Abstract

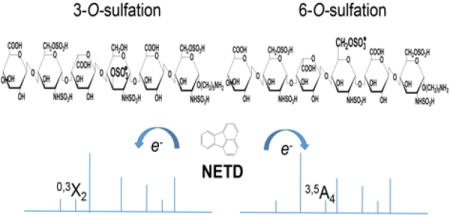

Among dissociation methods, negative electron transfer dissociation (NETD) has proven the most useful for glycosaminoglycan (GAG) sequencing because it produces informative fragmentation, a low degree of sulfate losses, high sensitivity, and translatability to multiple instrument types. The challenge, however, is to distinguish positional sulfation. In particular, NETD has been reported to fail to differentiate 4-O- versus 6-O-sulfation in chondroitin sulfate decasaccharide. This raised the concern of whether NETD is able to differentiate the rare 3-O-sulfation from predominant 6-O-sulfation in heparan sulfate (HS) oligosaccharides. Here we report that NETD generates highly informative spectra that differentiate sites of O-sulfation on glucosamine residues, enabling structural characterizations of synthetic HS isomers containing 3-O-sulfation. Further, lyase-resistant 3-O-sulfated tetrasaccharides from natural sources were successfully sequenced. Notably, for all of the oligosaccharides in this study, the successful sequencing is based on NETD tandem mass spectra of commonly observed deprotonated precursor ions without derivatization or metal cation adduction, simplifying the experimental workflow and data interpretation. These results demonstrate the potential of NETD as a sensitive analytical tool for detailed, high-throughput structural analysis of highly sulfated GAGs.

Graphical abstract

Introduction

The heparin (Hep) and heparan sulfate (HS) are composed of alternating glucosamine (GlcN) and uronic acid (HexA) residues and play significant roles in anticoagulation, cell proliferation, angiogenesis, tumor metastasis [1, 2], growth of neurons [3] and development of salivary gland [4]. While the protein binding properties of Hep/HS depend on fine structure, their non-template-driven biosynthesis in the Golgi apparatus results in heterogeneity that poses serious analytical challenges [2, 5]. In Hep/HS, sulfate groups can be installed at C2 of the uronic acid and N-, C6, and C3 of the glucosamine residues by 2-O-sulfotransferase, N-sulfotransferases, 6-O-sulfotransferases, and 3-O-sulfotransferases (3OSTs), respectively. Of these, 3-O-sulfation is considered to be the last modification in the biosynthetic pathway [2].

Despite the fact that 3-O-sulfation is a relatively rare modification [6–10], the 3OSTs comprise the largest HS sulfotransferase family [11]. Seven 3OSTs are found in most vertebrates, each having different substrate selectivity, thus providing specialized biological domains. The 3OST enzymes have been grouped into two classes [12]. The “AT type” 3OST1 produces 3-O-sulfation on GlcN with unsulfated uronic acid at the non-reducing side (HexA-GlcNS3S±6S), forming the well-known anticoagulant domain of heparin [13]. By contrast, “gD type” 3OST2, 3a, 3b, 4 and 6 can produce 3-O-sulfation on GlcN with a 2-O sulfated iduronic acid (IdoA) at the non-reducing side (IdoA2S-GlcNS3S±6S), generating binding sites for glycoprotein gD of type I herpes simplex virus [14–17]. Besides these two examples, very few proteins or biological systems have been described that are influenced by 3-O-sulfation, and the prevalence of 3-O-sulfation in natural heparan sulfates is largely unknown due to the difficulty in obtaining large quantities of HS for structural analyses and the lack of technology to identify the 3-O-sulfate group [12].

Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) using electrospray ionization (ESI) offers high sensitivity, accuracy and throughput [18, 19]. Compared to collision induced dissociation (CID), electron-activated dissociation (ExD), including electron detachment dissociation (EDD) and negative electron transfer dissociation (NETD), produces more informative fragments for GAG sequence analysis, and enables the determination of the sulfate and acetate positions on each residue, as well as the occurrence and position(s) of uronic acid epimers [20–33]. A recent study of GAG analysis showed that Orbitrap NETD produces tandem mass spectra with most of the advantages of those produced by EDD using Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance instruments (FTICR), particularly with respect to diminished sulfate losses and a short duty cycle compatible with on-line LC-MS analysis [34]. While it is possible to sequence permethylated, desulfated, and acetylated HS saccharides using LC-CID-MS [35, 36], the yield of derivatization for tetrasaccharides was 29.5% [37].

Though NETD sequencing of HS oligosaccharides with varied structure had been reported previously, few published works focus on the fragmentation of HS oligosaccharides containing 3-O-sulfation. In this present work, we examine the application of NETD sequencing of synthetic HS isomers containing 3-O-sulfation and demonstrate the change of fragmentation for varied O-sulfation on GlcN. We further demonstrate the application of NETD sequencing of the lyase-resistant tetrasaccharides bearing 3-O-sulfated glucosamine at the reducing end from porcine intestinal mucosa HS (HSPIM).

Experimental

Materials

HSPIM was purchased from Celsus Laboratories, Inc. (Cincinnati, OH). Heparin lyase II was purchased from New England Biolabs, Inc. (Ipswich, MA).

Preparation of Synthetic Heparan sulfate oligosaccharides

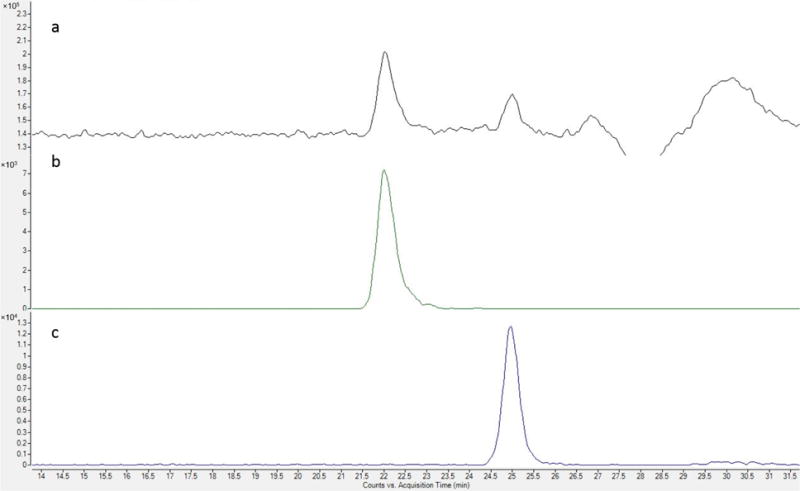

Synthetic HS tetrasaccharides, T1 and T3, and hexasaccharides, H1-3, were synthesized and purified as previously described [38]. Compounds T2 and T4 are obtained from lyase II digestion of compound H1 and compound H3, respectively, using the method shown below with a single Acquity UPLC BEH column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, Waters Corp., Milford, MA) with an elution of 35 min. The size exclusion chromatography ion chromatograms for lyase II digested H3 are shown in Figure 1. Tetrasaccharides containing a 3-O-sulfate group on their reducing-end GlcN residue are completely resistant to heparin lyase II digestion, allowing the selective digestion to produce T2 and T4. All of these synthetic product structures were further confirmed by accurate mass measurement by FTICR MS.

Figure 1.

Size-exclusion chromatography of lyase II digest of H3: a, total ion chromatogram of lyase II digest of H3; b, extracted ion chromatogram (EIC) of m/z 544.99, [M − 2H]2− of lyase II-generated T4; c, EIC of m/z 581.10, [M − H]− of ΔHexA-GlcNS6S-R, R = (CH2)5NH2

Preparation of native HS oligosaccharides by lyase II digestion

HSPIM (100 μg) was dissolved in 100 μL of digestion buffer (50 mM ammonium formate, 2 mM calcium chloride, pH 6.0) and digested by heparin lyase II (10 mU) at 37 °C for 24 h. Tandem Acquity UPLC BEH columns (4.6 mm × 150 mm and 4.6 mm × 300 mm), connected to a chemically regenerated ion suppressor (ACRS 500, 2 mm, Thermo Fisher Scientific/Dionex, San Jose, CA) were used to separate the resistant tetrasaccharides from the predominant disaccharides using conditions previously reported [39]. Briefly, the mobile phase contained 50 mM ammonium formate (pH 6.8) in methanol/water (80:20). The constituents were eluted in 90 min at a flow rate of 75 μL/min. A solution of 100 mM sulfuric acid was used to regenerate the suppressor. The effluent was monitored by UV at 232 nm and an Agilent 6520 quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Santa Clara, CA). The fractions corresponding to the tetramers were collected and vacuum-dried.

Mass spectrometry analysis

Negative electron transfer dissociation (NETD) was performed on a 12-T solariX hybrid Qh-FTICR mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) [28]. Each synthetic hexasaccharide with alkyl-linker at the reducing end was dissolved in 5% isopropanol and 0.2% ammonia solution to a concentration of 5 pmol/μL. Ammonia solution was not applied to the tetrasaccharides, including both synthetic and native tetrasaccharides from HSPIM, to prevent the unwanted peeling reaction [40].

Fluoranthene cation radicals were generated in the chemical ionization source in the presence of argon. A 200 ms reagent accumulation time and a 50 ms reaction time were typically used. 100 scans were averaged to obtain a tandem mass spectrum for each sample. External calibration using sodium-TFA clusters resulted in a mass accuracy of 5 ppm or better. Peak picking and fragment assignment were achieved using the in-house developed software GAGfinder (publically available at www.bumc.bu.edu/msr). Glycosidic and major cross-ring fragments were also checked manually using Glycoworkbench [41]. Due to the large number of products formed by NETD, only the fragments with no neutral loss were annotated in the cleavage maps. Fragment ions are labeled using the Domon-Costello nomenclature [42] with an extension developed by Wolff-Amster [21]. Note that the collision cell parameters were optimized for each precursor to minimize sulfate loss and make better isolation of precursor for NETD. Thus differences in product ion abundances occurred despite the use of the same NETD reagent and reaction times.

Results and Discussion

NETD characterization of the synthetic tetrasaccharides

Sulfate loss during fragmentation is a major problem of MS/MS-based sequencing of Hep/HS oligosaccharides [18]. Efforts have been made recently to address this problem, including precursor super-charging [43], chemical derivatization [44] and H-Na exchange [21, 27, 45]. In the prior work, it was demonstrated that it is necessary to choose an ion that presents all sulfates in a deprotonated state in EDD [27]. Here, the [M − 4H]4− precursors of the tetrasulfated tetramers, which allowed all the sulfate groups to be deprotonated, were used for NETD analyses.

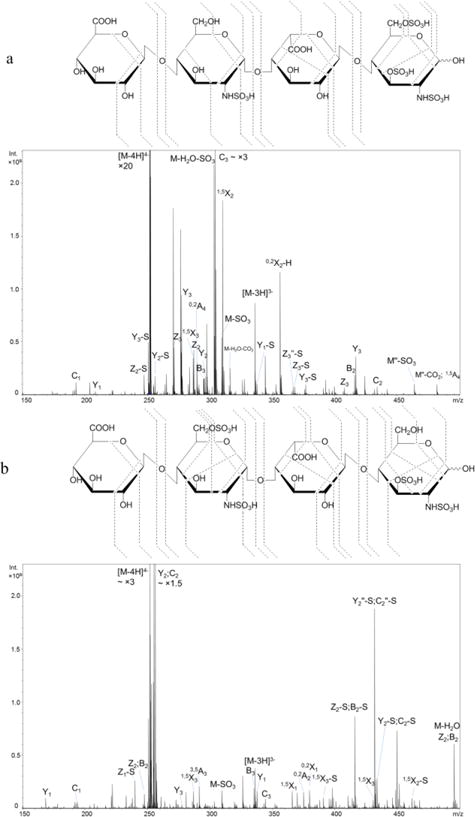

Figure 2a shows the NETD spectrum of the quadruply deprotonated T1. Fragments from glycosidic bond cleavages can be found in their fully sulfated state, except for Z1. The presence of trisulfated Y1 ions at both 1- and 2- charge state correctly locates the three sulfate groups on the reducing end glucosamine. Additionally, these sulfate groups can be identified as N-sulfation, 3-O-sulfation and 6-O-sulfation, respectively. N-sulfation can be assigned by the 0,2A4 ion, and 3-O-sulfation can be assigned by the mass difference between 0,2A4 and 0,3A4 ions. The 6-O-sulfation can be assigned by the mass difference between 0,3A4 and C3 ions. While assigning the sulfation positions on a trisulfated glucosamine residue is unnecessary due to the known biosynthetic pathway, it informs an understanding of the dissociation of the glucosamine residue. It can be determined that the internal glucosamine is N-sulfated by the mass difference between the 0,2A2 and B2/C2 ions. Notably, the 0,3A ion is not found on the internal glucosamine residue, indicating such 0,3A cleavage may be specific for glucosamine with 3-O-sulfation. No sulfate groups are present on either of glucuronic acid.

Figure 2.

NETD cleavage maps and tandem mass spectra of the [M − 4H]4− precursor of synthetic HS tetrasulfated tetramers: a, T1, GlcA-GlcNS-IdoA-GlcNS3S6S; b, T2, GlcA-GlcNS6S-IdoA-GlcNS3S.

Compound T2, the tetrasulfated tetramer obtained from the lyase II digestion of hexamer H1, is a sulfation positional isomer of T1. Unlike T1, this tetramer has two disulfated glucosamine residues instead of one N-sulfated glucosamine (GlcNS) and one trisulfated glucosamine (GlcNS3S6S). The annotated NETD spectrum of [M − 4H]4− precursor is shown in Figure 2b. With all possible fully-sulfated glycosidic fragments present in the spectrum, the number of sulfate groups on each residue can be assigned. The presence of N-sulfation on both glucosamine residues is confirmed by the mass difference between the corresponding 0,2A and B ions. Of note is the fragmentation variation for these disulfated GlcN residues. The internal GlcN residue containing N-sulfation and 6-O-sulfation produces the 3,5A ion, which was found in many cases reported previously [24, 26, 28, 34, 46] and is usually used for the identification of the 6-O-sulfation. By contrast, the 3,5A4 ion is absent from the reducing terminus GlcN residue which contains N-sulfation and 3-O-sulfation. Instead, 1,4A4 and 0,3X0 ions, which are not the preferred fragment ions according to the previous studies of HS, are present. We conclude that these fragments are characteristic of the presence of 3-O-sulfation. Direct comparison of fragmentation patterns on GlcN containing 3-O- versus 6-O-sulfation at the same residue position of tetramers cannot be achieved at present due to the limited availability of isomeric HS oligosaccharide standards and the infeasibility to obtain the ideal isomer from H2 with the same strategy. The fragmentation variations on GlcN with different O-sulfation modifications on hexamers, of which the only difference is the sulfation position on internal GlcN, are illustrated in the section below.

As discussed in the introduction, like AT-type, gD-type 3-O-sulfation can also be synthesized in cells. With the additional 2-O-sulfation on the non-reducing side IdoA of 3-O-sulfation containing GlcN, T3 has a tetrasulfated disaccharide unit at the reducing end, forming a highly sulfated domain. In order to minimize dissociation of sulfate groups, it is necessary to dissociate either the [M − 5H]5− or [M − 5H + Na]4− precursor ion. Figure S1 shows NETD can produce abundant ions, including both glycosidic bond cleavage and cross-ring fragments, on these two precursors, allowing unambiguous assignment of sulfation positions.

However, the precursor [M − 5H]5− is not a favorable charge state for the pentasulfated tetrasaccharide T3. It took extremely long time to accumulate enough ions for NETD because of the low intensity (shown in Figure S2). Though precursor [M − 5H + Na]4− had the acceptable abundance via direct infusion, it is also less favorable when an online LC system is connected, and thus it cannot be used for the robust LC-NETD analysis in the future. By balancing the charge state and ion abundance, the [M − 4H]4− precursor was used. It is found, aside from precursors in which complete deprotonation on sulfate groups is achieved, the [M − 4H]4− precursor with one protonated sulfate group can also produce abundant fragments during the dissociation and therefore enables the unambiguous assignment of all sulfate positions. While the intensities of fully sulfated ions are less than those with sulfate loss(es) in many fragments, the patterns sufficed to assign sulfation positions unambiguously. As shown in Figure 3a, two N-sulfation positions and 6-O-sulfation and 3-O-sulfation on the reducing end GlcN residue can be assigned by 0,2A2, 0,2A4, 3,5A4 and 0,3X0 ions, respectively. As discussed above, fragment ion 0,3X0 is present on GlcN at reducing end, indicating that fragment 0,3A/X is diagnostic for 3-O-sulfation containing GlcN. This is confirmed by all of the 3-O-sulfated saccharides in this study, including those from both synthetic and biological sources.

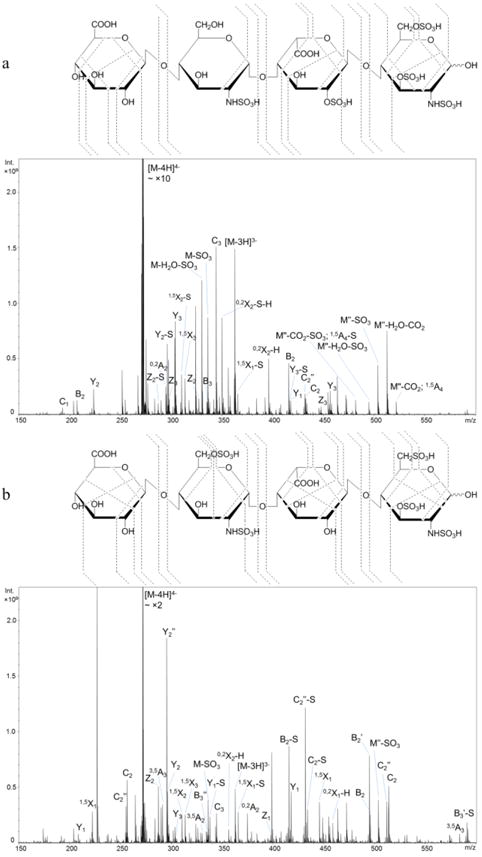

Figure 3.

NETD cleavage maps and tandem mass spectra of the [M − 4H]4− precursor of synthetic HS pentasulfated tetramers: a, T3, GlcA-GlcNS-IdoA2S-GlcNS3S6S; b, T4, GlcA-GlcNS6S-IdoA-GlcNS3S6S.

The assignment of 2-O-sulfation on IdoA is straightforward using glycosidic bond cleavage and knowledge of HS biosynthesis. It is also confirmed by the cross-ring fragment ion 0,2A3. Apparently, the 2-O-sulfation on IdoA does not impede assignment by both glycosidic cleavage and cross-ring fragment ions. T4, the pentasulfated tetramer obtained from H3 by lyase II digestion, contains an internal GlcNS6S and a reducing end GlcNS3S6S. The NETD fragmentation map of precursor [M − 4H]4− is shown in Figure 3b. Fully sulfated glycosidic fragments indicate the number of sulfate groups on each residue of T4 and show the difference in positional sulfation between the two pentasulfated tetramers, T3 and T4. The presence of N-sulfation and 6-O-sulfation on the internal GlcN residue can be confirmed by 0,2A2 and 3,5A6 ions, while 0,2A4, 3,5A4 and 0,3X0 ions confirm the sulfate positions on the terminal GlcN.

It was reported that NETD is more tolerant for the remaining free proton on the precursor and results in higher sulfate retention than EDD [28]. We find that NETD produces sufficient abundances of informative fragments for highly sulfated HS oligosaccharides, defined here as those in which the number of sulfate groups per disaccharide is greater than two, even for charge states where not all of the sulfate groups are deprotonated. It therefore appears that NETD will be useful as a tool for online LC-MS sequencing of HS oligosaccharides where the charge state distribution of ions is usually limited by the solvent of choice.

NETD characterization of the synthetic hexasaccharides

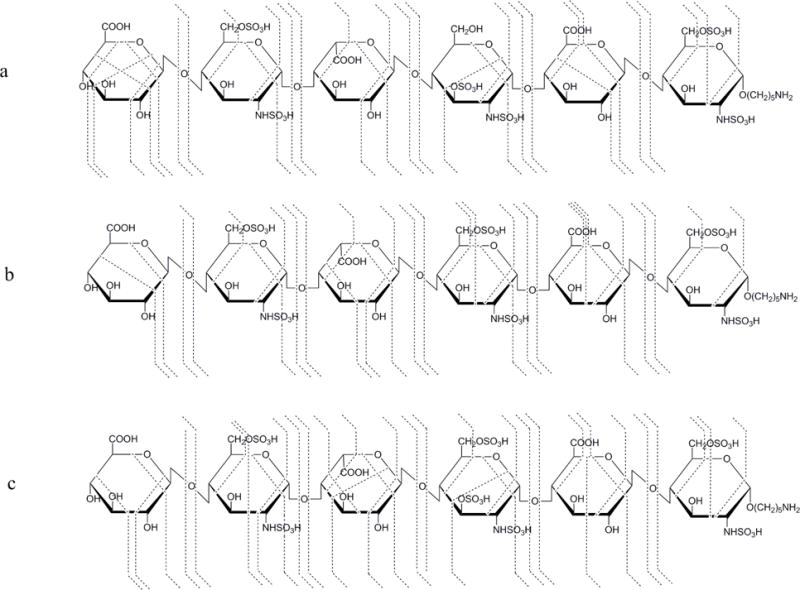

It is more challenging to differentiate the sulfation position on the GlcN residue (6-O-sulfation versus 3-O-sulfation) for saccharides with unsubstituted O-sites because the detection of cross-ring fragments that are often low in abundance is required. We used synthetic standards to demonstrate the ability of NETD to address this issue and to show the fragmentation behavior of differently sulfated GlcN residues. As shown in Figure 4, compounds H1, H2 and H3 contain the same GlcA-GlcNS6S disaccharide units at both the non-reducing and reducing ends. The only difference among these three hexamers occurs on GlcN residue of the internal disaccharide, as GlcNS3S versus GlcNS6S versus GlcNS3S6S. The alkyl linker at the reducing end helps to definitively differentiate reducing-end fragments from both sides. NETD was performed on the most abundant [M − 5H]5− precursor ions of each compound (Figure 4 and Figure S3). Though complete deprotonation on sulfate groups is not achieved in any of the precursors, the set of glycosidic bond cleavages observed indicates the number of sulfate group on each residue. Of great interest is the fragmentations on the GlcN of the internal disaccharide of these hexamers. Aside from the 1,5X2 ion, which does not provide information on the position of sulfate(s) within the same residue, fragment ions 0,2A4 and 0,3X2 are found on the GlcNS3S of H1 while 0,2A4 and 3,5A4 are found for the internal GlcNS6S of H2. All three ions are found when GlcN was fully modified with N-sulfation, 3-O-sulfation and 6-O-sulfation in H3. This is consistent with the conclusion that radical-driven dissociation generates 3,5A and 0,3X from the site of 6-O-sulfation and 3-O-sulfation, respectively. Further evidence can be found from the cleavages of the terminal GlcN residues on these hexamers. The 3,5A and 0,2A ions can be found on the terminal GlcNS6S residues of each hexamer while 0,3X ions are absent.

Figure 4.

NETD cleavage maps of the [M − 5H]5− precursor of synthetic HS hexamers: a, H1, GlcA-GlcNS6S-IdoA-GlcNS3S-GlcA-GlcNS6S; b, H2, GlcA-GlcNS6S-IdoA-GlcNS6S-GlcA-GlcNS6S; c, H3, GlcA-GlcNS6S-IdoA-GlcNS3S6S-GlcA-GlcNS6S.

Notably, NETD analysis of the hexasulfated H2 was previously achieved on an Orbitrap instrument using the precursor [M − 6H + Na]5−, where all of the six sulfate groups are deprotonated [34]. Here, the incompletely-deprotonated but easily-observed precursor [M − 5H]5− also produces sufficiently abundant fragments for structural characterization. Moreover, NETD of the precursor [M − 5H]5− of H3, which contains two free protons on sulfate groups, also allows the definitive structural sequencing. With this observation, we are able to identify highly-sulfated lyase-resistant tetramers, which contain up to 3 sulfate groups per disaccharide, using the most abundant [M − 4H]4− precursor in the next section.

NETD characterization of the native tetrasaccharides

The anticoagulant activities of heparin depend on the presence of 3-O-sulfation within the chain. The examination of domains bearing 3-O-sulfation and the structural variability of the AT-binding sites within heparin are simplified by analysis of the tetrasaccharides, which are resistant to lyase II digestion. Compositions of the resistant tetrasaccharides from HSPIM, the major source of pharmaceutical heparins, were reported previously by using reversed-phase ion pairing (RPIP) chromatography [9, 47] and hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) [10], in some of which the qualitative and/or quantitative analysis were achieved using in-house prepared standards. Recently, a study of these tetramers from HSPIM using NMR along with combined CID/EDD was reported [46], solely based on the spectra without using standards, broadening the applicability; however, the large amount of samples and the multi-step purification for NMR is time consuming. The necessity of judicious precursor selection to retain the labile sulfate group for CID and EDD increases the difficulty and is not compatible with high-throughput analysis. Here, an off-line size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) separation with NETD using deprotonated precursor ions enabled rapid characterization of these lyase-resistant and 3-O-sulfation containing tetrasaccharides.

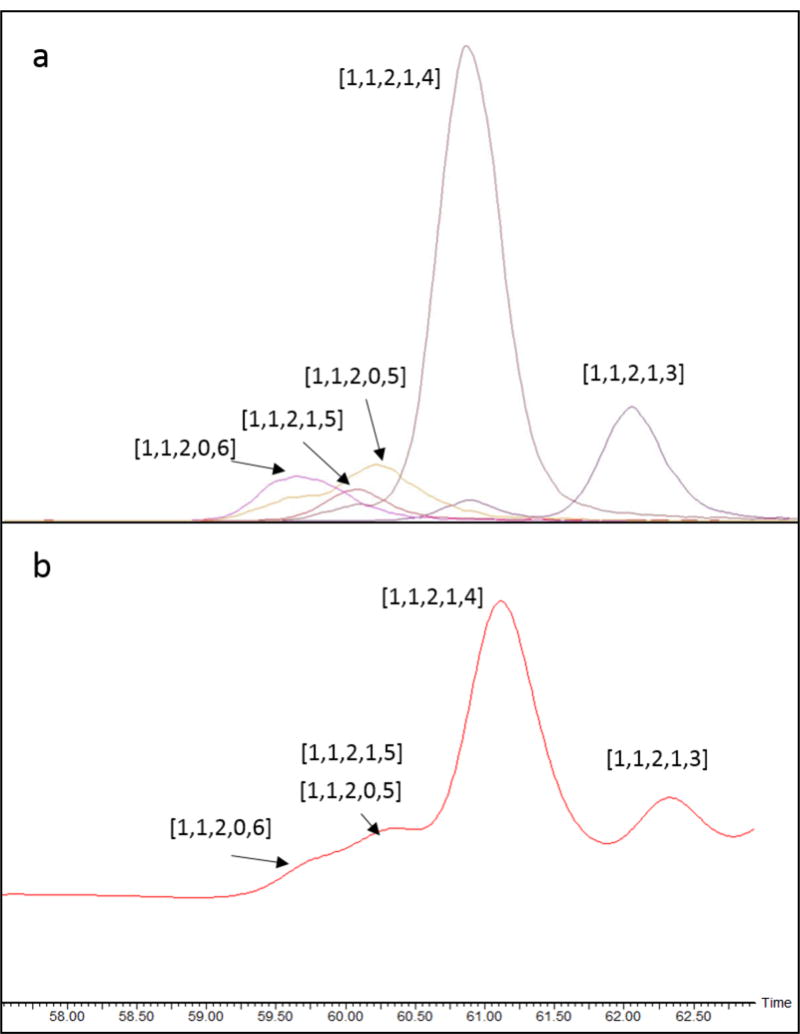

As shown in Table 2 and Figure 5, five tetramer compositions were found. The abundances varied from 0.14% to 3.54%, indicating the structural complexity of the AT-binding domains of heparin. Though the abundances of the compositions differ slightly from reports using different methods [10, 46], composition [1, 1, 2, 1, 4], where [A,B,C,X,Y] = [ΔHexA, HexA, GlcN, Ac, SO3], is always the most abundant. According to the ionization behaviors(Table 2), the [M − 3H]3− precursor was used for NETD of [1, 1, 2, 1, 3] and the [M − 4H]4− for other compositions (Figure S4). Shown in Figure 6 are the NETD cleavage maps of 4 tetramers from HSPIM, which are identified using NETD. The full set of glycosidic bond cleavages and abundant cross-ring fragments with good structural coverage are found in each spectrum, allowing the assignment of the structures of these tetramers, including the number of sulfate, the position of acetylation and sulfation on each residue.

Table 2.

Tetrasaccharides found from size-exclusion chromatography and their precursor distribution in mass spectrometry

| Composition | Relative abundance (%)* | Ratio of [M − 4H]4−/[M − 3H]3−** |

|---|---|---|

| [1,1,2,1,3]*** | 1.30 | 0.07 |

| [1,1,2,1,4] | 3.54 | 0.60 |

| [1,1,2,1,5] | 0.14 | 1.61 |

| [1,1,2,0,5] | 0.45 | 1.04 |

| [1,1,2,0,6] | 0.24 | 1.75 |

Relative abundance is normalized to the total identified oligosaccharides peak area (data not shown)

The ratio may vary among instruments.

[A,B,C,X,Y] = [ΔHexA, HexA, GlcN, Ac, SO3]

Figure 5.

Size-exclusion chromatography of the resistant tetrasaccharides from HSPIM lyase II digest. a, EICs; b, UV absorbance at 232 nm.

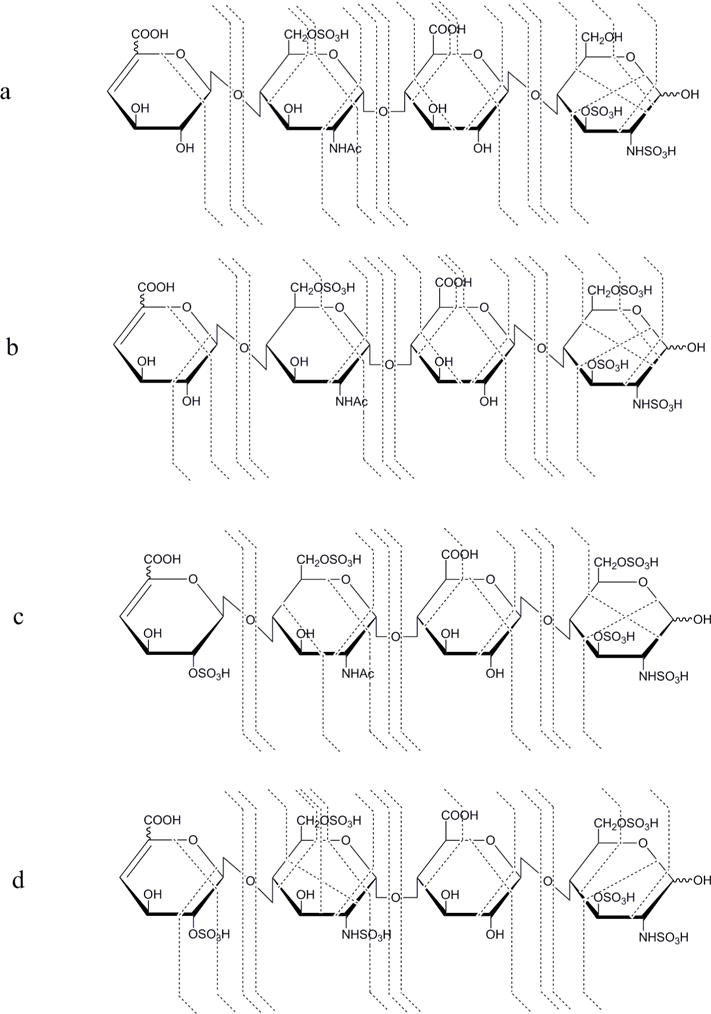

Figure 6.

NETD cleavage maps of the lyase resistant tetramers from HSPIM: a, ΔHexA-GlcNAc6S-GlcA-GlcNS3S, [M − 3H]3− ; b, ΔHexA-GlcNAc6S-GlcA-GlcNS3S6S, [M − 4H]4− ; c, ΔHexA2S-GlcNAc6S-GlcA-GlcNS3S6S, [M − 4H]4− ; d, ΔHexA2S-GlcNS6S-GlcA-GlcNS3S6S, [M − 4H]4−.

In this study, uronic acid close to the reducing end in native tetramers is considered as glucuronic acid (GlcA), consistent with literature reports [46]. As shown in Figure 6a, in [1,1,2,1,3], acetylation and one sulfation are found on the internal GlcN by the mass difference of B1/C1 and B2/C2, or Y3/Z3 and Y2/Z2, while disulfated GlcN is found at the reducing end by Y1/Z1. N-Sulfation and 3-O-sulfation on GlcN at the reducing end are assigned using 0,3X0 or 1,4A4 ions while the 6-O-sulfation on internal GlcN, is confirmed by the 3,5A2 ion. In [1,1,2,1,4], one additional sulfate group is assigned on GlcN at the reducing end, by both glycosidic bond cleavage Y1/Z1 and a series of cross-ring fragments. Although no fragment ion was detected to confirm the 6-O-sulfation on the internal GlcN residue, the presence of acetylation on this GlcN indicates C6 is the only place where sulfation can locate according to the knowledge of HS biosynthesis. Similarly, uronic acid can only be sulfated at the 2-O position, and thus the sulfation on non-reducing ΔHexA of [1,1,2,1,5] can be assigned as 2-O-sulfation even without supporting fragments.

The analysis of composition [1,1,2,0,6] is more challenging since there are three sulfate groups per disaccharide and the [M − 4H]4− precursor allows more remaining free protons, leading to higher potential of sulfate losses during fragmentation. However, sulfate loss patterns vary among fragments and the glycosidic bond cleavage fragments without sulfate loss can be observed with a proportion of at least 20% (Figure S5), enabling sequencing of the tetramer as IdoA2S, disulfated GlcN, GlcA and trisulfated GlcN, from non-reducing to reducing end. The internal disulfated GlcN is confirmed as GlcNS6S, using the cross-ring fragments 0,2A2 and 3,5A2 as discussed above.

Two structures were assigned when analyzing composition [1,1,2,0,5], as ΔHexA-GlcNS6S-GlcA-GlcNS3S6S and ΔHexA2S-GlcNS-GlcA-GlcNS3S6S, with the presence of both pentasulfated Z3 and monosulfated B1/C1 (data not shown). We are not able to verify if these two structures are generated from HSPIM natively because the selected precursor may be partially produced from the in-source sulfate loss molecules of the co-eluted [1,1,2,0,6]. An LC system with better separation of HS oligosaccharides, other than SEC, is required and could readily address this problem.

Conclusions

Previous studies on CID and EDD indicated that the complete deprotonation on sulfate groups of precursors is necessary to prevent sulfate loss during fragmentation and to generate fragments for structural characterization [24, 44]. The formation of such completely deprotonated precursors is not feasible for highly sulfated saccharides, a problem that is exacerbated by the comparatively low degree of precursor ion charging observed with LC-MS methods that employ HILIC or SEC. The alternative method is to replace ionizable protons by sodium ions; however, such a strategy multiplies the number of precursor ion forms for a given saccharide, thereby decreasing sensitivity and is not amenable with on-line LC-MS workflows. Such adducts also multiply the difficulty in spectral interpretation. Our observation here that NETD produces sufficient fragments on the commonly-observed deprotonated precursors indicates the high potential for use of LC-MS for rapid sequencing of un-adducted Hep/HS saccharides.

The first successful separation and structural sequencing of HS tetrasaccharides with varying sulfation patterns was previously achieved by RPLC-CID-MS/MS after chemical derivatization [36]. Our results demonstrate that NETD generates extensive, structurally informative fragments on underivatized highly sulfated HS oligosaccharides and is able to assign O-sulfation positions (3-O versus 6-O). Interestingly, the assignments of these structures are largely based on NETD of precursor ions without complete deprotonation. These precursor ions are more easily observed based on current LC methods, compared to complete sodium adducted precursor ions. Additionally, our previous study found the intensities of the deprotonated precursors are greatly increased with an online cation exchange device [39], giving more abundant precursor ions to generate cross-ring fragments. These facts show promise that on-line structural characterization of complex HS oligosaccharides may be achieved by NETD using deprotonated precursors without derivatization or H-Na exchange. Separation of HS mixtures with proper LC columns for online LC-NETD is currently under investigation.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Structures of seven synthetic standards

| Compound | Structure |

|---|---|

| T1 | GlcA-GlcNS-IdoA-GlcNS3S6S |

| T2 | GlcA-GlcNS6S-IdoA-GlcNS3S |

| T3 | GlcA-GlcNS-IdoA2S-GlcNS3S6S |

| T4 | GlcA-GlcNS6S-IdoA-GlcNS3S6S |

| H1 | GlcA-GlcNS6S-IdoA-GlcNS3S-GlcA-GlcNS6S-R* |

| H2 | GlcA-GlcNS6S-IdoA-GlcNS6S-GlcA-GlcNS6S-R |

| H3 | GlcA-GlcNS6S-IdoA-GlcNS3S6S-GlcA-GlcNS6S-R |

R = (CH2)5NH2

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants P41GM104603, R21HL131554, and U01CA221234.

References

- 1.Knelson EH, Nee JC, Blobe GC. Heparan sulfate signaling in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2014;39:277–88. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esko JD, Selleck SB. Order out of chaos: assembly of ligand binding sites in heparan sulfate. Annu Rev Biochem. 2002;71:435–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.71.110601.135458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thacker BE, Seamen E, Lawrence R, Parker MW, Xu Y, Liu J, Vander Kooi CW, Esko JD. Expanding the 3-O-Sulfate Proteome–Enhanced Binding of Neuropilin-1 to 3-O-Sulfated Heparan Sulfate Modulates Its Activity. ACS Chem Biol. 2016;11:971–80. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.5b00897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel VN, Lombaert IM, Cowherd SN, Shworak NW, Xu Y, Liu J, Hoffman MP. Hs3st3-modified heparan sulfate controls KIT+ progenitor expansion by regulating 3-O-sulfotransferases. Dev Cell. 2014;29:662–73. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Esko JD, Lindahl U. Molecular diversity of heparan sulfate. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:169–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI13530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marcum JA, Atha DH, Fritze LM, Nawroth P, Stern D, Rosenberg RD. Cloned bovine aortic endothelial cells synthesize anticoagulantly active heparan sulfate proteoglycan. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:7507–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pejler G, Danielsson A, Bjork I, Lindahl U, Nader HB, Dietrich CP. Structure and antithrombin-binding properties of heparin isolated from the clams Anomalocardia brasiliana and Tivela mactroides. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:11413–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Agostini AI, Dong JC, de Vantery Arrighi C, Ramus MA, Dentand-Quadri I, Thalmann S, Ventura P, Ibecheole V, Monge F, Fischer AM, HajMohammadi S, Shworak NW, Zhang L, Zhang Z, Linhardt RJ. Human follicular fluid heparan sulfate contains abundant 3-O-sulfated chains with anticoagulant activity. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:28115–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805338200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li G, Yang B, Li L, Zhang F, Xue C, Linhardt RJ. Analysis of 3-O-sulfo group-containing heparin tetrasaccharides in heparin by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2014;455:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2014.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li G, Steppich J, Wang Z, Sun Y, Xue C, Linhardt RJ, Li L. Bottom-up low molecular weight heparin analysis using liquid chromatography-Fourier transform mass spectrometry for extensive characterization. Anal Chem. 2014;86:6626–32. doi: 10.1021/ac501301v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, Pedersen LC. Anticoagulant heparan sulfate: structural specificity and biosynthesis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;74:263–72. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0722-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thacker BE, Xu D, Lawrence R, Esko JD. Heparan sulfate 3-O-sulfation: a rare modification in search of a function. Matrix Biol. 2014;35:60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, Shworak NW, Fritze LM, Edelberg JM, Rosenberg RD. Purification of heparan sulfate D-glucosaminyl 3-O-sulfotransferase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27072–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.27072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shukla D, Liu J, Blaiklock P, Shworak NW, Bai X, Esko JD, Cohen GH, Eisenberg RJ, Rosenberg RD, Spear PG. A novel role for 3-O-sulfated heparan sulfate in herpes simplex virus 1 entry. Cell. 1999;99:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tiwari V, O’Donnell CD, Oh MJ, Valyi-Nagy T, Shukla D. A role for 3-O-sulfotransferase isoform-4 in assisting HSV-1 entry and spread. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:930–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu D, Tiwari V, Xia G, Clement C, Shukla D, Liu J. Characterization of heparan sulphate 3-O-sulphotransferase isoform 6 and its role in assisting the entry of herpes simplex virus type 1. Biochem J. 2005;385:451–9. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.O’Donnell CD, Tiwari V, Oh MJ, Shukla D. A role for heparan sulfate 3-O-sulfotransferase isoform 2 in herpes simplex virus type 1 entry and spread. Virology. 2006;346:452–9. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaia J. Glycosaminoglycan glycomics using mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12:885–92. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R112.026294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zaia J. Mass spectrometry of oligosaccharides. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2004;23:161–227. doi: 10.1002/mas.10073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolff JJ, Chi L, Linhardt RJ, Amster IJ. Distinguishing glucuronic from iduronic acid in glycosaminoglycan tetrasaccharides by using electron detachment dissociation. Anal Chem. 2007;79:2015–22. doi: 10.1021/ac061636x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolff JJ, Laremore TN, Busch AM, Linhardt RJ, Amster IJ. Influence of charge state and sodium cationization on the electron detachment dissociation and infrared multiphoton dissociation of glycosaminoglycan oligosaccharides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2008;19:790–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2008.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolff JJ, Laremore TN, Busch AM, Linhardt RJ, Amster IJ. Electron detachment dissociation of dermatan sulfate oligosaccharides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2008;19:294–304. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolff JJ, Leach FE, 3rd, Laremore TN, Kaplan DA, Easterling ML, Linhardt RJ, Amster IJ. Negative electron transfer dissociation of glycosaminoglycans. Anal Chem. 2010;82:3460–6. doi: 10.1021/ac100554a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leach FE, 3rd, Arungundram S, Al-Mafraji K, Venot A, Boons GJ, Amster IJ. Electron Detachment Dissociation of Synthetic Heparan Sulfate Glycosaminoglycan Tetrasaccharides Varying in Degree of Sulfation and Hexuronic Acid Stereochemistry. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2012;330-332:152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leach FE, 3rd, Ly M, Laremore TN, Wolff JJ, Perlow J, Linhardt RJ, Amster IJ. Hexuronic acid stereochemistry determination in chondroitin sulfate glycosaminoglycan oligosaccharides by electron detachment dissociation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23:1488–97. doi: 10.1007/s13361-012-0428-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leach FE, 3rd, Wolff JJ, Xiao Z, Ly M, Laremore TN, Arungundram S, Al-Mafraji K, Venot A, Boons GJ, Linhardt RJ, Amster IJ. Negative electron transfer dissociation Fourier transform mass spectrometry of glycosaminoglycan carbohydrates. Eur J Mass Spectrom (Chichester) 2011;17:167–76. doi: 10.1255/ejms.1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leach FE, 3rd, Xiao Z, Laremore TN, Linhardt RJ, Amster IJ. Electron Detachment Dissociation and Infrared Multiphoton Dissociation of Heparin Tetrasaccharides. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2011;308:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2011.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang Y, Yu X, Mao Y, Costello CE, Zaia J, Lin C. De novo sequencing of heparan sulfate oligosaccharides by electron-activated dissociation. Anal Chem. 2013;85:11979–86. doi: 10.1021/ac402931j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agyekum I, Zong C, Boons GJ, Amster IJ. Single Stage Tandem Mass Spectrometry Assignment of the C-5 Uronic Acid Stereochemistry in Heparan Sulfate Tetrasaccharides using Electron Detachment Dissociation. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s13361-017-1643-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agyekum I, Patel AB, Zong C, Boons GJ, Amster J. Assignment Of Hexuronic Acid Stereochemistry In Synthetic Heparan Sulfate Tetrasaccharides With 2-O-Sulfo Uronic Acids Using Electron Detachment Dissociation. Int J Mass Spectrom. 2015;390:163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.ijms.2015.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oh HB, Leach FE, 3rd, Arungundram S, Al-Mafraji K, Venot A, Boons GJ, Amster IJ. Multivariate analysis of electron detachment dissociation and infrared multiphoton dissociation mass spectra of heparan sulfate tetrasaccharides differing only in hexuronic acid stereochemistry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:582–90. doi: 10.1007/s13361-010-0047-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zaia J, Li XQ, Chan SY, Costello CE. Tandem mass spectrometric strategies for determination of sulfation positions and uronic acid epimerization in chondroitin sulfate oligosaccharides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2003;14:1270–81. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(03)00541-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller MJ, Costello CE, Malmstrom A, Zaia J. A tandem mass spectrometric approach to determination of chondroitin/dermatan sulfate oligosaccharide glycoforms. Glycobiology. 2006;16:502–13. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leach FE, 3rd, Riley NM, Westphall MS, Coon JJ, Amster IJ. Negative Electron Transfer Dissociation Sequencing of Increasingly Sulfated Glycosaminoglycan Oligosaccharides on an Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s13361-017-1709-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chiu Y, Huang R, Orlando R, Sharp JS. GAG-ID: Heparan Sulfate (HS) and Heparin Glycosaminoglycan High-Throughput Identification Software. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2015;14:1720–30. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.045856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang R, Zong C, Venot A, Chiu Y, Zhou D, Boons GJ, Sharp JS. De Novo Sequencing of Complex Mixtures of Heparan Sulfate Oligosaccharides. Anal Chem. 2016;88:5299–307. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang R, Liu J, Sharp JS. An approach for separation and complete structural sequencing of heparin/heparan sulfate-like oligosaccharides. Anal Chem. 2013;85:5787–95. doi: 10.1021/ac400439a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arungundram S, Al-Mafraji K, Asong J, Leach FE, 3rd, Amster IJ, Venot A, Turnbull JE, Boons GJ. Modular synthesis of heparan sulfate oligosaccharides for structure-activity relationship studies. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:17394–405. doi: 10.1021/ja907358k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zaia J, Khatri K, Klein J, Shao C, Sheng Y, Viner R. Complete Molecular Weight Profiling of Low-Molecular Weight Heparins Using Size Exclusion Chromatography-Ion Suppressor-High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2016;88:10654–10660. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huang Y, Mao Y, Zong C, Lin C, Boons GJ, Zaia J. Discovery of a heparan sulfate 3-O-sulfation specific peeling reaction. Anal Chem. 2015;87:592–600. doi: 10.1021/ac503248k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Damerell D, Ceroni A, Maass K, Ranzinger R, Dell A, Haslam SM. The GlycanBuilder and GlycoWorkbench glycoinformatics tools: updates and new developments. Biol Chem. 2012;393:1357–62. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Domon B, Costello CE. A systematic nomenclature for carbohydrate fragmentations in FAB-MS/MS spectra of glycoconjugates. Glycoconjugate Journal. 1988;5:397–409. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huang Y, Shi X, Yu X, Leymarie N, Staples GO, Yin H, Killeen K, Zaia J. Improved liquid chromatography-MS/MS of heparan sulfate oligosaccharides via chip-based pulsed makeup flow. Anal Chem. 2011;83:8222–9. doi: 10.1021/ac201964n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi X, Huang Y, Mao Y, Naimy H, Zaia J. Tandem mass spectrometry of heparan sulfate negative ions: sulfate loss patterns and chemical modification methods for improvement of product ion profiles. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23:1498–511. doi: 10.1007/s13361-012-0429-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zaia J, Costello CE. Tandem mass spectrometry of sulfated heparin-like glycosaminoglycan oligosaccharides. Anal Chem. 2003;75:2445–55. doi: 10.1021/ac0263418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen Y, Lin L, Agyekum I, Zhang X, St Ange K, Yu Y, Zhang F, Liu J, Amster IJ, Linhardt RJ. Structural Analysis of Heparin-Derived 3-O-Sulfated Tetrasaccharides: Antithrombin Binding Site Variants. J Pharm Sci. 2017;106:973–981. doi: 10.1016/j.xphs.2016.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fu L, Li G, Yang B, Onishi A, Li L, Sun P, Zhang F, Linhardt RJ. Structural characterization of pharmaceutical heparins prepared from different animal tissues. J Pharm Sci. 2013;102:1447–57. doi: 10.1002/jps.23501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.