Abstract

Background

The aims of this study were to determine the extent of workplace bullying perceptions among the employees of a Faculty of Medicine, evaluating the variables considered to be associated, and determining the effect of workplace bullying perceptions on their psychological symptoms evaluated by the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI).

Methods

This cross-sectional study was performed involving 355 (88.75%) employees.

Results

Levels of perceived workplace bullying were found to increase with the increasing scores for BSI and BSI sub-dimensions of anxiety, depression, negative self, somatization, and hostility (all p < 0.001). One point increase in the workplace bullying perception score was associated with a 0.47 point increase in psychological symptoms evaluated by BSI. Moreover, the workplace bullying perception scores were most strongly affected by the scores of anxiety, negative self, depression, hostility, and somatization (all p < 0.05).

Conclusion

The present results revealed that young individuals, divorced individuals, faculty members, and individuals with a chronic disease had the greatest workplace bullying perceptions with our study population. Additionally, the BSI, anxiety, depression, negative self, somatization, and hostility scores of the individuals with high levels of workplace bullying perceptions were also high.

Keywords: negative acts questionnaire, psychological symptoms, workplace bullying

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization defines violence as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation” [1]. Another issue that can be considered to be violence and is as important as the definition of violence is the perception of violence. Some people regard struggled attitudes or behaviors as violent, while others do not. Thus, people who do not consider such behaviors and attitudes to be violent give these behaviors and attitudes legitimacy. The specific behaviors that are considered to be violent in the workplace vary according to the employees' cultural and religious structures and personality types [2]. Physical violence in the workplace (e.g., homicides, attacks, and beating) and psychological violence (e.g., workplace bullying, mobbing, and harassment) affect all categories of workers in nearly all sectors [3].

The International Labor Office defines workplace bullying as offensive behavior that is repeated over time and manifested as vindictive, cruel, or malicious attempts to humiliate or undermine an individual or group of employees [3]. Although the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM V) indicate two conditions (post-traumatic stress disorder and adjustment disorder), not necessarily work-related, that are directly related to stress, the mobbing syndrome has not been clearly identified [4], [5]. The health sector is particularly at a high risk of workplace bullying due to the fundamental characteristics of the services delivered and the work environment of this sector. The negative consequences of widespread violence in the health care sector include workers' decisions to leave the health profession and deleterious effects on the quality of the health services provided. These consequences can result in reductions in the health services available to the general population and increases in the costs of health care. Health workers are already a scare resource, and if they abandon their profession due to the threat of violence, equal access to primary health care will be threatened in developing countries [3].

Workplace bullying that is encountered in the workplace negatively affects people's professional and social lives (i.e., resignation, dismissal, and loss of income because of frequently using sick leave or receive reports) [6] and their health. Different physical, mental, and psychosomatic symptoms can be observed among individuals who have been exposed to workplace bullying. These symptoms include the following: (1) physical disorders including chronic fatigue, gastrointestinal disorders, excessive weight gain or weight loss, insomnia, various pain syndromes, deterioration in the immune system function, and increased use of alcohol, drugs, and cigarettes; (2) mental disorders including depression, burnout, emotional emptiness, feelings that life is meaninglessness, anxiety, loss of motivation, loss of enthusiasm, apathy, hypomania, and adjustment disorder; and (3) behavioral disorders including irritability, risky behavior, loss of concentration, forgetfulness, emotional outbursts, roughness, exaggerated sensibility to external stimuli, lack of emotion, family problems, divorce, and suicide [6], [7], [8], [9].

Researches on workplace violence have shown that workplace bullying is currently more dangerous than physical violence. Moreover, these researches have shown that workplace bullying has become a major health and safety issue for employees in the workplace [1], [3], [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Recently, workplace bullying has been discussed in terms of psychosocial risk factors in the workplace. Thus, this study was designed to examine workplace bullying in the risky area of health care. The aims of this study were to determine the extent of workplace bullying perceptions among the employees of a University Faculty of Medicine, evaluating the variables considered to be associated, and determining the effect of workplace bullying perceptions on their psychological symptoms evaluated by the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI).

2. Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study was performed among the employees of the Faculty of Medicine at a university located in the Central Anatolia Region in 2012. The study was based on the variables of workplace bullying perceptions and psychological symptoms evaluated by the BSI. A theoretical model was designed in the study assuming that the perception of workplace bullying may affect psychological symptoms. This theoretical model was tested on causality level by the structural equation model (SEM).

The study universe consisted of 1,433 individuals who worked in the Faculty of Medicine. This research was intended to be performed on a sample size of 400 individuals. The current employees were layered according to their professions and departments (considering their titles and tasks). The individuals included in the sample were systematically selected from a list of existing employees who met the research criteria. The total number of participants was 355 (88.75% response rate) (Table 2). A questionnaire form was prepared for the study purposed. The questionnaire included questions about sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age, education, marital status, having a child, profession) and some factors possibly related to the workplace bullying [administrative tasks (administrative tasks were interpreted in two manners: working in managerial positions and working in professional capacities), working time in the profession (seniority), working time in the current workplace, weekly working time, working department, general economic status according to their own evaluations, workplace changes, chronic diseases, and mental diseases], and questions of the Workplace Bullying Scale (WBS) and BSI.

Table 2.

Workplace bullying perception scores of the research group and the results of the statistical analyses according to characteristics related to occupation and business

| Characteristics related to occupation or business | n (%) | Workplace bullying perception scores |

Statistical analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (minimum–maximum) | z/KW; p | ||

| Profession / Title / Task | |||

| Faculty member (0) | 61 (17.2) | 37.0 (22–109) | 19.949; 0.001 |

| Research assistant (1) | 64 (18.0) | 43.5 (22–72) | |

| Nurse (2) | 124 (34.9) | 40.0 (22–93) | |

| Administrative staff (3) | 73 (20.6) | 34.0 (22–95) | |

| Manager (4) | 33 (9.3) | 32.0 (22–74) | |

| Multiple comparison | (0-1) p = 0.016; (1-3) p = 0.000; (1-4) p = 0.000; | ||

| (2-3) p = 0.013; (2-4) p = 0.009 | |||

| Task | |||

| Academic | 125 (35.2) | 41.0 (22–109) | –2.078; 0.038 |

| Administrative | 230 (64.8) | 37.0 (22–95) | |

| Administrative task | |||

| No | 315 (88.7) | 39 (22–109) | –2.684; 0.007 |

| Yes | 40 (11.3) | 35 (22–64) | |

| Working time in the profession (seniority) (month) | |||

| 0–59 (0) | 115 (32.4) | 44 (22–109) | 25.478; 0.000 |

| 60–160 (1) | 117 (33.0) | 38 (22–82) | |

| ≥ 161 (2) | 123 (34.6) | 35 (22–93) | |

| Multiple comparison | (0-1) p = 0.038; (0-2) p = 0.000; (1-2) p = 0.005 | ||

| Working time in the current workplace (month) | |||

| 0–36 (0) | 128 (36.1) | 43.0 (22–109) | 19.534; 0.000 |

| 37–125 (1) | 108 (30.4) | 39.5 (23–82) | |

| ≥ 126 (2) | 119 (33.5) | 35.0 (22–93) | |

| Multiple comparison | (0-2) p = 0.000; (1-2) p = 0.003 | ||

| Weekly working time (hour) | |||

| ≤ 40 (0) | 210 (59.2) | 35.5 (22–109) | 14.606; .001 |

| 41–50 (1) | 86 (24.2) | 42.0 (24–81) | |

| ≥ 51 (2) | 59 (16.6) | 43.0 (22–92) | |

| Multiple comparison | (0-1) p = 0.001; (0-2) p = 0.004 | ||

| Working department | |||

| Internal sciences | 148 (41.7) | 39.0 (22–95) | 7.301; 0.063 |

| Surgical sciences | 119 (33.5) | 40.0 (22–93) | |

| Basic medical sciences | 14 (3.9) | 42.5 (28–79) | |

| Other | 74 (20.8) | 34.0 (22–109) | |

| The status of workplace change along working life | |||

| No | 156 (44) | 39 (22–95) | –0.503; 0.615 |

| Yes | 199 (56) | 38 (22–109) | |

| Chronic diseases | |||

| No | 305 (86) | 38 (22–95) | –1.556; 0.120 |

| Yes | 50 (14) | 40 (24–109) | |

| Mental diseases | |||

| No | 331 (93) | 38.0 (22–95) | –0.711; 0.477 |

| Yes | 24 (7) | 42.5 (22–109) | |

| Total | 355 (100) | 38 (22–109) | |

The WBS was used in this study for the assessment of workplace bullying perception levels of employees. The Negative Acts Questionnaire was developed by Einarsen and Raknes (1997) and adapted by Einarsen and Hoel (2001) [13], [14]. A study of the validity and reliability of the Turkish version was performed by Aydın and Öcel (2009) [15]. Aydın and Öcel did not directly translate the name of the scale into Turkish. These authors believed that the original name of the scale would cause misunderstandings regarding the properties that the scale aims to measure. Thus, these authors used “Workplace Bullying Scale” as the title. The scale consists of 22 five-point Likert type (scored from 1 to 5) items. The minimum score possible on this scale is 22, and the maximum score is 110. This scale does not have a cut-off. The frequency of workplace bullying score was obtained by collecting the marks for each scale item [15]. In this study, the scores derived from the WBS were expressed as workplace bullying perception score. In our research, the Cronbach α value for the WBS was 0.933.

The BSI was used in this study for the assessment of the psychological symptoms considered to be associated with workplace bullying perception. The BSI was developed by Derogatis (1992). It is a self-report symptom inventory that was designed to reflect the psychological symptoms. It is a brief form of the SCL-90 [16] and consists of 53 items. It has also been used in research analyzing the relationship between immune system functioning and stress because this scale is sufficient for measuring stress-related psychological symptoms. The BSI is a self-administered scale that is rated on a five-point Likert scale that ranges from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). The standardization, validity, and reliability of the Turkish version of this instrument were performed by Şahin and Durak (1994). The BSI consists of the following five sub-dimensions: Anxiety, Depression, Somatization, Hostility, and Negative Self. The minimum score on this scale is 0, and the maximum score is 212. This scale does not have a cut-off point. Higher scores indicate more severe psychological symptoms [17], [18]. In our research, the Cronbach α for the BSI was 0.974.

2.1. Study approval

This study was approved by the ethical committee of the university (Date: 09.05.2012, No: 2012/111). Furthermore, approval from the dean of the University Faculty of Medicine was separately obtained (Date: 15.05.2012, No: 3418-4540). The sample group was informed about the research, and an oral consent was obtained from each participant.

2.2. Limitations of the study

This study was based on employees' perceptions of workplace bullying. Thus, the real frequency of workplace bullying at this workplace could not be determined. Individuals with associate's degrees or higher levels of education were included in the study to measure workplace bullying perceptions as accurately as possible. No groups that worked outside of the health care field were included; thus, comparisons across employment fields could not be made in this study. The workplace bullying perception and psychological symptoms measured in the study were limited to the scales' items.

2.3. Statistical analyses

The data were evaluated using the SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) and AMOS 22 (Meadville, PA, USA) software programs. Statistical analysis was performed using Mann Whitney U, Kruskal–Wallis, and Spearman correlation tests. SEM was used to determine the effect of workplace bullying perception on psychological symptoms. The indexes for SEM analysis were assessed according to the following values: x2/sd of between 2 to 5 provides a good fit, RMSEA values ≤ 0.05 indicate excellent fit, GFI and AGFI values ≥ 0.90 indicate good fit, and it is generally accepted that NFI and CFI values ≥ 0.90 indicate excellent fit [19], [20], [21]. The level of significance was taken as p < 0.05 in all statistical analyses.

3. Results

The study group consisted of 238 (67%) men and 117 (33%) women. The mean age was 33.7 ± 8.7 (min: 20, max: 63) years. A total of 142 (40%) participants had undergraduate degrees, 204 (57.5%) were married, and 195 (54.9%) did not have children. Furthermore, 175 (49.3%) employees stated that their general economic levels were medium in their evaluations. Across all 355 participants, the mean workplace bullying perception score was 42.24 ± 15.52 (median: 38). The lowest and highest scores received by the employees on the applied scale were 22 and 109 points, respectively. The scores for perceptions of workplace bullying were higher among the 20–29-years-old age group and employees without children (each p < 0.05). Table 1 summarizes the employees' workplace bullying perception score distributions according to some of the sociodemographic characteristics and summarizes the results of the statistical analyses.

Table 1.

Workplace bullying perception scores of the research group and the statistical analyses results according to some of the sociodemographic characteristics

| Sociodemographic characteristics | n (%) | Workplace bullying perception scores |

Statistical analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (minimum–maximum) | z/KW; p | ||

| Sex | |||

| Men | 238 (67.0) | 38 (22–109) | –0.636; 0.525 |

| Women | 117 (33.0) | 38 (22–92) | |

| Age group | |||

| 20–29 (0) | 139 (39.2) | 44 (22–109) | 36.190; 0.000 |

| 30–39 (1) | 140 (39.4) | 38 (22–93) | |

| 40–49 (2) | 50 (14.1) | 31 (22–93) | |

| ≥ 50 (3) | 26 (7.3) | 35 (25–62) | |

| Multiple Comparison | (0-1) p = 0.034; (0-2) p = 0.000 | ||

| (0-3) p = 0.006; (1-2) p = 0.002 | |||

| Educational level | |||

| Associate degree | 74 (20.8) | 35 (22–95) | 4.314; 0.229 |

| Undergraduate | 142 (40.0) | 39 (22–109) | |

| Master's degree | 40 (11.3) | 41 (22–93) | |

| Doctorate | 99 (27.9) | 40 (22–93) | |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 204 (57.5) | 38 (22–93) | –1.298; 0.194 |

| Single | 151 (42.5) | 40 (22–109) | |

| The status of having children | |||

| No | 195 (54.9) | 41 (22–109) | –2.778; 0.005 |

| Yes | 160 (45.1) | 37 (22–93) | |

| General economic status | |||

| Good | 153 (43.1) | 38 (22–95) | 2.012; 0.366 |

| Medium | 175 (49.3) | 40 (22–109) | |

| Poor | 27 (7.6) | 41 (22–88) | |

| Total | 355 (100) | 38 (22–109) | |

A total of 124 (34.9%) participants were nurses, 123 (34.6%) of the employees had been working for 161 months. Additionally, 128 (36.1%) of those in the study group had been working in their institutions for 0–36 months, 210 (59.2%) participants worked for 40 hours per week or less, and 148 (41.7%) were working in internal medicine departments. Fifty (14.1%) employees had been diagnosed with a chronic disease, and 24 (6.8%) had been diagnosed with a mental illness. Forty-nine (13.8%) participants in the study group were taking a drug continuously. The workplace bullying perception scores were higher among the research assistants, the employees without administrative tasks, the employees who had worked in their profession for 0–59 months, the employees who had worked in the institution for 0–36 months, and the employees who worked 51 hours or more each week (all p < 0.05). The employees' workplace bullying perception score distributions according to profession and work-related characteristics and the results of the statistical analyses are given in Table 2.

Across the entire study population of 355 participants, the lowest BSI score was 0, and the highest score was 188. The mean BSI score was 37.02 ± 35.02 (median: 27). The mean anxiety sub-dimension score was 7.88 ± 8.90. The mean depression sub-dimension score was 9.82 ± 9.52. The mean negative self sub-dimension score was 7.96 ± 8.43. The mean somatization sub-dimension score was 4.56 ± 5.20. The mean hostility sub-dimension score was 6.78 ± 5.65. The workplace bullying perception scores, BSI scores, and the correlation coefficients from the BSI sub-dimensions are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Workplace bullying perception scores, brief symptom inventory scores, and the correlation among the brief symptom inventory sub-dimensions

| Correlations (Spearman's rhos) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Points | Workplace bullying perception score | Brief symptom inventory score | Anxiety | Depression | Negative self | Somatization | Hostility |

| Workplace bullying perception score | 1.000 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Brief symptom inventory Scores | 0.536∗ | 1.000 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Anxiety | 0.503∗ | 0.957∗ | 1.000 | – | – | – | – |

| Depression | 0.456∗ | 0.939∗ | 0.875∗ | 1.000 | – | – | – |

| Negative self | 0.528∗ | 0.932∗ | 0.883∗ | 0.845∗ | 1.000 | – | – |

| Somatization | 0.375∗ | 0.830∗ | 0.779∗ | 0.761∗ | 0.702∗ | 1.000 | – |

| Hostility | 0.561∗ | 0.892∗ | 0.825∗ | 0.767∗ | 0.810∗ | 0.683∗ | 1.000 |

* p < 0.001.

In the present study, levels of perceived workplace bullying were found to increase with the increasing scores for the BSI and BSI sub-dimensions of anxiety, depression, negative self, somatization, and hostility (all p < 0.001). Of the total variance in the workplace bullying perception scores, 31% (r2 = 0.31) was explained by hostility scores, 28% (r2 = 0.28) by BSI scores, 27% (r2 = 0.27) by negative self scores, 25% (r2 = 0.25) by anxiety scores, 20% (r2 = 0.20) by depression scores, and 14% by (r2 = 0.24) somatization scores.

SEM was used in the study to determine the effects of independent variables on workplace bullying perception and the effects of workplace bullying perception on psychological symptoms (Table 4).

Table 4.

Path coefficients of the revised structural equation model estimating determinants of the research group's workplace bullying perception

| Path | Standardized β | S.E. | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | → | Workplace bullying perception score | −0.317 | 0.088 | −6.484 | < 0.001 |

| Being Divorced | → | Workplace bullying perception score | 0.100 | 4.666 | 2.036 | 0.042 |

| Chronic Diseases | → | Workplace bullying perception score | 0.138 | 2.219 | 2.813 | 0.005 |

| Being a faculty member | → | Workplace bullying perception score | 0.152 | 1.616 | 3.099 | 0.002 |

| Workplace bullying perception score | → | BSI | 0.466 | 0.015 | 9.272 | < 0.001 |

BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory.

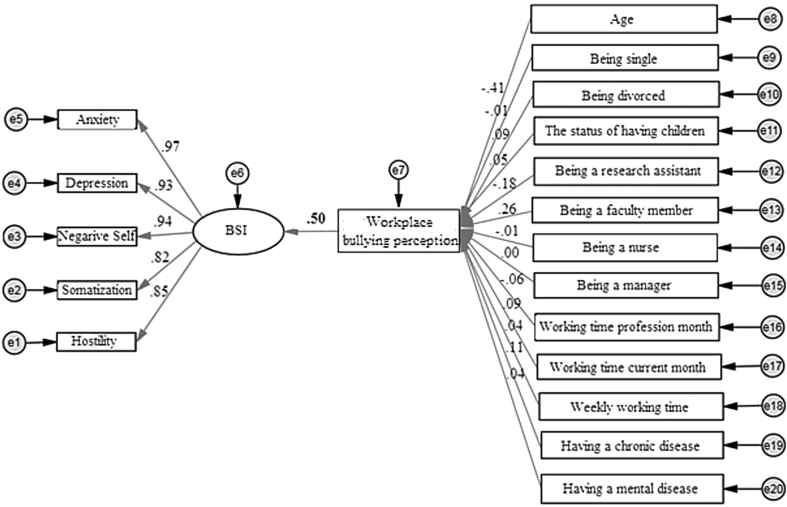

The BSI sub-dimensions and workplace bullying perception included in the model proposed with this study were taken as the observed variables, while the BSI was accepted as the latent variable. The 13 personal and professional characteristics of employees were examined as the explanatory variables in the model (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The initial structural equation model identifying determinants of the research group's workplace bullying perception. BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory.

In the initial model, the variables of being single (t = −0.267; p = 0.789), having a child (t = 1.112; p = 0.266), being a nurse (t = −0.201; p = 0.840), administrative tasks (t = 0.013; p = 0.990), working time in the profession (seniority) (t = −1.296; p = 0.195), working time in the current workplace (t = 1.948; p = 0.051), mental diseases (t = 0.830; p = 0.406), and weekly working time (t = 0.945; p = 0.345) were not significantly affected from the workplace bullying perception scores (Fig. 1). It can be also showed that the goodness-of-fit indexes for initial model indicated that the model was not within the specified limits of acceptability (χ2/df = 18.692, p = 0.000, GFI = 0.543, AGFI = 0.429, NFI = 0.429, CFI = 0.441, RMSEA = 0.224). The independent variables that were proven to be non-significant in the initial model and the variable of being research assistant were excluded one by one from analysis to achieve higher goodness-of-fit values and higher compatibility of the model to the data by examining the modification indexes. Subsequently, a revised new structural equation model was constituted. Standardized values for the structural equation model are presented in Fig. 2.

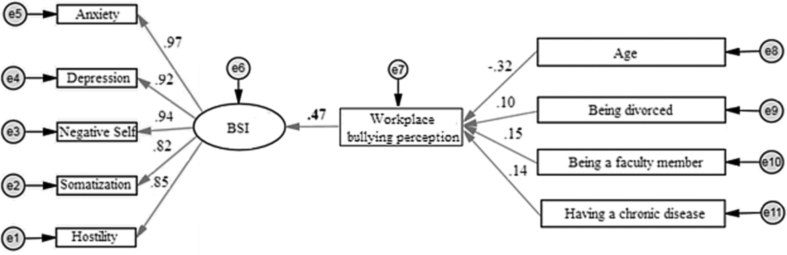

Fig. 2.

The revised structural equation model identifying determinants of the research group's workplace bullying perception. BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory.

One point increase in the workplace bullying perception score was associated with a 0.47 point increase in psychological symptoms evaluated by the BSI (p < 0.001). Standardized path coefficients between BSI latent variable and BSI sub-dimensions were obtained as follows: 0.97 with anxiety, 0.92 with depression, 0.94 with negative self, 0.82 with somatization, and 0.85 with hostility. In the literature, standardized path coefficients that have absolute values less than 0.10 might indicate a small effect, whereas values around 0.30 indicate a medium effect, and values greater than 0.50 indicate a large effect [21]. The goodness-of-fit indexes of the revised structural equation model were within acceptable limits (χ2/df = 3.184, p = 0.000, GFI = 0.942, AGFI = 0.909, NFI = 0.950, CFI = 0.965, RMSEA = 0.079). The revised structural equation model revealed that the variables of age (t = −6.484; p < 0.001), being divorced (t = 2.036; p = 0.042), being a faculty member (t = 3.099; p = 0.002), and having a chronic disease (t = 2.813; p = 0.005) were significantly related to workplace bullying perception scores (Table 4).

The standardized coefficients that were used in comparison of the effects were found to have significant difference between them. In this model, age had the strongest effect on workplace bullying perception scores. According to the results, workplace bullying perception scores decreased with increases in the employees' age (β = −0.314; p < 0.001). Workplace bullying perception scores increased with being divorced (β = 0.100; p = 0.042), being a faculty member (β = 0.152; p = 0.002), and having a chronic disease (β = 0.138; p = 0.005) (Fig. 2).

4. Discussion

In the present study, the mean workplace bullying perception score was 42.24 ± 15.52 (median: 38). The independent variable with the strongest effects on workplace bullying perception was age. The workplace bullying perception score of employees was found to be higher in the 20–29-years-old age group (Table 1). Moreover, the SEM analysis revealed that workplace bullying perception score decreased by 0.32 points for each year of age (Table 4). There are several previous studies reporting higher score of workplace bullying perception in younger age groups [22], [23]. On the other hand, there are several studies reporting no association between the workplace bullying perception and age [6], [11], [24], [25], [26]. We interpret this finding as follows. Young people exhibited higher workplace bullying perception scores than did older people because the young people were newly encountering working life and its associated challenges; thus, they were inexperienced in business life and were less tolerant of negative events.

In the present study, univariate analyses did not reveal significant relationships between workplace bullying perceptions and being divorced (Table 1). However, being divorced was associated with a 0.10 point increase in workplace bullying perception scores compared with the other marital statuses in the SEM analysis (Table 3). Divorced people faced stigmatization and traumatic situations in this community and interpreted these factors as responses within the workplace that were based on their known or detected conditions in the community. Some situations, such as the problems faced by the divorced, exposure to different viewpoints, and evaluations in the workplace, are thought to create factors that increase workplace bullying perception scores; moreover, individuals who have lost their places in their social environments and families have less social support than others. A significant relationship between employees' marital statuses and workplace bullying was not found in the study by Chen and colleagues [7]. However, Şahin et al. [24] reported that single employees are more likely to be exposed to workplace bullying.

The workplace bullying perception scores of those with chronic diseases may have been higher because these individuals are less likely to complete excessive workloads compared with healthy individuals, frequently use sick leave or receive reports, and are difficult to replace when absent. For these and similar reasons, colleagues and management may harbor more negative attitudes against these individuals [27]. In this study, we also found that having a chronic disease was not related to the workplace bullying perception (p > 0.05) among the employees (Table 2). However, the SEM analysis revealed that having a chronic illness increased workplace bullying perception scores by 0.14 points (Table 3). We interpret this finding that people may gain sensitivity due to chronic disease, or they may be more exposed to negative behavior and attitudes because of their illness. However, it was unclear which one of these was effective on high workplace bullying perception of these people.

Research assistants were expected to have more exposure to workplace bullying because of not having a clearly articulated job description, having frequently assigned to the drudgery, feeling stuck between faculty and administrative staff, and having concerns about the unsafe working and future [10]. In the present study, the research assistants exhibited the highest mean workplace bullying perception scores (p < 0.05) among nurse, faculty member, administrative staff, and manager (Table 2). However, the SEM analysis revealed that being a faculty member resulted in a workplace bullying perception score increase of 0.15 points compared with the professional groups (Table 4). Studies have shown that the risk of being exposed to violence among healthcare workers is 16 times higher than that of other service sector employees. The risk of exposure to violence among nurses is three times higher than that of other health care workers [12]. Yavuzer and Civilidağ [25] have reported that nurses and other health workers are more exposed to workplace bullying than physicians. On the other hand, workplace bullying perception of allied health personnel was higher than other employees in the study by Tutar and Akbolat [23]. We interpret this result as follows. This phenomenon may have arisen due to the greater awareness among the faculty members of this issue, and this increased awareness may have arisen from the faculty members' wide range of professional duties and responsibilities; their experiences of pressure, competition and conflict while progressing in academia; their desire to prove that they were exerting more effort than their peers; the uncertainty of the Health Transformation Program; their experiences of the feelings of worthlessness, and the inability to predict the future.

According to our research, one point increase in the workplace bullying perception score was associated with a 0.47 point increase in psychological symptoms evaluated by the BSI (Table 4). It is expected that individuals exposed to workplace bullying experience have more psychiatric (i.e., anxiety, depression, burnout, and post-traumatic stress disorder) [7], [8], [25], psychological (i.e., stress, sleep disorders, aggression, distractibility, reduced self-esteem, and lack of confidence) [9], and psychosomatic (i.e., sleep problems, headaches, stomach disorders, difficulty concentrating, emotional exhaustion, loss of courage, a high level of anger, and memory problems) [6], [11], [26], [28] health complaints. Workplace bullying is also associated with negative emotions level. Victims who have high levels of negative emotions may show aggressive behavior [6], [11] and thoughts of revenge to defend themselves [26] by developing negative attitudes toward other employees. Workplace bullying creates an atmosphere in which communication becomes hostile, immoral, and unethical. Moreover, workplace bullying has been defined as a malicious behavior [9]. Given these findings, hostility scores are likely to be predictors of the ability to contain violent behaviors, such as becoming angered easily and wanting to physically harm others. We found that the workplace bullying perception scores were most strongly affected by the scores of anxiety, negative self, depression, hostility, and somatization (Fig. 2).

Workplace bullying affects individuals mentally and physically and thus can also result in serious psychosocial problems among organizations and communities. The present results revealed that young people, divorced people, faculty members, and people with a chronic disease had the greatest workplace bullying perceptions with our study population. Additionally, the BSI, anxiety, depression, negative self, somatization, and hostility scores of the individuals with high levels of workplace bullying perceptions were also high. We offer the following recommendations for the prevention of the emergence of workplace bullying and perceptions of workplace bullying: (1) units that report such incidents should be created within institutions for employees who believe that they have been exposed to workplace bullying; (2) employees who are being victimized for reasons such as being divorced may have weak social support and thus should be provided with specific social and psychological support; and (3) young workers who have begun working recently should be provided with support to aid their adaptation to their working environment.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO; Geneva (Switzerland): 2002. World report on violence and health: Summary.http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/worldreport/en/summary en.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kırel Ç. vol. 206. Anadolu Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Yayınları; 2008. (Örgütlerde psikolojik taciz (mobbing) ve yönetimi). [Google Scholar]

- 3.International Council of Nurses (ICN), Public Services International (PSI), World Health Organization (WHO), International Labour Organization (ILO) ICN, PSI, WHO, ILO; Geneva (Switzerland): 2005. Framework guidelines for addressing workplace violence in the health sector, the training manual.http://www.ilo.org/safework/info/instr/WCMS_108542/lang–en/index.htm Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Psychiatric Association (APA) American Psychiatric Association; Washington, D. C.: 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Vol. 5th ed. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization (WHO) 1993. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: diagnostic criteria for research. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornero M.A., Martinez B. 2005. Economic and health consequences of initial stage of mobbing: the Spanish case.http://www.webmeets.com/files/papers/SAE/2005/104/CM05_june05.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W.C., Hwu H.G., Kung S.M., Chiu H.J., Wang J.D. Prevalence and determinants of workplace violence of health care workers in a psychiatric hospital in Taiwan. J Occup Health. 2008;50:288–293. doi: 10.1539/joh.l7132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Josipovic-Jelic Z., Stoini E., Celic-BUnikic S. The effect of mobbing on medical staff performance. Acta Clin Croat. 2005;44:347–352. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pranjic N., Males-Bilic L., Beganlic A., Mustajbegovic J. Mobbing, stress, and work ability index among physicians in Bosnia and Herzegovina: survey study. Croat Med J. 2006;47:750–758. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Çivilidağ A., Sargın N. Academics' mobbing and job satisfaction levels. TOJCE. 2013;2:55–66. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mikkelsen E.G., Einarsen S. Relationships between exposure to bullying at work and psychological and psychosomatic health complaints: the role of state negative affectivity and generalized self-efficacy. Scand J Psychol. 2002;43:397–405. doi: 10.1111/1467-9450.00307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kingma M. Workplace violence in the health sector: a problem of epidemic proportion, International Council of Nurses. Int Nurs Rev. 2001;48:129–130. doi: 10.1046/j.1466-7657.2001.00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Einarsen S., Hoel H. Paper presented at the 9th European Congress of Work and Organizational Psychology, Prague, Czech Republic. 2001. The negative acts questionnaire: development, validation and revision of a measure of bullying at work. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Einarsen S., Raknes B.I. Harassment in the workplace and the victimization of men. Violence Vict. 1997;12:247–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aydın O., Öcel H. The negative act questionnaire: a study for validity and reliability (Turkish) Turk Psychol Articles. 2009;12:94–106. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Degoratis L.R. Clinical Psychometric Research; Baltimore, MD: 1992. The brief symptom inventory (BSI). Administration, scoring and procedures manual II. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Şahin N.H., Durak A. Kısa semptom envanteri (brief symptom inventory- BSI): Türk gençleri için uyarlanması. Turk J Psychol. 1994;9:44–56. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Şahin N.H., Durak-Batıgün A., Uğurtaş S. Kısa semptom envanteri (KSE): Ergenler için kullanımının geçerlik, güvenirlik ve faktör yapısı. Turk Psikiyatri Derg. 2002;13:125–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Field A. Vol. 3rd ed. SAGE Publications; 2009. Discovering statistics using SPSS. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hooper D., Couglan J., Mullen M.R. Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. EJBRM. 2008;6:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Şimşek Ö.F. Ekinoks Eğitim ve Danışmanlık Hizmetleri, Siyasal Basın ve Dağıtım; Ankara: 2007. Yapısal eşitlik modellemesine giriş, temel ilkeler ve LİSREL uygulamaları. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Çarıkçı İ.H., Yavuz H. The mobbing (psychological violence) perception among employees: a study on health sector (Turkish) J Süleyman Demirel Univ Inst Social Sci. 2009;10:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tutar H., Akbolat M. Perceptions of mobbing of health employees in terms of genders of managers (Turkish) J Selcuk Univ Inst Social Sci. 2012;28:19–29. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Şahin B., Çetin M., Çimen M., Yıldıran N. Assessment of Turkish junior male physicians' exposure to mobbing behavior. Croat Med J. 2012;53:357–366. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2012.53.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yavuzer Y., Civilidag A. Mediator role of depression on the relationship between mobbing and life satisfaction of health professionals. Dusunen Adam. 2014;27:115–125. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yıldırım A., Yıldırım D. Mobbing in the workplace by peers and managers: mobbing experienced by nurses working in healthcare facilities in Turkey and its effect on nurses. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:1444–1453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01814.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Knoche K., Sochert R., Houston K. NHS Health Scotland; Scotland UK: 2012. Promoting healthy work for workers with chronic illness: a guide to good practice. European Network for Workplace Health Promotion (ENWHP) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karaahmet E. Overview of the psychiatric reflections of mobbing: two case reports. Dusunen Adam. 2013;26:388–391. [Google Scholar]