Abstract

Sophistication in DNA and RNA sequencing technology is unraveling the tremendous genetic and molecular complexity of human cancer. However, the rate at which this knowledge is being translated into patient care is too slow. To this end, we have designed and implemented a new translational platform, “The Co-Clinical Trial Project”, where data obtained in genetically engineered mouse models of human cancer treated with the identical protocols of on-going clinical trials or established therapies in patients serve to rapidly: (i) stratify patients in terms of response and resistance on the basis of genetic and molecular criteria; (ii) identify mechanisms responsible for tumor resistance; and (iii) evaluate the effectiveness of drug combinations to overcome such resistance based on mechanistic understanding.

Keywords: GEMM, Mouse Hospital, Patients stratification, Treatment optimization

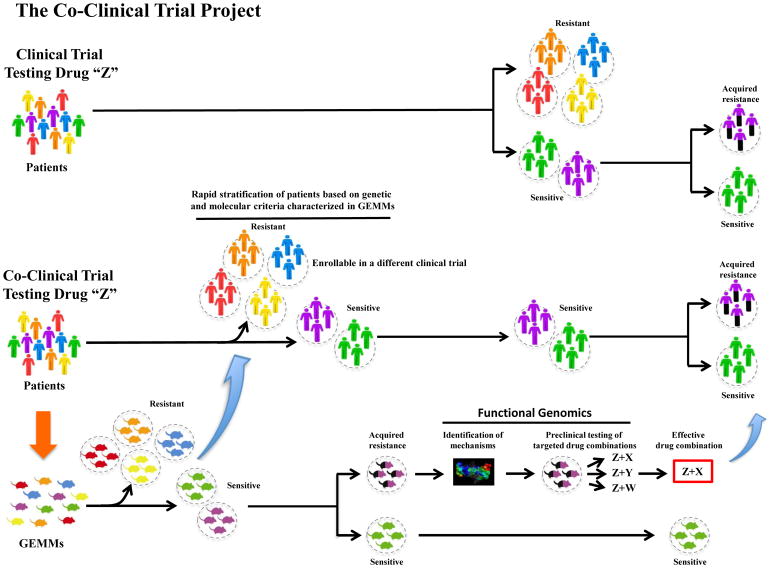

Tumor heterogeneity: a major hurdle

The first decade of the 21th century has seen unprecedented progress in our understanding of the complexity of cancer. New sequencing technologies have unravelled much of the tapestry of inter- and intra-tumor genetic heterogeneity, with the non-coding space of the transcriptome playing an unpredictable, yet key, new role [1–7]. Although these insights have deepened our understanding of the molecular mechanisms characterizing this pandemic disease, they have also generated a sense of bewilderment among scientists and physicians in the field of translational medicine. These insights have made the identification of real oncogenic “hubs” involved in the tumorigenic process and response to therapy a constantly moving, yet ever-more-essential, target. To disentangle, and finally profit by, the incredible amount of genetics and molecular information available, we decided to completely revise the traditional bench-to-bedside translational approach by conceiving and developing the “Co-Clinical Trial Project” [8]. The Co-clinical Trial Project takes advantage of faithful genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs), which mirror human tumor heterogeneity, to direct on-going clinical studies in patients (Figure 1). By treating mice with precisely the same clinical protocols as patients enrolled in clinical trials, and sharing in real time the resulting information, the Co-Clinical Trial approach can greatly shorten the gap between preclinical study and patient care through: (i) the rapid stratification of patient sensitivity and resistance to a specific treatment on the basis of molecular and genetics criteria; (ii) the characterization of mechanisms dictating de novo or acquired tumor resistance to therapy; and (iii) the use of this platform as a testing ground for new drug combinations (Figure 1) [8].

Figure 1. The Co-clinical Trial platform.

In the Co-Clinical Trial project, relevant genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) and human patients are treated with the same drug and clinical protocol. Integrated analysis of data accrued in GEMMs and patients serve to stratify response and resistance on the basis of molecular and genetics criteria. Mechanisms underlying acquired resistance are also rapidly identified, and drug combinations to overcome such resistance are easily tested in GEMMs for their effectiveness.

The Co-Clinical Trial Project was conceived from the realization of the power of preclinical testing of new drugs, novel drug combinations, and novel therapeutic modalities in faithful GEMMs of human cancer. Indeed, the use of GEMMs in translational research has already been fundamental to the eradication of a lethal form of cancer, PML-RARα driven acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) [8]. However, while the classical preclinical approach of that achievement took approximately twenty years, initial Co-Clinical studies in prostate and lung cancers have already shown promising results in less than three.

Acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL): pioneering GEMMs of human cancer in translational medicine

APL cells are characterized by a reciprocal and balanced chromosomal translocation involving chromosome 17 associated with the block at the promyelocytic stage of the myeloid lineage differentiation [9]. In 1991, the two genes involved in the t(15;17) translocation were identified as PML (15q22) and RARα (17q211) [10]. Later, however, it became clear that APL is not a single disease genetically, but many (e.g. PLZF- RARα t(11;17); NUMA-RARα; NPM-RARα; STAT5b-RARα) [11], and that different genetic lesions were responsible for both the specific biologies of the disease and differing response to treatments [12, 13].

Critically, the generation of faithful GEMMs for most of the different subtypes of APL demonstrated for the first time the reliability of GEMMs for translational studies. PML-RARα mice, for instance, are responsive to Retinoic Acid (RA), but frequently experience leukemic relapse if RA is used as a single agent, mirroring closely the results in human t(15;17) APL patients [12]. Likewise PLZF-RARα driven APL in mice was found to be de novo resistant to RA, as it was in human t(11;17) APL [12].

A key aspect of the role played by GEMMs in the APL saga was the opportunity they provided to test the efficacy of novel drug combinations by enrolling, in randomized preclinical trials, the different APL mouse models, an effort impossible to sustain through classical clinical trials due to the limiting number of APL patients for each molecular subtype. The preclinical studies in GEMMs demonstrated that in RA-sensitive PML-RARα mouse models of APL, the combination of RA and As2O3 was curative, while once again PLZF-RARα APL was resistant at presentation [14, 15]. On the other hand, the RA-resistant PLZF-RARα mouse model of APL was found to be sensitive to the combination of RA and histone deacetylase inhibitors [16, 17]. These results overwhelmed resistance in the scientific and clinical oncology community to the use of GEMMs in translational research, and prompted the enrollment of PML-RARα APL patients in a successful world-wide clinical trial with the As2O3 + RA combination, which finally proved curative for RA-sensitive APL [18].

But it took us 20 years.

The Co-Clinical Trial project: pushing the system forward

The APL saga perfectly summarizes a typical bedside-to-bench-to-bedside journey, starting with the cloning of the APL fusion genes, generation and use of faithful GEMMs that proved instrumental in understanding the tumorigenic process, stratifying the response to specific treatments on genetic and molecular criteria, and, finally, informing and optimizing clinical trials in PML-RARα APL patients that led to its cure. Retrospectively, however, a criticism that could be leveled at this amazing journey is that data from the mouse studies were brought to the attention of the clinicians only when they were completed, ultimately slowing down the rate of progress. Thus, although the APL saga is the inspiration for the “Co-Clinical Trial Project”, the project aims to go beyond the APL journey and revolutionize the classical pre-clinical/clinical setting by sharing in real time results from bench-to-bedside-to-bench, in turn quickly defining tumor response or resistance to treatment on genetic and molecular criteria, speeding patient stratification on that basis, and finally predicting the efficacy of new drug combinations in overcoming tumor resistance [8].

The mouse hospital

Two critical factors to a successful Co-Clinical Trial are: the enrollment of mice in an identical protocol to that applied to patients, and a precise and continuous flux of data from bedside to bench and back. In order to achieve these two fundamental pillars, we set-up the Mouse Hospital, a state-of-the-art animal facility staffed by experts in mouse care, husbandry, treatments, and surgery, with access to procedure rooms and small-animal in vivo imaging technologies (bioluminescence, magnetic resonance imaging; micro-computed tomography; micro-positron emission tomography; ultrasonogram; fluorescence-mediated tomography), as well as instruments for blood and urine tests, all of which are fundamental to determining the local and systemic tumor responses to treatments in GEMMs and perfectly mirror standard clinical protocols adopted in patients [8]. Equally important, and essential to the sharing and comparison of mouse data across different mouse hospitals and human clinics, is the attention of each operator to precise and standardized procedures in mouse handling. The most common standards of practice regarding the use of mouse models in translational studies are now described in essays collectively reported in the Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory publication “Mouse Models of Cancer: A Laboratory Manual,” which can easily be found on PubMed. This manual also provides a description of different methods for generating and characterizing mouse models that recapitulate many aspects of human cancer. These include cutting-edge strategies for the generation of genetically engineered mouse models, techniques of tissue recombination, organ reconstitution, and transplantation methods to develop chimeric, allograft, and xenograft models, as well as state-of-the-art imaging, histopathological, surgical, and other approaches to study tumor onset, progression, and metastasis. Finally, specific chapters are dedicated to the use of mouse models for drug testing and combinational treatment optimization in pre- and co-clinical trials in order to comprehensively and correctly integrate mouse and human clinical data. With the Mouse Hospital and Standard of Practices (SOPs) as founding elements, the Co-Clinical Trial platform can be implemented to optimize both standard-of-care treatments as well as to inform and optimize on-going clinical trials. Accordingly, proof-of-principle examples of the efficacy of the Co-Clinical Trial platform in quickly and precisely predicting response to treatments towards clinical trial optimization have been recently reported in prostate and lung cancers.

The Co-Clinical Trial effort in prostate cancer

Prostate cancer (CaP) is one of the most common tumors in men and the second leading cause of cancer-related death in western societies [19, 20]. The disease is characterized by wide genetic complexity and a lethality score of 49%. Combinations of different genetic lesions (for e.g. NKX3.1, PTEN, LRF, PLZF, PML loss; c-MYC, MCM7 amplification; ERG, ETV1, ETV4 translocation/overexpression; TP53 loss/mutation; SPOP mutation; AR amplification/mutation), some of which reflect specific stages of the natural history of tumor progression, distinguish different subsets of human CaP and dictate tumor aggressiveness, metastatic potential, and likely response to treatment [21, 22]. In recent years, this disheartening complexity has been successfully modeled in GEMMs, allowing the generation of a unique genetic platform proxy-CaP in the mouse that has proved essential to unveiling the role of specific genetic perturbations in the onset and progression of human CaP [23]. Unfortunately little effort has been devoted, however, to systematically applying this unprecedented resource in a bedside-to-bench-to-bedside setting designed to rapidly identify the matching tumor genetics-treatment combinations that are essential to patient stratification into effective drug regimens.

Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), for instance, has been the standard-of-care approach for advanced prostate cancer since the beginning of the 20th century. Although the majority of patients experience an initial positive response to ADT, most tumors eventually acquire resistance to the treatment, and as a result patients inevitably relapse. However, there is a wide variability in the durability of ADT efficacy, and response can last anywhere from a few months to more than a decade. Little is known regarding the possible determinants of ADT response duration, and disease burden does not appear to be a major factor. Given the genetic heterogeneity of CaP, we have hypothesized that different genetic lesions driving the tumorigenic process may also affect ADT efficacy. Accordingly, we enrolled in a Co-Clinical Trial effort a cohort of 84 CaP patients and a panel of genetically engineered mouse models bearing common human prostate cancer genetics (Ptenfl/fl; PB-Cre4, Ptenfl/fl;Trp53fl/fl;PB-Cre4 and Ptenfl/fl;Lrffl/fl;PB-Cre4), which quickly identified Pten-p53 and Pten-Lrf double null tumors in mice as resistant to ADT, accurately anticipating the response of patients with CaP characterized by the same genetic lesions [24]. Importantly, a comparative genetic and molecular analysis of Pten-null (ADT sensitive) and Pten-p53 and Pten-Lrf double null (ADT resistant) mouse prostate tumors unveiled up-regulation of Srd5a1 and deregulation of the Xaf1/Xiap apoptotic pathway as two potential mechanisms of ADT resistance. A double combination of Embelin (an XIAP natural inhibitor) and Dutasteride (an SRD5A1 inhibitor already in clinical trials for ADT resistant CaP) with ADT formally proved the functional role of the deregulation of both pathways in ADT resistance by rescuing ADT efficacy in vivo in both Pten-p53 and Pten-Lrf double null mouse prostate tumors and in vitro in human CaP cell lines [24], in turn paving the way to the clinical testing of such combinatorial approach in man.

The Co-Clinical Trial effort in lung cancer

A further proof of principle of the efficacy of the Co-Clinical Trial platform can be found in a recent lung cancer study [25]. In this study, by enrolling in a Co-Clinical Trial effort KRasG12D, KRasG12D;Trp53-null, and KRasG12D;Lkb1-null GEMMs of human non-small-cells lung cancer (NSCLC), it was possible to predict and anticipate the outcome of clinical trials combining Docetaxel with the MEK inhibitor Selumetinib (AZD6244). The results from the GEMMs of this study highlighted the complete lack of clinical benefits of Docetaxel or Selumetinib as single agents in KRasG12D driven mouse lung cancers, perfectly mirroring what had been previously reported in human patients. In contrast, KRasG12D and KRasG12D;Trp53-null tumors were found to be sensitive to a combination of Docetaxel and Selumetinib, with an overall response rate of 92% in KRasG12D and 61% in KRasG12D;Trp53-null cancers. For KRasG12D;Lkb1-null cancers, however, the addition of Selumetinib to Docetaxel led to only a modest improvement in overall response, compared to Docetaxel alone, with 33% of tumors showing a mild response [25]. Mechanistically, resistance to the Selumetinib/Docetaxel combination in KRasG12D;Lkb1-null mouse cancers can be ascribed to reduced activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway, concomitant with AKT signaling induction. Overall, these results strongly suggest that concomitant mutation of Lkb1 in a KRas mutant context may hijack the MEK–ERK signaling pathway active in KRas and KRas/p53 tumor cells to the AKT and SRC pathways, thereby dictating primary resistance to the Docetaxel/Selumetinib combination treatment.

Recently, further interesting work has been reported on a new EML4-ALK mouse model of NSCLC, and treatment with an ALK inhibitor. This Co-Clinical setting of a Phase III human clinical trial compared the efficacy of a specific ALK inhibitor (Crizotinib) to standard-of-care agents Docetaxel or Pemetrexed [26]. In an EML4-ALK mouse model, Crizotinib treatment was found to be associated with significantly longer progression-free and overall survival rates compared to treatment with Docetaxel or Pemetrexed alone, perfectly predicting the clinical outcome in EML4-ALK NSCLC human patients. Finally, a percentage of mice showed de novo resistance to Crizotinib, while other mouse tumors only acquired resistance after prolonged treatment, again mirroring the results in human patients, and offering the opportunity to study co-clinically the mechanisms of resistance and efficacy of these new experimental therapies in mouse models and human patients. Importantly, both de novo and acquired Crizotinib-resistant EML4-ALK tumors in mice proved extremely sensitive to the HSP90 inhibitor 17-DMAG, as well as a second-generation ALK inhibitor, TAE684 [26], paving the way for specific clinical trials testing the efficacy of 17-DMAG and TAE684 in Crizotinib resistant EML4-ALK lung cancer patients.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

In conclusion, by enrolling GEMMs of human cancer in treatments precisely mirroring on-going clinical trials or standard-of-care therapies, the Co-Clinical Trial approach allows researchers to disentangle the daunting clinical complexity of cancer. Future efforts will also focus on the tumor microenvironment and how it is impacted by the genetic make-up of the GEMMs used, and by the experimental therapies tested in these models. GEMMs are appropriate as the tumor is developing and being treated in an immune competent microenvironment. These future efforts are timely and especially needed now that cancer immune therapies are coming of age. The real-time integration of preclinical with clinical data, which represents the cornerstone of the Co-Clinical Trail platform, promises to quickly yield fundamental insights into issues of resistance and sensitivity, and provide predictive guidance for both the optimization of concurrent human clinical trials, and the correct interpretation of trial results. Importantly, the Co-Clinical Trial approach can also substantially improve the precise administration of standard-of-care therapies through the rapid stratification of patients in terms of sensitivity on molecular and genetic bases. Additionally, a key characteristic that renders the Co-Clinical Trial approach so effective is its power to anticipate in GEMMs the identification of mechanisms of tumor resistance in humans (either de novo or acquired), a common hurdle affecting the vast majority of single agents targeted therapies, and to quickly test the efficacy of new drug combinations to overcome such resistance.

The infrastructural set-up and running of Co-Clinical Trials is, however, a challenging endeavor. First of all, the establishment of a fully equipped “Mouse Hospital” able to faithfully parallel in mice on going clinical trials in patients requires substantial institutional investments. Such an infrastructure cannot be developed and sustained by single research laboratories, hence requiring serious institutional or governmental commitment.

Although less expensive than clinical trials in humans, the GEMM/Mouse model components of a Co-Clinical effort are not inexpensive either, and pharmaceutical companies might be reluctant to sustain such costs and to provide the academic institutions with the required amounts of the experimental drug necessary for a Co-Clinical approach.

A close-knit interaction between scientists, clinicians, pathologists, oncologists, radiologists, and bioinformatics is the cornerstone of productive integrated human/mouse cancer studies, yet mouse/human comparative studies and interpretation of data is not yet straightforward and requires appropriate standardization.

Finally, although an even more accurate mouse modeling effort that aims to recreate the tremendous genetic heterogeneity characteristic of cancer and other human diseases is currently ongoing worldwide (e.g. utilizing CRISPR/CAS technology) [27], such efforts are also extremely cost-expensive and time consuming.

Nevertheless, there is little doubt that in the years to come, the Co-Clinical Trial platform and the concept of the Mouse Hospital will become applicable worldwide and to other human disease for which faithful mouse models have been generated, with the potential to transform the practice of health care towards a medicine of precision for cancer and beyond cancer.

Highlights.

Synchronizing treatments in GEMMs and patients allows real-time integration of data.

Provides predictive guidance for treatment using genetic and molecular criteria.

Rapidly identifies mechanisms of resistance and effective new combination therapies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank current members of the Pandolfi laboratory for critical discussion and T. Garvey for insightful editing.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Deng G, Sui G. Noncoding RNA in oncogenesis: a new era of identifying key players. International journal of molecular sciences. 2013;14:18319–18349. doi: 10.3390/ijms140918319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheetham SW, et al. Long noncoding RNAs and the genetics of cancer. British journal of cancer. 2013;108:2419–2425. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cleary AS, et al. Tumour cell heterogeneity maintained by cooperating subclones in Wnt-driven mammary cancers. Nature. 2014;508:113–117. doi: 10.1038/nature13187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gerlinger M, et al. Intratumour Heterogeneity in Urologic Cancers: From Molecular Evidence to Clinical Implications. European urology. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerlinger M, et al. Genomic architecture and evolution of clear cell renal cell carcinomas defined by multiregion sequencing. Nature genetics. 2014;46:225–233. doi: 10.1038/ng.2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poliseno L, et al. A coding-independent function of gene and pseudogene mRNAs regulates tumour biology. Nature. 2010;465:1033–1038. doi: 10.1038/nature09144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruglyak KM, et al. Next-generation sequencing in precision oncology: challenges and opportunities. Expert review of molecular diagnostics. 2014 doi: 10.1586/14737159.2014.916213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nardella C, et al. The APL paradigm and the “co-clinical trial” project. Cancer discovery. 2011;1:108–116. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rowley JD. Chromosomal patterns in myelocytic leukemia. The New England journal of medicine. 1973;289:220–221. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197307262890422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandolfi PP, et al. Structure and origin of the acute promyelocytic leukemia myl/RAR alpha cDNA and characterization of its retinoid-binding and transactivation properties. Oncogene. 1991;6:1285–1292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Piazza F, et al. The theory of APL. Oncogene. 2001;20:7216–7222. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He LZ, et al. Distinct interactions of PML-RARalpha and PLZF-RARalpha with co-repressors determine differential responses to RA in APL. Nature genetics. 1998;18:126–135. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rego EM, et al. Leukemia with distinct phenotypes in transgenic mice expressing PML/RAR alpha, PLZF/RAR alpha or NPM/RAR alpha. Oncogene. 2006;25:1974–1979. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rego EM, et al. Retinoic acid (RA) and As2O3 treatment in transgenic models of acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL) unravel the distinct nature of the leukemogenic process induced by the PML-RARalpha and PLZF-RARalpha oncoproteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:10173–10178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180290497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lallemand-Breitenbach V, et al. Retinoic acid and arsenic synergize to eradicate leukemic cells in a mouse model of acute promyelocytic leukemia. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1999;189:1043–1052. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.7.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He LZ, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors induce remission in transgenic models of therapy-resistant acute promyelocytic leukemia. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2001;108:1321–1330. doi: 10.1172/JCI11537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warrell RP, Jr, et al. Therapeutic targeting of transcription in acute promyelocytic leukemia by use of an inhibitor of histone deacetylase. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1998;90:1621–1625. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.21.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nasr R, de The H. Eradication of acute promyelocytic leukemia-initiating cells by PML/RARA-targeting. International journal of hematology. 2010;91:742–747. doi: 10.1007/s12185-010-0582-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegel R, et al. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chowdhury S, et al. Causes of death in men with prostate cancer: an analysis of 50,000 men from the Thames Cancer Registry. BJU international. 2013;112:182–189. doi: 10.1111/bju.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor BS, et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer cell. 2010;18:11–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grasso CS, et al. The mutational landscape of lethal castration-resistant prostate cancer. Nature. 2012;487:239–243. doi: 10.1038/nature11125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen MM, Abate-Shen C. Molecular genetics of prostate cancer: new prospects for old challenges. Genes & development. 2010;24:1967–2000. doi: 10.1101/gad.1965810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lunardi A, et al. A co-clinical approach identifies mechanisms and potential therapies for androgen deprivation resistance in prostate cancer. Nature genetics. 2013;45:747–755. doi: 10.1038/ng.2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z, et al. A murine lung cancer co-clinical trial identifies genetic modifiers of therapeutic response. Nature. 2012;483:613–617. doi: 10.1038/nature10937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen Z, et al. Co-clinical trials demonstrate superiority of crizotinib to chemotherapy in ALK-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer and predict strategies to overcome resistance. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2014;20:1204–1211. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xue W, et al. CRISPR-mediated direct mutation of cancer genes in the mouse liver. Nature. 2014;514:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature13589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]