Abstract

The unusual feature of a t-butyl group is found in several marine-derived natural products including apratoxin A, a Sec61 inhibitor produced by the cyanobacterium Moorea bouillonii PNG 5-198. Here we determine that the apratoxin A t-butyl group is formed as pivaloyl acyl carrier protein (ACP) by AprA, the polyketide synthase (PKS) loading module of the apratoxin A biosynthetic pathway. AprA contains an inactive “pseudo” GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase domain (ΨGNAT) flanked by two methyltransferase domains (MT1 and MT2) that differ distinctly in sequence. Structural, biochemical, and precursor incorporation studies reveal that MT2 catalyzes unusually coupled decarboxylation and methylation reactions to transform dimethylmalonyl-ACP, the product of MT1, to pivaloyl-ACP. Further, pivaloyl-ACP synthesis is primed by the fatty acid synthase malonyl acyltransferase (FabD), which compensates for the ΨGNAT and provides the initial acyl-transfer step to form AprA malonyl-ACP. Additionally, images of AprA from negative stain electron microscopy reveal multiple conformations that may facilitate the individual catalytic steps of the multienzyme module.

INTRODUCTION

Marine organisms are rich sources of bioactive natural products1, 2, providing potential leads for new pharmaceuticals. Cyanobacteria produce a myriad of polyketide and non-ribosomal peptide secondary metabolites, which are synthesized by polyketide synthase (PKS) and non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) assembly lines using acyl-coenzyme A (CoA) or amino acid building blocks, respectively. Interestingly, a number of marine natural products contain t-butyl groups3–19, a chemical moiety that is relatively rare in nature20. Typically, t-butyl groups in natural products are encountered either as modified amino acids4–7, terpene-derived pendant chains on the D-ring of steroids8, or in PKS/NRPS-derived molecules3, 9–15 primarily found in the metabolomes of sponges or cyanobacteria.

Although t-butyl-containing natural products were first identified over 50 years ago21, only one route for t-butyl biosynthesis has been characterized5, 6, which involves a cobalamin-dependent radical S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) enzyme. Apratoxin A22 is a t-butyl containing cytotoxic Sec61 inhibitor (Figure 1a) produced by the marine cyanobacterium Moorea bouillonii PNG5-19822–24. However, the gene cluster for apratoxin A biosynthesis encodes no homolog of the cobalamin-dependent radical SAM enzymes previously implicated in t-butyl synthesis, which should occur in the initial steps of the pathway. Instead, synthesis of the t-butyl group in the form of pivalate is proposed to be carried out by AprA, an unusual polyketide loading module containing a GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase (GNAT)-like domain flanked by two methyltransferase domains (MT1 and MT2) (Figure 1b)22. GNAT-like domains typically decarboxylate CoA- or ACP-linked substrates25–27, and the founding member was also associated with the subsequent acyl transfer from CoA to an ACP domain during the initiation of curacin A biosynthesis25. However, we previously showed that the AprA GNAT is truncated and lacks catalytic residues essential for decarboxylation, and thus re-annotated it as a “pseudo” GNAT (ΨGNAT)28. AprA MT1 and MT2 share very low amino acid sequence identity, but MT2 is more than 30% identical to C-methyltransferases (C-MT) found in some PKS extension modules. PKS C-MTs of this type, for example the CurJ C-MT, methylate the α-position of β-keto intermediates during cycles of polyketide chain extension and modification29. Several variants of the marine natural product bryostatin also have a t-butyl substituent11, and a homolog of AprA (MT1-ΨGNAT-MT2-ACP) exists within BryX in the bryostatin pathway30.

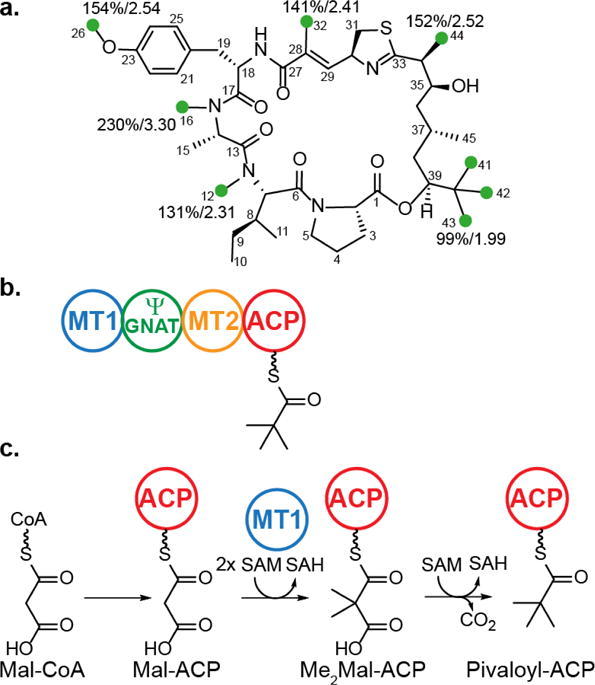

Figure 1.

Production of a t-butyl group by AprA. (a) Apratoxin A structure and distribution of SAM-derived methyl groups. Feeding studies demonstrate that the t-butyl group in apratoxin A is derived from SAM. Percent enrichment over natural abundance and fold-change of SAM-derived carbons (green circles) from [methyl-13C]methionine-fed cultures of M. bouillonii PNG5-198 relative to native abundance apratoxin A are displayed. (b) Cartoon representing AprA domains, which are proposed to produce pivaloyl-ACP: methyltransferase 1 (MT1), pseudo GCN5-related N-acetyltransferase (ΨGNAT), methyltransferase 2 (MT2), ACP. (c) Reactions needed to produce pivaloyl-ACP. The conversion of malonyl-ACP to Me2Mal-ACP has been characterized28. The identities of the enzymes that catalyze acyltransfer from Mal-CoA to ACP, decarboxylation of Me2Mal-ACP, and the third methylation reaction are addressed in this study.

Previously, we characterized two initial steps in the biosynthesis of the apratoxin A starter unit, demonstrating that AprA MT1 is a mononuclear iron-dependent methyltransferase that forms dimethylmalonyl-ACP (Me2Mal-ACP) from malonyl-ACP (Mal-ACP) and two equivalents of SAM (Figure 1c)28. Thus, conversion of Me2Mal-ACP to the pivaloyl starter unit requires a decarboxylase and a methyltransferase. The acyltransferase that initiates apratoxin A biosynthesis by forming Mal-ACP (Figure 1c) also remains to be identified.

To determine whether AprA can form pivaloyl-ACP, we characterized the catalytic activity of the MT2, solved a crystal structure of the ΨGNAT-MT2 didomain, and conducted stable-isotope labeled feeding experiments with live cultures of M. bouillonii PNG5-198. MT2 is a remarkable bifunctional enzyme that catalyzes the coordinated decarboxylation and methylation of Me2Mal-ACP to produce pivaloyl-ACP. As no AprA catalytic domain can perform the missing malonyl-acyltransfer step to initiate the pathway, we determined that the M. bouillonii fatty acid synthase malonyl-acyltransferase, FabD, is an efficient catalyst for the formation of Mal-ACP from Mal-CoA, indicating crosstalk between primary and secondary metabolic pathways in M. bouillonii. Furthermore, a model of the AprA full module based on the crystal structures of the AprA MT1-ΨGNAT28 and ΨGNAT-MT2 didomains was validated by negative-stain electron microscopy (EM) of AprA ΔACP in solution, revealing a flexible overall architecture that may facilitate the individual catalytic steps.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Origin of the t-butyl group: SAM-derived methyl groups incorporated into apratoxin A

In order to examine the incorporation of methyl groups from SAM into the t-butyl group of apratoxin A in vivo, [methyl-13C]methionine, the immediate metabolic precursor and methyl donor to SAM, was provided to M. bouillonii PNG5-198 cultures. Apratoxin A was subsequently purified from these cultures, and incorporation of 13C into specific carbon atoms in the molecule was monitored by 13C NMR and compared with purified apratoxin A grown without label. Carbons 41–43, comprising the t-butyl group in apratoxin A, were enriched by 99.0%, or 1.99-fold in the sample supplemented with [methyl-13C]methionine relative to an unlabeled sample; 13C NMR signals not deriving from the SAM methyl group were essentially unchanged (Figure 1a, Table 1.) Additionally, in order to support the idea that methylmalonyl-CoA does not provide one of the methyl groups in the t-butyl moiety, we provided the producing culture with [1-13C]propionate, a precursor to methylmalonyl-CoA (MeMal-CoA) in bacterial PKS biosynthesis. We observed only natural-abundance incorporation at C39, the predicted position of possible incorporation into apratoxin A (Supporting Figure 1, Supporting Tables 1 and 2), indicating that Mal-ACP is the preferred AprA substrate. This is consistent with our previous determination that Mal-ACP is the substrate for AprA MT1, which performs two methylations to produce Me2Mal-ACP (Figure 1c)28.

Table 1.

Enrichment of apratoxin A by culture of M. bouillonii PNG 5-198 supplemented with [methyl-13C]methionine. Final enrichment values are derived by normalization of enriched 13C-NMR resonances to five carbon atoms. Calculation steps are detailed in Methods section. SAM-derived enrichment values are in bold and italicized in column 21 and 22.

| Column # → | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| C# | Biosynthetic source |

ppm | Integral of unlabeled resonance |

Normalization factor using: | Integral of enriched resonance |

Normalized integral of enriched sample using: |

Enrichment compared to: | Average % enrichment |

Fold change |

||||||||||||

| C7 | C13 | C20 | C30 | C37 | C7 | C13 | C20 | C30 | C37 | C7 | C13 | C20 | C30 | C37 | |||||||

| 1 | Pro | 172.8 | 42.7 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 45.9 | 37.2 | 40.2 | 30.6 | 36.2 | 40.1 | 23.3 | 14.1 | 50.0 | 26.7 | 14.5 | 25.7 | 1.26 |

| 2 | Pro | 59.9 | 112.6 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 79.2 | 98.1 | 106.1 | 80.7 | 95.5 | 105.7 | −19.3 | −25.3 | −1.9 | −17.1 | −25.1 | −17.7 | 0.82 |

| 3 | Pro | 29.5 | 119.5 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 126.5 | 104.1 | 112.6 | 85.6 | 101.3 | 112.2 | 21.5 | 12.4 | 47.7 | 24.8 | 12.8 | 23.8 | 1.24 |

| 4 | Pro | 25.8 | 91.9 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 81.7 | 80.1 | 86.6 | 65.9 | 78.0 | 86.3 | 1.9 | −5.7 | 24.0 | 4.8 | −5.4 | 3.9 | 1.04 |

| 5 | Pro | 47.8 | 133.9 | 1.3 | 2.2 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 88.1 | 116.7 | 126.2 | 96.0 | 113.6 | 125.7 | −24.5 | −30.2 | −8.2 | −22.5 | −30.0 | −23.1 | 0.77 |

| 6 | Ile | 170.8 | 37.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 51.4 | 32.6 | 35.2 | 26.8 | 31.7 | 35.1 | 57.9 | 46.1 | 92.1 | 62.3 | 46.6 | 61.0 | 1.61 |

| 7 | Ile | 56.8 | 104.0 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 90.7 | 90.7 | 98.0 | 74.6 | 88.2 | 97.7 | 0.0 | −7.5 | 21.6 | 2.8 | −7.2 | 1.9 | 1.02 |

| 8 | Ile | 31.9 | 82.9 | 0.8 | 1.4 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 68.2 | 72.3 | 78.1 | 59.4 | 70.3 | 77.9 | −5.7 | −12.7 | 14.7 | −3.1 | −12.4 | −3.8 | 0.96 |

| 9 | Ile | 24.8 | 93.7 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 66.0 | 81.7 | 88.3 | 67.2 | 79.5 | 88.0 | −19.2 | −25.3 | −1.7 | −17.0 | −25.0 | −17.6 | 0.82 |

| 10 | Ile | 9.2 | 124.2 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 83.4 | 108.3 | 117.0 | 89.0 | 105.4 | 116.6 | −23.0 | −28.8 | −6.4 | −20.9 | −28.5 | −21.5 | 0.79 |

| 11 | Ile | 14.2 | 145.1 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 86.1 | 126.5 | 136.7 | 104.0 | 123.1 | 136.3 | −31.9 | −37.0 | −17.2 | −30.1 | −36.8 | −30.6 | 0.69 |

| 12 | SAM | 30.7 | 89.0 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 175.7 | 77.6 | 83.8 | 63.8 | 75.5 | 83.6 | 126.5 | 109.6 | 175.5 | 132.8 | 110.3 | 130.9 | 2.31 |

| 13 | Ala | 170.2 | 61.1 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 57.6 | 53.3 | 57.6 | 43.8 | 51.8 | 57.4 | 8.1 | 0.0 | 31.5 | 11.1 | 0.3 | 10.2 | 1.10 |

| 14 | Ala | 60.9 | 76.9 | 0.7 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 90.6 | 67.0 | 72.5 | 55.1 | 65.2 | 72.2 | 35.1 | 25.0 | 64.3 | 38.9 | 25.5 | 37.8 | 1.38 |

| 15 | Ala | 14.1 | 62.4 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 70.6 | 54.4 | 58.8 | 44.7 | 52.9 | 58.6 | 29.9 | 20.1 | 57.9 | 33.5 | 20.6 | 32.4 | 1.32 |

| 16 | SAM | 36.9 | 38.8 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 109.7 | 33.8 | 36.6 | 27.8 | 32.9 | 36.4 | 224.3 | 200.0 | 294.4 | 233.2 | 201.0 | 230.6 | 3.31 |

| 17 | Tyr | 170.6 | 58.8 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 58.5 | 51.3 | 55.4 | 42.2 | 49.9 | 55.2 | 14.1 | 5.6 | 38.8 | 17.3 | 5.9 | 16.3 | 1.16 |

| 18 | Tyr | 50.6 | 97.8 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.3 | 13.8 | 85.2 | 92.1 | 70.1 | 82.9 | 91.8 | −83.8 | −85.0 | −80.3 | −83.4 | −85.0 | −83.5 | 0.17 |

| 19 | Tyr | 37.3 | 116.5 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 95.5 | 101.6 | 109.8 | 83.5 | 98.8 | 109.4 | −6.0 | −13.0 | 14.4 | −3.4 | −12.7 | −4.1 | 0.96 |

| 20 | Tyr | 128.4 | 100.6 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 1.4 | s72.1 | 87.7 | 94.8 | 72.1 | 85.3 | 94.5 | −17.8 | −23.9 | 0.0 | −15.5 | −23.7 | −16.2 | 0.84 |

| 21/25 | Tyr | 130.8 | 293.1 | 2.8 | 4.8 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 4.0 | 237.2 | 255.4 | 276.1 | 210.0 | 248.6 | 275.2 | −7.2 | −14.1 | 12.9 | −4.6 | −13.8 | −5.4 | 0.95 |

| 22/24 | Tyr | 114.0 | 254.6 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 2.5 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 225.7 | 221.9 | 239.9 | 182.5 | 215.9 | 239.0 | 1.7 | −5.9 | 23.7 | 4.5 | −5.6 | 3.7 | 1.04 |

| 23 | Tyr | 158.8 | 43.0 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 46.0 | 37.5 | 40.5 | 30.8 | 36.5 | 40.4 | 22.6 | 13.5 | 49.1 | 26.0 | 13.8 | 25.0 | 1.25 |

| 26 | SAM | 55.4 | 124.2 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.7 | 270.1 | 108.2 | 117.0 | 89.0 | 105.3 | 116.6 | 149.6 | 130.9 | 203.5 | 156.5 | 131.7 | 154.5 | 2.55 |

| 27 | Acetate | 169.7 | 44.5 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 50.1 | 38.8 | 41.9 | 31.9 | 37.7 | 41.7 | 29.2 | 19.6 | 57.2 | 32.8 | 20.0 | 31.8 | 1.32 |

| 28 | Acetate | 130.6 | 42.1 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 0.4 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 56.6 | 36.7 | 39.6 | 30.1 | 35.7 | 39.5 | 54.4 | 42.8 | 87.7 | 58.7 | 43.3 | 57.4 | 1.57 |

| 29 | Cys | 136.4 | 90.2 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 98.7 | 78.6 | 85.0 | 64.6 | 76.5 | 84.7 | 25.6 | 16.2 | 52.7 | 29.1 | 16.6 | 28.0 | 1.28 |

| 30 | Cys | 72.6 | 111.7 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 94.8 | 97.4 | 105.3 | 80.1 | 94.8 | 104.9 | −2.7 | −10.0 | 18.3 | 0.0 | −9.7 | −0.8 | 0.99 |

| 31 | Cys | 37.7 | 71.5 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 37.6 | 62.3 | 67.4 | 51.3 | 60.7 | 67.2 | −39.7 | −44.2 | −26.7 | −38.0 | −44.0 | −38.5 | 0.62 |

| 32 | SAM | 13.5 | 81.2 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 167.6 | 70.8 | 76.5 | 58.2 | 68.9 | 76.2 | 136.8 | 119.1 | 188.0 | 143.4 | 119.8 | 141.4 | 2.41 |

| 33 | Acetate | 177.6 | 57.3 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 65.3 | 50.0 | 54.0 | 41.1 | 48.6 | 53.8 | 30.8 | 21.0 | 59.0 | 34.4 | 21.4 | 33.3 | 1.33 |

| 34 | Acetate | 49.3 | 76.3 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 84.9 | 66.5 | 71.9 | 54.7 | 64.7 | 71.7 | 27.6 | 18.0 | 55.2 | 31.1 | 18.5 | 30.1 | 1.30 |

| 35 | Acetate | 71.8 | 116.2 | 1.1 | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 122.4 | 101.3 | 109.5 | 83.3 | 98.6 | 109.1 | 20.8 | 11.8 | 46.9 | 24.1 | 12.1 | 23.2 | 1.23 |

| 36 | Acetate | 38.3 | 94.7 | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 104.0 | 82.6 | 89.3 | 67.9 | 80.3 | 89.0 | 25.9 | 16.5 | 53.1 | 29.4 | 16.9 | 28.4 | 1.28 |

| 37 | Acetate | 24.4 | 72.6 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 68.4 | 63.3 | 68.4 | 52.0 | 61.6 | 68.2 | 8.0 | −0.1 | 31.4 | 11.0 | 0.3 | 10.1 | 1.10 |

| 38 | Acetate | 37.8 | 111.1 | 1.1 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 129.8 | 96.8 | 104.7 | 79.6 | 94.2 | 104.3 | 34.0 | 24.0 | 63.0 | 37.7 | 24.4 | 36.6 | 1.37 |

| 39 | Acetate | 77.4 | N.P.* | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 40 | Acetate | 35.0 | 93.4 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 94.2 | 81.4 | 88.0 | 66.9 | 79.2 | 87.7 | 15.8 | 7.1 | 40.8 | 19.0 | 7.5 | 18.0 | 1.18 |

| 41–43 | SAM | 26.2 | 387.6 | 3.7 | 6.3 | 3.9 | 3.5 | 5.3 | 659.6 | 337.8 | 365.2 | 277.8 | 328.7 | 363.9 | 95.2 | 80.6 | 137.4 | 100.6 | 81.2 | 99.0 | 1.99 |

| 44 | SAM | 16.8 | 94.1 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 1.3 | 203.0 | 82.0 | 88.6 | 67.4 | 79.8 | 88.3 | 147.5 | 129.0 | 201.0 | 154.4 | 129.8 | 152.3 | 2.52 |

| 45 | Acetate | 20.0 | 109.2 | 1.0 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 70.7 | 95.2 | 102.9 | 78.3 | 92.6 | 102.5 | −25.7 | −31.2 | −9.6 | −23.6 | −31.0 | −24.2 | 0.76 |

N.P. = No quantitation due to CDCl3 peak overlap

AprA MT2 is a dual function decarboxylase and methyltransferase

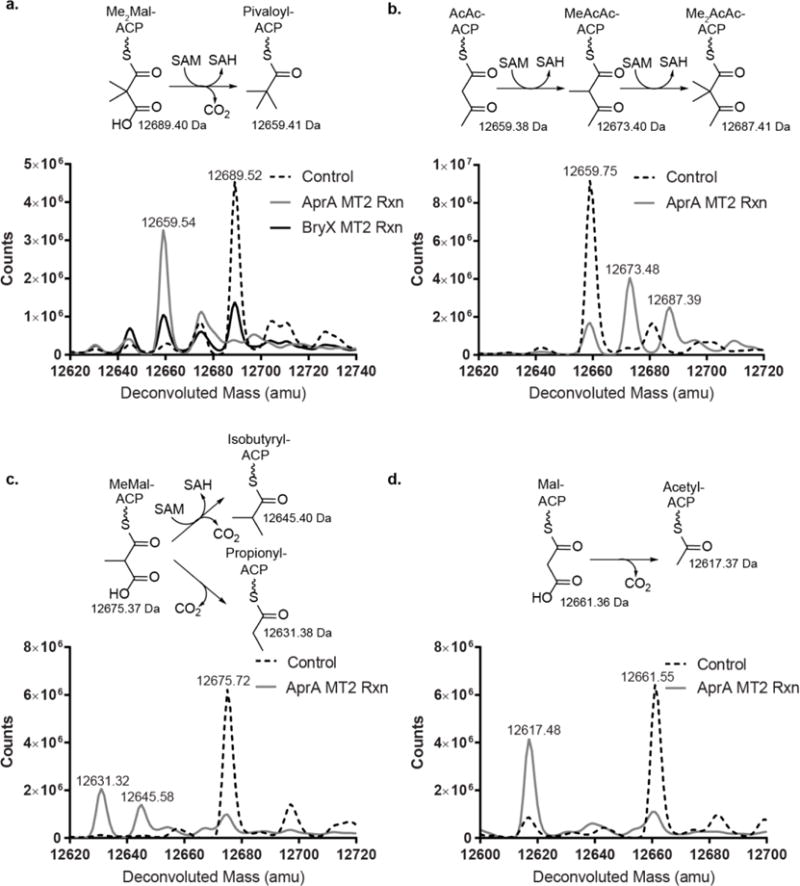

To test the activity of AprA MT2, we incubated it with the Me2Mal-ACP product of AprA MT1 in the presence of methyl donor SAM, and analyzed the reaction mixture by intact protein mass spectrometry. Unexpectedly, we observed the production of pivaloyl-ACP, indicating that MT2 is a bifunctional enzyme, carrying out both decarboxylation and methylation (Figure 2a, Supporting Figure 2a). To verify the generality of this bifunctional activity, we produced the BryX MT2 domain (40% sequence identity to AprA MT2) from a homologous module28 in the bryostatin biosynthetic pathway30. BryX MT2 also produced pivaloyl-ACP (Figure 2a, Supporting Figure 2b), suggesting that BryX is the t-butyl-producing module in bryostatin biosynthesis.

Figure 2.

Catalytic activity of MT2. Intact protein mass spectra are shown for AprA ACP species. (a) AprA MT2 and BryX MT2 reactions on Me2Mal-ACP. AprA MT2 reactions on (b) AcAc-ACP, (c) MeMal-ACP, (d) Mal-ACP. Calculated masses are indicated by the chemical structures, and observed masses on the mass spectra. Negative controls (no enzyme) are indicated in dotted lines.

Precedent for dual decarboxylation/methyl transfer activity exists in enzymes that function in epigenetic regulation (DNA cytosine-C5 (C5)-methyltransferase)31, 32 and corrin biosynthesis (CbiT and CobL)33, 34. Like AprA MT2, CbiT and CobL catalyze coordinated decarboxylation and methylation reactions, in which decarboxylation activates a distal carbon for methyl transfer34, whereas DNA C5-methyltransferase performs decarboxylation independent of methyltransfer31. AprA MT2, DNA C5-methyltransferase, CobL and CbiT are members of the highly divergent class I methyltransferase superfamily, whose members are identified by six conserved motifs in the nucleotide binding core35. AprA MT2 is a distant relative without significant sequence identity to DNA C5-methyltransferase, CbiT or CobL beyond the conserved motifs.

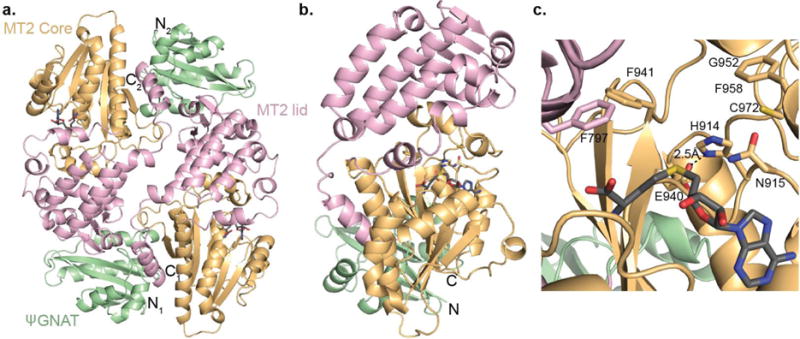

Crystal structure of AprA ΨGNAT-MT2

To understand how AprA MT2 mediates its remarkable dual activities, we solved a 2.25-Å crystal structure of the ΨGNAT-MT2 didomain in complex with S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) (Figure 3, Supporting Figure 3a, Supporting Table 3). The AprA ΨGNAT-MT2 didomain is dimeric in crystals and in solution, as determined by size exclusion chromatography. In the crystals, the head-to-tail dimer interface includes a disulfide bond between the Cys651 residues of the MT2 domains. A C651S amino acid substitution also yielded dimeric protein, indicating that the ΨGNAT-MT2 dimer is not a disulfide-dependent artifact of the aerobic lab environment.

Figure 3.

AprA ΨGNAT-MT2 structure and active site. (a) AprA ΨGNAT-MT2 head-to-tail dimer colored by structural region (ΨGNAT, green; MT2 lid, pink; MT2 core, orange). SAH is shown in stick form with atomic coloring (C, black; O, red; N, blue; S, yellow). N- and C-termini are labeled for each monomer. (b) AprA ΨGNAT-MT2 monomer colored by structural region as in a. (c) AprA MT2 active site colored as in a. Amino acids subjected to mutagenesis are shown in sticks.

The ΨGNAT is truncated relative to functional GNAT homologs25, 27 and is connected to MT2 by a 12 residue linker, validating our previous report that the ΨGNAT (truncated GNAT) within the AprA MT1-ΨGNAT structure is the full domain28. AprA MT2 is similar to the cyanobacterial C-MT29 from the CurJ extension module of curacin A biosynthesis (33% sequence identity, RMSD of 1.3 Å for 273 total Cα atoms, Supporting Figure 4) and to the fungal citrinin PKS C-MT36 (22% sequence identity, RMSD of 2.1 Å for 261 total Cα atoms), including an extremely long N-terminal helix, a helical lid, and a SAM-binding core with a helical insertion between β-strands 5 and 6. The SAM-binding core of AprA MT2 and CurJ C-MT are virtually identical (RMSD 0.48 Å for 103 core Cα atoms), but their respective lid domains are positioned slightly differently (Supporting Figure 3b).

Active site architecture

PKS C-MTs, such as CurJ C-MT29 and those in modules AprG and AprI in the apratoxin A pathway22, catalyze α-methylation of the respective β-keto intermediates, the product of the ketosynthase (KS) extension reaction, but do not act on the carboxylate substrate Mal-ACP29, 37, 38. To gain insight into the bifunctional activity of AprA MT2, we compared the active sites of AprA MT2 and CurJ C-MT29 (Figure 3c and Supporting Figure 3c), both of which are produced by Moorea species. In both structures, SAH sits in a cleft between the lid and core domains with strong electron density for the adenosine moiety and rather weak density for the homocysteine portion (Supporting Figure 3a), indicating that the bound SAH may not be captured in a catalytic conformation. The cleft between the lid and the core in AprA MT2 is much shallower than in CurJ C-MT, due to the bulky Phe941 and Trp759 side chains, correlating with the shorter Me2Mal-ACP substrate of AprA MT2 vs. the extended β-keto intermediate methylated by CurJ C-MT29. The His-Glu dyad that is critical for methylation by PKS C-MTs29, 36 is conserved in MT2 (His914, Glu940) (Supporting Figure 4). However, several nearby amino acids differ in AprA MT2 and CurJ C-MT. Near the SAH, Phe797 replaces a conserved Tyr that was hypothesized to facilitate methylation by the CurJ C-MT through interactions with the SAM sulfonium (Supporting Figure 3c). Most interestingly, the catalytic His resides in a nearly invariant His-Ala-Thr (HAT) motif in PKS extension-module C-MTs (Supporting Figures 3c and 4), while in AprA MT2, the analogous sequence at the catalytic His914 is His-Asn-Thr.

Other differences exist in a small pocket behind the MT2 His-Glu dyad. In AprA MT2, Gly952, Phe958 and Cys972 replace, respectively, Phe, Trp and Pro side chains, which are conserved in extension module C-MTs (Supporting Information Figure 4). Based on their sequences (Supporting Information Figure 4), identical pockets exist in AprA MT2 and BryX MT2, which also carries out dual decarboxylation and methylation.

AprA MT2 is active on multiple substrates

Given the similarity of the AprA MT2 and CurJ C-MT active sites (Supporting Information Figure 3c), we tested MT2 activity on acetoacetyl-ACP (AcAc-ACP), a substrate mimic for CurJ C-MT29. Similar to the PKS C-MT, AprA MT2 methylated AcAc-ACP to yield dimethyl-acetoacetyl-ACP (Figure 2b). Dimethylation by PKS C-MTs has been reported previously38–40, although no sequence motifs are apparent that delineate the ability to catalyze one or two methylation reactions.

Given the promiscuity of AprA MT2 for both carboxylated and non-carboxylated acyl groups, we tested MT2 activity on other potential substrates. Coordinated decarboxylation and methylation activity also occurred with a MeMal-ACP substrate to produce isobutyryl-ACP (Figure 2c). Interestingly, this corresponds with the natural occurrence of an isobutyryl group in apratoxin C41. However, product formation was approximately 4-fold slower with MeMal-ACP than with Me2Mal-ACP, and the reaction with MeMal-ACP also produced significant quantities of the propionyl-ACP product of decarboxylation only. The slower turnover and shunt product indicate that MT2 is selective for Me2Mal-ACP (Figure 2c). We also tested Mal-ACP as an AprA MT2 substrate, but, unlike the MT2 activity with Me2Mal-ACP or MeMal-ACP, we detected only the decarboxylation product acetyl-ACP (Figure 2d). Mal-ACP decarboxylation occurred approximately 50-fold slower than the consumption of Me2Mal-ACP, further demonstrating MT2 selectivity for the dimethylated acyl group. Interestingly, Me2Mal-, MeMal-, and Mal-ACP decarboxylation required SAM; neither SAH nor sinefungin, a stable SAM analog, supported decarboxylation activity. However, SAM was not consumed during the decarboxylation reaction (see below; and Supporting Information Figures 2c, 2d).

Reaction mechanism for AprA MT2

MT2-catalyzed methyl transfer was tightly coupled to decarboxylation, as the enzyme had no activity with the decarboxylated intermediates isobutyryl- and propionyl-ACP. The preferred and presumed native substrate was Me2Mal-ACP, which was rapidly and exclusively converted to pivaloyl-ACP (Figure 2a). In contrast, reactions on non-native substrates uncoupled decarboxylation and methylation. Substrate MeMal-ACP yielded significant quantities of the propionyl-ACP shunt product of decarboxylation only (Figure 2c), and substrate Mal-ACP yielded only the decarboxylated product acetyl-ACP at a significantly slower rate (Figure 2d).

Coupling of decarboxylation and methylation requires that the reactions occur in one active site. We used site directed mutagenesis to disrupt the conserved His-Glu dyad that is responsible for methylation in PKS C-MTs29, 36, which are AprA MT2 homologs. Product formation was monitored using the MS-based phosphopantetheine (Ppant) ejection assay, where the Ppant fragment is dissociated from the ACP phosphoserine linkage during ionization and used for quantification based on relative abundance of Ppant species42, 43. Activity was evaluated with substrates for coupled decarboxylation and methylation (Me2Mal-ACP and MeMal-ACP), decarboxylation only (Mal-ACP), and methylation only (AcAc-ACP) (Figures 4a, 4b, 4c and Supporting Information Figures 5a, 5b, 5c, 5d).

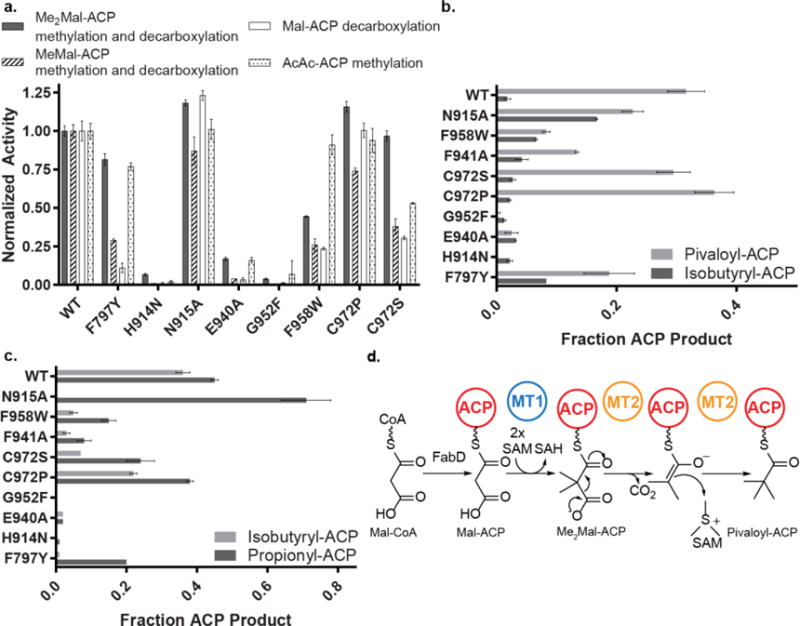

Figure 4.

Probing AprA MT2 activity via site-directed mutagenesis. (a) Relative activities for reactions of AprA MT2 with Me2Mal-ACP, MeMal-ACP, Mal-ACP, and AcAc-ACP. Data represent total product formed. Product ratios for data in (a) from coupled (decarboxylation + methylation) and uncoupled (decarboxylation only) reactions with (b) Me2Mal-ACP (pivaloyl-ACP and isobutyryl-ACP), (c) MeMal-ACP (isobutyryl-ACP and propionyl-ACP). All reaction species were quantified using the Ppant ejection assay42, 43. Error bars, in some cases too small to be visible, represent triplicate experiments. (d) Proposed mechanism for the coupled methylation and decarboxylation sequence to convert Mal-CoA into the pivaloyl-ACP starting unit of apratoxin A biosynthesis.

The His-Glu dyad is essential for both decarboxylation and methylation by MT2. The H914N and E940A variants had no activity on any substrate, including Mal-ACP, which undergoes decarboxylation only, demonstrating that both the decarboxylation and methylation reactions occur in one active site (Figures 3c and 4a). We hypothesize that during decarboxylation, His914 accepts a proton and promotes decarboxylation by stabilizing the developing negative charge at the thioester and the resulting enolate (Figure 4d). Methyl donation from SAM is likely simultaneous with collapse of the enolate to form pivaloyl-ACP (Figure 4d).

As noted above, product formation was abrogated in the absence of SAM, which is consistent with the absolute requirement for this cofactor to initiate decarboxylation, although it is not consumed in the reaction (Supporting Information Figures 2c, 2d). Affinity measurements for substrates in the presence of SAM, SAH, and sinefungin in other methyltransferases44, 45 indicated that interactions between the active site and the sulfonium, which do not exist in our SAH-bound ΨGNAT-MT2 crystal structure, may allow this class of enzyme to organize the active site for productive catalysis only when SAM is present by “sensing” small differences that occur upon methyl donor binding. Alternatively, electronic effects of the SAM sulfonium ion, which are not present in SAH or sinefungin, may facilitate the decarboxylation reaction.

In order to understand AprA MT2 decarboxylation compared to its non-decarboxylating PKS C-MT homologs, such as CurJ C-MT, we introduced additional “CurJ like” amino acid substitutions into the AprA MT2 active site. When Asn915, the amino acid following the catalytic His914, is substituted with Ala, which is conserved in the extension-module C-MT HAT motif, we observed near wild type or enhanced turnover (Figure 3c, 4a and Supporting Information Figure 4). However, the N915A substitution decouples decarboxylation and methylation on Me2Mal-ACP (Figure 4b) and MeMal-ACP (Figure 4c), as indicated by the increase in production of the respective isobutyryl-ACP and propionyl-ACP shunt products resulting from decarboxylation only.

Decoupling of decarboxylation and methylation of Me2Mal-ACP and MeMal-ACP also occurred when MT2 Phe797 was substituted with Tyr (Figures 4b, 4c), which is conserved in nearly all extension-module C-MTs (Supporting Information Figures 3c, 4). Notably, the F797Y variant nearly eliminated decarboxylation activity on Mal-ACP, but had little effect on methylation of AcAc-ACP (Figure 4a). We next examined the small pocket behind the His-Glu dyad, which is unique to the bifunctional AprA MT2 and BryX MT2. An F958W substitution also decoupled decarboxylation and methylation of Me2Mal-ACP (Figure 4b) and MeMal-ACP (Figure 4c) and, like the F797Y substitution, had little effect on methylation of AcAc-ACP (Figure 4a). Occluding the small pocket with a G952F substitution eliminated all activities, whereas substitutions at Cys972 within the pocket (C972P, C972S) had modest effects.

As small amino acid substitutions to the AprA MT2 active site (N915A, F979Y, F958W) and minor substrate alterations (e.g. MeMal-ACP vs. Me2Mal-ACP) decoupled decarboxylation and methylation, we conclude that AprA MT2 evolved from a methylation-only enzyme to promote formation of pivaloyl-ACP. Given the weak electron density for SAH in the AprA MT2 crystal structure (Supporting Information Figure 3a), several amino acids are likely not in their final catalytic positions. Therefore, we hypothesize that once in catalytically competent positions, amino acids that couple methylation and decarboxylation (Asn915, Phe797, Phe958 and perhaps others) either position the carboxylated substrates for catalysis or stabilize the proposed enolate intermediate (Figure 4d). Stabilization of the enolate and substrate positioning adjacent to the SAM methyl donor are essential as the decarboxylated intermediate could readily collapse to the shunt product by accepting a proton without methyl transfer.

FabD provides the initial acyl transfer step

As neither AprA MT1-ΨGNAT nor ΨGNAT performed the malonyl transfer reaction (Mal-CoA to Mal-ACP) to initiate apratoxin A biosynthesis28, we tested AprA MT2 for malonyl acyltransferase activity, but detected no transfer of malonyl from CoA to AprA ACP (Supporting Information Figure 6a). Additionally, the apr gene cluster encodes no other candidate acyltransferase for the initiation reaction.

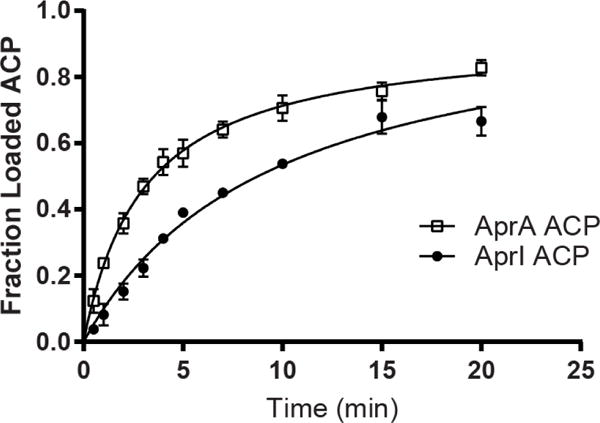

Previous studies showed that the malonyl-acyltransferase (FabD) of fatty acid biosynthesis in the producing organism can compensate for the lack of an acyltransferase in the initiation module of some PKS systems46, 47. Therefore, we identified fabD in the M. bouillonii PNG5-198 genome48, cloned the gene, and produced recombinant FabD in E. coli. Incubation of FabD with AprA holo-ACP led to rapid formation of Mal-ACP (Figure 5, Supporting Information Figure 6b). Surprisingly, AprA ACP shares only 20% sequence identity with the M. bouillonii fatty acid synthase (FAS) ACP (AcpP). Additionally, ACPs associated with GNAT-containing loading modules, such as AprA, clade separately from both PKS extension-module ACPs and FAS ACPs (Supporting Information Figure 6c) and can be distinguished by a phenylalanine motif (Supporting Information Figure 6d). Therefore, we tested the specificity of FabD for the AprA loading-module ACP relative to extension-module ACPs in the apratoxin A pathway using the AprI ACP (23% identity to AprA ACP). AprI is a typical PKS extension module with an embedded acyltransferase. FabD catalyzed malonyl transfer to AprI ACP, but was twofold faster for malonyl transfer to AprA ACP (Figure 5). This is consistent with a previous report that FabD can compensate for catalytically inactive acyltransferase domains in a modular PKS49. We propose that M. bouillonii exploits primary metabolism by using FabD from fatty acid biosynthesis to initiate apratoxin A biosynthesis by providing the malonyl starter unit to the AprA ACP.

Figure 5.

FabD malonyl acyltransfer activity. Malonyl is transferred from CoA to ACP by M. bouillonii PNG5-198 FabD. Reaction was monitored using the Ppant ejection assay42, 43. Error bars represent triplicate experiments and, in some cases, are too small to be visible.

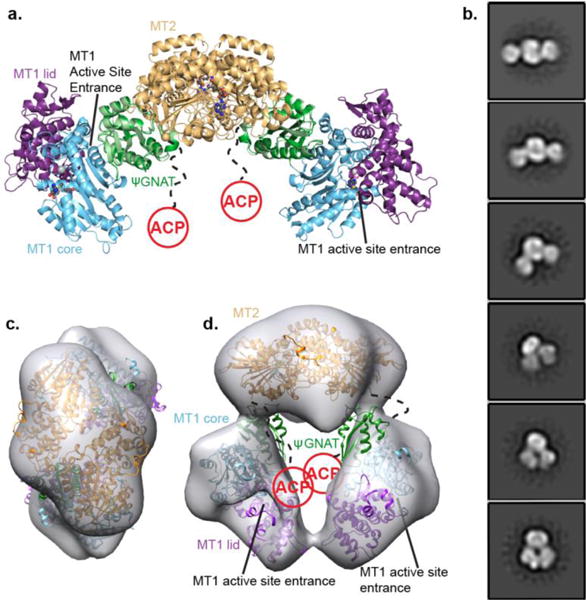

Modeling and EM visualization of the AprA module

The crystal structures of the AprA MT1-ΨGNAT28 and ΨGNAT-MT2 fragments provided a unique opportunity to model the overall architecture of AprA (MT1-ΨGNAT-MT2) by superimposing the ΨGNAT domains of the two structures (RMSD of 1.0 Å for 107 Cα). The composite model (Figure 6a) lacks steric clashes as MT1 and MT2 contact opposite faces of the ΨGNAT. The MT2 dimer sits at the center of the curved AprA model with the MT1 domains on opposite sides. The ACP is missing in our model, but is connected to the C-terminus of the MT2 dimer via a 44 amino acid linker.

Figure 6.

Architecture of the AprA module. (a) AprA model based on crystal structures of MT1-ΨGNAT and ΨGNAT-MT2 fragments, colored by structural region (MT1 lid, purple; MT1 core, blue; ΨGNAT, green; MT2 dimer, orange). SAM and SAH are shown in spheres with atomic coloring (gray C). In the MT1 active site, Mn2+ is shown in light gray spheres and malonate in sticks (pink C). The model was created by superposition of the ΨGNAT domains of the two crystal structures (RMSD 1.0 for 107 Cα αtoms). The 44 amino acids linking MT2 and ACP are depicted in a dashed line. (b) Selected negative stain class averages of AprA (ΔACP) showing the central MT2 dimer and ΨGNAT-MT2 wings. Linear and bent states of AprA are observed in these images. (c) 3D reconstruction of AprA in the bent conformation (gray), representing ~30% of the particles (top down view). Docked crystal structures of AprA MT1-ΨGNAT and AprA MT2 are colored as in (a). (d) side view of 3D reconstruction with docked AprA domains.

We tested the AprA model using electron microscopy to visualize intact AprA ΔACP (Figure 6b and Supporting Information Figures 7a, 7b). Consistent with the crystal structures and the model, the negative-stain 2D class averages revealed a structure with overall twofold-symmetry. A large central lobe, consistent with the MT2 dimer (96 kDa), is flanked by two smaller lobes, each consistent with monomeric MT1-ΨGNAT (75 kDa) (Figure 6b). MT1 is insoluble without ΨGNAT28 whereas MT2 is a stable dimer, and accordingly the flanking MT1- ΨGNAT has few contacts with MT2, suggesting that the ΨGNAT is associated with MT1. The overall architecture of the AprA model is similar to classes corresponding to ~30% of total particles, where the two MT1-ΨGNAT lobes are linear relative to MT2. However, a similar number of particles belong to classes with a bent arch shape where the MT1-ΨGNAT lobes appear repositioned relative to the MT2 dimer (Figure 6b).

The bent-state class averages were more uniform and of higher quality than the linear-state classes. Thus, we extracted particles of the bent state and obtained a 3D reconstruction to test whether the size and shape of the EM density was consistent with the crystal structures (Figures 6c and 6d). The MT2 dimer crystal structure docks nearly perfectly into the EM density, and the size and shape of the MT1-ΨGNAT correspond well to the flanking density. In the bent conformation, MT1 is severely rotated relative to its position in the model based on the crystal structures (Figure 6a, 6d and Supporting Information Figure 7c). In this position, the MT1 active site entrance is inside the chamber of the AprA arch, ~50 Å from the ACP attachment site.

We hypothesize that AprA adopts different conformations during its catalytic cycle, and that this may protect the substrate from aberrant reactions. In one conformation, the ACP must be accessible to FabD to receive the malonyl starter unit. Given the promiscuity of AprA MT2, Mal-ACP must be protected from the MT2 active site to prevent premature decarboxylation prior to MT1 methylation. The MT1 reaction may occur in the bent state where the MT1 active site entrance is closer to the ACP attachment site. Once MT1 has formed Me2Mal-ACP, the MT1-ΨGNAT may swing to an open conformation to allow access to the MT2 active site, where the decarboxylative methylation forms pivaloyl-ACP.

In conclusion, our complete characterization of the apratoxin A loading module AprA describes a unique biochemical process to form t-butyl groups in natural product biosynthesis (Figure 4d), and clarifies a previously nebulous route to an unusual chemical functionality. First, the FAS malonyl-acyltransferase FabD loads the AprA ACP with malonyl from CoA. Malonyl-ACP is then dimethylated by the mononuclear iron-dependent methyltransferase AprA MT128. Dimethylmalonyl-ACP undergoes a coordinated decarboxylation and methylation reaction by AprA MT2 to form pivaloyl-ACP. The functional annotation of AprA serves as an identifier for gene clusters producing t-butyl-containing natural products, especially from marine sources, as exemplified by our identification and characterization of BryX MT2 from the bryostatin biosynthetic pathway. Our structural characterization of the full AprA module provides insight into the overall architecture and mobility of this remarkable multifunctional module.

METHODS

Details of experimental procedures are provided in the Supporting Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants DK042303 to J.L.S.; CA108874 to D.H.S., W.H.G., L.G. and J.L.S.; GM118815 to L.G and W.H.G.; and GM118101 to D.H.S. M.A.S. was supported by a predoctoral fellowships from an NIH Cellular Biotechnology Training Program (GM008353) and the University of Michigan Rackham Graduate School. A.P.S. was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from an NIH Molecular Biophysics Training Program (GM008270). N.A.M. was supported by a predoctoral fellowship from an NIH Marine Biotechnology Training Program (GM067550). GM/CA@APS is supported by the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences (AGM- 12006) and National Cancer Institute (ACB-12002). Molecular graphics and analyses for EM models were performed with the UCSF Chimera package. Chimera is developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco (supported by GM103311).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at http://pubs.acs.org

Detailed experimental procedures, Supporting Figures and Tables.

Accession Codes

The atomic coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID 6D6Y (AprA ΨGNAT-MT2)). The EM map has been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB ID EMD-7827).

References

- 1.Blunt JW, Copp BR, Keyzers RA, Munro MHG, Prinsep MR. Marine natural products. Nat Prod Rep. 2017;34:235–294. doi: 10.1039/c6np00124f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerwick WH, Moore BS. Lessons from the past and charting the future of marine natural products drug discovery and chemical biology. Chem Biol. 2012;19:85–98. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luesch H, Yoshida WY, Moore RE, Paul VJ, Corbett TH. Total structure determination of apratoxin A, a potent novel cytotoxin from the marine cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:5418–5423. doi: 10.1021/ja010453j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crews P, Farias JJ, Emrich R, Keifer PA. Milnamide A, an unusual cytotoxic tripeptide from the marine sponge Auletta cf. constricta. J Org Chem. 1994;59:2932–2934. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parent A, Guillot A, Benjdia A, Chartier G, Leprince J, Berteau O. The B12-radical SAM enzyme PoyC catalyzes valine Cβ-methylation during polytheonamide biosynthesis. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:15515–15518. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b06697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman MF, Helf MJ, Bhushan A, Morinaka BI, Piel J. Seven enzymes create extraordinary molecular complexity in an uncultivated bacterium. Nat Chem. 2017;9:387–395. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harunari E, Komaki H, Igarashi Y. Biosynthetic origin of butyrolactol A, an antifungal polyketide produced by a marine-derived Streptomyces. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2017;13:441–450. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.13.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishibashi M, Yamagishi E, Kobayashi J. Topsentinols A-J, new sterols with highly branched side chains from marine sponge Topsentia sp. Chem Pharm Bull. 1997;45:1435–1438. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mori S, Williams H, Cagle D, Karanovich K, Horgen FD, Smith R, III, Watanabe CM. Macrolactone nuiapolide, isolated from a Hawaiian marine cyanobacterium, exhibits anti-chemotactic activity. Mar Drugs. 2015;13:6274–6290. doi: 10.3390/md13106274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogawa H, Iwasaki A, Sumimoto S, Kanamori Y, Ohno O, Iwatsuki M, Ishiyama A, Hokari R, Otoguro K, Omura S, Suenaga K. Janadolide, a cyclic polyketide-peptide hybrid possessing a tert-butyl group from an Okeania sp. marine cyanobacterium. J Nat Prod. 2016;79:1862–1866. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pettit GR, Gao F, Sengupta D, Coll JC, Herald CL, Doubek DL, Schmidt JM, Van Camp JR, Rudloe JJ, Nieman RA. Isolation and Structure of Bryostatins 14 and 15. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:3601–3610. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klein D, Braekman JC, Daloze D, Hoffmann L, Castillo G, Demoulin VV. Madangolide and laingolide A, two novel macrolides from Lyngbya bouillonii. J Nat Prod. 1999;62:934–936. doi: 10.1021/np9900324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salvador-Reyes LA, Sneed J, Paul VJ, Luesch H. Amantelides A and B, polyhydroxylated macrolides with differential broad-spectrum cytotoxicity from a guamanian marine cyanobacterium. J Nat Prod. 2015;78:1957–1962. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shao CL, Linington RG, Balunas MJ, Centeno A, Boudreau P, Zhang C, Engene N, Spadafora C, Mutka TS, Kyle DE, Gerwick L, Wang CY, Gerwick WH. Bastimolide A, a potent antimalarial polyhydroxy macrolide from the marine cyanobacterium Okeania hirsuta. J Org Chem. 2015;80:7849–7855. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira AR, Cao Z, Engene N, Soria-Mercado IE, Murray TF, Gerwick WH. Palmyrolide A, an unusually stabilized neuroactive macrolide from Palmyra Atoll cyanobacteria. Org Lett. 2010;12:4490–4493. doi: 10.1021/ol101752n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Orjala J, Nagle DG, Hsu VL, Gerwick WH. Antillatoxin: an exceptionally ichthyotoxic cyclic lipopeptide from the tropical cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula. J Am Chem Soc. 1995;117:8281–8282. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagle DG, Paul VJ, Roberts MA. Ypaoamide, a new broadly acting feeding deterrent from the marine cyanobacterium Lyngbya majuscula. Tetrahedron Letters. 1996;37:6263–6266. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gallimore WA, Galario DL, Lacy C, Zhu Y, Scheuer PJ. Two complex proline esters from the sea hare Stylocheilus longicauda. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:1022–1026. doi: 10.1021/np990640j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teruya T, Sasaki H, Fukazawa H, Suenaga K. Bisebromoamide, a potent cytotoxic peptide from the marine cyanobacterium Lyngbya sp: isolation, stereostructure, and biological activity. Org Lett. 2009;11:5062–5065. doi: 10.1021/ol9020546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bisel P, Al-Momani L, Muller M. The tert-butyl group in chemistry and biology. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:2655–2665. doi: 10.1039/b800083b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakanishi K. The ginkgolides. Pure Appl Chem. 1967;14:89–113. doi: 10.1351/pac196714010089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grindberg RV, Ishoey T, Brinza D, Esquenazi E, Coates RC, Liu WT, Gerwick L, Dorrestein PC, Pevzner P, Lasken R, Gerwick WH. Single cell genome amplification accelerates identification of the apratoxin biosynthetic pathway from a complex microbial assemblage. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18565. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang KC, Chen Z, Jiang Y, Akare S, Kolber-Simonds D, Condon K, Agoulnik S, Tendyke K, Shen Y, Wu KM, Mathieu S, Choi HW, Zhu X, Shimizu H, Kotake Y, Gerwick WH, Uenaka T, Woodall-Jappe M, Nomoto K. Apratoxin A shows novel pancreas-targeting activity through the binding of Sec 61. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:1208–1216. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paatero AO, Kellosalo J, Dunyak BM, Almaliti J, Gestwicki JE, Gerwick WH, Taunton J, Paavilainen VO. Apratoxin kills cells by direct blockade of the Sec61 protein translocation channel. Cell Chem Biol. 2016;23:561–566. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu L, Geders TW, Wang B, Gerwick WH, Hakansson K, Smith JL, Sherman DH. GNAT-like strategy for polyketide chain initiation. Science. 2007;318:970–974. doi: 10.1126/science.1148790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Froese DS, Forouhar F, Tran TH, Vollmar M, Kim YS, Lew S, Neely H, Seetharaman J, Shen Y, Xiao R, Acton TB, Everett JK, Cannone G, Puranik S, Savitsky P, Krojer T, Pilka ES, Kiyani W, Lee WH, Marsden BD, von Delft F, Allerston CK, Spagnolo L, Gileadi O, Montelione GT, Oppermann U, Yue WW, Tong L. Crystal structures of malonyl-coenzyme A decarboxylase provide insights into its catalytic mechanism and disease-causing mutations. Structure. 2013;21:1182–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chun SW, Hinze ME, Skiba MA, Narayan ARH. Chemistry of a unique polyketide-like synthase. J Am Chem Soc. 2018 doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b13297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Skiba MA, Sikkema AP, Moss NA, Tran CL, Sturgis RM, Gerwick L, Gerwick WH, Sherman DH, Smith JL. A mononuclear iron-dependent methyltransferase catalyzes initial steps in assembly of the apratoxin A polyketide starter unit. ACS Chem Biol. 2017;12:3039–3048. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Skiba MA, Sikkema AP, Fiers WD, Gerwick WH, Sherman DH, Aldrich CC, Smith JL. Domain organization and active site architecture of a polyketide synthase C-methyltransferase. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:3319–3327. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sudek S, Lopanik NB, Waggoner LE, Hildebrand M, Anderson C, Liu H, Patel A, Sherman DH, Haygood MG. Identification of the putative bryostatin polyketide synthase gene cluster from “Candidatus Endobugula sertula”, the uncultivated microbial symbiont of the marine bryozoan Bugula neritina. J Nat Prod. 2007;70:67–74. doi: 10.1021/np060361d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liutkeviciute Z, Kriukiene E, Licyte J, Rudyte M, Urbanaviciute G, Klimasauskas S. Direct decarboxylation of 5-carboxylcytosine by DNA C5-methyltransferases. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:5884–5887. doi: 10.1021/ja5019223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheng X, Kumar S, Posfai J, Pflugrath JW, Roberts RJ. Crystal structure of the HhaI DNA methyltransferase complexed with S-adenosyl-L-methionine. Cell. 1993;74:299–307. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90421-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Keller JP, Smith PM, Benach J, Christendat D, deTitta GT, Hunt JF. The crystal structure of MT0146/CbiT suggests that the putative precorrin-8w decarboxylase is a methyltransferase. Structure. 2002;10:1475–1487. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(02)00876-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Deery E, Schroeder S, Lawrence AD, Taylor SL, Seyedarabi A, Waterman J, Wilson KS, Brown D, Geeves MA, Howard MJ, Pickersgill RW, Warren MJ. An enzyme-trap approach allows isolation of intermediates in cobalamin biosynthesis. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:933–940. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kozbial PZ, Mushegian AR. Natural history of S-adenosylmethionine-binding proteins. BMC Struct Biol. 2005;5:19. doi: 10.1186/1472-6807-5-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Storm PA, Herbst DA, Maier T, Townsend CA. Functional and structural analysis of programmed C-methylation in the biosynthesis of the fungal polyketide citrinin. Cell Chem Biol. 2017;24:316–325. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stevens DC, Wagner DT, Manion HR, Alexander BK, Keatinge-Clay AT. Methyltransferases excised from trans-AT polyketide synthases operate on N-acetylcysteamine-bound substrates. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2016 doi: 10.1038/ja.2016.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wagner DT, Stevens DC, Mehaffey MR, Manion HR, Taylor RE, Brodbelt JS, Keatinge-Clay AT. α-methylation follows condensation in the gephyronic acid modular polyketide synthase. Chem Commun (Camb) 2016;52:8822–8825. doi: 10.1039/c6cc04418b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller DA, Luo L, Hillson N, Keating TA, Walsh CT. Yersiniabactin synthetase: a four-protein assembly line producing the nonribosomal peptide/polyketide hybrid siderophore of Yersinia pestis. Chem Biol. 2002;9:333–344. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poust S, Phelan RM, Deng K, Katz L, Petzold CJ, Keasling JD. Divergent mechanistic routes for the formation of gem-dimethyl groups in the biosynthesis of complex polyketides. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2015;54:2370–2373. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luesch H, Yoshida WY, Moore RE, Paul VJ. New apratoxins of marine cyanobacterial origin from Guam and Palau. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10:1973–1978. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00014-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dorrestein PC, Bumpus SB, Calderone CT, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Aron ZD, Straight PD, Kolter R, Walsh CT, Kelleher NL. Facile detection of acyl and peptidyl intermediates on thiotemplate carrier domains via phosphopantetheinyl elimination reactions during tandem mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2006;45:12756–12766. doi: 10.1021/bi061169d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meluzzi D, Zheng WH, Hensler M, Nizet V, Dorrestein PC. Top-down mass spectrometry on low-resolution instruments: characterization of phosphopantetheinylated carrier domains in polyketide and non-ribosomal biosynthetic pathways. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:3107–3111. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2007.10.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fick RJ, Kroner GM, Nepal B, Magnani R, Horowitz S, Houtz RL, Scheiner S, Trievel RC. Sulfur-oxygen chalcogen bonding mediates AdoMet recognition in the lysine methyltransferase SET7/9. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:748–754. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horowitz S, Dirk LM, Yesselman JD, Nimtz JS, Adhikari U, Mehl RA, Scheiner S, Houtz RL, Al-Hashimi HM, Trievel RC. Conservation and functional importance of carbon-oxygen hydrogen bonding in AdoMet-dependent methyltransferases. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:15536–15548. doi: 10.1021/ja407140k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Florova G, Kazanina G, Reynolds KA. Enzymes involved in fatty acid and polyketide biosynthesis in Streptomyces glaucescens: role of FabH and FabD and their acyl carrier protein specificity. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10462–10471. doi: 10.1021/bi0258804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wesener SR, Potharla VY, Cheng YQ. Reconstitution of the FK228 biosynthetic pathway reveals cross talk between modular polyketide synthases and fatty acid synthase. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:1501–1507. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01513-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leao T, Castelao G, Korobeynikov A, Monroe EA, Podell S, Glukhov E, Allen EE, Gerwick WH, Gerwick L. Comparative genomics uncovers the prolific and distinctive metabolic potential of the cyanobacterial genus Moorea. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:3198–3203. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1618556114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kumar P, Koppisch AT, Cane DE, Khosla C. Enhancing the modularity of the modular polyketide synthases: transacylation in modular polyketide synthases catalyzed by malonyl-CoA:ACP transacylase. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:14307–14312. doi: 10.1021/ja037429l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.