Abstract

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) has become a powerful alternative to polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for pathogen detection in clinical specimens and food matrices. Nontyphoidal Salmonella is a zoonotic pathogen of significant food and feed safety concern worldwide. The first study employing LAMP for the rapid detection of Salmonella was reported in 2005, 5 years after the invention of the LAMP technology in Japan. This review provides an overview of international efforts in the past decade on the development and application of Salmonella LAMP assays in a wide array of food and feed matrices. Recent progress in assay design, platform development, commercial application, and method validation is reviewed. Future perspectives toward more practical and wider applications of Salmonella LAMP assays in food and feed testing are discussed.

Keywords: : LAMP, Salmonella, detection, food, feed

Introduction

Nontyphoidal Salmonella is a Gram-negative zoonotic pathogen of substantial public health concern (WHO, 2017). In the 2015 World Health Organization (WHO) estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases, Salmonella ranked first among 22 bacterial, protozoal, and viral agents, reflecting its ubiquitous nature and the severity of illnesses (Kirk et al., 2015).

In the United States, over 75% of Salmonella outbreak-associated illnesses were broadly attributed across multiple food categories, including produce, eggs, chicken, pork, and beef (IFSAC 2015, 2017). Salmonella is also recognized as a major microbial hazard in animal food, which includes pet food, animal feed, and raw materials and ingredients (EFSA, 2008; FAO/WHO, 2015; FDA, 2017b). Multistate outbreaks of human salmonellosis linked to tainted pet food have been reported (CDC, 2018). Moreover, some Salmonella serovars are also major animal pathogens, for example, Salmonella Dublin in cattle and Salmonella Gallinarum in poultry, resulting in considerable loss in livestock production (Uzzau et al., 2000; FDA, 2013).

To prevent or reduce Salmonella outbreaks/illnesses from contaminated human or animal food, vigilant product testing and environmental monitoring for pathogens are critical, as underscored by the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) regulations on preventive controls (FDA, 2017a, b). This highlights the importance and urgency to develop rapid, reliable, and robust methods for Salmonella detection in a variety of food and feed matrices.

According to a recent report, the global food microbiology testing for pathogens totaled 280 million tests in 2016, a market valued at $1.8 billion (Ferguson, 2017). This represents an increase of 23.2% in testing volume over a 3-year period. Not surprisingly, Salmonella was the target in 43% of all tests performed, followed by Listeria and Listeria monocytogenes (41%), pathogenic Escherichia coli (14%), and Campylobacter (2%). A clear shift from traditional methods to rapid methods (e.g., polymerase chain reaction [PCR]) has been the trend observed for all four priority pathogens in the past two decades (Ferguson, 2017).

Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) (Notomi et al., 2000) is a novel nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) that has recently emerged as a powerful alternative to PCR for the rapid detection of various bacterial, fungal, parasitic, and viral agents (Niessen et al., 2013; Li et al., 2017). The first LAMP assay targeting Salmonella was reported in 2005 (Hara-Kudo et al., 2005). Since then, dozens of new Salmonella LAMP assays have been developed, leading to broad applications in human food and more recently in animal feed.

This review aims to capture international efforts in the past decade on the development and application of Salmonella LAMP assays in food and feed matrices. Future perspectives toward even more practical and wider applications of such assays in food and feed testing are discussed.

LAMP in a Nutshell

LAMP was invented in 2000 by a group of Japanese scientists (Notomi et al., 2000). The mechanism is based on the production of a stem-loop DNA structure during initiation steps, which serves as the starting material for second-stage LAMP cycling (refer to this site (Eiken Chemical Co. Ltd., 2005) for LAMP diagrams and animation). Unlike PCR (Table 1) that relies on thermal cycling to denature DNA and enable amplification by Taq DNA polymerase, LAMP uses a strand-displacing Bst DNA polymerase, which allows autocycling amplification under a constant temperature (60–65°C). This obviates the need for a sophisticated thermocycler. There are four to six specially designed LAMP primers (Nagamine et al., 2002), which target six to eight regions of the template DNA, compared to two primers in PCR (plus one or more probes in real-time PCR where amplification and detection occur simultaneously), ensuring a highly specific assay.

Table 1.

Technical Comparison Between Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification and Polymerase Chain Reaction (or Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction)

| Assay step | Component | LAMP | PCR or real-time PCR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplification | Enzyme | Bst DNA polymerase or equivalent ones | Taq DNA polymerase or equivalent ones |

| High strand displacement activity | Thermal cycling requirement (95°C/55°C/72°C) | ||

| Autocycling DNA amplification | |||

| Isothermal (60–65°C) | |||

| Primer | Four to six, two are longer ones (double length, ∼40 bp) | Two, plus one or more probes (real-time PCR) | |

| Other reagents | dNTP, buffer, Mg2+, water | dNTP, buffer, Mg2+, water | |

| Detection | Platform | Gel electrophoresis, turbidity, naked eye, colorimetric, fluorescence, bioluminescence, etc. | Gel electrophoresis, fluorescence (real-time PCR) |

LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification; PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

LAMP amplifies the target DNA rather efficiently, with 109 copies generated within an hour (Notomi et al., 2000). PCR or real-time PCR generally takes 1–2 h (although speedier versions are available now) and the amount of DNA produced is almost 20 times less (Mashooq et al., 2016). LAMP is highly tolerant to biological substances (Kaneko et al., 2007) with robustness demonstrated in both clinical and food applications (Francois et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2014). PCR, on the other hand, is generally susceptible to various assay inhibitors present in complex food or feed matrices (Abu Al-Soud and Radstrom, 2000; Maciorowski et al., 2005). LAMP is also more versatile in terms of amplicon detection methods, which include naked eye, colorimetry, turbidity, fluorescence, and bioluminescence, among many others (Zhang et al., 2014).

These attractive features of LAMP appear to align well with the WHO-outlined ASSURED (which stands for affordable, sensitive, specific, user friendly, rapid and robust, equipment free, and delivered to those who need it) criteria for an ideal diagnostic test (Mabey et al., 2004). As such, LAMP has become a mainstream isothermal NAAT used for low-cost point-of-care (POC) diagnostics and has reached a high level of maturity (Niemz et al., 2011; de Paz et al., 2014). In August 2016, WHO issued a recommendation for a TB-LAMP (LAMP for detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis) method as a rapid, accurate, and robust replacement test for smear microscopy to diagnose tuberculosis in peripheral health centers (WHO, 2016).

Applications of LAMP also extend to many other fields beyond in vitro diagnostics, as summarized in several recent reviews, such as species authentication and microbiological quality/safety assessment in meats (Kumar et al., 2017), and testing for genetically modified organisms (GMOs), allergens, pesticides, and drug resistance (Kundapur and Nema, 2016). A quick PubMed search using the term “loop-mediated isothermal amplification” returned >2100 articles, highlighting the great interest in LAMP within the scientific community.

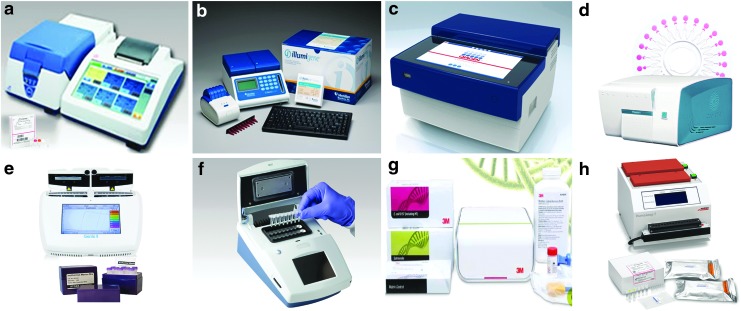

The popularity of LAMP is also reflected in the development of many commercially available systems (Fig. 1). Along with these exciting developments, the LAMP technology has been explored by researchers around the globe for the rapid, reliable, and robust detection of Salmonella in human food and animal food, which is the focus of this review.

FIG. 1.

LAMP commercial applications. (a) Loopamp Realtime Turbidimeter LA-500 and reagent kits (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan); (b) illumipro-10 and illumigene Molecular Diagnostic System (Meridian Bioscience, Inc., Cincinnati, OH); (c) ESEQuant TS2 (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands); (d) RTisochip-A (CapitalBio Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China); (e) Genie II and reagents (OptiGene Ltd., West Sussex, United Kingdom); (f) PDQ (ERBA Molecular, Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom); (g) 3M Molecular Detection System and assays (3M Food Safety, St. Paul, MN); (h) HumaLoop T and assays (HUMAN Diagnostics, Wiesbaden, Germany). LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification.

Salmonella LAMP Assay Development

Japanese scientists Hara-Kudo et al. (2005; Ohtsuka et al., 2005) have pioneered the field of LAMP detection for Salmonella in terms of initial assay development and food applications. In 2005, they described the first Salmonella LAMP assay and its application in artificially inoculated as well as naturally contaminated liquid eggs (Hara-Kudo et al., 2005; Ohtsuka et al., 2005). Since 2008, dozens of new Salmonella LAMP assays (i.e., with newly designed primers) have been developed, many of which were summarized in two excellent reviews published in 2013 (Niessen et al., 2013; Kokkinos et al., 2014).

Table 2 presents our collection (through regular PubMed and Web of Science searches and active literature gathering for ongoing research) of all Salmonella LAMP studies (n = 100) reported to date, some focusing on new assay developments (46% of studies) or new platform developments (34%), and others on applications in food (63%) or feed matrices (6%). Notably, scientists in China (32% of studies), United States (29%), Korea (8%), and Japan (5%) have contributed most to the advancements in this field.

Table 2.

A Chronological List of Salmonella Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification Assay Developments, Platform Developments, and Applications in Food and Feed

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Sensitivity in matrix | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study typea | Year | Countryb | Target organism | Target gene | Platform | Detection | Pure culture | PCR comparisonc | Inclusivity (No. of strains) | Exclusivity (No. of strains) | Matrix | Nature or spike | No enrichment | With enrichment | Agreement with culture or PCR | References |

| 1, 3 | 2005 | Japan | Salmonella spp. | invA | Real-time thermal cycler (ABI7700) | Real-time fluorescence (YO-PRO-1 iodide); naked eye (turbidity); gel electrophoresis | 2.2–18.5 CFU | 10 × | 100% (227) | 100% (62) | Liquid eggs | Spiked | 2.8 CFU/test (560 CFU/mL) | N/A | N/A | Hara-Kudo et al. (2005) |

| 3 | 2005 | Japan | Salmonella spp. | invA | Real-time thermal cycler (ABI7700) | Real-time fluorescence (YO-PRO-1 iodide); naked eye (turbidity) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Liquid eggs | Natural | N/A | 1–25 CFU/25 g | Superior than culture and PCR | Ohtsuka et al. (2005) |

| 1 | 2008 | China | Salmonella spp. | invA | Unspecified | Gel electrophoresis | 100 fg | 10 × | 100% (6) | 100% (14) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Wang et al. (2008b) |

| 1, 3 | 2008 | China | Salmonella spp. | invA | Unspecified | Gel electrophoresis; naked eye (turbidity) | 10 fg | N/A | 100% (8) | 100% (17) | Milk | Spiked | 102 CFU/mL | N/A | N/A | Zhu et al. (2008) |

| 1, 5 | 2008 | Japan | Salmonella O9 group | IS200/IS1351 gene | Loopamp realtime turbidimeter | Real-time turbidity | 12 CFU | 1000 × | 100% (128) | 100% (284) | Chicken cecal dropping | Spiked | N/A | 6.1 × 101–6.1 × 104 CFU/g | 100% Agreement with culture except for one in vivo spiked sample | Okamura et al. (2008) |

| 1, 3 | 2008 | China | Salmonella spp. | invA | Unspecified | Gel electrophoresis | N/A | 0.01 × | N/A | N/A | Raw milk | Spiked | >108 CFU/mL | N/A | N/A | Wang et al. (2008a) |

| 2, 3 | 2009 | China | Salmonella spp. | invA | In situ LAMP | Inverted fluorescence microscopy (Cy3) | 10 CFU | N/A | 100% (6) | 100% (2) | Eggshell | Spiked | 10 CFU | N/A | N/A | Ye et al.2009) |

| 1 | 2009 | Japan | Salmonella O4 group | rfbJ | Loopamp realtime turbidimeter | Real-time turbidity; gel electrophoresis | 100 CFU | 100 × | 100% (55) | 100% (74) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Okamura et al. (2009) |

| 3 | 2009 | Japan | Salmonella spp. | invA | Loopamp realtime turbidimeter | Real-time turbidity | N/A | N/A | 100% (54) | 100% (40) | Various food | Spiked | 102 CFU/mL | N/A | N/A | Ueda and Kuwabara (2009) |

| 1 | 2009 | China | Salmonella spp. | invA | EMA-LAMP | Naked eye (colorimetry-SYBR Green I) | 100 fg | >1000 × | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Lu et al. (2009) |

| 1, 3 | 2009 | China | Salmonella spp. | phoP | Heat block | Naked eye (turbidity and colorimetry-SYBR Green I); gel electrophoresis | 35 CFU | N/A | 100% (66) | 100% (73) | Minced pork and raw milk | Both | N/A | 35 CFU/250 mL | 100% Agreement with culture for spiked and natural samples | Li et al. (2009) |

| 1 | 2010 | Korea | Salmonella spp. | invA | Thermal cycler (GeneAmp 2700) | Gel electrophoresis | 0.21 CFU | 10,000 × , 10 × (Real-time PCR) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Ahn et al. (2010) |

| 3 | 2010 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | RT-LAMP | Naked eye (turbidity); gel electrophoresis | 500 CFU (gel electrophoresis), 0.05 CFU (naked eye) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Pork | Both | 106 CFU/25 g | 102 CFU/25 g | 100% Agreement with culture for pork carcass swab, more sensitive than culture in pork | Techathuvanan et al. (2010) |

| 3 | 2010 | China | Salmonella spp. | Unspecified | Water bath | Naked eye (colorimetry-SYBR Green I) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Raw meat and dairy product | Both | N/A | 102 CFU/mL | Superior than culture | He et al. (2010) |

| 1, 3 | 2010 | China | Salmonella Enteritidis | sdfI | Water bath | Naked eye (turbidity and colorimetry-SYBR Green I); gel electrophoresis | 4 CFU | 1 × (Real-time PCR) | 100% (5) | 100% (8) | Pork and chicken | Natural | N/A | N/A | 100% Agreement with real-time PCR | Yang et al. (2010) |

| 1 | 2010 | China | Salmonella spp. | invA | Water bath, heat block | Naked eye (colorimetry and fluorescence-SYBR Green I); gel electrophoresis | 100 CFU or 1 pg | 100 × | 97.8% (225) | 100% (28) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Zhao et al. (2010) |

| 3 | 2011 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | RT-LAMP | Naked eye (turbidity); gel electrophoresis | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Pork carcass and environment | Both | 106 CFU/500 mL | 101 CFU/500 mL | Same sensitivity as culture and rt-RT-PCR with or without enrichment | Techathuvanan et al. (2011) |

| 2, 3 | 2011 | China | Salmonella spp. | invA | In situ LAMP | Inverted fluorescence microscopy (Cy3) | 10 CFU | 50 × | N/A | 100% (1) | Eggshell | Spiked | N/A | 1 CFU/cm2 | N/A | Ye et al. (2011) |

| 1, 3 | 2011 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | PMA-LAMP on Loopamp realtime turbidimeter (LA-320C) | Real-time turbidity; naked eye (colorimetry-SYBR Green I) | 3.4–34 CFU | 100 × , 1 × (Real-time PCR) | 100% (28) | 100% (25) | Produce (cantaloupe, spinach, and tomato) | Spiked | 6.1 × 103–6.1 × 104 CFU/g | 40 CFU/g | Comparable to PMA-real-time PCR | Chen et al. (2011) |

| 1, 3 | 2011 | China | Salmonella spp., Shigella spp. | invA, ipaH | Multiplex LAMP-RFLP | Naked eye (turbidity); gel electrophoresis; RFLP | 100 fg | 10 × | 100% (8) | 100% (12) | Milk | Spiked | N/A | 5 CFU/10 mL | N/A | Shao et al. (2011) |

| 3 | 2011 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | Thermal cycler (Bio-Rad) | Naked eye (fluorescence-calcein) | 104 CFU | 0.01 × (Real-time PCR) | 99% (191) | 100% (48) | Produce | Spiked | N/A | 2 CFU/25 g | 100% Agreement with BAM, real-time PCR, and rt-RT-PCR | Zhang et al. (2011) |

| 1, 2 | 2011 | United States | Salmonella spp. and five other waterborne pathogens | invA, phoB | Microfluidic chip and film heater, real-time thermal cycler (Opticon) | CCD camera; real-time fluorescence (SYTO-82) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Ahmad et al. (2011) |

| 1, 2, 3 | 2011 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | Handheld device with assimilating probes | Real-time fluorescence (FAM) | 76 fg | N/A | N/A | N/A | Chicken | Both | 25 CFU | N/A | Comparable to real-time PCR without enrichment; agreeable with PCR and culture in a natural sample after enrichment | Jenkins et al. (2011) |

| 1, 3 | 2012 | China | Salmonella spp. | fimY | Loopamp realtime turbidimeter (LA-320C) | Real-time turbidity; naked eye (colorimetry-SYBR Green I) | 13 CFU | 10 × | 100% (81) | 100% (20) | Deli meat (chicken, pork, beef, shrimp, and mutton) | Both | N/A | 6.3 × 103 CFU/5 g | 100% Agreement with culture, superior than PCR | Zhang et al. (2012b) |

| 1, 5 | 2012 | China | Salmonella spp. | fimY | Unspecified | Gel electrophoresis; naked eye (colorimetry-SYBR Green I) | 4.8–6 CFU | 10 × | 100% (86) | 100% (23) | Duck organ | Both | 6 CFU | N/A | 100% Agreement with culture, superior than PCR | Tang et al. (2012) |

| 3 | 2012 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | RT-LAMP | Gel electrophoresis | 5 × 104 CFU | N/A | N/A | N/A | Liquid whole eggs | Both | 108 CFU/25 mL | 100 CFU/25 mL | Higher sensitivity in culture | Techathuvanan and D'Souza (2012) |

| 2 | 2012 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | Microfluidic chip and heat block | Electrochemical reporter (methylene blue); gel electrophoresis | 16 CFU | N/A | N/A | 100% (2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Hsieh et al. (2012) |

| 1, 3 | 2012 | Iran | Salmonella serogroup D | prt (rfbS) | Thermal cycler (Veriti), water bath | Naked eye (turbidity); gel electrophoresis | 10 CFU | 10 × | 100% (5) | 100% (4) | Chicken meat | Spiked | N/A | 1–5 CFU/250 mL | Superior performance than PCR | Ravan and Yazdanparast (2012b) |

| 1, 3 | 2012 | China | Salmonella spp. | hisJ | Unspecified | Naked eye (turbidity and colorimetry-SYBR Green I); gel electrophoresis | 16 CFU | 10 × | 100% (79) | 100% (23) | Pork, chicken, and vegetable | Natural | N/A | N/A | 29 Out of 200 samples were positive by LAMP, 27 positive by PCR, and 34 positive by culture | Zhang et al. (2012a) |

| 2, 3 | 2012 | Iran | Salmonella serogroup D | prt (rfbS) | LAMP-ELISA | ELISA; gel electrophoresis | 4 CFU | 10 × | 100% (5) | 100% (4) | Meat | Spiked | 103 CFU/mL | 10 CFU/mL | Shorter enrichment needed compared to PCR-ELISA | Ravan and Yazdanparast (2012a) |

| 1, 3 | 2012 | China | Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Staphylococcus aureus | invA | Multiplex LAMP-sequencing | Naked eye (turbidity); gel electrophoresis | 10 fg | 10,000 × | 100% (14) | 100% (19) | Milk, pork, egg, and chicken | Natural | N/A | N/A | 100% Agreement with culture and PCR | Jiang et al. (2012) |

| 2 | 2012 | United States | Salmonella spp., Campylobacter jejuni, Shigella, Vibrio cholerae | invA, phoP | Microfluidic chip and chip cartridge | Real-time fluorescence (SYTO-82) | 10 CFU (invA), 100 CFU (phoP) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Tourlousse et al. (2012) |

| 6 | 2012 | Greece | Salmonella spp. | invA | Thermal cycler (MJ Mini) | Gel electrophoresis; naked eye (colorimetry and fluorescence) | N/A | N/A | 100% (50) | 100% (10) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Ziros et al. (2012) |

| 1, 3 | 2013 | China | Salmonella spp. | invA | Unspecified | Gel electrophoresis | N/A | N/A | 100% (7) | 100% (13) | Raw milk | Both | 6–9 CFU | N/A | Without enrichment, 89.58% concordance with ISO 6579, 100% concordance with enrichment | Wang and Wang (2013) |

| 3 | 2013 | Italy | Salmonella spp. | invA | 3M MDS (prototype) | Real-time bioluminescence | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Retail meat (fresh and prepared) | Natural | N/A | <0.3–2.1 MPN/g | 78.9% for LAMP and 90.5% for ISO 6579 | Bonardi et al. (2013) |

| 2, 3 | 2013 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | Noninstrumented nucleic acid amplification (NINA) device (Thermos bottle) | Endpoint fluorescence (FAM) | 92 fg | N/A | N/A | N/A | Milk | Spiked | 2.8 × 104 CFU/mL | 1.4 CFU/mL | N/A | Kubota et al. (2013) |

| 1, 2, 5 | 2013 | United States | Salmonella spp. | recF | IMED chip and E-DNA sensor | E-DNA sensor (methylene blue) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Whole blood of mice | Natural | 800 CFU/mL | N/A | N/A | Patterson et al. (2013) |

| 1, 3 | 2013 | Korea | Salmonella spp. | invA | OptiGene Genie II | Real-time fluorescence | 3.2 CFU | 100 × | 100% (56) | 100% (12) | Duck carcass | Both | 3.2 × 103 CFU/mL | 3.2 CFU/mL | 96% sensitivity compared to culture, while PCR had 52% sensitivity | Cho et al. (2013) |

| 2 | 2013 | United States | Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli O157, Listeria monocytogenes | invA | Microfluidic chip and heater | Real-time fluorescence (EvaGreen) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Duarte et al. (2013) |

| 3 | 2013 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | Loopamp realtime turbidimeter (LA-320C) | Real-time turbidity | 1 CFU | 100 × | 100% (33) | N/A | Shell egg | Spiked | 104 CFU/25 mL | 100 CFU/25 mL | Shorter enrichment needed compared to PCR | Yang et al. (2013) |

| 3, 4 | 2013 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | 3M MDS | Real-time bioluminescence | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Ground beef and wet dog food | Spiked | N/A | 0.72 CFU/375 g | No significant difference in the number of positive samples compared to USDA or FDA reference methods | Bird et al. (2013) |

| 6 | 2013 | Papua New Guinea | Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., V. cholerae | phoP | Loopamp endpoint turbidimeter | Naked eye (turbidity and colorimetry-HNB and SYBR Green I; endpoint turbidity | 48 CFU | 0.1 × (Real-time PCR) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Soli et al. (2013) |

| 1, 3 | 2014 | India | Salmonella Typhimurium | typh | Unspecified | Naked eye (turbidity and colorimetry-SYBR Green I); gel electrophoresis | 2 pg | 100 × | 100% (28) | 100% (28) | Chicken meat | Natural | N/A | N/A | 100% Agreement with culture and PCR | Kumar et al. (2014) |

| 3 | 2014 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | Loopamp realtime turbidimeter (LA-320C) | Real-time turbidity | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Meat, chicken, egg, peanut butter, and produce | Spiked | N/A | N/A | More robust than PCR or real-time PCR for food applications | Yang et al. (2014) |

| 2 | 2014 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | UDG-LAMP | Naked eye (colorimetry and fluorescence-calcein); gel electrophoresis | 4 × 104 CFU | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Hsieh et al. (2014) |

| 3 | 2014 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | Loopamp realtime turbidimeter (LA-500) | Real-time turbidity | N/A | N/A | 100% (100) | 100% (30) | Meat and produce | Spiked | N/A | 1 CFU/test portion | 100% Agreement | Bapanpally et al. (2014) |

| 6 | 2014 | South Africa | Salmonella spp., Listeria, E. coli O157:H7 | invA | 3M MDS | Real-time bioluminescence | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Wastewater and river water | Natural | N/A | N/A | 8 Samples positive by LAMP in contrast to 24 samples positive by PCR (different DNA extracts were used) | Loff et al. (2014) |

| 1 | 2014 | China | Salmonella spp., E. coli O157, Listeria, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Vibrio parahaemolyticus | invA | Unspecified | Unspecified | N/A | N/A | 100% (40) | 100% (22) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Deng et al. (2014) |

| 3, 4 | 2014 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | 3M MDS | Real-time bioluminescence | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Ground beef and wet dog food | Spiked | N/A | 0.72 CFU/375 g | No significant difference in the number of positive samples compared to USDA or FDA reference methods | Bird et al. (2014) |

| 1, 5 | 2014 | China | Salmonella spp. | bcfD | Loopamp realtime turbidimeter (LA-500) | Real-time turbidity; gel electrophoresis | 5 CFU | 10 × | 100% (44) | 100% (9) | Chicken feces | Both | 5 × 103 CFU/g | N/A | N/A | Zhuang et al. (2014) |

| 2 | 2015 | United States | Salmonella spp., Ralstonia solanacearum | invA | Duplex LAMP on real-time thermal cycler (iQ5) | Real-time fluorescence (FAM and TAMRA) | 500 fg (98 CFU) singleplex and 50 pg (9.8 × 103 CFU) duplex | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Kubota and Jenkins (2015) |

| 1, 2 | 2015 | Malaysia | Salmonella spp. | fadA | Microfluidic CD and heater | Naked eye (colorimetry-SYBR Green I); electrochemical sensor-SYBR Green I | 6.25 pg, 85 CFU | 100 × | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Uddin et al. (2015) |

| 2, 3 | 2015 | Denmark | Salmonella spp. | invA | Microfluidic chip and heater | Real-time fluorescence (SYTO-62); gel electrophoresis | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Pork | Spiked | 50 CFU/test | N/A | Similar sensitivity as conventional PCR | Sun et al. (2015) |

| 3 | 2015 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | Loopamp realtime turbidimeter (LA-320C) | Real-time turbidity | 1.8–4 CFU | 1–10 × (Real-time PCR) | 100% (151) | 100% (27) | Produce (cantaloupe, pepper, lettuce, sprout, and tomato) | Spiked | 104–106 CFU/25 g | 1.1–2.9 CFU/25 g | For several serovars, real-time PCR required higher cell concentration or longer enrichment time | Yang et al. (2015) |

| 1, 3 | 2015 | Thailand | Salmonella spp. | stn | Unspecified | Naked eye (turbidity and colorimetry-SYBR Green I); gel electrophoresis | 5 fg, 1 CFU | N/A | 100% (102) | 100% (57) | Pork, chicken, and vegetables | Both | 220 CFU/g | 2 CFU/g | 100% Agreement with BAM culture | Srisawat and Panbangred (2015) |

| 6 | 2015 | United States | Salmonella spp., L. monocytogenes, S. aureus, STEC, Streptococcus agalactiae | invA | Real-time thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems StepOne) | Real-time fluorescence | 1 pg | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Wang et al. (2015a) |

| 1, 3 | 2015 | China | Salmonella spp., Salmonella Choleraesuis, Salmonella Enteritidis, and Salmonella Typhimurium | invE, fliC, lygD, STM4495 | Thermal cycler (Whatman Biometra UNO II) | Gel electrophoresis; naked eye (fluorescence-SYRR Green) | 13.3–20 CFU/mL | 10–100 × | 100% (3) | 100% (7) | Pork | Spiked | 16.7–26.7 CFU/mL | N/A | N/A | Chen et al. (2015) |

| 2 | 2015 | United States | Salmonella spp., E. coli, viruses, human sequences | invA | LAMP-PiBA | Optical detection of PiBA using a cell phone | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | DuVall et al. (2015) |

| 3 | 2015 | Singapore | Salmonella spp. | invA | 3M MDS | Real-time bioluminescence | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Duck wing, mung bean sprout, and fishball | Both | N/A | 100 CFU/25 g | 20% Sensitivity in spiked samples, 91% sensitivity in natural samples | Lim et al. (2015) |

| 3 | 2015 | Greece | Salmonella spp., L. monocytogenes | invA | Real-time thermal cycler (Roche LightCycler Nano) | Real-time fluorescence; gel electrophoresis; naked eye (fluorescence-SYBR Green I) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 100% (3) | RTE produce | Spiked | 2 × 104–1 × 107 CFU/g | 1–3 CFU/g | N/A | Birmpa et al. (2015a) |

| 3 | 2015 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | Real-time thermal cycler (MJ DNA Engine Opticon 2) | Real-time fluorescence (Midori Green); endpoint turbidity; gel electrophoresis | 4 CFU | N/A | N/A | N/A | Lettuce | Spiked | 4 CFU/g (10 CFU/reaction) | N/A | N/A | Wu and Levin (2015) |

| 2, 3 | 2015 | Greece | Salmonella spp., L. monocytogenes, adenovirus | invA | Custom-made LAMP platform | Real-time fluorescence; gel electrophoresis; naked eye (fluorescence-SYBR Green I) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | RTE produce | Spiked | 106–107 CFU/g | N/A | N/A | Birmpa et al. (2015b) |

| 6 | 2015 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | Real-time thermal cycler (MJ DNA Engine Opticon 2) | Real-time fluorescence (Midori Green); gel electrophoresis | 7 CFU | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Wu et al. (2015a) |

| 3 | 2015 | China | Salmonella spp. | invA | EMA-LAMP and PMA-LAMP on real-time thermal cycler (MJ DNA Engine Opticon 2) | Real-time fluorescence (Midori Green); endpoint turbidity; gel electrophoresis | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Lettuce | Spiked | 25 CFU/50 g (6 CFU/reaction) | N/A | N/A | Wu et al. (2015b) |

| 4 | 2015 | United Kingdom | Salmonella spp. | invA | Duplex LAMP on OptiGene Genie II | Real-time fluorescence | 3.3 × 104 CFU | N/A | N/A | N/A | Animal feed ingredient | Both | N/A | N/A | 100% Agreement with ISO 6579:2002 | D'Agostino et al. (2015) |

| 6 | 2015 | Poland | Salmonella spp. | invA | Unspecified | Gel electrophoresis | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Futoma-Koloch et al. (2015) |

| 1, 3 | 2015 | China | Salmonella spp., Shigella spp. | invA | Loopamp realtime turbidimeter (LA-320C) | Real-time fluorescence (HEX); naked eye (colorimetry-calcein); gel electrophoresis | 125 fg | 100 × , 10 × (Real-time PCR) | 100% (15) | 100% (39) | Milk | Spiked | 3.2 × 102 CFU/mL | N/A | 10 × (Real-time PCR), 100 × (PCR) | Wang et al. (2015c) |

| 1, 2 | 2016 | Korea | Salmonella spp., E. coli O157:H7, V. parahaemolyticus | serA | Microfluidic device (centrifugal) and lab oven | Naked eye (EBT); UV-Vis spectrophotometry | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Oh et al. (2016b) |

| 1 | 2016 | China | Salmonella spp., L. monocytogenes | invA | Unspecified | Naked eye (colorimetry and fluorescence); gel electrophoresis | 200 CFU | 100 × | 100% (4) | 100% (7) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Xiong et al. (2016) |

| 2, 3 | 2016 | Canada | Salmonella Enteritidis | sdfI | LAMP-SERS | SERS; gel electrophoresis | 0.132 CFU | 100 × | 100% (4) | 100% (5) | Milk | Spiked | 6 × 103 CFU/mL | N/A | N/A | Draz and Lu (2016) |

| 1, 3 | 2016 | China | Salmonella spp. | gene62181533 | Unspecified | Naked eye (turbidity and colorimetry-calcein); gel electrophoresis | 1.586 CFU, 11.52 fg | 100–10,000 × | 100% (32) | 100% (25) | Milk and meat | Both | N/A | 0.81 CFU/mL | For spiked samples, similar to culture methods; for natural samples, 100% agreement with culture and PCR | Li et al. (2016) |

| 1, 5 | 2016 | China | Salmonella Enteritidis, Salmonella Gallinarum | sefA | Loopamp realtime turbidimeter (LA-500) | Real-time turbidity; gel electrophoresis | 4 CFU | 10 × | 100% (163) | 100% (14) | Chicken feces | Spiked | 400 CFU | N/A | More sensitive than culture, but statistically insignificant | Gong et al. (2016) |

| 2 | 2016 | Spain | Salmonella spp., bovine species | invA | In-disc LAMP (iD-LAMP) | Naked eye (turbidity-direct and PEI); real-time colorimetry-HNB | 5 CFU | N/A | 100% (7) | 100% (4) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1 × (Conventional LAMP) | Santiago-Felipe et al. (2016) |

| 1, 2, 3 | 2016 | Korea | Salmonella spp., E. coli O157:H7, L. monocytogenes, V. parahaemolyticus | invA | Microfluidic device (centrifugal) and miniaturized rotary instrument with heat blocks | Naked eye (colorimetry-EBT); UV-Vis spectrophotometry | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Milk | Spiked | N/A | N/A | N/A | Oh et al. (2016a) |

| 1, 2, 3 | 2016 | Malaysia | Salmonella spp. | invA | Microfluidic CD and hot air gun | Naked eye (colorimetry-SYBR Green I) | 12.5 pg | N/A | N/A | 100% (6) | Tomato | Spiked | 3.4 × 104 CFU/mL | N/A | 100 × (PCR), 1 × (conventional LAMP) | Sayad et al. (2016) |

| 2 | 2016 | China | Salmonella spp., Bacillus cereus, E. coli, Vibrio fluvialis, V. parahaemolyticus | invA | Microfluidic chip (SlipChip) and custom heater | Naked eye (fluorescence-calcein); CCD camera; inverted fluorescence microscope; gel electrophoresis | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Xia et al. (2016) |

| 1, 2, 3, 4 | 2016 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | 3M MDS | Real-time bioluminescence | 36 CFU | N/A | 100% (151) | 100% (27) | Food and feed | Spiked | 104–106 CFU/25 g | 1–3 CFU/25 g | N/A | Yang et al. (2016) |

| 3 | 2016 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | 3M MDS | Real-time bioluminescence | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Ground beef and peanut butter | Spiked | N/A | 0.67 CFU/325 g | No significant difference in the number of positive samples compared to USDA or FDA reference methods | Bird et al. (2016) |

| 1, 5 | 2016 | India | Salmonella spp. | invA | Real-time thermal cycler (Agilent Mx3000P) | Real-time fluorescence; naked eye (turbidity, colorimetry, and fluorescence-SYBR Green I) | 10 CFU | 10 × (Real-time PCR) | 100% (12) | 100% (15) | Fecal sample | Natural | N/A | N/A | Higher sensitivity than real-time PCR, but statistically insignificant | Mashooq et al. (2016) |

| 3 | 2016 | Poland | Salmonella spp. | invA | 3M MDS | Real-time bioluminescence | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Various food | Natural | N/A | N/A | 100% Agreement with ISO culture method | Sarowska et al. (2016) |

| 4 | 2016 | United Kingdom | Salmonella spp. | invA | Duplex LAMP on OptiGene Genie II | Real-time fluorescence | N/A | N/A | 99% (100) | 100% (30) | Animal feed ingredient (soya meal) | Spiked | N/A | 1 CFU/100 g | Full agreement (RLOD of 1) with ISO 6579 culture method | D'Agostino et al. (2016) |

| 3 | 2016 | Malaysia | Salmonella spp. | invA | 3M MDS | Real-time bioluminescence | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Poultry and processing environment | Natural | N/A | N/A | Substantial agreement with ISO culture method | Abirami et al. (2016) |

| 2 | 2017 | China | Salmonella spp., E. coli, L. monocytogenes, P. aeruginosa, V. parahaemolyticus | invA | Colony LAMP | Naked eye (colorimetry-SYBR Green I); gel electrophoresis | 100 CFU | 100–1000 × | 100% (15) | 100% (101) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yan et al. (2017) |

| 1, 3 | 2017 | Korea | Salmonella spp. | invA | PMA-LAMP on OptiGene Genie II | Real-time fluorescence | 80 CFU | 10 × | 100% (140) | 100% (27) | Chicken carcass rinse | Spiked | 1 × 103 CFU/mL | N/A | N/A | Youn et al. (2017) |

| 2, 5 | 2017 | China | Salmonella spp., E. coli, Proteus hauseri, V. parahaemolyticus | invA | In-gel LAMP (gLAMP) | Inverted fluorescence microscopy-calcein | 2 CFU/μL | N/A | N/A | 100% (3) | Human serum | Spiked | 1.3 × 104 CFU/mL | N/A | N/A | Chen et al. (2017) |

| 1, 2 | 2017 | Korea | Salmonella spp., E. coli O157:H7, S. aureus | invE | CMOS integrated system | Real-time photon count-HNB; gel electrophoresis | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Wang et al. (2017) |

| 6 | 2017 | China | Salmonella spp., V. parahaemolyticus | bcfD | Duplex LAMP | Real-time fluorescence | 20 pg | 1 × | 100% (7) | 100% (12) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Liu et al. (2017) |

| 1, 2, 3 | 2017 | China | Salmonella spp. | invA | DNAzyme LAMP (dLAMP) | Naked eye (colorimetry-DNAzyme); gel electrophoresis | 0.5 pg | N/A | N/A | 100% (2) | Pork | Spiked | N/A | N/A | N/A | Zhu et al. (2017) |

| 3 | 2017 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | 3M MDS | Real-time bioluminescence | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Egg products (20 types) | Spiked | N/A | 1.63–4.18 CFU/25 g | Complete agreement with BAM culture and ANSR | Hu et al. (2017) |

| 2, 3 | 2017 | Korea | Salmonella spp., V. parahaemolyticus | invA | Integrated rotary microfluidic system | Laternal flow strip | 50 CFU | N/A | N/A | N/A | Milk | Spiked | 104 CFU/mL | N/A | N/A | Park et al. (2017) |

| 1, 2, 3 | 2017 | China | Salmonella spp. | siiA | LAMP-LFD | LFD; gel electrophoresis | 7.4 × 10−3 CFU | 100 × | 100% (21) | 100% (31) | Powdered infant formula | Spiked | 2.2 CFU/g | N/A | 100% Accuracy | Zhao et al. (2017) |

| 2 | 2017 | Korea | Salmonella spp., E. coli O157:H7, V. parahaemolyticus | invA | Microfluidic device (centrifugal) and lab oven | Naked eye (colorimetry-EBT); RGB-based image processing | 500 CFU | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Seo et al. (2017) |

| 1, 3 | 2017 | Portugal | Salmonella spp., Salmonella Enteritidis, Salmonella Typhimurium | invA, safA, STM4497 | Real-time thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems StepOne) | Real-time fluorescence (Midori Green) | 0.32 ng (5.6 ng for safA) | 10 × (0.1 × for safA; real-time PCR) | 100% (12) | 100% (12) | Poultry and eggs | Spiked | N/A | 4–10 CFU/25 g | >97% Agreement with culture | Garrido-Maestu et al. (2017b) |

| 2, 3 | 2017 | Portugal | Salmonella spp. | invA | Microfluidic chip and incubator | Naked eye (colorimetry-AuNP); gel electrophoresis | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Chicken, turkey, and eggs | Spiked | N/A | 10 CFU/25 g | 100% Agreement with culture | Garrido-Maestu et al. (2017a) |

| 4 | 2018 | United States | Salmonella spp. | invA | OptiGene Genie II, loopamp realtime turbidimeter (LA-500) | Real-time fluorescence; real-time turbidity | 1.3–28 CFU | 1 × (Real-time PCR) | 100% (247) | 100% (53) | Animal feed and pet food | Spiked | N/A | 0.0062 MPN/g | Combined RLOD of 0.61 | Domesle et al. (2018) |

| 2 | 2018 | China | Salmonella spp., P. aeruginosa, Streptococcus iniae, Vibrio alginolyticus, V. parahaemolyticus, Vibrio vulnificus | invA | Microfluidic device (hand-powered centrifugal) and pocket warmers | Real-time fluorescence; gel electrophoresis | 2 × 104 CFU/μL | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Zhang et al. (2018) |

| 1, 2, 3 | 2018 | Malaysia | Salmonella spp., E. coli, V. cholerae | Unspecified | Microfluidic device (centrifugal) | Naked eye (colorimetry-calcein) | N/A | 100 × | 100% (8) | 100% (20) | Chicken meat | Spiked | 30 fg/μL | N/A | N/A | Sayad et al. (2018) |

| 1, 3 | 2018 | United States | Salmonella Enteritidis | prot6E | OptiGene Genie III | Naked eye (colorimetry-calcein) | 1.2–12 CFU | 1 × | 97.4% (114) | 100% (69) | Egg products (22 types) | Spiked | N/A | 1–5 CFU/25 g | 100% Agreement with BAM and real-time PCR | Hu et al. (2018) |

| 2, 3 | 2018 | Greece | Salmonella spp. | invA | Integrated micro-nano-bio acoustic system | Surface acoustic wave sensor; gel electrophoresis | 2 CFU | N/A | N/A | N/A | Milk | Spiked | N/A | 1 CFU/25 mL | N/A | Papadakis et al. (2018) |

| 1, 3 | 2018 | China | Salmonella spp. | invA | PMA-LAMP on heat block, real-time thermal cycler (CFX96) | Naked eye (colorimetry-calcein); real-time fluorescence (calcein) | 1.6 CFU | 1 × (Real-time PCR) | 100% (3) | 100% (28) | Eggs, tomato, cucumber, lettuce, dried squid, skim milk powder, and meat | Both | 6.3×103 CFU/mL | 6.3×101 CFU/mL | 100% Agreement with BAM and real-time PCR | Fang et al. (2018) |

Studies focusing on assay development (1), platform development (2), application in food (3), application in feed (4), application in clinical samples (5), and other developments/applications (6).

When authors were from multiple countries, only the corresponding author's country is listed.

By default, the sensitivity (limit of detection) comparison was made to PCR unless specified otherwise.

ANSR, amplified nucleic single temperature reaction; AuNP, gold nanoparticle; BAM, FDA's Bacteriological Analytical Manual; CCD, charge-coupled device; CFU, colony-forming unit; CMOS, Complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor; EBT, Eriochrome Black T; E-DNA, Electrochemical DNA; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; EMA-LAMP, ethidium monoazide loop-mediated isothermal amplification; HNB, hydroxy naphthol blue; IMED, integrated microfluidic electrochemical DNA; LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification; LFD, lateral flow dipstick; MDS, Molecular Detection System; MPN, most probable number; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PEI, polyethylenimine; PiBA, product-inhibited bead aggregation; PMA, propidium monoazide; RFLP, restriction fragment length polymorphism; RGB, red green blue; RLOD, relative level of detection; RTE, ready to eat; RT-LAMP, reverse transcriptase-LAMP; rt-RT-PCR, real-time reverse transcriptase PCR; SERS, surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy; STEC, Shiga toxin–producing E. coli; UDG-LAMP, Uracil-DNA-glycosylase-supplemented LAMP; UV-Vis, ultraviolet and visible.

Primer design

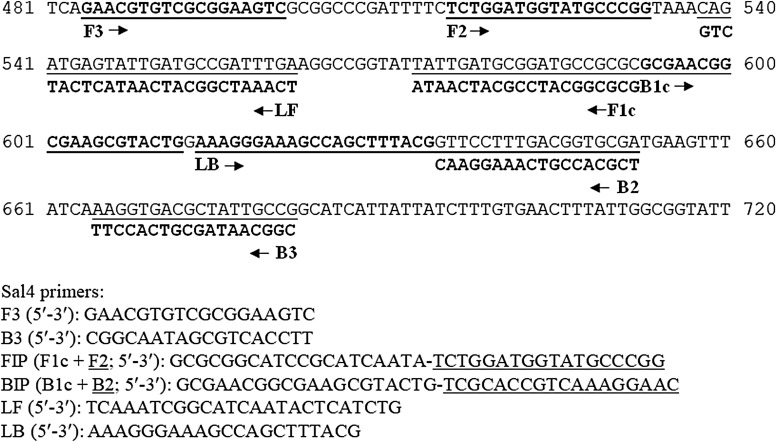

LAMP primers are commonly designed using the free web-based PrimerExplorer V4 software (V5 is available as of October 2016; http://primerexplorer.jp/e; Fujitsu Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The LAMP Designer software (PREMIER Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA) has been developed to serve a similar purpose. Each LAMP primer set contains four primers, two inner primers (FIP, forward inner primer; BIP, backward inner primer) and two outer primers (F3; B3). The inner primers FIP/BIP consist of complementary sequences of F1c/B1c and F2/B2 regions (Eiken Chemical Co. Ltd., 2009).

In earlier Salmonella LAMP studies, a TTTT linker was often added to connect F1c and F2 or B1c and B2 (Wang et al., 2008a; Lu et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2012). It is now common practice for Salmonella LAMP assays to incorporate two loop primers (LF, loop forward; LB, loop backward) to accelerate the reaction (Nagamine et al., 2002). Figure 2 illustrates the positions of these primers (or components of FIP/BIP) on the target gene, invA, which we used for a Salmonella LAMP assay (Yang et al., 2016).

FIG. 2.

A sequence alignment to illustrate the positions of six LAMP primers (F3, B3, FIP, BIP, LF, and LB) on the target gene. Partial nucleotide sequence of the Salmonella invasion gene invA (GenBank accession No. M90846) is shown, which was the target gene used to design our Salmonella LAMP assay (Yang et al., 2016). F3 and B3 are the forward and backward outer primers, respectively. FIP/BIP consists of complementary sequences of F1c/B1c and F2/B2 regions. BIP, backward inner primer; FIP, forward inner primer; LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification; LB, loop backward; LF, loop forward.

The invA gene is the most frequently targeted gene for designing LAMP primers for Salmonella spp. (74% of articles in Table 2). This gene is 2176 bp long in Salmonella Typhimurium (GenBank accession No. M90846) (Galan et al., 1992). A closer examination of the regions (5′ end of F3 and 3′ end of B3) covered by the primers designed by Hara-Kudo et al. (2005) and us (Yang et al., 2016) showed that they are in tandem with each other (225–468 and 484–682 bp), both overlapping with the region (371–655 bp) targeted by a set of widely used Salmonella invA PCR primers (Rahn et al., 1992). Sequence analysis showed that other sets of invA-based LAMP primers also overlapped with this PCR region (Chen et al., 2011), while still others targeted downstream regions (Wang et al., 2008b; Shao et al., 2011).

Other target genes, including bcfD and fimY, have also been used to design Salmonella LAMP primers (Table 2). Salmonella LAMP detection kits with proprietary primer information are available commercially, including Loopamp Salmonella Detection Kit (Eiken Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), 3M Molecular Detection Assay (MDA) 2—Salmonella (3M Food Safety, St. Paul, MN), SAS Molecular Tests Salmonella Detection Kit (SA Scientific Ltd., San Antonio, TX), and Ampli-LAMP Salmonella species (NovaZym, Poznań, Poland).

A few LAMP assays have been developed that target specific Salmonella serovars or serogroups (Table 2). For instance, sdfI (Yang et al., 2010) and prot6E (Hu et al., 2018) were used to design two separate LAMP assays for Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis, while typh was used to specifically detect Salmonella Typhimurium (Kumar et al., 2014). The sefA gene has been explored to design a LAMP assay for both Salmonella Enteritidis and Salmonella Gallinarum (Gong et al., 2016). An insertion element IS200/IS1351 gene was used to detect Salmonella O9 serogroup (Okamura et al., 2008), prt (rfbS) for serogroup D (i.e., O9) (Ravan and Yazdanparast 2012a, b), and rfbJ for O4 serogroup (Okamura et al., 2009).

Platform development

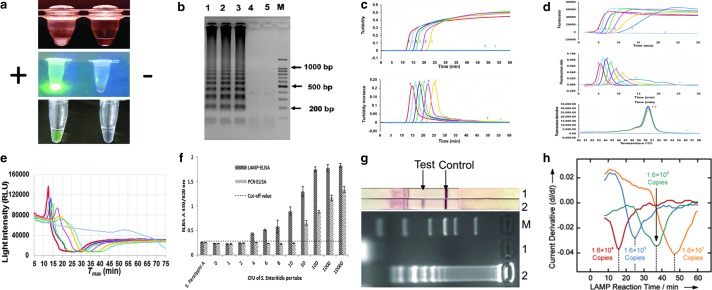

LAMP amplicons can be detected through multiple platforms/methods, as reviewed by Zhang et al. (2014), including naked eye, gel electrophoresis, colorimetry, turbidity, fluorescence, bioluminescence, electrochemical sensors/chips, lateral flow dipstick (LFD), and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Among them, detection by turbidity derived from magnesium pyrophosphate formation (white precipitate) has been the cornerstone of the LAMP technology (Mori et al., 2001).

Recently, we have seen explosive growth in the development and commercialization of LAMP-based microchips and microdevices for POC molecular diagnostics, many using optical and electrochemical methods (Safavieh et al., 2016). Some platforms are geared toward endpoint detection, while others focus on real-time detection. Given the large amount of DNA (10–20 μg/25 μL reaction mix) generated in a LAMP run (Kokkinos et al., 2014), platforms that allow closed-tube detection are highly recommended to prevent cross-contamination.

As shown in Table 2, various platforms/methods have been developed for or adopted by Salmonella LAMP assays over the years. Figure 3 illustrates several examples of the monitoring methods used. In earlier studies, Salmonella LAMP reactions were run in water baths, heat blocks, or thermal cyclers, and detected by naked eye and gel electrophoresis (Table 2). Naked eye monitoring was generally performed in three ways (Zhang et al., 2014): first by observing the white precipitate (turbidity) formed in a LAMP reaction tube (Fig. 3a, top), second by observing the color change postamplification after adding DNA-binding dyes such as SYBR Green I, either under normal air (colorimetry) or ultraviolet (fluorescence) (Fig. 3a, middle), and third by observing the color change or fluorescence in the LAMP reaction tube with metal indicators (e.g., calcein and hydroxy naphthol blue [HNB]) added during assay preparation (Fig. 3a, bottom). Gel electrophoresis was done postamplification by running an agarose gel and observing the characteristic ladder-like banding pattern of LAMP amplicons (Fig. 3b). Despite being widely used, concerns of introducing ambiguity (in the case of naked eye) or contamination (for gel electrophoresis) render these methods less desirable (Zhang et al., 2014).

FIG. 3.

Monitoring methods used to detect LAMP amplicons. (a) Naked eye observation based on white precipitate (Hara-Kudo et al., 2005), DNA dye (SYBR Green I) (Mashooq et al., 2016), and colorimetric indictor (calcein) (Li et al., 2016), respectively; (b) gel electrophoresis (Hara-Kudo et al., 2005); (c) real-time turbidity (Domesle et al., 2018); (d) real-time fluorescence (Domesle et al., 2018); (e) BART (Yang et al., 2016); (f) ELISA (Ravan and Yazdanparast, 2012); (g) LFD (Zhao et al., 2017); and (h) electrochemical method (Hsieh et al., 2012). BART, bioluminescent assay in real-time; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification; LFD, lateral flow dipstick. Figure reprinted from Hsieh K, et al. 2012, Angewandte Chemie International Edition. Reproduced by permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Real-time turbidity and real-time fluorescence have gained wide popularity as closed-tube or “one-pot” monitoring methods for Salmonella LAMP, especially with the recent availability of small, portable, robust, and user-friendly instruments (Fig. 1). As the LAMP reaction proceeds, turbidity or fluorescence readings are displayed in real time (amplification curves) and corresponding derivative values are plotted automatically at the completion of the run (derivative curves) (Fig. 3c, d). Results are interpreted based on whether these derivative values have reached thresholds set by the machine or user. While no modification to the LAMP reaction mix is needed for turbidity monitoring, to enable fluorescence detection, fluorophores are usually incorporated into the reaction mix or primers.

For turbidimetry-based Salmonella LAMP assays, Loopamp Realtime Turbidimeters LA-320 and LA-500 are commonly used platforms, whereas real-time PCR machines and Genie II have been used to develop several fluorescence-based Salmonella LAMP assays (Table 2). It is noteworthy that on the Genie II platform, an anneal step (from 98°C to 80°C with 0.05°C decrement per second) is included in each run to determine the annealing temperature of LAMP amplicons, which serves as an extra specificity check (Fig. 3d, bottom). Another closed-tube method used recently to monitor Salmonella LAMP reactions is based on bioluminescent assay in real time (BART) (Bird et al., 2013, 2014, 2016; Yang et al., 2016) (Fig. 3e) and performed in small platforms such as the 3M Molecular Detection System (MDS) (Fig. 1g). BART monitors the dynamic changes in the level of pyrophosphate produced in a LAMP reaction, which is converted to adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and utilized by firefly luciferase to emit light (Gandelman et al., 2010).

Several platforms also pair Salmonella LAMP assays with other novel detection methods downstream. Referred to as “open-tube” reactions, the process involves transferring LAMP amplicons to a second tube or platform for endpoint detection. Ravan and Yazdanparast (2012a) developed a LAMP-ELISA to detect Salmonella serogroup D by generating digoxigenin-labeled LAMP amplicons followed by hybridization to serogroup-specific oligonucleotide probes coated on a microtiter plate and ELISA readout (Fig. 3f). Draz and Lu (2016) combined LAMP with surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (LAMP-SERS) for the specific detection of Salmonella Enteritidis. To enable SERS detection, LAMP amplicons were hybridized with Raman-active Au-nanoprobes followed by nuclease digestion and washes (Draz and Lu, 2016).

More recently, Zhao et al. (2017) explored LFD as a new detection method for Salmonella LAMP (LAMP-LFD) (Fig. 3g). The LAMP FIP and BIP primers were labeled at the 5′ end with biotin and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), respectively. Gold nanoparticles conjugated with anti-FITC antibody were embedded in the conjugate pad during the LFD assembly, whereas streptavidin and anti-mouse secondary antibody were added on the detection region to form the test line and control line, respectively. LAMP amplicons were mixed with a running buffer followed by LFD immersion into the mixture for detection. Noticeably, these open-tube platforms require extensive postamplification manipulations, which are cumbersome, time-consuming, and prone to cross-contamination.

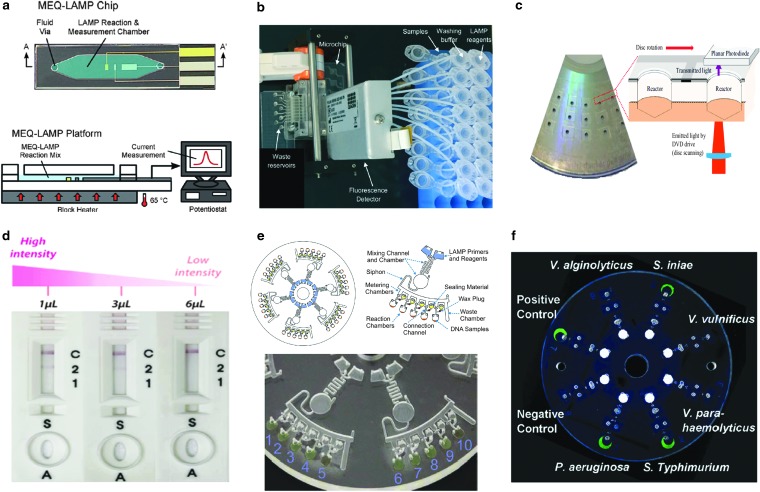

Recently, there have been many LAMP-based microfluidic devices designed for POC and food applications; some have used Salmonella as the model organism to show proof of concept (Table 2). For instance, Hsieh et al. (2012) designed a microfluidic electrochemical quantitative LAMP (MEQ-LAMP) chip (Fig. 4a) that used integrated electrodes to monitor the intercalation of DNA binding dye methylene blue redox reporter molecules into LAMP amplicons in real time. LAMP amplification was correlated with a decrease in the measured current signals (shown in Fig. 3h). Sun et al. (2015) developed an eight-chamber lab-on-a-chip (LOC) system (Fig. 4b) with integrated magnetic bead-based sample preparation and parallel LAMP amplification for Salmonella detection in food. After evaluating several DNA binding dyes, SYTO-62 was chosen for on-chip real-time fluorescence detection. Santiago-Felipe et al. (2016) designed a compact disc microreactor for LAMP (in-disc LAMP, iD-LAMP) (Fig. 4c) and tested Salmonella as proof-of-concept; the reaction was monitored through HNB colorimetry.

FIG. 4.

Microfluidic devices designed for LAMP-based detection of Salmonella. (a) MEQ-LAMP (Hsieh et al., 2012); (b) eight-chamber LOC with integrated sample preparation (Sun et al., 2015); (c) iD-LAMP (Santiago-Felipe et al., 2016); (d) integrated rotary microfluidic LAMP (Park et al., 2017); (e) centrifugal microfluidic LAMP (Sayad et al., 2018); and (f) hand-powered centrifugal microfluidic LAMP (Zhang et al., 2018). Figure reprinted in part from Hsieh K, et al. 2012, Angewandte Chemie International Edition. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc; and Sun Y, et al. 2015 and Zhang L, et al. 2018. Lab on a Chip. Reproduced with permission of The Royal Society of Chemistry. iD-LAMP, in-disc LAMP; LAMP, loop-mediated isothermal amplification; LOC, lab-on-a-chip; MEQ, microfluidic electrochemical quantitative.

Park et al. (2017) integrated DNA extraction, LAMP, and colorimetric lateral flow strip into a rotary microfluidic system (Fig. 4d) and demonstrated the parallel detection of Salmonella and Vibrio parahaemolyticus in milk. Very recently, Sayad et al. (2018) developed a centrifugal microfluidic platform (Fig. 4e) by incorporating a calcein-mediated colorimetric and wireless detection method for the parallel detection of E. coli, Salmonella, and Vibrio cholerae in food. Zhang et al. (2018) reported another centrifugal microfluidic platform (Fig. 4f) for parallel detection of six pathogens, Salmonella included, in a hand-powered, electricity-free format. The entire procedure, including nucleic acid purification, LAMP amplification, and visual detection of calcein-based fluorescence signals, is integrated into a microfluidic disc, achieving sample-to-result POC diagnostics (Zhang et al., 2018).

Assay optimization

Attempts to optimize LAMP reagent mix and/or reaction condition have been made in several Salmonella LAMP studies. Upon optimizing all components of a newly developed Salmonella LAMP assay, Chen et al. (2011) concluded that eliminating betaine from the LAMP reagent mix resulted in shorter time-to-positive results and stronger turbidity signals, that is, better amplification efficiency. In another study, the addition of betaine also contributed to a reduction in the amount of LAMP amplicons (Li et al., 2016), whereas Garrido-Maestu et al., (2017b) reported that with betaine, false positive results were generated from nontarget DNA as well as water. Instead, the addition of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at 7.5% was found to be favorable for LAMP amplification (Garrido-Maestu et al., 2017b).

Multiple Salmonella LAMP studies have confirmed that the incorporation of loop primers significantly decreased the time taken to obtain positive results, often by 20 min or more (Okamura et al., 2009; Zhuang et al., 2014; Mashooq et al., 2016). The reaction time for Salmonella LAMP assays ranges from 25 min to 2 h, and those requiring >60 min usually lacked loop primers (Ye et al., 2011). Running temperatures for the assays fall between 60°C and 65°C, except that 66°C was used in three studies (Gong et al., 2016; Park et al., 2017; Seo et al., 2017).

Assay evaluation

Specificity (inclusivity and exclusivity) and sensitivity (pure culture/DNA and comparison with PCR) evaluations of newly developed Salmonella LAMP assays are usually performed at the time of initial assay development. Unfortunately, these key parameters are missing for quite a few studies, especially those focusing on proof-of-concept POC diagnostics. As shown in Table 2, the number of strains tested for inclusivity (range, 3–247) and exclusivity (range, 1–284) varies vastly among the studies. Many studies did not meet the recommendations of AOAC International (AOAC, 2012) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO, 2016) on testing at least 100 Salmonella strains of different serovars for inclusivity and at least 30 competitive strains for exclusivity. Although strains belonging to S. enterica subsp. enterica (I) are well represented in inclusivity testing, those belonging to five other subspecies of S. enterica (i.e., salamae [II], arizonae [IIIa], diarizonae [IIIb], houtenae [IV], and indica [VI]) and Salmonella bongori are seldom tested. Nonetheless, almost all studies uniformly reported 100% inclusivity and 100% exclusivity for respective Salmonella LAMP assays developed, highlighting the highly specific nature of the LAMP technology.

Zhang et al. (2011) reported that one S. enterica subsp. arizonae strain CNM-247 and one S. bongori strain 95-0321 failed to be amplified by the Hara-Kudo's primer sets, neither did one S. enterica subsp. arizonae strain NCTC 7301 in another study (D'Agostino et al., 2016), while successful amplification of seven S. enterica subsp. arizonae strains along with 220 S. enterica subsp. enterica strains of 39 serovars were shown at the time of assay development (Hara-Kudo et al., 2005). Very recently, Domesle et al. (2018) evaluated the specificity of our invA-based Salmonella LAMP assay (Yang et al., 2016) (Fig. 2) using 300 bacterial strains (247 Salmonella strains of 185 serovars and 53 non-Salmonella strains) and demonstrated 100% specificity on both turbidimetry- and fluorescence-based platforms. Eleven S. enterica subsp. arizonae strains were tested and when compared to those belonging to other S. enterica subspecies, significantly longer time-to-positive results were required for these S. enterica subsp. arizonae strains (Domesle et al., 2018).

In pure-culture sensitivity testing, the reported limits of detection for all Salmonella LAMP assays ranged from 0.132 to 5 × 104 colony-forming unit (CFU) per reaction with several reporting a level much lower than 1 CFU (Table 2). Among studies where genomic DNA was tested, the limits of detection fell between 5 fg and 5.6 ng per reaction (Table 2). These are equivalent to a range from 1 CFU to 1 × 106 CFU per reaction, assuming one Salmonella genome weighs about 5 fg (Malorny et al., 2004). Numerous studies also compared the sensitivity between LAMP and PCR or real-time PCR (Table 2). The superior performance of LAMP (10- to 10,000-fold better sensitivity) over PCR was observed in the majority of studies, while equal (Yang et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2017) or lower sensitivity (0.01-fold) of LAMP to PCR (Wang et al., 2008a) was also reported. On the other hand, real-time PCR had limits of detection rather comparable (within 10-fold difference) to LAMP (Table 2).

Salmonella LAMP Assay Application

Since 2008, the application of Salmonella LAMP assays in human food has expanded to numerous food matrices, such as chicken, turkey, pork, beef, produce, and milk. More recently, Salmonella LAMP assays have also been applied in animal food, that is, pet food, animal feed, and raw materials and ingredients (D'Agostino et al., 2015; Bird et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2016). Below we present some challenges commonly associated with foodborne pathogen detection and the promise that LAMP offers and some actual applications.

Challenges and promises

Salmonella detection in human and animal food faces many of the same inherent challenges associated with general food testing for pathogens (Ge and Meng, 2009; Wang et al., 2013). Food and feed encompass many diverse and complex matrices, which presents a major hurdle toward developing effective sample preparation and testing strategies. Many matrices frequently harbor inhibitors to key reagents used in molecular assays, such as PCR enzymes, which greatly undermine the efficiency and utility of such assays. The presence of high levels of background flora in some matrices may also interfere with assay performance. Therefore, matrix-specific assay evaluations may be necessary. Furthermore, Salmonella is usually present in food or feed at much lower concentrations than those found in clinical specimens and the bacterial cells may be injured by the processes used to produce the food or feed (Ge and Meng, 2009).

To address these challenges, enrichment is commonly used to resuscitate injured Salmonella cells, increase the concentration of Salmonella, and dilute the effect of inhibitors and background flora on the assays (Wang et al., 2013). This is a general strategy applied to improve pathogen detection in food and feed, which is not limited to LAMP.

One major advantage of LAMP over PCR is the high tolerance to biological substances, such as whole blood and urine, commonly found in clinical specimens (Kaneko et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2014). This advantage also translates into food testing for pathogens as a means to overcome matrix effects. We designed a study to specifically evaluate the robustness of a Salmonella LAMP assay for food applications (Yang et al., 2014). Besides superior performance over PCR under abusive pH conditions, LAMP also showed greater tolerance to potential assay inhibitors (e.g., humic acid, soil, and culture media) than PCR. When food rinses, including meat juice, chicken rinse, egg homogenate, and produce homogenate, were added at 20% of the reaction mix, PCR amplifications were completely inhibited, but LAMP reactions were not (Yang et al., 2014). The study highlights the promise of LAMP as a robust and powerful method for Salmonella detection in various food matrices.

Application in food

As shown in Table 2, Salmonella LAMP assays have been applied in a wide variety of food matrices, including all the major food categories linked to Salmonella outbreak-associated illnesses, for example, produce, eggs, chicken, pork, and beef (IFSAC, 2015, 2017). The most widely adopted assay (in 27 studies) is the one developed by Hara-Kudo et al. (2005) followed by Chen et al. (2011) in 6 studies. While most studies used spiked samples, naturally contaminated samples have been examined. Platforms adopted for these assays are similar to those used in assay development as are the amplicon detection methods (Table 2).

Without enrichment, the reported sensitivity varies greatly, ranging from 2.2 CFU/g to 108 CFU/mL (Table 2). Enrichment (4 h to overnight) has been widely adopted and some studies reported probabilities of detection in lieu of limits of detection. The inclusion of an enrichment step clearly increased the ability of LAMP assays to detect Salmonella in food; many reported the successful detection of <1 CFU per test portion (in gram or mL) analyzed (Table 2).

Application in feed

Six recent studies have described the application of Salmonella LAMP assays in animal food matrices (Table 2). Notably, the closed-tube Genie II platform for real-time fluorescence detection of LAMP amplicon uses an extra anneal step, which has been explored recently for duplex detection of two targets by using the distinct annealing temperatures of the LAMP products, as described by Liu et al. (2017) for the detection of Salmonella and V. parahaemolyticus and by D'Agostino et al. (2015) for the detection of Salmonella and an internal amplification control (IAC). In the latter study, the IAC sequence was designed so that it could be amplified by the same primer set for Salmonella, but with increased G:C content, thereby increasing the annealing temperature of the IAC amplicon by 1.6°C. The assay sensitivity, however, was reduced by 1,000-fold with the IAC (D'Agostino et al., 2015). Nonetheless, the ability to incorporate an IAC is especially useful when applying Salmonella LAMP assays in animal food, since it takes longer time to reach positive results in animal food compared to human food, suggesting matrix effects are more pronounced in these matrices (Yang et al., 2016). As in human food applications, with enrichment, Salmonella LAMP assays could detect a few CFUs per animal food portion analyzed (Table 2).

Validation studies

Method validation is a critical step before a new method can be adopted for routine use. Despite growing applications of Salmonella LAMP assays in food and feed matrices (Table 2), limited effort has been put forth to validate the assay performance against well-established reference methods following international guidelines (AOAC, 2012; ISO, 2016). These validation studies, performed at single laboratory, independent laboratory, and collaborative study (interlaboratory) levels, present rigorous opportunities to test an assay's inclusivity/exclusivity, sensitivity, and probability of detection in a food or feed matrix (AOAC, 2012; ISO, 2016). For instance, in a dog food matrix study, bulk samples are inoculated at low (0.2–2 CFU/25 g) and high (2–10 CFU/25 g) concentrations, mixed well, and aged for at least 2 weeks to best mimic a natural contamination event (AOAC, 2012). The reference method and the alternative method are then applied to detect Salmonella using either a paired or unpaired study design (ISO, 2016).

In this context, validations of several commercially available Salmonella LAMP detection kits have been completed, including 3M MDA Salmonella in raw ground beef and wet dog food (Bird et al., 2013, 2014), 3M MDA 2—Salmonella in raw ground beef and creamy peanut butter (Bird et al., 2016), and SAS Molecular Tests Salmonella Detection Kit in ground beef, beef trim, ground turkey, chicken carcass rinses, bagged mixed lettuce, and fresh spinach (Bapanpally et al., 2014). Among them, 3M MDA 2—Salmonella has been approved for Official Method of Analysis (OMA) by AOAC International (OMA method No. 2016.01).

It is noteworthy that two Salmonella LAMP assays geared toward applications in animal food have moved forward with such validation efforts. D'Agostino et al. (2016) described the validation of a LAMP/ISO 6579-based method for analyzing soya meal (an animal feed ingredient) for the presence of Salmonella spp. through an interlaboratory trial. The alternative method achieved the same percentage correct identification (full agreement) as the reference method, demonstrating its suitability for adoption as a rapid method for identifying Salmonella in this matrix. In another study (Domesle et al., 2018), we reported the validation of our invA-based Salmonella LAMP assay in multiple animal feed and pet food items by closely following the guidelines (AOAC, 2012; FDA, 2015; ISO, 2016). Compared to the reference method, the relative levels of detection for all animal food items fell within the acceptability limits for an unpaired study (Domesle et al., 2018).

Future Perspectives

In this review, we summarized 100 articles published around the globe between 2005 and 2018 on the development and application of Salmonella LAMP assays in various food and feed matrices (Table 2). LAMP has clearly established itself as a powerful alternative to PCR for the rapid, reliable, and robust detection of Salmonella, with several assays already successfully validated through multilaboratory studies in specific food and feed matrices.

It is a high possibility that scientific and commercial advancements in the LAMP technology, in general, will propel and shape future developments in this field. This includes the development of new LAMP reagents and new platforms to further capitalize on the two most distinctive characteristics of LAMP, that is, rapidity and simplicity (Mori et al., 2013). Already, we have seen many recent developments in new LAMP reagents, particularly enzymes and master mixes, for example, Bst 2.0 and Bst 2.0 WarmStart DNA polymerases (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA), GspSSD and Tin DNA polymerases and isothermal master mixes (OptiGene Ltd., West Sussex, United Kingdom), and OmniAmp DNA polymerase and LavaLAMP master mixes (Lucigen Corporation, Middleton, WI), which offer better thermostability, higher amplification efficiency, and are thus more amenable to resource-limited and field conditions. Positive results may be obtained within 5 min using some of these reagents. Lyophilized LAMP reagents have been commercialized for some clinical diagnostic kits (Mori et al., 2013), a reagent format that may be adopted by Salmonella LAMP detection kits for food and feed in the future.

Multiplex LAMP assays are just beginning to be explored (Mayboroda et al., 2018), using release of quenching technology (Tanner et al., 2012), fluorogenic hybridization (Nyan and Swinson, 2015), endonuclease restriction (Wang et al., 2015), assimilating probes (Kubota and Jenkins, 2015), and annealing temperature differentiation (D'Agostino et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2017) to detect multiple targets in a single reaction tube. The latter two techniques have been applied in Salmonella (D'Agostino et al., 2015; Kubota and Jenkins, 2015; Liu et al., 2017). These differ in principle from parallel detection described for many POC microfluidic devices where LAMP reactions for multiple targets are carried out in separate chambers or wells simultaneously. Future developments in chemistries/strategies for multiplex LAMP assays will greatly advance the multiplex LAMP detection of Salmonella (multiple genes or pathogens).

Regarding new platform developments, closed-tube, “one-pot” platforms that allow rapid, sensitive, specific, and real-time amplification and detection in small, portable, robust, and user-friendly instruments will be the mainstream. The development and refinement of microfluidic devices (heat control, fluid manipulation, and monitoring method) will continue at a rather fast speed, focusing on full integration of sample preparation, amplification, and detection on one simple, small, user-friendly microdevice. Improvements in sample throughput and field amenability are also desired.

Special considerations should be given when adopting these new advancements in food and feed testing. In terms of assay development, there is currently a paucity of LAMP primers developed for specific Salmonella serovars other than Salmonella Enteritidis and Salmonella Typhimurium. LAMP assays for Salmonella serovars that are major animal pathogens are also scarce. Progresses in the areas of viable detection (Lu et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2011; Techathuvanan and D'Souza, 2012) and contamination prevention (Hsieh et al., 2014) have been made and further research is still needed. Simple and effective sample preparation methods, including DNA extraction and storage for field detection are in great demand. Further developments in noninstrumented nucleic acid amplification such as running the assays in a thermos (Kubota et al., 2013) or a pocket warmer (Zhang et al., 2018) will enable field-based food and agricultural diagnostics. Finally, there is an increasing need for matrix-specific validation of newly developed methods. Such validations should follow international guidelines before the methods can be adopted for routine use in food and feed testing.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or the U.S. Government. Reference to any commercial materials, equipment, or process does not in any way constitute approval, endorsement, or recommendation by the Food and Drug Administration.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Abirami N, Nidaullah H, Chuah LO, et al. Evaluation of commercial loop-mediated isothermal amplification based kit and ready-to-use plating system for detection of Salmonella in naturally contaminated poultry and their processing environment. Food Control 2016;70:74–78 [Google Scholar]

- Abu Al-Soud W, Radstrom P. Effects of amplification facilitators on diagnostic PCR in the presence of blood, feces, and meat. J Clin Microbiol 2000;38:4463–4470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad F, Seyrig G, Tourlousse DM, Stedtfeld RD, Tiedje JM, Hashsham SA. A CCD-based fluorescence imaging system for real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification-based rapid and sensitive detection of waterborne pathogens on microchips. Biomed Microdevices 2011;13:929–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn Y-C, Cho M-H, Yoon I-K, et al. Detection of Salmonella using the loop mediated isothermal amplification and real-time PCR. J Korean Chem Soc 2010;54:215–221 [Google Scholar]

- AOAC. AOAC INTERNATIONAL Methods Committee Guidelines for Validation of Microbiological Methods for Food and Environmental Surfaces. 2012. Available at: http://www.eoma.aoac.org/app_j.pdf Accessed March1, 2018

- Bapanpally C, Montier L, Khan S, Kasra A, Brunelle SL. SAS molecular tests Salmonella detection kit. Performance tested method 021202. J AOAC Int 2014;97:808–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird P, Fisher K, Boyle M, et al. Evaluation of 3M Molecular Detection Assay (MDA) Salmonella for the detection of Salmonella in selected foods: Collaborative study. J AOAC Int 2013;96:1325–1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird P, Fisher K, Boyle M, et al. Evaluation of modification of the 3M Molecular Detection Assay (MDA) Salmonella method (2013.09) for the detection of Salmonella in selected foods: Collaborative study. J AOAC Int 2014;97:1329–1342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird P, Flannery J, Crowley E, Agin JR, Goins D, Monteroso L. Evaluation of the 3M Molecular Detection Assay (MDA) 2—Salmonella for the detection of Salmonella spp. in select foods and environmental surfaces: Collaborative study, first action 2016.01. J AOAC Int 2016;99:980–997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmpa A, Kalogeropoulos K, Kokkinos P, Vantarakis A. Evaluation of two loop-mediated isothermal amplification methods for the detection of Salmonella Enteritidis and Listeria monocytogenes in artificially contaminated ready-to-eat fresh produce. Ital J Food Saf 2015a;4:5383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmpa A, Kouroupis G, Kalogeropoulos K, Kokkinos P, Kritsonis P, Vantarakis A. A loop-mediated isothermal amplification platform for the detection of foodborne pathogens. J Bioeng Biomed Sci 2015b;5:3 [Google Scholar]

- Bonardi S, Alpigiani I, Bacci C, Brindani F, Pongolini S. Comparison of an isothermal amplification and bioluminescence detection of DNA method and ISO 6579:2002 for the detection of Salmonella enterica serovars in retail meat samples. J Food Prot 2013;76:657–661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Reports of Selected Salmonella Outbreak Investigations. 2018. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/salmonella/outbreaks.html Accessed March1, 2018

- Chen C, Liu P, Zhao X, Du W, Feng XJ, Liu BF. A self-contained microfluidic in-gel loop-mediated isothermal amplification for multiplexed pathogen detection. Sens Actuators B Chem 2017;239:1–8 [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Wang F, Beaulieu JC, Stein RE, Ge B. Rapid detection of viable salmonellae in produce by coupling propidium monoazide with loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Appl Environ Microbiol 2011;77:4008–4016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Zhang K, Yin H, Li Q, Wang L, Liu Z. Detection of Salmonella and several common Salmonella serotypes in food by loop-mediated isothermal amplification method. Food Sci Human Wellness 2015;4:75–79 [Google Scholar]

- Cho AR, Dong HJ, Cho S. Rapid and sensitive detection of Salmonella spp. by using a loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay in duck carcass sample. Korean J Food Sci Anim Resour 2013;33:655–663 [Google Scholar]

- D'Agostino M, Diez-Valcarce M, Robles S, Losilla-Garcia B, Cook N. A loop-mediated isothermal amplification-based method for analysing animal feed for the presence of Salmonella. Food Anal Method 2015;8:2409–2416 [Google Scholar]

- D'Agostino M, Robles S, Hansen F, et al. Validation of a loop-mediated amplification/ISO 6579-based method for analysing soya meal for the presence of Salmonella enterica. Food Anal Method 2016;9:2979–2985 [Google Scholar]

- de Paz HD, Brotons P, Munoz-Almagro C. Molecular isothermal techniques for combating infectious diseases: Towards low-cost point-of-care diagnostics. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2014;14:827–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Ji LL, Li L, Li B, Su JY. Development and application of a novel nucleic amplification kit on detection of several pathogens. Appl Mech Mater 2014;618:293–297 [Google Scholar]

- Domesle KJ, Yang Q, Hammack TS, Ge B. Validation of a Salmonella loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay in animal food. Int J Food Microbiol 2018;264:63–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draz MS, Lu X. Development of a loop mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP)—surface enhanced raman spectroscopy (SERS) assay for the detection of Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis. Theranostics 2016;6:522–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte C, Salm E, Dorvel B, Reddy B, Jr., Bashir R. On-chip parallel detection of foodborne pathogens using loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Biomed Microdevices 2013;15:821–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuVall JA, Borba JC, Shafagati N, et al. Optical imaging of paramagnetic bead-DNA aggregation inhibition allows for low copy number detection of infectious pathogens. PLoS One 2015;10:e0129830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA. European Commission on Microbiological Risk Assessment in feedingstuffs for food-producing animals, Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Biological Hazards on a request from the Health and Consumer Protection Directorate General. EFSA J 2008;720:1–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiken Chemical Co. Ltd. The Principle of LAMP Method. 2005. Available at: http://loopamp.eiken.co.jp/e/lamp/principle.html Accessed March1, 2018

- Eiken Chemical Co. Ltd. A Guide to LAMP Primer Designing. 2009. Available at: https://primerexplorer.jp/e/v4_manual/pdf/PrimerExplorerV4_Manual_1.pdf Accessed March1, 2018

- Fang J, Wu Y, Qu D, et al. Propidium monoazide real time loop-mediated isothermal amplification for specific visualization of viable Salmonella in food. Lett Appl Microbiol 2018. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO/WHO. Executive Summary Report of the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Meeting on Hazards Associated with Animal Feed. 2015. Available at: http://www.fao.org/3/a-az851e.pdf Accessed March1, 2018

- FDA. Compliance Policy Guide Sec. 690.800 Salmonella in Food for Animals. 2013. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/iceci/compliancemanuals/compliancepolicyguidancemanual/ucm361105.pdf Accessed March1, 2018

- FDA. Guidelines for the Validation of Analytical Methods for the Detection of Microbial Pathogens in Foods and Feeds, 2nd ed. 2015. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/ScienceResearch/FieldScience/UCM298730 Accessed March1, 2018

- FDA. 21 CFR Part 117: Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Human Food. Available at: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=2dae3ed6aff60a1d08b2c1e418057788&mc=true&node=pt21.2.117&rgn=div5 Accessed June1, 2018

- FDA. 21 CFR Part 507: Current Good Manufacturing Practice, Hazard Analysis, and Risk-Based Preventive Controls for Food for Animals. Available at: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=2dae3ed6aff60a1d08b2c1e418057788&mc=true&node=pt21.6.507&rgn=div5 Accessed June1, 2018

- Ferguson BS. A look at the microbiology testing market. Food Safety Magazine 2017:14–15. Available at: https://www.foodsafetymagazine.com/magazine-archive1/februarymarch-2017/a-look-at-the-microbiology-testing-market/ Accessed March1, 2018

- Francois P, Tangomo M, Hibbs J, et al. Robustness of a loop-mediated isothermal amplification reaction for diagnostic applications. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2011;62:41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]