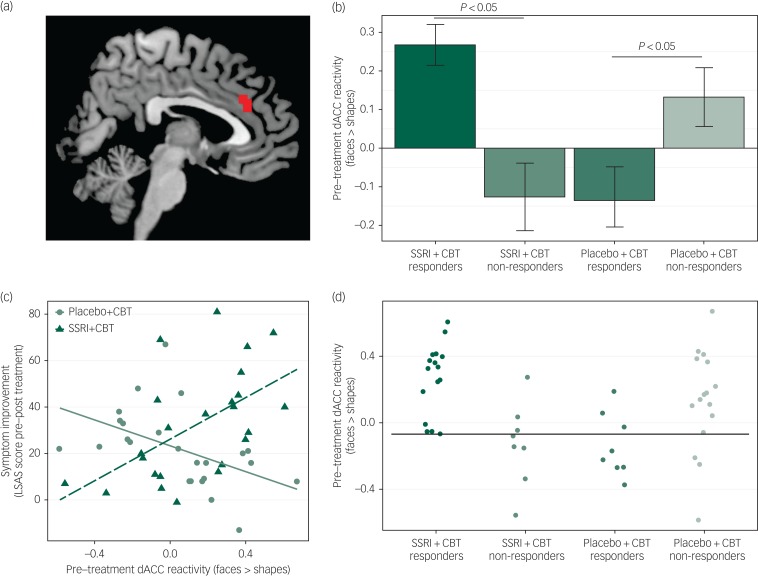

Pre-treatment neural reactivity (faces > shapes) in the dorsal ACC (dACC; cluster size 648 mm3) differentially predicted both the clinical response and the symptom improvement outcome variables in the two treatment groups (Figure 1). Pre-treatment dACC reactivity was higher in responders (n = 16) than in non-responders (n = 8) (t(22) = 4.06, P = 0.0005) in the SSRI + CBT group, whereas the reverse was true in the placebo + CBT group, i.e. there was lower reactivity in responders (n = 8) than in non-responders (n = 16) (t(22) = 2.25, P = 0.035) (Figure 1b). Accordingly, higher pre-treatment dACC reactivity predicted symptom improvement in the SSRI + CBT group (r(22) = 0.59, P = 0.002), but worse outcome in the placebo + CBT group (r(22) = −0.52, P = 0.009) (Figure 1c). No other neural or demographic/clinical moderating variables were identified.

Fig. 1.

(a) Cluster in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) where pre-treatment neural reactivity to an emotional face-matching task moderated the effect of treatment group on clinical response category and continuous symptom improvement. The cluster is overlaid on a standard anatomical brain image. (b) Bar plot illustrating that responders to SSRI + CBT had increased pre-treatment dACC reactivity (faces > shapes) relative to non-responders, whereas responders to placebo + CBT had reduced dACC reactivity as compared to non-responders. Error bars denote standard error of the mean. (c) Differential correlations between pre-treatment reactivity in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) and symptom improvement [change (pre–post) on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS)] between groups. In the SSRI + CBT group, there was a positive correlation and in the placebo + CBT group a negative correlation. (d) Illustration of treatment response predictions at the individual patient level based on pre-treatment dACC reactivity (faces > shapes). The horizontal black line denotes the optimal threshold, maximizing classification accuracy. SSRI + CBT responders and placebo + CBT non-responders above the threshold and SSRI + CBT non-responders and placebo + CBT responders below the threshold were correctly classified, in total 81%.

The predictive accuracy of pre-treatment dACC reactivity for individual patients was examined by applying a reactivity threshold (β = 0) based on mean β values (faces minus shapes) from the dACC cluster, i.e. individuals with high dACC reactivity (β > 0) were predicted to respond to SSRI + CBT but not to placebo + CBT, and vice versa for individuals with low dACC reactivity. Accuracy was calculated as the ratio of participants correctly identified as responders or non-responders. This arbitrary threshold resulted in 75% accurate predictions (high reactivity: 86%; low reactivity: 60%). We also calculated the optimal reactivity threshold (β = −0.068) using leave-one-subject-out cross-validation, to maximise predictive accuracy in this sample while at the same time taking generalisation to other samples into account, which resulted in 81% accurate predictions (high reactivity: 83%; low reactivity: 77%) (Figure 1d).

Discussion

Pre-treatment neural activity to emotional faces in the dACC predicted clinical outcome to CBT when combined with either an SSRI or placebo. Specifically, highly reactive individuals were more likely to respond to SSRI-augmented CBT but not to placebo-paired CBT; conversely, lower reactivity was associated with response to combined placebo + CBT and non-response to SSRI + CBT. These results are in line with a recent report on unmedicated SAD patients showing lower pre-treatment dACC reactivity in CBT responders than in non-responders,8 and also with previous studies indicating that neural reactivity in the ACC is predictive of treatment response in depression and anxiety disorders.7,12 The dACC is hyper-reactive in SAD patients compared with healthy controls13 and has a key role in many functions that are affected by SAD, including fear expression and emotion regulation.14 The interaction between dACC reactivity and treatment (SSRI + CBT or CBT) may thus suggest that the two treatments differentially tax such functions. Contrary to our hypothesis, pre-treatment amygdala reactivity did not predict treatment response. This may be somewhat surprising given previous reports of a change–change relationship between reduced amygdala reactivity with treatment and symptom improvement, which was also observed in the current sample.3 Superior treatment prediction from neural as opposed to demographic/clinical variables is, however, consistent with previous studies on monotherapy.7,8 Among the limitations, it should be noted that the sample size was small, and the results should be regarded as tentative until replicated. In conclusion, pre-treatment dACC reactivity, but not demographic/clinical characteristics, predicted who would benefit from adding SSRI to CBT. In line with the goals of precision psychiatry, these results support dACC reactivity as a putative biomarker for treatment selection at the individual level, and suggest that brain imaging could improve clinical decision-making.

Acknowledgements

We thank all study participants.

Funding

This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council, the Swedish Brain Foundation, Riksbankens Jubileumsfond – the Swedish Foundation for Humanities and Social Sciences, and the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare. A.F. was supported by a postdoctoral scholarship from the Swedish Society for Medical Research. The funders had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review or approval of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Gelenberg AJ, Freeman MP, Markowitz JC, Rosenbaum JF, Thase ME, Trivedi MH, et al. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with major depressive disorder third edition. Am J Psychiatry 2010; 167: 1–3, 9–11, 13–118.20068118 [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Social Anxiety Disorder: Recognition, Assessment and Treatment. CG159. NICE, 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gingnell M, Frick A, Engman J, Alaie I, Björkstrand J, Faria V, et al. Combining escitalopram and cognitive–behavioural therapy for social anxiety disorder: randomised controlled fMRI trial. Br J Psychiatry 2016; 209: 229–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordahl HM, Vogel PA, Morken G, Stiles TC, Sandvik P, Wells A. Paroxetine, cognitive therapy or their combination in the treatment of social anxiety disorder with and without avoidant personality disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Psychother Psychosom 2016; 85: 346–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandes BS, Williams LM, Steiner J, Leboyer M, Carvalho AF, Berk M. The new field of ‘precision psychiatry’. BMC Med 2017; 15: 80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McGrath CL, Kelley ME, Holtzheimer PE, Dunlop BW, Craighead WE, Franco AR, et al. Toward a neuroimaging treatment selection biomarker for major depressive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 2013; 70: 821–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lueken U, Zierhut KC, Hahn T, Straube B, Kircher T, Reif A, et al. Neurobiological markers predicting treatment response in anxiety disorders: a systematic review and implications for clinical application. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016; 66: 143–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Månsson KNT, Frick A, Boraxbekk C-J, Marquand AF, Williams SCR, Carlbring P, et al. Predicting long-term outcome of internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder using fMRI and support vector machine learning. Transl Psychiatry 2015; 5: e530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liebowitz MR. Social phobia. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry 1987; 22: 141–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2017. (https://www.R-project.org/). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lieberman MD, Cunningham WA. Type I and type II error concerns in fMRI research: re-balancing the scale. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2009; 4: 423–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu CHY, Steiner H, Costafreda SG. Predictive neural biomarkers of clinical response in depression: a meta-analysis of functional and structural neuroimaging studies of pharmacological and psychological therapies. Neurobiol Dis 2013; 52: 75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brühl AB, Delsignore A, Komossa K, Weidt S. Neuroimaging in social anxiety disorder—A meta-analytic review resulting in a new neurofunctional model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2014; 47: 260–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Etkin A, Egner T, Kalisch R. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends Cogn Sci 2011; 15: 85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]