Abstract

Rationale: Evidence supporting the association of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or airflow obstruction with use of solid fuels is conflicting and inconsistent.

Objectives: To assess the association of airflow obstruction with self-reported use of solid fuels for cooking or heating.

Methods: We analyzed 18,554 adults from the BOLD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease) study, who had provided acceptable post-bronchodilator spirometry measurements, and information on use of solid fuels. The association of airflow obstruction with use of solid fuels for cooking or heating was assessed by sex, within each site, using regression analysis. Estimates were stratified by national income and meta-analyzed. We performed similar analyses for spirometric restriction, chronic cough, and chronic phlegm.

Measurements and Main Results: We found no association between airflow obstruction and use of solid fuels for cooking or heating (odds ratio [OR] for men, 1.20 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.94–1.53]; OR for women, 0.88 [95% CI, 0.67–1.15]). This was true for low-/middle- and high-income sites. Among never-smokers, there was also no evidence of an association of airflow obstruction with use of solid fuels (OR for men, 1.00 [95% CI, 0.57–1.76]; OR for women, 1.00 [95% CI, 0.76–1.32]). Overall, we found no association of spirometric restriction, chronic cough, or chronic phlegm with the use of solid fuels. However, we found that chronic phlegm was more likely to be reported among female never-smokers and those who had been exposed for 20 years or longer.

Conclusions: Airflow obstruction assessed from post-bronchodilator spirometry was not associated with use of solid fuels for cooking or heating.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, airflow obstruction, solid fuels (biomass), low-income countries

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Five systematic reviews, published between 2010 and 2014, reported that adults exposed to the burning of solid fuels were more likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) compared to those not exposed to this type of indoor pollution. However, these reviews suffered from some degree of publication bias and high heterogeneity across studies. Moreover, the diagnosis of COPD in many of the studies was not based on post-bronchodilator spirometry. More recent and larger studies failed to replicate the findings of the systematic reviews published so far. Overall, the evidence of an association between COPD and use of solid fuels for cooking or heating is conflicting and inconsistent.

What This Study Adds to the Field

Our findings are based on 18,554 adults from 25 sites who participated in the large population-based study BOLD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease) and had acceptable post-bronchodilator spirometry. We found that in adults, from low-/middle- and high-income countries, airflow obstruction was not associated with self-reported use of solid fuels for cooking or heating. This finding brings into question the extent to which high mortality rates attributed to COPD in low-income countries, where consumption of cigarettes is relatively low, are explained by use of solid fuels for cooking or heating.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is the third leading cause of death worldwide and is particularly common in low-income countries (1). The most important single risk factor for COPD is cigarette smoking (2, 3). However, cigarette smoking is still uncommon in many low-income countries and >20% of people with this disease do not have a history of smoking (4, 5). Exposure to household air pollution from solid fuel burning for domestic purposes has been put forward to explain high COPD mortality, especially among nonsmokers and where the use of solid fuels for cooking or heating is widespread (5).

Five systematic reviews, published before 2015, reported an overall 1.9- to 2.8-fold increased risk for COPD in adults exposed, as compared with those not exposed, to solid fuel burning (6–10). In three of these reviews, the authors acknowledged evidence of publication bias toward the reporting of positive findings. These reviews also demonstrated very high levels of heterogeneity across studies, indicating either residual confounding or strong effect modification. A study performed on over 300,000 never-smokers from the China Kadoorie Biobank reported that airflow obstruction (a principal COPD feature) was positively associated with cooking with coal, but not with other types of fuel and only among women (11). Other studies have also reported differences between men and women in the effects of solid fuel burning both for cooking (12), and heating (13). An earlier report from the BOLD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease) study, mostly undertaken in high-income countries, also failed to show an association between airflow obstruction and use of solid fuel (14). Results from trials of solid fuel use reduction are so far inconclusive in relation to the effects on lung function (15, 16). Overall, the evidence supporting an association of COPD (or airflow obstruction) with use of solid fuels for cooking or heating is conflicting and inconsistent.

The main aim of the present analysis was to assess the association of airflow obstruction with self-reported use of open fires burning biomass, or coal, for cooking or heating in the large international, population-based BOLD study. In addition, we performed similar analyses for spirometric restriction, chronic cough, and chronic phlegm.

Methods

Participants

The BOLD study design and rationale have been described elsewhere (17). Representative samples of adults aged 40 years or older were recruited from sites in low-, middle-, and high-income countries. Information on respiratory symptoms and exposure to risk factors was collected through face-to-face interviews conducted by trained and certified staff in the participant’s native language. Four sites did not use the questionnaire on use of open fires: Bergen (Norway); Hannover (Germany); Sydney (Australia); and Uppsala (Sweden). In the 29 remaining sites, 27,534 participants responded to the core questionnaire, of whom 23,250 had acceptable post-bronchodilator spirometry, and 20,746 also provided information on the use of open fires for cooking/heating. Sites where the prevalence of ever having used open fires for cooking/heating was either less than 0.5% (Mumbai [India]) or greater than 99.5% (Tirana [Albania]), Srinagar [India], and Adana [Turkey]) were excluded from the analysis. The present study population consisted of 18,554 individuals from 25 sites (Table 1). All sites received approval from their local ethics committee, and participants provided written informed consent.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants from 25 sites of the BOLD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease) Study with Good Quality Spirometry and Data on Use of Solid Fuels for Cooking or Heating

| Annaba (Algeria) | Salzburg (Austria) | Sèmè-Kpodji (Benin) | Vancouver (BC, Canada) | Guangzhou (China) | London (UK) | Tartu (Estonia) | Reykjavik (Iceland) | Vadu (India) | Chui (Kyrgyztan) | Naryn (Kyrgyztan) | Blantyre (Malawi) | Penang (Malaysia) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 890 | 1245 | 678 | 823 | 459 | 674 | 601 | 756 | 844 | 891 | 859 | 401 | 663 |

| Males, % | 49.9 | 46.3 | 49.3 | 47.2 | 52.0 | 46.3 | 38.9 | 51.2 | 59.8 | 41.5 | 47.7 | 54.1 | 49.2 |

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 53.5 (10.9) | 59.2 (12.1) | 50.5 (9.6) | 56.7 (12.6) | 54.0 (10.6) | 58.0 (12.4) | 59.6 (12.2) | 57.0 (9.5) | 52.3 (10.0) | 53.5 (10.2) | 52.5 (9.9) | 50.6 (9.4) | 54.4 (10.4) |

| Height, cm, mean (SD) | 164.4 (10.0) | 168.9 (9.0) | 165.7 (8.2) | 167.9 (10.1) | 160.3 (8.4) | 167.9 (10.1) | 168.0 (9.7) | 172.7 (9.5) | 158.8 (8.9) | 162.8 (9.2) | 161.9 (9.3) | 162.5 (8.2) | 158.6 (8.3) |

| Never-smokers, % | 61.4 | 49.4 | 98.0 | 47.1 | 54.7 | 36.0 | 55.5 | 39.2 | 88.1 | 62.3 | 69.5 | 83.8 | 74.9 |

| Pack-years, mean (SD)* | 26.9 (20.5) | 25.2 (23.2) | 10.7 (8.8) | 23.0 (25.0) | 26.0 (17.8) | 27.3 (30.1) | 16.5 (15.1) | 21.2 (29.0) | 6.2 (8.7) | 26.1 (21.3) | 18.7 (15.5) | 7.1 (10.5) | 24.9 (21.7) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 28.2 (5.6) | 26.4 (4.3) | 26.2 (5.4) | 26.7 (5.1) | 23.4 (3.3) | 27.3 (5.3) | 28.4 (5.3) | 27.9 (5.0) | 22.1 (3.9) | 28.2 (5.9) | 26.9 (5.1) | 24.5 (5.2) | 26.0 (4.6) |

| Education, yr†, mean (SD) | 7.7 (5.4) | 9.8 (2.2) | 4.4 (4.9) | 15.4 (3.4) | 8.4 (3.9) | 13.6 (3.6) | 13.5 (3.8) | 13.2 (4.4) | 4.3 (4.3) | 9.5 (1.6) | 9.9 (1.5) | 8.4 (4.4) | 8.6 (3.7) |

| Exposure to dust in workplace, yr, mean (SD) | 5.6 (10.3) | 5.2 (11.7) | 5.5 (10.1) | 3.1 (7.3) | 6.9 (11.5) | 4.1 (9.7) | 5.0 (10.1) | 4.2 (9.6) | 1.8 (5.5) | 5.7 (10.9) | 1.0 (5.0) | 3.2 (7.2) | 5.8 (10.7) |

| Use of solid fuels for cooking or heating, % | 57.1 | 16.3 | 96.1 | 17.0 | 99.1 | 61.4 | 91.3 | 19.5 | 79.3 | 85.0 | 99.1 | 86.5 | 72.1 |

| Duration of use of solid fuels, yr‡, mean (SD) | 16.2 (10.5) | 18.9 (13.5) | 24.9 (10.8) | 12.4 (9.5) | 28.0 (10.9) | 16.3 (10.4) | 29.2 (18.8) | 11.1 (6.0) | 39.9 (15.7) | 24.6 (15.2) | 39.8 (16.5) | 21.3 (13.0) | 16.0 (8.6) |

| FEV1, L, mean (SD) | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.9 (0.9) | 2.3 (0.6) | 3.0 (0.9) | 2.4 (0.7) | 2.7 (0.9) | 2.9 (0.9) | 3.0 (0.9) | 2.2 (0.6) | 2.7 (0.8) | 2.8 (0.7) | 2.5 (0.6) | 2.2 (0.6) |

| FVC, L, mean (SD) | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.9 (1.0) | 2.9 (0.7) | 4.0 (1.2) | 3.1 (0.8) | 3.6 (1.1) | 3.8 (1.1) | 4.0 (1.0) | 2.8 (0.7) | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.6 (0.9) | 3.1 (0.7) | 2.7 (0.7) |

| Airflow obstruction, % | 6.4 | 17.3 | 7.3 | 13.3 | 7.7 | 17.6 | 6.2 | 11.3 | 6.1 | 12.5 | 7.8 | 6.9 | 3.4 |

| Spirometric restriction, % | 26.5 | 9.1 | 78.4 | 8.4 | 29.8 | 17.8 | 8.5 | 12.6 | 66.1 | 12.3 | 10.3 | 46.4 | 58.0 |

| Chronic cough, % | 3.0 | 5.9 | 2.3 | 10.9 | 5.7 | 14.8 | 6.8 | 11.6 | 1.9 | 15.2 | 9.9 | 2.4 | 4.5 |

| Chronic phlegm, % | 2.7 | 8.4 | 2.2 | 10.6 | 7.0 | 14.2 | 8.7 | 9.2 | 1.4 | 9.2 | 7.4 | 0.2 | 4.0 |

| Fes (Morocco) | Maastricht (the Netherlands) | Ile-Ife (Nigeria) | Manila (the Philippines) | Nampicuan and Talugtug (the Philippines) | Krakow (Poland) | Lisbon (Portugal) | Riyadh (Saudi Arabia) | Uitsig/Ravensmead (South Africa) | Colombo (Sri Lanka) | Sousse (Tunisia) | Lexington (KY) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 767 | 587 | 884 | 885 | 719 | 518 | 711 | 700 | 840 | 991 | 661 | 507 |

| Males, % | 52.1 | 46.7 | 54.3 | 47.6 | 49.5 | 49.8 | 45.3 | 51.7 | 43.5 | 46.3 | 51.0 | 46.3 |

| Age, yr, mean (SD) | 54.2 (11.9) | 58.5 (11.9) | 53.1 (11.3) | 52.8 (11.0) | 54.2 (10.6) | 56.1 (11.8) | 58.5 (12.0) | 50.3 (7.7) | 53.4 (10.5) | 53.5 (9.3) | 51.9 (9.5) | 57.0 (11.6) |

| Height, cm, mean (SD) | 162.1 (9.1) | 169.0 (9.8) | 164.6 (7.9) | 156.9 (8.5) | 158.7 (8.7) | 166.8 (8.6) | 161.7 (10.0) | 162.2 (8.9) | 162.3 (9.0) | 156.8 (9.3) | 163.8 (9.4) | 168.0 (10.0) |

| Never-smokers, % | 69.8 | 37.6 | 86.5 | 45.2 | 45.3 | 39.7 | 57.3 | 76.4 | 30.3 | 77.5 | 57.1 | 40.8 |

| Pack-years, mean (SD)* | 21.8 (20.2) | 23.2 (19.5) | 5.9 (9.0) | 19.8 (21.5) | 23.7 (19.2) | 26.3 (28.5) | 31.2 (30.5) | 23.8 (20.1) | 17.0 (16.7) | 10.4 (0.0) | 30.7 (22.5) | 41.5 (36.6) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 27.5 (5.2) | 27.5 (4.6) | 25.0 (5.2) | 24.4 (4.7) | 21.6 (4.1) | 27.8 (4.7) | 27.9 (4.7) | 31.3 (6.0) | 27.5 (7.3) | 24.5 (4.7) | 28.8 (5.6) | 30.6 (6.5) |

| Education, yr†, mean (SD) | 4.2 (5.3) | 14.9 (5.1) | 9.4 (5.9) | 9.4 (3.6) | 7.8 (3.6) | 10.4 (3.4) | 8.5 (4.9) | 9.4 (5.5) | 7.8 (3.3) | 9.0 (3.7) | 8.2 (5.2) | 12.8 (3.4) |

| Exposure to dust in workplace, yr, mean (SD) | 8.5 (12.8) | 3.3 (8.9) | 5.2 (10.3) | 7.2 (10.8) | 6.1 (11.7) | 10.3 (13.4) | 10.6 (14.4) | 2.7 (7.9) | 6.9 (10.4) | 6.3 (11.1) | 10.0 (13.0) | 8.2 (12.1) |

| Use of solid fuels for cooking or heating, % | 49.0 | 25.0 | 66.7 | 41.3 | 98.5 | 95.2 | 54.3 | 38.5 | 47.1 | 57.9 | 45.3 | 70.6 |

| Duration of use of solid fuels, yr‡, mean (SD) | 18.6 (11.6) | 11.7 (8.5) | 17.4 (15.7) | 12.3 (9.9) | 37.7 (16.6) | 36.1 (18.2) | 17.2 (10.3) | 21.0 (15.8) | 17.5 (10.4) | 33.1 (17.4) | 19.6 (13.0) | 16.7 (11.4) |

| FEV1, L, mean (SD) | 2.7 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.9) | 2.3 (0.6) | 2.1 (0.6) | 2.1 (0.7) | 2.9 (0.9) | 2.7 (0.9) | 2.5 (0.7) | 2.3 (0.7) | 1.9 (0.5) | 2.8 (0.8) | 2.7 (0.9) |

| FVC, L, mean (SD) | 3.4 (0.9) | 3.8 (1.1) | 2.9 (0.7) | 2.6 (0.7) | 2.7 (0.8) | 3.8 (1.0) | 3.4 (1.1) | 3.0 (0.8) | 3.0 (0.9) | 2.3 (0.6) | 3.5 (0.9) | 3.5 (1.1) |

| Airflow obstruction, % | 8.9 | 18.9 | 7.0 | 9.4 | 15.0 | 13.7 | 8.3 | 3.2 | 19.3 | 7.8 | 5.3 | 14.4 |

| Spirometric restriction, % | 19.4 | 10.2 | 71.5 | 62.6 | 56.7 | 10.1 | 10.7 | 52.9 | 46.8 | 84.1 | 26.2 | 26.3 |

| Chronic cough, % | 10.6 | 5.4 | 0.4 | 6.6 | 7.7 | 7.7 | 10.4 | 12.5 | 11.8 | 7.5 | 11.3 | 19.5 |

| Chronic phlegm, % | 7.3 | 3.2 | 0.4 | 14.6 | 10.3 | 7.7 | 11.9 | 13.0 | 14.3 | 11.5 | 16.3 | 16.8 |

Definition of abbreviation: BMI = body mass index.

Among ever-smokers.

Education, years of schooling completed.

Among those who use solid fuels for cooking or heating.

Use of Solid Fuels for Cooking or Heating

The use of solid fuels was defined based on whether the participant had used an open fire with charcoal, coal, coke, wood, crop residues, or dung as the primary means of cooking or heating the house or water for greater than 6 months in their lifetime. Levels of exposure (years of use and hours per day spent cooking on an open fire) were also assessed.

Lung Function and Respiratory Symptoms

Lung function was assessed by spirometry technicians who were certified before data collection, received regular feedback on quality, and were required to maintain a prespecified quality standard. FEV1 and FVC were measured using the ndd EasyOne Spirometer (ndd Medizintechnik AG) before and 15 minutes after administration of salbutamol (200 μg) from a metered-dose inhaler through a spacer. Each spirogram was centrally reviewed and scored based on the American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society acceptability and reproducibility criteria (18). We defined: 1) airflow obstruction as a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC less than the lower limit of normal (LLN) (19), based on reference equations for white individuals from the third U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (20); and 2) spirometric restriction as a post-bronchodilator FVC less than LLN, based on the same reference population.

Participants were considered to have: 1) chronic cough if they answered “yes” to both “Do you usually cough when you don’t have a cold?” and “Do you cough on most days for as much as three months each year?”; and 2) chronic phlegm if they answered “yes” to both “Do you usually bring up phlegm from your chest, or do you usually have phlegm in your chest that is difficult to bring up when you don’t have a cold?” and “Do you bring up this phlegm on most days for as much as 3 months each year?”

Statistical Analysis

We assessed, by sex, the association of airflow obstruction, spirometric restriction, chronic cough, and chronic phlegm with use of open fires burning solid fuels for cooking/heating using logistic regression models, which were adjusted for age (yr), body mass index (<18.5, 18.5 to <24, 24 to <30, and ≥30 kg/m2), pack-years of smoking, and cumulative exposure to dust in the workplace (yr). The association of each outcome with use of solid fuels was estimated for each site using probability weights to allow for the sampling design (21), and then combined in a random-effects meta-analysis stratified by gross national income (low-/middle- vs. high-income countries) (22). The level of heterogeneity was summarized using the I2 statistic (23). We also regressed FEV1/FVC (%) and FVC (L) as continuous variables against the same independent variables.

In sensitivity analyses, we: 1) restricted the main analysis to never-smokers; and 2) further examined the association of each outcome with use of solid fuels for cooking. These further analyses were stratified by fuel (“charcoal, coal, or coke” or “wood, crop residues, or dung”), use of solid fuels for less than 20 or 20 years or greater, by those usually spending greater than 1 h/d cooking, and by those with or without ventilation (the use of ventilation was assessed by asking whether the participant’s stove or fire was vented to the outside [e.g., through chimney or window]); 3) excluded participants with less than 10 years of use of solid fuels; and 4) used the Global Lung Function Initiative (GLI) 2012 multiethnic equations to calculate the LLN (24). In addition, we assessed the association of airflow obstruction with duration of use of solid fuels (per 10 yr of use).

In an ecological analysis, we plotted the prevalence of each outcome against the proportion using solid fuels for cooking/heating after adjusting for the effects of age, body mass index, pack-years, and exposure to dust in the workplace.

All analyses were conducted using Stata/SE V.14.1 (StataCorp LP), and results considered significant at P less than 0.05. Some of the data from nine sites (six from high-income countries) have been published in an earlier report (14).

Results

The characteristics of the 18,554 participants included in this study are presented in Table 1. There were more females than males, and the mean age ranged from 50.3 to 59.6 years. Cumulative smoking history (i.e., pack-years) varied across sites, and most participants from low-/middle-income sites were never-smokers. The proportion of people who had used solid fuels for cooking/heating varied from 16.3% in Salzburg (Austria) to 99.1% in Guangzhou (China) and Naryn (Kyrgyzstan). The mean duration of use varied from 11.1 years in Reykjavik (Iceland) to 39.9 years in Vadu (India). The prevalence of the outcomes also varied: airflow obstruction from 3.2% in Riyadh (Saudi Arabia) to 19.3% in Uitsig/Ravensmead (South Africa); spirometric restriction from 8.4% in Vancouver (BC, Canada) to 84.1% in Colombo (Sri Lanka); chronic cough from 0.4% in Ile-Ife (Nigeria) to 19.5% in Lexington (KY); and chronic phlegm from 0.4% in Ile-Ife (Nigeria) to 16.8% in Lexington (KY).

Airflow Obstruction and Use of Solid Fuels

Participants who used solid fuels were not more likely to have airflow obstruction than those who did not use solid fuels (Table 2). The adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association between airflow obstruction and use of solid fuels was 1.20 (0.94–1.53) for men and 0.88 (0.67–1.15) for women. The estimates for this association were similar across low-/middle- and high-income sites. Among never-smokers, there was no evidence of an association of airflow obstruction with use of solid fuels (men: OR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.57–1.76) (women: OR, 1.00; 95% CI, 0.76–1.32). The lack of a statistically significant association was also evident when examining it by cooking fuel, cumulative time of use for cooking, and the presence or absence of ventilation (Table 3).

Table 2.

Association of Airflow Obstruction, Spirometric Restriction, Chronic Cough, and Chronic Phlegm with Use of Solid Fuels for Cooking or Heating

| Men |

Women |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) |

I2 (%) | OR (95% CI) |

I2 (%) | |||||||

| uCa:uNCa/nuCa:nuNCa | All Sites | LMIC | HIC | uCa:uNCa/nuCa:nuNCa | All Sites | LMIC | HIC | |||

| Overall | ||||||||||

| Airflow obstruction | 525:3,437/345:2,972 | 1.20 (0.94–1.53) | 1.16 (0.90–1.51) | 1.17 (0.73–1.86) | NS | 439:4,527/380:3,273 | 0.88 (0.67–1.15) | 0.81 (0.55–1.20) | 0.94 (0.64–1.36) | 44.5 |

| Spirometric restriction | 1,786:2,740/1,071:2,374 | 0.89 (0.75–1.06) | 0.89 (0.76–1.05) | 0.89 (0.58–1.37) | NS | 2,327:3,015/1,117:2,646 | 1.03 (0.87–1.21) | 1.02 (0.83–1.25) | 1.04 (0.75–1.43) | NS |

| Chronic cough | 328:3,301/233:3,038 | 0.94 (0.70–1.27) | 1.06 (0.70–1.60) | 0.80 (0.53–1.21) | NS | 384:3,848/311:3,214 | 1.06 (0.79–1.42) | 1.05 (0.68–1.63) | 1.12 (0.79–1.60) | 55.1 |

| Chronic phlegm | 409:3,121/278:2,980 | 1.23 (0.99–1.54) | 1.19 (0.84–1.70) | 1.37 (0.97–1.94) | NS | 308:2,817/294:3,057 | 1.16 (0.94–1.42) | 1.12 (0.93–1.36) | 1.22 (0.76–1.97) | NS |

| Never-smokers | ||||||||||

| Airflow obstruction | 94:1,058/68:997 | 1.00 (0.57–1.76) | 1.15 (0.62–2.14) | 0.81 (0.26–2.48) | NS | 252:3,236/155:2,127 | 1.00 (0.76–1.32) | 1.11 (0.79–1.55) | 0.75 (0.46–1.23) | NS |

| Spirometric restriction | 860:965/449:899 | 0.72 (0.57–0.91) | 0.62 (0.50–0.78) | 1.20 (0.70–2.06) | NS | 2,039:2,223/876:1,717 | 1.01 (0.84–1.21) | 1.01 (0.82–1.23) | 1.03 (0.63–1.69) | NS |

| Chronic cough | 63:913/52:932 | 0.88 (0.55–1.40) | 1.37 (0.69–2.72) | 0.57 (0.29–1.09) | NS | 223:2,598/139:1,860 | 1.33 (0.94–1.89) | 1.36 (0.82–2.25) | 1.30 (0.87–1.94) | 50.7 |

| Chronic phlegm | 99:927/65:997 | 1.57 (0.90–2.74) | 1.54 (0.68–3.51) | 1.58 (0.69–3.62) | NS | 204:2,189/155:2,015 | 1.28 (1.04–1.58) | 1.29 (0.97–1.71) | 1.42 (0.92–2.19) | NS |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; HIC = high-income country; LMIC = low-/middle-income country; NS = non–statistically significant (i.e., P > 0.05) heterogeneity (I2); nuCa = nonusers of solid fuel, cases; nuNCa = nonusers of solid fuel, noncases; OR = odds ratio; uCa = users of solid fuel, cases; uNCa = users of solid fuel, noncases.

Adjusted for age, height, body mass index, pack-years, and cumulative exposure to dusty jobs.

Table 3.

Association of Airflow Obstruction with Use of Solid Fuels for Cooking in the BOLD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease) Study, Restricting the Analysis per Cooking Characteristics

| Men |

Women |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooking fuel | uCa:uNCa/nuCa:nuNCa | OR (95% CI) | I2 (%) | uCa:uNCa/nuCa:nuNCa | OR (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

| Charcoal, coal, or coke* | 154:848/312:2,642 | 1.19 (0.72–1.96) | 50.9 | 196:1,751/329:2,238 | 1.12 (0.78–1.62) | NS |

| 1–19 yr | 75:442/307:2,605 | 1.15 (0.69–1.92) | 43.3 | 72:569/328:2,198 | 1.15 (0.69–1.90) | 47.3 |

| 20+ yr | 79:379/238:1,858 | 1.00 (0.46–2.14) | 54.7 | 122:1,099/329:223 | 1.29 (0.76–2.18) | NS |

| >1 h/d | 4:17/22:144 | 1.10 (0.32–3.75) | NS | 47:690/32:457 | 0.63 (0.25–1.62) | NS |

| with ventilation | 3:15/22:144 | 0.82 (0.24–2.75) | NS | 47:665/32:457 | 0.68 (0.26–1.81) | NS |

| without ventilation | 1:2/17:119 | 6.69 (0.17–256) | NA | — | — | — |

| Wood, crop residues, or dung* | 355:2,309/333:2,839 | 1.20 (0.89–1.60) | NS | 265:2,900/373:3,096 | 0.96 (0.70–1.32) | 44.2 |

| 1–19 yr | 127:822/330:2,747 | 1.32 (0.94–1.84) | NS | 86:910/361:2,972 | 1.00 (0.75–1.34) | NS |

| 20+ yr | 218:1,412/312:2,480 | 1.26 (0.85–1.87) | NS | 177:1,817/300:2,491 | 1.18 (0.80–1.72) | NS |

| >1 h/d | 20:137/27:265 | 1.10 (0.61–1.99) | NS | 82:1,063/49:814 | 1.20 (0.48–3.02) | 69.2 |

| with ventilation | 18:118/27:265 | 1.20 (0.68–2.10) | NS | 79:996/49:814 | 1.26 (0.49–3.26) | 67.2 |

| without ventilation | 2:4/5:111 | 13.4 (0.83–218) | NA | 3:39/15:299 | 0.87 (0.15–5.08) | NS |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; NA = not applicable (one site only); NS = non–statistically significant (i.e., P > 0.05) heterogeneity (I2); nuCa = nonusers of solid fuel, cases; nuNCa = nonusers of solid fuel, noncases; OR = odds ratio; uCa = users of solid fuel, cases; uNCa = users of solid fuel, noncases.

Adjusted for age, height, body mass index, pack-years, and cumulative exposure to dusty jobs. Dashes indicate not enough observations for model to converge.

Versus no use of solid fuels for cooking.

There was no association between the FEV1/FVC and use of solid fuels (see Table E1 in the online supplement). Exclusion of participants with fewer than 10 years of solid fuel use (Tables E2 and E3) and use of GLI2012 LLN equations did not change the results (Table 4). There was no significant exposure–response trend per 10 years of use (Table 5 and Table E4).

Table 4.

Association of Airflow Obstruction and Spirometric Restriction with Use of Solid Fuels for Cooking or Heating, Using Global Lung Function Initiative 2012 Equations for Different Ethnicities

| Men |

Women |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) |

I2 | OR (95% CI) |

I2 | |||||||

| uCa:uNCa/nuCa:nuNCa | All Sites | LMIC | HIC | uCa:uNCa/nuCa:nuNCa | All Sites | LMIC | HIC | |||

| Airflow obstruction | 605:3,631/373:3,040 | 1.14 (0.96–1.36) | 1.13 (0.92–1.39) | 1.15 (0.81–1.63) | NS | 408:4,188/326:3,314 | 1.01 (0.77–1.33) | 1.03 (0.72–1.47) | 0.98 (0.63–1.54) | NS |

| Spirometric restriction | 736:3,691/516:2,906 | 0.84 (0.70–1.00) | 0.87 (0.72–1.06) | 0.71 (0.48–1.05) | NS | 926:4,181/522:3,236 | 0.93 (0.80–1.08) | 0.94 (0.79–1.12) | 0.92 (0.62–1.38) | NS |

For definition of abbreviations, see Table 2.

Adjusted for age, height, body mass index, pack-years, and cumulative exposure to dusty jobs. White subjects: Annaba (Algeria), Krakow (Poland), Lexington (KY), Lisbon (Portugal), London (United Kingdom), Maastricht (the Netherlands), Reykjavik (Iceland), Salzburg (Austria), Sousse (Tunisia), Tartu (Estonia), and Vancouver (BC, Canada). Black subjects (and Indian subcontinent; although this subcontinent is not covered in Global Lung Function Initiative 2012, there is evidence showing that these groups are similar in terms of lung function [32]): Sèmè-Kpodji (Benin), Blantyre (Malawi), Uitsig/Ravensmead (South Africa), Ile-Ife (Nigeria), Vadu (India), and Colombo (Sri Lanka). Southeast Asian subjects: Guangzhou (China) and Penang (Malaysia). Other or mixed subjects: Fes (Morocco), Chui (Kyrgyztan), Naryn (Kyrgyztan), Manila (the Philippines), Nampicuan and Talugtug (the Philippines), and Riyadh (Saudi Arabia).

Table 5.

Association of Airflow Obstruction with Duration of Use of Solid Fuels for Cooking or Heating

| Men |

Women |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) |

I2 (%) | OR (95% CI) |

I2 (%) | |||||||

| Airflow Obstruction | Ca:NCa | All Sites | LMIC | HIC | Ca:NCa | All Sites | LMIC | HIC | ||

| Overall | ||||||||||

| Per 10 yr of use | 961:7,425 | 1.07 (0.98–1.16) | 1.08 (0.98–1.19) | 1.05 (0.88–1.26) | 56.2 | 905:8,913 | 1.00 (0.90–1.11) | 0.98 (0.85–1.13) | 1.04 (0.92–1.17) | 64.8 |

| Per 10 yr of use, excluding those with <10 yr of use | 832:6,404 | 1.00 (0.99–1.16) | 1.09 (0.99–1.19) | 1.03 (0.86–1.24) | 37.6 | 787:7,376 | 1.01 (0.91–1.11) | 0.98 (0.85–1.13) | 1.08 (0.96–1.20) | 57.3 |

| Never-smokers | ||||||||||

| Per 10 yr of use | 205:2,714 | 1.02 (0.87–1.21) | 1.09 (0.97–1.22) | 0.80 (0.43–1.49) | 47.2 | 488:6,737 | 1.08 (0.99–1.18) | 1.09 (0.98–1.22) | 1.05 (0.88–1.26) | 36.9 |

| Per 10 yr of use, excluding those with <10 yr of use | 172:2,154 | 1.00 (0.85–1.18) | 1.08 (0.95–1.22) | 0.82 (0.48–1.40) | 44.2 | 405:5,384 | 1.08 (0.99–1.19) | 1.08 (0.96–1.21) | 1.13 (0.98–1.32) | NS |

Definition of abbreviations: Ca = cases; CI = confidence interval; HIC = high-income country; LMIC = low-/middle-income country; NCa = noncases; NS = non–statistically significant (i.e., P > 0.05) heterogeneity (I2); OR = odds ratio.

Adjusted for age, height, body mass index, pack-years, and cumulative exposure to dusty jobs.

Spirometric Restriction and Use of Solid Fuels

There was no association between spirometric restriction and use of solid fuels among either men (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.75–1.06) or women (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.87–1.21) (Table 2). This pattern was similar across low-/middle- and high-income sites. Among male never-smokers, there was evidence of an inverse association between spirometric restriction and use solid fuels (OR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.57–0.91). An association between spirometric restriction and use of solid fuels for cooking was still not present after examining the association by cooking fuel, cumulative time of use for cooking, and the presence of ventilation. Women who had ever used open fires burning charcoal, coal, or coke for 20 years or longer, more than 1 h/d, and without ventilation, were more likely to have restriction, whereas men who had ever used an open fire burning wood, crop residues, or dung were less likely to show restriction (Table 6).

Table 6.

Association of Spirometric Restriction with Use of Solid Fuels for Cooking in the BOLD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease) Study, Restricting the Analysis per Cooking Characteristics

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooking Fuel | uCa:uNCa/nuCa:nuNCa | OR (95% CI) | I2 (%) | uCa:uNCa/nuCa:nuNCa | OR (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

| Charcoal, coal, or coke* | 444:831/882:2,122 | 0.83 (0.53–1.22) | 54.0 | 715:1,184/888:2,522 | 1.03 (0.75–1.43) | 49.9 |

| 1–19 yr | 231:373/775:1,926 | 0.81 (0.54–1.22) | 44.7 | 285:479/888:2,510 | 1.09 (0.80–1.48) | NS |

| 20+ yr | 210:415/803:1,646 | 0.82 (0.53–1.26) | NS | 428:678/858:2,281 | 1.14 (0.69–1.90) | 63.7 |

| >1 h/d | 22:22/271:184 | 0.66 (0.18–2.52) | NS | 253:235/587:748 | 0.92 (0.50–1.72) | 62.5 |

| with ventilation | 20:18/271:184 | 0.70 (0.23–2.13) | NS | 224:228/587:748 | 0.82 (0.44–1.54) | 59.8 |

| without ventilation | — | — | — | 17:7/186:295 | 3.15 (1.19–8.29) | NS |

| Wood, crop residues, or dung* | 1,390:1,631/1,070:2,367 | 0.93 (0.79–1.10) | NS | 1,784:1,697/1,117:2,642 | 1.06 (0.88–1.28) | NS |

| 1–19 yr | 512:657/1,064:2,343 | 0.88 (0.73–1.07) | NS | 599:656/1,106:2,631 | 0.97 (0.74–1.28) | 39.6 |

| 20+ yr | 857:948/1,014:2,077 | 0.94 (0.73–1.22) | NS | 1,164:1,014/1,064:2,204 | 1.07 (0.81–1.40) | NS |

| >1 h/d | 107:59/272:194 | 0.61 (0.33–1.11) | NS | 508:386/587:748 | 0.88 (0.57–1.35) | 51.9 |

| with ventilation | 96:45/272:194 | 0.66 (0.43–1.00) | NS | 451:353/587:748 | 0.91 (0.56–1.48) | 57.1 |

| without ventilation | 10:12/209:49 | 0.16 (0.04–0.60) | NS | 52:32/511:548 | 0.64 (0.31–1.32) | NS |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; NS = non–statistically significant (i.e., P > 0.05) heterogeneity (I2); nuCa = nonusers of solid fuel, cases; nuNCa = nonusers of solid fuel, noncases; OR = odds ratio; uCa = users of solid fuel, cases; uNCa = users of solid fuel, noncases.

Adjusted for age, height, body mass index, pack-years, and cumulative exposure to dusty jobs. Dashes indicate not enough observations for model to converge.

Versus no use of solid fuels for cooking.

There was no association between the FVC and use of solid fuels (Table E1). Exclusion of participants with greater than 6 months, but less than 10 years of solid fuel use (Tables E2 and E3), and use of the GLI2012 LLN equations did not change the results (Table 4).

Chronic Cough and Use of Solid Fuels

Chronic cough was not associated with use of solid fuels (men: OR, 0.98 [95% CI 0.71–1.34]; women: OR, 1.04 [95% CI, 0.77–1.41]; Table 2). No association between chronic cough and use of solid fuels was found in any of the sensitivity analyses, either restricting the analysis to never-smokers (Table 2) or by type of cooking fuel, cumulative time of exposure, or the presence of ventilation (Table 7).

Table 7.

Association of Chronic Cough with Use of Solid Fuels for Cooking in the BOLD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease) Study, Restricting the Analysis per Cooking Characteristics

| Men | Women |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooking Fuel | uCa:uNCa/nuCa:nuNCa | OR (95% CI) | I2 (%) | uCa:uNCa/nuCa:nuNCa | OR (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

| Charcoal, coal, or coke* | 91:798/174:2,151 | 0.95 (0.62–1.47) | NS | 155:1,168/303:2,837 | 1.30 (0.87–1.96) | 40.9 |

| 1–19 yr | 44:380/171:2,082 | 0.88 (0.48–1.60) | NS | 66:433/303:2,820 | 1.49 (0.90–2.49) | 44.4 |

| 20+ yr | 45:348/86:1,025 | 1.15 (0.42–3.11) | 58.8 | 89:697/248:2,141 | 1.29 (0.57–2.91) | 72.1 |

| >1 h/d | 2:19/16:150 | 1.24 (0.11–14.1) | NS | 55:502/65:533 | 0.84 (0.16–4.32) | 84.5 |

| with ventilation | 1:4/6:24 | 3.76 (0.63–22.4) | NA | 52:485/34:367 | 0.91 (0.14–6.12) | 88.8 |

| without ventilation | 1:2/10:126 | 3.04 (0.22–41.9) | NA | 3:7/39:216 | 6.05 (0.12–300) | 81.7 |

| Wood, crop residues or dung* | 210:2,108/168:2,472 | 1.21 (0.80–1.85) | 55.7 | 251:2,668/290:3,071 | 1.17 (0.78–1.75) | 66.3 |

| 1–19 yr | 98:844/150:2,156 | 1.51 (0.83–2.72) | 58.3 | 87:922/288:3,007 | 1.15 (0.78–1.68) | NS |

| 20+ yr | 107:1,121/153:2,188 | 1.14 (0.70–1.85) | 47.6 | 164:1,551/215:1,880 | 1.47 (0.82–2.64) | 70.8 |

| >1 h/d | 5:98/21:284 | 1.20 (0.11–13.0) | 83.2 | 82:831/84:778 | 1.32 (0.44–3.99) | 82.8 |

| with ventilation | 5:83/21:284 | 1.47 (0.12–17.8) | 81.2 | 74:778/53:612 | 1.32 (0.36–4.75) | 84.7 |

| without ventilation | — | — | — | 8:39/56:463 | 2.77 (0.57–13.6) | 67.7 |

For definition of abbreviations see Table 3.

Adjusted for age, height, body mass index, pack-years, and cumulative exposure to dusty jobs. Dashes indicate not enough observations for model to converge.

Versus no use of solid fuels for cooking.

Exclusion of participants with greater than 6 months, but less than 10 years of solid fuel use, did not change the results (Table E2).

Chronic Phlegm and Use of Solid Fuels

Overall, chronic phlegm was not associated with the use of solid fuels among either men (OR, 1.23; 95% CI, 0.99–1.54) or women (OR, 1.16; 95% CI, 0.93–1.45). However, among never-smokers, women who ever used solid fuels were 28% more likely to have chronic phlegm compared with women who never used solid fuels (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.04–1.58; Table 2). Among men, the association of chronic phlegm with use of open fires was significant in those who used charcoal, coal, or coke for 20 years or greater and in those who used wood, crop residues, or dung and had been exposed for less than 20 years. Among women, the association was stronger in those who used either of the two groups of solid fuels for 20 years or greater (Table 8).

Table 8.

Association of Chronic Phlegm with Use of Solid Fuels for Cooking in the BOLD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease) Study, Restricting the Analysis per Cooking Characteristics

| Men | Women |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooking Fuel | uCa:uNCa/nuCa:nuNCa | OR (95% CI) | I2 (%) | uCa:uNCa/nuCa:nuNCa | OR (95% CI) | I2 (%) |

| Charcoal, coal, or coke* | 108:764/226:2,236 | 1.28 (0.86–1.92) | NS | 102:668/268:2,713 | 1.73 (1.22–2.44) | NS |

| 1–19 yr | 53:385/225:2,187 | 1.19 (0.68–2.06) | NS | 49:275/244:2,197 | 1.78 (0.81–3.95) | 75.3 |

| 20+ yr | 54:327/123:1,079 | 1.74 (1.09–2.78) | NS | 53:307/268:2,713 | 2.36 (1.47–3.77) | NS |

| >1 h/d | 6:15/26:140 | 0.89 (0.15–5.36) | NS | 25:177/75:743 | 1.91 (0.79–4.61) | NS |

| with ventilation | 4:14/26:140 | 0.72 (0.20–2.55) | NS | 20:162/47:574 | 2.02 (0.57–7.11) | 72.0 |

| without ventilation | 2:1/20:116 | 11.3 (0.70–182) | NA | 5:7/49:361 | 8.18 (0.97–69.3) | NS |

| Wood, crop residues or dung* | 267:2,040/248:2,514 | 1.40 (1.03–1.89) | NS | 201:1,747/294:3,057 | 1.41 (0.98–2.03) | 62.7 |

| 1–19 yr | 121:807/214:2,082 | 1.62 (1.04–2.51) | NS | 90:810/284:2,847 | 1.17 (0.67–2.05) | 67.8 |

| 20+ yr | 142:1,149/205:2,050 | 1.31 (0.79–2.15) | 53.0 | 110:874/260:2,552 | 2.09 (1.31–3.34) | 53.8 |

| >1 h/d | 13:90/32:273 | 2.36 (0.12–47.8) | 87.3 | 53:504/76:808 | 1.76 (0.87–3.60) | NS |

| with ventilation | 11:77/32:273 | 1.92 (0.15–24.4) | 82.8 | 44:449/48:639 | 1.74 (0.91–3.34) | NS |

| without ventilation | 1:13/20:116 | 0.41 (0.04–3.98) | NA | 9:38/59:492 | 2.92 (0.36–23.8) | 79.9 |

For definition of abbreviations see Table 3.

Adjusted for age, height, body mass index, pack-years, and cumulative exposure to dusty jobs.

Versus no use of solid fuels for cooking.

Exclusion of participants with fewer than 10 years of solid fuel use did not change the results (Table E2).

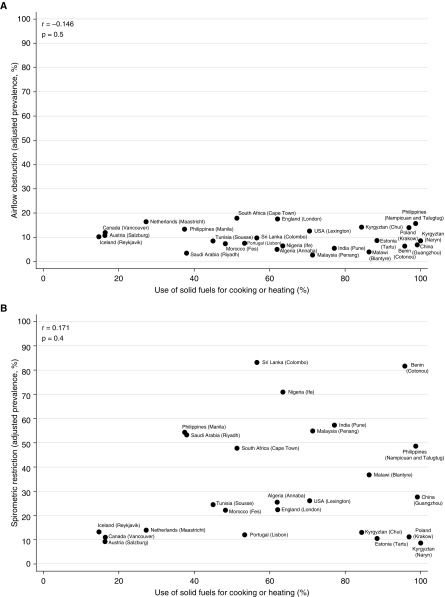

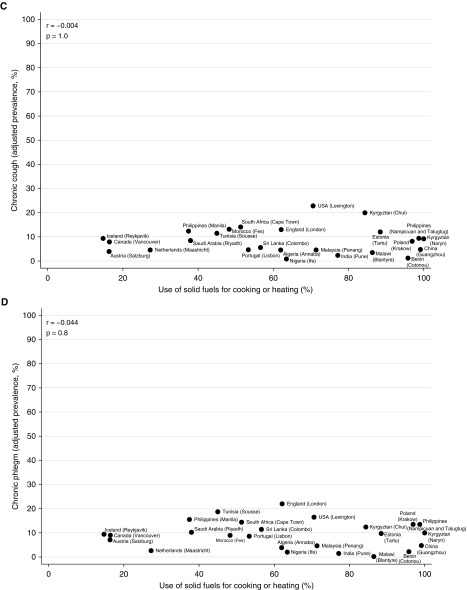

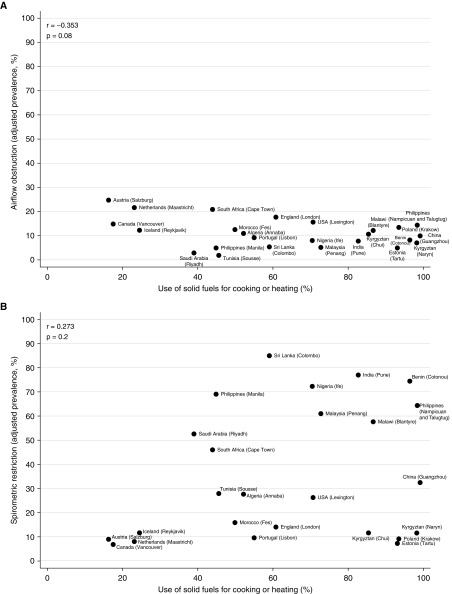

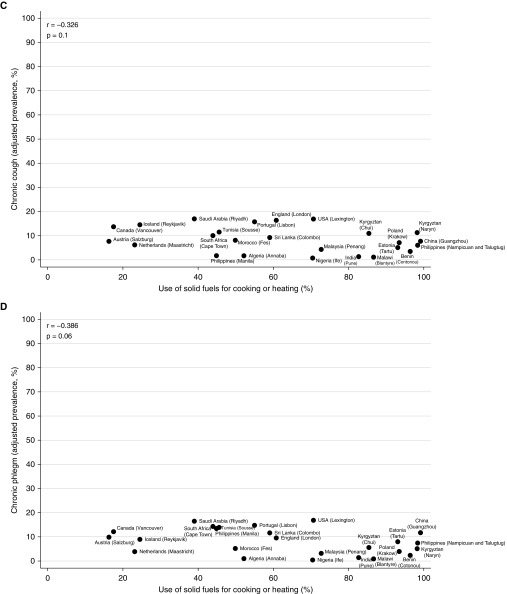

Ecological Analysis

At an aggregate level, there was no strong or significant correlation between the prevalence of airflow obstruction (men: r, −0.146; P, 0.5) (women: r, −0.353; P, 0.08), spirometric restriction (men: r, 0.171; P, 0.4) (women: r, 0.273; P, 0.2), chronic cough (men: r, −0.004; P, 1.0) (women: r, −0.326; P, 0.1), or chronic phlegm (men: r, −0.044; P, 0.8) (women: r, −0.386; P, 0.06), and use of solid fuels for cooking/heating (Figures 1 and 2). The weak correlation with spirometric restriction was strongly influenced by four sites in high-income countries (Iceland, the Netherlands, Canada, and Austria) with low levels of restriction, a finding typical of high-income countries, and low use of solid fuels.

Figure 1.

Correlation of airflow obstruction (A), spirometric restriction (B), chronic cough (C), and chronic phlegm (D) with use of solid fuels for cooking or heating in men in the BOLD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease) study.

Figure 2.

Correlation of airflow obstruction (A), spirometric restriction (B), chronic cough (C), and chronic phlegm (D) with use of solid fuels for cooking or heating in women in the BOLD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease) study.

Discussion

In this population-based study of adults, airflow obstruction was not associated with self-reported use of solid fuels for cooking/heating. The same was true for spirometric restriction and chronic cough. These findings were similar in low-/middle- and high-income sites, and are unlikely to be confounded by smoking, as they were also observed among never-smokers. The only significant association was for a 28% increase in risk of chronic phlegm among women who had never smoked, but had used solid fuels for cooking/heating. The findings were similar, but not significant, for men and for all participants regardless of smoking status.

The strengths of this study are: 1) its large sample size and the inclusion of many sites; 2) the use of a standardized protocol for spirometry and questionnaires for collecting data on risk factors across sites; 3) the use of post-bronchodilator spirometric measurements; and 4) the central quality control of all the spirometry and rigorous training of all study staff.

Nevertheless, this study also has limitations. As this is a cross-sectional study, we are unable to address temporality and draw firm conclusions in terms of causation. A longitudinal study showing no greater rate of lung function decline in the exposed group would be less open to confounding, and a negative randomized trial would be even stronger evidence. The information on solid fuel use was self-reported, and this may have led to exposure misclassification. Even nondifferential (unbiased) misclassification of the exposure will tend to reduce the estimate of the association between the exposure and the outcome. It may also be argued that the reporting of solid fuel use differs between low-/middle- and high-income countries. This is most likely to have influenced the ecological analyses, but is unlikely to have had much influence on the other analyses, as there was little evidence of heterogeneity in the results from different sites.

Assessment of lifetime exposure to open fires burning solid fuels was based on participants’ recall. Although direct measurement of the concentrations of pollutants at an individual level would provide more precise assessments of current levels of exposure, these are less relevant to the study of chronic conditions that develop over many years, and all studies of chronic long-term effects have relied on a history of fuel use. We did not find an association between solid fuel use and airflow obstruction among people who had used this type of fuel for 10 years or greater, nor between increasing duration of use and any of the outcomes. Further restricting analyses to those who had been exposed for at least 20 years, for greater than 1 h/d, and with no ventilation did not change these conclusions. However, we had limited power to assess the effect of ventilation.

A frequent explanation that is given for negative findings in relation to indoor air pollution and lung function is that the exposure has been mismeasured and that regression-dilution bias may have led to underestimation of the risks. This is unlikely to explain the difference between our results and the results of the earlier meta-analyses (6–10). First, the assessments that we have made are not significantly worse than the measures that have been used in the past to support an association, but have been better standardized. Second, our conclusion is supported by the ecological analysis, which shows no significant association between the prevalence of the different outcomes and the prevalence of solid fuel use. As the exposure in this analysis is a summary of all the individual exposure measures in the sample, it is less prone to random error. Finally, the random error in answering simple questions on lifetime use of solid fuel is likely to be less marked than the random sampling error implicit in estimating levels of exposure over a lifetime from very short-term recent measurements. This may partly explain why associations reported from studies that have used an exposure history have not been replicated with measured exposures of air pollution (25).

Ecological data have been used in the past to argue for the potential importance of exposure to solid fuel burning in explaining the global distribution of mortality from COPD, but we have failed to show any clear association between the prevalence of spirometric measurements and the prevalence of use of solid fuel. In the absence of such an association, it is unlikely that a policy implemented at an area level to reduce exposure would have any marked effect on prevalence. We found no convincing evidence that the prevalence of airflow obstruction or any other abnormality was associated with the use of solid fuel after adjusting for the individual effects of smoking and other confounders. Although ecological analyses have their weaknesses, these are different from analyses based on individuals. The lack of association at both levels supports the negative finding.

Use of the NHANES reference equations for white subjects in our spirometry measurements may be thought to overstate lung function abnormality in some study sites, but is unlikely to affect these analyses. Reference equations do not define illness, but an arbitrary level of lung function (defined here as the upper bound for the lowest 5% of the “normal”—asymptomatic, nonsmoking—population). It is largely immaterial whether the definition uses the lower 1, 5, or 50%, and, as each site is analyzed separately in our analysis, the association with fuel use within each site will not be greatly affected by the choice of the cut point. To check this assumption, we reran our main results using the GLI2012 multiethnic reference equations and using the continuous outcome measures of FEV1/FVC and FVC, which are not dependent on any reference equation. None of these analyses showed a significant change in the conclusions.

Our findings on airflow obstruction disagree with five systematic reviews (6–10). However, these reviews assessed a mixture of noncommensurate outcomes, and demonstrated clear publication bias, as acknowledged by their authors. Two other large studies have recently failed to find a positive and consistent association between airflow obstruction/COPD and solid fuel use (11, 13).

Experimental studies have explored whether there is a causal relationship between biomass smoke and airflow obstruction by reducing exposure to biomass smoke. For example, a randomized, controlled stove intervention trial among Guatemalan women, with personal exposure and spirometry measurements, reported an exposure–response relationship between exhaled carbon monoxide, used as a surrogate of recent exposure to biomass smoke, and lung function (26), but failed to show an improvement in lung function after a reduction in wood smoke exposure (27). A similar study with Mexican women reported a reduction in the decline of FEV1 among those who used the intervention stove, but no significant improvement in the FEV1/FVC after the intervention, and no effect in the more reliable analysis by intention to treat (15). A study in China reported a reduction in the risk of COPD defined as an FEV1/FVC less than 0.7 after improvement in the type of stoves and fuel, but this finding was not supported by results for the continuous outcome, FEV1/FVC (28). Although experimental studies are regarded as the gold standard for demonstrating causality, these broadly negative studies are not decisive. Airflow limitation develops over a long period of time, and these trials had limited power to show a change in decline in lung function over time.

A lack of association can never be proven, but the evidence that indoor air pollution is responsible for a substantial amount of the airflow obstruction in low-/middle-income countries comes from meta-analyses that have been overinterpreted. The observation in this study, that airflow obstruction, spirometric restriction, and chronic cough were not associated with use of solid fuels, does not mean that this exposure is not harmful to humans. We found that chronic phlegm is more likely to occur among people who used solid fuels and, although chronic bronchitis has a relatively weak effect on survival compared with the effect of poor lung function (29), chronic bronchitis has a serious impact on quality of life that may exceed the effects of poor lung function (30). Moreover, there are many other conditions that have been shown by at least some studies to be associated with high exposures to the burning of solid fuels, including childhood pneumonias and airway malignancies (31).

We cannot exclude a small effect of solid fuel use on lung function and, where this exposure is common, it could still pose a risk to health. However, there is no evidence that solid fuel use is likely to explain a substantial component of airflow obstruction or of COPD. These remain unexplained, even though they are among the most important causes of death in poorer regions of the world. An explanation for this excess mortality is still urgently needed.

In summary, in this population-based study, airflow obstruction was not associated with self-reported use of solid fuels for cooking/heating. However, this is not a definitive study. Future long-term longitudinal studies in low-income countries could inform whether airflow obstruction and mortality ascribed to COPD are temporally associated with exposure to solid fuel smoke and whether different fuels have different effects.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the participants and field workers of this study for their time and cooperation, the BOLD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease) Coordinating Centre (UK) members not included in the author list for their technical and scientific support, and the reviewers and editor for helping to improve the manuscript.

The BOLD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease) Collaborative Research Group collaborators: NanShan Zhong (Principal Investigator [PI]), Shengming Liu, Jiachun Lu, Pixin Ran, Dali Wang, Jingping Zheng, and Yumin Zhou (Guangzhou Institute of Respiratory Diseases, Guangzhou Medical College, Guangzhou, China); Ali Kocabaş (PI), Attila Hancioglu, Ismail Hanta, Sedat Kuleci, Ahmet Sinan Turkyilmaz, Sema Umut, and Turgay Unalan (Department of Chest Diseases, Cukurova University School of Medicine, Adana, Turkey); Michael Studnicka (PI), Torkil Dawes, Bernd Lamprecht, and Lea Schirhofer (Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Paracelsus Medical University, Salzburg, Austria); Eric Bateman (PI), Anamika Jithoo (PI), Desiree Adams, Edward Barnes, Jasper Freeman, Anton Hayes, Sipho Hlengwa, Christine Johannisen, Mariana Koopman, Innocentia Louw, Ina Ludick, Alta Olckers, Johanna Ryck, and Janita Storbeck, (University of Cape Town Lung Institute, Cape Town, South Africa); Thorarinn Gislason (PI), Bryndis Benedikdtsdottir, Kristin Jörundsdottir, Lovisa Gudmundsdottir, Sigrun Gudmundsdottir, and Gunnar Gundmundsson, (Department of Allergy, Respiratory Medicine, and Sleep, Landspitali University Hospital, Reykjavik, Iceland); Ewa Nizankowska-Mogilnicka (PI), Jakub Frey, Rafal Harat, Filip Mejza, Pawel Nastalek, Andrzej Pajak, Wojciech Skucha, Andrzej Szczeklik, and Magda Twardowska, (Division of Pulmonary Diseases, Department of Medicine, Jagiellonian University School of Medicine, Krakow, Poland); Tobias Welte (PI), Isabelle Bodemann, Henning Geldmacher, and Alexandra Schweda-Linow (Hannover Medical School, Hannover, Germany); Amund Gulsvik (PI), Tina Endresen, and Lene Svendsen (Department of Thoracic Medicine, Institute of Medicine, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway); Wan C. Tan (PI) and Wen Wang (iCapture Center for Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Research, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada); David M. Mannino (PI), John Cain, Rebecca Copeland, Dana Hazen, and Jennifer Methvin, (University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY); Renato B. Dantes (PI), Lourdes Amarillo, Lakan U. Berratio, Lenora C. Fernandez, Norberto A. Francisco, Gerard S. Garcia, Teresita S. de Guia, Luisito F. Idolor, Sullian S. Naval, Thessa Reyes, Camilo C. Roa, Jr., Ma. Flordeliza Sanchez, and Leander P. Simpao (Philippine College of Chest Physicians, Manila, the Philippines); Christine Jenkins (PI), Guy Marks (PI), Tessa Bird, Paola Espinel, Kate Hardaker, and Brett Toelle (Woolcock Institute of Medical Research, Sydney, NSW, Australia), Peter GJ Burney (PI), Caron Amor, James Potts, Michael Tumilty, and Fiona McLean (National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, London, UK), E. F. M. Wouters and G. J. Wesseling (Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, the Netherlands); Cristina Bárbara (PI), Fátima Rodrigues, Hermínia Dias, João Cardoso, João Almeida, Maria João Matos, Paula Simão, Moutinho Santos, and Reis Ferreira (the Portuguese Society of Pneumology, Lisbon, Portugal); Christer Janson (PI), Inga Sif Olafsdottir, Katarina Nisser, Ulrike Spetz-Nyström, Gunilla Hägg, and Gun-Marie Lund (Department of Medical Sciences: Respiratory Medicine and Allergology, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden); Rain Jõgi (PI), Hendrik Laja, Katrin Ulst, Vappu Zobel, and Toomas-Julius Lill (Lung Clinic, Tartu University Hospital, Tartu, Estonia); Parvaiz A Koul (PI), Sajjad Malik, Nissar A Hakim, and Umar Hafiz Khan (Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar, J&K, India); Rohini Chowgule (PI), Vasant Shetye, Jonelle Raphael, Rosel Almeda, Mahesh Tawde, Rafiq Tadvi, Sunil Katkar, Milind Kadam, Rupesh Dhanawade, and Umesh Ghurup (Indian Institute of Environmental Medicine, Mumbai, India); Imed Harrabi (PI), Myriam Denguezli, Zouhair Tabka, Hager Daldoul, Zaki Boukheroufa, Firas Chouikha, and Wahbi Belhaj Khalifa (University Hospital Farhat Hached, Faculté de Médecine, Sousse, Tunisia); Luisito F. Idolor (PI), Teresita S. de Guia, Norberto A. Francisco, Camilo C. Roa, Fernando G. Ayuyao, Cecil Z. Tady, Daniel T. Tan, Sylvia Banal-Yang, Vincent M. Balanag, Jr., Maria Teresita N. Reyes, and Renato. B. Dantes (Lung Centre of the Philippines, Philippine General Hospital, Nampicuan and Talugtug, the Philippines); Sanjay Juvekar (PI), Siddhi Hirve, Somnath Sambhudas, Bharat Chaidhary, Meera Tambe, Savita Pingale, Arati Umap, Archana Umap, Nitin Shelar, Sampada Devchakke, Sharda Chaudhary, Suvarna Bondre, Savita Walke, Ashleshsa Gawhane, Anil Sapkal, Rupali Argade, and Vijay Gaikwad (Vadu Health and Demographic Surveillance System, King Edward Memorial Hospital Research Centre Pune, Pune India); Sundeep Salvi (PI), Bill Brashier, Jyoti Londhe, and Sapna Madas (Chest Research Foundation, Pune India); Mohamed C Benjelloun (PI), Chakib Nejjari, Mohamed Elbiaze, and Karima El Rhazi (Laboratoire d’épidémiologie, Recherche Clinique et Santé Communautaire, Fès, Morroco); Daniel Obaseki (PI), Gregory Erhabor, Olayemi Awopeju, and Olufemi Adewole (Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria); M. Al Ghobain (PI), H. Alorainy (PI), E. El-Hamad, M. Al Hajjaj, A. Hashi, R. Dela, R. Fanuncio, E. Doloriel, I. Marciano, and L. Safia (Saudi Thoracic Society, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia); Talant M. Sooronbaev (PI), Bermet M. Estebesova, Meerim Akmatalieva, Saadat Usenbaeva, Jypara Kydyrova, Eliza Bostonova, Ulan Sheraliev, Nuridin Marajapov, Nurgul Toktogulova, Berik Emilov, Toktogul Azilova, Gulnara Beishekeeva, Nasyikat Dononbaeva, and AijamalTabyshova (Pulmunology and Allergology Department, National Centre of Cardiology and Internal Medicine, Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan); Kevin Mortimer (PI), Wezzie Nyapigoti, Ernest Mwangoka, Mayamiko Kambwili, Martha Chipeta, Gloria Banda, Suzgo Mkandawire, and Justice Banda (the Malawi Liverpool Wellcome Trust, Blantyre, Malawi); Asma Elsony (PI), Hana A. Elsadig, Nada Bakery Osman, Bandar Salah Noory, Monjda Awad Mohamed, Hasab Alrasoul Akasha Ahmed Osman, Namarig Moham ed Elhassan, Abdel Mu‘is El Zain, Marwa Mohamed Mohamaden, Suhaiba Khalifa, Mahmoud Elhadi, Mohand Hassan, and Dalia Abdelmonam (the Epidemiological Laboratory, Khartoum, Sudan); Hasan Hafizi (PI), Anila Aliko, Donika Bardhi, Holta Tafa, Natasha Thanasi, Arian Mezini, Alma Teferici, Dafina Todri, Jolanda Nikolla, and Rezarta Kazasi (Tirana University Hospital Shefqet Ndroqi, Albania); Hamid Hacene Cherkaski (PI), Amira Bengrait, Tabarek Haddad, Ibtissem Zgaoula, Maamar Ghit, Abdelhamid Roubhia, Soumaya Boudra, Feryal Atoui, Randa Yakoubi, Rachid Benali, Abdelghani Bencheikh, and Nadia Ait-Khaled (Faculté de Médecine Annaba, Service de Epidémiologie et Médecine Préventive, El Hadjar, Algeria); Akramul Islam (PI), Syed Masud Ahmed (Co-PI), Shayla Islam, Qazi Shafayetul Islam, Mesbah-Ul-Haque, Tridib Roy Chowdhury, Sukantha Kumar Chatterjee, Dulal Mia, Shyamal Chandra Das, Mizanur Rahman, Nazrul Islam, Shahaz Uddin, Nurul Islam, Luiza Khatun, Monira Parvin, Abdul Awal Khan, and Maidul Islam (James P. Grant School of Public Health, BRAC [Building Resources Across Communities] University, Institute of Global Health, Dhaka, Bangladesh); Li-Cher Loh (PI), Abdul Rashid, and Siti Sholehah (Penang Medical College, Penang, Malaysia); Herve Lawin (PI), Arsene Kpangon, Karl Kpossou, Gildas Agodokpessi, Paul Ayelo, Benjamin Fayomi (Unit of Teaching and Research in Occupational and Environmental Health, University of Abomey Calavi, Cotonou, Benin).

Footnotes

Supported by Wellcome Trust grant 085790/Z/08/Z for the BOLD (Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease) Study. The initial BOLD program was funded in part by unrestricted educational grants to the Operations Center in Portland, Oregon from Altana, Aventis, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, and the University of Kentucky (Lexington, KY). Additional local support for BOLD sites was provided by: Boehringer Ingelheim China (Guangzhou, China); the Turkish Thoracic Society, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer (Adana, Turkey); Altana, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharpe and Dohme, Novartis, Salzburger Gebietskrankenkasse, and the Salzburg local government (Salzburg, Austria); Research for International Tobacco Control, the International Development Research Centre, the South African Medical Research Council, the South African Thoracic Society, a GlaxoSmithKline Pulmonary Research Fellowship, and the University of Cape Town Lung Institute (Cape Town, South Africa); Landspítali University Hospital Scientific Fund, GlaxoSmithKline Iceland, and AstraZeneca Iceland (Reykjavik, Iceland); GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals, Polpharma, Ivax Pharma Poland, AstraZeneca Pharma Poland, ZF Altana Pharma, Pliva Kraków, Adamed, Novartis Poland, Linde Gaz Polska, Lek Polska, Tarchomińskie Zakłady Farmaceutyczne Polfa, Starostwo Proszowice, Skanska, Zasada, Agencja Mienia Wojskowego w Krakowie, Telekomunikacja Polska, Biernacki, Biogran, Amplus Bucki, Skrzydlewski, Sotwin, and Agroplon (Krakow, Poland); Boehringer Ingelheim and Pfizer Germany (Hannover, Germany); the Norwegian Ministry of Health’s Foundation for Clinical Research and Haukeland University Hospital’s Medical Research Foundation for Thoracic Medicine (Bergen, Norway); AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline (Vancouver, BC, Canada); Marty Driesler Cancer Project (Lexington, KY); Altana and Boehringer Ingelheim (Philippines), GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Philippine College of Chest Physicians, Philippine College of Physicians, and United Laboratories Philippines (Manila, the Philippines); Air Liquide Healthcare P/L, AstraZeneca P/L, Boehringer Ingelheim P/L, GlaxoSmithKline Australia P/L, and Pfizer Australia P/L (Sydney, NSW, Australia); the Department of Health Policy Research Program and Clement Clarke International (London, UK); Boehringer Ingelheim and Pfizer (Lisbon, Portugal); the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation, the Swedish Association against Heart and Lung Diseases, and GlaxoSmithKline (Uppsala, Sweden); GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, and Eesti Teadusfond (Estonian Science Foundation) (Tartu, Estonia); AstraZeneca and CIRO HORN (Maastricht, the Netherlands); Sher-i-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences (Srinagar, J&K, India); the Foundation for Environmental Medicine, Kasturba Hospital, and the Volkart Foundation (Mumbai, India); Boehringer Ingelheim (Sousse, Tunisia); Boehringer Ingelheim (Fes, Morocco); Philippines College of Physicians, Philippines College of Chest Physicians, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Orient Euro Pharma, Otsuka Pharma, and United Laboratories Philippines (Nampicuan and Talugtug, the Philippines); National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, London (Pune, India); the Wellcome Trust and the National Population Commission, Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria (Ile-Ife, Nigeria); the Kyrgyz Thoracic Society (Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan); GlaxoSmithKline (Tirana, Albania); GlaxoSmithKline, the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, and the Malawi Liverpool Wellcome Trust (Blantyre, Malawi); the Saudi Thoracic Society and King Abdullah International Medical Research Center (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia); Salmawit Pharmaceuticals and Medical International Co. Ltd., and the Epidemiological Laboratory (Khartoum, Sudan); Boehringer Ingelheim (Annaba, Algeria); GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceutical Sendirian Berhad (Penang, Malaysia); and the BRAC (Building Resources Across Communities) Health Nutrition and Population Program (Dhaka, Bangladesh).

A complete list of BOLD collaborators may be found before the beginning of the References.

Author Contributions: A.S.B. and P.G.J.B. were engaged in the initial design of the study; A.F.S.A. and J.P. prepared and analyzed the data; A.F.S.A. and P.G.J.B. drafted the initial manuscript; all authors contributed to its development and approved the final version.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.201701-0205OC on September 12, 2017

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: NanShan Zhong, Shengming Liu, Jiachun Lu, Pixin Ran, Dali Wang, Jingping Zheng, Yumin Zhou, Ali Kocabaş, Attila Hancioglu, Ismail Hanta, Sedat Kuleci, Ahmet Sinan Turkyilmaz, Sema Umut, Turgay Unalan, Michael Studnicka, Torkil Dawes, Bernd Lamprecht, Lea Schirhofer, Eric Bateman, Anamika Jithoo, Desiree Adams, Edward Barnes, Jasper Freeman, Anton Hayes, Sipho Hlengwa, Christine Johannisen, Mariana Koopman, Innocentia Louw, Ina Ludick, Alta Olckers, Johanna Ryck, Janita Storbeck, Thorarinn Gislason, Bryndis Benedikdtsdottir, Kristin Jörundsdottir, Lovisa Gudmundsdottir, Sigrun Gudmundsdottir, Gunnar Gundmundsson, Ewa Nizankowska-Mogilnicka, Jakub Frey, Rafal Harat, Filip Mejza, Pawel Nastalek, Andrzej Pajak, Wojciech Skucha, Andrzej Szczeklik, Magda Twardowska, Tobias Welte, Isabelle Bodemann, Henning Geldmacher, Alexandra Schweda-Linow, Amund Gulsvik, Tina Endresen, Lene Svendsen, Wan C. Tan, Wen Wang, David M. Mannino, John Cain, Rebecca Copeland, Dana Hazen, Jennifer Methvin, Renato B. Dantes, Lourdes Amarillo, Lakan U. Berratio, Lenora C. Fernandez, Norberto A. Francisco, Gerard S. Garcia, Teresita S. de Guia, Luisito F. Idolor, Sullian S. Naval, Thessa Reyes, Camilo C. Roa, Jr., Ma. Flordeliza Sanchez, Leander P. Simpao, Christine Jenkins, Guy Marks, Tessa Bird, Paola Espinel, Kate Hardaker, Brett Toelle, Peter GJ Burney, Caron Amor, James Potts, Michael Tumilty, Fiona McLean, E. F. M. Wouters, G. J. Wesseling, Cristina Bárbara, Fátima Rodrigues, Hermínia Dias, João Cardoso, João Almeida, Maria João Matos, Paula Simão, Moutinho Santos, Reis Ferreira, Christer Janson, Inga Sif Olafsdottir, Katarina Nisser, Ulrike Spetz-Nyström, Gunilla Hägg, Gun-Marie Lund, Rain Jõgi, Hendrik Laja, Katrin Ulst, Vappu Zobel, Toomas-Julius Lill, Parvaiz A Koul, Sajjad Malik, Nissar A Hakim, Umar Hafiz Khan, Rohini Chowgule, Vasant Shetye, Jonelle Raphael, Rosel Almeda, Mahesh Tawde, Rafiq Tadvi, Sunil Katkar, Milind Kadam, Rupesh Dhanawade, Umesh Ghurup, Imed Harrabi, Myriam Denguezli, Zouhair Tabka, Hager Daldoul, Zaki Boukheroufa, Firas Chouikha, Wahbi Belhaj Khalifa, Luisito F. Idolor, Teresita S. de Guia, Norberto A. Francisco, Camilo C. Roa, Fernando G. Ayuyao, Cecil Z. Tady, Daniel T. Tan, Sylvia Banal-Yang, Vincent M. Balanag, Jr., Maria Teresita N. Reyes, Renato. B. Dantes, Sanjay Juvekar, Siddhi Hirve, Somnath Sambhudas, Bharat Chaidhary, Meera Tambe, Savita Pingale, Arati Umap, Archana Umap, Nitin Shelar, Sampada Devchakke, Sharda Chaudhary, Suvarna Bondre, Savita Walke, Ashleshsa Gawhane, Anil Sapkal, Rupali Argade, Vijay Gaikwad, Sundeep Salvi, Bill Brashier, Jyoti Londhe, Sapna Madas, Mohamed C Benjelloun, Chakib Nejjari, Mohamed Elbiaze, Karima El Rhazi, Daniel Obaseki, Gregory Erhabor, Olayemi Awopeju, Olufemi Adewole, M. Al Ghobain, H. Alorainy, E. El-Hamad, M. Al Hajjaj, H. Ayan, D. Rowena, F. Rofel, E. Elizabeth, I. Imelda, H. Safia, Lyla, Talant M. Sooronbaev, Bermet M. Estebesova, Meerim Akmatalieva, Saadat Usenbaeva, Jypara Kydyrova, Eliza Bostonova, Ulan Sheraliev, Nuridin Marajapov, Nurgul Toktogulova, Berik Emilov, Toktogul Azilova, Gulnara Beishekeeva, Nasyikat Dononbaeva, AijamalTabyshova, Kevin Mortimer, Wezzie Nyapigoti, Ernest Mwangoka, Mayamiko Kambwili, Martha Chipeta, Gloria Banda, Suzgo Mkandawire, Justice Banda, Asma Elsony, Hana A. Elsadig, Nada Bakery Osman, Bandar Salah Noory, Monjda Awad Mohamed, Hasab Alrasoul Akasha Ahmed Osman, Namarig Moham ed Elhassan, Abdel Mu‘is El Zain, Marwa Mohamed Mohamaden, Suhaiba Khalifa, Mahmoud Elhadi, Mohand Hassan, Dalia Abdelmonam, Hasan Hafizi, Anila Aliko, Donika Bardhi, Holta Tafa, Natasha Thanasi, Arian Mezini, Alma Teferici, Dafina Todri, Jolanda Nikolla, Rezarta Kazasi, Hamid Hacene Cherkaski, Amira Bengrait, Tabarek Haddad, Ibtissem Zgaoula, Maamar Ghit, Abdelhamid Roubhia, Soumaya Boudra, Feryal Atoui, Randa Yakoubi, Rachid Benali, Abdelghani Bencheikh, Nadia Ait-Khaled, Akramul Islam, Syed Masud Ahmed, Shayla Islam, Qazi Shafayetul Islam, Mesbah-Ul-Haque, Tridib Roy Chowdhury, Sukantha Kumar Chatterjee, Dulal Mia, Shyamal Chandra Das, Mizanur Rahman, Nazrul Islam, Shahaz Uddin, Nurul Islam, Luiza Khatun, Monira Parvin, Abdul Awal Khan, Maidul Islam, Li-Cher Loh, Abdul Rashid, Siti Sholehah, Herve Lawin, Arsene Kpangon, Karl Kpossou, Gildas Agodokpessi, Paul Ayelo, and Benjamin Fayomi

References

- 1.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vestbo J, Hurd SS, Agustí AG, Jones PW, Vogelmeier C, Anzueto A, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: GOLD executive summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187:347–365. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0596PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Marco R, Accordini S, Marcon A, Cerveri I, Antó JM, Gislason T, et al. European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) Risk factors for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in a European cohort of young adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:891–897. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201007-1125OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamprecht B, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, Gudmundsson G, Welte T, Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, et al. BOLD Collaborative Research Group. COPD in never smokers: results from the population-based Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease study. Chest. 2011;139:752–763. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salvi SS, Barnes PJ. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in non-smokers. Lancet. 2009;374:733–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61303-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisner MD, Anthonisen N, Coultas D, Kuenzli N, Perez-Padilla R, Postma D, et al. Committee on Nonsmoking COPD, Environmental and Occupational Health Assembly. An official American Thoracic Society public policy statement: novel risk factors and the global burden of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:693–718. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200811-1757ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurmi OP, Semple S, Simkhada P, Smith WC, Ayres JG. COPD and chronic bronchitis risk of indoor air pollution from solid fuel: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2010;65:221–228. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.124644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu G, Zhou Y, Tian J, Yao W, Li J, Li B, et al. Risk of COPD from exposure to biomass smoke: a metaanalysis. Chest. 2010;138:20–31. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Po JY, FitzGerald JM, Carlsten C. Respiratory disease associated with solid biomass fuel exposure in rural women and children: systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2011;66:232–239. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.147884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith KR, Bruce N, Balakrishnan K, Adair-Rohani H, Balmes J, Chafe Z, et al. Millions dead: how do we know and what does it mean? Methods used in the comparative risk assessment of household air pollution. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:185–206. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith M, Li L, Augustyn M, Kurmi O, Chen J, Collins R, et al. China Kadoorie Biobank collaborative group. Prevalence and correlates of airflow obstruction in ∼317,000 never-smokers in China. Eur Respir J. 2014;44:66–77. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00152413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaganath D, Miranda JJ, Gilman RH, Wise RA, Diette GB, Miele CH, et al. CRONICAS Cohort Study Group. Prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and variation in risk factors across four geographically diverse resource-limited settings in Peru. Respir Res. 2015;16:40. doi: 10.1186/s12931-015-0198-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan WC, Sin DD, Bourbeau J, Hernandez P, Chapman KR, Cowie R, et al. CanCOLD Collaborative Research Group. Characteristics of COPD in never-smokers and ever-smokers in the general population: results from the CanCOLD study. Thorax. 2015;70:822–829. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooper R, Burney P, Vollmer WM, McBurnie MA, Gislason T, Tan WC, et al. Risk factors for COPD spirometrically defined from the lower limit of normal in the BOLD project. Eur Respir J. 2012;39:1343–1353. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00002711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Romieu I, Riojas-Rodríguez H, Marrón-Mares AT, Schilmann A, Perez-Padilla R, Masera O. Improved biomass stove intervention in rural Mexico: impact on the respiratory health of women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:649–656. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1556OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinzerling AP, Guarnieri MJ, Mann JK, Diaz JV, Thompson LM, Diaz A, et al. Lung function in woodsmoke-exposed Guatemalan children following a chimney stove intervention. Thorax. 2016;71:421–428. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buist AS, Vollmer WM, Sullivan SD, Weiss KB, Lee TA, Menezes AM, et al. The Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease Initiative (BOLD): rationale and design. COPD. 2005;2:277–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miller MR, Crapo R, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. ATS/ERS Task Force. General considerations for lung function testing. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:153–161. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swanney MP, Ruppel G, Enright PL, Pedersen OF, Crapo RO, Miller MR, et al. Using the lower limit of normal for the FEV1/FVC ratio reduces the misclassification of airway obstruction. Thorax. 2008;63:1046–1051. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.098483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:179–187. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levy P, Lemeshow S. Sampling of populations: methods and applications. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21:1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, Baur X, Hall GL, Culver BH, et al. ERS Global Lung Function Initiative. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3-95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1324–1343. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurmi OP, Devereux GS, Smith WC, Semple S, Steiner MF, Simkhada P, et al. Reduced lung function due to biomass smoke exposure in young adults in rural Nepal. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:25–30. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00220511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pope D, Diaz E, Smith-Sivertsen T, Lie RT, Bakke P, Balmes JR, et al. Exposure to household air pollution from wood combustion and association with respiratory symptoms and lung function in nonsmoking women: results from the RESPIRE trial, Guatemala. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123:285–292. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guarnieri M, Diaz E, Pope D, Eisen EA, Mann J, Smith KR, et al. Lung function in rural Guatemalan women before and after a chimney stove intervention to reduce wood smoke exposure: results from the randomized exposure study of pollution indoors and respiratory effects and chronic respiratory effects of early childhood exposure to respirable particulate matter study. Chest. 2015;148:1184–1192. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou YM, Zou YM, Li XC, Chen SY, Zhao ZX, He F, et al. Lung function and incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease after improved cooking fuels and kitchen ventilation: a 9-year prospective cohort study. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Peto R, Speizer FE, Cochrane AL, Moore F, Fletcher CM, Tinker CM, et al. The relevance in adults of air-flow obstruction, but not of mucus hypersecretion, to mortality from chronic lung disease: results from 20 years of prospective observation. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983;128:491–500. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1983.128.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meek PM, Petersen H, Washko GR, Diaz AA, Klm V, Sood A, et al. Chronic bronchitis is associated with worse symptoms and quality of life than chronic airflow obstruction. Chest. 2015;148:408–416. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gordon SB, Bruce NG, Grigg J, Hibberd PL, Kurmi OP, Lam KB, et al. Respiratory risks from household air pollution in low and middle income countries. Lancet Respir Med. 2014;2:823–860. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70168-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hooper R, Burney P. Cross-sectional relation of ethnicity to ventilatory function in a west London population. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:400–405. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]