Abstract

Devolution changes the locus of power within a country from central to sub-national levels. In 2013, Kenya devolved health and other services from central government to 47 new sub-national governments (known as counties). This transition seeks to strengthen democracy and accountability, increase community participation, improve efficiency and reduce inequities. With changing responsibilities and power following devolution reforms, comes the need for priority-setting at the new county level. Priority-setting arises as a consequence of the needs and demand for healthcare resources exceeding the resources available, resulting in the need for some means of choosing between competing demands. We sought to explore the impact of devolution on priority-setting for health equity and community health services. We conducted key informant and in-depth interviews with health policymakers, health providers and politicians from 10 counties (n = 269 individuals) and 14 focus group discussions with community members based in 2 counties (n = 146 individuals). Qualitative data were analysed using the framework approach. We found Kenya’s devolution reforms were driven by the need to demonstrate responsiveness to county contexts, with positive ramifications for health equity in previously neglected counties. The rapidity of the process, however, combined with limited technical capacity and guidance has meant that decision-making and prioritization have been captured and distorted for political and power interests. Less visible community health services that focus on health promotion, disease prevention and referral have been neglected within the prioritization process in favour of more tangible curative health services. The rapid transition in power carries a degree of risk of not meeting stated objectives. As Kenya moves forward, decision-makers need to address the community health gap and lay down institutional structures, processes and norms which promote health equity for all Kenyans.

Keywords: Decentralization, priority setting, decision making, equity, community health

Introduction

Devolution reforms

Devolution reforms are political by nature, leading to changing power and influence between actors, following the transfer of administrative, political and fiscal responsibilities from central to sub-national locally elected governments (Bossert and Beauvais 2002). A form of decentralization, devolution should transfer power and decision-making from central stakeholders to sub-national levels through shifting relationships, bringing decision-making closer to the population. Devolution has the potential to allow users to shape service provision, to increase responsiveness and faster implementation by avoiding central bureaucracy, to improve quality, transparency and accountability through community oversight and involvement in decision-making, and to reduce existing inequities through distribution to traditionally marginalized groups (Bossert and Beauvais 2002; Bossert 1998; Cheema and Rondinelli 2007; Mitchell and Bossert 2010), (Faguet and Pöschl 2014). Past experiences with devolution however have demonstrated the complexity of the process in practice, that outcomes can be unpredictable and that there can be a widening rather than a reduction in disparities (Eaton et al. 2010; Prud’homme 1995). Evidence in fact suggests that ‘decentralisation has done little to improve the quantity, quality or equity of public services in the (Sub-Saharan Africa) region’ (Conyers 2007, p. 21). Potential threats with implications for community-participation within the politics of priority-setting, and protective measures, can be considered in light of Walt and Gilson’s health policy analysis framework according to the context, process, actors and content of reforms for priority-setting, as summarized in Table 1 (Conyers 1983; Prud’homme 1995; Cheema and Rondinelli 2007; Walt and Gilson 1994; Bossert and Mitchell 2011; Bossert 2015).

Table 1.

Threats and protective measures influencing the success of devolution reforms

| Threat | Protective measure | |

|---|---|---|

| Context | This political process occurs within and is influenced by the social, economic and political context. Historical norms may permit nepotism and corruption, may continue and thrive unless challenged by transparent and strong accountability mechanisms. | The ‘handing over’ of responsibilities between levels is a political process, influenced by the unique social, economic and political context within which reforms occur. Ideally reform process should be carefully planned out in advance and take place over time. Knowledge and recognition of the context and introductions of actions to challenge existing norms should be put in place to ensure distribution of funds which takes into consideration the underlying county poverty level and ability to raise sufficient local revenue. |

| Process | Resistance to the reform process by central government actors, may contribute to ineffective implementation and failure to build capacity for local government. | Strong and committed political leadership at national and sub-national levels, with willingness to share power, authority and financial resources. |

| Lack of clarity on roles and responsibilities by actors will hinder transparency and contribute to confusion within the priority-setting process. | Clear understanding at each level of rights, expected standards, roles and responsibilities | |

| Actors | Limited administrative and management capacity within local government, may deepen inequalities between formerly marginalized and non-marginalized areas | Actions planned in advance of reforms to build adequate institutional capacity for administrative, technical, organizational, financial and human resource management across the system and at individual level. |

| Failure to address power imbalances between actors within counties may lead to entrenchment of influence in favour of local elites and continued exclusion of vulnerable individuals from priority-setting processes. | Accountability measures should be established in advance, which are responsive to local civil society preferences, while still ensuring improved population health and health sector performance. | |

| Content | If poorly planned, devolution may contribute to the selection of priorities which increase disparities. | If well planned with needed capacity and accountability measures in place there is opportunity to reduce inequities and promote UHC. |

Capacity and accountability are vital for the success of decentralization (Bossert and Mitchell 2011). Where these are not sufficiently established prior to decentralization of functions, there is the risk that decision-making actors do not have sufficient capacity to take advantage of the new decision space available to them (Cheema and Rondinelli 2007), and of ‘elite capture’, where powers that have been decentralized do not empower the general community but instead go to a local elite (Conyers 1983; Mills 1990), who may then exploit priority-setting in order to consolidate political support and maximize voter base (Goddard et al. 2006). This may both exclude marginalized people from playing a role in making decisions relating to their health and lead to the setting of priorities which do not contribute towards attaining universal health coverage (UHC).

Kenyan health system and devolution

Health service delivery in Kenya is organized around the new Kenya Essential Package for Health (KEPH) (Ministry of Medical Services and Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation 2012), according to a four level system as described in the current national Health Policy, which indicates Kenya’s commitment to UHC. Kenya’s national health policy is operationalized according to the Kenya Health Sector Strategic and Investment Plan (2014–2018) (Republic of Kenya 2014). Kenya devolved services1 (including health) in 2013 from a single central government to 47 new sub-national governments, known as counties (see Box 1). Devolution reforms occurred in response to widespread frustrations with inefficiencies and inequities with the former centralized government and growing local and international pressure following post-election violence in 2007–2008 (Cornell and D’Arcy 2014; Tsofa et al. 2017b). Inequities in Kenya are rooted in the historical and social structural forces originating from colonization, and contribute to widely varied levels of poverty, education, development, resource allocation and investment for infrastructure and human resources (Ministry of Health 2014; Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and ICF Macro 2014; Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and Society for International Development 2013; Ministry of Health [Kenya] and World Health Organisation 2013). Devolution in Kenya therefore seeks to ‘tackle long- term, deeply entrenched disparities between regions; increase the responsiveness and accountability of government to citizens; allow greater autonomy to different regions and groups, and re-balance power away from a historically strong central government’ (Kenya School of Government and The World Bank 2015, p. 2).

Key Messages

Devolution changes power dynamics and relationships, presenting sub-national authorities with greater decision space and the potential for improved equity.

Common decentralization aims to increase citizen participation, accountability, efficiency and equity are not likely to be achieved if sub-national levels do not have the capacity to make wise decisions or respect for accountability mechanisms.

Kenyan county governments have often prioritized visible health interventions which appeal to their electorate, leading to over-emphasis on curative health services with neglect of preventive services, including community health approaches.

Devolution in Kenya appears to have improved equity between counties, but inequities persist within counties.

The Constitution outlined a 3 year transition of functions from national to county governments (National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General 2010). However, in response to pressure from the county governments all functions to be undertaken in counties were transferred in June 2013, just four months after county level elections (held in March 2013) and before county government structures had been fully established to carry out these functions (Tsofa et al. 2017b). This unplanned adoption of a ‘big-bang’ approach with reforms occurring nationwide provided little transition time or scope to learn lessons in advance (Overseas Development Institute 2016).

Equity in healthcare in Kenya

Since reducing inequities is a central objective for devolution according to the Constitution 2010, it is important to assess the implications of these reforms for equity of healthcare. Namely whether there are systematic disparities in access and use of healthcare services, and/or equity in health financing, where equity is defined as when people contribute to healthcare payments based on their ability, and benefit from healthcare based on their need. For example, allocations across sub-counties or health services should be based on healthcare needs of the population/region. In order to address some of the inequities between geographic regions, Kenya has introduced changes to resource allocation, through transfer of the equitable share funding from central government to county governments, determined by the commission for revenue allocation formula (Commission on revenue allocation 2016), which takes into account each county’s poverty level, along with an equalization fund for formerly marginalized counties (National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General 2010). Formerly marginalized counties now therefore benefit from higher levels of funding, along with the decision space to invest in health. There are few published studies of county level priority-setting processes following devolution in Kenya. However, a recent study conducted in one county found that in the year following the introduction of devolution, there was limited community or stakeholder involvement in the process (Tsofa et al. 2017b). In addition, removal of user fees combined with delayed release of funds from the county treasury resulted in challenges with financial management at health facility level, leading some health facility in-charges to re-introduce user fees in order to continue providing services, with implications for the poorest service users (Nyikuri et al. 2015).

Priority-setting

Priority-setting arises as a consequence of the needs and demands for healthcare resources (such as budget, staff time, equipment and facilities) exceeding the resources available, requiring some means of choosing between competing demands (Mitton 2002). Policymakers need to balance both the need to set priorities fairly and efficiently with safeguarding citizens’ right to health (Rumbold et al. 2017). Earlier studies of priority-setting following devolution in Kenya have revealed a limited role for citizens and technical staff (particularly within hospitals) within the process, limited capacity at sub-national level (for coordinating community health services) and importance of political influence, use of power and visibility regarding the priorities selected (Lipsky et al. 2015; Overseas Development Institute 2016; Barasa et al. 2016; HECTA Consulting 2015; Tsofa et al. 2017a,b). The changing roles and responsibilities for these health actors across health systems levels before and after devolution are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Main roles and responsibilities for national and sub-national structures for community health planning before and after devolution

| Pre-devolution | Post-devolution | |

|---|---|---|

| National |

|

|

| Province |

|

Does not exist |

| County | Did not exist |

|

| District/ sub-county |

|

|

| CHEWs and CHVs | Develop annual workplan and budget in collaboration with community health committee and share with health facility in-charge |

|

| Community members |

|

|

Roles that changed after devolution are in italics and unchanged roles are in plain text.

Community health services in Kenya

According to all major health policies and strategies in Kenya, county authorities have a legal mandate to provide community health services as the first tier in the health system (Ministry of Medical Services and Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation 2012; Ministry of Health [Kenya] 2014a,b). When adequately supported by the health system and strong community structures, community health workers (CHWs) can promote equitable access and use of health promotion, disease prevention and curative services at community and facility levels, thereby playing a central role in the drive towards UHC (Tulenko et al. 2013). By linking communities with the health system, CHWs have the potential to re-dress power imbalances and generate community empowerment, particularly within lower–middle income countries (McCollum et al. 2016; Kok et al. 2016). Within Kenya, CHWs have been shown to significantly increase the use of health services at household, community and facility level (Olayo et al. 2014), providing pro-poor delivery of prompt and effective malaria treatment (Siekmans et al. 2013). However, coverage with community-based services is uneven, often donor driven and not necessarily based on need (McCollum et al. 2016) and therefore may be open to manipulation, as part of a complex system.

Shortly after devolution, the Kenyan national community health and development unit revised the community health strategy. Kenya has two main types of CHW—community health volunteers (CHVs) and salaried community health extension workers (CHEWs). The structure and role for CHVs and CHEWs changed in response to identification of gaps and challenges with the prior strategy (McCollum et al. 2016). The decision space created by devolution presents the opportunity for counties to address disparities, by planning and budgeting to adapt the new community health strategy according to local county context and disease burden. In response to the limited evidence surrounding priority-setting for community health to date, we sought to explore priority-setting context, content, processes and actors (Walt and Gilson 1994). The introduction of devolution raises a host of questions which we have sought to explore, including: Is health equity considered when health priorities are set? How has devolution influenced the equity of health services? How has devolution influenced the provision of community health services? By answering these questions we aim to identify implications for community health and equity between and within counties, from a range of perspectives in the immediate period following devolution.

Methods

Methods and approach

We adopted a naturalistic research paradigm using multiple qualitative methods to observe changes and understand the process, power and politics at play within priority-setting and implications for community health and equity following devolution in Kenya. Key informant interviews, in-depth interviews and focus group discussions (FGDs) were used to capture a range of perspectives, including ‘traditional’ policymakers along with voices typically ‘unheard’ in policy discussions. The research was conducted together with LVCT Health, a Kenyan institution, embedded in Kenyan policy and practice.

Site and respondent selection

Ten counties were selected in order to include diversity between the counties studied by ensuring that counties selected represented a mixture of marginalized and non-marginalized counties [according to those identified as marginalized and receiving the additional equalization fund from national government (Business Daily 2013)], a range of poverty levels, geographic settings and health service coverage levels (see Table 3). Interviews with 269 individuals and 14 FGDs with an additional 146 participants were conducted in total between March 2015 and April 2016 (see Table 4). Fourteen national level key informants were selected purposively using a snowball approach to identify other potential respondents who could contribute valuable information. In-depth interviews with 120 purposively selected county level decision-makers were conducted in 10 diverse counties to include politicians involved with decision-making for health, county treasury staff involved with budget guidance, gender and children’s office representatives, county executive committee (CEC) members for health, chief officers for health and technical decision-makers, including members of the county health management team. Interviews with 49 health workers from sub-county, health facility and community levels were carried out in 3 counties, with 86 interviews with CHVs, CHEWs, their supervisors and community members in 2 counties (see Table 4). Voices of multiple stakeholders were included to capture varied perspectives in relation to community health, which are often unheard following devolution reforms (Masanyiwa et al. 2015).

Table 3.

Key indices for study counties

| County | Marginalizeda/not marginalized | Poverty incidence (headcount ratio)b | Rural/urban | Province | Live births in previous 5 years % delivered by skilled providerc | % children age 12–23 months who are fully vaccinatedc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homa Bay | Not marginalized | 48.4% | Rural agrarian | Nyanza | 60.4% | 53.7% |

| Kajiado | Not marginalized | 38.0% | Rural nomadic | Rift Valley | 63.2% | 48.9% |

| Kituid | Not marginalized | 60.4% | Rural agrarian | Eastern | 46.2% | 52.7% |

| Kwale | Marginalized | 70.7% | Rural agrarian | Coast | 50.1% | 82.0% |

| Marsabite | Marginalized | 75.8% | Rural nomadic | Eastern | 25.8% | 66.6% |

| Meru | Not marginalized | 31.0% | Rural agrarian | Eastern | 82.8% | 78.3% |

| Nairobid | Not marginalized | 21.8% | Urban | Nairobi | 89.1% | 60.4% |

| Nyeri | Not marginalized | 27.6% | Rural agrarian | Central | 88.1% | 77.8% |

| Turkana | Marginalized | 87.5% | Rural nomadic | Rift Valley | 22.8% | 56.7% |

| Vihiga | Not marginalized | 38.9% | Rural agrarian | Western | 50.3% | 90.9% |

| National average | 45.2% | 61.8% | 67.5% |

Counties considered marginalized are those which receive the additional equalization fund for the fourteen most marginalized counties in the country.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics. Economic Survey. Nairobi, Kenya; 2014.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Ministry of Health, National AIDS Control Council, Kenya Medical Research Institute, National Council for Population and Development. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey: Key Indicators. Nairobi, Kenya; 2014.

Interviews also carried out with health workers from sub-county, health facility and community level and interviews with CHVs, CHEWs, their supervisors and FGDs with community members.

Interviews also carried out with health workers from sub-county, health facility and community level.

Table 4.

Respondent demographics

| Male | Female | # respondents | |

|---|---|---|---|

| {G1}National key informant interviews | |||

| County representative for CEC forum at national level | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| National Ministry of Health | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| NGO/research institute/ donor | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Total national respondents | 11 | 3 | 14 |

| {G1}County level in-depth interviews (ten counties) | |||

| CEC member for health | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| Chief officer for health | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| Director/deputy director for health | 17 | 2 | 19 |

| CHMT member | 19 | 13 | 32 |

| Total county level health respondents | 49 | 21 | 70 |

| Children’s office representative | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| Gender representative | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Member of county assembly (or representative) | 15 | 5 | 20 |

| County treasury representative | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Other county informants | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Total county level non-health respondents | 37 | 13 | 50 |

| {G1}Multi-level in depth interviews (three counties) | |||

| CHEW/CHV | 6 | 6 | 12 |

| Health facility in-charge | 8 | 9 | 17 |

| Hospital in-charge | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| NGO coordinator based at county level | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Sub-county community health focal person | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Sub-county medical officer | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Total multi-level respondents | 32 | 17 | 49 |

| {G1}Community health in-depth interviews (two counties) | |||

| CHV | 12 | 12 | 24 |

| CHEW | 4 | 2 | 7a |

| Community health committee member | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| CHV team leader | 4 | 9 | 13 |

| Health facility in-charge | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Sub-county community health focal person | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Community key informants | 11 | 6 | 17 |

| Total IDI respondents | 46 | 39 | 86 |

| Total participants | 175 | 93 | 269 |

| {G1}Community member FGDs (two counties) | |||

| FGDs | 7 | 7 | 14 |

Unrecorded gender one respondent.

Development of data collection tool and analysis

We developed a topic guide based upon aspects of the Accountability for Reasonableness Framework which recognizes the importance of fair process for priority-setting according to the relevance of priority-setting process to meet health needs within reasonable resource constraints; ‘publicity’ and transparency of priority setting process, priorities and their rationale to all those affected by them; opportunity for challenge of decisions through appeals and revision mechanisms and enforcement/leadership and public regulation to ensure that the other conditions have been met (Daniels and Sabin 2002). We used questions to explore the new priority-setting process for community health within counties, the actors involved in making decisions, the values and factors which influence priority-setting, influence of devolution on community health services and health equity. A framework approach to analysis was used to classify and organize data according to themes, concepts and emerging categories (Ritchie and Lewis 2003). This included an inductive approach to enable meaning to emerge from the data through familiarization by reading and rereading transcripts before development of the coding framework, based upon prior knowledge of literature, topic guide themes and issues raised by respondents themselves. NVivo10 software was used to code and manage data.

Quality assurance

Qualitative data were recorded with the participants’ consent and transcribed verbatim. Discussions and interviews conducted in Kiswahili or Kikamba were translated to English, with a selection back-translated for quality-checking. Data collection continued until saturation was reached and data were triangulated between sources to minimize bias. The main interviewer for national, county and health worker interviews was a foreign researcher, with community and CHW interviews and discussions carried out by Kenyan researchers. Being part of an embedded Kenyan institution with regular discussions, presentations with colleagues and other researchers within and outside Kenya and reflection of our different positions as UK and Kenyan researchers were an important part of strengthening validity throughout the research process.

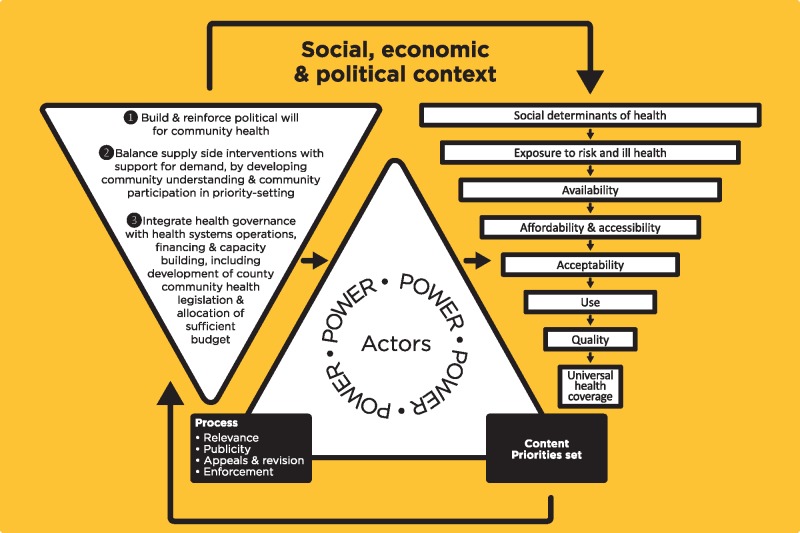

Conceptual framework and ethics

Results are presented in line with a conceptual framework based on study findings and adapted from a number of existing frameworks (see Figure 1) (Walt and Gilson 1994; Tanahashi 1978; Brinkerhoff and Bossert 2008; Daniels and Sabin 2002). This seeks to link governance reform principles supportive of community health, model for health policy analysis, the Accountability for Reasonableness process conditions and the influence of the content of priorities selected on the availability, affordability, accessibility, acceptability, use and quality of services provided. Ethical approval was received from Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) and Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, with research permit from National Commission for Science Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework

Results

Context of reforms

Kenya, a geographically, culturally, economically and disease burden diverse country experiences wide variations in health service coverage, care-seeking practices and mortality rates across counties, as has been described according to the literature in the background section. Study respondents commonly felt many of these disparities were a consequence of the former centralized government.

Equity … in fact that is one of the things why devolution was formed in Kenya, because there was a lot of concentration of resources or even health care facilities in some areas more than the others (County Health Respondent, Male20).

Almost all respondents felt devolution was driven by the desire to bring services closer to the community and to address inequities, with actions having been introduced across counties with the aim of addressing these goals. We also found frequent examples where low accountability and failure to address the norms, structures and discriminations which drive inequality such as corruption, tribalism, patronage and patriarchal norms, have led to neglect of certain communities even after devolution.

Let me just say our village is among those that have been… neglected… and this is brought about by political differences… You find that village, because they did not choose that councillor or member of county assembly, it's neglected (Nairobi Male CHW team leader03).

Process of reforms for priority-setting for community health

Devolution in Kenya brought rapid transfer of authority and responsibilities to county governments, including planning, budgeting, implementation and management of health services for community and primary health care and referral up to county level. The introduction of devolution in Kenya led to changing roles and power for actors across the health system (see Table 2), with reduced role for national level in coordinating partners, recruitment and management of health workers and planning for budget allocation, but retained responsibility for policy development, quality assurance and provision of national referral (Level 4) services. The former district level (now largely considered similar to the sub-county level, although there are also some counties which were former districts) which prior to devolution had responsibility for annual planning and budget allocation for management of user fees continues to hold responsibility to implement and deliver health services, but no longer has control over budget allocation (Tsofa et al. 2017b; Nyikuri et al. 2017). Unfortunately, there has been a lack of clear and transparent guidance from national level to guide the process or roles and responsibilities (see Supplementary material).

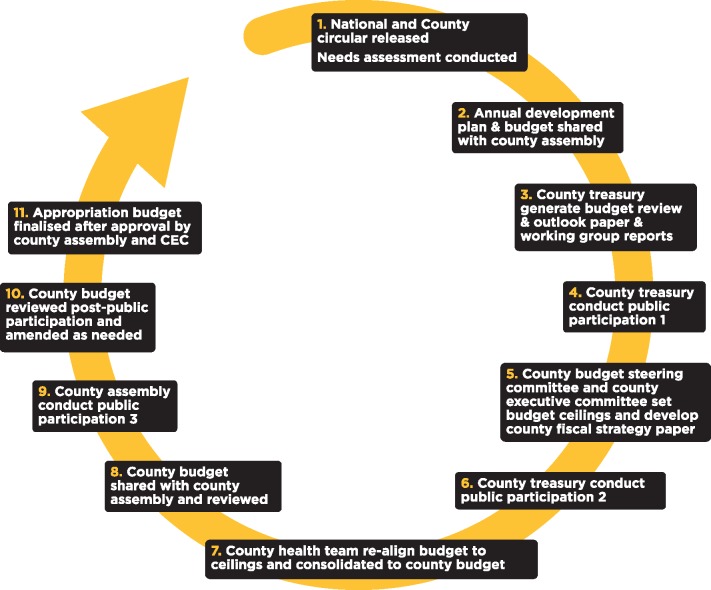

According to the Constitution of Kenya (2010), county level actors are now responsible for budget allocation and annual planning as well as developing the 5-year county integrated development plan (CIDP) and the 5-year county strategic plan for health. These plans should align with national health policy and strategic planning documents, including community health strategy guidance (Ministry of Health [Kenya] 2014b). County level also hold responsibility for health service delivery for level one to three services (community, primary and county referral services), recruitment and management of health workers and coordination of partners. Within the county, a number of actors are engaged in the priority-setting process for the annual budget and planning cycle (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

County level annual planning and budgeting cycle

Officially, the annual planning and budgeting cycle should be guided by the 5-year CIDP and county strategic plan for health, under the oversight of the county treasury (see Figure 2). According to guidance this process should follow a series of agreed steps, with the CEC member for health leading the development of an annual plan and budget for health, which is then amalgamated with the respective plans and budgets for the other county departments, to create the county annual plan and budget, in accordance with the CIDP and available budget, allowing opportunity for community participation to identify needs and priorities. This is first approved by the CEC, before it is shared with the legislative arm of government (the county assembly), who should validate the community priorities, before it is approved and publicized. Unfortunately, the process for how priorities should be weighed and compared was unclear, allowing for greater influence of local politics (see Power and capacity of actors and implications for community health section).

At community level, citizens should be engaged through a combination of new and pre-existing avenues, including participation through new public participation forums carried out as part of the county annual planning and budgeting process and inclusion of community inputs through community dialogue days (community level health-related discussions, using locally generated community data which should be facilitated by CHEWs and CHVs); inclusion of community representation in community health committees, health facility management committees and quarterly health stakeholder meetings which ought to feed into the county prioritization process. Barriers to citizen engagement are described below and in the Supplementary material.

Power and capacity of actors and implications for community health

Overwhelmingly, the findings from this study relate to capacity and power. Limited technical, political and community capacity for county priority-setting was identified as a challenge by national level respondents, and to a lesser degree by technical decision-makers at county and health facility levels. The expertise of key technical decision-makers who lead the priority-setting process, such as the CEC member for health or chief officer for health was felt to be of critical importance. Experience ranged from no health-related experience, purely clinical experience to strong public health experience, between counties. Technical decision-makers felt inadequate public health experience impedes wise priority-setting, which reflects and balances both preventive and curative needs, including community health approaches. Similarly, community members and powerful political decision-makers were perceived to have limited understanding of health, restricting their ability to recognize important priorities.

As a consequence of the rapid transition of power and resources, communication channels between national and county authorities were unclear, leading to mistrust between actors at both levels. There was limited capacity building, clarity or guidance surrounding the uncharted roles and responsibilities for new decision-making actors at county and community levels. This hindered transparent and accountable priority-setting processes (see Supplementary material), allowing space for opportunistic actors to seize power, contributing to selection of ‘high-vote’ priorities. In many counties we found a preference (particularly by politicians) for high visibility curative interventions above preventive health services, including community health actions.

Many of them (politicians) see the importance of curative services but they do not see the strength or the importance of the health promotion, public health activities, and therefore getting financial allocation to that department has been a challenge. Because …they make decisions based on votes, will this get me more votes? So they do not tend to see that when we prevent malaria or prevent diarrhoea that you are going to get votes (County Health Respondent, Male02).

Public participation forums provide a mechanism for community involvement in identifying and setting priorities. While reported by policy players as key mechanisms to strengthen accountability to the community, most county governments have not yet addressed the factors which influence meaningful engagement (see Supplementary material), including the multiple barriers faced by ‘disadvantaged groups’ to engaging in these processes. Neither has they adequately informed citizens about their rights, provided them with needed information for making decisions or explained their role within priority-setting. This has contributed to community confusion about participation, dominance of local elite or possible manipulation of community members when identifying priorities.

Those who have been given that responsibility to inform the government, they don't reach out to the citizens… So who will you report all those challenges to? (Nairobi Female FGD01)

There was also limited evidence in the majority of counties for action to empower citizens to understand health holistically, including the need for a balance of preventive, promotive, curative and rehabilitative services. As a result of this limited knowledge by community members there is the threat, which was identified by many technical actors from the majority of counties, that community members may prioritize curative services over preventive and promotive ones. This will be important to address moving forward in light of the increasing non-communicable disease (NCD) burden and the vital importance of taking action to prevent NCDs.

…they (community) need to have a wider perspective of how [health is] not just a hospital (County Health Respondent, Male50).

Mechanisms for community empowerment through ownership of local data were not commonly described by county decision-makers as forming part of the priority-setting process. Established mechanisms, such as dialogue days were hindered by donor dependence, where community participation dropped whenever donor support for meetings ended (see Supplementary material), limiting opportunity for transfer of power into the hands of the community through community-led data monitoring. These challenges were experienced by most counties. Although, we found positive examples of community empowerment around priority-setting, which resulted in community members’ identification of the need for community-based health services and was then reflected within the annual plan and budget (see Box 2, example 2). There is scope for further study to unpack how different community members are involved within this process and in other county contexts.

Box 1. Overview of Kenya’s health system

Country context

Kenya, a lower–middle-income country situated in East Africa, has an estimated population of 46.05 million (2015 estimates). Communicable diseases still make up the leading causes of death, but NCDs are creating an increasing burden on the health system.

Governance

Since 2013 Kenya operates with a devolved system of governance, with 47 sub-national authorities known as counties and a wide range of governance roles and responsibilities devolved to county level (see Table 1).

At the county level there are two arms of government—the CEC (who have responsibility to implement legislation, manage functions of the county administration and its departments and any other functions mandated by the Constitution) and the county assembly (who have powers of enacting legislation at county, provide oversight to the executive and approve plans and policies for resource management).

Health service delivery

Health service delivery level is organized around a four level system, (1) community services, (2) primary health services, (3) county referral services and (4) national referral services. County authorities are responsible for providing services in levels one to three and national level is responsible for providing national referral services. Community health services, form the first level in the health system and underpin Kenya’s plan for attaining UHC.

Sources: Ministry of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, 2012. Kenya Health Policy 2012–2030. Nairobi, Kenya; National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General, 2010. The Constitution of Kenya. Nairobi, Kenya; http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/kenya/overview.

Supplementary material highlights further accountability mechanisms identified by respondents which should guide priority-setting for health according to policy (first column) and some of the barriers experienced with their adoption (second column). There is need for stronger accountability mechanisms and learning from best practice to ensure policy objectives are met (recommendations column).

Box 2. Examples of best practice: stronger, more equitable community health priority setting

In a formerly marginalized county with a large nomadic population, low rates of skilled delivery prior to devolution, with long distances between populations and their closest health facility, where citizens often cross international borders, actions have been introduced to strengthen community health services. The community health strategy has been modified to ensure that a CHV is recruited from within each community, who then moves with their community and has the ability to use a satellite phone (originally provided for reasons of insecurity) to communicate with members of the health team in the event of an obstetric emergency. In addition, this county has decentralized authority to use facility improvement funds to hospitals and is planning for further decentralization to lower levels. Actors from this county self-identified a capacity gap within the county technical priority-setting team and in response ensured that all county level decision making actors underwent appropriate leadership training.

In another formerly marginalized agrarian county, community members had repeatedly requested infrastructure and ambulances, with no requests for community health actions during public participation meetings in the initial two years after devolution. County level technical actors introduced extensive measures to educate and empower the community to understand health holistically and to inform ‘powerful’ decision-makers such as members of county assembly about the politically appealing aspects of community health interventions. As a result, equity-promoting community health activities were identified as priorities by community members and received funding from the county government for the first time. In this county, the CEC member for health holds advanced public health qualifications, appreciates community health and adopts a ‘power with’ approach to priority-setting, by encouraging discussion and engagement by actors across the health system and community levels.

Meanwhile, in a county with a high burden of NCD CHVs have been trained to screen for and refer patients with hypertension to their closest health facility. The county executive member for health was extremely supportive of community health and had generated political support sharing the concept with the governor and other members of the CEC.

Content of priorities set for community health

We found varied appreciation for community health services by politicians and/or community members, at times depending upon the extent to which they were empowered to understand health holistically (see above). This has led to inconsistent investment in health promotion and disease prevention post-devolution and uneven community health service coverage. This was felt to relate to influential leaders’ appreciation for these services and ability to engage and inform other decision-makers about the benefits and need for community-based health services.

Community health is very advocacy driven. You find the counties that have done well in community health are the ones that have very strong, enthusiastic and well-connected county community health strategy focal person (National Respondent, Female08).

The national role for building capacity and developing policy following devolution is clear. We found, however, that the extent to which counties must follow these directives remains ambiguous. Following revision of the community health strategy in 2014 (after devolution), the lack of clarity surrounding how counties should follow the new national guidance has contributed to differences between the content, quality and functionality of the package of community health services provided between counties. This may potentially widen coverage gaps for pro-equity community health services. Quality gaps often pre-dated devolution and were commonly identified in both health facility and community level services. Respondents, particularly from CHW levels, identified limited refresher training for CHVs, absence of CHV kits and supplies, limited investment in funds to support supervision activities and lack of commensurate recruitment of CHEWs alongside expansion of CHVs (where present).

Implications for health equity and community health

Health equity between counties was felt to have improved (by national key informants and respondents from formerly marginalized counties). Within counties, there is evidence of diversion and dilution of equity perspectives with wide variation in distribution of funds between areas, with some counties attempting to adopt pro-equity distribution which favours poorer and underserved areas. Meanwhile, other counties provide equal distribution of funding regardless of underlying level of need. This is further complicated by local power dynamics, with more powerful politicians found to influence the distribution of investment, typically leading to more infrastructure within their home area, compared with less powerful politicians, regardless of underlying level of need (see Supplementary material).

Devolution provides county authorities an opportunity to push towards context-specific approaches for achieving UHC, by modifying CHV distribution according to population density and/or terrain. In keeping with these ideals, we found examples of local innovation where community health services have been modified according to the local disease burden, for example CHV screening for hypertension in a high NCD burden area (see Box 2). Around half of the counties studied have seized the opportunity devolution presents to invest and/or innovate community health service delivery by expanding coverage and/or providing stipend for CHVs. Meanwhile, the remaining counties have done little more than continue to pay salaries for CHEWs already in post, leading to stagnation or deterioration of these services since devolution. This was typically felt to be related to limited capacity and political preference for infrastructure over health promotion and disease prevention interventions, stunting progress towards equity.

Our problems are mainly in the communities that are in the low income levels. But now, when you look at our budget you find that we want to construct a very big hospital. These people might not even come to this hospital. The issues they have are very basic, maybe even just provision of supply of clean water. You supply clean water, and 50% of their issues are [solved], they don’t need that hospital. So I believe when it comes to equitable distribution, we are not doing that (County Health Respondent, Male30).

In addition to the variation in coverage of community health services there has been limited emphasis on the need for quality services, with many respondents identifying a deterioration in quality since devolution. Only 1 of the 10 study counties identified that improving the functionality of existing community health units was a county priority. The lack of priority for quality community health services was felt to be a consequence of partial adoption of aspects of the revised strategy, with failure to increase the number of CHEWs alongside reducing numbers of CHVs; varied CHV performance, with many CHVs reluctant to work in the absence of receiving a stipend; (although respondents from some counties described county government plans to introduce a CHV stipend); limited county government investment to provide CHVs with refresher trainings or supportive supervision and limited supplies and tools.

Discussion

Devolution in Kenya was politically driven, motivated by the desire to share power and resources across regions, so as to remedy historical inequities, along with objectives to increase citizen participation and accountability (National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General 2010; Cornell and D’Arcy 2014). It appears to have had some positive implications for health equity in previously neglected counties, with increased funding available and expansion of service availability. However, the rapidity of the process, limited technical capacity, guidance, political will for community health and the dominance of powerful county level actors has meant that decision-making and prioritization have been captured for political and power interests, similar to Indonesia’s ‘big-bang’ devolution of the late 1990s (Local Development International 2013). The aim of promoting more equitable and responsive services has not yet been sufficiently realized in the years immediately following devolution. Less visible community health services, including CHWs and health prevention, promotion and referral have often been neglected in the prioritization process. Notable best practice examples (see Box 2), demonstrate several characteristics in contrast to the norms across other counties, and in keeping with Brinkerhoff and Bossert’s (2008) principles for implementing health reforms (Brinkerhoff and Bossert 2008), including: self-identified and driven capacity building for technical priority-setting actors; sharing of priority-setting power with community level actors to generate demand for community health services and political will among political actors.

Context

Kenya’s devolution objectives are in keeping within those commonly described globally, focusing on citizens’ empowerment, promotion of national unity and eradication of inequalities (National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General 2010). These objectives were in part a response seeking to alleviate the effects of structural forces such as colonization, which had led to the ethnocentrism fuelled violence during 2007 elections and the resulting long-standing inequities based on geographic location or tribe (Akoth 2011). Central government have introduced measures which promote the redistribution of funds towards formerly marginalized areas, through the equitable share fund and equalization fund for formerly marginalized counties. Despite these pro-equity efforts, we find that in keeping with two recent Kenyan studies (Cornell and D’Arcy 2014; D’Arcy and Cornell 2016), and across other global contexts (Ramiro et al. 2001; Avelino et al. 2014), patronage norms (which often have tribal associations) have not yet been eradicated within the county, having implications for the availability, use and quality of services by individuals who are most marginalized. Similar to the Philippines (Langran 2011), the Kenyan national Ministry of Health’s role is still in flux, with unclear communication channels and use of incentives or sanctions to guide sub-national priority-setting. Opportunities for national government to encourage county investment in pro-equity community health services, e.g. through conditional grants, could be explored.

Process

In keeping with global literature, our findings highlight that devolution is a process which takes time and needs to be linked to building relevant capacities at subnational levels, and financial resources, with relevant accountability structures and strategies in place to ensure community engagement to address diverse needs and priorities. The rapidity of the process, occurring in a matter of months rather than years as anticipated, has created challenges with ensuring clarity of roles and responsibilities by all actors, and in priority setting, as also noted by Tsofa et al. (2017a,b). Strategic planning was abandoned due to the absence of key actors needed for the planning and budgeting process, followed by budget development by the treasury without the active participation of the department of health and in the absence of an annual workplan (Tsofa et al. 2017b). There is need for a more considered approach to the priority-setting process within devolution, which takes into account the seven principles for priority-setting: stakeholder involvement, stakeholder empowerment, transparency, revisions, use of evidence, enforcement and incorporation of community values (Barasa et al. 2015).

Actors

Our findings are in keeping with those from other devolved settings, where powerful actors can capture the decision-making process, resulting in exclusion of marginalized groups if underlying power structures and norms, such as patronage networks, are not addressed alongside reforms (Kilewo and Frumence 2015). Stronger community empowerment is needed, which addresses these norms by promoting ‘power within’ by disadvantaged community members, and encourages a ‘power with’ expression of power by ‘ordinary’ community actors within priority-setting (VeneKlasen et al. 2002). This will need specific actions to ensure inclusion of ‘disadvantaged groups’, standards placed on local governments and elimination of knowledge imbalances between actors participating in public participation forums. We provide examples of recommendations to strengthen accountability mechanisms in the Supplementary material.

Limited decision-making capacity at sub-national levels is a recognized threat to the success of devolution (Bossert and Beauvais 2002; Langran 2011), constraining ability for effective management and contributing to sub-optimal decisions. We find that limited expertise and leadership capacity at county level has hindered the priority-setting process, in keeping with previous studies (Bossert and Mitchell 2011), which places constraints on their ability to carry-out effective health management and may lead to sub-optimal decisions as occurred in Tanzania and the Philippines (Frumence et al. 2013; Langran 2011; Bossert et al. 2000).

Content

Our findings suggest that equity between counties is improving, with fairer pro-poor funding distribution by central government, who have learnt from other contexts, such as the Philippines, who did not take poverty level into consideration (Langran 2011). Equity within counties, however, is unclear as a lack of sufficient safeguards has in some cases led to replication of the previous centralized government’s norms, discriminations and inequities. Global findings indicate that policymakers seek to direct resources towards the median voter position (Goddard et al. 2006), which may lead to neglect of the public health workforce (Liu et al. 2006) or minority groups, such as those living in sparsely populated nomadic areas (Overseas Development Institute 2016). A strong equity focus is needed, which will expand access and increase demand for context-appropriate community-based promotive, preventive, curative and rehabilitative health, monitoring the needs of disadvantaged groups and coverage of key public health services (e.g. human resources for curative and preventive care) and indicators (e.g. immunization rates). Community health in Kenya continues to be largely externally funded by United Nations agencies, e.g. UNICEF, and partner organizations, even where county governments are investing. This risks exacerbating inequities in community health coverage and gives increased scope for manipulation at all levels, although examples of innovation are emerging (see Box 2).

As respondents have highlighted many of the leading health issues relate to social determinants of health, such as environmental factors relating to availability of clean water and sanitation. There is need for intersectoral collaboration, particularly for health promotion and disease prevention, between health and other departments within the county to address the social determinants of health and reduce citizens exposure to risks for ill health, particularly among ‘vulnerable’ groups. This has implications for the need for collaboration and financial allocation from other sectors. CHWs, positioned at the interface between the community and the health system, are potentially key actors in the process of pursuing UHC both in terms of extending services and as ‘agents of change’ with regard to social determinants as culturally and socially embedded members of their community (R McCollum et al. 2016; Kok et al. 2017). They will require support from their community and health system to enable this (Kok et al. 2016). Since decentralization health facility funds are typically delayed and often are lower than expected, putting additional pressure on the available budget (Nyikuri et al. 2015). Further timely decentralization of funds to the health facility level, providing the scope to address community health issues under the guidance of community health committees could provide the autonomy for the community-based primary health care team, mediated through the CHWs, to address the needs of their catchment community, if the needed capacity and accountability mechanisms are in place.

Limitations

Kenya’s 47 counties are extremely diverse which may limit the generalizability of findings. The selection of 10 study counties tried to ensure diversity in demographic, geographic, social, cultural and economic differences. Interviews were conducted with county leaders across 10 counties, but with health workers in three and community members in two counties due to time and resource constraints, and so findings are not necessarily generalizable across the country. The restructuring and implications for power within priority-setting and at community level will adapt over time. As such, we can only ever present a snapshot of this in a particular time and place. Positionality of the main interviewer as a foreign researcher may have inhibited some respondents from openly sharing their opinions. Conversely, some respondents may have felt less threatened and discussed more. Inclusion of experienced Kenyan co-authors in study design and analysis sought to bring ‘insider’ perspectives to the study. Finally, while our study provides perceptions of equity following devolution, it does not present health equity metrics.

Conclusions

In response to our main research questions, our study revealed a general perception of improving equity between counties, while the potential for deepening inequities within counties has not yet been adequately addressed, since any rapid transition in power carries with it a certain degree of risk that local elites may capture priority-setting processes (Langran 2011). Avenues to understand and incorporate equity issues within priority-setting, such as public participation meetings have been established, but are often under-utilized, with limited opportunity for active participation of members of marginalised groups. As a result, health priorities at times favour political aspirations of leaders, leading to uneven interest and investment in extending community health services for all. Through our observations of sub-national level priority-setting for community health, in the period immediately following devolution we highlight examples of good and inspiring practice (see Box 2), a critique of the main accountability challenges experienced, and recommendations for improved community health services (Supplementary material). Devolution in Kenya is still young—less than four years old. As Kenya moves beyond the years immediately following these reforms, it is important that the challenges revealed by this study are addressed and positive institutional structures, processes and norms are laid down which promote health equity for all Kenyans. Many of the challenges experienced in Kenya have previously been seen elsewhere. Our findings therefore provide lessons for other countries considering or undergoing devolution reforms.

Funding

European Union Seventh Framework Programme ([FP7/2007-2013] [FP7/2007-2011]) under grant agreement number 306090 and was conducted in collaboration with the REACHOUT consortium. REACHOUT is an ambitious 5-year international research consortium aiming to generate knowledge to strengthen the performance of CHWs and other close-to-community providers in promotional, preventive and curative primary health services in low- and middle-income countries in rural and urban areas in Africa and Asia. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union Seventh Framework Programme. This paper is published with the permission of the director, KEMRI.

Ethical approval

The research proposal was approved by Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (Research Protocol 14.007 and Research Protocol 14.044) and Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) (Non-SSC Protocol 469). In addition, approval was received from the National Council for Science and Technology (NACOSTI) (NACOSTI/15/2058/4010).

Supplementary Data

Supplementary data are available at Health Policy and Planning online.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Devolved functions and authority occurred for ‘agriculture, health services, air quality and pollution, cultural activities, transport and infra- structure, animal control, trade development and regulation, planning and development, several educational institutions, the implementation of national policies on natural resources and conservation, public works and services, disaster management and local governance’ (Steeves 2015, p. 461).

References

- Akoth SO. 2011. Challenges of Nationhood: Identities, Citizenship and Belonging under Kenya’s New Constitution, Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Avelino G, Barberia LG, Biderman C.. 2014. Governance in managing public health resources in Brazilian municipalities. Health Policy and Planning 29: 694–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barasa EW, Molyneux S, English M.. 2015. Setting healthcare priorities at the macro and meso levels: a framework for evaluation. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 4: 719–32. http://www.ijhpm.com/article_3096_616.html. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barasa EW, Cleary S, English M.. 2016. The influence of power and actor relations on priority setting and resource allocation practices at the hospital level in Kenya: a case study. BMC Health Services Research 16: 536 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27716185\nhttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC5045638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossert T. 1998. Analysing the decentralisation of health systems in developing countries: decision space, innovation and performance. Social Science and Medicine 47: 1513–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossert TJ. 2015. Empirical studies of an approach to decentralization: “decision space” in decentralized health systems In: Faguet J.-P., Poschl C., eds. Is Decentralisation Good for Development? Perspectives From Academics and Policy Makers. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 277–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bossert TJ, Beauvais JC.. 2002. Decentralization of health systems in Ghana, Zambia, Uganda and the Philippines: a comparative analysis of decision space. Health Policy and Planning 17: 14–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bossert T, Beauvais J, Bowser D.. 2000. Decentralization of health systems: preliminary review of four country case studies. Major Applied Research 6: file:///C:/Users/Aisha/Downloads/m6tp1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Bossert TJ, Mitchell AD.. 2011. Health sector decentralization and local decision-making: decision space, institutional capacities and accountability in Pakistan. Social Science and Medicine 72: 39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkerhoff DW, Bossert TJ.. 2008. Health Governance: Concepts, Experience, and Programming Options http://www.healthsystems2020.org/content/resource/detail/1914/.

- Business Daily, 2013. 14 counties to benefit from Sh3bn equalisation fund. Business Daily http://www.businessdailyafrica.com/14-counties-to-benefit-from-Sh3bn-equalisation-fund/-/539546/1706002/-/13tfrap/-/index.html, accessed 1 June 2016.

- Cheema SG, Rondinelli DA.. 2007. From government decentralization to decentralized governance In: Decentralizing Governance. Emerging Concepts and Practices. Cambridge, MA: The Brookings Intitution Press, 1–20. http://scholar.google.com/scholar? hl=en&btnG=Search&q=intitle: From+Government+Decentralization+to+Decentralized+Governance#0. [Google Scholar]

- Commission on revenue allocation, 2016. Brief on the Second Basis for Equitable Sharing of Revenue Among the County Governments. Commission on Revenue Allocation http://www.crakenya.org/cra-brief-on-the-second-basis-for-equitable-sharing-of-revenue/, accessed 10 October 2016.

- Conyers D. 1983. Decentralization: the latest fashion in development administration? Public Administration and Development 3: 97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Conyers D. 2007. Decentralisation and service delivery: lessons from Sub-Saharan Africa. IDS Bulletin 38: 18–32. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2007.tb00334.x/abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell A, D’Arcy M.. 2014. Plus ça change? County-level politics in Kenya after devolution. Journal of Eastern African Studies 8: 173–91. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/17531055.2013.869073. [Google Scholar]

- D’Arcy M, Cornell A.. 2016. Devolution and corruption in Kenya: everyone’s turn to eat? African Affairs 115: 246–73. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels N, Sabin J.. 2002. Setting Limits Fairly: Can we learn to share medical resources? University Press Scholarship Online. http://www.oxfordscholarship.com.liverpool.idm.oclc.org/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195149364.001.0001/acprof-9780195149364-chapter-4? print=pdf.

- Eaton K, Kaiser K, Smoke P.. 2010. The Political Economy of Decentralization Reforms – Implications for Aid Effectiveness. Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- Faguet J-P, Pöschl C (eds). 2014. Is decentralization good for development? Perspectives from academics and policy makers In: Is Decentralization Good for Development? Perspectives from Academics and Policy Makers. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, 1–25. file:///C:/Users/Rosalind.McCollum/Downloads/1_Faguet & Poschl_revised2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Frumence G, Nyamhanga T, Mwangu M, Hurtig A-K.. 2013. Challenges to the implementation of health sector decentralization in Tanzania: experiences from Kongwa district council. Global Health Action 6: 20983–11. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi? artid=3758520&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goddard M, Hauck K, Smith PC.. 2006. Priority setting in health – a political economy perspective. Health Economics, Policy, and Law 1: 79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HECTA Consulting, 2015. Situation Analysis on the Kenya Community Health Strategy a Technical Reference Document for the Development of the Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, ICF Macro, 2014. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey, Nairobi, Kenya: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR308/FR308.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya National Bureau of Statistics, Society for International Development, 2013. Exploring Kenya’s Inequality, Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Kenya School of Government, The World Bank, 2015. Kenya Devolution. Working Paper 1. Building Public Participation in Kenya’s Devolved Government, Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Kilewo EG, Frumence G.. 2015. Factors that hinder community participation in developing and implementing comprehensive council health plans in Manyoni District, Tanzania. Global Health Action 8: 26461..http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi? artid=4452651&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok MC, Ormel H, Broerse JEW. et al. 2016. Optimising the benefits of community health workers’ unique position between communities and the health sector: a comparative analysis of factors shaping relationships in four countries. Global Public Health 1692 (April): 1–29. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17441692.2016.1174722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kok MC, Broerse JEW, Theobald S. et al. 2017. Performance of community health workers: situating their intermediary position within complex adaptive health systems. Human Resources for Health 15: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langran IV. 2011. Decentralization, democratization, and health: the Philippine experiment. Journal of Asian and African Studies 46: 361–74. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22249661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsky A, Mulaki A, Williamson T, Sullivan Z.. 2015. Political Will for Health System Devolution in Kenya: Insights from Three Counties, Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Martineau T, Chen L. et al. 2006. Does decentralisation improve human resource management in the health sector? A case study from China. Social Science & Medicine 63: 1836–45. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0277953606002668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Local Development International, 2013. The Role of Decentralisation/Devolution in Improving Development Outcomes at the Local Level: Review of the Literature and Selected Cases Prepared for: UK Department for International Development By: Local Development International LLC, (November), 90. http://www.delog.org/cms/upload/pdf/DFID_LDI_Decentralization_Outcomes_Final.pdf.

- Masanyiwa ZS, Niehof A, Termeer CJ.. 2015. A gendered users’ perspective on decentralized primary health services in rural Tanzania. International Journal of Health Planning and Management 30: 285–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollum R, Otiso L, Mireku M. et al. 2016. Exploring perceptions of community health policy in Kenya and identifying implications for policy change. Health Policy and Planning 31: 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCollum R, Gomez W, Theobald S. et al. 2016. How equitable are community health worker programmes and which programme features influence equity of community health worker services? A systematic review. BMC Public Health 16: 1–16. http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-016-3043-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills A. 1990. Health System Decentralization: Concepts, Issues and Country Experience. World Health Organisation, 151 https://books.google.co.uk/books? id=efpfQgAACAAJ. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health [Kenya], World Health Organisation, 2013. Kenya Service Availability and Readiness Assessment Mapping (SARAM) Report, Nairobi, Kenya: https://www.google.com/search? q=MOH.+2013a.+Kenya+Service+ Availability+and+Readiness+Assessment+Mapping+ (SARAM)+Report.+ Nairobi,+ Kenya:+World+ Health+Organization &oq=MOH.+2013a.+ Kenya+Service+Availability+ and+Readiness+ Assessment+Mapping+(SARAM)+Report.+Na. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health [Kenya], 2014a. Ministerial Strategic and Investment Plan July 2014–June 2018, Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health [Kenya], 2014b. Republic of Kenya Strategy for Community Health 2014–2019. Transforming Health: Accelerating the Attainment of Health Goals, Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, 2014. Kenya Household Health Expenditure and Utilisation Survey, Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Medical Services, Ministry of Public Health and Sanitation, 2012. Kenya Health Policy 2012–2030, Nairobi, Kenya: http://www.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/ default/files/country_docs/Kenya/kenya_health_policy_final_draft.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell A, Bossert TJ.. 2010. Decentralisation, governance and health-system performance: “where you stand depends on where you sit.” Development Policy Review 28: 669–91. [Google Scholar]

- Mitton CR. 2002. Priority setting for decision makers: using health economics in practice. The European Journal of Health Economics 3: 240–3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15609149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General, 2010. The Constitution of Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Nyikuri M, Tsofa B, Barasa E. et al. 2015. Crises and resilience at the frontline-public health facility managers under devolution in a sub-county on the kenyan coast. PLoS ONE 10: e0144768–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyikuri MM, Tsofa B, Okoth P. et al. 2017. “We are toothless and hanging, but optimistic”: sub county managers’ experiences of rapid devolution in coastal Kenya. International Journal for Equity in Health 16: 113..http://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-017-0607-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olayo R, Wafula C, Aseyo E. et al. 2014. A quasi-experimental assessment of the effectiveness of the Community Health Strategy on health outcomes in Kenya. BMC Health Services Research 14: S3..http://www.biomedcentral.com/bmchealthservres/content/14/S1/S3 [Accessed June 6, 2014]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overseas Development Institute, 2016. Leaving No One behind in the Health Sector: An SDG Stocktake in Kenya and Nepal, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Prud’homme R. 1995. The dangers of decentralisation. The World Bank Observer 10: 201–20. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/602 551468154155279/pdf/770740JRN0WBRO0Box0377291B00PUBLIC0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Ramiro LS, Castillo FA, Tan-Torres T. et al. 2001. Community participation in local health boards in a decentralized setting: cases from the Philippines. Health Policy and Planning 16: 61–9. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url? eid=2-s2.0-0035704115&partnerID=tZOtx3y1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Republic of Kenya, 2014. Kenya Health Sector Strategic and Investment Plan (KHSSP) 2014–2018, Nairobi, Kenya. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie J, Lewis J (eds). 2003. The foundations of qualitative research Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers, London, California, New Delhi: SAGE publications, 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbold B, Baker R, Ferraz O. et al. 2017. Universal health coverage, priority setting, and the human right to health. The Lancet 390: 712–4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30931-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siekmans K, Sohani S, Kisia J. et al. 2013. Community case management of malaria: a pro-poor intervention in rural Kenya. International Health 5: 196–204. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24030270 [Accessed October 15, 2013]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steeves J. 2015. Devolution in Kenya: derailed or on track? Commonwealth & Comparative Politics 53: 457–74. http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14662043.2015.1089006. [Google Scholar]

- Tanahashi T. 1978. Health service coverage and its evaluation. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 56: 295–303. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsofa B, Goodman C, Gilson L, Molyneux S.. 2017a. Devolution and its effects on health workforce and commodities management – early implementation experiences in Kilifi County, Kenya Lucy Gilson. International Journal for Equity in Health 16: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsofa B, Molyneux S, Gilson L. et al. 2017b. How does decentralisation affect health sector planning and financial management? a case study of early effects of devolution in Kilifi County, Kenya. International Journal for Equity in Health 16: 151..http://equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12939-017-0649-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulenko K, Møgedal S, Afzal MM. et al. 2013. Community health workers for universal health-care coverage: from fragmentation to synergy. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 91: 847–52. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi? artid=3853952&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VeneKlasen L, Miller L (eds). 2002. Power and empowerment In: A New Weave of Power, People and Politics: The Action Guide for Advocacy and Citizen Participation, Oklahoma, USA: World Neighbours, 39–41. http://www.justassociates.org/ActionGuide.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Walt G, Gilson L.. 1994. Reforming the health sector in developing countries: the central role of policy analysis. Health Policy and Planning 9: 353–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.