Abstract

While migration has been shown to be a risk factor for HIV, variation in HIV prevalence by subgroups of migrants needs further exploration. This paper documents the HIV prevalence and key characteristics among male foreign migrants in Cape Town, South Africa and the effectiveness of respondent-driven sampling (RDS) to recruit this population. Participants in this cross-sectional study completed a behavioral risk-factor questionnaire and provided a dried blood sample for HIV analysis. Overall HIV prevalence was estimated to be 8.7 % (CI 5.4–11.8) but varied dramatically by country of origin. After adjusting for country of origin, HIV sero-positivity was positively associated with older age (p = 0.001), completing high school (p = 0.025), not having enough money for food (p = 0.036), alcohol use (p = 0.049), and engaging in transactional sex (p = 0.022). RDS was successful in recruiting foreign migrant men. A better understanding of the timing of HIV acquisition is needed to design targeted interventions for migrant men.

Keywords: HIV surveillance, Migration, Gender, Behavioral risk, South Africa

Introduction

Migration has been shown to be a key risk factor for HIV acquisition in populations around the world [1–3]. However, different types of migrating populations are not homogenous in their risk profiles. Forced migrants fleeing disaster and conflict are more susceptible to HIV through increased exposure to sexual violence and limited access to health services and condoms [4, 5]. Internal migrants experience disruptions in family structure and increased risk-taking behavior, which places these individuals at higher risk for HIV transmission [6–8]. Transnational economic migrants may be a particularly vulnerable group as they additionally face issues with language skills, legal documentation, and xenophobic attitudes [9, 10].

South Africa is one of the few countries in sub-Saharan Africa that does not require forced or irregular migrants to reside in refugee camps, which often restrict the movement, employment opportunities, and residence choice for migrants [11]. This policy, in combination with the country’s relative economic and political stability, has made the country a magnet for transnational migrant populations. It was estimated that in 2010 foreign migrants accounted for almost 4 % of the South African population, of which 57 % were male [12]. South Africa also has one of the highest HIV prevalence rates (18.9 %) in the world [13]. The complex interaction between South Africa’s HIV epidemic, the HIV epidemics in migrant’s communities of origin in sub-Saharan Africa, and the large foreign migrant population within South Africa has resulted in the addition of cross-border migrants as a key target population in South Africa’s National Strategic Plan for HIV and AIDS, STIs and TB, 2012–2016 [14].

A more nuanced understanding of the epidemiologic profile of HIV in specific migrant populations within South Africa is required in order to design and implement effective HIV prevention, treatment, and care programs for this vulnerable population. Studies have documented the increased risk for HIV and STIs among male internal migrants in South Africa [15–17]. Further, a recent study of a specific subgroup of transnational migrant men (Mozambican workers in South Africa mines), documented an HIV prevalence of 22.3 % [18]. However, to date there is no empirical evidence that systematically documents HIV prevalence or associated risk behaviors among a broad population of transnational migrant men living in South Africa. HIV surveillance conducted among this population is needed in order to track changes in HIV prevalence and risk behaviors and provide an early-warning system for potential HIV outbreaks if necessary. The goal of this paper is to document the methods used in an HIV surveillance study of transnational migrant men in Cape Town, South Africa, report sample and population estimates of HIV prevalence and other risk factors, describe key characteristics among these men, and describe the effectiveness of respondent-driven sampling (RDS) to recruit this hidden population.

Methods

Formative Research

Formative research was conducted in April 2013 with service providers and key informants who work with the target population, in accordance with recommendations from researchers with vast field experience conducting RDS studies among vulnerable populations [19]. The goals of this research were to determine the appropriateness of using RDS to sample and recruit the study population as well as identifying appropriate study venues, study languages, incentives, and methods for seed and field staff recruitment.

Study Setting

Study activities were conducted from August to October 2013 in a centrally located venue in Cape Town. The venue had private rooms for biological sample collection and for HIV counseling and testing. Completion of a survey questionnaire was done in two large rooms where participants were afforded complete privacy. The study employed 24 fieldworkers; two administrators for coupon and incentive disbursement, one HIV counselor, one blood spot collector, and 18 individuals who acted as interpreters and assisted with survey administration (two for each of the nine study languages). All personnel underwent comprehensive training that included research ethics, RDS procedures, familiarization with the electronic barcoding system, and the Audio Computer-Assisted Self-Interview (ACASI) questionnaire.

Participants

Men were eligible to participate if they were cross-border migrants between the ages of 18 and 54 and lived, worked or socialized in Cape Town or its surrounding suburbs. Men who could not speak one of the nine study languages (English, French, Chichewa, Lingala, Kinyarwanda, Por-tuguese, Shona, Swahili or Somali) were excluded. Eligibility was assessed on intake through a short questionnaire. RDS analysis procedures require an accurate social network size from each participant, which is used to weight the data. To assess network size, three questions were included in the intake questionnaire to maximize accurate reporting: (1) “How many foreign migrant men do you know (they know your name and you know theirs) and they live/work or socialize in Cape Town?” (2) “How many of these men have you spent time with in the past 3 months?” (3) “How many of these men are between 18 and 54 years of age?”

Sampling and Data Collection

Participants were recruited using RDS. This method uses a chain referral technique designed to provide access to hidden and hard-to-reach populations for which no sampling frame exists [20]. RDS attempts to minimize the biases inherent in other chain referral methods by accounting for social network structures and recruitment probabilities, thereby allowing for more representative population-based parameters to be estimated [20, 21]. The RDS sampling and recruitment process begins with a predetermined number of seeds who are non-randomly identified from the underlying population of interest. These seeds are given a fixed number of coupons to recruit peers to participate in the study. Recruits who return to the study site, meet eligibility criteria, and participate in the study become the first wave of participants. After participation, these individuals become recruiters and are given the set number of coupons to recruit their peers. This process continues through multiple waves until the desired sample size and equilibrium is reached on key variables.

The 16 seeds for the current study were identified by community key informants. Potential seeds were screened for eligibility and selected based on pre-determined characteristics of successful seeds for RDS (having large social networks, being respected by members of the target population, ability to convince others to participate, and representing key age and country of origin sub-populations) [22]. All participants completed an intake questionnaire to determine eligibility. To detect possible repeat enrolment, participants provided fingerprints that were stored in a secure on-line database. This also allowed for participants to remain anonymous; no identifying information was collected. Fingerprints were transformed into bar-codes that became the study’s unique identifiers and linked all study materials. Eligible participants completed an ACASI questionnaire in the language of their choice. Blood spots were collected by a registered nurse and sent to a laboratory for analysis. Participants were additionally offered HIV counseling and rapid testing if they wished to know their HIV status on site. Participants who received positive results from the rapid HIV test were referred to a local clinic for further testing and treatment. Seeds and recruits were issued four coupons with which to recruit peers into the study. Participants were given a ZAR60 (± US $6) supermarket voucher once they had completed the survey and provided blood spots. An additional voucher valued at ZAR20 (± US $2) was issued to the recruiter for each recruit of their recruits who completed the study procedures. Ethical clearance was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Health Sciences, at the University of Cape Town.

Measures

The main outcome for this analysis is HIV serostatus. Participants who agreed provided dried blood spots (DBS) for biological testing. DBS samples were sent to a referral laboratory (Global Clinical and Viral Laboratory, Durban, South Africa) for analyses. The anonymous HIV analyses were conducted in accordance with 2013 WHO guidelines for testing scenarios where participants do not receive results. Samples were initially tested using Vironostika HIV Uniform II plus 0. Reactive samples were re-tested using a 3rd generation ELISA. Samples that were reactive in both assays were reported as positive. Discordant samples (n = 10, 2 %) were further tested using Western Blot (HIV ½ Biorad).

The behavioral risk assessment questionnaire comprised of 129 items. This analysis focused on demographic, migration, and behavioral risk factors that were theorized to be predictive of HIV serostatus. Demographic characteristics were age, education status, main source of income, poverty status, marital status, and housing type. Migration-related factors included country of origin, length of time in South Africa, legal documentation status, and the main reason the participant decided to migrate (push/pull factor). Number of sexual partners, inconsistent condom use, and whether the respondent traded money or other goods/services for sex (transactional sex) were assessed for the past 3 months. We also investigated condom use at last sexual encounter, anal sex in the previous 6 months, alcohol use frequency in the past 12 months, and self-reported STI symptoms (painful urination, discharge, or sores/ulcers) in the past 3 months.

Sample Size

Since HIV prevalence among foreign migrant men in South Africa is not documented, we calculated the sample size using 2010 HIV prevalence data from men in a high-risk community in Cape Town (21.9 %) as a proxy [23]. There has been debate over an appropriate design effect for the sample size calculation in RDS studies. Recent consensus suggests that a design effect closer of three or four might be best but that two is reasonable [24, 25]. This study chose a slightly more conservative design effect of 2.5. Thus, allowing for an error margin of 5 %, we calculated the required minimum sample size for HIV prevalence to be 532.

Data Analysis

Sample proportions, estimates of population proportions, 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) for all study variables were calculated using the RDS Analysis Tool 7.1.38 (RDSAT) (www.respondentdrivensampling.org). RDSAT creates sample weights that take into account participants’ network sizes, differential recruitment, and homophily (extent to which participants recruit peers who are similar or different from them on a given variable). Population estimates were derived using information about each participant’s social network size (degree) and cross- and within-group recruitment patterns (who recruited who) [21, 26]. In bivariate analyses, we estimated crude risk ratios of HIV status by all covariates separately. Next, we estimated risk ratios of HIV status adjusted for country of origin, as there was considerable variation in HIV prevalence by country of origin. Crude and adjusted risk ratios were estimated using log-binomial regression and weighted with RDSAT generated HIV population and individualized weights, respectively. All risk ratios and corresponding p values were calculated using STATA, version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

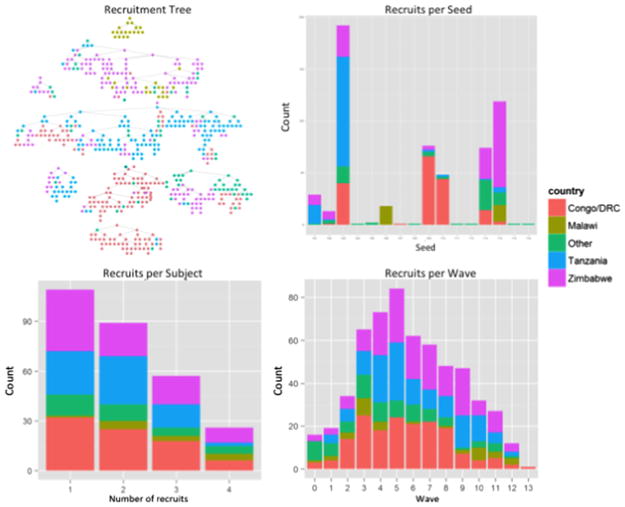

Sixteen seeds were recruited during the study period (Table 1); 14 in the first 3 weeks and 2 additional seeds (from Somalia and Mozambique) in weeks 8 and 9, as very few recruits from these countries had presented at the study site. Half of these seeds were unproductive. Of the remaining 8, 5 generated 40 or more recruits over a maximum of 13 waves. Nineteen percent (n = 110) of participants successfully recruited 1 peer, 15 % (n = 89) recruited 2, 10 % (n = 58) recruited 3, and 5 % (n = 27) recruited 4 (Fig. 1). A total of 1538 recruitment coupons were issued over the study period, of which 598 (38.9 %) were redeemed. Twenty of the men who arrived at the study site were found ineligible; 9 did not live, work, or socialize in Cape Town, Two were under the age of 16, One was over the age of 54, Two were South African, and six were identified as attempting to repeat participation and were turned away without enrolling. Including the initial seeds, this process resulted in a final N of 578.

Table 1.

Seed characteristics and recruitment data for the Men’s Health and Migration Project, Cape Town, South Africa, 2013

| Seed# | Country of origin | Date enrolled | Week | Number of waves of recruitment | Number of recruits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Zimbabwe | 8/31/2013 | 1 | 6 | 28 |

| B | Zimbabwe | 8/31/2013 | 1 | 4 | 12 |

| C | Zimbabwe | 9/1/2013 | 1 | 13 | 191 |

| D | Zambia | 9/1/2013 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| E | Angola | 9/7/2013 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| F | Malawi | 9/7/2013 | 2 | 4 | 17 |

| G | Congo/DRC | 9/8/2013 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| H | Nigeria | 9/8/2013 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| I | Congo/DRC | 9/8/2013 | 2 | 11 | 75 |

| J | Congo/DRC | 9/8/2013 | 2 | 6 | 47 |

| K | Somalia | 9/14/2013 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| L | Somalia | 9/14/2013 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| M | Rwanda | 9/14/2013 | 3 | 9 | 73 |

| N | Rwanda | 9/14/2013 | 3 | 12 | 118 |

| O | Somalia | 10/19/2013 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| P | Mozambique | 10/16/2013 | 8 | 0 | 0 |

Fig. 1.

Recruitment diagnostics for the Men’s Health and Migration Project by participant country of origin. Recruitment Tree network plot of the RDS recruitment process. Recruits per Seed total tree size (i.e. number of participants successfully recruited into the study) for each seed. Recruit per Subject number of participants successfully recruited by non-terminal participants. In this study, every active nonterminal participant recruited 1, 2, 3, or 4 participants. Recruits by Wave number of participants recruited within each wave

Network homophily indices close to 0 suggest that social ties among recruits and recruiters crossed networks. With the exception of country of origin, simulated equilibrium estimates were reached for all variables between 1 and 5 waves of recruitment, and indices of homophily indicated there was little preference for either in- or out-group recruiting (Table 2). However, homophily indices for country of origin showed clear within-country recruitment patterns (between 0.858 and 0.522), and equilibrium was not reached on this variable (Table 2). With the exception of one small recruitment chain, all other chains had some cross-over by country of origin (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics, HIV risk factors, recruitment waves and indices of homophily among foreign migrant men in Cape Town, South Africa, 2013 (n = 578)

| Variable | Equa | Hxb | Sample Nc | Sample %d | RDS adjusted % | 95 % CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age (Missing = 0) | ||||||

| 16–24 | 5 | 0.305 | 134 | 23.2 | 28.0 | 22.0–34.4 |

| 25–29 | 2 | 0.091 | 164 | 28.4 | 28.3 | 22.9–34.0 |

| 30–34 | 4 | 0.097 | 153 | 26.5 | 23.4 | 18.3–28.8 |

| 35–54 | 4 | 0.236 | 127 | 22.0 | 20.2 | 14.9–26.2 |

| Education status (Missing = 0) | ||||||

| Primary school or less | 4 | 0.284 | 187 | 32.4 | 34.6 | 27.8–41.5 |

| Some high school | 3 | 0.168 | 108 | 18.7 | 19.2 | 14.2–24.9 |

| Completed high school | 4 | 0.417 | 283 | 49.0 | 46.2 | 38.8–53.4 |

| Main source of income (Missing = 2) | ||||||

| None | 1 | −0.048 | 87 | 15.1 | 15.8 | 11.5–20.3 |

| Wife/family members | 2 | 0.123 | 108 | 18.2 | 19.0 | 14.6–24.1 |

| Paid work/employment | 2 | 0.122 | 197 | 34.2 | 35.5 | 29.3–41.4 |

| Own business | 2 | 0.203 | 146 | 25.4 | 21.1 | 16.5–26.5 |

| Shady deals/transactional sex/other | 1 | 0.034 | 38 | 6.6 | 8.7 | 4.8–13.3 |

| Poverty status (Missing = 4) | ||||||

| Enough money for basics or more | 1 | 0.112 | 294 | 53.8 | 50.8 | 44.8–56.8 |

| Not enough money for food | 1 | 0.016 | 253 | 46.2 | 49.2 | 43.2–55.2 |

| Marital status (Missing = 2) | ||||||

| Married, living with wife | 2 | 0.152 | 134 | 23.3 | 22.0 | 16.9–27.1 |

| Married, not living with wife | 2 | 0.047 | 107 | 18.6 | 22.2 | 17.0–27.7 |

| Unmarried, living with sexual partner | 2 | 0.080 | 101 | 17.5 | 15.9 | 11.7–20.6 |

| Unmarried, not living with sexual partner | 1 | 0.076 | 234 | 40.6 | 39.9 | 34.0–46.1 |

| Housing type (Missing = 0) | ||||||

| Shack/backyard dwelling | 2 | 0.158 | 272 | 47.1 | 48.6 | 42.6–55.3 |

| Brick house/apartment and other types | 2 | 0.247 | 306 | 52.9 | 51.4 | 44.7–57.4 |

| Migration factors | ||||||

| Country of origin (Missing = 0) | ||||||

| Zimbabwe | 17 | 0.759 | 165 | 28.6 | 26.6 | 16.5–39.1 |

| Congo/DRC | 23 | 0.858 | 169 | 29.2 | 29.4 | 17.4–43.7 |

| Malawi | 12 | 0.735 | 34 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 0.7–13.9 |

| Tanzania | 13 | 0.743 | 135 | 23.4 | 27.5 | 16.1–39.1 |

| Other | 5 | 0.522 | 75 | 13.0 | 10.7 | 5.8–15.4 |

| Length of stay in south africa (Missing = 0) | ||||||

| 12 months or less | 3 | 0.171 | 100 | 17.3 | 24.8 | 18.9–31.2 |

| 13 months–5 years | 2 | 0.123 | 288 | 49.8 | 50.6 | 44.2–56.9 |

| > 5 years | 3 | 0.286 | 190 | 32.9 | 24.6 | 19.2–30.4 |

| Documentation (Missing = 0) | ||||||

| Asylum/Refugee/Visa/Other | 1 | 0.059 | 479 | 82.9 | 78.2 | 72.4–83.4 |

| No papers | 1 | 0.307 | 99 | 17.1 | 21.8 | 16.6–27.6 |

| Main push/pull factor (Missing = 0) | ||||||

| To find work | 3 | 0.246 | 228 | 39.5 | 44.8 | 37.9–51.8 |

| To get a better education | 3 | 0.239 | 94 | 16.3 | 17.1 | 12.5–22.7 |

| Escaping political persecution | 2 | 0.142 | 160 | 27.7 | 23.0 | 17.9–28.6 |

| Unhappy home life/other | 2 | −0.012 | 96 | 16.6 | 15.1 | 10.8–18.8 |

| Behavioral HIV risk factors | ||||||

| Alcohol use frequency in the past 12 months (Missing = 2) | ||||||

| Never | 2 | 0.120 | 271 | 47.1 | 47.7 | 41.8–53.8 |

| A few times a month or less | 2 | 0.071 | 214 | 37.2 | 35.0 | 29.3–40.5 |

| Weekly | 1 | 0.093 | 91 | 15.8 | 17.3 | 12.5–23.2 |

| STI symptoms in past 3 months (Missing = 2) | ||||||

| No | 1 | 0.112 | 464 | 80.6 | 79.4 | 73.6–84.4 |

| Yes | 1 | 0.030 | 122 | 19.4 | 20.6 | 15.6–26.4 |

| Number of sexual partners in past 3 months (Missing = 28) | ||||||

| None | 2 | 0.022 | 150 | 27.2 | 30.8 | 25.1–37.9 |

| One | 1 | 0.041 | 216 | 39.3 | 34.9 | 29.8–41.9 |

| Two | 1 | −0.338 | 74 | 13.5 | 16.4 | 10.6–19.8 |

| Three or more | 2 | 0.023 | 110 | 20.0 | 17.9 | 13.4–22.1 |

| Anal sex with a man in the past 6 months (Missing = 4) | ||||||

| None | 1 | 0.067 | 451 | 94.3 | 93.8 | 89.9–97.0 |

| Any | 1 | 0.180 | 33 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 3.0–10.1 |

| Transactional sex in the past 3 months (missing = 4) | ||||||

| None | 1 | 0.014 | 417 | 72.7 | 73.0 | 67.7–78.2 |

| Any | 1 | 0.038 | 157 | 27.4 | 27.0 | 21.8–32.3 |

| Sexual risk factors among recently sexually active men (N = 428) | ||||||

| Condom use frequency (Missing = 27) | ||||||

| Inconsistent | 1 | 0.175 | 241 | 60.1 | 52.8 | 41.9–60.7 |

| Always | 1 | −0.112 | 160 | 39.1 | 47.2 | 39.3–58.1 |

| Condom use at last sex (Missing = 24) | ||||||

| No | 1 | 0.059 | 129 | 31.9 | 26.4 | 20.1–33.9 |

| Yes | 1 | −0.076 | 275 | 68.1 | 73.6 | 66.1–79.9 |

Number of waves expected to reach Equilibrium

Homophily index

N’s may not sum to 578 due to missing data

Valid percents shown

The recruitment process resulted in a final sample of 578 migrant men who reported an average network size of 13.2 (range 1–350). In the RDS-adjusted analysis (Table 2, columns 6–7), just under half (46.2, 95 % CI 38.8–53.4) had completed high school. The majority reported an income generating activity, with 35.5 % (95 % CI 29.3–41.4) reporting having employment and 21.1 % (95 % CI 6.5–26.5) owning their own business. While 15.8 % (95 % CI 11.5–20.3) of men had no source of income, approximately half (49.2, 95 % CI 43.2–55.2) did not have enough money for food. Just over one-third (39.9, 95 % CI 34.0–46.1) were unmarried and not living with a sexual partner, and 15.9 % (95 % CI:11.7–20.6) were unmarried but living with a sexual partner. A smaller proportion of men were married, with 22 % (95 % CI 16.9–27.1) living with their wife and 22.2 % (95 % CI 17.0–27.7) not living with their wife. Just under half (48.6, 95 % CI:42.6–55.3) of men were living in a non-permanent housing structure. Most men came from Congo/DRC (29.2, 95 % CI 17.4–43.7), Tanzania (27.5, 95 % CI 6.1–39.1), or Zimbabwe (26.6, 95 % CI 16.5–39.1), and had lived in South Africa for 1–5 years (50.6, 95 %:CI 44.2–56.9). Approximately one in five men (21.8, 95 % CI 16.6–27.6) had no legal documentation. The majority of men (44.8, 95 % CI 37.9–51.8) came to South Africa in search of work.

Only 17.3 % (95 % CI 12.5–23.2) of men reported using alcohol on a weekly basis or more. The majority of men were recently sexually active, and 17.9 % (95 % CI 13.4–22.1) had 3 or more sexual partners in the past 3 months. Anal sex with a man in the past 6 months was uncommon (6.2, 95 % CI 3.0–10.1), and 27 % of men (95 % CI 21.8–32.3) reported exchanging money or goods for sex in the past 3 months. Among men who were sexually active in the past 3 months, 52.8 % (95 % CI 41.9–60.7) used condoms inconsistently and 26.4 % (95 % CI 20.1–33.9) did not use a condom during their last sexual encounter.

An estimated 20.6 % of men (95 % CI 15.6–26.4) reported an STI symptom in the past 3 months. The overall RDS-adjusted HIV seroprevalence was 8.7 % (95 % CI 5.4–11.8), but this varied widely by country of origin (Table 3); HIV seroprevalence was highest among migrant men from Zimbabwe (15.5, 95 % CI 6.2–23.4) and from Malawi (24.3, 95 % CI 0.1–88.3). Migrant men from Congo/DRC had the lowest HIV seroprevalence at 1.2 % (95 % CI 0.0–2.7).

Table 3.

HIV seroprevalence among foreign migrant men in Cape Town, South Africa 2013: overall and by country of origin (n = 578)

| Sample N | Sample %a | RDS adjusted % | 95 % CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (Missing = 28) | 48 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 5.4–11.8 |

| By country of origin | ||||

| Zimbabwe | 27 | 16.7 | 15.5 | 6.2–23.4 |

| Congo/DRC | 3 | 2.0 | 1.2 | 0.0–2.7 |

| Malawi | 6 | 20.0 | 24.3 | 0.1–88.3 |

| Tanzania | 7 | 5.2 | 3.8 | 0.8–8.2 |

| Other | 5 | 6.9 | 10.5 | 1.9–28.5 |

Valid percents shown

In the analyses adjusted for country of origin (Table 4), men were more likely to be HIV positive if they were in the oldest age group (35–54) (aRR = 4.06, 95 % CI 1.73–9.54), were unmarried and living with a sexual partner compared to men who were married and living with their wife (aRR = 2.97, 95 % CI 1.74–9.05), did not have enough money for food (aRR = 1.86, 95 % CI 1.04–3.33), had completed high school compared to men with a primary school education or less (aRR = 2.38, 95 % CI 1.12–5.06), used alcohol weekly as compared to never (aRR = 1.90, 95 % CI 1.01–3.69), and reported transactional sex in the previous 3 months (aRR = 1.88, 95 % CI 1.10–3.23). While having a wife or family member as a main source of income, having no documentation, migrating to find better education or to escape political persecution, and condom at last sex were all significantly associated with HIV serostatus in the crude analysis, none of these factors remained significant after adjusting for country of origin.

Table 4.

Crude and adjusted prevalence ratios for HIV serostatus by sociodemographic characteristics, migration factors, and HIV risk factors among male foreign migrants in Cape Town, South Africa 2013

| HIV positive | HIV negative | Crude prevalence ratio | Prevalence ratio adjusted for country of origin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| RDS adj % | 95 % CI | RDS adj % | 95 % CI | URRa | 95 % CI | Z statistic | P value | ARRb | 95 % CI | Z statistic | P value | |

| Age | ||||||||||||

| 16–24 | 14.3 | 0.0–37.6 | 29.9 | 22.2–36.3 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 25–29 | 24.8 | 13.3–45.2 | 29.4 | 23.3–35.8 | 4.33 | 1.29–14.42 | 2.38 | 0.017 | 1.23 | 0.47–3.19 | 0.42 | 0.677 |

| 30–34 | 19.4 | 8.3–37.1 | 22.1 | 18.4–58.2 | 3.15 | 0.90–11.03 | 1.79 | 0.073 | 1.25 | 0.46–3.39 | 0.43 | 0.666 |

| 35–54 | 41.5 | 18.4–58.2 | 18.6 | 12.7–24.4 | 5.66 | 1.71–18.81 | 2.83 | 0.005 | 4.06 | 1.73–9.54 | 3.22 | 0.001 |

| Education status | ||||||||||||

| Primary school or less | 22.1 | 10.1–44.1 | 35.9 | 27.8–43.2 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Some high school | 15.2 | 4.6–30.9 | 20.8 | 15.7–27.3 | 1.41 | 0.61–3.29 | 0.80 | 0.423 | 1.20 | 0.47–3.09 | 0.39 | 0.700 |

| Completed high school | 62.7 | 37.9–77.7 | 43.3 | 35.7–51.7 | 1.68 | 0.86–3.29 | 1.52 | 0.128 | 2.38 | 1.12–5.06 | 2.25 | 0.025 |

| Main source of income | ||||||||||||

| None | 15.6 | 11.6–20.4 | 16.8 | 12.2–21.5 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Wife/family members | 28.4 | 10.0–46.5 | 17.2 | 12.2–22.4 | 3.55 | 1.04–12.13 | 2.01 | 0.044 | 2.07 | 0.87–4.91 | 1.65 | 0.099 |

| Paid work/employment | 32.7 | 18.6–53.7 | 35.8 | 29.3–43.1 | 2.77 | 0.84–9.15 | 1.67 | 0.095 | 0.90 | 0.36–2.26 | −0.23 | 0.817 |

| Own business | 18.5 | 7.0–35.4 | 23.1 | 17.5–29.0 | 2.37 | 0.69–8.16 | 1.37 | 0.171 | 1.06 | 0.39–2.87 | 0.11 | 0.911 |

| Shady deals/transactional sex/other | 4.8 | 0.0–5.2 | 7.1 | 3.8–12.7 | 2.53 | 0.54–11.89 | 1.17 | 0.241 | 1.14 | 0.33–3.94 | 0.22 | 0.826 |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Married, living with wife | 19.5 | 6.0–38.8 | 23.0 | 17.0–28.2 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Married, not living with wife | 22.7 | 6.5–37.9 | 22.1 | 16.2–27.9 | 1.98 | 0.80–4.91 | 1.46 | 0.143 | 1.58 | 0.65–3.85 | 1.01 | 0.311 |

| Unmarried, living with sexual partner | 21.0 | 7.0–35.5 | 15.2 | 11.0–21.0 | 2.67 | 1.13–6.29 | 2.24 | 0.025 | 2.97 | 1.74–9.05 | 3.28 | 0.001 |

| Unmarried, not living with sexual partner | 36.8 | 18.2–60.4 | 39.6 | 33.5–46.9 | 1.25 | 0.52–2.98 | 0.50 | 0.618 | 1.79 | 0.79–4.07 | 1.39 | 0.164 |

| Housing type | ||||||||||||

| Shack/backyard dwelling | 49.0 | 29.2–71.2 | 49.1 | 42.9–56.8 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Brick house/apartment and other types | 51.0 | 278–71.2 | 50.9 | 43.2–57.2 | 0.77 | 0.45–1.32 | −0.94 | 0.345 | 1.19 | 0.68–2.11 | 0.61 | 0.541 |

| Poverty status | ||||||||||||

| Enough money for basics and/or more | 32.9 | 16.6–54.2 | 53.0 | 45.5–84.3 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Not enough money for food | 67.1 | 45.5–84.3 | 47.0 | 41.1–54.5 | 1.77 | 1.02–3.08 | 2.03 | 0.043 | 1.86 | 1.04–3.33 | 2.10 | 0.036 |

| Country of origin | ||||||||||||

| Congo/DRC | 4.5 | 0.0–13.2 | 30.9 | 17.2–46.8 | Ref | |||||||

| Zimbabwe | 55.4 | 27.5–73.8 | 25.9 | 14.5–40.1 | 12.75 | 2.35–69.16 | 3.73 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Malawi | 12.5 | 0.0–30.2 | 3.3 | 0.0–10.2 | 16.59 | 2.88–95.47 | 3.69 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Tanzania | 13.5 | 3.2–29.2 | 29.5 | 17.3–43.1 | 3.14 | 0.50–19.67 | 1.49 | 0.136 | ||||

| Other | 14.2 | 2.2–39.5 | 10.4 | 4.9–13.7 | 8.15 | 1.32–50.43 | 2.61 | 0.009 | ||||

| Length of time in South Africa | ||||||||||||

| 12 months or less | 21.4 | 3.0–41.2 | 25.5 | 18.9–32.7 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| 13 months–5 years | 41.1 | 25.5–66.1 | 52.1 | 45.1–59.4 | 1.06 | 0.47–2.40 | 0.14 | 0.891 | 1.34 | 0.56–3.21 | 0.62 | 0.534 |

| >5 years | 37.4 | 18.6–55.0 | 22.4 | 16.4–28.5 | 1.39 | 0.61–3.19 | 0.79 | 0.432 | 2.34 | 0.97–5.61 | 1.86 | 0.062 |

| Documentation | ||||||||||||

| Asylum/Refugee/Visa/Other | 68.2 | 54.7–88.4 | 79.2 | 73.1–84.9 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| No papers | 31.8 | 11.2–45.1 | 20.8 | 14.9–26.9 | 2.18 | 1.23–3.84 | 2.68 | 0.007 | 1.40 | 0.80–2.43 | 1.18 | 0.238 |

| Main push/pull factor | ||||||||||||

| To find work | 62.3 | 46.1–84.8 | 44.2 | 36.9–51.7 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| To get a better education | 8.9 | 5.0–11.9 | 18.1 | 12.9–24.4 | 0.33 | 0.12–0.92 | −2.12 | 0.034 | 0.65 | 0.24–1.75 | −0.86 | 0.392 |

| Escaping political persecution | 16.9 | 1.4–32.4 | 15.0 | 10.2–19.1 | 0.39 | 0.18–0.82 | −2.48 | 0.013 | 1.41 | 0.66–3.01 | 0.90 | 0.369 |

| Unhappy home life/other | 11.9 | 4.2–24.5 | 22.8 | 17.6–28.9 | 0.49 | 0.21–1.13 | −1.67 | 0.096 | 0.57 | 0.23–1.45 | −1.17 | 0.242 |

| Alcohol use frequency in the past 12 months | ||||||||||||

| Never | 36.3 | 16.8–53.0 | 49.9 | 43.4–57.2 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| A few times a month or less | 33.6 | 16.0–50.9 | 35.0 | 28.2–41.0 | 1.34 | 0.69–2.58 | 0.87 | 0.384 | 1.19 | 0.61–2.31 | 0.50 | 0.620 |

| Weekly | 30.1 | 12.7–55.0 | 15.2 | 10.0–20.7 | 2.77 | 1.43–5.36 | 3.02 | 0.003 | 1.90 | 1.01–3.69 | 1.98 | 0.049 |

| STI symptoms in past 3 months | ||||||||||||

| No | 79.9 | 62.2–91.9 | 80.6 | 74.3–85.9 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 20.1 | 7.9–39.7 | 19.4 | 14.2–26.1 | 1.26 | 0.63–2.39 | 0.70 | 0.482 | 0.64 | 0.32–1.28 | −1.27 | 0.203 |

| Number of sexual partners in past 3 months | ||||||||||||

| None | 26.6 | 11.4–50.0 | 29.9 | 23.3–38.0 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| One | 40.4 | 17.4–59.0 | 34.5 | 30.3–42.8 | 1.13 | 0.54–2.40 | 0.33 | 0.744 | 1.46 | 0.74–2.89 | 1.08 | 0.280 |

| Two | 9.9 | 1.1–14.7 | 17.9 | 11.7–22.1 | 1.32 | 0.53–3.33 | 0.59 | 0.552 | 0.86 | 0.32–2.30 | −0.30 | 0.764 |

| Three or more | 23.1 | 10.5–45.4 | 17.7 | 12.1–21.5 | 1.79 | 0.83–3.86 | 1.48 | 0.139 | 1.48 | 0.65–3.35 | 0.94 | 0.349 |

| Anal sex with a man in the past 6 months | ||||||||||||

| None | 96.8 | 90.2–100 | 93.4 | 88.7–97.0 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Any | 3.2 | 0.0–10.0 | 6.6 | 3.2–11.4 | 1.11 | 0.37–3.37 | 0.19 | 0.852 | 0.34 | 0.07–1.72 | −1.31 | 0.191 |

| Condom use at last sex in past 3 months | ||||||||||||

| No | 12.7 | 0.0–21.3 | 28.0 | 21.2–36.1 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Yes | 87.3 | 79.4–100 | 72.0 | 64.0–79.0 | 2.35 | 1.01–5.52 | 1.99 | 0.049 | 1.66 | 0.74–3.70 | 1.73 | 0.217 |

| Condom use frequency in the past 3 months | ||||||||||||

| Inconsistent | 52.2 | 25.1–81.5 | 45.8 | 37.9–58.0 | Ref | Ref | ||||||

| Always | 47.8 | 19.5–73.6 | 54.2 | 42.0–61.9 | 0.83 | 0.45–1.54 | −0.58 | 0.561 | 1.19 | 0.63–2.23 | 0.53 | 0.598 |

| Transactional sex in the past 3 months | ||||||||||||

| None | 55.2 | 35.6–76.9 | 73.7 | 67.7–79.1 | Ref | |||||||

| Any | 44.8 | 22.3–63.8 | 26.3 | 20.8–32.1 | 2.17 | 1.27–3.70 | 2.82 | 0.005 | 1.88 | 1.10–3.23 | 2.29 | 0.022 |

Unadjusted risk ratio

Adjusted risk ratio, adjusted for country of origin

Discussion

Sampling methods among hidden populations where no sampling frame exists are limited; household surveys can be prohibitively expensive among hidden populations, and snowball sampling often produces biased results. This study provides evidence for the use of RDS as a valid method of recruitment for foreign migrant men in Cape Town, South Africa. Several referral chains reached 13 waves indicating that our study reached deeper into the networks we sampled and accessed more isolated individuals. Although half of the seeds were unproductive, two of these were recruited in the last week of the study and did not have adequate time to successfully recruit peers. With the exception of country of origin, all study variables reached equilibrium between one and five waves of recruitment, meaning that bias from the non-random selection of seeds was theoretically eliminated, and homophily indices indicated there was little preference for either in- or out-group recruiting. However, the fact that the homophily indices for country of origin showed clear recruitment patterns suggest that the non-preferential recruitment assumption of RDS was violated [27, 28]. The tendency of individuals to recruit peers from the same country of origin was not surprising; the same phenomenon was reported from a similar study of female, foreign migrants in Cape Town in 2012 [29]. However, we did observe bridges across country of origin within recruitment chains, indicating that there is a linked underlying network of migrant men in Cape Town.

Results from this study suggest that transnational migrant men in Cape Town are experiencing elevated rates of several known HIV-related socio-demographic and behavioral risk factors as compared to general populations of men in South Africa. Not having enough money for food and being unemployed were both more common among the study’s target population than a general population of men in Cape Town [23, 30]. These results may be partially due to the difficulties transnational migrants face accessing employment based on their migrant status. Several behavioral risks factors, including being consumers of transactional sex, having multiple sexual partners in past 3 months, and reporting recent STI symptoms, were more prevalent among transnational migrant men than among South African men [17, 31, 32]. Finally, while previous research suggests that the study population does not differ dramatically from the general population of South African men in rates of condom use at last sex [33], there is some evidence that inconsistent condom use was more common among the study population [34].

Despite these risk factors, the overall HIV prevalence of 8.7 % documented in this study is lower than the countrywide estimated 2012 prevalence rate for South African men aged 15–49 (14.5 %) [32]. However, there was substantial variation in HIV prevalence by country of origin. Due to this study’s inability to reach equilibrium on country of origin, these estimates are likely unstable and should be considered with caution. However, it should be noted that this variation is reflective of prevalence rates in sending communities. The 2013 UNAIDS country-level estimates for adults aged 15–49 revealed HIV prevalence rates of 2.5 % for Congo, 1.1 % for DRC, 15.0 % for Zimbabwe, 10.3 % for Malawi, and 5.0 % for Tanzania [35], all of which are very similar to the country-of-origin-specific prevalence rates documented among migrant men in this study. Further, length of time in South Africa was not significantly associated with HIV serostatus in the crude or adjusted analysis. These findings may be an indication that HIV transmission in this study population occurred prior to men’s migration to South Africa. The findings could also be a reflection of within-group preferences for sexual partners after settling in South Africa; if migrant men tend to exclusively engage in sexual activity with individuals from their same country of origin, it is reasonable to assume that these micro-communities within Cape Town would reflect similar HIV prevalence rates as the migrants’ communities of origin.

Two migration-related factors (documentation status and push/pull factor) were associated with HIV status in the crude analysis. However, significant relationships were not maintained after adjusting for county of origin. It is likely that individuals who originated from the same countries experience comparable conditions in the pre-migration phase, which caused them to have similar motivations for migrating and similar access to legal documentation after arriving in South Africa. Therefore, the significant relationships in the crude analysis may instead be a more accurate reflection of the variation in HIV status by country of origin. Several of the study socio-demographic and behavioral risk factors, including poverty status, alcohol use, and transactional sex, were positively associated with current HIV serostatus among the study’s target population. These results are consistent with findings from previous studies of HIV-related risk factors throughout sub-Saharan Africa [32, 36–41].

This study has several limitations. The results of this study confirm similar limitations found from its previous companion study among cross-border migrant women [29], namely the clear within-country recruitment bias. (The current study replicated the procedures used in the previous companion study on foreign migrant women prior to our awareness of its shortcomings.) As a result, the HIV estimates by country of origin are unstable and unreliable and should be considered in this light. We again recommend that future research in Cape Town be conducted among foreign migrants by country of origin. We used RDS-generated individualized weights in the regression analyses that adjusted for country of origin. However, there is debate in the literature as to whether this is in fact an appropriate method, as there is no consensus on whether RDS data can be appropriately weighted for multivariable regression models. Future statistical research is needed to advance use of RDS data in regression analyses. The cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow for causal conclusions to be made about the relationship between risk factors and HIV status, only associations. While steps were taken to increase the likelihood of accurate self-report of sensitive behaviors, it is likely that this study underestimates the true prevalence of certain risk behaviors. Further, the study results can only be generalized to foreign migrant men living in and around Cape Town; there are large populations of migrants in areas of the country closer to national borders, including in Johannesburg and farming regions in the north. Migrants in these areas may be more vulnerable as they are more likely to have recently arrived or are unable to continue the journey to the southern-most area of the country.

Conclusions

RDS is an appropriate method for conducting future research among male foreign migrants in Cape Town, although this future research should be conducted separately among men from the same countries of origin. This future research would also help to clarify whether the large variation in HIV prevalence by country of origin is a true reflection of the underlying HIV epidemic among male foreign migrants in Cape Town or is, instead, an artifact of the bias introduced into this study by the within-country recruitment preference.

In order to design and implement effective interventions targeted to transnational migrant men in South Africa, future research is need to better understand the timing of HIV transmission during the migration process. If migrant men are at the highest risk of HIV acquisition in their home countries due to pre-migration phase conditions, service providers in South Africa should develop programs to test newly arrived migrants as soon as possible and rapidly link them to care. However, this study’s finding that migrant men in Cape Town reported higher rates of several behavioral risk factors as compared to general populations of South African men suggests that targeted HIV prevention interventions are also needed after migrant men have arrived in South Africa. Results from this study suggest that consumers of transactional sex or frequent alcohol users may be most vulnerable to future HIV infections, and targeting interventions towards these specific sub-groups of male migrants may be most effective. Further, if the wide variation in HIV-prevalence by country of origin is a function of a lack of out-country sexual mixing after settling in Cape Town, then future research should investigate differences in sexual risk practices within migrant country of origin sub-groups before designing tailored prevention efforts. Finally, biological and behavioral HIV surveillance among migrants should be conducted in other areas of South Africa in order to determine whether the results of this study characterize risk for HIV among all foreign migrant men in the country or only the individuals who were able to travel to Cape Town.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, under the terms of Cooperative Agreement Number 5U2GPS001137-4. The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest Margaret Giorgio, Loraine Townsend, Yanga Zembe, Mireille Cheyip, Rebecca Carter, and Cathy Mathews declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- 1.Weine SM, Kashuba AB. Labor migration and HIV risk: a systematic review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(6):1605–21. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0183-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolffers I, Verghis S, Marin M. Migration, human rights, and health. Lancet. 2003;362(9400):2019–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15026-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tanga PT, Tangwe MN. Interplay between economic empowerment and sexual behaviour and practices of migrant workers within the context of HIV and AIDS in the Lesotho textile industry. SAHARA J. 2014;11(1):187–201. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2014.976250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hankins CA, Friedman SR, Zafar T, Strathdee SA. Transmission and prevention of HIV and sexually transmitted infections in war settings: implications for current and future armed conflicts. AIDS. 2002;16(17):2245–52. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211220-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mock NB, Duale S, Brown LF, et al. Conflict and HIV: a framework for risk assessment to prevent HIV in conflict-affected settings in Africa. Emerg Themes Epidemiol. 2004;29(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1742-7622-1-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sudhinaraset M, Astone N, Blum RW. Migration and unprotected sex in Shanghai, China: correlates of condom use and contraceptive consistency across migrant and nonmigrant youth. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(Suppl 3):S68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saggurti N, Nair S, Malviya A, Decker M, Silverman J, Raj A. Male migration/mobility and HIV among married couples: cross-sectional analysis of nationally representative data from India. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(6):1649–58. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0022-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amirkhanian Y, Kuznetsova A, Kelly J, et al. Male labor migrants in Russia: HIV risk behavior levels, contextual factors, and prevention needs. J Immigr Minor Health. 2011;13(5):919–28. doi: 10.1007/s10903-010-9376-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taran PA. Human rights of migrants: challenges of the new decade. Int Migr. 2001;38(6):7–51. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quesada J, Hart L, Bourgois P. Structural vulnerability and health: latino migrant laborers in the United States. Med Anthropol. 2011;30(4):339–62. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2011.576725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.UNHCR. [Accessed 1 December 2015];2015 UNHCR country operations profile–South Africa. 2015 http://www.unhcr.org/pages/49e485aa6.html.

- 12.UNDESA. Trends in International Migrant Stock: The 2008 Revision. New York: USA: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.UNAIDS. [Accessed 1 Dec, 2015];South Africa: HIV and AIDS Estimates. 2014 http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/southafrica/

- 14.SANAC. National strategic plan for HIV and AIDS, STIs and TB, 2012–2016. Pretoria: South Africa: South Africa National AIDS Council; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zuma K, Lurie MN, Williams BG, Mkaya-Mwamburi D, Garnett GP, Sturm AW. Risk factors of sexually transmitted infections among migrant and non-migrant sexual partnerships from rural South Africa. Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133(3):421–8. doi: 10.1017/s0950268804003607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sonnenberg P, Murray J, Glynn JR, Shearer S, Kambashi B, Godfrey-Faussett P. HIV-1 and recurrence, relapse, and reinfection of tuberculosis after cure: a cohort study in South African mineworkers. Lancet. 2001;358(9294):1687–93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06712-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lurie MN, Williams BG, Zuma K, et al. The impact of migration on HIV-1 transmission in South Africa: a study of migrant and nonmi-grant men and their partners. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30(2):149–56. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200302000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baltazar CS, Horth R, Inguane C, et al. HIV prevalence and risk behaviors among Mozambicans working in South African mines. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(Suppl 1):S59–67. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0941-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston L, Whitehead S, Simic-Lawson M, Kendall C. Formative research to optimize respondent-driven sampling surveys among hard-to-reach populations in HIV behavioral and biological surveillance: lessons learned from four case studies. AIDS Care. 2010;22(6):784–92. doi: 10.1080/09540120903373557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heckathorn D. Respondent-driven sampling: a new approach to the study of hidden populations. Soc Probl. 1997;44(2):174–99. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salganik M, Heckathorn D. Sampling and estimation of hidden populations using respondent driven sampling. Sociol Methodol. 2004;34(1):193–240. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnston L, Sabin K. Sampling hard-to-reach populations with respondent driven sampling. Methodol Innovat Online. 2010;5(2):38–48. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Townsend L, Zembe Y, Mathews C. HIV prevalence and risk behaviours from three consecutive surveys among men who have multiple female sexual partners in Cape Town. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(7):2367–75. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnston L, Chen YH, Silva-Santisteban A, Raymond HF. An empirical examination of respondent driven sampling design effects among HIV risk groups from studies conducted around the world. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):2202–10. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0394-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wejnert C, Pham H, Krishna N, Le B, DiNenno E. Estimating design effect and calculating sample size for respondent-driven sampling studies of injection drug users in the United States. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(4):797–806. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0147-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnston L, Luthra R. Analyzing data in respondent driven sampling. In: Tyldum G, Johnston L, editors. Applying respondent driven sampling to migrant populations: lessons from the field. London: Palgrave; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamanis TJ, Merli MG, Neely WW, et al. An empirical analysis of the impact of recruitment patterns on RDS estimates among a socially ordered population of female sex workers in China. Sociol Methods Res. 2013;42(3):1–34. doi: 10.1177/0049124113494576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heckathorn D. Extensions of respondent-driven sampling: analyzing continuous variables and controlling for differential recruitment. Sociol Methodol. 2007;37(1):151–207. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Townsend L, Giorgio M, Zembe Y, Cheyip M, Mathews C. HIV prevalence and risk behaviours among foreign migrant women residing in Cape Town South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(10):2020–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0784-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Townsend L, Jewkes R, Mathews C, et al. HIV risk behaviours and their relationship to intimate partner violence (IPV) among men who have multiple female sexual partners in Cape Town South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(1):132–41. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9680-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dunkle KL, Jewkes R, Nduna M, et al. Transactional sex and economic exchange with partners among young South African men in the rural Eastern Cape: prevalence, predictors, and associations with gender-based violence. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(6):1235–48. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, et al. South African national HIV prevalence, incidence and behaviour survey, 2012. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi L, Zuma K, Jooste S. South African national HIV prevalence incidence behaviour and communication survey 2008: a turning tide among teenagers? Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sikkema KJ, Watt MH, Meade CS, Ranby KW, Kalichman SC, Skinner D, et al. Mental Health and HIV sexual risk behavior among patrons of alcohol serving venues in Cape Town, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;57(3):230–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182167e7a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.UNAIDS. [Accessed 1 Dec 2015];HIV and AIDS Estimates. 2013 http://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/

- 36.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, Cain D, Jooste S. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci. 2007;8(2):141–51. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Townsend L, Rosenthal SR, Parry CDH, Zembe Y, Mathews C, Flisher A. Associations between alcohol misuse and risks for HIV infection among men who have multiple female sexual partners in Cape Town South Africa. AIDS Care. 2010;22(12):1544–54. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2010.482128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Townsend L, Zembe Y, Mathews C, Mason-Jones AJ. Estimating HIV prevalence and HIV-related risk behaviors among heterosexual women who have multiple sex partners using respondent-driven sampling in a high-risk community in South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;62(4):457–64. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182816990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mah TL, Maughan-Brown B. Social and cultural contexts of concurrency in a township in Cape Town South Africa. Cult Health Sex. 2013;15(2):135–47. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.745951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Choudhry V, Ambresin AE, Nyakato VN, Agardh A. Transactional sex and HIV risks–evidence from a cross-sectional national survey among young people in Uganda. Glob Health Action. 2015;8:27249. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.27249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cote AM, Sobela F, Dzokoto A, et al. Transactional sex is the driving force in the dynamics of HIV in Accra Ghana. AIDS. 2004;18(6):917–25. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200404090-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]