Abstract

Introduction

Service users’ involvement as co-facilitators of mental health trainings is a nascent endeavor in low- and middle-income countries, and the role of families on service user participation in trainings has received limited attention. This study examined how caregivers perceive and facilitate service user’s involvement in an anti-stigma program that was added to mental health Gap Action Program (mhGAP) trainings for primary care workers in Nepal.

Method

Service users were trained as co-facilitators for anti-stigma and mhGAP trainings delivered to primary care workers through the REducing Stigma among HealthcAre ProvidErs (RESHAPE) program. Key informant interviews (n=17) were conducted with caregivers and service users in RESHAPE.

Results

Five themes emerged: (1) Caregivers’ perceived benefits of service user involvement included reduced caregiver burden, learning new skills, and opportunities to develop support groups. (2) Caregivers’ fear of worsening stigma impeded RESHAPE participation. (3) Lack of trust between caregivers and service users jeopardized participation, but it could be mitigated through family engagement with health workers. (4) Orientation provided to caregivers regarding RESHAPE needed greater attention, and when information was provided, it contributed to stigma reduction in families. (5) Time management impacted caregivers’ ability to facilitate service user participation.

Discussion

Engagement with families allows for greater identification of motivational factors and barriers impacting optimal program performance. Caregiver involvement in all program elements should be considered best practice for service user-facilitated anti-stigma initiatives, and service users reluctant to include caregivers should be provided with health staff support to address barriers to including family.

Keywords: mental health, caregivers, service users, family, stigma, global mental health

INTRODUCTION

In global mental health, the participation of mental health service users and their family members in advocacy, training, service and research has been identified as a strategy to improve the quality of care and reduce stigma (Ennis & Wykes, 2013; Samudre et al., 2016; Thornicroft et al., 2016). Health workers can improve their delivery of care when they attend to the stigma of living with mental illness, social and structural barriers to care, and factors contributing to impaired functioning beyond psychiatric symptoms (Shaw & Baker, 2004). Involving service users and caregivers in design and implementation of mental health training has the potential to improve quality of care, as demonstrated by studies in high-income countries (Byas et al., 2003; Emanuel, Fairclough, Slutsman, & Emanuel, 2000).

Within low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), there is increasing attention to factors influencing service users’ involvement in health system strengthening, such as awareness and information about involvement, and time and costs of service user participation (Gurung et al., 2017; Oyebode, 2005; Samudre et al., 2016). The role of family members and other caregivers is of particular importance in LMIC where service users’ behaviors have tremendous impact on the social, economic, and religious status of their family members (Egbe et al., 2014; Girma et al., 2014; Kohrt & Harper, 2008; Koschorke et al., 2014; Muhwezi, Okello, Neema, & Musisi, 2008; Neupane, Dhakal, Thapa, Bhandari, & Mishra, 2016). Moreover, in LMIC, family decision making may have greater reliance on heads-of-household and less autonomy for individual members, with the greatest limitations on autonomy likely placed on persons with mental illness. Therefore, efforts to involve mental health service users as active figures in anti-stigma initiatives, mental health trainings, and other health systems strengthening can be aided by engagement with families.

Our study is a qualitative exploration of the perceptions of caregivers whose family members have been selected to participate as co-facilitators in anti-stigma mental health trainings for primary care workers in Nepal. The objective was to identify themes to enhance caregivers’ supportive engagement with service users who are training to become instructional facilitators and advocates in local health systems.

METHODS

This study was conducted in the context of increased global attention to the delivery of mental health services in low-resource settings. The World Health Organization has developed the mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP), which provides guidelines on training and supervising primary care workers in the delivery of mental health services (WHO, 2010). In Nepal, mhGAP is being piloted in one district as part of broader package of care developed through the Programme for Improving Mental Healthcare (PRIME) (Jordans, Luitel, Pokhrel, & Patel, 2016). PRIME is currently being implemented in five countries to develop evidence-supported practices for primary care and community mental health service delivery (Lund et al., 2012). The PRIME research has increasingly pointed to the need for mental health service user involvement in all aspects of health system strengthening (Abayneh et al., 2017; Gurung et al., 2017).

In Nepal, we are evaluating for how to integrate service users as co-facilitators for training primary care workers on mhGAP and psychosocial interventions. Service user involvement as co-facilitators is grounded in social contact theory (Reinke, Corrigan, Leonhard, Lundin, & Kubiak, 2004), which has shown that facilitated engagement with service users helps to reduce stigma associated with mental illness (Corrigan, Morris, Michaels, Rafacz, & Rusch, 2012). In addition to reducing health workers’ stigma against persons with mental illness, the service users’ role as co-facilitator is also being explored to enhance motivation for primary care workers to adopt mental health service delivery.

The program in Nepal to train service users and engage them as co-facilitators is entitled REducing Stigma among HealthcAre ProvidErs (RESHAPE, ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02793271). RESHAPE, along with all PRIME activities, is implemented in Chitwan, a district in southern Nepal. Transcultural Psychosocial Organization (TPO) Nepal, a Nepali non-governmental organization, conducts the trainings, supervisions, and research. Mental health services are delivered by government health workers trained and supervised by TPO Nepal.

In RESHAPE, service users were trained to serve as co-facilitators by using a participatory research approach in which they contribute personal testimonials, lead myth busting sessions, and engage in social contact with primary care workers throughout the mhGAP training—all of these are elements associated with successful stigma reduction programs (Cabassa et al., 2013; Knaak, Modgill, & Patten, 2014).

The first step in preparing mental health service users to be co-facilitators was to have them participate in a PhotoVoice training. PhotoVoice is a participatory research technique in which participants are taught how to use photography as an advocacy and empowerment tool (Wang & Burris, 1997).

PhotoVoice has been used for diverse topics in global health (Catalani & Minkler, 2010) and to reduce self-stigma among persons with mental illness in a high-income country (HIC) (Russinova et al., 2014). In Nepal, PhotoVoice was used to address psychological distress associated with climate change among rural women (MacFarlane, Shakya, Berry, & Kohrt, 2015). In RESHAPE, the PhotoVoice topics included introduction to mental health stigma, writing recovery stories, group norms and training in using camera and photography, confidentiality and ethics, understanding narratives and myth busting to reduce stigma, and learning creative ways of personal story telling through photography. Unlike the ten-week version evaluated in the HIC RCT (Russinova et al., 2014), RESHAPE incorporated five sessions, with the first session being three days and subsequent sessions lasting one day. During the PhotoVoice process, service users were asked to go back to their community and take pictures of people, places, and things that depicted their recovery. The service users prepared their recovery narratives based upon those pictures and used the photos when co-facilitating the mhGAP trainings.

During RESHAPE, family members and caregivers participated in a range of modalities. Some caregivers attended all activities with the service users, some caregivers sought information on the program and participated on occasion, and other caregivers were not engaged at all in RESHAPE activities. Our goal was to explore caregivers’ experiences to develop more systematic approaches to engaging with them for future RESHAPE implementation and other service user health system strengthening activities. Given that caregivers of persons with mental illness are also highly stigmatized in Nepal (Neupane et al., 2016), it was crucial to determine the positive and negative impacts on them as well as service users.

After service users completed PhotoVoice and co-facilitated approximately six PRIME mhGAP trainings, Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) were conducted with health workers, researchers, service users and caregivers (total n=49). Eight caregivers (three men and five women) and nine service users (three men and six women) participated. Among the nine service users, one man and one woman only partially completed PhotoVoice and did not co-facilitate mhGAP trainings. When relevant, we specify these two participants as “drop-outs” in the results section. For caregivers, interviews focused on their experience of the service users’ treatment process, involvement in training, barriers to participation, and stigma. Service user interviews focused on the impact of participating in RESHAPE on their families and how their caregivers facilitated or acted as a barrier to participation. Interviews were conducted in participants’ homes or the TPO office and lasted from 50 minutes to 2 hours. All interviews were conducted in Nepali, audio recorded, transcribed, and professionally translated into English. Translation employed standardized procedures and a Nepali-English mental health glossary (https://goo.gl/fiEZXG) to assure consistency of terminology across translators (Acharya et al., 2017).

Data analysis followed a thematic approach and was done using Nvivo 11, a qualitative data analysis software package (QSR International, 2012). The data analysis team consisted of seven members–three native Nepali researchers (SR, DG, and MD) and four US researchers (BAK, CT, AB and BNK). The data analysis team went through 20% percent of the total transcripts (n=49) to develop codes until saturation was reached. During the code development process, transcripts from each category of stakeholders (e.g., service users, caregivers, health workers) were included. A codebook was developed with each code having its own unique definition and inclusion/exclusion criteria. For this particular analysis, a set of sub-codes focusing on family members’ roles in the training was also developed, and these family themes were coded in all interviews (i.e., in health workers and trainers transcripts, as well as caregivers and service users). Three members of data analysis team (DG, AB and CT) were assigned for coding the interviews. Before starting the coding, the three raters followed a process to establishing acceptable inter-rater reliability (IRR), final IRR was 0.79. These authors were involved in coding comparisons and writing thick descriptions of the emergent themes.

RESULTS

We identified five themes regarding how caregivers’ perceptions and experiences influence the participation of service users in RESHAPE (see Table 1). The themes included positive components for caregivers as well as burdens and barriers.

Table 1.

Qualitative themes for caregivers’ perceptions of service user involvement in anti-stigma and mental health trainings

| Themes | Description | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Benefits of service users’ participation in training | Decreased burden on caregivers; empowerment of service users; building networks with other service users and caregivers; opportunity for service users to be supervised by health workers and training organizers | “My daughter changed a lot. Before [the training], she used to bite her finger and stare at nothing. Now she can do everything. If someone is suffering, she gives him/her recommendations on places to go for help. She tells him/her that she had also been through similar problems and encourages him/her to go and talk to the right people. She has changed so much -- she has a different image of herself and new skills.” (Father of a service user with depression) |

| Risk of increased stigma against service user and family | Reluctance to tell neighbors and community members about the nature of training for fear of disclosing that a person in the family has a mental illness | “People asked me what the training was? They asked, why would a girl like her be invited to a training. They used to say that I have a young daughter so someone might take her away or cheat her.” (Father of a service user with depression) |

| Need for trust between service user and family members | Caregivers concerns about being able to trust service users given history of mental health problems; opportunities for health workers to help build trust between caregivers and service users | “Before joining the training, my husband discussed it with me. Some [health worker trainers] were here and discussed with me as well. He stayed away from home for two or three nights during the training. When he was called again for the training, I went there to check and be sure he was going because I worried that he had started to drink again.” (Wife of a service user with alcohol use disorder) |

| Need for family’s orientation to service user training participation | Orienting caregivers about the program and service users’ involvement built trust, increased family support for the program, helped reduce stigma, and changed some of the caregivers’ negative perceptions about the family member with mental illness. | “After someone has come to get the medicines and take the training, if you could also sit with the families once and tell them about it and discuss the matter, it would help us a lot. I feel that we should also practice explaining it. The family should make time for this.” (Female service user with depression) |

| Role of family in time management to assure service user participation | Caregivers had difficulty managing time for the increased activity of the family member with mental illness | “There were problems in harvesting crops. She must go to the training but it would be easier if she could just go work in the fields. But because of my faith, I sent her to the training. I will help her to attend these training. I will remind her about the time. I will drop her off, pick her up, and will also talk to her employer to manage the time.” (Father of a service user with depression) |

-

Caregivers’ perceived benefits of service users’ involvement in RESHAPE: Caregivers reported that service user participation in the PhotoVoice sessions and mhGAP facilitation reduced family burden and family tension emerging from the mental illness. Caregivers said the PhotoVoice sessions empowered service users because they learned new skills and developed new ways of thinking. After participating in the RESHAPE program, they became more proactive in the family and community, and some became advocates and referral sources in the community. The most common skill identified by the caregiver was the service users’ ability to express themselves in front of others. These benefits were also reported by service users.

I feel that we learned a lot of things in this training [PhotoVoice]. Before that, I couldn’t speak in front of the people. I couldn’t speak with anyone. Whatever anyone said, I was quiet and used to cry and leave. After the training, I could speak. I was motivated. (Male service user with depression)Developing support networks was also beneficial. A caregiver who accompanied the service user to PhotoVoice sessions reported that meeting other service users and caregivers helped him to realize that they are not the only ones who are facing this problem. PhotoVoice sessions gave them the opportunity to build a network of people in similar situations and to develop an informal support group.

Before I used to feel that I was the only one who suffered heavily and not others, and I was in the worst situation. But later when there was sharing of information of treatment process, I knew that these problems can happen to everyone. (Wife of service user with depression)Continuous engagement in RESHAPE kept service users in contact with health workers and specialists (psychiatrists, who were the mhGAP trainers), which helped to manage their mental health needs. This was highlighted by the caregiver of a service user with alcohol use disorder. She mentioned the greatest benefit of getting involved in RESHAPE was that it limited the possibility of relapse. She reported this as a major benefit to her family so she and other caregivers strongly advocated for service users’ continuous involvement in RESHAPE.

-

Increased stigmatization because of participation: A major concern among service users was whether or not their participation would put their families at risk of increased stigmatization. Caregivers reported that community members them a range of questions about the service users’ activities in RESHAPE, e.g., questions about their past mental illness, questions about the current involvement, and questions about the training venue. Fear of stigmatization led some caregivers and service users to not reveal their illness or participation in RESHAPE. Some of them shielded their participation as “health training” rather than “mental health training.” Participants also deceived colleagues and family members to surreptitiously attend PhotoVoice and mhGAP activities.

I kept it secret. I haven’t yet revealed what we did in the training and why we went. It is only within our family members [that people know about the mental health training]. When people used to ask, I used to tell them that there is a training and doctors will come and discuss things. But we did not reveal the truth. We didn’t tell them. (Male service user with depression who dropped out after three PhotoVoice sessions)However, most caregivers reported that they defended their family members with mental illness to combat societal stigma. The majority of caregivers, especially caregivers of service users with alcohol use disorder and depression, said they felt comfortable sharing the service users’ stories. They said people in their communities already knew about the service users’ problems and by sharing their story about their treatment and their new roles as co-facilitators alongside health professionals, it helped the communities to accept them more.

-

Trust between service users and caregivers: Most caregivers and service users described challenges developing initial trust regarding service users’ involvement in RESHAPE. The venue for both PhotoVoice and mhGAP trainings was a local hotel, and this venue was a source of mistrust in the program. Because of long distances to travel by foot each day for the training, participants required hotel accommodation. However, caregivers were worried about service users staying overnight in hotels, and this was especially concerning for female service users. Caregiver of service users with alcohol use disorder worried that the service user would relapse at the hotel. Staying overnight to take part in the training and workshops reminded caregivers of service user’s similar behaviors of staying out late when they were drinking heavily. Some caregivers reported that they furtively went to the training venue to make sure that there were actual trainings taking place (See Textbox 1).

She said that she would go to take part in the training. I denied her request to join the training because she was a young girl [22 years old], and I demanded that she not go. I was very worried. She said that the training was in a hotel. I was afraid where she would go. I was not sure if it was a “dancing bar” [location of commercial sex work] or washing dishes or talking with boys. (Father of a female service user)Service users and TPO Nepal staff collaborated to help build caregiver trust. Most of the service users had their caregivers come together for the training, especially in the initial days. The caregivers mentioned that they either went to the training themselves or sent someone else from the family to accompany the service user. Some of them also had members of the training team come to their homes. As the caregivers learned about the training and got more involved in the process, they became supportive and had greater investment in the program’s success.

-

Orientation and ongoing information regarding service user involvement: Service users, caregivers, health workers and the organization’s staff all advocated for continuous engagement of caregivers throughout the phases of RESHAPE. All these respondents identified informing caregivers about RESHAPE as a way to reduce the stigma attached with mental illness and educate caregivers that people with mental illness can be treated. Some service users mentioned that they could share their recovery stories developed in PhotoVoice with their family members to help them understand.

My family would think that I wasn’t in my right mind when I spoke [during the periods of psychosis]. My family did not understand that the condition could be [treated] and improved. If families are aware [of where to get treatment], they will take their relatives to get help. But even when they know about such places [e.g., psychiatric hospitals], they may avoid the stigma of going there and not bring their family members. So, we must go to these families and make them understand, or else it will be very difficult. (Female service user with psychosis)A few service users involved in PhotoVoice sessions had not informed their families about their participation. One such service user was scared that if her family came to know about RESHAPE, they would not let her take part in it. This sentiment was shared among service users who did not have a good relationship with their families.

Whether families already provided support or not, many service users believed that families should be more involved in PhotoVoice to offer more support. They recommended that training organizers meet with family members to orient and provide ongoing updates. Some service users recommended that family members attend all RESHAPE activities.

-

Time management: Caregivers discussed time management for the service users to participate in RESHAPE. Because most service users engaged in RESHAPE had recently recovered from their mental illnesses, the families wanted them to now stay home and do housework they could not do previously when sick. This was also mentioned by a service user who said that house chores got in the way of attending PhotoVoice sessions, and other service users echoed that they had pressure to complete the chores from their family members. One service user was the primary caretaker of other family members so she had to drop-out from the PhotoVoice sessions.

I must do all the household work myself. Mom has poor sight and she cannot work. If I come leaving my work, I get scolded, therefore […] I honestly want to attend the training, but I couldn’t attend due to my work. My father says I can go but if there is work load, they don’t allow to go and if I don’t obey them for this I get scolded. (Female service user with psychosis)Travel time and transportation was also a problem. One service user said that she had to ask her family for money to afford transportation. (Of note, service users were compensated by TPO Nepal for all transportation costs.) A male service user said public transportation was unreliable.

However, all caregivers advocated that these logistics could be managed because the benefits of participating in the training were important. It was often mentioned that family members would confer amongst themselves discussing the benefits of RESHAPE. The husband of a service user described how they talked about the improvements they experienced through the training with their children, and how the children look after the home while they are away for RESHAPE events. Another caregiver mentioned that she asked other family members to look after the service user’s babies at the PhotoVoice sessions and mhGAP trainings.

Textbox 1. Experience of caregivers: Case study of a service user’s parent after the service user’s participation in anti-stigma and mental health trainings.

Jamuna (pseudonym) is a 22-year-old girl who had a history of depression. Her father remembers her staring blankly at the wall, her irritation when he asked her to talk, and her inability to do any household work. Because of these problems, the family split up. Jamuna’s elder brother, the brother’s wife, and brother’s children moved out of the house. Neighbors referred to Jamuna as ‘crazy/mad’ (Nepali: paagal/baulaahaa). The family faced stigma from the community because of Jamuna’s mental health problems. Neighbors and other community members already looked down upon Jamuna’s family because they were from an occupational caste (Dalit, pejoratively referred to as ‘untouchable’), and having a family member with mental illness exacerbated this ostracization. Ultimately, the family had to migrate from their small village in the middle hills of Nepal to a larger town in southern Nepal where they had greater anonymity. They tried to hide Jamuna’s situation from the new neighbors in the city.

After the family moved, Jamuna met a government primary care worker who had been trained to identify and treat mental illness through the Programme for Improving Mental Health Care (PRIME), which was an initiative to establish evidence-based mental health services in primary care in Nepal and four other countries. The health worker diagnosed Jamuna with depression and helped Jamuna talk openly about her feelings of suicidality. The health worker referred Jamuna to a counselor for psychological treatment, specifically a version of behavioral activation developed for lay persons in India known as the Health Activity Program.

After she recovered, she was given the opportunity to participate in the Reducing Stigma among Healthcare Providers (RESHAPE) program for service users to help reduce stigma when training more government primary care workers. She was trained in PhotoVoice as a participatory methodology that integrated photography into telling recovery stories. However, Jamuna’s participation in the trainings did not start well. Her father remembers how he did not trust her involvement in the beginning. The trainings were held in a rented hall in a downtown hotel, and her father was suspicious of why she needed to go to the hotel every day. Neighbors learned that Jamuna was going to the hotel and began to question her father about why he would allow this. One day he decided to come to the training venue and meet with the training staff to find out what his daughter was doing.

After Jamuna’s father learned about the RESHAPE program and saw the training, he and his family supported Jamuna because they could see visible changes as she developed confidence and was less ashamed about her mental illness. Her father noted that she became more active, took care of the home, restarted school, and started to lead a local women’s group. Her brother’s family also returned, and the family united once again. Now she is an active co-facilitator for regular RESHAPE trainings integrated into PRIME. Her father and brothers support her involvement in the training and make sure she gets time off from her work to take part in the trainings.

DISCUSSION

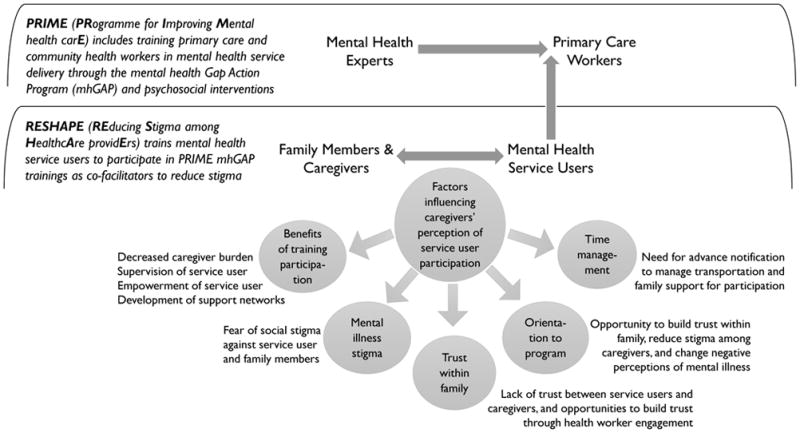

Increasing engagement of mental health service users in training health workers and other aspects of health systems strengthening requires engagement of family members and other caregivers. While pilot testing a program (RESHAPE) to prepare service users to be co-facilitators for training primary care workers, we identified strengths and weaknesses regarding our engagement with caregivers. The majority of family members identified valuable benefits. Service users gained confidence and skills, especially in terms of being able to communicate about their mental illness to others. Service users also had regular engagement with mental health experts—who acted as co-facilitators—and other health workers, which allowed the service users to ask medical and mental health questions, and provided an opportunity for service users to be seen by health professionals as skilled members of society—not just as persons with a stigmatized illness. Service users and caregivers also used RESHAPE as a platform to meet others in similar situations and develop support groups. Figure 1 provides a graphical overview of these benefits and the areas for improvement.

Figure 1.

The primary challenges arose from not sufficiently engaging with caregivers from the initiation of the program and throughout the process. Although a number of caregivers attended the first training, they felt they did not fully comprehend the program’s goals and logistics. A more structured orientation approach needs to be developed that includes maintaining communication with caregivers throughout the process. Caregivers could also benefit from going through the PhotoVoice process not only to learn more about what service users are doing but also to better equip them to tell stories about living with a family member with mental illness. One challenge will be how best to engage with service users who want to participate in trainings and other health systems strengthening when the service user does not want family participation. One approach to enhance family engagement from the outset is to have new families meet service users and their caregivers who previously participated in RESHAPE to hear firsthand about their experiences.

Given that RESHAPE involved two components: PhotoVoice sessions and co-facilitating mhGAP trainings, we cannot isolate whether the benefit to service users and caregivers was the result of one of these elements or the combination. In the randomized controlled trial in the United States, self-stigma was reduced with 10 sessions of PhotoVoice (Russinova et al., 2014). In future work, there should be attempts to identify the different types and quantity of benefits for PhotoVoice with and without co-facilitation roles in health care anti-stigma programs.

For those service users who dropped out after attending a few PhotoVoice sessions and did not take part in the mhGAP training, their reasons for dropping out included fear of increased stigma, fear of caregivers’ retaliation, or having high household commitments that other family members would not shoulder. A difference we observed between drop-outs and those who continued was that the latter reported their family members as seeing them as “trainers” or “facilitators”. This suggested that co-facilitation of mhGAP trainings to primary care workers was beneficial above and beyond participation in only PhotoVoice.

The findings from this study highlight the importance of involvement of caregivers in mental health programs. Concrete steps need to be identified and practiced for promoting their engagement throughout the process from a policy level. Table 2 provides recommendations for the engagement of caregivers before, during, and after service user participation in trainings and other health system strengthening. Based on their qualitative work with service users and caregivers in India, Samudre and colleagues recommend a step-wise process for engagement beginning with needs assessment, followed by empowerment and organization of service users and caregivers, and culminating in meaningful involvement in health systems strengthening (Samudre et al., 2016). In addition, developing a module for family/social disclosure of mental illness during training of the service users and then inviting caregivers can be one way to do a step approach when service users may be reluctant to include their families. Another potential improvement is to have a family graduation ceremony at the end of PhotoVoice before the mhGAP trainings begin. At this time, service users would have the option of telling their recovery stories to all of the caregivers.

Table 2.

Recommendations for working with family members and caregivers of service users participating in anti-stigma activities and mental health programs

| Phase of training | Engaging caregivers of service users |

|---|---|

| Before service users participate as co-facilitators in trainings | (1) Training staff should engage with service user family members to orient them to the goals of training primary care health workers for mental health treatment |

| During service user participation as co-facilitators in trainings | (2) Provider caregivers the option of participating in trainings alongside service users if service users consent (3) Offer a module on disclosure of mental illness for services users and family members (4) Coordinate with caregivers to solve time management issues during training times |

| After service user participation as co-facilitators in trainings | (5) Debrief with caregivers about the benefits and challenges of their family member service user participating in the training program (6) Engage caregivers for planning content and approach of future trainings |

The RESHAPE program can be a vehicle to expand engagement of service users and caregivers more broadly in mental health systems strengthening. This has the potential to expand beyond reducing community stigma and stigma in healthcare settings. It can also be used for other key stakeholders, such as with law enforcement. In Liberia, participation of service users and caregivers in Crisis Intervention Team training of law enforcement was associated with stigma reduction (Kohrt et al., 2015). In Nepal, where service users’ engagement in mental health policy, planning and implementation has started to gain momentum, there is a need to include caregivers in an array of domains (Luitel et al., 2015). To date, the involvement of caregivers in mental health policy making does not exist in Nepal (Gurung et al., 2017). In fact, although new mental health policy is currently being developed to address these issues, the prior national mental health policy drafted twenty years ago does not mention the role of service users and caregivers.

CONCLUSION

Families play an important role in service users’ level and quality of participation in mental health trainings, research and service delivery. Service users have greater likelihood of participating in trainings when caregivers perceive benefits, when they trust service users and are well-informed about the process, when they can manage time, and when they can openly share about such participation in a way that counters stigmatizing reactions. In Nepal, where the concept of service user involvement is in its nascent stage, and caregivers’ formal involvement is non-existent, our findings show that we need to equally involve caregivers to facilitate meaningful participation of service users.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nagendra Luitel, Anup Adhikari, Crick Lund, Vikram Patel, Mark Jordans, Jagannath Lamichhane, Manjila Pokharel, and Kiran Thapa for their roles in research planning, implementation, and supervision. We are deeply indebted to gracious supervision provided by the Nepal Health Research Council.

Funding: This study was funded by the U.S. National Institute of Mental Health (K01MH104310, principal investigator: BAK) and the Programme to Improve Mental Health Care (PRIME) funded by the Department for International Development (DFID). This document is an output from the PRIME Research Programme Consortium, funded by UK aid from the UK government. However, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK nor US government’s official policies. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. The authors had full control of all primary data.

Abbreviation

- mhGAP

mental health Gap Action Programme

- PRIME

PRogramme for Improving Mental health carE

- RESHAPE

REducing Stigma among HealthcAre ProvidErs

- TPO Nepal

Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Nepal

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Authors’ contribution: BAK designed the study, and KS provided supervision. SR, MD, and BAK supervised data collection. SR and MD conducted the interviews. SR, DG, BK, MD, AB, CT and BNK were involved in data analysis. SR drafted the manuscript. DG, BNK, KS, and BAK revised the manuscript. The final manuscript was approved by all authors.

Ethical Approval: Ethical Approval was taken from Nepal Health Research Council (Regd. No 110/2014) and Duke University School of Medicine Ethical Review Committee (Pro00055042). Written consent was taken from all the participants. The informed consent form was read out to participants who could not read. In spite of some not being able to read, the participants could write their initials in the form. This study is part of a registered clinical trial: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02793271.

Contributor Information

Sauharda Rai, Department of Psychiatry, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA. Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Nepal, Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Dristy Gurung, Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Nepal, Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Bonnie N. Kaiser, Duke Global Health Institute, Durham, NC, USA.

Kathleen J. Sikkema, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA.

Manoj Dhakal, Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Nepal, Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Anvita Bhardwaj, Department of Psychiatry, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA.

Cori Tergesen, Duke Global Health Institute, Durham, NC, USA.

Brandon A. Kohrt, Department of Psychiatry, George Washington University, Washington, DC, USA. Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Duke Global Health Institute, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA. Transcultural Psychosocial Organization Nepal, Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal.

References

- Abayneh S, Lempp H, Alem A, Alemayehu D, Eshetu T, Lund C, … Hanlon C. Service user involvement in mental health system strengthening in a rural African setting: qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):187. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1352-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acharya B, Basnet M, Rimal P, Citrin D, Hirachan S, Swar S, … Kohrt B. Translating mental health diagnostic and symptom terminology to train health workers and engage patients in cross-cultural, non-English speaking populations. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2017;11(1):62. doi: 10.1186/s13033-017-0170-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byas A, Hills D, Meech C, Read L, Stacey K, Presland E, Wood A. From the ground up: Collaborative research in child and adolescent mental health services. Families, Systems & Health. 2003;21(4):397–414. [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ, Parcesepe A, Nicasio A, Baxter E, Tsemberis S, Lewis-Fernández R. Health and wellness photovoice project: engaging consumers with serious mental illness in health care interventions. Qualitative Health Research. 2013;23(5):618–630. doi: 10.1177/1049732312470872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalani C, Minkler M. Photovoice: A review of the literature in health and public health. Health Education & Behavior. 2010;37(3):424–451. doi: 10.1177/1090198109342084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rusch N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatric Services. 2012;63(10):963–973. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100529. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201100529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egbe CO, Brooke-Sumner C, Kathree T, Selohilwe O, Thornicroft G, Petersen I. Psychiatric stigma and discrimination in South Africa: perspectives from key stakeholders. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:191. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-191. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Slutsman J, Emanuel LL. Understanding economic and other burdens of terminal illness: the experience of patients and their caregivers. Annals of internal medicine. 2000;132(6):451–459. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-6-200003210-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis L, Wykes T. Impact of patient involvement in mental health research: longitudinal study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2013:203. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.112.119818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girma E, Moller-Leimkuhler AM, Dehning S, Mueller N, Tesfaye M, Froeschl G. Self-stigma among caregivers of people with mental illness: toward caregivers’ empowerment. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:37–43. doi: 10.2147/jmdh.s57259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurung D, Upadhyaya N, Magar J, Giri NP, Hanlon C, Jordans MJD. Service user and care giver involvement in mental health system strengthening in Nepal: a qualitative study on barriers and facilitating factors. International journal of mental health systems. 2017;11(1):30. doi: 10.1186/s13033-017-0139-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordans M, Luitel N, Pokhrel P, Patel V. Development and pilot testing of a mental healthcare plan in Nepal. Br J Psychiatry. 2016:208. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.153718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knaak S, Modgill G, Patten SB. Key ingredients of anti-stigma programs for health care providers: a data synthesis of evaluative studies. Canadian journal of psychiatry Revue canadienne de psychiatrie. 2014;59(10 Suppl 1):S19–26. doi: 10.1177/070674371405901s06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Blasingame E, Compton MT, Dakana SF, Dossen B, Lang F, … Cooper J. Adapting the Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) Model of Police–Mental Health Collaboration in a Low-Income, Post-Conflict Country: Curriculum Development in Liberia, West Africa. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(3):e73–e80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohrt BA, Harper I. Navigating diagnoses: understanding mind-body relations, mental health, and stigma in Nepal. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry. 2008;32(4):462–491. doi: 10.1007/s11013-008-9110-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koschorke M, Padmavati R, Kumar S, Cohen A, Weiss HA, Chatterjee S, … Patel V. Experiences of stigma and discrimination of people with schizophrenia in India. Social Science & Medicine. 2014;123:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.035. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luitel NP, Jordans MJ, Adhikari A, Upadhaya N, Hanlon C, Lund C, Komproe IH. Mental health care in Nepal: current situation and challenges for development of a district mental health care plan. Conflict and health. 2015;9(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s13031-014-0030-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund C, Tomlinson M, Silva M, Fekadu A, Shidhaye R, Jordans M. PRIME: a programme to reduce the treatment gap for mental disorders in five low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Medicine/Public Library of Science. 2012;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacFarlane EK, Shakya R, Berry HL, Kohrt BA. Implications of participatory methods to address mental health needs associated with climate change: ‘photovoice’ in Nepal. BJPsych International. 2015;12(2):33–35. doi: 10.1192/s2056474000000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhwezi WW, Okello ES, Neema S, Musisi S. Caregivers’ experiences with major depression concealed by physical illness in patients recruited from central Ugandan Primary Health Care Centers. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(8):1096–1114. doi: 10.1177/1049732308320038. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1049732308320038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neupane D, Dhakal S, Thapa S, Bhandari PM, Mishra SR. Caregivers’ Attitude towards People with Mental Illness and Perceived Stigma: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Tertiary Hospital in Nepal. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(6):e0158113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyebode JR. Carers as partners in mental health services for older people. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2005;11(4):297–304. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International. NVIVO qualitative data analysis software (Version 10) Doncaster, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Reinke RR, Corrigan PW, Leonhard C, Lundin RK, Kubiak MA. Examining two aspects of contact on the stigma of mental illness. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2004;23(3):377–389. doi: 10.1521/jscp.23.3.377.35457. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russinova Z, Rogers ES, Gagne C, Bloch P, Drake KM, Mueser KT. A randomized controlled trial of a peer-run antistigma photovoice intervention. Psychiatric Services. 2014;65(2):242–246. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samudre S, Shidhaye R, Ahuja S, Nanda S, Khan A, Evans-Lacko S, Hanlon C. Service user involvement for mental health system strengthening in India: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:e269. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0981-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J, Baker M. “Expert patient”—dream or nightmare?: The concept of a well informed patient is welcome, but a new name is needed. BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2004;328(7442):723. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7442.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft G, Mehta N, Clement S, Evans-Lacko S, Doherty M, Rose D, … Henderson C. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. The Lancet. 2016;387(10023):1123–1132. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00298-6. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: Concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health education & behavior. 1997;24(3):369–387. doi: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. mhGAP Intervention Guide for mental, neurological and substance-use disorders in non-specialized health settings: mental health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP) Geneva: 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]