SUMMARY

Barrett's esophagus (BE) is the only known precursor to esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). Based on striking aggregation of breast cancer and BE/EAC within families as well as shared risk factors and molecular mechanisms of carcinogenesis, we hypothesized that BE may be associated with breast cancer. Pedigree analysis of families identified prospectively at multiple academic centers as part of the Familial Barrett's Esophagus Consortium (FBEC) was reviewed and families with aggregation of BE/EAC and breast cancer are reported. Additionally, using a matched case-control study design, we compared newly diagnosed BE cases in Caucasian females with breast cancer (cases) to Caucasian females without breast cancer (controls) who had undergone upper endoscopy (EGD). Two familial pedigrees, meeting a stringent inclusion criterion, manifested familial aggregation of BE/EAC and breast cancer in an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance. From January 2008 to October 2016, 2812 breast cancer patient charts were identified, of which 213 were Caucasian females who underwent EGD. Six of 213 (2.82%) patients with breast cancer had pathology-confirmed BE, compared to 1 of 241 (0.41%) controls (P-value < 0.05). Selected families with BE/EAC show segregation of breast cancer. A breast cancer diagnosis is marginally associated with BE. We postulate a common susceptibility between BE/EAC and breast cancer.

Keywords: breast cancer, Barrett's esophagus, cancer epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Barrett's esophagus (BE) is the primary risk factor and only known precursor of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), a highly mortal malignancy which now accounts for the majority of esophageal carcinomas in the United States.1,2 Endoscopic screening and surveillance of BE improve survival by identifying Barrett's epithelium and EAC at an earlier, potentially curable stage.3–6 Identification of risk factors for BE and/or EAC can improve the yield of screening and surveillance endoscopy. Therefore, intensive investigations are directed toward identification of factors associated with BE/EAC.

Studies have suggested several common risk factors for breast cancer and BE/EAC including age,7–9 diet,10–16 obesity,17–19 metabolic syndrome,20–22 and breast feeding history.23,24 Additionally, aspirin/NSAID use,25–27 and statin use26,28,29 have been suggested to reduce the risk of breast cancer as well as BE/EAC.

A family history of BE or EAC can inform both the screening for BE and, potentially, the complex interaction of environment and genetics in the development of Barrett's epithelium.30,31 Case-control studies of both U.S. and European cohorts demonstrate a younger age of EAC diagnosis in persons with first or second degree relative with BE or EAC.32,33 Furthermore, in a prospective study the first degree relatives of patients with suspected familial clustering of BE and EAC had a higher incidence of Barrett's epithelium on screening endoscopy, consistent with familial aggregation of BE and EAC in a subset of cases.34

To enable genetic studies, we have been collecting information on familial cases of BE/EAC as part of the Familial Barrett's Esophagus Consortium (FBEC). Segregation analyses provide evidence that the familial aggregation of BE/EAC has a genetic basis.35 During the course of these studies, we have identified some striking families that show BE/EAC predominantly in men and breast cancer in women and we wish to report a series of such families. These findings suggest possible common genetic or environmental susceptibility factors that manifest as BE/EAC in men and breast cancer in women. In order to extend our anecdotal observations of an association of breast cancer with familial BE/EAC to sporadic cases of BE/EAC, we initiated a single-centered, matched case-control study in breast cancer patients to determine if breast cancer was associated with BE.

METHODS

This is a multimethodology research study comprising of two parts: (1) Pedigree analysis of striking families showing familial aggregation of BE/EAC and breast cancer and (2) A case-control study to evaluate the association of breast cancer with BE/EAC. The research studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board at University Hospitals Cleveland Medical Center (UHCMC).

Familial BE/EAC

Families were recruited at eight tertiary care academic hospitals in the United States as part of the FBEC, an institutional review board-approved study, as previously described.34 Briefly, recruitment of family members was done through proband-initiated contact. Information on affected family members was obtained from a self-administered questionnaire. Familial Barrett's esophagus was defined as BE and/or EAC in the proband and one or more other family members (either first-degree or second-degree relatives). The reported diagnoses for families included in this study were confirmed with chart review and requests for copies of original records. Families with unconfirmed reported data were excluded from further analysis.

Breast cancer cases and matched controls

Female breast cancer patients were identified through a single-center cancer registry at UHCMC. Inclusion criteria consisted of all Caucasian females between the ages of 30 to 79 years of age who were diagnosed with any stage of breast cancer between January 1, 2008 and March 30, 2014 and received care at UHCMC or its satellite sites. Male patients, pregnant patients, and incarcerated patients were excluded. Due to the study design, breast cancer patients who did not receive care at UHCMC or its satellite sites, patients who were younger than 30 or older than 79, and patients who were diagnosed prior to 2008 or after March 2014 were excluded. Patients undergoing endoscopy for BE/EAC surveillance were also excluded. African American patients were excluded because of the low incidence of BE in this group (no cases of BE were identified in the breast cancer registry among 77 African American and 2 East Asian women in our breast cancer registry). Control patients were hospital outpatients without breast cancer and were identified from the UHCMC endoscopy database and case-matched for age ±5 years, gender, race, and timing of endoscopy (within 2 weeks).

Patient charts were divided among four investigators (MQC, AEB, AKC, and YS). Using the electronic medical record, we identified variables such as receipt of EGD, date of diagnosis of breast cancer, type and stage of breast cancer, breast cancer receptor status, receipt of chemotherapy, radiation or hormonal therapy, and whether or not surgery was pursued for breast cancer patients. Dates of endoscopy and endoscopy findings were documented for both cases and controls. If BE was found and confirmed by pathology, the maximum length of BE, highest grade of dysplasia, and if EAC was diagnosed were noted. Risk factors such as history of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), smoking history, BMI, personal history of other cancers, and family history of cancers were identified for both cases and controls. All data were reviewed prior to statistical analysis to minimize discrepancies. Based on the a priori hypothesis that BE is associated with breast cancer, significance was concluded based on a Fisher's exact test, with a one-sided significance level of 0.05.

RESULTS

Results of the pedigree analysis

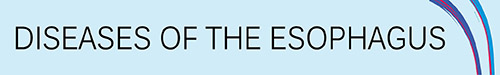

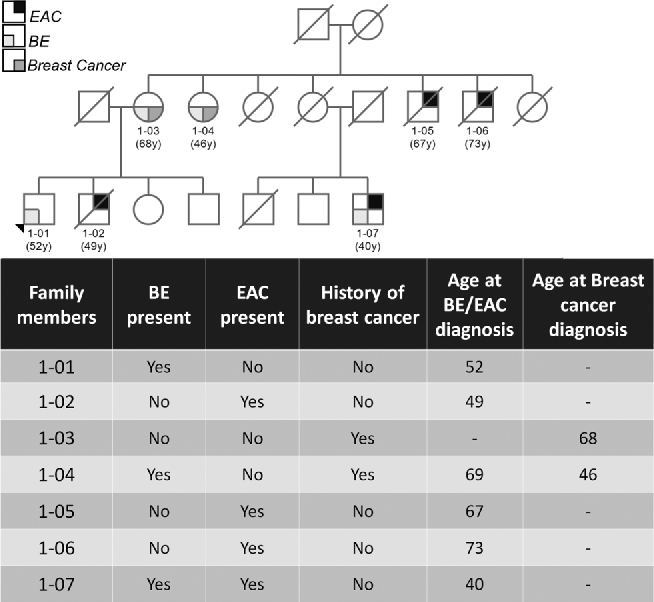

Seventy-four (74) families with an aggregation of BE/EAC were reviewed and 12 families were found to have at least two affected members having pathology-confirmed breast cancer. Two families had confirmation of BE/EAC and breast cancer by pathology report for all affected members. The two families demonstrated an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance. For Family 1, the proband has long segment BE and his brother, two maternal uncles, and first cousin have EAC. The proband's mother and maternal aunt have breast cancer and short segment BE (Fig. 1). Genetic testing for BRCA mutations was not available. For Family 2, the proband and a male first cousin were found to have EAC and the proband's daughter, sister, and sister's daughter were found to have breast cancer at relatively early ages (Fig. 2). The proband's daughter and niece both were found to be negative for BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 mutations (BRCA1 185delAG, BRCA1 5382insC, BRCA2 6174delT).

Fig. 1.

A partial family pedigree of Family 1.

Fig. 2.

A partial family pedigree of Family 2.

Results of the case-control study

From January 2008 to October 2016, 2812 female breast cancer patients were identified through a single-center cancer registry. Of these, 213 Caucasian patients with breast cancer had undergone EGD and 241 controls matching for age, gender, race, and timing of endoscopy were identified. There was no difference in the baseline characteristics between the two study groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of baseline characteristics in study groups

| Cases (n = 213) | Controls (n = 241) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean [SD]) | 67.4 (10.6) | 67.2 (10.6) | 0.86 |

| BMI (mean [SD]) | 29.1 (6.6) | 28.2 (6.9) | 0.23 |

| GERD | 136 (47.6%) | 150 (52.4%) | 0.41 |

| PPI use | 153 (45.8%) | 181 (54.2%) | 0.13 |

| Smoking hx | 109 (50.5%) | 107 (49.5%) | 0.89 |

| Hx of chemotherapy | 165 (80.1%) | – | – |

| Hx of radiation | 135 (66.2%) | – | – |

| Hx of surgery | 195 (94.2%) | – | – |

To determine whether a history of breast cancer is associated with BE, the proportion of newly diagnosed BE in patients with breast cancer was compared to patients without breast cancer. The patients with breast cancer had a higher proportion of newly diagnosed BE than the control group (6 BE among breast cancer cases vs. 1 BE among controls; one-sided P = 0.043, two-sided P = 0.055) (Table 2).

Table 2.

BE Incidence among cases and controls

| Breast cancer+ | Breast cancer− | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BE+ | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| BE− | 207 | 240 | 447 |

| Total | 213 | 241 | 454 |

Two tailed P = 0.055, One tailed P = 0.043, Fisher's exact test.

Among the 6 breast cancer patients diagnosed with BE, 3 were diagnosed with BE prior to their diagnosis of breast cancer, 2 had a history of smoking, 1 had short segment BE, and all 6 had a history of GERD. All of the breast cancer identified in the 6 cases were estrogen receptor (ER) positive, 5 were progesterone receptor (PR) positive, and one was human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) positive (Table 3).

Table 3.

Individual characteristics of patients with nondysplastic BE

| Breast cancer type | Max length of BE† | BE dx after breast cancer | Hx of GERD | Hx of Smoking | BMI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Poorly differentiated, ER/PR/Her2+ | SSBE | No | Yes | Yes | 31.6 |

| Case 2 | Mixed ductal and lobular, ER/PR+ | 3 cm | Yes | Yes | No | 39.0 |

| Case 3 | Ductal, ER+ | 6 cm | Yes | Yes | No | 23.7 |

| Case 4 | Ductal, ER/PR+ | 6 cm | No | Yes | Yes | 32.4 |

| Case 5 | Lobular, ER/PR+ | 6 cm | Yes | Yes | No | 29.4 |

| Case 6 | Ductal, ER/PR+ | 10 cm | No | Yes | No | 31.0 |

| Control 1 | -NA- | 4 cm | -NA- | No | Yes | 24.41 |

†All BE cases were nondysplastic BE; SSBE, short segment BE.

DISCUSSION

We have observed that select families with aggregation of BE/EAC also have multiple female members affected with breast cancer. To assess the observed association of breast cancer and BE/EAC from our pedigree analysis of familial BE/EAC, we compared the incidence of BE in Caucasian females with breast cancer to a matched control group without breast cancer. Consistent with our hypothesis, a diagnosis of breast cancer was marginally associated with increased incidence of BE.

While familial clustering of BE/EAC and breast cancer could derive from a common inherited susceptibility or common environmental risk factors such as diet, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and breast-feeding history, at least in some of these families the pedigree structure suggests a genetic influence. Germ- line mutations that predispose to EAC have been recently described and these infrequently occurring mutations have only been recognized in the past two decades.36,37 Several genetic factors predisposing to breast cancer have been described, including well-described cancer syndromes among which BRCA-associated hereditary breast and ovarian cancer is the best characterized.38–42 However, aside from germ-line TP53 mutations, neither BE nor EAC is known to be associated with mutations of BRCA1, BRCA2, or other hereditary cancer syndromes.43 Likely, the underlying genetic susceptibility to BE/EAC and breast cancer in these families relates to alterations of other genes. This does not exclude the possibility of an unrecognized TP53 mutation in these families, however, there are no sarcomas, brain tumors, or adrenocortical carcinomas reported in these families. It would be reasonable to examine other breast cancer associated genes in these families.

Prior studies have investigated a link between BE and breast cancer with conflicting results. Sartori et al. reported an increased incidence of BE in female breast cancer patients identified soon after completion of chemotherapy. The proposed mechanism behind this histological change was drug-induced destruction of esophageal squamous epithelium with resultant re-epithelialization by undifferentiated stem cells that ultimately differentiate into columnar cells characteristic of epithelium Barrett's.44 However, similar studies did not find BE following chemotherapy for breast cancer,45,46 and a large population-based cohort study did not identify an association with a prior history of breast cancer and EAC.47

A shared role for sex hormones in the development of BE/EAC and breast cancer would be surprising given the male predilection of BE and EAC and the female predilection of breast cancer. Indeed, despite the common expression of the estrogen receptor-beta (ER-B) in breast cancer and BE/EAC,48,49 no protective effect for EAC has been identified with hormone replacement therapy or after treatment for prostate cancer. Furthermore there is no identified increase in EAC with tamoxifen therapy47,50,51 suggesting no clear protective role for estrogen or progesterone in EAC. Contrarily, the shared protective role of breastfeeding in both cancers suggests common function of sex hormones, although the mechanism has not been defined.

Breast cancer and EAC share several common molecular mechanisms, which make an association plausible. In both cancers, HER2 is expressed and can guide effective targeted chemotherapy.52–55 Furthermore, insulin-like growth factor has been associated with progression of both breast cancer and EAC, which may partly explain the link with obesity.56–58 Additionally, studies of both breast cancer and EAC have identified recurrent fusion of the RPS6KB1 and VMP1 genes associated with decreased survival, suggesting that rearrangements in the chromosome 17q23.1 is a common event in some cases of breast cancer and EAC.59,60 Intriguingly, CTHRC1 a germ-line mutation associated with BE/EAC is upregulated in a number of human cancers including breast cancer and aberrant expression is associated with increased metastasis and worse survival.36,61,62

Some limitations of this study warrant consideration. For example, the data relating to the familial Barrett's esophagus are derived from a select group and therefore subject to ascertainment bias. Given that males disproportionately have BE/EAC compared to women, we might be biased into seeing the more common breast cancer in women. However, the fact that the breast cancer seems to follow the inheritance of BE/EAC makes this less likely. We do not have a large enough sample size of familial Barrett's esophagus pedigrees meeting our inclusion criteria for this study to determine if this is a statistically significant association.

We report these multiplex families from a large familial BE/EAC registry that also have multiple family members with breast cancer with a pattern of inheritance strongly suggestive of an inherited breast—BE/EAC kindred. Detailed genetic analysis of such rare families may provide clues for understanding common environmental and genetic factors underlying these phenotypic–genotypic correlations. We postulate there might be a common genetic or environmental susceptibility between breast cancer and BE/EAC and provide supportive evidence with a case-control study showing increased BE incidence in patients with breast cancer. Future research efforts are needed to improve BE screening and surveillance; identify common genetic or environmental contributory factors; improve understanding of carcinogenesis; and uncover novel diagnostic or treatment targets for breast cancer and BE/EAC.

Notes

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Eloubeidi M A, Mason A C, Desmond R A, El-Serag H B. Temporal trends (1973-1997) in survival of patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma in the United States: a glimmer of hope? Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98: 1627–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel R L, Miller K D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin 2017; 67: 7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peters J H, Clark G W, Ireland A P, Chandrasoma P, Smyrk T C, DeMeester T R. Outcome of adenocarcinoma arising in Barrett's esophagus in endoscopically surveyed and nonsurveyed patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1994; 108(5): 813–21; discussion 21–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Verbeek R E, Leenders M, Ten Kate F J et al. Surveillance of Barrett's esophagus and mortality from esophageal adenocarcinoma: a population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109: 1215–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bhat S K, McManus D T, Coleman H G et al. Oesophageal adenocarcinoma and prior diagnosis of Barrett's oesophagus: a population-based study. Gut 2015; 64: 20–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Spechler S J. Barrett esophagus and risk of esophageal cancer. JAMA 2013; 310: 627–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. de Jonge P J, van Blankenstein M, Looman C W, Casparie M K, Meijer G A, Kuipers E J. Risk of malignant progression in patients with Barrett's oesophagus: a Dutch nationwide cohort study. Gut 2010; 59: 1030–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Abrams J A, Fields S, Lightdale C J, Neugut A I. Racial and ethnic disparities in the prevalence of Barrett's esophagus among patients who undergo upper endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6: 30–4. PMCID: 3712273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Howlader N, Ries L A, Stinchcomb D G, Edwards B K. The impact of underreported veterans affairs data on national cancer statistics: analysis using population-based SEER registries. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009; 101: 533–6. PMCID: 2720708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jiao L, Kramer J R, Chen L et al. Dietary consumption of meat, fat, animal products and advanced glycation end-products and the risk of Barrett's oesophagus. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013; 38: 817–24. PMCID: 3811083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jiao L, Kramer J R, Rugge M et al. Dietary intake of vegetables, folate, and antioxidants and the risk of Barrett's esophagus. Cancer Causes Control 2013; 24: 1005–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Ceglie A, Fisher D A, Filiberti R, Blanchi S, Conio M. Barrett's esophagus, esophageal and esophagogastric junction adenocarcinomas: the role of diet. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2011; 35: 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Huang W, Han Y, Xu J, Zhu W, Li Z. Red and processed meat intake and risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Cancer Causes Control 2013; 24: 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harris H R, Willett W C, Vaidya R L, Michels K B. An adolescent and early adulthood dietary pattern associated with inflammation and the incidence of breast cancer. Cancer Res 2017; 77: 1179–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Farvid M S, Cho E, Chen W Y, Eliassen A H, Willett W C. Adolescent meat intake and breast cancer risk. Int J Cancer 2015; 136: 1909–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cheng K K, Sharp L, McKinney P A et al. A case-control study of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in women: a preventable disease. Br J Cancer 2000; 83: 127–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Morimoto L M, White E, Chen Z et al. Obesity, body size, and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer: the Women's Health Initiative (United States). Cancer Causes Control 2002; 13: 741–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. El-Serag H B, Hashmi A, Garcia J et al. Visceral abdominal obesity measured by CT scan is associated with an increased risk of Barrett's oesophagus: a case-control study. Gut 2014; 63: 220.2–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Beddy P, Howard J, McMahon C et al. Association of visceral adiposity with oesophageal and junctional adenocarcinomas. Br J Surg 2010; 97: 1028–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Agnoli C, Grioni S, Sieri S et al. Metabolic syndrome and breast cancer risk: a case-cohort study nested in a multicentre italian cohort. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0128891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Leggett C L, Nelsen E M, Tian J et al. Metabolic syndrome as a risk factor for Barrett esophagus: a population-based case-control study. Mayo Clin Proc 2013; 88: 157–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lindkvist B, Johansen D, Stocks T et al. Metabolic risk factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma: a prospective study of 580 000 subjects within the Me-Can project. BMC Cancer 2014; 14: 103 PMCID: 3929907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and breastfeeding: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 47 epidemiological studies in 30 countries, including 50302 women with breast cancer and 96973 women without the disease. Lancet North Am Ed 2002; 360: 187–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cronin-Fenton D P, Murray L J, Whiteman D C et al. Reproductive and sex hormonal factors and oesophageal and gastric junction adenocarcinoma: a pooled analysis. Eur J Cancer 2010; 46: 2067–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Takkouche B, Regueira-Mendez C, Etminan M. Breast cancer and use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008; 100: 1439–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kastelein F, Spaander M C, Biermann K, Steyerberg E W, Kuipers E J, Bruno M J. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and statins have chemopreventative effects in patients with barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology 2011; 141: 2000–8; quiz e13-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Omer Z B, Ananthakrishnan A N, Nattinger K J et al. Aspirin protects against Barrett's esophagus in a multivariate logistic regression analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012; 10: 722–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu B, Yi Z, Guan X, Zeng Y X, Ma F. The relationship between statins and breast cancer prognosis varies by statin type and exposure time: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2017; 164: 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nguyen T, Khalaf N, Ramsey D, El-Serag H B. Statin use is associated with a decreased risk of Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology 2014; 147: 314–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shaheen N J, Falk G W, Iyer P G, Gerson L B. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of Barrett's esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111: 30–50; quiz 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Reid B J. Genomics, endoscopy, and control of gastroesophageal cancers: a perspective. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 3: 359–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Verbeek R E, Spittuler L F, Peute A et al. Familial clustering of Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma in a European cohort. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12: 1656–1663.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chak A, Lee T, Kinnard M F et al. Familial aggregation of Barrett's oesophagus, oesophageal adenocarcinoma, and oesophagogastric junctional adenocarcinoma in Caucasian adults. Gut 2002; 51: 323–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Chak A, Faulx A, Kinnard M et al. Identification of Barrett's esophagus in relatives by endoscopic screening. Am J Gastroenterol 2004; 99: 2107–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sun X, Elston R, Barnholtz-Sloan J et al. A segregation analysis of Barrett's esophagus and associated adenocarcinomas. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010; 19: 666–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Orloff M, Peterson C, He X et al. Germline mutations in MSR1, ASCC1, and CTHRC1 in patients with Barrett esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. JAMA 2011; 306: 410–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fecteau R E, Kong J, Kresak A et al. Association between germline mutation in VSIG10L and familial Barrett neoplasia. JAMA Oncol 2016; 2: 1333–9. PMCID: 5063702 Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and none were reported. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Couch F J, Nathanson K L, Offit K. Two decades after BRCA: setting paradigms in personalized cancer care and prevention. Science 2014; 343: 1466–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pilarski R, Burt R, Kohlman W, Pho L, Shannon K M, Swisher E. Cowden syndrome and the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome: systematic review and revised diagnostic criteria. J Natl Cancer Inst 2013; 105: 1607–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Malkin D. Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Genes Cancer 2011; 2: 475–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Beggs A D, Latchford A R, Vasen H F et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut 2010; 59: 975–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fitzgerald R C, Hardwick R, Huntsman D et al. Hereditary diffuse gastric cancer: updated consensus guidelines for clinical management and directions for future research. J Med Genet 2010; 47: 436–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sorrell A D, Espenschied C R, Culver J O, Weitzel J N. Tumor protein p53 (TP53) testing and Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Mol Diagn Ther 2013; 17: 31–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sartori S, Nielsen I, Indelli M, Trevisani L, Pazzi P, Grandi E. Barrett esophagus after chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil (CMF): an iatrogenic injury? Ann Intern Med 1991; 114: 210–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Peters F T, Sleijfer D T, van Imhoff G W, Kleibeuker J H. Is chemotherapy associated with development of Barrett's esophagus? Digest Dis Sci 1993; 38: 923–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Herrera J L, Uzel C, Martino R, Cooke C, DiPalma J A. Barrett's esophagus: lack of association with adjuvant chemotherapy for localized breast carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc 1992; 38: 551–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chandanos E, Lindblad M, Jia C, Rubio C A, Ye W, Lagergren J. Tamoxifen exposure and risk of oesophageal and gastric adenocarcinoma: a population-based cohort study of breast cancer patients in Sweden. Br J Cancer 2006; 95: 118–22. PMCID: 2360495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lippman M E, Allegra J C. Quantitative estrogen receptor analyses: the response to endocrine and cytotoxic chemotherapy in human breast cancer and the disease-free interval. Cancer 1980; 46: 2829–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Akgun H, Lechago J, Younes M. Estrogen receptor-beta is expressed in Barrett's metaplasia and associated adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Anticancer Res 2002; 22: 1459–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lindblad M, Ye W, Rubio C, Lagergren J. Estrogen and risk of gastric cancer: a protective effect in a nationwide cohort study of patients with prostate cancer in Sweden. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2004; 13: 2203–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lindblad M, Garcia Rodriguez L A, Chandanos E, Lagergren J. Hormone replacement therapy and risks of oesophageal and gastric adenocarcinomas. Br J Cancer 2006; 94: 136–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Romond E H, Perez E A, Bryant J et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 1673–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Piccart-Gebhart M J, Procter M, Leyland-Jones B et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 1659–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gowryshankar A, Nagaraja V, Eslick G D. HER2 status in Barrett's esophagus and esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Oncol 2014; 5: 25–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bang Y J, Van Cutsem E, Feyereislova A et al. Trastuzumab in combination with chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for treatment of HER2-positive advanced gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer (ToGA): a phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet North Am Ed 2010; 376: 687–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sachdev D, Yee D. The IGF system and breast cancer. Endocrine Related Cancer 2001; 8: 197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Greer K B, Thompson C L, Brenner L et al. Association of insulin and insulin-like growth factors with Barrett's oesophagus. Gut 2012; 61: 665–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Doyle S L, Donohoe C L, Finn S P et al. IGF-1 and its receptor in esophageal cancer: association with adenocarcinoma and visceral obesity. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107: 196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Blum A E, Venkitachalam S, Guo Y et al. RNA sequencing identifies transcriptionally viable gene fusions in esophageal adenocarcinomas. Cancer Res 2016; 76: 5628–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Inaki K, Hillmer A M, Ukil L et al. Transcriptional consequences of genomic structural aberrations in breast cancer. Genome Res 2011; 21: 676–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Tang L, Dai D L, Su M, Martinka M, Li G, Zhou Y. Aberrant expression of collagen triple helix repeat containing 1 in human solid cancers. Clin Cancer Res 2006; 12: 3716–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kim J H, Baek T H, Yim H S et al. Collagen triple helix repeat containing-1 (CTHRC1) expression in invasive ductal carcinoma of the breast: the impact on prognosis and correlation to clinicopathologic features. Pathol Oncol Res 2013; 19: 731–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]