Abstract

Latino men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States are disproportionately affected by HIV, and there have been calls to improve availability of culturally sensitive HIV prevention programs for this population. This article provides a systematic review of intervention programs to reduce condomless sex and/or increase HIV testing among Latino MSM. We searched 4 electronic databases using a systematic review protocol, screened 1,777 unique records, and identified 10 interventions analyzing data from 2,871 Latino MSM. Four studies reported reductions in condomless anal intercourse, and one reported reductions in number of sexual partners. All studies incorporated surface structure cultural features such as bilingual study recruitment, but the incorporation of deep structure cultural features, such as machismo and sexual silence, was lacking. There is a need for rigorously designed interventions that incorporate deep structure cultural features in order to reduce HIV among Latino MSM.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS prevention, Latinos, men who have sex with men, systematic review

INTRODUCTION

In the U.S., HIV continues to disproportionately affect specific groups, including Latinos [1] and men who have sex with men (MSM), the latter of which remains the risk group most strongly impacted by HIV in the nation [2]. In 2014, approximately one-quarter of new HIV diagnoses in the U.S. were among Latinos, and 84% of Latino men diagnosed HIV-positive were MSM [1]. Furthermore, an estimated 63% of HIV-positive Latino MSM under the age of 30 are unaware of their status [3], and foreign-born Latino MSM have higher odds of late HIV diagnosis than their U.S.-born counterparts [4, 5]. Increased rates of HIV testing have the potential to reduce rates of onward transmission. Thus, culturally sensitive efforts to screen and treat Latino MSM diagnosed with HIV are needed.

Individual-level factors such as mental health and depression [6, 7], history of intimate partner violence, and drug and alcohol use [7, 8] have been linked to higher likelihood of HIV risk and condomless sex among Latino MSM [9]. These individual-level factors are embedded within structural factors such as poverty [10, 11], lack of health insurance and limited access to health care [12], documentation status, and language barriers [13], each of which challenges HIV prevention [14] and access to HIV testing [15, 16].

The importance of cultural factors for designing and implementing HIV prevention programs with Latino/a populations was noted early in the U.S. HIV epidemic [17, 18] and continues to be emphasized in current literature [19]. One of the most commonly cited cultural factors related to HIV risk among Latino MSM is machismo, a concept related to masculine pride [20]. For Latino MSM, machismo contributes to internalized feelings of shame, guilt, and internalized homophobia insofar as same-sex attractions and behavior are considered violations of male gender roles. Machismo also influences sexual behaviors among Latino MSM due to a perception that sexual positioning (i.e., taking the insertive versus receptive role in anal sex) connotes masculinity [21, 22]. The tension associated with violating machismo cultural norms often results in sexual silence, i.e., remaining silent about one’s sexuality. Latino MSM are particularly silent about their sexuality within their families, in an effort to preserve harmony and maintain acceptance [22], and they are vulnerable to familial rejection after disclosing their sexual orientation [23]. Relatedly, there is a phenomenon called sexual migration in which Latino MSM must relocate, sometimes leaving their home country, in an effort to escape homophobia and the stigma of family and friends [24–26]. Consequently, immigration experiences may shape the context of HIV risk for Latino MSM who migrate to the U.S. [25].

Other commonly cited cultural factors in the HIV prevention literature reflect the emphasis on social relations within Latino culture. Familismo refers to the cultural importance of family closeness and loyalty across one’s lifespan, and collectivism refers to the emphasis of close relationships and prioritization of the needs of family and community over one’s individual needs [27]. For many Latino MSM, these values exacerbate the tension between their sexuality and family expectations [22].

Other factors identified in the literature reflect codes of decorum in Latino cultures, including simpatía, respeto, and personalismo. Simpatía refers to the desire to keep interactions harmonious and conflict free, while respeto refers to the regard and deference to family and community members, particularly elders [22, 28]. Personalismo refers to the emphasis on cordial and warm interpersonal interactions. Moreover, a high cultural value is placed on religion, particularly Catholicism, which contributes to internal conflict for many Latino MSM [29].

Many of the aforementioned cultural factors have implications for behavioral HIV risk among Latino MSM [10, 29–31] and are relevant constructs for the design of HIV prevention interventions with this population [32]. There is empirical support for the general benefits of incorporating cultural factors into behavioral health interventions, based on systematic reviews of interventions for a variety of health outcomes [33–35]. For example, a meta-analysis found that mental health interventions that targeted a specific cultural group were four times more effective than those that did not [36]. Barrera et al. [37] describe four different approaches to cultural adaptation and tailoring of interventions for subcultural groups: 1) ‘the prevention research cycle’, 2) ‘cultural adaptations of evidence-based interventions’, 3) ‘investigator-initiated culturally-grounded approaches’, and 4) ‘community-initiated indigenous programs’. The prevention research cycle refers to the multi-phase process of creating interventions beginning with basic research, followed by intervention development, then moving to pilot and efficacy testing in highly controlled trials, extending to effectiveness testing in multiple sites, and culminating in implementation in community settings. Culture is generally considered at the latter stages of the prevention research cycle – specifically when assessing effectiveness and implementation in real-world settings. Cultural adaptation of evidence-based interventions refers to adaptations of previously validated interventions for the needs of a specific subcultural group, while also maintaining core elements of the original intervention. Investigator-initiated culturally-grounded approaches are those in which an investigator first conducts a needs assessment of a specific subcultural group, and then partners with group members who are actively involved in intervention development. Community-initiated indigenous interventions refer to those that are designed and implemented directly by community members themselves, in accordance with their perceived needs [37]. Resnicow et al. [28] describe two features that can guide cultural adaptations: ‘surface structure features’, which include features aimed at increasing intervention receptivity with a subcultural group, such as language and food of the target audience, and ‘deep structure features’, which include cultural values and historical and social factors that may exert influence on behaviors and impact the population’s health. Whereas cultural adaptations often involve modifications of surface structure features to make interventions more appealing to community members, cultural adaptation efforts that incorporate deep structure features may improve the impact of interventions on community members by including deeper issues of personal and cultural relevance.

Given the need for culturally sensitive HIV intervention programs for Latino MSM, we conducted a systematic review of the scientific literature to: 1) identify intervention programs that have been designed to reduce condomless sex and/or increase HIV testing among Latino MSM and summarize effects across studies and 2) describe program characteristics and the incorporation of cultural factors into HIV interventions for Latino MSM. In addition to these primary aims, we also sought to evaluate the methodological rigor of studies included in this review, in order to inform development of future interventions targeting this population.

However, it should be acknowledged that there is often population heterogeneity and differential uptake of cultural factors among Latinos. Those born in the U.S. or who have lived in the U.S. for many years may be more likely to adopt U.S. cultural views and less likely to retain traditional values of their country of ancestry/origin [38]. Sociodemographic heterogeneity within Latinos also stems from differences in origin/ancestry, race, educational attainment, and income, and may affect patterns of acculturation [39, 40]. Usage of the terms Hispanic and Latino is often conflated [41]. The term Hispanic includes individuals whose origin or ancestry is from a Spanish-speaking country [39], whereas Latino includes individuals whose origin or ancestry is from Latin America [42]. We hereafter use the term Latino unless authors used the term Hispanic.

METHODS

This systematic review followed the guidelines set forth in the 2009 ‘Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses’ (PRISMA) (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, 2009). Because our aims were descriptive rather than quantitative, and because of the anticipated heterogeneity in intervention approaches and study outcomes across studies, we sought to conduct a narrative appraisal of the literature rather than quantitatively synthesize effect sizes. We included any interventions aimed at reducing risky sexual behavior or increasing HIV testing among Latino MSM in the United States. Given our conceptual focus on culturally sensitive interventions, we included only studies that specifically targeted Latino MSM. In order to facilitate examination of cultural factors of the included studies, we excluded studies that concurrently targeted other racial/ethnic groups. Studies could target a variety of Latino male sub-populations that fall under the behavioral category MSM, including gay, bisexual, or heterosexually-identified men who have had sexual contact with other men. We included only studies conducted in the U.S. or in a U.S. territory. Studies were eligible if the intervention program was evaluated using a randomized controlled trial, quasi-randomized controlled trial, or pretest-posttest design; a control group was not necessary for inclusion. We excluded trials that did not report quantitative results on condomless sex or HIV testing. Therefore, studies that only reported outcomes related to HIV-related knowledge, intentions, or attitudes were excluded from this review. We made no exclusions based on study or publication time period, or language as we anticipated identifying literature written in English or Spanish.

Search strategy

On August 17, 2016 we searched four electronic databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and EMBASE. Our search strategy included terms related to Latino/Hispanic ethnicity; men who have sex with men and gay, bisexual, or queer sexual identity; and outcomes related to sexual behavior, HIV/STIs, and HIV testing (see Table 1 for example PubMed search strategy). For heightened sensitivity, we did not apply study design restrictions in our search. Identified studies that did not include an intervention component were manually excluded during screening. We also conducted reference searches of the included interventions. Two reviewers independently screened 30% (n=593) of unique titles and abstracts, with 99% (n=587) agreement, and one reviewer independently screened the remaining 70% of results. Considerations about the inclusion or exclusion of published reports were discussed with a third reviewer. Once full texts requiring review were identified, one reviewer independently screened all full texts.

Table 1.

Sample search term strategy: PubMed, searched on August 17, 2016

| ID | Search | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| #1 | ("hispanic americans"[MeSH Terms] OR Latino[tiab] OR Latinos[tiab] OR Hispanic[tiab] OR Hispanics[tiab] OR Hispanic*[tiab] OR chicano[tiab] OR chicanos[tiab]) | 48,464 |

| #2 | (Homosexuality, Male[Mesh] OR Bisexuality[Mesh] OR gay[tiab] OR gays[tiab] OR homosexual* OR bisexual* OR queer* OR “men who have sex with men” OR “men having sex with men” OR MSM OR LMSM OR “men who have sex with men and women” OR MSMW OR “same-sex” OR “sexual minority” OR “sexual minorities” OR “sexual orientation”) | 43,546 |

| #3 | (HIV* OR AIDS* OR HIV Infections[MeSH] OR HIV[MeSH] OR hiv[tw] OR hiv-1*[tw] OR hiv-2*[tw] OR hiv1[tw] OR hiv2[tw] OR hiv infect*[tw] OR human immunodeficiency virus[tw] OR human immunedeficiency virus[tw] OR human immuno-deficiency virus[tw] OR human immune-deficiency virus[tw] OR ((human immun*) AND (deficiency virus[tw])) OR acquired immunodeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immunedeficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immuno-deficiency syndrome[tw] OR acquired immune-deficiency syndrome[tw] OR ((acquired immun*) OR (deficiency syndrome[tw])) OR sexually transmitted* OR sexual behavior* OR condom*) | 495,298 |

| #4 | (((risk OR risk taking OR risk factor*) AND (sex[tiab] OR sexu* OR sexual behavior)) OR ("sexually transmitted diseases"[Mesh] OR "sexually transmitted"[tiab] OR STI OR STIs OR STD OR STDs OR condom OR unsafe sex OR sexual behavior OR AIDS[sb])) | 768,760 |

| #5 | #1 AND #2 AND (#3 OR #4) | 1035 |

Data extraction and assessment of methodological quality

Data were extracted by a single coder using standard forms. Details regarding study location, design, population, aims, intervention characteristics, and results were extracted and reported according to the PRISMA statement [43]. We examined four intervention characteristics that reflect surface structure features: recruiter, recruitment language, language of intervention materials, and intervention facilitator. We also examined three intervention characteristics that reflect deep structure features: community partner, formative work, and cultural components. Based on cultural factors identified in prior literature, we deductively coded for specific cultural factors - machismo, familismo, collectivism, sexual silence, simpatia, respeto, personalismo, and religion, and we inductively coded for other cultural features described in the primary reports, similar to another systematic review of interventions among Latinos in the U.S. [44]. The Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies, designed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project [45], was used to assess the methodological quality of included interventions. Interventions were assessed for selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, and withdrawals/dropouts and then assigned a global rating of strong, moderate, or weak. Studies were considered methodologically strong if at least four of the six individual criteria were rated strong and none rated weak; moderate if fewer than four criteria were rated as strong and/or one criterion was rated weak; and weak if more than one criterion was rated weak [45].

RESULTS

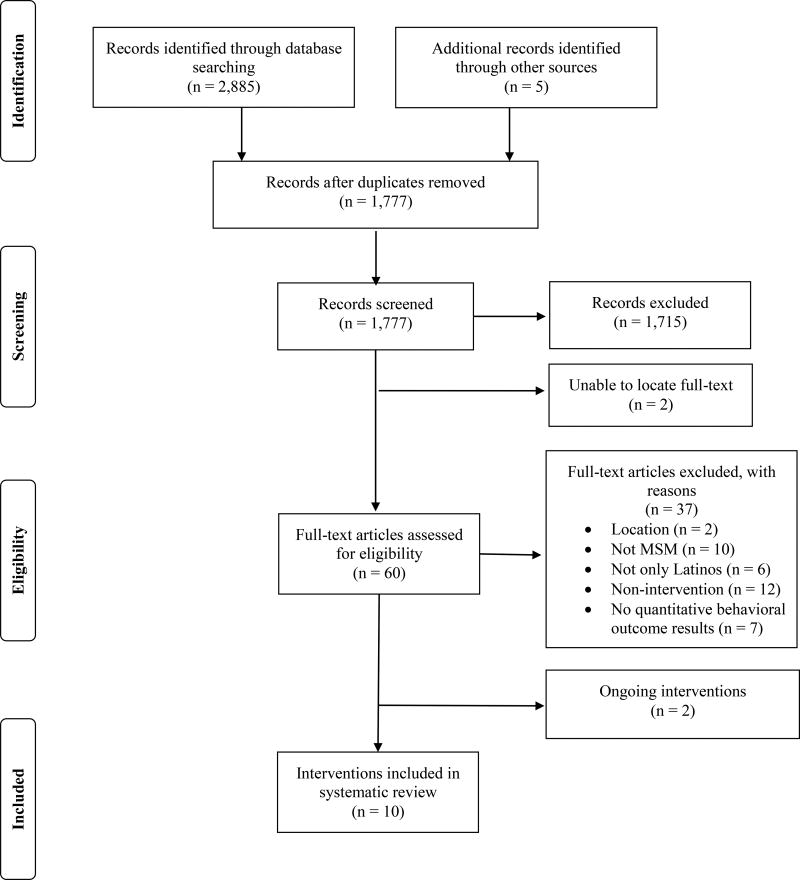

The search identified 2,890 citations containing 1,777 unique titles and abstracts, of which 1,715 were excluded during title and abstract review (Figure 1). Sixty full text articles were assessed for eligibility, 37 of which were excluded based on study location, population, or design or because quantitative behavioral outcome results were not reported. We identified 13 articles meeting inclusion criteria that reported on ten discrete interventions (some interventions yielded multiple publications identified for this review) analyzing data from 2,871 Latino MSM that met our inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

Characteristics of included interventions

Descriptions of the included interventions, including location and study population, are provided in Table 2. Of note, one intervention aimed to increase HIV testing among Latino MSM, and thus was included based on intervention design, but did not sample participants based on race/ethnicity. Rather, they compared the proportion of Latino testers during the intervention period to the proportion of Latino testers during a comparison period [46].

Table 2.

Overview of interventions for Latino MSM

| Author (year) | Intervention name / Study aim(s) |

Location (Year) |

Study design | Study population |

Intervention information & theoretical basis |

Key findings | Methodological quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carballo-Diéguez et al. (2005) |

Latinos Empowering Ourselves (LEO)

|

New York City (Dec 1998–June 2001) | RCT | Primarily foreign born, gay & bisexual Latino men aged ≥18 with ≥1 CAI act in past 2 months (Total n=180; Intervention n=90, Control n=90) |

|

|

Moderate |

| Erausquin et al. (2009) |

|

Los Angeles/West Hollywood (Aug–Oct 2004) | Discrete samples pretest/posttest | Men aged ≤25 who had sexual activity with a male (Total n=278; Intervention n=95, Comparison group n=183) |

|

|

Weak |

| Galvan et al. (2006) |

|

Los Angeles County | Discrete samples pretest/posttest | Predominantly foreign born Latino men aged ≥21 recruited at gay bars (Total n=394; gay & bisexual men n=385) |

|

|

Moderate |

| Martínez-Donate et al. (2009 & 2010) & Fernández Cerdeño et al. (2012) |

Hombres Sanos

|

Northern San Diego County (Dec 2005–Apr 2007) | Discrete samples pretest/posttest | Latino men aged ≥18 who were either alone or in the company of other men at the time of recruitment (Total: n= 1763; MSMW n=98) a |

|

|

Moderate |

| Melendez et al. (2013) |

La Familia

|

San Francisco Bay Area (Nov 2010) | CCT | Spanish-speaking, Latino immigrant MSM aged ≥18 who had lived in the U.S. for ≤10 years, living in Bay Area (total n=44; intervention n=30, control n=14) |

|

|

Weak |

| O’Donnell et al. (2014) |

Sin Buscar Excusas

|

New York City (Aug 2008–Aug 2009) | RCT | HIV- or HIV status unknown Latino men aged 18–49 who reported sex with 2+ partners in last 3 months & CAI with male partner in past 3 months (Total n=370; Intervention n=190, Control n=180) |

|

|

Strong |

| Solorio et al. (2016) & Solorio & Norton-Shelpuk (2014) |

Tu Amigo Pepe

|

Seattle, WA (Jan–May 2014) | Within subjects pretest/posttest | HIV- or unknown status, Spanish-speaking Latino immigrant men aged 18–30 who had sex with men in past 12 months (n=50) |

|

|

Moderate |

| Somerville et al. (2006) |

Young Latino Promotores

|

Vista, CA & McAllen, TX (2003–2004) | Discrete samples pretest/posttest | Latino migrant MSM aged 18–30 (n=766) |

|

|

Weak |

| Toro-Alfonso et al. (2002) |

|

Puerto Rico (1992–1995) | Within subjects pretest/posttest | Highly educated, primarily urban men who had sex with a man in the past year & who had some concerns about HIV (n=587) |

|

|

Moderate |

| Vega et al. (2011) |

SOMOS

|

New York City (2002–2006) | Within subjects pretest/posttest | Hispanic/Latino gay men, aged ≥18 living in NYC who ever had sex with male & sexually active in past 6 months (n=113) |

|

|

Moderate |

Sample as reported in Martínez-Donate et al. 2009

Refers to the 4 P’s or essential components, of marketing. They are product, price, place, and promotion.

Three interventions were evaluated using controlled trials, two of which utilized randomized allocation [3, 47] and one that utilized non-randomized allocation [26]. Three were evaluated using pretest-posttest designs [48–50], and four community-level interventions utilized a similar pretest-posttest design but with discrete samples collected at each time point [46, 51–53].

Intervention modalities varied, with five providing intervention programs to small groups of MSM. Of these, number of group sessions ranged from one to twelve. Sessions covered topics such as empowerment [47], oppression as it relates to both ethnic and sexual identity [26, 47, 49], sexual identity disclosure [26, 50], social connectedness to other Latino MSM [50], and communication with sexual partners [3, 26, 49]. Session activities included informational presentations, group discussions, and role-playing exercises. All group-session based interventions aimed to reduce condomless sex among Latino MSM. One group-based intervention, Sin Buscar Excusas, was an adaptation of another intervention, VOICES/VOCES, designed previously for African American and Latino heterosexual adults [3].

The other five interventions took a community-level approach. The first, Young Latino Promotores, was also an adaptation of a prior program, the Popular Opinion Leader intervention [54], which used promotores de salud (community health workers) to pass information regarding HIV and other STIs, sexual health, and identity to community members [53]. In an intervention aimed at increasing HIV testing, local bars were selected as program sites, and on intervention nights, a series of tests were offered, including HIV and other STI testing. On control nights, only HIV tests were offered [51].

Three interventions used community-level social marketing campaigns. In the first, men who took an HIV test during the social marketing intervention period (when outreach cards were distributed and testing information was advertised in gay/bisexual-oriented magazines and websites) were compared to men who tested during control periods when intervention outreach was not present [46]. The second, Hombres Sanos, utilized posters and postcards aimed at attracting the attention of men who have sex with men and women (MSMW), radio advertisements, community-based outreach, and offered health exams in an effort to increase condom use and HIV testing among heterosexual Latino men, particularly MSMW [52, 55, 56]. The third, Tu Amigo Pepe, entailed radio public service announcements, a campaign website with features such as an HIV testing locator and video clips, social media outreach, print materials, and a toll-free telephone line. These modalities centered around a campaign character, Pepe, who was designed to have similar characteristics as the target population, Latino immigrant MSM [48, 57]. All community-level interventions with the exception of Tu Amigo Pepe, in which the same participants completed both a pre- and post-intervention assessment, recruited discrete samples pre- and post-intervention.

Methodological appraisal

Methodological quality of intervention studies varied. Based on the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies, one intervention received a strong methodological quality rating [3], six moderate ratings [47–52], and three weak ratings [26, 46, 53]. All 10 interventions utilized convenience-sampling techniques by recruiting participants from locations frequented by the target population, such as bars, clubs, restaurants, gay pride parades, and organizations. Most interventions had a theoretical basis and two were adaptations of interventions that had been designed for other target populations [3, 53]. Among group-session based interventions, dosage ranged from one [3] to twelve sessions [26]. However, session attendance seemed to vary widely among studies that reported it, with 16.7% attending all eight Latinos Empowering Ourselves sessions [47] and 100% attending all five SOMOS sessions [50].

Of the three controlled intervention trials, one had a waitlist control group [47], one offered control group participants an HIV test [3], and the last encouraged control group participants to attend regular Latino MSM support group meetings [26]. Notably, in La Familia program, the control group was unplanned; once the target number of participants had been reached, the authors decided to create a control group. Additionally, quantitative baseline condom use results are reported for this study; authors do not report quantitative posttest results but state that intervention results were not significant [26].

Of the pretest-posttest intervention studies, four collected different samples at baseline and post-intervention and not all post-intervention participants may have engaged with the intervention program [52, 53], making these studies less methodologically rigorous than the three studies that utilized a traditional within subject pretest-posttest design [48–50].

Cultural components of interventions

Table 3 presents information about the cultural features (surface structure and deep structure features) of the included interventions. Table information is missing for interventions that did not directly report these components. Two interventions reported that recruiters were bilingual and bicultural [47, 52, 55], two reported recruiters were young Latino gay/bisexual men or MSM [46, 53], one reported recruiters were peers from local social networks [50], and five reported recruiters were trained research staff or did not specify [3, 26, 48, 49, 51]. Six intervention studies clearly reported that recruitment took place in both English and Spanish [46, 47, 50–53] and four stated that the intervention was available in English or Spanish [3, 47, 51, 53]. Intervention materials of three studies were in Spanish [48, 52, 56, 57]. Two intervention studies reported facilitators were bilingual and bicultural [47, 52], and one reported they were members of the target population, migrant Latino MSM [53]; the remainder did not report this information.

Table 3.

Cultural features of included interventions

| Author (year) | Intervention name |

Recruiter | Recruitment language |

Language of intervention materials |

Intervention facilitator |

Community partner |

Formative work | Cultural components |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carballo-Diéguez et al. (2005) | Latinos Empowering Ourselves (LEO) | Bilingual and bicultural | English and Spanish | English and Spanish | Gay male bilingual and bicultural psychologist | Hispanic AIDS Forum |

|

Machismo Sexual silence Dichos (proverbs) |

| Erausquin et al. (2009) | Young, gay/bisexual, Latino volunteers | English and Spanish | N/A | N/A | Los Angeles Gay and Lesbian Center (LAGLC) |

|

Sexual silence | |

| Galvan et al. (2006) | Project staff | English and Spanish | English and Spanish | N/A | ||||

| Martínez-Donate et al. (2009 & 2010) & Fernández Cerdeño et al. (2012) | Hombres Sanos | Bilingual and bicultural | English and Spanish | Spanish | Bilingual and bicultural staff provided health exams | Local community clinic |

|

Sexual silence Machismo Familismo Collectivism Doble sentido (double meanings) |

| Melendez et al. (2013) | La Familia | Project staff | San Francisco AIDS Foundation (SFAF) |

|

Sexual silence Familismo | |||

| O’Donnell et al. (2014) | Sin Buscar Excusas | Trained research staff | English and Spanish | Hispanic AIDS Forum & Callen-Lorde Community Health Center |

|

|||

| Solorio et al. (2016) & Solorio & Norton-Shelpuk (2014) | Tu Amigo Pepe | Spanish | N/A | Entre Hermanos Gay City |

|

Sexual silence Personalismo Familismo | ||

| Somerville et al. (2006) | Young Latino Promotores | Young Latino MSM | English and Spanish | English and Spanish | Young migrant Latino MSM | Valley AIDS Council (McAllen) & Vista Community Clinic (Vista) |

|

Machismo Sexual silence Familismo Promotores de salud |

| Toro-Alfonso et al. (2002) | Trained volunteers | Spanish | Peer educators | Puerto Rico AIDS Foundation | Sexual silence Machismo Personalismo Religion | |||

| Vega et al. (2011) | SOMOS | Peers who were part of local social networks | English and Spanish | Latino Commission on AIDS |

|

Sexual silence Machismo Collectivism |

Nine of the ten interventions reported having a community partner, most commonly a community-based organization. One was an LGBTQ health organization [46], another a Latino LGBTQ organization [48], and one an organization focused on HIV among Latinos [50]. The remaining organizations were not characterized but seemed to focus on HIV-related work. Organizations were involved in intervention development and dissemination to varying degrees, such that in some cases they helped with recruitment and/or offered a space to conduct intervention programs, whereas a few programs were CBO-initiated [26, 46, 49]. Nearly all interventions reported having conducted formative work with the target population, most often in the form of focus groups, which is critical to ensuring the program targets the needs of the population in a way that is acceptable to community members. However, our search identified few references focusing on intervention development of the included studies. We identified separate intervention development and results publications for two included interventions [56, 57]. Intervention development information is important to understand the extent to which community members were involved in program development and implementation, which may impact program effectiveness.

We sought to extract detailed information about how each intervention uniquely considered cultural determinants of HIV risk and/or testing and incorporated cultural factors into the program. Overall, relevant information about cultural factors was limited. Intervention studies often noted the general importance of cultural considerations when designing interventions for Latino MSM, and eight described cultural components in ways consistent with our inductive codes [26, 46–50, 52, 53, 56], but they seldom described how these components were incorporated into particular intervention activities. The most common cultural components of included interventions were machismo and sexual silence. Inductively coded components included dichos (proverbs) [47], doble sentido (double meaning) [52, 56], and promotores de salud [53], but each was identified in only one program respectively. Authors seldom directly tied these components to specific aspects of intervention design and implementation. However, in one intervention for heterosexually identified MSM, secrecy of same-sex practice formed the foundation of the intervention and influenced campaign advertisements, reflecting the concept of sexual silence [56].

Behavioral outcomes

Six intervention studies reported rates of condomless anal intercourse (CAI) [3, 26, 47, 49, 52, 53], one calculated HIV risk index scores and reported number of sexual partners [50], and five reported HIV testing behavior [3, 46, 48, 51, 52]. Additional reported outcomes related to condom use attitudes and beliefs [48], disclosure of sexual identity [26], self-esteem, and self-efficacy as it relates to sexual behavior [26, 50].

Two of the three controlled trials reported no significant group differences in CAI [26, 47]. The third controlled trial reported higher odds of condom use at last sex and a significantly greater decline in mean number of CAI acts among the intervention group compared to the control group. In post-hoc age-stratified analyses, among those younger than 40, a higher proportion of intervention participants used condoms at last sex, had more positive condom attitudes, and received an HIV test after the study, while control participants had higher odds of not using condoms with their past two sexual partners [3].

Four interventions used pretest-posttest designs to evaluate CAI/sexual risk, and all found significant behavioral risk reductions. Somerville et al. [53] found decreases in receptive CAI post-intervention but no significant differences in insertive CAI. Martínez-Donate et al. [52] found that compared to baseline, MSMW participants reported significantly lower odds of CAI 60 days post-campaign and fewer partners during the campaign compared to baseline. Vega et al. [50] reported significantly fewer sexual partners and lower HIV risk index at 90-day follow-up, and fewer sexual partners remained significant at 180-day follow-up. Toro-Alfonso et al. [49] found a significant reduction in overall sexual practices index, which included reduction in receptive and insertive CAI, reduction in medium-risk sexual behavior, and increase in low-risk sexual behavior.

Three studies primarily aimed to increase HIV testing. Erausquin et al. [46] reported characteristics of those who received outreach and who received an HIV test during the intervention period and found that those who tested during the intervention period were more likely to be Latino than those who tested during a previous summer. Galvan et al. [51] found that bundling HIV testing with other screenings did not increase rates of HIV testing. Solorio et al. [48] aimed to increase HIV testing via a social marketing campaign. They also did not observe significantly higher rates of HIV testing. However, by post-campaign 32 men had requested home-based HIV testing kits, among whom 28 used the kits.

DISCUSSION

Our systematic review identified ten interventions aimed at reducing sexual risk behavior and/or increasing HIV testing among Latino MSM. Findings across studies were mixed, such that four reported reductions in CAI and one reported reductions in number of sexual partners, whereas the remaining studies did not report significant findings. Although all studies noted the importance of culturally sensitive HIV programs, descriptions of the implementation of cultural factors into intervention activities were lacking. Few studies directly incorporated the cultural factors we previously reviewed and hypothesized as relevant to HIV risk among Latino MSM.

All interventions included in our review incorporated cultural surface structure features aimed at increasing receptivity with Latino MSM, such as bilingual study recruitment materials and intervention delivery and recruitment by individuals of similar identities as the target population. However, while many studies acknowledged the importance of considering deep structure cultural features in intervention development for this population, most reports did not describe in detail how they incorporated deep structure features into their programs. Four of the five interventions that found significant reductions in sexual risk behavior incorporated machismo and sexual silence in some capacity, which indicates a useful starting point for future culturally relevant interventions. Other cultural factors that we inductively coded for included the concept of doble sentido as a play on words/images for a social marketing campaign (e.g. playing off the fact that chile is sometimes used in Mexican slang to refer to the penis) [56], which enabled researchers to discretely target their sample population (MSMW). Another intervention incorporated dichos (culturally recognized proverbs) into intervention exercises in order to enhance the cultural sensitivity of the intervention [47]. In addition to these factors for which we inductively coded, there may also be other cultural factors emerging in literature that are relevant to consider in interventions targeting Latinos. For example, Arciniega et al. [58] conceptualized and developed a scale that distinguishes between traditional machismo, which often has a negative connotation of masculinity, and caballerismo which carries a more positive connotation, referring to chivalrous values associated with masculinity.

More emphasis on describing and publishing formative work leading to the evaluation of interventions is recommended to specify how cultural features are incorporated into targeted interventions for Latino MSM. Often this work goes unpublished or is undervalued do to the prioritization within many scientific communities of efficacy trials over descriptions of program development or other formative research. More detailed descriptions of the cultural underpinnings and community relevance of HIV programs for Latino MSM – as well as for other groups – are essential to guide the development and implementation of complex, culturally appropriate programs. Although several studies in this review reported on culturally relevant demographic characteristics of the study sample - i.e. the proportion of foreign-born persons and participants’ language preferences - these are merely two components related to the complex concept and multidimensional process of acculturation. Other important components of acculturation include cultural values (such as machismo and religion) and cultural identifications [38], both of which warrant detailed descriptions in future reports [33–35]. This would facilitate integration of deep structure features into intervention programs and would enable researchers and providers to develop more culturally appropriate interventions that move beyond translation of intervention materials and other cultural surface structure features. As the HIV prevention field moves toward biomedical prevention, it is continually important to identify factors that may be associated with uptake of biomedical prevention strategies among Latino MSM, in order to maximize intervention impact.

Although most studies identified in our review utilized theoretical frameworks, few integrated acculturation-related factors into these frameworks. Two studies used Paulo Freire’s empowerment theory, which is aimed at empowering marginalized communities [59], and one used social identity theory [60], which emphasizes the influence of group membership on individual behaviors. However, as Schwartz et al. [38] report, acculturation is not a ‘one size fits all’ process, which highlights the importance of understanding your target audience. Experiences are shaped not only by race/ethnicity and country of origin but also reason for immigration, generation, socioeconomic status, whiteness, presence of ethnic and immigrant enclaves, and many other factors [38, 61]. Although no single accepted acculturation model exists, a commonality is that emerging models promote a more nuanced approach to investigating the associations between acculturation and health [38, 61]. In the case of sexual minority Latino men, this nuanced approach is particularly important given cultural identity and sexual identity may interact to subsequently impact behavior.

In addition to these considerations about the inclusion and reporting of cultural components in HIV interventions for Latino MSM, this review calls attention to the sparse number of interventions, particularly methodologically rigorous interventions, targeting condomless sex and HIV testing among Latino MSM. There have been calls for culturally sensitive programs targeted at this population since early in the HIV epidemic in the U.S. [18, 62], yet such intervention programs are still urgently lacking. Programming with this population is, in large part, conducted by community-based organizations (CBOs) dedicated to underserved communities. These organizations often operate under limited resources, and generally do not have time, staff, and funding to support the publication of their efforts. The wealth of experiential and professional knowledge within these organizations is crucial for advancing the nation’s HIV prevention efforts, but their knowledge is often overlooked. Indeed, the CDC’s criteria for identifying evidence-based HIV prevention programs rely primarily on methodological characteristics of the study evaluation (e.g., presence of a control group) [63], rather than community relevance or cultural specificity. Methodologically rigorous practices, such as a control group, may not be feasible for CBOs due to a variety of reasons, including limited financial resources and limited personnel. Furthermore, it may not be acceptable to deny programming from CBO clients who are assigned to a control group, limiting the feasibility of controlled studies. This is an important consideration given most of the interventions identified in this review involved partnerships with community organizations or were CBO-initiated programs.

Several intervention studies that did not meet inclusion criteria for this review provided more thorough description of the cultural components of programs aimed at reducing sexual behavior risk among Latino MSM [64–67]. For example, Morales [64] describes development of a program for Latino gay and bisexual men by Asociación Gay Unida Impactando Latinos/Latinas a Superarse (AGUILAS), the focus on Latino cultural values such as machismo, simpatía, and respeto at this community based organization, and how intervention activities relate to some of these cultural values. Another ethnographically informed study reports obstacles encountered in program implementation, including a desire for socialization among study participants rather than an emphasis on educational activities [65]. Because such studies did not report quantitative findings, these intervention programs were not included in our review. However, they highlight the importance of CBO efforts to cater programming to their target audience and incorporate cultural values.

Given the continued rise in HIV diagnoses among Latino MSM in the U.S., programs targeted at this population are needed to reduce behavioral risk and diagnose HIV infections in order to enroll men in treatment early to curb onward transmission. Although five included studies reported behavioral risk reduction, only one group-based program reported significant effects on number of unprotected sex acts and condom use at last sex [3]. The two other group-based interventions used a within-subjects pretest-posttest design and reported significant effects on CAI [49], HIV risk index scores, and number of sexual partners [50]. One of the three social marketing campaigns reported significant effects on CAI [52], as did the adaptation of the Popular Opinion Leader intervention [53]. Meta-analysis was not conducted due to heterogeneity in study designs and outcomes. However, based on the reported study findings, five studies showed evidence of intervention success.

Notably both adaptations of prior interventions reported significant effects on condomless sex [3, 53]. One study, Sin Buscar Excusas, was an adaptation of an intervention originally developed for African American and Latino heterosexual adults. Adaptation was conducted following guidelines from the CDC Replication of Effective Programs project. The other intervention, Young Latino Promotores, was an adaptation of the Population Opinion Leader intervention and was implemented through capacity building assistance to CBOs. Several other subculture-specific guides for cultural adaptation exist, including a CDC guide to adapting HIV interventions for Black and Latino gay and bisexual men [68] and the CHANGE approach, developed by a Latino Commission on AIDS program, which provides guidelines for community based organizations to implement identified effective behavioral interventions through a community-centered model [69].

In recent years, the CDC has made significant push for the adaptation of evidence-based behavioral interventions through its High Impact HIV/AIDS Prevention Project (HIP). While this offers a potential avenue to strengthen the methodological rigor of targeted interventions [70], including those among Latino MSM, there are numerous barriers to the implementation of these programs by CBOs. Implementation often necessitates adaptation of the original intervention, which should go beyond language adaptation and the changing of images to portray people of the same race/ethnicity. This means that adaptation will require significant resources, which CBOs may lack. Additionally, when evidence-based interventions are originally designed and tested, they are often carried out with greater resources than are available to many CBOs. Research has suggested that implementation guidelines should be clarified and greater follow-up provided in order to mitigate implementation challenges [71].

Our literature search also identified two interventions for Latino MSM with quantitative results not yet reported. The first is Hola en Grupos, a small-group intervention in North Carolina aimed at increasing condom use and HIV testing behavior. The intervention is based on social cognitive theory and the theory of empowerment and consists of four group sessions delivered in Spanish [72, 73]. The second, Conectando Latinos en Pareja, is an adaptation of a four-session intervention based on social cognitive theory, originally designed for Black MSM and their same-sex partners (Connect ‘n Unite) [74]. The adapted intervention incorporates behavioral and biomedical, as well as social and cultural, strategies to target HIV prevention among this population [75, 76]. Additionally, in 2013 the CDC ran a bilingual campaign, Razones/Reasons, aimed at increasing HIV testing among gay and bisexual Latino men, but program results have not been released [77].

It is important to note the limitations of this review. Although we used an a priori systematic search strategy of the published literature, this review may not be comprehensive due to our stringent inclusion criteria that prioritized studies reporting quantitative findings. Furthermore, we included only interventions that specifically targeted Latino MSM and excluded those that simultaneously targeted other racial/ethnic groups. Although this was decided given the cultural focus of our review, we may have missed interventions that simultaneously targeted other racial/ethnic groups but tailored their intervention to participants’ race/ethnicity and included cultural components. Additionally, although we aimed to distinguish between surface and deep structure features of the included interventions, the categories may not be mutually exclusive. Moreover, the amount of culture-related information available in included studies could have been limited for a variety of reasons, such as publication length, thus impacting our results.

The cultural factors that we examined may be more applicable to some study populations than for others, which may have impacted our results. Although the cultural factors we examined are commonly associated with Latinos broadly, their applicability may vary by subgroup and level of acculturation, perhaps biased towards Mexican-Americans who comprise the majority of Latinos in the U.S. Our review was also limited by lack of diversity of the study samples. Nearly all studies were conducted in urban centers and thus are not representative of Latinos living in non-urban areas in the U.S. Several included studies described predominantly foreign-born and/or Spanish-speaking samples, who are likely to have experienced lower levels of acculturation than U.S.-born and/or predominantly English-speaking samples. Although most studies characterized sample nativity status, they did not report country of birth, except for three studies that reported percent born in Mexico. Future research should consider country of origin/ancestry as a potential moderator. The relationship between culture and condomless anal sex/HIV testing may also be changing with time, but we were unable to investigate this given the relatively short publication period and number of included studies. The review also is prone to the effects of publication bias, in which studies with negative or null findings are likely to remain unpublished. As noted, a meta-analysis was deemed inappropriate due to the mixed study designs and reported outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

To our knowledge this is the first systematic review of interventions designed to reduce condomless sex and/or increase HIV testing among Latino MSM. One other systematic review of interventions targeting risky sexual behavior among Hispanics was found, but this review, conducted in 2007, included interventions targeted at Hispanics broadly, and therefore, the majority of the included interventions were not targeted at MSM [44]. Through investigating interventions specifically conducted with Latino MSM, we were able to investigate whether interventions incorporated cultural features that have been identified as potential behavioral determinants for this population. Our systematic review demonstrates that the number of interventions targeting condomless sex and HIV testing among Latino MSM in the U.S. is sparse [78]. Descriptions about the incorporation of deep structure cultural features into HIV interventions were limited, which may reflect the field’s emphasis on reporting methodological study criteria in research publications rather than providing cultural or community details about the interventions. Some of the cultural concepts featured in successful interventions include machismo and sexual silence. Future research targeting risky sexual behavior and/or HIV testing among this population should aim to better incorporate and describe deep structure cultural features. Furthermore, there is a need for rigorously designed interventions, which requires that more resources be dedicated to these efforts. Given the high burden of HIV among this population, interventions are imperative to curbing the continued growth of HIV and identifying and treating infections among Latino MSM.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was in part funded by the National Institutes of Health under grant U24AA022000.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to report.

COMPLIANCE WITH ETHICAL STANDARDS

Ethical approval: This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV among Hispanics/Latinos. 2016 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/racialethnic/hispaniclatinos/

- 2.Neme S, Goldenberg T, Stekler JD, Sullivan PS, Stephenson R. Attitudes towards couples HIV testing and counseling among Latino men who have sex with men in the Seattle area. AIDS Care. 2015;27(10):1354–9. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1058894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Donnell L, Stueve A, Joseph HA, Flores S. Adapting the VOICES HIV behavioral intervention for Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(4):767–775. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0653-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheehan DM, Trepka MJ, Dillon FR. Latinos in the United States on the HIV/AIDS care continuum by birth country/region: a systematic review of the literature. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(1):1–12. doi: 10.1177/0956462414532242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen NE, Gallant JE, Page KR. A systematic review of HIV/AIDS survival and delayed diagnosis among Hispanics in the United States. J Immigr Health. 2012;14(1):65–81. doi: 10.1007/s10903-011-9497-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rhodes SD, Martinez O, Song EY, Daniel J, Alonzo J, Eng E, Duck S, Downs M, Bloom FR, Allen AB, Miller C, Reboussin B. Depressive symptoms among immigrant Latino sexual minorities. Am J Health Behav. 2013;37(3):404–13. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.37.3.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Poppen PJ, Reisen CA, Zea MC, Bianchi FT, Echeverry JJ. Predictors of unprotected anal intercourse among HIV-positive Latino gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2004;8(4):379–89. doi: 10.1007/s10461-004-7322-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez MI, Bowen GS, Varga LM, Collazo JB, Hernandez N, Perrino T, Rehbein A. High rates of club drug use and risky sexual practices among Hispanic men who have sex with men in Miami, Florida. Subst Use Misuse. 2005;40(9–10):1347–62. doi: 10.1081/JA-200066904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman MB, Diaz RM, Ream GL, El-Bassel N. Intimate partner violence and HIV sexual risk behavior among Latino gay and bisexual men. J LGBT Health Res. 2007;3(2):9–19. doi: 10.1300/J463v03n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marin BV. HIV prevention in the Hispanic community: sex, culture, and empowerment. J Transcult Nurs. 2003;14(3):186–92. doi: 10.1177/1043659603014003005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ayala G, Bingham T, Kim J, Wheeler DP, Millett GA. Modeling the impact of social discrimination and financial hardship on the sexual risk of HIV among Latino and Black men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(Suppl 2):S242–249. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oster AM, Russell K, Wiegand RE, Valverde E, Forrest DW, Cribbin M, Le BC, Paz-Bailey G. HIV infection and testing among Latino men who have Sex with men in the United States: the role of location of birth and other social determinants. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz JL, Orellana ER, Walker DD, Viquez L, Picciano JF, Roffman RA. The Sex Check: the development of an HIV-prevention service to address the needs of Latino MSM. J Gay Lesbian Soc Serv. 2005;18(1):37–49. doi: 10.1300/J041v18n01_04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sumartojo E. Structural factors in HIV prevention: concepts, examples, and implications for research. Aids. 2000;14(Suppl 1):S3–10. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200006001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joseph HA, Belcher L, O’Donnell L, Fernandez MI, Spikes PS, Flores SA. HIV testing among sexually active Hispanic/Latino MSM in Miami-Dade County and New York City: opportunities for increasing acceptance and frequency of testing. Health Promot Pract. 2014;15(6):867–880. doi: 10.1177/1524839914537493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solorio MR, Currier J, Cunningham W. HIV health care services for Mexican migrants. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;37(Suppl 4):S240–51. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000141251.16099.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marin G. AIDS prevention among Hispanics: needs, risk behaviors, and cultural values. Public Health Reports. 1989;104(5):411–415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carballo-Diéguez A. Hispanic culture, gay male culture, and AIDS: counseling implications. J Couns Dev. 1989;68(1):26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daniel-Ulloa J, Ulibarri M, Baquero B, Sleeth C, Harig H, Rhodes SD. Behavioral HIV prevention interventions among Latinas in the US: a systematic review of the evidence. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016;18(6):1498–1521. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0283-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Munoz-Laboy M, Garcia J, Wilson PA, Parker RG, Severson N. Heteronormativity and sexual partnering among bisexual Latino men. Arch Sex Behav. 2015;44(4):895–902. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0335-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Storey B. The cultural scripts for Latino gay immigrants. Focus (San Francisco, Calif.) 2000;15(7):5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Díaz RM. Latino gay men and HIV: culture, sexuality, and risk behavior. New York: Routledge; 1998. pp. 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryan CHD, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in White and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics. 2009;123(1):346–352. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bianchi FT, Reisen CA, Zea MC, Poppen PJ, Shedlin MG, Penha MM. The sexual experiences of Latino men who have sex with men who migrated to a gay epicentre in the USA. Cult Health Sex. 2007;9(5):505–18. doi: 10.1080/13691050701243547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cantú L. The sexuality of migration: border crossings and Mexican immigrant men. New York: New York University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melendez RM, Zepeda J, Samaniego R, Chakravarty D, Alaniz G. "La Familia" HIV prevention program: a focus on disclosure and family acceptance for Latino immigrant MSM to the USA. Salud Publica Mex. 2013;55:S491–S497. doi: 10.21149/spm.v55s4.5154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Acevedo V. Cultural competence in a group intervention designed for Latino patients living with HIV/AIDS. Health Soc Work. 2008;33(2):111–120. doi: 10.1093/hsw/33.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Resnicow K, Baranowski T, Ahluwalia JS, Braithwaite RL. Cultural sensitivity in public health: defined and demystified. Ethn Dis. 1999;9(1):10–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams JK, Wyatt GE, Resell J, Peterson J, Asuan-O'Brien A. Psychosocial Issues among gay- and non-gay-identifying HIV-seropositive African American and Latino MSM. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2004;10(3):268–286. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.3.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandfort TG, Melendez RM, Diaz RM. Gender nonconformity, homophobia, and mental distress in Latino gay and bisexual men. J Sex Res. 2007;44(2):181–9. doi: 10.1080/00224490701263819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Díaz RMAG. Social discrimination and health: the case of Latino gay men and HIV risk. The Policy Institute of the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Resnicow K, DiIorio C, Davis R. Communication perspectives on HIV/AIDS for the 21st century. Routledge; 2008. Culture and the development of HIV prevention and treatment programs; pp. 193–220. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Whittemore R. Culturally competent interventions for Hispanic adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. J Transcult Nurs. 2007;18(2):157–66. doi: 10.1177/1043659606298615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson LM, Scrimshaw SC, Fullilove MT, Fielding JE, Normand J. Culturally competent healthcare systems. a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(3 Suppl):68–79. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00657-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hoffman-Goetz L, Friedman DB. A systematic review of culturally sensitive cancer prevention resources for ethnic minorities. Ethn Dis. 2006;16(4):971–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griner D, Smith TB. Culturally adapted mental health intervention: a meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2006;43(4):531–548. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.43.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barrera M, Castro FG, Steiker LK. A critical analysis of approaches to the development of preventive interventions for subcultural groups. Am J Community Psychol. 2011;48(3):439–454. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9422-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, Szapocznik J. Rethinking the concept of acculturation: implications for theory and research. Am Psychol. 2010;65(4):237–251. doi: 10.1037/a0019330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oboler S. Hispanics? That's what they call us. In: Delgado J RS, editor. The Latino condition: A critical reader. New York University Press; New York: 1995. pp. 8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calderon J. "Hispanic" and "Latino": the viability of categories for panethnic unity. Lat Am Perspect. 1992;19(4):37–44. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hayes-Bautista DE. Identifying "Hispanic" populations: the influence of research methodology upon public policy. Am J Public Health. 1980;70(4):353–356. doi: 10.2105/ajph.70.4.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hayes-Bautista DE, Chapa J. Latino terminology: conceptual bases for standardized terminology. Am J Public Health. 1987;77(1):61–68. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG The Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Herbst JH, Kay LS, Passin WF, Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Marin BV. A systematic review and meta-analysis of behavioral interventions to reduce HIV risk behaviors of Hispanics in the United States and Puerto Rico. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(1):25–47. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Erausquin JT, Duan N, Grusky O, Swanson AN, Kerrone D, Rudy ET. Increasing the reach of HIV testing to young Latino MSM: results of a pilot study integrating outreach and services. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(3):756–765. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carballo-Diéguez A, Dolezal C, Leu CS, Nieves L, Díaz F, Decena C, Balan I. A randomized controlled trial to test an HlV-prevention intervention for Latino gay and bisexual men: lessons learned. AIDS Care. 2005;17(3):314–328. doi: 10.1080/09540120512331314303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Solorio R, Norton-Shelpuk P, Forehand M, Montano D, Stern J, Aguirre J, Martinez M. Tu Amigo Pepe: evaluation of a multi-media marketing campaign that targets young Latino immigrant MSM with HIV testing messages. AIDS Behav. 2016 doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1277-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Toro-Alfonso J, Varas-Díaz N, Andújar-Bello I. Evaluation of an HIV/AIDS prevention intervention targeting Latino gay men and men who have sex with men in Puerto Rico. AIDS Educ Prev. 2002;14(6):445–456. doi: 10.1521/aeap.14.8.445.24110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vega MY, Spieldenner AR, DeLeon D, Nieto BX, Stroman CA. SOMOS: evaluation of an HIV prevention intervention for Latino gay men. Health Educ Res. 2011;26(3):407–18. doi: 10.1093/her/cyq068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Galvan FH, Bluthenthal RN, Ani C, Bing EG. Increasing HIV testing among Latinos by bundling HIV testing with other tests. J Urban Health. 2006;83(5):849–859. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9072-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martínez-Donate AP, Zellner JA, Sanudo F, Fernandez-Cerdeno A, Hovell MF, Sipan CL, Engelberg M, Carrillo H. Hombres Sanos: evaluation of a social marketing campaign for heterosexually identified Latino men who have sex with men and women. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2532–40. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.179648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Somerville GG, Diaz S, Davis S, Coleman KD, Taveras S. Adapting the Popular Opinion Leader Intervention for Latino young migrant men who have sex with men. AIDS Educ Prev. 2006;18(SUPPL. A):137–148. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Diaz YE, Stevenson LY, Hauth AC, Brasfield TL, Kalichman SC, Smith JE, Andrew ME. HIV risk behavior reduction following intervention with key opinion leaders of population: an experimental analysis. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(2):168–71. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.2.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martínez-Donate AP, Zellner JA, Fernández-Cerdeño A, Sañudo F, Hovell MF, Sipan CL, Engelberg M, Ji M. Hombres Sanos: exposure and response to a social marketing HIV prevention campaign targeting heterosexually identified Latino men who have sex with men and women. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(5 SUPPL):124–136. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fernández Cerdeño A, Martinez-Donate AP, Zellner JA, Sanudo F, Carrillo H, Engelberg M, Sipan C, Hovell M. Marketing HIV prevention for heterosexually identified Latino men who have sex with men and women: the Hombres Sanos campaign. J Health Commun. 2012;17(6):641–58. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.635766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Solorio R, Norton-Shelpuk P. HIV prevention messages targeting young Latino immigrant MSM. AIDS Res Treat. 2014;2014:353092. doi: 10.1155/2014/353092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arciniega GM, Anderson TC, Tovar-Blank ZG, Tracey TJ. Toward a fuller conception of Machismo: development of a traditional Machismo and Caballerismo Scale. J Couns Psychol. 2008;55(1):19. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wallerstein N, Bernstein E. Empowerment education: Freire's ideas adapted to health education. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):379–394. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tajfel H, Turner JC. The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In: Worchel S, Austin WG, editors. Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Nelson-Hall; Chicago: 1986. pp. 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Abraído-Lanza AF, Echeverría SE, Flórez KR. Latino immigrants, acculturation, and health: promising new directions in research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2016;37:219–236. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032315-021545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Peterson JL, Marín G. Issues in the prevention of AIDS among Black and Hispanic men. Am Psychol. 1988;43(11):871–877. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.43.11.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lyles CM, Crepaz N, Herbst JH, Kay LS. Evidence–based HIV behavioral prevention from the perspective of the CDC's HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis Team. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2006;18(supp):21–31. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2006.18.supp.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morales ES. Contextual community prevention theory: building interventions with community agency collaboration. Am Psychol. 2009;64(8):805–816. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.64.8.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Singer M, Marzuach-Rodriquez L. Applying anthropology to the prevention of AIDS: the Latino Gay Men's Health Project. Hum Organ. 1996;55(2):141–148. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harper GW, Contreras R, Bangi A, Pedraza A. Collaborative process evaluation: enhancing community relevance and cultural appropriateness in HIV prevention. J Prev Interv Community. 2003;26(2):53–69. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fernandez MI, Jacobs RJ, Warren JC, Sanchez J, Bowen GS. Drug use and Hispanic men who have sex with men in South Florida: implications for intervention development. AIDS Educ Prev. 2009;21(5 Suppl):45–60. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The adaptation guide: adapting HIV behavior change interventions for gay and bisexual Latino and Black men. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vega MY. The CHANGE approach to capacity-building assistance. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2009;21(supplement b):137–151. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Centers for Disease Control. Behavioral interventions. [cited 2017 24 Aug];Effective interventions. 2017 Available from: https://effectiveinterventions.cdc.gov/en/HighImpactPrevention/Interventions.aspx.

- 71.Owczarzak J, Dickson-Gomez J. Provider perspectives on evidence-based HIV prevention interventions: barriers and facilitators to implementation. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011;25(3):171–179. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Alonzo J, Mann L, Tanner AE, Sun CJ, Painter TM, Freeman A, Reboussin BA, Song E, Rhodes SD. Reducing HIV risk among Hispanic/Latino men who have sex with men: qualitative analysis of behavior change intentions by participants in a small-group intervention. J AIDS Clin Res. 2016;7(5) doi: 10.4172/2155-6113.1000572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rhodes SD, Alonzo J, Mann L, Freeman A, Sun CJ, Garcia M, Painter TM. Enhancement of a locally developed HIV prevention intervention for Hispanic/Latino MSM: a partnership of community-based organizations, a university, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. AIDS Educ Prev. 2015;27(4):312–32. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2015.27.4.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wu E, El-Bassel N, Donald McVinney L, Fontaine YM, Hess L. Adaptation of a couple-based HIV intervention for methamphetamine-involved African American men who have sex with men. Open AIDS J. 2010;4:123–31. doi: 10.2174/1874613601004030123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martinez O, Wu E, Levine EC, Muñoz-Laboy M, Fernandez MI, Bass SB, Moya EM, Frasca T, Chavez-Baray S, Icard LD, Ovejero H, Carballo-Diéguez A, Rhodes SD. Integration of social, cultural, and biomedical strategies into an existing couple-based behavioral HIV/STI prevention intervention: voices of Latino male couples. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Martinez O, Wu E, Frasca T, Shultz AZ, Fernandez MI, Lopez Rios J, Ovejero H, Moya E, Chavez Baray S, Capote J, Manusov J, Anyamele CO, Lopez Matos J, Page JS, Carballo-Dieguez A, Sandfort TG. Adaptation of a couple-based HIV/STI prevention intervention for Latino men who have sex with men in New York City. Am J Mens Health. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1557988315579195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [November 19, 2016];Act against AIDS: Reasons. 2014 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/actagainstaids/campaigns/reasons/index.html.

- 78.Ramirez-Valles J. The quest for effective HIV-prevention interventions for Latino gay men. Am J Prev Med. 2007;32(4 Suppl):S34–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]