Abstract

Previous research suggests that cognitive inflexibility prospectively increases vulnerability to suicidal ideation, but the specific cognitive factors that may explain the relation have not been examined empirically. The present study examined the brooding subtype of rumination and hopelessness as potential mediators of the prospective relation between cognitive inflexibility and suicidal ideation. Fifty-six young adults who completed a measure of cognitive inflexibility and suicidal ideation at baseline were followed up 2-3 years later and completed measures of brooding, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation. Cognitive inflexibility at baseline predicted suicidal ideation at follow up, adjusting for baseline ideation. This relation was mediated by brooding but not by hopelessness. However, there was an indirect relation between perseverative errors and suicidal ideation through brooding, followed by hopelessness, such that brooding was associated with greater hopelessness and hopelessness, in turn, was associated with greater suicidal ideation. Cognitive inflexibility may increase vulnerability to suicidal thinking because it is associated with greater brooding rumination, while brooding, in turn, is associated with hopelessness.

Keywords: cognitive inflexibility, rumination, hopelessness, suicidal ideation

1. Introduction

Emerging adults, or young adults between ages 18 and 29 (Arnett, 2000), have higher rates of suicidal thoughts, suicide planning, and suicide attempts in the United States than older adults (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). Accordingly, recent research has focused on determining predictors of suicidal behavior in young adulthood. Various cognitive characteristics, such as ruminative thinking, hopelessness, and poor problem solving, have been identified as risk factors for suicidal ideation and attempts in emerging adults (Smith et al., 2006; Surrence et al., 2009; Sargalska et al., 2011; Linda et al., 2012). However, much of this research is cross-sectional, with few longitudinal studies (e.g., Smith et al., 2006) examining cognitive predictors of suicidal ideation and attempts in emerging adulthood.

Previous evidence suggests that young people may think about and engage in suicidal behavior because they have difficulty generating solutions to problems (Schotte and Clum, 1982, 1987; Dixon et al., 1994). Being unable to engage in problem solving is thought to reflect cognitive inflexibility (Schotte and Clum 1982). Cognitive inflexibility is associated with maladaptive cognitions such as rumination (Davis and Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000) and has previously been found to predict increases in suicidal ideation at a 6-month follow up among individuals with a suicide attempt history (Miranda et al., 2012). The present longitudinal study sought to examine the mechanisms by which cognitive inflexibility might predict future suicidal ideation. Specifically, we examined levels of the brooding subtype of rumination and hopelessness as possible mediators of the prospective relation between cognitive inflexibility and suicidal ideation in a sample of emerging adults who were followed up over 2-3 years.

Cognitive inflexibility – defined as the inability to change decision-making in response to feedback from the environment (Lezak et al., 2012) – is associated with suicidal ideation and attempts, although evidence of this relation is mixed (see Jollant et al., 2011, for a review). For instance, one study of 25 depressed patients with current suicidal ideation and 28 depressed patients without suicidal ideation found that the patients with current suicidal ideation performed more poorly on tests of executive functioning, including those measuring cognitive flexibility, compared to the patients without suicidal ideation (Marzuk et al., 2005). Another study found that depressed patients with a history of a high-lethality suicide attempt exhibited more cognitive inflexibility as compared to both healthy controls and depressed patients with a history of a low-lethality attempt (McGirr et al., 2012). However, a study that compared seven recent suicide attempters to seven chronic pain patients and seven healthy controls found that suicide attempters showed poorer performance than controls on measures of verbal and design fluency but did not show differences on tests measuring cognitive flexibility (Bartfai et al., 1990). Additionally, a study that compared 20 suicide attempters to 27 psychiatric controls found no differences in cognitive flexibility between the groups (Ellis et al., 1992). More recently, a study that compared 72 depressed suicide attempters, 80 depressed non-attempters, and 56 non-patient controls found that suicide attempters performed more poorly on measures of attention and working memory but found no differences in other measures of executive functioning, including cognitive inflexibility (Keilp et al., 2013). All of these studies included clinical samples but were limited by being cross-sectional. However, a recent study by Miranda et al. (2012) found that cognitive inflexibility prospectively predicted suicidal ideation at 6-month follow up among a non-clinical sample of suicide attempters. However, it did not examine mechanisms that might explain this relation.

The diathesis-stress-hopelessness model of suicidality (Schotte and Clum, 1982, 1987) suggests that hopelessness is a mechanism through which cognitive inflexibility results in suicidal ideation. That is, being cognitively inflexible prevents individuals from engaging in coping responses that facilitate effective problem solving during times of stress, leading to higher degrees of hopelessness and suicidal ideation. Indeed, there is evidence that suicide ideators and attempters are characterized by poor problem-solving skills (Schotte and Clum, 1987). Furthermore, individuals high in hopelessness and suicidal intent have been found to perform more poorly on measures of social problem-solving (Schotte and Clum, 1982), and both social problem-solving deficits and perceived ineffectiveness in problem-solving are associated with higher levels of hopelessness and suicidal ideation (Schotte and Clum, 1982; Dixon et al., 1991; Dixon et al., 1994; Rudd et al., 1994; D’Zurilla et al., 1998).

Rumination – defined as the tendency to focus on one’s feelings of depression and on the causes, meanings, and consequences of one’s depression (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991) – has been identified as a predictor of suicidal ideation concurrently (Surrence et al., 2009) and over time (Smith et al., 2006; Miranda and Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007; O’Connor et al., 2007; O’Connor and Noyce, 2008) and as a correlate of suicide attempts (Crane et al., 2007; Surrence et al., 2009; see also Morrison and O’Connor, 2008). Rumination has also been studied in relation to cognitive inflexibility. Davis and Nolen-Hoeksema (2000) found that individuals who scored high on trait rumination showed more cognitive inflexibility, exhibited by greater perseverative errors on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (Heaton et al. 1993), compared to individuals who scored low on trait rumination. Furthermore, rumination is associated with poor problem solving (Lyubomirsky and Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995), which is thought to be a consequence of cognitive inflexibility (Clum et al., 1979). Dysphoric individuals induced to ruminate on their mood were found to generate less effective solutions to interpersonal problems compared to dysphoric individuals induced to distract themselves from their negative mood and also compared to non-dysphoric individuals (Lyubomirsky and Nolen-Hoeksema, 1995). Rumination thus seems to interfere with the ability to find solutions to problems (see Williams et al., 2005), and cognitive inflexibility appears to be implicated in ruminative thinking.

Cognitively inflexible individuals may ruminate because of an inability to focus on something other than their own negative emotions, thereby preventing the generation of alternate coping strategies (Davis and Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). Continued ruminative thinking may, in turn, lead individuals who ruminate to conclude that their circumstances are hopeless (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). Lam et al. (2003) found that depressed ruminators displayed higher levels of hopelessness than depressed non-ruminators. Smith et al. (2006) found that average hopelessness, measured over time, partially mediated the prospective relation between baseline levels of rumination and the presence of suicidal ideation over 2.5 years, and fully mediated the relation between rumination and duration of suicidal ideation over time among non-depressed college students who were at high versus low cognitive risk for depression. These findings suggested that rumination may contribute to the initiation of suicidal ideation and also to continued suicidal ideation through increased hopelessness. No research of which we are aware has examined whether rumination and hopelessness may explain the relation between cognitive inflexibility and suicidal ideation.

The present longitudinal study sought to extend this previous research by examining whether cognitive inflexibility would prospectively predict suicidal ideation at a 2-3-year follow up point in a sample of emerging adults, through its effects on the brooding subtype of rumination (see below) and on hopelessness. We hypothesized that cognitive inflexibility, measured at baseline, would predict suicidal ideation at 2-3-year follow up, and that this relation would be mediated by brooding rumination and hopelessness.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Fifty-six young adults (45 females), aged 18-22 (M = 18.4, SD = 0.1) recruited from a public university in the northeastern United States took part in this study for monetary compensation. Participants were recruited from a group of 96 individuals that took part in a study examining cognitive and emotional risk factors for suicidal behavior, including rumination (Surrence et al., 2009), problem solving (Linda et al., 2012), and emotion dysregulation (see Rajappa et al., 2012). A subsample of these 96 individuals (n = 45) also took part in a 6-month follow-up study that examined cognitive inflexibility as a prospective predictor of suicidal ideation (Miranda et al., 2012). Individuals were selected based on their self-reported history of suicidal ideation and attempts. Efforts were made to recruit an approximately equal number of individuals with and without a suicide attempt history at baseline, and 37 out of the 96 individuals had reported a lifetime history of a suicide attempt (see Rajappa et al., 2012; Surrence et al., 2009, for details). Participants from the original study were contacted 2-3 years after participation to take part in a follow up, and fifty-six individuals (58%) agreed to participate (Of these 56 individuals, 32 had also participated in the aforementioned 6-month follow-up study). This follow up was part of a larger study that included individuals who were part of the original sample of 1,011 individuals from which the present sample was recruited at baseline but who did not take part in the baseline portion of the present study (see Polanco-Roman and Miranda, 2013). The racial/ethnic composition of the present sample was 36% Asian, 23% White, 20% Hispanic, 9% Black, and 13% of other ethnicities. Twenty-five individuals who took part in the follow up had previously endorsed a suicide attempt history, and of these, 22 reported a suicide attempt history at the time of the study. There were no sex or racial/ethnic differences between individuals who did and did not take part in the follow-up study. However, individuals who participated in the follow up were younger, t(42.6) = 2.94, p < .01, and had higher levels of hopelessness, t(94) = 2.17, p < .05, and suicidal ideation, t(71.7) = 2.66, p < .05, than did those who did not take part (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and scores on symptom measures at baseline among participants who did and did not participate in the follow up

| Participated in the follow up (N = 56) | Not in follow up (N = 40) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | X (%) | Female | 45 | (80%) | 28 | (70%) |

| Male | 11 | (20%) | 12 | (30%) | ||

| Ethnicity | Asian | 20 | (36%) | 10 | (25%) | |

| White | 13 | (23%) | 16 | (40%) | ||

| Hispanic | 11 | (20%) | 11 | (28%) | ||

| Black | 5 | (9%) | 2 | (5%) | ||

| Other | 7 | (13%) | 1 | (3%) | ||

| Mood/anxiety Dx | 16 | (29%) | 7 | (18%) | ||

| Suicide Attempt (SHBQ) | 22 | (40%) | 11 | (31%) | ||

| Age** | M (SD) | 18.4 | (0.8) | 19.8 | (3.0) | |

| Brooding~ | 13.0 | (3.4) | 11.8 | (4.0) | ||

| Hopelessness (BHS)* | 6.5 | (4.9) | 4.5 | (3.7) | ||

| Depressive Symptoms (PHQ, items 1-8)~ | 9.6 | (4.9) | 10.1 | (4.7) | ||

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | ||||||

| Total Correct | 69.6 | (10.8) | 70.7 | (7.8) | ||

| Total Errors | 22.5 | (20.7) | 17.7 | (9.5) | ||

| Perseverative Responses | 10.2 | (7.4) | 9.3 | (5.5) | ||

| Perseverative Errors | 9.5 | (6.4) | 8.7 | (4.9) | ||

| Conceptual Level Responses | 64.1 | (13.7) | 66.5 | (5.6) | ||

| Categories Completed* | 5.6 | (1.4) | 6.0 | (0.2) | ||

| Failure to Maintain Set | 0.6 | (0.7) | 0.4 | (0.5) | ||

| Learning to Learn | 0.5 | (3.8) | 0.2 | (2.6) | ||

| Suicidal Ideation (BSS)* | 1.7 | (3.4) | 0.4 | (1.2) | ||

Note.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01

BHS = Beck Hopelessness Scale; PHQ = Patient Health Questionnaire; BSS = Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation; SHBQ = Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire.

Indicates measure was administered prior to the baseline study session.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Cognitive inflexibility

The computerized version of the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST; Heaton et al., 1993) was used to assess cognitive inflexibility at baseline. The task is designed to test abstract reasoning and the ability to shift cognitive strategies when presented with changes in sorting rules. Participants are asked to match a target card to one of four key cards by number, shape, or color. However, rather than being provided with the sorting rule, participants must infer the rule based on feedback that they receive (i.e., whether their response was correct or incorrect). After a predetermined number of successful matches, the card sorting rule changes and participants must change their strategy accordingly in order to correctly match the cards. The number of perseverative errors participants make during the task measures cognitive inflexibility. These errors occur when participants continue to use an old sorting rule despite receiving feedback that their response is incorrect. It should be noted that perseverative errors on the WCST have previously been found to be uncorrelated with working memory (Lehto, 1996; Stratta et al., 1997; Davis and Nolen-Hoksema, 2000).

2.2.2. Brooding rumination

Brooding was assessed using the Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS; Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991). The 22-item RRS is a self-report questionnaire that inquires about how often individuals think about the causes, meanings, and consequences of their mood when they feel sad or depressed. The Brooding subscale, consisting of 5 items, measures the degree to which individuals dwell on their negative moods, and is considered to be a maladaptive form of rumination (see Treynor et al., 2003; Schoofs et al., 2010). The Brooding subscale was used instead of the entire RRS, because items on this subscale do not overlap with symptoms of depression, as some items on the RRS have been found to do (Treynor et al., 2003). The RRS was administered prior to the baseline assessment as part of the initial screening of the 1,011 individuals from which the present sample was selected, and it was administered again at follow up. Scores on the Brooding subscale of the RRS ranged from 5 to 19 at baseline (M = 13.0, SD = 3.4) and from 5 to 19 (M = 11.4, SD = 3.6) at follow up, and Cronbach’s alpha in the present sample was .74 at baseline and .81 at follow up.

2.2.3. Hopelessness

The Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS; Beck and Steer, 1988) was used to assess negative expectations about the future. This 20-item self-report questionnaire is presented in a true/false format and can have scores that range from 0 to 20. Scores from the 56 participants ranged from 0 to 20 (M = 6.5, SD = 4.9) at baseline and from 0 to 17 (M = 5.1, SD = 4.9) at follow up. Cronbach’s alpha in the present sample was .88 at baseline and .91 at follow up.

2.2.4. Suicidal ideation

The Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS; Beck and Steer, 1991) is a 21-item self-report measure that assesses passive and active suicidal ideation, including wish to die, suicidal plans, and access to means during the previous week. Total scores (ranging from 0 to 38) are computed by summing items 1-19. In the present sample, the scores ranged from 0 to 14 at baseline (M = 1.7, SD = 3.4) and 0 to 12 at follow up (M = 1.3, SD = 3.0). Cronbach’s alpha in the present sample was .96 at baseline and .98 at follow up.

2.2.5. History of self-harm

History of self-harm, including suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury, was assessed at baseline using the Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire (SHBQ; Gutierrez et al., 2001). The SHBQ is designed for use with young adults from a non clinical population. It inquires about whether individuals have ever intentionally tried to hurt themselves (“Have you ever hurt yourself on purpose?”) and whether they have ever attempted to kill themselves (“Have you ever attempted suicide?”), including number of previous attempts and the method of their most recent suicide attempt. In the present sample, twenty-two individuals reported a suicide attempt history on the SHBQ, and methods of the most recent attempt included ingestion (n = 9), cutting (n = 6), and other methods (n = 7), including jumping, suffocation, and strangulation.

2.2.6. Depressive symptoms

Symptoms of depression were examined using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ; Spitzer et al., 1999), a 9-item self-report measure that assesses symptoms, as experienced in the previous two weeks, consistent with a diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder, as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994). Each question is rated on a scale from 0 to 3, and a total score is computed by summing the items. Item 9, which inquires about thoughts of self-harm, was excluded from the total score because of its overlap with suicidal ideation. The PHQ-9 was administered prior to the baseline assessment as part of the initial screening of the 1,011 individuals from which the present sample was selected, and it was administered again at follow up. Scores on items 1-8 of the PHQ ranged from 0 to 20 (M = 9.6, SD = 4.9) at the initial assessment and from 0 to 17 (M = 6.8, SD = 4.0) at follow up, with Cronbach’s alpha .83 at baseline and .79 at follow up.

2.2.7. Mood or anxiety diagnosis

The presence of a mood or anxiety diagnosis was assessed using the young adult version of the Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (C-DISC; Shaffer et al., 2000). This structured interview is designed to be administered by lay interviewers and uses a computer algorithm to yield diagnoses consistent with the DSM-IV. In the present study, trained post-baccalaureate and Masters-level interviewers administered the C-DISC, and the following diagnoses were assessed with respect to the previous year: Major Depressive Disorder, Dysthymic Disorder, Mania, Hypomania, Social Phobia, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder.

2.3. Procedure

Participants completed two assessments 2-3 years apart. Ninety-six individuals who had participated in an initial screening of 1011 college undergraduates from an introductory psychology course took part in the present study 3-4 weeks after the initial screening, based on their endorsement of suicidal ideation, a suicide attempt history, or neither ideation nor an attempt. Participants completed the BHS, BSS, and a computerized version of the WCST at baseline. Approximately 2-3 years later, the 96 participants were invited to participate in the present follow-up study. Fifty-six individuals were successfully recruited and completed self-report questionnaires assessing hopelessness, depressive symptoms, rumination, and suicidal ideation. After each session, research assistants completed a risk assessment procedure before debriefing participants. Individuals who reported a recent suicide attempt or current suicidal ideation were interviewed by a licensed clinical psychologist and referred for further assessment, if necessary. All participants were provided with a list of local treatment referrals at the conclusion of each session. Participants received $50 or research credit in their psychology class for taking part in the baseline study session and $25 for taking part in the follow-up study session. All procedures were given full board approval by an Institutional Review Board.

3. Results

3.1. Relation between Wisconsin Card Sorting test scores and self-report measures

Zero-order correlations between subscales of the WCST and primary study measures are shown in Table 2a. None of the WCST subscales was significantly associated with suicidal ideation. However, both number of categories completed (out of a possible total of 6) and conceptual level responses at baseline were negatively correlated with brooding and hopelessness at follow up. We also computed partial correlations between WCST scales and brooding, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation at follow up, adjusting for baseline levels of each respective variable. As shown in Table 2b, number of perseverative errors on the WCST was significantly and positively associated with suicidal ideation, while categories completed and conceptual responses were significantly and negatively associated with brooding, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation. We should note that when examining whether there were differences on WCST scales between participants with versus without a history of a suicide attempt, there was only a difference on the WCST Learning to Learn score, which was significantly higher among individuals without a suicide attempt history (M = 1.3, SD = 4.3), compared to individuals with a suicide attempt history (M = −0.9, SD = 2.3), t(48) = 2.04, p < 0.05.

Table 2a.

Zero-order correlations between scores on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and self-report measures

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pers Error (1) | … | ||||||||||

| 2. Conceptual Resp. (1) | −0.50** | … | |||||||||

| 3. Categories Completed (1) | −0.71** | 0.89** | … | ||||||||

| 4. Maint. set (1) | 0.16 | 0.34* | −0.01 | … | |||||||

| 5. Learning to Learn (1) | 0.07 | 0.30* | 0.45** | 0.29* | … | ||||||

| 6. Suicide Attempt (1) | −0.12 | −0.12 | −0.09 | −0.08 | −0.28* | … | |||||

| 7. Brooding (~) | 0.13 | −0.20 | −0.16 | −0.24 | −0.09 | 0.15 | … | ||||

| 8. Brooding (2) | 0.23 | −0.38** | −0.32* | −0.17 | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.44** | … | |||

| 9. Hopeless (1) | 0.06 | −0.15 | −0.16 | −0.06 | 0.003 | 0.24 | 0.38** | 0.27** | … | ||

| 10. Hopeless (2) | 0.25 | −0.31* | −0.37** | −0.08 | −0.07 | 0.24 | 0.39** | 0.55** | 0.53** | … | |

| 11. Ideation (1) | −0.20 | 0.05 | −0.12 | −0.02 | −0.07 | 0.47** | 0.24 | 0.39** | 0.42** | 0.18 | … |

| 12. Ideation (2) | 0.17 | −0.22 | −0.24 | 0.03 | −0.01 | 0.39** | 0.12 | 0.53** | 0.26+ | 0.57** | 0.46** |

p = 0.05;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01

Measured prior to baseline

Measured at baseline

Measured at follow up

Table 2b.

Partial correlations between scores on the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test and brooding, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation at follow up, adjusting for baseline levels

| Brooding | Hopelessness | Suicidal Ideation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perseverative Errors | 0.19 | 0.26 | 0.29* |

| Conceptual Level Responses | −0.33* | −0.28* | −0.28* |

| Categories Completed | −0.28* | −0.34* | −0.33* |

| Failure to Maintain Set | −0.07 | −0.05 | 0.04 |

p < 0.05

Note: Total errors, perseverative responses, and non-perseverative errors had correlations of 0.87, 0.99, and 0.75, respectively, with perseverative errors, and thus were excluded from correlation tables to reduce redundancy.

3.2. Examining brooding rumination and hopelessness as mediators

We hypothesized that cognitive inflexibility, measured at baseline, would predict suicidal ideation at follow up, and that both brooding rumination and hopelessness (also measured at follow up) would mediate this prospective relation. Examination of scatterplots did not suggest a curvilinear relation between the predictors of interest and suicidal ideation. When there is an approximately linear relation between variables, an ordinary least squares regression coefficient will yield an unbiased estimate of the population value (Fox, 1997). However, to address potential bias in our significance testing due to non-normality of the distribution of suicidal ideation scores, we used bootstrapping to construct confidence intervals around regression coefficients, given that the assumption of normality is not necessary for bootstrapping (see Zhu, 1997).

As outlined by MacKinnon et al. (2002), mediation may be tested when the predictor (cognitive inflexibility) relates to both the mediator (brooding, hopelessness) and outcome variable (suicidal ideation). A relation between the predictor (cognitive inflexibility) and outcome (suicidal ideation) may or may not be present. Note that because a mediator should follow the predictor (Baron and Kenny, 1986), rumination at follow up, rather than at baseline, was included in these analyses (given that the initial assessment of brooding rumination was made during the initial screening from which the baseline sample was selected, and this initial assessment session occurred up to one month before the baseline administration of the WCST). Bias-corrected confidence intervals around the indirect relations between cognitive inflexibility and suicidal ideation through brooding and hopelessness were calculated using a bootstrapping procedure with n = 1000 resamples (Hayes, 2012).

Three linear regression analyses were performed to assess whether cognitive inflexibility (predictor) at baseline predicted brooding (mediator), hopelessness (mediator), and suicidal ideation (outcome variable) at follow up, respectively, adjusting for suicidal ideation at baseline, suicide attempt history at baseline, and depressive symptoms at baseline. Cognitive inflexibility was a statistically significant predictor of brooding (b = 0.17, S.E. = 0.07, β = 0.32, p < .05), hopelessness (b = 0.22, S.E. = 0.10, β = 0.29, p < .05), and suicidal ideation (b = 0.13, S.E. = 0.06, β = 0.27, p < .05) at follow up.

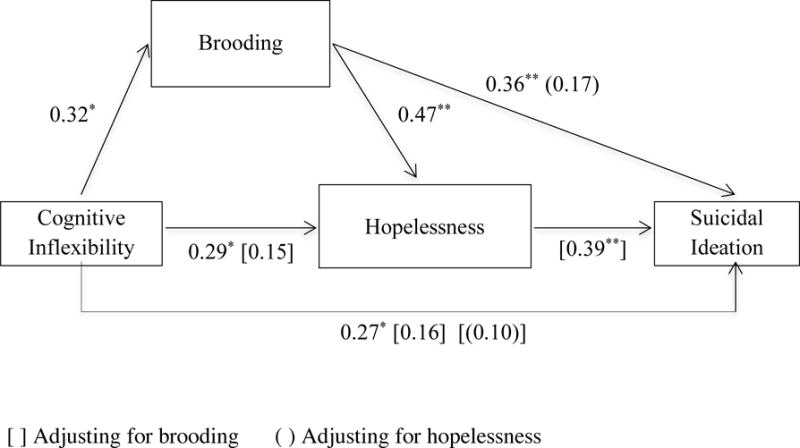

A hierarchical linear regression was then conducted in which cognitive inflexibility (first step), brooding at follow up (second step), and hopelessness at follow up (third step) were examined as predictors of suicidal ideation, adjusting for baseline suicidal ideation, baseline suicide attempt history, and baseline depressive symptoms. As noted above, cognitive inflexibility significantly predicted suicidal ideation at follow up. Brooding significantly predicted ideation in the second step, but cognitive inflexibility no longer predicted ideation after adjusting for brooding. Hopelessness significantly predicted ideation in the third step, with brooding no longer a significant predictor of ideation after adjusting for hopelessness (see Table 3). Standardized regression coefficients for these effects are summarized in Figure 1. These relations held even when depressive symptoms at follow up were added to the analysis (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Hierarchical linear regression predicting suicidal ideation at follow up

| Block | Predictor | b | S.E. | β | p | Adjusted R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Suicidal Ideation (1)** | 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.40 | < 0.01 | 0.27** |

| Suicide Attempt History (1) | 1.50 | 0.81 | 0.24 | 0.07 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms (1) | −0.003 | 0.07 | −0.01 | 0.97 | ||

| Cognitive Inflexibility (1)* | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.27 | 0.03 | ||

|

| ||||||

| 2 | Suicidal Ideation (1) | 0.23 | 0.12 | 0.26 | 0.06 | 0.35** |

| Suicide Attempt History (1) | 1.33 | 0.76 | 0.22 | 0.09 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms (1) | −0.03 | 0.07 | −0.05 | 0.65 | ||

| Cognitive Inflexibility (1) | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.18 | ||

| Brooding (2)** | 0.30 | 0.11 | 0.36 | < 0.01 | ||

|

| ||||||

| 3 | Suicidal Ideation (1)* | 0.26 | 0.11 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.45** |

| Suicide Attempt History (1) | 0.93 | 0.72 | 0.15 | 0.20 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms (1) | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.11 | 0.31 | ||

| Cognitive Inflexibility (1) | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.36 | ||

| Brooding (2) | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.19 | ||

| Hopelessness (2)** | 0.24 | 0.08 | 0.39 | < 0.01 | ||

|

| ||||||

| 4 | Suicidal Ideation (1) | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.57** |

| Suicide Attempt History (1) | 1.26 | 0.64 | 0.20 | 0.06 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms (1) | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.60 | ||

| Cognitive Inflexibility (1) | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.10 | 0.30 | ||

| Brooding (2)* | 0.27 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 0.01 | ||

| Hopelessness (2)** | 0.30 | 0.07 | 0.47 | < 0.01 | ||

| Depressive Symptoms (2)** | −0.34 | 0.09 | −0.44 | < 0.01 | ||

Note.

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01

Baseline

Follow up

b = Unstandardized regression coefficient.

β = Standardized regression coefficient.

Figure 1.

Cognitive inflexibility significantly predicts brooding rumination, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation at follow up, adjusting for baseline suicidal ideation. Brooding mediates the relation between cognitive inflexibility and hopelessness and between cognitive inflexibility and suicidal ideation. Hopelessness mediates the relation between brooding and suicidal ideation. Values shown are standardized regression coefficients.

Indirect effects were tested using bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals, calculated using a bootstrapping procedure (with n = 1,000 resamples), as bootstrapping does not assume normality of a distribution (Preacher and Hayes, 2008). Effects were estimated using the PROCESS procedure (Hayes, 2012). Indirect effects were considered statistically significant when their confidence intervals did not include zero. The following indirect effects were tested: 1) the indirect effect of cognitive inflexibility on suicidal ideation through brooding; 2) the indirect effect of cognitive inflexibility on suicidal ideation through hopelessness; and 3) the indirect effect of cognitive inflexibility on suicidal ideation through brooding and hopelessness (see Table 4). There was an indirect effect of cognitive inflexibility on suicidal ideation through brooding (95% CI = 0.0004 – 0.11), but not through hopelessness (95% CI = −0.02 – 0.10), in models that also adjusted for baseline suicidal ideation, baseline suicide attempt history, and for depressive symptoms at both baseline and follow up. There was an indirect effect of cognitive inflexibility on suicidal ideation through brooding and hopelessness (i.e., a path from cognitive inflexibility to brooding, from brooding to hopelessness, and from hopelessness to suicidal ideation (95% CI = 0.002 – 0.07).

Table 4.

Indirect effects of cognitive inflexibility at baseline on suicidal ideation at follow up through brooding and hopelessness at follow up

| Path | Indirect Effect | 95% CI+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | S.E.+ | (Lower, Upper) | |

| Cog. Inflex. (1) ➔ Brooding (2) ➔ Suicidal Ideation (2) |

0.04 | 0.03 | (0.0004, 0.11) |

| Cog. Inflex. (1) ➔ Hopelessness (2) ➔ Suicidal Ideation (2) |

0.03 | 0.03 | (−0.02, 0.10) |

| Cog. Inflex. (1) ➔ Brooding (2) ➔ Hopelessness (2) ➔ Suicidal Ideation (2) |

0.02 | 0.02 | (0.002, 0.07) |

Estimated using bootstrapping with n = 1,000 samples. Covariates include baseline suicidal ideation, suicide attempt history, baseline depressive symptoms, and depressive symptoms at follow up.

Baseline

Follow up

4. Discussion

Previous research has shown that cognitive inflexibility is associated with both suicidal ideation and attempts (Marzuk et al., 2005; McGirr et al., 2012), and prospectively predicts suicidal ideation at 6-month follow up (Miranda et al., 2012). The present study sought to extend these findings by examining the longitudinal relation between cognitive inflexibility and ideation over a longer follow-up period, and by exploring whether brooding rumination and hopelessness would mediate this relation. Our results partially supported our hypotheses: cognitive inflexibility predicted suicidal ideation at 2-3 year follow up, and brooding mediated the relation between cognitive inflexibility and suicidal ideation. While there was no statistically significant path from cognitive inflexibility to suicidal ideation through hopelessness, there was an indirect path that went from cognitive inflexibility to brooding, from brooding to hopelessness, and from hopelessness to suicidal ideation.

In addition to underscoring the longitudinal association between cognitive inflexibility and suicidal ideation, the present findings also lend support to the diathesis-stress-hopelessness model of suicidality (Schotte and Clum, 1982). This model suggests that mental inflexibility may be a cognitive vulnerability during times of stress that leads to increased hopelessness and suicidal ideation. In the original model, impaired problem solving was suggested as a mechanism through which cognitive inflexibility impacts hopelessness and ideation. Although the present study did not include a measure of stress, its findings implicate another possible mechanism from cognitive inflexibility to hopelessness and ideation: brooding rumination. That is, our results suggest that cognitive inflexibility may lead to higher levels of future suicidal ideation through its effect on brooding rumination, a finding that is consistent with previous research demonstrating an association between brooding and suicidal ideation (e.g., Miranda and Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007; O’Connor and Noyce, 2008). Brooding rumination, in turn, may impact future suicidal ideation by increasing an individual’s hopelessness.

Cognitive inflexibility may lead to brooding in response to a negative mood, because individuals with decreased mental flexibility may have difficulty disengaging from thoughts about the causes and consequences of their negative mood. Furthermore, previous research suggests that people who tend to ruminate in response to their negative moods often attribute their rumination to the process of trying to understand and solve their problems (e.g., Papageorgiou and Wells, 2003). This attribution, along with the inability to shift cognitive set in response to changing environmental feedback (e.g., a cognitive strategy, such as brooding, which does not lead to resolution of a problem), may lead individuals to continue to engage in an ineffective cognitive response such as brooding.

Contrary to prediction, we found that hopelessness did not mediate the prospective relation between cognitive inflexibility and suicidal ideation, although it was part of the path from brooding rumination to ideation. The latter finding is consistent with prior research suggesting that brooding rumination is related to suicidal ideation over time (Miranda and Nolen-Hoeksema, 2007), and that hopelessness may help to explain the link between rumination and suicidal ideation (Smith et al., 2006). Continued rumination in response to a negative mood may decrease an individual’s capacity to generate alternative solutions or take action to relieve the distress. This lack of problem resolution may, in turn, provide individuals with evidence that their situation is hopeless, as has previously been suggested (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). These feelings of hopelessness may then increase vulnerability to suicidal ideation. Future research is needed to further examine the inter-relations between rumination, impaired problem solving, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation.

Our findings also lend support to models of suicide that suggest a role for cognitive constriction in the emergence of suicidal thoughts and behaviors (Wenzel and Beck, 2008). Much as individuals who are cognitively inflexible may have difficulty disengaging from rumination about the causes of their negative mood, these individuals may also have difficulty disengaging from their thoughts about suicide. Wenzel and Beck (2008) suggest a cognitive model of suicidality in which suicidal individuals exhibit a narrowing of attentional focus, such that suicide is perceived as the only solution to their distress. It is possible that cognitive inflexibility and associated brooding may facilitate this type of cognitive constriction. A perceived lack of alternate solutions to their distress may then lead individuals to feelings of hopelessness and an eventual focus on suicide as a solution.

These findings are also compatible with research suggesting a link between suicidal behavior and impulsivity (e.g., Nock et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2009). Joiner (2005) suggests that individuals acquire the ability to engage in lethal self-harm through painful and provocative life experiences. A recent study found that the experience of painful and provocative life events statistically mediated the relation between impulsivity and the acquired ability for suicide (Bender et al., 2011). An inability to disengage from a negative mood may lead individuals to engage in such provocative behaviors (e.g., aggressive behaviors, non-suicidal self-injury), thus increasing risk for suicidality. Future research should examine whether cognitive inflexibility and brooding affect the tendency to respond impulsively.

Some study limitations should be noted. Despite the longitudinal nature of the study, the sample size was small, primarily female, and was not a clinical sample. Thus, these findings might not be generalizable to a general community or to a clinical sample of emerging adults. Secondly, the racial/ethnic composition of the sample, although fairly representative of the college setting from which it was drawn, may not be representative of the overall population of emerging adults with suicidal ideation. At the same time, the racial/ethnic diversity of the sample is a strength. A third limitation was the modest rate of participation in the follow up, as only 56 (58%) of the original 96 individuals who took part in the baseline assessment were followed up 2-3 years later. We were thus unable to examine whether a suicide attempt history moderated the mediated relations in this study. Other limitations included the use of a self-report measure to assess suicidal ideation, rather than a clinical interview, and the fact that the study did not test for the possible influence of other variables thought to explain the relation between cognitive inflexibility and ideation, such as problem-solving (Schotte and Clum, 1982, 1987) or impulsivity (Wu et al., 2009). In addition, we used number of perseverative errors on the WCST to quantify cognitive inflexibility. Previous research examining the relation between suicidal ideation/attempts and performance on the WCST has yielded mixed findings (see Jollant et al., 2011, for a review; Keilp et al., 2013). We also did not include measures of lower-order cognitive processes, such as attention and working memory, which have been shown to be affected among suicide attempters (Keilp et al., 2013). Future studies should include such measures, along with other measures of cognitive inflexibility, in conjunction with the WCST, to more conclusively establish a relation between cognitive inflexibility and suicidal ideation and behavior. Finally, the present study suggested associations between other WCST scales (e.g., conceptual level responses) and measures of brooding rumination and hopelessness (specifically, negative associations), and these relations may warrant future research.

The fact that the present study assessed self-focused rumination (i.e., brooding) in relation to a negative mood is another study limitation. Future research may benefit from examining ruminative thinking that occurs independently of a negative mood. In addition, future research should consider other types of rumination to which these findings may generalize. For instance, previous research suggests that hopelessness-related cognitions may arise through rumination about the future (see Andersen and Limpert, 2001). Perhaps cognitive inflexibility is part of a path from other such types of rumination to hopelessness and suicidal ideation. Finally, because the first brooding rumination assessment was completed in the initial screening session up to a month before the baseline assessment of cognitive inflexibility, we were limited to examining brooding and hopelessness at follow up as mediators of the relation between cognitive inflexibility and suicidal ideation and were thus unable to draw conclusions about the direction of the relation between these mediators and suicidal ideation. Future research should examine cognitive inflexibility, rumination, and hopelessness at multiple time points.

The present study has implications for clinical intervention. Our findings suggest that brooding rumination may arise from cognitive inflexibility and may explain why cognitive inflexibility increases risk for future suicidal ideation. Furthermore, brooding may increase vulnerability to suicidal ideation through increased hopelessness, which has previously been implicated in risk for suicidal ideation and attempts. Deficiencies in the ability to develop alternative solutions to problems may play a role in this process, arising from cognitive inflexibility and its effect on rumination. Clinicians can benefit from this knowledge by focusing on therapeutic interventions that decrease brooding rumination (e.g., Watkins, 2009) and increase problem-solving skills in cognitively inflexible patients. Decreased brooding and more effective problem-solving skills may then lead to lower levels of hopelessness, as individuals learn to develop alternative coping strategies.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded, in part, by NSF ADVANCE Institutional Transformation Award 0123609, NIH Grant GM060665, and by PSC-CUNY Grant PSCREG-41-1351. Thanks to Monique Fontes, Valerie Khait, Alyssa Wheeler, Marta Krajniak, Wendy Linda, Brett Marroquín, Lillian Polanco-Roman, and Kristin Rajappa for their assistance with data collection. Thanks to Sa Shen (New York State Psychiatric Institute) for comments on a previous version of this paper.

References

- Andersen SM, Limpert C. Future-event schemas: Automaticity and rumination in major depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2001;25:311–333. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55:469–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual strategic and statistic considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartfai A, Winbord IM, Nordström P, Åsberg M. Suicidal behavior and cognitive flexibility: Design and verbal fluency after attempted suicide. Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior. 1990;20:254–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Hopelessness Scale Manual. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA. Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation. Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: TX: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bender TW, Gordon KH, Bresin K, Joiner TE., Jr Impulsivity and suicidality: The mediating role of painful and provocative experiences. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2011;129:301–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Suicidal thoughts and behavior among adults aged ≥ 18 years—United States, 2008-2009. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;60(SS13):1–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clum GA, Patsiokas AT, Luscomb RL. Empirically based comprehensive treatment program for parasuicide. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1979;47:937–945. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.47.5.937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane C, Barnhofer TJ, Williams JMG. Reflection, brooding, and suicidality: A preliminary study of different types of rumination in individuals with a history of major depression. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;46:497–504. doi: 10.1348/014466507X230895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RN, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Cognitive inflexibility among ruminators and nonruminators. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2000;24:699–711. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon WA, Heppner PP, Anderson WP. Problem-solving appraisal, stress, hopelessness, and suicide ideation in a college population. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1991;38:51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon WA, Heppner PP, Rudd MD. Problem-solving appraisal, hopelessness, and suicide ideation: Evidence for a mediational model. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1994;41:91–98. [Google Scholar]

- D’Zurilla TJ, Chang EC, Nottingham EJ, Faccini L. Social problem-solving deficits and hopelessness, depression, and suicidal risk in college students and psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1998;54:1091–1107. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(199812)54:8<1091::aid-jclp9>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis TE, Berg RA, Franzen MD. Neuropsychological performance and suicidal behavior in adult psychiatric inpatients. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1992;75:639–647. doi: 10.2466/pms.1992.75.2.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J. Applied Linear Regression Analysis, Linear Models, and Related Methods. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez PM, Osman A, Barrios FX, Kopper BA. Development and initial validation of the Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment. 2001;77:475–490. doi: 10.1207/S15327752JPA7703_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable moderation, mediation, and conditional process modeling. 2012 [White paper]. Available from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

- Heaton RK, Chelune GJ, Talley JL, Kay GC, Curtiss G. Wisconsin Card Sorting Test Manual: Revised and Expanded. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner T. Why People Die by Suicide. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jollant F, Lawrence NL, Olié E, Guillaume S, Courtet P. The suicidal mind and brain: a review of neuropsychological and neuroimaging studies. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry. 2011;12:319–339. doi: 10.3109/15622975.2011.556200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilp JG, Gorlyn M, Russell M, Oquendo MA, Burke AK, Harkavy-Friedman J, Mann JJ. Neuropsychological function and suicidal behavior: Attention control, memory and executive dysfunction in suicide attempt. Psychological Medicine. 2013;43:539–551. doi: 10.1017/S0033291712001419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam D, Schuck N, Smith N, Farmer A, Checkley S. Response style, interpersonal difficulties and social functioning in major depressive disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2003;75:279–283. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(02)00058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehto J. Are executive function tests dependent on working memory capacity. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 1996;49:29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Bigler ED, Tranel D. Neuropsychological Assessment. 5th. Oxford University Press; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Linda WP, Marroquín B, Miranda R. Active and passive problem solving as moderators of the relation between negative life event stress and suicidal ideation among suicide attempters and non-attempters. Archives of Suicide Research. 2012;13:183–197. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2012.695233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky S, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Effects of self-focused rumination on negative thinking and interpersonal problem solving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:176–190. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marzuk PM, Hartwell N, Leon AC, Portera L. Executive functioning in depressed patients with suicidal ideation. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinivica. 2005;112:294–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGirr A, Dombrovski AY, Butters MA, Clark L, Szanto K. Deterministic learning and attempted suicide among older depressed individuals: Cognitive assessment using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;46:226–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Gallagher M, Bauchner B, Vaysman R, Marroquín B. Cognitive inflexibility as a prospective predictor of suicidal ideation among young adults with a suicide attempt history. Depression and Anxiety. 2012;29:180–186. doi: 10.1002/da.20915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Brooding and reflection: Rumination predicts suicidal ideation at 1-year follow-up in a community sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:3088–3095. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison R, O’Connor RC. A systematic review of the relationship between rumination and suicidality. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38:523–538. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.5.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angemeyer M, Beautrais, Bruffaerts R, Chiu WT, de Girolamo G, Gluzman S, de Graaf R, Gureje O, Haro JM, Huang Y, Karam E, Kessler RC, Lepine JP, Levinson D, Medina-Mora ME, Ono Y, Posada-Villa J, Williams D. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;192:98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:569–582. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RC, Noyce R. Personality and cognitive processes: Self-criticism and different types of rumination as predictors of suicidal ideation. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46:392–401. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor DB, O’Connor RC, Marshall R. Perfectionism and psychological distress: Evidence of the mediating effects of rumination. European Journal of Personality. 2007;21:429–452. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou C, Wells A. An empirical test of a clinical metacognitive model of rumination and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:261–273. [Google Scholar]

- Polanco-Roman L, Miranda R. Culturally-related stress, hopelessness, and vulnerability to depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation in emerging adulthood. Behavior Therapy. 2013;44:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in simple and multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajappa K, Gallagher M, Miranda R. Emotion dysregulation and vulnerability to suicidal ideation and attempts. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2012;36:833–839. [Google Scholar]

- Rudd MD, Rajab H, Dahm PF. Problem-solving appraisal in suicide ideators and attempters. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1994;64:136–149. doi: 10.1037/h0079492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargalska J, Miranda R, Marroquín B. Being certain about an absence of the positive: Specificity in relation to hopelessness and suicidal ideation. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2011;4:105–117. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoofs H, Hermans D, Raes F. Brooding and reflection as subtypes of rumination: Evidence from confirmatory factor analysis in nonclinical samples using the Dutch Ruminative Response Scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavior Assessment. 2010;32:609–617. [Google Scholar]

- Schotte DE, Clum GA. Suicidal ideation in a college population: A test of a model. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:690–696. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.50.5.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schotte DE, Clum GA. Problem solving skills in suicidal psychiatric patients. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:49–54. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.1.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JM, Alloy LB, Abramson LY. Cognitive vulnerability to depression, rumination, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation: Multiple pathways of self-injurious thinking. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2006;36:443–454. doi: 10.1521/suli.2006.36.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ Primary Care Study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratta P, Daneluzzo E, Prosperini P, Bustini M, Mattei P, Rossi A. Is Wisconsin Card Sorting Test performance related to “working memory” capacity? Schizophrenia Research. 1997;27:11–19. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(97)00090-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surrence K, Miranda R, Marroquín B, Chan S. Brooding and reflective rumination among suicide attempters: Cognitive vulnerability to suicidal ideation. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:803–808. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins ER. Depression rumination: Investigating mechanisms to improve cognitive behavioural treatments. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2009;38(S1):8–14. doi: 10.1080/16506070902980695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel A, Beck AT. A cognitive model of suicidal behavior: Theory and treatment. Applied and Preventive Psychology. 2008;12:189–201. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JMG, Barnhofer T, Crane C, Beck AT. Problem solving deteriorates following mood challenge in formerly depressed patients with a history of suicidal ideation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:421–431. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.3.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CS, Liao SC, Lin KM, Tseng MM, Wu EC, Liu SK. Multidimensional assessments of impulsivity in subjects with history of suicidal attempts. Contemporary Psychiatry. 2009;50:315–321. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W. Making bootstrap statistical inferences: A tutorial. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport. 1997;68:44–55. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1997.10608865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]