Abstract

Objective:

Although patterns of marijuana use are positively associated with intimate partner aggression, there is little evidence that episodes of marijuana use contribute to the occurrence of episodes of relationship conflict and aggression. The present ecological momentary assessment study considered the temporal relationship between marijuana use episodes and the occurrence of conflict, verbal aggression, and physical aggression between intimate partners in the next 2 hours.

Method:

A sample of 183 cohabiting marijuana-using couples (ages 18–30) were recruited from the community. For 30 consecutive days, each partner independently reported episodes of marijuana use and partner conflict, including verbal and physical aggression perpetration and victimization within conflicts. Temporal associations between each partner’s marijuana use and subsequent conflict and aggression were examined using the Actor–Partner Interdependence Model. Analyses accounted for between-person effects of marijuana use frequency and total conflicts.

Results:

We observed temporal effects of actor (but not partner) marijuana use on men’s and women’s reports of conflict and verbal aggression perpetration and victimization within 2 hours of use. Marijuana use episodes did not alter the likelihood of physical aggression in the next 2 hours. Partner concordance in marijuana use had no effect on verbal or physical aggression or victimization. The positive temporal effects of marijuana on conflict and verbal aggression remained significant after accounting for the effect of drinking episodes.

Conclusions:

Within generally concordant, marijuana-using young couples, marijuana use episodes contribute to the occurrence of relationship conflict and verbal aggression.

Survey research reveals positive global associations between marijuana use patterns and psychological and physical intimate partner aggression (IPA) in adult household samples (Cunradi et al., 2015; Smith et al., 2012; for reviews, see Moore et al., 2008; Moore & Stuart, 2005; Testa & Brown, 2015). Positive associations may reflect pharmacological effects of marijuana on aggression (see Moore & Stuart, 2005); however, survey studies cannot distinguish acute, temporal effects from between-person effects, whereby marijuana use is a marker of the type of person involved in aggressive relationships. The present dyadic ecological momentary assessment (EMA) study was designed to examine whether episodes of marijuana use within couples increase the likelihood of partner conflict and of perpetrating and experiencing partner aggression within 2 hours of use. We considered psychological aggression involving verbal acts (yelling, insulting, making threats) as well as physical acts of aggression (hitting, kicking, throwing objects) displayed during conflicts.

Acute effects of marijuana

A positive association between acute marijuana and IPA seems paradoxical given that marijuana’s acute effects include relaxation and positive affect (Metrik et al., 2011) as well as reduced aggression in the laboratory (Taylor et al., 1976). However, marijuana’s acute effects are variable (Green et al., 2003) and may include increased anxiety, arousal, heart rate, confusion, and perceptual distortion (Hunault et al., 2014; Karila et al., 2014; Mason et al., 2008; Metrik et al., 2011). Marijuana users reported more hostile behaviors and greater perceptions of hostility in others on days of marijuana use compared with days of no use (Ansell et al., 2015). In the context of a disagreement, elevated heart rate and arousal associated with marijuana use may be labeled as anger (Zillmann & Bryant, 1974), increasing the likelihood of conflict escalation and aggression. Cognitive impairment resulting from marijuana may inhibit conflict resolution. These acute psychopharmacological effects may contribute to conflict and aggression (Testa & Brown, 2015).

A few daily report studies have considered the temporal effects of marijuana on IPA, yielding mixed results. Acute marijuana use increased women’s likelihood of perpetrating psychological aggression when angry affect was high (Shorey et al., 2014b) and increased women’s risk of experiencing psychological aggression from their dating partner, a victimization effect (Shorey et al., 2016). However, in other studies, marijuana did not increase the likelihood of IPA perpetration later that day, although drinking episodes did (Moore et al., 2011; Shorey et al., 2014a). Although these studies limited analyses to days of face-to-face contact between participant and partner, all involved individual college students in dating relationships. Relationships may be stronger among married or cohabiting couples (Moore et al., 2008) who spend more time together and have fewer options to end the relationship or disengage from conflict. Moreover, none of these studies focused specifically on marijuana-using couples or accounted for between-person differences between users and non-users.

Marijuana effects within intimate relationships

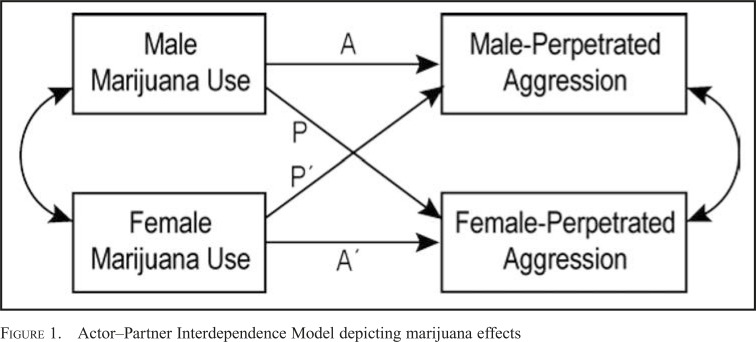

Although IPA occurs within dyads, most studies examining the temporal effects of marijuana on IPA have relied on individual reports. Marijuana not only may lead the user to perpetrate aggression but also may result in aggression by the user’s partner (i.e., a victimization effect). The Actor–Partner Interdependence Model (APIM; Kashy & Snyder, 1995; Kenny et al., 2006) served as a framework for considering these interdependent, dyadic reports (Figure 1). That is, we considered the effects of each person’s own marijuana use on his or her perpetration (a and a′ or Actor paths) as well as the effects of each person’s use on partner’s aggression (p and p′ paths). A recent study using the APIM found independent effects of actor and partner alcohol use on both perpetration and victimization over 56 days of daily reports in a community sample of regular drinkers (Testa & Derrick, 2014).

Figure 1.

Actor–Partner Interdependence Model depicting marijuana effects

Concordance between partners’ acute marijuana use may also be important. Concordant substance use involves shared socialization and activities, resulting in positive dyadic outcomes (Homish & Leonard, 2005; Levitt et al., 2014). In contrast, discrepant partner substance use, relative to concordant or no use, predicted alcohol-related arguments (Leadley et al., 2000) and decreased marital satisfaction over time (Homish & Leonard, 2007).

Present study

We considered whether each partner’s acute marijuana use increased the likelihood of psychological and physical aggression within the next 2 hours in a sample of community couples that included at least one frequent marijuana user. Given rapidly increasing acceptance, use, and legalization of marijuana in the United States (Hasin et al., 2015), it is important to consider the acute effects of marijuana on IPA. To our knowledge, no study has considered the temporal effects of naturally occurring marijuana use episodes on IPA within marijuana-using couples.

Each partner reported independently for 30 days on marijuana and partner conflict episodes, including psychological and physical aggression within conflicts. We hypothesized positive temporal effects of marijuana use on conflict and IPA based on (a) studies showing acute effects of cannabis on hostility (e.g., Ansell et al., 2015) and (b) positive global associations between marijuana use frequency and IPA (Testa & Brown, 2015). The APIM permitted examination of actor and partner marijuana effects. We also considered whether there was a unique Actor × Partner Marijuana Use interaction, that is, whether concordance of partners’ use influenced the odds of IPA beyond the independent effects of each partner’s use.

Episodes of marijuana use may include use of alcohol (e.g., Terry-McElrath et al., 2013), which increases the odds of subsequent IPA (Moore et al., 2011; Testa & Derrick, 2014). Epstein-Ngo et al. (2013) found that the positive effect of marijuana use on dating aggression became nonsignificant after accounting for drinking episodes. Thus, a secondary goal of the study was to determine whether the temporal effects of marijuana on IPA were independent of any effects of acute alcohol consumption.

Method

Participants and recruitment

Participants included 183 married or cohabiting heterosexual community couples in which at least one partner used marijuana at least twice weekly. Most (146/183, 79.8%) responded to Facebook ads seeking couples who use marijuana. Clicking the ad allowed respondents to complete a brief online screener (assessing age, relationship status, and marijuana use) and provide contact information. Others responded to print ads in free arts newspapers (22 couples) or were referred by previous participants (15 couples). All couples were screened for eligibility by telephone. If the first partner met all eligibility criteria, the second partner was also screened independently. To be eligible, both partners had to be between 18 and 30 years old and cohabiting for at least 6 months or married. At least one partner had to use marijuana at least twice weekly with no intention of quitting or seeking treatment. Pregnant women were excluded. Because psychopathology or stimulant use may increase violence, couples were excluded if either reported psychiatric treatment or use of cocaine or stimulants. For safety reasons, couples were excluded if either partner reported IPA that caused fear for one’s life or required medical care; they were provided referral information. Of 558 couples screened by telephone, 305 met all eligibility criteria and 194 began the 30-day EMA study. We excluded eight same-sex couples in order to analyze the data as distinguishable dyads (Kashy & Donnellan, 2012; Kenny et al., 2006). We dropped one couple because of concerns about data veracity, and two couples withdrew from the study almost immediately, yielding 183 couples for analysis.

Most participants self-identified as European American (78.1%), African American (9.3%), or mixed race (6.6%). Men averaged 25.16 (SD = 3.07) and women 24.06 (SD = 3.09) years of age. Most had completed at least some college (70.5% of men, 79.3% of women, 24.0% currently enrolled) and were employed full- or part-time (84.2% of men and 81.4% of women). Median personal income was $15,000–$24,000 for men and $10,000–$14,999 for women. Most couples were cohabiting (84.2%) rather than married (15.8%), with an average length of cohabitation (or marriage) of 2.50 years (range: 0.17–10.25, SD = 2.19). At baseline, most participants (306/366, 83.6%) used marijuana at least twice weekly, and most couples (127/183, 69.4%) consisted of partners who each used marijuana at least twice weekly.

Procedures

Eligible couples completed an in-person orientation. Partners were escorted to private interview rooms for informed consent procedures and completion of baseline questionnaires. Couples were reunited for instruction on how to make independent, confidential reports on a secure web-based portal via smartphone. Participants could use their own phone, but most borrowed a study-provided phone (281/366, 76.8%). Couples were instructed to initiate event-triggered marijuana reports (up to four each day) every time they were about to use marijuana and again after finishing. Similarly, they were to initiate conflict reports whenever they perceived a conflict or felt angry, irritated, or annoyed by the partner even if no argument occurred. Conflict reports were based on subjective perceptions, independent of whether the partner perceived a conflict. In both after-marijuana and conflict reports, the first question assessed the time of occurrence, allowing us to determine temporal ordering of events. Verbal and physical aggression were assessed within each conflict (described below).

In addition to event-triggered reports, which could be made at any time, participants completed daily morning reports. These allowed make-up reporting of marijuana and conflict episodes that occurred the previous day but were not reported in an event-triggered report and permitted reporting of previous day drinking episodes. Participants received texts at 7:00 a.m. and 12:00 noon each day reminding them to complete the report by 3:00 p.m. (when the morning report portal closed for the day). Whenever possible, staff contacted participants who failed to report by 3 p.m. to address any reporting problems and complete the daily report by telephone. Participants were sent weekly texts thanking them for participation and reminding them of monetary bonuses they had earned ($1 per daily report, $10 weekly bonus for completing at least 6/7 morning reports, $30 for completing 4 weeks of reports, maximum of $100). Of 10,980 possible daily reports (30 days × 183 couples), men reported on 5,133/5,490 days (93.5%, M = 28.05 days, SD = 4.36) and women on 5,253/5,490 days (95.7%, M = 28.70 days, SD = 3.09). Of these reports, 9,313/10,386 (89.7%) were made on time.

Measures

Marijuana episodes were reported in real time using a time-stamped, event-triggered report (n = 1,560) or on the next day’s morning report (n = 6,075). For each episode, participants reported time use began, permitting temporal ordering of marijuana use and IPA episodes. Follow-up questions included number of joints, perceived high, whether partner was present, and whether the episode included alcohol use. There were modest differences between on-time and next day reports, such as reporting more joints in morning reports (2.36 vs. 1.98, p < .001) but feeling more high in event reports (3.64 vs. 3.88, p < .001). However, to provide the most comprehensive test of the temporal effects of marijuana, we combined and used all event reports.

Similarly, conflicts were reported using event-triggered reports (n = 111) or on the next daily report (n = 1,267). For each conflict reported, participants were asked time of occurrence and whether it included six behaviors derived from the Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS-2, Straus et al., 1996): yelled; tried to work out a solution; threw things, kicked, or hit something; made threats; pushed, grabbed, or hit partner; and insulted or called names. Each was assessed with reference to behaviors toward partner (perpetration) and received from partner (victimization). If a conflict included a positive response to yelled, made threats, or insulted/name-called, it was categorized as an episode of verbal aggression. Positive responses to pushed/grabbed/hit partner or threw/kicked/hit something were categorized as physical aggression. Although the latter does not require physical contact with partner, such acts within a conflict are perceived as violent by community couples (Testa et al., 2017). Male and female reports of conflict and verbal and physical aggression perpetration and victimization constituted the primary dependent measures. There were no differences between event-triggered and morning reports in the proportion of conflicts that included verbal or physical aggression; hence, these were combined.

Analytic strategy

Analyses were performed using multivariate multilevel modeling with three levels. Outcome variables were male and female reports of conflict, verbal aggression, and physical aggression. At Level 1 (the hourly level), we included each partner’s marijuana use in the previous 2 hours. To create the temporal version of the predictors, we divided each day into 24 one-hour segments. Then we created lags for the predictor variables for the previous 2 hours and collapsed across those lagged variables to create a “moving window” that included any instances of marijuana use in the previous 2 hours. The 2-hour window was chosen based on pharmacological studies suggesting that tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) effects peak 30 minutes after use and taper off after 2–3 hours (Grotenhermen, 2003). Level-1 variables were dummy-coded and uncentered. We created an interaction term consisting of Male Marijuana Use × Female Marijuana Use in the 2-hour window. We also included time of day (1 = 5 p.m.–midnight, 0 = all other hours) to control for temporal effects. At Level 2 (the daily level), we included day of the study (1–30), uncentered, to account for the tendency for daily reports to decline over time (e.g., Testa et al., 2015). At Level 3 (the couple level), we controlled for each partner’s total days of marijuana use and conflict. Including these variables allowed us to distinguish within-person effects of marijuana from between-person effects and to account for between-person differences in the amount of relationship conflict. Level-3 variables were grand mean centered (Enders & Tofighi, 2007). Specifically, our multivariate three-level analyses were conducted in Mplus Version 7.4, using ESTIMATOR = BAYES and setting the BITERATIONS option at 100,000 (Muthén & Muthén, 2015; Muthén et al., 2016). The Bayes median point estimates, two-tailed p values (Gelman et al., 2014), and Bayesian 95% credibility intervals were reported.

Results

Event reports

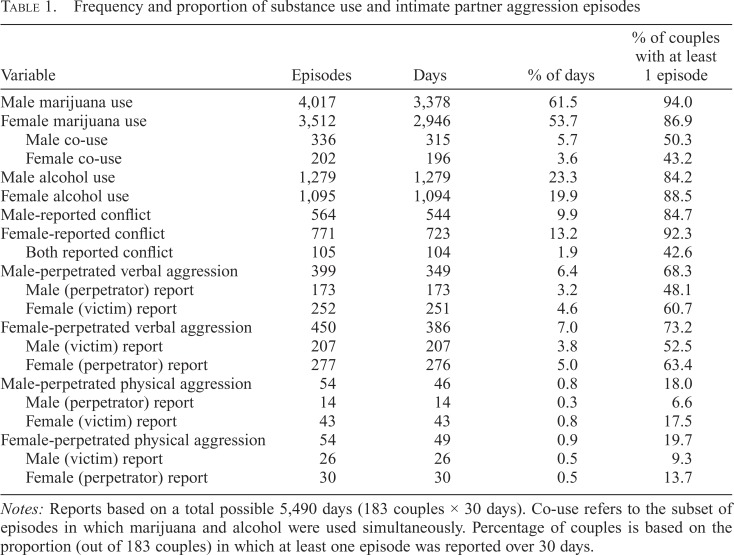

Table 1 displays the frequency of marijuana and alcohol episodes and the percentage of days and couples in which each event was reported over 30 days. There were 7,529 episodes of marijuana reported, a mean of 18.46 marijuana use days for men (range: 0–30, SD = 9.45) and 16.10 marijuana use days for women (range: 0–30, SD = 10.20). Men reported two or more episodes on 639/3,378 marijuana days (18.9%) and women on 566/2,946 marijuana days (19.2%). Most episodes involved marijuana only (3,681/4,107 or 89.6% for men, 3,310/3,512 or 94.2% for women), but some included co-use of marijuana and alcohol (336 co-use episodes for men, 202 for women). The participant reported that the partner was present and using marijuana in the majority of episodes (3,019/4,870, 62.0%); more rarely, partner was present but not using (564/4,870, 11.6%). There were 2,374 episodes of alcohol use (only) reported on the morning report (1,279 by men, 1,095 by women), and most occurred when the partner was present and drinking (1,404/2,194, 64.0%). Across all drinking episodes (alone or co-use), men consumed an average of 3.97 drinks (SD = 2.68) and women 3.07 drinks (SD = 2.25).

Table 1.

Frequency and proportion of substance use and intimate partner aggression episodes

| Variable | Episodes | Days | % of days | % of couples with at least 1 episode |

| Male marijuana use | 4,017 | 3,378 | 61.5 | 94.0 |

| Female marijuana use | 3,512 | 2,946 | 53.7 | 86.9 |

| Male co-use | 336 | 315 | 5.7 | 50.3 |

| Female co-use | 202 | 196 | 3.6 | 43.2 |

| Male alcohol use | 1,279 | 1,279 | 23.3 | 84.2 |

| Female alcohol use | 1,095 | 1,094 | 19.9 | 88.5 |

| Male-reported conflict | 564 | 544 | 9.9 | 84.7 |

| Female-reported conflict | 771 | 723 | 13.2 | 92.3 |

| Both reported conflict | 105 | 104 | 1.9 | 42.6 |

| Male-perpetrated verbal aggression | 399 | 349 | 6.4 | 68.3 |

| Male (perpetrator) report | 173 | 173 | 3.2 | 48.1 |

| Female (victim) report | 252 | 251 | 4.6 | 60.7 |

| Female-perpetrated verbal aggression | 450 | 386 | 7.0 | 73.2 |

| Male (victim) report | 207 | 207 | 3.8 | 52.5 |

| Female (perpetrator) report | 277 | 276 | 5.0 | 63.4 |

| Male-perpetrated physical aggression | 54 | 46 | 0.8 | 18.0 |

| Male (perpetrator) report | 14 | 14 | 0.3 | 6.6 |

| Female (victim) report | 43 | 43 | 0.8 | 17.5 |

| Female-perpetrated physical aggression | 54 | 49 | 0.9 | 19.7 |

| Male (victim) report | 26 | 26 | 0.5 | 9.3 |

| Female (perpetrator) report | 30 | 30 | 0.5 | 13.7 |

Notes: Reports based on a total possible 5,490 days (183 couples × 30 days). Co-use refers to the subset of episodes in which marijuana and alcohol were used simultaneously. Percentage of couples is based on the proportion (out of 183 couples) in which at least one episode was reported over 30 days.

Table 1 also provides the number of episodes of conflict and IPA within conflicts reported over 30 days. Conflicts were more likely to be reported after 5 p.m. than before 5 p.m., χ2(1, n = 10,370) = 118.716, p < .001. Women reported significantly more conflicts (771, M = 3.95, range: 0–15, SD = 3.10) than men (564, M = 2.97, range: 0–15, SD = 2.63), t(10,978) = -18.08, p < .001. Within each independently reported conflict, respondents were asked about the occurrence of verbal and physical perpetration and victimization. Consistent with prior research (Caetano et al., 2002), women reported more episodes of IPA perpetration and victimization than men (all ps < .01).

Conflict reports were made independently and, as expected (Derrick et al., 2014), agreement between partners that a conflict occurred was modest. Both partners reported a conflict on 104 days; most conflicts were reported by either the woman (619 days) or the man (440 days). Because partner agreement regarding the occurrence of conflict and IPA on a given day was low, male and female reports were examined separately. However, because it is common to pool male and female partner reports to provide a better estimate of the occurrence of IPA within couples (Caetano et al., 2002), Table 1 displays the prevalence of male- and female-perpetrated aggression based on combined male and female reports. In the majority of couples, at least one episode of male-perpetrated (68.3%) and female-perpetrated verbal aggression (73.2%) was reported by either partner over the 30 days. A substantial proportion of couples also reported at least one episode of physical aggression (18.0% male-perpetrated, 19.7% female-perpetrated) within 30 days.

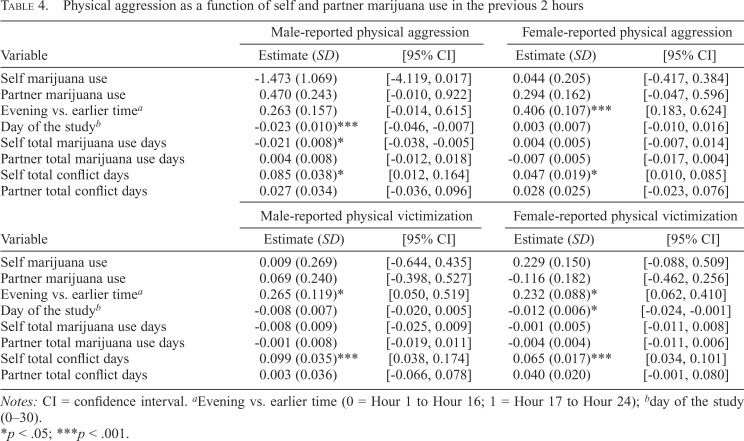

Temporal effects of marijuana use episodes on conflict, verbal and physical aggression

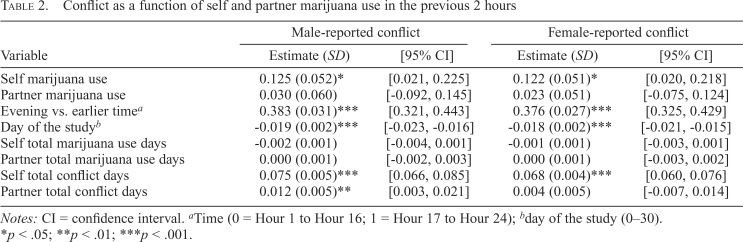

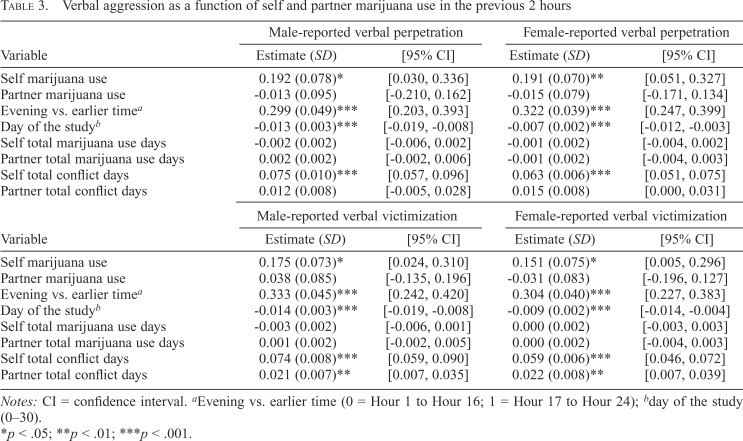

First, we considered whether actor and partner marijuana use increased the likelihood of reporting conflict in the next 2 hours. As shown in Table 2, actor marijuana use increased the odds of reporting a conflict within the next 2 hours for men and women; partner marijuana use did not. Next, we considered the effects of actor and partner marijuana use on male and female verbal aggression in the next 2 hours. As shown in Table 3, actor marijuana use significantly increased the likelihood of reporting verbal aggression perpetration and victimization in the next 2 hours for men and women. Partner effects were not significant. A similar analysis using physical aggression as the outcome revealed no significant temporal effects of actor or partner marijuana on physical aggression (Table 4).

Table 2.

Conflict as a function of self and partner marijuana use in the previous 2 hours

| Male-reported conflict |

Female-reported verbal conflict |

|||

| Variable | Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] | Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] |

| Self marijuana use | 0.125 (0.052)* | [0.021, 0.225] | 0.122 (0.051)* | [0.020, 0.218] |

| Partner marijuana use | 0.030 (0.060) | [-0.092, 0.145] | 0.023 (0.051) | [-0.075, 0.124] |

| Evening vs. earlier timea | 0.383 (0.031)*** | [0.321, 0.443] | 0.376 (0.027)*** | [0.325, 0.429] |

| Day of the studyb | -0.019 (0.002)*** | [-0.023, -0.016] | -0.018 (0.002)*** | [-0.021, -0.015] |

| Self total marijuana use days | -0.002 (0.001) | [-0.004, 0.001] | -0.001 (0.001) | [-0.003, 0.001] |

| Partner total marijuana use days | 0.000 (0.001) | [-0.002, 0.003] | 0.000 (0.001) | [-0.003, 0.002] |

| Self total conflict days | 0.075 (0.005)*** | [0.066, 0.085] | 0.068 (0.004)*** | [0.060, 0.076] |

| Partner total conflict days | 0.012 (0.005)** | [0.003, 0.021] | 0.004 (0.005) | [-0.007, 0.014] |

Notes: CI = confidence interval.

Time (0 = Hour 1 to Hour 16; 1 = Hour 17 to Hour 24);

day of the study (0–30).

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Table 3.

Verbal aggression as a function of self and partner marijuana use in the previous 2 hours

| Male-reported verbal perpetration |

Female-reported verbal perpetration |

|||

| Variable | Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] | Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] |

| Self marijuana use | 0.192 (0.078)* | [0.030, 0.336] | 0.191 (0.070)** | [0.051, 0.327] |

| Partner marijuana use | -0.013 (0.095) | [-0.210, 0.162] | -0.015 (0.079) | [-0.171, 0.134] |

| Evening vs. earlier timea | 0.299 (0.049)*** | [0.203, 0.393] | 0.322 (0.039)*** | [0.247, 0.399] |

| Day of the studyb | -0.013 (0.003)*** | [-0.019, -0.008] | -0.007 (0.002)*** | [-0.012, -0.003] |

| Self total marijuana use days | -0.002 (0.002) | [-0.006, 0.002] | -0.001 (0.002) | [-0.004, 0.002] |

| Partner total marijuana use days | 0.002 (0.002) | [-0.002, 0.006] | -0.001 (0.002) | [-0.004, 0.003] |

| Self total conflict days | 0.075 (0.010)*** | [0.057, 0.096] | 0.063 (0.006)*** | [0.051, 0.075] |

| Partner total conflict days | 0.012 (0.008) | [-0.005, 0.028] | 0.015 (0.008) | [0.000, 0.031] |

| Male-reported verbal victimization |

Female-reported verbal victimization |

|||

| Variable | Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] | Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] |

| Self marijuana use | 0.175 (0.073)* | [0.024, 0.310] | 0.151 (0.075)* | [0.005, 0.296] |

| Partner marijuana use | 0.038 (0.085) | [-0.135, 0.196] | -0.031 (0.083) | [-0.196, 0.127] |

| Evening vs. earlier timea | 0.333 (0.045)*** | [0.242, 0.420] | 0.304 (0.040)*** | [0.227, 0.383] |

| Day of the studyb | -0.014 (0.003)*** | [-0.019, -0.008] | -0.009 (0.002)*** | [-0.014, -0.004] |

| Self total marijuana use days | -0.003 (0.002) | [-0.006, 0.001] | 0.000 (0.002) | [-0.003, 0.003] |

| Partner total marijuana use days | 0.001 (0.002) | [-0.002, 0.005] | 0.000 (0.002) | [-0.004, 0.003] |

| Self total conflict days | 0.074 (0.008)*** | [0.059, 0.090] | 0.059 (0.006)*** | [0.046, 0.072] |

| Partner total conflict days | 0.021 (0.007)** | [0.007, 0.035] | 0.022 (0.008)** | [0.007, 0.039] |

Notes: CI = confidence interval.

Evening vs. earlier time (0 = Hour 1 to Hour 16; 1 = Hour 17 to Hour 24);

day of the study (0–30).

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Table 4.

Physical aggression as a function of self and partner marijuana use in the previous 2 hours

| Male-reported physical aggression |

Female-reported physical aggression |

|||

| Variable | Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] | Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] |

| Self marijuana use | -1.473 (1.069) | [-4.119, 0.017] | 0.044 (0.205) | [-0.417, 0.384] |

| Partner marijuana use | 0.470 (0.243) | [-0.010, 0.922] | 0.294 (0.162) | [-0.047, 0.596] |

| Evening vs. earlier timea | 0.263 (0.157) | [-0.014, 0.615] | 0.406 (0.107)*** | [0.183, 0.624] |

| Day of the studyb | -0.023 (0.010)*** | [-0.046, -0.007] | 0.003 (0.007) | [-0.010, 0.016] |

| Self total marijuana use days | -0.021 (0.008)* | [-0.038, -0.005] | 0.004 (0.005) | [-0.007, 0.014] |

| Partner total marijuana use days | 0.004 (0.008) | [-0.012, 0.018] | -0.007 (0.005) | [-0.017, 0.004] |

| Self total conflict days | 0.085 (0.038)* | [0.012, 0.164] | 0.047 (0.019)* | [0.010, 0.085] |

| Partner total conflict days | 0.027 (0.034) | [-0.036, 0.096] | 0.028 (0.025) | [-0.023, 0.076] |

| Male-reported physical victimization |

Female-reported physical victimization |

|||

| Variable | Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] | Estimate (SD) | [95% CI] |

| Self marijuana use | 0.009 (0.269) | [-0.644, 0.435] | 0.229 (0.150) | [-0.088, 0.509] |

| Partner marijuana use | 0.069 (0.240) | [-0.398, 0.527] | -0.116 (0.182) | [-0.462, 0.256] |

| Evening vs. earlier timea | 0.265 (0.119)* | [0.050, 0.519] | 0.232 (0.088)* | [0.062, 0.410] |

| Day of the studyb | -0.008 (0.007) | [-0.020, 0.005] | -0.012 (0.006)* | [-0.024, -0.001] |

| Self total marijuana use days | -0.008 (0.009) | [-0.025, 0.009] | -0.001 (0.005) | [-0.011, 0.008] |

| Partner total marijuana use days | -0.001 (0.008) | [-0.019, 0.011] | -0.004 (0.004) | [-0.011, 0.006] |

| Self total conflict days | 0.099 (0.035)*** | [0.038, 0.174] | 0.065 (0.017)*** | [0.034, 0.101] |

| Partner total conflict days | 0.003 (0.036) | [-0.066, 0.078] | 0.040 (0.020) | [-0.001, 0.080] |

Notes: CI = confidence interval.

Evening vs. earlier time (0 = Hour 1 to Hour 16; 1 = Hour 17 to Hour 24);

day of the study (0–30).

p < .05;

p < .001.

In all models, we accounted for the robust Level 1 effects of time of day (more conflicts occurred after 5 p.m.) and day of the study (conflicts declined over 30 days). We also accounted for the between-person effects of total conflict days; participants who reported more conflicts over 30 days were more likely to report conflict and aggression in a given hour. We considered between-person effects of self and partner total marijuana use days but did not find positive effects on conflict or IPA.

To test whether marijuana use concordance affected conflict, verbal aggression, or physical aggression, we added an interaction term (Male × Female Marijuana Use) to each model. The interaction was not significant in any model and did not alter effects; hence, it is not displayed.

Supplemental analyses: Accounting for the temporal effects of alcohol

Because acute alcohol use increases IPA and may account for marijuana’s apparent effects (Epstein-Ngo et al., 2013), we considered whether the positive temporal effects of marijuana on conflict and verbal aggression were explained by alcohol use. First, we repeated analyses presented in Tables 2 and 3, removing marijuana events in which there was co-occurring alcohol use. Marijuana effects remained unchanged. We then repeated analyses with the addition of alcohol episodes at Level 1 (either alcohol alone or with marijuana) and total number of alcohol use days at Level 3. The positive effects of marijuana on conflict and verbal aggression remained significant after controlling for alcohol episodes. We did not observe any significant effects of alcohol on verbal aggression but found a significant positive actor effect of alcohol on women’s conflict reports and a significant partner effect of alcohol on men’s conflict reports.

Discussion

This study was the most comprehensive examination to date of the temporal effects of naturally occurring marijuana use episodes on intimate partner conflict and aggression. Within a community sample of frequent marijuana-using couples, we found modest but significant increases in the odds of self-reported conflict and verbal aggression perpetration and victimization within 2 hours of using marijuana for men and women. Results replicate and extend similar but more modest effects of marijuana on psychological dating aggression in college students (Shorey et al., 2014b, 2016). The effects of marijuana on conflict may result from heightened irritability or increased vigilance or sensitivity to conflict following one’s own use. However, the association of marijuana use and conflict may also reflect partner proximity, since most marijuana use occurred when the partner was present. It is also possible that daily situational factors (e.g., work stress) influenced both marijuana use and conflict. The present study was not designed to identify the mechanisms that underlie marijuana’s acute effects, but it is important for future research to do so.

Although we used APIM, we found no unique effects of partner marijuana use in any model. Relatedly, we observed no unique effects associated with partner marijuana use concordance; however, concordant use was the norm, potentially limiting our ability to detect effects. Testa and Derrick (2014) also failed to find effects of partner concordance at the event level despite robust independent effects of perpetrator and victim alcohol use. It is possible that among couples in which marijuana use is frequent and typically concordant, discordance at the event level is not a significant source of tension. Rather, the degree of substance use discordance over time (e.g., Homish & Leonard, 2007) may be the more important predictor of relationship quality and partner aggression.

Despite the positive effects of marijuana on conflict and verbal aggression, we observed no significant effects of marijuana on physical aggression perpetration or victimization. Null findings may reflect limited power to detect an effect given that there were few episodes of physical aggression. However, prior research also suggests that marijuana’s effects may be limited to psychological aggression (Shorey et al., 2014b, 2016) or stronger for verbal and psychological as opposed to physical (Moore et al., 2008). Nonetheless, 18.0% of couples experienced male-perpetrated and 19.7% female-perpetrated physical aggression over 30 days. These rates are nearly identical to those observed, using identical measures, in a 56-day study of frequent drinkers (18.6% male-perpetrated, 20.3% female-perpetrated physical aggression; Testa & Derrick, 2014). Although many frequent marijuana users display physical aggression toward their partners, acute marijuana use does not increase the immediate likelihood of its occurrence. It remains for future research to identify acute predictors of IPA episodes in such couples.

Our analyses were deliberately conservative. We accounted for the fact that conflict and IPA were more likely to occur in the evening and that couples who report more conflicts are more likely to report conflict in a given hour. We also considered whether observed marijuana effects might actually reflect effects of alcohol, which is known to increase IPA. Using two different methods to account for the potential effects of alcohol, marijuana effects on conflict and verbal aggression remained significant. Although we found positive effects of women’s drinking episodes on conflict, surprisingly, we failed to observe independent effects of alcohol on verbal aggression. This may reflect the unique nature of this primarily marijuana-using sample of couples.

Limitations

The availability of a large number of near-real-time reports of marijuana use and conflict is a strength of the study. However, despite encouragement to make event-triggered reports, most events were reported the next day. Participant compensation based on daily report completion (not event-triggered reports) resulted in excellent compliance but may have contributed to this reporting pattern. Reports were completed within 24 hours, reducing memory decay; however, it is possible that accurate reporting of the exact time of these episodes—crucial to our temporal analyses—may have been impaired. Because our sample was limited to frequent users who were not seeking to reduce or restrict their use, we were unable to consider the impact of marijuana withdrawal effects (e.g., irritability, anger, violent outbursts; Herrmann et al., 2015), which have been linked to IPA (Smith et al., 2013). Finally, results were derived from a sample of frequent marijuana users recruited from a single community, primarily via Facebook, and may not generalize.

Conclusions and implications

Findings provide some insight into the paradoxical positive relationship between marijuana use and intimate partner aggression (Johnson et al., 2017; Testa & Brown, 2015). Acute marijuana use increases the odds of conflict and partner verbal aggression for men and women. Because verbal aggression contributes to the development of physical aggression over the first years of marriage (Schumacher & Leonard, 2005), it will be important for future research to consider the effects of couple marijuana use on relationship outcomes over time. The negative consequences of discrete episodes of marijuana use may be small, but daily responses may have a significant cumulative impact on relationship functioning trajectories over time (Murray et al., 2009).

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse Grant R01DA033994 (to Maria Testa) and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant T32AA007583.

References

- Ansell E. B., Laws H. B., Roche M. J., Sinha R. Effects of marijuana use on impulsivity and hostility in daily life. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2015;148:136–142. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.029. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.12.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R., Schafer J., Field C., Nelson S. M. Agreements on reports of intimate partner violence among White, Black and Hispanic couples in the United States. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2002;17:1308–1322. doi:10.1177/088626002237858. [Google Scholar]

- Cunradi C. B., Todd M., Mair C. Discrepant patterns of heavy drinking, marijuana use, and smoking and intimate partner violence: Results from the California Community Health Study of Couples. Journal of Drug Education. 2015;45:73–95. doi: 10.1177/0047237915608450. doi:10.1177/0047237915608450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrick J. L., Testa M., Leonard K. E. Daily reports of intimate partner verbal aggression by self and partner: Short-term consequences and implications for measurement. Psychology of Violence. 2014;4:416–431. doi: 10.1037/a0037481. doi:10.1037/a0037481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders C. K., Tofighi D. Centering predictor variables in cross-sectional multilevel models: A new look at an old issue. Psychological Methods. 2007;12:121–138. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.12.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein-Ngo Q. M., Cunningham R. M., Whiteside L. K., Chermack S. T., Booth B. M., Zimmerman M. A., Walton M. A. A daily calendar analysis of substance use and dating violence among high risk urban youth. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;130:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.006. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelman A., Carlin J. B., Stern H. S., Rubin D. B. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2014. Bayesian data analysis (Vol. 2) [Google Scholar]

- Green B., Kavanagh D., Young R. Being stoned: A review of self-reported cannabis effects. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2003;22:453–460. doi: 10.1080/09595230310001613976. doi:10.1080/09595230310001613976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grotenhermen F. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 2003;42:327–360. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200342040-00003. doi:10.2165/00003088-200342040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasin D. S., Saha T. D., Kerridge B. T., Goldstein R. B., Chou S. P., Zhang H., Grant B. F. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States between 2001–2002 and 2012–2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1235–1242. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann E. S., Weerts E. M., Vandrey R. Sex differences in cannabis withdrawal symptoms among treatment-seeking cannabis users. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2015;23:415–421. doi: 10.1037/pha0000053. doi:10.1037/pha0000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish G. G., Leonard K. E. Marital quality and congruent drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:488–496. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.488. doi:10.15288/jsa.2005.66.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homish G. G., Leonard K. E. The drinking partnership and marital satisfaction: The longitudinal influence of discrepant drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:43–51. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.43. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunault C. C., Böcker K. B. E., Stellato R. K., Kenemans J. L., de Vries I., Meulenbelt J. Acute subjective effects after smoking joints containing up to 69 mg !9-tetrahydrocannabinol in recreational users: A randomized, crossover clinical trial. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:4723–4733. doi: 10.1007/s00213-014-3630-2. doi:10.1007/s00213-014-3630-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. M., LaValley M., Schneider K. E., Musci R. J., Pettoruto K., Rothman E. F. Marijuana use and physical dating violence among adolescents and emerging adults: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2017;174:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.01.012. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karila L., Roux P., Rolland B., Benyamina A., Reynaud M., Aubin H.-J., Lançon C. Acute and long-term effects of cannabis use: A review. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2014;20:4112–4118. doi: 10.2174/13816128113199990620. doi:10.2174/13816128113199990620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashy D. A., Donnellan M. B. Conceptual and methodological issues in the analysis of data from dyads and groups. In: Deaux K., Snyder M., editors. The Oxford handbook of personality and social psychology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 209–238. [Google Scholar]

- Kashy D. A., Snyder D. K. Measurement and data analytic issues in couples’ research. Psychological Assessment. 1995;7:338–348. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.338. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny D. A., Kashy D. A., Cook W. L. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. Dyadic data analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Leadley K., Clark C. L., Caetano R. Couples’ drinking patterns, intimate partner violence, and alcohol-related partnership problems. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2000;11:253–263. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(00)00025-0. doi:10.1016/S0899-3289(00)00025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt A., Derrick J. L., Testa M. Relationship-specific alcohol expectancies and gender moderate the effects of relationship drinking contexts on daily relationship functioning. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2014;75:269–278. doi:10.15288/jsad.2014.75.269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason O. J., Morgan C. J. M., Stefanovic A., Curran H. V. The psychotomimetic states inventory (PSI): Measuring psychotic-type experiences from ketamine and cannabis. Schizophrenia Research. 2008;103:138–142. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.02.020. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metrik J., Kahler C. W., McGeary J. E., Monti P. M., Rohsenow D. J. Acute effects of marijuana smoking on negative and positive affect. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2011;25:31–46. doi: 10.1891/0889-8391.25.1.31. doi:10.1891/0889-8391.25.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore T. M., Elkins S. R., McNulty J. K., Kivisto A. J., Handsel V. A. Alcohol use and intimate partner violence perpetration among college students: Assessing the temporal association using electronic diary technology. Psychology of Violence. 2011;1:315–328. doi:10.1037/a0025077. [Google Scholar]

- Moore T. M., Stuart G. L. A review of the literature on marijuana and interpersonal violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2005;10:171–192. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2003.10.002. [Google Scholar]

- Moore T. M., Stuart G. L., Meehan J. C., Rhatigan D. L., Hellmuth J. C., Keen S. M. Drug abuse and aggression between intimate partners: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:247–274. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.003. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray S. L., Holmes J. G., Aloni M., Pinkus R. T., Derrick J. L., Leder S. Commitment insurance: Compensating for the autonomy costs of interdependence in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97:256–278. doi: 10.1037/a0014562. doi:10.1037/a0014562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. O., Muthén L. K. Los Angeles, CA: Authors; 2015. Mplus users’ guide (7th ed.) [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. O., Muthén L. K., Asparouhov T. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2016. Regression and mediation analysis using Mplus. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher J. A., Leonard K. E. Husbands’ and wives’ marital adjustment, verbal aggression, and physical aggression as longitudinal predictors of physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:28–37. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.28. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Moore T. M., McNulty J. K., Stuart G. L. Do alcohol and marijuana increase the risk for female dating violence victimization? A prospective daily diary investigation. Psychology of Violence. 2016;6:509–518. doi: 10.1037/a0039943. doi:10.1037/a0039943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Stuart G. L., McNulty J. K., Moore T. M. Acute alcohol use temporally increases the odds of male perpetrated dating violence: A 90-day diary analysis. Addictive Behaviors. 2014a;39:365–368. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.025. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorey R. C., Stuart G. L., Moore T. M., McNulty J. K. The temporal relationship between alcohol, marijuana, angry affect, and dating violence perpetration: A daily diary study with female college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014b;28:516–523. doi: 10.1037/a0034648. doi:10.1037/a0034648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P. H., Homish G. G., Leonard K. E., Collins R. L. Marijuana withdrawal and aggression among a representative sample of U.S. marijuana users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;132:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.002. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P. H., Homish G. G., Leonard K. E., Cornelius J. R. Intimate partner violence and specific substance use disorders: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:236–245. doi: 10.1037/a0024855. doi:10.1037/a0024855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus M. A., Hamby S. L., Boney-McCoy S., Sugarman D. B. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. doi:10.1177/019251396017003001. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. P., Vardaris R. M., Rawtich A. B., Gammon C. B., Cranston J. W., Lubetkin A. I. The effects of alcohol and delta-9-tetrahydrocannibinol on human physical aggression. Aggressive Behavior. 1976;2:153–161. doi:10.1002/1098-2337(1976)2:2<153::AID-AB2480020206>3.0.CO;2-9. [Google Scholar]

- Terry-McElrath Y. M., O’Malley P. M., Johnston L. D. Simultaneous alcohol and marijuana use among U.S. high school seniors from 1976 to 2011: Trends, reasons, and situations. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;133:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.031. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Brown W. C. Does marijuana use contribute to intimate partner aggression? A brief review and directions for future research. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015;5:6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.002. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Derrick J. L. A daily process examination of the temporal association between alcohol use and verbal and physical aggression in community couples. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:127–138. doi: 10.1037/a0032988. doi:10.1037/a0032988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Parks K. A., Hoffman J. H., Crane C. A., Leonard K. E., Shyhalla K. Do drinking episodes contribute to sexual aggression in college men? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015;76:507–515. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2015.76.507. doi:10.15288/jsad.2015.76.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M., Petrocelli L. T., Crane C. A., Kubiak A., Leonard K. E. A qualitative analysis of physically aggressive conflict episodes among a community sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2017 doi: 10.1177/0886260517715023. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517715023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zillmann D., Bryant J. Effect of residual excitation on the emotional response to provocation and delayed aggressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1974;30:782–791. doi: 10.1037/h0037541. doi:10.1037/h0037541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]