We present addressable plasmonic metasurfaces for optical information encryption and holography.

Abstract

Metasurfaces enable manipulation of light propagation at an unprecedented level, benefitting from a number of merits unavailable to conventional optical elements, such as ultracompactness, precise phase and polarization control at deep subwavelength scale, and multifunctionalities. Recent progress in this field has witnessed a plethora of functional metasurfaces, ranging from lenses and vortex beam generation to holography. However, research endeavors have been mainly devoted to static devices, exploiting only a glimpse of opportunities that metasurfaces can offer. We demonstrate a dynamic metasurface platform, which allows independent manipulation of addressable subwavelength pixels at visible frequencies through controlled chemical reactions. In particular, we create dynamic metasurface holograms for advanced optical information processing and encryption. Plasmonic nanorods tailored to exhibit hierarchical reaction kinetics upon hydrogenation/dehydrogenation constitute addressable pixels in multiplexed metasurfaces. The helicity of light, hydrogen, oxygen, and reaction duration serve as multiple keys to encrypt the metasurfaces. One single metasurface can be deciphered into manifold messages with customized keys, featuring a compact data storage scheme as well as a high level of information security. Our work suggests a novel route to protect and transmit classified data, where highly restricted access of information is imposed.

INTRODUCTION

Metasurfaces outline a new generation of ultrathin optical elements with exceptional control over the propagation of light (1–11). In particular, metasurface holograms have attracted tremendous attention because they promise useful applications in displays, security, and data storage (12, 13). While conventional phase holography acquires phase modulation via propagation through wavelength-scale unit cells with different heights or different refractive indices, metasurface holography relies on the spatial variation of phase discontinuities induced by a single-layer array composed of subwavelength antennas (1, 3). Especially, geometric metasurface holography that shapes light wavefronts via the Pancharatnam-Berry (PB) phase can be achieved by simply controlling the in-plane orientations of antennas. This approach not only allows highly precise control of the phase profile but also alleviates the fabrication complexity. The PB phase does not depend on the specific antenna design or wavelength, rendering a broadband performance possible (12, 14).

To date, a number of metasurface holograms have been accomplished for the terahertz, infrared, and visible spectral regimes (15–17). However, most of the reconstructed holographic images have been restricted to be static because of the fixed phase and amplitude profiles possessed by the metasurfaces once fabricated (14, 18, 19). Only very recently, attempts on stretchable metasurface holograms have been made, showing image switching at different planes (20). In addition, electrically tunable metasurface holograms have been demonstrated at microwave frequencies (21). These initial endeavors elicit an inevitable transition from static to dynamic metasurface holography for advancing the field forward (22). Nevertheless, significant challenges remain for imparting complex reconfigurability at visible frequencies. The challenges include multiplexing a metasurface with addressable subwavelength pixels, endowing the pixels with different dynamic functions, independent control of the dynamic pixels at the same time, and so forth. Here, we overcome these challenges by using chemically active metasurfaces based on magnesium (Mg), which comprise dynamic plasmonic pixels enabled by the unique hydrogenation/dehydrogenation characteristics of Mg. In particular, we demonstrate a series of dynamic metasurface holograms at visible frequencies with novel functionalities including a hologram with both static and dynamic patterns, a hologram with differently sequenced dynamics, and an encrypted hologram that can be deciphered into manifold customized messages.

RESULTS

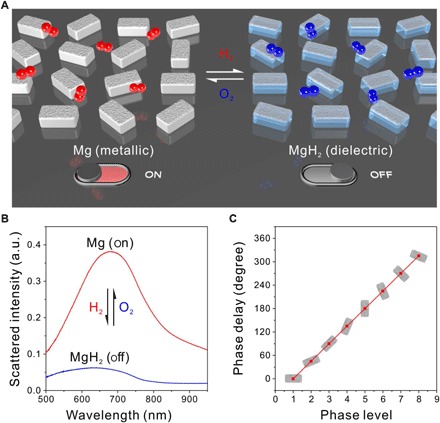

Phase transition of Mg nanorod

Mg not only has excellent plasmonic properties at visible frequencies but also can undergo a phase transition from metal to dielectric upon hydrogen loading, forming magnesium hydride (MgH2) (see Fig. 1A) (23–25). This transition is reversible through dehydrogenation using oxygen. As a result, the plasmonic response of a Mg nanorod can be reversibly switched on and off, constituting a dynamic plasmonic pixel, as shown in Fig. 1B (see also fig. S1). To facilitate hydrogenation and dehydrogenation processes, we cap a titanium (Ti; 5 nm) spacer and a palladium (Pd; 10 nm) catalytic layer on the Mg nanorods, which reside on a silicon dioxide (SiO2) film (100 nm) supported by a silicon (Si) substrate. A Ti (3 nm) adhesion layer is adopted underneath for improved Mg quality. For conciseness, Ti is omitted in all the figure illustrations. Such plasmonic pixels can be used to dynamically control the phase of circularly polarized light via the PB phase. To shape arbitrary light wavefronts, we choose eight-phase levels for the metasurfaces in this work. The nth phase pixel φn is represented by a nanorod with an orientation angle φn/2, as shown in Fig. 1C.

Fig. 1. Working principle of the dynamic metasurface pixels.

(A) Schematic of hydrogen-responsive Mg nanorods (200 nm × 80 nm × 50 nm), which are sandwiched between a Ti (5 nm)/Pd (10 nm) capping layer and a Ti (3 nm) adhesion layer. (B) Measured scattering spectra of such a nanorod in Mg (on) and MgH2 (off) states. Before hydrogenation, the Mg nanorod exhibits a strong plasmonic resonance (red curve), whereas after hydrogenation (10% H2) the MgH2 rod shows a nearly featureless spectrum (blue curve). The process is reversible through dehydrogenation using O2 (20%). a.u., arbitrary units. (C) Simulated phase delay for the different phase levels. The orientation of the nanorod at each phase level is shown.

Dynamic metasurface holograms

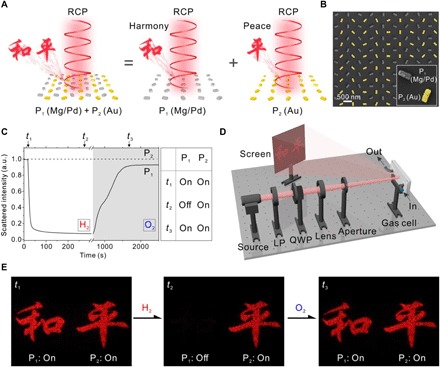

Metasurfaces multiplexed with addressable plasmonic pixels render encoding of manifold optical information with tailored dynamic possibilities. To show such unprecedented degrees of freedom, we demonstrate a series of dynamic metasurface holograms for optical information processing and encryption at visible frequencies. As the first example, the metasurface is multiplexed with two independent phase profiles containing Mg/Pd (P1) and gold (Au) (P2) nanorods as dynamic and static pixels, respectively. Two off-axis holographic images with Chinese words, “harmony” (left) and “peace” (right), are respectively encoded into each phase profile based on Gerchberg-Saxton algorithm (26), as shown in Fig. 2A. The two sets of pixels are interpolated into each other with a displacement vector of (300 nm, 300 nm), as shown by the scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image in Fig. 2B. Figure 2C illustrates the time evolutions of the scattered intensities of P1 and P2 recorded at their resonance positions during hydrogenation (10% hydrogen) and dehydrogenation (20% oxygen), respectively (see also fig. S1). Upon hydrogen exposure at t1, the scattered intensity of P1 instantly decreases and reaches the “off” state at t2, as depicted by the solid line. Upon oxygen exposure, P1 can be switched on again at t3, exhibiting slight hysteresis in the recovered scattered intensity (see Fig. 2C and fig. S2). In contrast, the scattered intensity of P2 keeps constant, as depicted by the dashed line in Fig. 2C, remaining at the “on” state during the entire process. The distinct optical responses of P1 and P2 enable dynamic and static holographic patterns that can be reconstructed from the same metasurface.

Fig. 2. Metasurface hologram with dynamic and static patterns.

(A) Two holographic patterns, harmony and peace, reconstructed from two independent phase profiles containing Mg/Pd (P1) and Au (P2) nanorods as dynamic and static pixels, respectively. Ti is omitted for conciseness. The two sets of pixels are merged together with a displacement vector of (300 nm, 300 nm). (B) Overview SEM image of the hybrid plasmonic metasurface. The Au (P2) nanorods are represented in yellow color. Inset: Enlarged SEM image of the unit cell (600 nm × 600 nm). (C) Time evolutions of P1 (solid line) and P2 (dashed line) during hydrogenation and dehydrogenation. The scattered intensities at resonance peak positions of P1 and P2 are used to track the dynamic processes, respectively. P1 can be switched off/on through hydrogenation/dehydrogenation, whereas P2 stays at the on state. (D) Schematic of the optical setup for capturing the holographic images. QWP, quarter-wave plate; LP, linear polarizer. (E) Representative snapshots of the holographic images during hydrogenation and dehydrogenation. Harmony (left) can be switched off/on using H2/O2, whereas peace (right) stays still.

The experimental setup for the hologram characterizations is presented in Fig. 2D, in which circular polarized light is generated from a laser diode source (633 nm) by a polarizer and a quarter-wave plate. The light is incident onto the metasurface sample placed in a gas cell. The reflected hologram is projected onto a screen in the far field and captured by a visible camera. Figure 2E shows the representative snapshots of the holographic images during hydrogenation and dehydrogenation. At the initial state, two high-quality holographic patterns, harmony (left) and peace (right), are observed by illumination of right circularly polarized (RCP) light onto the metasurface sample (see fig. S3A for the enlarged holographic pattern). When left circularly polarized (LCP) light is applied, the positions of the two images are swapped. Upon hydrogenation, harmony gradually diminishes, whereas peace remains unchanged. Upon dehydrogenation, harmony can be recovered so that both holographic patterns are at the on state again. A video that records the dynamic evolution of the metasurface hologram can be found in movie S1A. To demonstrate good reversibility and durability, operation of the metasurface hologram in a number of cycles is shown in movie S1B.

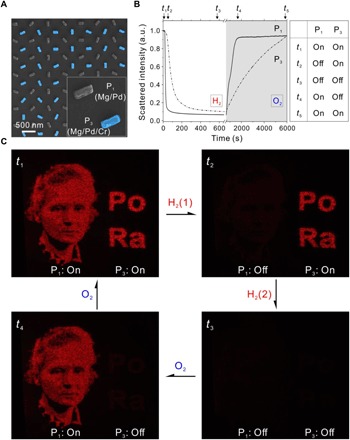

To achieve holographic patterns with sequenced dynamics, we multiplex the metasurface with dynamic pixels that have different reaction kinetics upon hydrogenation/dehydrogenation (see fig. S4A). As shown by the SEM image in Fig. 3A, each unit cell contains a Mg/Pd (P1) nanorod and a Mg/Pd/Cr (P3) nanorod as two sets of dynamic pixels. The chromium (Cr) (1 nm) capping layer can effectively slow down both the hydrogenation and dehydrogenation rates of P3. This leads to distinct time evolutions of P1 (solid line) and P3 (dash-dotted line) during hydrogenation and dehydrogenation (see Fig. 3B). Specifically, upon hydrogen exposure at t1, the scattered intensity of P1 decreases more rapidly than that of P3, quickly reaching the off state at t2, whereas P3 is only switched off after a much longer time t3, exhibiting an evident delay. During dehydrogenation, P1 can be promptly switched on at t4, whereas P3 is gradually recovered to the on state until t5. As a result, P1 and P3 can be switched on and off independently. The two holographic patterns reconstructed using RCP light, that is, the portrait of Marie Curie as well as the chemical elements polonium (Po) and radium (Ra), can transit through four distinct states, as shown in Fig. 3C (see fig. S3B for the enlarged holographic pattern). H2(1) or H2(2) refers to a hydrogenation process until the first or second feature completes transition. A video that records the dynamic evolution of the metasurface hologram can be found in movie S2.

Fig. 3. Metasurface hologram with differently sequenced dynamics.

(A) Mg/Pd (P1) and Mg/Pd/Cr (P3) nanorods work as dynamic pixels with different reaction kinetics. Overview SEM image of the hybrid plasmonic metasurface as well as the enlarged SEM image of the unit cell (600 nm × 600 nm). The Mg/Pd/Cr (P3) nanorods are represented in blue color. (B) Time evolutions of P1 (solid line) and P3 (dash-dotted line) during hydrogenation and dehydrogenation. The scattered intensities at resonance peak positions of P1 and P3 are used to track the dynamic processes, respectively. (C) Representative snapshots of the holographic images during hydrogenation and dehydrogenation. H2(1) or H2(2) refers to a hydrogenation process until the first or second feature completes transition. Both the portrait of Marie Curie and the chemical elements Po and Ra can be switched on and off independently.

Optical information processing and encryption

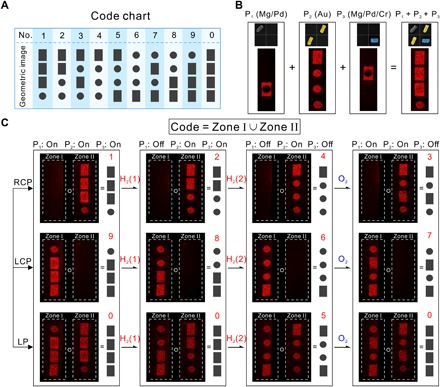

The ability to endow addressable plasmonic pixels with hierarchical dynamics in a programmable manner allows advanced optical information transmission and encryption. As a proof-of-concept experiment, a set of geometric codes has been designed and illustrated in Fig. 4A. Each Arabic number is represented by a symbol, comprising a unique sequence of dots and dashes, similar to the coding principle of Morse codes. All the numbers from 0 to 9 can be expressed by specific holographic images that are reconstructed from the same metasurface based on the mechanism as shown in Fig. 4B. Each unit cell contains three different pixels: P1 (Mg/Pd), P2 (Au), and P3 (Mg/Pd/Cr). The holographic patterns achieved by P1 and P3 are hollow dashes at two different locations, whereas the holographic pattern generated by P2 comprises one solid dash and three dots (see also fig. S4B). The shape of the dots is complementary to that of the hollow dashes so that they can fit exactly in space to form two solid dashes. It is noteworthy that the intensities of the individual holographic patterns are inversely proportional to their pattern areas. Therefore, P2 is applied twice in each unit cell for achieving a uniform intensity distribution within a merged hologram. The reconstructed holographic image of “1” is presented in Fig. 4B. The holographic images of other numbers can be generated through different routes governed by the helicity of light, the sequences of hydrogenation and dehydrogenation, and the reaction duration (see Fig. 4C). We define a coding rule that each number corresponds to a union set of the two holographic patterns in zones I and II, as shown in Fig. 4C. It is known that the sign of the acquired phase profile is flipped when the helicity of the incident light is changed (12). Therefore, two centrosymmetric holographic patterns can occur in zones I and II, respectively. When P1, P2, and P3 are all at the on state, RCP light illumination uncovers “1” in zone II, whereas LCP light illumination gives rise to its centrosymmetric image in zone I, corresponding to “9” (see Fig. 4C and fig. S5, A and B). The centrosymmetry point is indicated by a white circle in each plot, highlighting the location of the zero-order reflected light. When linearly polarized (LP) light is applied, the two holographic patterns appear simultaneously. On the basis of the coding rule, a union set of the holographic patterns in the two zones gives rise to four solid dashes, corresponding to “0” (see Fig. 4C and fig. S5C). Through sequenced hydrogenation and dehydrogenation, the geometric codes corresponding to the rest of the numbers can be achieved, as shown in Fig. 4C. A video that records the dynamic transformation among different numbers can be found in movie S3 (A and B).

Fig. 4. Metasurface-based dynamic geometric codes.

(A) Chart of the geometric codes for 0 to 9. (B) Reconstructed holographic image of 1. Each Arabic number in the chart can be expressed by a specific holographic image reconstructed from the same metasurface multiplexed by three sets of pixels: P1 (Mg/Pd), P2 (Au), and P3 (Mg/Pd/Cr). To achieve holograms with uniform intensity distributions, P2 is used twice in each unit cell. (C) Helicity of light, H2, O2, and reaction duration constitute multiple keys to generate the numbers 0 to 9, which are transformable with the same metasurface. The centrosymmetry point is indicated by a white circle in each plot, highlighting the location of the zero-order reflected light. A coding rule is defined that each number corresponds to a union set of the two holographic patterns in zones I and II.

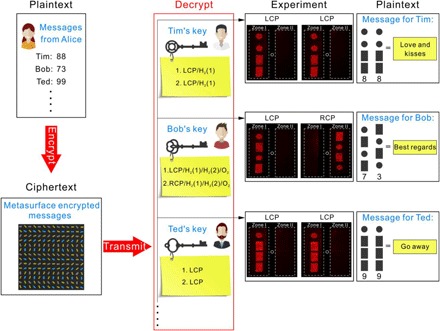

Following the Morse code abbreviations, in which different combinations of numbers represent diverse text phrases for data transmission, we demonstrate a highly secure scheme for optical information encryption and decryption using dynamic metasurfaces. As illustrated in Fig. 5, Alice would like to send different messages to multiple receivers, including Tim, Bob, Ted, and so forth. These messages are all encrypted on one metasurface. Identical samples are sent to the receivers. Upon receipt of his sample, together with the customized keys, Tim reads out the information of 88, which means “love and kisses” in Morse codes following LCP/H2(1). Bob first applies LCP/H2(1)/H2(2)/O2 to obtain “7.” After resetting the sample through sufficient dehydrogenation, he reads out “3” following RCP/H2(1)/H2(2)/O2. The decrypted message is therefore “best regards.” Similarly, other receivers can decode their respective messages using the provided keys. In other words, a single metasurface design can be deciphered into manifold holographic messages, given that the sequences of keys are customized. This elucidates an unprecedented level of data compactness and security for transmitting information, especially to a pool of multiple receivers.

Fig. 5. Proof-of-concept experiment for optical information encryption and decryption.

Alice encrypts her messages for Tim (88), Bob (73), Ted (99), and so forth, all on one metasurface. Identical samples are sent to multiple receivers, who decrypt their respective messages according to the customized keys. The keys contain customer-specific information on the helicity of light (LCP, RCP, or LP), hydrogenation (H2), dehydrogenation (O2), and reaction duration. Different messages can be read out, corresponding to love and kisses for Tim, best regards for Bob, go away for Ted, and so forth, in Morse codes.

DISCUSSION

If not only the keys but also the metasurfaces are customized, then the conveyed data quantity can be dramatically increased. In addition, dynamic pixels capped with Cr of different thicknesses in a unit cell may introduce holographic patterns with more dynamic hierarchies. Furthermore, a variety of holographic patterns, including numbers, letters, and pictures, can be combined to encrypt a significant amount of complex information with a higher security level. Therefore, our technique, which enables independent control of addressable dynamic pixels, can lead to novel data storage and optical communication systems with high spatial resolution and high data density using ultrathin devices. This will be very useful for modern cryptography and security applications. In addition, our scheme can be readily applied to achieve compact optical elements for dynamic beam steering, focusing, and shaping, as well as dynamic optical vortex generations, largely enriching the functionality breadth of current metasurface systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Structure fabrication

The samples in Fig. 2 were fabricated using multistep electron beam lithography (EBL). First, a structural layer composed of Au nanorods and alignment markers was defined in a polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) resist (Allresist) using EBL (Raith e_LiNE) on a SiO2 (100 nm)/Si substrate. A 2-nm Cr adhesion layer and a 50-nm Au film were successively deposited on the substrate through thermal evaporation followed by metal liftoff. The dimension of the Au nanorod is 200 nm × 80 nm × 50 nm. Next, the substrate was coated with a PMMA resist. Computer-controlled alignment using the Au markers was carried out to define a second structural layer. Subsequently, 3-nm Ti, 50-nm Mg, 5-nm Ti, and 10-nm Pd multilayers were deposited on the substrate through electron beam evaporation followed by metal liftoff. The samples in Figs. 3 and 4 were manufactured following similar procedures but with different metal depositions, as described in the main text.

Optical measurements

The scattering spectra of a single Mg nanorod before and after hydrogenation were measured using a microspectrometer (Acton SP-2356 Spectrograph with Pixis:256E silicon CCD camera, Princeton Instruments) through an NT&C dark-field microscopy setup (Nikon Eclipse LV100ND microscope and Energetiq Laser-Driven Light Source, EQ-99). A polarizer was used to generate LP light with polarization parallel to the long axis of the Mg nanorod for the scattering spectrum measurements. The scattering spectra were normalized with respect to that of a bare substrate. The hydrogenation and dehydrogenation experiments were carried out in a homebuilt stainless steel chamber. Ultrahigh-purity hydrogen (UHP, 5.0), oxygen (UHP, 5.0), and nitrogen (UHP, 5.0) from Westfalen were used with FSP-1246A mass flow controllers (FLUSYS GmbH) to adjust the flow rates and gas concentrations in the chamber. Here, the hydrogenation (P1 and P3) and dehydrogenation (P1) processes were carried out at room temperature. Dehydrogenation of P3 was carried out at 80°C for facilitating the process. The flow rate of hydrogen and oxygen was 2.0 liters/min.

Numerical simulations

Numerical simulations of the phase delay of the Mg nanorods were carried out using commercial software COMSOL Multiphysics based on a finite element method. Periodic boundary conditions, waveguide port boundary conditions, and perfectly matched layers were used for calculations of the structure arrays. The substrate was included in the simulations. The refractive index of SiO2 was taken as 1.5. The dielectric constants of Si and Mg were taken from Palik (27). The dielectric constants of Pd and Ti were taken from von Rottkay et al. (28).

Design of the metasurface holograms

To generate a target image, a phase-only hologram with a unit cell size of 600 nm and a periodicity of 600 μm along both directions was designed based on of Gerchberg-Saxton algorithm. The off-axis angle of the reconstructed hologram was 17°. A 2 × 2 periodic array of the holographic pattern was used to avoid the formation of laser speckles in the holographic image, according to the concept of Dammann gratings (29). Owing to the large angular range, the Rayleigh-Sommerfeld diffraction method was used to simulate the holographic image (30). The hologram was precompensated to avoid pattern distortions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the 4th Physics Institute at the University of Stuttgart for permission to use their electron gun evaporation system. We thank N. Gladen and M. Matuschek for help with material processing as well as X. Y. Duan for video programming. Funding: This project was supported by the Sofja Kovalevskaja grant from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation and the European Research Council (ERC Dynamic Nano and ERC Topological) grants. We thank the support from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/J018473/1). We acknowledge the support by the Max Planck Institute for Solid State Research for the usage of clean room facilities. Author contributions: J.L. and N.L. conceived the project. S.Z. provided crucial suggestions to the main concept of the project. J.L. performed the experiments and theoretical calculations. S.K. built the gas system and helped with the Mg material deposition. G.Z. helped with the hologram designs. F.N. made helpful comments to the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/6/eaar6768/DC1

fig. S1. Dynamic scattering spectra of a Mg nanorod during hydrogenation and dehydrogenation.

fig. S2. Time evolution of P1 during hydrogenation and dehydrogenation in multicycles.

fig. S3. High quality and high resolution of the holographic patterns.

fig. S4. Principle of the multiplexed metasurfaces.

fig. S5. Reconstructed holographic patterns in different zones upon LCP, RCP, or LP light illumination.

movie S1. Evolution of the metasurface hologram with static and dynamic patterns.

movie S2. Evolution of the metasurface hologram with sequenced dynamics.

movie S3. Dynamic transformation among different numbers.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Yu N., Genevet P., Kats M. A., Aieta F., Tetienne J.-P., Capasso F., Gaburro Z., Light propagation with phase discontinuities: Generalized laws of reflection and refraction. Science 334, 333–337 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ni X., Emani N. K., Kildishev A. V., Boltasseva A., Shalaev V. M., Broadband light bending with plasmonic nanoantennas. Science 335, 427 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang L., Chen X., Mühlenbernd H., Li G., Bai B., Tan Q., Jin G., Zentgraf T., Zhang S., Dispersionless phase discontinuities for controlling light propagation. Nano Lett. 12, 5750–5755 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aieta F., Genevet P., Yu N., Kats M. A., Gaburro Z., Capasso F., Out-of-plane reflection and refraction of light by anisotropic optical antenna metasurfaces with phase discontinuities. Nano Lett. 12, 1702–1706 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu N., Capasso F., Flat optics with designer metasurfaces. Nat. Mater. 13, 139–150 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin X., Ye Z., Rho J., Wang Y., Zhang X., Photonic spin Hall effect at metasurfaces. Science 339, 1405–1407 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shalaev M. I., Sun J., Tsukernik A., Pandey A., Nikolskiy K., Litchinitser N. M., High-efficiency all-dielectric metasurfaces for ultracompact beam manipulation in transmission mode. Nano Lett. 15, 6261–6266 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arbabi A., Horie Y., Bagheri M., Faraon A., Dielectric metasurfaces for complete control of phase and polarization with subwavelength spatial resolution and high transmission. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 937–943 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monticone F., Estakhri N. M., Alù A., Full control of nanoscale optical transmission with a composite metascreen. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 203903 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheludev N. I., Kivshar Y. S., From metamaterials to metadevices. Nat. Mater. 11, 917–924 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen X., Huang L., Mühlenbernd H., Li G., Bai B., Tan Q., Jin G., Qiu C.-W., Zhang S., Zentgraf T., Dual-polarity plasmonic metalens for visible light. Nat. Commun. 3, 1198 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wen D., Yue F., Li G., Zheng G., Chan K., Chen S., Chen M., Li K. F., Wong P. W. H., Cheah K. W., Pun E. Y. B., Zhang S., Chen X., Helicity multiplexed broadband metasurface holograms. Nat. Commun. 6, 8241 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khorasaninejad M., Ambrosio A., Kanhaiya P., Capasso F., Broadband and chiral binary dielectric meta-holograms. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501258 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng G., Mühlenbernd H., Kenney M., Li G., Zentgraf T., Zhang S., Metasurface holograms reaching 80% efficiency. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 308–312 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larouche S., Tsai Y.-J., Tyler T., Jokerst N. M., Smith D. R., Infrared metamaterial phase holograms. Nat. Mater. 11, 450–454 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grady N. K., Heyes J. E., Chowdhury D. R., Zeng Y., Reiten M. T., Azad A. K., Taylor A. J., Dalvit D. A. R., Chen H.-T., Terahertz metamaterials for linear polarization conversion and anomalous refraction. Science 340, 1304–1307 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang B., Dong F., Li Q.-T., Yang D., Sun C., Chen J., Song Z., Xu L., Chu W., Xiao Y.-F., Gong Q., Li Y., Visible-frequency dielectric metasurfaces for multiwavelength achromatic and highly dispersive holograms. Nano Lett. 16, 5235–5240 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ni X., Kildishev A. V., Shalaev V. M., Metasurface holograms for visible light. Nat. Commun. 4, 2807 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang L., Chen X., Mühlenbernd H., Zhang H., Chen S., Bai B., Tan Q., Jin G., Cheah K.-W., Qiu C.-W., Li J., Zentgraf T., Zhang S., Three-dimensional optical holography using a plasmonic metasurface. Nat. Commun. 4, 2808 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malek S. C., Ee H.-S., Agarwal R., Strain multiplexed metasurface holograms on a stretchable substrate. Nano Lett. 17, 3641–3645 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li L., Jun Cui T., Ji W., Liu S., Ding J., Wan X., Bo Li Y., Jiang M., Qiu C.-W., Zhang S., Electromagnetic reprogrammable coding-metasurface holograms. Nat. Commun. 8, 197 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheludev N. I., Obtaining optical properties on demand. Science 348, 973–974 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duan X., Kamin S., Liu N., Dynamic plasmonic colour display. Nat. Commun. 8, 14606 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duan X., Kamin S., Sterl F., Giessen H., Liu N., Hydrogen-regulated chiral nanoplasmonics. Nano Lett. 16, 1462–1466 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y., Duan X., Matuschek M., Zhou Y., Neubrech F., Duan H., Liu N., Dynamic color displays using stepwise cavity resonators. Nano Lett. 17, 5555–5560 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gerchberg R. W., Saxton W. O., A practical algorithm for the determination of phase from image and diffraction plane pictures. Optik 35, 237–246 (1972). [Google Scholar]

- 27.E. D. Palik, Handbook of Optical Constants of Solids (Academic Press, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- 28.von Rottkay K., Rubin M., Duine P. A., Refractive index changes of Pd-coated magnesium lanthanide switchable mirrors upon hydrogen insertion. J. Appl. Phys. 85, 408–413 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dammann H., Görtler K., High-efficiency in-line multiple imaging by means of multiple phase holograms. Opt. Commun. 3, 312–315 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shen F., Wang A., Fast-Fourier-transform based numerical integration method for the Rayleigh-Sommerfeld diffraction formula. Appl. Opt. 45, 1102–1110 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slaman M., Dam B., Pasturel M., Borsa D. M., Schreuders H., Rector J. H., Griessen R., Fiber optic hydrogen detectors containing Mg-based metal hydrides. Sens. Actuators B 123, 538–545 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slaman M., Dam B., Schreuders H., Griessen R., Optimization of Mg-based fiber optic hydrogen detectors by alloying the catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 33, 1084–1089 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamada Y., Miura M., Tajima K., Okada M., Yoshimura K., Influence on optical properties and switching durability by introducing Ta intermediate layer in Mg–Y switchable mirrors. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 125, 133–137 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ngene P., Westerwaal R. J., Sachdeva S., Haije W., de Smet L. C. P. M., Dam B., Polymer-induced surface modifications of Pd-based thin films leading to improved kinetics in hydrogen sensing and energy storage applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 12081–12085 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delmelle R., Ngene P., Dam B., Bleiner D., Borgschulte A., Promotion of hydrogen desorption from palladium surfaces by fluoropolymer coating. ChemCatChem 8, 1646–1650 (2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/4/6/eaar6768/DC1

fig. S1. Dynamic scattering spectra of a Mg nanorod during hydrogenation and dehydrogenation.

fig. S2. Time evolution of P1 during hydrogenation and dehydrogenation in multicycles.

fig. S3. High quality and high resolution of the holographic patterns.

fig. S4. Principle of the multiplexed metasurfaces.

fig. S5. Reconstructed holographic patterns in different zones upon LCP, RCP, or LP light illumination.

movie S1. Evolution of the metasurface hologram with static and dynamic patterns.

movie S2. Evolution of the metasurface hologram with sequenced dynamics.

movie S3. Dynamic transformation among different numbers.