Abstract

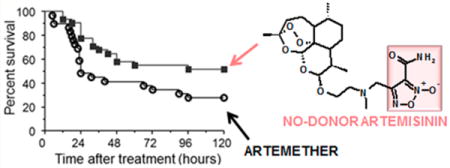

Hybrid products in which the dihydroartemisinin scaffold is combined with NO-donor furoxan and NONOate moieties have been synthesized and studied as potential tools for the treatment of cerebral malaria (CM). The designed products were able to dilate rat aorta strips precontracted with phenylephrine with a NO-dependent mechanism. All hybrid compounds showed preserved antiplasmodial activity in vitro and in vivo against Plasmodium berghei ANKA, comparable to artesunate and artemether. Hybrid 10, selected for additional studies, was capable of increasing survival of mice with late-stage CM from 27.5% to 51.6% compared with artemether. Artemisinin-NO-donor hybrid compounds show promise as potential new drugs for treating cerebral malaria.

Graphical abstract

■ INTRODUCTION

Malaria is a world-spread disease caused by Plasmodium protozoa transmitted by female Anopheles mosquitos. The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that 198 million cases of malaria and 584 000 deaths occurred globally in 2013, 90% in the WHO African region, mostly among children in sub-Saharan Africa.1 P. falciparum is responsible for severe malaria (SM), the most aggressive form of the disease characterized by a high incidence of mortality if untreated. A complication of SM is cerebral malaria (CM) that kills 20% of patients, mainly children below 5 years of age, admitted to hospitals and treated with intravenous artesunate, the current mainstay treatment for this deadly condition.2 In addition 25% of the patients that survive develop cognitive and neurological deficits.3 Cerebral malaria is characterized by the blockage of the cerebral microvasculature by Plasmodium-infected red blood cells with consequent ischemia, hypoxia, disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), edema, and coma.4 Low availability of nitric oxide (NO) seems to play an important role in the pathogenesis of human and murine experimental cerebral malaria (ECM). It is principally related to the NO-scavenging effects by high concentrations in cell-free plasma of free oxyhemoglobin (HbO2+) derived from hemolysis and to hypoargininemia.5 Low levels of exhaled NO, low plasma arginine concentration, high levels of free hemoglobin, and endothelial dysfunction were found in patients with SM/ CM.6–9 The same findings are observed in the ECM model,5 and the resulting widespread vasoconstriction contributes to cerebral hypoxia and acidosis.10,11 Mice with ECM show impaired response of brain vessels to endothelial and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (eNOS and nNOS) dependent vasodilators.12 Administration of NO donors can prevent the neurological syndrome and the associated vascular dysfunction,13–15 and more important, NO donors such as glyceryl trinitrate improve survival of mice with late-stage ECM and reverse ECM cerebrovascular constriction.16 In a previous study we designed a new series of hybrid compounds in which amodiaquine, an established antimalarial drug included in the World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines,17 was joined with NO-donor furoxan and nitrooxy (ONO2)18 moieties and studied them as potential anti SM/CM tools. All the amodiaquine-NO-donor hybrids were able to dilate rat aorta strips precontracted with phenylephrine with a NO-dependent mechanism and displayed high degree of activity against both chloroquine-sensitive and chloroquine-resistant strains of P. falciparum. Two of them, tested in vivo on Plasmodium berghei ANKA-infected (PbA) mice, showed a trend for prolonged survival of mice with CM. As development of this research, we designed new NO-donor hybrid drugs obtained by joining the dihydroartemisinin scaffold 1 (Chart 1) with NO-donor furoxan and NONOate moieties (Scheme 1, 10–12; Scheme 2, 18). Compound 1, a semisynthetic derivative of artemisinin 2 (Chart 1), causes a rapid decrease in parasites biomass (about 10 000-fold per cycle in vitro) different from amodiaquine which displays a longer parasite clearance time. Dihydroartemisinin is used with other artemisinin derivatives, artesunate (3) and artemether (4) as first-line drug for the treatment of P. falciparum malaria in most endemic areas and for the in vivo treatment of chloroquine-resistant P. vivax malaria.19 In this paper we describe the synthesis of these products, their ability of relaxing rat aorta strips precontracted with phenylephrine, and their P. berghei-killing capacity in vitro and in vivo. The ability of 10 to rescue mice with ECM from death in comparison with artemether is also discussed.

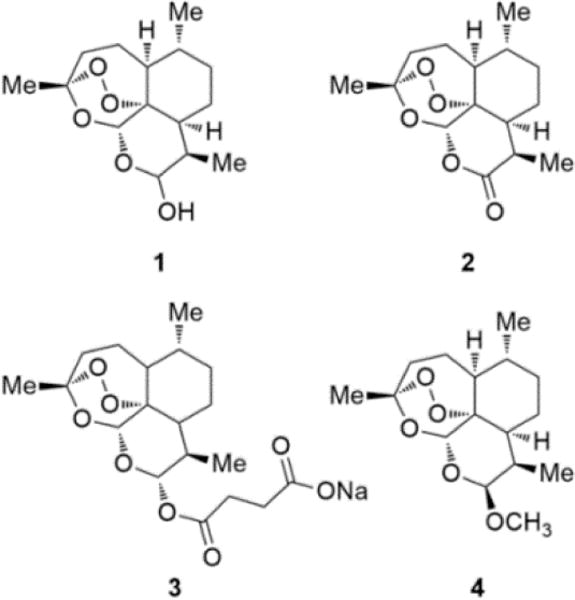

Chart 1. Structures of Dihydroartemisinin (1), Artemisinin (2), Sodium Artesunate (3), and Artemether (4).

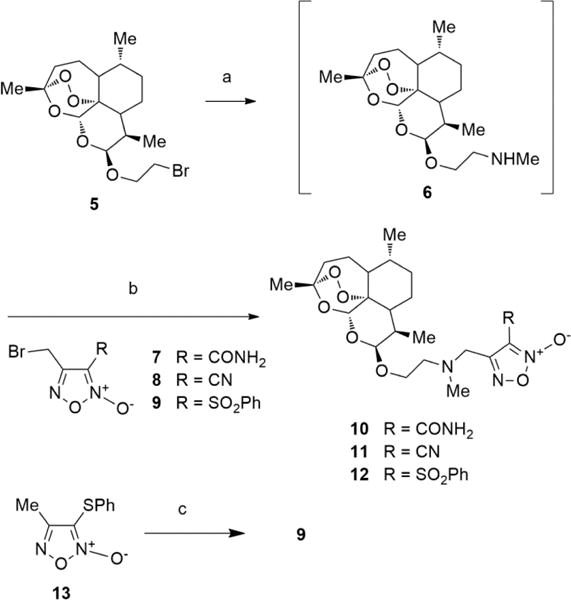

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Hybrids 10–12 and Intermediate 9a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) MeNH2 33% w/v in abs EtOH, CH2Cl2, rt, 72 h; (b) Et3N, 2-propanol, rt, 18–40 h; (c) (i) NBS/AIBN, CCl4, reflux, 96 h; (ii) flash chromatography to recover unreacted 13; (iii) mCPBA, 0 °C to rt, 24 h.

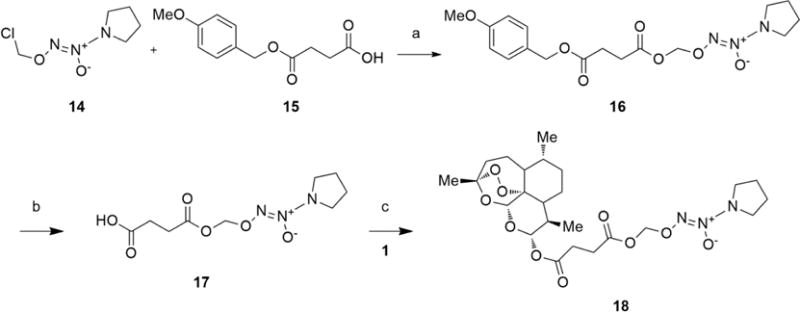

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Hybrid 16a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) Cs2CO3, dry DMF, rt, 1 h; (b) PhOH, CF3COOH cat., 40 °C, 1 h; (c) DCC, DMAP cat., 0 °C to rt, 5 h.

■ RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Chemistry

The purity of the target compounds was assessed through elemental analysis (C, H, N) and was ≥95%. The hybrid furoxan derivatives 10–12 were obtained according to the synthetic pathway described in Scheme 1. 1-Bromo-2-(10b-dihydroartemisinoxy)ethane (5) was treated with methylamine (33% in absolute ethanol) to give the substitution product 6. This intermediate was purified by flash chromatography and, without any additional characterization, was dissolved in 2-propanol and reacted with the appropriate 3-substituted-4-bromomethylfuroxans 7–9 to afford the target compounds. Preparation of 4-bromomethyl-3-phenylsulfonyl-furoxan (9) (Scheme 1), the reagent used to synthesize the hybrid 12, was time-consuming and laborious. The action of N-bromosuccinimide (NBS) and azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) on 4-methyl-3-thiophenylfuroxan (13), run in refluxing CCl4, afforded a mixture of the starting material 13, its isomer 3-methyl-4-thiophenylfuroxan, and related bromomethyl derivatives. Flash chromatography allowed separation of unreacted 13 from a mixture of 3-methyl-4-thiophenylfuroxan and 3(4)-bromomethyl-4(3)-thiophenylfuroxans. The mixture was treated with m-chloroperbenzoic acid (mCPBA) to give the corresponding phenylsulfonyl derivatives from which 9 was obtained by flash chromatography in 12% overall yield.

The preparation of the hybrid 18 containing the NONOate substructure as NO-donor moiety is depicted in Scheme 2. The coupling of O2-chloromethyl-1-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate (14) with 4-methoxybenzyl ester of succinic acid (15) under the action of Cs2CO3 gave the adduct 16. This compound was deprotected by treatment with phenol and a catalytic amount of trifluoroacetic acid to afford the free acid 17. This acid was then reacted with 1 using dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) in the presence of 4-dimethylamino-pyridine (DMAP) to give the expected product 18.

Biological Activities

Vasodilator Activity

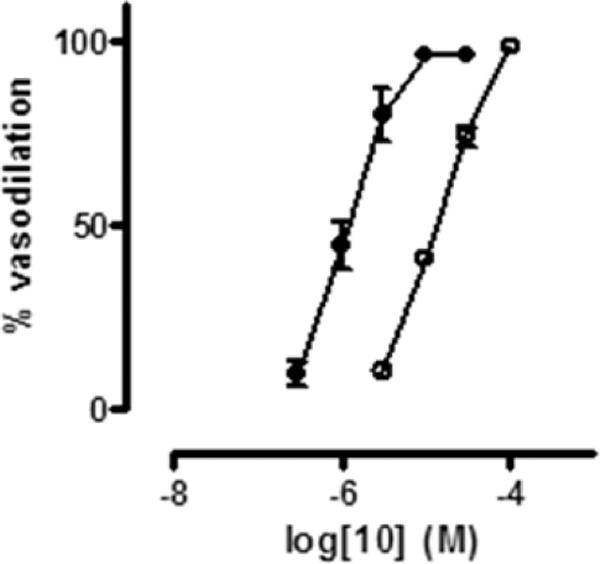

All the hybrid products here described were able to relax rat aorta strips precontracted with phenylephrine in a concentration dependent manner (Figure 1). Their vasodilator potencies, expressed as EC50, are reported in Table 1. Analysis of the data shows the potency rank in the order 18 > 11 > 12 > 10. When the experiments were repeated in the presence of ODQ (1H-[1,2,4]oxadiazole[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one) which is a potent inhibitor of the soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), an enzyme that mediates a variety of biological responses including the NO-dependent vasodilation, a decrease in the potencies was observed (see Table 1 and Figure 1). This indicates that the products are capable of releasing NO in the vessels, thus suggesting their potential use in the CM therapy.

Figure 1.

Concentration–response curves for 10 with (○) and without (●) 1 μM ODQ.

Table 1.

Vasodilation Potencies of the Synthesized Hybrids 10–12 and 18 on Rat Aorta Strips

| compd | EC50 (μM)a

|

|

|---|---|---|

| +ODQ, 1 μMb | ||

| 10 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 12 ± 1 |

| 11 | 0.023 ± 0.004 | 0.25 ± 0.06 |

| 12 | 0.41 ± 0.05 | 30 ± 17 |

| 18 | 0.0036 ± 0.0004 | 0.14 ± 0.02 |

The endothelium deprived aortic strips were allowed to equilibrate for 120 min and then contracted with L-phenylephrine (1 μM). Cumulative concentrations of the vasodilating agent were added. Data are the mean ± SEM of at least three experiments.

Effect of 1 μM ODQ was evaluated in a separate series of experiments in which it was added to the organ bath 5 min before the contraction.

Antiplasmodial Activity in Vitro and in Vivo

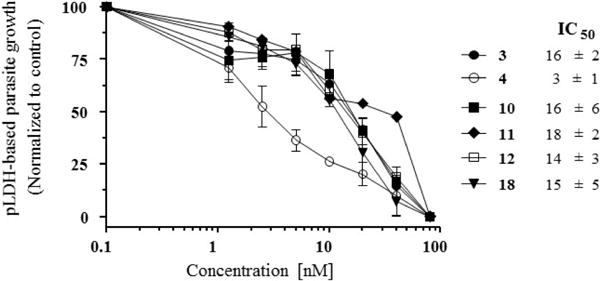

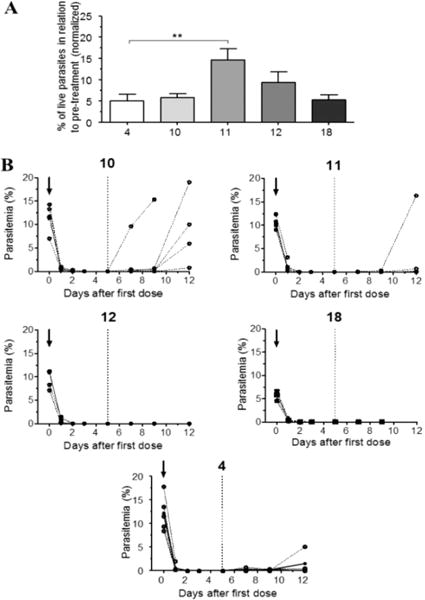

We asked whether the modification of the artemisinin structure by the introduction of the NO-donor moieties might have decreased its antimalarial activity. For this purpose, in vitro and in vivo tests with Plasmodium berghei were performed as previously described.20,21 In vitro, hybrids 10, 11, 12, and 18 were tested and compared with reference drugs 3 and 4. The hybrid compounds showed in vitro antiplasmodial activity very similar to that of artesunate, in the low nanomolar range. Artemether showed the strongest activity (Figure 2). The evaluation of the in vivo antiplasmodial activity was performed using our previously described protocol, designed to determine the effect of the test drug in mice with established parasitemia.21 In this protocol, mice were infected with P. berghei ANKA and treated at day 5 of infection, before clinical signs of neurological involvement were evident, with parasitemia in the range 5– 15%. Drugs were administered once a day for 5 days, and parasitemia was checked every 24 h. There was no difference in the rate of parasite clearance in the first 24 h between artemether and the hybrids 10, 12, and 18, all of them decreasing parasitemia by about 95% with a single dose (Figure 3A). Hybrid 11 showed significantly lower activity, killing about 85% of the parasites with one dose. All drugs were able to bring parasitemia to undetectable levels by day 5 of treatment, and 12 and 18 were also capable of preventing recrudescence (Figure 3B). Overall, these results show that the introduction of the NO-donor moiety did not significantly modify artemisinin’s antiplasmodial activity.

Figure 2.

In vitro activity of hybrids 10–12, 18 and reference drugs artesunate (3) and artemether (4) against Plasmodium berghei: curves of P. berghei in vitro sensitivity to each drug and their respective IC50 values.

Figure 3.

In vivo activity of hybrids 10–12, 18 and artemether (4) against Plasmodium berghei. (A) Efficacy of the drugs in reducing P. berghei parasitemia in C57BL/6 mice with a single dose. Mice showing 5–15% parasitemia were treated ip with 1.4 μmol of each drug, and parasitemia was checked 24 h later. The results are shown as the percentage of parasitemia in relation to parasitemia just before treatment (accounted as 100%): (**) p = 0.0268 (one-way ANOVA). (B) Individual curves of parasitemia in P. berghei infected mice just before (arrows) and after treatment with daily doses of hybrids 10–12 or 4 for 5 consecutive days. The dotted line indicates the time point of 24 h after the last (5th) dose.

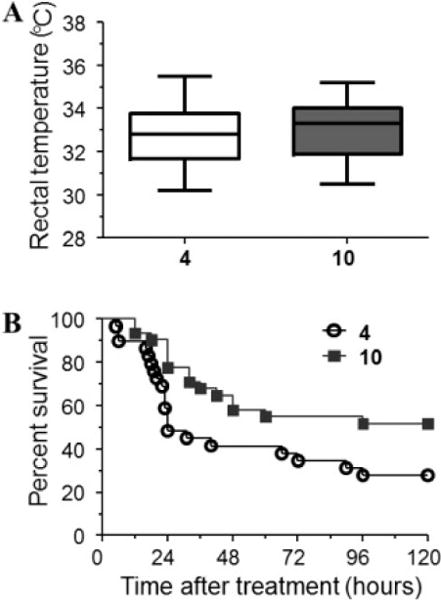

Efficacy of Hybrid Compounds in Rescuing Mice with Late-Stage ECM

The main rationale for developing artemisinin-NO-donor hybrid compounds comes from our studies showing that mice with ECM present marked cerebrovascular constriction leading to ischemia and hypoxia linked to low NO bioavailability.10,11 We have also shown that administration of exogenous NO improves cerebral microcirculatory physiology in P. berghei infected mice13–15 and that glyceryl trinitrate, a drug that generates NO, reverses cerebrovascular constriction and improves survival in mice with ECM.16 Artemisinin derivatives are potent, fast-acting antimalarial drugs, and intravenous artesunate is the mainstay treatment for human cerebral malaria.2 We hypothesized that the combination of artemisinin with NO-donors would bring together the potent antimalarial activity of the former with the vascular benefit of the latter and therefore be a more efficacious drug for treating cerebral malaria. We tested this hypothesis using the ECM preclinical model. Mice infected with P. berghei ANKA were allowed to develop clinical signs of cerebral malaria and then treated with artemether or hybrid 10. The objective criterion for treatment was development of hypothermia (rectal temperatures between 30 and 36 °C, Figure 4A), as this is an easily quantifiable clinical sign of neurological involvement in ECM allowing unbiased randomization of animals to the treatment groups.10 Parasitemia levels were also checked but not considered as a criterion for treatment. Animals in the two groups (artemether or hybrid 10) showed similar rectal temperatures (Figure 4A) and levels of parasitemia (artemether, 12.0 ± 5.35%; hybrid 10, 10.8 ± 3.54%; p = 0.5208) at the time of treatment. Hybrid 10 was chosen for this study, since it behaves as good antiplasmodial and vasodilator agent at low micromolar concentration. It contains the NO-donor methylfuroxan-3-carboxamide substructure present in CAS 1609 (4-hydroxymethyl-3-furoxancarboxamide) that was found to be an in vivo effective, long-lasting orally active, vasodilator agent devoid of tolerance.22 Derivatives 11, 12, and 18 display more potent vasodilating ability, which could potentially reflect a hypotensive response in already compromised mice. Mice with ECM treated with hybrid 10 showed a survival rate of 51.6%, which was markedly higher compared to the survival rate in the group of mice treated with artemether (27.5%) (Figure 4B). When comparing a subgroup of mice treated in better conditions, that is, only those with body temperatures above 32 °C, survival reached 63.6% of those treated with hybrid 10 against 33.3% of those treated with artemether (Figure S1). Also significantly, survival rate in the first critical 24 h was 77% in hybrid 10-treated mice against 48% in artemether-treated mice (Figure 4B). These data indicate that optimization of the treatment scheme may be able to further increase overall survival rates.

Figure 4.

Efficacy of artemether (4) and hybrid 10 in rescuing mice with late-stage cerebral malaria. Mice in both groups were treated when presenting similar clinical conditions as determined by body (rectal) temperature (A, no significant differences). Mice treated with hybrid compound 10 (n = 31) showed improved survival in relation to artemether-treated mice (n = 29) (B, 51.6% versus 27.5%, p = 0.0264, log-rank test).

The present study provides solid evidence that artemisinin-NO-donor hybrid compounds show great promise for improving the efficacy of the currently available mainstay treatment for cerebral malaria, which is intravenous artesunate.2 We have previously shown that artemether is capable of rapidly decreasing parasitemia and reversing vascular congestion in mice with late-stage ECM, clearing vessels from adherent leukocytes 24 h after a single dose.21 However, artemether had no effect in reversing cerebrovascular constriction.16 Therefore, even if parasites are cleared and vascular occlusion is reversed, ischemia will persist and hence constitute a critical obstacle for CM patient’s recovery. On the other hand, administration of glyceryl trinitrate potentiated the efficacy of artemether, significantly increasing survival of mice with ECM, and the benefit in survival was associated with reversal of cerebrovascular constriction reducing ischemia.16 These findings are consistent with the demonstration in the present study that hybrid compounds improve survival of mice with late-stage ECM.

■ CONCLUSION

We successfully developed a series of hybrid compounds in which the dihydroartemisinin scaffold was joined to furoxan and NONOate NO-donor moieties. This new class of compounds, which retains the potent antimalarial activity of the parent artemisinin and the vasoactive properties of the NO-donor moieties, may represent a powerful alternative to increase the efficacy of artesunate in treating cerebral malaria, improving survival and reducing sequelae by restoring proper cerebral blood flow along with rapid parasite killing. Additional studies to define optimal doses and delivery systems, pharmacokinetics and to characterize cerebral and systemic vascular responses to these drugs are warranted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01-AI82610 to L.J.M.C. and by University of Torino (Ricerca Locale, Grant 2013). L.J.M.C. is recipient of a Research Productivity Fellowship from CNPq and a CNE grant from Faperj, Brazil.

■ ABBREVIATIONS USED

- CM

cerebral malaria

- SM

severe malaria

- ECM

experimental cerebral malaria

- BBB

blood–brain barrier

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- AIBN

azabisisobutyronitrile

- NBS

N-bromosuccinimide

- mCPBA

m-chloroperbenzoic acid

- DCC

dicyclohexylcarbodiimide

- DMAP

4-dimethylaminopyridine

- ODQ

1H-[1,2,4]-oxadiazole[4,3-a]quinoxalin-1-one

- sGC

soluble guanylate cyclase

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01036.

Detailed experimental procedures of chemistry and biological studies (PDF)

Molecular formula strings (PDF)

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- 1.World Malaria Report 2014. WHO; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dondorp AM, Fanello CI, Hendriksen IC, Gomes E, Seni A, Chhaganlal KD, Bojang K, Olaosebikan R, Anunobi N, Maitland K, Kivaya E, Agbenyega T, Nguah SB, Evans J, Gesase S, Kahabuka C, Mtove G, Nadjm B, Deen J, Mwanga-Amumpaire J, Nansumba M, Karema C, Umulisa N, Uwimana A, Mokuolu OA, Adedoyin OT, Johnson WB, Tshefu AK, Onyamboko MA, Sakulthaew T, Ngum WP, Silamut K, Stepniewska K, Woodrow CJ, Bethell D, Wills B, Oneko M, Peto TE, von Seidlein L, Day NP, White NJ, AQUAMAT group Artesunate versus quinine in the treatment of severe falciparum malaria in African children (AQUAMAT): an open-label, randomised trial. Lancet. 2010;376:1647–1657. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61924-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carter JA, Mung’ala-Odera V, Neville BG, Murira G, Mturi N, Musumba C, Newton CR. Persistent neurocognitive impairments associated with severe falciparum malaria in Kenyan children. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:476–481. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.043893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mishra SK, Newton CR. Diagnosis and management of the neurological complications of falciparum malaria. Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:189–198. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gramaglia I, Sobolewski P, Meays D, Contreras R, Nolan JP, Frangos JA, Intaglietta M, van der Heyde HC. Low nitric oxide bioavailability contributes to the genesis of experimental cerebral malaria. Nat Med. 2007;12:1417–1422. doi: 10.1038/nm1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeo TW, Lampah DA, Gitawati R, Tjitra E, Kenangalem E, McNeil YR, Darcy CJ, Granger DL, Weinberg JB, Lopansri B, Price RN, Duffull SB, Celermajer DS, Anstey NM. Impaired nitric oxide bioavailability and L-arginine reversible endothelial dysfunction in adults with falciparum malaria. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2693–2704. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anstey NM, Weinberg JB, Hassanali MY, Mwaikambo ED, Manyenga D, Misukonis MA, Arnelle DR, Hollis D, McDonald MI, Granger DL. Nitric oxide in Tanzanian children with malaria: inverse relationship between malaria severity and nitric oxide production/nitric oxide synthase type 2 expression. J Exp Med. 1996;184:557–567. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.2.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lopansri BK, Anstey NM, Weinberg JB, Stoddard GJ, Hobbs MR, Levesque MC, Mwaikambo ED, Granger DL. Low plasma arginine concentrations in children with cerebral malaria and decreased nitric oxide production. Lancet. 2003;361:676–678. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12564-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yeo TW, Lampah DA, Tjitra E, Gitawati R, Darcy CJ, Jones C, Kenangalem E, McNeil YR, Granger DL, Lopansri BK, Weinberg JB, Price RN, Duffull SB, Celermajer DS, Anstey NM. Increased asymmetric dimethylarginine in severe falciparum malaria: association with impaired nitric oxide bioavail-ability and fatal outcome. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000868. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabrales P, Zanini GM, Meays D, Frangos JA, Carvalho LJ. Murine cerebral malaria is associated with a vasospasm-like microcirculatory dysfunction, and survival upon rescue treatment is markedly increased by nimodipine. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1306–1315. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cabrales P, Martins YC, Ong PK, Zanini GM, Frangos JA, Carvalho LJM. Cerebral tissue oxygenation impairment during experimental cerebral malaria. Virulence. 2013;4:686–697. doi: 10.4161/viru.26348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ong PK, Melchior B, Martins YC, Hofer A, Orjuela-Sánchez P, Cabrales P, Zanini GM, Frangos JA, Carvalho LJ. Nitric oxide synthase dysfunction contributes to impaired cerebroarteriolar reactivity in experimental cerebral malaria. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003444. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabrales P, Zanini GM, Meays D, Frangos JA, Carvalho LJ. Nitric oxide protection against murine cerebral malaria is associated with improved cerebral microcirculatory physiology. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1454–1463. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanini GM, Cabrales P, Barkho W, Frangos JA, Carvalho LJ. Exogenous nitric oxide decreases brain vascular inflammation, leakage and venular resistance during Plasmodium berghei ANKA infection in mice. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:66. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zanini GM, Martins YC, Cabrales P, Frangos JA, Carvalho LJ. S-nitrosoglutathione prevents experimental cerebral malaria. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7:477–487. doi: 10.1007/s11481-012-9343-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orjuela-Sanchez P, Ong PK, Melchior B, Zanini GM, Martins YC, Meays D, Frangos JA, Carvalho LJ. Transdermal glyceryl trinitrate as an effective adjunctive treatment with artemether for late stage experimental cerebral malaria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5462–5471. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00488-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Annex 1. WHO Model List of Essential Medicines. http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/essentialmedicines/EML2015_8-May-15.pdf. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2011/a95053_eng.pdf.

- 18.Bertinaria M, Guglielmo S, Rolando B, Giorgis M, Aragno C, Fruttero R, Gasco A, Parapini S, Taramelli D, Martins YC, Carvalho LJ. Amodiaquine analogues containing NO-donor substructures: synthesis and their preliminary evaluation as potential tools in the treatment of cerebral malaria. Eur J Med Chem. 2011;46:1757–1767. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller LH, Ackerman HC, Su X, Wellems TE. Malaria biology and disease pathogenesis: insights for new treatments. Nat Med. 2013;19:156–167. doi: 10.1038/nm.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orjuela-Sánchez P, Duggan E, Nolan J, Frangos JA, Carvalho LJ. A lactate dehydrogenase ELISA-based assay for the in vitro determination of Plasmodium berghei sensitivity to anti-malarial drugs. Malar J. 2012;11:366. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clemmer L, Martins YC, Zanini GM, Frangos JA, Carvalho LJ. Artemether and artesunate show the highest efficacies in rescuing mice with late-stage cerebral malaria and rapidly decrease leukocyte accumulation in the brain. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1383–1390. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01277-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bohn H, Brendel J, Martorana PA, Shoenafinger K. Cardiovascular Actions of the furoxan CAS 1609, a novel nitric oxide donor. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;114:1605–1612. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb14946.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.