Abstract

Ion mobility measurements of product ions has been used characterize the collisional cross-section (CCS) of various complex lipid [M-H]− ions using traveling wave ion mobility mass spectrometry (TWIMS). TWIMS analysis of various product ion derived after collisional activation of mono-and di-hydroxy arachidonate metabolites was found to be more complex than the analysis of intact molecular ions and provided some insight into molecular mechanisms involved in product ion formation. The CCS observed for the molecular ion [M-H]− and certain product ions were consistent with a folded ion structure, the latter predicted by the proposed mechanisms of product ion formation. Unexpectedly, product ions from [M-H-H2O - CO2]− and [M-H-H2O]− displayed complex ion mobility profiles suggesting multiple mechanisms of ion formation. The [M-H-H2O]− ion from LTB4 was studied in more detail using both nitrogen and helium as the drift gas in the ion mobility cell. One population of [M-H-H2O]− product ions from LTB4 was consistent with formation of covalent ring structures, while the ions displaying a higher CCS were consistent with a more open-chain structure. Using molecular dynamics and theoretical CCS calculations, energy minimized structures of those product ions with the open-chain structures were found to have a higher CCS than a folded molecular ion structure. The measurement of product ion mobility can be an additional and unique signature of eicosanoids measured by LC-MS/MS techniques.

Keywords: ion mobility, eicosanoids, TWIMS, mechanism, product ions, molecular dynamics calculations, CCS calculation, hydroxy, polyunsaturated fatty acids, lipids

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Metabolites of arachidonic acid play significant roles in biology serving as lipid mediators of cellular activation [1]. They perform this action as a result of complex biochemical conversion orchestrated into oxygenated 20-carbon fatty acids catalyzed by prostaglandin H synthase [2], 5-lipoxygenase [3], 15-lipoxygenase, 12-lipoxygenase as well as various isoforms of cytochrome P450 [4,5]. Once synthesized inside the cell at intracellular membrane sites, the eicosanoids are released into the extracellular medium. The unique lipid structures of the various eicosanoid mediators can then be recognized by specific cell-surface protein receptors expressed by cells in the local tissue environment, which are linked to G-protein mediated signalling events within the responding cell. Mass spectrometry has been widely used to qualitatively identify these complex lipids that are made in response to stimulation of the cell that expresses the prostaglandin H synthase or regiospecific lipoxygenases as well as a preferred method to quantitate their production in biological fluids using stable isotope dilution techniques [6].

Analysis of lipids by tandem mass spectrometry after electrospray ionization and reverse phase liquid chromatography has been an extraordinarily powerful means to carry out both specific identification as well quantitation in complex mixtures that are observed in biological extracts [7]. Recently ion mobility has emerged as a powerful means to increase the power of such mass spectrometric techniques that can further drive an increase in sensitivity and specificity in the analysis of lipids with emphasis on phospholipids [8–11]. Various forms of ion mobility including high-field asymmetric wave form ion mobility (FAIMES) [12,13], uniform field drift cell ion mobility [14], as well as traveling wave ion mobility [15] (TWIMS) have become commercially available and are nicely suited for the analysis of fatty acids [16], phospholipids [8,17], neutral lipids [18], and sphingolipids [19] as well as eicosanoids [20].

Most studies of ion mobility-based mass spectrometry of lipids have employed ion mobility of the precursor ion such as [M-H]− of fatty acids and eicosanoids or [M+H]+ of complex lipids such as phospholipids, sphingolipids, and neutral lipids. Recently we have reported an interesting advantage in employing ion mobility measurements of product ions as a means to rapidly identify lipids in complex mixtures [18,21]. We have applied this strategy to the analysis of eicosanoids but found that certain product ions from specific eicosanoids behaved in an unexpected manner with complex ion mobility profiles that suggest populations of alternative structures for these product ions. These observations served as the basis of a study of this phenomenon and molecular calculations of ion structure.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Eicosanoid standards (leukotriene B4, prostaglandin E2, 5-hydroxy-6,8,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid, 8-hydroxy-5,9,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid, 9-hydroxy-5,7,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid, 11-hydroxy-5,8,12,14-eicosatetraenoic acid, 12-hydroxy-5,8,10,14-eicosatetraenoic acid, 15-hydroxy-6,8,11,13-eicosatetraenoic acid), LTB4 and LTA4 methyl ester were purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Solvents and chemicals used for liquid chromatography were HPLC grade, purchased from Fisher Scientific Company (Pittsburgh, PA)

5-Hydroxy-12-[18O] hydroxy-6,8,11,14-Eicosatetraenoic Acid

Isotopically labeled 6-trans LTB4 was prepared by acid catalyzed Michael addition of H218O (Rotem Industries Ltd., Israel, 98 atom % excess) at C-12 of the LTA4 methyl ester prior to saponification of the ester. LTA4 methyl ester (1 μg) in hexanes was dried in a glass test tube under a stream of dry N2 gas. To this was added 40 μL acetone, 10 μL H218O, and 0.5 mg benzoic acid. The mixture was vortexed, and set in a heating block at 37 °C for 30 min. Saponification was carried out with further addition of 40 μL acetone and 10 μL 0.5M NaOH in H2O. The mixture was vortexed, and allowed to set for 25 °C for 60 min. The mixture was dried under a stream of dry nitrogen, followed by addition of 100 μL acetone to extract the organic fraction from residual salts. This was repeated, extracts were combined, dried, and then redissolved in methanol for mass spectrometric analysis.

Mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry and ion mobility measurements obtained were carried out using a Synapt G2-S instrument (Waters, Manchester, UK) in the negative ion mode (tandem quadrupole time of flight mass spectrometer with capability for traveling wave ion mobility separations). Mass spectrometer parameters included: ESI voltage 2500 V, sampling cone 50 V, source offset 80 V, source temperature 120°C, desolvation temperature 150°C, cone gas 10 L/h, desolvation gas 500 L/h, nebulizer 6.0 bar, ion mobility wave height 20 V, and ion mobility wave velocity 220 m/s. Collision induced dissociation was carried out with argon as the collision gas and a collision energy of either 20, 25, or 30 V as indicated. The experiments were carried out in “high resolution” mode.

CCS calculations

The ion mobility times of lipid precursor and product ions were experimentally determined at an ion mobility wave height 20 V, ion mobility wave velocity 220 m/s, and with nitrogen as the ion mobility gas. The centroided ion mobility times were converted into CCS as previously published [22] using polyalanine (20 ng/μL) as a calibrant infused at 20 μL/min. and are expressed in square Angstroms (Å2). In order to determine the reproducibility of the CCS calculations, the ion mobility of LTB4 [M-H]− was separately determined over a six month period. The polyalanine calibration was run at each of these time points, to independently generate a CCS calibration equation. The [M-H]− from LTB4 was found to have an average CCS of 182.6 ± 1.3 Å2 (SD). Additional ion mobility measurements were carried out for LTB4 using helium as drift gas. The usual inlet gas lines to both the helium cell and nitrogen to the IMS cell of the Synapt G2-S were fixed with tee-fittings and shut-off valves so that N2 could be replaced with He in the IMS cell. The usual flow settings, 180 mL/min in the helium cell and 90 mL/min in the IMS cell were maintained and other parameters adjusted as previously published [23].

Molecular Dynamics and Theoretical Collisional Cross Section

Molecular dynamics calculations for each potential ion species were performed using Chimera. Three-dimensional structures for each ion were generated using Marvin 5.9.4 (ChemAxon: (http://www.chemaxon.com) and partial charges were assigned using the semi empirical AM1-BCC force field [1] in UCSF Chimera 1.13 [24]. Structure were energy minimized with 1000 steps of steepest descent minimization followed by 100 steps of conjugate gradient minimization. Each structure was then equilibrated to 298 °K for 10000 steps with velocity rescaling followed by, on average, 3 ns steps of dynamics at 298 °K using a 1 fs time step. All calculations were performed using the MMTK [25] molecular dynamics modules implemented within Chimera [26]. The resulting molecular dynamics trajectories showed that almost all ions tested completely sampled the complete range of structural states available to the ions during the time course of the simulations. The notable exception was the LTB4 [M-H]− which showed significant stabilization of states involving hydrogen-bonds between the C1 carboxylate and the hydroxyl at C5 or C12. For these ions, calculations were repeated multiple times. For each calculation, a series of 20–30 ions were selected to represent the different conformational states present during the simulations. Subsequently, predicted collisional cross sections (CCS) using both nitrogen and helium as carrier gases were calculated using Trajectory methods with a 6-4-12 Lenard-Jones potential using the program IMos version 1.06 (http://www.imospedia.com) [27,28].

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

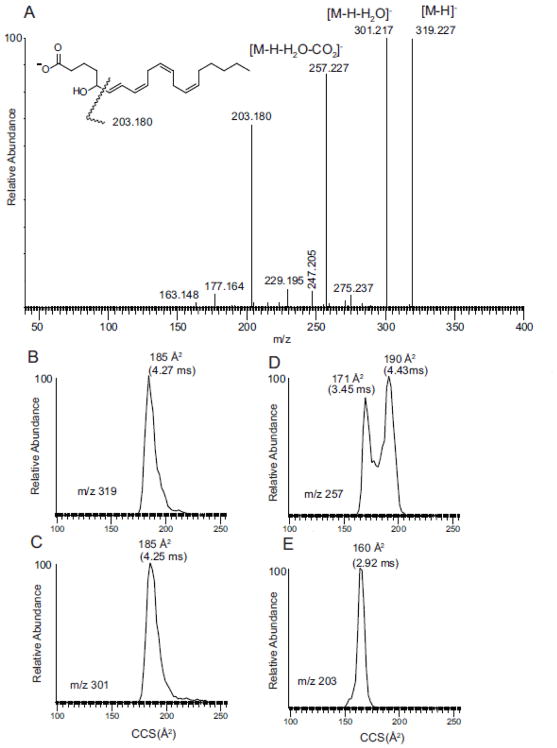

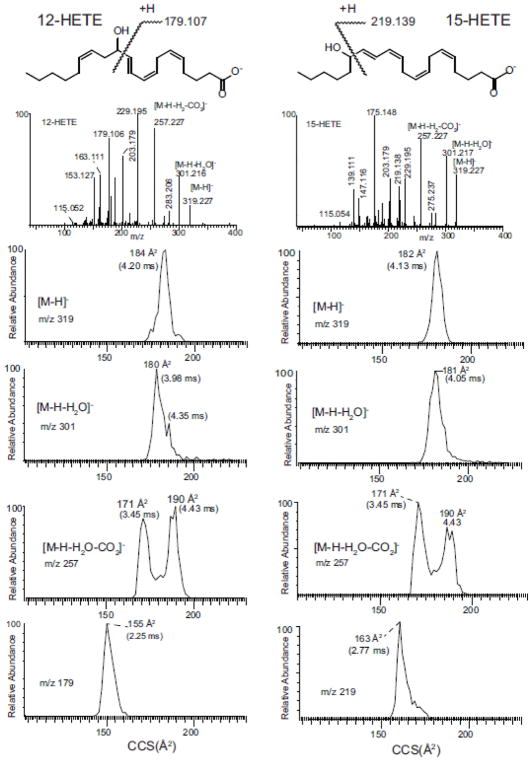

Electrospray ionization of hydroxy, unsaturated fatty acids, including eicosanoids, generates [M-H]− molecular anions that yield abundant product ions after collisional activation [7,29]. These product ions have been studied using various stable isotope labeled analogs to obtain a picture of the mechanisms for major product ion formation. The most abundant product ions arise from carbon-carbon bond cleavage adjacent to a hydroxyl group for the mono hydroxy as well as the dihydroxy eicosanoids [28]. For example the most abundant product of 5-HETE has been suggested to be formal cleavage of the vinyllic bond and the carbinol carbon-carbon bond cleavage to form a hydrocarbon ion at m/z 203.179 (C15H23)− (Figure 1A). More likely these cleavage reactions involve either a charge-driven or charge-remote allylic fragmentation processes after a 1[5]-sigmatropic proton shift of the 6,7 double bond and the proton at carbon-13. A charge driven mechanism has been proposed following the carboxyl anion abstracting a proton from the carbon-5 hydroxyl group leading to a charge driven cleavage of the allylic bond [7]. Thus, inherent in such a mechanism would be folding of the molecule onto itself in order to bring various structural moieties sufficiently close for such unimolecular reactions to occur.

Figure 1.

(A) Tandem mass spectrum of 5-HETE. (B) Ion mobility of m/z 319.227 [M-H]−. (C) Ion mobility of m/z 301.217 [M-H-H2O]−. (D). Ion mobility of m/z 257.227 [M-H-H2O-CO2]−. (E) Ion mobility of m/z 203.180. See inset structure for origin of m/z 203.180.

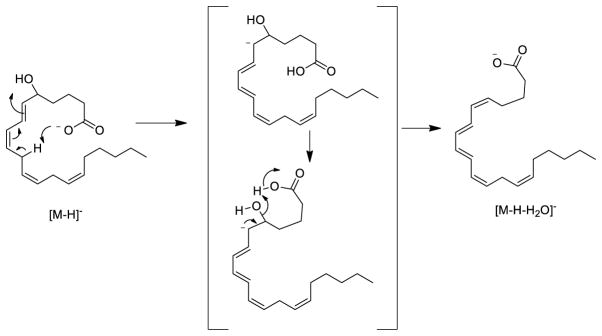

Ion mobility profiles derived from 5-HETE [M-H]− and selected product ions m/z 301, 257, and 203 were not all single populations (Figure 1 B to E). The ion mobility of the product ion at m/z 203 was, as expected, fairly short with a collisional cross-section calculated to be 165 Å2 from a drift time of 2.92 ms whereas the [M-H]− ion was 185 Å2 (Figure 1E and B, respectively). Interestingly there appeared to be at least two populations of ions from the ion mobility profiles of the ion m/z 257 [M-H-H2O and CO2]− (Figure 1D). These two quite distinct population of ions had calculated cross-sections 171 and 190 Å2 respectively. The population of ions of longest drift time had even higher collisional cross-sections than the starting precursor ions [M-H]− ion at m/z 319 (185 Å2) even though it was 62 Da lower in mass. The two distinct populations of m/z 257 suggested two isomeric structures for m/z 257 might emanate from the collisional activation of the [M-H]−. The loss of water would appear, at first glance, to be a somewhat trivial loss of a small neutral species, but a charge-driven mechanism could bring a carbon-10 proton close to the carboxylate anion followed by formation of a Δ5- double bond followed by the loss of H2O and regeneration of the stabilized carboxylate anion. This loss of a neutral water molecule would then from a conjugated tetraene [M-H-H2O]− (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1.

Neutral CO2 could follow from the intermediate formation of the loss of water, possibly in a concerted manner from the dehydrated structure, to form either a cyclic structure or an open-chain, highly conjugated structure (Scheme 2). These two structures would likely have quite distinct ion mobilities. The open-chain form of m/z 257 would be expected to have a high collisional cross-section (190 Å2) since the extended conjugated system would be expected to be rather open-chain while the cyclic form of m/z 257 would have the lower collisional cross-section of 171 Å2, following the observed trend of folded structures being more highly mobile than unfolded structures [30].

Scheme 2.

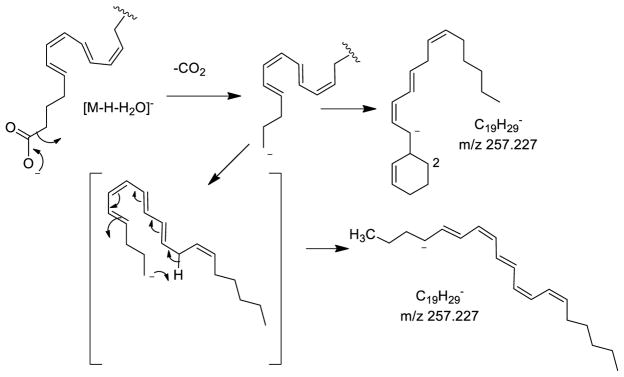

This general trend of two populations of drift times was observed for other hydroxy, polyunsaturated eicosanoids including 12-HETE and 15-HETE (Figure 2) as well as 8-HETE (Supplemental Figure S1), 9-HETE (Supplemental Figure S2), 11-HETE (Supplemental Figure S3), 20-HETE (Supplemental Figure S4) for the loss of CO2 and H2O. A single population of ions was observed for [M-H]− and [M-H2O]− and the cleavage ion adjacent to the hydroxyl group at m/z 179 and 219 for 12-HETE and 15-HETE, respectively. Even though the loss of CO2 and H2O was not very abundant for 11-HETE (Supplemental Figure S3), there was some indication of this trend for two populations of ion mobilities for these ions. This unexpected ion mobility behavior of ions following sequential loss of H2O and CO2 for most hydroxy polyunsaturated eicosanoids, supported the idea of multiple mechanisms for product ion formation as well as highly folded structures for the precursor ion formed initially by electrospray ionization.

Figure 2.

Ion mobility of 12-HETE and 15-HETE for indicated ions [M-H]−, [M-H-H2O]−. [M-H- H2O-CO2]−, and structurally diagnostic allylic cleavage ions for each eicosanoid. See inset structures for origin of m/z 179.2 from 12-HETE and m/z 219.1 from 15-HETE.

The five hydroxy eicosanoids studied were remarkable in consistency of behavior following collision collisional activation and measurement of collisional cross-section of product ions corresponding to the loss of water and water plus CO2 (Table 1). In spite of the positions of the hydroxyl substituents from carbon-5 to carbon-15, the collisional cross sections for m/z 317 and 257 were very similar. This would suggest that interaction of the carboxylate anion with double bonds along the eicosanoid chain, which drives loss of water and forms a stabilized conjugated double bond structure (Scheme 1), occurs relatively easily. Furthermore the subsequent reactions following loss of CO2, results in similar ion structures irrespective of the initial double bond position. This supports a facility in formation of two isomeric structures for the ion at m/z 257, yet each isomer being quite similar for these hydroxy eicosanoids.

Table 1.

Hydroxy, polyunsaturated fatty acid anions collisionally activated to selected product ions. The measured exact masses, drift times, and collisional cross section (CCS) reported in Å2.

| Eicosanoid | [M-H]− Measured1 | Drift time (ms) | CCS (N2) | CCS (He) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HETE | 319.227 | 4.27 | 185 | |

| [M-H2O]− | 301.217 | 4.25 | 185 | |

| [M-H2O-CO2]− | 257.227 | 3.45 | 171 | |

| [M-H2O-CO2]− | 257.227 | 4.43 | 190 | |

| 8-HETE | 319.227 | 4.12 | 182 | |

| [M-H2O]− | 301.216 | 3.97 | 180 | |

| [M-H2O-CO2]− | 257.227 | 3.45 | 171 | |

| [M-H2O-CO2]− | 257.227 | 4.27 | 187 | |

| 11-HETE | 319.227 | 4.12 | 182 | |

| [M-H2O]− | 301.216 | 3.97 | 180 | |

| [M-H2O-CO2]− | 257.227 | 3.45 | 171 | |

| [M-H2O-CO2]− | 257.227 | 4.27 | 187 | |

| 12-HETE | 319.227 | 4.20 | 184 | |

| [M-H2O]− | 301.216 | 3.98 | 180 | |

| [M-H2O-CO2]− | 257.226 | 3.45 | 171 | |

| [M-H2O-CO2]− | 257.226 | 4.43 | 190 | |

| 15-HETE | 319.227 | 4.13 | 182 | |

| [M-H2O]− | 301.216 | 4.05 | 181 | |

| [M-H2O-CO2]− | 257.227 | 3.45 | 171 | |

| [M-H2O-CO2]− | 257.227 | 4.43 | 190 | |

| LTB41,2 | 335.222 | 4.28 | 1833 | 118 |

| [M-H2O]− | 317.212 | 4.28 | 185 | 118 |

| [M-H2O]− | 317.212 | 5.33 | 205 | 134 |

| [M-H2O-CO2]− | 273.222 | 3.90 | 179 | 108 |

| [M-H2O-CO2]− | 273.222 | 4.73 | 195 | 124 |

| m/z 203.1795 | 203.180 | 2.70 | 158 | 95 |

| m/z 195.0974 | 195.102 | 2.33 | 151 | 88 |

Exact masses reported using the molecular anion exact mass as the lockmass.

CID collision energy 30 V (laboratory frame of reference).

Five independent measurements were carried over a six month period with an average value of 182.6 ± 1.3 Å2 (SD).

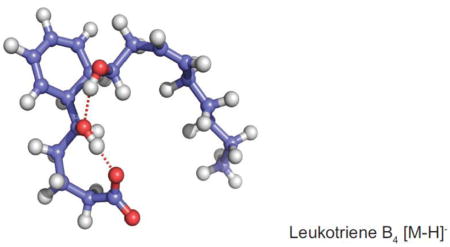

LTB4

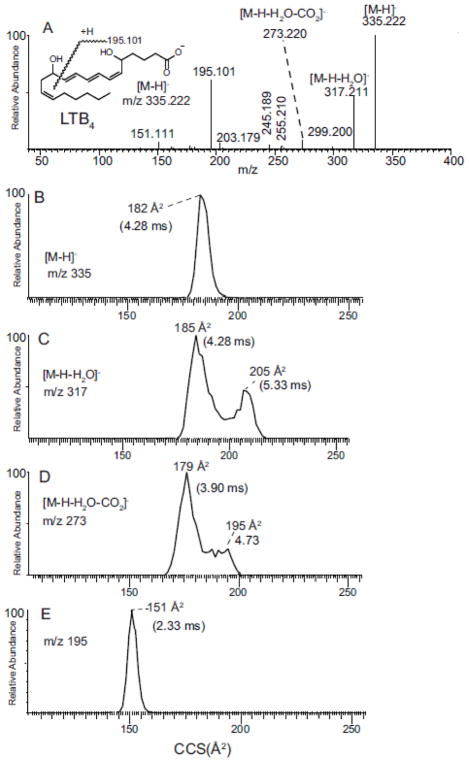

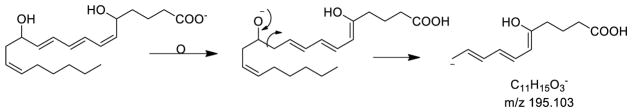

The collision activation of the [M-H]− from LTB4 at m/z 335 yielded a large number a product ions, with the most abundant being m/z 195 as previously reported ( Figure 3A). The proposed mechanism of formation of this ion has been suggested to involve a Diels-Alder reaction with formation of a cyclic ion structure (see below) and an alkoxide anion at carbon-12 likely from a remote charge exchange with the carboxylate anion (Scheme 3) [7,31]. This mechanism would be dependent on intramolecular folding of LTB4 back onto itself during the process of formation of this characteristic ion.

Figure 3.

(A) Tandem mass spectrum of LTB4 with 20 V applied in the collision cell. (B) Ion mobility of m/z 335.222 [M-H]−. (C) Ion mobility of m/z 317.221 [M-H-H2O]−. (D). Ion mobility of m/z 273.220 [M-H-H2O-CO2]−. (E) Ion mobility of diagnostic ion m/z 195.1. See inset structure for origin of m/z 195.1. The collision energy used for this mass spectrum was 20 V.

Scheme 3.

The loss of H2O from LTB4 could come from 3 different sites: loss of a carbon-12 hydroxyl group, carbon-5 hydroxyl group, or a carboxyl oxygen atom plus two protons. In order to investigate which group was lost predominantly, the 12-hydroxyl group of LTB4 was labeled with oxygen-18 by opening the epoxide ring of LTA4 methyl ester with H218 O. After saponification and purification of the resulting 5-hydroxy-12-[18 O] hydroxyl-6, 8, 10, 14-eicosatetraenoic acid, the collisional activation of m/z 337 revealed that the loss of H2O was predominantly loss of H218 O from carbon-12 with the major ions appearing at m/z 317 and 273 consistent with the lack of oxygen-18 in these product ions (Supplemental Figure S5). As expected from the mechanism of formation (see above), the most abundant product ion m/z 195 also did not retain oxygen-18.

The ion mobility profiles of [M-H]− (Figure 3B) and m/z 195 (Figure 3D) were found to be single populations of drift times at 185 Å2 and 151 Å2, respectively, but the ions corresponding to the loss of H2O from the [M-H]− at m/z 317 and loss of CO2 and H2O at m/z 273 revealed that the mechanisms leading to the formation of these dehydration product ion resulted in two, quite separate ion mobilities (Table 1). This dual population of ion mobility for m/z 273 was more pronounced when the collisional energy in the collision cell was increased from 20 to 30 volts, suggesting the higher mobility ion was formed when the energy available for collisional activation was higher (Supplemental Figure S6). Furthermore the drift time at 4.73 ms for one population of ions at m/z 273 was longer than that for the precursor molecular anion [M-H]− observed at 4.28 ms. This was also the case for the ion mobilities of m/z 317 where the population of ions with the longest average ion mobility (5.33 ms) had a collisional cross section of 205 Å2.

The loss of water from the molecular ion of LTB4 has been suggested to involve a prior Diels-Alder cyclization [17,31] to form a cyclic intermediate of LTB4 (Scheme 4) which facilitates the loss of H2O from carbon-12. Such an intermediate can rearrange into either a open-chain conjugated ion structure (pathway a) or another cyclic ion (pathway b). This product ion from pathway a (Structure 1) would be predicted to have a much higher collisional cross section than the folded ion Structure 2 for m/z 317 [M-H2O]−. These pathways are consistent with the loss of H2O from isotope labeled LTB4 isomers studied here [5-hydroxy-12-[18O] hydroxy-6,8,11,14-eicosatetraenoic acid] and published ([6,7,13,14-D4]-LTB4) [31].

Scheme 4.

Molecular Dynamics and Collision Cross Section Calculations

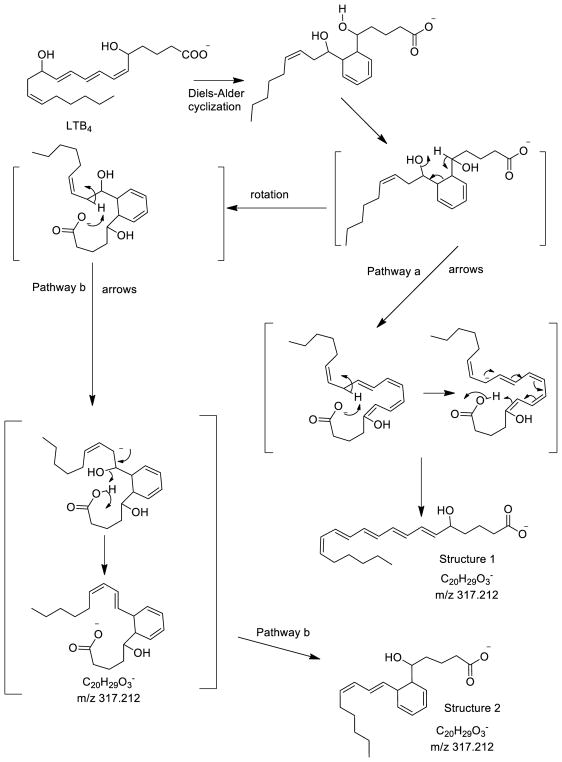

Ion mobility studies of biopolymers and polymers has led to the suggestion that a more folded or more compact ion 3-dimentional structure would have shorter drift times (lower collisional cross-section) than an open structure [32,33]. Molecular dynamics calculations were carried out starting as the typically drawn structure of LTB4 in order to generate an energy minimized 3-dimentional structure. However the calculations of the ion mobilities were not in agreement with the measured values of collisional cross section (Table 1). Calculations of ion mobility was then carried our on the cyclized structure of LTB4 after a Diels-Alder reaction of the conjugated triene. This is the intermediate proposed several years ago and presented in Scheme 4. Two distinct populations of structures were found in the molecular dynamics calculations and they were a folded methyl terminus of LTB4 next to the cyclohexadiene ring (Figure 4A) which predicted populations of structures that engaged a complex hydrogen bond bridge between the carboxylate anion and the 5-hydroxy proton as well as 12-hydroxy proton (Figure 4A). This folded structure of cyclized LTB4 were calculated to have a CCS a 185 Å2 in nitrogen and a CCS 116 Å2 in helium, quite consistent with the observed CCS 185 Å2 (N2) and 118 Å2 (He) (Table 1). The open structure (Figure 4B) had calculated ion mobilities in N2 and He that were not in agreement with the measured values. We would therefore suggest that the intact LTB4 molecular ions entering the ion mobility cell had likely undergone rearrangement prior to measuring the ion mobility.

Figure 4.

Molecular dynamics calculated stable structures of LTB4 showing a hydrogen bond between the carboxylate anion (A) with the 5-hydroxyl proton and (B) with the 12-hydroxyl proton. The ion mobilities of these structures were calculated by Imos for nitrogen and helium as drift gas.

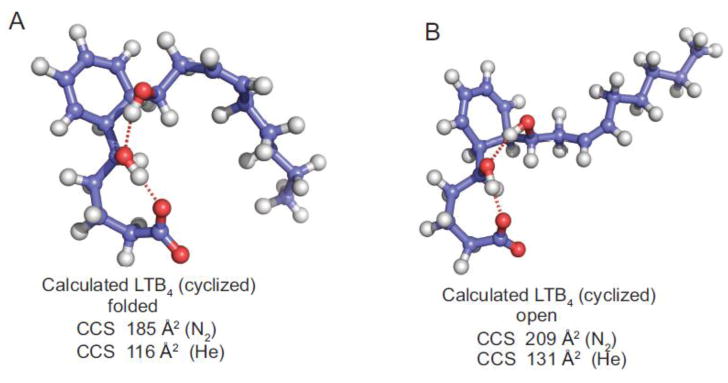

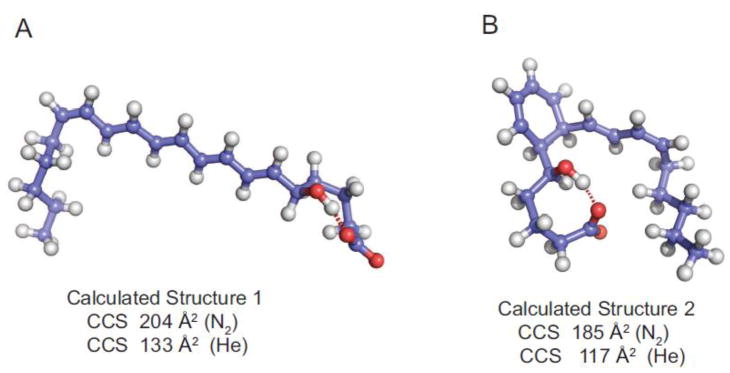

The collisional cross-section for the major LTB4 product ions were also measured in both N2 and He drift gases. Molecular dynamics calculations were carried out on the predicted covalent structures for [M-H-H2O]− in Scheme 4 and a number of energy minimized three-dimensional structures were found to be highly stable over the calculation period. The vast majority of the predicted structures fit into two different categories, the product ion formed by Pathway a, Structure 1, (Scheme 4) that retained extended conjugation, which had a molecular dynamics calculated structure shown in figure 5A. This open-chain structure was calculated to have a CCS of 204 Å2 (N2) and 133 Å2 (He), very close to one of the observed populations of [M-H2O]− (Table 1). For the product ion m/z 317 formed by Pathway b, Structure 2, (Scheme 4), a rather folded structure due to a stabilizing hydrogen bond between the carboxylate anion and the carbon-5 hydroxy proton (Figure 5B). The structure for this [M-H-H2O]− variant was calculated to have a CCS of 185 Å2 in N2 and 117 Å2 in He drift gas.

Figure 5.

Molecular dynamics calculated stable structures for the ion corresponding to [M-H-H2O]− from LTB4 as (A) the highly conjugated, open-chain structure predicted in Scheme 4 Pathway a showing a hydrogen bond between the carboxylate anion and the 5-hydroxy proton. (B) the cyclic structure predicted in Scheme 4 Pathway b showing a hydrogen bond between the carboxylate anion with the hydroxyl proton at carbon-5. The ion mobilities of these structures were calculated using IMos version 1.06 for nitrogen and helium as drift gas.

Conclusions

Ion mobility measurements of product ions derived from hydroxy, polyunsaturated fatty acids (anions) can display multi-component populations of mobilities for isobaric ions. Suggested mechanisms for product ion formation of such lipids often invoke interactions of structural moieties that induce a folded confirmation. These observations and calculations of ion mobilities support the existence of distinct structural isomers formed during the collisional activation process that bring together remote sites that facilitate subsequent decomposition reactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (ES022172) and a grant from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (HL117798). The authors wish to acknowledge and thank Dr. Carlos Larriba-Andaluz (Indiana University) for advice and providing updated parameters for IMos 1.06.

References

- 1.Smith WL, Murphy RC. The Eicosanoids: Cyclooxygenase, lipoxygenase, and epoxygenase pathways. In: Ridgeway ND, McLeod RS, editors. Biochemistry of Lipids, Lipoproteins and Membranes. 6. Elsevier Science; Oxford, UK: 2015. pp. 260–295. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith WL. Nutritionally essential fatty acids and biologically indispensable cyclooxygenases. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy RC, Gijón MA. Biosynthesis and metabolism of leukotrienes. Biochem J. 2007;405:379–395. doi: 10.1042/BJ20070289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuhn H, Banthiya S, van Leyen K. Mammalian lipoxygenases and their biological relevance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1851:308–330. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spector AA. Arachidonic acid cytochrome P450 epoxygenase pathway. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:S52–56. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R800038-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsikas D, Zoerner AA. Analysis of eicosanoids by LC-MS/MS and GC-MS/MS: a historical retrospect and a discussion. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2014;964:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2014.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy RC. Tandem Mass Spectrometry of Lipids: Molecular Analysis of Complex Lipids. Ch. 2. Royal Society of Chemistry; London, UK: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim HI, Kim H, Pang ES, Ryu EK, Beegle LW, Loo JA, Goddard WA, Kanik I. Structural characterization of unsaturated phosphatidylcholines using traveling wave ion mobility spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81:8289–8297. doi: 10.1021/ac900672a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jackson SN, Wang HY, Woods AS, Ugarov M, Egan T, Schultz JA. Direct tissue analysis of phospholipids in rat brain using MALDI-TOFMS and MALDI-ion mobility-TOFMS. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005;16:133–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Groessl M, Graf S, Knochenmuss R. High resolution ion mobility-mass spectrometry for separation and identification of isomeric lipids. Analyst. 2015;140:6904–6911. doi: 10.1039/c5an00838g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maccarone AT, Duldig J, Mitchell TW, Blanksby SJ, Duchoslav E, Campbell JL. Characterization of acyl chain position in unsaturated phosphatidylcholines using differential mobility-mass spectrometry. J Lipid Res. 2014;55:1668–1677. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M046995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowman AP, Abzalimov RR, Shvartsburg AA. Broad Separation of Isomeric Lipids by High-Resolution Differential Ion Mobility Spectrometry with Tandem Mass Spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2017;28:1552–1561. doi: 10.1007/s13361-017-1675-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lintonen TP, Baker PR, Suoniemi M, Ubhi BK, Koistinen KM, Duchoslav E, Campbell JL, Ekroos K. Differential mobility spectrometry-driven shotgun lipidomics. Anal Chem. 2014;86:9662–9669. doi: 10.1021/ac5021744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.May JC, Goodwin CR, Lareau NM, Leaptrot KL, Morris CB, Kurulugama RT, Mordehai A, Klein C, Barry W, Darland E, Overney G, Imatani K, Stafford GC, Fjeldsted JC, McLean JA. Conformational ordering of biomolecules in the gas phase: nitrogen collision cross sections measured on a prototype high resolution drift tube ion mobility-mass spectrometer. Anal Chem. 2014;86:2107–2016. doi: 10.1021/ac4038448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giles K, Pringle SD, Worthington KR, Little D, Wildgoose JL, Bateman RH. Applications of a travelling wave-based radio-frequency-only stacked ring ion guide. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2004;18:2401–2414. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang F, Guo S, Zhang M, Zhang Z, Guo Y. Characterizing ion mobility and collision cross section of fatty acids using electrospray ion mobility mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2015;50:906–913. doi: 10.1002/jms.3600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castro-Perez J, Roddy TP, Nibbering NM, Shah V, McLaren DG, Previs S, Attygalle AB, Herath K, Chen Z, Wang SP, Mitnaul L, Hubbard BK, Vreeken RJ, Johns DG, Hankemeier T. Localization of fatty acyl and double bond positions in phosphatidylcholines using a dual stage CID fragmentation coupled with ion mobility mass spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2011;22:1552–1567. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0172-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hankin JA, Barkley RM, Zemski-Berry K, Deng Y, Murphy RC. Mass Spectrometric Collisional Activation and Product Ion Mobility of Human Serum Neutral Lipid Extracts. Anal Chem. 2016;88:6274–6282. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sarbu M, Vukelić Ž, Clemmer DE, Zamfir AD. Electrospray ionization ion mobility mass spectrometry provides novel insights into the pattern and activity of fetal hippocampus gangliosides. Biochimie. 2017;139:81–94. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kapron J, Wu J, Mauriala T, Clark P, Purves RW, Bateman KP. Simultaneous analysis of prostanoids using liquid chromatography/high-field asymmetric waveform ion mobility spectrometry/tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2006;20:1504–1510. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berry KA, Barkley RM, Berry JJ, Hankin JA, Hoyes E, Brown JM, Murphy RC. Tandem Mass Spectrometry in Combination with Product Ion Mobility for the Identification of Phospholipids. Anal Chem. 2017;89:916–921. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b04047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paglia G, Angel P, Williams JP, Richardson K, Olivos HJ, Thompson JW, Menikarachchi L, Lai S, Walsh C, Moseley A, Plumb RS, Grant DF, Palsson BO, Langridge J, Geromanos S, Astarita G. Anal Chem. 2015;87:1137–1144. doi: 10.1021/ac503715v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lalli PM, Corilo YE, Fasciotti M, Riccio MF, de Sa GF, Daroda RJ, Souza GH, McCullagh M, Bartberger MD, Eberlin MN, Campuzano ID. Baseline resolution of isomers by traveling wave ion mobility mass spectrometry: investigating the effects of polarizable drift gases and ionic charge distribution. J Mass Spectrom. 2013;48:989–997. doi: 10.1002/jms.3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakalian A, Jack DB, Bayly CI. Fast, efficient generation of high-quality atomic charges. AM1-BCC model: II Parameterization and validation. J Comput Chem. 2002;23:1623–1641. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera--a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hinsen K. The molecular modeling toolkit: A new approach to molecular simulations. J Comput Chem. 2000;21:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larriba C, Hogan CJ. Free molecular collision cross section calculation methods for nanoparticles and complex ions with energy accommodation. J Comput Phys. 2013;251:344–363. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larriba-Andaluz C, Hogan CJ., Jr Collision cross section calculations for polyatomic ions considering rotating diatomic/linear gas molecules. J Chem Phys, X. 2013;141:194107. doi: 10.1063/1.4901890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wheelan P, Zirrolli JA, Murphy RC. Low-energy fast atom bombardment tandem mass spectrometry of monohydroxy substituted unsaturated fatty acids. Biol Mass Spectrom. 1993;22:465–473. doi: 10.1002/bms.1200220808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duez Q, Josse T, Lemaur V, Chirot F, Choi CM, Dubois P, Dugourd P, Cornil J, Gerbaux P, De Winter J. Correlation between the shape of the ion mobility signals and the stepwise folding process of polylactide ions. J Mass Spectrom. 2017;52:133–138. doi: 10.1002/jms.3915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wheelan P, Zirrolli JA, Murphy RC. Negative ion electrospray tandem mass spectrometric structural characterization of leukotriene B4 (LTB4) and LTB4-derived metabolites. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 1996;7:129–139. doi: 10.1016/1044-0305(95)00629-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shvartsburg AA, Hudgins RR, Dugourd P, Jarrold MF. Structural elucidation of fullerene dimers by high-resolution ion mobility measurements and trajectory calculation simulations. J Phys Chem A. 1997;101:1684–1688. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vonhelden G, Wyttenbach T, Bowers MT. Inclusion of a MALDI ion source in the ion chromatography technique: conformational information on polymer and biomolecular ions. Int J Mass Spectrom. 1995;146:349–364. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.