Abstract

BACKGROUND & AIMS

The endoscopic reference score (EREFS) is used to determine severity of 5 endoscopic findings: edema, rings, exudates, furrows, and strictures. Little is known about the relationship between EREFSs and histologic markers of disease activity in children with eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). We aimed to determine whether the EREFS can be used to identify children with EoE and how it changes with treatment.

METHODS

We performed a prospective study of consecutive children (ages 2–17 years) undergoing diagnostic or post-treatment endoscopy scored real-time with EREFS from December 2012 through 2016. Findings from 192 diagnostic endoscopies and 229 post-treatment endoscopies were evaluated, from 371 children. Incident EoE cases were diagnosed based on 2011 consensus guidelines. Patients were treated with either elimination diet or topical steroids. Subjects who underwent endoscopy for symptoms of esophageal dysfunction but had normal esophageal findings from histology analysis were used as controls. EREFS and receiver operating characteristic curves were determined for incident EoE cases (n = 77) vs controls (n = 115), patients with active EoE (n = 101) vs inactive EoE after treatment (n = 128), and paired pre- and post-treatment cases of EoE (n = 85). Component and composite scores were correlated with eosinophilia.

RESULTS

Visual detection of more than 1 esophageal abnormality during the diagnostic endoscopy identified children with EoE with 89.6% sensitivity and 87.9% specificity. EREFS correlated with peak level of eosinophilia (P < .001) at all esophageal levels. Children who responded to therapy had mean EREFSs of 0.5 compared to 2.4 in non-responders. In comparing pre-treatment vs post-treatment data from 85 patients, we found a significant reduction in the composite EREFS (from 2.4 to 0.7) (P < .001) among patients who responded to treatment; 92% of responders had a reduced EREFSs after treatment. EREFSs identified children with EoE with an area under the curve value (AUC) of 0.93. EREFSs identified children with active EoE following treatment with an AUC of 0.81 before treatment and an AUC of 0.79 after treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

In a prospective study of children undergoing diagnostic or post-treatment endoscopy, we found the EREFS to accurately identify those with EoE. Children who responded to therapy had lower EREFS scores than non-responders. EREFSs can be used to measure outcomes of pediatric patients, in conjunction with histology findings, and assess treatments for children with EoE.

Keywords: Esophagus, Inflammation, Biomarker, Metric

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic immune disease characterized by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and eosinophil-predominant esophageal inflammation. Consensus guidelines for diagnosis of EoE in children recommend 6–8 weeks of high-dose proton pump inhibitor followed by esophagogastroduo-denoscopy (EGD) with biopsy demonstrating at least 15 eosinophils per high powered field (eos/hpf).1 Additionally, EGD is necessary for surveillance and to assess disease activity following treatment.1

In 2013 Hirano et al2 proposed the endoscopic reference score (EREFS) classification system as a way for standardization and reporting the endoscopic signs of EoE in adults. This classification has demonstrated good interobserver and intraobserver concurrence.2,3 Since then several studies in adults have demonstrated that this metric is highly predictive of EoE diagnosis and responsive to treatment.4–7

Multiple case reports and retrospective studies in children have reported findings of edema, furrows, white plaques, rings, and stricture during endoscopy. However, rings and stricture are less prevalent in children than adults.8–11 Although these individual findings have been described in children, the standardized EREFS classification has not been applied and its utility for diagnosis and response to treatment as an outcome measure has not been studied.

The aims of this study were (1) to determine the diagnostic utility of EREFS in diagnosing EoE in children, (2) determine the diagnostic utility of EREFS in assessing post-treatment disease activity in children previously diagnosed with EoE, (3) assess the longitudinal changes with therapy, (4) assess chronic endoscopic remodeling in EoE, and (5) determine the best scoring approach to use EREFS as an outcome metric.

Methods

Study Design

We performed an analysis of a prospective longitudinal cohort of children, ages 2–17 years, undergoing endoscopy with biopsy at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago between December 2012 and December 2016. Only endoscopies performed by two authors (A.F.K. and J.B.W.) were included in our analysis. This study was approved by the Lurie Children’s Hospital Institutional Review Board. A waiver of consent to consecutively register children undergoing either diagnostic or follow-up EGD in those previously diagnosed with EoE was obtained for this study.

Case Definitions

Incident EoE cases were diagnosed as per 2011 consensus guidelines: 1 or more symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and demonstration of at least 15 eos/hpf on esophageal biopsy after 8 weeks of high-dose twice-daily proton pump inhibitor therapy. Patients with connective tissue disorder, prior esophageal surgery, or varices were excluded. Inactive disease was defined as peak eosinophil count <15 eos/hpf. Subjects who underwent endoscopy because of symptoms of esophageal dysfunction with normal esophageal histology were classified as control subjects. Subjects with proton pump inhibitor–responsive esophageal eosinophilia, connective tissue disorder, inflammatory bowel disease, inlet patch, prior esophageal surgery, and those with concurrent eosinophilic gastroenteritis and eosinophilic colitis were excluded.

Clinical and Histologic Data

Endoscopic findings were incorporated into a standardized operative/procedure note using the EREFS classification system for endoscopies performed by A.F.K. and J.B.W. Both endoscopists used a visual, descriptive EREFS atlas in the endoscopy suite for accurately grading the severity of the individual findings to maintain standardized reporting. The EREFS classification system rates the severity of edema (0–2), rings (0–3), exudates (0–2), furrows (0–2), and strictures (0–1) and was graded separately for each third of the esophagus. This atlas, the basis for his initial study describing EREFS, was provided by Dr. Hirano.2 The scores were recorded in the procedure suite at the time of endoscopy, and endoscopists were blinded to prior findings; however, they were aware of clinical data and indication for endoscopy. Clinical data, such as demographics, concomitant atopic history, and medical history, and pathologic data were collected by chart review of the electronic medical record to a deidentified database. The presence of IgE-mediated food allergy was assessed by chart review. At least 3 biopsies each from distal, mid, and proximal esophagus were obtained for the study during the endoscopy that was performed under general anesthesia. Peak eosinophil counts were used for the purpose of this study and were obtained from the pathologist report.

Patient Cohorts

Three patient cohorts were derived for this study. A diagnostic cohort consisted of patients undergoing endoscopy for suspected EoE, and included incident subjects with EoE and control subjects. The second post-treatment cohort consisted of active and inactive EoE patients who were treated with either elimination diet or topical steroids. The third group was comprised of a longitudinal cohort of paired pretreatment and post-treatment EGD. Patients in the longitudinal cohort were treated with either diet elimination or swallowed steroids.

Statistical Analysis

Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney (2 groups) or Kruskal-Wallis rank sign tests with Dunn post hoc testing (3 groups) were used to compare eos/hpf and EREFS scores. Spearman coefficients were determined for the correlation between EREFS scores and peak eos/hpf. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated from the combined scores in each cohort. Linear regression was used to determine the relationship between the change in eos/hpf and the change in inflammatory EREFS scores. GraphPad Prism version 6.0 (La Jolla, CA) and SPSS version 22.0 (Armonk, NY) were used for statistical calculations.

Results

Clinical Characteristics of Diagnostic and Post-treatment Cohorts

There were 192 subjects in the diagnostic cohort. There were no significant differences in age, ethnicity, asthma, or eczema between EoE and control patients shown in Table 1. A significant increase was identified in the EoE population for male gender (75% vs 47%), IgE-mediated food allergy (43% vs 16%), and allergic rhinitis (74% vs 49%; P < .05). Most EoE patients had at least 1 abnormal visual finding (90%), compared with only 14% of control patients. All visual findings were significantly different between EoE and control patients. The average peak eos/hpf were 2 in control subjects and 60 in EoE patients (P < .001). Rings were present in one-third of the EoE patients and there were no strictures in any of the cohorts. Of the 77 EoE patients in the diagnostic cohort, 6 (7.7%) had upper gastrointestinal studies and 14 (18%) had an esophagram, neither of which identified any abnormalities.

Table 1.

Clinical and Endoscopic Characteristics of the Diagnostic Cohort

| Diagnostic (n = 192) | Control (n = 115) | EoE (n = 77) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics, n (%) | |||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 10.36 ± 4.27 | 10.1 ± 5.2 | .753 |

| Male | 54 (47) | 58 (75.3) | <.001 |

| White | 106 (92.2) | 66 (85.7) | .151 |

| Hispanic | 12 (10.4) | 6 (7.8) | .538 |

| Atopic disorders | 68 (59.1) | 67 (87) | <.001 |

| Asthma | 28 (25) | 26 (33.8) | .190 |

| Eczema | 21 (20) | 27 (35.5) | .20 |

| IgE-mediated food allergy | 18 (16.2) | 17 (43.4) | <.001 |

| Allergic rhinitis | 54 (49.1) | 56 (73.7) | .001 |

| Visual findings, n (%) | |||

| Abnormal finding | 14 (12.2) | 69 (89.6) | <.001 |

| Edema | 8 (7) | 62 (80.5) | <.001 |

| Exudate | 2 (1.7) | 42 (54.5) | <.001 |

| Furrows | 8 (7.0) | 65 (84.4) | <.001 |

| Rings | 5 (4.3) | 23 (29.9) | <.001 |

| Stricture | 0 | 0 | NA |

NOTE. Proportions are compared with chi-square test, means are compared with unpaired 2-sample Student t test.

EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; NA, ■■■; SD, standard deviation.

Clinical characteristics of 229 EoE patients in the post-treatment cohort are shown in Table 2. Patients were separated into active (≥15 eos/hpf) and inactive EoE (<15 eos/hpf) groups. There were no differences in age, gender, ethnicity, and atopic disorders, except patients with active disease had a higher likelihood of IgE-mediated food allergy (56% vs 31%; P < .001). Significantly more patients with active EoE continued to have edema (72%), exudates (50%), and furrows (69%) compared with those with inactive EoE (P < .001), although there was no difference in rings. The average peak eos/hpf for proximal, mid, and distal esophagus in the active EoE group were 23, 35, and 45 compared with 0.8, 1.4, and 2.7 eos/hpf, respectively, in the in inactive EoE group (P < .001).

Table 2.

Clinical and Endoscopic Characteristic of Post-treatment CohortPost-treatment (n = 229)

| Active EoE (n = 101) | Inactive EoE (n = 128) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics, n (%) | |||

| Age (mean ± SD) | 9.76 ± 4.59 | 10.1 ± 4.94 | .586 |

| Male | 80 (79.2) | 90 (70.3) | .126 |

| White | 91 (90.1) | 111 (86.7) | .620 |

| Hispanic | 15 (14.9) | 11 (8.6) | .138 |

| Atopic disorders | 86 (85.1) | 106 (82.8) | .633 |

| Asthma | 37 (36.6) | 47 (36.7) | .989 |

| Eczema | 46 (45.5) | 49 (38.3) | .268 |

| IgE-mediated food allergy | 57 (56.4) | 40 (31.3) | <.001 |

| Allergic rhinitis Treatment | 57 (56.4) | 73 (57.0) | .928 |

| Swallowed steroids | 39 (38.6) | 57 (44.5) | .368 |

| Visual findings, n (%) | |||

| Abnormal finding | 86 (85.1) | 63 (49.2) | <.001 |

| Edema | 73 (72.3) | 25 (19.5) | <.001 |

| Exudate | 50 (49.5) | 9 (7.0) | <.001 |

| Furrows | 70 (69.3) | 27 (21.1) | <.001 |

| Rings | 31 (30.7) | 39 (30.5) | .971 |

| Stricture | 0 | 0 | NA |

NOTE. Proportions are compared with chi-square test, means are compared with unpaired 2-sample Student t test.

EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; NA, ■■■; SD, standard deviation.

There were 85 patients in a longitudinal subgroup divided into treatment responders (n = 53) and non-responders (n = 32). There were no differences in baseline characteristics (demographics, atopy, visual findings) or treatment type (steroids vs elimination diet) between responders and nonresponders (Supplementary Table 1).

Utility and Association With Histology of Individual Endoscopic Reference Score Components

We next determined the utility of individual findings to identify active EoE in the diagnostic and post-treatment cohorts. Edema, exudate, and furrows had a high sensitivity (89%, 96%, 89%), specificity (88%, 76%, 90%), diagnostic odds ratio (55.3, 67.8, 72.4), and accuracy (88.0, 80.7, 89.6) for identifying active EoE in the diagnostic cohort; however, the sensitivity, specificity, diagnostic odds ratio, and accuracy was lower in the post-treatment cohort shown in Table 3. The correlation between EREFS scores for individual findings and peak eos/hpf in the proximal, mid, and distal esophagus in diagnostic and post treatment endoscopies is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. A significant difference in eosinophilia was found between the absence of each finding (score of 0) and a severity score of 1 or 2 (P < .05). However, between scores of 1 and 2, only edema in the proximal esophagus (diagnostic group) and furrows in the mid/distal (post-treatment group) demonstrated significant differences in eosinophilia (Supplementary Table 2). Additionally, no significant differences in eosinophilia were seen in those with post-treatment rings, consistent with the observation that rings identify fibrostenotic tissue remodeling.

Table 3.

Sensitivity, Specificity, Odds Ratio, and Accuracy Calculations of Visual Findings in the Diagnostic and Post-treatment Cohorts to Detect Active EoE (eos/hpf≥15)

| Sensitivity (%)

|

Specificity (%)

|

Odds ratio

|

Accuracy

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dx | Post-Tx | Dx | Post-Tx | Dx | Post-Tx | Dx | Post-Tx | |

| ≥1 abnormality | 89.6 | 85.2 | 87.9 | 50.8 | 62.2 | 5.92 | 88.5 | 65.9 |

| Edema | 88.6 | 72.3 | 87.7 | 80.5 | 55.3 | 10.74 | 88.0 | 76.9 |

| Exudate | 95.5 | 49.5 | 76.3 | 93.0 | 67.8 | 12.96 | 80.7 | 73.8 |

| Furrows | 89 | 69.3 | 89.9 | 78.9 | 72.4 | 8.45 | 89.6 | 74.7 |

| Rings | 79.3 | 30.7 | 66.9 | 69.5 | 7.7 | 1.01 | 68.8 | 52.4 |

EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; eos/hpf, eosinophils per high powered field.

Composite Scores Have Utility in Diagnosis and Treatment Assessment

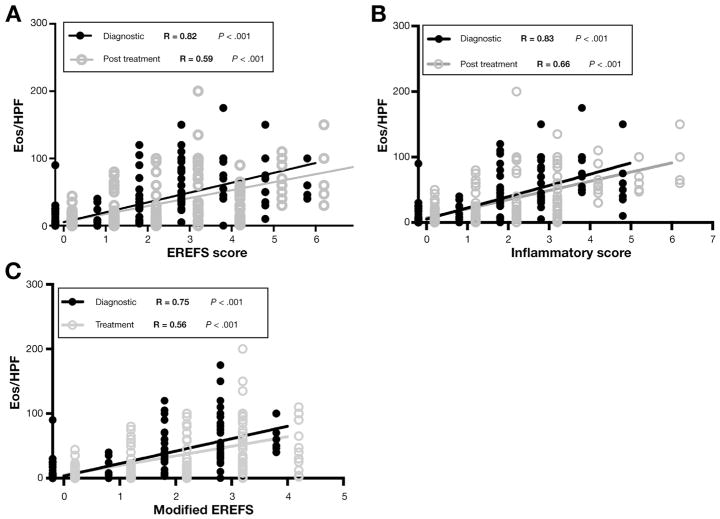

Because the individual EREFS scores demonstrated variable utility and poor correlation with the degree of eosinophilia, we further investigated whether composite EREFS scores would be a more reliable predictor of active EoE. Three composite scores were generated similar to what has previously been described in adults: (1) a composite EREFS score made up of the sum of the maximal overall score for each individual sign; (2) an inflammatory EREFS score, derived by adding the 3 inflammatory signs (edema, exudate, furrows), but excluded rings and stricture; and (3) a modified EREFS score that only added up presence (1) vs absence (0) of all visual findings similar to what was first proposed by Hirano et al2 in 2014 in adults. All scores correlated significantly with peak eos/hpf shown in Figure 1, with the inflammatory score having the superior correlation within both the diagnostic cohort and post-treatment cohort (R = 0.83 vs 0.82, 0.75; and R = 0.66 vs 0.59, 0.56). Similar correlations were found for the 3 sites (proximal, mid, distal) within the esophagus shown in Supplementary Figure 2. Although scores of 1 versus 2 did not clearly identify differences in eos/hpf, we found a strong correlation between composite scores and eosinophilia in the diagnostic and post-treatment cohorts.

Figure 1.

Correlation of EREFS score (A), inflammatory score (B), and modified ERFES (C) with eos/hpf for diagnostic and post-treatment cohorts. Comparison made by Spearman rank-order correlation.

Utility of Scores to Identify Diagnosis and Disease Activity

Because the composite scores correlated highly with eosinophilia, we next determined whether the EREFS inflammatory score could distinguish EoE patients from control subjects in the diagnostic cohort and active from inactive EoE in the post-treatment group. Mean EREFS inflammatory score in the diagnostic group was 2.6 in EoE patients and 0.2 in control subjects (P < .001). In post-treatment EoE patients, the EREFS inflammatory score was 2.4 in active EoE and 0.5 in inactive EoE (P < .001). This is shown in Figure 2A and B. Receiver operating characteristics for the inflammatory score had a similarly high area under the curve of 0.93 for EoE diagnosis and 0.81 for post-treatment active disease (Figure 2C and D). Taken together, our data suggests the EREFS inflammatory score is highly correlative with eosinophilia and effectively identifies EoE from control, and active from inactive disease.

Figure 2.

EREFS inflammatory score in diagnostic and post-treatment cohorts. Comparison of EREFS inflammatory score in diagnostic (A) and post-treatment (B) cohorts. Significance determined by unpaired nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. ROC curves for EREFS inflammatory score for (C) EoE versus control and (D) active versus inactive EoE. AUC, area under the curve.

Longitudinal Changes in Endoscopic Reference Score With Treatment

We next determined whether the change (Δ, delta) in the EREFS inflammatory score before to after therapy associated with and predicted treatment response. In the longitudinal group, we determined the Δ EREFS inflammatory score between the baseline (pretreatment) and post-treatment EREFS scores (Figure 3). The Δ inflammatory score in responders was 2.4 compared with 0.7 in nonresponders (Figure 3A; P < .001). This difference had a strong area under the curve of 0.79 (Figure 3B), with excellent specificity for values >2 to identify treatment responders. By linear regression, the change in EREFS inflammatory score significantly predicted the change in esophageal eosinophilia (R2 = 0.22; P < .001), independent of age (Figure 3C). This suggests the change in EREFS inflammatory score has utility in identifying the response to therapy.

Figure 3.

Inflammatory score changes before and after therapy correlate with changes in eosinophilia and treatment response. (A) Comparison of the change in inflammatory score (Δ inflammatory score) pretreatment and post-treatment between responders and nonresponders. Responders were identified as having a post-treatment endoscopy with <15 eos/hpf. Significance determined by unpaired nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. (B) Receiver operating characteristics for Δ inflammatory score to identify treatment responder status. (C) Linear regression of Δ inflammatory score and change in peak eos/hpf (Δ eos/hpf) for treatment responders and nonresponders. Controls for age. (D) Change in EREFS score (Δ EREFS) between pre-treatment and post-treatment endoscopies for individual visual findings within responders and nonresponders. AUC, area under the curve.

To understand specific endoscopic changes in responders versus nonresponders, we examined the change in individual EREFS scores by responder status. We found a significant difference in edema, exudate, and furrows, with no difference in rings (Figure 3D). Finally, to understand the relationship between the change in visual findings and the change in eosinophilia, regression modeling was performed with the change in eosinophils (Δ eosinophils) as the outcome and change in score (Δ score) for each individual finding (Supplementary Table 3). Controls were included in the model for treatment type (elimination diet vs swallowed steroids) and time (between EGDs), age, and pretreatment EREFS/eosinophilia. This demonstrates the change in furrows (P < .001) and exudates (P = .001) scores independently predict the change in eosinophilia.

Discussion

The EREFS scoring system was proposed and validated as a standardized reporting of endoscopic features of EoE in adults. In this study, we evaluated the utility of EREFS for diagnosis, post-treatment surveillance, and longitudinal treatment response in children with EoE and control subjects. Although individual component scores had a poor correlation with esophageal eosinophil counts, composite scores correlated significantly. Most notably, the EREFS inflammatory score accurately distinguished newly diagnosed EoE patients from control subjects, post-treatment active from inactive EoE, and longitudinal changes associated with treatment response.

Our diagnostic cohort was notable for a high prevalence of abnormal visual findings in newly diagnosed EoE patients compared with control subjects, similar to findings in adults.12 We found a high sensitivity and specificity for edema, exudates, and furrows for EoE diagnosis consistent with previous retrospective studies.9 In contrast to a meta-analysis of endoscopic findings in EoE, all visual abnormalities were more prevalent with higher sensitivity and specificity in our study.12 This may be caused by elimination of selection and recall bias from use of a reference atlas and intra-operative real-time EREFS scoring, or perhaps by reporting from only 2 EoE specialists. The prevalence, sensitivity, and specificity of inflammatory findings (edema, exudates, furrows) was higher than for rings, supporting the concept that, at diagnosis, EoE is an inflammatory disease in children. This work further examines EREFS in the post-treatment setting, and significant differences were identified when comparing the absence (score of 0) or presence (1 or 2) of inflammatory findings. This differs from the observations by van Rhijn et al,5 who found no difference in exudates and edema between patients with active and inactive EoE. This difference could be explained by a potential recall bias because van Rhijn et al5 used retrospective review of still images from archived procedure reports. Real-time or video imaging likely provides more accurate assessment of endoscopic features, especially regarding presence of vascular markings that can vary with degree of esophageal luminal distention. This study noted the presence of active disease in all patients with severe rings,5 whereas we found no difference in rings between active and inactive disease nor treatment responders versus nonresponders. Correlation between histology and endoscopy may be enhanced from matching endoscopic and biopsy location of specific esophageal regions (proximal, mid, distal).

Consistent with prior reports, we found limited utility for EREFS scores 1 versus 2 for individual findings to distinguish eosinophil counts.5,6,13 Dellon et al4 assessed an EREFS inflammatory score, derived by adding the maximum score for edema, exudate, and furrows. We found this score well correlated with eosinophilia in all areas of the esophagus (proximal, mid, and distal), and ROC analysis showed the score accurately distinguished incident EoE from control, and post-treatment active from inactive disease. Interestingly, Dellon et al4 found the EREFS score was enhanced by weighting exudates, rings, and edema, whereas modeling in our pediatric cohort identified furrows and exudates as the strongest predictors of eosinophilia. Although a fibrotic score was found to be a good predictor of active versus inactive EoE in adults,5 our study found no difference for ring scores between active and inactive disease, consistent with the inflammatory nature of pediatric EoE.

Novel to this study is the use of the EREFS inflammatory score metric to quantify longitudinal changes in visual findings with therapy in children with EoE. A significant reduction was found in the EREFS inflammatory score in treatment responders (92%) compared with nonresponders (53%). The change in the inflammatory score predicted treatment responder status reasonably well, with an area under the curve of 0.79. Specifically, a significant correlation was found between changes in exudates and furrows scores and changes in eosinophilia independent of treatment type, time between endoscopies, and age. This identifies a role for EREFS scoring in children as an outcome metric for therapy given the strong correlation between the change in histologic inflammation and EREFS scores in treatment responders versus nonresponders. Curiously, a subset of patients in the post-treatment group with inactive EoE had inflammatory findings including furrows and edema. Whether further clinical investigation should be considered in patients who have less than 15 eos/hpf but persistent endoscopic abnormalities requires more prospective natural history studies to determine the long-term clinical, endoscopic, and histologic consequences.

A significant strength of our study is the timing and method of data collection with scores recorded real-time to an operative report limiting potential selection and confirmation bias. Additionally, our study is the first in children and adults to evaluate 3 levels of the esophagus: proximal, mid, and distal. Finally, our study is the largest prospective diagnostic pediatric EoE cohort to describe visual findings with comparison with control subjects, which enhances the generalizability of our findings.

Several potential limitations exist with our study. Endoscopists were not blinded to the patient’s medical information (demographics, medication, symptoms); however, prior endoscopy findings were not reviewed at the time of the procedure. We were unable to assess interobserver differences between endoscopists because of real-time scoring of EREFS at endoscopy rather than pictures, and no kappa coefficient was assessed. Another limitation is that intraobserver variability over the course of this 4-year study was not measured, and may have changed with time and experience. Data was assessed from only 2 endoscopists, both with experience and expertise in EoE; however, interobserver and intraobserver reliability of EREFS is strong among academic gastroenterologists,2,3 thus our findings are most generalizable to pediatric EoE specialists. A final limitation was inclusion of patients on different treatment modalities (swallowed steroids or diet elimination); however, no differences were found comparing these groups.

Conclusions

This is the first study to use EREFS scoring metric intraoperatively in children. This study demonstrates composite EREFS scores are a useful diagnostic tool and a treatment response outcome metric. These scores had a significant correlation with peak eosinophil counts in the diagnostic and post-treatment setting. We confirm the composite inflammatory score as an outcome metric to assess presence, response, and activity in children with EoE, in conjunction with clinical and histologic assessment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Buckeye Foundation, American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders and Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Disease. K08DK097721, internal funding from Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, and CEGIR. Dr. Wechsler is a CEGIR trainee. CEGIR (U54 AI117804) is part of the Rare Disease Clinical Research Network, an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research, National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, and is funded through collaboration between National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. CEGIR is also supported by patient advocacy groups including American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders, Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Disease, and EFC.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- EGD

esophagogastroduodenoscopy

- EoE

eosinophilic esophagitis

- eos/hpf

eosinophils per high powered field

- EREFS

endoscopic reference score

- ROC

receiver operating characteristic curve

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

Note: To access the supplementary material accompanying this article, visit the online version of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology at www.cghjournal.org, and at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2017.12.019.

References

- 1.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. quiz 21–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, et al. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2013;62:489–495. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Rhijn BD, Warners MJ, Curvers WL, et al. Evaluating the Endoscopic Reference Score for eosinophilic esophagitis: moderate to substantial intra- and interobserver reliability. Endoscopy. 2014;46:1049–1055. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellon ES, Cotton CC, Gebhart JH, et al. Accuracy of the Eosinophilic Esophagitis Endoscopic Reference Score in diagnosis and determining response to treatment. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Rhijn BD, Verheij J, Smout AJ, et al. The Endoscopic Reference Score shows modest accuracy to predict histologic remission in adult patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1714–1722. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodriguez-Sanchez J, Barrio-Andres J, Nantes Castillejo O, et al. The Endoscopic Reference Score shows modest accuracy to predict either clinical or histological activity in adult patients with eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:300–309. doi: 10.1111/apt.13845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dellon ES, Katzka DA, Collins MH, et al. Budesonide oral suspension improves symptomatic, endoscopic, and histologic parameters compared with placebo in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:776–786. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aceves SS, Newbury RO, Dohil R, et al. Esophageal remodeling in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:206–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Subu A, Bevins L, Yulia D, et al. The accuracy of endoscopic features in eosinophilic esophagitis: the experience in children from rural West Virginia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:e83–e86. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182471054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sundaram S, Sunku B, Nelson SP, et al. Adherent white plaques: an endoscopic finding in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;38:208–212. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200402000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lim JR, Gupta SK, Croffie JM, et al. White specks in the esophageal mucosa: an endoscopic manifestation of non-reflux eosinophilic esophagitis in children. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:835–838. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)00364-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim HP, Vance RB, Shaheen NJ, et al. The prevalence and diagnostic utility of endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis: a meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:988–996. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dellon ES. Diagnostics of eosinophilic esophagitis: clinical, endoscopic, and histologic pitfalls. Dig Dis. 2014;32:48–53. doi: 10.1159/000357009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.