Significance

Conventionally, vaccines are screened for induction of a neutralizing antibody response in human volunteers before proceeding to late-stage clinical trials. We present results from a human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) challenge study suggesting that this paradigm may not apply universally to all viruses. Instead, viruses like HCMV, which establish lifelong infections and grow both cell-free and cell-associated, may be controlled independently of a potent neutralizing antibody response. Our results suggest that more detailed laboratory studies are required to identify correlates of immune protection for such viruses and that failure of a vaccine to induce a neutralizing antibody response should not necessarily be considered as a key go-no-go decision point in the design of future vaccine studies.

Keywords: cytomegalovirus, vaccine, humoral immunity

Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) is an important pathogen in transplant patients and in congenital infection. Previously, we demonstrated that vaccination with a recombinant viral glycoprotein B (gB)/MF59 adjuvant formulation before solid organ transplant reduced viral load parameters post transplant. Reduced posttransplant viremia was directly correlated with antibody titers against gB consistent with a humoral response against gB being important. Here we show that sera from the vaccinated seronegative patients displayed little evidence of a neutralizing antibody response against cell-free HCMV in vitro. Additionally, sera from seronegative vaccine recipients had minimal effect on the replication of a strain of HCMV engineered to be cell-associated in a viral spread assay. Furthermore, although natural infection can induce antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) responses, serological analysis of seronegative vaccinees again presented no evidence of a substantial ADCC-promoting antibody response being generated de novo. Finally, analyses for responses against major antigenic domains of gB following vaccination were variable, and their pattern was distinct compared with natural infection. Taken together, these data argue that the protective effect elicited by the gB vaccine is via a mechanism of action in seronegative vaccinees that cannot be explained by neutralization or the induction of ADCC. More generally, these data, which are derived from a human challenge model that demonstrated that the gB vaccine is protective, highlight the need for more sophisticated analyses of new HCMV vaccines over and above the quantification of an ability to induce potent neutralizing antibody responses in vitro.

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) causes substantial morbidity in multiple patient populations with impaired or immature immune responses (1, 2). The threat posed during organ transplantation or congenital infection led to HCMV vaccine development being categorized as the highest priority (3). Several vaccines against HCMV (from whole virus, DNA, and viral subunits) have been studied in different patient cohorts establishing, in general, that a vaccination strategy targeted against HCMV is a viable option with major clinical implications (4–10).

One vaccine target is the viral glycoprotein B (gB), which has been shown to be partially protective in three phase 2 clinical trials when presented with MF59 adjuvant (6, 9, 11). The gB protein is an essential virion component required for viral entry (12, 13) and represents a major target of the humoral immune response, including neutralization (14–16). Conventionally, neutralizing antibody titers have been considered the benchmark by which vaccines are assessed as this represents a potent antiviral mechanism. However, the humoral response is far more complex producing antibodies that can bind both pathogens or the target antigen when expressed on the surface of the infected cell to elicit multiple downstream effects. These antibodies can recruit complement to promote lysis of the pathogen or the infected cell, drive antibody dependent cell cytotoxicity, promote phagocytosis of the pathogen as well as modulate the downstream response of both the adaptive and innate immune responses (17). Here we report data showing limited evidence of a neutralizing antibody response as a correlate of protection for the gB vaccine in a phase 2 study where transplant patients were challenged with wild-type HCMV (9). An inability to detect evidence of neutralization of clinical Merlin was consistent with previous data demonstrating no effect of antibody plus complement against the laboratory strain Towne in a classical plaque assay (9). Furthermore, we provide evidence that the humoral response against gB induced in seronegatives by vaccination displays a distinct biological spectrum compared with that observed in naturally infected seropositives.

Results

Sera from Seronegative Vaccinated Patients Do Not Neutralize HCMV Infection in Single-Round Infection Assays.

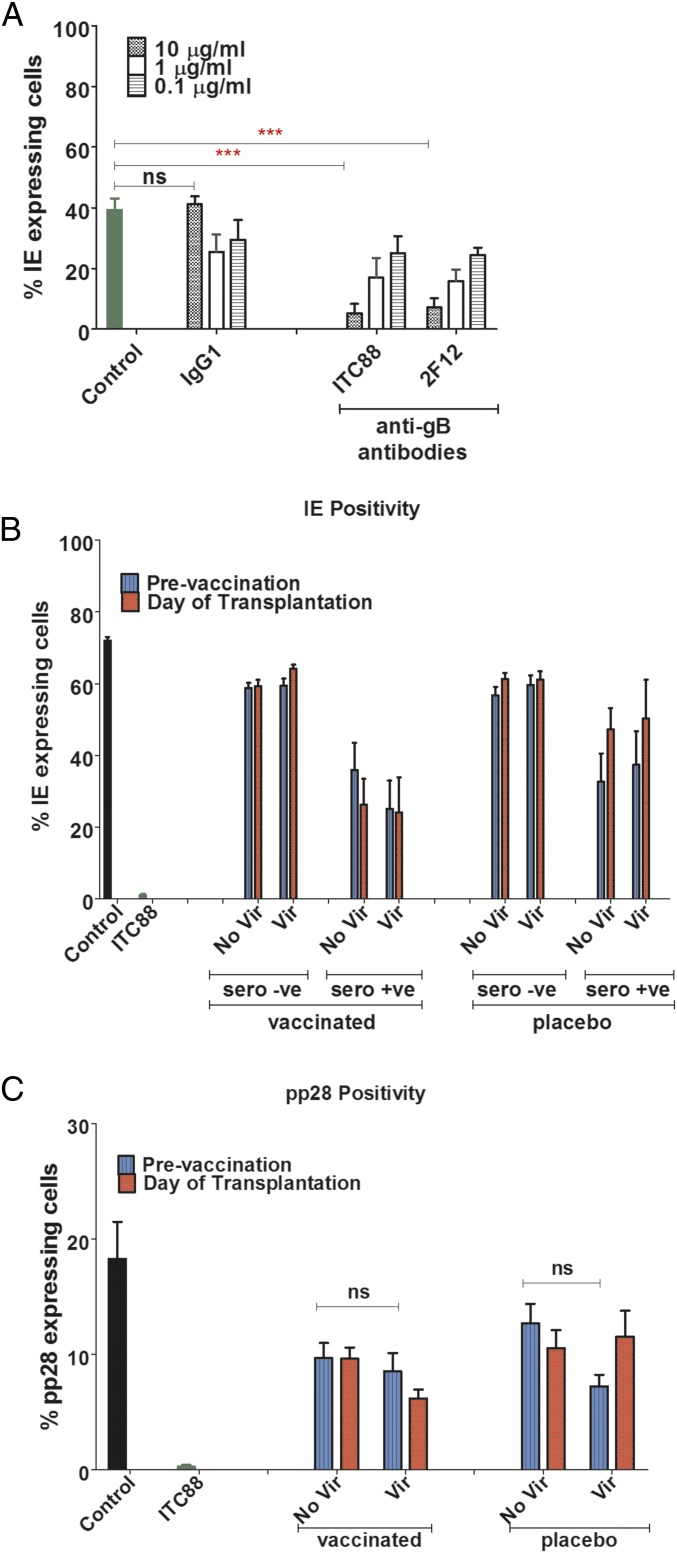

Note that throughout this paper the term “seronegative” refers to patients who were seronegative before being given gB/MF59 vaccine or placebo. We tested for evidence of neutralization of HCMV infection using a high-throughput assay that measured the establishment of a lytic infection by enumeration of immediate–early (IE) positive cells (Fig. 1). Two anti-gB monoclonal antibodies (ITC88, an anti–AD-2 antibody demonstrated to prevent gB fusion post binding [18]; and 2F12, a commercial monoclonal antibody against an unspecified region of gB) inhibited HCMV infection in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). Next we tested a panel of sera from our vaccine study under the same conditions. Before vaccination, sera from seronegative individuals had no impact on HCMV infection. Importantly, no evidence of activity against HCMV was observed in this assay when seronegative sera post vaccination were assessed (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1 A–D) even when exogenous complement was added to the sera before infection (Fig. S2). In contrast, sera from seropositive patients had inherent neutralizing activity against HCMV before transplantation (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1 E–H), but no evidence of increased neutralizing capacity was observed post vaccination (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1 E–H).

Fig. 1.

Vaccination does not promote neutralizing antibody responses in seronegatives. (A) HCMV was incubated for 1 h with different concentrations of monoclonal antibodies against gB (ITC88 and 2F12), IgG1 isotype control, or media and then used to infect HFFs (MOI = 0.5). Percentage of IE positivity was scored 24 hpi. n = 3. (B) HCMV was incubated for 1 h with sera from seropositive or seronegative patients either vaccinated with gB or given a placebo and then used to infect HFFs (MOI = 1). The analysis was performed on sera isolated prevaccination and at day of transplant (post vaccination). Percentage IE positivity was scored 24 hpi and further stratified into patients who developed viremia. n = 3. (C) HCMV was incubated for 1 h with sera from seronegative patients either vaccinated with gB or given placebo and then used to infect HFFs (MOI = 1). The analysis was performed on sera isolated prevaccination and at day of transplant (post vaccination). Percentage of pp28 positivity was scored 120 hpi and further stratified into patients who developed viremia. n = 3.

To address the possibility that the sera from seronegative vaccinees contained antibodies capable of inducing abortive/quiescent infections, as proposed for varicella infection (19), a parallel analysis was performed that measured pp28 (a viral late gene) positivity (Fig. 1C). Unsurprisingly, pp28-positive cells were rare in the ITC88 control (Fig. 1C), given that IE-positive cells were rarely seen (Fig. 1B). In contrast, and consistent with the IE data, no effect on pp28 positivity was observed using the sera from vaccinated seronegative transplant recipients (Fig. 1C and Fig. S3).

Sera from Vaccinated Seronegative Patients Do Not Inhibit Spread of Cell-Associated Merlin Strain of HCMV in Fibroblast Monolayers.

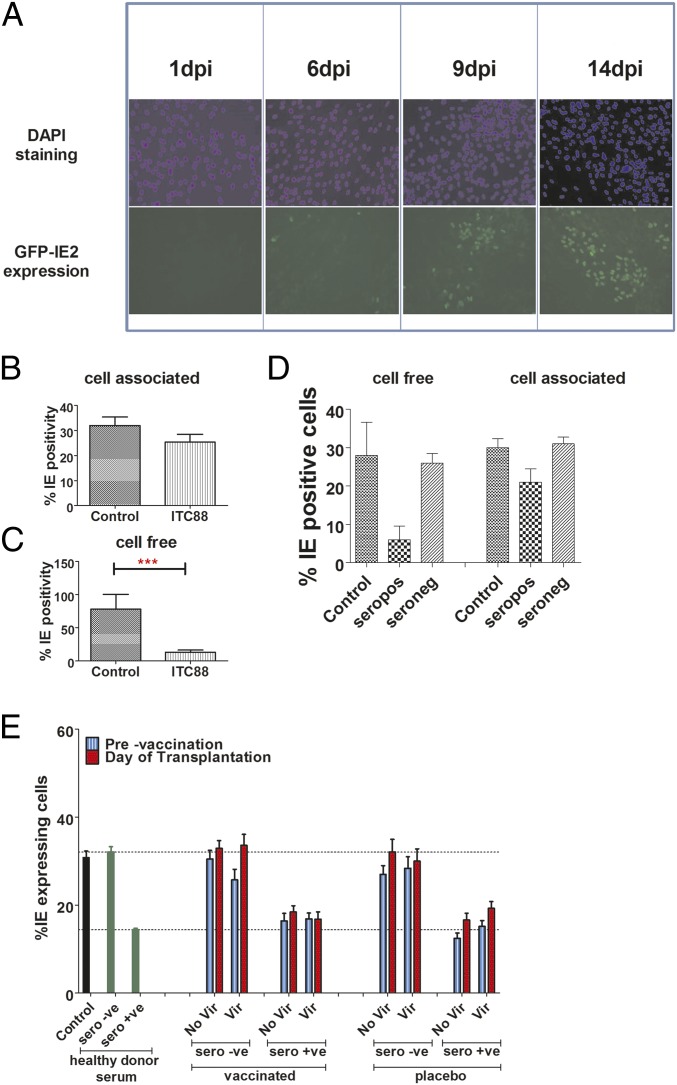

Our first assays measured the ability of sera to limit infection of cells with large titers of cell-free virus by measuring the number of IE-positive cells 24 hours post inoculation (hpi). To investigate whether sera had antiviral activity against cell-associated HCMV, we assessed their impact on the growth of HCMV in fibroblast cultures using a viral-spreading assay seeded at low multiplicity of infection (MOI). To be able to ask this question, we utilized a Merlin-IE2-GFP virus engineered to grow predominantly in a cell-associated fashion (20). The expression of GFP with IE2 kinetics allows real-time imaging and enumeration of the spread of the virus as we visualize in real time the increase in the number of infected cells over time and thus monitor the spread of the virus through the fibroblast monolayer (Fig. 2A). First, we measured the ability of ITC88 to limit spread of this cell-associated virus. The data show that ITC88 had minimal impact on spread with the number of infected cells increasing with culture time, which would be consistent with cell-associated virus being resistant to neutralization (Fig. 2B). Importantly, ITC88 could effectively limit the spread of a high-passage Merlin strain that grows predominantly cell-free and thus is functional in this viral-spreading assay (Fig. 2C). Similar data were also observed with healthy donor sera whereby seropositive sera were far less potent against the spread of the IE2-GFP virus whereas healthy donor seronegative sera had no effect (Fig. 2D). Having established a baseline for the assay, we next analyzed the sera from the vaccine study. The data show that seropositive sera, on average, did impact the spread of Merlin-IE2-GFP to similar levels to those observed with the control sera from natural seropositives (Fig. 2E and Fig. S4 A–D). In contrast, sera from seronegative individuals had no effect on viral spread in this assay both before and after vaccination (Fig. 2E and Fig. S4 E–H). Furthermore, the data also demonstrated that vaccination of the seropositives did not enhance the moderate inhibition of viral spread observed with the seropositive sera before vaccination (Fig. 2E and Fig. S4 A–D).

Fig. 2.

Sera from vaccinated seronegatives does not control the spread of cell-associated HCMV in vitro. (A) HFFs were infected with Merlin-IE2-GFP (MOI = 0.01), and the progress of infection was monitored for 2 wk. Representative images of GFP expression at 1, 6, 9, and 14 d post infection are shown. Cells were counterstained with DAPI to show cell layers. (B and C) HFFs infected with Merlin-IE2-GFP (B) or Merlin (C) were incubated 24 hpi with ITC88 (100 μg/mL) and viral spread assay 2 wk post infection. GFP (cell-associated) or IE immunostaining (cell-free) was used to calculate the percentage of infection. n = 3. (D) HFFs infected with Merlin (cell free) or Merlin-IE2-GFP (cell-associated) were incubated 24 hpi with no sera (control), seropositive sera, or seronegative sera. After 2 wk, GFP (cell-associated) or IE immunostaining (cell-free) was used to calculate the percentage of infection. n = 3. (E) HFFs infected with Merlin-IE2-GFP (cell-associated) were incubated 24 hpi with no sera (infected cells), healthy donor seropositive [HCMV(+)] sera, or seronegative [HCMV(−)] sera. Alternatively, HFFs were incubated with sera from either seropositive or seronegative patients given gB vaccine or placebo. Sera prevaccination and at day of transplant (post vaccination) were analyzed. After 2 wk, GFP (cell-associated) was used to calculate the percentage of infection. n = 3. Patients were further stratified into those who experienced viremia versus those who did not.

Vaccination Does Not Induce an Antibody Repertoire Capable of Promoting a Measurable ADCC Response.

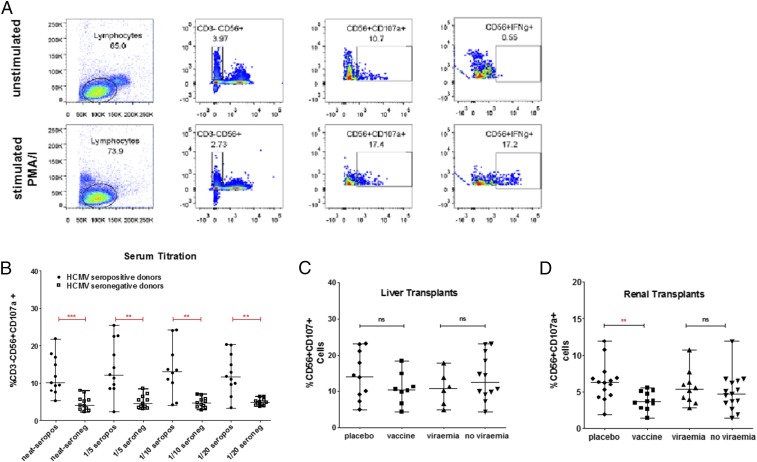

A lack of evidence to support potent neutralization led us to investigate other antibody effector mechanisms. ADCC involves antibody recognition of an epitope and the subsequent recruitment of cellular effector functions [e.g., natural killer (NK) cells] to kill the infected cell. To allow for a high-throughput screen of our sera for any potential ADCC-promoting activity, we developed an in vitro assay based on a previous study for antibodies directed against influenza proteins (21). Recombinant vaccine gB was immobilized and incubated with peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors in the presence of sera. We then analyzed NK cells by flow cytometry for evidence of CD107a expression—a classic marker of degranulation of NK cells. Validation of the assay utilized phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)/Ionomycin—a potent activator of NK cell degranulation whereby, in the presence of these activators, CD107a surface expression on CD56+ NK cells was significantly up-regulated (Fig. 3A). With this assay we could observe a differential CD107a phenotype between healthy donor seropositive and seronegative sera (Fig. 3B and Fig. S5 A and B). Having established the conditions, we tested the sera from our longitudinal vaccine study. Evidence of ADCC-promoting antibodies was evident in the seropositive patient sera both pre- and post vaccination (Fig. S5 C–E). However, there was no evidence that vaccination boosted preexisting responses in these seropositive individuals nor were levels of ADCC-promoting antibodies correlated with protection from viremia (Fig. 3 C and D).

Fig. 3.

Increased ADCC antibody responses against gB are not detected in seropositives. (A) Gating strategy to study evidence of ADCC activity. NK cells defined as CD56+CD3− were then assayed for CD107a expression or IFNg. PMA/Ionomycin was used as a positive control. (B) Titration of healthy donor sera from seropositive and seronegative donors for ability to promote CD107a expression on NK cells. (C and D) Summary of data of ADCC responses in seropositive liver and kidney organ recipients at time of transplant. Comparisons between placebo and vaccination or between viremia or no viremia shown. n = 3.

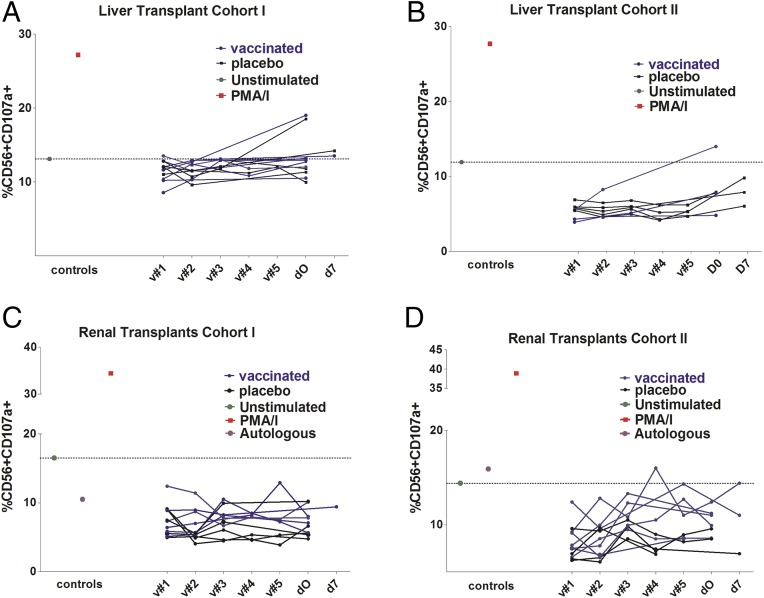

We next asked whether any effect of vaccination in seronegatives was evident. As expected, no ADCC effect was evident in the seronegative samples at baseline (i.e., prevaccination; Fig. 4 A–D). The analysis of longitudinal samples post vaccination revealed no evidence that vaccination consistently elicited detectable levels of anti-gB antibodies capable of inducing ADCC right up to the day of transplantation (Fig. 4 A–D).

Fig. 4.

Vaccination does not induce detectable ADCC antibody responses against gB in seronegatives. (A–D) Longitudinal sera samples from multiple visits were analyzed for ADCC-promoting activity. Samples were prevaccination (v#1) or 1 (v#2), 2 (v#3), 6 (v#4), and 7 (v#5) mo post vaccination or at time of transplant (d0) or 7 d post transplant (d7). Baseline negative controls are shown using unstimulated cells or healthy donor seronegative sera, and PMA/Ionomycin served as positive control.

Distinct Antibody Responses Against gB Epitopes in Vaccinated Individuals.

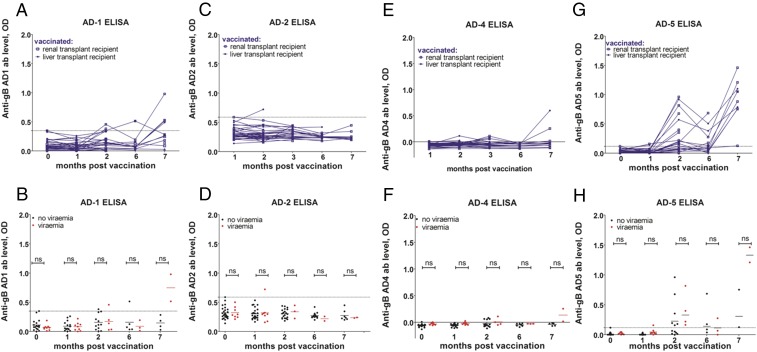

Our inability to detect evidence for neutralizing or ADCC effector functions associated with protection in the seronegative vaccine recipients led us to investigate the composition of the humoral response against key antigenic domains (AD) of HCMV. In a parallel study of seropositive individuals, we have evidence that reduced viremia post transplant correlates with higher antibody levels against AD-2 (22), consistent with this epitope being considered an important target for antibody responses (23). Thus, we asked whether vaccination of seronegatives induced specific antibody responses against known antigenic domains of gB. ELISAs were performed on serial samples of sera from seronegatives pre- and post vaccination (Fig. 5). The data show that vaccination elicited limited responses against the known ADs with no responses detectable at all against AD-2 (Fig. 5 C and D) or AD-4 (Fig. 5 E and F). In contrast, AD-1 and AD-5 responses were observed in certain individuals, but these did not correlate with protection (Fig. 5 A, B, G, and H). Thus, unlike for seropositives, no direct correlate of protection could be established with well-defined ADs of gB.

Fig. 5.

Vaccination induces a pattern of epitope responses distinct from natural infection. (A–H) ELISAs were performed on sera prevaccination (0 mo) or 1, 2, 6, and 7 mo post vaccination. Prevaccination represents background. ELISA ODs for anti-AD1 (A), AD2 (C), AD4 (E), and AD5 (G) responses are shown. Alternatively, data were stratified using outcome post transplant (B, D, F, and H) to assess impact of responses on viremia. Statistical significance was measured using a nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test. ns, nonsignificant.

Discussion

The administration of a subunit vaccine based on the key viral glycoprotein B of HCMV is a potent inducer of anti-gB antibodies (6, 9, 11). Furthermore, the level of these antibodies correlated with reduced viral load parameters in a randomized phase 2 trial in solid organ transplant recipients (9). These data support the concept that the induction of a potent humoral response against gB represents a good strategy to protect from HCMV disease. However, despite this understanding of improved clinical outcome, the mechanistic basis of protection is still not fully understood.

Classically, the induction of potent neutralizing antibody responses has been considered the gold standard for evaluating any vaccine strategy (18, 24). Indeed, a number of successful vaccination programs have utilized vaccines that do exactly this (24). However, in this study we could provide no supporting evidence for a potent neutralizing antibody response as an explanation for the success of the gB HCMV vaccine. The data show that the sera of seropositive transplant recipients possessed neutralizing antibodies, but these were not detectably enhanced by vaccination with gB/MF59. Most likely, these potent antibodies are a composite of anti-gB and other major glycoprotein targets including the trimer gH/gL/gO and the pentameric complex (25). Consistent with these glycoproteins being targets for neutralization are data that demonstrate that monoclonal antibodies directed against gH or the pentameric complex neutralize infection effectively (26–28). Recent work has demonstrated that cell-associated HCMV growth is largely resistant to the activity of Cytotect (a heterogeneous mix of anti-HCMV antibodies), presumably because the physical state of the virus denies access to neutralizing antibodies (20) consistent with a previous report (29). Our data presented here support those observations; a minor effect of seropositive sera on decreasing the rate of spread in vitro could be explained by small amounts of cell-free virus made by the Merlin-IE2-GFP strain of HCMV.

It is likely then that biphasic modes of growth (i.e., cell-free and cell-associated) in vivo would argue that an effective vaccine against HCMV could be dependent on the induction of multiple humoral effector functions. Thus, while there is still a role for a vaccine that can induce neutralizing antibody responses, these clinical trial data argue that a vaccine against HCMV can be effective despite an inability to detect a potent neutralizing response associated with it. More generally, they reinforce the value of assessing vaccination strategies using challenge models. A recent study in mice concluded that vaccination with AD-2 was not useful because a poor neutralizing response was elicited. However, it was never addressed whether the vaccination with AD-2 was protective against CMV challenge (30). Indeed, a recent study presents data implicating a role for both neutralizing and nonneutralizing gB antibody responses in the murine cytomegalovirus challenge model (31). Furthermore, this concept may not be restricted to HCMV because human studies of a candidate HIV vaccine reported that a major component of the antiviral humoral response correlated with ADCC (32, 33).

In contrast to acute viral infections, HCMV persists for the lifetime of the host in the face of a prodigious immune response (33). HCMV encodes multiple immune evasion genes to facilitate lifelong survival in the host and ability to reinfect new hosts, even those with preexisting natural immunity against HCMV. This illustrates the complex interactions of HCMV with the immune response, and the ability of this virus to persist in the face of a potent immune response may impact on the ability to produce a sterilizing vaccine based solely on the induction of neutralizing antibodies. Put simply, sera from seropositives are potently neutralizing in vitro, but reinfection with HCMV is possible in vivo. Consequently, we investigated the ability of sera from vaccinated patients to enhance antibody-dependent responses. NK cells can be recruited in an antibody-dependent manner to promote cellular cytotoxicity. HCMV encodes a number of NK immune evasion genes, which suggests that this is an important functional interaction (34). Furthermore, the NK-cell repertoire in HCMV seropositive individuals is dominated by subsets of NK cells—with an implication of NK-cell memory (35). Whether these NK cell subsets are elite controllers of HCMV or, instead, reflect a virally induced reprogramming remains an important open question. Clearly, seropositives invoke anti-gB responses that could direct NK-cell–mediated ADCC based on our work. However, we could not attribute the success of the vaccine to this so that, while anti-gB antibodies exist that promote ADCC, we could provide no evidence that this explained the protection afforded by the vaccine. The development of antibodies that promote ADCC responses may be triggered following initial exposure to the pathogen or a focusing of the immune response through multiple episodes of reactivation. A vaccine clearly does not deliver these additional exposures to the immune system. Indeed, the vaccine delivers gB in the absence of other pathogen-encoded functions and thus, potentially, presents gB in a unique way. Whether this allows potent anti-HCMV responses to develop more effectively than they would in the context of infection is an important question for vaccine studies to address. Finally, it is important to avoid suggesting that ADCC responses have no role to play. Our data show that ADCC responses directed against gB are not detectable (seronegative vaccinees), boosted (seropositive vaccinees), or correlate with protection (seropositive patients cohort). However, our data do not rule out ADCC responses against other HCMV antigens being important for control in natural infection.

Although the mechanistic correlate of protection remains to be determined, it is evident that the gB HCMV vaccine is protective (6, 9, 11). Interestingly, the epitope analysis points toward the exciting hypothesis that a novel epitope may be responsible. The vaccine gB is modified in the transmembrane domain as well through the loss of the furin cleavage site and is thought to exist in a postfusion form. All these differences may result in the presentation of novel epitopes of gB not normally exposed in the virion but transiently exposed during the entry process or in HCMV-infected cells. Studies are ongoing to test the hypothesis of novel epitopes being presented by the vaccine form of gB.

In conclusion, the data in this human challenge model demonstrate that the effectiveness of the gB vaccine is imparted by a mechanism and not wholly reliant on the classic biological activity of neutralization.

Materials and Methods

The study was approved by the University College London Research Ethics Committee, and all patients whose samples were investigated here gave written informed consent (9).

To assess sera for neutralizing capacity, HCMV was preincubated with sera for 1 h, and then the whole sample was used to infect human fetal fibroblasts (HFFs). Alternatively, virus was incubated with anti-gB antibody 2F12 (Abcam) or anti–AD-2 monoclonal antibody ITC88 (23, 36). After 24 h, cells were fixed and stained for IE gene expression using anti-IE (Millipore; 1:1,000) and goat anti-mouse Alexafluor 568 nm (Life Technologies; 1:1,000). Alternatively, an anti-pp28 antibody (Santa Cruz; 1:1,000) was used to stain cells fixed at 72 hpi and detected with the same secondary antibody. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma). Percentage infection was enumerated using Hermes WiScan instruments and software.

Either a high-passage Merlin (grows cell-free) or an IE2-GFP virus engineered to grow predominantly cell-associated [gift of Richard Stanton (20)] was used to infect HFFs at an MOI of 0.01. Cells were either fixed and stained for IE (Merlin) or visualized for GFP expression (IE2-GFP) between 1 and 14 d post infection. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Sigma). Percentage infection was enumerated using Hermes WiScan instruments and software.

To assay for ADCC-promoting antibodies, total PBMCs or purified NK cells (MACS NK-cell isolation kit II; Miltenyi Biotec) from seronegative healthy donors were used. Briefly, 96-well plates were coated with gB vaccine protein (0.75 μg/well) and then incubated with sera diluted in PBS as described. Either PBMCs or NK cells were added to the wells, and, 48 h later, the cells were harvested and stained for CD3, CD56, and CD107a expression (BD Biosciences) and enumerated by Flow cytometry. Stimulation with PMA and Ionomycin was used as a positive control, and healthy seronegative donor sera as a negative control. Additionally, sera isolated prevaccination from seronegatives was used as a baseline negative response.

ELISAs for AD1, -2, -4, and -5 have been described previously (15). AD1 and AD2 are nonstructured epitopes, and it is well established that the peptides are recognized by AD1 and AD2 antibody responses. The recombinant AD4 used has been shown to be recognized by known AD4 conformational antibodies, and the structure of the AD5 antigen has been shown to have the same structure as AD5 in gB (15, 37, 38). Briefly, sera was diluted in PBS as described and then incubated with peptide coated 96 well plates. Healthy seropositive and seronegative sera were used as controls. Anti-human IgG conjugated to HRP was used to detect CMV antibodies and visualized using 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine substrate. OD was measured at 450 nm. Visit 1 (e.g., prevaccination of seronegative patients) was set as background/baseline.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the European Union under the FP7 Marie Curie Action, Grant 316655 (VacTrain); Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grant MA 929/11-1; and the Wellcome Trust Grant WT/204870/Z/16/Z. M.B.R. was supported by a Medical Research Council Fellowship (G:0900466). The original clinical trial of gB/MF59 was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Grant R01AI051355 and by Sanofi Pasteur.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: Sylvie Pichon is an employee of Sanofi Pasteur. However, there are no personal financial gains regarding the publication of this manuscript.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

See Commentary on page 6110.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1800224115/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Legendre C, Pascual M. Improving outcomes for solid-organ transplant recipients at risk from cytomegalovirus infection: Late-onset disease and indirect consequences. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:732–740. doi: 10.1086/527397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffiths P, Baraniak I, Reeves M. The pathogenesis of human cytomegalovirus. J Pathol. 2015;235:288–297. doi: 10.1002/path.4437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arvin AM, Fast P, Myers M, Plotkin S, Rabinovich R. National Vaccine Advisory Committee Vaccine development to prevent cytomegalovirus disease: Report from the National Vaccine Advisory Committee. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:233–239. doi: 10.1086/421999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernstein DI, et al. Randomized, double-blind, Phase 1 trial of an alphavirus replicon vaccine for cytomegalovirus in CMV seronegative adult volunteers. Vaccine. 2009;28:484–493. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Plotkin SA, et al. Multicenter trial of Towne strain attenuated virus vaccine in seronegative renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1994;58:1176–1178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pass RF, et al. Vaccine prevention of maternal cytomegalovirus infection. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1191–1199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schleiss MR. Cytomegalovirus vaccines under clinical development. J Virus Erad. 2016;2:198–207. doi: 10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30872-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adler SP, et al. Immunity induced by primary human cytomegalovirus infection protects against secondary infection among women of childbearing age. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:26–32. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Griffiths PD, et al. Cytomegalovirus glycoprotein-B vaccine with MF59 adjuvant in transplant recipients: A phase 2 randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1256–1263. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60136-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schleiss MR. VCL-CB01, an injectable bivalent plasmid DNA vaccine for potential protection against CMV disease and infection. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2009;11:572–578. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernstein DI, et al. Safety and efficacy of a cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B (gB) vaccine in adolescent girls: A randomized clinical trial. Vaccine. 2016;34:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isaacson MK, Juckem LK, Compton T. Virus entry and innate immune activation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:85–100. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isaacson MK, Compton T. Human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B is required for virus entry and cell-to-cell spread but not for virion attachment, assembly, or egress. J Virol. 2009;83:3891–3903. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01251-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen L, Matkin C, Spaete R, Pachl C, Merigan TC. Antibody response to human cytomegalovirus glycoproteins gB and gH after natural infection in humans. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:835–842. doi: 10.1093/infdis/164.5.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pötzsch S, et al. B cell repertoire analysis identifies new antigenic domains on glycoprotein B of human cytomegalovirus which are target of neutralizing antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002172. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banks T, et al. A major neutralizing domain maps within the carboxyl-terminal half of the cleaved cytomegalovirus B glycoprotein. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:979–985. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-4-979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu LL, Suscovich TJ, Fortune SM, Alter G. Beyond binding: Antibody effector functions in infectious diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:46–61. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ. Broadly neutralizing antibodies and the search for an HIV-1 vaccine: The end of the beginning. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:693–701. doi: 10.1038/nri3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shiraki K, et al. Neutralizing anti-gH antibody of Varicella-zoster virus modulates distribution of gH and induces gene regulation, mimicking latency. J Virol. 2011;85:8172–8180. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00435-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murrell I, et al. The pentameric complex drives immunologically covert cell-cell transmission of wild-type human cytomegalovirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:6104–6109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704809114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jegaskanda S, et al. Cross-reactive influenza-specific antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity antibodies in the absence of neutralizing antibodies. J Immunol. 2013;190:1837–1848. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baraniak I, et al. Epitope-specific humoral responses to human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein-B vaccine with MF59: Anti-AD2 levels correlate with protection from Viremia. J Infect Dis. 2018 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohlin M, Sundqvist VA, Mach M, Wahren B, Borrebaeck CA. Fine specificity of the human immune response to the major neutralization epitopes expressed on cytomegalovirus gp58/116 (gB), as determined with human monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1993;67:703–710. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.703-710.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burton DR. Antibodies, viruses and vaccines. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:706–713. doi: 10.1038/nri891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cui X, Meza BP, Adler SP, McVoy MA. Cytomegalovirus vaccines fail to induce epithelial entry neutralizing antibodies comparable to natural infection. Vaccine. 2008;26:5760–5766. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fouts AE, et al. Mechanism for neutralizing activity by the anti-CMV gH/gL monoclonal antibody MSL-109. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:8209–8214. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404653111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manley K, et al. Human cytomegalovirus escapes a naturally occurring neutralizing antibody by incorporating it into assembling virions. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:197–209. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kabanova A, et al. Antibody-driven design of a human cytomegalovirus gHgLpUL128L subunit vaccine that selectively elicits potent neutralizing antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:17965–17970. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415310111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacob CL, et al. Neutralizing antibodies are unable to inhibit direct viral cell-to-cell spread of human cytomegalovirus. Virology. 2013;444:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finnefrock AC, et al. Preclinical evaluations of peptide-conjugate vaccines targeting the antigenic domain-2 of glycoprotein B of human cytomegalovirus. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2016;12:2106–2112. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1164376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bootz A, et al. Protective capacity of neutralizing and non-neutralizing antibodies against glycoprotein B of cytomegalovirus. PLoS Pathog. 2017;13:e1006601. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corey L, et al. Immune correlates of vaccine protection against HIV-1 acquisition. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:310rv7. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac7732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haynes BF, et al. Immune-correlates analysis of an HIV-1 vaccine efficacy trial. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1275–1286. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jackson SE, Mason GM, Wills MR. Human cytomegalovirus immunity and immune evasion. Virus Res. 2011;157:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muntasell A, Vilches C, Angulo A, López-Botet M. Adaptive reconfiguration of the human NK-cell compartment in response to cytomegalovirus: A different perspective of the host-pathogen interaction. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:1133–1141. doi: 10.1002/eji.201243117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reeves MB, Breidenstein A, Compton T. Human cytomegalovirus activation of ERK and myeloid cell leukemia-1 protein correlates with survival of latently infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:588–593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1114966108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiegers AK, Sticht H, Winkler TH, Britt WJ, Mach M. Identification of a neutralizing epitope within antigenic domain 5 of glycoprotein B of human cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 2015;89:361–372. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02393-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spindler N, et al. Structural basis for the recognition of human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein B by a neutralizing human antibody. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004377. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.