Abstract

Background and Aims:

Breast cancer has become the most common cancer in women worldwide. Acute post-operative pain following mastectomy remains a challenge for the anaesthesiologist despite a range of treatment options available. The present study aimed to compare the post-operative analgesic efficacy of pectoral nerve (Pecs) block performed under ultrasound with our standard practice of opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for mastectomy.

Methods:

This randomised controlled study was conducted at a tertiary care teaching hospital in India, after obtaining ethical clearance. Fifty adult female patients posted for elective unilateral modified radical mastectomy were divided into two groups as follows: Group I (general anaesthesia only) and Group II (general anaesthesia plus ultrasound-guided Pecs block), each comprising 25 patients. Post-randomisation, patients in Group I received general anaesthesia, while Group II patients received ultrasound-guided Pecs block followed by general anaesthesia after 20 min. The primary outcome was measured as patient-reported pain intensity using Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) at rest. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t-test and Mann–Whitney U-test. Data were entered into MS Excel spreadsheet and analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 23.0.

Results:

VAS score was significantly lower in Group II at rest and on abduction post-operatively at all time intervals (P < 0.001). The 24-h tramadol consumption was significantly less in Group II compared to Group I (114.4 ± 4.63 mg vs. 402.88 ± 74.22, P < 0.0001).

Conclusion:

Pecs block provided excellent post-operative analgesia in the first 24 h.

Key words: Modified radical mastectomy, nerve block, pectoral nerve, post-operative analgesia

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most commonly occurring cancer in women worldwide and the second-most common cancer in India.[1,2] Nearly 43% of women with breast cancer require mastectomy. Acute post-operative pain causes impairment of respiratory mechanics and gas exchange and presents a challenge for the anaesthesiologist.[3] Poorly controlled pain in the acute phase may also lead to the development of chronic pain syndrome.[4,5]

Traditional pharmacological pain management with opioids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) post-mastectomy has been reported to cause inadequate pain control in 20%–40% of cases.[6]

Several forms of regional techniques such as local anaesthetic infiltration, intercostal nerve block, thoracic epidural block and paravertebral block have been used for the management of pain after breast surgery.[7,8,9,10] These approaches provide effective pain relief and less haemodynamic changes and also preserve pulmonary function, but they may not be suitable in all breast surgeries because they do not block medial and lateral pectoral nerves as well as long thoracic and thoracodorsal nerves. Recently, ultrasound (USG)-guided interfacial plane blocks–pectoral nerve block types I and II (Pecs I and Pecs II) as coined by Blanco in his observational study of fifty patients are novel approaches that block the pectoral, intercostobrachial, third-to-sixth intercostals and the long thoracic nerves.[11,12,13] They are simple, safe and easily performed blocks which provide good analgesia and are devoid of any predicted complication during and after breast surgery. Other advantages of Pecs block include absence of sympathetic block (associated with paravertebral and epidural blocks) and less opioid requirement.

We hypothesised that the analgesic efficacy of Pecs block performed under ultrasound would provide a better post-operative analgesia with fewer complications, in comparison to our standard practice of opioids and NSAIDS.

METHODS

This randomised controlled study was conducted on patients posted for elective unilateral modified radical mastectomy (MRM) at a tertiary care teaching hospital in India, after obtaining ethical clearance. The study period was 1 year from November 2015 to October 2016. After screening for eligibility, the first patient was recruited in November 2015, completed recruitment in October 2016 and completed follow-up in November 2016. The exclusion criteria included patients who did not give consent, those with allergy or sensitivity to local anaesthetic agents, patients having bleeding disorders or on anticoagulants, those having a history of treatment for a chronic pain condition and were on daily analgesics for more than 4 weeks, those with basal metabolic index >35 kg/m2 or the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status >II, patients having chest wall deformity, pregnant patients or patients who had undergone prior breast surgery (except diagnostic biopsies) and those with infection at the site of injection. This study included fifty adult female patients of ASA physical status I or II. A written informed consent was taken from all the patients. The patients once scheduled for surgery by surgery unit were enrolled for study by an independent research assistant. The participants were allocated randomly into two groups of 25 each by a research assistant using computer-based random number generator. The research assistant sealed the codes assigned for allocations corresponding to Pecs group and general anaesthesia-only group in opaque envelopes, which were handed over to consultant anaesthetist who opened the envelopes and performed the block as mentioned in them.

The patients were instructed on usage of a 10-mm Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) for pain (graded from 0 [no pain] to 10 [most severe pain]), before surgery. Pre-operative fasting of 8 h was ensured and a good intravenous (IV) access was secured and IV fluid (Ringer lactate) was started at 10 ml/kg. IV midazolam 0.02 mg/kg was administered to all patients as premedication. In Group I, patients proceeded directly to the operation theatre and were administered general anaesthesia alone. In Group II, patients received ultrasound-guided Pecs block with 30 ml of 0.25% bupivacaine preoperatively and after 20 min of observation shifted to the operation theatre. In the operation theatre, monitoring devices were attached which included non-invasive blood pressure, heart rate (HR), respiratory rate and SpO2, and general anaesthesia was administered. Patients in Group II received a USG Pecs block in the pre-operative area by an expert anaesthesiologist of consultant level that was competent in giving USG blocks and had experience of giving 20 USG Pecs block prior to this study. The patient was kept supine with the ipsilateral upper limb in abducted position and all the standard monitors attached. The skin over the ipsilateral breast and adjoining infraclavicular and axillary regions was disinfected with betadine and sterile draping of the area was done. A linear USG probe of high frequency (6–13 MHz) of a portable ultrasound system (SonoSite, Micromaxx Bothell, Washington, USA) was taken; the probe was covered with a sterile transparent dressing (Tegaderm HP, 3M Healthcare, India) and a sterile conductivity gel was applied. The imaging depth of USG screen was set to 4–6 cm. The USG probe was first placed cephalocaudally in the infraclavicular region and moved laterally to locate the axillary vessels directly above the 1st rib. With further lateral and downward probe movements, the 3rd and 4th ribs were identified. The probe was then manoeuvred as necessary and appropriate anatomical structures including pectoralis major and minor muscles and serratus anterior muscle were identified. With the image centred at the level of the 3rd rib, a puncture site on the skin was selected in line with the probe and infiltrated with 2 ml of 1% lignocaine. The block was performed using a 21G 100-mm short bevelled insulated needle (Stimuplex A, B Braun, Melsungen AG, Germany) using a medial-to-lateral in-plane approach into the fascial plane between pectoralis minor muscle and serratus anterior muscle. A volume of 20 ml of bupivacaine 0.25% was injected in increments of 5 ml after aspiration in real time. The needle was then withdrawn into the fascial plane between the pectoralis major and minor muscles and 10 ml of bupivacaine 0.25% was further injected. The upper and lower levels of sensory block were tested with ice pack and pinprick with a blunt 27G hypodermic needle every 1 min until the onset of sensory blockade. Standard general anaesthesia was given using IV propofol (1.5 mg/kg), fentanyl (2 mg/kg) and vecuronium (0.1 mg/kg). All patients were intubated with cuffed endotracheal tube of size 7.5 mm, connected to anaesthetic workstation and mechanically ventilated with standard settings. Anaesthesia was maintained with nitrous oxide and oxygen (70% plus 30%) and isoflurane (0.8%–1%) with top-up doses of IV vecuronium 0.02 mg/kg. For any intraoperative rise in HR and systolic blood pressure (SBP) more than 20% from pre-induction value, fentanyl 0.25 μg/kg was administered IV by the anaesthetist monitoring the patient. Towards the completion of surgery, IV paracetamol 1 g/100 ml was started and isoflurane was discontinued. The neuromuscular blockade was reversed by IV neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg with glycopyrrolate 0.01 mg/kg.

The primary outcome was measured as patient-reported pain intensity of the ipsilateral upper limb at rest (VAS score at rest) at 1, 6, 12, 18 and 24 h. The secondary outcome measures observed in both groups for 24 h included patient-reported pain intensity during abduction (VAS score on abduction), total post-operative analgesic requirement (tramadol consumption) in the first 24 h, intra-operative and post-operative haemodynamic changes (HR, SBP, diastolic blood pressure [DBP] and mean blood pressure [MBP]) and any adverse effects such as post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV), local anaesthetic (LA) toxicity and pruritus postoperatively. All patients were followed up initially in the surgical ward until discharge and later in surgical outpatient departments for 1 month. All data were observed, recorded, tabulated and statistically evaluated by an observer (junior resident, anaesthesia) and an independent data analyst who were blinded to the study.

Post-operative analgesia was provided by nursing staff with IV paracetamol 1 g every 8 h in both groups. Rescue analgesia was provided by nursing staff who was blinded to the study when the patient complained of pain and having VAS score >4 at rest. IV tramadol 2 mg/kg was used as a rescue analgesic in both groups. A maximum of four doses were given in 24 h. Surgical time was reported in hours by the observer and was defined as the time from skin incision by the surgeon to completion of skin sutures on the operating table. The interval between deposition of local anaesthetic injection and the first reporting of loss of temperature sensation to ice pack and loss of pain sensation on pinprick in both upper and lower levels of breast area was considered as the onset time of block and was recorded by the anaesthesia resident not taking part in the study. Block duration was defined as the interval between completion of the block and the first request by the patient for opioid analgesic (tramadol) in the post-operative period (when VAS >4) up to 24 h and was recorded in hours by the observer blinded to the study.

Sample size calculation was performed using G*Power 3.1.9.2 for windows free online software (University of Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany). For the present study, the distinction in VAS scores at rest in 1st h postoperatively has been considered significant if there was at least two-point difference between patients who received Pecs block and the patients who did not receive the block (variability estimated from an interim analysis; standard deviation [SD]: 1.8). Considering one-tailed significance (α = 0.05) and power of the study (1–β) at 0.80, the total sample size calculated was forty patients (twenty in each group). This number was increased to 25 in each group (total fifty patients) to allow for failure of blocks or case getting cancelled.

Statistical analysis was performed using t-test for mean and SD of onset time of Pecs block, the total duration of analgesia due to block and the mean duration of surgery and haemodynamic variables (HR, SBP, DBP and mean arterial pressure [MAP]). The intergroup differences in VAS scores at rest and abduction were compared non-parametrically using the Mann–Whitney U-test. For all statistical analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and P < 0.001 was considered highly statistically significant. Data were entered into MS Excel spreadsheet and analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

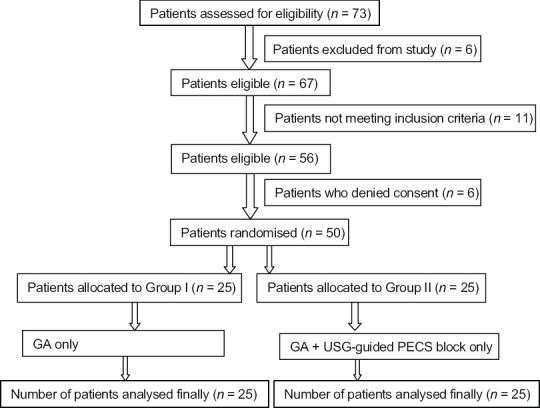

In total, 73 patients were screened for eligibility in the study. The consort diagram of the study is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Consort diagram of study

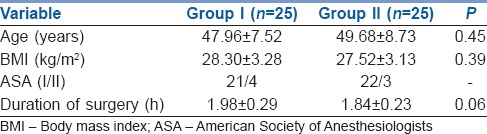

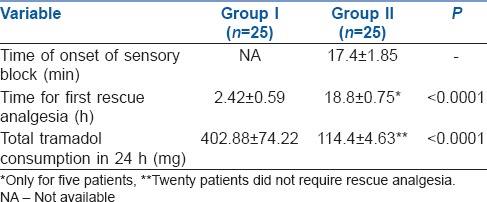

Fifty female patients were recruited in this study and underwent elective unilateral MRM. Patients' demographics and mean duration of surgery are shown in Table 1, which shows no statistically significant difference between the two groups. Adequate sensory level was achieved in all patients and there was no failure of block performed under ultrasound guidance. The mean time of onset of Pecs block was 17.4 ± 1.85 min (min) [Table 2]. The total duration of block was 18.8 ± 0.75 h. The time taken for the first rescue analgesia postoperatively in the first 24 h was significantly increased in Group II as compared to Group I. Twenty patients in Group II did not require rescue analgesia in the first 24 h. The total analgesic requirement (tramadol consumption) during the first 24 h postoperatively was significantly decreased in Group II in comparison with Group I [Table 2].

Table 1.

Patients' demographics and duration of surgery in the two groups

Table 2.

Characteristics of block and total analgesic requirement of tramadol in the two groups

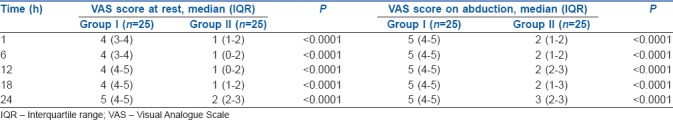

The VAS score at rest was significantly decreased postoperatively in the first 24 h in Group II compared to Group I [Table 3]. The VAS score was increased on abduction of the ipsilateral arm in comparison to score at rest. These scores were also significantly decreased in Group II than in Group I in the first 24 h after surgery [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of Visual Analogue Scale score (median interquartile range) at rest and abduction of arm in both groups in the first 24 h

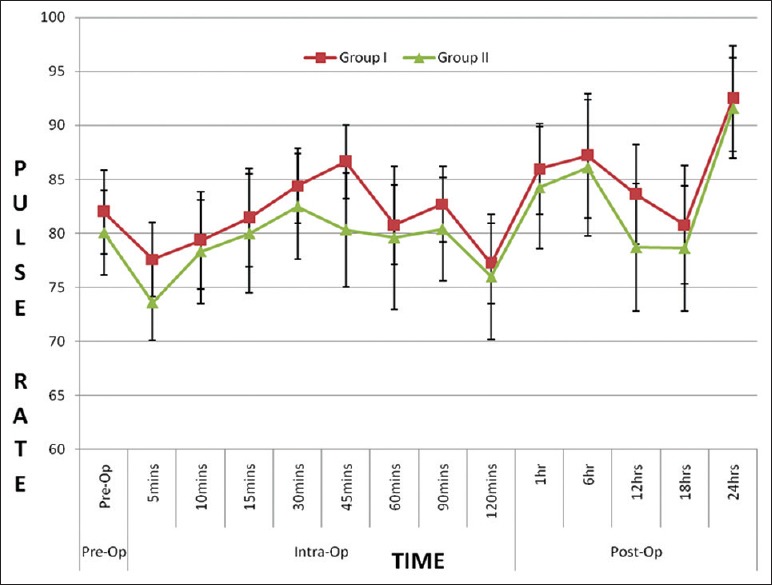

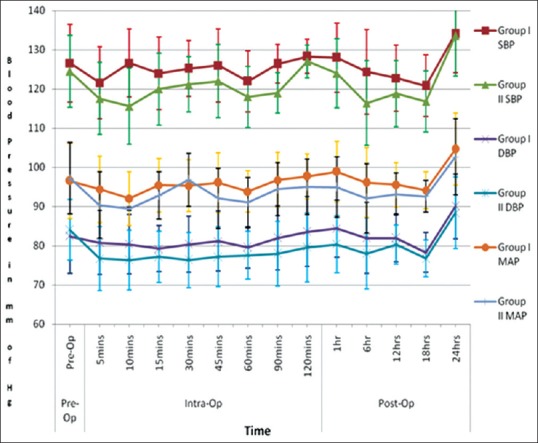

We compared the haemodynamic variables (HR, SBP, DBP and MBP). The change in HR was statistically insignificant in both the groups at all the time intervals measured intraoperatively and postoperatively except at 5 min and 45 min intraoperatively and 12 h postoperatively [Figure 2]. Change in SBP was statistically insignificant in both the groups at all the time intervals measured except 10 min and 90 min intraoperatively and 6 h postoperatively. Changes in MAP and DBP were statistically insignificant in both the groups at all the time intervals measured [Figure 3]. Three patients had nausea and two patients had vomiting in Group I, whereas no patient had any nausea or vomiting in Group II. No other side-effects such as LA toxicity or pruritus were observed in any patients in our study. No complications were reported in the follow-up period.

Figure 2.

Comparison of perioperative mean heart rate in both groups

Figure 3.

Comparison of systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and mean arterial pressure (mmHg) in both groups perioperatively

DISCUSSION

The study shows that Pecs block significantly reduces pain in initial 24 h after MRM. The time taken for first rescue analgesia in Group II was more and twenty patients did not require rescue analgesia in 24 h as compared to patients in Group I. The study findings were comparable with a similar study where the time for the rescue analgesia in Pecs group was more as compared to paravertebral (PVB) group.[14] This study definitely showed better results than another study probably due to the use of the multimodal approach to pain relief as we gave paracetamol at regular intervals in both groups.[14] By combining drugs with different mechanisms of action and routes, we can achieve enhanced analgesic efficacy than single analgesic regimen.

In post-operative period, the mean consumption of tramadol in 24 h was significantly lower (P < 0.0001) in Group II when compared to Group I. These findings of this study were comparable with another study where post-operative morphine consumption at 24 h was significantly lower in Pecs group than in PVB group.[14] In another study, the total morphine consumption in the post-operative period was significantly lower (P < 0.001) in the Pecs group than in control group in breast cancer surgery which again supported this study.[12]

Post-operative pain scores were significantly lower in Group II in this study. In a retrospective study, post-operative pain scores during the 48 h of the post-operative period were significantly lower in the total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA) plus Pecs block group than in the TIVA group.[15] However, there was no significant difference in the percentage of patients requiring supplemental analgesics in both groups, which was in contrast to this study where there was a statistically significant lower requirement of supplemental analgesia in the group receiving Pecs block.[15] This lack of significant differences was attributed to the inability of Pecs block in blocking the anterior cutaneous branches of the intercostal nerves which innervate the parasternal area. Moreover, pain was treated on a case-by-case basis, and concentration and volume of local anaesthetics for Pecs block group were not standardised.

On comparison of mean VAS at rest and on abduction of the arm during 1st, 6th, 12th, 18th and 24th h in the post-operative period, it was found that VAS was significantly lower (P < 0.001) at all times in the first 24 h after surgery in Group II [Table 3]. Although it was found that VAS during abduction of arm increased in Group II, still it was significantly lower than that of Group I. This shows that patients in Group II had better analgesia than in Group I at rest and during abduction at all times in the first 24 h after surgery. The study findings were consistent with a similar study who had better analgesia in Pecs group until 12th h when at rest and until 18th h during movement as compared to PVB group.[14] They had higher pain intensity in Pecs group compared to the paravertebral group in the next 12 h which was explained as due to the effacing effect of local anaesthetic. However, in this study, pain score in Group II was lower all throughout 24 h of the post-operative period probably due to our multimodal approach to pain relief.

In a study, it was reported that interference of injectate reduces the efficacy of the electrocautery.[16] In this study, no such incidence was reported probably because the time of Pecs block to surgical incision was more than 20 min and this interval may have altered local anaesthetic absorption from the surgical field.

In this study, there was no significant difference in intra- and post-operative haemodynamic parameters between the two groups [Figures 2 and 3], which is supported by a similar study where pectoral nerve block and thoracic paravertebral block were compared for mastectomy.[17] In this study, better haemodynamic stability was observed intraoperatively in Group II. Thus, it can be said that Pecs block has no untoward effect on HR, SBP, DBP and MAP of the patients. The haemodynamic stability assumes greater importance in patients with significant comorbidities or those who are nutritionally weak after chemotherapy, radiotherapy or of advanced age.

Adverse effects such as LA toxicity and pruritus were not observed in any patient in our study. Three patients had nausea and two patients had vomiting in Group I, whereas no patient had any nausea or vomiting in Group II. However, in contrast, there was no incidence of PONV in either groups of a similar study.[15]

The study results are excellent as far as analgesia, safety and simplicity are concerned, but there are a few limitations to this study. This being non-double-blinded study, chances of patient and observer bias cannot be ruled out. We did not give Sham block to Group I as it would be ethically incorrect to do needling without giving any therapeutic drug. However, this was difficult to avoid because of understanding of the patient and medical staff of the nature of this study. Pecs block is an ultrasound-guided block which has a learning curve associated with it. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) was not used in this study, which could help standardise tramadol administration for all patients. It may be noted that ultrasound guidance will not eliminate complications completely and may not provide precise localisation in morbid obese patients or patients with huge breast tissue. Frequent negative aspiration during injection, hydro localisation with normal saline which helps identify needle tip in the target area, using shallow angle of needle entry in relation to the probe, jiggling of needle to locate needle tip by observing tissue movement and avoiding injection of drug against resistance are some of the key methods suggested in various studies to avoid major complications such as inadvertent IV injection or mechanical neural damage. A dual approach using peripheral nerve stimulator and ultrasound may be tried. We did not measure pulmonary function test of the two groups, to see if there was any significant difference in pulmonary function postoperatively. High-powered study with larger sample size may be needed further to reinforce findings of this study. Ultrasound-guided blocks allow real-time visualisation of needle placement, so chances of needle traversing the tumour are unlikely; however, possibility cannot be out rightly rejected. Lack of any complication combined with a high success rate in this study definitely supports the safety and efficacy of Pecs block for post-operative analgesia for MRM. The regular use of Pecs block as part of multimodal analgesia for post-surgical pain is recommended for quick recovery and reduced hospital stay and complications. USG Pecs block is a simpler technique with low complication rate and may be superior to paravertebral block and thoracic epidural for post-operative analgesia after breast surgery. However further studies with larger sample size to improve the power of study may be needed to advocate the same. Based on our findings, further studies may be conducted for a Pecs block-based opioid-free anaesthesia.

CONCLUSION

Pecs block offers significant advantages in terms of post-operative pain relief, post-operative rescue drug consumption, PONV and overall patient satisfaction.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta S. Breast cancer: Indian experience, data, and evidence. South Asian J Cancer. 2016;5:85–6. doi: 10.4103/2278-330X.187552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tuncel G, Ozalp G, Savli S, Canoler O, Kaya M, Kadiogullari N, et al. Epidural ropivacaine or sufentanil-ropivacaine infusions for post-thoracotomy pain. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;28:375–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richardson J, Lönnqvist PA. Thoracic paravertebral block. Br J Anaesth. 1998;81:230–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/81.2.230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richardson J, Lönnqvist PA, Naja Z. Bilateral thoracic paravertebral block: Potential and practice. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:164–71. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeq378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poleshuck EL, Katz J, Andrus CH, Hogan LA, Jung BF, Kulick DI, et al. Risk factors for chronic pain following breast cancer surgery: A prospective study. J Pain. 2006;7:626–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talbot H, Hutchinson SP, Edbrooke DL, Wrench I, Kohlhardt SR. Evaluation of a local anaesthesia regimen following mastectomy. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:664–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang TT, Parks DH, Lewis SR. Outpatient breast surgery under intercostal block anesthesia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1979;63:299–303. doi: 10.1097/00006534-197903000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynch EP, Welch KJ, Carabuena JM, Eberlein TJ. Thoracic epidural anesthesia improves outcome after breast surgery. Ann Surg. 1995;222:663–9. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199511000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coveney E, Weltz CR, Greengrass R, Iglehart JD, Leight GS, Steele SM, et al. Use of paravertebral block anesthesia in the surgical management of breast cancer: Experience in 156 cases. Ann Surg. 1998;227:496–501. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199804000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nair AS, Sahoo RK, Ganapathy M, Mudunuri R. Ultrasound guided blocks for surgeries/procedures involving chest wall (Pecs 1, 2 and serratus plane block) Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2015;19:348–51. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bashandy GM, Abbas DN. Pectoral nerves I and II blocks in multimodal analgesia for breast cancer surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2015;40:68–74. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanco R. The 'pecs block': A novel technique for providing analgesia after breast surgery. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:847–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wahba SS, Kamal SM. Thoracic paravertebral block versus pectoral nerve block for analgesia after breast surgery. Egypt J Anaesth. 2013;1:30. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morioka H, Kamiya Y, Yoshida T, Baba H. Pectoral nerve block combined with general anesthesia for breast cancer surgery: A retrospective comparison. JA Clin Rep. 2015;1:15. doi: 10.1186/s40981-015-0018-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakshi SG, Karan N, Parmar V. Pectoralis block for breast surgery: A surgical concern? Indian J Anaesth. 2017;61:851–2. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_455_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Annamalai G, Durairaj AK, Kailasam KR. Pectoral nerve block versus thoracic paravertebral block – Comparison of analgesic efficacy for postoperative pain relief in modified radical mastectomy surgeries. J Evol Med Dent Sci. 2017;6:4412–6. [Google Scholar]