Abstract

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the United States. Metastasis to lymph nodes (LN) and distal organs, especially brain, leads to severe complications and death. Preventing lung cancer development and metastases is important strategy to reduce lung cancer mortality. Honokiol (HNK), a natural compound presents in extracts of magnolia bark, has a favorable bioavailability profile and recently has been shown to readily cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB). In the current study, we evaluated the anti-metastatic effects of HNK in both the LN and brain mouse models of lung tumor metastasis. We tested the efficacy of HNK in preventing H2030-BrM3 cell (brain seeking human lung tumor cells) migration to LN or brain, in orthotopic mouse model, HNK significantly decreased lung tumor growth compared to the vehicle control group. HNK also significantly reduced the incidence of lymph node metastasis and the weight of mediastinal lymph nodes; in brain metastasis model, HNK inhibits metastasis of lung cancer cells to the brain to approximately one-third of that observed in control mice. We analyzed HNK’s mechanism of action which indicated that its effect is mediated primarily by inhibiting the signal transduction and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) pathway. HNK specifically inhibits STAT3 phosphorylation irrespective of the mutation status of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and knockdown of STAT3 abrogated both the anti-proliferative and the anti-metastatic effects of HNK. These observations suggest that HNK could provide novel chemopreventive or therapeutic options for preventing both lung tumor progression and lung cancer metastasis.

Keywords: Honokiol, STAT3, Lung Cancer, Brain Metastasis, Lymph Node Metastasis

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death worldwide. Brain metastasis is one of the most intractable clinical problems associated with lung cancer and is a major cause of lung cancer mortality (1, 2). It is estimated that approximately 10% of patients possess brain metastases at the time of their lung cancer diagnosis, while 40% to 50% of patients develop brain metastasis during a typical course of lung cancer disease (2). Due to the difficulty of drug transport through the blood-brain barrier (BBB), the only available therapies to address central nervous system (CNS) metastases include whole brain/CNS irradiation or surgical resection in eligible patients with non-EGFR mutant lung cancer. Patients with EGFR mutant disease are treated with anti-EGFR agents (2). All of these therapies are purely palliative and elicit significant toxicities. Therefore, naturally occurring agents that produce little or no toxicity, and that can be delivered systemically to the original tumor site and to the brain, may prove highly efficacious for lung cancer treatment.

Honokiol (HNK) is a key bioactive compound present in extracts of magnolia bark. The extracts have been used as a folk remedy in Asian countries to treat gastrointestinal disorders, cough, anxiety, stroke, and allergic diseases for centuries. HNK has a favorable bioavailability profile in rodents with a sustained plasma concentration in mice and a two-compartment pharmacokinetic profile in rats (3, 4). Our recent study measuring oxygen consumption rate (OCR) in whole intact cells demonstrated that HNK may directly target mitochondria, leading to rapid and persistent inhibition of mitochondrial respiration. This results in the induction of apoptosis in lung cancer cells and ultimately attenuates lung squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) growth in the N-nitroso-tris-chloroethylurea (NTCU)-induced murine model of lung SCC (5). Remarkably, HNK has been shown to readily cross both the BBB (6, 7) and blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB) to inhibit brain tumor growth in rodent models (6), which prompted us to develop the hypothesis that HNK may not only inhibit lung tumorigenesis but also suppress lung cancer brain metastasis.

Several mechanisms of action have been suggested for HNK as an anti-tumor agent, including induction of apoptosis by causing mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress (8), cell cycle arrest (9), and inhibition of tumor invasion via downregulation of EGFR, NF-κB (nuclear factor of κ light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells 1), Ras/ERK (extracellular regulated kinase), PI3K/AKT (phosphoinositide 3-kinase/v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homologue) and Akt/mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) pathways (10–13). One key mechanism of action for HNK is the induction of apoptosis through a mitochondrial dependent mechanism (5, 7). We demonstrated that HNK suppresses mitochondrial respiration and increases generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in mitochondria, leading to induction of apoptosis in lung cancer cells (5). Recently, the mitochondrial proteins SIRT3 (TAp63 transactivates sirtuin 3) and Grp78 (glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) - an apoptosis-associated protein) have been suggested as possible targets of HNK. Interestingly, STAT3 is a major downstream mediator of these pathways and is also known to play a major role in regulating mitochondrial activity (14–18). STAT3 is a well-known oncogene that can be regulated by receptor tyrosine kinases, G-protein coupled receptors, and interleukin families via phosphorylation. Phosphorylated STAT3 undergoes dimerization and trans-localization in either the nucleus or mitochondria to mediate its activity resulting in enhanced cell proliferation, invasion, and survival for many cancer types (19, 20).

In the current study, we evaluated the ability of HNK to prevent lung cancer metastasis to lymph nodes and brain using well-established murine models. We also explored the potential role of receptor tyrosine kinases as targets of HNK in the inhibition of lung cancer brain metastasis. We found that a major effect of HNK is the inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation. We also determined the role of STAT3 in mediating the anti-cancer effects of HNK in lung cancer by knocking down endogenous STAT3 in the brain metastatic lung cancer cell lines (PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3). Our results showed that HNK significantly inhibits STAT3Tyr705 and STAT3Ser727 phosphorylation in both cell lines. STAT3 knockdown abrogated the anti-proliferative and anti-invasive effects of HNK. Understanding this novel mechanism of action for HNK may lead to the development of a new class of chemopreventive agents that not only inhibit lung cancer locally (5), but also have the potential to inhibit distal metastasis, which could directly benefit patients.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture and reagents

Brain metastatic lung cancer cell lines, PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3, were generously provided by Dr. Joan Massagué (Cancer Biology and Genetics Program, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY 10065, USA, not authenticated by the authors. Both cell lines were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and air. HNK was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Cell proliferation

For cell proliferation assays, cells were seeded onto 96-well tissue culture plates at 2,000–3,000 cells per well. Twenty-four hours after seeding, cells were exposed to various concentrations of HNK for 48 hr, while the control cells received medium only. The plates were incubated at 37°C and 5% CO2 and cell growth was monitored by Incucyte (Essen Bioscience, Ann Arbor, MI). Data analysis was conducted using Incucyte 2011A software. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Transwell invasion assay

Cell invasion was determined using Boyden chamber transwells that were precoated with a growth factor reduced Matrix (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Transwell invasion assays were performed as described in the manufacture’s protocol. Briefly, 3 × 105 cells were seeded into each transwell containing serum-free RPMI-1640 media and 10µM HNK. Bottom wells contained RMPI-1640 media supplemented with 10% FBS and 10µM HNK. After 36 hr, cells that had invaded through the transwell were fixed with 10% formalin, stained with 5% crystal violet in 70% ethanol, and counted in three randomly selected areas of each transwell using an inverted tissue culture microscope at 10× magnification. The results were normalized to controls.

Receptor tyrosine kinase assay

H2030-BrM3 cells, treated either with DMSO (dimethyl sulfoxide; vehicle control) or HNK at various concentrations for 6 hr, were lysed with 200 µL of 1× NP40 lysis buffer containing proteinase inhibitor cocktails (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), sheared 10 times with a 28-gauge needle, spun at 16,000 × g for 30 min, and normalized by protein concentration as determined by the Bradford method. Normalized lysate was resolved in PathScan RTK Signaling Array and the signaling array was examined by Li-COR Odyssey infrared imaging system (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE).

Western blot analysis

Cells were lysed with 200 µL of Ripa buffer containing proteinase inhibitor cocktails (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), sheared 10 times with a 28-gauge needle, spun at 16,000 × g for 30 min, normalized by protein concentration as determined by the Bradford method, and boiled for 5 min. Normalized lysate was resolved by 4%–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and immunoblotting with indicated antibodies; p-EGFR (#3777S), p-STAT3 (#9134S), p-AKT (#4060S), EGFR (4267S), STAT3 (9139S), and AKT (9272S), which were all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Actin (SC-8432) was purchased from the Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX)

Endogenous STAT3 knockdown

Lentiviral particles against STAT3 were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX). PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cells were infected with lentiviral particles using 8 µg/mL polybrene and the infected cells were selected by treatment with puromycin (2 µg/ml) for three days.

Kinome scan HNK binding assay

Direct interaction between HNK and candidate receptor tyrosine kinases was examined via the Kinome Scan binding assay from DiscoverX (San Diego, CA).

RNA-sequencing and pathway analysis

We conducted a RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) study of human lung tumor metastases in mouse brains. Three brain metastases were sampled from mice without HNK treatment and another three brain metastases were obtained from mice treated with HNK. Total RNA samples were extracted from these six samples using Qiagen RNeasy® Mini Kit. We used NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit from Illumina (San Diego, CA) to construct the RNA-seq libraries for these samples. Whole transcriptome analysis of the RNA-seq library samples was performed using HiSeq 2500 sequencing platforms (Illumina, San Diego, CA). The experiment was single-end with 50 nucleotides read length. Coverage for the samples ranged from 15 million to 32 million reads per sample. In order to identify and unequivocally separate graft (human) and host (mouse) reads, processed sample reads were sequentially aligned to both graft [complete hg19 human genome (UCSC version, February 2009)] and host [complete mm9 mouse genome (UCSC version, July 2007)] genomes using Bowtie-TopHat (21, 22). Read counts were obtained using HTseq (23). Data normalization and differential expression analysis were performed using the statistical algorithms implemented in EdgeR Bioconductor package (24). FDR (False discovery rate), corrected p-values of less than 0.05, was used as criteria for significantly regulated genes. We used a strategy that efficiently separates human lung tumor sequence data from xenograft mouse (mice with genetically human tumors) sequence data into separate microenvironment and tumor expression profiles (25, 26). Using this tool, we obtained more accurate RNA expression profiles for both metastatic human lung tumors and mouse stromal cells.

Brain metastases mouse model

Animal procedures were in accordance with the Medical College of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. For lung cancer brain metastasis study, 4- to 6-week-old female NOD.SCID (nonobese diabetic – severe combined immunodeficiency) mice were used. 2 × 105 brain-seeking H2030-BrM3 cells were suspended in 0.1 ml PBS (phosphate-buffered saline) and injected into the left ventricle under ultrasound guidance (ECHO 707, GE). One day after engrafting H2030-BrM3 cells into the arterial circulation, mice were randomly grouped into vehicle treatment group, and HNK treatment group (10 mg/kg b.w.). Mice were treated with either solvent control (0.1% DMSO in corn oil), or HNK by oral gavage for four weeks, metastasis was monitored over time by bioluminescence with an IVIS 200 Xenogen and confirmed with ex vivo luminescence, GFP fluorescence followed by H&E (hematoxylin and eosin), and GFP staining. For analysis of lung tumor lymph node metastases, H2030-BrM3 (104) cells were suspended in a 1:2 mixture of PBS and growth factor reduced Matrigel (BD Biosciences) and injected into the lung. HNK treatment was initiated one day post orthotopic injection of tumor cells by oral gavage.

In vivo lung cancer orthotopic model

We used an orthotopic model of lung adenocarcinoma cells (H2030-BrM3 cells) in athymic nude mice to evaluate the inhibitory effect of HNK on lung tumor growth and lymph node metastasis. Five-week-old male athymic nude mice were used for the experiments. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and placed in the right lateral decubitus position. A total of 1 × 106 H2030-Br3 cells in 50 µg of growth factor reduced Matrigel in 50 µL of RPMI-1640 medium were injected into the left lung through the left rib cage as previously described (27). One day after injection, mice in the HNK group were treated with 2 or 10 mg/kg b.w. HNK, once a day, five days per week for four consecutive weeks. Tumor growth and metastases phenotype was monitored over time by bioluminescence with an IVIS 200 Xenogen. Mice were euthanized at endpoint; tissues were immediately fixed in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) and frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent Western blot and immunohistochemical analyses.

In vivo imaging system (IVIS)

IVIS consists of a highly sensitive, charge-coupled digital camera with accompanying advanced computer software for image data acquisition and analysis. This system captures photons of light emitted by reagents or cells that have been coupled or engineered to produce bioluminescence in the living animal. The substrate luciferin was injected into the intraperitoneal cavity of mice at a dose of 150 mg/kg b.w. (30 mg/ml luciferin), approximately 10 min before imaging. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane/oxygen and placed on an imaging stage. Photons emitted from the lung region were quantified using Living Image software (Xenogen Corp., Alameda, CA).

Histopathology

Mouse brains were fixed in 10% zinc formalin solution overnight and stored in 70% ethanol for histopathology. Serial tissue sections (5-µm each) were made and stained with H&E or GFP, and examined histologically under a light microscope to assess severity of tumor development.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. *P < 0.05, ** P<0.005 and *** P<0.0005 were considered statistically significant.

Results

HNK inhibits proliferation and invasion of brain metastatic lung cancer cells in vitro

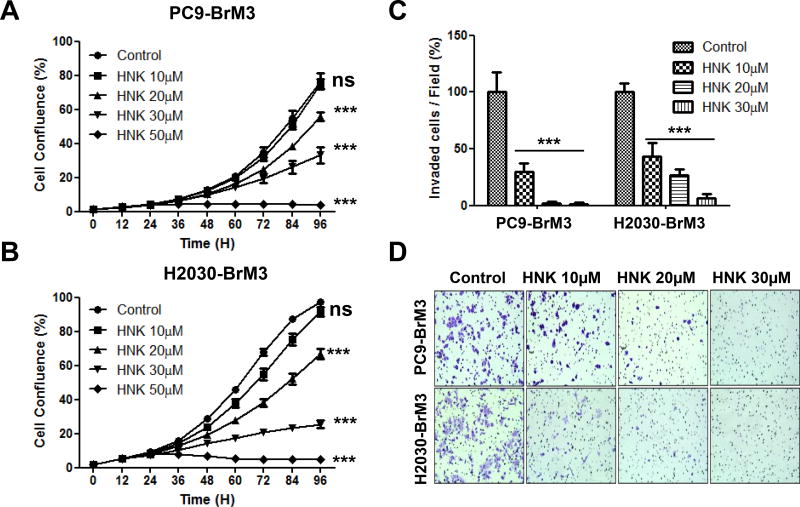

Previous research in our laboratory and in other laboratories demonstrated the anti-cancer effect of HNK in many cancer types including lung (4, 5, 9, 11, 12, 28). To evaluate the effects of HNK in brain metastatic lung cancer, we examined the effects of honokiol on the proliferation and invasion of PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 brain metastatic lung cancer cells. Initially, PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cells were treated with various concentrations of HNK for 96 hr to examine the anti-proliferative effects of the compound. HNK effectively inhibited both PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cell proliferation in a dose- and time-dependent manner (IC50 for PC9-BrM3 is 28.4 µM, for H2030-BrM3 is 25.7 µM; Fig. 1A). We also examined the effects of HNK on the invasion of PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cells in the Boyden Chamber (Fig. 1C–D). As shown in Figure 1C–D, HNK significantly inhibited the invasion of both PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cell lines in a dose-dependent manner. The doses of HNK required to reduce the invasion of PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cells were much lower (Fig. 1C–D) than those required to inhibit cell proliferation (Fig. 1A–B). Based on previous research (5–7, 29–31) and our present data, HNK is not only an effective chemopreventive/chemotherapeutic agent, but could also be an effective agent to prevent or inhibit invasion of lung cancer.

Figure 1. Effects of HNK on lung cancer cell proliferation and invasion.

(A–B) PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 lung cancer cell lines were treated with HNK (0, 10, 20, 30, 50 µM) for 96 hr. Cell proliferation was measured using the Incucyte Live Imaging System as indicated in Materials and Methods. HNK inhibited proliferation of PC-9BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. PC9-BrM3 (IC50=28.4µM) and H2030-BrM3 (IC50=25.7µM) (*p<0.05, **p<0.005). (C) HNK significantly inhibited invasion of PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cells even at the lowest dose of 10µM when compared to PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cells treated with the vehicle control DMSO (*p<0.05, **p<0.005). Number of invaded cells per field (%) was normalized to the DMSO control group. (D) Representative images of invaded PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cells in the absence and presence of HNK. Invasion of both PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cells was inhibited by HNK in a dose-dependent manner.

HNK inhibits metastasis of lung tumor cells to lymph nodes in a lung orthotopic mouse model

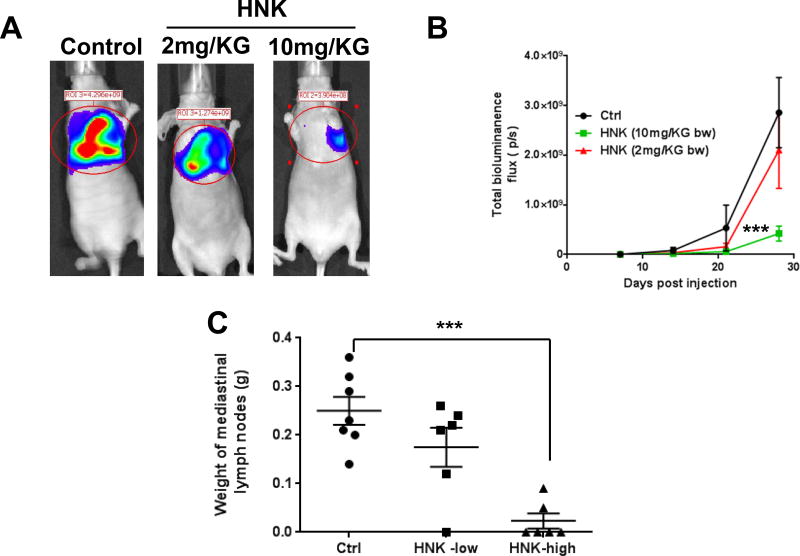

In the mice implanted orthotopically with H2030-BrM3 cells in the left lung, lung tumors grew and spread within the lung and then to the mediastinum. The incidence of tumor formation was 100%. Representative bioluminescence images of lung orthotopic xenografts are shown in Fig. 2A. Mice didn’t show any observable side effect when treated with HNK. Higher doses of HNK significantly decreased lung tumor growth when compared to the vehicle control group (Fig. 2B). Comparing with control group, HNK, at the higher dose (10 mg/kg b.w.), significantly reduced the incidence of mediastinal adenopathy. The incidence of mediastinal lymph node metastasis in the control group is 100%, in the high-dose HNK treatment group, only two of six mice have lymphatic metastasis. The high-dose HNK also significantly decreased the weight of mediastinal lymph nodes over 80% compared with control group (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. HNK inhibits orthotopic lung tumor growth in mice injected with H2030-BrM3 cells.

(A) Representative luciferase images from mice treated with either gavage control (Ctrl) or HNK. (B) Quantification of bioluminescence imaging signal intensity in the control (Ctrl) and HNK-treated groups at different time points after injection of H2030-BrM3 cells. Quantified values are shown in total flux. (C). The weight of the mediastinal lymph nodes was significantly lower compared with the no-treatment controls. The incidence of lymphatic metastasis was significantly lower in the high-dose HNK treatment group (2 of 6) compared with that of the no-treatment controls (7 of 7). ***p<0.0005.

HNK inhibits metastasis of lung cancer cells to the brain in vivo

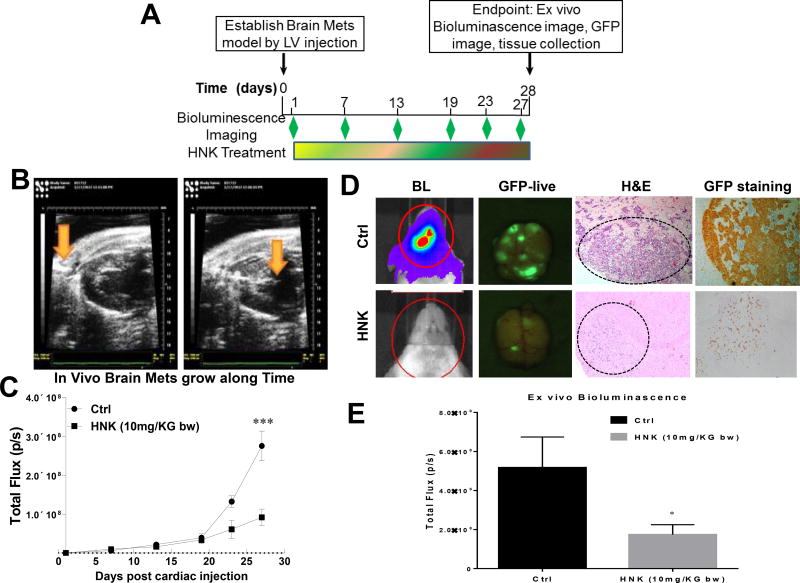

In this assay, we used an ultrasound-guided procedure to insure the injection of brain-seeking H2030-BrM3 lung cancer cells into the left ventricle (LV) of NOD/SCID mice (Fig. 3A). One day after cell inoculation, the mice were randomly grouped to vehicle control and HNK low- (2 mg/kg b.w.) and high-dose (10 mg/kg b.w.) groups. High-dose HNK significantly decreased brain metastasis over 70% when compared to the vehicle control group (Fig. 3B). At necropsy (28 days post-LV injection), the extent of brain metastases was also quantified by ex vivo bioluminescence and GFP imaging as shown in Fig. 3C. HNK treatment decreased brain metastasis to approximately one-third of that observed in control mice. Lung tumor cells migration to brain was confirmed by H&E staining, as well as GFP staining (Fig. 3D–E). Collectively, our data suggest that HNK could be effective in preventing the metastasis of lung cancer cells to the brain.

Figure 3. HNK inhibits lung cancer brain metastasis.

(A) H2030-BrM3 cells expressing GFP and luciferase were engrafted in the arterial circulation by an ultrasound-guided left ventricle injection. Brain metastasis was detected by bioluminescence at different time points with an IVIS 200 Xenogenmonitor (Xenogen, Alameda, CA; exposure time 1 min; binning 8; no filter; f/stop16; field of view [FOV] 12.5 cm). (B) Corresponding grayscale photographs and color luciferase images are superimposed and analyzed with LivingImage (Xenogen). Data is expressed as normalized photon flux (photons/s/cm2). After final IVIS scan, mouse brain was dissected and imaged using Maestro™ Multi-Spectral Imaging System for GFP signal. (C). Quantification of bioluminescence imaging signal intensity in the control (Ctrl) and HNK-treated groups at different time points after injection of H2030-BrM3 cells. Quantified values are shown in total flux. (D). Representative luciferase, GFP and H&E IHC images from mice treated with either gavage control (Ctrl) or HNK. *p<0.05, ***p<0.0005.

STAT3 as a potential target of HNK in the inhibition of lung cancer brain metastasis

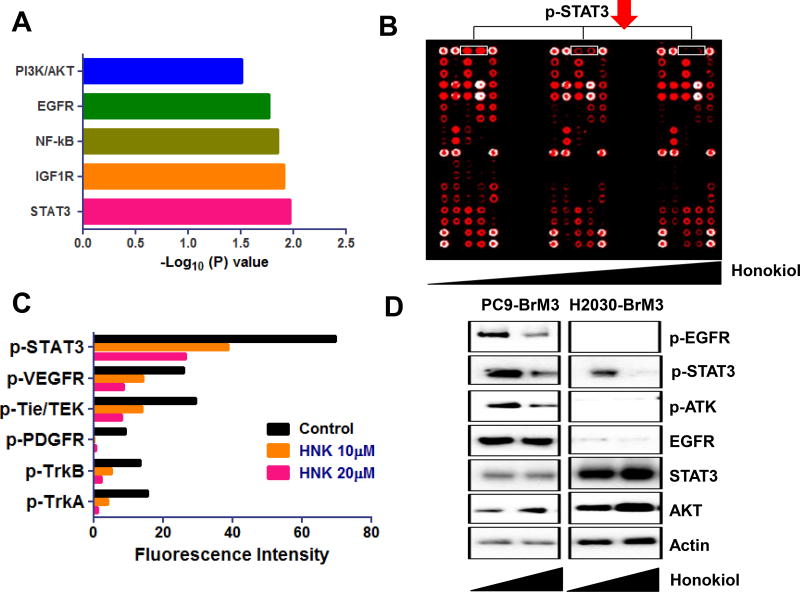

Potential mechanisms of action of HNK in the inhibition of lung cancer cell brain metastasis were examined via receptor tyrosine kinase assays (Fig. 4A) H2030-BrM3 cells were treated with 10 and 20 µM HNK for 6 hr. PathScan RTK signaling array revealed that HNK treatment dramatically decreased STAT3 phosphorylation (Fig. 4A–B), suggesting that STAT3 is at least one molecular target of HNK (Fig. 4A–B). The effects of HNK on STAT3 phosphorylation in PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cells were confirmed by Western blot analysis (Fig. 4B). Previously, HNK was found to be effective in the treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) via targeting the EGFR signaling pathway (32). In the current study, we also observed that HNK targets the EGFR-AKT signaling pathway in PC9-BrM3 cells which harbor an EGFR mutation, but not in H2030-BrM3 cells which harbor Kras mutations. In addition, we examined the interaction between HNK and multiple receptor tyrosine kinases via the KinomeScan binding assay. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S1, HNK did not bind directly to any of the receptor tyrosine kinases tested.

Figure 4. HNK targets STAT3 phosphorylation via inhibition of multiple receptor tyrosine kinases.

(A). Pathway analysis based on RNA-seq revealed that HNK inhibits multiple receptor tyrosine kinase pathways including EGFR, as well as the IGF1R and NF-kB, PI3K/AKT and STAT3 signaling pathway. Notably, STAT3 signaling pathway was the most significantly affected pathways by HNK. (B) H2030-BrM3 cells were treated with HNK and cell lysates were examined using RTK signaling arrays. STAT3 phosphorylation is downregulated by HNK in a dose-dependent manner. (C) Effects of HNK on the phosphorylation of STAT3, as well as other signaling pathways such as TrkA/B, PDGFR, Tie/TEK, and VEGFR signaling pathways. (D) The phosphorylation of EGFR and AKT is downregulated by HNK only in the EGFR mutant PC9-BrM3 cell line, but not in the Kras mutant H2030-BrM3 cell line. STAT3 phosphorylation is down-regulated by HNK in both cell lines.

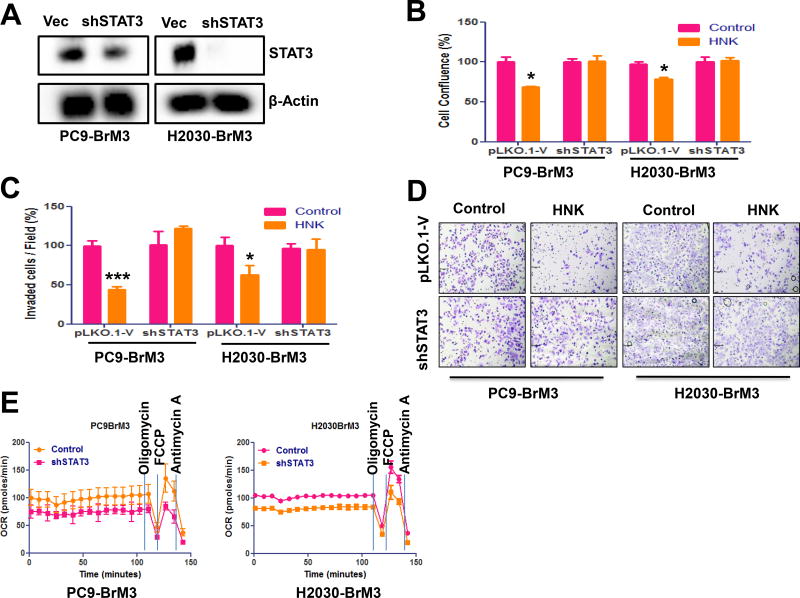

STAT3 knockdown decreases anti-cancer effects of HNK in lung cancers

ShRNA knockdown was used to demonstrate the role of STAT3 in mediating the effects of HNK in lung cancer. Knockdown of STAT3 in PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cells was validated by Western blot analysis (Fig. 5A). STAT3 knockdown decreases the anti-proliferative (Fig. 5B) and anti-invasive (Fig. 5C–D) effects of HNK in both PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cell lines. HNK treatment (20 µM) for 48 hr inhibited proliferation of PC9-BrM3 vector control cells by 30% and H2030-BrM3 vector control cells by 20% but had no significant effect on proliferation of STAT3 knockdown PC9-BrM3 or H2030-BrM3 cells (Fig. 5B). In addition, HNK treatment (10µM) significantly inhibited invasion of both PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 vector control cells but had no effect on invasion of STAT3 knockdown PC9-BrM3 or H2030-BrM3 cells (Fig. 5C–D). Lastly, we examined the effects of STAT3 on mitochondrial respiratory function in PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cells. As shown in Fig. 5F, STAT3 knockdown significantly decreased mitochondrial respiratory function in both PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cell lines. The anti-cancer effects of HNK, therefore, could be through inhibition of STAT3-mediated mitochondrial functions in lung cancer cells that have metastasized to the brain.

Figure 5. STAT3 knockdown abrogates the anti-proliferative, anti-migratory, and anti-invasive effects of HNK.

(A) Efficiency of STAT3 knockdown via shRNA approach in PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 was determined via western blot. The role of STAT3 in the mediating the anti-proliferative and anti-invasive effects was determined as indicated in material and methods. STAT3 knockdown abrogates the anti-proliferative (B) and anti-invasive (C) effects of HNK in PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cell lines. (D) Effects of STAT3 in mitochondria respiratory function was examined via Seahorse experiment. STAT3 knockdown decreases the mitochondria respiratory function in both PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cells. (E) Representative images of PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 control vector transfected and STAT3 knockdown cells with/without treatment of HNK from invasion assay.

RNA-seq analysis showed that the expressions of key genes important to the activation of STAT3 pathway were downregulated in the metastatic lung tumors by HNK treatment

The differentially expressed genes identified by RNA-seq analysis software were subjected to IPA analysis (Ingenuity Pathway Analysis, http://www.ingenuity.com/products/ipa) to identify the most significant oncogenic pathways in metastatic lung tumors changed by HNK treatment. Our genome-wide RNA-seq scan showed that STAT3 pathway is the top downregulated one among the oncogenic pathways that were significantly down-regulated in the HNK-treated human lung tumor metastases in mouse brains (Fig. 4A). In addition, RNA-seq analyses identified that six key genes involved in the activation of STAT3 pathways were significantly down-regulated in metastatic lung tumors in vivo upon HNK treatment (Table 1). They were FGFR4, IGF1R, IGF2R, MAP2K1, MAP3K11, and SRC. These matched the findings from our functional studies and supported that the anti-lung-cancer role of HNK was mediated via the STAT3 signaling pathway.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 6 key genes in the STAT3 pathway that was down-regulated in the HNK-treated human lung tumor metastases in mouse brains.

| Symbol | Entrez Gene Name | Fold change (HNK vs Non-HNK Mets) |

FDR value | Location | Type(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGFR4 | fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 | −18.5 | 0.040 | Plasma Membrane | kinase |

| IGF1R | insulin like growth factor 1 receptor | −2.3 | 0.022 | Plasma Membrane | transmembrane receptor |

| IGF2R | insulin like growth factor 2 receptor | −1.6 | 0.012 | Plasma Membrane | transmembrane receptor |

| MAP2K1 | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1 | −1.7 | 0.011 | Cytoplasm | kinase |

| MAP3K1 | mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 11 | −1.8 | 0.011 | Cytoplasm | kinase |

| SRC | SRC proto-oncogene, non-receptor tyrosine kinase | −2.0 | 0.003 | Cytoplasm | kinase |

Discussion

One of the common sites for metastases of lung cancers is the brain. Current available therapies to address CNS metastases include whole brain/CNS irradiation or surgical resection in eligible patients, treatment with anti-EGFR agents in patients whose tumors contain EGFR mutations, as well as using next-Generation ALK TKIs that is brain-penetrable such as PF-06463922, to control CNS metastases in lung cancer patients (2, 33). However, these treatment options are available only after the diagnoses of brain metastases and in many cases, metastatic lesions remain undiagnosed for long periods or they are not amenable to treatment with chemo/radiotherapy or surgery. Therefore, it is necessary to develop prevention strategies to inhibit metastases from primary tumors. Recently, we demonstrated the ability of HNK to potently inhibit the development of lung tumors in mice (5). Analysis of HNK’s mechanism of action suggests that its effect is primarily mediated by inducing apoptosis through a mitochondria-dependent mechanism (5, 7, 34). Here, through the use of the well-characterized brain metastases murine model, we report that HNK exerts inhibitory effects on the metastasis of lung cancer cells to the brain indicating that the compound has chemopreventive potential against both primary lung tumors and on metastasis of lung cancer to the brain.

Direct injection of tumor cells into the left ventricle is the most widely used brain metastases model in rodents because it bypasses the pre-colonization steps of dissemination of cancer cells through the bloodstream, homing and extravasation, and recapitulates the process of cancer cells crossing the BBB and growing within the brain microenvironment. Metastatic brain lesions in mice vary from round, circumscribed lesions typical of that seen on human scans, to infiltrative tumor cells which over time form typical round lesions that are ideal for evaluating the preventative effect of HNK on lung cancer metastasis. The brain homing H2030 and PC9 lung cancer cell lines were developed to have 100% brain-metastatic potential (5–7, 29–31), H2030 cells with a KRASG12C mutation (35) and PC9 cell with an EGFRΔexon19 mutation (36). These cell lines were engineered to stably express GFP-luciferase fusion for real-time monitoring of metastatic tumor growth. In the present study, we monitored metastatic tumor growth using both live animal imaging and endpoint ex vivo imaging. We also validated tumor growth by staining the brain tissues with H&E and GFP, and both stains consistently demonstrated about a 70% inhibition of brain metastases by HNK.

At least one of the mechanisms through which HNK inhibited lung cancer cell metastasis to the brain was through inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation. HNK is known to target multiple signaling pathways including EGFR, MAPK, and PI3K/AKT (10–13). Recently, Sirt3 and GRP78 were also suggested as potential binding targets of HNK in different tissue types (34, 37). Interestingly, STAT3 is a major downstream mediator of multiple receptor tyrosine kinases pathways (14–17). Our data suggest that STAT3 could be a universal downstream target of HNK treatment. As indicated before, HNK was effective in the treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) via targeting the EGFR signaling pathway (38). The brain homing H2030 and PC9 lung cancer cell lines carry different driver mutations, H2030 with a KRASG12C mutation (35) and PC9 with an EGFRΔexon19 mutation (36). In PC9-BrM3 cells, we observed downregulation of phosphorylated EGFR by HNK, but not in H2030-BrM3 cells which do not carry an EGFR mutation. Therefore, the effects of HNK on the EGFR-AKT signaling pathway could be cell-type- or tissue-specific. RNA-seq data suggest that FGFR4 is the most significant gene that was affected by HNK treatment and FGFR4 is known to mediate STAT3 signaling pathway (39). Therefore, it will be interesting to investigate the role of FGFR4-STAT3 signaling pathway in mediating anti-cancer effects of HNK. STAT3 phosphorylation was reduced in both PC9-BrM3 and H2030BrM lung cancer cell lines by HNK, and knockdown of endogenous STAT3 in these cell lines abrogated the anti-proliferative, anti-migratory, and anti-invasive effects of HNK, further supporting the concept that STAT3 could be a universal downstream target of HNK regardless of EGFR mutation status of lung cancer cells. Although, with prolonged treatment honokiol will eventually inhibit proliferation of STAT3 knockdown cells (data not shown), which most likely would be due to the off-target effects of honokiol, considering it’s a polyphenol compound, once its main target has been blocked, it may target other pathways to inhibit tumor growth. STAT3 knocked down PC9-BrM3 and H2030-BrM3 cells exhibit significantly less mitochondrial respiratory function than normal lung cells. HNK inhibition of lung cancer progression via inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory function could, therefore, be due to inhibition of STAT3 phosphorylation which, in turn, leads to inhibition of the metastases of lung cancer cells to the brain.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. John Auchampach for his contribution, especially for the guidance of the left ventricle under ECHO 707.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by any of the authors

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg SB, Contessa JN, Omay SB, Chiang V. Lung Cancer Brain Metastases. Cancer J. 2015;21:398–403. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0000000000000146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai TH, Chou CJ, Cheng FC, Chen CF. Pharmacokinetics of honokiol after intravenous administration in rats assessed using high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr B Biomed Appl. 1994;655:41–5. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(94)00031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen F, Wang T, Wu YF, Gu Y, Xu XL, Zheng S, et al. Honokiol: a potent chemotherapy candidate for human colorectal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3459–63. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i23.3459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan J, Zhang Q, Liu Q, Komas SM, Kalyanaraman B, Lubet RA, et al. Honokiol inhibits lung tumorigenesis through inhibition of mitochondrial function. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014;7:1149–59. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang X, Duan X, Yang G, Zhang X, Deng L, Zheng H, et al. Honokiol crosses BBB and BCSFB, and inhibits brain tumor growth in rat 9L intracerebral gliosarcoma model and human U251 xenograft glioma model. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18490. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin JW, Chen JT, Hong CY, Lin YL, Wang KT, Yao CJ, et al. Honokiol traverses the blood-brain barrier and induces apoptosis of neuroblastoma cells via an intrinsic bax-mitochondrion-cytochrome c-caspase protease pathway. Neuro Oncol. 2012;14:302–14. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen YJ, Wu CL, Liu JF, Fong YC, Hsu SF, Li TM, et al. Honokiol induces cell apoptosis in human chondrosarcoma cells through mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cancer Lett. 2010;291:20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hahm ER, Singh SV. Honokiol causes G0–G1 phase cell cycle arrest in human prostate cancer cells in association with suppression of retinoblastoma protein level/phosphorylation and inhibition of E2F1 transcriptional activity. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2686–95. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia A, Zheng Y, Zhao C, Toschi A, Fan J, Shraibman N, et al. Honokiol suppresses survival signals mediated by Ras-dependent phospholipase D activity in human cancer cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4267–74. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crane C, Panner A, Pieper RO, Arbiser J, Parsa AT. Honokiol-mediated inhibition of PI3K/mTOR pathway: a potential strategy to overcome immunoresistance in glioma, breast, and prostate carcinoma without impacting T cell function. J Immunother. 2009;32:585–92. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181a8efe6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tse AK, Wan CK, Shen XL, Yang M, Fong WF. Honokiol inhibits TNF-alpha-stimulated NF-kappaB activation and NF-kappaB-regulated gene expression through suppression of IKK activation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;70:1443–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng J, Qian Y, Geng L, Chen J, Wang X, Xie H, et al. Involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in honokiol-induced apoptosis in a human hepatoma cell line (hepG2) Liver Int. 2008;28:1458–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu J, Patmore DM, Jousma E, Eaves DW, Breving K, Patel AV, et al. EGFR-STAT3 signaling promotes formation of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Oncogene. 2014;33:173–80. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.De Simone V, Franze E, Ronchetti G, Colantoni A, Fantini MC, Di Fusco D, et al. Th17-type cytokines, IL-6 and TNF-alpha synergistically activate STAT3 and NF-kB to promote colorectal cancer cell growth. Oncogene. 2015;34:3493–503. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou J, Wulfkuhle J, Zhang H, Gu P, Yang Y, Deng J, et al. Activation of the PTEN/mTOR/STAT3 pathway in breast cancer stem-like cells is required for viability and maintenance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16158–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702596104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yau CY, Wheeler JJ, Sutton KL, Hedley DW. Inhibition of integrin-linked kinase by a selective small molecule inhibitor, QLT0254, inhibits the PI3K/PKB/mTOR, Stat3, and FKHR pathways and tumor growth, and enhances gemcitabine-induced apoptosis in human orthotopic primary pancreatic cancer xenografts. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1497–504. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Q, Raje V, Yakovlev VA, Yacoub A, Szczepanek K, Meier J, et al. Mitochondrial localized Stat3 promotes breast cancer growth via phosphorylation of serine 727. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:31280–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.505057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin L, Liu A, Peng Z, Lin HJ, Li PK, Li C, et al. STAT3 is necessary for proliferation and survival in colon cancer-initiating cells. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7226–37. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang H, Yamazaki T, Pietrocola F, Zhou H, Zitvogel L, Ma Y, et al. STAT3 Inhibition Enhances the Therapeutic Efficacy of Immunogenic Chemotherapy by Stimulating Type 1 Interferon Production by Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2015;75:3812–22. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–11. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Anders S, Pyl PT, Huber W. HTSeq--a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:166–9. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradford JR, Farren M, Powell SJ, Runswick S, Weston SL, Brown H, et al. RNA-Seq Differentiates Tumour and Host mRNA Expression Changes Induced by Treatment of Human Tumour Xenografts with the VEGFR Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor Cediranib. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossello FJ, Tothill RW, Britt K, Marini KD, Falzon J, Thomas DM, et al. Next-generation sequence analysis of cancer xenograft models. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen DX, Chiang AC, Zhang XH, Kim JY, Kris MG, Ladanyi M, et al. WNT/TCF signaling through LEF1 and HOXB9 mediates lung adenocarcinoma metastasis. Cell. 2009;138:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arora S, Singh S, Piazza GA, Contreras CM, Panyam J, Singh AP. Honokiol: a novel natural agent for cancer prevention and therapy. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12:1244–52. doi: 10.2174/156652412803833508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arora S, Bhardwaj A, Srivastava SK, Singh S, McClellan S, Wang B, et al. Honokiol arrests cell cycle, induces apoptosis, and potentiates the cytotoxic effect of gemcitabine in human pancreatic cancer cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21573. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagalingam A, Arbiser JL, Bonner MY, Saxena NK, Sharma D. Honokiol activates AMP-activated protein kinase in breast cancer cells via an LKB1-dependent pathway and inhibits breast carcinogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R35. doi: 10.1186/bcr3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Singh T, Katiyar SK. Honokiol inhibits non-small cell lung cancer cell migration by targeting PGE(2)-mediated activation of beta-catenin signaling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park EJ, Min HY, Chung HJ, Hong JY, Kang YJ, Hung TM, et al. Down-regulation of c-Src/EGFR-mediated signaling activation is involved in the honokiol-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;277:133–40. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Awad MM, Shaw AT. ALK inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer: crizotinib and beyond. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2014;12:429–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin S, Lamb HK, Brady C, Lefkove B, Bonner MY, Thompson P, et al. Inducing apoptosis of cancer cells using small-molecule plant compounds that bind to GRP78. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:433–43. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Phelps RM, Johnson BE, Ihde DC, Gazdar AF, Carbone DP, McClintock PR, et al. NCI-Navy Medical Oncology Branch cell line data base. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1996;24:32–91. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240630505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koizumi F, Shimoyama T, Taguchi F, Saijo N, Nishio K. Establishment of a human non-small cell lung cancer cell line resistant to gefitinib. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:36–44. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pillai VB, Samant S, Sundaresan NR, Raghuraman H, Kim G, Bonner MY, et al. Honokiol blocks and reverses cardiac hypertrophy in mice by activating mitochondrial Sirt3. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6656. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh T, Gupta NA, Xu S, Prasad R, Velu SE, Katiyar SK. Honokiol inhibits the growth of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma by targeting epidermal growth factor receptor. Oncotarget. 2015;6:21268–82. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.4178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tateno T, Asa SL, Zheng L, Mayr T, Ullrich A, Ezzat S. The FGFR4-G388R polymorphism promotes mitochondrial STAT3 serine phosphorylation to facilitate pituitary growth hormone cell tumorigenesis. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002400. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.