SUMMARY

Background

Mounting evidence suggests that laws and policies prohibiting illegal drug use could have a central role in shaping health outcomes among people who inject drugs (PWID). To date, no systematic review has characterised the influence of laws and legal frameworks prohibiting drug use on HIV prevention and treatment.

Methods

Consistent with PRISMA guidelines, we did a systematic review of peer-reviewed scientific evidence describing the association between criminalisation of drug use and HIV prevention and treatment-related outcomes among PWID. We searched MEDLINE, Embase, SCOPUS, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, CINAHL, Web of Science, and other sources. To be included in our review, a study had to meet the following eligibility criteria: be published in a peer-reviewed journal or presented as a peer-reviewed abstract at a scientific conference; examine, through any study design, the association between an a-priori set of indicators related to the criminalisation of drugs and HIV prevention or treatment among PWID; provide sufficient details on the methods followed to allow critical assessment of quality; be published or presented between Jan 1, 2006, and Dec 31, 2014; and be published in the English language.

Findings

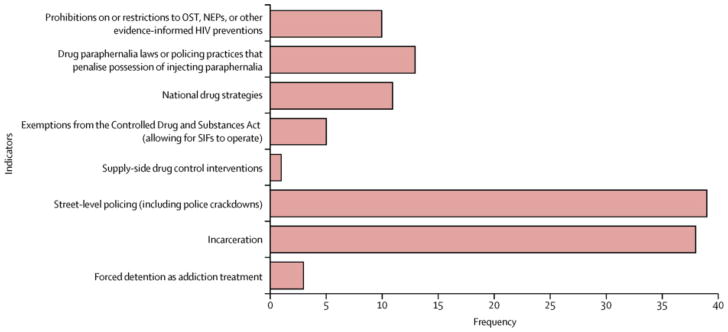

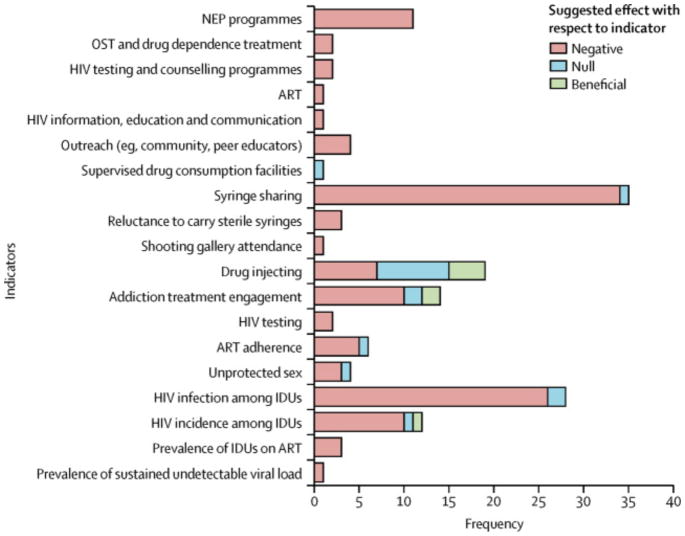

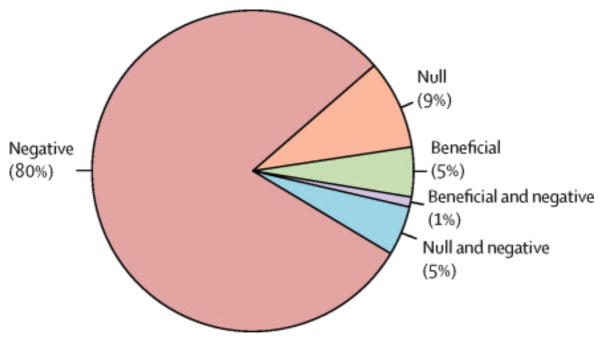

We identified 106 eligible studies comprising 29 longitudinal, 49 cross-sectional, 22 qualitative, two mixed methods, four mathematical modelling studies, and no randomised controlled trials. 120 criminalisation indicators were identified (range 1–3 per study) and 150 HIV indicators were identified (1–5 per study). The most common criminalisation indicators were incarceration (n=38) and street-level policing (n=39), while the most frequent HIV prevention and treatment indicators were syringe sharing (n=35) and prevalence of HIV infection among PWID (n=28). Among the 106 studies included in this review, 85 (80%) suggested that drug criminalisation has a negative effect on HIV prevention and treatment, 10 (9%) suggested no association, five (5%) suggested a beneficial effect, one (1%) suggested both beneficial and negative effects, and five (5%) suggested both null and negative effects.

Interpretation

These data confirm that criminalisation of drug use has a negative effect on HIV prevention and treatment. Our results provide an objective evidence base to support numerous international policy initiatives to reform legal and policy frameworks criminalising drug use.

INTRODUCTION

Worldwide, an estimated 8·4 million to 19·0 million individuals inject psychoactive drugs. 1 The public health concerns associated with the use of injection drugs are numerous and include the spread of infectious diseases, most notably HIV. About 13% of people who inject drugs (PWID) are thought to be living with HIV, which amounts to roughly 1·7 million individuals. 2

UNAIDS has estimated that 30% of new HIV infections outside of the more generalised HIV epidemics of sub-Saharan Africa are attributable to the use of injection drugs. 2 Countries that have been identified as being particularly affected by HIV epidemics among PWID include China, Malaysia, Russia, Ukraine, and Vietnam. 3 These five countries account for roughly half (47%) of all PWID estimated to be living with HIV in low-income and middle-income countries. 4 Although prevalence estimates of HIV among PWID in China, Ukraine, and Vietnam indicate notable improvements from the early 2000s to 2012, 5 HIV epidemics are expanding in some regions of eastern Europe and central Asia, in the Middle East, and in north Africa, and this expansion is attributed in part to the use of injection drugs. 5,6 Indeed, in 2014, 51% of new HIV infections in eastern Europe and central Asia and 28% of those in the Middle East and north Africa were estimated to be among PWID, highlighting their continued relevance as a key population in the global fight against HIV. 7

Since the expansion of highly active antiretroviral therapy (ART) to low-income and middle-income countries in 2000, the course of the HIV pandemic has been substantially altered. 2,8 ART has substantially reduced morbidity and mortality associated with HIV infection and decreased onward transmission risks in people living with HIV. 9,10 Optimal use of ART has led to substantial decreases in new infections in PWID in various settings. 11,12 However, access to treatment has not been equitable for HIV-positive PWID. 13 Treatment inequities are particularly acute in China, Malaysia, Russia, Ukraine, and Vietnam, where PWID carry a disproportionate burden of HIV. 4 Although PWID constitute an estimated 67% of HIV cases in these five countries, only 25% of individuals on HIV treatment are PWID. 4 PWID are also the group least likely to know their HIV statuses. 14

Inequities in access to HIV prevention programmes for PWID also exist. Despite clear evidence of the effectiveness of opioid substitution therapies in reducing the risks of HIV transmission, global estimates suggest that access remains inadequate because only 65% of the global PWID population lives in countries where opioid substitution therapy is available. 15,16 In the five aforementioned countries with the most well established injection-driven HIV epidemics, less than 2% of PWID have access to opioid substitution therapies. 4 Analyses also suggest that global coverage of programmes to exchange or distribute sterile needles and syringes, a central pillar of HIV prevention for PWID, are inadequate. 1

At present, reducing HIV incidence by improving HIV prevention and treatment for PWID is an urgent international priority, as identified by several high level initiatives, including the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets, which are aimed at substantially scaling up access to, and the effect of, HIV treatment by 2020. 8,14,17 Although practices at the individual level contribute to disparities in HIV infection rates and access to HIV prevention and treatment among PWID, mounting evidence generated over more than two decades suggests that higher-order or structural risk factors, including laws and policies criminalising drug use, could also have a central role in shaping health outcomes. 15,18,19,20 Criminalisation of drug use places PWID in precarious legal situations and estimates suggest that 56–90% of PWID will be incarcerated at some stage during their life. 21,22

International agencies and programmes such as UNAIDS identify criminalisation and punitive laws as a primary reason why the level of decline in HIV incidence and mortality taking place globally is not being observed in PWID. 2 However, there has been, to the best of our knowledge, no systematic assessment of the peer-reviewed research literature characterising the influence that laws and legal frameworks criminalising drug use might have on HIV prevention and treatment among PWID. Consequently, we did a systematic review to describe the association between criminalisation of drug use and HIV prevention and treatment among PWID.

METHODS

Search strategy and selection criteria

We completed this systematic review using PRISMA guidelines. 23 We searched MEDLINE, Embase, SCOPUS, PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), Web of Science, DARE (Database of Abstracts and Reviews of Effects via OVIDSP), Google Scholar, the National Library of Medicine’s Meeting Abstracts database, and online archives of the International AIDS Conference (IAC), the Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment, and Prevention (IAS), and the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) for studies published between Jan 1, 2006, and Dec 31, 2014. We also hand-searched reference lists of published reviews and relevant included studies.

Terms related to our three key concepts (PWIDs, criminalisation of drug use, and HIV prevention and treatment) were searched both as MeSH terms and as key words. A detailed MEDLINE search strategy is provided in the appendix (pp 1–3). To be included in our review, a study had to meet the following eligibility criteria: be published in a peer-reviewed journal or presented as a peer-reviewed abstract at a scientific conference; examine, through any study design, the association between an a-priori set of indicators related to the criminalisation of drugs and HIV prevention or treatment among PWID; provide sufficient details on the methods followed to allow critical assessment of quality; be published or presented between Jan 1, 2006, and Dec 31, 2014; and be published in the English language.

Our systematic review was done in two stages. We did the first search in 2012 and captured literature published for the years 2006–10. We did a second search in 2015 and captured literature published between the years 2011–14. We used the same methods and approaches for the two stages, and both searches were overseen by the same authors (TC and KD).

Data analysis

As a first step, all publication titles were screened by our trained reviewer (TC) to exclude articles that clearly did not meet the aforementioned inclusion criteria. The appendix (pp 4–6) provides an overview of indicators related to criminalisation and to HIV prevention and treatment used in our systematic review. If our reviewer coded the publication title as being potentially relevant, we reviewed the abstract of the article in full. If, after reviewing the abstract, our reviewer concluded that the publication was potentially relevant, we retrieved the full-text copy of the article.

Review of the full-text copy of articles, and data extraction for relevant articles, was done by one of our three trained reviewers (TC, L Ti, or H Han) and checked by a second reviewer (TC, L Ti, or H Han). Reviewers showed high agreement on article inclusion (86·7%), and discrepancies were reviewed and resolved by our senior study team member (KD). Data extraction was also checked by KD. To ensure consistency in data extraction, we developed a standardised form on the basis of a detailed results framework (appendix, pp 4–6) to manage data extraction for each eligible record. Our form included details on the following: the country where the research was done; study design; study sample characteristics (sample size, population); criminalisation indicators (18 categories); comparison group or condition; HIV prevention or treatment indicators (30 categories); and relevant findings, including the overall suggested effect of the criminalisation indicator on the HIV indicator or indicators. We used three possible categories for overall effect: beneficial, which described studies suggesting that criminalisation of drugs has a beneficial effect on HIV prevention or treatment (or, conversely, that reducing criminalisation has a negative effect on HIV prevention or treatment); null, which described studies suggesting that criminalisation of drugs has no effect on HIV prevention or treatment (or, similarly, that reducing criminalisation has no such effect); and negative, which described studies suggesting that criminalisation of drugs has a negative effect on HIV prevention or treatment (or, conversely, suggesting that reducing criminalisation has a beneficial effect).

Our assessment of the overall suggested effect of the criminalisation indicator on the HIV indicator or indicators was based on data reported in the studies. For example, if a criminalisation indicator (eg, street-level policing) was reported to be statistically associated with an HIV indicator (eg, syringe sharing), we used the direction of the statistical association to determine whether the study suggested that criminalisation had a beneficial effect (eg, street-level policing was reported to be negatively associated with syringe sharing) or a negative effect (eg, street-level policing was reported to be positively associated with syringe sharing). If there was no statistically significant association between the two indicators (eg, street-level policing and syringe sharing), we coded the study as suggesting a null association between criminalisation and HIV prevention and treatment.

We assessed the methodological quality of observational quantitative studies with a modified version of the Downs and Black checklist for reporting of health-care studies, which has been shown to be a reliable measure for observational studies (see appendix pp 7–8 for scoring criteria). 24,25 Out of a total score of 18, higher scores reflect stronger methodological quality. All eligible studies were assessed by two of our trained reviewers (TC and A Pilarinos).

Role of the funding source

The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study, and KD and SB had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

RESULTS

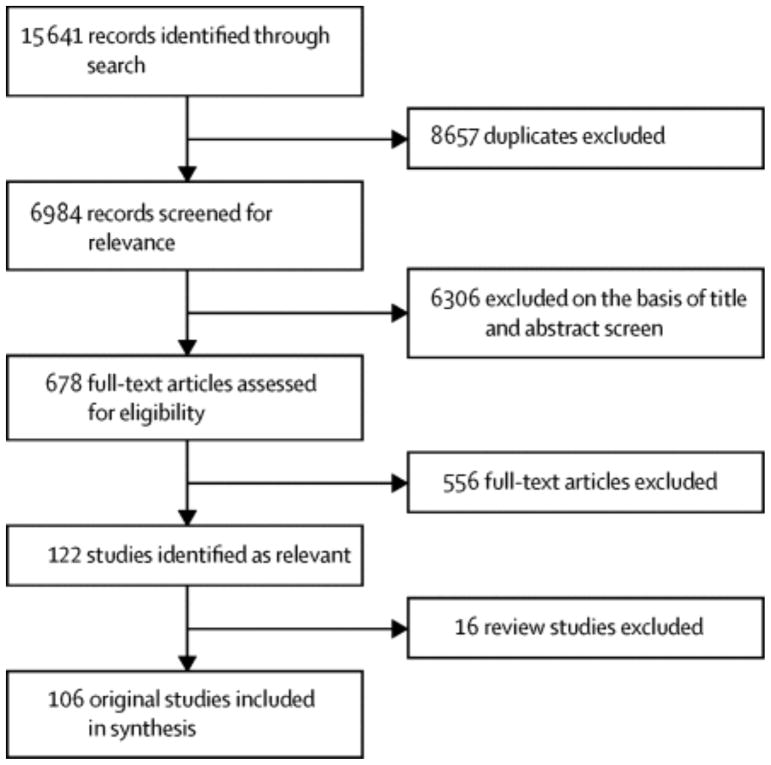

Our search criteria identified 15 641 citations (see appendix p 9 for records retrieved from each database), of which 6984 were unique records (figure 1). Our initial screening on the basis of the title and abstract excluded 6306 records. Following an assessment of the full text of the remaining 678 articles, we determined that 556 did not meet the inclusion criteria and these articles were excluded. We extracted data from the remaining 122 articles, of which 16 were review articles and therefore excluded from the final analysis. Our study synthesis was therefore based on 106 original studies, which are summarised in the table. These comprised 29 longitudinal studies (combined category for cohort studies, before and after interventions, and other longitudinal study designs; 27%), 49 cross-sectional studies (46%), two mixed methods studies (2%), four mathematical modelling studies (4%), and 22 qualitative studies (21%;appendix p 10). No randomised controlled trials were identified.

Figure 1.

Study selection

Table 1.

Summary of Included Studies n = 106

| Lead author, year, and country | Study design | Sample characteristics | Quality score | Criminalization indicator(s) | Comparison group or condition | HIV indicator(s) | Conclusions on impact of criminalization on HIV (& description of key findings) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosenblum 2013. Russia 1 | Ecological | IDU in Russia | 8 | National drug strategies | Before and after 2000 (when the Taliban began an anti-opium campaign) | HIV incidence among IDU | BENEFICIAL: Suggested criminalization has beneficial impact (The Afghani Taliban’s ban on opium production linked to reductions in HIV incidence among IDU in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and Russia) |

| Rhodes 2012. Moldova 2 | Qualitative | 42 lifetime IDU | N/A | Police crack downs | Before and after social and economic change in post-Soviet Europe | Drug injecting; Addiction treatment initiation and/or retention | BENEFICIAL: Suggested criminalization has beneficial impact (Policing associated with reductions in drug injecting and increases in OST enrolment) |

| Plugge 2009. England 3 | Cohort | 505 female, adult prisoners | 17 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Entry into prison vs. 1 month later | Drug injecting | BENEFICIAL: Suggests criminalization has beneficial impact (Incarceration led to reduction in drug use among women) |

| Wong 2009. Canada 4 | Cross-sectional | 478 youth drug users | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Ever attended addiction treatment vs. not | Addiction treatment initiation and/or retention | BENEFICIAL: Suggests criminalization has beneficial impact (Incarceration was positively associated with enrolment in additional treatment) |

| Cunningham 2008. USA 5 | Before and after intervention | 2.8 million adults in addictions treatment | 15 | Supply-side drug control interventions | Regulation changes and its effects on modes of methamphetamine administration: 1995 vs. 1996 vs. 1997 | Drug injecting | BENEFICIAL: Suggests criminalization has beneficial impact (Changes in US federal regulations of methamphetamine precursor chemicals (ephedrine and pseudoephedrine) were positively associated with reduction in injection of methamphetamine) |

| Koulierakis 2006. Greece 6 | Cross-sectional | 242 adult IDU | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Before imprisonment versus during imprisonment | Drug injecting; Syringe sharing. |

BENEFICIAL: Suggests criminalization has beneficial impact (Overall reduction in injecting takes place while in prison, compared with the outside) NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Those who continue injecting in prison take more risks by sharing more frequently) |

| Friedman 2011. USA 7 | Longitudin al modeling | IDU from 93 metropolitan areas | 14 | Street-level policing | Hard drug arrest rate in 1991 vs. 1992–2002 | Drug injecting | NULL: Suggests criminalization has null impact (Hard drug-related arrests associated with the population rate of IDUs in 1992, but not with changes in the IDU population over time) |

| Rondinelli 2009. USA 8 | Cross-sectional | 3209 youth-young adult IDU | 15 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | HIV positive individuals vs. HIV negative individuals | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NULL: Suggests criminalization has null impact (Incarceration was not associated with HIV infection) |

| Milloy 2009. Canada 9 | Cohort | 902 adult IDU | 17 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those reporting recent incarceration vs. those not reporting recent incarceration | Supervised drug consumption rooms | NULL: Suggests criminalization has null impact (Incarceration was not associated with SIF use) |

| Werb 2009. Thailand 10 | Cross-sectional | 252 adult IDU | 16 | Street-level policing | Those who reported observing an increase in police presence where they purchase/consume drugs in the past 6 months vs. those who did not | Drug injecting; Addiction treatment initiation and/or retention | NULL: Suggests criminalization has null impact (Increase in police presence not associated with reduction in drug injecting or increased addiction treatment engagement) |

| Friedman 2008. USA 11 | Mathematic al modeling | 96 metropolitan areas | n/a | Street-level policing | Time (1992–2002) | Drug injecting | NULL: Suggests criminalization has null impact (Hard drug arrests did not predict any measurable change in prevalence of IDU; no evidence that hard-drug arrests associated with decline in IDU prevalence) |

| Johnson 2006. USA 12 | Before and after intervention | New York’s Expanded Syringe Access Program (ESAP) | 9 | Drug paraphernalia laws or practices that penalize or deter possession of injecting paraphernalia | Before and after ESAP | Drug injecting; Addiction treatment initiation and/or retention | NULL: Suggests reduced criminalization has null impact (NEP not associated with an increase in drug use) |

| Kerr 2006. Canada 13 | Before and after intervention | 871 adult IDU | 12 | Exemptions from controlled drug and substances act (allowing for SIFs to operate) | Before and after SIF | Drug injecting | NULL: Suggests reduced criminalization has null impact (SIF not associated with an increase in drug use) |

| Palepu 2006. Canada 14 | Cohort | 278 HIV positive IDU | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | ART adherence | NULL: Suggests criminalization has null impact (Incarceration not associated with HAART adherence) |

| Cardoso 2006. Brazil 15 | Cross-sectional | 478 adult drug users, mostly IDU, half HIV positive | 15 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | HIV incidence among IDU | NULL: Suggests criminalization has null impact (Incarceration not associated with HIV incidence) |

| Huo 2006. USA 16 | Cohort | 707 adult IDU | 15 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | Drug injecting | NULL: Suggests criminalization has null impact (History of incarceration was not associated with injection cessation) |

| Chen 2013. China 17 | Cross-sectional | 613 IDU, majority male | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Number of times receiving compulsory drug treatment | Unprotected sex; syringe sharing; HIV prevalence among IDU |

NULL: Suggests reduced criminalization has null impact (Compulsory drug treatment not associated with condom use or syringe sharing) NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Compulsory drug treatment associated with increased risk of HIV infection) |

| Hayashi 2013. Thailand 18 | Cross-sectional | 468 adult IDU | 15 | Forced detention as addiction treatment; street-level policing | Various | Drug injecting; syringe sharing |

NULL: Suggests criminalization has null impact (Compulsory drug detention centers not associated with reductions in drug injecting) NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Police planting illicit drugs on IDU associated with syringe sharing) |

| DeBeck 2009. Canada 19 | Cohort | 1,603 adult IDU | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Before and after incarceration | Drug injecting |

NULL: Suggests criminalization has null impact (Incarceration not associated with significant changes in frequent drug use) NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration negatively associated with injection cessation) |

| Friedman 2006. USA 20 | Cross-sectional | 89 large metropolitan areas | 15 | Street-level policing | Different metropolitan areas | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed); drug injecting |

NULL: Suggests criminalization has null impact (Policing had no impact on prevalence of drug injecting) NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Criminalization has negative impact on HIV prevalence) |

| Caiaffa 2006. Brazil 21 | Cross-sectional | 1144 adult IDU | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) |

NULL: Suggests criminalization has null impact (Incarceration was not positively associated with HIV infection across all settings) NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration was positively associated with HIV infection in some groups) |

| Gu 2014. China 22 | Cross-sectional | 133 adults on methadone treatment | 13 | Street-level policing | Those who worry about police arrest vs. not | Addiction treatment initiation and/or retention | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Concern about arrest associated with nonattendance at methadone clinic) |

| Kerr 2014. Thailand 23 | Cross-sectional | 435 adult IDU | 14 | Forced detention as addiction treatment | Those with exposure to compulsory drug detention vs. not | HIV testing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Exposure to compulsory drug detention positively associated with avoiding healthcare services) |

| Rahnama 2014. Iran 24 | Cross-sectional | 572 male, adult IDU | 13 | National drug strategies | Before and after large-scale implementation of harm reduction programs | Needle exchange programs | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (After implementing harm reduction programs, awareness and use of NEPs was relatively high among IDU in Tehran) |

| Madden 2014. Australia 25 | Before and after intervention | IDU in Australia | 9 | National drug strategies | Before and after implementation of harm reduction policies | Outreach (community, peer educators, public health nurses, street teams); HIV incidence among IDU | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Australia’s public health and human rights-based approach to harm reduction contributed to a relatively low prevalence of HIV among IDU) |

| Huang 2014. Taiwan 26 | Cross-sectional | 3,851 prisoners and 4,357 cohort participants | 18 | National drug strategies | Before and after the introduction of nationwide harm reduction services in 2006 | HIV incidence among IDU; HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (The harm reduction program contributed to significant reductions in HIV incidence and prevalence among IDU) |

| Werb 2014. Canada 27 | Mathematical modeling | Canadian prisoners | 13 | Prohibitions on or restrictions to OST, NEPs or other evidence-informed HIV prevention interventions | Before and after proposed introduction of NEPs in prisons | HIV incidence among IDU | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Modeling indicates that prison-based NEPs may reduce HIV incidence in prisons) |

| Ngo 2014. Vietnam 28 | Cross-sectional | 1,080 male IDU | 12 | Street-level policing | Those with past experience being stopped by police in relation to drug use vs. not | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Street-level policing associated with syringe sharing) |

| Lunze 2014. Russia 29 | Cross-sectional | 582 HIV positive IDU | 15 | Street-level policing | Those who experienced extra-judicial police arrests (needle possession or for needles or drugs planted by police) vs. not | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Extrajudicial police arrests associated with receptive needle sharing) |

| Beletsky 2014. USA 30 | Cross-sectional | 514 IDU, majority male | 14 | Street-level policing | Those whose syringes were confiscated by police vs. not | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Syringe confiscation associated with receptive syringe sharing) |

| Izenberg 2013. Ukraine 31 | Cross-sectional | 94 HIV positive IDU recently released from prison | 15 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those who experienced unofficial detention vs. not | Addiction treatment initiation and/or retention; ART adherence | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Detention associated with ART and OST treatment interruptions) |

| Ti 2013. Thailand 32 | Cross-sectional | 350 IDU who either HIV negative or status is unknown | 13 | Street-level policing | Those who noticed an increased police presence when buying or using drugs in last six months vs. not | HIV testing and counselling | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Increased police presence associated with HIV test avoidance) |

| Chakrapani 2013. India 33 | Qualitative | 23 IDU with history of incarceration; 4 key informants | N/A | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Before and during prison time | ART adherence | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration linked with ART interruptions) |

| Wen-Jing 2013. Taiwan 34 | Before and after intervention | IDU in Taiwan | 8 | National drug strategies | Before and after the implementation of the national pilot harm reduction program | HIV incidence among IDU | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Taiwan’s national pilot harm reduction program linked to a decrease in HIV incidence) |

| Ti 2013. Canada 35 | Cohort | 991 street-involved youth who use drugs | 15 | Street-level policing | Those who experienced police confrontation vs. not | Drug injecting | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Being stopped, searched, or detained by police without arrest associated with any drug injecting) |

| Hayashi 2013. Thailand 36 | Cross-sectional | 42–718 adult IDU (multiple studies) | 16 | Street-level policing | Various | Syringe sharing; HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Exposure to single and multiple street-level policing tactics associated with syringe sharing and HIV seropositivity) |

| Lin 2013. Taiwan 37 | Cross-sectional | 781 methadone seekers, majority IDU | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with more drug-related convictions vs. less | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Drug-related criminal convictions linked with HIV seropositivity) |

| Beletsky 2013. Mexico 38 | Cross-sectional | 624 female IDU who are sex workers and are at risk for HIV | 15 | Street-level policing | Those who have had syringes confiscated by police vs. not | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Syringe confiscation associated with HIV seropositivity) |

| Wagner 2013. USA 39 | Mixed methods | 217 IDU | 13 | Street-level policing | Those concerned about getting a ticket or being arrested for carrying a needle or cooker vs. not | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Fear of street-level policing associated with receptive syringe sharing) |

| Pan 2013. Canada 40 | Cohort | 372 people who use drugs, majority IDU | 15 | Street-level policing | Those exposed to street-based policing vs. not | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Being stopped by police associated with syringe sharing) |

| Smith 2012. China 41 | Cross-sectional | 18 key informants | 9 | National drug strategies | Before and after legalization of methadone. | Addiction treatment initiation and/or retention; HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Implementation of harm reduction policies [primarily OST, some NEPs] linked to increased access to methadone among IDU and averted HIV infections) |

| Fatseas 2012. France 42 | Cross-sectional | 648 IDU, majority male | 17 | National drug strategies | Before and after the introduction of harm reduction policies (1995) | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed); syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Implementation of harm reduction policies associated with decreases in HIV prevalence, and sharing syringes and drug paraphernalia) |

| Csete 2012. Switzerland 43 | Qualitative | Key informants | N/A | National drug strategies | Before and after the 1990’s | OST and drug dependence treatment; Addiction treatment initiation and/or retention | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Reducing restrictions on methadone use associated with increased enrolment in methadone treatment) |

| Lee 2012. Taiwan 44 | Cross-sectional | Attendees of methadone treatment centers and NEPs | 13 | National drug strategies | Those living in areas where the National Pilot Harm Reduction Program (PHRP) was implemented vs. not | HIV incidence among IDU | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (National Pilot Harm Reduction Program associated with relative reductions in HIV incidence) |

| Cooper 2012. USA145,46 | Longitudin al modeling | 4,067 & 4,178 IDU, majority male (multiple studies) | 15 | Street-level policing | District-level exposure to drug-related arrest | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Arrest rates elevate the odds of injecting with an unsterile syringe and undermine the effects of better NEP access) |

| Peng 2011. Taiwan 47 | Cross-sectional | 114 cases who are HIV +; 149 controls who are HIV−; all female prisoners | 15 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Number of times imprisoned | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Multiple incarcerations associated with HIV seropositivity) |

| Volkmann 2011. Mexico 48 | Cross-sectional | 727 IDU | 16 | Street-level policing | Those exposed to street-based policing vs. not | Drug injecting | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Street-level policing linked to frequent injection drug use) |

| Strathdee 2011. Mexico 49 | Cross-sectional | 620 female IDU sex workers | 14 | Street-level policing | Those whose syringes were confiscated by police vs. not | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Syringe confiscation in exchange for no arrest associated with HIV seropositivity) |

| El Dabaghi 2010. Lebanon 50 | Cross-sectional | 424 adult prisoners; 55 prison staff | 8 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | No comparison group | Syringe sharing; drug injecting; unprotected sex | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration described as an environment where high risk behaviours take place, including injecting, syringe sharing, and unprotected sex) |

| Mimiaga 2010. Ukraine 51 | Qualitative | 16 HIV positive, adult IDU | n/a | Street-level policing | No comparison group. | ART adherence; Addiction treatment initiation and/or retention | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Police practices identified as barrier to ART adherence and OST access) |

| Kerr 2010. Canada 52 | Cohort | 740 adult IDU | 14 | Prohibitions on or restrictions to OST, NEPs or other evidence-informed HIV prevention interventions | Before and after change NEP in policy (relaxation of rules) | Syringe sharing; HIV incidence among IDU | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Expansion of syringe distribution associated with reduction of syringe sharing and decline in HIV incidence) |

| Kheirandish 2010. Iran 53 | Cross-sectional | 459 male, adult, IDU prisoners, one quarter HIV positive | 14 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | History of using opioids in jail vs. no history of using opioids in jail | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Using opiates in jail positively associated with HIV infection) |

| Sarang 2010. Russia 54 | Qualitative | 209 youth-adult IDU in 3 Russian cities | n/a | Street-level policing | No comparison group | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Fear of arrest from police attributed to syringe sharing and reluctance to access sterile syringes) |

| Philbin 2010. China 55 | Qualitative | 20 adult IDU using NEPs or methadone; 15 non-government service providers | n/a | Street-level policing | No comparison group | Addiction treatment initiation and/or retention | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Police identified as barrier to accessing methadone) |

| Shahbazi 2010. Iran 56 | Before and after intervention | 341 IDU prisoners | 11 | Prohibitions on or restrictions to OST, NEPs or other evidence-informed HIV prevention interventions | Before and after introduction of NEP in prison | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Introduction of NEP in prison in Iran reduced syringe sharing) |

| Pinkerton 2010. Canada 57 | Mathematical modeling | Insite (Vancouver SIF) | n/a | Exemptions from controlled drug and substances act (allowing for SIFs to operate) | Vancouver with and without SIF | HIV incidence among IDU | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Mathematical modeling suggests that SIF prevents HIV incidence) |

| Fairbairn 2010. Canada 58 | Qualitative | 20 adult IDU | n/a | Prohibitions on or restrictions to OST, NEPs or other evidence-informed HIV prevention interventions | No comparison group | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Prohibition on assisted injection in Vancouver SIF described as barrier to using facility and led individuals to allow others to inject them outside the facility; assisted injection positively associated with syringe sharing and HIV infection) |

| Strathdee 2010. Global (emphasis on Ukraine, Pakistan and Kenya) 59 | Mathematic al modeling | 94 studies | n/a | Street-level policing; Prohibitions on or restrictions to OST, NEPs or other evidence-informed HIV prevention interventions; Drug paraphernalia laws or practices that penalize or deter possession of injecting paraphernalia | Various | HIV incidence among IDU; HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed); Needle exchange programs; OST and drug dependence treatment; prevalence of IDU on HAART | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Mathematical modeling suggests eliminating police beating would reduce HIV infection in Ukraine by 2–19%; availability of OST would decrease HIV incidence by 28% in Karachi; provision of combination interventions (scale up NEP, OST and ART for IDU) would reduce HIV infections by 67% in Nairobi) |

| Bravo 2009. Spain 60 | Cross-sectional | 249 youth IDU | 13 | Exemptions from controlled drug and substances act (allowing for SIFs to operate) | SIF users vs. non-SIF users | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (SIF users less likely to borrow used syringes) |

| Ngo 2009. Vietnam 61 | Qualitative | 23 government and non-government informants; 8 IDU | n/a | Police crack downs | No comparison group | Outreach (community, peer educators, public health nurses, street teams); Needle exchange programs | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Police crack downs described as limiting needle and syringe distribution and outreach efforts) |

| Vahdani 2009. Iran 62 | Cross-sectional | 202 homeless adults, one-third IDU | 15 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | HBV positive individuals vs. HCV positive individuals vs. HIV positive individuals | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Previous imprisonment positively associated with HIV infection) |

| Des Jarlais 2009. USA 63 | Before and after intervention | 2,312 adult IDU attending drug detoxification program | 15 | Prohibitions on or restrictions to OST, NEPs or other evidence-informed HIV prevention interventions | Before and after large-scale needle exchanges were implemented in New York | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed); syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Expanding/implementing large scale syringe exchange program associated with reduction in HIV prevalence and syringe sharing) |

| Rafiey 2009. Iran 64 | Cross-sectional | 2091 male, adult IDU from treatment centers, prisons, and streets | 15 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those who ever shared syringes vs. not | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Arrest and history of imprisonment positively associated with ever sharing syringes) |

| Krusi 2009. Canada 65 | Qualitative | 22 HIV positive adult IDU attending HIV care program; 7 staff members of HIV care program | n/a | Exemptions from controlled drug and substances act (allowing for SIFs to operate) | HIV care staff vs. HIV care attendees | Targeted information, education and communication for IDUs and their sexual partners | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Supervised injection supported IDU access to HIV prevention education) |

| Hayashi 2009. Thailand 66 | Cross-sectional | 252 adults, majority IDU | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | Syringe sharing; drug injecting | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration positively associated with syringe sharing and injecting midazolam) |

| Small 2009. Canada 67 | Qualitative | 12 HIV positive, male, adult, IDU on HAART | n/a | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | No comparison group | ART adherence; prevalence of IDU on HAART | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration described as deterring/creating difficulties for IDU to access HAART) |

| Pollini 2009. Mexico 68 | Cross-sectional | 898 male, adult IDU | 15 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention); Street-level policing; Drug paraphernalia laws or practices that penalize or deter possession of injecting paraphernalia | Ever incarcerated vs. ever injected while incarcerated vs. ever engaged in receptive sharing while incarcerated | Drug injecting; Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Being arrested for sterile syringe possession independently associated with injecting drugs during incarceration; multiple incarcerations independently associated with syringe sharing in prison) |

| Suntharasamai 2009. Thailand 69 | Cohort | 2,295 adult IDU, HIV negative at baseline | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | HIV incidence among IDU | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration was positively associated with HIV incidence) |

| Milloy 2009. Canada 70 | Cohort | 889 adult IDU | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Release from prison associated with syringe sharing) |

| Thomson 2009. Thailand 71 | Cross-sectional | 1189 young adults, half IDU, majority HIV positive | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration positively associated with HIV infection) |

| Thanh 2009. Viet Nam 72 | Qualitative | 45 HIV positive, adult IDU | n/a | Street-level policing; Drug paraphernalia laws or practices that penalize or deter possession of injecting paraphernalia | No comparison group | Outreach (community, peer educators, public health nurses, street teams); Needle exchange programs; reluctance to carry sterile syringes | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Policing practices and fear of arrest described as deterrent for carrying syringes and distributing syringes by peer educators) |

| Reid 2009. China 73 | Qualitative | 39 government and non-government informants representing 19 stakeholder bodies across China | n/a | Police crack downs | No comparison group | Addiction treatment initiation and/or retention; Needle exchange programs; HIV testing and counselling | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Policing practices found to limit access to HIV prevention programs and interventions including addiction treatment; also found to inhibit delivery of services) |

| Sheue-Rong 2008. Taiwan 74 | Cohort | 3,229 IDU enrolled in methadone program | 9 | National drug strategies | HIV incidence before and after harm reduction campaign | HIV incidence among IDU | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Introduction of harm reduction campaign (methadone, syringe exchange program, HIV screening and counseling services) associated with 43% decrease in new HIV infectors one year after intervention, and additional 44% decrease the following year) |

| Schleifer 2008. Thailand 75 | Qualitative | 50 stakeholders; 50 drug users from 5 Thai provinces. | n/a | National drug strategies | No comparison group | ART/HAART; Prevalence of IDU on HAART | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (National drug policies and policing practices described as barriers to getting IDU onto ART/HAART) |

| Pollini 2008. Mexico 76 | Cross-sectional | 428 adult IDU | 16 | Street-level policing; Drug paraphernalia laws or practices that penalize or deter possession of injecting paraphernalia | Arrested for carrying syringes vs. not | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Being arrested for carrying syringes positively associated with receptive syringe sharing) |

| Philbin 2008. Mexico 77 | Cross-sectional | 427 adult IDU | 15 | Street-level policing; Drug paraphernalia laws or practices that penalize or deter possession of injecting paraphernalia | Attending shooting galleries vs. not | Syringe sharing; Shooting gallery attendance | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Policing practices positively associated with shooting gallery attendance, which is associated with syringe sharing) |

| Chen 2008. Taiwan 78 | Cross-sectional | 241 male, adult, prisoners, mostly IDU, half HIV positive | 15 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | HIV positive individuals vs. HIV negative individuals | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration positively associated with HIV infection) |

| Azim 2008. Bangladesh 79 | Cross-sectional | 561 male, youth-adult IDU | 15 | Street-level policing | Ever arrested for being a drug user vs. not | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Being arrested for being a drug user positively associated with HIV infection) |

| Miller 2008. Mexico 80 | Qualitative | 43 adult IDU | n/a | Street-level policing; Drug paraphernalia laws or practices that penalize or deter possession of injecting paraphernalia | No comparison group | Reluctance to carry sterile syringes | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Policing practices deter IDU from carrying sterile injecting equipment) |

| Strathdee 2008. Mexico 81 | Cohort | 1056 adult IDU | 14 | Street-level policing | HIV positive individuals vs. HIV negative individuals | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Being arrested for having track-marks was independently associated with HIV infection) |

| Epperson 2008. USA 82 | Cross-sectional | 356 male adults, one-quarter IDU | 14 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Recent criminal justice involvement vs. no recent criminal justice involvement | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed); syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration positively associated with syringe sharing and HIV prevalence) |

| Milloy 2008. Canada 83 | Cohort | 902 adult IDU | 17 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Reporting an incarceration event vs. not reporting an incarceration event | Syringe sharing; HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration positively associated with syringe sharing and HIV prevalence) |

| Werb 2008. Canada 84 | Cohort | 1247 adult IDU | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | Syringe sharing; unprotected sex | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration positively associated with unprotected sex and syringe sharing) |

| Cohen 2008. China 85 | Qualitative | 19 adult IDU; 20 government and non-government informants | n/a | Street-level policing; Drug paraphernalia laws or practices that penalize or deter possession of injecting paraphernalia | No comparison group | HIV testing; Needle exchange programs; Addiction treatment initiation and/or retention | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Policing practices and fear of arrest described as creating barriers for getting tested for HIV, getting sterile syringes, and accessing methadone programs) |

| Neaigus 2008. USA 86 | Cross-sectional | 526 adult IDU | 16 | Prohibitions on or restrictions to OST, NEPs or other evidence-informed HIV prevention interventions | New Jersey residents (no NPSS) vs. New York residents (NPSS) | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed); syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Prohibitions on syringe distribution programs positively associated with syringe sharing and higher HIV prevalence among IDU) |

| Courtenay-Quirk 2008. USA 87 | Cross-sectional | 581 HIV positive adults, one-quarter IDU | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | Prevalence of sustained undetectable viral load among IDU | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration negatively associated with having an undetectable viral load) |

| Werb 2008. Canada 88 | Cross-sectional | 465 adult IDU | 14 | Street-level policing; Drug paraphernalia laws or practices that penalize or deter possession of injecting paraphernalia | Those who have been stopped by police in the last 6 months vs. those who have not | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Street-level policing positively associated with syringe sharing) |

| Tempalski 2008. USA 89 | Cross-sectional | 72 NEPs within 35 metropolitan areas that report heroin as the dominant drug | 16 | Prohibitions on or restrictions to OST, NEPs or other evidence-informed HIV prevention interventions | NEP coverage in different metropolitan areas | Needle exchange programs | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Government funding of NEPs contributes to better syringe coverage) |

| Sarang 2008. Russia 90 | Qualitative | 1682 youth-adult IDU | 16 | Street-level policing; Drug paraphernalia laws or practices that penalize or deter possession of injecting paraphernalia | No comparison group | Needle exchange programs; reluctance to carry sterile syringes | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Street-level policing linked with reluctance to access NEPs, and therefore less access to sterile syringes) |

| Shannon 2008. Canada 91 | Qualitative | 46 female sex workers | n/a | Street-level policing; Drug paraphernalia laws or practices that penalize or deter possession of injecting paraphernalia | No comparison group | Needle exchange programs; unprotected sex; reluctance to carry sterile syringes | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Policing reduces willingness to carry clean syringes and limits access to HIV prevention services, and increases risk for unprotected sex) |

| Raykhert 2008. Ukraine 92 | Cross-sectional | 1507 adults infected with tuberculosis | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Civilians vs. penitentiary | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration positively associated with HIV infection) |

| Wood 2007. Canada 93 | Cohort | 1031 adult IDU | 16 | Exemptions from controlled drug and substances act (allowing for SIFs to operate) | Before and after SIF opening | Addiction treatment initiation and/or retention | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Allowing SIF to operate associated with increased entry into addiction treatment) |

| Rich 2007. USA 94 | Cross-sectional | 473 adult drug users | 15 | Prohibitions on or restrictions to OST, NEPs or other evidence-informed HIV prevention interventions | Rhode Island (legal NPSS) vs. Massachusetts (no legal NPSS) | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (Legalization of non-prescription sterile syringes in Rhode Island associated with reductions in syringe sharing when compared with Massachusetts where syringes remained outlawed) |

| Rácz 2007. Hungary 95 | Qualitative | 150 youth IDU | n/a | Street-level policing; Drug paraphernalia laws or practices that penalize or deter possession of injecting paraphernalia | No comparison group | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Syringe sharing positively associated with Street-level policing) |

| Razani 2007. Iran 96 | Qualitative | 40 government and non-government informants; 66 adult IDU | n/a | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | No comparison group | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration positively associated with syringe sharing) |

| Bluthenthal 2007. USA 97 | Cross-sectional | 24 NEPs, 1576 adult IDU | 16 | Prohibitions on or restrictions to OST, NEPs or other evidence-informed HIV prevention interventions | Syringe dispensation policies: needs-based vs. one-for-one plus some additional syringes vs. strict one-for-one | Needle exchange programs | NEGATIVE: Suggests reduced criminalization has beneficial impact (When restrictions on NEP dispensation policies decreased, adequate syringe coverage increased) |

| Dolan 2007. USA 98 | Cohort | 258 HIV positive, adult, IDU | 15 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | ART adherence | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration negatively associated with poorer responses (virologic and immunologic) after HAART initiation) |

| Rhodes 2006. Russia 99 | Qualitative | 27 adult police officers | n/a | Street-level policing; Drug paraphernalia laws or practices that penalize or deter possession of injecting paraphernalia | No comparison group | Needle exchange programs | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Policing practices are barriers to accessing NEP/sterile syringes) |

| Davis 2006. USA 100 | Cross-sectional | 637 youth-adult drug users | 16 | Street-level policing | Those with criminal justice involvement vs. not | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration positively associated with HIV infection) |

| Rhodes 2006. Russia 101 | Cross-sectional | 1473 youth-adult IDU | 15 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration positively associated with HIV infection) |

| Small 2006. Canada 102 | Qualitative | 30 adult IDU; 9 service providers | n/a | Street-level policing | No comparison group | Outreach (community, peer educators, public health nurses, street teams); syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Policing observed to have negative impact on multiple HIV prevention indicators) |

| Tyndall 2006. Canada 103 | Cohort | 1035 adult IDU | 17 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration positively associated with HIV infection) |

| Zamani 2006. Iran 104 | Cross-sectional | 207 male, adult IDU | 16 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | HIV prevalence among IDU (diagnosed and undiagnosed) | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration positively associated with HIV infection) |

| Miller 2006. Canada 105 | Cohort | 542 young adult IDU | 15 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Age of injection initiation: younger vs. older | Drug injecting | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration associated with initiating injecting at a younger age) |

| Sarang 2006. Russia 106 | Qualitative | 209 youth-adult IDU | n/a | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | No comparison group | Syringe sharing | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration positively associated with syringe sharing due to lack of availability of sterile syringes) |

| Callon 2006. Canada 107 | Cohort | 1463 adult IDU | 15 | Incarceration (Jails, prisons, detention) | Those with history of incarceration vs. not | Addiction treatment initiation and/or retention | NEGATIVE: Suggests criminalization has negative impact (Incarceration negatively associated with MMT) |

Includes two similar studies: (i) Cooper, Hannah LF, et al. “Drug-related arrest rates and spatial access to syringe exchange programs in New York City health districts: Combined effects on the risk of injection-related infections among injectors.” Health & Place 18.2 (2012): 218–228; (ii) Cooper, Hannah, et al. “Spatial access to sterile syringes and the odds of injecting with an unsterile syringe among injectors: A longitudinal multilevel study.” Journal of Urban Health 89.4 (2012): 678–696.

REFERENCE

Rosenblum D, Jones M. Did the Taliban’s opium eradication campaign cause a decline in HIV infections in Russia? Subst Use Misuse 2013; 48(6): 470–6.

Rhodes T, Bivol S. “Back then” and “nowadays”: social transition narratives in accounts of injecting drug use in an East European setting. Soc Sci Med 2012; 74(3): 425–33.

Plugge E, Yudkin P, Douglas N. Changes in women’s use of illicit drugs following imprisonment. Addiction 2009; 104(2): 215–22.

Wong J, Marshall BDL, Kerr T, Lai C, Wood E. Addiction treatment experience among a cohort of street-involved youths and young adults. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse 2009; 18(4): 398–409.

Cunningham JK, Liu L, Muramoto M. Methamphetamine suppression and route of administration: precursor regulation impacts on snorting, smoking, swallowing and injecting. Addiction 2008; 103(7): 1174–86.

Koulierakis G. Drug use and related precautions prior to imprisonment, inside prison and intentions after release among Greek inmates. Addiction Research & Theory 2006; 14(3): 217–33.

Friedman SR, Pouget ER, Chatterjee S, et al. Drug arrests and injection drug deterrence. American journal of public health 2011; 101(2): 344–9.

Rondinelli AJ, Ouellet LJ, Strathdee SA, et al. Young adult injection drug users in the United States continue to practice HIV risk behaviors. Drug and alcohol dependence 2009; 104(1): 167–74.

Milloy MJ, Wood E, Tyndall M, Lai C, Montaner J, Kerr T. Recent incarceration and use of a supervised injection facility in Vancouver, Canada. Addiction Research & Theory 2009; 17(5): 538–45.

Werb D, Hayashi K, Fairbairn N, et al. Drug use patterns among Thai illicit drug injectors amidst increased police presence. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy 2009; 4(1): 16–.

Friedman S, Brady J, Tempalski B, Flom P, Cooper H. Increasing arrests for heroin and cocaine possession (“hard-drug arrests”) are not associated with decreasing proportions of injection drug users (IDU) in metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs). Oral Abstract Session: AIDS 2008 - XVII International AIDS Conference: Abstract no TUAE0202; 2008; 2008.

Johnson BD, Golub AL, Deren S, Des Jarlais D. The nonimpact of the expanded syringe access program upon heroin use, injection behaviours, and crime indicators in New York City and State. Justice Research and Policy 2006; 8(1): 27–50.

Kerr T, Stoltz JA, Tyndall M, et al. Impact of a medically supervised safer injection facility on community drug use patterns: a before and after study. BMJ 2006; 332(7535): 220–2.

Palepu A, Tyndall MW, Joy R, et al. Antiretroviral adherence and HIV treatment outcomes among HIV/HCV co-infected injection drug users: the role of methadone maintenance therapy. Drug and alcohol dependence 2006; 84(2): 188–94.

Cardoso MN, Caiaffa WT, Mingoti SA, Projeto ADEB, II. AIDS incidence and mortality in injecting drug users: the AjUDE-Brasil II Project. Cadernos de Saude Publica 2006; 22(4): 827–37.

Huo D, Bailey SL, Ouellet LJ. Cessation of injection drug use and change in injection frequency: the Chicago Needle Exchange Evaluation Study. Addiction 2006; 101(11): 1606–13.

Chen HT, Tuner N, Chen CJ, Lin H-Y, Liang S, Wang S. Correlations Between Compulsory Drug Abstinence Treatments and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Injection Drug Users in a Border City of South China. AIDS Education & Prevention 2013; 25(4): 336–48.

Hayashi K, Ti L, Fairbairn N, et al. Drug-related harm among people who inject drugs in Thailand: Summary findings from the Mitsampan Community Research Project. Harm Reduction Journal 2013; 10(1).

DeBeck K, Kerr T, Li K, Milloy M, Montaner J, Wood E. Incarceration and drug use patterns among a cohort of injection drug users. Addiction 2009; 104(1): 69–76.

Friedman SR, Cooper HL, Tempalski B, et al. Relationships of deterrence and law enforcement to drug-related harms among drug injectors in US metropolitan areas. AIDS 2006; 20(1): 93.

Caiaffa WT, Bastos FI, Freitas LL, et al. The contribution of two Brazilian multi-center studies to the assessment of HIV and HCV infection and prevention strategies among injecting drug users: the AjUDE-Brasil I and II Projects. Cadernos de Saude Publica 2006; 22(4): 771–82.

Gu J, Xu HF, Lau JTF, et al. Situation-specific factors predicting nonadherence to methadone maintenance treatment: a cross-sectional study using the case-crossover design in Guangzhou, China. Aids Care-Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of Aids/Hiv 2014; 26: S107–S12.

Kerr T, Hayashi K, Ti L, Kaplan K, Suwannawong P, Wood E. The impact of compulsory drug detention exposure on the avoidance of healthcare among injection drug users in Thailand. International Journal of Drug Policy 2014; 25(1): 171–4.

Rahnama R, Mohraz M, Mirzazadeh A, et al. Access to harm reduction programs among persons who inject drugs: Findings from a respondent-driven sampling survey in Tehran, Iran. International Journal of Drug Policy 2014; 25(4): 717–23.

Madden A, Wodak A. Australia’s response to HIV among people who inject drugs. AIDS Education & Prevention 2014; 26(3): 234–44.

Huang YF, Yang JY, Nelson KE, et al. Changes in HIV Incidence among People Who Inject Drugs in Taiwan following Introduction of a Harm Reduction Program: A Study of Two Cohorts. PLoS Medicine 2014; 11(4).

Werb D. Estimating the number of HIV and hepatitis C cases averted through the implementation of federal prison-based needle exchange programs in Canada. 20th International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2014); 2014; Melbourne, Australia; 2014.

Ngo H, Mundy G, Neukom J. Factors associated with needle syringe sharing in Vietnam. 20th International AIDS Conference (AIDS 2014); 2014; Melbourne, Australia; 2014.

Lunze K, Raj A, Cheng DM, et al. Punitive policing and associated substance use risks among HIV-positive people in Russia who inject drugs. Journal of the International Aids Society 2014; 17.

Beletsky L, Heller D, Jenness SM, Neaigus A, Gelpi-Acosta C, Hagan H. Syringe access, syringe sharing, and police encounters among people who inject drugs in New York City: A community-level perspective. International Journal of Drug Policy 2014; 25(1): 105–11.

Izenberg JM, Bachireddy C, Soule M, Kiriazova T, Dvoryak S, Altice FL. High rates of police detention among recently released HIV-infected prisoners in Ukraine: Implications for health outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 2013; 133(1): 154–60.

Ti L, Hayashi K, Kaplan K, et al. HIV test avoidance among people who inject drugs in Thailand. AIDS and Behavior 2013; 17(7): 2474–8.

Chakrapani V, Kamei R, Kipgen H, Kh JK. Access to harm reduction and HIV-related treatment services inside Indian prisons: experiences of formerly incarcerated injecting drug users. International journal of prison health 2013; 9(2): 82–91.

Wen-Jing Y, Wen-Ing T, Jih-Heng L. Current status of substance abuse and HIV in Taiwan. Journal of Food & Drug Analysis 2013; 21: s27–32.

Ti LP, Wood E, Shannon K, Feng C, Kerr T. Police confrontations among street-involved youth in a Canadian setting. International Journal of Drug Policy 2013; 24(1): 46–51.

Hayashi K. Policing and public health: experiences of people who inject drugs in Bangkok, Thailand [PhD Dissertation]; 2013.

Lin TY, Chen VCH, Lee CH, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and risk perception of HIV infection among heroin users in Central Taiwan. Kaohsiung Journal of Medical Sciences 2013; 29(12): 673–9.

Beletsky L, Lozada R, Gaines T, et al. Syringe confiscation as an HIV risk factor: the public health implications of arbitrary policing in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. Journal of Urban Health 2013; 90(2): 284–98.

Wagner KD, Simon-Freeman R, Bluthenthal RN. The Association Between Law Enforcement Encounters and Syringe Sharing Among IDUs on Skid Row: A Mixed Methods Analysis. Aids and Behavior 2013; 17(8): 2637–43.

Pan SW, Christian CWM, Pearce ME, et al. The Cedar Project: Impacts of policing among young Aboriginal people who use injection and non-injection drugs in British Columbia, Canada. International Journal of Drug Policy 2013; 24(5): 449–59.

Smith K, Bartlett N, Wang N. A harm reduction paradox: Comparing China’s policies on needle and syringe exchange and methadone maintenance. International Journal of Drug Policy 2012; 23(4): 327–32.

Fatseas M, Denis C, Serre F, Dubernet J, Daulouède J-P, Auriacombe M. Change in HIV-HCV Risk-Taking Behavior and Seroprevalence Among Opiate Users Seeking Treatment Over an 11-year Period and Harm Reduction Policy. AIDS & Behavior 2012; 16(7): 2082–90.

Csete J, Grob PJ. Switzerland, HIV and the power of pragmatism: Lessons for drug policy development. International Journal of Drug Policy 2012; 23(1): 82–6.

The Global Addiction Conference… Global Addiction Conference, Lisbon, Portugal, December, 2011. Journal of Alcohol & Drug Education 2012; 56(2): 7–57.

Cooper HLF, Des Jarlais DC, Tempalski B, Bossak BH, Ross Z, Friedman SR. Drug-related arrest rates and spatial access to syringe exchange programs in New York City health districts: Combined effects on the risk of injection-related infections among injectors. Health and Place 2012; 18(2): 218–28.

Cooper H, Des Jarlais D, Ross Z, Tempalski B, Bossak BH, Friedman SR. Spatial access to sterile syringes and the odds of injecting with an unsterile syringe among injectors: a longitudinal multilevel study. Journal of Urban Health 2012; 89(4): 678–96.

Peng EYC, Yeh CY, Cheng SH, et al. A case-control study of HIV infection among incarcerated female drug users: Impact of sharing needles and having drug-using sexual partners. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association 2011; 110(7): 446–53.

Volkmann T, Lozada R, Anderson CM, Patterson TL, Vera A, Strathdee SA. Factors associated with drug-related harms related to policing in Tijuana, Mexico. Harm Reduction Journal 2011; 8.

Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Martinez G, et al. Social and Structural Factors Associated with HIV Infection among Female Sex Workers Who Inject Drugs in the Mexico-US Border Region. Plos One 2011; 6(4).

El Dabaghi L, El Nakib M, Abdallah A. Situation assessment on drug use and HIV and AIDS in the prison setting in Lebanon. International Conference on AIDS; 2010; Vienna, Austria; 2010.

Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA, Dvoryak S, Reisner SL, Needle R, Woody G. ‘We fear the police, and the police fear us’: structural and individual barriers and facilitators to HIV medication adherence among injection drug users in Kiev, Ukraine. AIDS Care 2010; 22(11): 1305–13.

Kerr T, Small W, Buchner C, et al. Syringe sharing and HIV incidence among injection drug users and increased access to sterile syringes. American Journal of Public Health 2010; 100(8): 1449.

Kheirandish P, Seyedalinaghi SA, Hosseini M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of HIV infection among male injection drug users in detention in Tehran, Iran. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS 2010; 53(2): 273–5.

Sarang A, Rhodes T, Sheon N, Page K. Policing drug users in Russia: risk, fear, and structural violence. Substance use & misuse 2010; 45(6): 813–64.

Philbin MM, Zhang F. Exploring stakeholder perceptions of facilitators and barriers to accessing methadone maintenance clinics in Yunnan Province, China. AIDS Care 2010; 22(5): 623–9.

Shahbazi M, Farnia M, Keramati M, Alasvand R. Advocacy and piloting the first needle and syringe exchange program in Iranian prisons. Retrovirology 2010; 7(Suppl 1): P81.

Pinkerton SD. Is Vancouver Canada’s supervised injection facility cost-saving? Addiction 2010; 105(8): 1429–36.

Fairbairn N, Small W, Van Borek N, Wood E, Kerr T. Social structural factors that shape assisted injecting practices among injection drug users in Vancouver, Canada: a qualitative study. Harm Reduction Journal 2010; 7: 20.

Strathdee SA, Hallett TB, Bobrova N, et al. HIV and risk environment for injecting drug users: The past, present, and future. The Lancet 2010; 376(9737): 268–84.

Bravo MJ, Royuela L, Brugal MT, Barrio G, Domingo-Salvany A. Use of supervised injection facilities and injection risk behaviours among young drug injectors. Addiction 2009; 104(4): 614–9.

Ngo AD, Schmich L, Higgs P, Fischer A. Qualitative evaluation of a peer-based needle syringe programme in Vietnam. International Journal of Drug Policy 2009; 20(2): 179–82.

Vahdani P, Hosseini-Moghaddam SM, Family A, Moheb-Dezfouli R. Prevalence of HBV, HCV, HIV, and syphilis among homeless subjects older than fifteen years in Tehran. Archives of Iranian Medicine 2009; 12(5): 483–7.

Des Jarlais DC, Arasteh K, Hagan H, McKnight C, Perlman DC, Friedman SR. Persistence and change in disparities in HIV infection among injection drug users in New York City after large-scale syringe exchange programs. American Journal of Public Health 2009; 99(Suppl 2): S445–51.

Rafiey H, Narenjiha H, Shirinbayan P, et al. Needle and syringe sharing among Iranian drug injectors. Harm Reduction Journal 2009; 6: 21.

Krüsi A, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. An integrated supervised injecting program within a care facility for HIV-positive individuals: a qualitative evaluation. AIDS Care 2009; 21(5): 638–44.

Hayashi K, Milloy MJ, Fairbairn N, et al. Incarceration experiences among a community-recruited sample of injection drug users in Bangkok, Thailand. BMC Public Health 2009; 9(1): 492-.

Small W, Wood E, Betteridge G, Montaner J, Kerr T. The impact of incarceration upon adherence to HIV treatment among HIV-positive injection drug users: a qualitative study. AIDS Care 2009; 21(6): 708–14.

Pollini RA, Alvelais J, Gallardo M, et al. The harm inside: Injection during incarceration among male injection drug users in Tijuana, Mexico. Drug & Alcohol Dependence 2009; 103(1–2): 52–8.

Suntharasamai P, Martin M, Vanichseni S, et al. Factors associated with incarceration and incident human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among injection drug users participating in an HIV vaccine trial in Bangkok, Thailand, 1999–2003. Addiction 2009; 104(2): 235–42.

Milloy MJ, Buxton J, Wood E, Li K, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Elevated HIV risk behaviour among recently incarcerated injection drug users in a Canadian setting: a longitudinal analysis. BMC Public Health 2009; 9(1): 156.

Thomson N, Sutcliffe CG, Sirirojn B, et al. Correlates of incarceration among young methamphetamine users in Chiang Mai, Thailand. American Journal of Public Health 2009; 99(7): 1232–8.

Thanh DC, Moland KM, Fylkesnes K. The context of HIV risk behaviours among HIV-positive injection drug users in Viet Nam: moving toward effective harm reduction. BMC Public Health 2009; 9: 98.

Reid G, Aitken C. Advocacy for harm reduction in China: A new era dawns. International Journal of Drug Policy 2009; 20(4): 365–70.

Sheue-Rong L, Tsuei-Mi H, Hui-Chun H, Lai-Chu S. The successful pilot harm reduction campaign in Taoyuan County. AIDS 2008 - XVII International AIDS Conference: Abstract no WEPE1080; 2008; 2008.

Schleifer R, Kaplan K, Suwannawong P. Deadly denial: barriers to HIV/AIDS treatment for people who use drugs in Thailand. Oral Abstract Session: AIDS 2008 - XVII International AIDS Conference: Abstract no TUAE0203; 2008; 2008.

Pollini RA, Brouwer KC, Lozada RM, et al. Syringe possession arrests are associated with receptive syringe sharing in two Mexico-US border cities. Addiction 2008; 103(1): 101–8.

Philbin M, Pollini RA, Ramos R, et al. Shooting gallery attendance among IDUs in Tijuana and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico: correlates, prevention opportunities, and the role of the environment. AIDS & Behavior 2008; 12(4): 552–60.

Chen CH, Ko WC, Lee HC, Hsu KL, Ko NY. Risky behaviors for HIV infection among male incarcerated injection drug users in Taiwan: A case-control study. AIDS Care 2008; 20(10): 1251–7.

Azim T, Chowdhury EI, Reza M, et al. Prevalence of infections, HIV risk behaviors and factors associated with HIV infection among male injecting drug users attending a needle/syringe exchange program in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Substance use & misuse 2008; 43(14): 2124–44.

Miller CL, Firestone M, Ramos R, et al. Injecting drug users’ experiences of policing practices in two Mexican-U.S. border cities: Public health perspectives. International Journal of Drug Policy 2008; 19(4): 324–31.

Strathdee SA, Lozada R, Pollini RA, et al. Individual, social, and environmental influences associated with HIV infection among injection drug users in Tijuana, Mexico. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes: JAIDS 2008; 47(3): 369–76.

Epperson M, El-Bassel N, Gilbert L, Orellana ER, Chang M. Increased HIV risk associated with criminal justice involvement among men on methadone. AIDS and Behavior 2008; 12(1): 51–7.

Milloy MJ, Wood E, Small W, et al. Incarceration experiences in a cohort of active injection drug users. Drug and Alcohol Review 2008; 27(6): 693–9.

Werb D, Kerr T, Small W, Li K, Montaner J, Wood E. HIV risks associated with incarceration among injection drug users: Implications for prison-based public health strategies. Journal of Public Health 2008; 30(2): 126–32.

Cohen JE, Amon JJ. Health and Human Rights Concerns of Drug Users in Detention in Guangxi Province, China. PLoS Medicine 2008; 5(12): 1682–8.

Neaigus A, Zhao M, Gyarmathy VA, Cisek L, Friedman SR, Baxter RC. Greater drug injecting risk for HIV, HBV, and HCV infection in a city where syringe exchange and pharmacy syringe distribution are illegal. Journal of Urban Health 2008; 85(3): 309–22.

Courtenay-Quirk C, Pals SL, Kidder DP, Henny K, Emshoff JG. Factors associated with incarceration history among HIV-positive persons experiencing homelessness or imminent risk of homelessness. Journal of community health 2008; 33(6): 434–43.

Werb D, Wood E, Small W, et al. Effects of police confiscation of illicit drugs and syringes among injection drug users in Vancouver. International Journal of Drug Policy 2008; 19(4): 332–8.

Tempalski B, Cooper HL, Friedman SR, Des Jarlais DC, Brady J, Gostnell K. Correlates of syringe coverage for heroin injection in 35 large metropolitan areas in the US in which heroin is the dominant injected drug. International Journal of Drug Policy 2008; 19(Suppl 1): 47–58.

Sarang A, Rhodes T, Platt L. Access to syringes in three Russian cities: Implications for syringe distribution and coverage. International Journal of Drug Policy 2008; 19(Suppl 1): S25–S36.

Shannon K, Kerr T, Allinott S, Chettiar J, Shoveller J, Tyndall MW. Social and structural violence and power relations in mitigating HIV risk of drug-using women in survival sex work. Social science & medicine 2008; 66(4): 911–21.

Raykhert I, Miskinis K, Lepshyna S, et al. HIV seroprevalence among new TB patients in the civilian and prisoner populations of Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine. Scandinavian journal of infectious diseases 2008; 40(8): 655–62.

Wood E, Tyndall MW, Zhang R, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Rate of detoxification service use and its impact among a cohort of supervised injecting facility users. Addiction 2007; 102(6): 916–9.

Rich JD, Hogan JW, Wolf F, et al. Lower syringe sharing and re-use after syringe legalization in Rhode Island. Drug & Alcohol Dependence 2007; 89(2–3): 292–7.

Rácz J, Gyarmathy VA, Neaigus A, Ujhelyi E. Injecting equipment sharing and perception of HIV and hepatitis risk among injecting drug users in Budapest. AIDS Care 2007; 19(1): 59–66.

Razani N, Mohraz M, Kheirandish P, et al. HIV risk behavior among injection drug users in Tehran, Iran. Addiction 2007; 102(9): 1472–82.

Bluthenthal RN, Ridgeway G, Schell T, Anderson R, Flynn NM, Kral AH. Examination of the association between syringe exchange program (SEP) dispensation policy and SEP client-level syringe coverage among injection drug users. Addiction 2007; 102(4): 638–46.

Dolan K, Kite B, Black E, Aceijas C, Stimson GV. HIV in prison in low-income and middle-income countries. The Lancet infectious diseases 2007; 7(1): 32–41.

Rhodes T, Platt L, Sarang A, Vlasov A, Mikhailova L, Monaghan G. Street policing, injecting drug use and harm reduction in a Russian city: a qualitative study of police perspectives. Journal of Urban Health 2006; 83(5): 911–25.

Davis WR, Johnson BD, Randolph D, Liberty HJ. Risks for HIV infection among users and sellers of crack, powder cocaine and heroin in central Harlem: implications for interventions. AIDS Care 2006; 18(2): 158–65.

Rhodes T, Platt L, Maximova S, et al. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis C and syphilis among injecting drug users in Russia: a multi-city study. Addiction 2006; 101(2): 252–66.

Small W, Kerr T, Charette J, Schechter MT, Spittal PM. Impacts of intensified police activity on injection drug users: Evidence from an ethnographic investigation. International Journal of Drug Policy 2006; 17(2): 85–95.

Tyndall MW, Wood E, Zhang R, Lai C, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. HIV seroprevalence among participants at a Supervised Injection Facility in Vancouver, Canada: implications for prevention, care and treatment. Harm Reduction Journal 2006; 3(1): 36.

Zamani S, Kihara M, Gouya MM, et al. High prevalence of HIV infection associated with incarceration among community-based injecting drug users in Tehran, Iran. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes 2006; 42(3): 342–6.

Miller CL, Strathdee SA, Kerr T, Li K, Wood E. Factors associated with early adolescent initiation into injection drug use: Implications for intervention programs. Journal of Adolescent Health 2006; 38(4): 462–4.

Sarang A, Rhodes T, Platt L, et al. Drug injecting and syringe use in the HIV risk environment of Russian penitentiary institutions: Qualitative study. Addiction 2006; 101(12): 1787–96.

Callon C, Wood E, Marsh D, Li K, Montaner J, Kerr T. Barriers and facilitators to methadone maintenance therapy use among illicit opiate injection drug users in Vancouver. Journal of Opioid Management 2006; 2(1): 35–41.

Our methodological quality assessment scores for observational quantitative studies (n=80) based on the modified Downs and Black checklist ranged from 11 to 15 with a median score of 15 of a possible 18 (appendix p 11). The most common study location was North America (n=42, 40%), followed by Asia (n=27, 25%), eastern Europe (n=12, 11%), South America (n=10, 9%), the Middle East (n=8, 8%), Europe (n=5, 5%), and Oceania (n=1, 1%), and there was one multisite study (n=1, 1%).