Abstract

Elevated ozone (O3) can alter the phenotypes of host plants particularly in induction of leaf senescence, but few reports examine the involvement of phytohormone in O3-induced changes in host phenotypes that influence the foraging quality for insects. Here, we used an ethylene (ET) receptor mutant Nr and its wild-type to determine the function of the ET signaling pathway in O3-induced leaf senescence, and bottom-up effects on the performance of Bemisia tabaci in field open-top chambers (OTCs). Our results showed that elevated O3 reduced photosynthetic efficiency and chlorophyll content and induced leaf senescence of plant regardless of plant genotype. Leaf senescence in Nr plants was alleviated relative to wild-type under elevated O3. Further analyses of foliar quality showed that elevated O3 had little effect on phytohormone-mediated defenses, but significantly increased the concentration of amino acids in two plant genotypes. Furthermore, Nr plants had lower amino acid content relative to wild-type under elevated O3. These results provided an explanation of O3-induced increase in abundance of B. tabaci. We concluded that O3-induced senescence of plant was ET signal-dependent, and positive effects of O3-induced leaf senescence on the performance of B. tabaci largely resulted from changes of nutritional quality of host plants.

Keywords: elevated O3, ethylene, Bemisia tabaci, leaf senescence, amino acid, hormone-dependent defense

Introduction

Global tropospheric ozone (O3) concentration has increased from pre-industrial less than 10 to current 35–50 ppb in the Northern hemisphere (Ainsworth et al., 2012), and is predicted to be still increasing at a rate of approximately 0.5–2% per year in some regions, such as East Asia (Ohara et al., 2007; IPCC, 2013; Cooper et al., 2014). Tropospheric O3 is an important atmospheric pollution type and also a greenhouse gas, which can cause changes in plant metabolism, such as changes in photosynthetic rate, nutritional content, and secondary compounds (Ashmore, 2005; Gupta et al., 2005). The alteration of plant biochemistry under elevated O3 could affect the quality and palatability of plant tissue, and therefore changes in interactions with herbivorous insects (Peltonen et al., 2010).

Elevated O3 leads to significant changes in plant phenotypes, such as visible leaf injury, acceleration of leaf senescence, and growth limitation (Miller et al., 1999; Wittig et al., 2007), with considerable concern on leaf senescence. Elevated O3 causes a series of senescence-related processes which includes decrease in photosynthetic rate, damage in chlorophyll fluorescence, and increase in leaf defoliation (Gielen et al., 2006). Ethylene (ET) signaling pathway is widely accepted as a positive mediator of developmental leaf senescence, in which leaf senescence is delayed or alleviated for ET-insensitive mutants, and accelerated for plants exogenous application of ET (Lim et al., 2007; Koyama, 2014; Qiu et al., 2015). Recent research demonstrated that ET signaling pathway also serves as a positive mediator in abiotic stress-induced leaf senescence, such as drought or heat stress (Young et al., 2004). High temperature-induced leaf senescence is delayed by spraying ET inhibitor 1-MCP in soybean plants (Djanaguiraman et al., 2011). Although ET production and its signaling pathway are upregulated under elevated O3 (Moeder et al., 2002; Ludwików et al., 2009, 2014), it is unclear the role of ET signaling pathway in O3-induced leaf senescence.

There are inconsistent responses of insects to elevated O3 (Manninen et al., 2000; Percy et al., 2002; Cui et al., 2012), of which factors have been the focus of study, particularly, response of host plants, sensitivity and parameters of herbivores, or O3 level (Holopainen and Kainulainen, 1997; Hillstrom et al., 2010; Couture and Lindroth, 2012). These reports suggest that the variable responses of N nutrition and secondary metabolites in host plants under elevated O3 result in the contradictory effects on herbivorous insects. The population fitness of herbivores tends to be reduced if host plants have low N nutrient value and high level of defense metabolites, while it tends to be increased on host plants with high N nutrition under elevated O3 (Holopainen and Kainulainen, 1997; Cui et al., 2012). It is worthwhile to note that Holopainen (2002) has proposed a hypothesis that contradictory impacts could be interpreted by premature senescence of host plants under elevated O3, but experimental evidence is lacking.

Leaf senescence indeed affects the performance of insects via an alteration of plant N nutrient value and defense metabolism. With respect to nutritional value, senescing leaves may serve as a good source of nitrogen for sap-sucking insects. The N-containing substances are converted into amino acids and transported from the senescing leaves via phloem loading (Lim et al., 2007). During export from senescing leaves via phloem, nitrogen is easily accessed by sap-sucking insects. For example, the leaf senescence induced by black pecan aphid (Melanocallis caryaefoliae) infestation increases amino acid concentrations in phloem (Cottrell et al., 2009, 2010), which may be responsible for promoting subsequent aphid setting and nymphal development (White, 2015). In addition to nutrient metabolism, premature leaf-senescence can positively regulate plant resistance against sap-sucking insect infestation. Green peach aphid (Myzus persicae, GPA) counts are reduced on hyper-senescence mutant plants (cpr5 and ssi2), while increase in pad4 mutants is observed with a delay in GPA-induced senescence (Pegadaraju et al., 2005). Therefore, although needing experimental testing, it is reasonable to speculate that O3-induced leaf senescence could affect the population fitness of sap-sucking insects via changes in foliar nitrogenous nutrition and defense metabolism.

Bemisia tabaci is a sucking insect that is regarded as the most destructive agricultural invasive pest in China. B. tabaci causes extensive crop losses annually, estimated at billions of dollars, through feeding directly and virus transmission (Dalton, 2006). Understanding the physiological basis involved in climate change-driven outbreak of invasive insects is crucial to crop production health and security. Here, we used two tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum) genotypes that differed in sensitivity to ET signals to determine how ET signaling pathway regulated leaf senescence under elevated O3, and related bottom-up effects on B. tabaci. Our specific goals were to determine the differences in these two plant genotypes in (i) leaf senescence under elevated O3; (ii) nitrogenous nutrition and resistance; and (iii) population abundance of B. tabaci.

Materials and Methods

Treatments Under Different O3 Concentrations

The field experiments were carried out in eight 2.1 m diameter and 2 m height octagonal, open-top chambers (OTCs) at the Observation Station of the Global Change Biology Group, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences in Xiaotangshan County, Beijing, China (40°11′N, 116°24′E). The O3 treatments were set up as: current tropospheric O3 levels (40 nL L-1) and elevated O3 levels (90 nL L-1). The O3 treatment was performed in four paired OTCs. Each OTC with elevated O3 was matched with one OTC with ambient O3. The OTCs were ventilated with air daily from 8:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. In the elevated O3 treatment, the method of O3 generation was offered by Cui et al. (2012). O3 concentrations were monitored (AQL-200, Aeroqual, New Zealand) four times per day throughout the studies to keep relatively stable O3 levels within the OTCs. The O3 levels throughout the research were 42 ± 3.8 nL L-1 in the ambient O3 OTCs and 89 ± 5.3 nL L-1 in the elevated O3 OTCs. Air temperatures were measured and there was not obviously difference between the two treatments (22.7 ± 1.9°C in ambient O3 chambers vs 24.2 ± 2.0°C in elevated O3 chambers).

Plants and Insects

Wild-type Ailsa Craig (AC) and ET-insensitive mutation Never ripe (Nr) tomato plants were kindly supplied by Professor Chuanyou Li (Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences). The N-terminal coding region of an ET receptor (Le-ETR3/NR) was associated with a single base substitution in ET-insensitive mutation Nr. Nr plants showed defects in the ET-induced triple response in etiolated hypocotyls and also exhibited the lack of fruit ripening (Lanahan et al., 1994; Wilkinson et al., 1995).

The germinated seeds were individually sown into approximate 1.5-L small pots. Tomato plants were maintained in the OTCs for 43 days from seedling with two to three leaves to the end of the experiment (19 May to 30 June 2015). The position of pot within each chamber was re-randomized once every week. There were 88 tomato plants within each OTC (704 plants in total), which contained 54 AC plants and 34 Nr plants. The insecticides were not used throughout the research. The plants were irrigated every 2 days.

The B. tabaci Mediterranean genetic group, also called Q biotype, was kindly provided by Professor Youjun Zhang (Institute of Vegetables and Flowers, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences). The B. tabaci population was maintained on the cotton plants in separated cages in a greenhouse at 25 ± 2°C and 75 ± 10% relative humidity, with a photoperiod of 14 h light: 10 h dark. The 30 adults were sampled to determine the B. tabaci biotypes of colony by sequencing a molecular marker mtCO I (mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase I) gene (De Barro et al., 2011).

ET Precursor ACC and ET Inhibitor 1-MCP

During O3 exposure, 320 plants in total in eight OTCs, which contained 40 tomato plants (30 AC plants and 10 Nr plants) with uniform size in per OTC, were randomly selected. Ten AC plants were sprayed with ACC (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany, AC/ACC plants) and 10 AC plants were sprayed with 1-MCP (Yuanye, Beijing, China, AC/1-MCP plants). Ten AC plants and 10 Nr plants were sprayed with H2O (AC/H2O and Nr/H2O), which was regarded as control treatment. Both sides of leaves were sprayed once every two days at 8:00 a.m. along the 43 days of the experiment. Treatment of samples with ACC was conducted by dissolving 30 mg of ACC in 1 L of distilled water with 100 μL L-77 at a final concentration of 50 ppm. The final concentration of 1-MCP was 1 ppm by dissolving 0.005 g 1-MCP into distilled water (1 L) with 100 μL L-77 (Kevany et al., 2007). After 38-day O3 fumigation (19 May to 25 June 2015), the leaves from 40 tomato plants of each OTC (10 AC/H2O plants, 10 AC/ACC plants, 10 AC/1-MCP plants, and 10 Nr/H2O plants) were collected and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen to analyze ROS accumulation, ET emission, and the expression of ET synthase genes.

Bemisia tabaci Infestation

Plants were arranged for two different treatments with B. tabaci. After 21-day O3 fumigation (19 May to 9 June 2015), 128 tomato plants in total in eight OTCs, which contained 16 tomato plants (eight AC plants and eight Nr plants) with uniform size in per OTC, were randomly selected for 21-day B. tabaci infestation experiment. Each plant was inoculated with five pairs of newly emerging B. tabaci. The B. tabaci was maintained in a clip-cage to develop and produce offspring on tomato plants for 3 weeks. All B. tabaci stages (eggs, one to four nymphs and adults) on per plant were counted as the B. tabaci abundance in 30 June 2015.

In the second part of this experiment, 128 tomato plants in total in eight OTCs, which 16 tomato plants (eight AC plants and eight Nr plants) with uniform size in per OTC, were randomly selected after 41-day O3 fumigation (19 May to 28 June 2015). Each plant was damaged with ten pairs of newly emerging B. tabaci. The B. tabaci, which was maintained within a clip-cage, infested freely for 24 h. Another 128 tomato plants in total in eight OTCs, which included 16 tomato plants (eight AC plants and eight Nr plants) with uniform size in per OTC, were also randomly selected after 41-day O3 fumigation (19 May to 28 June 2015). These plants were not infested with B. tabaci, which served as un-infested control. The un-infested and 24 h-infested leaves of each tomato plants were harvested in 29 June 2015 and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen for amino acid, N concentration, hormone, ET emission, and the expression of hormone-signal related genes analysis.

Plant Photosynthesis and Growth Traits

Eight tomato plants of each cultivar per chambers were randomly selected for determining net photosynthetic rate by using a Li-Cor 6400 gas exchange system (LI-COR, Inc., Lincoln, NE, United States). Leaf chlorophyll content of tomato plant was measured with a Minolta SPAD-502 plus (Konica Minolta Sensing, Inc., Osaka, Japan).

Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Accumulation

Frozen powder, which was hand ground in liquid nitrogen, was weighed and immediately homogenized with 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.3). The homogenized extract was centrifuged twice at 15,000 rpm for 5 min. The quantification of ROS was determined by 10 mM H2DCFDA (Aladdin, Shanghai, China), which was dissolved in DMSO, and incubated for 10 min in darkness at room temperature. Fluorescence absorbance was determined by a SpectraMax i3 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, United States). The quantification of total protein was measured by Bradford dye. The ROS production was expressed as relative fluorescence units (RFUs) per milligram of protein.

Amino Acids and N Concentration

Approximately 0.2 g leaf samples were homogenized in liquid nitrogen, and then were extracted within 2.5 mL of cold 5% acetic acid. The extraction was agitated for 1 h on a shaker (C. Gerhardt GmbH & Co., KG, Königswinter, Germany) at room temperature. Homogenates were centrifuged at 4000 rpm for 15 min, and the supernatants were used for leaf individual amino acid analyses. The leaf amino acids were measured by reverse-phase HPLC with precolumn derivatization using o-phthaldialdehyde (OPA) and 9-fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (FMOC). The quantification of amino acids was calculated with reference to the standard curves of AA-S-17 (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, United States, PN: 5061-3331) amino acid mixture, supplemented with asparagine, glutamine, and tryptophan (Sigma-Aldrich Co., St. Louis, MO, United States). Free amino acid concentrations of the five standard solutions were 250, 100, 50, 25, and 10 pmol μL-1. The mixed sample with 10 μL amino acid sample, 20 μL sodium borate buffer (0.4N, pH 10.4), 10 μL OPA, 10 μL FMOC, and 50 μL water was injected to the HPLC (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, United States). The HPLC analysis was performed using a method provided by Guo et al. (2015). Total amino acids in leaves were measured according to a method as described previously (Chen et al., 2004). N concentration in leaves was measured using Kjeltec N analysis (Foss automated KjeltecTM instruments, Model 2100, Hillerød, Denmark).

ET Emission

The ET emission from leaves was determined according to Wilkinson and Davies (2009) with some modification. After 15 min, the excised leaves were attached to a water-saturated filter paper in sealed vials at room temperature. The containers were flushed with fresh air from outside the laboratory for 1 min and then immediately capped with a rubber septum lid. After 1 h, 1 mL gas from the vial headspace was withdrawn with gas-tight syringes, and injected to gas chromatography (7890A, Agilent Technologies UK Ltd., Wokingham, United Kingdom) fitted with a GS-GASPRO (60 m × 0.320 mm) column. The temperature was maintained at 80°C for 4 min to resolve ET and then increased at 25°C min-1 to 250°C and held for 10.8 min. The flow rate of hydrogen carrier gas was 40 mL min-1 and was detected by flame ionization detector (FID). The ET production rate was estimated by comparison of sample peak areas of known ET standards (BOC Special Gases, Manchester, United Kingdom) and corrected for tissue fresh weight and the duration of incubation to determine ET emission rate.

Hormone Analysis

The foliar hormone was measured according to Guo et al. (2017) with some modification. Approximately 300 mg of plant tissue was hand ground in liquid nitrogen and was quickly homogenized in 0.5 mL extraction buffer for 30 min at 4°C with gentle agitation on a shaker. Subsequently, each sample was additionally added 1 mL of CH2Cl2, and then agitated for 30 min on a shaker at 4°C. The homogenized sample was centrifuged at 13,000 g for 10 min. After centrifugation, the lower layer was collected, and then was concentrated in a dry machine. The concentrated sample was re-solubilized in 200 μL of MeOH. Next, 1 μL of the sample was injected into an Agilent ZORBAX SB-Aq column (600 bar, 2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.8 μm) for hormone analysis. The hormone contents were calculated with reference to standard curves.

Protease Activity

Approximately 200 mg tomato leaf samples were ground in liquid nitrogen. It was mixed with 1 mL 50 mM Tris-HCL buffer (pH 7.5) at 4°C for 30 min. The homogenized extract was centrifuged at 4°C, 12,000 rpm for 40 min. After centrifugation, the upper layer was collected for protease activity analysis. The supernatants (100 μL) was mixed with 600 μL 50 mM pH 8.0 Na-Pi buffer (50 mM pH 5.0 citric acid- phosphate buffer; pH 7.5 Na-Pi; pH 9.5 Tris-HCL buffer; pH 11 NaOH-NaHCO3) containing 100 μL 0.6% (w/v) azocasein (Sigma, United States), and the mixture was incubated at 37°C for 3 h. The reaction was terminated by adding 400 μL 10% TCA (Aladdin, Shanghai, China). The mixture was maintained at 4°C for 30 min and then centrifuged at 4°C, 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The absorbance of the filtrate at 366 nm was determined by fluorescence spectrophotometry (SpectraMax i3, Molecular Devices, United States; Wang et al., 2004).

RNA Extraction and Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Analysis

Gene expression was measured using quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. Each treatment was replicated with four biological repeats and four technical repeats. The RNA easy Mini Kit (Qiagen) was used to isolate total RNA from the leaves. The cDNA was generated from 1 μg of RNA. We used real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) to determine the mRNA levels. Specific primers for each gene were designed from The EST sequences was used to design specific primers for target genes using PRIMER5 software (Table 1). The qPCR reactions were performed in a 20 μL total reaction volume that included 10 μL of 2× SYBR Premix EX TaqTM (Qiagen) master mix, 5 mM of each gene-specific primer, and 1 μL of pure cDNA template. Reactions were carried out using the Mx 3000P detection system (Stratagene), with the parameters [the elongation temperature (68°C)] as described in Guo et al. (2015). According to the studies about reference genes used in tomato plants (Expósito-Rodríguez et al., 2008; Løvdal and Lillo, 2009; Mascia et al., 2010), we chose five different reference genes including ACTIN, EF-1, TIPL-41, GADPH, and TUB, to get the best reference gene, which is expressed at a relative constant level among different experimental treatments, in my experimental conditions. We used TIP41 and Actin as the internal qPCR standard. The expression level of each target gene was standardized to the tomato TIP41 gene and Actin gene (Expósito-Rodríguez et al., 2008).

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for real-time quantitative PCR.

| Gene | GenBank | Primer sequence(5′-3′) |

|---|---|---|

| accession no. | ||

| PR (pathogenesis-related protein) | Solyc01g106620.2 |

F: GAGGGCAGCCGTGCAA R: CACATTTTTCCACCAACACATTG |

| GLU (beta-1, 3-glucanase) | CK664757 |

F: GCGGTGTTCAGCCTGGATG R: AGCATGAGCAAGAAGTATGTTGTG |

| LOX (lipoxygenase) | U37840 |

F: GACTGGTCCAAGTTCACGATCC R: ATGTGCTGCCAATATAAATGGTTCC |

| PI (proteinase inhibitor) | K03291 | F: GAAAATCGTTAATTTATCCCACCG R: ACATACAAACTTTCCATCTTTACCA |

|

ACO (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase) |

X58273 |

F: GCCAAAGAGCCAAGATTTGA R: TTTTTAATTGAATTGGGATCTAAGC |

|

ACS (1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase) |

X59139 |

F: GGTCTTGCTGAAAATCAGCTTTGT R: AGTTGGCAATGGCCTTGAATG |

| ERF1 (ethylene-responsive factor 1) | AY044236 |

F: AGAGACCAAGGACCCCTCAT R: AGTAGAGACCAAGGACCCCTC |

| ERF2 (ethylene-responsive factor 2) | AY192368 |

F: AAGGGGTTAGGGTTTGGTTAGG R: CAAGCAATGTTCAAGGGAGGG |

| TIP41 | SGN-U321250 |

F: AGGCCTTGTCTTCGAAAGGA R: TCCTTTAGGACACTCCAACATGG |

| Actin | AB199316 |

F: TGGTCGGAATGGGACAGAAG R: CTCAGTCAGGAGAACAGGGT |

Statistical Analyses

The statistical package IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 was used for statistical analyses. A split–split plot design was applied to analyze the hormone content and gene expression of defense signaling, which the main factor was O3 and block (a pair of OTCs with elevated and ambient OTCs), the subplot factor was tomato genotypes, and the sub-subplot factor was B. tabaci infestation. The main effects of O3 concentrations, tomato genotype, and B. tabaci infestation on plant were tested according to the following model:

where O is the O3 treatment (i = 2), B is the block (j = 4), G is the tomato genotype (k = 2), and W is the B. tabaci infestation (l = 2). Xijklm represents the error because of the smaller scale differences between samples and variability within blocks (SPSS 21.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Effects were considered significant if P < 0.05. Tukey’s multiple range tests were used to separate means when ANOVAs were significant (P < 0.05). The ET emission, biomass, photosynthetic rate, chlorophyll content, ROS, curl leaves, O3-damaged stippled leaves, deciduous leaves of plants, population abundance, individual amino acids, and total amino acid under two O3 concentrations were analyzed by a split-plot design, which O3 and block as the main effects and tomato genotype as the subplot effect.

Results

Elevated O3 Increased the ET Synthesis and Emission of Tomato Plants

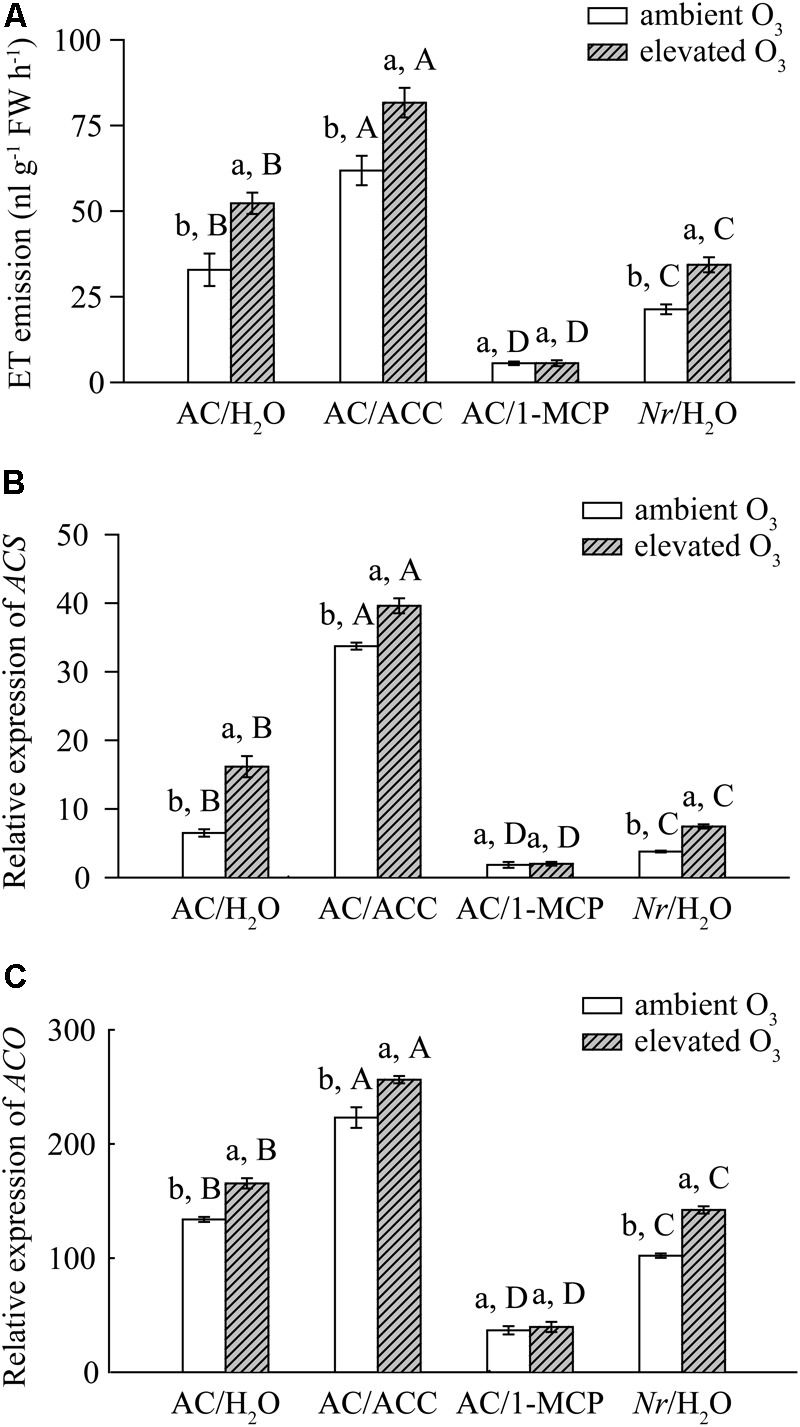

Elevated O3 significantly increased the ET production by 37% in AC plants spraying with H2O (AC/H2O plants), by 24% in AC plant spraying with ACC (AC/ACC plants), and by 38% in Nr plants spraying with H2O (Nr/H2O plants). However, ET production was not affected by elevated O3 in AC plants spraying with 1-MCP (AC/1-MCP plants). Under both O3 concentrations, the ET production was the highest in AC/ACC plants and the lowest in AC/1-MCP plants. The level of ET emission was significantly higher in AC/H2O plants than in Nr/H2O plants (Figure 1A). We also analyzed ACS and ACO genes, which were two important ET synthesis genes in tomato plants. The expression of foliar ACO and ACS genes were consistent with the level of ET emission, which were upregulated under elevated O3 in AC/H2O plants, AC/ACC plants, and Nr/H2O plants (Figures 1B,C).

FIGURE 1.

The ET production rate and fold-change in the expression of ET synthesis genes of wild-type AC plants spraying with ACC, 1-MCP, and H2O, and of ET-insensitive Nr mutants spraying with H2O grown under ambient O3 and elevated O3. (A) ET production rate. (B) ACS. (C) ACO. Each value represents the mean (±SE) of four OTCs (10 plants for each treatment per OTC). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between ambient O3 and elevated O3 within the same genotype. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between genotypes following with ACC, 1-MCP, or H2O applications within the same O3 treatment.

O3-Induced Leaf Senescence Was Dependent on ET Signaling Pathway

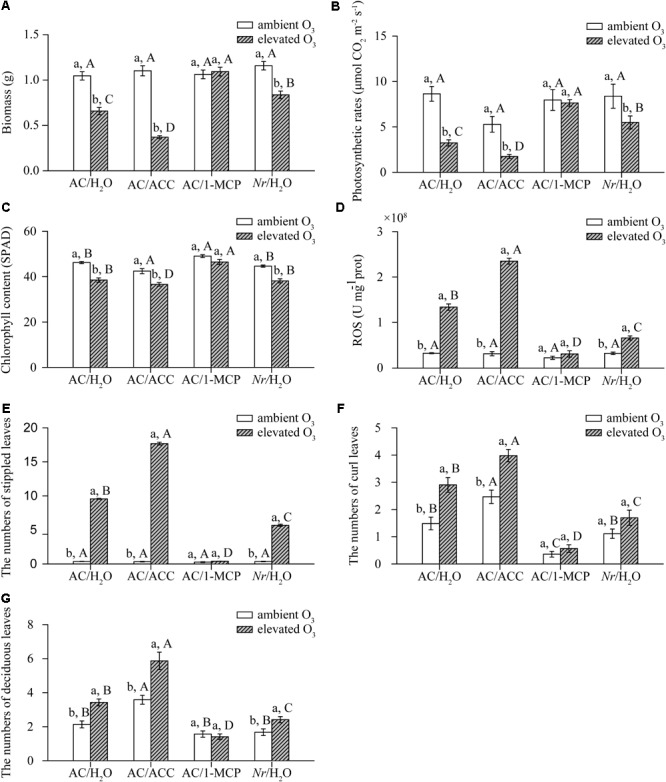

Elevated O3 decreased the plant biomass by 37%, the photosynthetic rate by 62%, and chlorophyll content by 17% in AC/H2O plants. The plant biomass, photosynthetic rate, and chlorophyll content were not affected by elevated O3 in AC/1-MCP plants. Elevated O3 had the most detrimental effects on AC/ACC plants, reducing plant biomass by 66%, photosynthetic rate by 67%, and chlorophyll content by 14%. Compared with AC/H2O plant, elevated O3 had marginal effects on Nr/H2O plants, with decreased biomass of 27%, photosynthetic rate by 34%, and chlorophyll content by 15% (Figures 2A–C).

FIGURE 2.

The phenotype of wild-type AC plants spraying with ACC, 1-MCP, and H2O, and of ET-insensitive Nr mutants spraying with H2O grown under ambient O3 and elevated O3. (A) Biomass. (B) Photosynthetic rate. (C) Chlorophyll content. (D) ROS. (E) O3-damaged stippled leaves. (F) Curl leaves. (G) Deciduous leaves. Each value represents the mean (±SE) of four OTCs (10 plants for each treatment per OTC). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between ambient O3 and elevated O3 within the same genotype. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between genotypes following with ACC, 1-MCP, or H2O applications within the same O3 treatment.

Elevated O3 also increased ROS accumulation and leaf injury, including numbers of O3-damaged stippled leaves, deciduous leaves, and curl leaves in AC/H2O plants, AC/ACC plants, and Nr/H2O plants. ROS accumulation and leaf injury in AC/H2O plants were significantly lower than these in AC/ACC plants, and higher than these in Nr/H2O plants. In AC/1-MCP plants, ROS accumulation and leaf injury were similar under both O3 concentrations (Figures 2D–G).

Elevated O3 Increased the Population Abundance of B. tabaci on Tomato Plants

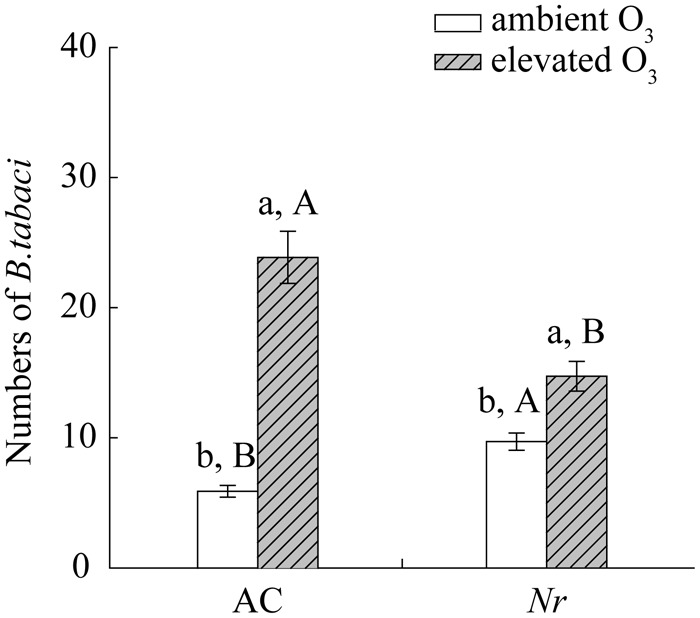

Ozone concentration and plant genotype had significant effects on the population abundance of B. tabaci. Relative to ambient O3, the number of B. tabaci was increased 3-fold on AC plants and 0.5-fold on Nr plants under elevated O3 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Abundance of B. tabaci when fed on two tomato genotypes grown under ambient O3 and elevated O3. Each value represents the mean (±SE) of four OTCs (eight plants for each genotype per OTC). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between ambient O3 and elevated O3 within the same genotype. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between genotypes within the same O3 treatment.

O3-induced leaf senescence activated leaf salicylic acid (SA) and ET signaling pathway, but had no effects on jasmonic acid (JA) signaling pathway.

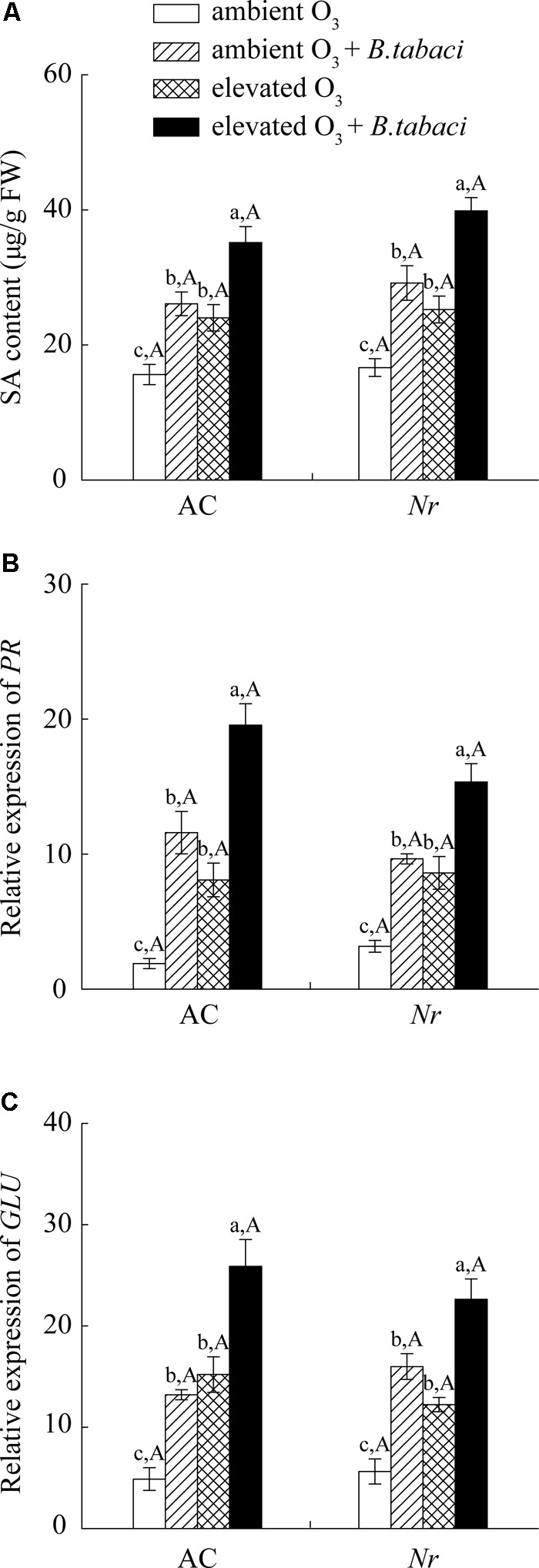

Ozone concentration and B. tabaci infestation had significant effects on the foliar SA content. Regardless of B. tabaci infestation, elevated O3 significantly increased foliar SA content by 54% in AC plants and by 51% in Nr plants (Figure 4A). Under both O3 levels, B. tabaci infestation increased the foliar SA content in AC and Nr plants. Regardless of B. tabaci infestation and O3 concentration, foliar SA content was equivalent in AC and Nr plants. The expression of β-1,3-glucanase (GLU) and pathogenesis-related protein (PR) genes, two downstream genes of SA signaling pathway, was consistent with foliar SA content, which was increased under elevated O3 and B. tabaci infestation, and was not affected by plant genotype (Figures 4B,C).

FIGURE 4.

SA content and fold-change in the expression of related genes involved in the SA-dependent signaling pathway in two tomato genotypes grown under ambient O3 and elevated O3 with and without B. tabaci infestation. (A) SA content. (B) PR. (C) GLU. Each value represents the mean (±SE) of four OTCs (eight plants for each genotype per OTC). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the combinations of B. tabaci treatment and O3 concentrations within the same genotype. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between genotypes within the same O3 treatment and B. tabaci treatment.

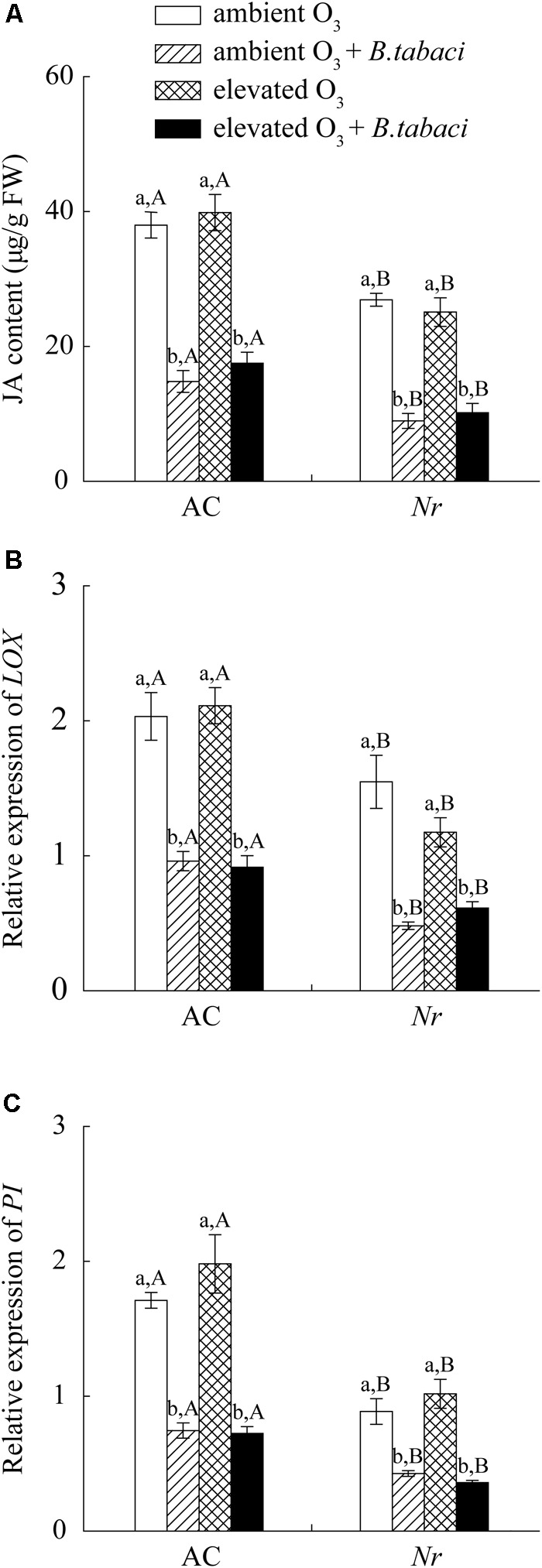

Elevated O3 did not increase the foliar JA accumulation and the relative expression level of lipoxygenase (LOX) and proteinase inhibitor (PI), which were two marker genes of JA signaling pathway, in AC and Nr plants with and without B. tabaci infestation. Under both O3 concentrations, B. tabaci infestation significantly reduced the foliar JA concentration and the relative expression level of LOX and PI. Regardless of B. tabaci infestation and O3 concentration, the foliar JA concentration and the expression of LOX and PI were markedly higher in AC plants than in Nr plants (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

JA content and fold-change in the expression of related genes involved in the JA-dependent signaling pathway in two tomato genotypes grown under ambient O3 and elevated O3 with and without B. tabaci infestation. (A) JA content. (B) LOX. (C) PI. Each value represents the mean (±SE) of four OTCs (eight plants for each genotype per OTC). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the combinations of B. tabaci treatment and O3 concentrations within the same genotype. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between genotypes within the same O3 treatment and B. tabaci treatment.

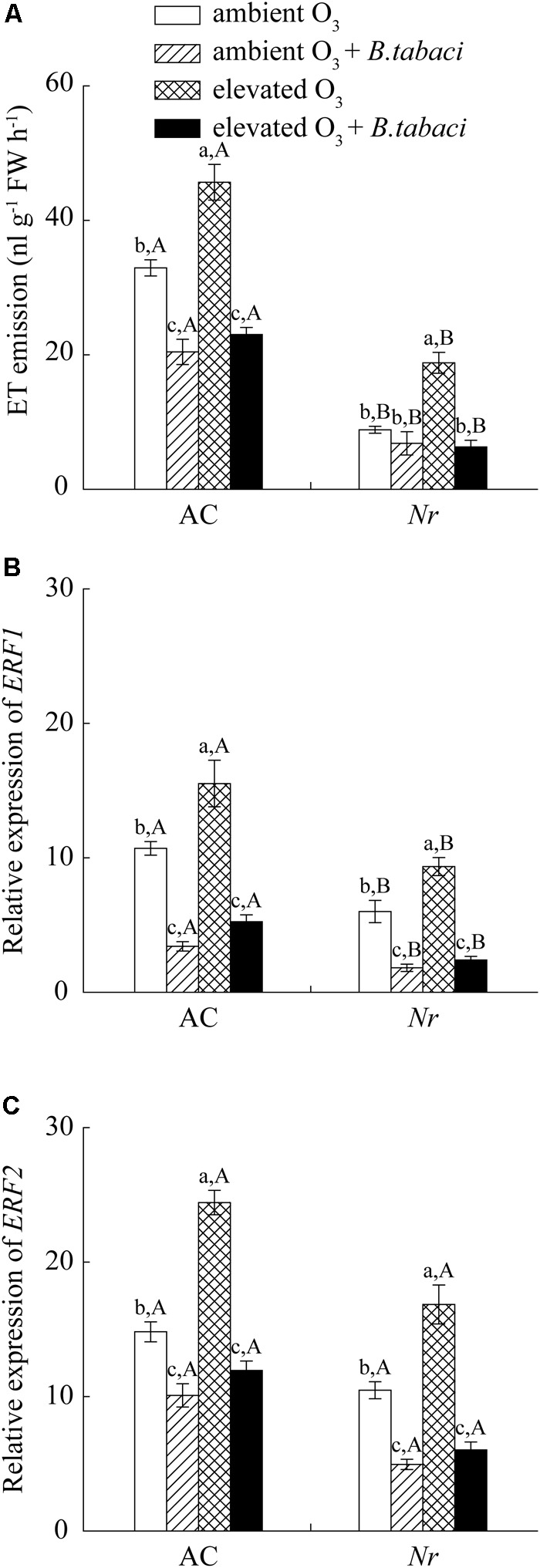

Elevated O3 significantly increased the emission of ET without B. tabaci infestation in AC plants, increasing from 33 to 44 nL g-1FW h-1. When infested by B. tabaci, elevated O3 had no effects on the emission of ET. B. tabaci infestation significantly decreased the ET emission by 38 % under ambient O3, and by 49% under elevated O3 in AC plants. Compared with AC plants, the ET emission was significantly lower in Nr plants regardless of B. tabaci infestation and O3 concentrations (Figure 6A). We also analyzed the ethylene-response factor 1 (ERF1) and ethylene-response factor 2 (ERF2), two down-stream genes of ET signaling pathway, and found that their expression was increased by elevated O3, and decreased by B. tabaci infestation in both tomato genotypes (Figures 6B,C).

FIGURE 6.

Ethylene emission and fold-change in the expression of related genes involved in the ET-dependent signaling pathway in two tomato genotypes grown under ambient O3 and elevated O3 with and without B. tabaci infestation. (A) ET emission. (B) ERF1. (C) ERF2. Each value represents the mean (±SE) of four OTCs (eight plants for each genotype per OTC). Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among the combinations of B. tabaci treatment and O3 concentrations within the same genotype. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between genotypes within the same O3 treatment and B. tabaci treatment.

O3-Induced Leaf Senescence Improved the N Nutrition of Tomato Plants

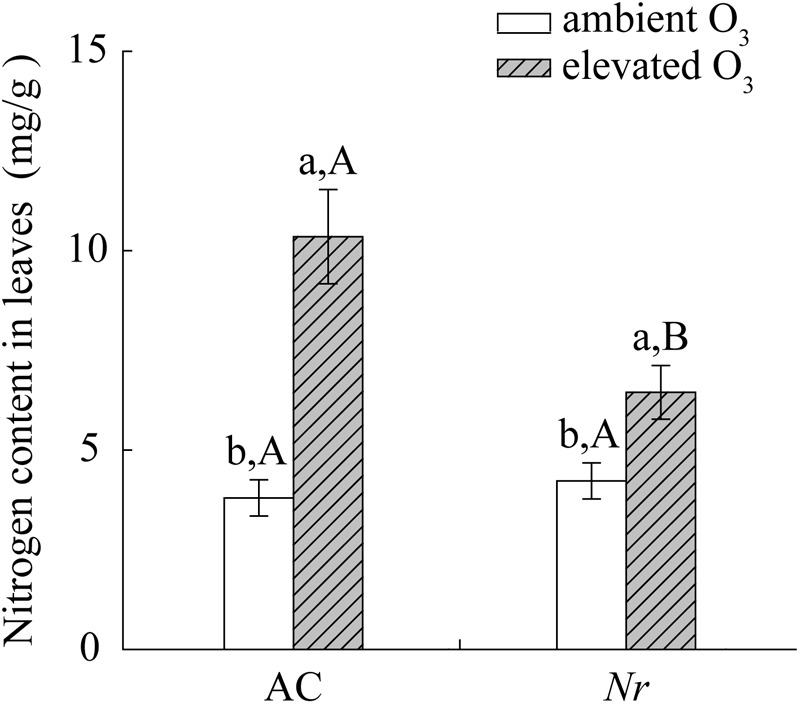

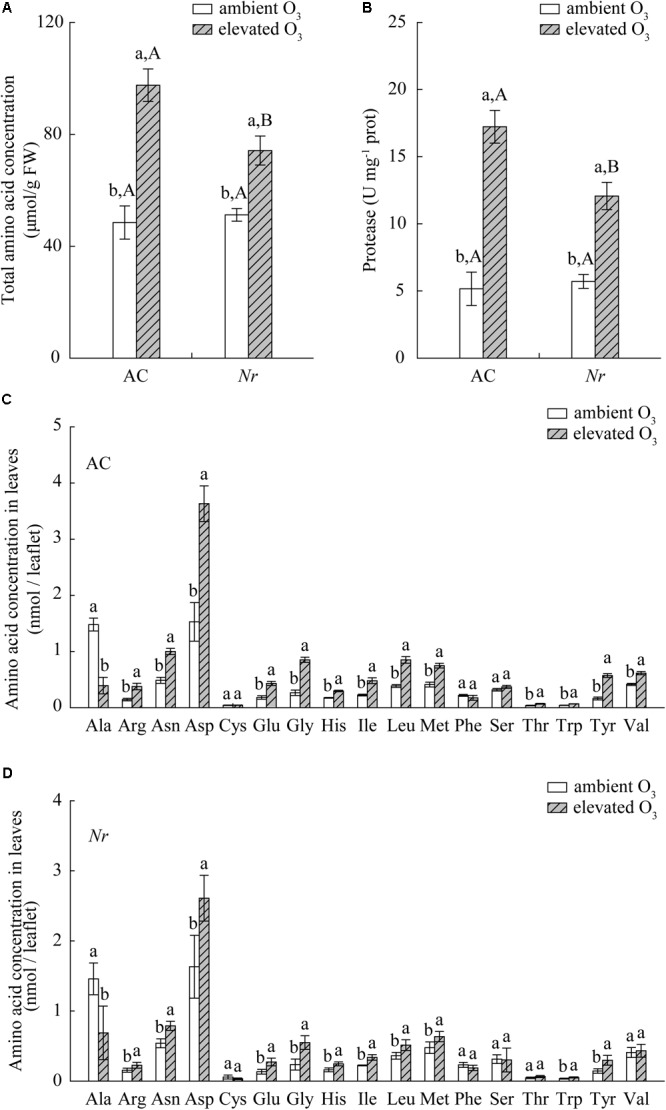

Elevated O3 significantly increased foliar nitrogen content, total amino acid content, and protease activity in AC and Nr plants, but the response was greater in AC plants (1.6-fold, 2.7-fold, and 2-fold) compared with Nr plants (1.3-fold, 1.5-fold, and 1.4-fold; Figures 7, 8A,B).

FIGURE 7.

Total nitrogen concentration for two tomato genotypes grown under ambient O3 and elevated O3 without B. tabaci infestation. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences between ambient O3 and elevated O3 within the same genotype. Different uppercase letters indicate significant differences between genotypes within the same O3 treatment.

FIGURE 8.

Total and individual amino acid concentration for two tomato genotypes grown under ambient O3 and elevated O3 without B. tabaci infestation. (A) Total amino acid concentration. (B) The activity of protease. (C) Individual amino acid concentration in AC plants. (D) Individual amino acid concentration in Nr plants. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences at P < 0.05.

A total of 17 individual amino acids in leaves were analyzed including essential and non-essential amino acids. Elevated O3 markedly increased the concentrations of 13 individual amino acids, including nine essential amino acids (Arg, His, Ile, Leu, Met, Thr, Trp, Tyr, and Val) and four non-essential amino acids (Asn, Asp, Glu, and Gly) in AC/H2O plants, and 11 individual amino acids including six essential amino acids (Arg, His, Ile, Leu, Met, Trp, and Tyr) and four non-essential amino acids (Asn, Asp, Glu, and Gly) in Nr/H2O plants. Furthermore, the increase in individual amino acids was greater in AC plants than in Nr plants (Figures 8C,D).

Discussion

Hormone-dependent signals can act both independently and interactively to modulate the plant response to climate change (elevated CO2 or O3) and insect infestation (Baier et al., 2005; Tamaoki, 2008; Erb et al., 2012; Zavala et al., 2013; Pellegrini et al., 2016). The hormone-mediated changes in host plant phenotypes under climate change can further affect the performance of herbivorous insects (Guo et al., 2014, 2017). Here, we report that O3, as a strong oxidative stressor, activates ET signaling pathway, which is involved in mediating O3-induced leaf senescence. Furthermore, leaf senescence under elevated O3 is associated with changes in plant quality, which has no effects on hormone-dependent defense but increases amino acid concentrations, and therefore increases the number of B. tabaci on wild-type plants. Compared with wild-type plants, O3-induced leaf senescence is mitigated in Nr plants, which dramatically reduces the beneficial effects of O3-induced leaf senescence on B. tabaci. Consequently, although ET signaling pathway is important in improving plant resistance to insect infestation under non-stress conditions (Louis et al., 2015), our results demonstrate that O3-induced stimulation of ET signaling pathway in plant that accelerates leaf senescence boosts B. tabaci infestation.

Ethylene emission is one of the most quickly responses to O3 exposure in host plants (Moeder et al., 2002; Gupta et al., 2005), and is correlated with plant sensitivity to O3 stress (Pellegrini et al., 2013; Vainonen and Kangasjärvi, 2015). Plants with mutation in ET signaling pathway are less sensitive to O3 exposure, and plants with ET overproduction are more sensitive to O3 exposure (Tamaoki et al., 2003). Our results also found that ET-overproducing AC/ACC plants were more sensitive, and ET insensitive AC/1-MCP plants were not sensitive to O3 exposure than wild-type AC/H2O plants. However, in contrast to an earlier study, ET-insensitive Nr plants exhibit a similar degree of O3-induced leaf lesions with wild-type Pearson plants under acute O3 fumigation with 200 ppb for 4 h (Castagna et al., 2007). In the current study, Nr plants exhibited lower tissue injury, lower ROS accumulation, and grew better than AC plants under chronic O3 exposure with 89 ppb for 21 days (Figure 2). It is likely that different fumigation regimes of O3 exposure may be important for the different function of NR receptor in regulating O3 sensitivity. Acute O3 exposure means that plants are fumigated with O3 concentration exceeding 120 ppb within a few hours, while chronic O3 exposure is daily peak concentration in the range of 40–120 ppb within several days (Long and Naidu, 2002). Many works suggest that acute and chronic O3 exposure induce different mechanisms (Kollist et al., 2007; Wittig et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2009). In soybean plants, chlorophyll fluorescence image indicates that acute O3 exposure causes small area reduction in photosynthetic capacity near the major vein by direct oxidative damage to PSII. Chronic O3 exposure depresses photosynthetic capacity around interveinal regions through affecting Rubisco (Chen et al., 2009). Stomatal movement is also different under acute and chronic O3 exposure. Acute O3 exposure induces a rapid stomatal closure and then recovers to an original rate of stomatal conductivity (Kollist et al., 2007). Chronic O3 exposure causes a continuous decline of stomatal conductivity (Kitao et al., 2009). Therefore, irrespective of acute O3 exposure, NR receptor is important for mediating plant sensitivity to chronic O3 exposure.

Ethylene signaling pathway can also regulate O3-induced cell death via cross-talking with other hormone signaling pathway, such as SA and JA signaling pathway. Early studies demonstrate that both ET and SA signaling pathways are activated in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) under acute O3 exposure (Moeder et al., 2002; Rao et al., 2002; Vahala et al., 2003). Furthermore, SA signaling pathway is requirement for O3-induced ET synthase, which regulates plant response to O3 exposure. In Arabidopsis double mutants crossing ET over-production eto3 with SA-deficient NahG plants, O3-induced ET emission and necrotic lesion are obviously reduced compared with these detected in eto3 mutants with O3 hyper-sensitive (Rao et al., 2002). In the current study, we also found that ET emission, SA content, ET-dependent ERF, and SA-dependent PR mRNA transcripts were significantly increased in tomato plants under chronic O3 exposure. In contrast to SA signaling pathway, JA signaling pathway is differently affected by acute and chronic O3 exposure. Acute O3 exposure initiates the JA signaling pathway, which is involved in regulating O3-induced cell death (Koch et al., 2000; Rao et al., 2000; Tuominen et al., 2004). Furthermore, experiments of JA-insensitive jasmonate resistant 1 and methyl jasmonate pretreatment demonstrate that JA inhibits the propagation of cell death via suppressing the SA and ET signaling pathway under acute O3 exposure (Rao et al., 2000; Tuominen et al., 2004). However, for chronic O3 exposure, our results were consistent with Cui et al. (2012), which had no effects on JA content and JA-synthase LOX and JA-dependent PI mRNA transcripts.

A direct role of ET signaling pathway in regulating abiotic stress-induced leaf premature senescence has been demonstrated. Experiments in maize show that a deficiency in the ET synthase inhibits drought-induced senescence, and the delayed drought-induced senescence in ET synthase mutants is complemented by spraying with ET precursor ACC (Young et al., 2004). Similar to drought-induced leaf senescence, the acceleration of leaf senescence under O3 exposure has indeed been correlated with enhanced ET production in beech trees (Nunn et al., 2005). We also found that ET insensitive AC/1-MCP and Nr/H2O plants delayed O3-induced leaf senescence and ET-overproducing AC/ACC plants exacerbated O3-induced leaf senescence (Figure 2). ET signal also involves secondary symplastic ROS accumulation in O3-exposure tomato plants, in which plant spraying with ET inhibitors accumulates less H2O2 under elevated O3 (Moeder et al., 2002). ROS can serve as a signal molecule to accelerate leaf senescence (Jing et al., 2008). For example, the Arabidopsis A-Fifteen (AAF) gene, the A. thaliana ortholog of sweet potato senescence-associated gene-SPA15, is involved in balancing the ROS homeostasis to regulate the age and dark-induced leaf senescence, in which leaf senescence is suppressed in aaf T-DNA insertion mutant and promoted in AAF over-expression plants (Chen et al., 2011). The regulation of AAF in leaf senescence is dependent on ethylene insensitive 2 (EIN2; Chen et al., 2011), which is an important positive regulator in ET signaling pathway (Wen et al., 2012). A recent study also shows that application of ET inhibitor 1-MCP inhibits ROS accumulation, and thus delays leaf senescence in soybean plants under high temperature stress (Djanaguiraman et al., 2011). It is accordance with current results that low ROS accumulation and alleviated leaf senescence in ET-insensitive AC/1-MCP and Nr/H2O plants (Figure 2). Thus, these suggest that ET signaling pathway is required in ROS accumulation and leaf senescence under elevated O3.

Leaf senescence, which changes plant nutrition and defense metabolisms, could be utilized by plant to regulate insect growth. There are two hypotheses to explain the effects of senescing leaves with the sign of yellowing on herbivores: (i) handicap signal hypothesis and (ii) nutrient re-translocation hypothesis. Hamilton and Brown (2001) propose the handicap signal hypothesis that senescing leaves with bright colors are detected as a warning signal of defensive commitment against autumn colonizing insect pests (Hamilton and Brown, 2001), which explains a strong preference of aphids to green leaves (Archetti and Leather, 2005). JA-dependent defense is important for regulating plant against B. tabaci infestation (Zarate et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014). However, B. tabaci infestation can suppress the effective JA-dependent defense via activating SA-dependent defense (Zhang et al., 2013). When infested with B. tabaci, the expression of JA-dependent VSP1 gene is decreased in Arabidopsis Col-0 plants, while is increased in Arabidopsis SA-deficient NahG and npr1 plants (Zhang et al., 2013). In the current study, B. tabaci infestation also significantly activated SA-dependent defense, but suppressed the JA and ET-dependent defense in tomato plants regardless of O3 concentrations. These results suggested that elevated O3 had little effect on phytohormone-dependent defensive responses to B. tabaci infestation. It is in accordance with those studies concerning the effect of abiotic stress on plant resistance against aphid infestation (O’Neill et al., 2010; Foyer et al., 2016; Pineda et al., 2016). For example, the accumulation of secondary defensive metabolites, i.e., glucosinolate, which is induced by Brevicoryne brassicae, was unaffected by different water status conditions in broccoli (Brassica oleracea) plants (Khan et al., 2011). Thus, it seems that our results are not supported by “handicap signal hypothesis.” Our data are consistent with the “nutrient re-translocation hypothesis,” that is, senescing leaves provide a better quality of nitrogenous food for sap-sucking insects (Holopainen and Peltonen, 2002; Holopainen et al., 2009), explaining higher number of aphids on senescing autumn leaves in B. pendula (Holopainen et al., 2009). It is widely accepted that leaf senescence causes the degradation of N storage proteins, which releases abundant free amino acids in leaves (Lim et al., 2007). Total amino acid contents increase in early senescing leaves of Prunus padus (Sandström, 2000). In Arabidopsis, the individual amino acid content, such as Leu, Ile, Tyr, and Arg, also increases during developmental leaf senescence (Diaz et al., 2005). For sap-sucking insects, N availability in host plants, especially amino acids, is positively correlated with sap-sucking insect development (Ponder et al., 2000; Nowak and Komo, 2010). Plants with higher amino acid content sustain more B. tabaci eggs and attract more B. tabaci for feeding (Crafts-Brandner, 2002). O3-induced leaf senescence improved individual and total amino acids in wild-type plants (Figure 8), which increased the population abundance of B. tabaci (Figure 3). Compared with wild-type plants, the lower amino acid content sustained lower population number of B. tabaci on Nr plants under elevated O3. Thus, these results indicate that the rise in leaf amino acid concentrations, which is caused by leaf senescence, is an important aspect of the improved population fitness of B. tabaci under elevated O3.

The population abundance of Q biotypes of B. tabaci was increased when fed foliage grown under elevated O3 in the current research. This finding coincides with early results showing that elevated O3 increases the population fitness of aphids (Holopainen and Kainulainen, 1997; Percy et al., 2002). However, this is in contrast with a previous study of tomato–B. tabaci interactions, in which the population fitness of B biotype of B. tabaci is reduced under elevated O3 (Cui et al., 2012). One possible explanation is that N levels of two genotypes of tomato plants are different under elevated O3, i.e., increased in AC plants but decreased in CM (Castlemart) plants. This is in agreement with previous reports of multiple variations in nutrient responses to O3 exposure existing among plant genotypes and/or species (Couture et al., 2014). Another explanation is that the response of B. tabaci to elevated O3 is dependent on the biotypes. Previous studies also support that Q biotype exhibits higher population fitness than B biotype, such as better feeding efficiency, greater reproductive ability, shorter development time, and greater tolerance to heat stress (Mahadav et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2013). Thus, our study suggests that elevated O3 may exacerbate intra-species competitions between different biotypes of B. tabaci.

Conclusion

Elevated O3 activates ET signaling pathway, which accelerates leaf senescence associated with decrease in biomass, photosynthesis, and increase in numbers of yellow leaves; however, the performance of B. tabaci on tomato plants is improved by increasing nitrogenous nutrition of O3-induced senescing leaves. This study has generated several significant findings. First, oxidative stress can accelerate leaf senescence via regulating endogenous ET signals. Second, our results support the “nutrient re-translocation hypothesis” that O3-induced senescing leaves with higher amino acid contents enhance the population fitness of B. tabaci. Finally, such changes suggest that tomato plants may suffer greater damage due to the interacting stress of direct O3-damage and additive infested by B. tabaci if tropospheric O3 levels increase continuously.

Author Contributions

HG, YS, and FG planned and designed the research. HG performed the experiments, conducted the fieldwork, and analyzed the data. CL provided tomato seeds. HY provided field support. HG wrote the first draft of the manuscript. YS and FG contributed to the subsequent manuscript development.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This project was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB11050400) and the National Nature Science Fund of China (No. 31370438).

References

- Ainsworth E. A., Yendrek C. R., Sitch S., Collins W. J., Emberson L. D. (2012). The effects of tropospheric ozone on net primary productivity and implications for climate change. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 63 637–661. 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042110-103829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archetti M. R., Leather S. (2005). A test of the coevolution theory of autumn colours: colour preference of Rhopalosiphum padi on Prunus padus. Oikos 110 339–343. 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2005.13656.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore M. R. (2005). Assessing the future global impacts of ozone on vegetation. Plant Cell Environ. 28 949–964. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01341.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baier M., Kandlbinder A., Golldack D., Dietz K. J. (2005). Oxidative stress and ozone: perception, signalling and response. Plant Cell Environ. 28 1012–1020. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2005.01326.x 24471507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castagna A., Ederli L., Pasqualini S., Mensuali-Sodi A., Baldan B., Donnini S., et al. (2007). The tomato ethylene receptor LE-ETR3 (NR) is not involved in mediating ozone sensitivity: causal relationships among ethylene emission, oxidative burst and tissue damage. New Phytol. 174 342–356. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02010.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C. P., Frank T. D., Long S. P. (2009). Is a short, sharp shock equivalent to long-term punishment? Contrasting the spatial pattern of acute and chronic ozone damage to soybean leaves via chlorophyll fluorescence imaging. Plant Cell Environ. 32 327–335. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01923.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F. J., Wu G., Ge F. (2004). Growth, development and reproduction of the cotton bollworm Helicoverpa armigera (Hübner) reared on milky grains of wheat grown in elevated CO2 concentration. Chin. Acta Entomol. Sin. 47 774–779. [Google Scholar]

- Chen G. H., Liu C. P., Chen S. C. G., Wang L. C. (2011). Role of ARABIDOPSIS A-FIFTEEN in regulating leaf senescence involves response to reactive oxygen species and is dependent on ETHYLENE INSENSITIVE2. J. Exp. Bot. 63 275–292. 10.1093/jxb/err278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper O. R., Parrish D. D., Ziemke J., Balashov N. V., Cupeiro M., Galbally I. E., et al. (2014). Global distribution and trends of tropospheric ozone: an observation-based review. Elem. Sci. Anth. 2:000029 10.12952/journal.elementa.000029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell T. E., Wood B. W., Ni X. (2009). Chlorotic feeding injury by the black pecan aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae) to pecan foliage promotes aphid settling and nymphal development. Environ. Entomol. 38 411–416. 10.1603/022.038.0214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottrell T. E., Wood B. W., Ni X. (2010). Application of plant growth regulators mitigates chlorotic foliar injury by the black pecan aphid (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Pest Manag. Sci. 66 1236–1242. 10.1002/ps.2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture J. J., Holeski L. M., Lindroth R. L. (2014). Long-term exposure to elevated CO2 and O3 alters aspen foliar chemistry across developmental stages. Plant Cell Environ. 37 758–765. 10.1111/pce.12195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture J. J., Lindroth R. L. (2012). Atmospheric change alters performance of an invasive forest insect. Glob. Change Biol. 18 3543–3557. 10.1111/gcb.12014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crafts-Brandner S. J. (2002). Plant nitrogen status rapidly alters amino acid metabolism and excretion in Bemisia tabaci. J. Insect Physiol. 48 33–41. 10.1016/S0022-1910(01)00140-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui H. Y., Sun Y. C., Su J. W., Ren Q., Li C. Y., Ge F. (2012). Elevated O3 reduces the fitness of Bemisia tabaci via enhancement of the SA-dependent defense of the tomato plant. Arthropod Plant Interact. 6 425–437. 10.1007/s11829-012-9189-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton R. (2006). Whitefly infestations: the Christmas invasion. Nature 443 898–900. 10.1038/443898a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Barro P. J., Liu S. S., Boykin L. M., Dinsdale A. B. (2011). Bemisia tabaci: a statement of species status. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 56 1–19. 10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz C., Purdy S., Christ A., Morot-Gaudry J. F., Wingler A., Masclaux-Daubresse C. (2005). Characterization of markers to determine the extent and variability of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. A metabolic profiling approach. Plant Physiol. 138 898–908. 10.1104/pp.105.060764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djanaguiraman M., Prasad P. V. V., Al-Khatib K. (2011). Ethylene perception inhibitor 1-MCP decreases oxidative damage of leaves through enhanced antioxidant defense mechanisms in soybean plants grown under high temperature stress. Environ. Exp. Bot. 71 215–223. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.12.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erb M., Meldau S., Howe G. A. (2012). Role of phytohormones in insect-specific plant reactions. Trends Plant Sci. 17 250–259. 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Expósito-Rodríguez M., Borges A. A., Borges-Pérez A., Pérez J. A. (2008). Selection of internal control genes for quantitative real-time RT-PCR studies during tomato development process. BMC Plant Biol. 8:131. 10.1186/1471-2229-8-131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foyer C. H., Rasool B., Davey J. W., Hancock R. D. (2016). Cross-tolerance to biotic and abiotic stresses in plants: a focus on resistance to aphid infestation. J. Exp. Bot. 67 2025–2037. 10.1093/jxb/erw079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gielen B., Löw M., Deckmyn G., Metzger U., Franck F., Heerdt C., et al. (2006). Chronic ozone exposure affects leaf senescence of adult beech trees: a chlorophyll fluorescence approach. J. Exp. Bot. 58 785–795. 10.1093/jxb/erl222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Sun Y., Li Y., Liu X., Zhang W., Ge F. (2014). Elevated CO2 decreases the response of the ethylene signaling pathway in Medicago truncatula and increases the abundance of the pea aphid. New Phytol. 201 279–291. 10.1111/nph.12484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Sun Y., Peng X., Wang Q., Harris M., Ge F. (2015). Up-regulation of abscisic acid signaling pathway facilitates aphid xylem absorption and osmoregulation under drought stress. J. Exp. Bot. 67 681–693. 10.1093/jxb/erv481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H., Wang S., Ge F. (2017). Effect of elevated CO2 and O3 on phytohormone-mediated plant resistance to vector insects and insect-borne plant viruses. Sci. China Life Sci. 60 816–825. 10.1007/s11427-017-9126-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P., Duplessis S., White H., Karnosky D. F., Martin F., Podila G. K. (2005). Gene expression patterns of trembling aspen trees following long-term exposure to interacting elevated CO2 and tropospheric O3. New Phytol. 167 129–142. 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2005.01422.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton W. D., Brown P. (2001). Autumn tree colours as a handicap signal. Proc. Biol. Sci. 268 1489–1493. 10.1098/rspb.2001.1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillstrom M. L., Vigue L. M., Coyle D. R., Raffa K. F., Lindroth R. L. (2010). Performance of the invasive weevil Polydrusus sericeus is influenced by atmospheric CO2 and host species. Agric. For. Entomol. 12 285–292. 10.1111/j.1461-9563.2010.00474.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holopainen J. K. (2002). Aphid response to elevated ozone and CO2. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 104 137–142. 10.1046/j.1570-7458.2002.01000.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holopainen J. K., Kainulainen P. (1997). Growth and reproduction of aphids and levels of free amino acids in Scots pine and Norway spruce in an open-air fumigation with ozone. Glob. Change Biol. 3 139–147. 10.1046/j.1365-2486.1997.00067.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holopainen J. K., Peltonen P. (2002). Bright autumn colours of deciduous trees attract aphids: nutrient retranslocation hypothesis. Oikos 99 184–188. 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2002.990119.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holopainen J. K., Semiz G., Blande J. D. (2009). Life-history strategies affect aphid preference for yellowing leaves. Biol. Lett. 5 603–605. 10.1098/rsbl.2009.0372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IPCC (2013). Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Website. Available at: http://www.ipcc.ch [accessed August 12 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- Jing H. C., Hebeler R., Oeljeklaus S., Sitek B., Stühler K., Meyer H. E., et al. (2008). Early leaf senescence is associated with an altered cellular redox balance in Arabidopsis cpr5/old1 mutants. Plant Biol. 10 85–98. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2008.00087.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kevany B. M., Tieman D. M., Taylor M. G., Cin V. D., Klee H. J. (2007). Ethylene receptor degradation controls the timing of ripening in tomato fruit. Plant J. 51 458–467. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03170.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. A. M., Ulrichs C., Mewis I. (2011). Water stress alters aphid-induced glucosinolate response in Brassica oleracea var. italic differently. Chemoecology 21 235–242. 10.1007/s00049-011-0084-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kitao M., Löw M., Heerdt C., Grams T. E., Häberle K. H., Matyssek R. (2009). Effects of chronic elevated ozone exposure on gas exchange responses of adult beech trees (Fagus sylvatica) as related to the within-canopy light gradient. Environ. Pollut. 157 537–544. 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch J. R., Creelman R. A., Eshita S. M., Seskar M., Mullet J. E., Davis K. R. (2000). Ozone sensitivity in hybrid poplar correlates with insensitivity to both salicylic acid and jasmonic acid. The role of programmed cell death in lesion formation. Plant Physiol. 123 487–496. 10.1104/pp.123.2.487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollist T., Moldau H., Rasulov B., Oja V., Rämma H., Hüve K., et al. (2007). A novel device detects a rapid ozone-induced transient stomatal closure in intact Arabidopsis and its absence in abi2 mutant. Physiol. Plant. 129 796–803. 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2006.00851.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama T. (2014). The roles of ethylene and transcription factors in the regulation of onset of leaf senescence. Front. Plant. Sci. 5:650. 10.3389/fpls.2014.00650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanahan M. B., Yen H. C., Giovannoni J., Klee H. J. (1994). The Never Ripe mutation blocks ethylene perception in tomato. Plant Cell 6 521–530. 10.2307/3869932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R., Weldegergis B. T., Li J., Jung C., Qu J., Sun Y., et al. (2014). Virulence factors of geminivirus interact with MYC2 to subvert plant resistance and promote vector performance. Plant Cell 26 4991–5008. 10.1105/tpc.114.133181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim P. O., Kim H. J., Gil N. H. (2007). Leaf senescence. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 58 115–136. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Preisser E. L., Chu D., Pan H., Xie W., Wang S., et al. (2013). Multiple forms of vector manipulation by a plant-infecting virus: Bemisia tabaci and tomato yellow leaf curl virus. J. Virol. 87 4929–4937. 10.1128/JVI.03571-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S. P., Naidu S. L. (2002). Effects of oxidants at the biochemical, cell and physiological levels, with particular reference to ozone. Air Pollut. Plant Life 2 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Louis J., Basu S., Varsani S., Castano-Duque L., Jiang V., Williams P. W., et al. (2015). Ethylene contributes to maize insect resistance1-mediated maize defense against the phloem sap-sucking corn leaf aphid. Plant Physiol. 169 313–324. 10.1104/pp.15.00958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Løvdal T., Lillo C. (2009). Reference gene selection for quantitative real-time PCR normalization in tomato subjected to nitrogen, cold, and light stress. Anal. Biochem. 387 238–242. 10.1016/j.ab.2009.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwików A., Cieśla A., Kasprowicz-Maluśki A., Mituła F., Tajdel M., Gałgański Ł., et al. (2014). Arabidopsis protein phosphatase 2C ABI1 interacts with type I ACC synthases and is involved in the regulation of ozone-induced ethylene biosynthesis. Mol. Plant 7 960–976. 10.1093/mp/ssu025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwików A., Kierzek D., Gallois P., Zeef L., Sadowski J. (2009). Gene expression profiling of ozone-treated Arabidopsis abi1td insertional mutant: protein phosphatase 2C ABI1 modulates biosynthesis ratio of ABA and ethylene. Planta 230 1003–1017. 10.1007/s00425-009-1001-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadav A., Kontsedalov S., Czosnek H., Ghanim M. (2009). Thermotolerance and gene expression following heat stress in the whitefly Bemisia tabaci B and Q biotypes. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 39 668–676. 10.1016/j.ibmb.2009.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manninen A. M., Holopainen T., Lyytikäinen-Saarenmaa P., Holopainen J. K. (2000). The role of low-level ozone exposure and mycorrhizas in chemical quality and insect herbivore performance on Scots pine seedlings. Glob. Change Biol. 6 111–121. 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2000.00290.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mascia T., Santovito E., Gallitelli D., Cillo F. (2010). Evaluation of reference genes for quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction normalization in infected tomato plants. Mol. Plant Pathol. 11 805–816. 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2010.00646.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller J. D., Arteca R. N., Pell E. J. (1999). Senescence-associated gene expression during ozone-induced leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 120 1015–1024. 10.1104/pp.120.4.1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeder W., Barry C. S., Tauriainen A. A., Tauriainen B. C., Tuomainen J., Utriainen M., et al. (2002). Ethylene synthesis regulated by biphasic induction of 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid synthase and 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid oxidase genes is required for hydrogen peroxide accumulation and cell death in ozone-exposed tomato. Plant Physiol. 130 1918–1926. 10.1104/pp.009712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak H., Komo E. (2010). How aphids decide what is good for them: experiments to test aphid feeding behaviour on Tanacetum vulgare (L.) using different nitrogen regimes. Oecologia 163 973–984. 10.1007/s00442-010-1652-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunn A. J., Reiter I. M., Häberle K.-H., Langebartels C., Bahnweg G., Pretzsch H., et al. (2005). Response patterns in adult forest trees to chronic ozone stress: identification of variations and consistencies. Environ. Pollut. 136 365–369. 10.1016/j.envpol.2005.01.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohara T., Akimoto H., Kurokawa J. I., Horii N., Yamaji K., Yan X., et al. (2007). An Asian emission inventory of anthropogenic emission sources for the period 1980–2020. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7 4419–4444. 10.5194/acp-7-4419-2007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill B. F., Zangerl A. R., Dermody O., Bilgin D. D., Casteel C. L., Zavala J. A., et al. (2010). Impact of elevated levels of atmospheric CO2 and herbivory on flavonoids of soybean (Glycine max Linnaeus). J. Chem. Ecol. 36 35–45. 10.1007/s10886-009-9727-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegadaraju V., Knepper C., Reese J., Shah J. (2005). Premature leaf senescence modulated by the Arabidopsis PHYTOALEXIN DEFICIENT4 gene is associated with defense against the phloem-feeding green peach aphid. Plant Physiol. 139 1927–1934. 10.1104/pp.105.070433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini E., Trivellini A., Campanella A., Francini A., Lorenzini G., Nali C., et al. (2013). Signaling molecules and cell death in Melissa officinalis plants exposed to ozone. Plant Cell Rep. 32 1965–1980. 10.1007/s00299-013-1508-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini E., Trivellini A., Cotrozzi L., Vernieri P., Nali C. (2016). “Involvement of phytohormones in plant responses to ozone,” in Plant Hormones under Challenging Environmental Factors ed. Ahammed G. (Dordrecht: Springer press; ) 215–245. [Google Scholar]

- Peltonen P. A., Vapaavuori E., Heinonen J., Julkunen-tiitto R., Holopainen J. K. (2010). Do elevated atmospheric CO2 and O3 affect food quality and performance of folivorous insects on silver birch? Glob. Change Biol. 16 918–935. 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02073.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Percy K. E., Awmack C. S., Lindroth R. L., Kubiske M. E. (2002). Altered performance of forest pests under atmospheres enriched by CO2 and O3. Nature 420 403–407. 10.1038/nature01028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pineda A., Pangesti N., Soler R., van Dam N. M., van Loon J. J., Dicke M. (2016). Negative impact of drought stress on a generalist leaf chewer and a phloem feeder is associated with, but not explained by an increase in herbivore-induced indole glucosinolates. Environ. Exp. Bot. 123 88–97. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2015.11.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ponder K. L., Pritchard J., Harrington R., Bale J. S. (2000). Difficulties in location and acceptance of phloem sap combined with reduced concentration of phloem amino acids explain lowered performance of the aphid Rhopalosiphum padi on nitrogen deficient barley. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 97 203–210. 10.1046/j.1570-7458.2000.00731.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu K., Li Z., Yang Z., Chen J., Wu S., Zhu X., et al. (2015). EIN3 and ORE1 accelerate degreening during ethylene-mediated leaf senescence by directly activating chlorophyll catabolic genes in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 11:e1005399. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao M. V., Lee H. I., Creelman R. A., Mullet J. E., Davis K. R. (2000). Jasmonate perception desensitizes O3-induced salicylic acid biosynthesis and programmed cell death in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 12 1633–1646. 10.1105/tpc.12.9.1633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao M. V., Lee H. I., Davis K. R. (2002). Ozone-induced ethylene production is dependent on salicylic acid, and both salicylic acid and ethylene act in concert to regulate ozone-induced cell death. Plant J. 32 447–456. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01434.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandström J. (2000). Nutritional quality of phloem sap in relation to host plant-alternation in the bird cherry-oat aphid. Chemoecology 10 17–24. 10.1007/s000490050003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaoki M. (2008). The role of phytohormone signaling in ozone-induced cell death in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 3 166–174. 10.4161/psb.3.3.5538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamaoki M., Matsuyama T., Kanna M., Nakajima N., Kubo A., Aono M., et al. (2003). Differential ozone sensitivity among Arabidopsis accessions and its relevance to ethylene synthesis. Planta 216 552–560. 10.1007/s00425-002-0894-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuominen H., Overmyer K., KeinaÈnen M., Kollist H., Kangasjärvi J. (2004). Mutual antagonism of ethylene and jasmonic acid regulates ozone-induced spreading cell death in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 39 59–69. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02107.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vainonen J. P., Kangasjärvi J. (2015). Plant signalling in acute ozone exposure. Plant Cell Environ. 38 240–252. 10.1111/pce.12273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. T., Yang C. Y., Chen Y. T., Lin Y., Shaw J. F. (2004). Characterization of senescence-associated proteases in postharvest broccoli florets. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 42 663–670. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2004.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen X., Zhang C., Ji Y., Zhao Q., He W., An F., et al. (2012). Activation of ethylene signaling is mediated by nuclear translocation of the cleaved EIN2 carboxyl terminus. Cell Res. 22 1613–1616. 10.1038/cr.2012.145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White T. C. R. (2015). Senescence-feeders: a new trophic sub-guild of insect herbivores. J. Appl. Entomol. 139 11–22. 10.1111/jen.12147 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson J. Q., Lanahan M. B., Yen H. C., Giovannoni J. J., Klee H. J. (1995). An ethylene-inducible component of signal transduction encoded by never-ripe. Science 270 1807–1809. 10.1126/science.270.5243.1807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson S., Davies W. J. (2009). Ozone suppresses soil drying-and abscisic acid (ABA)-induced stomatal closure via an ethylene-dependent mechanism. Plant Cell Environ. 32 949–959. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01970.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittig V. E., Ainsworth E. A., Long S. P. (2007). To what extent do current and projected increases in surface ozone affect photosynthesis and stomatal conductance of trees? A meta-analytic review of the last 3 decades of experiments. Plant Cell Environ. 30 1150–1162. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01717.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T. E., Meeley R. B., Gallie D. R. (2004). ACC synthase expression regulates leaf performance and drought tolerance in maize. Plant J. 40 813–825. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02255.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarate S. I., Kempema L. A., Walling L. L. (2007). Silverleaf whitefly induces salicylic acid defenses and suppresses effectual jasmonic acid defenses. Plant Physiol. 143 866–875. 10.1104/pp.106.090035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zavala J. A., Nabity P. D., DeLucia E. H. (2013). An emerging understanding of mechanisms governing insect herbivory under elevated CO2. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 58 79–97. 10.1146/annurev-ento-120811-153544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P. J., Li W. D., Huang F., Zhang J. M., Xu F. C., Lu Y. B. (2013). Feeding by whiteflies suppresses downstream jasmonic acid signaling by eliciting salicylic acid signaling. J. Chem. Ecol. 39 612–619. 10.1007/s10886-013-0283-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Luan J. B., Qi J. F., Huang C. J., Li M., Zhou X. P., et al. (2012). Begomovirus–whitefly mutualism is achieved through repression of plant defences by a virus pathogenicity factor. Mol. Ecol. 21 1294–1304. 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05457.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]