Abstract

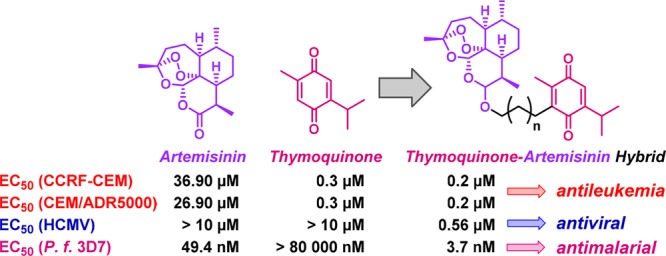

A series of hybrid compounds based on the natural products artemisinin and thymoquinone was synthesized and investigated for their biological activity against the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 strain, human cytomegalovirus (HCMV), and two leukemia cell lines (drug-sensitive CCRF-CEM and multidrug-resistant subline CEM/ADR5000). An unprecedented one-pot method of selective formation of C-10α-acetate 14 starting from a 1:1 mixture of C-10α- to C-10β-dihydroartemisinin was developed. The key step of this facile method is a mild decarboxylative activation of malonic acid mediated by DCC/DMAP. Ether-linked thymoquinone–artemisinin hybrids 6a/b stood out as the most active compounds in all categories, while showing no toxic side effects toward healthy human foreskin fibroblasts and thus being selective. They exhibited EC50 values of 0.2 μM against the doxorubicin-sensitive as well as the multidrug-resistant leukemia cells and therefore can be regarded as superior to doxorubicin. Moreover, they showed to be five times more active than the standard drug ganciclovir and nearly eight times more active than artesunic acid against HCMV. In addition, hybrids 6a/b possessed excellent antimalarial activity (EC50 = 5.9/3.7 nM), which was better than that of artesunic acid (EC50 = 8.2 nM) and chloroquine (EC50 = 9.8 nM). Overall, most of the presented thymoquinone–artemisinin-based hybrids exhibit an excellent and broad variety of biological activities (anticancer, antimalarial, and antiviral) combined with a low toxicity/high selectivity profile.

Keywords: Artemisinin, thymoquinone, natural product hybrid, antimalarial activity, antiviral activity, anticancer activity

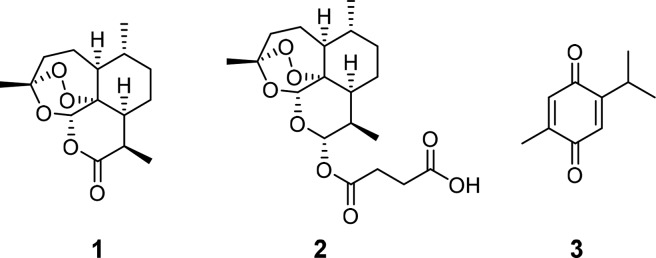

Over the past decade, the hybridization of natural products turned out to be a highly fruitful strategy for medicinal chemistry and drug design.1−3 Not only does it keep synthetic effort at a minimum and thus is relatively time and cost saving, but it also can improve upon pharmacological properties of the parent compounds such as increased biological efficacy, reduced undesired side effects, a modified selectivity profile (lower toxicity), better bioavailability, and addition of completely new biological features that were absent in the parent compounds.1,3−5 Artesmisinin (1), an enantiomerically pure sesquiterpene containing a 1,2,4-trioxane ring, which was extracted from the Chinese medicinal plant Artemisia annua L. in 1972 by Youyou Tu (Nobel Prize 2015),6 and thymoquinone (3) (Figure 1), a naturally occurring phytochemical compound, which is the main constituent of the volatile oil of Nigella sativa (black seed) and was first isolated in 1963 by El-Dakhakhany,7 both exhibit great pharmacological potential as anticancer agents.8,9 In addition, artemisinin also possesses great antimalarial and antiviral properties just like its semisynthetic derivative artesunic acid (2) (Figure 1).10−12

Figure 1.

Structures of artemisinin (1), artesunic acid (2), and thymoquinone (3).

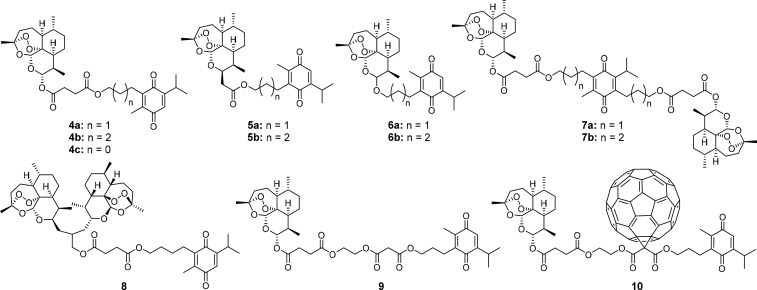

For that reason and also motivated by our previous studies applying the hybridization concept using artemisinin derivatives,13−15 we recently synthesized and published seven novel thymoquinone–artemisinin hybrids 4–6 (Figure 2), which were investigated for their anticancer potential, and indeed, some of those compounds were highly active and selective toward colon cancer outperforming their parent compounds.16 Following this study, we herein present the synthesis of five additional thymoquinone–artemisinin hybrids 7–10 (Figure 2) and investigate for the first time all 12 compounds against leukemia, malaria, and human cytomegalovirus (HCMV).

Figure 2.

Hybrids 4–10 applied for biological tests against CCRF-CEM, CEM/ADR5000 cells, HCMV, and P. falciparum 3D7.

Results and Discussion

Chemistry

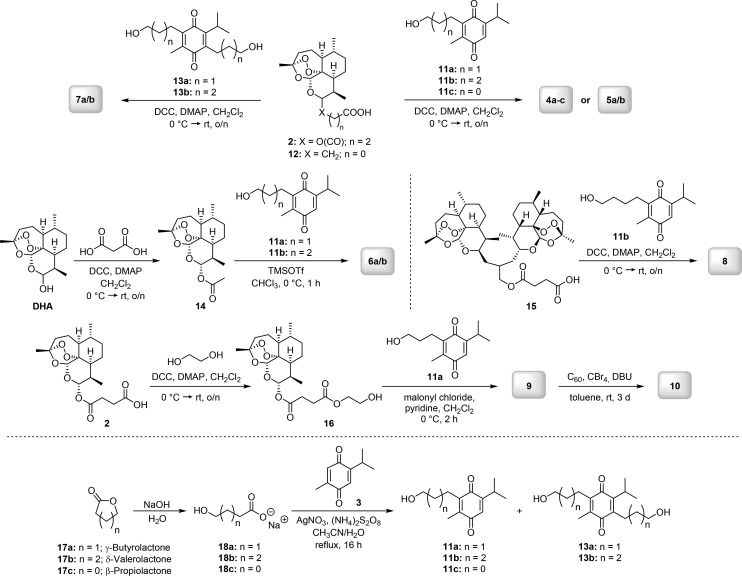

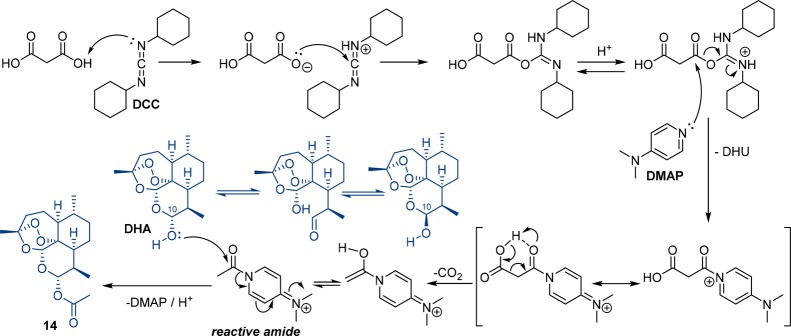

The synthesis of hybrids 4, 5, and 6 was already described in our previous study (where the compounds were studied against colon cancer),16 and the synthetic results are summarized in Scheme 1. Notably, during the course of the current study we found an unprecedented method of selective formation of C-10α-acetate 14 (precursor for the synthesis of ether-linked hybrids 6a/b) starting from a 1:1 mixture of C-10α- to C-10β-dihydroartemisinin (DHA). Instead of using a standard acetylation procedure with acetic anhydride, pyridine, and DMAP,17 we performed the reaction of DHA with malonic acid, DCC, and DMAP and obtained the desired product 14 in 85% yield (Scheme 1). The key step of this novel method is a mild decarboxylative activation of malonic acid (Scheme 2). Notably, decarboxylative activation of malonic acid derivatives usually proceed under harsh thermal conditions18,19 or by using copper-catalyzed19 and enzyme-catalyzed20 methods. Routes toward decarboxylative activation of malonic acid under mild conditions are still few: one known method uses N,N′-carbonyldiimidazole (CDI)21 and the second one applies 1-(methylsulfonyl)-1H-benzo[d][1,2,3]triazole in combination with Et3N.22 The mechanism of the developed reaction might be similar to the one proposed in literature for the decarboxylative acylation of O-,N-nucleophiles using 2,2-disubstituted malonic acids and 1-(methylsulfonyl)-1H-benzo[d][1,2,3]triazole.22 The authors suggested that upon reaction of malonic acid with benzotriazole derivative in the presence of Et3N an unstable intermediate forms, which after release of CO2 can be attacked by a corresponding nucleophile.22 In our case, the monocarbonyl activation of malonic acid is mediated by DCC/DMAP, while DHA represents the nucleophile and can react with reactive amide formed after the decarboxylation step (Scheme 2). The formation of the 10α-isomer is favored, most probably because the C-9 methyl group acts as steric hindrance, which makes a reaction of 10β-DHA with activated malonic acid less possible. The high yield (85%) for C-10α-acetate 14 can be explained by an C-10β → C-10α interconversion, presumably through an aldehyde–alcohol intermediate in solution (Scheme 2). The advantage of our novel decarboxylative acetylation is that solely the C-10α-isomer is generated, whereas with the literature known method, always a 1:1 mixture of 10α- to 10β-isomer is formed.13 This is remarkable because DHA itself was applied in the form of a 1:1 mixture of 10α- to 10β-DHA. This kind of chiral enrichment under mild conditions might render itself as highly useful for synthesis of different enantiomerically pure dihydroartemisinin derivatives, as the reaction should also work in the same way with 2,2-disubstituted malonic acids.

Scheme 1. Synthesis Route for Hybrids 4–10 and Thymoquinone Precursors 11 and 13.

Scheme 2. Proposed Mechanism for the One-Pot Acetylation of Dihydroartemisinin (DHA) via Monocarbonyl Activation of Malonic Acid with DCC/DMAP Followed by Decarboxylation and Nucleophilic Substitution with DMAP as a Leaving Group.

The preparation of artesunic acid based hybrids 7a/b, in which TQ acts as a linker, was achieved in 72%/65% yield by performing a Steglich esterification reaction between two molecules of artesunic acid and one molecule of TQ diol 13 (Scheme 1). DCC and DMAP were utilized as coupling agents. The diol 13 was synthesized by applying the same method as used for the monohydric alcohols of TQ 11 (Scheme 1): TQ and different sodium hydroxyl carboxylate salts 18 (which were obtained in quantitative yield by simple ester hydrolysis of commercially available lactones 17) were treated with (NH4)2S2O8 and catalytic amounts of AgNO3 in a mixture of water and acetonitrile. This procedure was already reported in the literature in the context of synthesis of other TQ derivatives.23 In order to get the diol 13 in reasonable amounts, at least 2.0 equiv of the carboxylate salts have to be applied. To be able to compare the effect of the placement of two artemisinin moieties around the TQ subunit on biological activity, we also synthesized the artemisinin-derived dimer-TQ hybrid 8, where both artemisinin subunits are connected to only one side of TQ. Again, Steglich esterification using TQ alcohol 11b and artemisinin-derived dimer carboxylic acid 15 applying DCC and DMAP as reagents afforded the desired product in 73% yield. Artemisinin-derived dimer 15 was prepared according to a published protocol and was chosen as starting material24 because its core-structure was found to be highly beneficial for antimalarial and anticancer activity, leading to the synthesis and extensive studies of a series of similar compounds, some of which turned out to belong to the most active compounds among artemisinin-derived dimers presented so far in the literature.25 This is supported by the positive results we were able to obtain from our own research, when applying a similar artemisinin-derived dimer for the synthesis of trimers, which showed excellent anticytomegaloviral and antileukemia efficacies.13

In order to investigate the radical scavenging effect of fullerene on thymoquinone–artemisinin hybrids, a Bingel–Hirsch reaction was performed between TQ–artesunic acid hybrid 9, which contains a malonyl moiety, and fullerene (C60), resulting in the desired product 10 with a yield of 30% after 3 days. DBU was applied as base, CBr4 as reagent, and toluene as solvent. The starting compound 9, necessary for this procedure, was obtained in 30% yield by reaction of malonyl chloride, TQ alcohol 11a, and artesunic acid derived alcohol 16, which in turn was prepared by Steglich esterification of artesunic acid and ethylene glycol in 91% yield. The malonylation reaction was promoted by pyridine as base and was conducted in CH2Cl2 as solvent.

Biological Activity of the Hybrids

Cytotoxicity toward Sensitive CCRF-CEM and Multidrug-Resistant CEM/ADR500 Leukemia Cells

The cytotoxic potential against wild-type CCRF-CEM and multidrug-resistant P-glycoprotein overexpressing CEM/ADR5000 human leukemia cells was investigated for hybrids 4 and 6–10 as well as their parent compounds artesunic acid/artemisinin and thymoquinone (Table 1). Doxorubicin, a clinically used drug, served as a fourth reference compound in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the hybrids toward the resistant cells. All hybrids except hybrid 10 show a moderate to good antileukemic effect against both the doxorubicin-sensitive and doxorubicin-resistant cell lines with EC50 values in the micromolar to submicromolar range (EC50(CCRF-CEM) = 0.0027–6.071 μM; EC50(CEM/ADR5000) = 0.2–5.663 μM), which in all cases is better compared to that of artemisinin (EC50(CCRF-CEM) = 36.90 μM; EC50(CEM/ADR5000) = 26.90 μM). The best overall performance was observed for ether-linked thymoquinone–artemisinin hybrids 6a/b and artesunic acid based hybrid 7a, which showed the same high efficacy toward the doxorubicin-resistant (EC50(CCRF-CEM) = 0.2/0.3 μM) as against the doxorubicin-sensitive (EC50(CEM/ADR5000) = 0.2 μM) leukemia cells and therefore can be regarded as superior to doxorubicin because this drug already shows some loss of activity due to multidrug resistance (EC50(CCRF-CEM) = 0.009 μM; EC50(CEM/ADR5000) = 23.27 μM). Strikingly, dimer 7b, where one additional CH2 group is introduced on each side of the thymoquinone linker subunit, is approximately 30 times less active than dimer 7a. This result indicates that linker length plays a crucial role for the antileukemia activity of artemisinin dimers, where thymoquinone is applied as a spacer molecule. This effect was not observed for the compounds containing only one artemisinin subunit. No matter how long the spacer between the two pharmacophores in hybrids 4 or 6, the EC50 values stay almost the same. Interestingly, in our previously published results, the linker length also was important for the anticancer activity toward colon cancer cells of thymoquinone–artemisinin hybrids with only one artemisinin moiety.16 Thus, the influence of linker length seems to be specific to certain cell lines or cancer types, which in turn may suggest that for each cancer cell line different mechanisms or targets may be involved. As expected, hybrid 10 containing a fullerene moiety was not active at all, unlike its precursor 9, which clearly showed a relatively strong antileukemia effect. This can be seen as another proof that the biological activity of the artemisinin moiety is mediated via radicals, as fullerene is well-known for its radical scavenging and antioxidant properties.26,27

Table 1. EC50 Values for Hybrids 4-10 and Selected Reference Compounds Tested against Sensitive Wild-Type CCRF-CEM and Multidrug Resistant P-Glycoprotein-Overexpressing CEM/ADR5000 Cells, HCMV, and P. falciparum 3D7 Parasites.

| compd | molecular weight (g/mol) | CCRF-CEM EC50 (μM) | CEM/ADR5000 EC50 (μM) | HCMV EC50 (μM) | P.f.3D7 EC50 (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| doxorubicin | 579.98 | 0.009a | 23.27a | ||

| ganciclovir | 579.98 | 2.60 ± 0.5b | |||

| chloroquine | 319.87 | 9.8 ± 2.8d | |||

| artemisinin (1) | 282.14 | 36.90 ± 6.90a | 26.90 ± 4.40a | >10b | |

| dihydroartemisinin | 284.35 | >10b | 2.4 ± 0.4d | ||

| artesunic acid (2) | 384.42 | 0.4 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 5.41 ± 0.61b | 8.2 ± 1.6 |

| TQ (3) | 164.20 | 0.3 ± 0.03 | 0.3 ± 0.01 | >10 | >80 000 |

| 4a | 588.69 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 6.54 ± 1.33 | 6.9 ± 2.5 |

| 4b | 602.72 | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 0.8 ± 0.3 | 5.36 ± 0.19 | 7.7 ± 1.5 |

| 4c | 574.67 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.83 ± 0.39 | 8.2 ± 1.2 |

| 5a | 530.66 | 0.80 ± 0.02 | 54 ± 2.2 | ||

| 5b | 544.69 | 2.12 ± 0.14 | 17.5 ± 1.4 | ||

| 6a | 502.65 | 0.2 ± 0.04 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 0.63 ± 0.02 | 5.9 ± 0.8 |

| 6b | 488.62 | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.02 | 0.56 ± 0.01 | 3.7 ± 0.8 |

| 7a | 1013.18 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.2 ± 0.04 | 0.69 ± 0.01 | 4.3 ± 1.5 |

| 7b | 1041.24 | 6.071 ± 0.247 | 5.663 ± 0.190 | ctx/ndc | 12.1 ± 0.8 |

| 8 | 925.17 | 0.0027 ± 0.001 | 7.872 ± 0.594 | ctx/ndc | 12.2 ± 1.9 |

| 9 | 718.79 | 0.08 ± 0.03 | 8.20 ± 4.43 | 1.93 ± 0.17 | 4.4 ± 1.4 |

| 10 | 1437.44 | n.a. | n.a. | >10 | ≥341e |

EC50 values for both leukemia cell lines have been previously reported for doxorubicin28 and artemisinin.14

EC50 value against HCMV has been previously reported for ganciclovir,29 artemisinin, dihydroartemisinin,15 and artesunic acid.30

Microscopically detectable cytotoxicity approximately 50% at 1 μM, no antiviral activity detectable (ctx/nd).

EC50 values have been previously reported.14

Compound 10 precipitated in the used media. Therefore, the respective EC50 could not be determined unambiguously.

In Vitro Inhibitory Activity toward HCMV in Primary Human Fibroblasts

The antiviral activity of hybrids 4–10 was determined for HCMV, strain AD169-GFP. This recombinant virus expresses the green fluorescent protein (GFP) that can be reliably utilized to quantitate viral replication (Table 1). Infection experiments were performed with cultures of primary human foreskin fibroblasts (HFFs), and measurements of antiviral activity were carried out according to a previously established protocol.31,32 Artesunic acid (2) and ganciclovir were applied as reference compounds and both exerted strong anti-HCMV activity at EC50 levels of 5.41 and 2.60 μM, respectively. The most active compounds were again ether-linked hybrids 6a/b and thymoquinone–bis-artesunic acid hybrid 7a with EC50 values of 0.63/0.56/0.69 μM, thus showing substantially higher antiviral activity in vitro than the reference drugs ganciclovir and artesunic acid. Surprisingly, the thymoquinone–bis-artemisinin hybrids 7b and 8 turned out to be partially cytotoxic toward HFFs within the analyzed range of concentrations, so that in these cases no EC50 values could be determined. Other hybrids of this series 4–6/9, i.e., those exclusively containing one artemisinin subunit, were selectively inhibitory toward HCMV without showing cytotoxic side effects, which is an important prerequisite for putative further antiviral development. Similar to the findings obtained for antileukemia activity, the fullerene-containing hybrid 10 was inactive against HCMV, while its precursor 9 showed activity.

Antiplasmodial Activity

All synthesized hybrids 4–10 were investigated in vitro for their potential antimalarial activity toward Plasmodium falciparum 3D7 and compared to their parent compounds artesunic acid (2)/dihydroartemisinin and thymoquinone (3) as well as the standard drug chloroquine (Table 1). Overall, it can be stated that all hybrids exhibit excellent antimalarial activities with EC50 values within the nanomolar range (3.7–54 nM). Compounds 4, 6, 7a, and 9 were even more active than the reference compounds artesunic acid (EC50 = 8.2 nM) and chloroquine (EC50 = 9.8 nM) with ether-linked hybrid 6b being once again the most effective one (EC50 = 3.7 nM). The relationship between antimalarial activity and linker length seems to be dependent on the type of linkage and compound type (artemisinin monomer or dimer). For example, for thymoquinone–artesunic acid hybrids 4, linker length had nearly no effect on activity, while for compounds 5, which contain a C-10 nonacetal linkage, a longer linker was able to improve antimalarial activity by a factor of 3. In contrast, for artemisinin dimers 7, a shorter linker was more beneficial. Moreover, thymoquinone–artesunic acid hybrid 9 (EC50 = 4.4 nM) again lost its activity, when fullerene was attached to the malonyl moiety forming hybrid 10 (EC50 ≥ 341 nM).

Conclusions

In conclusion, we were able to expand upon our previously published results of thymoquinone–artemisinin-based hybrids 4–6 by synthesizing five additional ones (7–10) and investigating all hybrids for the first time for their in vitro biological activity against malaria parasites (P. falciparum 3D7), two leukemia cell lines (CCRF-CEM and CEM/ADR5000), and HCMV. During the course of our study, we developed an unprecedented one-pot method of exclusive formation of C-10α-acetate 14 (needed as a precursor for the synthesis of ether-linked hybrids) starting from a 1:1 mixture of C-10α- to C-10β-DHA. Important steps in the mechanism of this one-pot process are (1) monocarbonyl activation of malonic acid with DCC/DMAP; (2) decarboxylation resulting in N-acetyl-4-(dimethylamino)pyridine salt; and (3) nucleophilic substitution by DHA (DMAP serves as a leaving group, Scheme 2).

Among tested hybrids 4–10, ether-linked thymoquinone–artemisinin hybrids 6a/b stood out as the most active compounds in all categories, while showing no toxic side effects toward healthy HFFs and thus being selective, which is one of the most important aspects for drug development. They exhibited an EC50 value of 0.2 μM against the doxorubicin-sensitive as well as the multidrug-resistant leukemia cells and therefore can be regarded as superior to doxorubicin. Concerning the antiviral potential, several of the compounds (e.g., hybrids 5a, 6a/b, and 7a) showed a substantially higher anti-HCMV activity than the reference drugs ganciclovir and artesunic acid. In addition, hybrids 6a/b possessed excellent antimalarial activity (EC50 = 5.9/3.7 nM), which was better than that of artesunic acid (EC50 = 8.2 nM) as well as chloroquine (EC50 = 9.8 nM) and comparable to that of dihydroartemisinin (EC50 = 2.4 nM). Another interesting finding is that when a fullerene moiety was attached to hybrid 9 the compound lost completely its biological activity. This might be another proof that the mechanism of action of artemisinin compounds is mediated via radicals. The presented results provide an insight into how linker length affects biological activity. However, no general trend could be deduced. It depends on many different factors such as the type of linkage, the compound type (artemisinin dimer or monomer) and the investigated cell lines/parasites/viruses or disease, whether linker length has an effect or not and whether a shorter or longer linker is more beneficial. In summary, it can be said that thymoquinone–artemisinin hybrids 6a/b have the potential to become drug candidates, as they exhibit an excellent and broad variety of biological activities (anticancer, antimalaria, and antiviral) combined with a low toxicity/high selectivity profile.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) by grants TS 87/16-3 and MM 1289/7-1/7-3 and from European Commission (Marie Skłodowska-Curie Innovative Training Network, H2020-MSCA-ITN-2016, project number: 722456 CORE). We also thank the Interdisciplinary Center for Molecular Materials (ICMM), the Graduate School Molecular Science (GSMS) for research support, as well as Emerging Fields Initiative (EFI) “Chemistry in Live Cells” supported by Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg for funding.

Glossary

ABBREVIATIONS

- DBU

1,8-Diazabicyclo[5.4.0]undec-7-ene

- DCC

N,N′-dicyclo-hexylcarbodiimide

- DHA

dihydroartemisinin

- DHU

1,3-dicyclohexylurea

- DMAP

4-(dimethylamino)pyridine

- HCMV

human cytomegalovirus

- HFFs

human foreskin fibroblasts

- n.a.

not active

- TMSOTf

trimethylsilyl triflate

- TQ

thymoquinone

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.7b00412.

Experimental conditions and procedures as well as spectral data for intermediates 11, 13, 14, 16, and 18 and target compounds 4–10; recorded spectra of target compounds; details of cell lines and reagents as well as cell viability assay for biological evaluation (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Dedication

This paper is dedicated to Professor Andreas Seidel-Morgenstern.

Supplementary Material

References

- Tietze L. F.; Bell H. P.; Chandrasekhar S. Natural Product Hybrids as New Leads for Drug Discovery. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 3996–4028. 10.1002/anie.200200553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muregi F. W.; Ishih A. Next-Generation Antimalarial Drugs: Hybrid Molecules as a New Strategy in Drug Design. Drug Dev. Res. 2010, 71, 20–32. 10.1002/ddr.20345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda D.; Capela R.; Albuquerque I. S.; Meireles P.; Paiva I.; Nogueira F.; Amewu R.; Gut J.; Rosenthal P. J.; Oliveira R.; Mota M. M.; Moreira R.; Marti F.; Prudêncio M.; O’Neill P. M.; Lopes F. Novel Endoperoxide-Based Transmission-Blocking Antimalarials with Liver- and Blood-Schizontocidal Activities. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 108–112. 10.1021/ml4002985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viegas-Junior C.; Danuello A.; da Silva Bolzani V.; Barreiro E. J.; Fraga C. A. Molecular hybridization: a useful tool in the design of new drug prototypes. Curr. Med. Chem. 2007, 14, 1829–1852. 10.2174/092986707781058805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsogoeva S. B. Recent Progress in the Development of Synthetic Hybrids of Natural or Unnatural Bioactive Compounds for Medicinal Chemistry. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2010, 10, 773–793. 10.2174/138955710791608280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Y. The discovery of artemisinin (qinghaosu) and gifts from Chinese medicine. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1217–1220. 10.1038/nm.2471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Dakhakhny M. Studies on the chemical constitution of Egyptian Nigella Sativa L. seeds. II) The essential oil. Planta Med. 1963, 11, 465–470. 10.1055/s-0028-1100266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Efferth T. Molecular pharmacology and pharmacogenomics of artemisinin and its derivatives in cancer cells. Curr. Drug Targets 2006, 7, 407–421. 10.2174/138945006776359412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider-Stock R.; Fakhoury I. H.; Zaki A. M.; El-Baba C. O.; Gali-Muhtasib H. U. Thymoquinone: fifty years of success in the battle against cancer models. Drug Discovery Today 2014, 19, 18–30. 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Wu Y. L. An over four millennium story behind Qinghaosu (artemisinin): a fantastic antimalarial drug from a traditional Chinese herb. Curr. Med. Chem. 2003, 10, 2197–2230. 10.2174/0929867033456710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efferth T.; Romero M. R.; Wolf D. G.; Stamminger T.; Marin J. J.; Marschall M. The antiviral activities of artemisinin and artesunate. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 47, 804–811. 10.1086/591195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L. H.; Su X. Artemisinin: Discovery from the Chinese Herbal Garden. Cell 2011, 146, 855–858. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter C.; Fröhlich T.; Gruber L.; Hutterer C.; Marschall M.; Voigtländer C.; Friedrich O.; Kappes B.; Efferth T.; Tsogoeva S. B. Highly potent artemisinin-derived dimers and trimers: Synthesis and evaluation of their antimalarial, antileukemia and antiviral activities. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015, 23, 5452–5458. 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiter C.; Fröhlich T.; Zeino M.; Marschall M.; Bahsi H.; Leidenberger M.; Friedrich O.; Kappes B.; Hampel F.; Efferth T.; Tsogoeva S. B. New efficient artemisinin derived agents against human leukemia cells, human cytomegalovirus and Plasmodium falciparum: 2nd generation 1,2,4-trioxane-ferrocene hybrids. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 97, 164–172. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.04.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich T.; Reiter C.; Ibrahim M. M.; Beutel J.; Hutterer C.; Zeitträger I.; Bahsi H.; Leidenberger M.; Friedrich O.; Kappes B.; Efferth T.; Marschall M.; Tsogoeva S. B. Synthesis of Novel Hybrids of Quinazoline and Artemisinin with High Activities against Plasmodium falciparum, Human Cytomegalovirus, and Leukemia Cells. ACS Omega 2017, 2, 2422–2431. 10.1021/acsomega.7b00310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich T.; Ndreshkjana B.; Muenzner J. K.; Reiter C.; Hofmeister E.; Mederer S.; Fatfat M.; El-Baba C.; Gali-Muhtasib H.; Schneider-Stock R.; Tsogoeva S. B. Synthesis of Novel Hybrids of Thymoquinone and Artemisinin with High Activity and Selectivity Against Colon Cancer. ChemMedChem 2017, 12, 226–234. 10.1002/cmdc.201600594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höfle G.; Steglich W.; Vorbrüggen H. 4-Dialkylaminopyridines as Highly Active Acylation Catalysts. [New synthetic method (25)]. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1978, 17, 569–583. 10.1002/anie.197805691. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z.; Minhas G. S.; Wen D.; Jiang H.; Chen K.; Zimniak P.; Zheng J. Design, Synthesis, and Structure–Activity Relationships of Haloenol Lactones: Site-Directed and Isozyme-Selective Glutathione S-Transferase Inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 47, 3282–3294. 10.1021/jm0499615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchet J.; Baudoux J.; Amere M.; Lasne M.-C.; Rouden J. Asymmetric Malonic and Acetoacetic Acid Syntheses – A Century of Enantioselective Decarboxylative Protonations. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 2008, 5493–5506. 10.1002/ejoc.200800759. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okrasa K.; Levy C.; Wilding M.; Goodall M.; Baudendistel N.; Hauer B.; Leys D.; Micklefield J. Structure-Guided Directed Evolution of Alkenyl and Arylmalonate Decarboxylases. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7691–7694. 10.1002/anie.200904112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafrance D.; Bowles P.; Leeman K.; Rafka R. Mild Decarboxylative Activation of Malonic Acid Derivatives by 1,1′-Carbonyldiimidazole. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2322–2325. 10.1021/ol200575c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebedyeva I. O.; Biswas S.; Goncalves K.; Sileno S. M.; Jackson A. R.; Patel K.; Steel P. J.; Katritzky A. R. One-Pot Decarboxylative Acylation of N-, O-, S-Nucleophiles and Peptides with 2,2-Disubstituted Malonic Acids. Chem. - Eur. J. 2014, 20, 11695–11698. 10.1002/chem.201403529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breyer S.; Effenberger K.; Schobert R. Effects of thymoquinone-fatty acid conjugates on cancer cells. ChemMedChem 2009, 4, 761–8. 10.1002/cmdc.200800430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner G. H.; Paik I.-H.; Sur S.; McRiner A. J.; Borstnik K.; Xie S.; Shapiro T. A. Orally Active, Antimalarial, Anticancer, Artemisinin-Derived Trioxane Dimers with High Stability and Efficacy. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 1060–1065. 10.1021/jm020461q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich T.; Çapcı Karagöz A.; Reiter C.; Tsogoeva S. B. Artemisinin-Derived Dimers: Potent Antimalarial and Anticancer Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 7360–7388. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krusic P. J.; Wasserman E.; Keizer P. N.; Morton J. R.; Preston K. F. Radical reactions of C60. Science 1991, 254, 1183–5. 10.1126/science.254.5035.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakry R.; Vallant R. M.; Najam-ul-Haq M.; Rainer M.; Szabo Z.; Huck C. W.; Bonn G. K. Medicinal applications of fullerenes. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2007, 2, 639–649. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saab A. M.; Guerrini A.; Sacchetti G.; Maietti S.; Zeino M.; Arend J.; Gambari R.; Bernardi F.; Efferth T. Phytochemical analysis and cytotoxicity towards multidrug-resistant leukemia cells of essential oils derived from Lebanese medicinal plants. Planta Med. 2012, 78, 1927–1931. 10.1055/s-0032-1327896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Held F. E.; Guryev A. A.; Fröhlich T.; Hampel F.; Kahnt A.; Hutterer C.; Steingruber M.; Bahsi H.; von Bojničić-Kninski C.; Mattes D. S.; Foertsch T. C.; Nesterov-Mueller A.; Marschall M.; Tsogoeva S. B. Facile access to potent antiviral quinazoline heterocycles with fluorescence properties via merging metal-free domino reactions. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15071. 10.1038/ncomms15071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutterer C.; Niemann I.; Milbradt J.; Fröhlich T.; Reiter C.; Kadioglu O.; Bahsi H.; Zeitträger I.; Wagner S.; Einsiedel J.; Gmeiner P.; Vogel N.; Wandinger S.; Godl K.; Stamminger T.; Efferth T.; Tsogoeva S. B.; Marschall M. The broad-spectrum antiinfective drug artesunate interferes with the canonical nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kappaB) pathway by targeting RelA/p65. Antiviral Res. 2015, 124, 101–109. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschall M.; Freitag M.; Weiler S.; Sorg G.; Stamminger T. Recombinant Green Fluorescent Protein-Expressing Human Cytomegalovirus as a Tool for Screening Antiviral Agents. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 1588–1597. 10.1128/AAC.44.6.1588-1597.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschall M.; Niemann I.; Kosulin K.; Bootz A.; Wagner S.; Dobner T.; Herz T.; Kramer B.; Leban J.; Vitt D.; Stamminger T.; Hutterer C.; Strobl S. Assessment of drug candidates for broad-spectrum antiviral therapy targeting cellular pyrimidine biosynthesis. Antiviral Res. 2013, 100, 640–648. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.