Abstract

Objective

After Hurricane Sandy flooded Bellevue Hospital in New York City, its opiate maintenance patients were displaced and Bellevue’s outpatient program was temporarily merged with the program at Metropolitan Hospital for continuation of care. The merger forced Metropolitan to accommodate a program twice as large as its own and required special staff coordination and adjustments in clinical care.

Methods

Physicians, clinicians, and administrators from both institutions participated in interviews regarding the merger.

Results

Issues that emerged in the interviews fell into 4 major themes: (1) organization and meshing of professional cultures, (2) regulation, (3) communication, and (4) accommodations.

Conclusions

Despite these barriers, data collected after the merger showed high retention rates and low rates of positive urine toxicology results.

Keywords: emergency preparedness, hurricane, disaster medicine

On October 29, 2012, Hurricane Sandy made landfall in New York City, bringing severe flooding that led to the devastation of several New York City hospitals. In the 3-month period following the hurricane, Bellevue Hospital, the largest public hospital in New York City, ceased to provide health services, leaving patients to seek medical treatment elsewhere. For opiate-dependent patients on methadone or buprenorphine, this posed the threat of discontinued medication leading to opioid withdrawal or relapse to illicit opiate use. Within days of the storm, Bellevue’s patients were directed to continue treatment at Metropolitan Hospital—a sister hospital within the same public hospital system—which had been relatively spared by the storm. Metropolitan Hospital confronted the unique challenge of providing substance use disorder services to a patient population 3 times its usual volume, requiring rapid adjustments with regard to space, staff responsibilities, and regulatory procedures and oversight. Patient charts were left at Bellevue because of the storm’s damage, and neither institution knew how long Bellevue would need to run its substance services at Metropolitan. During Hurricane Sandy, lack of public transportation and outages of communication and power systems posed additional barriers for patients attempting to continue their treatment.

New York City has the highest number of illicit opioid users of any US city; recent estimates are over 92,000 opioid users, making it an important site to study the effects of disaster on addiction treatment.1 The New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services estimates that more than 75% of patients at 112 substance use disorder treatment programs in New York City experienced interruptions in treatment due to program closures during Hurricane Sandy.2 After the 9/11 attacks, many of New York City’s outpatient treatment programs had difficulty in verifying doses and take-home privileges for patients receiving methadone.3 Similarly, following Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in New Orleans, patients receiving opioid-maintenance therapy experienced problems when closure of their programs forced them to other facilities, with some receiving medication only when signs of withdrawal emerged.4 Correspondingly, increases in drug use were reported following Hurricane Katrina, especially among vulnerable populations such as low-income African Americans.5

Studies conducted in the period following Hurricane Sandy tended to focus on patient experience with opioid maintenance; for example, one study involved the analysis of patient interviews to better understand factors that result in opioid relapse following disruption of treatment services and psychological trauma,6 while another examined the adaptability of the buprenorphine treatment in a primary care setting following the hurricane by interviewing patients receiving opioid-maintenance therapies.7 In the present study, we gathered staff and provider perspectives to better understand the effects of Hurricane Sandy on the provision of substance use disorder treatment in New York City. We asked hospital and clinic administrators how they managed communications, regulations, hospital resources, patients, and staff when their patient load tripled.

As emergency conditions such as those posed by Hurricane Sandy are becoming more frequent,8 this case study presents an important opportunity for addiction treatment providers and administrators to use prior experiences to develop disaster preparedness strategies. The purpose of the present study was to elucidate how public substance use disorder services can adjust to emergency situations and provide continuity of care to vulnerable patients by understanding what problems they ran into, what barriers they encountered, what successes they had, and what would be done differently.

METHODS

The sample of participants included nurses, physicians, counselors, and administrators from Bellevue Hospital and Metropolitan Hospital who were involved in methadone or buprenorphine outpatient treatment in the period between October 2012 and April 2013. In all, 41 staff members participated in semi-structured interviews out of the approximately 48 working in the Metropolitan methadone program at the time (Table 1). All transcripts were included in the analysis. Our sample included staff who worked in the methadone program and Chemical Dependency Outpatient Program during this period of merger.

TABLE 1.

Recruitment of Staff Members Involved in Methadone or Buprenorphine Outpatient Treatment, by Title

| Title | Total Recruited |

|---|---|

| Physicians | 4 |

| Nurses | 10 |

| Social workers | 6 |

| Counselors | 11 |

| Coordinating managers | 3 |

| Counselor supervisors | 1 |

| Administrators | 4 |

| Vocational specialists | 2 |

| Total | 41 |

Participants were informed of the study by their respective program directors and were told a researcher would approach them. Verbal consent was obtained and participants were informed that their involvement was voluntary and that interviews would be de-identified. Scheduled interviews and continuous recruitment were carried out during a time span of 6 weeks, beginning 3 months after the program merger dissolved. Trained graduate-level interviewers conducted on-site semi-structured interviews lasting 30 to 60 minutes regarding the barriers and facilitators pertaining to methadone or buprenorphine following the disaster.

Interview protocol domains included obstacles encountered in providing continuity of care, resources for help, how these obstacles were dealt with, and how they could be avoided or dealt with better in the future. Interviewers transcribed responses onto electronic text documents using portable computers during the interview. Transcripts were analyzed with NVIVO 10 qualitative coding software using iterative thematic coding techniques well established in qualitative research, including continuous comparison and a pragmatic adaptation of grounded theory to develop relevant coding categories.9–12 Multiple coders were used for all transcripts to check intercoder reliability. Discrepancies between coders were resolved through team discussion and consensus.

Systematic qualitative content analysis led to identification of key barriers that are exemplified by representative quotes. A secondary analysis was performed using urine toxicology screening results from October 2012 to August 2013 to see how the adjustments made by these institutions related to relapse. Retention rates were analyzed by using these data and matching medical registration numbers.

Ethics, Consent, and Permissions

This research was conducted with oral informed consent procedures, data storage techniques designed to safeguard the confidentiality of participants’ identities, and participant protection from court subpoena of the study’s data as provided by a US Health and Human Services Certificate of Confidentiality. These measures were approved by New York University’s Human Subjects Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

At the time of Hurricane Sandy, total enrollment at Bellevue’s Opiate Treatment Program (OTP) was 370 patients, all of them on opioid-maintenance therapy; 320 (86.5%) of these patients continued treatment at Metropolitan Hospital following the hurricane. The Chemical Dependency Outpatient Program at Bellevue had a total enrollment of 127 at the time of the hurricane. This was a patient group dependent on a variety of substances. The majority had co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses, and many were receiving medication-assisted substance use disorder treatment; 111 (87.4%) of them continued treatment at Metropolitan. The OTP at Metropolitan carried 236 patients before the hurricane, and retained all of their patients in the period after the hurricane (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Methadone Program Retention Rates Before and After Hurricane Sandya

| OTP (Bellevue) | CDOP (Bellevue) | OTP (Metropolitan) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrollment at time of hurricane | 370 | 127 | 236 |

| Enrollment at Metropolitan following the hurricane | 320 | 111 | 236 |

| Retention rate | 86.5% | 87.4% | 100% |

Abbreviations: CDOP, Chemical Dependency Outpatient Program; OTP, Opiate Treatment Program.

The staff interviews brought to light the system changes that occurred in Metropolitan to accommodate Bellevue staff and patients. Four salient themes emerged from the interviews: (1) organization and meshing of professional cultures, (2) negotiating take-home doses and navigating state regulations, (3) communication among staff, and (4) accommodations (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Themes From the Hospital Staff Interviews

| Theme and Supporting Quotes |

|---|

| Organization and Meshing of Professional Cultures |

| • [In reference to therapy groups] “Our patients felt that the Bellevue patients were getting something that they weren’t getting, and I was trying to make them realize that this wasn’t the case….Some of the Bellevue clients had a chance to open up, and realized that there really was no difference.” |

| • [In reference to Bellevue staff arriving at Metropolitan] “Initially, because they didn’t have any of their resources and we had ours, there was some resentment because we had to do our work, while they had it easy while we were under duress because of them.” |

| • [In reference to Metropolitan staff hosting Bellevue staff] “They helped us get what we needed, tried to make sure everything was taken care of, and we didn’t have keys, so they were helping us out and really going above and beyond.” |

| Navigating Regulation |

| • “Our experience with [the regulatory agencies] was that they were very supportive and helpful, with respect to letting us relax certain regulations, in order to make it more effective and efficient for patients, and they really followed our lead, whatever we asked them for, they were really pretty reasonable and responsive.” |

| • “It was difficult working with Bellevue patients since we have some rules here that they don’t implement there, which makes it difficult since we have to explain to every client of Bellevue that this is what we do here. Some understood, some complained ‘Well at Bellevue, we didn’t have to do this.’” |

| • “We were able to get things like emergency accreditation for all the doctors, which included a fast track to IT stuff we needed; they had us up and running with accounts within a day.” |

| Communication |

| • “One of the hardest things was not knowing if or when we would go back, and the lack of communication from [central office] or Bellevue made it hard to keep staff morale up.” |

| • “Staff wasn’t aware that [Bellevue was] coming. That was the problem; there was no communication in the beginning, patients just showed up.” |

| • “[The biggest problem was] lack of communication in general. City agencies not communicating with each other, people at Bellevue and Metropolitan not communicating well in the beginning, because you can make a lot of things better with good communication, and really mess things up with bad communication.” |

| • “Fortunately, after everything was over and [the other programs] called us to see if we had medicated their clients, they told us the true dose, and everyone had told the truth except for one patient which was off by 10 mg.” |

| Accommodations |

| For Patients |

| • “We had our medication nurse on one side, and eventually opened up another station on the other side. The great thing about that was it allowed the Bellevue nurses to stand on one side and our nurses on the other. We managed to get the other station open, it was very helpful.” |

| • “[The doctor] helped us get coffee for our patients, asked what we needed, and these little things went a long way” |

| Psychiatric Services for Staff |

| • “What we did was start asking food service to bring up coffee and snacks. Another thing was to quickly arrange schedules of additional group counseling, and arrange space for counselors from Bellevue who were asked to come on board. Most of the other services were also asked to come here. We doubled up on counseling services.” |

Organization and Meshing of Professional Cultures

The requirement to physically relocate staff and patients from one hospital into another raised a number of issues with regard to the mixing of the norms and practices of 2 institutions. The interviews revealed that the influx of patients and the subsequent long lines were the first and largest obstacles to providing continuity of care. Longer than average wait times for medication (up to 8 hours) were reported. Similarly, our interviewees described a lack of structure, as well as a lack of space and resources, for the arrival of Bellevue’s patients and staff. With regard to staff, a Metropolitan nurse found that “Initially, because they didn’t have any of their resources and we had ours, there was some resentment because we had to do our work, they had it easy while we were under duress because of them.” A Bellevue employee acknowledged this difference and said, “They helped us get what we needed, tried to make sure everything was taken care of, and since we didn’t have keys, they were helping us out and really going above and beyond.” In addition to a lack of resources, tension arose from the mixing of the treatment practices of the 2 institutions. A Metropolitan employee noted that “It was difficult working with Bellevue patients since we have some rules here that they don’t implement there, which makes it difficult since we have to explain to every client of Bellevue that this is what we do here. Some understood, some complained ‘Well at Bellevue, we didn’t have to do this.’” In order to minimize disturbances and reduce wait times, providers scheduled Metropolitan and Bellevue patients on alternate days of the week. Additionally, special permission was obtained from the New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse to dispense additional doses during this time so that patients would not need to attend the clinic as frequently.

The Metropolitan Hospital administration cited the most effective intervention as keeping groups of patients and staff together. Bellevue counselors were kept with their patients, nurses continued to work shifts with their original teams, and staff were spatially clustered so as to provide familiarity to staff members and patients. Administrators saw this as an essential adjustment because it provided a sense of stability to patients who reported feeling traumatized and isolated after the hurricane.

Interviewees noted the importance of group counseling after a disaster, particularly when a lack of space precluded regularly scheduled individualized counseling. Group sessions eased tensions between clients of the 2 programs by bringing them together and providing a safe space for clients to share their grievances. In reference to the therapy sessions, one counselor said, “Our patients felt that the Bellevue patients were getting something that they weren’t getting, and I was trying to make them realize that this wasn’t the case….Some of the Bellevue clients had a chance to open up, and realized that there really was no difference.” Metropolitan was able to continue providing regularly scheduled group sessions; however, there was a 2-week delay in getting group therapy started by the Bellevue staff.

Owing to limitations in office space, staff shared office space, with an average of 3 people sharing an office that ordinarily served 1 staff member. Despite the benefits of group therapy sessions, interviewees noted that the biggest obstacle presented by the lack of space was the inability to carry out individualized counseling sessions when needed.

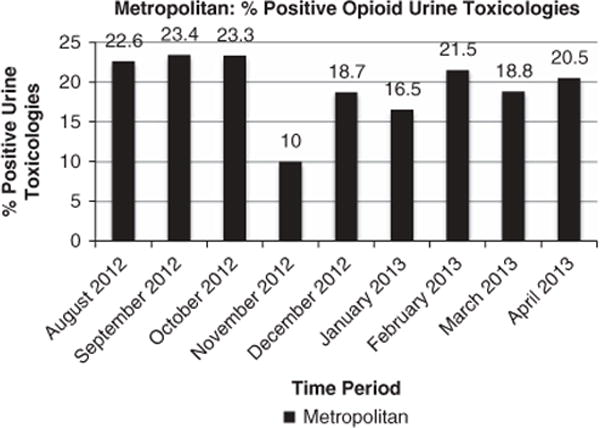

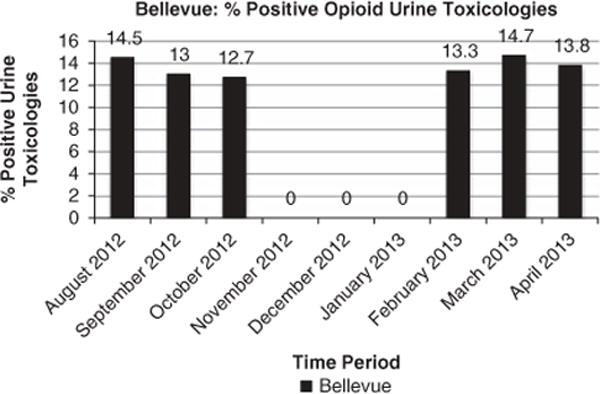

Staff cited attempts to reduce long wait times, lack of available staff, and the adjustment to a new facility as barriers to collecting urine samples for toxicology screenings. The Metropolitan administration indicated no change in the number of positive screening results on urine toxicology samples. However, Bellevue staff noted that upon returning to Bellevue, there was a perceived increase in the number of positive screening results on urine toxicology samples. Data collected from both hospitals indicated that there was in fact no significant change in the number of opioid-positive results from urine samples (Figure 1 and Figure 2). It was also noted that because patients grew accustomed to the privileges of receiving more take-home doses (doses that are dispensed in advance for patients to take at home so that they would not need to “check-in” at the clinic as frequently), some patients maintained a high level of compliance to keep the privileges, whereas others became agitated and less compliant. Of note is that urine drug screening was not performed on Bellevue patients in the month-long period immediately following the hurricane, whereas Metropolitan continued its urine drug screens without interruption. Urine drug screens were temporarily discontinued for Bellevue patients because of the extra time it would add for patients waiting in an already long line and the diversion of resources toward medication dispensation.

FIGURE 1.

Urine Toxicology Data From the Metropolitan Hospital Outpatient Addiction and Opioid Program.

FIGURE 2.

Urine Toxicology Data From the Bellevue Hospital Outpatient Addiction and Opioid Program.*

*Staff were unable to conduct urine testing for Bellevue patients in the 3 months after Hurricane Sandy owing to limited resources.

The Chemical Dependency Outpatient Program, a distinct entity from the methadone program at Bellevue that also deals with substance use issues, transitioned to Metropolitan with significantly fewer reported obstacles. There were no reports of problems with buprenorphine medication supply, patients did not have trouble filling prescriptions, and there were no barriers to identity verification. Staff noted that dose verification for buprenorphine presented a minimal obstacle because most patients came with bottles that verified their dose.

Regulations

Given that state authorities and the Drug Enforcement Agency tightly regulate methadone and buprenorphine-maintenance therapies, issues arose with regard to ensuring that the stringent regulatory requirements were being met and addressed in an appropriate and acceptable way. Regulatory agencies became more lenient during this period, which interviewees reported to have eased the stress of staff. A Metropolitan administrator noted that her “experience with [the regulatory agencies] was that they were very supportive and helpful, with respect to letting us relax certain regulations in order to make it more effective and efficient for patients. They really followed our lead, whatever we asked them for, they were really pretty reasonable and responsive.” This allowed Metropolitan to increase take-home dosing and to use the “honor system” in light of the difficulty in dose verification, which meant that doses were dispensed on the basis of patient self-report. Metropolitan administration also received approval from the city regulatory agencies to provide extended take-home doses to all patients, including those who had not been in the program for the time required to receive privileges. Program directors from both hospitals indicated that they were not allowed to admit new patients, which made providing continuity of care significantly easier. Regulatory changes that facilitated the transition of physicians from Bellevue to Metropolitan were key. One administrator noted, “We were able to get things like emergency accreditation for all doctors, which included a fast track to IT stuff we needed; they had us up and running with accounts within a day.”

On the other hand, staff commented that their communication with regulatory agencies was slow and irregular, which complicated their planning. An employee said that “one of the hardest things was not knowing if or when we would go back, and the lack of communication from [central office] or Bellevue made it hard to keep staff morale up.” Another administrator found that “[The biggest problem was] lack of communication in general. City agencies not communicating with each other, people at Bellevue and Metropolitan not communicating well in the beginning—you can make a lot of things better with good communication, and really mess things up with bad communication.” In addition to these logistical communications, HIPAA laws that prevented the sister hospitals from sharing electronic medical records and the inability of Metropolitan’s pharmacy to fill prescriptions written at Bellevue posed limitations.

The largest staff concern was whether protocol changes such as increased take-home dosing and decreased urine toxicology testing would result in a greater rate of relapse. Participants also noted that navigating newly imposed hospital guidelines were a barrier to treating patients efficiently. For example, while staff from both institutions preferred liquid methadone over tablet methadone, owing to the available dispensing equipment, administrators required that tablets be used instead. This led to time-consuming pill counting, the need for additional staff for dosing, and complaints from patients unfamiliar with the tablet form of methadone. Regarding the “honor system” of providing extra take-home doses for patients, one nurse found that “fortunately, after everything was over and [the other programs] called us to see if we had medicated their clients, they told us the true dose, and everyone had told the truth except for one patient which was off by 10 mg.”

Communication

Following the hurricane, downed phone lines and a lack of cellular phone signals made communication problematic between both the hospitals and regulatory agencies as well as between patients and their providers. In the interviews, communication also emerged as an important aspect of continuity of care. Downed phone lines, for example, made communication between patients and staff difficult. Similarly, updates were not available regarding when Bellevue staff and patients would be able to return to Bellevue. The interviews highlighted the importance of maintaining up-to-date contact information for patients and delivering a consistent message to patients on where to go, as patients received conflicting information. Other suggestions were a system for triaging phone calls and a central phone line in an emergency.

A psychologist was brought in to help ease the frustration of staff 2.5 months after Bellevue staff had moved to Metropolitan. Staff felt that this would have been more valuable had the psychologist been brought in shortly after Bellevue staff began to work at Metropolitan, as many tensions resolved themselves over time. Tensions included resentment of Metropolitan staff toward Bellevue for having less work to do initially, giving up office space for Bellevue, and a belief that patients from one program were “more difficult” than patients from the other. Staff believed that had these tensions been resolved sooner, better care could have been provided. For example, better communication between the 2 entities when dispensing medication may have led to shorter wait times.

Accommodations

Our interviews revealed that accommodations, particularly those provided by hospital administration for staff and patients, were beneficial for easing tensions while the merger continued. In response to this, the hospital opened a second medication window, which both reduced wait time and allowed the Metropolitan nurses and Bellevue nurses to each work at one window. One nurse stated, “the great thing about [the second window opening] was it allowed the Bellevue nurses to stand on one side and our nurses on the other. Once we managed to get the other station open, it was very helpful.”

Due to the uncertainty of medication time and the threat of opioid withdrawal, interviewees reported that patients frequently became agitated. Counselors from both institutions were assigned to monitor the line and maintain order, promote understanding of the situation, and make crisis calls when necessary. Hospital police provided assistance, and there were no reports of substantial altercations. Additionally, there were no reported instances of patients entering opioid withdrawal while waiting in line. A numbering system was implemented for those in line, which allowed disabled and elderly patients to sit in a room with their numbers instead of standing in line. A Bellevue employee noted the importance of maintaining morale through small gestures, and said that Metropolitan administration “helped us get coffee for our patients, asked what we needed, and these little things went a long way.”

The staff was offered therapy groups providing counseling regarding post-traumatic stress disorder for their experiences during Hurricane Sandy.

When asked how patients could be better accommodated in the future, interviewees emphasized the importance of patients having the doctors’ private numbers when phone lines in the clinic were unavailable. Interviewees also noted that a list of alternate clinic locations and contact information for those clinics and providers would be helpful.

DISCUSSION

Despite the difficulties encountered by the staff members and administrators in this study, they achieved remarkable clinical results in the face of unprecedented emergency conditions. Their patient retention rate compares favorably with those of opioid-maintenance and outpatient substance use disorder programs operating under ordinary circumstances, and the patients’ urine toxicology results indicated low rates of relapse during clinic relocation. One unexpected finding was the apparent reduction in positive urine toxicology findings in the 3 months after the disaster during the clinic merger. Although it is beyond the scope of this study to examine the mechanism for this reduction, one possibility is that the patients who relapsed during this process were those who were not retained in treatment after the hurricane. Another possibility is that because less urine testing was done during the 3 months after the disaster, particularly on Bellevue patients, fewer patient relapses were detected. It is worth noting that the reduction in positive urine toxicology results could in fact be a true effect from effective adjustments by the programs in the form of increased take-home doses or could be a result of the drop in the street supply of substances following the hurricane. The reports by Bellevue staff of a rise in positive urine toxicology results after their patients’ return to Bellevue in the fourth month after the hurricane, when standard testing intervals were reinstated, may support the latter explanation.

The decisions that were made in reconstructing Bellevue Hospital’s substance use disorder programs in Metropolitan Hospital following Hurricane Sandy provide insight into offering continuity of care following an unprecedented disruption of service. Clear communication between hospital administration and staff allowed regulations to be appropriately modified, reorganization of hospital services while maintaining provider continuity with their respective patients helped to ease tensions, and not taking new patients helped to facilitate care for current patients. This attentiveness allowed providers and patients to feel as though the discomfort was being acknowledged and responded to in the best way that could be managed at the time. Problems that arose following the 9/11 attacks and Hurricane Katrina were again noted following Hurricane Sandy with regard to verification of dose and patient privileges, and our data further support a push toward the creation of a central registry. Staff accommodations were cited as critical for easing the frustrations caused by the merger.

One of the limitations of this study was that patient perspectives were left out of the study and may have added to the picture of the merger. However, the authors felt that because other studies have examined patient perspectives after the hurricane, a report that focused on provider perspectives would contribute a unique angle to the overall literature and allow a more comprehensive view of the effects of Hurricane Sandy on opioid treatment programs. Other studies have examined patient perspectives after the hurricane with respect to coping with a lack of substance use disorder services and found that users of heroin shared with each other to prevent friends from getting “sick,” a substantial increase in the price of heroin, increased use of dirty needles as a result of needle exchanges closing, and overall difficulty in getting around the city to their methadone programs.13 With respect to the perceived differential treatment of patients from the 2 substance use disorder programs in the present study, the consensus from staff was that this was due to Metropolitan staff being able to dose and provide counseling more efficiently given that patient charts were readily available.

Additionally, other limitations included that not all staff members involved in the merger were interviewed. Data were collected from staff 2 months after Bellevue returned to their home institution, which may have led to recall bias, leaving some issues and solutions undocumented.

CONCLUSION

The analysis provided a number of measures for institutions to consider for disaster preparation and service planning. These include (1) clear communication between the state and hospital administration, (2) attention to seemingly small details (line management, complimentary food and beverages), (3) keeping staff with original patients, (4) provision of prompt mental health services for staff, (5) use of electronic medical records in allowing for continuity of care, and (6) creation of a central registry for dose verification. The case described here underscores that continuity of care and quality of care for patients with substance use disorders can be maintained in the face of a major disaster with careful planning and responsiveness to organizational and staff needs.

Acknowledgments

Support for this work was provided by National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, DA 032674032674 (Dr. Helena Hansen).

References

- 1.McNeely J, Gourevitch MN, Paone D, et al. Estimating the prevalence of illicit opioid use in New York City using multiple data sources. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:443. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-443.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gonzalez-Sanchez A. Hurricane Sandy: The impact, lessons learned for New York State. OASAS. New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services; http://dev.nasmhpd.seiservices.com/sites/default/files/Arlene%20Gonzalez-Sanchez_Monday(1).pdf. Accessed February 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank B, Dewart T, Schmeidler J, Demirjian A. The Impact of 9/11 on New York City’s Substance Abuse Treatment Programs: A Study of Patients and Administrators. New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services; http://cretscmhd.psych.ucla.edu/nola/Video/MHR/CSAT/lessons/TheImpactOf911OnNYCsSaTreatment.pdf. Published October 2003, Accessed February 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maxwell JC, Podus D, Walsh D. Lessons learned from the deadly sisters: drug and alcohol treatment disruption, and consequences from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. Subst Use Misuse. 2009;44(12):1681–1694. doi: 10.3109/10826080902962011.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cepeda A, Valdez A, Kaplan C, et al. Patterns of substance use among Hurricane Katrina evacuees in Houston, Texas. Disasters. 2010;34(2):426–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2009.01136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams AR, Tofighi B, Rotrosen J, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity, red flag behaviors, and associated outcomes among office-based buprenorphine patients following Hurricane Sandy. J Urban Health. 2014;91(2):366–375. doi: 10.1007/s11524-014-9866-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tofighi B, Grossman E, Williams AR, et al. Outcomes among buprenorphine-naloxone primary care patients after Hurricane Sandy. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2014;9:3. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-9-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lane K, Charles-Guzman K, Wheeler K, et al. Health effects of coastal storms and flooding in urban areas: a review and vulnerability assessment. J Environ Public Health. 2013;2013:1–13. doi: 10.1155/2013/913064. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2013/913064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emerson R, Fretz R, Shaw L. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes. 2nd. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corbin J, Strauss A. Grounded Theory in Practice. New York: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lingard L, Albert M, Levinson W. Grounded theory, mixed methods and action research. BMJ. 2008;337:a567. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39602.690162.47. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39602.690162.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reeves S, Kuper A, Hodges BD. Qualitative research methodologies: ethnography. BMJ. 2008;337:a1020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1020. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pouget ER. Immediate impact of Hurricane Sandy on people who inject drugs in New York City. Subst Use Misuse. 2015;50(7):878–884. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2015.978675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]