Abstract

Background

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is a leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide. The relationships of alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) enzymes, encoded by the genes ADH1 (1A), ADH1B (ADH2), ADH1C (ADH3), ADH4, ADH5, ADH6, and ADH7, with NSCLC have not been studied. The aim of this study was to explore the associations between NSCLC prognosis and the expression patterns of ADH family members.

Material/Methods

The online resource Metabolic gEne RApid Visualizer was used to assess the expression patterns of ADH family members in normal and primary lung tumor tissues. The GeneMANIA plugin of Cytoscape software and STRING website were used to evaluate the relationships of the 7 ADH family members at the gene and protein levels. Gene ontology enrichment analysis and KEGG pathway analysis were performed using DAVID. The online website Kaplan-Meier Plotter was used to construct survival curves between NSCLC and ADH isoforms.

Results

The prognosis of patients with high expression levels of the ADH1B, ADH1C, ADH4, and ADH5 genes was better than those with low expression in adenocarcinoma and all (containing adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer) histological types (all P<0.05). Low expression of ADH7 was associated with a better prognosis in patients with both the adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer histological types (P=9e-05). Moreover, expression of ADH family members was associated with smoking status, clinical stage, and chemotherapy status.

Conclusions

ADH1B, ADH1C, ADH4, ADH5, and ADH7 appear to be useful biomarkers for the prognosis of NSCLC patients.

MeSH Keywords: Alcohol Dehydrogenase; Biological Markers; Carcinoma, Non-Small-Cell Lung; Multigene Family; Prognosis

Background

Lung cancer, which is a main cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide [1,2], is classified into 3 major histologic subtypes: adenocarcinoma, squamous carcinoma, and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with the latter being the major histological subtype. In 2012, there were 1 800 000 new lung cancer cases, which accounted for 13% of the total number of cancer diagnoses [3]. As compared with other high-onset cancers, the 5-year survival rate of lung cancer remains as low as 15% [4]. The conventional treatment for lung cancer is whole-body chemotherapy with cisplatin, but the efficacy of such regimens is limited [5]. Although several biomarkers have been reported with lung cancer prognosis, including ELF3 [6], miRNA-135 [7], miRNA-34 [8], the survival status of lung cancer patients are still not satisfactory. Thus, further studies focusing on the mechanisms of initiation and progression, and the identification of prognostic molecular markers are of crucial significance.

The members of the alcoholic dehydrogenase (ADH) family include 7 enzymes, ADH1–7. In humans, these 7 ADH enzyme-encoding genes (ADH7, ADH1C, ADH1B, ADH1A, ADH6, ADH4, and ADH5) are clustered within a small region of chromosome 4 (4q21–24) in a head-to-tail array that is approximately 370 kb in length [9,10]. The transformation of ethanol into its carcinogenic metabolite, acetaldehyde, is especially important for the elimination of ADH1 in the liver [10]. A significant association was found between gastric cancer risk and a common 3′-untranslated region flanking a single-nucleotide polymorphism near rs1230025 of ADH1A [11]. The most important function-associated polymorphism in ADH is considered to be ADH1B Arg48His (rs1229984) [12]. Rs17033 of ADH1B is related to the risk of gastric cancer and smoking may further affect the role of rs671 [11]. Positive responses of ADH1B*3 and alcohol dependence have been found in African and Native American populations [13,14]. The interactions between ADH1B + 3170A> G and ADH1C + 13044A> G are related to environmental factors as well as lifestyle factors, such as drinking and smoking [15]. The ADH1B + 3170A> G and ADH1C + 13044A> G single-nucleotide polymorphisms are associated with an increased risk of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), and can be used as biomarkers for high-risk South Korean populations [16]. The latest evidence suggests that the cancer risk in Africans and Asians may be caused by the polymorphism ADH1C Ile350Val (rs698) [17]. Candidate gene studies have reported that at least 4 functional ADH gene variants significantly affect the risk of alcohol dependence, namely rs1229984 (ADH2 * 2; Arg48His), rs2066702 (ADH2 * 3; Arg370Cys), rs1693482 (ADH3 * 2; Arg272Gln), and rs698 (ADH3 * 2; Ile350Va) [18]. The ADH1 and ADH4 enzymes may play roles in the development of retinol endocrine function in the mouse embryo [19]. Studies have shown that the human ADH5 gene can give rise to different carboxyl terminal proteins dependent on the transcriptional materials that produce variable splicing patterns [20]. As compared with other mammals, the deduced amino acid sequences of the gene products of ADH5 and ADH6 demonstrate a deficiency of ADH enzymatic activity [21]. Recent studies have found that early (pre-absorbed or first) alcohol metabolism changes are associated with the ADH7 mutation [22].

Members of the ADH gene family have been associated with various diseases, including alcoholism and cancers, but such relationships in NSCLC remain unclear. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the potential prognostic values of ADH family members for NSCLC to provide new clues for individualized treatments and better prognostic indicators for NSCLC patients.

Material and Methods

Data collection

In total, 1926 patient samples were classified according to the median and overall survival rates. Clinical data, including sex, smoking history, histology, AJCC stage, grade, success of surgery, radiotherapy, and applied chemotherapy for all NSCLC patients, were collected from 3 datasets: the Cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid (http://cabig.cancer.gov/, microarray samples are published in the caArray project), the Gene Expression Omnibus (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/), and the Cancer Genome Atlas (http://cancergenome.nih.gov).

Expression analysis of ADH family members

The online resource Metabolic gEne RApid Visualizer (http://merav.wi.mit.edu/; accessed on January 14, 2018) was used to identify ADH family genes. Five ADH family members were entered into the site to analyze the level of expression between them, but only 3 could be analyzed, as the other 2 were not identified [23].

Interaction and enrichment analysis of ADH family members

The GeneMAMIA plugin of Cytoscape software was used to analyze the relationship between the 5 genes [24,25] Moreover, the STRING online resource was used to analyze the biological interactions at the protein level of ADH family members [26]. Pearson correlation analysis of ADH family members was performed using R version 3.4.2 (https://www.r-project.org/). Finally, enrichment analysis was performed with the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery website (DAVID, version 6.7), which includes the Gene Ontology (GO) terms and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways [27,28].

Survival analysis of ADH family members

A database was created using the Kaplan–Meier Plotter (http://kmplot.com/analysis/) to determine the correlation between ADH family members at the mRNA level and prognosis of overall survival of NSCLC patients [29]. At present, the website contains data of breast cancer, lung cancer, ovarian cancer, gastric cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Results

Collection of patient data

In this study, Kaplan-Meier Plotter was used to analyze the medical records of 1926 lung cancer patients, so approval by the Ethics Committee was not needed because this study did not involve human participants or animals.

Expression analysis of ADH family members in normal and primary lung tumor tissues

The expression levels of the ADH family members in normal and primary lung tumor tissues varied, with only slight expression of ADH1A and ADH6 in both normal and primary lung tumor tissues, and ADH1C and ADH7 in lung primary tumor tissues. Other than ADH5, expression of other members was relatively high in normal lung tissues (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Expression levels of ADH family members in normal and primary lung tumor tissues. (A) Expression levels of ADH1A in normal and primary lung tumor tissues; (B) Expression levels of ADH1B in normal and primary lung tumor tissues; (C) Expression levels of ADH1C in normal and primary lung tumor tissues; (D) Expression levels of ADH4 in normal and primary lung tumor tissues; (E) Expression levels of ADH5 in normal and primary lung tumor tissues; (F) Expression levels of ADH6 in normal and primary lung tumor tissues; (G) Expression levels of ADH7 in normal and primary lung tumor tissues.

Interaction analysis of ADH family members at the gene and protein levels

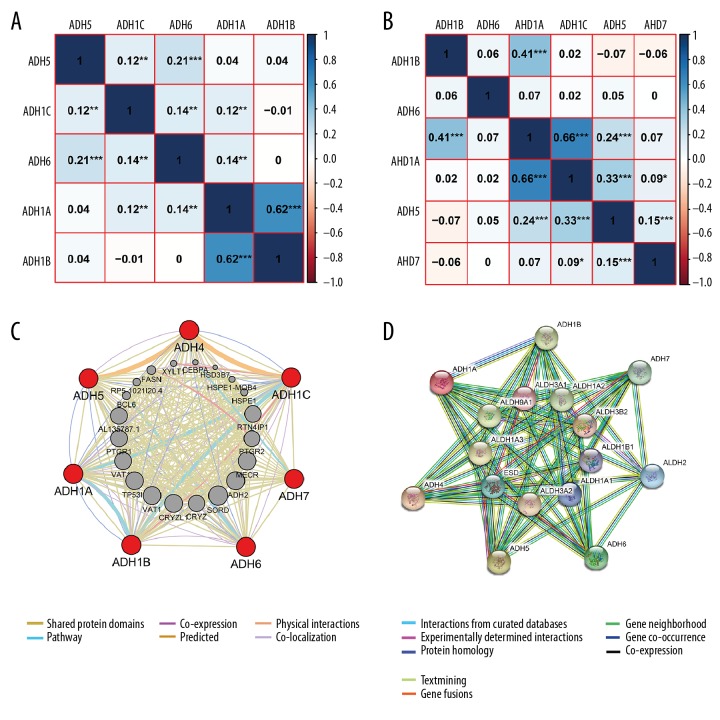

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted using expression data of ADH family members collected from the OncoLnc website (www.oncolnc.org/). In lung adenocarcinoma, ADH1A was significantly associated with ADH1B, ADH1C, and ADH6 (r=0.62, P<0.001; r=0.12, P<0.01; r=0.14, P<0.01, respectively), while ADH1C was significantly associated with ADH5 and ADH6 (r=0.12, P<0.01; r=0.14, P<0.01, respectively), and ADH5 was significantly associated with ADH6 (r=0.21, P<0.001, Figure 2A). In lung SCC, ADH1A was significantly associated with ADH1B, ADH1C, and ADH5 (r=0.41, P<0.001; r=0.66, P<0.001; r=0.24, P<0.001, respectively), and ADH1C was significantly associated with ADH5 and ADH7 (r=0.33, p<0.001; r=0.09, P<0.05, respectively). Detailed results are presented in Figure 2B.

Figure 2.

Interaction analysis of ADH family members. (A) Pearson correlation of ADH family members in lung adenocarcinoma; (B) Pearson correlation of ADH family members in lung SCC; (C) Gene-gene interaction network among ADH family members; (D) Protein-protein interaction network among ADH family members.

GeneMANIA was used to conduct correlation analysis of ADH family members at the gene level, which revealed relationships in pathways, shared protein domains, co-localization, and co-expression between ADH1A and ADH1B, as well as ADH1A and ADH1C (ADH3). There were relationships between ADH1C (ADH3) and ADH4 in co-expression, prediction, and shred protein domains. There were also relationships between ADH4 and ADH6 in co-localization, shared protein domains, and co-expression. There were shared protein domains between ADH4 and ADH7. In addition, there were relationships in co-expression and shared protein domains, and predicted relationships between ADH4 and ADH5. ADH1A and ADH7 had shared protein domains. ADH1A and ADH5 also shared protein domains and co-localization. Detailed results are presented in Figure 2C.

STRING analysis was conducted to identify interactions of ADH gene family members at the protein expression level. ADH1C was not recognized by STRING. ADH1A was shown to interact with ADH1B, ADH4, and ADH6 in regards to gene co-occurrence, text-mining, co-expression, and protein homology. ADH4 was found to interact with ADH6 and ADH7 in regards to gene co-occurrence, text-mining, co-expression, and protein homology. Detailed results are presented in Figure 2D.

Enrichment analysis of GO terms and KEGG pathways

Correlations among the 3 factors of smoking, clinical staging, and chemotherapy were also assessed among ADH gene family members. The results showed that smoking status was significantly associated with ADH1C (ADH3), ADH4, and ADH7 (P=0.017, 0.009, and 5E-04, respectively). Non-smoking status was significantly associated with ADH5 (P=0.0005), while ADH1B (ADH2) and ADH6 were significantly associated with both smoking and non-smoking status (P=0.012, 0.0002, 0.027, and 0.026, respectively). ADH1A (ADH1) was not significantly associated with smoking or non-smoking status (P=0.095 and 0.449, respectively, Table 1).

Table 1.

Correlation analysis between ADH family members and smoking status.

| Isoenzymes | Smoking status | Cases | HR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADH1A/ADH1 | Yes | 820 | 1.19 | 0.97–1.47 | 0.095 |

| No | 205 | 1.24 | 0.71–2.16 | 0.449 | |

| ADH1B/ADH2 | Yes | 820 | 0.77 | 0.62–0.94 | 0.012 |

| No | 205 | 0.33 | 0.18–0.61 | 0.0002 | |

| ADH1C/ADH3 | Yes | 820 | 0.72 | 0.58–0.88 | 0.017 |

| No | 205 | 0.84 | 0.38–1.88 | 0.672 | |

| ADH4 | Yes | 300 | 0.57 | 0.37–0.87 | 0.009 |

| No | 141 | 0.84 | 0.38–1.88 | 0.672 | |

| ADH5 | Yes | 820 | 0.83 | 0.67–1.02 | 0.075 |

| No | 205 | 0.36 | 0.2–0.66 | 0.0005 | |

| ADH6 | Yes | 820 | 1.26 | 1.03–1.55 | 0.027 |

| No | 205 | 1.89 | 1.07–3.33 | 0.026 | |

| ADH7 | Yes | 820 | 1.44 | 1.17–1.78 | 5e-04 |

| No | 205 | 1.72 | 0.98–3.04 | 0.057 |

ADH – alcohol dehydrogenase; ADH1A – alcohol dehydrogenase 1A; ADH1B – alcohol dehydrogenase 1B; ADH1C – alcohol dehydrogenase 1C; ADH2 – alcohol dehydrogenase 2; ADH3 – alcohol dehydrogenase 3; ADH4 – alcohol dehydrogenase 4; ADH5 – alcohol dehydrogenase 5; ADH6 – alcohol dehydrogenase 6; ADH7 – alcohol dehydrogenase 7.

Correlation analysis of ADH family members with clinical stage showed that various clinical stages were significantly associated with ADH1A, ADH1B, ADH1C, ADH2, ADH3, ADH4, ADH5, and AHD7 (P = 0.043, 1.1E-11, 8.7E-09, 0.039, 2.7E-12, 0.0017, 1.8E-06, and 0.003, respectively), but not ADH6 (P=0.55, 0.2009, and 0.476, respectively, Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation analysis between ADH family members of clinical stage of NSCLC.

| Isoenzymes | Clinical stage | Cases | HR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADH1A/ADH1 | I | 577 | 0.82 | 0.62–1.08 | 0.163 |

| II | 244 | 1.46 | 1.01–2.11 | 0.043 | |

| III | 70 | 0.61 | 0.36–1.06 | 0.077 | |

| ADH1B/ADH2 | I | 577 | 0.38 | 0.28–0.51 | 1.1E-11 |

| II | 244 | 0.93 | 0.64–1.34 | 0.691 | |

| III | 70 | 1.32 | 0.77–2.27 | 0.318 | |

| ADH1C/ADH3 | I | 577 | 0.45 | 0.34–0.59 | 8.7E-09 |

| II | 244 | 0.68 | 0.47–0.98 | 0.039 | |

| III | 70 | 1.35 | 0.77–2.35 | 0.295 | |

| ADH4 | I | 449 | 0.29 | 0.2–0.42 | 2.7e-12 |

| II | 161 | 0.48 | 0.33–0.77 | 0.0017 | |

| III | 44 | 0.81 | 0.4–1.64 | 0.553 | |

| ADH5 | I | 577 | 0.52 | 0.39–0.68 | 1.8e-06 |

| II | 244 | 0.83 | 0.57–1.19 | 0.305 | |

| III | 70 | 0.72 | 0.41–1.24 | 0.230 | |

| ADH6 | I | 577 | 1.08 | 0.83–1.42 | 0.55 |

| II | 244 | 1.27 | 0.83–1.83 | 0.2009 | |

| III | 70 | 0.82 | 0.48–1.41 | 0.476 | |

| ADH7 | I | 577 | 1.5 | 1.14–1.96 | 0.003 |

| II | 244 | 1.14 | 0.79–1.64 | 0.489 | |

| III | 70 | 1.37 | 0.79–2.35 | 0.257 |

ADH – alcohol dehydrogenase; ADH1A – alcohol dehydrogenase 1A; ADH1B – alcohol dehydrogenase 1B; ADH1C – alcohol dehydrogenase 1C; ADH2 – alcohol dehydrogenase 2; ADH3 – alcohol dehydrogenase 3; ADH4 – alcohol dehydrogenase 4; ADH5 – alcohol dehydrogenase 5; ADH6 – alcohol dehydrogenase 6; ADH7 – alcohol dehydrogenase 7; NSCLC – non-small cell lung cancer; HR – hazard ratio; 95%CI – 95% confidence interval.

Correlation analysis of ADH family members with chemotherapy status showed that ADH1C (ADH3) was significantly associated with non-chemotherapy status, while ADH6 was significantly associated with chemotherapy status (P=0.007, 0.004). Others members were not significantly associated with chemotherapy status (all p>0.05, Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation analysis between ADH family members and chemotherapy outcomes of NSCLC.

| Isoenzymes | Smoking status | Cases | HR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADH1A/ADH1 | Yes | 176 | 1.09 | 0.72–1.64 | 0.682 |

| No | 310 | 0.93 | 0.67–1.31 | 0.685 | |

| ADH1B/ADH2 | Yes | 176 | 1.23 | 0.82–1.85 | 0.31 |

| No | 310 | 0.72 | 0.52–1.01 | 0.056 | |

| ADH1C/ADH3 | Yes | 176 | 1.04 | 0.69–1.55 | 0.861 |

| No | 310 | 0.63 | 0.45–0.88 | 0.007 | |

| ADH4 | Yes | 34 | 0.42 | 0.12–1.39 | 0.140 |

| No | 21 | 1.66 | 0.3–9.19 | 0.555 | |

| ADH5 | Yes | 176 | 1.11 | 0.73–1.66 | 0.632 |

| No | 310 | 0.94 | 0.67–1.31 | 0.708 | |

| ADH6 | Yes | 176 | 0.55 | 0.36–0.82 | 0.004 |

| No | 310 | 0.99 | 0.71–1.39 | 0.972 | |

| ADH7 | Yes | 176 | 1.26 | 0.84–1.90 | 0.271 |

| No | 310 | 1.18 | 0.84–1.65 | 0.342 |

ADH – alcohol dehydrogenase; ADH1A – alcohol dehydrogenase 1A; ADH1B – alcohol dehydrogenase 1B; ADH1C – alcohol dehydrogenase 1C; ADH2 – alcohol dehydrogenase 2; ADH3 – alcohol dehydrogenase 3; ADH4 – alcohol dehydrogenase 4; ADH5 – alcohol dehydrogenase 5; ADH6 – alcohol dehydrogenase 6; ADH7 – alcohol dehydrogenase 7; NSCLC – non-small cell lung cancer; HR – hazard ratio; 95%CI – 95% confidence interval.

GO analysis with the terms of biological process, cellular component, and molecular function and KEGG pathways enrichment analysis were performed using DAVID. The top 5 results of the enrichment analysis were ethanol metabolic process, monohydric alcohol metabolic process, ethanol oxidation, alcohol dehydrogenase (NAD) activity, alcohol dehydrogenase activity, and zinc-dependent (Table 4). The enriched KEGG pathways included fatty acid metabolism, tyrosine metabolism, retinol metabolism, metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450, glycolysis/gluconeogenesis, and drug metabolism (Table 5).

Table 4.

Enrichment analysis of gene ontology of ADH family members.

| Category | Term | Count | % | P value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO: 0006067~ethanol metabolic process | 5 | 100 | 3.58E-15 | 3.34E-12 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO: 0034308~monohydric alcohol metabolic process | 5 | 100 | 3.58E-15 | 3.34E-12 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO: 0006069~ethanol oxidation | 5 | 100 | 3.58E-15 | 3.34E-12 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0004022~alcohol dehydrogenase (NAD) activity | 5 | 100 | 2.96E-14 | 2.73E-11 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0004024~alcohol dehydrogenase activity, zinc-dependent | 4 | 80 | 4.39E-11 | 4.06E-08 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO: 0055114~oxidation reduction | 5 | 100 | 4.93E-06 | 0.00463976 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO: 0001523~retinoid metabolic process | 3 | 60 | 1.66E-05 | 0.01556916 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO: 0016101~diterpenoid metabolic process | 3 | 60 | 1.66E-05 | 0.01556916 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO: 0006721~terpenoid metabolic process | 3 | 60 | 1.96E-05 | 0.01845758 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO: 0006720~isoprenoid metabolic process | 3 | 60 | 6.18E-05 | 0.05808355 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO: 0019748~secondary metabolic process | 3 | 60 | 2.01E-04 | 0.18840753 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0035276~ethanol binding | 2 | 40 | 6.16E-04 | 0.56876933 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0008270~zinc ion binding | 5 | 100 | 0.001002 | 0.92332089 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0046914~transition metal ion binding | 5 | 100 | 0.002114 | 1.93934293 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0004745~retinol dehydrogenase activity | 2 | 40 | 0.003078 | 2.81253478 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0019841~retinol binding | 2 | 40 | 0.003692 | 3.36573224 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0005501~retinoid binding | 2 | 40 | 0.006455 | 5.8174382 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0008289~lipid binding | 3 | 60 | 0.006866 | 6.17736413 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0019840~isoprenoid binding | 2 | 40 | 0.007068 | 6.35398528 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0016620~oxidoreductase activity, acting on the aldehyde or oxo group of donors, NAD or NADP as acceptor | 2 | 40 | 0.007068 | 6.35398528 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0043178~alcohol binding | 2 | 40 | 0.007681 | 6.88755783 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO: 0006081~cellular aldehyde metabolic process | 2 | 40 | 0.008254 | 7.49884376 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0046872~metal ion binding | 5 | 100 | 0.010329 | 9.162224 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0043169~cation binding | 5 | 100 | 0.010724 | 9.49713106 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0043167~ion binding | 5 | 100 | 0.011375 | 10.0467972 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0051287~NAD or NADH binding | 2 | 40 | 0.014404 | 12.5650629 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO: 0010033~response to organic substance | 3 | 60 | 0.015839 | 13.9415732 |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO: 0045471~response to ethanol | 2 | 40 | 0.018792 | 16.339828 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0019842~vitamin binding | 2 | 40 | 0.039459 | 31.1056241 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0050662~coenzyme binding | 2 | 40 | 0.054616 | 40.5359414 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0009055~electron carrier activity | 2 | 40 | 0.066378 | 47.0415213 |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO: 0048037~cofactor binding | 2 | 40 | 0.074545 | 51.1777008 |

ADH – alcohol dehydrogenase; FDR – false discovery rate.

Table 5.

Enrichment analysis of KEGG pathways of ADH family members.

| Term | Count | % | P value | FDR | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa00071: Fatty acid metabolism | 5 | 100 | 3.28E-09 | 1.69E-06 | ADH4, ADH1C, ADH5, ADH6, ADH1B, ADH7, ADH1A |

| hsa00350: Tyrosine metabolism | 5 | 100 | 4.88E-09 | 2.52E-06 | ADH4, ADH1C, ADH5, ADH6, ADH1B, ADH7, ADH1A |

| hsa00830: Retinol metabolism | 5 | 100 | 1.14E-08 | 5.86E-06 | ADH4, ADH1C, ADH5, ADH6, ADH1B, ADH7, ADH1A |

| hsa00980: Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450 | 5 | 100 | 1.75E-08 | 9.03E-06 | ADH4, ADH1C, ADH5, ADH6, ADH1B, ADH7, ADH1A |

| hsa00010: Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis | 5 | 100 | 1.75E-08 | 9.03E-06 | ADH4, ADH1C, ADH5, ADH6, ADH1B, ADH7, ADH1A |

| hsa00982: Drug metabolism | 5 | 100 | 2.00E-08 | 1.03E-05 | ADH4, ADH1C, ADH5, ADH6, ADH1B, ADH7, ADH1A |

ADH – alcohol dehydrogenase; ADH1A – alcohol dehydrogenase 1A; ADH1B – alcohol dehydrogenase 1B; ADH1C – alcohol dehydrogenase 1C; ADH2 – alcohol dehydrogenase 2; ADH3 – alcohol dehydrogenase 3; ADH4 – alcohol dehydrogenase 4; ADH5 – alcohol dehydrogenase 5; ADH6 – alcohol dehydrogenase 6; ADH7 – alcohol dehydrogenase 7; FDR – false discovery rate.

Survival curve analysis of ADH family members using Kaplan-Meier Plotter

First, the prognostic value of ADH family members were assessed using the Kaplan–Meier Plotter online website. The Affymetrix ID of ADH1A was 207820. There was no statistically significant difference in the adenocarcinoma and SCC types (P=0.78, HR=1.02, 95% confidence interval [CI]=0.90–1.16); P=0.24, HR=0.87, 95% CI=0.69–1.10; P=0.88, HR=1.02, 95% CI=0.80–1.30, Figure 3). The Affymetrix ID of ADH1B was 209612. There were statistically significant differences in both adenocarcinoma and all (adenocarcinoma and SCC) histological types, (P=5.4e-11, HR=0.65, 95% CI=0.58–0.74; P=5.4e-10, HR=0.47, 95% CI=0.37–0.60), but no significant difference in SCC (P=0.91, HR=0.99, 95% CI=0.78–1.25, Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Survival analysis of ADH1A (207820_at) in NSCLC. (A) Survival analysis of ADH1A in both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer; (B) Survival analysis of ADH1A in adenocarcinoma; (C) Survival analysis of ADH1A in squamous cell cancer.

Figure 4.

Survival analysis of ADH1B (209612_at) in NSCLC. (A) Survival analysis of ADH1B in both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer; (B) Survival analysis of ADH1B in adenocarcinoma; (C) Survival analysis of ADH1B in squamous cell cancer.

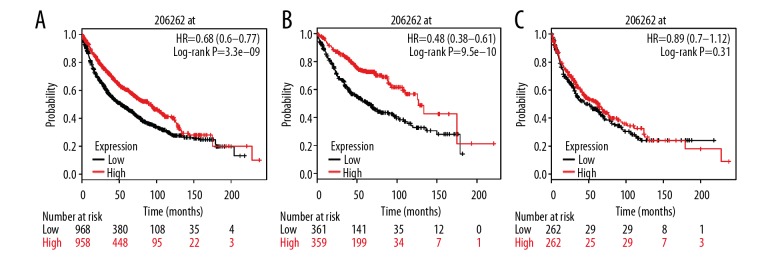

The Affymetrix ID of ADH1C (ADH3) was 206262. There was a significant difference in adenocarcinoma and all (adenocarcinoma and SCC) histological types (P=3.3e-09, HR=0.68, 95% CI=0.60–0.77; P=9.5e-10, HR=0.48, 95% CI=0.38–0.61, respectively), but no significant difference in SCC (P=0.31, HR=0.89, 95% CI=0.70–1.12, Figure 5). The Affymetrix ID of ADH4 is 223781. There were significant differences in both tissue types and adenocarcinoma (P=8.1e-07, HR=0.65, 95% CI=0.55–0.77; P=7.2e-07, HR=0.53, 95% CI=0.41–0.68, respectively), but no significant difference in SCC (P=0.83, HR=1.04, 95% CI=0.76–1.41, Figure 6).

Figure 5.

Survival analysis of ADH1C (206262_at) in NSCLC. (A) Survival analysis of ADH1C in both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer; (B) Survival analysis of ADH1C in adenocarcinoma; (C) Survival analysis of ADH1C in squamous cell cancer.

Figure 6.

Survival analysis of ADH4 (223781_at) in NSCLC. (A) Survival analysis of ADH4 in both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer; (B) Survival analysis of ADH4 in adenocarcinoma; (C) Survival analysis of ADH4 in squamous cell cancer.

The Affymetrix ID of ADH5 was 208847. There were significant differences in both tissue types and adenocarcinoma (P=0.037, HR=0.87, 95% CI=0.77–0.99; P=1.3e-08, HR=0.50, 95% CI=0.40–0.64), as well as SCC (P=0.53, HR=1.08, 95% CI=0.85–1.37, Figure 7). The Affymetrix ID of ADH6 was 207544. There was no significant difference in any category (P=0.82, HR=0.99, 95% CI=0.87–1.12; P=0.46, HR=0.92, 95% CI=0.72–1.16; P=0.93, HR=1.01, 95% CI=0.8–1.28), respectively, Figure 8). The Affymetrix ID of ADH7 was 210505. There were significant differences in both tissue types (P=9e-05, HR=1.29, 95% CI=1.13–1.46), but no significant difference between adenocarcinoma and SCC (P=0.8, HR=1.03, 95% CI=0.82–1.30; P=0.75, HR=0.96, 95% CI=0.76–1.22, Figure 9).

Figure 7.

Survival analysis of ADH5 (208847_at) in NSCLC. (A) Survival analysis of ADH5 in both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer; (B) Survival analysis of ADH5 in adenocarcinoma; (C) Survival analysis of ADH5 in squamous cell cancer.

Figure 8.

Survival analysis of ADH6 (207544_at) in NSCLC. (A) Survival analysis of ADH6 in both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer; (B) Survival analysis of ADH6 in adenocarcinoma; (C) Survival analysis of ADH6 in squamous cell cancer.

Figure 9.

Survival analysis of ADH7 (210505_at) in NSCLC. (A) Survival analysis of ADH7 in both adenocarcinoma and squamous cell cancer; (B) Survival analysis of ADH7 in adenocarcinoma; (C) Survival analysis of ADH7 in squamous cell cancer.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the associations between ADH gene family members and NSCLC prognosis. The study results showed that the expression levels of ADH1B, ADH1C, ADH4, and ADH5 were associated with the prognosis of NSCLC and both the adenocarcinoma and SCC histological types, but not with the SCC histological type. High expression of ADH1B, ADH1C, ADH4, and ADH5 at the gene level, as opposed to low expression, was associated with a better prognosis. Low expression of ADH7 was associated with a better prognosis among patients with both the adenocarcinoma and SCC histological types. Moreover, expression of ADH family members was associated with smoking status, clinical stage, and chemotherapy status.

ADH catalyzes the conversion between ethanol and aldehydes and ketones. Members of the ADH family have been extensively researched. ADH catalyzes the conversion of ethanol into acetaldehyde, a very active and toxic substance [30]. In the metabolic process of insects, from the larval to the adult stage, various kinds of alcohol produced by microbial fermentation are converted into the corresponding aldehydes and ketones (in homogeneous dimer form) [31]. A recent study reported that ADH family members have potential values in pancreatic adenocarcinoma patients’ prognosis [32]. Levels of AHD1A, ADH1B encoding enzymes in the omega oxidation pathway are associated with hexadecanedioate levels, which can regulate the effect of alcohol of blood pressure [33]. Animal studies using pyrazole have shown that ADH is a specific inhibitor and the key enzyme in the metabolism of ethanol [34]. ADH1A, ADH1B, and ADH1C, which are encoded by genes located on chromosome 4q23, are responsible for most of the metabolism of ethanol in the liver [35]. A recent study indicated that a genetic variant of ADH1B, rs1229984, is a risk factor for esophageal cancer [11]. A meta-analysis of 35 case-control studies found that a single-nucleotide polymorphism of ADH1C (rs698) can increase the risk of cancer in African and Asian populations [36]. ADH1 and ADH4 are retinol dehydrogenases involved in the process of retinol oxidation, which is necessary for the synthesis of retinoic acid from retinoic acid [19].

As compared with other promoters, the ADH2 gene product promotes the translation of various molecules. When the biomass concentration is appropriately increased, ADH2 expression is relatively high, which optimizes bioethanol fermentation. However, the 573-bp ADH2 promoter is suppressed by hundreds of times in the presence of glucose [37,38]. ADH2 gene expression can be activated by the yeast regulatory protein ADR1 and, therefore, inhibition of ADH2 expression should control the synthesis of the ADR1 protein [39]. In addition, ADH2 complement can be used to determine the function of the gene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae As2.4 [40]. ADH1 and ADH2 are mainly expressed in the liver and gastric mucosa, where both are involved in the metabolism of oral alcohol, that is, the conversion of ethanol into the carcinogenic metabolite acetaldehyde, especially in the elimination stage [41–43]. In the esophageal muscle tissue, 2 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (rs1126671 and rs1800759) were associated with lower ADH4 expression levels in fibroblasts [44]. The ADH4 gene encodes the π subunit in humans and can metabolize many substances, including ethanol, retinol, other aliphatic alcohols, hydroxysteroids, and lipid peroxidation products [45]. The ADH5 gene encodes the χ subunit, which participates in the metabolism of alcohols and aldehydes [46]. According to a literature review, an ADH7 variant is associated with Parkinson’s disease [47]. Another study reported that the modulating effect of ADH7 is dependent on the gene sequence and the extracellular environment [48].

ADH may be involved in the metabolic pathway of several neurotransmitters involved in the neurobiology of neuropsychiatric diseases, in addition to catalyzing the oxidation of retinol and ethanol. Studies have shown that the common ADH mutation carries risks associated with schizophrenia in African-Americans and European Americans [49]. ADH1 expression plays an important role in the transformation of extracellular matrix in the etiology of uterine fibroids. Although no significant difference was found in the activity of ADH1, the number of tumors was negatively correlated with the expression level of ADH1 [50]. According to the literature, ADH1B mRNA levels were reduced (>10-fold) in 65% of lung cancer cDNA samples, which was associated with the onset and progression of human lung cancer [51]. Also, the ADH1C SspI polymorphism could play a significant role in the etiology of oral cancer and genetic polymorphisms of ethanol-metabolizing enzymes may affect individual susceptibility to oral cancer [52]. Chip data show that ADH4 mRNA and protein expression levels were significantly reduced in HCC and there was a significant correlation with survival rate, indicating that ADH4 is a potential prognostic marker for HCC patients [53]. Another study provided abundant evidence that the rs3805322 polymorphism of the ADH4 gene may be related to an increased risk of SCC in 2 populations of Han Chinese [54]. Also, the ADH1A-ADH1B-ADH7 cluster single-nucleotide polymorphisms conferred susceptibility to esophageal SCC in 2 case-control sets [55].

Many studies have focused on the associations between ADH family members and various diseases, including alcoholism, Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, and HCC, among others. In addition, the roles of some ADH family members in lung cancer have also been explored. The results of the present study found that, with the exception of ADH5, the expression levels of other SDH family members were relatively high in normal lung tissues. The expression levels of ADH1B, ADH1C, ADH4, and ADH5 were associated with the prognosis of NSCLC patients with adenocarcinoma and both the adenocarcinoma and SCC histological types. In fact, the prognosis of patients with high expression levels of ADH1B, ADH1C, ADH4, and ADH5 was better than that of those with low expression levels. Low expression of ADH7 was associated with a better prognosis among patients with the adenocarcinoma and SCC histological types. Moreover, expression of ADH family members was associated with smoking status, clinical stage, and chemotherapy status. Therefore, our findings indicate that ADH1B (ADH2), ADH1C (ADH3), ADH4, ADH5, and ADH7 may be suitable as potential markers for the prognosis of NSCLC. Furthermore, we hypothesized that ADH1B (ADH2), ADH1C (ADH3), and ADH4 may function as tumor-suppressors, and that ADH5 and ADH7 may play oncogenic roles in NSCLC tumorigenesis. Smoking status, clinical stage, and chemotherapy may influence the expression of ADH family members.

There were some limitations to this study that should to be addressed. First, the study cohort was relatively small; thus, larger studies are needed to verify these findings. In addition, further studies of multiple centers with patients of various races are needed. To address these issues, we are planning well-designed functional verification studies, including in vitro and in vivo models, in the near future. As other potential shortcomings, ADH1B (ADH2), ADH1C (ADH3), ADH4, ADH5, and ADH7 were all associated with the prognosis of NSCLC and smoking may influence the expression of genes and the clinical stage of disease. Thus, ADH1B, ADH1C (ADH3), ADH2, ADH4, ADH5, and ADH7 are potential prognostic biomarkers for NSCLC.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the aim of this study was to explore the associations between NSCLC prognosis and the expression patterns of ADH family members. Our study found that ADH1B (ADH2), ADH1C (ADH3), ADH4, ADH5, and ADH7 were all associated with the prognosis of NSCLC and smoking may influence the expression of genes and the clinical stage of disease. Thus, ADH1B (ADH2), ADH1C (ADH3), ADH4, ADH5, and ADH7 are potential prognostic biomarkers for NSCLC.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the curators of the Kaplan-Meier Plotter website for their valuable contributions to this work.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

Source of support: Departmental sources

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.You Q, Guo H, Xu D. Distinct prognostic values and potential drug targets of ALDH1 isoenzymes in non-small-cell lung cancer. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2015;9(default):5087–97. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S87197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(2):87–108. doi: 10.3322/caac.21262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsao AS, Scagliotti GV, Bunn PA, Jr, et al. Scientific advances in lung cancer 2015. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(5):613–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cao X, Zhao Y, Wang J, et al. TUSC2 downregulates PD-L1 expression in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) Oncotarget. 2017;8(64):107621–29. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang H, Yu Z, Huo S, et al. Overexpression of ELF3 facilitates cell growth and metastasis through PI3K/Akt and ERK signaling pathways in non-small cell lung cancer. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2018;94:98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang N, Zhang T. Down-regulation of microRNA-135 promotes sensitivity of non-small cell lung cancer to gefitinib by targeting TRIM16. Oncol Res. 2018 doi: 10.3727/096504017X15144755633680. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Zhao K, Cheng J, Chen B, et al. Circulating microRNA-34 family low expression correlates with poor prognosis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9(10):3735–46. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.09.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tokuhiro K, Ishida N, Nagamori E, et al. Double mutation of the PDC1 and ADH1 genes improves lactate production in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae expressing the bovine lactate dehydrogenase gene. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;82(5):883–90. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1831-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duell EJ, Sala N, Travier N, et al. Genetic variation in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH1A, ADH1B, ADH1C, ADH7) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2), alcohol consumption and gastric cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33(2):361–67. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghosh S, Bankura B, Ghosh S, et al. Polymorphisms in ADH1B and ALDH2 genes associated with the increased risk of gastric cancer in West Bengal, India. BMC Cancer. 2017;17(1):782. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3713-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H, Gu S, Han Y, et al. Diversification of the ADH1B gene during expansion of modern humans. Ann Hum Genet. 2011;75(4):497–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2011.00651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ehlers CL, Gilder DA, Harris L, Carr L. Association of the ADH2*3 allele with a negative family history of alcoholism in African American young adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25(12):1773–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wall TL, Carr LG, Ehlers CL. Protective association of genetic variation in alcohol dehydrogenase with alcohol dependence in Native American Mission Indians. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):41–46. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ji Y, Lee S, Kim K, et al. Association between ADH1B and ADH1C polymorphisms and the risk of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(6):4387–96. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3078-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji YB, Lee SH, Kim KR, et al. Association between ADH1B and ADH1C polymorphisms and the risk of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(6):4387–96. doi: 10.1007/s13277-015-3078-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao X, Wang M, Zhong D, et al. ADH1CIle350Val polymorphism and cancer risk: Evidence from 35 case-control studies. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37227. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo X, Kranzler HR, Zuo L, et al. Diplotype trend regression analysis of the ADH gene cluster and the ALDH2 gene: Multiple significant associations with alcohol dependence. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;78(6):973–87. doi: 10.1086/504113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haselbeck RJ, Duester G. ADH1 and ADH4 alcohol/retinol dehydrogenases in the developing adrenal blastema provide evidence for embryonic retinoid endocrine function. Dev Dyn. 1998;213(1):114–20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199809)213:1<114::AID-AJA11>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostberg LJ, Strömberg P, Hedberg JJ, et al. Analysis of mammalian alcohol dehydrogenase 5 (ADH5): Characterisation of rat ADH5 with comparisons to the corresponding human variant. Chem Biol Interact. 2013;202(1–3):97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoog J, Brandt M, Hedberg JJ, Stromberg P. Mammalian alcohol dehydrogenase of higher classes: Analyses of human ADH5 and rat ADH6. Chem Biol Interact. 2001;130–132(1–3):395–404. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Birley AJ, James MR, Dickson PA, et al. Association of the gastric alcohol dehydrogenase gene ADH7 with variation in alcohol metabolism. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17(2):179–89. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaul YD, Yuan B, Prathapan T, et al. MERAV: A tool for comparing gene expression across human tissues and cell types. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(Database issue):D560–66. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Montojo J, Zuberi K, Rodriguez H, et al. GeneMANIA Cytoscape plugin: Fast gene function predictions on the desktop. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2010;26(22):2927–28. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szklarczyk D, Franceschini A, Wyder S, et al. STRING v10: Protein-protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D447–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4(1):44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(1):1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Staff TPO. Correction: Online survival analysis software to assess the prognostic value of biomarkers using transcriptomic data in non-small-cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e82241. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhao CC, Cai HB, Wang H, Pan SY. Role of ADH2 and ALDH2 gene polymorphisms in the development of Parkinson’s disease in a Chinese population. Genet Mol Res. 2016;15(3) doi: 10.4238/gmr.15038606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goulielmos GN, Loukas M, Bondinas G, Zouros E. Exploring the evolutionary history of the alcohol dehydrogenase gene (Adh) duplication in species of the family tephritidae. J Mol Evol. 2003;57(2):170–80. doi: 10.1007/s00239-003-2464-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liao X, Huang R, Liu X, et al. Distinct prognostic values of alcohol dehydrogenase mRNA expression in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. OncoTargets Ther. 2017;10:3719–32. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S140221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Menni C, Metrustry SJ, Ehret G, et al. Molecular pathways associated with blood pressure and hexadecanedioate levels. PLoS One. 2017;12(4):e0175479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crow KE, Hardman MJ. Regulation of rates of ethanol metabolism. 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kayaaltı Z, Söylemezoğlu T. Distribution of ADH1B, ALDH2, CYP2E1 *6, and CYP2E1 *7B genotypes in Turkish population. Alcohol. 2010;44(5):415–23. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ye B, Ji CY, Zhao Y, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphism at alcohol dehydrogenase-1B is associated with risk of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell Int. 2014;14(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-14-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weinhandl K, Winkler M, Glieder A, Camattari A. Carbon source dependent promoters in yeasts. Microb Cell Fact. 2014;13(1):5. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-13-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Price VL, Taylor WE, Clevenger W, et al. [25] Expression of heterologous proteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using the ADH2 promoter. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185(185):308–18. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85027-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vallari RC, Cook WJ, Audino DC, et al. Glucose repression of the yeast ADH2 gene occurs through multiple mechanisms, including control of the protein synthesis of its transcriptional activator, ADR1. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12(4):1663–73. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.4.1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ye W, Zhang W, Liu T, et al. Improvement of ethanol production in saccharomyces cerevisiae by high-efficient disruption of the ADH2 gene using a novel recombinant TALEN vector. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1067. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Duell E, Sala N, Travier N, et al. Genetic variation in alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH1A, ADH1B, ADH1C, ADH7) and aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH2), alcohol consumption and gastric cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) cohort. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33(2):361–67. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haseba T, Kameyama K, Mashimo K, Ohno Y. Dose-dependent change in elimination kinetics of ethanol due to shift of dominant metabolizing enzyme from ADH 1 (Class I) to ADH 3 (Class III) in mouse. Int J Hepatol. 2012;2012:408190. doi: 10.1155/2012/408190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chung CS, Lee YC, Liou JM, et al. Tag single nucleotide polymorphisms of alcohol-metabolizing enzymes modify the risk of upper aerodigestive tract cancers: HapMap database analysis. Dis Esophagus. 2014;27(5):493–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fourier C, Ran C, Steinberg A, et al. Screening of two ADH4 variations in a swedish cluster headache case-control material. Headache. 2016 doi: 10.1111/head.12807. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scionti F, Di Martino MT, Sestito S, et al. Genetic variants associated with Fabry disease progression despite enzyme replacement therapy. Oncotarget. 2017;8(64):107558–64. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.22505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edenberg HJ. Regulation of the mammalian alcohol dehydrogenase genes. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 2000;64:295–341. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(00)64008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buervenich S, Sydow O, Carmine A, et al. Alcohol dehydrogenase alleles in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2000;15(5):813–18. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200009)15:5<813::aid-mds1008>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jairam S, Edenberg HJ. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms interact to affect ADH7 transcription. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(4):921–29. doi: 10.1111/acer.12340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zuo L, Wang K, Zhang XY, et al. Association between common alcohol dehydrogenase gene (ADH) variants and schizophrenia and autism. Hum Genet. 2013;132(7):735–43. doi: 10.1007/s00439-013-1277-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Csatlós E, Rigó J, Laky M, et al. The role of the alcohol dehydrogenase-1 (ADH1) gene in the pathomechanism of uterine leiomyoma. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;170(2):492–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mutka SC, Green LH, Verderber EL, et al. ADH IB expression, but not ADH III, is decreased in human lung cancer. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52995. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brocic M, Supic G, Zeljic K, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of ADH1C and CYP2E1 and risk of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(4):586–93. doi: 10.1177/0194599811408778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wei RR, Zhang MY, Rao HL, et al. Identification of ADH4 as a novel and potential prognostic marker in hepatocellular carcinoma. Med Oncol. 2012;29(4):2737–43. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0126-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu X, Wang J, Zhu SM, et al. Impact of alcohol dehydrogenase gene 4 polymorphisms on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma risk in a chinese population. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0127304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang J, Wei J, Xu X, et al. Replication study of ESCC susceptibility genetic polymorphisms locating in the ADH1B-ADH1C-ADH7 cluster identified by GWAS. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e94096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]