Summary

Hydrogen gas-evolving membrane-bound hydrogenase (MBH) and quinone-reducing Complex I are homologous respiratory complexes with a common ancestor but a structural basis for their evolutionary relationship is lacking. Herein we report the cryo-EM structure of a 14-subunit MBH from the hyperthermophilie Pyrococcus furiosus. MBH contains a membrane-anchored hydrogenase module that is highly similar structurally to the quinone-binding Q-module of Complex I while its membrane-embedded ion-translocation module can be divided into a H+- and a Na+-translocating unit. The H+-translocating unit is rotated 180° in-membrane with respect to its counterpart in Complex I, leading to distinctive architectures for the two respiratory systems despite their largely conserved proton-pumping mechanisms. The Na+-translocating unit, absent in Complex I, resembles that found in the Mrp H+/Na+ antiporter and enables hydrogen gas evolution by MBH to establish a Na+ gradient for ATP synthesis near 100 °C. MBH also provides insights into Mrp structure and evolution of MBH-based respiratory enzymes.

In Brief

The structure of a respiratory complex from a hyperthermophilic archaeon offers insights into the evolution of mitochondrial Complex I

Introduction

The evolution of complex life from anaerobic ancestors on this planet was driven in part by the high energy yield of aerobic respiration wherein membrane-bound electron transfer from NADH to molecular oxygen is coupled in a highly efficient manner to conserve energy in the form of a proton motive force. NADH oxidation is catalyzed by proton-pumping Complex I (or NADH quinone oxidoreductase) (Hirst, 2013; Letts and Sazanov, 2017; Sazanov, 2015). Some anaerobic archaea lacking Complex I instead use a sodium-pumping mechanism to provide chemical potential for ATP synthesis (Mayer and Muller, 2014). Typical examples are the 14-subunit membrane bound hydrogenase (MBH) (Sapra et al., 2003; Schut et al., 2016b) of the hyperthermophile Pyrococcus furiosus and the closely related 18-subunit formate hydrogen lyase (FHL) (Lim et al., 2014) and 16-subunit carbon monoxide dehydrogenase (CODH) (Schut et al., 2016a) of Thermococcus onnurineus. CODH and FHL enable T. onnurineus to grow using only formate or CO as its sole energy (ATP) source. MBH, FHL, and CODH all evolve H2 gas and contain group 4 [NiFe]-hydrogenase modules. They differ mainly in that FHL and CODH have additional subunits that enable formate or CO, respectively, to serve as electron donors (Lipscomb et al., 2014; Schut et al., 2016a; Schut et al., 2016b). Hence MBH oxidizes reduced ferredoxin generated by sugar fermentation and evolves H2 gas whereas FHL and CODH oxidize formate or CO to evolve H2. In all cases, the redox reaction leads to H2 production and generates a sodium ion gradient across the cell membrane (Kim et al., 2010; Lim et al., 2014; Mayer and Muller, 2014; Sapra et al., 2003). The membrane potential established by these membrane complexes is subsequently utilized by a Na+-driven ATP synthase (Mayer and Muller, 2014; Pisa et al., 2007). Consistent with the similar mechanism of energy conservation among these complexes, both FHL (Lipscomb et al., 2014) and CODH (Schut et al., 2016a) have been heterologously-expressed in P. furiosus and the organism is then able to evolve H2 by oxidizing formate or CO and also uses CO as a source of energy for growth. Indeed, stimulation of H2 evolution by Na+ ions has been experimentally demonstrated both with FHL (Lim et al., 2014) and with MBH (Figure S1A).

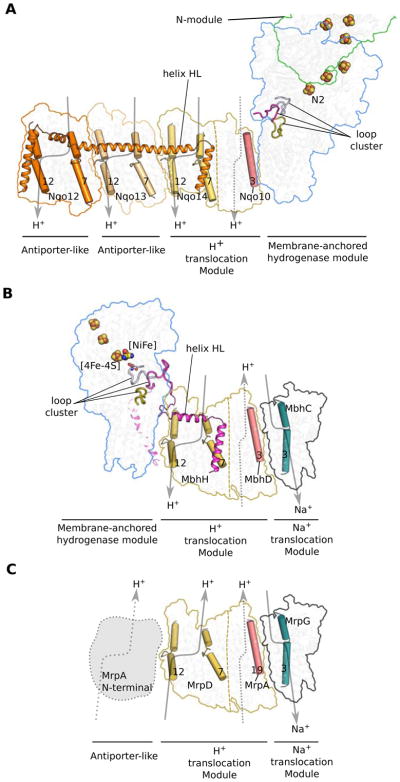

Complex I and these MBH-type respiratory complexes are evolutionarily related and share an ancestral root, which is generally considered to be the Mrp antiporter (Multiple resistance and pH antiporter) (Figure 1A) (Efremov and Sazanov, 2012; Hedderich, 2004; Sazanov, 2015). Many of the membrane-embedded ion-translocating subunits of these complexes clearly have a common ancestor (Table 1). For example, the MBH subunits D and E together, G, and H correspond to the Thermus thermophilus Complex I (NADH:quinone oxidoreductase, Nqo) subunits Nqo10, Nqo11 and Nqo14, and the C-terminal region of MrpA, MrpC, and MrpD of the Bacillus subtilis Mrp antiporter, respectively. Interestingly, Complex I lack subunits corresponding to the MBH subunits A, B, C and F and Mrp subunits E, F, G and B (Table 1) (Schut et al., 2013; Schut et al., 2016b). The Mrp antiporter system belongs to cation:proton antiporter-3 (CPA3) family. It provides resistance to high Na+ stress through a H+/Na+ exchange mechanism and plays an essential role in numerous bacteria, including pathogens, although its molecular mechanism remains a mystery due to lack of a Mrp structure (Kosono et al., 2005; Krulwich et al., 2011; Morino et al., 2010; Morino et al., 2008; Swartz et al., 2005). Notably, except for MrpA, six out of the seven Mrp subunits have homologs in MBH (Table 1), suggesting a shared Na+ translocation core module between these complexes (Schut et al., 2013; Schut et al., 2016b).

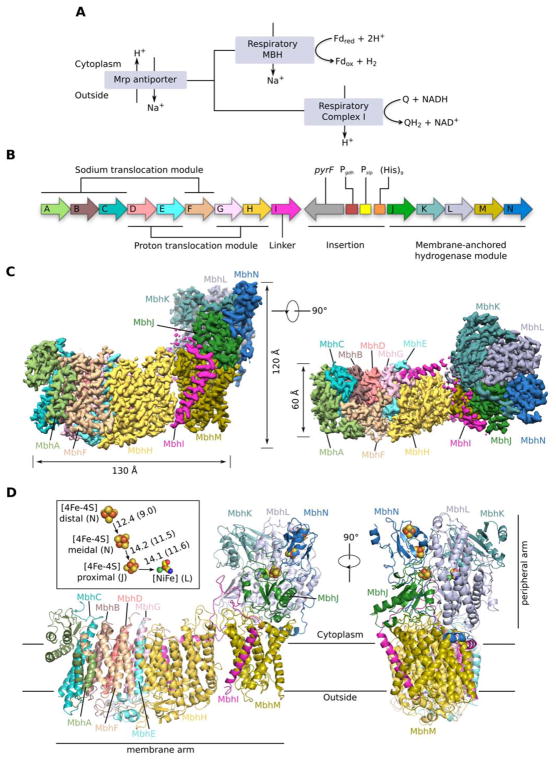

Figure 1. Overall structure of the Pyrococcus furiosus MBH.

A, The respiratory MBH complex and Complex I are evolutionarily and functionally related to the Mrp H+/Na+ antiporter system. Fdox and Fdred represent oxidized and reduced ferredoxin, respectively.

B, Operon encoding 14 subunits (MbhA-N) of P. furiosus MBH are coloured as labeled. Three modules based on the MBH structure are indicated. The operon was genetically modified for complex preparation: a Hisx9 tag was inserted to the N terminus of mbhJ with preceding promoters (Pgdh and Pslp) and selectable marker (pyrF). See Methods for more details.

C, Cryo-EM map of MBH complex segmented by subunits and viewed from the membrane side (left) and cytoplasmic side (right). Subunits are coloured as those in panel (B).

D, Two orthogonal views of the MBH structure in cartoon display. Subunits are coloured the same as in panel (B). D inset, Arrangement of three [4Fe-4S] clusters and one [NiFe]-center in the peripheral arm, viewed in an orientation as in the right panel. The distance between metal sites, including center-to-center and edge-to-edge distances (in brackets) are indicated in Å.

Table 1.

Homologous counterparts among respiratory Complex I (Thermus thermophilus), Bacillus subtilis Mrp H+/Na+ antiporter and Pyrococcus furiosus MBH

| Proposed MBH module | P. furiosus MBH complex | B. subtilis Mrp complex | T. thermophilus Complex I | Module of Complex I |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | - | Nqo15/Nqo16 | - |

| - | - | - | Nqo1/Nqo2/Nqo3 | N-module |

| Membrane-anchored hydrogenase module | MbhJ | - | Nqo6 | Q-module |

| MbhK | - | Nqo5 | ||

| MbhL | - | Nqo4 | ||

| MbhN | - | Nqo9 | ||

| MbhM | - | Nqo8 | P-module | |

| - | - | MrpA TM1-16 | Nqo12/Nqo13 | |

| - | MbhI N-terminala | - | Nqo7 N-terminal | |

| - | MbhI C-terminalb | - | Nqo12 C-terminal | |

| Proton translocation module | MbhDc | MrpA TM17-21 | Nqo10 | |

| MbhEc | ||||

| MbhG | MrpC | Nqo11 | ||

| MbhH | MrpD | Nqo14 | ||

| Sodium translocation module | MbhF | MrpB | - | - |

| MbhA | MrpE | - | ||

| MbhB | MrpF | - | ||

| MbhC | MrpG | - |

MbhI N-terminal TMH1 and its following loop are homologous to Nqo7 N-terminal TMH1 and its following loop (Figure S5B).

MbhI C-terminal lateral helix and TMH2 is homologous to Nqo12 C-terminal lateral helix and TMH16 (Figure 3D and Figure S4I).

MbhD and MbhE together are homologous to Nqo10 (Figure 3D and Figure S4H).

Herein we have used the MBH from the anaerobic hyperthermophilic microorganism Pyrococcus furiosus. This grows optimally near 100°C in marine volcanic vents and has been proposed to represent an ancestral life form (Nisbet and Sleep, 2001). MBH accepts electrons from reduced ferredoxin (Em ~ −480 mV) and reduces protons to hydrogen gas (H+/H2, Eo′ = −420 mV, pH 7; (Mayer and Muller, 2014; McTernan et al., 2014)). The energy that is conserved (ΔE = 60mV; 12 kJ/mol/2e-) is only ~15% of that conserved by Complex I (ΔE = 420mV; 81 kJ/mol/2e-), which uses NADH as the electron donor (NAD/NADH, Eo′ = −320 mV) and reduces the much higher potential acceptor ubiquinone (Em + 100 mV; (Efremov and Sazanov, 2012)). The fourteen MBH subunits are named alphabetically (Mbh A-N) and together they make up a molecular mass of ~300 kDa (McTernan et al., 2014). Like Complex I, MBH has peripheral and membrane arms. Four subunits (MbhJ, K, L and N) are predicted to be exposed to the cytoplasm and form the peripheral arm while the remaining ten (Mbh A-I, M) are predicted to be integral membrane proteins forming the membrane arm (Schut et al., 2013; Schut et al., 2016b). The peripheral arm contains the catalytic [NiFe] site (in MbhL) together with three iron-sulfur clusters (in Mbh N and J). MbhL and MbhJ show surprisingly low sequence homology to the corresponding subunits in the other three types of [NiFe] hydrogenase but they are homologous to the quinone-reducing Q-module of Complex I (Schut et al., 2013; Schut et al., 2016b). These peripheral arms are involved in coupling electron transfer to hydrogen gas production and ubiquinone reduction, respectively (Schut et al., 2013; Schut et al., 2016b). Structural knowledge of an ancient respiratory complex such as the MBH would be invaluable to understanding the functional relationships among the anaerobic H2-evolving membrane complexes (MBH, FHL and CODH) and the path that led to the evolution of Complex I of the aerobic respiratory chain. Therefore, we determined the structure of the MBH by cryo-EM single particle reconstruction and derived a 3.7-Å resolution atomic model.

Results

Structure determination

We modified the 14-gene operon encoding MBH with an insert at the N-terminus of mbhJ encoding an affinity tag (His9) (Figure 1B). The affinity-tagged MBH complex was natively expressed in and purified from P. furiosus (see methods and Figure S1C–E). Cryo-EM of the MBH resulted in a 3D density map at an average resolution of 3.7 Å; however, the transmembrane region has a better resolution of ~3.3 Å (Figures 1C and S2; Movie S1; Table S1). Most loops and many side-chain densities were well resolved in the experimental electron density map allowing de novo model building for 2470 out of the total 2502 residues of the complex (Figure S3). A 32-residue flexible loop region of MbhI (residues 42–73) was not as well resolved and only allowed for main chain tracing (Figure S3I). Like Complex I, MBH adopts an L-shaped structure with dimensions of 120 Å *130 Å *60 Å with a peripheral arm and a membrane arm (Figure 1C–D; Movie S2). The MBH atomic model represents the first structure of a group 4 [NiFe]-hydrogenase.

Membrane arm

The membrane arm of MBH contains 44 transmembrane helices (TMH) from 10 membrane-embedded subunits, Mbh A-I and M (Figures 1D and 2). The largest membrane subunit is MbhH and this features 14 TMH. Its TMH4-8 and TMH9-13 form two inverted folding units (Figure 2A–B) and each of these two 5-TMH units features a discontinuous 4th helix, TMH7 and TMH12, respectively. This fold with two discontinuous helices and internal symmetry is typically found in antiporter-like subunits of Complex I (Baradaran et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2016; Zickermann et al., 2015). Indeed, subunit H is homologous to the antiporter-like subunits T. thermophilus Nqo14, Nqo13 and Nqo12 and mammalian ND2, ND4 and ND5 (Figure 2A), which are proposed to translocate protons (Baradaran et al., 2013; Hirst, 2013; Sazanov, 2015; Zhu et al., 2016; Zickermann et al., 2015). Therefore, we suggest a similar role for subunit H in MBH. Loosely packed against the H subunit is the M subunit and this has eight TMH and anchors the peripheral arm. The M subunit also contains a 5-TMH fold: TMH2-6 with a discontinuous 4th α-helix (TMH5). This is similar to subunit Nqo8 of Complex I (Figure 2C–D), consistent with their predicted homology (Schut et al., 2013). However, it is unclear if subunit M contributes to ion translocation because it is largely separated from the main ion-translocating module by a sizable gap that appears filled by two phospholipid molecules (Figure S4A–D). Unexpectedly, a bridging subunit I ties together the otherwise separated main ion-translocating module and the subunit M-anchored peripheral module (Figure 3A).

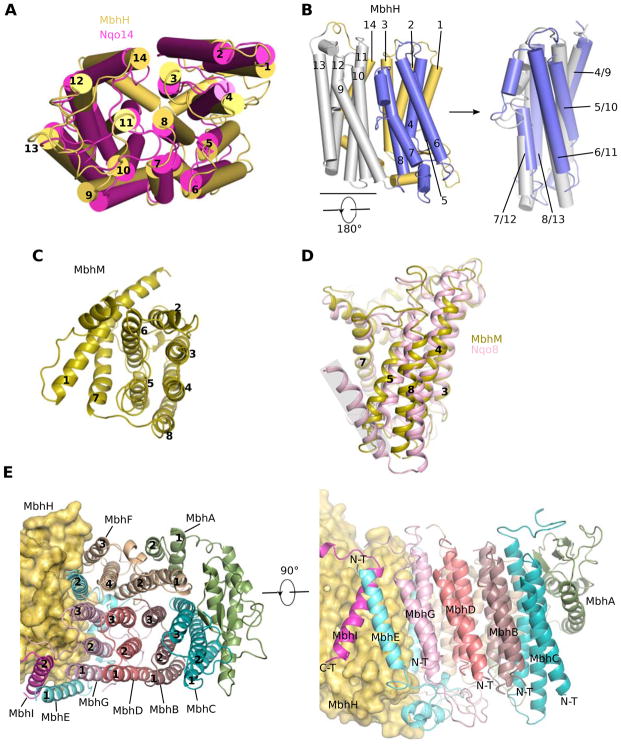

Figure 2. Structures of the MBH membrane subunits and comparisons with their corresponding subunits in Complex I.

A, Overlay of MbhH (yellow) with Nqo14 (magenta) of T. thermophilus Complex I (PDB ID 4hea) illustrates the common fold of the two antiporter-like subunits. The structures are shown as cartoons in top view – looking down the membrane plane from the cytosol. The number at the end of each helix cylinder refers to the TMH number in the primary sequence. Note that TMH7 and TMH12 are discontinuous, a hallmark of the antiporter-like subunits previously observed in Complex I.

B, Left, side view from within the membrane plane showing the detailed fold of the antiporter-like subunit MbhH. The two putative proton-translocating five-helix folding units, TMH4-8 and TMH9-13, are coloured in blue and light grey, respectively. The 180° rotation symbol underneath the gray folding unit indicates that the gray unit needs to be flipped upside down to fit the blue folding unit, as shown in the right panel. Right, the good fit between the upside-down flipped gray MbhH TMH9-13 unit with the blue TMH4-8 unit indicates an inverted arrangement of the two folding units in the antiporter-like MBH subunit H.

C, Structure of the membrane subunit MbhM in cartoon presentation as viewed from cytoplasmic side.

D, Overlay of MbhM with the Nqo8 of T. thermophilus Complex I (PDB ID 4hea) shows a conserved fold of the two proteins. TMH9 of Nqo8 (shaded area) is absent in MbhM.

E, Architecture of the seven small MBH subunits. Left panel, top view from cytoplasmic side with all TMH numbered. Right view, a side view from membrane side.

See also Figure S4.

Figure 3. The MBH membrane arm and its relationship with Complex I.

A, Top view of the MBH membrane arm from the cytoplasm. Subunits are coloured as in Figure 1D. Outlined region is the proton-translocation module containing two potential proton pathways.

B, Complex I (T. thermophilus; PDB ID 4hea) membrane arm is lined up with MBH in (A) through the alignment of their homologous subunits on the proximal end of the membrane domain: Nqo8 (Complex I) and MbhM (MBH complex). Subunits are coloured as labelled where homologous subunits between Complex I and MBH are coloured the same. Outlined region is the proton-translocation module shared with MBH but its orientation is reversed compared to that in MBH.

C, Complex I (T. thermophilus; PDB ID 4hea) is lined up with MBH via their respective antiporter-like subunits Nqo14 and MbhH. They are shown separately for clarity. The well-aligned proton-translocation modules (as outlined in panel A and B) are shown as transparent surfaces. MBH subunits are coloured as in A. Complex I Nqo12 is in orange, Nqo13 green, Nqo10, Nqo11 and Nqo14 light grey, and all the other subunits dark grey.

D, Zoomed view of the alignment as in (C). Subunits within the shared proton-translocation module are shown. Complex I Nqo8 and MBH MbhM are shown as transparent cartoon. Prominent shared features are labeled, including: (1) the discontinuous TMH7 and TMH12 of MbhH/Nqo14; (2) the lateral helix HL and the following TMH of MbhI/Nqo12 anchored to the discontinuous TMH7; (3) TMH3 of MbhD/Nqo10 with a -bulge.

E, Two potential proton translocation paths in the MBH. The discontinuous helices of MbhH (TMH7 and TMH12; featured in antiporter-like subunits of Complex I) and the -bulge helix (TMH3 of MbhD) are shown as cylinders. Polar residues lining the proton path are shown as sticks. Protonatable residues along the horizontal central hydrophilic axis are underlined. A hydrophilic axis across MbhM membrane interior is also identified but it is separated from that in MbhH due to a gap between the two subunits.

See also Figure S4.

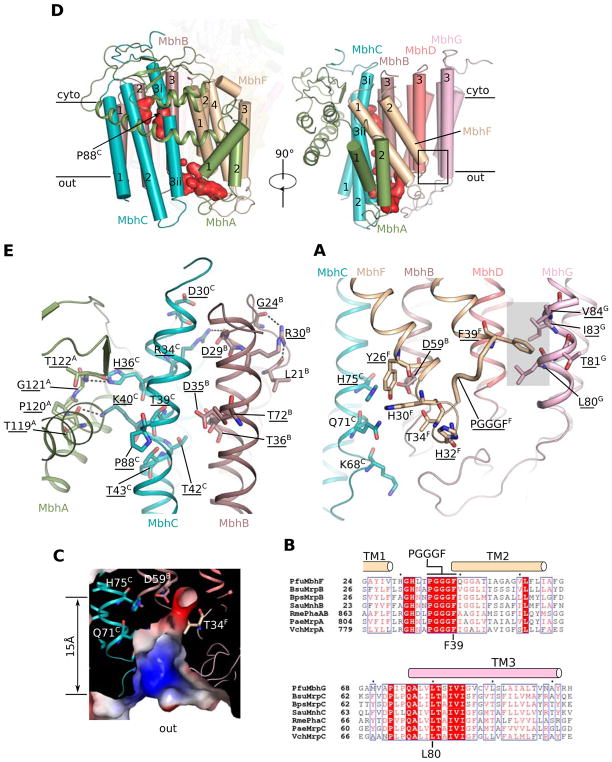

Located at the distal region of the membrane arm of MBH are seven smaller subunits, AG, that are homologous to Mrp antiporter subunits (Figure 3A; Table 1) (Schut et al., 2016b). Remarkably, MBH subunits B, C, D and G each fold into a three-helix sheet-like structure and they pack sequentially to form four contiguous layers (Figure 2E). Subunit G is sandwiched between TMH1 and TMH2 of subunit E. Subunit F contains four TMHs; two (TMH3-4) are exposed to the lipids and the other two (TMH1-2) are internal, tilted, and contact the four TMH3 of subunits B, C, D and G. At the distal end of the complex, subunit A starts with two short TMH that pack against TMH3 of subunit C and TMH1 of subunit F, followed by a long lateral helix (HL) (V60-I88), and ends with a cytosolic ferredoxin-like domain that wraps around the three TMHs of subunit C. The subunit F ferredoxin-like domain lacks the Cys residues necessary to coordinate an iron-sulfur cluster and indeed no such cluster was founded in our structure. The function of this domain is currently unknown.

The potential proton translocation subunits in the MBH membrane module

By aligning the homologous antiporter-like MBH subunit H with Nqo14 of Complex I, we identified a common core between these two respiratory complexes (Figure 3A–D): subunit H corresponds to Nqo14, G to Nqo11, and D and E combined together correspond to Nqo10 (Figure S4E–H). Notably, the MBH core is rotated 180° in-membrane with respect to that of Complex I (Figure 3A–B), giving rise to the apparently distinct architectures of the two complexes: the membrane-bound peripheral module is located to the left of the core in MBH, whereas the peripheral module in Complex I is at the right side of the core (Figure 3C). Except for this 180° in-membrane relative rotation, the two common cores are highly similar and share several important structural details: (1) MBH subunit D contains a π-bulge in the middle of TMH3 (Figure S4H); this is a structural feature observed in the corresponding TMH3 of Nqo10 of Complex I from various origins (Efremov and Sazanov, 2011; Zhu et al., 2016; Zickermann et al., 2015); (2) MBH subunit I anchors the discontinuous TMH7 of subunit H via its middle lateral helix and the C-terminal region of TMH2 (Figure 3A); this resembles another important feature observed in the Complex I structures, - the anchoring of Nqo12 onto Nqo14 (Figures 3D and S4I) (Baradaran et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2016; Zickermann et al., 2015). (3) Two chains of polar and charged residues form two putative hydrophilic channels across the membrane arm: one within the antiporter-like subunit MbhH and the other within the small subunits D, E and G (Figure 3E). They contribute two possible proton translocation pathways, which are connected via a hydrophilic central axis across the interior of this membrane core. Although there is controversy over the proton path across the small subunits in Complex I (the counterparts of MbhD, E and G) (Baradaran et al., 2013; Efremov and Sazanov, 2011; Kaila et al., 2014; Sazanov, 2015; Zickermann et al., 2015), the proposed proton paths and the central hydrophilic axis within this core MBH module are generally consistent with what has been proposed in Complex I (Baradaran et al., 2013; Efremov and Sazanov, 2011; Fiedorczuk et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2016; Zickermann et al., 2015). In summary, given the structural correspondence described above, we suggest that this core (subunits D, E, G and H) identified in MBH is a module shared with Complex I and likely functions in proton translocation.

Peripheral arm and evolutionary relationship with Complex I

The MBH peripheral arm transfers electrons from ferredoxin to reduce protons to form H2 gas (Sapra et al., 2003). This arm contains cytosolic subunits J, K, L, and N that are associated with the membrane by docking on integral membrane subunit M. The five subunits together are referred to as the membrane-anchored hydrogenase module (Figures 1B and 4A–E). The MBH subunits L and J are equivalent to the large and small subunits, respectively, of the heterodimeric core present in all known [NiFe]-hydrogenases, but their structural (and sequence) similarity are limited only to the regions that coordinate the [NiFe]-catalytic site and its proximal [4Fe-4S] cluster (Figure S5A) (Hedderich, 2004). Indeed, the MBH hydrogenase module is much more similar in both sequence and structure to the hydrophilic Q-module and the associated membrane Nqo8 subunit of Complex I (Figure S5B). These observations support the concept of modular evolution of Complex I from an H2-evolving ancestor (Efremov and Sazanov, 2012; Schut et al., 2013; Schut et al., 2016b).

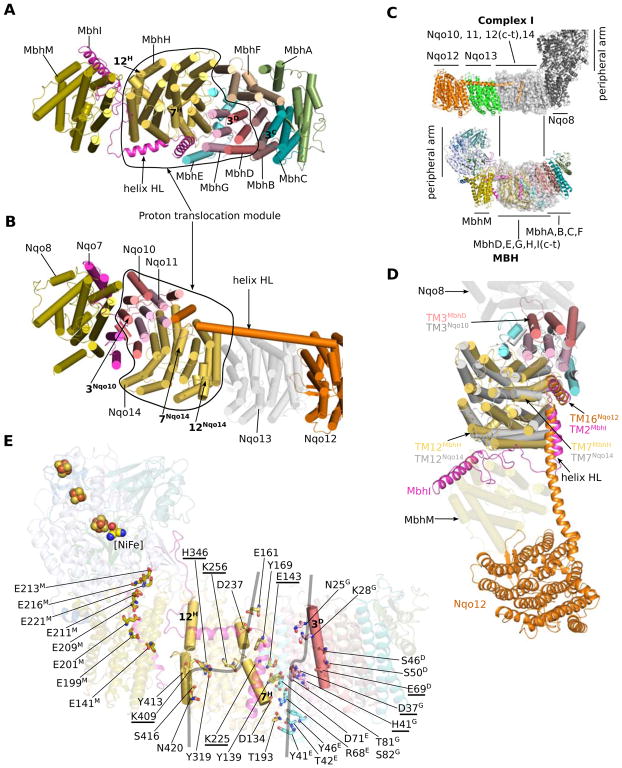

Figure 4. Peripheral hydrogenase arm.

A, Architecture of the peripheral arm of the MBH complex anchored to the membrane by MbhM, viewed parallel to the membrane. Three loops that link the first two N-terminal β-strands (β1-β2) of MbhL, TMH1 and TMH2 of MbhI, and TMH5 and TMH6 of MbhM are at the interface between peripheral and membrane arms. The hydrogen-evolving [NiFe]-center is located right above the three interfacial loops. The MBH subunits are coloured as in Figure 1D.

B, Zoomed view of the structure around the hydrogenase catalytic center. The curved dark green arrow marks a possible proton pathway from the bulk solvent to the catalytic [NiFe] center.

C, Sequence alignment of MbhL with its counterparts in selected members of group 4 energy-converting hydrogenases. EcoHycE: Escherichia coli hydrogenase-3 subunit HycE; EcoHyfG: Escherichia coli hydrogenase-4 subunit HyfG; MbaEchE: Methanosarcina barkeri hydrogenase subunit EchE.

D, A detailed comparison of the redox active sites of the MBH and T. thermophilus Complex I. The structures are aligned based on their homologous soluble subunits MBH MbhL and Complex I Nqo4. Individual subunits are coloured as in Figure S5B which shows the whole structures. In Complex I, the conserved H38 and Y87 of Nqo4 bind the quinone headgroup. The H2-evolving catalytic site of MBH is defined by MbhL E21, C374, and the [NiFe] center. Importantly, the three interfacial loops (between the peripheral and membrane arms) in MBH and Complex I are in a similar configuration to probe their respective active sites.

E, Sequence alignment of the three linker loops of MBH and Complex I as shown in (D). The protein sequences are from Pyrococcus furiosus (Pfu), Thermus thermophiles (Tth), and Ovis aries (Ova).

See also Figures S5 and S6.

As described above, the hydrogenase module and the proton-translocating membrane module are bridged by MBH subunit I, which is equivalent to a combination of the N-terminal region of Nqo7 and the C-terminal region of Nqo12 of Complex I (Figures 3D and S5B). The TMH1 of subunit I and Nqo7 are superimposable, but their second and third α-helices are configured differently: in Nqo7 they are both TMHs whereas in MBH subunit I the second α-helix is amphipathic and horizontal and only the third helix is a TMH (Figure 4D). Both MbhI and Nqo7 feature a long loop adjacent to their respective redox active sites. The MBH subunits L, J, M, and I enclose a chamber that is equivalent to the quinone-binding chamber In Complex I (Figure S5B) (Baradaran et al., 2013; Zickermann et al., 2015). The entry to the chamber is open in Complex I for quinone diffusion, but is sealed off in MBH by several bulky residues, such as F47 and F50 of subunit M (Figure S5C).

The MBH peripheral arm lacks the equivalent of the so-called N-module of Complex I, which are the three additional subunits (Nqo1-3) that oxidize NADH and, via flavin and multiple iron-sulfur clusters, channel electrons to the Q-module (Figure S6A). The four Q-module subunits of Complex I each contains an insertion loop that interacts with the N-module but these loops are not found in the homologous MBH subunits (J, K, L, and N; Figure S6B–E). These structural features confirm the evolutionary relationship between the MBH and Complex I and support the proposal that the N-module is the latest addition in the evolution of Complex I from a ferredoxin-oxidizing, hydrogen-gas evolving respiratory complex (Efremov and Sazanov, 2012; Moparthi and Hagerhall, 2011; Schut et al., 2013; Schut et al., 2016b).

A possible proton reduction mechanism of the hydrogenase module

In the MBH peripheral arm, the three [4Fe-4S] clusters form a chain and extend from the proposed ferredoxin-binding site by ~40 Å towards the interior [NiFe] site that catalyzes proton reduction to generate H2 gas (Figure 1D inset). The edge-to-edge distances between the neighboring clusters are smaller than 12 Å thereby allowing efficient electron tunneling (Page et al., 1999). The distal and medial [4Fe-4S] clusters are each coordinated by four Cys in subunit N, in a manner similar to the coordination of N6a and N6b [4Fe-4S] clusters in Complex I Nqo9 (Figure S5D). The [NiFe]-site and its proximal [4Fe-4S] cluster are also individually coordinated by four Cys in subunit L and J, respectively. This coordination scheme resembles the distantly-related dimeric hydrogenase core but it is different from that in Complex I Nqo4 as this lacks all four of the Cys that coordinate the NiFe cluster in MbhL (Sazanov and Hinchliffe, 2006) (Figure S5E–F). In the core of dimeric [NiFe]-hydrogenases, the proton is proposed to be transferred between a Cys and a nearby Glu (Dementin et al., 2004; Fontecilla-Camps et al., 2007). In MBH, E21 of subunit L likely plays the role of the Glu and donates a proton to the nearby C374 (Figure 4B). These two residues are invariably conserved among known members of group 4 hydrogenases (Figure 4C). Upstream of E21, the proton is probably taken up from the bulk solvent and transferred via β2 and β3 strands of subunit L, involving residues E23, K24, D38, K40, and Y43 (Figure 4B). Hence, although the overall sequence similarity between the dimeric cores of group 4 MBH and the other three groups of NiFe-hydrogenases is extremely low, their proton pathways may be conserved (Ogata et al., 2015; Shomura et al., 2011).

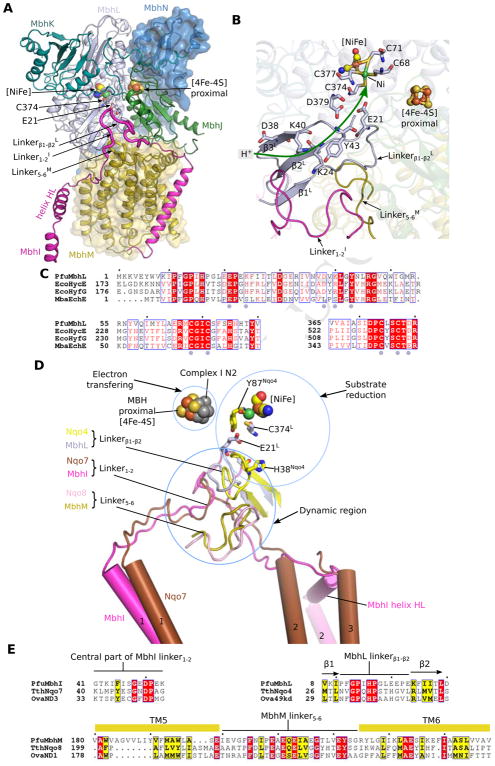

Two potential sodium-binding sites in MBH and their evolutionary relationship with the Mrp antiporter

The overall sequence identities between the Mrp subunits of the mesophilic bacterium Bacilus subtilis and their MBH counterparts range from 22–28% but there are highly conserved regions between MrpB, C, D, E, F and G and the MBH subunits F, G, H, A, B and C, respectively (Figure S7; Table 1). Interestingly, MBH subunits D and E together appear to correspond to the C-terminal region of MrpA (Figure S7F). Mrp can be separated into two stable sub-complexes, MrpA-D and MrpE-G (Morino et al., 2008). This organization is consistent with the structure of MBH in which the corresponding MBH subunits D-H and A-C are packed together, respectively (Figure 3A). Notably, we identified two negatively-charged cavities in MBH subunits A-C and F (Figure 5A) and these four subunits are equivalent to MrpE-G and MrpB, homologs of which are not present in Complex I (Table 1). Moreover, we have experimental evidence that MBH subunits A-C are involved in Na+ pumping as the deletion strain of P. furiosus lacking these three subunits (Δmbhabc) showed diminished Na+-dependent H2 evolution (Figure S1B).

Figure 5. Putative sodium translocation path in MBH.

A, Two negatively-charged cavities are identified as potential sodium-binding sites in MbhA-C and F and are shown as red surfaces. Subunits are coloured as in Figure 1D. TMHs are shown as cylinders and the MbhA ferredoxin-like domain is shown as cartoon.

B, The first cavity is halfway through the membrane where the highly conserved D35 of MbhB resides.

C, The second cavity is at the extracellular side where the highly conserved MbhB D59 is located. The extracellular linkerTMH1-TMH2 of MbhF packs against MbhG via hydrophobic interactions, shown by the shaded area, and constricts the size of the cavity opening to the solvent.

For B and C, residues highly conserved between MBH and Mrp system are underlined. Detailed sequence alignment is shown in Figure S7.

D, A cutaway electrostatic surface potential of the second cavity showing that MbhB D59 is located at the tip of a funnel-like opening.

E, Sequences of the interacting structural elements of MbhF and MbhG (shaded in C) are highly conserved in the Mrp system.

See also Figure S7.

Analyses of the negatively-charged cavities in MbhA-C suggest that they likely constitute a sodium ion translocation pathway. The first cavity reaches halfway into the membrane and is lined by the carboxyl group of the invariably-conserved D35 of MBH subunit B and by hydroxyl groups of five highly conserved residues: T36 and T72 of B and T39, T42 and T43 of C (Figures 5B and S7B–C). Together these residues could form a six coordinate site within this cavity, consistent with the binding of a single sodium ion (Kuppuraj et al., 2009). Another structural feature that supports of sodium ion binding is the presence of the conserved P88 of subunit C. It is located adjacent to conserved D35 of subunit B and breaks TMH3 of subunit C into two half-helices (TMH3i and TMH3ii) (Figure 5A–B). Such a feature (an aspartate residue near the break in the TMH in the middle of membrane) is often found H+/Na+ antiporters (Coincon et al., 2016; Hunte et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2013; Wohlert et al., 2014). Indeed, MBH subunit C P88 is equivalent to P81 in MrpG and in a previous study it was demonstrated that the H+/Na+ antiporter activity of Mrp was abolished when P81 is substituted by an alanine or a glycine (Morino et al., 2010). Adjacent to and directly interacting with the potential sodium ion-binding cavity in MbhABC is a conserved loop (119-TPGT/S-122) in the subunit A ferredoxin-like domain. Mutations of MrpE T113Y and P114G, equivalent to T119 and P120 of MBH subunit A, were found previously to significantly reduce the Mrp H+/Na+ antiporter activity (Morino et al., 2010). Interestingly, this first potential Na+-binding site in MBH faces the cytoplasm and is closed by a conserved salt bridge between D29 of subunit B and R34 of subunit C (Figure 5B). If the first cavity is truly a Na+-binding site, one might further speculate that two adjacent aspartate residues, D29 of subunit B and D30 of subunit C, may function to concentrate Na+ ions. Adjacent to the potential Na+ concentrator D29 is the conserved R30 of subunit B that stabilizes a loop around the cavity entrance. Mutations D32A and R33A in MrpF, equivalent to D29 and R30 of MBH subunit B, either abolished (D32A) or reduced (R33A) the H+/Na+ antiporter activity (Morino et al., 2010).

The second negatively-charged cavity in MBH is enclosed by TMH1 of subunit A, TMH3 of subunit B, TMH3 of subunit C, and a loop of subunit F containing the GHxxPGGGF motif that is highly conserved in Mrp antiporters (Figure 5A, C, and E). Several positively charged residues line the cavity and because this cavity faces the outside of the cell we propose that these residues may facilitate the release of Na+ ions (Figure 5C, D). The conserved and potentially Na+-coordinating D59 of subunit B in the cavity is 15 Å above the exit face and 18 Å below the potential Na+-coordinating D35 of subunit B in the first cavity. The two Na+-binding cavities are separated by several hydrophobic residues. Therefore, if the two cavities are indeed the Na+ binding sites, a conformational change would be required during a H+/Na+ translocation cycle. Interestingly, subunit F contains a pair of tilted helices (TMH1-2) that bridge the potential Na+-translocating module with the proton-translocation subunit G via hydrophobic interactions, and may just play such a role (Figure 5C, E). Consistent with this scenario, mutations that disrupt the interactions in the Mrp system, such as MrpB F41A and MrpC T75A, equivalent to F39 of MBH subunit F and T81 of MBH subunit G, resulted in a reduced tolerance of the microbes to Na+ (Morino et al., 2010).

As noted above, MrpA is the only Mrp subunit that does not have a homolog in MBH (Table 1). MrpA and MrpD are both homologous to the antiporter-like Nqo12-14 subunits of Complex I (Sazanov, 2015), where the latter are proposed to pump protons in Complex I (Baradaran et al., 2013; Fiedorczuk et al., 2016; Zhu et al., 2016; Zickermann et al., 2015). Furthermore, MrpA-D was previously shown to form a stable sub-complex (Morino et al., 2008). On the basis of these analyses, we suggest that the Mrp antiporter has an extra proton path within MrpA, in addition to those within the H+ translocation module shared with MBH (Table 1; Figure 6). Therefore, from an evolutionary perspective, MrpA appears to have been replaced by the membrane-anchored hydrogenase module - the peripheral arm attached to subunit M in MBH - converting the secondary antiporter system into a system that couples a redox reaction with ion pumping activity, as now found in MBH.

Figure 6. Comparison of the working models of Complex I, MBH and the homologous Mrp H+/Na+ antiporter.

A, A putative redox-driven proton pumping mechanism of Complex I. Sketched are the prominent features highlighted in previous studies of Complex I: three-loop cluster, lateral helix HL and the four potential proton translocation pathways (gray arrows). Note that the left three antiporter-like subunits are the primary candidates for proton translocation while the fourth proton path within the small subunits is controversial.

B, A working model of MBH. The MBH modules shared with Complex I - the membrane-anchored hydrogenase module and H+ translocation module - are differently arranged, suggesting a mechanism related to Complex I but with some variations: the redox reaction may drive the outward flow of proton through antiporter-like subunit MbhH and then the expelled proton may flow inward through the second proton path to drive the export of the sodium ion via the tentatively-identified sodium path.

C, The proposed proton- and sodium-translocation paths in MBH may be conserved in the Mrp H+/Na+ antiporter. See sequence alignment in Figure S7 and a list of subunit correspondence among MBH, Mrp, and Complex I in Table 1. MrpA, the predicted antiporter-like subunit, may contribute an extra proton path to the antiporter, as illustrated by the left dashed arrow.

For A–C, A dashed line within a proton-translocation module separate the antiporter-like subunits from the other small subunits within the same module. The curved arrows mark the potential proton- or sodium-translocation paths: the solid arrows indicate paths with stronger evidence, and the dashed arrows mark those with less certainty.

See also Figure S7.

Discussion

How modern-day Complex I evolved is a fundamental yet not well understood question. The cryo-EM structure of MBH as we have described above shows that (1) Complex I and MBH share a closely-related module in their respective peripheral arm that reduces either protons (MBH) or quinone (Complex I), which is similarly anchored to one membrane subunit (Figure S5B); (2) MBH shares a potential proton-translocation module with Complex I, despite the fact that the proton translocating module within each of these complexes is turned around with respect to their respective peripheral module (Figure 3A–B); (3) Both respiratory systems show bimodular architecture and the two modules are tied together by a similar linking structure at the peripheral arm involving MBH subunit I and Complex I Nqo7 (Figures 3A–B and S5B). However, the linking mechanism is different at the membrane arm: two TMHs of Complex Nqo7 and a lateral helix and one TMH of MBH subunit I (Figure S5B), possibly arising from the different orientation of the proton-translocation module between MBH and Complex I (Figure 3A–B). A major distinction between the two complexes is a proposed sodium ion translocation unit that is absent in Complex I but resides in subunit A-C and F in MBH and is shared with the Mrp antiporter (Figure 6; Table 1). Therefore, it appears that MBH evolved from the Mrp antiporter by acquiring the membrane-bound hydrogenase module with the concomitant loss of MrpA (Figure 6B–C). One could imagine that Complex I may have evolved from Mrp by acquiring a second proton translocation unit with an additional proton path at the expense of the sodium translocation unit, as well as acquiring the ability to reduce quinone in the peripheral arm rather than reducing protons to hydrogen gas (Figure 6A, C). These insights structurally confirm the long-recognized evolutional relationship among MBH, Complex I and the Mrp antiporter, and supports the hypothesis that they may have evolved by the assembly of prebuilt modules (Efremov and Sazanov, 2012; Hedderich, 2004; Sazanov, 2015).

Because the potential proton-translocation module of MBH is turned around when compared to Complex I and is proximal to the redox-reaction site (Figure 3A–B), it is likely that the released redox energy of ferredoxin oxidation by the hydrogenase module is coupled to pumping out a proton through the first proton path in the adjacent subunit H. Subsequently, the outside proton may flow back in via the second proton path, driving the outward pumping of a sodium ion through the proposed sodium translocation path (Figures 5 and 6B). Such a scheme is consistent with the Na+-dependent energy conservation mechanism proposed for certain anaerobic archaea, particularly involving the MBH-family member and closely-related FHL of T. onnurineus (Kim et al., 2010; Lim et al., 2014; Mayer and Muller, 2014; Sapra et al., 2003).

The structural conservation between MBH and Complex I in the redox site is somewhat unexpected, given they utilize very different electron donors and acceptors. We highlight the following three conserved features: (1) Three loops near the catalytic [NiFe] center in MBH (Linkerβ1-β2L, LinkerTM1-2I and LinkerTM5-6M; Figure 4A) show good agreement with their counterparts in Complex I (Linkerβ1-β2Nqo4, LinkerTM1-2Nqo7 and LinkerTM5-6Nqo8; T thermophilus) (Figures 4D–E); (2) The hydrogen gas-evolving catalytic [NiFe]-site of MBH (MbhL E21-C374-[NiFe]) is close to the proposed binding site of the quinone head-group in Complex I (Figure 4D) (Baradaran et al., 2013); (3) The long LinkerTM1-2I is partially disordered (Figure S3I), comparable to its counterpart (TMH1-2 loop of ND3) in a structure of the B. taurus Complex I (Zhu et al., 2016). These conserved structural features may suggest a similar energy transduction mechanism between the peripheral and membrane arms in the two complexes (Baradaran et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2016; Zickermann et al., 2015). However, the exact molecular mechanism is currently unknown in either system (Berrisford et al., 2016; Brandt, 2011; Hirst, 2013; Hirst and Roessler, 2016; Letts and Sazanov, 2017; Sazanov, 2015; Wirth et al., 2016). Indeed, the lateral helix linking unit conserved between MBH (helix HL) and Complex I is a remarkable feature (Figure 3D). Some have suggested that this helix in Complex I may function as a coupling rod to transduce the redox potential to proton translocation (Baradaran et al., 2013; Hunte et al., 2010; Sazanov, 2015; Steimle et al., 2011). However, such a role is debatable based on recent biochemical studies (Belevich et al., 2011; Hirst, 2013; Zhu and Vik, 2015). It is possible that the required energy transduction in MBH is coupled via the lateral helix of subunit I but it may simply play a structural role by cementing the two MBH subcomplexes into a stable molecular machine.

To summarize, the cryo-EM derived atomic model of MBH represents a first structure of any respiratory complex directly related to Complex I. The MBH structure has illuminated several aspects of the evolutionary relationship between Mrp antiporter and Complex I, and will serve as a starting point for mechanistic understanding of these fundamental energy-transducing systems that are ubiquitous in biology.

STAR METHODS

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and Virus Strains | ||

| Pyrococcus furiosus strain MW0414 | (McTernan et al., 2014) | MW0414 |

| Pyrococcus furiosus strain COM1 | (Lipscomb et al., 2011) | COM1 |

| Pyrococcus furiosus strain MW0574 | This study | ΔmbhABC |

| Chemicals, Peptides, and Recombinant Proteins | ||

| EPPS | Sigma | Cat#E9502 |

| n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside | Inalco | Cat#1758-1350 |

| Critical Commercial Assays | ||

| His-Trap crude FF Ni-NTA | GE Healthcare | Cat#17-5286-01 |

| His-Trap HP Ni-NTA | GE Healthcare | Cat#17-5247-01 |

| Superose 6, 10/300 GL | GE Healthcare | Cat#17517201 |

| Deposited Data | ||

| Coordinates of MBH complex | This study | PDB: 6CFW |

| Cryo-EM map of MBH complex | This study | EMDB: EMD-7468 |

| Coordinates of Thermus thermophilus Complex I | (Baradaran et al., 2013) | PDB: 4hea |

| Coordinates of D. gigas [NiFe] hydrogenase | (Volbeda et al., 1996) | PDB: 2frv |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| taccccatacttccttacttgctcgtacattctttttgaaagctctgctc | This study | UFR F |

| tgagggcctctagaatgttccgccaaacctccttaacatt | This study | UFR R |

| gaacattctagaggccctcagtggg | (Lipscomb et al., 2011) | Marker F |

| gattgaaaatggagtgagctgagttaatgatgacc | (Lipscomb et al., 2011) | Marker R |

| tcattaactcagctcactccattttcaatcgtgagaaaaatgaatcttgacatga | This study | DFR F |

| tttgagatggcatacataaccaaagcagtaacaaccccag | This study | DFR R |

| gtcctcacctcctgccctaacttgg | This study | PCR Screen F |

| cgtccggaaatctgtggagggctatg | This study | PCR Screen R |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pGL021 | (Lipscomb et al., 2011) | pGL021 |

| ΔmbhABC Knock-in cassette | This study | Knock-in cassette |

| Software and Algorithms | ||

| SerialEM | (Mastronarde, 2005) | http://bio3d.colorado.edu/SerialEM |

| FEI EPU | FEI | https://www.fei.com/software/epu/ |

| MotionCor2 | (Zheng et al., 2017) | http://msg.ucsf.edu/em/software/motioncor2.html |

| CTFFIND4 | (Rohou and Grigorieff, 2015) | http://grigoriefflab.janelia.org/ctffind4 |

| RELION-2.0 | (Kimanius et al., 2016) | http://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/relion |

| EMAN2 | (Tang et al., 2007) | http://blake.bcm.edu/emanwiki/EMAN2 |

| ResMap | (Kucukelbir et al., 2014) | http://resmap.sourceforge.net/ |

| SWISS-MODEL server | (Arnold et al., 2006) | https://swissmodel.expasy.org/ |

| CHIMERA | (Pettersen et al., 2004) | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera |

| Coot | (Emsley et al., 2010) | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot |

| PHENIX | (Adams et al., 2010) | https://www.phenix-online.org/ |

| MOLPROBITY | (Chen et al., 2010) | http://molprobity.biochem.duke.edu/ |

| PyMOL | Schrödinger, LLC. | http://www.pymol.org/2/ |

| Other | ||

| C-Flat Cu CF-1.2/1.3, 400-mesh grids | ELECTRON MICROSCOPY SCIENCES | Cat#CFT413-50 |

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Huilin Li (huilin.li@vai.org)

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Pyrococcus furiosus strain MW0414, COM1 and MW0574 were grown in defined maltose medium consisting of 1x base salts, 1x trace minerals, 1x vitamin solution, 2x 19-amino-acid solution, 10 μM sodium tungstate, 0.25 mg/ml resazurin, and 0.5% (wt/vol) maltose, with added cysteine at 0.5 g/liter, sodium sulfide at 0.5 g/liter, and sodium bicarbonate at 1 g/liter; and adjusted to pH 6.8 (Detailed buffer composition was described in the METHODS DETAILS). For protein purification, large-scale growth of P. furiosus strain MW0414 was carried out in a 20-liter fermenter at 90 °C with constant flushing of 20% (v/v) CO2 and 80% (v/v) N2 for 14 hours, while the pH was maintained at 6.8 by the addition of 10% (w/v) sodium bicarbonate.

METHODS DETAILS

Expression and purification of MBH

The MBH holoenzyme (S-MBH) was solubilized and purified anaerobically from Pyrococcus furiosus strain MW0414, in which a His9-tag had been engineered at the N-terminus of the MbhJ subunit. The procedure was as previously described with some modifications (McTernan et al., 2014). Frozen cells were lysed in 25 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, containing 1 mM DTT and 50 μg/ml DNase I (5 ml per gram of frozen cells). After stirring for one hour, the cell-free extract was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for one hour. The supernatant was removed and the membranes were washed twice using 50 mM EPPS buffer, pH 8.0, containing 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM DTT and 0.1 mM PMSF. The membrane pellet was collected by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 × g for one hour after each wash step. The washed membranes were resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 1 mM DTT, and 0.1 mM PMSF. MBH was solubilized by adding n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM, Inalco) to 3% (w/v) followed by incubation at 4 °C for 16 hours. The solubilized membranes were centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 1 hour. The supernatant was applied to a 5-ml His-Trap crude FF Ni-NTA column (GE Healthcare) while diluting it 10-fold with buffer A (25 mM sodium phosphate, 300 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, containing 1 mM DTT and 0.03 % DDM). The column was washed with 10 column volumes of buffer A and the bound protein was eluted with a 20-column volume gradient from 0 to 100 % buffer B (buffer A containing 500 mM imidazole). The eluted protein was further purified by applying it to a 1-mL His-Trap HP Ni-NTA column (GE Healthcare) while diluting it 5-fold with buffer A. A 30-column volume gradient from 0 to 100 % buffer B was used to elute the bound protein. The MBH sample was concentrated and further purified using a Superose 6 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.2, containing 300 mM NaCl, 2 mM sodium dithionite, and 0.03 % DDM.

Deletion of MbhABC

The genetically tractable P. furiosus strain COM1 was used to delete the three genes PF1423-1425. 500 bp flanking regions were amplified from P. furiosus genomic DNA for the UFR and DFR, and the selection marker (pyrF-Pgdh) was amplified by using pGL021 as the template (Lipscomb et al., 2011). The knock-in cassette was assembled using overlapping PCR (Bryksin and Matsumura, 2010). The genomic DNA was prepared using Zymobead Genomic DNA Kit (Zymo Research).

P. furiosus transformants were grown in defined maltose media as previously described (Lipscomb et al., 2011). The maltose medium was composed of 1x base salts, salts, 1x trace minerals, 1x vitamin solution, 2x 19-amino-acid solution, 0.5% (wt/vol) maltose, 10 μM sodium tungstate, and 0.25 mg/ml resazurin, with added cysteine at 0.5 g/liter, sodium sulfide at 0.5 g/liter, sodium bicarbonate at 1 g/liter, and 1 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). The 5x base salts stock solution contained (per liter): 140 g of NaCl, 17.5 g of MgSO4·7H2O, 13.5 g of MgCl2·6H2O, 1.65 g of KCl, 1.25 g of NH4Cl, and 0.70 g of CaCl2·2H2O. The 1000x trace mineral stock solution contained (per liter) 1 ml of HCl (concentrated), 0.5 g of Na4EDTA, 2.0 g of FeCl3, 0.05 g of H3BO3, 0.05 g of ZnCl2, 0.03 g of CuCl2·2H2O, 0.05 g of MnCl2·4H2O 0.05 g of (NH4)2MoO4, 0.05 g of AlK(SO4)·2H2O, 0.05 g of CoCl2·6H2O, and 0.05 g of NiCl2·6H2O. The 200x vitamin stock solution contained (per liter) 10 mg each of niacin, pantothenate, lipoic acid, p-aminobenzoic acid, thiamine (B1), riboflavin (B2), pyridoxine (B6), and cobalamin (B12) and 4 mg each of biotin and folic acid. The 25x 19-amino-acid solution contained (per liter) 3.125 g each of arginine and proline; 1.25 g each of aspartic acid, glutamine, and valine; 5.0 g each of glutamic acid and glycine; 2.5 g each of asparagine, histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, and threonine; 1.875 g each of alanine, methionine, phenylalanine, serine, and tryptophan; and 0.3 g tyrosine. A solid medium was prepared by mixing an equal volume of liquid medium at a 2x concentration with 1% (wt/vol) Phytagel (Sigma) previously autoclaved to solubilize all chemicals, and both solutions were maintained at 95°C just prior to mixing in glass petri dishes. Aliquots of P. furiosus culture typically grown to mid-log phase (2 × 108 cells/ml) in defined liquid medium were mixed with DNA at a concentration of 2 to 10 ng DNA per μL of culture, spread in 30-μL aliquots onto defined solid medium. Plates were placed inverted in anaerobic jars and incubated at 90 °C for approximately 64 hours. Colonies were picked into 4 mL of defined medium in Hungate tubes and incubated anaerobically overnight at 90 °C.

Genomic DNA, isolated using the Zymobead Genomic DNA Kit (Zymo Research), was used for PCR screening, which was carried out by using GXL polymerase (Takara, ClonTech). PCR screening was performed using a pair of primers outside the Mbh locus in order to confirm that the transformation cassette recombined into the correct locus.

Preparation of Cell Suspensions

COM1 and the ΔMbhABC strain were grown in the defined maltose medium in 1L culture bottles at 90 °C with shaking as described previously (Lipscomb et al., 2011). Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 10 minutes in a Beckman-Coutler Avanti J-30i centrifuge. Cell suspensions were created by washing harvested cells with an anaerobic resuspension buffer containing 20 mM imidazole, 30 mM MgCl2·6H2O, 0.5 M KCl, 2 mM cysteine-HCl, pH 6.5 and resuspending them in the same buffer at cell densities equivalent to OD600 = 0.6.

H2 Production Assays

H2 production assays are modified from (Lim et al., 2014). In brief, 2.0 mL of cell suspensions was added to rubber-sealed glass vials and the headspace was flushed with argon. Samples were incubated at 80 °C for 3 minutes and the reaction was initiated by the addition of the desired concentration of NaCl from an anaerobic 2 M stock solution. At various times, gas samples were removed by syringe and the amount of H2 was determined using a 6850 Network Gas Chromatograph (Agilent Technologies). Protein concentrations were measured using the Bradford Protein Assay Dye.

Cryo-EM data acquisition

For cryo-EM analysis, 3 μl aliquots of the purified MBH complex at 2–3 mg/ml was applied to a glow-discharged holey carbon grids (C-Flat Cu CF-1.2/1.3, 400 mesh). The grids were blotted for 3–4 s at 10 °C with 95% humidity and flash-frozen in liquid ethane using an FEI Vitrobot IV. Cryo-EM data collection was performed on a 300 kV FEI Titan Krios electron microscopy with a K2 camera positioned post a GIF quantum energy filter. Automated data acquisition was performed with SerialEM (Mastronarde, 2005) and FEI EPU package. Micrographs were recorded in super-resolution counting mode at a nominal magnification of 130,000×, resulting in a physical pixel size of 1.09 Å per pixel. Defocus values varied from 1.2 μm to 3 μm. The dose rate was 10.2 electron per pixel per second. Exposures of 6 s were dose-fractionated into 30 sub-frames, leading to a total accumulated dose of 51.7 electrons per Å2.

Image processing and 3D reconstruction

Two batches of data were collected. Dose fractionated movie frames were motion corrected (globally and locally), dose weighted and binned by 2 fold with MotionCor2 (Grant and Grigorieff, 2015; Zheng et al., 2017), resulting in summed micrographs in a pixel size of 1.09 Å per pixel. Contrast transfer function (CTF) parameters for each micrograph were estimated by CTFFIND4 (Rohou and Grigorieff, 2015). RELION-2.0 was used for further processing steps (Kimanius et al., 2016). Bad micrographs revealed by manual inspection were excluded from further analysis, yielding 2804 and 2155 good micrographs for each dataset. For each dataset, a manually picked sets of particles were subject to 2D classification. This generated templates for reference-based particle picking, which yielded 674,607 and 574,955 automatically picked particles, respectively. Particle sorting and reference-free 2D classification was performed to remove contaminants and noisy particles, resulting in two datasets with 636,689 and 548,230 particles, respectively. Then 3D classification was performed using an ab initio map generated by EMAN2 (Tang et al., 2007) as the initial reference model. For each dataset, one out of 4 classes with high-resolution features was obtained. The two identified good classes were combined as a new set of 301,300 particles, which was subjected to another round of 3D classification. The most populated 3D class (131,679 particles) was subsequently selected for the final 3D auto-refinement with a soft mask including the protein and detergent regions. This generated a map with an overall resolution of 3.7 Å. The resolution was estimated based on the gold-standard Fourier shell correlation 0.143 criterion (Rosenthal and Henderson, 2003). The final map was corrected for the modulation transfer function (MTF) of the detector and sharpened by applying a negative B-factor, estimated by the post-processing procedure in RELION-2.0. Local resolution distribution was estimated using ResMap (Kucukelbir et al., 2014).

Atomic model building

Most regions of the map, especially the transmembrane helices of membrane subunits, exhibit sufficient features for de novo model building of MBH, which started from the global assignment of its 14 subunits. Homology models for six subunits (hydrophilic MbhJ-MbhN and membrane MbhH and MbhM) were generated with the SWISS-MODEL server (Arnold et al., 2006) using the structure of T. thermophilus Complex I as a template (PDB ID 4hea) (Baradaran et al., 2013). They were fitted into the EM map as rigid bodies with CHIMERA (Pettersen et al., 2004). The assignments of remaining 8 membrane subunits were assisted by their predicted secondary structural features and the excellent main chain connectivity of the map. MbhF, the only membrane subunit with 4 TMHs, was assigned first. Although they all contain 2 TMH, the specific structural features of MbhA, MbhE and MbhI helped to individually locate them to the map. MbhA TM2 is followed by a ferredoxin-like fold, which was predicted by I-TASSER (Yang et al., 2015). For MbhI and MbhE, their TM1-TM2 linkers were predicted to be quite different: a long loop and a following long amphipathic helix for MbhI; a loop with a short helix in the middle for MbhE. Lastly, MbhB, MbhC, MbhD and MbhG all contain 3 transmembrane helices and they form 4 layers of three-helix bundle together. Among them, MbhC has the longest predicted helices and MbhG TM2-TM3 has the longest loop linker, which helped to locate them on the map. The positioning of last two subunits MbhB and MbhD was assisted by their sequence information.

After the subunit assignment, for the six subunits MbhJ-MbhN, MbhH and MbhM, the fitted homology models were improved by manual adjustments and rebuilding using Coot (Emsley et al., 2010). For each of the remaining 8 membrane subunits MbhA-MbhG and MbhI, a polyalanine model was first built with Coot and subsequent sequence assignment was mainly guided by bulky residues such as Arg, Tyr, Phe and Trp. In the final MBH model, 2470 of 2502 residues was assigned with side chains. MbhI loop Aa42-73 only allows the tracing of its main chain, which were built as polyalanine.

The refinement of the MBH complex model against the cryo-EM map in real space was performed using the phenix.real_space_refine in PHENIX(Adams et al., 2010). The final model was assessed using MOLPROBITY (Chen et al., 2010). All figures were prepared using PyMOL Schrödinger, LLC.) and CHIMERA. Statistics of the 3D reconstruction and model refinement were provided in Table S1.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Resolution estimations of cryo-EM density maps are based on the 0.143 Fourier Shell Correlation (FSC) criterion (Chen et al., 2013; Rosenthal and Henderson, 2003).

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

Data Resources

The accession number for the atomic coordinates reported in this paper is PDB: 6CFW. The accession number for the EM density maps reported in this paper is EMDB: EMD-7468.

Supplementary Material

Movie S1. Surface-rendered cryo-EM 3D map of the MBH complex segmented according to the 14 individual subunits, and are colored as in Figure 1C.

Movie S2. Overall structure of 14-subunit MBH complex shown in cartoon. Individual subunits are colored as in Figure 1D.

A–B, Na+-dependent H2 production activity of P. furiosus. Effect of NaCl concentration (0, 50 or 150 mM) on the H2 production activity of cell suspensions of the parent (COM1, panel A) or ΔmbhABC (B) strains. Data are represented as mean ± SEM.

C–E, Preparation of MBH for single-particle cryo-EM analysis.

C, The predicted molecular weight (kDa) of each of the fourteen MBH subunits.

D, A representative profile of size-exclusion chromatography (Superose 6 10/300 GL column) of the purified MBH complex solubilized in the detergent n-Dodecyl β-D-maltoside.

E, SDS-PAGE of the pooled gel filtration peak fractions shows the presence of all fourteen MBH subunits as labeled to the right. Molecular weight markers in kDa are labeled to the left.

A, Representative cryo-EM micrograph of the MBH particles.

B, Representative 2D class averages of the MBH particles.

C, The workflow of cryo-EM data processing. Two datasets, each contains 2804 and 2155 micrographs, respectively, were collected and processed separately during 2D classification and the first round of 3D classification. The best 3D class from these two datasets were combined for the second round of 3D classification. Then the most populated 3D class (131,679 particles, ~44% of total particles) was subjected to the final refinement, which resulted in a 3D density map with an estimated resolution of 3.7 Å. See Methods for more details.

D–F, Statistics of the cryo-EM 3D map.

D, Angular distribution of all particles used in the final 3D reconstruction (top panel) is shown with the corresponding view of the 3D map (bottom panel). The number of particles in each orientation is indicated by bar length and color (blue, low; red, high).

E, The gold-standard Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curve of the 3D map.

F, Local resolution of the 3D density map, calculated with ResMap. The range of resolution is color-coded from the higher resolution blue (3 Å) to the lower resolution red (5 Å).

A, MbhA. B, MbhB. C, MbhC. D, MbhD. E, MbhE. F, MbhF. G, MbhG. H, MbhH. I, MbhI. Densities for Aa42-73 were weak and only allowed the tracing of their main-chain atoms. J, MbhM. K, MbhJ. L, MbhK. M, MbhL. N, MbhN.

A–D, MBH complex (A, C) and Complex I (B, D; T. thermophilus; PDB ID 4hea) were aligned by the membrane subunits immediately below their respective peripheral arms: Nqo8 of Complex I vs MbhM of MBH. Side views of this comparison are shown separately in panels A (MBH) and B (Complex I). The top views are shown separately in panels C (MBH) and D (Complex I), respectively. Note the large gap between subunits M and H in MBH (A). There are four elongated densities located to the lower region of the gap (A inset; marked by blue dashed lines), which stack against several hydrophobic regions of subunits M and H. These densities are likely from two phospholipid molecules that may stabilize the structure and prevent ion leakage across the membrane bilayer. The dashed curves in panels C and D highlight the fact that the chain of hydrophilic residues found in Complex I is continuous (D), but is discontinuous in MBH (C).

E, Superimposition of the MBH complex and T. thermophilus Complex I (PDB ID 4hea), aligned based solely on their respective antiporter-like subunit MbhH and Nqo14 (as Figure 3C). By this alignment, the peripheral arm is docked to the right end of the membrane arm of Complex I and to the left end of the membrane arm of the MBH.

F–I, Structural alignment shown in (E) revealed a module shared between the MBH complex and Complex I. The corresponding subunits are superimposed and shown in panels F–I: F, MbhH and Nqo14. G, MbhG and Nqo11. H, MbhD and MbhE together are equivalent to Nqo10. Notably, MbhD TMH3 contains a -bulge that is also present in Nqo10. I, Similarity between the MbhI C-terminal region (lateral helix HL and TMH2) with the Nqo12 C-terminal region (lateral helix HL and TMH16).

A, Overlay of MBH peripheral arm with the classic dimeric [NiFe] hydrogenase from D. gigas (PDB ID 2frv) by aligning MbhL with the large subunit of the two-subunit classic hydrogenase. Only MbhL and MbhJ are visible here. The membrane subunit MbhM of MBH is also shown, although it is absent in the dimeric [NiFe] hydrogenase.

B, Overlay of MBH peripheral arm plus the membrane Mbh M and I with the corresponding T. thermophilus Complex I subunits – the Q-module and the membrane Nqo8, Nqo7. The alignment is based on MbhL and Nqo4. The two systems share a similar architecture except for the C-terminal regions of MbhI and Nqo7, suggesting that this sub-complex is well conserved between the MBH complex and Complex I.

C, Like in Complex I, there is also a chamber at the interface between the peripheral arm and the membrane subunit MbhM in the MBH complex. The internal cavity is shown as a red surface. The entry to the chamber in the MBH complex, which is equivalent to the quinone entry site in Complex I, is closed due to the presence of several bulky residues there. Structural alignment was based on MbhM (MBH) and Nqo8 (Complex I).

D–F, A comparison of coordinations of the [4Fe-4S] and [Ni-Fe] clusters in the peripheral arm of the MBH complex with those in D. gigas hydrogenase and Complex I. The structures are colored as in panels A and B.

D, The coordination of the distal and medial [4Fe-4S] clusters in MbhN (MBH) is highly similar to that in Nqo9 (Complex I).

E, The coordination of the proximal [4Fe-4S] cluster is similar between the MBH and D. gigas hydrogenase. In Complex I, coordination of the N2 cluster involves an unusual pair of tandem Cys residues (C45 and C46).

F, The side chains coordinating the [NiFe] cluster in MBH are similar to those in the D. gigas hydrogenase. The structural elements for coordinating [Ni-Fe] cluster are not present in Complex I.

A, Overlay of MBH peripheral arm and the membrane MbhM with the T. thermophilus Complex I N-module, Q-module, and the membrane Nqo8. Alignment was based on MbhL and Nqo4. Individual subunits are coloured as in Figure S5B. The N-module of Complex I, shown in cartoon as well as in transparent surface view, is peripheral and evolved later.

B–E, Structural comparisons (top panel) and sequence alignments (bottom panel) of the four N-module-interacting subunits of Complex I with their corresponding MBH subunits: B, Nqo4 and MbhL; C, Nqo9 and MbhN; D, Nqo6 and MbhJ; E, Nqo5 and MbhK. Protein sequence sources are Pfu, Pyrococcus furiosus; Tth, Thermus thermophilus; Ova, Ovis aries. Major structural differences are marked by gray ovals, and further highlighted by the gray square(s) in the sequence alignment shown below each panel.

The TMH numbers shown above the primary sequences are based on the MBH structure. The predicted secondary structural elements of Bacillus subtilis Mrp subunits are shown below the sequences. Protein sequence sources are Pfu, Pyrococcus furiosus; Bsu, Bacillus subtilis; Bps, Bacillus pseudofirmus; Sau, Staphylococcus aureus; Rme, Rhizobium meliloti; Pae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Vch, Vibrio cholera. The filled black triangles mark residues shown in Fig. 3E, and the filled black squares mark residues shown in Fig. 5B–C.

Highlights.

Atomic model of an ancient 14-protein respiratory system from P. furiosus, called MBH

A potential structure-based mechanism for coupling H+ and Na+ ion translocation

MBH has potential similarities to Mrp antiporter, formate- and CO-oxidizing systems

MBH and Complex I are closely related but with some unexpected structural variations

Acknowledgments

Cryo-EM images were collected at the David Van Andel Advanced Cryo-Electron Microscopy Suite in the Van Andel Research Institute. This work was funded by grants from the Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences and Biosciences, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE; DE-FG05-95ER20175 to M.W.W.A.), the Van Andel Research Institute (to H.L.), and the US National Institutes of Health (AI070285 to H.L.). J.W.P. was supported for contribution to the structural analysis as part of the Biological and Electron Transfer and Catalysis (BETCy) EFRC, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science (DE-SC0012518).

Glossary

The abbreviations used are

- MBH

membrane-bound hydrogenase

- Mrp antiporter

multiple resistance and pH antiporter

- Fdox

oxidized ferredoxin

- Fdred

reduced ferredoxin

- Nqo, NADH

quinone oxidoreductase

- TMH

transmembrane helices

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes one table, seven figures and two movies and can be found with this article one line.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS M.W.W.A. and H.L. conceived and designed experiments. H.Y., C.H.W., G.J.S., G.Z. and D.K.H. performed experiments. H.Y, G.J.S., M.W.W.A, J.W.P., and H.L. analyzed the data. H.Y., G.J.S, M.W.W.A., and H.L. wrote the manuscript.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung LW, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold K, Bordoli L, Kopp J, Schwede T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: a web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:195–201. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baradaran R, Berrisford JM, Minhas GS, Sazanov LA. Crystal structure of the entire respiratory complex I. Nature. 2013;494:443–448. doi: 10.1038/nature11871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belevich G, Knuuti J, Verkhovsky MI, Wikstrom M, Verkhovskaya M. Probing the mechanistic role of the long alpha-helix in subunit L of respiratory Complex I from Escherichia coli by site-directed mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol. 2011;82:1086–1095. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07883.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrisford JM, Baradaran R, Sazanov LA. Structure of bacterial respiratory complex I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1857:892–901. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt U. A two-state stabilization-change mechanism for proton-pumping complex I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:1364–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryksin AV, Matsumura I. Overlap extension PCR cloning: a simple and reliable way to create recombinant plasmids. Biotechniques. 2010;48:463–465. doi: 10.2144/000113418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, McMullan G, Faruqi AR, Murshudov GN, Short JM, Scheres SH, Henderson R. High-resolution noise substitution to measure overfitting and validate resolution in 3D structure determination by single particle electron cryomicroscopy. Ultramicroscopy. 2013;135:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen VB, Arendall WB, 3rd, Headd JJ, Keedy DA, Immormino RM, Kapral GJ, Murray LW, Richardson JS, Richardson DC. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coincon M, Uzdavinys P, Nji E, Dotson DL, Winkelmann I, Abdul-Hussein S, Cameron AD, Beckstein O, Drew D. Crystal structures reveal the molecular basis of ion translocation in sodium/proton antiporters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:248–255. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dementin S, Burlat B, De Lacey AL, Pardo A, Adryanczyk-Perrier G, Guigliarelli B, Fernandez VM, Rousset M. A glutamate is the essential proton transfer gate during the catalytic cycle of the [NiFe] hydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10508–10513. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312716200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efremov RG, Sazanov LA. Structure of the membrane domain of respiratory complex I. Nature. 2011;476:414–420. doi: 10.1038/nature10330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efremov RG, Sazanov LA. The coupling mechanism of respiratory complex I - a structural and evolutionary perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1817:1785–1795. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiedorczuk K, Letts JA, Degliesposti G, Kaszuba K, Skehel M, Sazanov LA. Atomic structure of the entire mammalian mitochondrial complex I. Nature. 2016;538:406–410. doi: 10.1038/nature19794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontecilla-Camps JC, Volbeda A, Cavazza C, Nicolet Y. Structure/function relationships of [NiFe]- and [FeFe]-hydrogenases. Chem Rev. 2007;107:4273–4303. doi: 10.1021/cr050195z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant T, Grigorieff N. Measuring the optimal exposure for single particle cryo-EM using a 2.6 A reconstruction of rotavirus VP6. Elife. 2015;4:e06980. doi: 10.7554/eLife.06980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedderich R. Energy-converting [NiFe] hydrogenases from archaea and extremophiles: ancestors of complex I. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2004;36:65–75. doi: 10.1023/b:jobb.0000019599.43969.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst J. Mitochondrial complex I. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:551–575. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-070511-103700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirst J, Roessler MM. Energy conversion, redox catalysis and generation of reactive oxygen species by respiratory complex I. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1857:872–883. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2015.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunte C, Screpanti E, Venturi M, Rimon A, Padan E, Michel H. Structure of a Na+/H+ antiporter and insights into mechanism of action and regulation by pH. Nature. 2005;435:1197–1202. doi: 10.1038/nature03692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunte C, Zickermann V, Brandt U. Functional modules and structural basis of conformational coupling in mitochondrial complex I. Science. 2010;329:448–451. doi: 10.1126/science.1191046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaila VR, Wikstrom M, Hummer G. Electrostatics, hydration, and proton transfer dynamics in the membrane domain of respiratory complex I. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:6988–6993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319156111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YJ, Lee HS, Kim ES, Bae SS, Lim JK, Matsumi R, Lebedinsky AV, Sokolova TG, Kozhevnikova DA, Cha SS, et al. Formate-driven growth coupled with H(2) production. Nature. 2010;467:352–355. doi: 10.1038/nature09375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimanius D, Forsberg BO, Scheres SH, Lindahl E. Accelerated cryo-EM structure determination with parallelisation using GPUs in RELION-2. Elife. 2016:5. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosono S, Haga K, Tomizawa R, Kajiyama Y, Hatano K, Takeda S, Wakai Y, Hino M, Kudo T. Characterization of a multigene-encoded sodium/hydrogen antiporter (sha) from Pseudomonas aeruginosa: its involvement in pathogenesis. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:5242–5248. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.15.5242-5248.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krulwich TA, Sachs G, Padan E. Molecular aspects of bacterial pH sensing and homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:330–343. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucukelbir A, Sigworth FJ, Tagare HD. Quantifying the local resolution of cryo-EM density maps. Nat Methods. 2014;11:63–65. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppuraj G, Dudev M, Lim C. Factors governing metal-ligand distances and coordination geometries of metal complexes. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:2952–2960. doi: 10.1021/jp807972e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Kang HJ, von Ballmoos C, Newstead S, Uzdavinys P, Dotson DL, Iwata S, Beckstein O, Cameron AD, Drew D. A two-domain elevator mechanism for sodium/proton antiport. Nature. 2013;501:573–577. doi: 10.1038/nature12484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letts JA, Sazanov LA. Clarifying the supercomplex: the higher-order organization of the mitochondrial electron transport chain. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2017;24:800–808. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim JK, Mayer F, Kang SG, Muller V. Energy conservation by oxidation of formate to carbon dioxide and hydrogen via a sodium ion current in a hyperthermophilic archaeon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:11497–11502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407056111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb GL, Schut GJ, Thorgersen MP, Nixon WJ, Kelly RM, Adams MW. Engineering hydrogen gas production from formate in a hyperthermophile by heterologous production of an 18-subunit membrane-bound complex. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:2873–2879. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.530725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb GL, Stirrett K, Schut GJ, Yang F, Jenney FE, Jr, Scott RA, Adams MW, Westpheling J. Natural competence in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus facilitates genetic manipulation: construction of markerless deletions of genes encoding the two cytoplasmic hydrogenases. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2232–2238. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02624-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastronarde DN. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. Journal of Structural Biology. 2005;152:36–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer F, Muller V. Adaptations of anaerobic archaea to life under extreme energy limitation. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2014;38:449–472. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTernan PM, Chandrayan SK, Wu CH, Vaccaro BJ, Lancaster WA, Yang Q, Fu D, Hura GL, Tainer JA, Adams MW. Intact functional fourteen-subunit respiratory membrane-bound [NiFe]-hydrogenase complex of the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:19364–19372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.567255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moparthi VK, Hagerhall C. The evolution of respiratory chain complex I from a smaller last common ancestor consisting of 11 protein subunits. J Mol Evol. 2011;72:484–497. doi: 10.1007/s00239-011-9447-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morino M, Natsui S, Ono T, Swartz TH, Krulwich TA, Ito M. Single site mutations in the hetero-oligomeric Mrp antiporter from alkaliphilic Bacillus pseudofirmus OF4 that affect Na+/H+ antiport activity, sodium exclusion, individual Mrp protein levels, or Mrp complex formation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:30942–30950. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.118661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morino M, Natsui S, Swartz TH, Krulwich TA, Ito M. Single gene deletions of mrpA to mrpG and mrpE point mutations affect activity of the Mrp Na+/H+ antiporter of alkaliphilic Bacillus and formation of hetero-oligomeric Mrp complexes. J Bacteriol. 2008;190:4162–4172. doi: 10.1128/JB.00294-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nisbet EG, Sleep NH. The habitat and nature of early life. Nature. 2001;409:1083–1091. doi: 10.1038/35059210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata H, Nishikawa K, Lubitz W. Hydrogens detected by subatomic resolution protein crystallography in a [NiFe] hydrogenase. Nature. 2015;520:571–574. doi: 10.1038/nature14110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page CC, Moser CC, Chen X, Dutton PL. Natural engineering principles of electron tunnelling in biological oxidation-reduction. Nature. 1999;402:47–52. doi: 10.1038/46972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisa KY, Huber H, Thomm M, Muller V. A sodium ion-dependent A1AO ATP synthase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrococcus furiosus. FEBS J. 2007;274:3928–3938. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohou A, Grigorieff N. CTFFIND4: Fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J Struct Biol. 2015;192:216–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal PB, Henderson R. Optimal determination of particle orientation, absolute hand, and contrast loss in single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. J Mol Biol. 2003;333:721–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapra R, Bagramyan K, Adams MW. A simple energy-conserving system: proton reduction coupled to proton translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7545–7550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1331436100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sazanov LA. A giant molecular proton pump: structure and mechanism of respiratory complex I. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:375–388. doi: 10.1038/nrm3997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sazanov LA, Hinchliffe P. Structure of the hydrophilic domain of respiratory complex I from Thermus thermophilus. Science. 2006;311:1430–1436. doi: 10.1126/science.1123809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schut GJ, Boyd ES, Peters JW, Adams MW. The modular respiratory complexes involved in hydrogen and sulfur metabolism by heterotrophic hyperthermophilic archaea and their evolutionary implications. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37:182–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2012.00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]