Abstract

Time and memory are inextricably linked, but it is far from clear how event durations and temporal sequences are encoded in memory. In this review, we focus on resource allocation models of working memory which suggest that memory resources can be flexibly distributed amongst several items such that the precision of working memory decreases with the number of items to be encoded. This type of model is consistent with human performance in working memory tasks based on visual, auditory as well as temporal stimulus patterns. At the neural-network level, we focus on excitatory-inhibitory oscillatary processes that are able to encode both interval timing and working memory in a coupled excitatory-inhibitory network. This modification of the striatal beat-frequency model of interval timing shows how memories for multiple time intervals are represented by neural oscillations and can also be used to explain the mechanisms of resource allocation in working memory.

Introduction

Time is an integral aspect of action, perception, and cognition [1–4]. However, the neural mechanisms that encode and store intervals of time in memory for the perception of sensory stimulus patterns and production of complex sensorimotor output are not fully understood [5–7]. Here, we describe recent behavioral, computational, neuroimaging, and physiological findings that shed new light on the neurobiological bases of temporal memory. Specifically, we focus on resource allocation models of working memory which suggest that memory resources can be flexibly distributed amongst several items such that the precision of working memory decreases with the number of items to be encoded. These models are consistent with human performance in working memory tasks based on visual, auditory as well as temporal stimulus patterns [8]. At the neural network level, we focus on an excitatory-inhibitory oscillation (EIO) model that encodes both interval timing and working memory in a coupled excitatory-inhibitory network [9]. This model shows how the memories for multiple time intervals are represented by neural oscillations and also explains the mechanisms of resource allocation in working memory. We review the results from these experimental studies and generalize how these findings might be integrated in order to obtain a neurobiologically-plausible code for incorporating temporal information in working memory [10].

Models of working memory

Working memory is traditionally defined as a cognitive capacity for transiently storing, processing, and manipulating information [11]. While the notion of working memory extends naturally for sensory information like visual or auditory signals, it is not clear how it applies to temporal information, even though conceptually, time and memory are closely interlinked. Classical models of working memory propose a fixed number of discrete memory “slots” where only a limited number of items can be represented in memory with a fixed resolution [12, 13]. However, these models based on change-detection paradigms have been recently challenged by new models that suggest working memory is a limited resource that is dynamically shared between all sensory items to be stored in memory [14–16]. Furthermore, this memory resource is flexible and can be modulated by cognitive factors like selective attention and task demands where each item is stored with either a fixed [14, 17] or variable resolution [15]. These models suggest that memory recall is a continuous rather than a binary measure and characterized in terms of “precision” (computed as the inverse of the standard deviation of error responses) that might be equal or variable across all items [16]. Several experimental studies have demonstrated these novel hypotheses to be consistent with visual [14–20] and auditory working memory performance [21–23]. In light of these recent findings, the current consensus is that working memory might be best viewed as a limited resource that is flexibly allocated across all items to be stored in memory [8, 24–26].

Resource models of temporal memory

Recent work has examined the resource model of working memory in the context of interval timing behavior [27]. Participants were presented a sequence of clicks, where the temporal jitter between clicks was parametrically varied from 5 - 50% across four distinct levels of jitter. At the offset of the sequence, a visual probe displayed the interval number whose duration participants were required to reproduce. The start of the reproduction interval was cued by another click and participants had to respond at a point in time that corresponded to their memory of the probed interval duration. The difference between the actual and the reproduced duration was quantified to obtain the error distribution and the precision of temporal memory recall. An outline of this timing task is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Temporal memory task [adapted from 38].

Listeners are presented a sequence of time intervals separated by clicks. A visual message is used to display the probe interval to be remembered and reproduced at the offset of the last click in the sequence. After a variable delay period, listeners hear another click which signifies the start of the interval to be reproduced by pressing a button when they think that duration equal to the probed interval has elapsed. Feedback measured as the difference between the duration of the reproduced and the probed interval is presented after each trial.

In two separate experiments, the time intervals between the clicks were either in the sub-second (500-600 ms) or supra-second range (1.0-1.2 s). In both experiments, working memory for the probed interval declined in irregular sequences with higher levels of jitter. This result demonstrated for the first time that temporal memory depends on the temporal structure of the sequences containing those intervals, a finding that cannot be concluded from binary judgment of the duration of single time intervals. The effect was stronger for sub- compared to supra-second intervals, and primacy and recency effects of memory recall were also observed for the sub-second, but not the supra-second sequences of intervals. Furthermore, the precision values for the sub- versus the supra-second intervals were approximately in the ratio 1:2, demonstrating a trend consistent with the scalar property of interval timing [29–32].

Another experiment in the same study introduced a variable number of clicks in the sequences to simulate variable working memory load (1 - 4 items). The precision of temporal memory decayed nonlinearly with increasing number of intervals in the sequence, consistent with the predictions of the resource allocation models of working memory [8]. These results were recently replicated in another set of behavioral experiments [32].

Neural mechanisms of temporal memory

A key question that follows from these behavioral experiments concerns the underlying neuronal substrates of temporal memory. Dedicated models of interval timing suggest that time is encoded in distributed subcortical and cortical networks [6, 10, 33–35]. However, the neural substrates of temporal memory have received considerably less attention. Initial studies focused on memory-based comparison of the absolute duration of a target interval versus a single reference interval. Rao and colleagues [36] used event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and observed early activity in the basal ganglia associated with encoding time intervals and late activation in the cerebellum. Early cortical activation was observed in the right inferior parietal cortex and bilateral premotor cortex associated with attention and maintenance of intervals whilst late activation in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex emerged during the actual comparison of time intervals. In a similar rapid event-related fMRI study, Coull and colleagues [37] found the left putamen to be active during encoding the stimulus duration into working memory and the putamen response was also predictive of timing performance whilst retrieval and comparison of stimulus durations engaged the right superior temporal gyrus. These results, however, are limited as they only account for encoding single time intervals in working memory.

Teki and Griffiths [38] used fMRI to examine the substrates of temporal memory that vary according to the temporal structure and number of items in the sequences based on their previous behavioral task [27]. In two orthogonal conditions, the temporal jitter in sequences was parametrically varied (5 - 50% jitter) for a fixed number of intervals (4), and the number of intervals in the sequence was modulated (1 - 4 intervals) for a fixed jitter level (20-25%).

Blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) responses associated with the recall of the probed interval were observed in the cerebellum as a function of increasing jitter and the striatum (left putamen and caudate nucleus) as a function of decreasing jitter respectively. This result is consistent with previously reported dissociation of perceptual timing responses in the cerebellum and striatum according to the temporal context of the sequences: cerebellum is more active during perception of time intervals in an irregular context whilst the striatum is more active for regular, beat-based sequences [39]. These results suggest that mnemonic precision of temporal memory recall also shows the same contextual pattern of responses in these two core sub-cortical timing networks [6, 35, 40]. Furthermore, activity in bilateral inferior parietal cortex and the caudate nucleus increased as a function of increasing number of time intervals (or working memory load), in accord with previous findings [36, 37].

Neural models of temporal memory

Although neuroimaging studies can shed light on the underlying neuronal substrates, the precise mechanism by which time is encoded in working memory is not yet understood. Gu et al. [9] recently proposed a coupled excitatory-inhibitory oscillation mechanism in order to integrate the striatal beat frequency (SBF) model of interval timing [41–43] with oscillatory models of working memory [44]. This hybrid EIO model is based on the assumption that information for both interval timing and working memory is represented in the same network with oscillatory interactions between excitatory and inhibitory inputs. According to the EIO model, interval timing and working memory differ in terms of which dimension of the neural oscillations is utilized for the extraction of item, temporal order or duration information. Specifically, the model suggests that duration information can be extracted from theta oscillations entrained in the delta rhythm while item information in working memory can be extracted from gamma oscillations entrained in the theta rhythm respectively. Moreover, this proposal is supported by recent electrophysiological studies [45–47].

The EIO model primarily accounts for duration information that is not defined by specific movements or a continuous predictable pattern of stimulus presentations, but a cognitively controlled measurement of supra-second durations. However, other ranges of duration including sub-second are reported to involve beta and/or gamma rhythms, especially when specific movements or predictable patterns are involved [48–50]. In this case, the EIO model can be extended to explain the representation of sub-second, rhythmic duration using beta oscillations entrained in delta/slower rhythm. In addition, the EIO model readily explains the basic features of resource allocation (e.g., reduced precision with increasing number of intervals) when maintaining multiple intervals in working memory.

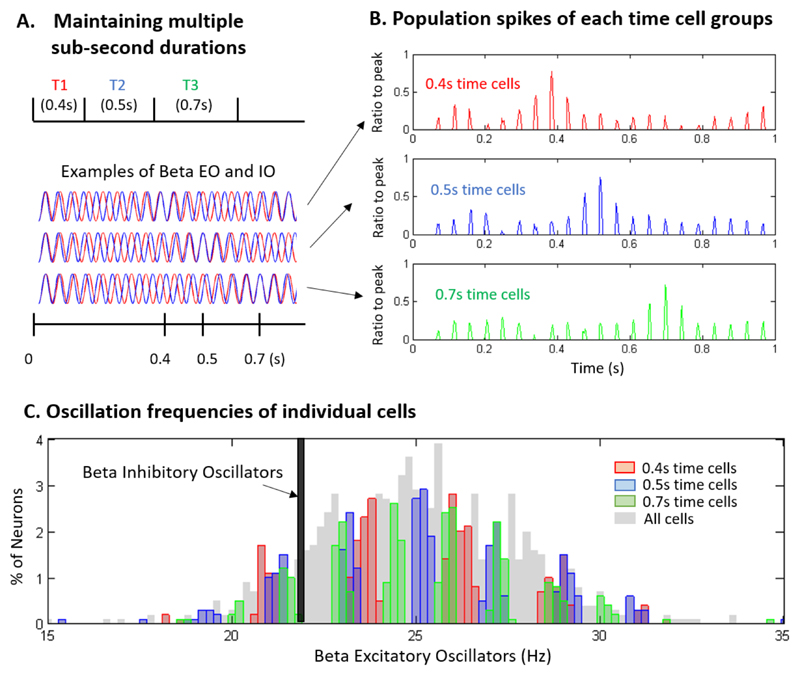

The EIO model assumes that a triggering event will perturb the neural network such that the frequency of excitatory oscillation (EO) inputs varies across neurons while inhibitory oscillation (IO) inputs are relatively synchronized within a local neuronal network (Figure 2A). With sound onset to be timed, EO and IO will oscillate in beta rhythms and the summation of EO and IO inputs in each neuron will produce an interference pattern of beta entrained in delta or a slower rhythm. Variation in EO frequencies produces the variation of the envelope delta frequencies, thus the peak firing rate of each neuron varies in time. The coincident pattern of a group of neurons encodes duration information, for example, the group of cells that have a peak activity at 0.4 s form a triggering event that can represent the 0.4-s duration (Figure 2B). Different groups of cells are used to represent different durations, however, there will be overlapping cells among different time cell groups (Figure 2C). These overlapping time cells reduce the precision of temporal memory when multiple durations have to be maintained simultaneously, consistent with the resource allocation models of working memory.

Figure 2. Excitatory-inhibitory oscillation model of interval timing and working memory.

(A) Multiple sub-second durations can be maintained by multiple interference patterns produced by excitatory oscillators (EO, blue) and inhibitory oscillators (IO, red). A triggering event (e.g., click sound) can drive various frequencies of EOs in beta frequency range across a cell population (desynchronized) with relatively synchronized IOs. The EO and IO inputs produce beta rhythms entrained in delta or a slower frequency, and this pattern can be maintained during sub-second durations.

(B) The coincident firing pattern of a relevant neuronal group encodes the duration information for a time interval. For example, the 0.4-s time cells are a neuronal group showing a firing peak around 0.4 s and their population firing produces beta rhythm whose power peaks at 0.4 s. Similarly, other groups of time cells represent different durations.

(C) A distribution of beta EO frequencies for simulated neurons. The EO frequency of individual neurons determines the duration that they can represent. Increasing the number of durations to encode will produce overlaps between the cell groups, and this overlap will undermine the precision of temporal memory. This prediction is consistent with the results of Teki et al. [38] showing that time is embedded in the memory code.

Multiple brain areas such as cortico-striatal circuits, hippocampus, and cerebellum have been suggested to mediate interval timing [51–54]. The characteristics of time intervals such as the duration range or regularity of intervals have been associated with the involvement of specific brain areas. The network properties of those brain areas are different from each other, therefore different patterns of neural oscillations will be optimally represented by each brain area. The oscillatory property of a neural network is likely to be the determining factor for which brain area is the best place to represent certain characteristics of an interval of time.

Integration of hippocampal time cells

The hippocampus is largely involved in relational memory and encodes information based upon almost any salient features of a task, evidenced by the vast changes in its information processing as a function of context [55]. The capacity to support relational memory makes the hippocampus an ideal brain structure for temporal integration [56, 57], as temporal connections are implicitly made between events. These implicit connections can be made in many contextual frames so it is essential to identify the most parsimonious reference point (e.g., temporal or spatial). The temporal reference frame in hippocampal ‘time cells’ was first identified in the CA1 pyramidal layer of rats by MacDonald and colleagues [58]. Their findings provided support for the proposal that hippocampal ‘time cells’ signal both temporal and spatial information on a continuum. This was based on the observation that when the duration of a delay period was suddenly changed, largely new sequential patterns of activity emerged. Thus, just as ‘place cells’ remap to represent different spatial contexts, these ‘time cells’ adjusted (what the authors referred to as “retimed”) in order to represent a different temporal context. Consequently, these hippocampal neurons are referred to as ‘time cells’ because they share many of the same general properties of ‘place cells’, but are instead correlated with the temporal domain.

The temporal coding properties of hippocampal CA1 cells are thought to arise from either changing cortical states, strengthening of chain-like connectivity causing sequential activation, or a combination of the two [59]. Computational modeling may provide an additional tool to understand how CA1 cells acquire their ability to time [60–62]. For example, one model has shown that the firing rate and phase of ‘time cells’ relative to theta oscillations can approximate physical time on a single trial basis [63]. Recent evidence also points to a role of CA2 in timing behavior given that activity within this region is more time dependent compared to other CA subfields. One hypothesis is that CA2 provides temporal information to CA1 whereas CA3 sends spatial information [64]. Entorhinal ‘grid cells’ are also probably a source of temporal information for these ‘time cells’ [65]. It is important to note that some of the timing properties of CA1 may arise from many complex anatomical connections. For example, CA1 pyramidal neurons are excellent at integrating information across spatiotemporal gradients. With approximately 30,000 synapses to manage, the pyramidal neurons use hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channels to synchronize synaptic inputs across time and distance in relation to the soma so that each input carries equal weight [66]. In this respect, there is an interesting similarity between the ‘oscillatory interference’ models of grid cell firing and the currently proposed EIO model of timing [67–68].

In contrast to the studies of hippocampal involvement in prospective timing [69], none of the behavioral tasks used to evaluate hippocampal ‘time cells’ require that specific durations be timed in order to earn reward. It is therefore likely that hippocampal ‘time cells’ are used to construct a temporal framework for memories using retrospective timing rather than being used to time specific durations [56]. This greatly reduces attentional demands as retrospective timing creates a sense of time for events that were not explicitly timed. This retrospective framework is consistent with the vast literature showing the hippocampus is crucial for sequence learning and retrieval. BOLD fMRI studies have been used to show that hippocampal activation patterns during retrieval carry information about when objects occur in learned sequences, even without being instructed to pay attention to the temporal structure of sequences [70].

Conclusions

As suggested above, information derived from and maintained by interval timing and working memory can be conveyed through different ranges of brain oscillations involving theta entrained in delta and gamma entrained in theta, respectively. The functional role of neural oscillations is unlikely to be limited to interval timing and working memory, but can also be applied to most of other psychological functions via different frequency ranges of oscillations conveying different dimensional information [71–77]. Gamma oscillations, for example, have been proposed to be responsible for the “binding” of features into a coherent cognitive unit [78–79] and the ultrafast oscillations, which are also known as ripples (150–250 Hz), represent replay of previously experienced firing patterns in a temporally compressed manner and has been shown to be vital for memory transfer and consolidation [80–82]. Moreover, increasing evidence supports the importance of infra-slow fluctuations (<0.1 Hz) in cognition as well as in brain signals [76]. The variance in cognitive performance fluctuates over tens to hundreds of seconds and has largely been considered “noise”; however, the variance of cognition/behavior has shown to increase with time scales, showing 1/f-type power distribution rather than just a random (white noise) distribution in the temporal sequence of errors [83–85]. This suggests that the temporal variance of cognition originates from a common mechanism that coordinates time and memory across a wide range of memory processes that are modulated by competitive cuing, temporal precision, and oscillator-based encoding of duration [86–93].

Acknowledgments

ST is supported by the Wellcome Trust (Sir Henry Wellcome Postdoctoral Fellowship: 106084/Z/14/Z).

WHM is supported, in part, by a research fellowship from the JEZHAM Foundation.

References

- 1.Allman MJ, Teki S, Griffiths TD, Meck WH. Properties of the internal clock: first- and second order principles of subjective time. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65:743–771. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthews WJ, Meck WH. Temporal cognition: connecting subjective time to perception, attention, and memory. Psychol Bull. 2016;142:865–907. doi: 10.1037/bul0000045. [• State-of-the-art review of the integration of time and time perception with cognition more broadly defined.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meck WH, Ivry RB. Time in perception and action. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2016;8:vi–x. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finnerty GT, Shadlen MN, Jazayeri M, Nobre AC, Buonomano DV. Time in cortical circuits. J Neurosci. 2015;35:13912–13916. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2654-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardy NF, Buonomano DV. Neurocomputational models of interval and pattern timing. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2016;8:250–257. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merchant H, Harrington DL, Meck WH. Neural basis of the perception and estimation of time. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2013;36:313–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062012-170349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teki S. A citation-based analysis and review of significant papers on timing and time perception. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:330. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma WJ, Husain M, Bays PM. Changing concepts of working memory. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:347–356. doi: 10.1038/nn.3655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gu B-M, van Rijn H, Meck WH. Oscillatory multiplexing of neural population codes for interval timing and working memory. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;48:160–185. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.10.008. [• An extensive review integrating the striatal beat-frequency model of interval timing with oscillatory models of working memory.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Rijn H, Gu B-M, Meck WH. Dedicated clock/timing-circuit theories of time perception and timed performance. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;829:75–99. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-1782-2_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baddeley A. Working memory: theories, models, and controversies. Annu Rev Psychol. 2012;63:1–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller GA. The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychol Rev. 1956;63:81–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cowan N. The magical number 4 in short-term memory: a reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behav Brain Sci. 2001;24:87–114. doi: 10.1017/s0140525x01003922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bays PM, Husain M. Dynamic shifts of limited working memory resources in human vision. Science. 2008;321:851–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1158023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van den Berg R, Shin H, Chou W-C, George R, Ma WJ. Variability in encoding precision accounts for visual short-term memory limitations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:8780–8785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117465109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van den Berg R, Awh E, Ma WJ. Factorial comparison of working memory models. Psychol Rev. 2014;121:124–149. doi: 10.1037/a0035234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang W, Luck SJ. Discrete fixed-resolution representations in visual working memory. Nature. 2008;453:233–235. doi: 10.1038/nature06860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bays PM, Catalao RFG, Husain M. The precision of visual working memory is set by allocation of a shared resource. J Vis. 2009;9:6. doi: 10.1167/9.10.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bays PM, Gorgoraptis N, Wee N, Marshall L, Husain M. Temporal dynamics of encoding, storage, and reallocation of visual working memory. J Vis. 2011;11:6. doi: 10.1167/11.10.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gorgoraptis N, Catalao RFG, Bays PM, Husain M. Dynamic updating of working memory resources for visual objects. J Neurosci. 2011;31:8502–8511. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0208-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kumar S, Joseph S, Pearson B, Teki S, Fox ZV, Griffiths TD, Husain M. Resource allocation and prioritization in auditory working memory. Cogn Neurosci. 2013;4:12–20. doi: 10.1080/17588928.2012.716416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joseph S, Iverson P, Manohar S, Fox Z, Scott SK, Husain M. Precision of working memory for speech sounds. Q J Exp Psychol. 2015;68:2022–2040. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2014.1002799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joseph S, Kumar S, Husain M, Griffiths TD. Auditory working memory for objects vs. features. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:13. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2015.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buhusi CV, Meck WH. Relative time sharing: New findings and an extension of the resource allocation model of temporal processing. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2009;364:1875–1885. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buhusi CV, Meck WH. Relativity theory and time perception: single or multiple clocks? PLoS ONE. 2009;4(7):e6268. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joseph S, Teki S, Kumar S, Husain M, Griffiths TD. Resource allocation models of auditory working memory. Brain Res. 2016;1640:183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2016.01.044. [• A review of resource allocation models of working memory as related to timing.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teki S, Griffiths TD. Working memory for time intervals in auditory rhythmic sequences. Front Psychol. 2014;5:1329. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01329. [• State-of-the-art discussion of the mechanisms involved in the memory for time intervals.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibbon J, Church RM, Meck WH. Scalar timing in memory. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1984;423:52–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1984.tb23417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lejeune H, Wearden JH. Scalar properties in animal timing: conformity and violations. Quart J Exp Psych. 2006;59:1875–1908. doi: 10.1080/17470210600784649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi Z, Church RM, Meck WH. Bayesian optimization of time perception. Trends Cogn Sci. 2013;17:556–564. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wearden JH, Lejeune H. Scalar properties in human timing: conformity and violations. Quart J Exp Psych. 2008;61:569–587. doi: 10.1080/17470210701282576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manohar SG, Husain M. Working memory for sequences of temporal durations reveals a volatile single-item store. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1655. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01655. [• Important investigation of the working memory processes involved in sequences of temporal intervals.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ivry RB, Schlerf JE. Dedicated and intrinsic models of time perception. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meck WH, Penney TB, Pouthas V. Cortico-striatal representation of time in animals and humans. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2008;18:145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Teki S, Grube M, Griffiths TD. A unified model of time perception accounts for duration-based and beat-based timing mechanisms. Front Integr Neurosci. 2012;5:90. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2011.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rao SM, Mayer AR, Harrington DL. The evolution of brain activation during temporal processing. Nat Neurosci. 2001;4:317–323. doi: 10.1038/85191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coull JT, Nazarian B, Vidal F. Timing, storage, and comparison of stimulus duration engage discrete anatomical components of a perceptual timing network. J Cogn Neurosci. 2008;20:2185–2197. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teki S, Griffiths TD. Brain bases of working memory for time intervals in rhythmic sequences. Front Neurosci. 2016;10:239. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00239. [• Investigation of the memory processes involved in the coding of durations within rhythmic sequences.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Teki S, Grube M, Kumar S, Griffiths TD. Distinct neural substrates of duration-based and beat-based auditory timing. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3805–3381. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5561-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petter EA, Lusk NA, Hesslow G, Meck WH. Interactive roles of the cerebellum and striatum in sub-second and supra-second timing: support for an initiation, continuation, adjustment, and termination (ICAT) model of temporal processing. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2016;71:739–755. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Allman MJ, Meck WH. Pathophysiological distortions in time perception and timed performance. Brain. 2012;135:656–677. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr210. [• Examines the striatal beat-frequency (SBF) model of interval timing from the point of view of different neurological and psychological conditions (e.g., Parkinson’s disease, schizophrenia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and autism). The review also describes the basics of the SBF model and provides full simulation parameters in the appendix.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lustig C, Matell MS, Meck WH. Not “just” a coincidence: Frontal-striatal synchronization in working memory and interval timing. Memory. 2005;13:441–448. doi: 10.1080/09658210344000404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matell MS, Meck WH. Cortico-striatal circuits and interval timing: coincidence detection of oscillatory processes. Cogn Brain Res. 2004;21(2):139–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lisman JE, Jensen O. The θ-γ neural code. Neuron. 2013;77(6):1002–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emmons EB, Ruggiero RN, Kelley RM, Parker KL, Narayanan NS. Corticostriatal field potentials are modulated at delta and theta frequencies during interval-timing task in rodents. Front Psychol. 2016;7:459. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heusser AC, Poeppel D, Ezzyat Y, Davachi L. Episodic sequence memory is supported by a theta-gamma phase code. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19(10):1374–1380. doi: 10.1038/nn.4374. [• State-of-the-art investigation of how memory can be enabled by a neural oscillation phase code.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liebe S, Hoerzer GM, Logothetis NK, Rainer G. Theta coupling between V4 and prefrontal cortex predicts visual short-term memory performance. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15(3):456–462. doi: 10.1038/nn.3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bartolo R, Prado L, Merchant H. Information processing in the primate basal ganglia during sensory-guided and internally driven rhythmic tapping. J Neurosci. 2014;34(11):3910–3923. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2679-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fujioka T, Ross B, Trainor LJ. Beta-band oscillations represent auditory beat and its metrical hierarchy in perception and imagery. J Neurosci. 2015;35(45):15187–15198. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2397-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kononowicz TW, van Rijn H. Single trial beta oscillations index time estimation. Neuropsychologia. 2015;75:381–389. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coull JT, Cheng RK, Meck WH. Neuroanatomical and neurochemical substrates of timing. Neuropsychopharmacology Rev. 2011;36:3–25. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.113. [• Reviews how neuronal firing rates in both the striatum and interconnected areas of the frontal cortex vary as a function of signal duration. Describes a neurophysiological mechanism for the representation of time in the excitatory-inhibitory balance among distinct subtypes of striatal ‘time cells’ – including median spiny neurons (MSNs) and tonically active neurons (TANs).] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Goel A, Buonomano DV. Temporal interval learning in cortical cultures is encoded in intrinsic network dynamics. Neuron. 2016;91(2):320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Johansson F, Jirenhed DA, Rasmussen A, Zucca R, Hesslow G. Memory trace and timing mechanism localized to cerebellar Purkinje cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(41):14930–14934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415371111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lusk NA, Petter EA, MacDonald CJ, Meck WH. Cerebellar, hippocampal, and striatal time cells. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2016;8:186–192. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eichenbaum H, Cohen NJ. Can we reconcile the declarative memory and spatial navigation views on hippocampal function. Neuron. 2014;83:764–770. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.MacDonald CJ. Prospective and retrospective duration memory in the hippocampus: is time in the foreground or background? Philos Trans R Soc B. 2014;369 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2012.0463. 20120463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.MacDonald CJ, Fortin NJ, Sakata S, Meck WH. Retrospective and prospective views on the role of the hippocampus in interval timing and memory for elapsed time. Timing Time Percept. 2014;2:51–61. [Google Scholar]

- 58.MacDonald CJ, Carrow S, Place R, Eichenbaum H. Distinct hippocampal time cell sequences represent odor memories in immobilized rats. J Neurosci. 2013;33(36):14607–14616. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1537-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eichenbaum H. Time cells in the hippocampus: a new dimension for mapping memories. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:732–744. doi: 10.1038/nrn3827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hasselmo ME, editor. How we remember: brain mechanisms of episodic memory. MIT Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Howard MW, MacDonald CJ, Tiganj Z, Shankar KH, Du Q, Hasselmo ME, Eichenbaum H. A unified mathematical framework for coding time, space, and sequences in the hippocampal region. J Neurosci. 2014;34:4692–4707. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5808-12.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang Y, Romani S, Lustig B, Leonardo A, Pastalkova E. Theta sequences are essential for internally generated hippocampal firing fields. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:282–288. doi: 10.1038/nn.3904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Itskov V, Curto C, Pastalkova E, Buzsaki G. Cell assembly sequences arising from spike threshold adaptation keep track of time in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2011;31:2828–2834. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3773-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mankin EA, Diehl GW, Sparks FT, Leutgeb S, Leutgeb JK. Hippocampal CA2 activity patterns change over time to a larger extent than between spatial contexts. Neuron. 2015;85:190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kraus BJ, Brandon MP, Robinson RJ, 2nd, Connerney MA, Hasselmo ME, Eichenbaum H. During running in place, grid cells integrate elapsed time and distance run. Neuron. 2015;88:578–589. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2015.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vaidya SP, Johnston D. Temporal synchrony and gamma-to-theta power conversion in the dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurons. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1812–1820. doi: 10.1038/nn.3562. [• Provides a novel mechanism (HCN channels) for integrating information across thousands of synapses of pyramidal neurons, which is an essential component to make temporally precise calculations.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burgess N, Barry C, O’Keefe J. An oscillatory interference model of grid cell firing. Hippocampus. 2007;17(9):801–812. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Burgess N. Grid cells and theta as oscillatory interference: theory and predictions. Hippocampus. 2008;18(12):1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.

- 70.Hsieh L-T, Gruber MJ, Jenkins LJ, Ranganath C. Hippocampal activity patterns carry information about objects in temporal context. Neuron. 2014;81:1165–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Akam T, Kullmann DM. Oscillations and filtering networks support flexible routing of information. Neuron. 2010;67:308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Akam T, Kullmann DM. Oscillatory multiplexing of population codes for selective communication in the mammalian brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:111–122. doi: 10.1038/nrn3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Düzel E, Penny WD, Burgess N. Brain oscillations and memory. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:143–149. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Palva JM, Monto S, Kulashekhar S, Palva S. Neuronal synchrony reveals working memory networks and predicts individual memory capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:7580–7585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0913113107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Palva S, Kulashekhar S, Hämäläinen M, Palva JM. Localization of cortical phase and amplitude dynamics during visual working memory encoding and retention. J Neurosci. 2011;31:5013–5025. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5592-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Palva JM, Palva S. Infra-slow fluctuations in electrophysiological recordings, blood-oxygenation-level-dependent signals, and psychophysical time series. NeuroImage. 2012;62:2201–2211. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Engel AK, Fries P. Beta-band oscillations-signalling the status quo? Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2010;20:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Engel AK, Fries P, Singer W. Dynamic predictions: oscillations and synchrony in top-down processing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:704–716. doi: 10.1038/35094565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gray CM, König P, Engel AK, Singer W. Oscillatory responses in cat visual cortex exhibit inter-columnar synchronization which reflects global stimulus properties. Nature. 1989;338:334–337. doi: 10.1038/338334a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.O’Neill J, Pleydell-Bouverie B, Dupret D, Csicsvari J. Play it again: reactivation of waking experience and memory. Trends Neurosci. 2010;33:220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rasch B, Born J. About sleep’s role in memory. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:681–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00032.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rothschild G, Eban E, Frank LM. A cortical–hippocampal–cortical loop of information processing during memory consolidation. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:251–259. doi: 10.1038/nn.4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gilden DL. Cognitive emissions of 1/f noise. Psychol Rev. 2001;108:33–56. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gilden DL, Thornton T, Mallon MW. 1/f noise in human cognition. Science. 1995;267:1837–1839. doi: 10.1126/science.7892611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Farrell S, Wagenmakers E-J, Ratcliff R. 1/f noise in human cognition: is it ubiquitous, and what does it mean? Psychon Bull Rev. 13(4):737–741. doi: 10.3758/bf03193989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Buhusi CV, Meck WH. What makes us tick? functional and neural mechanisms of interval timing. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:755–765. doi: 10.1038/nrn1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Matthews WJ, Terhune DB, van Rijn H, Eagleman DM, Sommer MA, Meck WH. Subjective duration as a signature of coding efficiency: emerging links among stimulus repetition, prediction coding, and cortical GABA levels. Timing Time Percept Rev. 2014;1(5):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kononowicz TW, van Rijn H, Meck WH. Timing and time perception: a critical review of neural timing signatures before, during, and after the to-be-timed interval. In: Wixted J, Serences J, editors. Sensation, perception and attention, Volume II – Stevens’ handbook of experimental psychology and cognitive neuroscience. 4th ed. New York: Wiley; 2017. pp. 1–35. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Burgess N, Hitch GJ. Memory for serial order: a network model of the phonological loop and its timing. Psychol Rev. 1999;106:551–581. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brown GD, Preece T, Hulme C. Oscillator-based memory for serial order. Psychol Rev. 2000;107:127–181. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.107.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hartley T, Hurlstone MJ, Hitch GJ. Effects of rhythm on memory for spoken sequences: a model and tests of its stimulus-driven mechanism. Cogn Psychol. 2016;87:135–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gilbert RA, Hitch GJ, Hartley T. Temporal precision and the capacity of auditory– verbal short-term memory. Quart J Exp Psychol. 2017:1–16. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2016.1239749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hasselmo ME, Hinman JR, Dannenberg H, Stern CE. Models of spatial and temporal dimensions of memory. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2017;17:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]