Abstract

Background

Recognising the lack of research on daytime drinking practices in areas with managed night-time economies (NTEs), this qualitative study explores the phenomena in the London Borough of Islington; a rapidly gentrifying area with a highly regulated night-time economy (NTE). The objectives were to (i) Characterise the daytime drinking spaces of the local alcohol environment and (ii) Theorise the ways in which these spaces, and the practices and performativities within them, are situated within broader social and economic trends.

Methods

Adopting a legitimate peripheral participation approach to data collection, 39 licensed premises were visited in Islington and on-site observations carried out between the hours of 12pm and 6pm using a semi-structured observation guide. Observations were written-up into detailed fieldnotes, uploaded to NVivo and subject to a thematic analysis.

Findings

The daytime on-premises alcohol environment was characterised by two main trends: the decline of traditional pubs and a proliferation of hybrid establishments in which alcohol was framed as part of a suite of attractions. The consumption trends that the latter exemplify are implicated in processes of micro-cultural production and ‘hipster capitalism’; and it is via this framing that we explore the way the diverse local drinking spaces were gendered and classed. Hybrid establishments have been regarded as positive in terms of public health, crime and safety. However, they could also help introduce drinking within times and contexts where it was not previously present.

Conclusion

The intersection of an expanding hipster habitus with Local Authority efforts to tackle ‘determined drunkenness’ create very particular challenges. The operating practices of hybrid venues may feed into current alcohol industry strategies of promoting ‘new moments’ in which consumers can drink. They blur the divisions between work and play and produce temporal and classed divisions of drinking.

Keywords: Qualitative, daytime drinking, London, Alcohol licensing, Hybrid establishments, Hipsters

Introduction

Faced with the decline of traditional industries and employment, many UK cities have sought to reinvent themselves as places of leisure (Roberts & Eldridge, 2009). In developing ‘night-time economies’ (NTEs) to revitalize inner city economies, the promotion and consumption of alcohol has been central (Lukas, 2008). At the same time, alcohol related harm is a major national health concern (WHO, 2014) and a contributor to problems of crime, safety, social order, injury and disease (Andrews et al., 2005; Haan et al., 1987). Historically, a tension exists in the UK between concerns over the social and health impacts of alcohol consumption and the economic role of alcohol (Jayne et al., 2010). Interventions that seek to balance economic and social impacts of alcohol are mainly enacted at the local level (Fitzgerald & Angus, 2015).

Currently, the most significant lever for modifying the availability of alcohol in the UK is through the licensing of alcohol outlets; a process administered by local licensing authorities – who in England have considerable leeway to tailor policies to their own environments (Egan et al., 2016; Martineau et al., 2013). Interventions at this scale include restricting what kind of places and during which hours alcohol can be sold and consumed (Egan et al., 2016). Overwhelmingly, such policies are formulated around spaces of the NTE, which are viewed as problematic and risky. Local authorities (LAs) have struggled to control night-time alcohol and entertainment spaces (Haan et al., 1987). NTE venues are contested spaces that are alcohol-fuelled, consumption driven and often characterised by social disorders and the clustering of young people engaged in heavy-drinking and public drunkenness (Hadfield, 2006; Hadfield et al., 2010). This is further complicated by the fact that attempts to manage NTE spaces are often at-odds with the culture of excess that remains a highly visible dimension of youth drinking cultures. Added to which, such efforts are typically subject to resistance from local businesses (Hadfield et al., 2010; Measham & Brain, 2005).

This focus on the NTE, both in policy and research, has not been matched by a sustained investigation of the daytime alcohol environment. In part, this may be because it is not perceived to have the same sense of danger, risk or excess (Hayward & Hobbs, 2007). And yet, the daytime alcohol environment is of interest because it is undergoing a period of intense change. The number of pubs in the UK is at its lowest level for a decade. The rate of closure of community pubs, the established venue for daytime drinking, is around 21 closures per week (Smithers, 2016). A recent national study of drinking practices in Britain found that nearly a fifth of all recorded ‘drinking occasions’ took place before 5pm. The noon till 6pm period marks the first half of a 12 hour escalation of alcohol related crimes that occurs in the UK on a daily basis, with approximately a tenth (on a weekend) or a fifth (weekday) of all alcohol related offences occurring within that initial six hour period (Ally et al., 2016). Daytime drinking has also been associated with occupational injury (the so-called ‘lunchtime effect’), impaired driving ability and disturbed nocturnal sleep (Camino Lópeza et al., 2011; Ebrahim et al., 2013; Horne et al., 2003; Institute of Alcohol Studies, 2014).

Furthermore, alcohol marketing and the media at times promote daytime drinking in the context of all-day drinking [for examples of this see (Bell, 2016; Delany, 2016; Ferguson & Richards, 2015)], with the implication that some of the problems experienced by the NTE begin in the afternoon and early evening. In which case, there is a need to examine how the spaces of the NTE operate during the daytime. This paper reports on the findings of a qualitative study exploring the local daytime alcohol environment in an urban locality with a large and challenging NTE.

Setting and policy context: The London Borough of Islington

Data for this study were collected in the London Borough of Islington. The Borough has over 1300 premises licenced to sell alcohol and one of the highest densities of pubs, bars, cafes and shops selling alcohol in London. The area is also characterised by high levels of social inequalities and alcohol related health harms (both chronic and acute) (London Borough of Islington, 2012). The Local Authority deploys a range of policies and interventions to try and manage its alcohol trade and, in particular, it’s NTE. These include encouragement of initiatives delivered in partnership with industry actors to promote what is sometimes referred to as responsible drinking and preferred managerial practices: e.g. ‘Best Bar None’ (see https://www.bbnuk.com), ‘Challenge 25’ (see https://www.challenge25.org) and ‘Pubwatch’ (see https://www.islington.gov.uk/business/best/support_networks/pubwatch).

They also include regulatory interventions, often involving the local alcohol licensing system. Notably, Islington operates a Cumulative Impact Policy (CIP). CIPs chiefly affect applications for new alcohol licenses within specific areas identified by the Local Authority as having particular alcohol problems linked to high alcohol outlet density. These areas are called ‘cumulative impact zones’ (CIZs) (Grace et al., 2014; Martineau et al., 2013). The policy is designed to give Licensing Authorities a stronger legal position should they want to reject applications for new licenses within CIZs. Previous research has suggested that CIPs have been used to discourage certain types of establishments, such as traditional pubs and bars, whilst encouraging other types of venue that appear to place less emphasis on the alcohol side of their business, such as coffee shops and restaurants (Egan et al., 2016; Grace et al., 2016). The CIP in Islington was developed in 2013 in response to concerns that the ”saturation” of on- and off-licence premises had reached a point where “the economic benefits of the night time economy [were] starting to be outweighed by the health impacts, loss of amenity and the costs of excessive alcohol consumption, crime and disorder”.(London Borough of Islington, 2012).

Islington is also a place of interest because it represents a very particular locality. Islington was the first area in London to be identified as being ‘gentrified’ and remains one of the focal points of these debates (Wilson et al., 2004). So much so, that it has been described as ‘super-gentrified’; and thereby in the grip of such change and inequality that mixing across the wealth and social class barriers is become increasingly difficult (Smith, 2006).

Islington has come to exemplify the socio-economic and cultural trends of gentrification. On the one-hand, it is known for its plush bars, restaurants and boutiques (Shaheen, 2013). On the other, poverty and inequality are intensifying in the area, with child poverty being particularly high. Increasingly, middle-income families can no longer afford to live in the area with soaring house prices and stagnating wages for middle and lower income earners (Penny et al., 2013). Its demographic make-up can be characterised as one of startling contrasts: with a transient young professional group sandwiched between poor families living in social housing and a very rich group of families occupying prime properties (Shaheen, 2013). It is generally these transient young professionals who frequent the plush bars and cafes, and who are described as ‘hipsters’ in accounts of new consumer practices in concentrated areas of rapidly gentrifying Western cities like London (Cumming, 2015; Schiermer, 2014).

Media and cultural accounts often associate ‘hipsters’ with urbanism and localism, and as aficionados of things such as neo-artisanal goods, architecture, urbanism, localism, folk music, and coffee. They are imagined and presented as iconic millennial figures who hold counter-mainstream tastes (Scott, 2017). Typically, the term is used to refer to young, white, educated and middle class individuals with left-leaning politics who tend to work in ‘creative industries’, cafés, bars, music or fashion stores (Schiermer, 2014). The term ‘hipster capitalism’ has been used to described the approaches to micro-entrepreneurial cultural production that these actors engage in (Scott, 2017) and which have helped define the boutique and independent consumption spaces of Islington, including establishments that serve alcohol (Shaheen, 2013). It is via this framing of ‘hipster capitalism’ (Scott, 2017) that we examine the daytime alcohol environment of Islington.

Methods

This paper reports on the findings of a qualitative study aiming to explore the daytime alcohol environment of a local area that has both a problematic NTE and a rapidly changing retail and consumption environment. The main objectives of the study were to (i) Characterise the daytime drinking spaces of Islington’s alcohol environment, and (ii) Theorise the ways in which these spaces, and the practices and performativities within them, are situated within broader social and political trends.

The daytime alcohol environment of Islington is the site of both a heavily regulated NTE and of burgeoning aspirational consumption. In order to examine this setting and the factors that shape it, we used a qualitative case study approach, concentrating our efforts on specific areas that have been identified as problematic in terms of NTE drinking spaces - designated cumulative impact zones (CIZs) – to explore how they function as daytime drinking establishments in the context of ‘hipster’ consumption practices.

In order to explore the daytime alcohol environment of Islington, we undertook a ‘legitimate peripheral participation’ approach (Lave & Wenger, 1991) to observations of licensed premises. This approach was selected to investigate the embodied experiences of different types of alcohol consumption in a range of drinking spaces and to examine how the materialities of specific sites shaped the alcohol environment (Jayne et al., 2010). This involved looking at licenced premises in terms of exterior appearance, physical layout, facilities, décor, and clientele behaviour. It also necessitated examining venue-specific materials such as menus, posters, advertisements, notices, and venue websites.

Sampling and observation of licensed premises

Since 2013, seven discrete areas in Islington have been made cumulative impact zones (CIZs); thus identifying them as problematic in terms of alcohol consumption and making them subject to more stringent licensing application processes. Given that these spaces had already been identified by the Local Authority, we concentrated our efforts on conducting observations within them. In this vein, we selected three (of the possible seven) CIZs that were geographically spread-out across the borough as observation sites. In addition to this, we also selected one area that had a high density of alcohol outlets but was not a designated CIZ. The inclusion of a non-CIZ area was intended to balance the sample and provide some indication as to whether the characteristics of the alcohol environment we observed might be shaped by the CIP. In summary, there were four observation sites: three CIZs and one non-CIZ. Observations of licensed premises were carried out in all four sites.

In terms of selecting licensed premises, we initially purposively sampled for diversity by selecting contrasting licenced establishment from each of the four sites, both recently licensed and established. Initially this consisted of sampling a public house, a café and a restaurant. As the fieldwork observations progressed, we took an emergent approach to identifying further premises of interest by picking out sites that were talked about by customers and staff during the course of the observations and by selecting those that seemed to be particularly busy or prominent features of the local alcohol environment. We visited a total of 39 licensed premises across these four sites. Permission to carry out the observational study was sought from the Local Authority and not from individual licensees. Full ethical approval for the study was granted by the LSHTM Observational and Interventions Research Ethics Committee (Ref 9968).

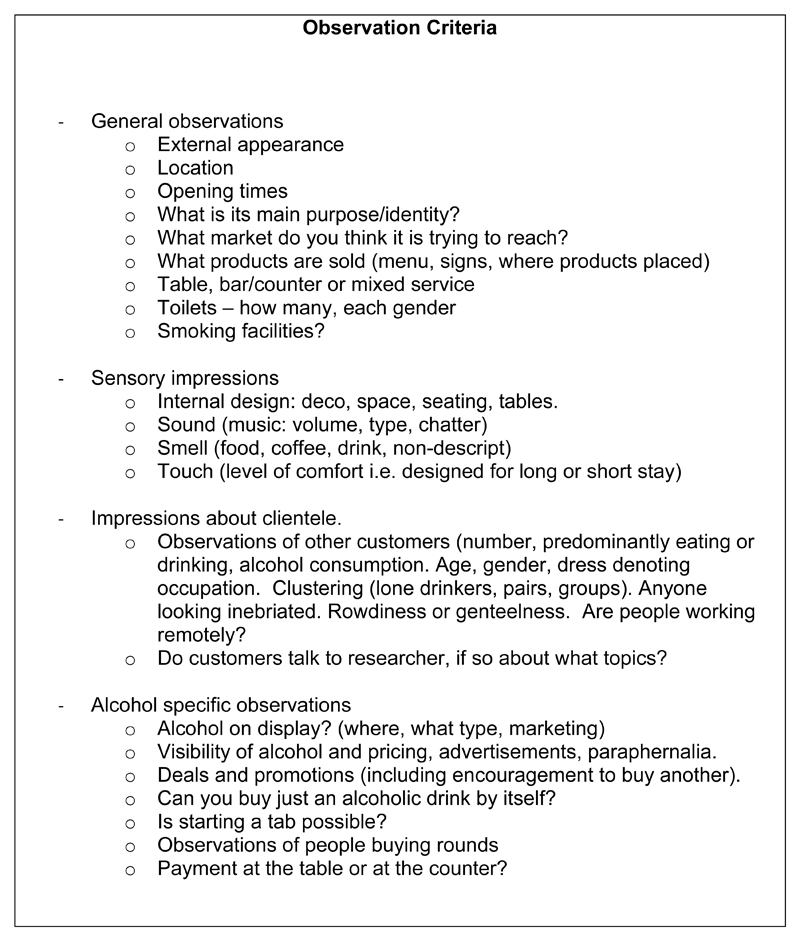

Observations were carried out during the day, between noon and 6pm. Each observation lasted around an hour, although some were longer. The aim was to form an overall impression of the establishment in terms of its clientele, atmosphere, design, and place in the wider alcohol environment. A semi-structured observation guide was used (see figure 1), which allowed for open-ended observations and impressions. The observation guide was developed by the four authors over a series of meetings and pilot observations. The observations were carried out by two of the authors (SM and CT), who divided the observation sites between them by each covering two of the four zones. Additionally, in order to check our interpretations and develop a shared understanding of how the fieldwork should be approached, two joint observations were carried out and a further two establishments were visited and observed separately by both SM and CT.

Figure 1.

Observation guide

As a primarily observational study, the focus of data collection and theorisation were the observations, experiences and interpretations of the researchers and the development of an understanding of the embodied experiences of drinking spaces (Jayne et al., 2010). However informal conversations with staff and customers, which occurred more frequently than we expected, were recorded in the fieldnotes. We found these impromptu and fleeting exchanges very valuable and often found ourselves referring to them during analytical discussions.

From the peripheral perspective gained form such encounters, informative insights can me made about the practices and trends under study, even if the researcher does not become a competent member of the culture or context under study (Laurier, 2016). However, unanticipated encounters in the course of qualitative fieldwork blur the distinction between researcher and participant (Brown & Durrheim, 2009; McCoy, 2012) and in doing so can generate scenarios outside the established procedural narrative of traditional qualitative interviews (Pinsky, 2015). SM and CT did not audio record or transcribe these interactions and encounters as we would in a traditional interview. Instead, fieldnotes were written-up after the observations to include any key utterances or observations made by customers or staff.

Data analysis

The observations were written up into detailed fieldnotes which were then uploaded to NVIvo9 and subject to a thematic analysis (Thorne, 2000). Emergent themes were circulated for comment and discussed at team meetings in order to refine interpretations and analytical strategies. Subsequent iterations and analysis of latent themes (Braun & Clarke, 2006) generated a localised typology of alcohol premises and a set of characterisations of the local alcohol environment which are reported in the results section.

The positionality of London-based academics (re)exploring localities

We took a ‘legitimate peripheral participation’ (Lave & Wenger, 1991) approach to the observations. The rationale behind this approach is that when observations are used in familiar settings and activities, the researcher has to work harder to notice things that are usually overlooked because it is hard to observe them from a natural attitude (Laurier, 2016). Both fieldworkers, SM and CT, live in London and work very nearby (walking distance, in some cases) to the sites being observed. Effectively, the researchers were spending time observing in establishments that they might easily have (and in some cases had) frequented as customers in their everyday lives. Observing social activity predicates participating, even in the most minimal or peripheral of ways (Laurier, 2016). In this case, SM and CT were participating as customers. Sometimes this was a very comfortable and easy experience, for example in the coffee-led establishments where we could type away happily on our laptops. At other times it was much less comfortable, for example in the more traditional pubs that we go on to describe in the next section of the paper. This reflected CT and SM’s positionalities as academic women and the embodied ease or discomfort of our habitus when entering a range of classed and gendered spaces.

Writing from middle-classed perspective of an academic, it is difficult to be objective about the arrival of hipster consumption establishments on previously ‘struggling’ and problematic high streets (Hubbard, 2016). Many of the places visited were experienced as welcoming and sometimes a ‘bit of a treat’ in the cases of the more upmarket and especially hipster-type establishments. The self-consciously ‘quality’ and ‘authentic’ products, like coffees and pastries, were a pleasure to consume. Our positionality and stake in relation to academic narratives of London, gentrification, and hipsters produces a situated account. Being explicitly reflexive about these ambivalences and anxieties is necessary in order to situate our ‘partial’ interpretation within the context of privilege, locality and personal-stake in which it was generated (Rose, 1997). It is easy for the authors to identify with aspects of the transient, aspirational, precarious, and creative ambitions of the hipster movement (Hubbard, 2016; Scott, 2017). The changes and trends we observe and comment upon here have direct material bearing on our lives and, therefore, our account is partially produced by our emotional entanglements with the fieldwork site (Laliberté & Schurr, 2015).

Results

The local daytime alcohol environment of Islington can be characterised in terms of two main trends: a decline in what were locally referred to as ‘traditional’ or ‘proper pubs’ and a proliferation of hybrid establishments, which accommodated a range of uses and social interactions. These trends are described below.

The decline of ‘traditional’ pubs

The areas in which observations took place contained a variety of drinking places, including restaurants, entertainment venues, pubs, bars and hybrid venues. The drinking spaces that had been newly licensed or recently refurbished were markedly different to older pubs in many ways, from their interiors, to the products they sold, to their clientele and ambience. Despite the older community pubs often being referred to as ‘proper’ or ‘traditional’ pubs, by local customers, there was a particular sense of decline and marginalisation around these sites. Three of the older pubs that we originally proposed to visit - for example - were closed down when we arrived, and in one case partly demolished.

The ‘traditional’ pubs observed were heavily male-dominated during the day. We found that these drinking spaces, as compared to others in the area, were not particularly welcoming to unfamiliar customers and appeared to be the domain of contained sets of ‘regular’ customers who were well known to each other and the bar staff. In this sense, they functioned as micro-communities of local people. These micro-communities were overwhelmingly male and working class, with little provision for those who did not share these characteristics. This can be seen in an extract from fieldnotes on an observation in a ‘traditional’ pub.

Nice atmosphere, clean (if a bit run down) and peaceful. Cheap to mid-range prices. Old Victorian look about the place. Lots of tables and chairs and many people look like they have been there for hours (newspapers, empty glasses, betting slips). No music and no jukebox. They do not serve food here or teas and coffees. The flooring is worn. All of the customers are white males and at least middle-aged. I am the only woman in here apart from the bar staff. This really has the feel of a ‘local’ pub. The clientele is definitely on the older side. Aside from a few customers everyone looks to be at least 50 and overwhelmingly of retirement age and over. Comfortably furnished with lots of seating. About half of the customers are standing up drinking by or near the bar. The others are mostly sitting down reading newspapers (mostly the Racing Post) and watching horseracing on large screen televisions. There is a betting shop across the road and there are betting slips on almost all the table tops. Vertical drinking and watching sports appear to be the only activities on offer. I feel out of place. Although the customers are not unfriendly - they nod and say hello and smile. The bar staff was quite short with me and returned her attention immediately to her ‘regular’ customers. Nearly everyone in here is drinking pints of lager / stout / ale. I cannot see anyone with what is obviously a soft drink. Seems like a space for steady all-day drinking. There are no pool tables, there is not enough space. There are no craft beers nor anything else that might be viewed as appealing to aspirational / gentrified tastes.

These pubs catered to specific practices and performativities, as described above, which are reflected in the homogenous clientele. Traditional pubs were typically not child-friendly (or explicitly banned children), offered little or no food, focused on screening various sporting events, and stocked a limited range of beers and spirits in popular brands. A number of these pubs were in the process of being rebranded, refurbished and/or taken-over by new owners. A fact much lamented by the clientele and staff of neighbouring ‘traditional’ pubs. As one customer observed, a nearby pub was ‘being run by new people now’ and becoming ‘one of those pubs’; becoming what were described locally as ‘trendy’ or ‘high-end’ pubs that were steadily replacing the ‘traditional’ ones. Another customer remarked at length on the significant changes made to a local pub he used to frequent, which included a redesign of both its space and its products, which in turn catered to a different kind of consumer and inferred a different way of drinking.

There was a clear social class divide evident between the ‘traditional’ drinking spaces and the new more up-market ones that deliberately cater to those with more affluent tastes. Not only were these spaces different in terms of classed norms and clientele, they also differed temporally. This difference was very marked, as can be seen from a fieldnotes extract below from a visit to a traditional pub.

This street has a definite temporal element to the alcohol environment. I have just tried to visit (two other pubs in this street – names removed) – they are closed and not open until about 4pm. This pub [name removed] appears to be the only traditional pub open round here at lunchtime. It is very quiet and dark inside. When I arrived there was only one other customer. The interior is big, cavernous even - high ceilings, no partitions – looks like it would have had live music years ago. There is lots of space and it looks very sparse. There are a number of big TV screens up on the walls that are (advertised) as being used to screen sporting events, mainly football. They do food at the weekend when the football is on: pizza and burger meal deals.

While traditional pubs were open all day and every day from 11am, weekday opening times of 4pm were not uncommon for the newer pubs. Those that focused on entertainment situated themselves exclusively in the NTE, as reflected in later opening times. Successful establishments that did accommodate daytime drinking appeared to be doing so in a decidedly different way from the traditional pubs they replaced.

The rise of hybrid establishments and the sidelining of alcohol

Thriving daytime drinking places in the study areas were typically some form of hybrid establishment – places in which alcohol featured as one of several attractions on offer. This is in direct contrast to the alcohol-centred daytime drinking spaces of traditional pubs. Unlike traditional pubs, successful daytime drinking spaces were generally and overtly child-friendly and not male dominated. Facilities for young children, including food, seating and entertainment were usually provided. One establishment had a selection of highchairs on prominent display near the counter (see figure 2). Hybrid establishments were either newer pubs that diversified their services or cafés and eateries that served alcohol. The newer ‘high end’ pubs opening during the day placed a heavy emphasis on food, had niche or specialised menus, and typically advertised as having ‘a kitchen’ – in order to emphasise that food was prepared on the premises. Their menus usually included a coffee range which allowed them to function as cafés, and also featured speciality or extensive wine selections, ranges of relatively expensive connoisseur or specialist drinks and ‘locally sourced’ produce. In short, they offered products and services, including alcohol, which marked them out as middle-classed spaces of consumption. One particularly successful ‘high end’ pub in the area incorporates a café, casual dining, and functions and a lounge / sports bar. One of their barman stated that ‘we cater for everything here, from football to the posh stuff’.

Figure 2.

Child-friendly drinking spaces: stylised high-chairs provided in a hybrid café

‘Alcohol-added’ cafés were successful establishments that, seeking to increase business, expanded their services and products, including the introduction of alcoholic beverages. As the manager of one local café that had recently successfully applied for an alcohol licence explained: ‘people stay longer when they are drinking’. This typically took the form of a very limited drinks range consisting of imported bottled beers and wines to accompany meals or as part of a theme night or cocktail promotion. In this way, establishments marketed themselves as offering ‘a little of everything’, as one manager put it. They were keen to advertise the broad range of services they provided, as could be seen in their counter displays and signs (see figure 3). Once again, the alcohol offered in these places was marketed as ‘authentic’ or niche in some way, which reinforced the boutique and middle-classed atmosphere. The extract below, from fieldnotes of a lunchtime observation at a busy independent café and deli, describes the atmosphere and experience of these establishments.

Figure 3.

A 'suite' of services: marketing from a hybrid café

It is not obviously a drinking establishment from the outside. There are homemade cakes in the window and it markets itself as a ‘rustic Italian café for breakfast, lunch and dinner’. There is easy-listening jazz type music playing. It opens at 8am and closes at 7pm. There are menus on the tables and there is table service - the waiting staff are very attentive. They also sell ‘authentic’ cooking ingredients like dried pasta, balsamic vinegar, panettone, and even some cookbooks and bakeware – there is a small display of these goods on a welsh dresser. Very relaxed atmosphere. They are very busy at lunchtime and it looks like there are a series of work / professional meetings going on as there are laptops out and note taking going on. Only one of these tables is drinking alcohol though (bottled beer). Clientele look reasonably affluent and some bohemian even. One couple appear to be having a detailed chat about almond milk. Alcohol is not listed on the sit down menu – you have to ask for it separately. If someone wants a drink then the waiter takes them over to the fridge and asks them to pick something. Alcohol is not an immediately obvious part of this environment.

In a further example, one café-deli specialised in Portuguese wines. Very few other alcoholic beverages were stocked and these wines were given a small but prominent display space on the counter. They served as a niche specialism and attraction, as an opportunity for customers to try something they may not be able to obtain elsewhere. The narrative around these wines, including the region in which they were produced and the particular foods that they should accompany, added a sense of authenticity to the products sold. Newly licensed places tended to present alcohol as a ‘craft’ product. One establishment offered ‘tasters’ of different types of beer and menus often gave extensive details on the location of the breweries and brewing processes. Such a focus on the ‘rich story’ of beer directly paralleled the ways in which coffee was marketed in these spaces. Both products were localised and personified, with emphasis on specifics such as the location in which the products were produced or grown and their histories. In this sense, alcohol was presented as one of a suite of consumer products that were designed to appeal to a range of ages and tastes but which appeared to target middle class consumers. Typically, the customers in these establishments could be observed engaging in a variety of activities and social interactions. Some were dining with friends, while others were working remotely at a laptop or having meetings. Drinking practices were varied in these spaces with some customers drinking coffees and others consuming alcoholic beverages. Interestingly, we did not observe any lone customers consuming alcohol in the course of the observations. This is in direct contrast to the way in which ‘traditional’ pubs inherently presented alcohol consumption as the main, and even sole, purpose of those spaces, with solo-drinking an entirely acceptable activity.

Discussion

This paper presents a situated case study of the daytime alcohol environment of Islington, a London Borough that is characterised both by ongoing gentrification and a challenging NTE. The local daytime alcohol environment is becoming increasingly varied, with a rise in alcohol licences for hybrid establishments in which alcohol is one of a variety of products and services on offer. Whilst an observational study of licensed premises cannot establish causality or generalisability, the findings are useful in that they illustrate the fluidity of local alcohol environments in the context of broader social trends and highlight some potential problems for public health.

Beyond gentrification and the temporal dispersal of drinking

The decline of traditional pubs is an established national trend (Haan, et al., 2010) and our findings demonstrate that Islington is no exception to this. Hybrid establishments, increasing in areas like Islington, both reflect and produce the tastes of an affluent population – known as ‘hipsters’ in popular culture, and increasingly the focus of attention in sociological studies of gentrification. With regards to alcohol, hybrid establishments appear to help facilitate a temporal shift in drinking practices. Traditionally, drinking alcohol has symbolically shaped the temporal organisation of daily and weekly life into divisions of work and ‘play’ (Bernstock, 2013). The development of night time economies, of which alcohol is a key part, is based upon the association of leisure with night-time spaces. The counterpoint to this is a reinforcement of cultural disapproval towards daytime drinking within the context of (working) classed temporal demarcations of literal and symbolic ‘clocking on’ and ‘clocking off’. Drinking while ‘on’ is not socially acceptable in the folk conception of ‘competent drinkers’; those who abide by the appropriate settings in time and space (Gusfield, 2013).

The same has not traditionally held true for middle class or so-called ‘creative class’ and Hipster practices associated with flexibility and agency, which serve to blur the divisions between work and play (Jones & Warren, 2016). The temporal and classed divisions of drinking are bridged by hybrid establishments. Hobbs and colleagues describe these venues as ‘chameleon bars’; in that they operate as one thing during the daytime and quite another at night (Hobbs et al., 2003). This is certainly the case in Islington, where temporally demarcated drinking practices are bound-up with the transient and flexible practices and part of Hipster performativities. Hybrid establishments offer a ‘symbiosis of contrasts’: symbols of relaxation (alcohol) and work (coffee) (Gusfield, 2013).

For the authors, we found this break-down of temporal demarcations and implicit flexibility and agency so comfortable and familiar that is was, initially, difficult to disentangle ourselves from. The middle and creative-classed working and temporal patterns (Jones & Warren, 2016) that the hybrid establishments embodied are an established characteristic of academic life and research. Neo-liberal governance has impacted upon academic identities in diverse ways: emphasising autonomy, creativity and precarity (Harris, 2005). As a consequence, the liminal spaces that facilitated these elements were initially experienced as an extension of our familiar working and leisure spaces. As places that we might easily work-from-home in or meet with colleagues and collaborators. In light of this, we must acknowledge our positionality when critically discussing the potential impact of these places on the local community. The male dominated traditional working-classed spaces did not represent settings and interactions in which we could easily participate. As a result, those occupying ‘traditional’ spaces were implicitly framed as ‘other’ to us and, consequently, may have been, extended less sympathy in our framing than the diversified liminal spaces of hybrid establishments.

Diversification is a contemporary alcohol industry trend, and one that has arisen partly in response to an overall decline in alcohol consumption (Nicholls, 2011). In the context of NTEs, this has taken the form of corporate café-bar-club venues that offer a convenient array of entertainment for the whole evening in one space. This model has come to dominate the public spaces of the NTE (Jayne et al., 2010; Measham & Brain, 2005). By contrast, relatively little is written about how diversification manifests in the daytime alcohol environment. The findings of this study address this gap by examining practices within diversified daytime drinking spaces.

The intersection of alcohol policies and regeneration processes

As previously stated, the setting for this study, Islington, is characterised by both a highly regulated NTE (via Cumulative Impact Policies and other interventions) and the ongoing processes of gentrification, and even ‘super-gentrification’ (Smith, 2006). It should be noted that these two characteristics are not entirely separate or discrete. Alcohol licensing can shape the spaces in which alcohol is sold and drunk (Caritas, 2012). Further, decisions about what constitutes a problem area or type of drinking establishment are partly shaped by broader socio-cultural perceptions, trends and contexts (Grace et al., 2016), like gentrification. While the local CIP intervention may not be directly linked to the ongoing closures of traditional pubs, it does influence the types of drinking spaces that replace them. Gentrification involves the displacement of working class populations and spaces (including traditional pubs) and Local Authority policies can actively encourage and facilitate this displacement (Hubbard, 2016).

It has been suggested a CIP being in place has deterred some potential applicants (Morris, 2015). In this sense, CIPs are implicated in gentrification processes because they encourage middle class transformations of place through facilitating adaptions to the supposed tastes of potential gentrifiers (Rosseau, 2009). They can be understood as policy instruments that promote a cosmopolitan, hipster-led model of retail gentrification as a way of regenerating and improving local areas (Hubbard, 2016). CIP’s often target ‘problematic’ vertical and binge-drinking practices (London Borough of Islington, 2012) commonly associated with working-classed spaces of traditional pubs in favour of venues that serve food and cater to a wider range of non-drinking activities and customers (Grace et al., 2014). This aim reflects policy concerns that such premises are frequently associated with disorder and harms but it also dovetails with the business-marketing model of culturally infused micro-enterprises, such as independent delis, cafes and eateries, that are the means of micro-cultural production of ‘hipster capitalism’ (Scott, 2017).

Implications for health

The perception of changing alcohol consumption behaviours that the rise of hybrid, or ‘chameleon’ (Hobbs et al., 2003) establishments suggest are regarded as broadly positive in terms of public health, crime and safety. Less regular and vertical drinking, like that associated with the NTE and traditional pubs, and a proliferation of mixed, family friendly licensed premises are all factors that have been proposed as contributing to a reduction in excessive consumption and alcohol related harms (Gibson et al., 2011; Krieger & Higgins, 2002). As actors researching and writing within the positionality of middle-classed academic conventions, we are bound-up and implicated in the proliferation and reproduction of such assumptions. It is important to acknowledge that this assumption in particular (that family-friendly gentrified spaces contain less potential for harmful drinking practices), is unproven. In fact, hybrid establishments could be argued to be helping introduce and legitimise alcohol into contexts, times and behaviours where it would not previously have been present or acceptable. In these spaces, alcohol is implicitly framed as a ‘treat’. This has the potential to impact upon local drinking patterns because the relationship between drinking practices and drinking spaces is reciprocal. While certain venues may attract certain types of customers, it is also true that individuals may alter and adapt their drinking practices depending on the space and setting in which they are participating (Ross-Houle et al., 2015).

While daytime drinking in traditional vertical drinking establishments may be subject to social disapproval, indulging in a speciality beer or wine in a café would likely attract less condemnation. Meaning that alcohol-consumption in more aspirational and hipster-themed spaces may not be subject to the same degree of critical concern as it is in traditional drinking spaces. On reflection, this is very much congruent with our initial encounters with such spaces. The boutique-framing of alcohol piqued our interest with a sense of novelty and curiosity. We did not initially perceive them as primarily part of the alcohol environment nor frequenting them as a social act of ‘going out for a drink’. This is perhaps unsurprising given that it has been suggested that public health messaging about alcohol is not reaching higher income groups who are, typically, healthier than other sections of society, but who are still high alcohol consumers (Iparraguirre, 2015). The press and policy focus of issues on alcohol related harm is overwhelmingly on young people and vulnerable groups (Bernstock, 2013), which risks ignoring higher income groups. This serves to overshadow the wider issues of problem consumption across all ages and income groups (Shaw et al., 1999).

Conclusions

This paper reports on the findings of a qualitative study aiming to explore the daytime alcohol environment of Islington. The intersection of an expanding hipster habitus (Hubbard, 2016) with Local Authority efforts to tackle practices of ‘determined drunkenness’ (Measham & Brain, 2005) are the backdrop to the proliferation of hybrid venues we observed and their implicit framing of alcohol as a possible ‘treat’ within a range of products on offer. While this has the obvious benefit of discouraging excessive drinking practices often associated with vertical drinking establishments, it may also, conversely, risk negative impacts in the longer term by feeding into current alcohol industry strategies of promoting ‘new moments’ and contexts in which consumers can drink (Pevalin, 2007). The next logical step in this research agenda is to move from participant observation to semi-structured interviews, in order to interrogate this assumption and explore the issues and trends identified in this study.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Public Health Research (SPHR).

Footnotes

Disclaimer

This research was funded by the NIHR. The authors have no competing interests to declare. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

References

- Ally A, Lovatt M, Meier PS, Brennan A, Holmes J. Developing a social practice-based typology of British drinking culture in 2009-2011: Implications for alcohol policy analysis. Addiction. 2016;111:1568–1579. doi: 10.1111/add.13397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews GJ, Sudwell MI, Sparkes AC. Towards a geography of fitness: an ethnographic case study of the gym in British bodybuilding culture. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;60:877–891. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell E. The official guide to day drinking like a pro and still making it out at night. Vinepair. 2016 (p. Online magazine article) [Google Scholar]

- Bernstock P. Olympic Housing: a critical review of London 2012’s Legacy. Farnham: Ashgate; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Brown L, Durrheim K. Different Kinds of Knowing: generating qualitative data through mobile interviewing. Qualitative Inquiry. 2009;15:911–930. [Google Scholar]

- Camino Lópeza MA, Fontanedab I, González Alcántarab OJ, Ritzelc DO. The special severity of occupational accidents in the afternoon: “The lunch effect”. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2011;43:1104–1116. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2010.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caritas. Council’s move highlights severity of problem in Newham. London: Caritas Anchor House; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming E. The Observer. London: 2015. Mar 8, Can hipsters save the world? 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Delany A. Bon Appétit; 2016. How to Survive 18 Hours of Drinking on St. Patrick’s Day Without Falling on Your Face. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim IO, Shapiro CM, Williams AJ, Fenwick PB. Alcohol and Sleep I : Effects on Normal Sleep. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2013;37:539–549. doi: 10.1111/acer.12006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan M, Brennan A, Buykx P, De Vocht F, Gavens L, Grace D, et al. Local policies to tackle a national problem: Comparative qualitative case studies of an English local authority alcohol availability intervention. Health & Place. 2016;41:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson E, Richards L. The 100 best bars and pubs in London: daytime drinking. Time Out (London); London: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald N, Angus C. Four Nations: how evidence-based are alcohol policies and programmes accross the UK. Alliance for Useful Evidence / Alcohol Health Alliance; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson M, Petticrew M, Bamba C, Sowden AJ, Wright KE, Whitehead M. Housing and health inequalities: A synthesis of systematic reviews of interventions aimed at different pathways linking housing and health. Health & Place. 2011;17:175–184. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace D, Egan M, Lock K. Examining local processes when applying a cumulative impact policy to address harms of alcohol outlet density. Health & Place. 2016;40:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace D, McGill E, Lock K, Egan M. How do Cumulative Impact Policies work? Use of institutional ethnography to assess local government alcohol policies in England. The Lancet. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Gusfield JR. Passage to play: rituals of drinking time in American society. In: Douglas M, editor. Constructive Drinking: perspectives on drink from anthropology. London: Routledge; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Haan N, Kaplan GA, Camacho T. Poverty and health: prospective evidence from the Alameda County study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1987;125:989–998. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield P. Bar Wars: Contesting the Night in Contemporary British Cities. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hadfield P, Lister S, Traynor P. “This town”s a different town today’: Policing and regulating the night-time economy. Criminology & Criminal Justice. 2010;9:465–485. doi: 10.1177/1748895809343409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris S. Rethinking academic identities in neo-liberal times. Teaching in Higher Education. 2005;10:421–433. [Google Scholar]

- Hayward K, Hobbs D. Beyond the binge in 'booze Britain': market-led liminalization and the spectacle of beinge drinking. The British Jounal of Sociology. 2007;58:437–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2007.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs D, Hadfield P, Lister S, Winslow S. Bouncers: Violence and Governance in the Night-time Economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Horne JA, Reyner LA, Barrett PR. Driving impairment due to sleepiness is exacerbated by low alcohol intake. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2003;60:689–692. doi: 10.1136/oem.60.9.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard P. Hipsters on Our High Streets: Consuming the Gentrification Frontier. Sociological Research Online. 2016;21:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Alcohol Studies. Alcohol in the workplace: Factsheet. London: IAS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Iparraguirre J. Socioeconomic determinants of risk of harmful alcohol drinking among people aged 50 or over in England. BMJ Open. 2015;5 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayne M, Valentine G, Holloway SL. Emotional, embodied and affective geographies of alcohol, drinking and drunkeness. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 2010;35:540–554. [Google Scholar]

- Jones P, Warren S. Time, rhythm and the creative economy. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. 2016;41:286–296. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger J, Higgins DL. Time Again for Public Health Action. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:758–768. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.5.758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laliberté N, Schurr C. The stickiness of emotions in the field: Introduction. Gender, Place and Culture. 2015;23:72–78. [Google Scholar]

- Laurier E. Participant Observation. In: Clifford N, Cope M, editors. Key Methods in Geography. London: Sage; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lave J, Wenger E. Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- London Borough of Islington. Licensing Policy 2013-2017: Licensing Act 2003. 2012.

- Lukas SA. Theme Park. London: Reaktion Books; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Martineau F, Tyner E, Lorenc T, Petticrew M, Lock K. Population-level interventions to reduce alcohol-related harm: an overview of systematic reviews. Preventative Medicine. 2013;57:278–296. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy K. Toward a Methodology of Encounters: Opening to Complexity in Qualitative Research. Qualitative Inquiry. 2012;18:762–772. [Google Scholar]

- Measham F, Brain K. ‘Binge’ drinking, British alcohol policy and the new culture of intoxication. Crime, Media, Culture: An International Journal. 2005;1:262–283. [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. Licensing figures 2014: premises down slightly, but reviews still falling and questions over 're-balancing' measures. Alcohol Policy; UK: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls J. The politics of alcohol: A history of the drink question in England. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Penny J, Shaheen F, Lyall S. In: Distant Neighbours: Poverty and Inequality in Islington. N.E. Foundation, editor. London: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Pevalin DJ. Socio-economic inequalities in health and service utilization in the London Borough of Newham. Public Health. 2007;121:596–602. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinsky D. The sustained snapshot: Incidental ethnographic encounters in qualitative interview studies. Qualitative Research. 2015;15:281–295. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts M, Eldridge A. Planning the Night-time City. London: Routledge; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rose G. Situating knowledges: positionality, reflexivities and other tactics. Progress in Human Geography. 1997;21:305–320. [Google Scholar]

- Ross-Houle K, Atkinson A, Sumnall H. Chapter 3: The symbolic value of alcohol. In: Thurnell-Read T, editor. Drinking Dilemmas: Space, Culture and Identity. London: Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rosseau M. Re-imaging the City Centre for the Middle Classes: Regeneration, Gentrification and Symbolic Policies in ‘Loser Cities’. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 2009;33:770–788. [Google Scholar]

- Schiermer B. Late-modern hipsters: New tendencies in popular culture. Acta Sociologica. 2014;57:167–181. [Google Scholar]

- Scott M. 'Hipster Capitalism' in the Age of Austerity? Polanyi Meets Bourdieu's New Petite Bourgeoisie. Cultural Sociology. 2017;11:60–76. [Google Scholar]

- Shaheen F. Super-gentrification, inequality and Islington. Fabian Essays: Fabian Society. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- Shaw M, Dorling D, Brimblecombe N. Life chances in Britain by housing wealth and for the homeless and vulnerably housed. Environment and Planning A. 1999;31:2239–2248. [Google Scholar]

- Smith L. The Times. London: Times Newspapers Limited; 2006. Septmeber. There's plain gentrification … and then you have Islington. [Google Scholar]

- Smithers R. Number of pubs in UK falls to lowest level for a decade. The Guardian; London: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thorne S. Data analysis in qualitative research. Evidence Based Nursing. 2000;3:68–70. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health 2014. World HEalth Organisation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K, Elliot S, Law M, Eyles J, Jerrett M, Keller-Olaman S. Linking perceptions of neighbourhood to health in Hamilton, Canada. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2004;58:192–198. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.014308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]