Abstract

Background

This is the first trial to directly compare efficacy and safety of alectinib versus standard chemotherapy in advanced/metastatic anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients who have progressed on, or were intolerant to, crizotinib.

Patients and methods

ALUR (MO29750; NCT02604342) was a randomized, multicenter, open-label, phase III trial of alectinib versus chemotherapy in advanced/metastatic ALK-positive NSCLC patients previously treated with platinum-based doublet chemotherapy and crizotinib. Patients were randomized 2 : 1 to receive alectinib 600 mg twice daily or chemotherapy (pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 or docetaxel 75 mg/m2, both every 3 weeks) until disease progression, death, or withdrawal. Primary end point was investigator-assessed progression-free survival (PFS).

Results

Altogether, 107 patients were randomized (alectinib, n = 72; chemotherapy, n = 35) in 13 countries across Europe and Asia. Median investigator-assessed PFS was 9.6 months [95% confidence interval (CI): 6.9–12.2] with alectinib and 1.4 months (95% CI: 1.3–1.6) with chemotherapy [hazard ratio (HR) 0.15 (95% CI: 0.08–0.29); P < 0.001]. Independent Review Committee-assessed PFS was also significantly longer with alectinib [HR 0.32 (95% CI: 0.17–0.59); median PFS was 7.1 months (95% CI: 6.3–10.8) with alectinib and 1.6 months (95% CI: 1.3–4.1) with chemotherapy]. In patients with measurable baseline central nervous system (CNS) disease (alectinib, n = 24; chemotherapy, n = 16), CNS objective response rate was significantly higher with alectinib (54.2%) versus chemotherapy (0%; P < 0.001). Grade ≥3 adverse events were more common with chemotherapy (41.2%) than alectinib (27.1%). Incidence of AEs leading to study-drug discontinuation was lower with alectinib (5.7%) than chemotherapy (8.8%), despite alectinib treatment duration being longer (20.1 weeks versus 6.0 weeks).

Conclusion

Alectinib significantly improved systemic and CNS efficacy versus chemotherapy for crizotinib-pretreated ALK-positive NSCLC patients, with a favorable safety profile.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02604342; Roche study MO29750

Keywords: alectinib, ALK, chemotherapy, crizotinib, NSCLC

Key Message

In ALUR, alectinib significantly improved systemic and CNS efficacy versus chemotherapy in patients with crizotinib-pretreated anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The safety profile of alectinib was favorable compared with chemotherapy. The data support alectinib as a new standard of care for patients with crizotinib-pretreated ALK-positive NSCLC.

Introduction

Crizotinib is approved for treatment-naïve and pretreated anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK)-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). However, most ALK-positive NSCLC patients who receive first-line crizotinib progress within 1 year, often in the central nervous system (CNS) [1, 2]. Although ceritinib is approved for patients with ALK-positive NSCLC whose disease has progressed on crizotinib [3, 4], treatment is associated with significant side effects [5, 6]. Thus, a high unmet medical need exists for these patients.

Based on clinical trial data [7–9], alectinib is approved for patients with advanced/metastatic ALK-positive NSCLC who have progressed on/are intolerant to crizotinib [10, 11], and treatment-naïve ALK-positive NSCLC [12, 13]. In the crizotinib-failure setting, alectinib achieved median progression-free survival (PFS) of 8.9 months [95% confidence interval (CI): 5.6–12.8] in study NP28673 (NCT01801111; phase II, single-arm) and 8.1 months (95% CI: 6.2–12.6) in study NP28761 (NCT01871805 phase II, single-arm) [8]. Alectinib was well tolerated in both studies. Pooled data from these trials demonstrated alectinib activity in the CNS [14].

ALUR (MO29750; NCT02604342; phase III, randomized) examined alectinib efficacy and safety versus chemotherapy in advanced/metastatic ALK-positive NSCLC pretreated with platinum-based doublet chemotherapy (PDC) and crizotinib.

Patients and methods

Patients

Patients had histologically/cytologically confirmed advanced, recurrent, or metastatic ALK-positive NSCLC; two prior lines of systemic therapy (including one line of PDC and one of crizotinib); measurable disease (Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors [RECIST] v1.1); Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS) 0–2. Patients with CNS metastases were allowed if asymptomatic, or symptomatic and ineligible for radiotherapy. Full eligibility criteria are in the supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Study design

ALUR was a randomized, open-label, phase III trial. Patients were randomized 2 : 1 to receive alectinib 600 mg twice daily, or chemotherapy (pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 or docetaxel 75 mg/m2, every 3 weeks, at the investigators’ discretion) until disease progression, death, or withdrawal. Randomization was carried out using the following stratification factors: ECOG PS (0/1 versus 2); baseline CNS metastases (yes/no); and, for patients with baseline CNS metastases, brain radiotherapy history (yes/no). Crossover from chemotherapy to alectinib was permitted following progression. At the investigators’ discretion, alectinib could be continued beyond radiologic progression until loss of clinical benefit. The primary analysis cutoff was 26 January 2017, when the sponsor became aware of 50 PFS events. Additional information regarding the study design is in the supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Primary end point was investigator-assessed PFS with alectinib versus chemotherapy in the intent-to-treat (ITT) population. A key secondary end point was CNS objective response rate (ORR) in patients with measurable baseline CNS disease. Other secondary end points included: Independent Review Committee (IRC)-assessed PFS; ORR, disease control rate (DCR), and duration of response (DOR; investigator- and IRC-assessed); time to CNS progression by baseline CNS disease; CNS DCR and CNS DOR in patients with baseline CNS metastases; overall survival (OS); safety. CNS end points were IRC-assessed. The supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online provides end point definitions.

ALUR was undertaken in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guidelines. The protocol was approved by institutional review boards/ethics committees at each participating site. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Study assessments

Disease was assessed at screening and every 6 weeks until progression. Response (RECIST v1.1) was assessed by investigators using physical examinations, computed tomography scans, and magnetic resonance imaging. Adverse events (AEs) were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0, and classified according to the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities. The dose reduction schedule is provided (supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Statistical analyses

The ITT population comprised all patients randomized. The safety population comprised all patients who received ≥1 dose of assigned study medication. ITT patients with measurable and/or nonmeasurable baseline CNS disease comprised the CNS ITT (C-ITT) population; C-ITT patients were further classified into those with measurable (mC-ITT) or nonmeasurable baseline CNS disease (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

The study design was based on a sample size of 120 patients for 80% power of the log-rank test (two-sided α at 0.05) to detect a significant improvement in median PFS (primary end point) from 3 to 6 months with alectinib [hazard ratio (HR) 0.5; 74 events]. As data from alectinib phase II trials indicated a consistent PFS of >8 months [7, 8], the protocol was amended to detect a significant improvement in median PFS from 3 to 7 months (HR 0.43; 50 events) and the sample size was reduced to 90 patients for 80% power (two-sided α at 0.05) (protocol V5). The analysis populations (ITT2, C-ITT2, and mC-ITT2) for protocol V5 are detailed in the supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Primary analysis of investigator-assessed PFS (ITT) was carried out using a stratified Cox model including treatment arm variable and stratification factors. Estimates for PFS were obtained using a Kaplan–Meier approach, the P-value of log-rank test was calculated with estimated HRs (stratified Cox model) and corresponding 95% CIs (Brookmeyer and Crowley method). Hypothesis testing for the primary end point was carried out (two-sided α at 0.05). If superiority for the primary end point was concluded, subsequent hierarchical testing for the key secondary end point, CNS ORR in patients with measurable baseline CNS metastases, was carried out (70% power at one-sided 5% α). Additional details regarding methods are described in the supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Results

Patients

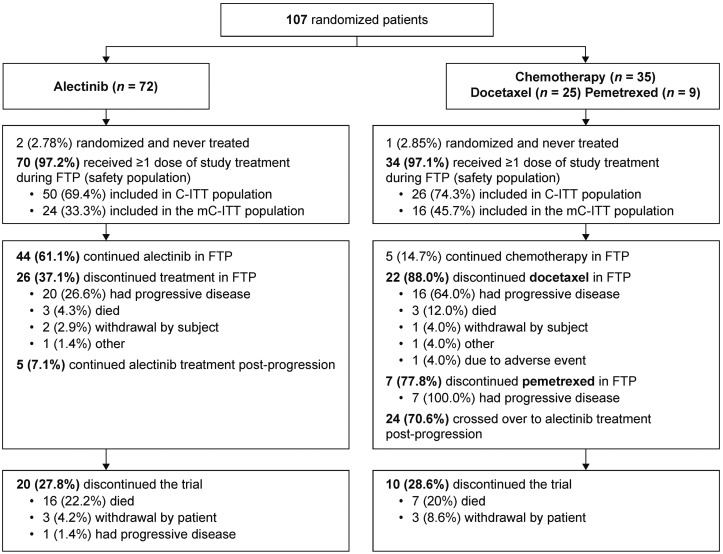

ALUR was conducted at 40 centers in Europe and Asia. At the data cutoff, 52 events were reached; 107 patients were randomized 2 : 1 to receive alectinib (n = 72) or chemotherapy (n = 35) (ITT; Figure 1). The safety population comprised alectinib, n = 70 (97.2%); chemotherapy, n = 34 (97.1%; docetaxel n = 25, pemetrexed n = 9).

Figure 1.

Patient disposition in the ALUR study. C-ITT, patients in the ITT population with CNS disease at baseline; CNS, central nervous system; FTP, first treatment period; ITT, intent-to-treat; mC-ITT, patients in the ITT population with measurable CNS disease at baseline.

In the ITT population, 76 patients (71.0%) had baseline CNS disease (alectinib, n = 50; chemotherapy, n = 26; C-ITT population) and 31 patients (29.0%) did not (alectinib, n = 22; chemotherapy, n = 9). In the C-ITT population, 40 patients (52.6%) had measurable baseline CNS disease (mC-ITT population) and 36 patients (47.4%) had nonmeasurable baseline CNS disease.

At baseline, minor stratification imbalances were observed (Table 1): more patients who received alectinib had ECOG PS 0/1 [66/72 (91.7%) versus 30/35 (85.7%)] and no baseline CNS metastases [25/72 (34.7%) versus 9/35 (25.7%)]. Postprogression treatment data are presented in supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics of the ITT and C-ITT populations

| ITT (n = 107) |

C-ITT (n = 76) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alectinib | Chemo | Alectinib | Chemo | |

| (n = 72) | (n = 35) | (n = 50) | (n = 26) | |

| Median age, years (minimum, maximum) | 55.5 (21, 82) | 59.0 (37, 80) | 55.0 (21, 82) | 58.5 (37, 79) |

| Age category (years), n (%) | ||||

| 18–64 | 60 (83.3) | 25 (71.4) | 41 (82.0) | 19 (73.1) |

| ≥65 | 12 (16.7) | 10 (28.6) | 9 (18.0) | 7 (26.9) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 41 (56.9) | 17 (48.6) | 27 (54.0) | 14 (53.8) |

| Female | 31 (43.1) | 18 (51.4) | 23 (46.0) | 12 (46.2) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Asian | 5 (6.9) | 7 (20.0) | 2 (4.0) | 5 (19.2) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (1.4) | 0 | 1 (2.0) | 0 |

| White | 61 (84.7) | 28 (80.0) | 43 (86.0) | 21 (80.8) |

| Unknown | 5 (6.9) | 0 | 4 (8.0) | 0 |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||

| Never | 35 (48.6) | 16 (45.7) | 23 (46.0) | 11 (42.3) |

| Current | 2 (2.8) | 2 (5.7) | 2 (4.0) | 1 (3.8) |

| Previous | 35 (48.6) | 17 (48.6) | 25 (50.0) | 14 (53.8) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | ||||

| 0 | 29 (40.3) | 11 (31.4) | 18 (36.0) | 9 (34.6) |

| 1 | 37 (51.4) | 19 (54.3) | 26 (52.0) | 13 (50.0) |

| 2 | 6 (8.3) | 5 (14.3) | 6 (12.0) | 4 (15.4) |

| Histology, n (%) | ||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 72 (100) | 35 (100) | 50 (100) | 26 (100) |

| Disease stage at baseline, n (%) | ||||

| Stage IIIB | 3 (4.2) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (2.0) | – |

| Stage IV | 69 (95.8) | 34 (97.1) | 49 (98.0) | 26 (100) |

| CNS metastases at baseline, n (%) | ||||

| Yes | 47 (65.3) | 26 (74.3) | – | – |

| No | 25 (34.7) | 9 (25.7) | – | – |

| If yes, were the CNS metastases treated?a | ||||

| Yes | 28 (59.6) | 15 (57.7) | – | – |

| No | 19 (40.4) | 11 (42.3) | – | – |

| If treated, type of therapyb | ||||

| Whole-brain radiotherapy | 23 (82.1) | 9 (60.0) | – | – |

| Radiosurgery | 2 (7.1) | 5 (33.3) | – | – |

| Brain surgery | – | 2 (13.3) | – | – |

| Other | 3 (10.7) | – | – | – |

| Diagnostic testing, n (%)c | ||||

| FISH | ||||

| Abbott catalog no. 06N38-020 | 45 (62.5) | 24 (68.6) | 30 (60.0) | 18 (69.2) |

| Abbott catalog no. 06N43-020 | 4 (5.6) | 2 (5.7) | 4 (8.0) | 2 (7.7) |

| Other | 7 (9.7) | 2 (5.7) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (3.8) |

| IHC | ||||

| Ventana CE IVD: 06679072001 | 10 (13.9) | 4 (11.4) | 9 (18.0) | 4 (15.4) |

| Other | 6 (8.3) | 3 (8.6) | 6 (12.0) | 1 (3.8) |

Percentage is based on number of subjects with CNS metastases at baseline.

Percentage is based on number of subjects with treated CNS metastases at baseline—a subject may be counted in more than one therapy (when multiple therapies are checked).

Percentages are based on the number of subjects with a local ALK testing.

ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; Chemo, chemotherapy; C-ITT, patients in the ITT population with CNS disease at baseline; CNS, central nervous system; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; IHC, immunohistochemistry; ITT, intent-to-treat.

Efficacy

Progression-free survival

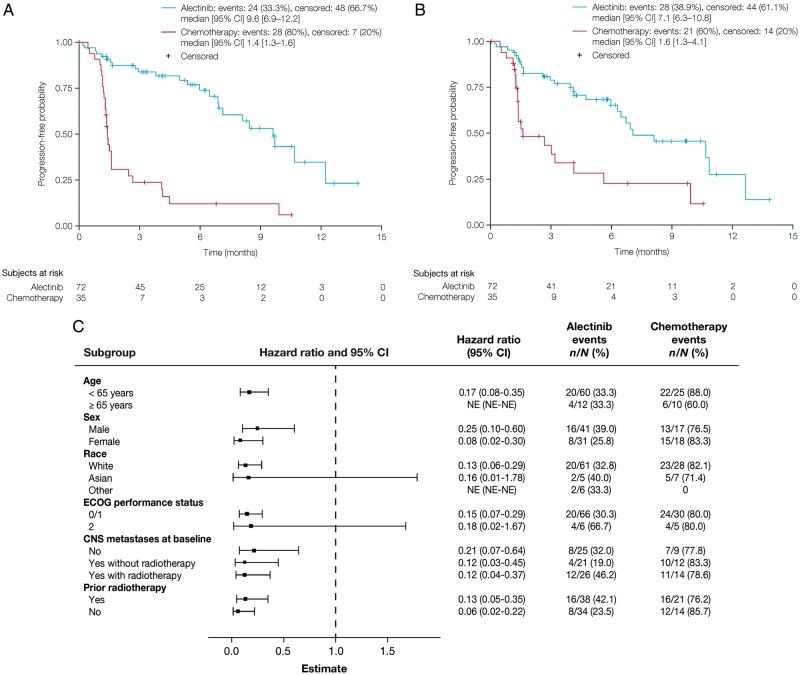

ALUR met its primary end point, showing superior PFS for alectinib versus chemotherapy. Median investigator-assessed PFS was 9.6 months (95% CI: 6.9–12.2; alectinib) and 1.4 months (95% CI: 1.3–1.6; chemotherapy) [HR 0.15 (95% CI: 0.08–0.29); P < 0.001] (Figure 2A). A multivariable Cox model adjusted for baseline stratification imbalances confirmed a significant improvement in PFS for alectinib [HR 0.16 (95% CI: 0.09–0.30); P < 0.01]. IRC-assessed PFS was also significantly longer with alectinib [HR 0.32 (95% CI: 0.17–0.59); median PFS was 7.1 months (95% CI: 6.3–10.8, alectinib) and 1.6 months (95% CI: 1.3–4.1, chemotherapy); Figure 2B].

Figure 2.

PFS in the intent-to-treat population. (A) PFS by investigator assessment, (B) PFS by Independent Review Committee assessment, and (C) subgroup analysis of investigator-assessed PFS. CI, confidence interval; NE, not evaluable; PFS, progression-free survival.

Improvements in investigator-assessed PFS were seen across subgroups for age, sex, baseline CNS metastases, prior radiotherapy, ECOG PS 0/1, and White race (Figure 2C). ECOG PS 2 and Asian race had wide CIs due to small sample sizes (<10 patients; Figure 2C). PFS data by baseline CNS disease are in the supplementary material, available at Annals of Oncology online.

Response rate

IRC-assessed CNS ORR was significantly higher with alectinib versus chemotherapy in patients with baseline CNS disease (Table 2). In the mC-ITT population, CNS ORR was significantly higher with alectinib [13/24 patients (54.2%)] than chemotherapy (0/16 patients; P < 0.001). CNS DCR was higher with alectinib than chemotherapy in the mC-ITT population (Table 2). Median CNS DOR was longer with alectinib than chemotherapy in the mC-ITT population [not reached (NR, 95% CI: 3.6–NR) versus 0 months]. Post hoc efficacy analyses carried out on a subset of all randomized patients at the cutoff date (90 patients; ITT2 population) confirmed data from the ITT population (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). The treatment effect with alectinib was consistent across all relevant subgroups (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 2.

CNS ORR and CNS DCR in patients with baseline CNS disease

| Outcome | C-ITT population (n = 76) |

mC-ITT population (n = 40) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alectinib (n = 50) | Chemo (n = 26) | Alectinib (n = 24) | Chemo (n = 16) | |

| CNS BOR, n (%) | ||||

| CR | 6 (12.0) | 0 | 1 (4.2) | 0 |

| PR | 12 (24.0) | 0 | 12 (50.0) | 0 |

| SD | 22 (44.0) | 7 (26.9) | 6 (25.0) | 5 (31.3) |

| PD | 4 (8.0) | 12 (46.2) | 3 (12.5) | 8 (50.0) |

| NE | 6 (12.0) | 7 (26.9) | 2 (8.3) | 3 (18.8) |

| CNS ORR, n (%) | 18 (36.0) | 0 (0) | 13 (54.2) | 0 (0) |

| 95% CI | 23–51 | 0–13 | 33–74 | 0–21 |

| Difference (95% CI) | 36.0 (13–57) | 54.2 (23–78) | ||

| P-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| CNS DCR, n (%) | 40 (80.0) | 7 (26.9) | 19 (79.2) | 5 (31.3) |

| 95% CI | 66–90 | ?>12–48 | 58–93 | 11–59 |

| Difference (95% CI) | 53.1 (30–71) | 47.9 (16–73) | ||

| P-value | <0.001 | 0.002 | ||

BOR, best overall response; CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; DCR, disease control rate; mC-ITT, patients in the ITT population with measurable CNS disease at baseline; NE, not evaluable; ORR, overall response rate; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

Investigator-assessed ORR (ITT) was 37.5% (27/72 patients; alectinib) versus 2.9% (1/35 patients; chemotherapy; supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online). DCR and median DOR (both ITT, investigator-assessed) are presented in the supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online.

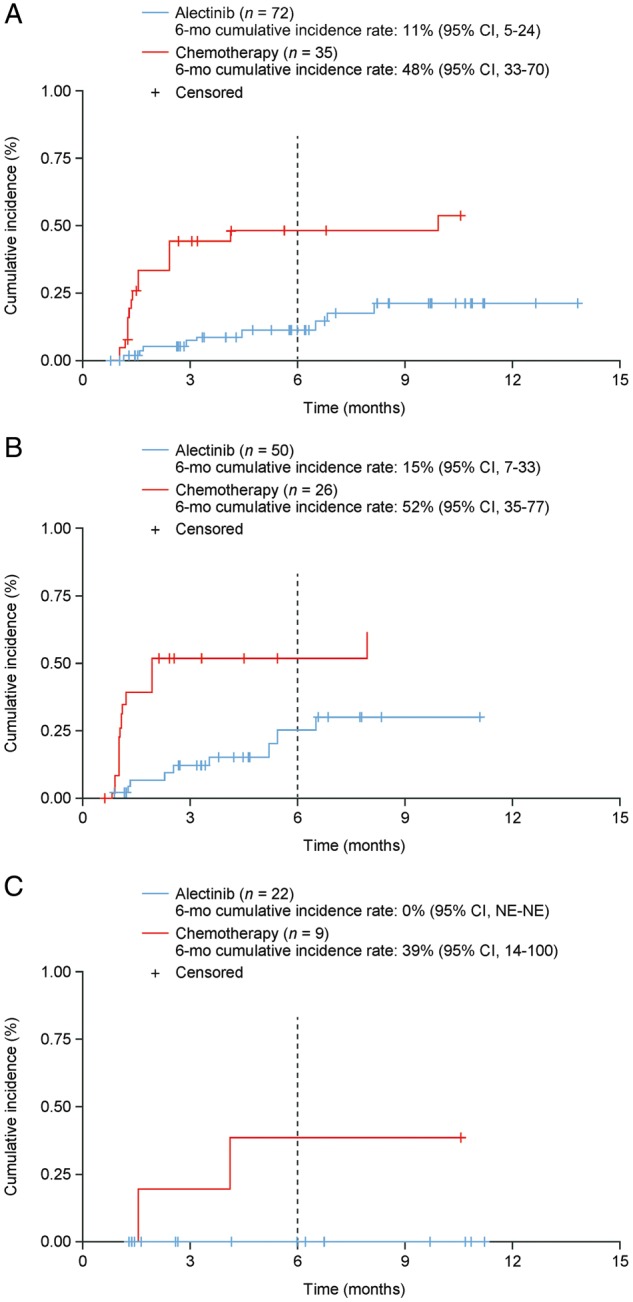

CNS progression

Time to CNS progression (ITT, IRC-assessed) was significantly longer with alectinib versus chemotherapy (cause-specific HR 0.14; 95% CI: 0.06–0.36; supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). Similar results were observed for the C-ITT population (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). The cumulative incidence rate (CIR) of CNS progression, with adjustment for the competing risks of non-CNS progression and death, was consistently lower over time with alectinib than chemotherapy (Figure 3). The 6-month CIR of CNS disease progression was lower with alectinib versus chemotherapy in all populations examined (supplementary Table S6, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 3.

Cumulative incidence of CNS progression, non-CNS progression, and death in: (A) the ITT population, (B) the C-ITT population, and (C) patients in the ITT population without CNS disease at baseline. CI, confidence interval; C-ITT, patients in the ITT population with CNS disease at baseline; CNS, central nervous system; ITT, intent to treat; NE, not evaluable.

Overall survival

Twenty-four patients (70.6%) crossed over from chemotherapy to alectinib following progression. At cutoff, OS data were immature (events: 22% alectinib, 20% chemotherapy). OS was not significantly different between alectinib and chemotherapy [HR 0.89 (95% CI: 0.35–2.24); median 12.6 months (95% CI: 9.7–NR) versus NR (95% CI: NR–NR)].

Safety

Median treatment time was 20.1 weeks (range 0.4–62.1; alectinib) and 6.0 weeks (range 1.9–47.1; chemotherapy). Median safety follow-up was 6.5 months (95% CI: 4.7–8.2; alectinib) and 5.8 months (95% CI: 4.2–9.0; chemotherapy).

Incidences of all-grade and serious AEs were similar between arms (Table 3). One fatal AE deemed unrelated to study treatment was reported with chemotherapy (bacterial pneumonia); no fatal AEs were reported with alectinib. AEs occurring with a frequency difference of ≥5% between alectinib and chemotherapy, respectively (Table 3), were constipation, dyspnea, and increased blood bilirubin. AEs more common with chemotherapy than alectinib were fatigue, nausea, alopecia, neutropenia, diarrhea, pruritus, stomatitis, and bacterial pneumonia (Table 3). AEs occurring in ≥10% of patients in either arm are in supplementary Table S7, available at Annals of Oncology online. Grade ≥3 AEs were more common with chemotherapy (41.2%) than alectinib (27.1%) (supplementary Table S8, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 3.

Safety overview and AEs occurring with a frequency difference of ≥5% between treatment arms (safety population)

| Preferred term, n (%) | Alectinib (n = 70) | Chemotherapy (n = 34) |

|---|---|---|

| AEs (all grades) | 54 (77.1) | 29 (85.3) |

| Serious AEs | 13 (18.6) | 5 (14.7) |

| Grade 3–5 AEs | 19 (27.1) | 14 (41.2) |

| Fatal AEs | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) |

| AEs leading to treatment discontinuation | 4 (5.7) | 3 (8.8) |

| AEs leading to dose reduction | 3 (4.3) | 4 (11.8) |

| AEs leading to dose interruption | 13 (18.6) | 3 (8.8) |

| Fatigue | 4 (5.7) | 9 (26.5) |

| Constipation | 13 (18.6) | 4 (11.8) |

| Nausea | 1 (1.4) | 6 (17.6) |

| Neutropenia | 2 (2.9) | 5 (14.7) |

| Diarrhea | 2 (2.9) | 3 (8.8) |

| Pruritus | 0 | 3 (8.8) |

| Dyspnea | 6 (8.6) | 0 |

| Stomatitis | 0 | 2 (5.9) |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 4 (5.7) | 0 |

| Alopecia | 0 | 6 (17.6) |

| Bacterial pneumonia | 0 | 2 (5.9) |

AE, adverse event.

Incidence of AEs leading to study-drug discontinuation was numerically lower, despite longer treatment duration, with alectinib (alectinib 5.7%; chemotherapy 8.8%; supplementary Table S9, available at Annals of Oncology online). Dose reductions and interruptions are in supplementary Tables S10 and S11, available at Annals of Oncology online, respectively.

Discussion

Alectinib is highly active in ALK-positive NSCLC patients experiencing progression on crizotinib [7, 8]. In two phase III trials, superiority of alectinib over crizotinib was reported in patients with treatment-naïve ALK-positive NSCLC [9, 15]. ALUR aimed to demonstrate superiority of alectinib over chemotherapy in patients pretreated with PDC and crizotinib.

The primary end point was met; median PFS (investigator-assessed) was 9.6 months (alectinib) versus 1.4 months [chemotherapy; HR 0.15 (95% CI: 0.08–0.29); P < 0.001]. IRC-assessed PFS was 7.1 months (alectinib) versus 1.6 months [chemotherapy; HR 0.32 (95% CI: 0.17–0.59)], consistent with the median IRC-assessed PFS achieved with chemotherapy in ASCEND-5 (1.6 months) and with alectinib in phase II trials (8.1–8.9 months) [7, 8]. IRC-assessed PFS for alectinib was shorter than investigator-assessed PFS, with a difference in the magnitude of the treatment effect (HR 0.32 versus 0.15, respectively). This could be due to the open-label design of ALUR; investigators were not blinded to treatment and may have been subject to unintentional bias, whereas the blinded IRC process actively minimizes variation in interpretation. However, the secondary end point of IRC-assessed PFS was clinically meaningful, confirming the treatment benefit observed with alectinib versus chemotherapy. Safety and tolerability of alectinib compared favorably with chemotherapy, despite the substantially longer treatment duration with alectinib (20 weeks versus 6 weeks with chemotherapy), and was consistent with previous trials. Grade ≥3 AEs were more common with chemotherapy (41.2%) than alectinib (27.1%). AEs leading to study-drug discontinuation were lower with alectinib (5.7%) than chemotherapy (8.8%). At this cutoff, OS data were immature, and two-thirds of patients had crossed over from chemotherapy to alectinib following progression. ALUR was not powered for OS.

ORR with alectinib was lower in ALUR (37.5%) than the phase II trials (50%–52%). Possibly because in ALUR, 10/72 alectinib patients were not evaluable for response, as two consecutive response assessments had not yet been achieved. There were also differences between the trial designs. Prior treatment differed between ALUR (all patients pretreated with crizotinib and PDC) and the phase II trials (crizotinib-failure setting) [7, 8]. When comparing the 96 patients in NP28673 who had been pretreated with chemotherapy and crizotinib (study population similar to ALUR) with the ALUR ITT2 population, the ORRs are similar (44.8% and 43.3%, respectively).

Baseline CNS metastases are present in approximately one-third of ALK-positive NSCLC patients [16, 17], and are associated with reduced life expectancy and quality of life [18]. Many advanced ALK-positive NSCLC patients experience progression within 1 year of first-line crizotinib [19, 20], frequently within the CNS [1, 2]. In ALUR, CNS efficacy was improved with alectinib versus chemotherapy regardless of baseline CNS disease and prior CNS radiotherapy. IRC-assessed CNS ORR in patients with measurable baseline CNS disease was 54.2% (alectinib) versus 0% (chemotherapy), indicating that alectinib actively controls CNS metastases in patients with baseline CNS involvement. These results indicate that alectinib may delay or prevent development of CNS disease in patients without baseline CNS metastases, and are consistent with pooled CNS efficacy data from the two phase II alectinib trials [14].

ALUR limitations include the small sample size for the chemotherapy arm and imbalance between docetaxel and pemetrexed (chemotherapy arm). There was a large difference between the arms in treatment duration, which should be considered in the safety comparison. Recruitment was ongoing at the primary analysis, resulting in a short follow-up time for the last patients randomized.

ALUR data should be considered in light of the changing treatment landscape for ALK-positive NSCLC. Although ASCEND-5 established ceritinib as a superior treatment option versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive NSCLC pretreated with crizotinib and chemotherapy [21], median PFS with alectinib in ALUR has exceeded that observed with ceritinib (IRC; alectinib 7.1 months, ceritinib 5.4 months) whereas median PFS for chemotherapy was 1.6 months on both studies. The phase III Japanese J-ALEX and global ALEX studies in crizotinib-naïve ALK-positive NSCLC showed superior efficacy with alectinib and a safety profile that compared favorably with crizotinib [15, 16]. The treatment landscape has been redefined following the ALEX data, with the NCCN guidelines now including alectinib as a category 1 recommendation (preferred treatment) [22]. In future, the number of patients treated with chemotherapy and crizotinib before being offered alectinib may decline, dependent on the given reimbursement situation and practice patterns.

Our data support the efficacy and tolerability of alectinib, and demonstrate that alectinib shows clinically relevant superiority to chemotherapy for extra- and intracranial disease in patients who have been pretreated with crizotinib and PDC. Thus, alectinib can be considered as the standard treatment in this setting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients and their families who participated in this study, and all of the study centers. The authors are also grateful to Benjamin Esterni (Cytel, Geneva, Switzerland) for providing invaluable support regarding the data analyses. Third-party medical writing assistance, under the direction of the authors, was provided by Emma Evans, PhD, of Gardiner-Caldwell Communications, and was funded by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Funding

F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. (no grant number applies).

Disclosure

SN has received personal fees from Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Roche, and AstraZeneca. JM has received personal fees from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, BMS, MSD, Novartis, Roche, and BMS; and grants from AstraZeneca and Roche. JdC has received personal fees from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Novartis, MSD, BI, Roche, and BMS. MRM has received personal fees from BMS, BI, MSD, and AstraZeneca. RD has received personal fees from Novartis, Roche, and Pfizer. FG has received personal fees and/or grants from AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Novartis, MSD, BI, Roche, Lilly, BMS, Celgene, Takeda, and Chugai. AK and AC are employees of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. AZ, BB, and AD-G are employees of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., and hold stock ownership in F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. HKJ is a contractor of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. JW has received personal fees from AstraZeneca, BMS, BI, Chugai, Ignyta, Lilly, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, and Roche. The remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Chun SG, Choe KS, Iyengar P. et al. Isolated central nervous system progression on crizotinib: an Achilles heel of non-small cell lung cancer with EML4-ALK translocation? Cancer Biol Ther 2012; 13(14): 1376–1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Costa DB, Shaw AT, Ou SH. et al. Clinical experience with crizotinib in patients with advanced ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer and brain metastases. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33(17): 1881–1888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. FDA Approval for Ceritinib. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/fda-ceritinib (March 2018, date last accessed).

- 4.EMA Zykadia recommended for approval in advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/news_and_events/news/2015/02/news_detail_002279.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058004d5c1 (March 2018, date last accessed).

- 5. Stenger M. Ceritinib in ALK-positive metastatic NSCLC patients with progression on or intolerance to crizotinib. The ASCO Post 10 June 2014, Volume 5, Issue 9. http://www.ascopost.com/issues/june-10,-2014/ceritinib-in-alkpositive-metastaticnsclcpatients-with-progreesion-on-or-intolerance-tocrizotinib.aspx (March 2018, date last accessed).

- 6.Zykadia™ (ceritinib) USPI, April 2014. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/205755lbl.pdf (March 2018, date last accessed).

- 7. Ou SH, Ahn JS, De Petris L. et al. Alectinib in crizotinib-refractory ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer: a phase II global study. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(7): 661–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shaw AT, Gandhi L, Gadgeel S. et al. Alectinib in ALK-positive, crizotinib-resistant, non-small-cell lung cancer: a single-group, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17(2): 234–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Peters S, Camidge DR, Shaw AT. et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in untreated ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2017; 377(9): 829–838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. FDA Approval for Alectinib. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/InformationOnDrugs/ApprovedDrugs/ucm584082.htm (March 2018, date last accessed).

- 11. European Medicines Agency (EMA). European public assessment report (EPAR) for Alecensa. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Summary_for_the_public/human/004164/WC500225710.pdf; February 2017. (March 2018, date last accessed).

- 12. Roche media release. https://www.roche.com/media/store/releases/med-cor-2017-10-13.htm (March 2018, date last accessed).

- 13. Roche media release. https://www.roche.com/media/store/releases/med-cor-2017-11-07.htm (March 2018, date last accessed).

- 14. Gadgeel SM, Shaw A, Govindan R. et al. Pooled analysis of CNS response to alectinib in two studies of pre-treated ALK+ NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol 2015; 10(Suppl 2): abstract 1219. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hida T, Nokihara H, Kondo M. et al. Alectinib versus crizotinib in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (J-ALEX): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017; 390(10089): 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johung KL, Yeh N, Desai NB. et al. Extended survival and prognostic factors for patients with ALK-rearranged non–small-cell lung cancer and brain metastasis. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34(2): 123–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhang I, Zaorsky NG, Palmer JD. et al. Targeting brain metastases in ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16(13): e510–e521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guerin A, Sasane M, Wakelee H. et al. Treatment, overall survival, and costs in patients with ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer after crizotinib monotherapy. Curr Med Res Opin 2015; 31(8): 1587–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ou SH, Jänne PA, Bartlett CH. et al. Clinical benefit of continuing ALK inhibition with crizotinib beyond initial disease progression in patients with advanced ALK-positive NSCLC. Ann Oncol 2014; 25(2): 415–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Solomon BJ, Mok T, Kim D-W. et al. First-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-positive lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(23): 2167–2177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shaw AT, Kim TM, Crinò L. et al. Ceritinib versus chemotherapy in patients with ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer previously given chemotherapy and crizotinib (ASCEND-5): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017; 18(7): 874–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN guidelines), Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, version 9.2017, October 17, 2017. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/drugs/fda-ceritinib (March 2018, date last accessed).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.