Abstract

Primary cilia are sensory organelles that coordinate multiple cellular signaling pathways, including Hedgehog (HH), Wingless/Int (WNT) and Transforming Growth Factor-β (TGF-β) signaling. Similarly, primary cilia have been implicated in regulation of mTOR signaling, in which Tuberous Sclerosis Complex proteins 1 and 2 (TSC1/2) negatively regulate protein synthesis by inactivating the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) at energy limiting states. Here we report that TSC1 and TSC2 regulate Smoothened (SMO)-dependent HH signaling in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Reduced SMO-dependent expression of Gli1 was demonstrated in both Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− cells, and we found that Tsc1 is required for TGF-β induced phosphorylation of SMAD2/3 and subsequent expression of the HH signaling effector and transcription factor GLI2. Hedgehog signaling was restored in Tsc1−/− cells after exogenous expression of Gli2, whereas rapamycin restored HH signaling in Tsc2−/− cells. Furthermore, we observed that Tsc1−/− MEFs display significantly elongated cilia, whereas cilia in Tsc2−/− MEFs were shorter than normal. The elongated cilium phenotype of Tsc1−/− MEFs is likely due to increased mTORC1-dependent autophagic flux observed in these cells, as both the autophagic flux and the cilia length phenotype was restored by rapamycin. In addition, ciliary length control in Tsc1−/− MEFs was also influenced by reduced expression of Gli2, which compromised expression of Wnt5a that normally promotes cilia disassembly. In summary, our results support distinct functions of Tsc1 and Tsc2 in cellular signaling as the two genes affect ciliary length control and HH signaling via different mechanisms.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s00018-018-2761-8) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: TSC, mTOR, Autophagy, LC3b, Hedgehog signaling, TGF-β signaling, Primary cilia, WNT5a

Introduction

Mutations in the tumor suppressor genes encoding TSC1 (Hamartin) and TSC2 (Tuberin) cause a multisystemic tumor syndrome termed tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). TSC is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder of high penetrance with a prevalence of 1:10,000 [1] and is characterized by widespread dysplastic and neoplastic lesions [2]. TSC1 and TSC2 were originally found to form a heterodimeric complex that acts as a switch for turning off mTOR signaling by inactivating the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1). Active mTORC1 phosphorylates the eukaryotic initiation factor 4E-binding protein-1 (4E-BP1) and 40S ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) to promote protein synthesis [3, 4]. The phosphorylated form of 40S ribosome protein S6 is thus a marker for mTORC1 activity. The heterodimeric TSC complex negatively regulates mTORC1 activity via the GTPase activity of TSC2, towards the small G-protein RHEB (Ras homologue enriched in brain) [5]. The mTORC1 signaling cascade receives inputs from various upstream cues related to the metabolic and nutritional status of the cell and translates these into cell growth [4, 6]. In the presence of nutrients, mTORC1 is activated and promotes cell growth, including protein synthesis and energy storage. Conversely, during starvation mTORC1 is inhibited and autophagy is induced by AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), leading to generation of intracellular nutrients and energy during degradation of non-functional or non-essential organelles or protein aggregates [4, 6], in turn contributing to cell survival. During starvation AMPK promotes autophagy by activating ULK1 via phosphorylation at Ser317, Ser555, and Ser777, whereas in the presence of nutrients mTORC1 suppresses autophagy by hampering interaction between AMPK and ULK1 through phosphorylation of ULK1 at Ser757 [7]. In addition, the TSC complex activates mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2) [8], which regulates the cytoskeleton through its stimulation of F-actin stress fibers and Rho GTPases [9]. TSC1 and TSC2 also play a role in regulating pathways other than mTORC1/2. For example, TSC inactivation has been shown to cooperate with non-canonical Smoothened (SMO)-independent Hedgehog (HH) signaling to drive tumor growth in murine cerebellar granule neuron precursors [10]. Furthermore, TSC1 was demonstrated to be required for the proper activation of the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-SMAD2/3 pathway in HeLa cells [11]. Despite these advances, the roles of TSC1 and TSC2 in regulating signaling pathways independently of mTORC1/2 remain poorly understood.

Primary cilia are microtubule-based sensory organelles that emanate from the centrosomal mother centriole/basal body at the surface of many quiescent vertebrate cell types [12]. These cilia play critical roles in the coordination of multiple cellular signaling pathways, which are regulated by diverse chemical, physical, and morphogenetic cues during development and in tissue homeostasis [13, 14]. Defects in ciliary assembly, maintenance, and function are, therefore, associated with severe developmental defects and diseases, known as ciliopathies, which include congenital heart defects, skeletal dysplasia, renal diseases, cerebral anomalies, obesity, tumorigenesis, and cancer [12, 15–19]. The cellular signaling systems that are operated by primary cilia include HH [20, 21], Wingless/Int (WNT) [22–24], platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFR-α) [25–27], TGF-β [28, 29], Notch [30], Hippo [31], and mTOR signaling [32, 33]. Recent studies have also indicated a functional connection between autophagy and ciliogenesis and/or cilia-coordinated signaling, but there is currently no consensus on whether increased autophagy leads to longer or shorter cilia [34, 35].

The vertebrate HH signaling pathway is one of the best studied ciliary signaling pathways and is essential for embryonic development and the maintenance of multiple organs [36, 37]. The 12-pass transmembrane receptor patched homolog 1 (PTCH1) is localized to the ciliary membrane in the absence of HH and prevents ciliary localization of SMO, a class F, G-protein coupled receptor that is required for the activation of GLI transcription factors. In this “OFF” stage, GLI2 and GLI3 are proteolytically cleaved to form repressor forms (GLI-R), which block transcriptional activation of target genes in HH signaling. The binding of HH to PTCH1 induces ciliary exit of PTCH1 causing concomitant ciliary enrichment of SMO, which results in decreased ciliary cAMP production, and in stabilization of full-length forms of GLI2 and GLI3 (GLI2-FL and GLI3-FL) in the cilium followed by translocation of these proteins to the nucleus in their activated forms (GLI2-A and GLI3-A) to induce transcriptional activation of target genes, including Gli1 and Ptch1 [38–42].

Compared to HH signaling, less is known about the role of primary cilia in mTOR signaling. TSC1 was shown to localize to the base of the cilium [43], and its loss in zebrafish was associated with left–right asymmetry defects in addition to ciliary elongation [33]. An aberrant cilia phenotype was also reported in murine cells where loss-of-function mutations in either Tsc1 or Tsc2 induced elongation of primary cilia [43, 44]. In addition, primary cilia were shown to regulate mTORC1 activity through the LKB1-AMPK pathway in murine kidney cells [32]. While the heterodimeric TSC1-TSC2 complex plays a crucial regulatory role in mTORC1 activity, the need to evaluate the separate functions of TSC1 and TSC2 is evident. Although evidence supports the interdependence of TSC1 and TSC2 in the regulation of mTORC1 [45], more than 50 proteins have been reported to interact with TSC1 and/or TSC2 [46], suggesting that both proteins function in other cellular contexts independent of each other.

Here we report that both Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) affect ciliary length control and cellular signaling pathways, but via different mechanisms. First, we found that Tsc1−/− cells exhibited elongated cilia, which we show is due to dysregulated autophagy and mTORC1 activity as well as reduced GLI2-mediated expression of Wnt5a. In contrast, we observed significantly shortened cilia in Tsc2−/− cells. Second, while both Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs display impaired SMO-dependent HH signaling, TSC2 affects HH signaling via mTORC1, whereas TSC1 regulates HH signaling via the TGF-β-SMAD2/3 pathway, which in turn regulates expression of the GLI2 transcription factor required for HH target gene expression. Collectively, our results indicate that TSC1 and TSC2 affect ciliary length control and canonical HH signaling via different mechanisms.

Results

Primary cilia are elongated and shortened in Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs, respectively

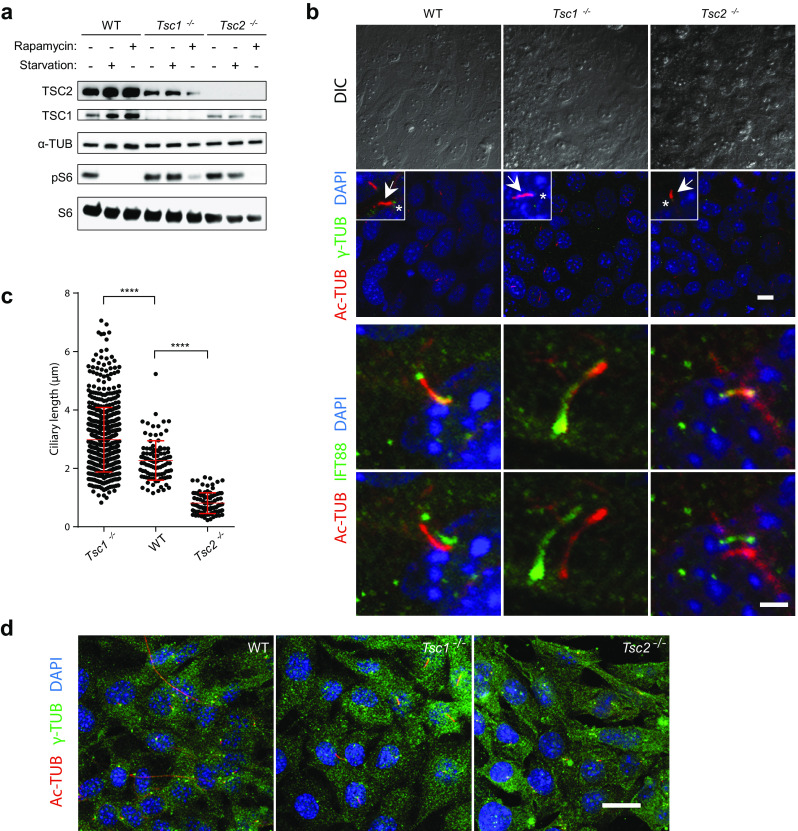

At low nutrient levels, the TSC1-TSC2 complex downregulates mTORC1 activity so that the loss of either protein is associated with constitutive activation of mTOR signaling [47, 48]. To confirm this, Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs were starved (0.5% fetal bovine serum, FBS) for 48 h and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and western blotting (WB) for the expression of Tsc1 and Tsc2, and the phosphorylation status of S6 (pS6), which is a marker for mTORC1 activity (Fig. 1a). As expected, TSC1 and TSC2 were absent in Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs, respectively. It has previously been demonstrated that TSC1 stabilizes TSC2 by protecting TSC2 from ubiquitination and proteosomal degradation [49]. This concurs with the lower level of TSC2 observed in Tsc1−/− MEFs (Fig. 1a). Furthermore, phosphorylation of S6 (pS6) was detectable in both Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs upon serum depletion, demonstrating constitutive mTORC1 activity. This activity was hampered by treatment with the mTORC1 inhibitor, rapamycin, verifying that phosphorylation of S6 is mTORC1-dependent (Fig. 1a).

Fig. 1.

Primary cilia are elongated in Tsc1−/− but shortened in Tsc2−/− cells. a SDS-PAGE and WB analyses of cell lysates from WT, Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs cultured in normal (-starvation) or starvation medium (0.5% FBS) for 48 h, using antibodies against TSC1, TSC2, S6 and phospho-S6 (pS6) as indicated, with antibody against α-tubulin (α-TUB) as loading control. Note the presence of pS6 in serum-starved Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− cells. b IFM analysis of primary cilia in WT, Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs cultured in starvation medium (0.5% FBS) for 48 h, to induce ciliogenesis. Cilia (arrows) were labeled with anti-acetylated α-tubulin (Ac-TUB) and anti-IFT88 antibodies and the ciliary base/centrosomes (asterisks) were labeled with anti-γ-tubulin (γ-TUB) antibody. Nuclei were visualized with differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy or DAPI staining. Lower panels show merged and shifted overlays of Ac-TUB- and IFT88-labeled cilia. Scale bar: 2 µM. c Quantification of cilia lengths for experiment shown in b. Three hundred cilia (Ac-TUB) from three independent experiments were used for quantification. d IFM analysis of WT, Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs labeled with DAPI, Ac-TUB and IFT88 for cell size comparison. Nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining. Scale bar: 5 µM

Next, we evaluated the consequence of TSC1 and TSC2 depletion on the frequency and length of primary cilia during serum starvation. To this end, Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs were serum starved (0.5% FBS) for 48 h to induce growth arrest and formation of primary cilia, and subsequently analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM) with antibodies against γ-tubulin that marks the ciliary base, acetylated α-tubulin that marks the cilium, and IFT88, which is component of the intraflagellar transport system and marks both the ciliary base and the cilium (Fig. 1b). While the frequency of ciliated cells appeared to be unaffected by depletion of either TSC1 or TSC2 (wild type (WT): 53.6 ± 10.4; Tsc1−/−: 56.6 ± 2.3; Tsc2−/−: 60.7 ± 5.9), we found that cilia in Tsc1−/− MEFs were significantly longer with an average length of 2.98 μm as compared to WT MEFs that displayed an average ciliary length of 2.20 μm (Fig. 1b, c), which is in accordance with previous observations [43]. In contrast, we observed that the length of primary cilia in Tsc2−/− cells was significantly decreased with a mean length of 0.74 μm (Fig. 1c). The observed ciliary length phenotypes of the mutant cells were not an indirect effect of increased cell size [50], since microscopic analysis showed that the sizes of mutant and wild type cells were largely similar (Fig. 1d). Furthermore, the ciliary length phenotype of the Tsc1−/− MEFs did not seem to be secondary to cell cycle defects, as judged by staining with antibody against acetylated tubulin and KI67, a potent proliferation marker; primary cilia were only induced in quiescent cells and re-addition of serum lead to cell cycle re-entrance as expected (Fig. 2a).

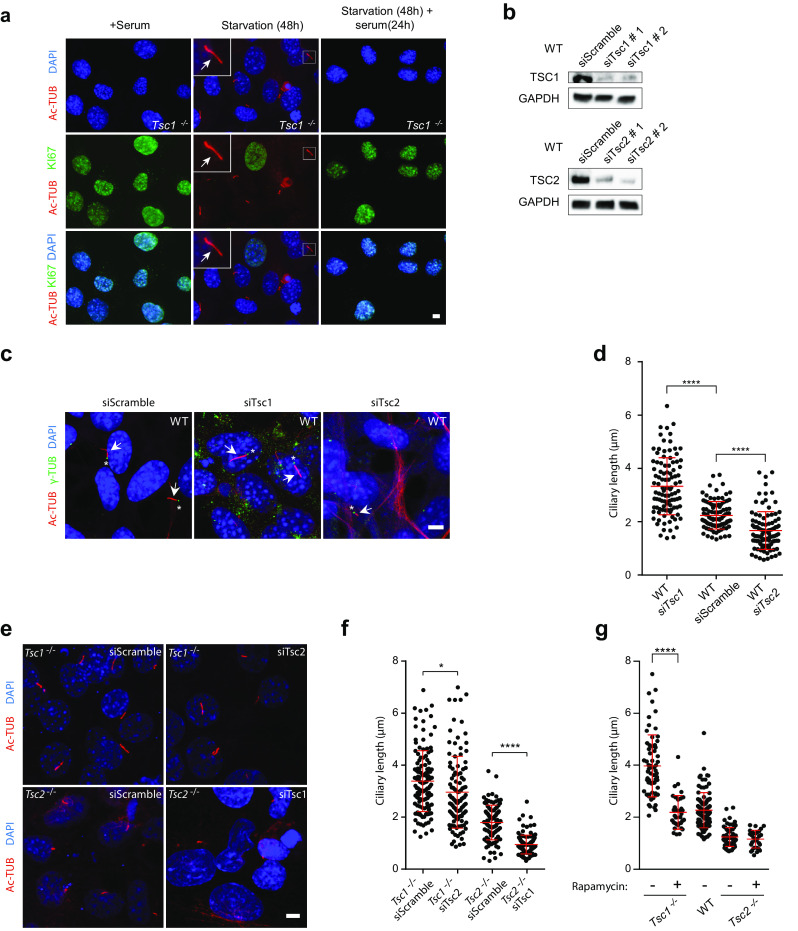

Fig. 2.

Rapamycin treatment rescues the ciliary length phenotype of Tsc1−/− cells. a IFM analysis of the expression of the proliferation marker KI67 and formation of primary cilia (arrows), labeled with anti-acetylated α-tubulin (Ac-TUB) antibody, in Tsc1−/− MEFs cultured in normal serum medium (left panels), in starvation medium (0.5% FBS) for 48 h (middle panels, with few proliferating cells), or after 48 h starvation followed by serum re-stimulation for 24 h (right panels, with many proliferating cells). b WB analysis of WT MEFs subjected to siRNA-mediated knock down of Tsc1 or Tsc2. WT MEFs were analyzed 48 h after transfection with siTsc1, siTsc2 or siScramble (negative control). GAPDH was used as loading control. c IFM analysis of primary cilia in WT MEFs after knock down of Tsc1 or Tsc2. Cilia (arrows) were labeled with Ac-TUB antibodies and the ciliary base/centrosomes (asterisks) were labeled with anti-γ-tubulin antibody (γ-TUB). Nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining. Scale bar: 5 µM. d Quantification of ciliary lengths for experiment shown in c. Three hundred cilia from three independent experiments were used for quantification; error bars represent SEM. e IFM analysis of primary cilia (Ac-TUB) in Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs subjected to siRNA-mediated knock down followed by culturing in starvation medium (0.5% serum) for 48 h (24 h after transfection) to induce cilia formation. Nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining. Scale bar: 5 µM. f Quantification of ciliary lengths for experiment shown in e. One hundred cilia from three independent experiments were used for quantification; error bars represent SEM. g Quantification of ciliary lengths labeled with Ac-TUB antibody in WT, Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs cultured in low 48 h in the presence or absence of rapamycin

We then asked if exogenous expression of TSC1 and TSC2 could rescue the ciliary length phenotype of Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− cells. While transfection with TSC1-encoding plasmid (pTSC1) partly restored the ciliary length in Tsc1−/− cells, only minor effect was observed by transfection of Tsc2−/− cells with TSC2-encoding plasmid (pTSC2) (Supplementary Figure 1a, b). The latter result could be due to a toxic effect of the transfection and/or aberrant production of a smaller protein product (Supplementary Figure 1c, d). The transfection efficiency, measured by transfection with pGFP plasmid, is 14–15% (Supplementary Figure 1e). As an alternative approach to confirm the ciliary length phenotypes of the Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− cells, we used siRNA to deplete TSC1 or TSC2 from WT MEFs (Fig. 2b). Using this approach, we found that the siRNA-depleted WT cells displayed similar ciliary lengths as observed in Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− cells, respectively (Fig. 2c, d), confirming the mutant cell phenotypes. To test the dominancy of the two genes, we furthermore subjected Tsc1−/− cells to siRNA-mediated depletion of TSC2, and vice versa (Fig. 2e; Supplementary Figure 2). In both cases, a reduction in the ciliary length was observed, indicating that the absence of Tsc2 is dominant for the resulting phenotype (Fig. 2f).

Finally, we induced cilia formation in starvation medium (0.5% FBS) in combination with rapamycin and found that the ciliary length phenotype of Tsc1−/− MEFs was rescued by this treatment, while rapamycin had no observable effect on the ciliary length in Tsc2−/− MEFs (Fig. 2g). These results support the conclusion that the increased ciliary length in Tsc1−/− MEFs is associated with aberrant activity of mTORC1. Consistent with Hartman et al. [43], the ciliation frequency in WT, Tsc1−/− and, Tsc2−/− cells did not appear to be affected by rapamycin.

Tsc1−/− MEFs exhibit increased mTORC1-dependent autophagy

Several studies have shown that autophagy regulates ciliary length [34, 35, 51–55]. To test for differences in autophagic activity between Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs, we performed an autophagic flux assay, measuring the net flux of LC3B-II in starvation medium (0.5% FBS), stimulating both autophagy and formation of primary cilia (Fig. 3a). LC3B is expressed as a pro-LC3B protein, which is subsequently cleaved by removing the C terminus to produce the cytosolic form, LC3B-I. The cytosolic form is conjugated with phosphatidylethanolamine to form the membrane-bound LC3B-II, which is attached to the autophagosome membrane reflecting maturation of the autophagosomes. After fusion of the autophagosomes with lysosomes, LC3B-II is degraded or released as LC3B-I through delipidation. Turnover of LC3-II thus reflects the autophagic activity [35]. The net flux and the amount of LC3B-I and LC3B-II were significantly increased in the Tsc1−/− cells compared to the WT and Tsc2−/− cells (Fig. 3b–d). As the cilia length in Tsc1−/− cells was reduced in the presence of rapamycin (Fig. 2g), we investigated the effect of rapamycin on autophagy. Rapamycin reduced the net flux, and the amount of LC3B-I and LC3B-II in the Tsc1−/− cells to levels comparable to that of WT cells. No effect of rapamycin on LC3B was observed for the WT or the Tsc2−/− cells (Fig. 3a–d). This indicates that the long cilia phenotype in Tsc1−/− cells may be a result of increased net flux. Compared to Tsc2−/− and WT cells, Tsc1−/− cells seem to contain larger amounts of LC3B protein. Recalculating the efflux relative to the amount of LC3B-I eliminated the difference between the cell lines and the effect of rapamycin on the Tsc1−/− cells (legend Fig. 3d). Thus, the increased amount of LC3B-II in Tsc1−/− cells correlates with the increased LC3B-I level.

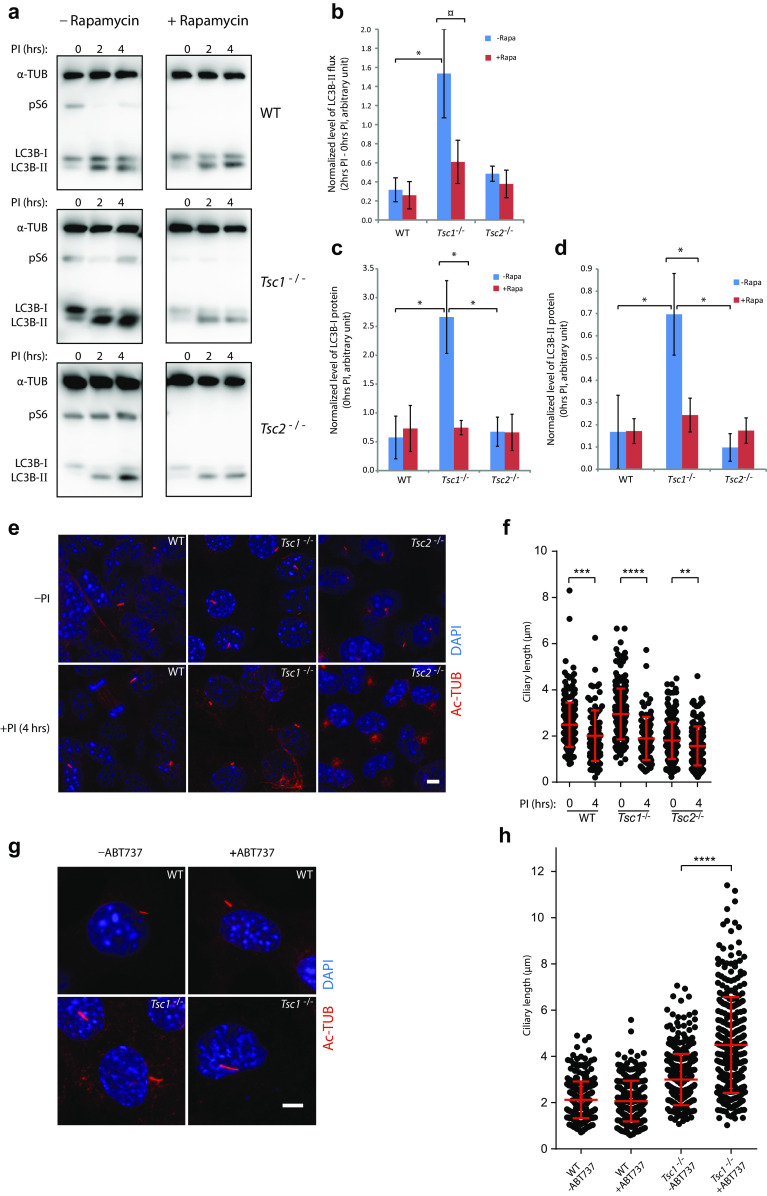

Fig. 3.

Loss of Tsc1 leads to increased mTORC1-dependent autophagic activity. a SDS-PAGE and WB analyses on the level of LC3B and phosphoS6 (pS6) in WT, Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs starved (0.5% FBS) for 48 h in the absence or presence of rapamycin (Rapa) (24 h) followed by treatment with lysosomal protease inhibitors (PI) as indicated. α-tubulin (α-TUB) was used as loading control. b Normalized LC3B-II flux for experiments shown in a as measured by the LC3B-II protein levels after 2 h PI treatment subtracted the protein levels at 0 h. c Normalized LC3B-I protein levels for experiments shown in a before PI treatment. d Normalized LC3B-II protein levels for experiments shown in a before PI treatment. b–d Quantifications of LC3B-I/II protein levels were performed by densitometric analysis and normalized to α-TUB, and to a control sample loaded on all gels to correct for blotting efficiency. Error bars represent SEM (n = 3). Recalculating of the LC3B-II flux relative to the amount of LC3B-I eliminated the difference between the cell lines and the effect of rapamycin on the Tsc1−/− cells (WT: 0.506 ± 0.087/0.584 ± 0.864; Tsc1−/−: 0.6261 ± 0.314/0.864 ± 0.443; Tsc2−/−: 0.673 ± 0.253/0.662 ± 0.314. No statistic significant differences were obtained). e IFM analysis of primary cilia labeled with anti-γ-tubulin (γ-TUB) antibody in WT, Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs after 4 h PI treatment. Scale bar: 5 µM. f Quantification of ciliary lengths for experiment shown in e. One hundred cilia from three independent experiments were used for quantification; error bars represent SEM. g IFM analysis of primary cilia labeled with γ-TUB antibody in serum-deprived (48 h) WT and Tsc1−/− MEFs in the presence and in the absence of the autophagy inducer ABT-737. Scale bar: 5 µM. h Quantification of ciliary lengths for experiment shown in g. One hundred cilia from two independent experiments were used for quantification; error bars represent SEM

To test the effect of the autophagic activity on the ciliary length more directly, we investigated the ciliary length in the Tsc1−/− cells after treatment with lysosomal protease inhibitors for 4 h to inhibit autophagy, and found a profound reduction (Fig. 3e, f). However, a significant reduction in the ciliary length in both the Tsc2−/− and the WT cells was also observed (Fig. 3f). In contrast, treatment with the autophagy inducer ABT-737 [56] strongly induced ciliary elongation in the Tsc1−/− cells, whereas no effect was observed in the WT cells (Fig. 3g, h). In summary, these results indicate that autophagy initiated by serum starvation is important for the growth of the primary cilium in general, whereas increased autophagy specifically causes ciliary lengthening in the Tsc1−/− cells.

Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs display impaired SMO-dependent HH signaling

Some evidence points to a possible link between the HH and mTOR signaling, since a combination therapy inhibiting both pathways results in an enhanced therapeutic effect compared to inhibiting either pathway alone [57]. Therefore, we speculated whether HH signaling is altered in Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs. To monitor HH signaling, we initially performed quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) analysis of the expression of the HH target genes, Gli1 and Ptch1 in cells starved (0.5% FBS) for 48 h to induce cilia formation. To activate canonical HH signaling, the SMO agonist purmorphamine [58] was added for the last 24 h of cultivation. Furthermore, cells were cultured in the presence and in the absence of rapamycin to evaluate the role of mTORC1 in purmorphamine-induced expression of the target genes. As shown (Fig. 4a, b), purmorphamine-induced expressions of Gli1 and Ptch1 were significantly reduced in both Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs as compared to WT cells. However, rapamycin treatment restored the mRNA levels to WT levels only in Tsc2−/− MEFs, indicating that defects in HH signaling are associated with increased mTORC1 activity in Tsc2−/− MEFs. Since rapamycin treatment abrogated the elongated cilia phenotype observed in Tsc1−/− MEFs (Fig. 2g), we further conclude that the long cilia phenotype observed in these cells (Fig. 1) is not directly caused by aberrant HH signaling or vice versa.

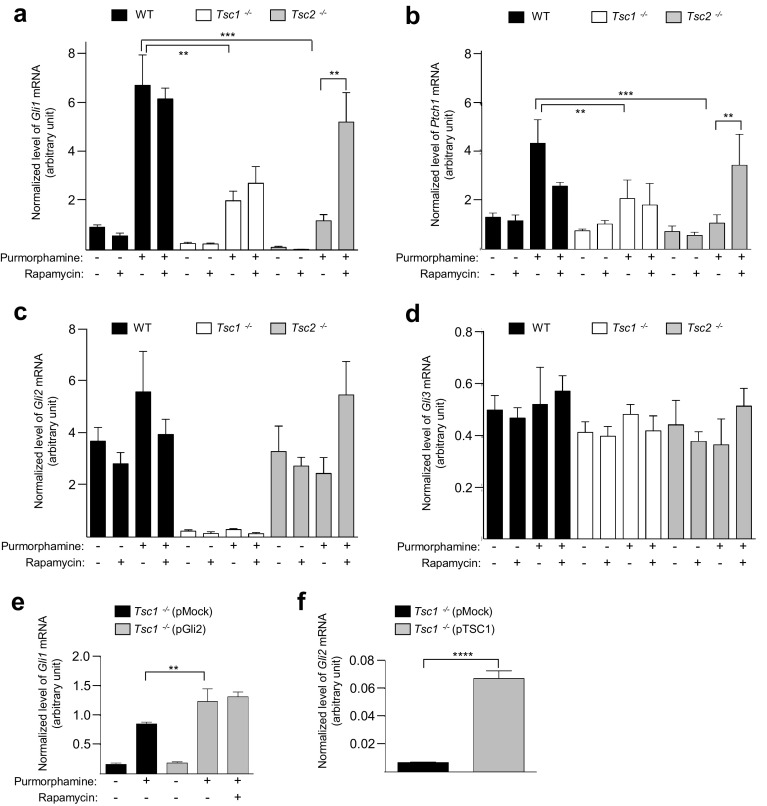

Fig. 4.

Loss of Tsc1 or Tsc2 is associated with impaired HH signaling. a–d WT, Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs were starved (0.5% FBS) for 48 h to induce cilia formation in the presence or absence of rapamycin. Purmorphamine (5 µM) was administered to the medium for the final 24 h to stimulate HH signaling before mRNA isolation and qPCR analysis. Expression profiles of the target genes were normalized to the amount of endogenous Tbp mRNA. Normalized expression profiles of a Gli1, b Ptch1. Error bars represent SEM (n = 5). Normalized expression profiles of c Gli2 and d Gli3. e Normalized expression profiles of Gli1 in Tsc1−/− MEFs transfected with 2 µg plasmid (pMock (empty vector) or pGli2) and cultured in starvation medium (0.5% FBS) for 48 h (24 h after transfection) with purmorphamine administration (for the last 24 h), as indicated. Error bars represent SEM (n = 3). The reduced signal in e compared to a might be due to transfection (pMock included) of the cells. f Normalized expression profiles of Gli2 in Tsc1−/− MEFs transfected with 1 µg plasmid (pMock or pTSC1) and starved (0.5% serum) for 48 h (24 h after transfection). Error bars represent SEM (n = 3)

To further investigate the mechanisms by which HH signaling is impaired in Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs, we then performed qPCR analysis of the mRNA levels of Gli2 and Gli3, which are generally constitutively expressed in normal cells [59, 60]. In these experiments, we observed that the expression of Gli2, but not Gli3, is greatly reduced in Tsc1−/− cells, both in the presence and absence of purmorphamine and rapamycin (Fig. 4c, d). Cellular fractionation and WB analysis confirmed the absence of detectable GLI2 in the nucleus of Tsc1−/− cells (Supplementary Figure 3). This indicates that reduced expression of Gli1 and Ptch1 may be caused by the lack of a sufficient level of activator forms of GLI2 independent of mTORC1 activity. In contrast, Tsc2−/− MEFs displayed normal expression levels of both Gli2 mRNA and Gli3 mRNA compared to WT cells (Fig. 4c, d). To determine whether decreased HH signaling in Tsc1−/− MEFs can be explained by the loss of GLI2, we examined HH signaling in Tsc1−/− MEFs in which a plasmid expressing GLI2 was introduced. In agreement with our hypothesis, exogenous expression of Gli2 caused significantly elevated expression of Gli1 in response to purmorphamine treatment in these cells (Fig. 4e; Supplementary Figure 4). We also evaluated the level of Gli2 mRNA in Tsc1−/− MEFs subjected to exogenous expression of TSC1, by transfecting the cells with the pTSC1 plasmid. In this case, we observed a ~ tenfold increase in the level of Gli2 transcript, establishing a direct link between TSC1 and Gli2 expression (Fig. 4f; Supplementary Figure 5). Finally, inhibition of mTORC1 activity by rapamycin did not affect the purmorphamine-induced increase in Gli1 expression in Tsc1−/− MEFs even after introducing exogenous Gli2 (Fig. 4e). This indicates that TSC1 regulates HH signaling through the expression of Gli2 and this regulation is independent of mTORC1 activity.

TSC1 regulates HH signaling via a TGF-β-SMAD2/3-dependent pathway

Previous studies have shown that primary cilia in fibroblasts coordinate canonical TGF-β signaling through clathrin-dependent endocytosis of activated receptors at the ciliary pocket followed by phosphorylation and activation of SMAD2/3 transcription factors in early endosomes around the ciliary base region [28]. Activated SMAD2/3 then forms a heterotrimeric complex with SMAD4, which translocates to the nucleus for expression of target genes. Interestingly, several reports have indicated that GLI2 is a target gene for SMAD2/3 signaling in various human cell lines including fibroblasts [61, 62], and it has recently been shown that TSC1, independently of TSC2, is required for the association between TGF-β receptors and SMAD2/3, so that the knockdown of TSC1 causes an impaired phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of SMAD2/3 in HeLa cells [11]. We therefore speculated whether canonical TGF-β signaling is impaired in Tsc1−/− MEFs, leading to a reduced expression of Gli2. To address this, we investigated SMAD2/3 phosphorylation in response to TGF-β1 stimulation. In contrast to WT and Tsc2−/− MEFs, SMAD2/3 phosphorylation was significantly reduced in Tsc1−/− MEFs after 1 h of stimulation with TGF-β1 (Fig. 5a), showing that TSC1, but not TSC2, is required for activation of canonical TGF-β signaling, as previously observed in HeLa cells [11].

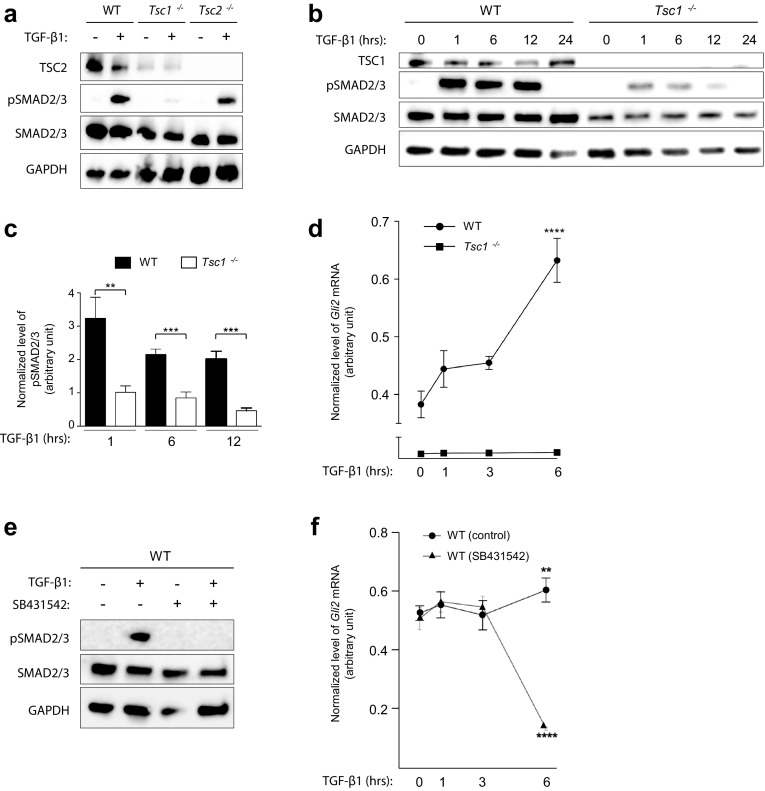

Fig. 5.

Tsc1−/− cells display impaired TGF-β-SMAD2/3 signaling. a SDS-PAGE and WB analyses of WT, Tcs1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs serum starved (0.5% serum) for 48 h to induce cilia formation in the presence or absence of TGF-β1 for 45 min. Antibodies against TSC2, phospho-SMAD2/3 (pSMAD2/3) and SMAD2/3 were used as indicated. GAPDH was used as loading control. b SDS-PAGE and WB analyses of WT and Tsc1−/− MEFs serum starved for 48 h in the presence of TGF-β1 for the indicated time points. c Quantification of relative levels of pSMAD2/3 normalized to total SMAD2/3 for experiment shown in b. Error bars represent SEM (n = 3). d Normalized expression profiles of Gli2 mRNA in WT and Tsc1−/− MEFs cultured to confluence in complete medium and subjected to TGF-β1 stimulation for the indicated time points before RNA isolation and qPCR. Error bars represent SEM (n = 3). e SDS-PAGE and WB analyses of WT MEFs cultured in serum deprived (0.5% FBS, 48 h) in the presence or absence of TGF-β1 and SB431542 for 45 min. f Normalized expression profiles of Gli2 mRNA in WT MEFs cultured in complete medium and subjected to TGF-β1 in the presence or absence of SB431542 for the indicated time points. Error bars represent SEM (n = 3). Expression profiles of Gli2 were normalized to endogenous Tbp mRNA

To further examine whether the loss of TSC1 merely results in a delayed response to TGF-β1 stimulation, we evaluated the level of SMAD2/3 phosphorylation in Tsc1−/− MEFs after 1, 6, 12, and 24 h of ligand treatment. These experiments showed that SMAD2/3 phosphorylation is reduced at all investigated time points (Fig. 5b, c), thereby substantiates the conclusion that TSC1 plays a critical role in the activation of SMAD2/3. No SMAD2/3 phosphorylation could be observed after 24 h (Fig. 5b) in agreement with a previous study showing that SMAD2/3 phosphorylation peaks after 1 h of ligand exposure, and declines over the next 8 h, to finally cease [63].

To investigate a potential relationship between impaired Gli2 expression and SMAD2/3 phosphorylation in Tsc1−/− MEFs, we carried out qPCR analysis on Gli2 expression in response to TGF-β1 stimulation in these cells. Interestingly, an increase in Gli2 expression was evident in WT MEFs for at least 6 h while no response in Tsc1−/− MEFs was observed during this time interval (Fig. 5d). As a control for ligand specificity in receptor-mediated SMAD2/3 phosphorylation and requirement for TGF-β signaling in Gli2 expression, SDS-PAGE, WB and qPCR analyses showed that administration of the TGF-β receptor antagonist, SB431542 [64], abolished SMAD2/3 phosphorylation (Fig. 5e) and greatly reduced the expression of Gli2 in WT MEFs (Fig. 5f).

Reduced Gli2 expression affects Wnt5a expression resulting in elongated cilia in Tsc1−/− MEFs

The prominent differences in the lengths of primary cilia in Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs (Fig. 1b, c) suggest that signaling defects in these cells may also have an impact on ciliary length control. Both TGF-β and HH signaling have been shown to regulate the expression of the gene encoding the non-canonical WNT ligand, WNT5A [65–67], which is known to control ciliary length by inducing disassembly of the primary cilium [65, 66, 68, 69]. We therefore hypothesized that Wnt5a expression in Tsc1−/− MEFs is compromised as a result of low Gli2 expression. To investigate this, growth-arrested ciliated cells were subjected to re-addition of serum for different times to monitor the expression of Wnt5a by qPCR analysis during ciliary disassembly and cell cycle re-entry. As shown in Fig. 6a, the level of Wnt5a mRNA was clearly detected in WT and Tsc2−/− MEFs, but almost undetectable in Tsc1−/− MEFs (Fig. 6a), in agreement with our hypothesis. As Wnt5a has been shown also to be regulated by GLI3 [65], we furthermore investigated the GLI3-FL/GLI3-R ratio in WT and Tsc1−/− MEFs before and after purmorphamine stimulation. Whereas a significant increase in the GLI3-FL/GLI3-R ratio could be observed in the WT MEFs as an effect of the purmorphamine stimulation, indicating higher amount of active GLI3, no effect could be observed in the and Tsc1−/− cells (Supplementary Figure 3). Therefore, we cannot exclude that reduced formation GLI3-FL in conjunction with low levels of GLI2 is involved in the reduced amount of Wnt5a mRNA observed in the Tsc1−/− MEFs.

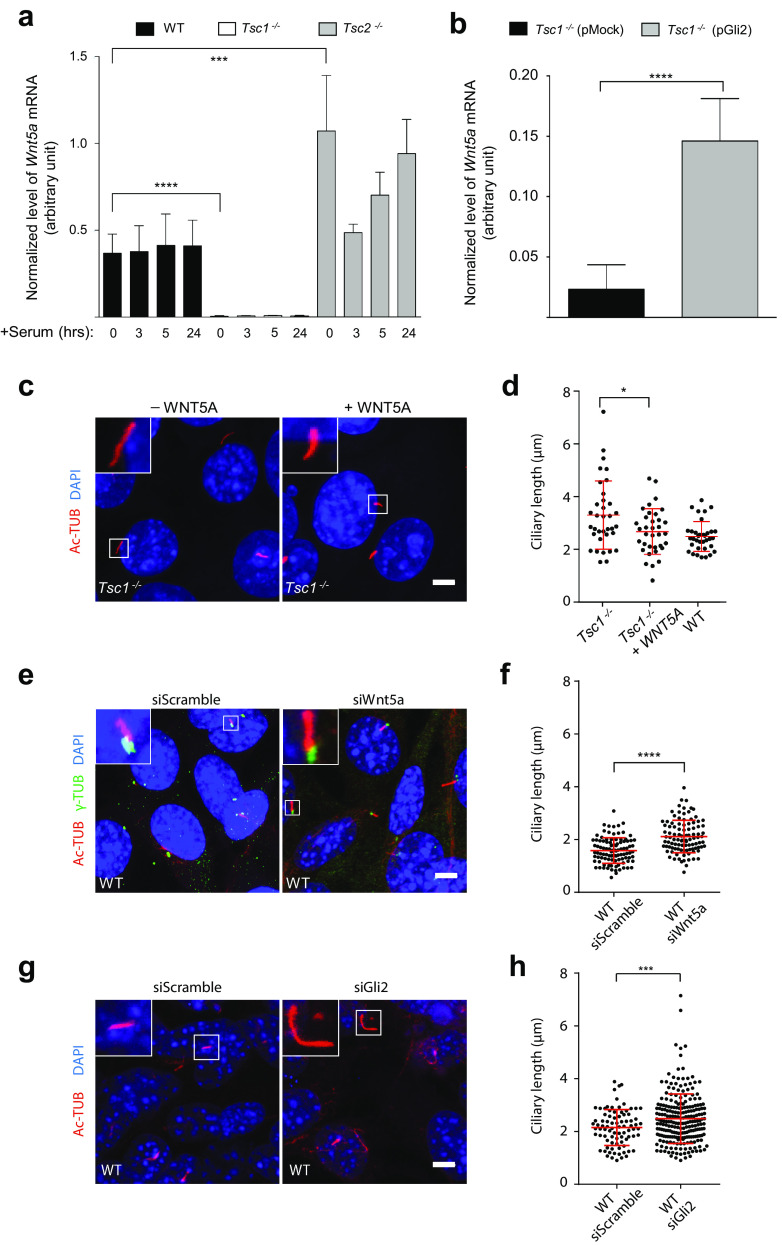

Fig. 6.

Cilia elongation in Tsc1−/− cells is partly abrogated by WNT5a administration. a Normalized expression profiles of Wnt5a mRNA in WT, Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs starved (0.5% FBS) for 48 h followed by serum re-stimulation (10% FBS) for the indicated time points. Error bars represent SEM (n = 3). b Normalized expression profiles of Wnt5a mRNA in Tsc1−/− MEFs transfected with 1 µg plasmid (pMock (empty vector) or pGli2) and cultured in complete medium for 48 h before RNA isolation and qPCR. Error bars represent SEM (n = 3). a, b Expression profiles of Wnt5a were normalized to endogenous Tbp mRNA. c IFM analysis of primary cilia in Tsc1−/− MEFs serum deprived for 48 h in the presence and in the absence of recombinant WNT5A. Cilia were labeled with anti-acetylated α-tubulin (Ac-TUB) antibodies. Nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining. d Quantification of ciliary lengths for experiment shown in c. One hundred cilia from three independent experiments were used for quantification; error bars represent SEM (n = 3). e IFM analysis of primary cilia in WT MEFs transfected with either siScramble or siWnt5a for 24 h followed by serum deprivation for 48 h before analysis. Cilia were labeled with Ac-TUB antibody and the ciliary base/centrosome was labeled with anti-γ-tubulin (γ-TUB) antibody. Nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining. f Quantification of ciliary lengths for experiment shown in e. Three hundred cilia from three independent experiments were used for quantification; error bars represent SEM. g IFM analysis of primary cilia (Ac-TUB) in WT MEFs transfected with either siScramble or siGli2 for 24 h followed by serum deprivation for 48 h before analysis. Nuclei were visualized with DAPI staining. h Quantification of ciliary lengths for experiment shown in g. Two hundred cilia from three independent experiments were used for quantification; error bars represent SEM. Scale bars (c, e, g): 5 µM

To further investigate the relationship between the expression of Gli2 and Wnt5a, we transfected Tsc1−/− MEFs with the GLI2-encoding plasmid and found an increased expression of Wnt5a (Fig. 6b, Supplementary Figure 4). Indeed, stimulation with recombinant WNT5a restored the length of cilia in Tsc1−/− MEFs to a level comparable to that of WT cells (Fig. 6c, d), supporting the conclusion that reduced expression of Wnt5a contribute to the elongated cilia phenotype of Tsc1−/− MEFs. To confirm this observation, we used siRNA to knock down Wnt5a in WT MEFs and subsequently measured ciliary length after culturing the cells for 24 h in starvation medium (0.5% FBS). An increased ciliary length was observed, compared to cells transfected with an siRNA construct containing a scramble sequence (Fig. 6e, f; Supplementary Figure 6), confirming that the expression of Wnt5a promotes ciliary shortening. Moreover, siRNA-mediated knock down of Gli2 in WT MEFs (Fig. 6g; Supplementary Figure 7) lead to ciliary lengthening (Fig. 6h), supporting that Wnt5a expression depends on GLI2.

It is possible that other factors than GLI2, including GLI3, may be involved in regulation of Wnt5a expression as elevated Wnt5a expression was observed in Tsc2−/− MEFs (Fig. 6a), which is consistent with their short cilia phenotype, although the level of Gli2 mRNA in Tsc2−/− MEFs was comparable to the level in WT cells (Fig. 4c).

Discussion

The heterodimeric TSC complex that consists of TSC1 (Hamartin) and TSC2 (Tuberin) plays a critical role in coordinating extracellular signals with intracellular energy status to control cell proliferation and growth [48]. However, the independent functions of the two TSC proteins are less well known. In this study, we investigated the cilia phenotypes in MEFs lacking either TSC1 or TSC2. While our observation of elongated cilia in Tsc1−/− MEFs is in accordance with previous results [33, 43, 44], our observations of reduced ciliary length in Tsc2−/− are not [43]. In a previous study performed by Hartman et al. [43], it was found that the cilia in both Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs were 17–27% longer than WT cilia resulting in the average length of 1.54 µm in Tsc1−/− cells and 1.40 µm in Tsc2−/− cells, respectively [43]; in both cases, shorter than the average cilia length of 2.7 µm measured in our WT cells. The reason for this discrepancy is unknown. Hartman et al. cultured the cells for 48 h completely without serum [43], but in our system, we were not able to obtain viable cells under these conditions. We confirmed our results by demonstrating similar cilia phenotypes in cells subjected to siRNA-mediated knock down of Tsc1 and Tsc2, respectively. In addition, whereas Hartman et al. [43] found that the length of the cilia was insensitive to rapamycin treatment, we found that inhibition of mTORC1 activity abrogated the long cilia phenotype in Tsc1−/− MEFs. That loss of TSC1 causes elongated cilia in a rapamycin-sensitive manner has previously been reported in Tsc1 conditional knockout distal convoluted tubules in mice [44], and in Danio rerio (zebrafish) [33, 51].

Increased mTORC1 activity was observed in both the Tsc2−/− and Tsc1−/− cells, as expected, due to lack of inhibition of mTORCI. It is also generally accepted that increased mTORC1 activity is associated with reduced autophagy [47, 48], but surprisingly we observed that loss of Tsc1 led to increased autophagic flux, and both increased mTORC1 activity and increased autophagy was inhibited by rapamycin treatment. The increased autophagic flux in the Tsc1−/− cells correlated with an increased level of LC3B, which may indicate increased autophagy as it has been shown that starvation leads to fast conversion of LC3B-I to LC3B-II (after 15–30 min) and to increased expression of LC3B after long time starvation [70]. In line with a recent study in mouse bone marrow macrophages [71], we also found that loss of Tsc1 in MEFs leads to increased amount of LC3B protein, which can be normalized by rapamycin. In addition, Tsc1−/− macrophages dispalyed increased number of autophagosomes, activation of AMPK, phosphorylation of ULK1 (site Ser555), and increased amount of Beclin1 protein, all observations supporting increased autophagic activity in the Tsc1−/− cells [71].

Several studies have shown that autophagy regulates cilia length [34, 35, 51–55], but with disagreement about whether increased autophagy leads to longer or shorter cilia. Three different studies [52, 53, 55] demonstrated that cigarette smoke, flavonoid silibinin and the anti-malaria medicine mefloquine lead to increased autophagy. However, whereas cigarette smoke and silibinin treatments was associated with shortening of cilia in mouse lung tissue and embryonic preadipocytes [52, 55], cilia were elongated as an effect of mefloquine treatment in RPE cells [53]. Furthermore, the effect of Atg5, a gene essential for autophagy, was investigated in three other studies, with different outcomes [34, 35, 54]. Whereas longer cilia were observed in mutant MEFs in one study [35], shorter and reduced number of cilia were observed in two other studies in Atg5 mutant MEFs and mice kidney proximal tubular cells, respectively [34, 54], indicating that autophagy induces cilia growth, in agreement with our results.

Further, our data show that treatment with lysosomal protease inhibitors reduces the ciliary length in both WT and mutant MEFs, and treatment with the autophagy inducer ABT-737 leads to cilia elongation in Tsc1−/− cells. These observations indicate that nutrient deprivation-induced ciliogenesis depends on proteins delivered by autophagy. Furthermore, the rapamycin-sensitive long cilia phenotype observed in Tsc1−/− cells indicates that active mTORC1 in these cells is a prerequisite for increased cilium elongation. This result is in agreement with previous observations of cilia in Kupffer’s vesicle (ciliated epithelial organ) of Tsc1−/− zebrafish, where rapamycin treatment was shown to cause cilia shortening and overexpression of S6K1 led to ciliary lengthening [51].

As a result of low energy stress due to the constitutive mTORC1 activation in Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− cells, it is possible that AMPK is activated. AMPK induces autophagy, directly through phosphorylation of ULK1 (Ser555) and indirectly through phosphorylation of TSC2, which then inhibits mTORC1 [7]. The increased autophagic activity in Tsc1−/− relative to Tsc2−/−cells might be due to the lack of TSC2 in Tsc2−/− cells. The reduced autophagic activity in WT cells compared to Tsc1−/− cells might be due to an intact TSC1/TSC2 complex in WT cells capable of keeping the mTOR activity under control, preventing overuse of resources. Thus, the increased level of autophagy in Tsc1−/− cells compared to WT cells might be a result of constitutive mTORC1 activation, which in turn may promote ciliary extension, in agreement with the observed ciliary lengthening in the Tsc1−/− cells, but not in WT cells, as a result of ABT-737-induced autophagy. Alternatively, the observed increased autophagy in Tsc1−/− cells could be due to a yet unknown TSC1-dependent mechanism on autophagy (Fig. 7).

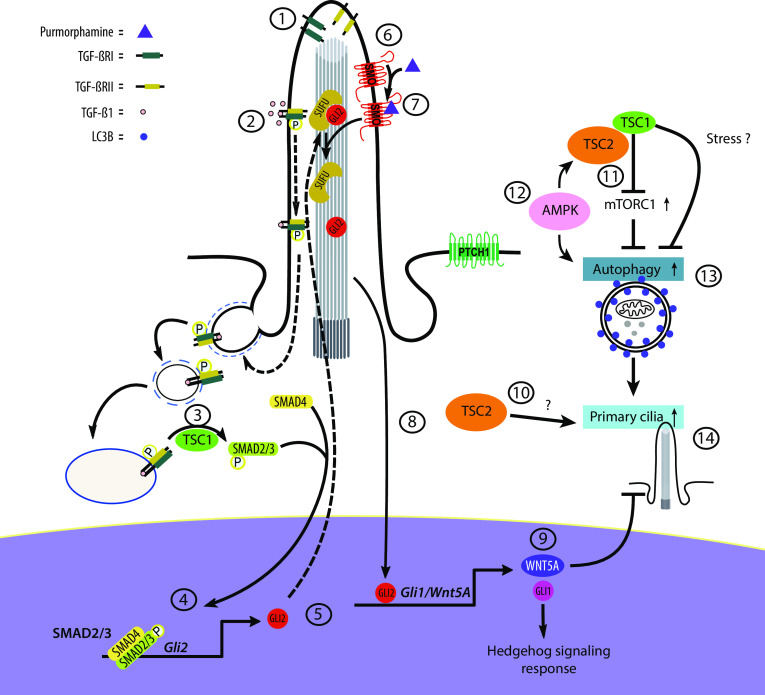

Fig. 7.

Model illustrating the effect of TSC1 on HH signaling, ciliogenesis and cilia disassembly. 1: TGF-β receptors (TGF-β-RI and TGF-β-RII) localize to the ciliary tip. 2: TGF-β1 stimulation leads to heterotetramerization of the receptors and activation by phosphorylation of SMAD2/3 at the ciliary base. 3: TSC1 is required for this step. 4: phosphorylated SMAD2/3 (pSMAD2/3) acts (in a trimeric complex with SMAD4) as transcription factor leading to expression of Gli2. 5: GLI2 is translocated to the cilium where it is inhibited by SUFU (negative regulator of HH). 6: inactive SMO is activated by its agonist purmorphamine. 7: activation of SMO leads to removal of SUFU followed by expression of Gli2. 8: active GLI2 enters the nucleus as a transcription factor leading to expression of Gli1 and Wnt5a. 9: WNT5A mediates primary cilia disassembly. 10: Tsc2-deficient cells display shortened primary cilia. 11: the TSC1/TSC2 complex downregulates mTORC1, leading to increased autophagy. 12: during starvation AMPK promotes autophagy directly and indirectly through phosphorylation of TSC2, which then inhibit mTORC1. 13: Tsc1-deficient cells display increased mTORC1 activity but at the same time mTORC1-dependent increased autophagic flux. 14: autophagic activity stimulates ciliogenesis

While few studies have focused on cross-talk between HH and mTORC1 signaling, the progression of epithelial to mesenchymal transition, which marks the potential invasiveness and metastatic potential of tumors, was shown to be diminished by rapamycin in a xenograft model of rhabdomyosarcoma in a manner that not only inhibited mTORC1 activity but also HH signaling [72]. Furthermore, a cross-talk between the two pathways has been described in a model of esophageal cancer where mTORC1/S6K1 promotes the oncogenic function of GLI1, through S6K1-mediated phosphorylation of GLI1, in a SMO-independent manner [57]. We here show that TSC1 and TSC2 via different mechanisms play critical roles in activation of canonical, SMO-dependent HH signaling adding further complexity to the role of mTOR signaling components in coordinating diverse HH pathways. In both Tsc1−/− and Tsc2−/− MEFs, the levels of Gli1 and Ptch1 expression in purmorphamine-stimulated cells were greatly reduced as compared to WT cells, but the ability to respond to purmorphamine was to a large degree restored by rapamycin only in Tsc2−/− MEFs. These results suggest that the activation of canonical HH signaling relies on the inhibition of mTORC1 activity in a TSC2-dependent manner, while TSC1 largely operates through mTORC1-independent pathway(s) to ensure robust HH signaling in response to activation of SMO. Indeed, we demonstrate that impaired HH signaling in Tsc1−/− MEFs, is due to low expression of Gli2, likely as a result of impaired TGF-β-SMAD2/3 signaling (Fig. 5a). This is in line with previous work showing that SMAD2/3 activation is impaired in Tsc1−/− but not in Tsc2−/− cells [11].

It is important to address the question of how and where TSC1 contributes to proper TGF-β signaling. We did not investigate expression levels and the cellular localization of TGF-β receptors, but previous studies showed that receptors and downstream signaling components in TGF-β signaling are enriched in primary cilia and at the ciliary base region [28]. In fibroblasts, TGF-β1 stimulation leads to a translocation of TGF-β receptors from the cilium to the ciliary pocket, for clathrin-mediated endocytosis of the activated TGF-β receptors, and phosphorylation of SMAD2/3 in early endosomes at the ciliary base region [28] (Fig. 7). Since TSC1 contains a putative transmembrane domain [73] and localizes to the ciliary base in human RPE cells [43] and early endosomes in HeLa cells [11], TSC1 may function at the primary cilium to regulate TGF-β receptor-mediated activation of SMAD2/3, although speculative at this point.

TGF-β-SMAD2/3 signaling has previously been associated with TSC as the expression of TGF-β ligand is upregulated in angiofibromas obtained from TSC patients [74]. However, the genotype of the TSC patients examined in this study was not specified. Furthermore, TGF-β activates mTORC1 in murine fibroblasts but not in epithelial cells via a PI3 K/AKT/TSC2-dependent pathway [75]. It remains to be investigated whether this effect on mTOR activity is compromised only in Tsc2−/− MEFs.

Since TGF-β and HH signaling converge at the level of GLI2, we further elaborated on the link between low Gli2 expression and the observed elongated ciliary length phenotype in Tsc1−/− MEFs. TGF-β1-driven Gli2 expression contributes to canonical HH signaling, but Gli2 may also regulate target gene expression downstream of TGF-β signaling, including expression of genes encoding members of the WNT protein family [68]. In the canonical WNT pathway, binding of WNT ligands to Frizzled receptors induces β-catenin stabilization and entry into the nucleus to regulate target gene transcription. However, the so-called non-canonical WNT proteins, such as WNT5A [76], are involved in alternate signaling cascades including a role in WNT5A-PLK1-dependent stimulation of Aurora A kinase, leading to the disassembly of the primary cilium [69]. We here demonstrate that a low Gli2 mRNA level correlated with reduced Wnt5a expression, which in turn contributes to an elongated ciliary length phenotype. The cilia length in the Tsc1−/− cells was reduced by both recombinant WNT5A and by rapamycin treatment. Whereas reduced expression of Wnt5a could be explained by aberrant TGF-β-SMAD2/3 signaling, the effect of rapamycin could be explained by mTORC1-dependent increased autophagic flux in the Tsc1−/− MEFs. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that rapamycin treatment also leads to even shorter cilia in Tsc2−/− cells, as the cilia are already very short and difficult to measure by our microscopy setup.

In summary, we have demonstrated that loss of TSC1 causes both increased autophagic flux and impaired SMO-dependent HH signaling due to reduced expression of Gli2. The long cilia phenotype in Tsc1−/− MEFs could be explained by a combination of increased cilia growth due to increased autophagic flux and reduced rate of disassembly due to reduced expression of the transcription factor Gli2 that regulates the expression of Wnt5a (Fig. 7). Although substantial progress has been made in understanding the role of the heterodimeric complex formed by the proteins encoded by TSC1 and TSC2 in TSC pathology, many questions remain regarding the separate functions of these two genes. Addressing these questions in the future will contribute to a better understanding of the molecular etiology of TSC and potential new opportunities for therapy.

Materials and methods

Cell cultures and reagents

All mouse embryonic fibroblast cells were obtained from D. Kwiatkowski, Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA. They were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with Glutamax, 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 1% penicillin–streptomycin. The cells were grown in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. To induce ciliary formation cells were starved (0.5% FBS) for 48 h, and to measure autophagic flux cells were cultured in the presence and in the absence of rapamycin before lysosomal degradation was inhibited by 20 mM ammonium chloride (NH4Cl, Sigma-Aldrich #A-0171) and 200 µm Leupeptin (Biovision #1648) for 2 or 4 h. Cells were treated with 25 nM rapamycin (Cell Signaling Technology #9904) for 48 h to inhibit mTORC1 activity and 5 µM purmorphamine (Santa Cruz biotechnologies #sc-202785) for 24 h to activate HH signaling (last 24 h of the 48 h in starvation medium). To induce autophagy, cells were further incubated with 10 µM ABT-737 (Selleckchem # S1002) for 24 h. SMAD2/3 signaling was stimulated with 2 ng ml−1 recombinant human TGF-β1 (R&D Biosystems #240-B) and inhibited with 10 μM SB431542 (InvivoGen #inh-sb43) for indicated time points. Recombinant human/mouse WNT5a (fragment Gln38Lys380, which is identical in mouse and human expressed in Chinese Hamster Ovary cell line, R&D Biosystems #645-WN) was administered to the cells at 300 nM for 24 h prior to induction of ciliary formation in starvation medium (0.5% FBS). Primary antibodies used for IFM were as follows (dilutions, vendor and catalog number in parenthesis): mouse anti-acetylated α tubulin (1:2000, Sigma-Aldrich #T6793), rabbit anti-α-tubulin (1:1000, Sigma-Aldrich #T5192), rabbit anti-KI67 (1:250, Abcam #ab15580), rabbit anti-IFT88 (1:1000, Nordic Biosite/Proteintech, 13967-1-ap). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa fluor 546 donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:1000, Invitrogen # A10036) and Alexa fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG(1:1000, Invitrogen # A11008). Dnase I (Invitrogen, 18068015) was used for degradation of plasmids present in RNA samples. The following primary antibodies were used for WB analysis (dilutions, vendor and catalog number in parenthesis): rabbit anti-phospho-S6 Ribosomal Protein (1:1000, Cell Signaling # 4858), rabbit anti-GAPDH (1:5000, Cell Signaling #2118), rabbit anti-total-S6 Ribosomal Protein (1:1000, Cell Signaling #2217), rabbit anti-TSC1 (1:500, Abcam #ab25882), rabbit anti-TSC2 (1:1000, Cell Signaling #4308), rabbit anti-phospho-SMAD2 (1:1000 Cell Signaling #3101), rabbit anti-total-SMAD2 (1:1000 Cell Signaling #5339), goat anti GLI2 antibody (1:1000 R&D system AF3635-SP), goat anti-GLI3 (1:1000 R&D system AF3690-SP) rabbit anti Lamin A antibody (1:1000, abcam ab26300), mouse anti-α-tubulin (1:5000, Sigma-Aldrich #T6199) and rabbit anti LC3B (1:250, Sigma-Aldrich #L7543. Secondary antibodies used were HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:2000, DAKO, # P0447), HRP-conjugated Swine anti-rabbit IgG (1:2000, DAKO, # P0399) and HRP-conjugated rabbit anti-goat IgG (1:2000, DAKO, #Pol60).

Immunofluorescence microscopy (IFM) and imaging analysis

Approximately 0.5 × 106 cells per well were seeded in a 6-well plate containing glass coverslips and allowed to incubate in complete medium (DMEM containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin–streptomycin) for 24 h prior to cilia induction by culturing cells in starvation medium (0.5% FBS) for 48 h followed by three times washing in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). They were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, washed three times in PBS, permeabilized with 1% Triton-X-100 in PBS for 15 min, and incubated in blocking solution [PBS containing 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA)] for 30 min. The cells were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C and washed three times in blocking solution. Secondary antibodies were added for 45 min at room temperature followed by washing for 5 min in blocking solution. They were then incubated with 0.5 μg ml−1 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole for 30 s to stain DNA, washed three times in PBS and mounted with an anti-fading mounting gel containing N-propyl gallate (Sigma-Aldrich #P3130). All procedures were performed at room temperature. Confocal microscopy was performed using an Olympus Fluoview 1000 FV. Adjustments to brightness and contrast were minimal and applied to the whole image. Z-stacked images were Z-projected and Fiji software (http://fiji.sc) was used for measuring cilia length.

SDS-PAGE and WB analyses

The cells were lysed with ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 6.8, 10% glycerol, 2.5% SDS, 10 mM DTE, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM NaF, 0.1 mM Na-orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 1× complete protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (Roche #11697498001), vortexed for 10 s and left on ice for 30 min followed by 3 × 10 s. sonication, and centrifuged for 5 min at 13,000 rpm at 4 °C. Supernatant fractions were used for protein analysis. Total protein (20 μg) was separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. After applying blocking solution (100 mM Tris pH 7.6, 0.1% Tween 20, 5% dry milk) for 45 min at room temperature, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies and left over night at 4 °C. They were then washed five times in TBS-T (100 mM Tris pH 7.6, 0.1% Tween 20), followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, which were detected with SuperSignal™ West Dura (ThermoFisher Scientific # 34076) and digitally developed by chemiluminescence using G:Box Chemi XX6 (Syngene). Where necessary, the membranes were stripped by two rinses in stripping solution (1% Tween 20, 0.1% SDS, 1.5% glycine, pH 2.2) followed by two rinses in PBS and TBS-T. The membranes were then ready to be blocked again. The optical density of the bands was analyzed with the gel analyzer of the Fiji software.

Plasmid transfection and siRNA-mediated gene knock down

The following plasmids were used for transient plasmid transfection: GFP-tagged Gli2 (pGli2, mouse) (Addgene #37672), Myc-tagged human WT-TSC1, pTSC1 and human TSC2-Flag, pTSC2 (both a gift from Mark Nellist, Erasmus MC, Rotterdam). JetPRIME (Polyplus transfection, Illkirch, France) was used as the transfection reagent following the protocol provided by the manufacturer. RNA silencing was achieved using siRNA targeting mouse Tsc1 (#1: TTGGTTGATTATTACCTGGAA #2: ATCGAGAAAGATAAGGAAGAA), Tsc2 (#1: CAGCATTAATATCTTATCACA #2: CTGGACATCATTGAACGACTA), Wnt5a (AAGATCTTAAATATAGATATA) and Gli2 (CACCAACCCTTCAGACTATTA) or a scramble sequence for control at a final concentration of 25 nM. All siRNAs were from Qiagen and delivered to cells using DharmaFECT1 transfection reagent (Dharmacon), following the protocol provided by the manufacturers.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis (qPCR)

For cDNA preparation total RNA was extracted from the cell cultures using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) following the instructions provided by the manufacturer. To validate the transfection efficiency with plasmids (p.TSC1, p.TSC2, p.Gli2), an isolated RNA was treated with DNase I (11284932001 Roche) before cDNA preparation according to the manufacturer’s protocol. An empty p.cDNA3 vector was used for Mock transfection. The RNA concentration was determined using a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For cDNA preparation, reverse transcription was carried out using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Standard qPCR was carried using predesigned TaqMan probes (Thermo Fisher Scientific) targeting the gene of interest. The measurements are performed in triplicates. The expression levels were normalized to the level of TATA binding protein (TBP) in the same samples after amplification with the TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems) and the − ΔΔCt method was used to evaluate differential expression [77]. The Ct value is the cycle number at which the fluorescence generated within a reaction crosses the threshold line. Ct levels are inversely proportional to the amount of target in the sample, the lower the Ct level the greater the amount of target. ΔCt is the difference in Ct values for our target gene and our housekeeping gene (Tbp) for a given sample (normalized values) and ΔΔCt is the difference in ΔCt values between treated and untreated samples [77]. The negative value − ΔΔCt, is used as the exponent of 2 in the equation and represents the difference in normalized number of Ct values. The exponent 2 is used based on the assumption that each cycle doubles the amount of product. If the control sample ΔCt is 4 and the treated sample ΔCt is 2, then (2−(2–4)) yields 4, meaning that the gene of interest in the treated sample is increased four times in comparison to the control sample.

Cellular fractionation

Cellular fractionation was performed as described previously [78].

Statistical analysis

Quantitative results represent the mean of at least three independent experiments, if not specified otherwise. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM, n ≥ 3). p values were calculated using Student’s t test, if not specified otherwise. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001). ¤: borderline value p = 0.055.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Kwiatkowski, Harvard University, Boston for the MEF cells, Mark Nellist, Erasmus MC Rotterdam for the Tsc1 and Tsc2 constructs. We also thank Louise Lindbæk and Johanne Bay Mogensen for technical assistance. This study was supported by the Independent Research Fund Denmark (#12-127196, #6108-00457) and by the University of Copenhagen (UCPH) excellence program for interdisciplinary research.

Abbreviations

- HH

Hedgehog

- WNT

Wingless/Int

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor-β

- TSC

Tuberous sclerosis complex

- MEFs

Mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- 4E-BP1

4E-binding protein-1

- S6K1

40S ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1

- PTCH1

Patched homolog 1

- SMO

Smoothened

Footnotes

Thomas Rosengren and Lasse Jonsgaard Larsen contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Anlauf M, Garbrecht N, Bauersfeld J, et al. Hereditary neuroendocrine tumors of the gastroenteropancreatic system. Virchows Arch. 2007;451:29–38. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0450-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Curatolo P, Bombardieri R, Jozwiak S. Tuberous sclerosis. Lancet. 2008;372:657–668. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jozwiak J. Hamartin and tuberin: working together for tumour suppression. Int J Cancer. 2005;118:1–5. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma XM, Blenis J. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:307–318. doi: 10.1038/nrm2672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long X, Lin Y, Ortiz-Vega S, et al. Rheb binds and regulates the mTOR kinase. Curr Biol. 2005;15:702–713. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laplante M, Sabatini DM. mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell. 2012;149:274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, et al. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang J, Dibble CC, Matsuzaki M, Manning BD. The TSC1-TSC2 complex is required for proper activation of mTOR complex 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4104–4115. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00289-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacinto E, Loewith R, Schmidt A, et al. Mammalian TOR complex 2 controls the actin cytoskeleton and is rapamycin insensitive. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1122–1128. doi: 10.1038/ncb1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatia B, Nahlé Z, Kenney AM. Double trouble: when Sonic hedgehog signaling meets TSC inactivation. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:456–459. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.3.10532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thien A, Prentzell MT, Holzwarth B, et al. TSC1 activates TGF-β-Smad2/3 signaling in growth arrest and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Dev Cell. 2015;32:617–630. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Satir P, Christensen ST. Overview of structure and function of mammalian cilia. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:377–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.040705.141236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen ST, Morthorst SK, Mogensen JB, Pedersen LB. Primary cilia and coordination of receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) signaling. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;9:a028167. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a028167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schou KB, Pedersen LB, Christensen ST. Ins and outs of GPCR signaling in primary cilia. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:e201540530–e201541113. doi: 10.15252/embr.201540530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hildebrandt F, Benzing T, Katsanis N. Ciliopathies. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1533–1543. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1010172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cortés CR, McInerney-Leo AM, Vogel I, et al. Mutations in human C2CD3 cause skeletal dysplasia and provide new insights into phenotypic and cellular consequences of altered C2CD3 function. Sci Rep. 2016;6:24083. doi: 10.1038/srep24083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geddes GC, Stamm K, Mitchell M, Mussatto KA. Ciliopathy variant burden and developmental delay in children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Genet Med. 2016;19:711–714. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berbari NF, Lewis JS, Bishop GA, et al. Bardet-Biedl syndrome proteins are required for the localization of G protein-coupled receptors to primary cilia. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:4242–4246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711027105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berbari NF, Pasek RC, Malarkey EB, et al. Leptin resistance is a secondary consequence of the obesity in ciliopathy mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:7796–7801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210192110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huangfu D, Murcia NS, Liu A, et al. Hedgehog signalling in the mouse requires intraflagellar transport proteins. Nature. 2003;426:83. doi: 10.1038/nature02061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huangfu D, Anderson KV. Cilia and Hedgehog responsiveness in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2005;102:11325–11330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505328102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe D, Saijoh Y, Nonaka S, et al. The left-right determinant Inversin is a component of node monocilia and other 9 + 0 cilia. Development. 2003;130:1725–1734. doi: 10.1242/dev.00407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerdes JM, Liu Y, Zaghloul NA, et al. Disruption of the basal body compromises proteasomal function and perturbs intracellular Wnt response. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1350–1360. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Veland IR, Montjean R, Eley L, et al. Inversin/nephrocystin-2 is required for fibroblast polarity and directional cell migration. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider L, Clement CA, Teilmann SC, et al. PDGFRalphaalpha signaling is regulated through the primary cilium in fibroblasts. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1861–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneider L, Cammer M, Lehman J, et al. Directional cell migration and chemotaxis in wound healing response to PDGF-AA are coordinated by the primary cilium in fibroblasts. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2010;25:279–292. doi: 10.1159/000276562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clement DL, Mally S, Stock C, et al. PDGFRα signaling in the primary cilium regulates NHE1-dependent fibroblast migration via coordinated differential activity of MEK1/2–ERK1/2–p90RSK and AKT signaling pathways. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:953–965. doi: 10.1242/jcs.116426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clement CA, Ajbro KD, Koefoed K, et al. TGF-β signaling is associated with endocytosis at the pocket region of the primary cilium. Cell Rep. 2013;3:1806–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Labour M-N, Riffault M, Christensen ST, Hoey DA. TGFβ1-induced recruitment of human bone mesenchymal stem cells is mediated by the primary cilium in a SMAD3-dependent manner. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35542. doi: 10.1038/srep35542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ezratty EJ, Stokes N, Chai S, et al. A role for the primary cilium in Notch signaling and epidermal differentiation during skin development. Cell. 2011;145:1129–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Habbig S, Bartram MP, Müller RU, et al. NPHP4, a cilia-associated protein, negatively regulates the Hippo pathway. J Cell Biol. 2011;193:633–642. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201009069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boehlke C, Kotsis F, Patel V, et al. Primary cilia regulate mTORC1 activity and cell size through Lkb1. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:1115–1122. doi: 10.1038/ncb2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.DiBella LM, Park A, Sun Z. Zebrafish Tsc1 reveals functional interactions between the cilium and the TOR pathway. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:595–606. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang Z, Lin GM, Stowe TR, et al. Autophagy promotes primary ciliogenesis by removing OFD1 from centriolar satellites. Nature. 2013;502:254–258. doi: 10.1038/nature12606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pampliega O, Orhon I, Patel B, et al. Functional interaction between autophagy and ciliogenesis. Nature. 2013;502:194–200. doi: 10.1038/nature12639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.De Luca A, Cerrato V, Fucà E, et al. Sonic hedgehog patterning during cerebellar development. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:291–303. doi: 10.1007/s00018-015-2065-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang J, Andre P, Ye L, Yang Y-Z. The Hedgehog signalling pathway in bone formation. Int J Oral Sci. 2015;7:73–79. doi: 10.1038/ijos.2015.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kasper M, Regl G, Frischauf A-M, Aberger F. GLI transcription factors: mediators of oncogenic Hedgehog signalling. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:437–445. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singh B, Koyano-Nakagawa N, Donaldson A, et al. Hedgehog signaling during appendage development and regeneration. Genes. 2015;6:417–435. doi: 10.3390/genes6020417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mukhopadhyay S, Rohatgi R. G-protein-coupled receptors, Hedgehog signaling and primary cilia. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014;33:63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santos N, Reiter JF. A central region of Gli2 regulates its location to the primary cilium and transcriptional activity. J Cell Sci. 2014;127:1500–1510. doi: 10.1242/jcs.139253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mukhopadhyay S, Wen X, Ratti N, et al. The ciliary G-protein-coupled receptor Gpr161 negatively regulates the Sonic hedgehog pathway via cAMP signaling. Cell. 2013;152:210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hartman TR, Liu D, Zilfou JT, et al. The tuberous sclerosis proteins regulate formation of the primary cilium via a rapamycin-insensitive and polycystin 1-independent pathway. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:151–163. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Armour EA, Carson RP, Ess KC. Cystogenesis and elongated primary cilia in Tsc1-deficient distal convoluted tubules. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2012;303:F584–F592. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00141.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dibble CC, Elis W, Menon S, et al. TBC1D7 is a third subunit of the TSC1-TSC2 complex upstream of mTORC1. Mol Cell. 2012;47:535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hanneder M, Siegel N, Valli A, Hengstschläger M. The tuberous sclerosis gene products hamartin and tuberin are multifunctional proteins with a wide spectrum of interacting partners. Mutat Res. 2008;658:234–246. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang H, Cicchetti G, Onda H, et al. Loss of Tsc1/Tsc2 activates mTOR and disrupts PI3 K-Akt signaling through downregulation of PDGFR. J Clin Investig. 2003;112:1223–1233. doi: 10.1172/JCI200317222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kwiatkowski DJ, Zhang H, Bandura JL, et al. A mouse model of TSC1 reveals sex-dependent lethality from liver hemangiomas, and up-regulation of p70S6 kinase activity in Tsc1 null cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:525–534. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.5.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Benvenuto G, Li S, Brown SJ, et al. The tuberous sclerosis-1 (TSC1) gene product hamartin suppresses cell growth and augments the expression of the TSC2 product tuberin by inhibiting its ubiquitination. Oncogene. 2000;19:6306–6316. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Edinger AL, Thompson CB. Akt maintains cell size and survival by increasing mTOR-dependent nutrient uptake. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2276–2288. doi: 10.1091/mbc.01-12-0584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yuan S, Li J, Diener DR, et al. Target-of-rapamycin complex 1 (Torc1) signaling modulates cilia size and function through protein synthesis regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2021–2026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112834109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lam HC, Cloonan SM, Bhashyam AR, et al. Histone deacetylase 6-mediated selective autophagy regulates COPD-associated cilia dysfunction. J Clin Investig. 2013;123:5212–5230. doi: 10.1172/JCI69636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shin JH, Bae DJ, Kim ES, et al. Autophagy regulates formation of primary cilia in mefloquine-treated cells. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2015;23:327–332. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2015.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang Livingston MJ, Su Y, et al. Reciprocal regulation of cilia and autophagy via the MTOR and proteasome pathways. Autophagy. 2015;11:607–616. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1023983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu Q, Liu W, Liu X, et al. Silibinin negatively contributes to primary cilia length via autophagy regulated by histone deacetylase 6 in confluent mouse embryo fibroblast 3T3–L1 cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016;420:53–63. doi: 10.1007/s11010-016-2766-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yao X, Li X, Zhang D, et al. B cell lymphoma 2 inhibitor ABT-737 induces Beclin1- and reactive oxygen species-dependent autophagy in Adriamycin-resistant human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Tumour Biol. 2017;39:1010428317695965. doi: 10.1177/1010428317695965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Y, Ding Q, Yen C-J, et al. The crosstalk of mTOR/S6K1 and Hedgehog pathways. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:374–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sinha S, Chen JK. Purmorphamine activates the Hedgehog pathway by targeting Smoothened. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;2:29–30. doi: 10.1038/nchembio753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bai CB, Auerbach W, Lee JS, et al. Gli2, but not Gli1, is required for initial Shh signaling and ectopic activation of the Shh pathway. Development. 2002;129:4753–4761. doi: 10.1242/dev.00115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ikram MS, Neill GW, Regl G, et al. GLI2 is expressed in normal human epidermis and BCC and induces GLI1 expression by binding to its promoter. J Investig Dermatol. 2004;122:1503–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dennler S, Andre J, Alexaki I, et al. Induction of sonic Hedgehog mediators by transforming growth factor: Smad3-dependent activation of Gli2 and Gli1 expression in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6981–6986. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hu M, Yao J, Carroll DK, et al. Regulation of in situ to invasive breast carcinoma transition. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:394–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vizan P, Miller DSJ, Gori I, et al. Controlling Long-term signaling: receptor dynamics determine attenuation and refractory behavior of TGF-β pathway. Sci Signal. 2013;305:ra106. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2004416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Inman GJ, Nicolás FJ, Callahan JF, et al. SB-431542 is a potent and specific inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta superfamily type I activin receptor-like kinase (ALK) receptors ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;62:65–74. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mullor JL, Dahmane N, Sun T, Altaba ARI. Wnt signals are targets and mediators of Gli function. Curr Biol. 2001;11:769–773. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00229-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu G, Moro A, Zhang J, et al. The role of Shh transcription activator Gli2 in chick cloacal development. Dev Biol. 2007;303:448–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kumawat K, Menzen MH, Slegtenhorst RM, et al. TGF-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) signaling regulates TGF-β-induced WNT-5A expression in airway smooth muscle cells via Sp1 and β-catenin. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94801. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eichberger T, Sander V, Schnidar H, et al. Overlapping and distinct transcriptional regulator properties of the GLI1 and GLI2 oncogenes. Genomics. 2006;87:616–632. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lee KH, Johmura Y, Yu L-R, et al. Identification of a novel Wnt5a–CK1ε–Dvl2–Plk1-mediated primary cilia disassembly pathway. EMBO J. 2012;31:3104–3117. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Karim MR, Kawanago H, Kadowaki M. A quick signal of starvation induced autophagy: transcription versus post-translational modification of LC3. Anal Biochem. 2014;465:28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pan H, Zhong XP, Lee S. Sustained activation of mTORC1 in macrophages increases AMPKα-dependent autophagy to maintain cellular homeostasis. BMC Biochem. 2016;17:14. doi: 10.1186/s12858-016-0069-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kaylani SZ, Xu J, Srivastava RK, et al. Rapamycin targeting mTOR and hedgehog signaling pathways blocks human rhabdomyosarcoma growth in xenograft murine model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;435:557–561. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hoogeveen-Westerveld M, Exalto C, Maat-Kievit A, et al. Analysis of TSC1 truncations defines regions involved in TSC1 stability, aggregation and interaction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1802:774–781. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee CH, Hong CH, Yu HS, et al. Transforming growth factor-β enhances matrix metalloproteinase-2 expression and activity through AKT in fibroblasts derived from angiofibromas in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1238–1244. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rahimi RA, Andrianifahanana M, Wilkes MC, et al. Distinct roles for mammalian target of rapamycin complexes in the fibroblast response to transforming growth factor-β. Cancer Res. 2009;69:84–93. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mikels AJ, Nusse R. Purified Wnt5a protein activates or inhibits β-catenin–TCF signaling depending on receptor context. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Neiwiadomski P, Rohatgi R (2015) Measuring expression levels of endogenous Gli genes by immunoblotting and Real-Time PCR. In: Hedgehog signaling protocols. Natalie A Riobo Springer Protocols, pp 81–93 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.