Abstract

For the past two decades, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) has supported the involvement of patient advocates in both internal advisory activities and funded research projects to provide a patient perspective. Implementation of the inclusion of patient advocates has varied considerably, with inconsistent involvement of patient advocates in key phases of research such as concept development. Despite this, there is agreement that patient advocates have improved the patient focus of many cancer research studies. This commentary describes our experience designing and pilot testing a new framework for patient engagement at SWOG, one of the largest cancer clinical trial network groups in the United States and one of the four adult groups in the NCI’s National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN). Our goal is to provide a roadmap for other clinical trial groups that are interested in bringing the patient voice more directly into clinical trial conception and development. We developed a structured process to engage patient advocates more effectively in the development of cancer clinical trials and piloted the process in four SWOG research committees, including implementation of a new Patient Advocate Executive Review Form that systematically captures patient advocates’ input at the concept stage. Based on the positive feedback to our approach, we are now developing training and evaluation metrics to support meaningful and consistent patient engagement across the SWOG clinical trial life cycle. Ultimately, the benefits of more patient-centered cancer trials will be measured in the usefulness, relevance, and speed of study results to patients, caregivers, and clinicians.

Cancer patients’ involvement in cancer research advocacy started with fundraising for research in the 1930s, evolving over time to include peer support for cancer patients in the 1950s and transitioning to the collective action phase in the 1980s, coincident with the evolution of societal norms supporting rights-based movements (1). Cancer patient advocates have played an important role in influencing cancer clinical trials since the early 1990s, building on lessons learned from HIV/AIDS activists who were dissatisfied with the pace and focus of research for effective therapies. These organized individuals became educated about the science and then challenged traditional research and regulatory norms, arguing that their perspective was valuable and they deserved a seat at the study table, given that they are the ultimate end users of the results. The National Breast Cancer Coalition, founded in 1991, borrowed many of the tactics of the AIDS activists and has effectively lobbied for dedicated funding for breast cancer research, while also training many research advocates to review research proposals and develop studies as members of committees and research teams.

During the same time period, the National Cancer Institute began involving patient advocates in some of their internal groups and funded projects such as the Specialized Program in Research Excellence (SPORE); they officially formed the Office of Liaison Activities in 1996 (now called the Office of Advocacy Relations). Since that time, the role of cancer patient advocates has grown within the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and beyond. Cancer patient advocates are defined as individuals (typically volunteers) who have lived experience with cancer and participate in research teams or committees to provide input from the collective patient perspective to team members regarding research study funding, study topics, study designs, study materials, study execution including accrual, analysis, and dissemination plans.

Rationale for Patient Engagement

The rationale for involving cancer patient advocates in the research process is both normative and pragmatic. Patients bring distinct and important perspectives as members of the study team; for example, ensuring the relevance and prioritization of research questions, success and transparency of research activities, identification of opportunities and barriers to accrual, and dissemination of findings into practice (2). Cancer is a life-threatening disease affecting patients of all ages, with complex treatment choices and profound short- and long-term consequences for patients and families. Clinical trials of novel therapeutic approaches such as precision cancer medicine (3) and immunotherapies are further complicating an already immensely complex landscape of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation treatments. The need for patient and caregiver input into clinical trial design and conduct is widespread and increasing, as there are often no clear best choices.

In addition to studies of new interventions, outcomes research and comparative effectiveness studies evaluate existing treatments and also examine how factors such as health disparities or different cancer care–delivery strategies affect patient outcomes, including survivorship and risk of recurrence. In both explanatory trials and comparative effectiveness studies, patient advocates play a vital role in identifying relevant research questions; alerting researchers to barriers or facilitators to enrollment; characterizing end points that matter to patients and may be differentially impacted by treatment; distinguishing informed consent or data collection issues that are unclear or burdensome; facilitating peer discussions to obtain a collective patient perspective; and assisting with dissemination and implementation of study results.

History of Patient Engagement in NCI Cooperative Group Studies

Patient advocates have been involved with the individual research groups that comprise the National Clinical Trials Network (NCTN) for federally sponsored cancer research in the United States since the 1990s. Numerous examples exist of cancer patient advocates having a positive impact on research team decisions in the context of NCI-supported clinical trials, leading to more patient-centered study designs. For instance, patient advocate input led to revised eligibility criteria for the RxPONDER Trial (4), identification and modification of barriers to accrual in the MATCH trial, and redesign of trial patient information resources for the I-SPY 1 trial (5).

However, patient advocate engagement in NCTN trials during these early years was characterized as developmental and inconsistent (6). In response, formal training programs for advocates were developed that focused on technical knowledge related to cancer, protocol development, and human subjects’ protections. In 2008, the Advocates in Research Working Group of the NCI developed seven recommendations to advance, strengthen, and standardize the engagement of patient advocates in research. Training was highlighted as one of the essential recommendations (7). The training programs reflected studies showing that patient advocates’ knowledge of cancer and cancer research varies widely and their role is not well understood by researchers (8). Subsequently, a survey of patient advocates and researchers within one large NCI clinical trials cooperative group revealed that patient advocates had a more favorable view of their impact on the research process than researchers did, particularly with respect to study concept development, protocol review and development, and assistance with study accrual. Both patient advocates and researchers noted gaps in patient advocates’ knowledge regarding clinical trials, and additional training for advocates was recommended. Notably, both groups highlighted the importance of better communication for effective patient advocate engagement in research and the need for training in advocate-researcher communication skills (9).

Development of a New Patient Engagement Model at SWOG

In response, SWOG—one of the largest cancer clinical trial network groups in the United States and one of the four adult groups on the NCI’s National Clinical Trials Network—increased its efforts to integrate patient-centered research principles into its research development and implementation procedures (10). One of five NCI-designated cancer clinical trials cooperative group networks, SWOG includes nearly 6000 physician researchers at more than 950 institutions nationwide, including 32 of the NCI-designated cancer centers, as well as community hospitals, private practices, and physician group networks.

Patient advocate involvement at SWOG has grown over time. By 2008, at least one patient advocate served on each disease committee. In 2012, the Patient Advocate Committee (PAC) was approved by SWOG’s Board of Governors as a standalone administrative committee. The PAC chair was then invited to serve on the SWOG Executive Committee. Recognizing that the roles, responsibilities, and value proposition of the SWOG patient advocates was not clear to other stakeholders at SWOG, the PAC developed “Ten Key Questions Researchers Should Ask Their Patient Advocate About Their Clinical Trial.” Since 2012, SWOG has initiated a concerted effort to increase patient advocate engagement and value. By 2014, there were 13 patient advocates, primarily focusing on achieving higher accrual and retention rates of participants in clinical trials. As of mid-2017, 19 patient advocates participate in SWOG committees, more than half of whom are survivors of various cancers (breast, colorectal, prostate, kidney, multiple myeloma, bladder, and brain). More than one-third have lived experience with breast cancer as survivors or caregivers/family. Advocates are majority female and white; SWOG has one African American and one Hispanic patient advocate. A cornerstone of SWOG’s long-standing mission is to embrace and encourage diversity in leadership and membership to effectively solve problems in cancer. Diversity across multiple dimensions has become an important factor in the recruitment and selection process for patient advocates, and SWOG is committed to a team that reflects the cancer community it serves.

Prior Process of Patient Engagement in Research Design and Development

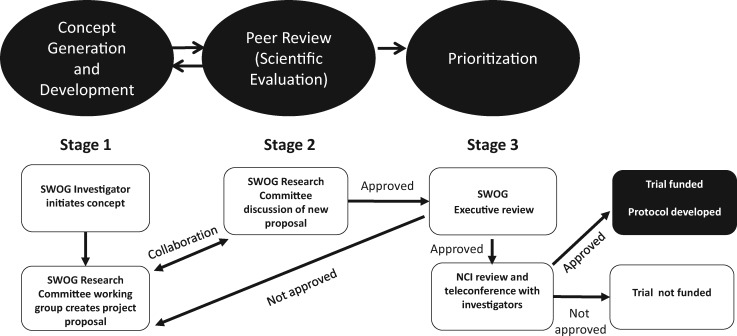

Figure 1 outlines SWOG’s prior process for proposing, developing, and reviewing new protocol ideas within SWOG committees, as well as the National Cancer Institute’s role. In Stage 1 of the process, research ideas initiated by SWOG disease committee researchers are discussed informally with the disease committee chair. If the idea is taken forward, the concept is introduced to other Disease Committee leaders. Leveraging input from the Disease Committee, the researcher writes a Study Concept: a short research proposal, typically referred to as a “capsule.” The capsule typically includes background, study objectives (aims), study plan< statistical analysis and descriptions about concomitant laboratory studies, and potential for financial support. In Stage 2, the fully developed capsule is presented to the disease committee for discussion. Historically, this has been the one point in the research proposal development process where nonclinician stakeholders (eg, statisticians, patient advocates, and study staff) offer comments. Studies that are approved by the research committee chair (frequently conditional on addressing specific issues) are then submitted to SWOG executive members for review.

Figure 1.

SWOG research study generation, review, and approval process. NCI = National Cancer Institute.

The Executive Committee (EC) serves in both a peer review role and a prioritization role, as the members must manage SWOG’s research resources and also identify proposals that are most likely to be approved by the NCI. EC members review capsules and initially provide a score to the group chair (1 = best to 9 = worst) prior to discussing the capsule. After discussion, final scores are tallied, and the capsule is returned to the researcher with one of the following recommendations: “reject,” “revise and resubmit,” or “accept.” Capsules that are accepted are submitted for review by an NCI steering committee. Those that are approved are then developed into full protocols and activated into SWOG’s nationwide network of clinics. Historically, SWOG’s patient advocates neither prepared materials for the EC review nor attended the meeting.

Opportunities and Concerns Regarding Patient Engagement in Clinical Trial Concepts

Starting in January 2014, patient advocates are able to potentially influence the development of study capsules in several ways. For example, the patient advocate assigned to the specific disease committee is typically asked to provide feedback on the proposed capsule prior to submission to the EC. The advocate’s comments are summarized in the form of a SWOG Executive Committee review form that reflects their specific responses to standard questions. The capsule-specific review form is presented to the EC by the PAC vice chair, who is also responsible for addressing study-specific questions. As a voting member of the EC, the PAC vice-chair also has an opportunity to offer another patient advocate perspective. A more detailed description of SWOG’s executive review team and associated research and operational committees is provided on the SWOG website (11); we have also included an organizational chart (Supplementary Figure 1, available online). While opportunities existed for patient advocate feedback, the advocates and much of the leadership in SWOG viewed the process as suboptimal for several reasons. Common concerns included inconsistent involvement of patient advocates, failure to engage early enough to make substantive changes, confusion regarding roles, and lack of structural facilitators (processes, measures, accountabilities) to support meaningful patient advocate engagement across SWOG research committees. Therefore, we developed a structured process to engage patient advocates more effectively in the development of cancer clinical trials. Our experience in engaging the leadership, researchers, protocol coordinators, and patient advocates at SWOG provides a framework for others interested in bringing the patient voice more directly into clinical trial conception and development.

A New Framework for Patient Engagement

Primary Objectives

With funding from the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), we developed and pilot tested a model for patient engagement that focused on the early phase of clinical trial concept development. To maximize the likelihood of successful implementation and sustainability, we modified and adapted existing SWOG processes whenever possible. Our objectives included 1) recruiting and preparing stakeholders; 2) customizing materials to document patient advocate input; and 3) developing procedures and training to support meaningful engagement. These goals were shaped by qualitative interviews conducted with individuals with direct experience with capsule development, including SWOG leadership (disease committee and EC) and patient advocates. For the pilot test, we recruited four research committees—breast, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and cancer care delivery—that had a history of sponsoring a high volume of study capsules, as well as committee chairs and protocol coordinators who were supportive of patient advocate involvement.

Framework

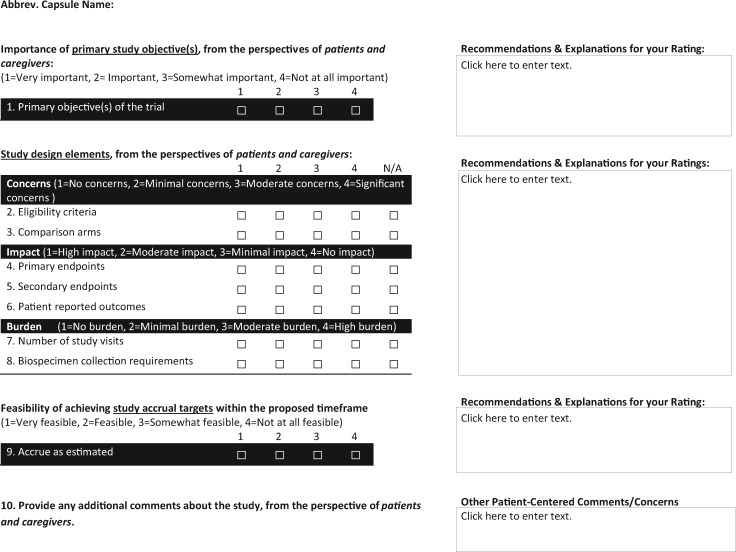

To emphasize that all team members are responsible for ensuring that patient advocates are effectively embedded in the research process, we used the PCORI engagement principles of reciprocal relationships, co-learning, partnership, trust, transparency, and honesty as the foundation for our framework (12). To implement these principles into practice, the research team and selected SWOG leadership representatives focused on standardizing how patient advocates review capsules and provide input to the committee recommendations that are submitted to the EC as part of the capsule review process. To further enhance engagement and specificity, patient advocates were asked to personally present their reviews to the EC. Based on the Population Intervention Comparators Outcomes Timeframe (PICOT) framework (13), the form was developed with input from clinical researchers, protocol coordinators, patient advocates, and SWOG leadership. Each stakeholder made meaningful contributions, and the form underwent several revisions to ensure utility and comprehensibility (Figure 2). A primary purpose of the Patient Advocate Executive Review Form is to facilitate greater involvement of each advocate in capsule development. Patient advocate training videos were developed to support the initial use of this form. In addition, customized versions of the training videos were developed for researchers and protocol coordinators. To meet the demands created by completing this form for every study capsule, SWOG added several new patient advocates to the four disease committees, while also taking advantage of biannual SWOG meetings to raise awareness of the new engagement framework with podium and targeted panel presentations (14–16). The framework was aligned with existing SWOG processes for patient advocate recruitment.

Figure 2.

SWOG patient advocate executive review form.

Early Experience

We developed questionnaires to evaluate the effectiveness of the engagement process from the perspectives of all stakeholders (patient advocates, researchers, committee chairs, and EC members). However, due to the small number of capsules (n = 8) that went through the new engagement model during the pilot test period, our preliminary conclusions are based on qualitative data collected from interviews rather than questionnaire responses. The qualitative interviews focused on assessing the barriers and facilitators to patient advocate engagement in capsule development. For example, interviewees reported that while the importance of patient-engaged research is understood by SWOG leadership, it cannot be assumed to be a universally shared perspective at the level of individual principal researchers and protocol coordinators. Other pilot participants emphasized the need to develop a common understanding of team members’ roles and responsibilities, as well as the steps in the capsule development workflow. Training for all team members (not just patient advocates) regarding collaboration skills within a framework for patient engagement that includes processes and accountabilities were also mentioned as critical success factors. Feedback from pilot participants was generally positive, and the decision was made to expand the new engagement model to all disease and modality committees involved in research at SWOG.

Feedback From SWOG Patient Advocates

Prior to implementing the new framework for patient engagement in capsule development SWOG-wide, we developed a survey to assess the research engagement experience of SWOG patient advocates more broadly. We developed SWOG-specific questions and included modified versions of questions from other PCORI-funded studies focused on enhancing the research advocate role in cancer trials. Questions referred to patient advocate experience during the previous 12 months, a period that included the pilot test period described above. The survey was designed to capture the full life cycle of research engagement from study concept development through results dissemination, reflecting the core value with which patient advocates should be fully engaged throughout the entire research process. We pilot tested the survey with SWOG research advocates and two NCI representatives during the summer of 2016. The survey was approved by the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center Institutional Review Board and administered online from September through November 2016. Nearly all (15 of 16) SWOG advocates completed the survey. Key findings are summarized in Box 1.

Box 1.

SWOG patient advocate survey* key findings summary

-

Engagement is occurring primarily in:

Ensuring study objectives are important to patients

Ensuring procedures are sensitive to real-world patient issues

Helping with study accrual

Engagement is inconsistent across and sometimes within committees

Opportunities to have greater involvement in study concept and protocol development

Very little involvement in trial conduct, results interpretation, publication, and dissemination

-

When engagement occurs, impact is generally observable and positive; areas for improvement:

PI needs to make sure all opinions are considered

More time allocated to discuss relevant issues

-

Patient advocates perceive that, once engaged, their role in the Committee process is clear; areas for improvement:

Need for more clarity on SWOG process and accountability of patient advocates, PIs, and protocol coordinators within the process

Need more consistency regarding process for developing study concept, protocol, and consent form

-

Most common barriers to engagement:

Lack of relationship with PI

Lack of procedures for working with PI

Lack of researcher skills/training for engaging patient advocates

-

Most common facilitators to engagement:

Established relationship with committee

Procedures to support participation in committee

Training to support collaboration as member of team

*Survey consisted of 60 primarily close-ended questions. Domains included patient advocate (PA) demographics; past PA experience; frequency, scope, and quality of engagement experience at SWOG during past 12 months; barriers and facilitators to engagement; training needs. Ninety-four percent response rate—15/16 patient advocates. PI = principal investigator.

The results confirmed that the preponderance of engagement activity between patient advocates and research team members occurs during the early phase of concept development leading up to NCI review. When engagement occurs, the interactions are generally positive. The impact is measured in terms of patient advocate influence on the design of the study as described in the capsule submitted to the EC. For example, study objectives reflect the priorities of patients and caregivers, and study procedures are sensitive to real-world patient concerns (Figure 2). Participants identified opportunities for improvement in the quality and consistency of these interactions across committees (Box 1) and in extending the level of engagement beyond the study concept phase to include study conduct, results interpretation, and dissemination.

Future Directions

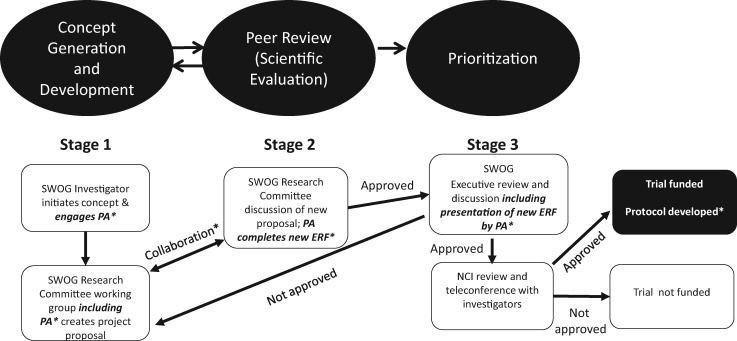

Based on the results of our pilot study of a structured process for patient engagement during the study concept development phase of research at SWOG, as well as the results from the Patient Advocate Engagement Experience Survey, SWOG leadership has implemented this new model for patient advocate engagement in research (Figure 3). Recognizing the opportunity to extend patient engagement beyond study concept development and the importance of training, the research team has secured a PCORI Eugene Washington Award to develop three training modules aligned with the PCORI Engagement rubric, corresponding to study planning, study conduct, and results dissemination. The modules target all members of the study team and focus on collaboration skills. The framework bridges the gap from theory to practice by providing specific downloadable tools that study teams can use to practice and institutionalize new approaches that engage patient advocates in research tasks. These approaches will integrate current and planned efforts to improve diversity and inclusion in the SWOG team and its patient volunteers (17). Accountability for diversity and inclusion efforts now rests with the newly created (December 2016) position of chair of recruitment and retention committee. All patient engagement training efforts will be coordinated with ongoing SWOG training initiatives as we strive to achieve seamless integration with existing and evolving SWOG processes.

Figure 3.

New SWOG researcher-advocate engagement framework. *Training and communication for patient advocate (PA), principal investigator, protocol coordinators, committee, and executive leadership. Expectation that PA will be engaged in all three stages and beyond with enhanced engagement and communication. ERF = Executive Review Form; PA = patient advocate.

While the training will be made available to all SWOG committees that involve patient advocates, the content will be structured so that the SWOG processes and content can be removed and replaced by relevant corollaries from other clinical trials organizations, including SWOG’s counterparts in the NCTN. The goal is to ensure that we model the PCOR engagement principle of bidirectional learning as we share promising practices from our SWOG patient engagement implementation efforts and vice versa.

Measuring Impact on Clinical Trials

The overall goal of developing a more patient-centered approach for developing research questions and capsules is to enhance recruitment of study participants and increase the likelihood of completion of planned enrollment on time or before. By increasing patient engagement in the dissemination phase of cancer research, uptake of evidence into clinical practice will be accelerated and patients will be better prepared to participate in shared decision-making with their clinicians. This result would have a profound effect on whether patients and their families are able to make informed, patient-centered choices about their treatment options.

In the near term, the expected outcome of the training courses is to demonstrate that patient advocates can be engaged meaningfully in SWOG cancer clinical research studies across the research continuum. Outcomes will be assessed by brief evaluations conducted at the end of each training module, which will be targeted to all members of the research team. These evaluations will focus on behavior change and utility of the information in real-world applications. We will utilize the quality of engagement questions from the survey; however, in addition to patient advocates, we will ask PIs, protocol coordinators, and SWOG leadership to provide their perspectives. We will also assess collaboration outcomes for teams using brief surveys, focusing on specific examples of collaboration success.

In practice, the new patient engagement procedures should be judged on their impact on the clinical trials themselves: the quality and acceptance rate of the study capsule proposals by the NCI, uptake of patients during the enrollment period, timing of completion of enrollment relative to prespecified targets, and satisfaction with the trial experience by all stakeholders. Ultimately, the impact of the program can be judged by the impact of the trials on oncology clinical practice.

Conclusions

Patient advocate engagement in cancer research has a long history of many accomplishments. Building on this foundation, we have developed a structured process to ensure that consistent and meaningful patient engagement in cancer research during concept development will lead to more timely and relevant results for patients and caregivers.

Funding

This work was supported by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (ME-1303-5889) and the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health (UG1CA189974).

Notes

Affiliations of authors: American Institutes for Research, Health Group, Chapel Hill, NC (PAD); SWOG Patient Advocate Committee, Portland, OR (RB); Hutchinson Institute for Cancer Outcomes Research, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA (KK, DMD, SDR); Columbia University Medical Center, New York City, NY (DLH); SWOG, OHSU Knight Cancer Institute, Portland, OR (CDB).

The funder had no role in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute or the National Institutes of Health.

All authors except Mr. Bangs report no disclosures. He reports receiving compensation for his roles as an National Cancer Institute (NCI) Patient Advocate and as the co-chair of the NCI Patient Advocate Steering Committee.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Perlmutter J, Bell SK, Darien G.. Cancer research advocacy: Past, present, and future. Cancer Res. 2013;73(15):4611–4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Concannon TW, Fuster M, Saunders T et al. , A systematic review of stakeholder engagement in comparative effectiveness and patient-centered outcomes research. J Gen Int Med. 2014;29(12):1692–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Millner LM, Strotman LN.. The future of precision medicine in oncology. Clinics Lab Med. 2016;36(3):557–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ramsey SD, Barlow WE, Gonzalez-Angulo AM et al. , Integrating comparative effectiveness design elements and endpoints into a phase III, randomized clinical trial (SWOG S1007) evaluating oncotypeDX-guided management for women with breast cancer involving lymph nodes. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;34(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Perlmutter J, Roach N, Smith ML.. Involving advocates in cancer research. Sem Oncol. 2015;42(5):681–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Collyar D. An essential partnership: patient advocates and cooperative groups. Sem Oncol. 2008;35(5):553–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. National Cancer Institute Office of the Director. Advocates in Research Working Group Recommendations. NIH Publication No. 11-7687. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. https://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/ncra/ARWG-recom.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Domecq JP, Prutsky G, Elraiyah T et al. , Patient engagement in research: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Katz ML, Archer LE, Peppercorn JM et al. , Patient advocates' role in clinical trials: Perspectives from Cancer and Leukemia Group B investigators and advocates. Cancer. 2012;118(19):4801–4805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. SWOG. History. https://www.swog.org/Visitors/History.asp. Accessed August 12, 2017.

- 11. SWOG. How we work. https://www.swog.org/swog-network/how-we-work. Accessed January 21, 2018.

- 12. Sheridan S, Schrandt S, Forsythe L, Hilliard TS, Paez KA.. The PCORI engagement rubric: Promising practices for partnering in research. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(2):165–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thabane L, Thomas T, Ye C, Paul J.. Posing the research question: Not so simple. Can J Anesth. 2009;56(1):71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. SWOG. Fall 2015 plenary II (general) session presentations 2015. http://www.swog.org/Visitors/Fall15GpMtg/PlenaryII/Plenary-II-1510.asp. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- 15. SWOG. Fall 2015 group meeting agenda 2015. https://swog.org/Visitors/Fall15GpMtg/Agenda1510.pdf. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- 16. Blanke C. Patient participation improves trials: A preview of Chicago's plenary II 2015. http://www.swog.org/Media/frontline/2015/0731.asp. Accessed August 20, 2017.

- 17. Blanke C. Dr. Elise Cook leads SWOG diversity efforts. https://www.swog.org/news-events/news/2017/11/17/dr-elise-cook-leads-swog-diversity-efforts. Accessed January 21, 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.