Abstract

Background

The efficacy and safety of naldemedine (a peripherally acting µ-opioid receptor antagonist) for opioid-induced constipation (OIC) in subjects with cancer was demonstrated in the primary report of a phase III, double-blind study (COMPOSE-4) and its open-label extension (COMPOSE-5). The primary end point, the proportion of spontaneous bowel movement (SBM) responders, was met. Here, we report results from secondary end points, including quality of life (QOL) assessments from these studies.

Patients and methods

In COMPOSE-4, eligible adults with OIC and cancer were randomly assigned 1:1 to receive once-daily oral naldemedine 0.2 mg (n = 97) or placebo (n = 96) for 2 weeks, and those who continued on to COMPOSE-5 received naldemedine for 12 weeks (n = 131). Secondary assessments in COMPOSE-4 included the proportion of complete SBM (CSBM) responders, SBM or CSBM responders by week, and subjects with ≥1 SBM or CSBM within 24 h postinitial dose. Changes from baseline in the frequency of SBMs or CSBMs per week were assessed at weeks 1 and 2. Time to the first SBM or CSBM postinitial dose was also evaluated. In both studies, QOL impact was evaluated by Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms (PAC-SYM) and PAC-QOL questionnaires.

Results

Naldemedine improved bowel function for all secondary efficacy assessments versus placebo (all P ≤ 0.0002). The timely onset of naldemedine activity versus placebo was evidenced by median time to the first SBM (4.7 h versus 26.6 h) and CSBM (24.0 h versus 218.5 h) postinitial dose (all P < 0.0001). In COMPOSE-4, significant differences between groups were observed with the PAC-SYM stool domain (P = 0.045) and PAC-QOL dissatisfaction domain (P = 0.015). In COMPOSE-5, significant improvements from baseline were observed for overall and individual domain scores of PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL.

Conclusions

Naldemedine provided effective and timely symptomatic relief from OIC and improved the QOL of subjects with OIC and cancer.

Trial registration ID

www.ClinicalTrials.jp: JAPIC-CTI-132340 (COMPOSE-4) and JAPIC-CTI-132342 (COMPOSE-5).

Keywords: opioid-induced constipation, peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonist (PAMORA), naldemedine, cancer, bowel movement, quality of life

Key Message

Once-daily oral naldemedine 0.2 mg provided effective and timely symptomatic relief from opioid-induced constipation in subjects with cancer compared with placebo in a 2-week phase III study. A 12-week extension of the study demonstrated that naldemedine treatment was also associated with an improvement in subjects’ quality of life in this study population.

Introduction

Opioids are recommended for the management of moderate to severe cancer pain [1, 2] and are prescribed to approximately 70% of patients with cancer [3]. The analgesic benefits of opioids can be compromised by side effects, such as opioid-induced constipation (OIC) [4–6]. OIC affects 60%–90% of patients receiving opioids for cancer pain, and its symptoms do not subside with the duration of the therapy [7–9]. Patients with OIC report a significantly worse quality of life (QOL) compared with those who are unaffected [7, 10], and OIC has been correlated to a poorer Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status [11].

OIC is primarily caused by the binding of exogenous opioids to peripheral μ-opioid receptors in the submucosal and myenteric plexuses of the enteric nervous system within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract [6]. The consequent physiological changes result in the characteristic symptoms of OIC: reduced bowel movement (BM) frequency, increased straining, a sensation of incomplete bowel evacuation, and/or hard stool consistency after initiating opioid therapy [6, 12]. Exercise, stimulant laxatives, higher fiber intake, and increased hydration are first-line treatments for OIC; however, they do not target the underlying mechanism of OIC and usually provide inadequate or inconsistent relief [7, 13]. Despite the prevalent use of laxatives, 97% of patients with OIC and cancer report moderate to severe symptoms of constipation [13]. In addition, laxatives introduce side effects that have been found to further diminish patients’ already-poor QOL [14]. Unsurprisingly, despite experiencing an increase in pain, many patients reduce or skip opioid doses in an attempt to induce a BM [7, 14–16]. A cross-sectional survey found that OIC (and other opioid-related GI symptoms) led to the hospitalization of as many as 16% of patients with cancer receiving opioids [17]. Timely and consistent relief from OIC is, therefore, imperative for the effective management of cancer pain and improving overall patient QOL.

Peripherally acting μ-opioid receptor antagonists (PAMORAs) are a class of drugs that aim to reverse OIC without affecting opioid-mediated analgesia. PAMORAs minimally cross the blood–brain barrier and exert their therapeutic benefits by minimizing exogenous opioid actions at peripheral μ-opioid receptors, including the GI tract [18–20]. Naldemedine is a PAMORA developed as a once-daily oral drug for the relief of OIC in patients with cancer or chronic noncancer pain. We previously reported the primary results from a randomized, placebo-controlled, 2-week, phase III study evaluating the efficacy and safety of once-daily oral naldemedine 0.2 mg for OIC in subjects with cancer (COMPOSE-4), as well as its open-label, 12-week extension study (COMPOSE-5) [21]. The primary end point for COMPOSE-4 was met: a greater proportion of spontaneous bowel movement (SBM) responders (defined as those with ≥3 SBMs per week and an increase of ≥1 SBM per week from baseline) was observed with naldemedine versus placebo (71% versus 34%; P < 0.0001) [21]. The primary end point for COMPOSE-5 was safety; naldemedine was generally well tolerated in this study population [21]. As described above, in addition to the assessed primary end points, there are other important clinical challenges that need to be addressed for the effective treatment of OIC. Here, we report select, prespecified secondary efficacy end points from COMPOSE-4 and COMPOSE-5, to further evaluate the efficacy, onset of action, and impact on the QOL of naldemedine treatment in subjects with OIC and cancer.

Methods

Study design and procedures

COMPOSE-4 (JAPIC-CTI-132340) was a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase III study. COMPOSE-4 assessed the efficacy, QOL, and safety of once-daily oral naldemedine 0.2 mg for 2 weeks in subjects with OIC and cancer. COMPOSE-5 (JAPIC-CTI-132342) was an open-label, 12-week extension study that evaluated the safety of naldemedine and its impact on the subjects’ QOL. Both studies were conducted in accordance with the Pharmaceutical Affairs Act, the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines, the Declaration of Helsinki, and with approval from each institutional review board. All subjects provided written informed consent.

Detailed study design and procedures were previously published [21]. Briefly, eligible subjects (aged ≥20 years) with an ECOG performance status ≤2 had cancer that was expected to remain stable throughout the study period. Any cancer type was permissible provided that it did not impact GI function. Subjects were taking a stable daily dose of opioids for cancer pain for ≥2 weeks before screening and had OIC. OIC was defined as ≤5 SBMs (a BM not induced by rescue laxatives) at baseline (2-week period before randomization), and increased straining, incomplete bowel evacuation, and/or hard stools in ≥25% of all BMs [6, 12].

In COMPOSE-4, eligible subjects were randomized 1:1 to receive once-daily oral naldemedine 0.2 mg or placebo for 2 weeks. Subjects who completed COMPOSE-4 had the option to participate in COMPOSE-5 and receive naldemedine 0.2 mg once daily for an additional 12 weeks. If a subject experienced an adverse event that worsened their QOL in COMPOSE-5, a dose reduction to naldemedine 0.1 mg and/or temporary treatment discontinuation (≤2 weeks) was allowed at the discretion of the investigator.

Assessments

The prespecified secondary efficacy end points in COMPOSE-4 included the proportion of complete SBM (CSBM) responders. A CSBM is a BM not induced by rescue laxatives that was accompanied with a sensation of complete bowel evacuation. A CSBM responder was defined as a subject who had ≥3 CSBMs per week and an increase of ≥1 CSBM per week from baseline. The proportion of subjects with an SBM or CSBM response by week, and the change from baseline in the mean frequency, estimated as the least squares mean, of SBMs or CSBMs per week were assessed. The proportions of subjects with ≥1 SBM or ≥1 CSBM within 4, 8, 12, and 24 h of the initial dose of the study drug, and the median time to the first SBM or CSBM were also analyzed.

Subjects in COMPOSE-4 and COMPOSE-5 answered the questionnaires of Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms (PAC-SYM [22]) and -QOL (PAC-QOL [23]). The overall PAC-SYM score comprised three domains: abdominal, rectal, and stool symptoms. The overall PAC-QOL score consisted of four domains: physical discomfort, psychosocial discomfort, satisfaction, and worries and concerns. A lower score indicated a better outcome for symptomatic relief and QOL. In COMPOSE-4, the questionnaires were answered predose on day 1 and on day 15. In COMPOSE-5, the questionnaires were answered on day 1 (day 15 of COMPOSE-4) and days 15, 29, 57, and 85. Both PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL questionnaires have a validated 2-week recall period [22–24]. In COMPOSE-4, subgroup analyses of the mean overall PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL scores were performed in subjects who had baseline scores ≥1 for each assessment, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Detailed sample size calculations were previously published [21]. Efficacy analyses were performed on the FAS, which included all randomized subjects in COMPOSE-4 who had ≥1 dose of the study drug after evaluating BMs at baseline, and ≥1 evaluation of BMs postdose. In COMPOSE-5, the FAS included all subjects who additionally had completed PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL assessments at baseline, and had ≥1 evaluation postdose.

For all two-sided tests, a statistical significance level was set at 0.05. For all secondary efficacy end points, the chi-square test was used to compare differences between treatment groups, except for change from baseline in the frequency of SBMs or CSBMs per week (analyzed by mixed model repeated measures), and time to the first SBM or CSBM postinitial dose of study drug (analyzed using Kaplan–Meier estimates and generalized Wilcoxon tests). Welch’s t-tests were used to compare differences between treatment groups and change from baseline in mean PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL scores. All 95% confidence intervals for proportion were calculated using the Clopper–Pearson method.

Results

Subjects

In COMPOSE-4, 193 eligible subjects were randomized to receive naldemedine (n = 97) or placebo (n = 96) between 21 November 2013 and 6 March 2015. Of the 171 subjects who completed COMPOSE-4, 131 subjects chose to enter COMPOSE-5 between 7 December 2013 and 26 December 2014 to receive open-label naldemedine [supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online (CONSORT diagram)]. Baseline characteristics were similar between treatment groups in COMPOSE-4. The baseline characteristics of the subjects who entered COMPOSE-5 were similar across studies (Table 1).

Table 1.

Subject demographic and baseline characteristics [FAS; mean (SD), unless otherwise specified]

| Parameter | COMPOSE-4 |

COMPOSE-5 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Naldemedine | Placebo | Naldemedine | |

| n = 97 | n = 96 | n = 131 | |

| Age, years | 63.8 (9.4) | 64.6 (11.8) | 63.5 (10.4) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 59 (60.8) | 60 (62.5) | 74 (56.5) |

| Female | 38 (39.2) | 36 (37.5) | 57 (43.5) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |||

| 0 | 28 (28.9) | 33 (34.0) | 43 (32.8) |

| 1 | 55 (58.8) | 49 (51.0) | 71 (54.2) |

| 2 | 14 (14.4) | 14 (14.6) | 17 (13.0) |

| Primary tumor, n (%) | |||

| Lung | 42 (43.3) | 45 (46.9) | 51 (38.9) |

| Breast | 22 (22.7) | 17 (17.7) | 29 (22.1) |

| Large intestine | 3 (3.1) | 3 (3.1) | 5 (3.8) |

| Other | 30 (30.9) | 31 (32.3) | 46 (35.1) |

| Daily dose of opioids,a mg | 57.3 (46.4) | 69.5 (99.5) | 64.0 (80.8) |

| Prior use, n (%) | |||

| Anticancer drugs | 72 (74.2) | 62 (64.6) | 93 (71.0) |

| Routine laxativesb | 72 (74.2) | 74 (77.1) | 98 (74.8) |

| Rescue laxativesc | 93 (95.9) | 89 (92.7) | 126 (96.2) |

| SBM frequency/week | 1.01 (0.76) | 1.10 (0.85) | 0.98 (0.80) |

| CSBM frequency/week | 0.52 (0.64) | 0.48 (0.67) | – |

| PAC-SYM scores | |||

| Overall | 1.06 (0.60) | 1.15 (0.62) | 1.13 (0.58) |

| Abdominal symptoms | 0.99 (0.67) | 1.07 (0.66) | 1.03 (0.64) |

| Rectal symptoms | 0.64 (0.73) | 0.64 (0.68) | 0.66 (0.68) |

| Stool symptoms | 1.38 (0.81) | 1.52 (0.89) | 1.48 (0.84) |

| PAC-QOL scores | |||

| Overall | 1.22 (0.51) | 1.31 (0.60) | 1.27 (0.54) |

| Physical discomfort | 1.08 (0.67) | 1.15 (0.69) | 1.13 (0.66) |

| Psychological discomfort | 0.55 (0.51) | 0.71 (0.63) | 0.66 (0.54) |

| Worries and concerns | 1.12 (0.68) | 1.20 (0.77) | 1.16 (0.73) |

| Dissatisfaction | 2.60 (0.73) | 2.63 (0.73) | 2.62 (0.72) |

Oral morphine-equivalents.

Subjects were routinely using laxatives at the start of the screening period.

Subjects who received rescue laxatives when needed.

CSBM, complete spontaneous bowel movement; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; FAS, full analysis set; PAC-QOL, Patient Assessment of Constipation-Quality of Life; PAC-SYM, Patient Assessment of Constipation-Symptoms; SBM, spontaneous bowel movement; SD, standard deviation.

Efficacy

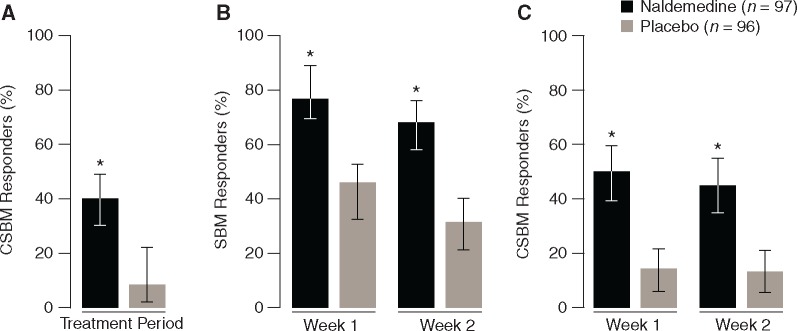

Consistent with the primary end point of SBM responders for COMPOSE-4 [21], a significantly greater proportion of CSBM responders was observed with naldemedine versus placebo during the 2-week treatment period (40.2% versus 12.5%; P < 0.0001; Figure 1A). Significantly greater proportions of SBM and CSBM responders by week were also observed with naldemedine versus placebo (all P < 0.0001; Figure 1B and C). At week 1, a significantly greater change from baseline was observed for the frequency of SBMs/week with naldemedine versus placebo (5.70 versus 1.73; P < 0.0001); similar results were observed on week 2 (3.97 versus 1.24; P < 0.0001). Furthermore, a greater change from baseline in the frequency of CSBMs/week was observed with naldemedine versus placebo for week 1 (3.13 versus 0.60; P < 0.0001) and week 2 (2.11 versus 0.74; P = 0.0002).

Figure 1.

The proportion of CSBM responders over the 2-week treatment period (A), the proportion of SBM responders by week (B), and the proportion of CSBM responders by week (C) in COMPOSE-4 (proportion ± 95% CI; FAS). *P < 0.0001 versus placebo. CI, confidence interval; CSBM, complete spontaneous bowel movement; FAS, full analysis set; SBM, spontaneous bowel movement.

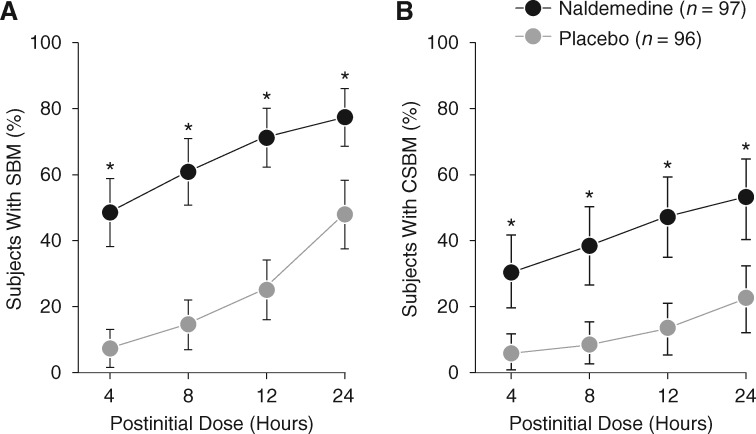

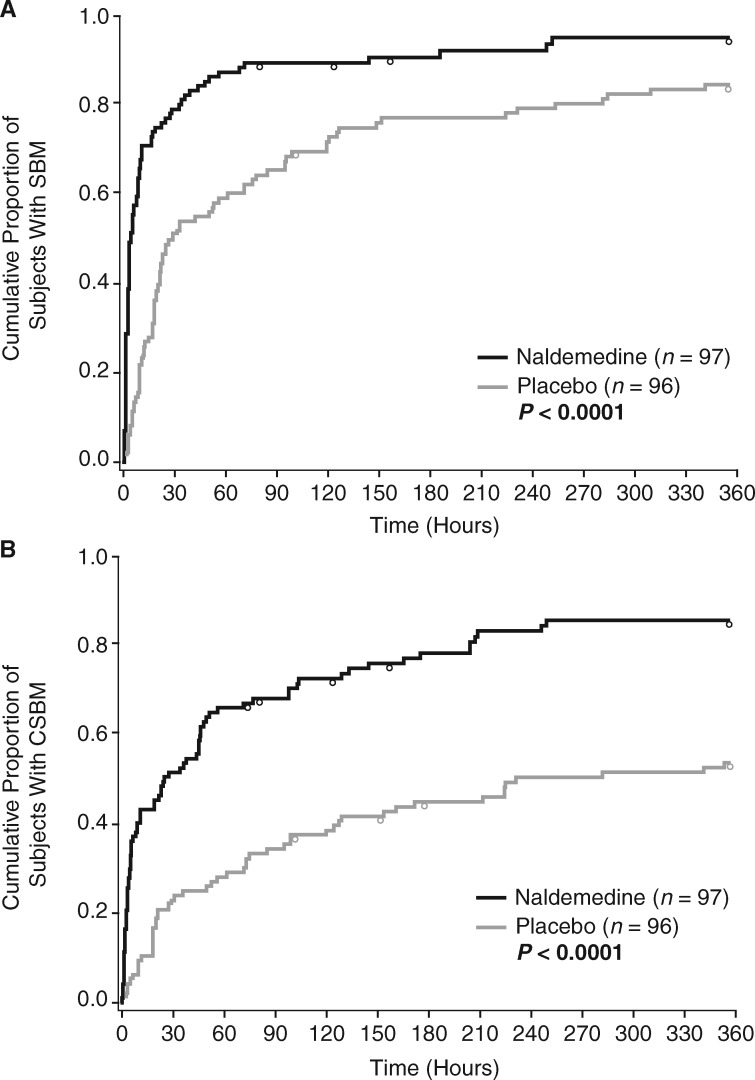

Within 4 h after the initial dose of naldemedine, a significantly greater proportion of subjects had ≥1 SBM or CSBM versus placebo. This effect was maintained at 8, 12, and 24 h postinitial dose (all P < 0.0001; Figure 2). The timely onset of relief from OIC with naldemedine versus placebo was further shown by analysis of median time to the first SBM (4.7 h versus 26.6 h) or CSBM (24.0 h versus 218.5 h) after the initial dose (all P < 0.0001; Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Proportion of subjects with ≥ 1 SBM (A) or ≥ 1 CSBM (B) at specific time points within 24 h after the initial dose of the study drug in COMPOSE-4 (proportion ± 95% CI; FAS). *P < 0.0001 versus placebo. CI, confidence interval; CSBM, complete spontaneous bowel movement; FAS, full analysis set; SBM, spontaneous bowel movement.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curve of time to first SBM (A) or CSBM (B) in COMPOSE-4 (FAS). Circles represent censored time. The time to the first SBM or CSBM was censored for subjects who withdrew from the study before an SBM or CSBM was observed, or if no SBM or CSBM occurred during the 2-week treatment period. CSBM, complete spontaneous bowel movement; FAS, full analysis set; SBM, spontaneous bowel movement.

Quality of life

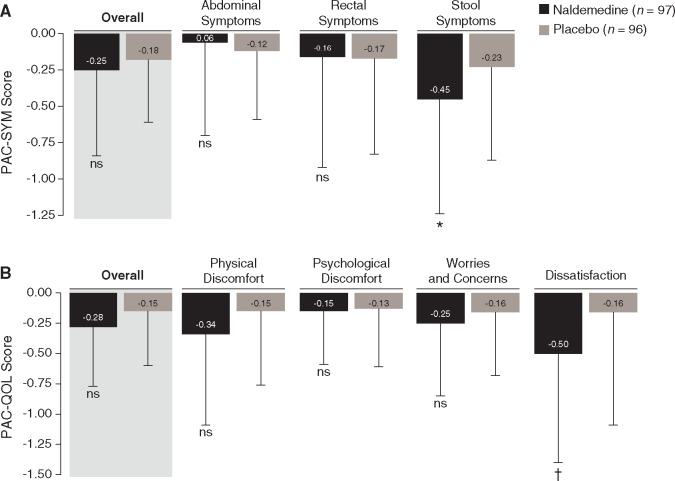

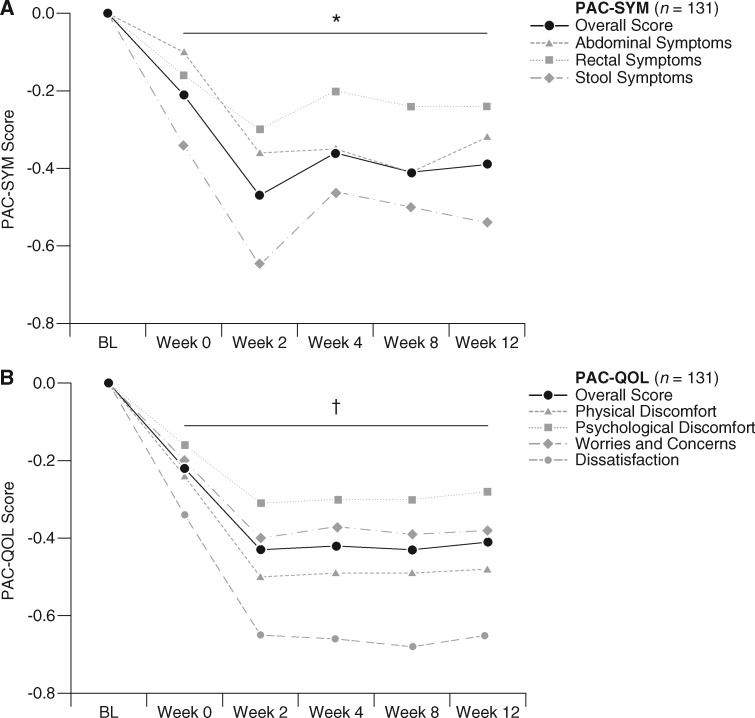

In COMPOSE-4, there were no significant changes from baseline to day 15 with naldemedine versus placebo in the mean overall scores for PAC-SYM (−0.25 versus −0.18, P = 0.36; Figure 4A) or PAC-QOL (−0.28 versus −0.15; P = 0.08; Figure 4B). Significant improvements with naldemedine versus placebo were observed with scores for the PAC-SYM stool domain (–0.45 versus –0.23; P = 0.045; Figure 4A) and the PAC-QOL dissatisfaction domain (–0.50 versus –0.16; P = 0.015; Figure 4B). In COMPOSE-5, naldemedine treatment was associated with a significant improvement from baseline in the mean overall scores of PAC-SYM (Figure 5A) and PAC-QOL (Figure 5B) at all assessed time points (all P < 0.0001). Significant improvements from baseline to all assessed time points were also observed for scores of every individual domain of PAC-SYM (all P ≤ 0.03; Figure 5A) and PAC-QOL (all P ≤ 0.0001; Figure 5B).

Figure 4.

Change from baseline to day 15 of COMPOSE-4 in PAC-SYM (A) and PAC-QOL (B) overall scores and scores for each domain [mean (SD); FAS]. *P = 0.045 versus placebo. †P = 0.015 versus placebo. FAS, full analysis set; ns, not significant; PAC-QOL, Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life; PAC-SYM, Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 5.

Change from baseline (predose on day 1 of COMPOSE-4) over time in PAC-SYM (A) and PAC-QOL (B) overall scores and scores for each domain in COMPOSE-5 (mean; FAS). *P ≤ 0.03 versus BL for mean overall scores and scores for each domain of PAC-SYM. †P ≤ 0.0001 versus BL for mean overall scores and scores for each domain of PAC-QOL. BL, baseline; FAS, full analysis set; PAC-QOL, Patient Assessment of Constipation Quality of Life; PAC-SYM, Patient Assessment of Constipation Symptoms.

In COMPOSE-4, subgroup analysis of subjects who had overall PAC-SYM scores ≥ 1 at baseline (naldemedine, n = 52; placebo, n = 57) showed greater, although marginally insignificant, improvements from baseline to day 15 in overall PAC-SYM scores with naldemedine versus placebo (–0.54 versus –0.35; P = 0.0857; supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). In the subset of subjects who had overall PAC-QOL scores ≥ 1 at baseline (naldemedine, n = 63; placebo, n = 66), significantly greater improvements from baseline to day 15 in overall PAC-QOL scores with naldemedine versus placebo were observed (–0.41 versus –0.21; P = 0.0446; supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Discussion

The primary report of COMPOSE-4 demonstrated that naldemedine treatment in subjects with OIC and cancer results in a significantly greater proportion of SBM responders compared with placebo [21]. Further, in COMPOSE-5, naldemedine was well tolerated for up to 14 weeks in this study population. Here, we confirm and extend the aforementioned findings: naldemedine elicited a greater response compared with placebo in all secondary efficacy assessments and had a timely onset of symptomatic relief from OIC. Moreover, treatment with naldemedine for 12 weeks had a positive impact on subjects’ QOL.

In either group or study, subjects had approximately 1 SBM/week at baseline, an observation consistent with previously reported findings in patients with OIC and cancer [13]. This suggests that patients could suffer for up to 1 week without relief from the symptoms and psychological burden of OIC. Our results indicate that treatment with naldemedine provides timely symptomatic relief from OIC. Moreover, as previously reported, treatment with naldemedine did not impact assessments of pain intensity or precipitate any signs or symptoms of opioid withdrawal in this study population [21]. The timely relief associated with naldemedine treatment could, therefore, potentially contribute toward improving adherence to an opioid regimen and, consequently, the better management of cancer pain.

Treatment with naldemedine for 2 weeks did not significantly improve mean overall scores for PAC-SYM or PAC-QOL compared with placebo. In the extension study, however, significant improvements from baseline were observed in the overall mean scores for both PAC-SYM and PAC-QOL. The discrepancy between the studies on patient-reported outcomes of QOL may partly be due to differences in statistical comparisons. In COMPOSE-4, comparisons were made between treatment groups, whereas in COMPOSE-5, comparisons were made to baseline. Moreover, subgroup analyses in COMPOSE-4 suggest there may be greater improvements in the QOL assessments in subjects who had higher scores at baseline. In both studies, naldemedine significantly improved the PAC-SYM stool domain and PAC-QOL dissatisfaction domain versus placebo (COMPOSE-4) or baseline (COMPOSE-5). Interestingly, these domains reflect the main complaints reported by subjects with OIC: incomplete, hard, and/or small BMs that require increased straining and dissatisfaction with current treatments [13, 25]. Together, our results suggest that naldemedine positively impacts the QOL of patients with OIC and cancer; however, further evaluation in larger patient populations and longer-term studies are warranted.

Limitations to these studies include the lack of racial diversity in the study population, and representation of only a few subjects with an ECOG performance status of 2, or GI cancers. Furthermore, COMPOSE-5 was a single-arm, open-label study and thus, could be associated with inherent bias when assessing patient-reported outcomes.

Currently, two PAMORAs—methylnaltrexone bromide and naloxegol—are approved for the treatment of OIC [7, 12, 26–30]. To our knowledge, the existing literature lacks prospective data on whether treatment with any PAMORA could improve the QOL of subjects with OIC and cancer. We believe the QOL assessments from COMPOSE-4, together with the robust and significant improvements observed in COMPOSE-5, are the first to demonstrate the benefits of a PAMORA in improving the QOL of subjects with OIC and cancer. In conclusion, our results indicate that once-daily, oral naldemedine 0.2 mg significantly improves BM function in a timely manner, and positively impacts the QOL of subjects with OIC and cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

Editorial assistance was provided by V. Ruvini Jayasinghe, PhD, of Oxford PharmaGenesis, Inc., Newtown, PA, USA.

Funding

Shionogi & Co., Ltd (no grant number applies).

Disclosures

NK has received funding from Shionogi & Co., Ltd. NB has received honoraria from Shionogi & Co., Ltd. TY, MA, and YT are employees of Shionogi & Co., Ltd. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief: with a guide to opioid availability, 2nd edition, 1996; http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s22085en/s22085en.pdf (13 March 2017, date last accessed).

- 2. Caraceni A, Hanks G, Kaasa S. et al. Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. Lancet Oncol 2012; 13(2): e58–e68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Plante GE, VanItallie TB.. Opioids for cancer pain: the challenge of optimizing treatment. Metabolism 2010; 59: S47–S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Poulsen JL, Brock C, Olesen AE. et al. Evolving paradigms in the treatment of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2015; 8(6): 360–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S. et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician 2008; 11: S105–S120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Camilleri M, Drossman DA, Becker G. et al. Emerging treatments in neurogastroenterology: a multidisciplinary working group consensus statement on opioid-induced constipation. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014; 26(10): 1386–1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bell TJ, Panchal SJ, Miaskowski C. et al. The prevalence, severity, and impact of opioid-induced bowel dysfunction: results of a US and European Patient Survey (PROBE 1). Pain Med 2009; 10(1): 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tuteja AK, Biskupiak J, Stoddard GJ, Lipman AG.. Opioid-induced bowel disorders and narcotic bowel syndrome in patients with chronic non-cancer pain. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2010; 22(4): 424–430. e96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bruner HC, Atayee RS, Edmonds KP, Buckholz GT.. Clinical utility of naloxegol in the treatment of opioid-induced constipation. J Pain Res 2015; 8: 289–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hatswell AJ, Vegter S.. Measuring quality of life in opioid-induced constipation: mapping EQ-5D-3 L and PAC-QOL. Health Econ Rev 2016; 6(1): 14.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fallon MT, Hanks GW.. Morphine, constipation and performance status in advanced cancer patients. Palliat Med 1999; 13(2): 159–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lacy BE, Mearin F, Chang L. et al. Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(6): 1393–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coyne KS, Sexton C, LoCasale RJ. et al. Opioid-induced constipation among a convenience sample of patients with cancer pain. Front Oncol 2016; 6: 131.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Emmanuel A, Johnson M, McSkimming P, Dickerson S.. Laxatives do not improve symptoms of opioid-induced constipation: results of a patient survey. Pain Med 2016; pnw240. doi: 210.1093/pm/pnw1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Epstein RS, Cimen A, Benenson H. et al. Patient preferences for change in symptoms associated with opioid-induced constipation. Adv Ther 2014; 31(12): 1263–1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gupta S, Patel H, Scopel J, Mody RR.. Impact of constipation on opioid therapy management among long-term opioid users, based on a patient survey. J Opioid Manage. 2015; 11(4): 325–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abramowitz L, Beziaud N, Labreze L. et al. Prevalence and impact of constipation and bowel dysfunction induced by strong opioids: a cross-sectional survey of 520 patients with cancer pain: DYONISOS study. J Med Econ 2013; 16(12): 1423–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weber HC. Opioid-induced constipation in chronic noncancer pain. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2016; 23(1): 11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Brenner DM, Chey WD.. An evidence-based review of novel and emerging therapies for constipation in patients taking opioid analgesics. Am J Gastroenterol Suppl 2014; 2(1): 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Diego L, Atayee R, Helmons P. et al. Novel opioid antagonists for opioid-induced bowel dysfunction. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2011; 20(8): 1047–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Katakami N, Harada T, Murata T. et al. Randomized phase III and extension studies of naldemedine in patients with opioid-induced constipation and cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(34): 3859–3866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Slappendel R, Simpson K, Dubois D, Keininger DL.. Validation of the PAC-SYM questionnaire for opioid-induced constipation in patients with chronic low back pain. Eur J Pain 2006; 10(3): 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Marquis P, De La Loge C, Dubois D. et al. Development and validation of the patient assessment of constipation quality of life questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol 2005; 40(5): 540–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Frank L, Kleinman L, Farup C. et al. Psychometric validation of a constipation symptom assessment questionnaire. Scand J Gastroenterol 1999; 34: 870–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coyne KS, Margolis MK, Yeomans K. et al. Opioid-induced constipation among patients with chronic noncancer pain in the United States, Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom: laxative use, response, and symptom burden over time. Pain Med 2015; 16(8): 1551–1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Relistor (methylnaltrexone bromide) [prescribing information]. Progenics Pharmaceuticals, Tarrytown, NY, 2016.

- 27.Relistor 12 mg/0.6 mL solution for injection [summary of product characteristics]. PharmaSwiss, Czech Republic, January 2017.

- 28. Viscusi ER, Barrett AC, Paterson C, Forbes WP.. Efficacy and safety of methylnaltrexone for opioid-induced constipation in patients with chronic noncancer pain: a placebo crossover analysis. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2016; 41(1): 93–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chey WD, Webster L, Sostek M. et al. Naloxegol for opioid-induced constipation in patients with noncancer pain. N Engl J Med 2014; 370(25): 2387–2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thomas J, Karver S, Cooney GA. et al. Methylnaltrexone for opioid-induced constipation in advanced illness. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(22): 2332–2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.