Abstract

Background

Retrospective studies on cancer patients who have received local anesthesia show a favorable decrease in tumor metastasis and recurrence. However, the mechanisms underlying the benefits of local anesthesia on cancer recurrence are not well understood.

Methods

In this study, we investigated the biological effects of ropivacaine on breast cancer cells and the mechanisms of its action with emphasis on mitochondrial respiration.

Results

Ropivacaine significantly inhibited growth, survival, and anchorage-independent colony formation in two human breast cancer cell lines. It also acted synergistically with a 5-FU in breast cancer cells. Mechanistically, ropivacaine was found to inhibit mitochondrial respiration by suppressing mitochondrial respiratory complex I and II activities, leading to energy depletion, and oxidative stress and damage. The inhibitory effects of ropivacaine in breast cancer cells were abolished in mitochondrial respiration-deficient ρ0 cells, indicating that mitochondrial respiration is essential for the mechanism of action of ropivacaine. Ropivacaine inhibited phosphorylation of Akt, mTOR, rS6, and EBP1 in breast cancer cells, suggesting the association between Akt/mTOR signaling pathway and mitochondrial functions in breast cancer.

Conclusions

Our work clearly demonstrates the inhibitory effects of ropivacaine in breast cancer by disrupting mitochondrial function. Our findings provide a proper understanding of how local anesthetics reduce the risk of tumor recurrence, and thus, support the use of ropivacaine for surgery and to control pain in patients with breast cancer.

Keywords: Breast cancer, ropivacaine, mitochondrial respiration, Akt/mTOR

Introduction

Anesthetics are frequently used for surgical tumor removal and the management of chronic pain in cancer patients (1). In addition to their known effects on preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative pain management, there is emerging evidence that specific anesthetics have an anti-cancer effect (2-4). Several retrospective studies suggest that local anesthesia reduces tumor metastasis and recurrence in patients with breast, prostate, or colon cancer undergoing mastectomy, prostatectomy, or surgery, respectively (5,6). Interestingly, many general anesthetics (e.g., opioids) are immunosuppressive and decrease a patient’s immune defenses against malignant progression (7). In contrast, some local anesthetics have an inhibitory role in tumor growth and invasion (8).

Amide-linked local anesthetics, such as ropivacaine, are commonly used for thoracic paravertebral block in breast cancer surgery (9) and to reduce chronic pain (10). The mechanisms of action of anesthetics are due to their ability to block the voltage-gated sodium channel (10). Notably, accumulating evidence shows that amide-linked local anesthetics directly inhibit growth, migration, and survival of various cancer cell lines (4,11-13). In addition to functioning as a voltage-gated sodium-channel inhibitor, ropivacaine has been shown to inhibit mitochondrial biogenesis, increase reactive oxygen species, activate mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways, and decrease Src activity (8,11). Although the effects of ropivacaine on cancer seem to be specific to tumor cell type, the underlying molecular mechanisms are unknown.

Therefore, in this study, we investigated the effects of ropivacaine on breast cancer using two representative human breast cancer cell lines. We examined the growth, survival, and anchorage-independent colony formation in cells after ropivacaine treatment and analyzed the underlying mechanisms. Our findings show that ropivacaine has direct inhibitory effects by disrupting mitochondrial function and suppressing Akt/mTOR pathway in breast cancer cells. Our findings also demonstrate synergy between ropivacaine and standard chemotherapeutic agents.

Methods

Cell culture and generation of mitochondrial respiration-deficient ρ0 cell line

MDA-MB-468 and SkBr cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection and cultured in Minimal Essential Media supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and 2 mM L-glutamine (Invitrogen, USA). Mitochondria DNA-deficient SkBr ρ0 cell line was established according to the method described by King and Attardi (14). Briefly, cells were cultured as described above and selected with 1 µg/mL ethidium bromide (EtBr; Sigma, USA), supplemented with 200 µM uridine and 1 mM sodium pyruvate (Sigma, MO, USA) for 40 days, and thereafter maintained in the above media without EtBr.

Measurement of proliferation and apoptosis

Cells were treated with ropivacaine (Sigma, USA) and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU, Sigma, USA) alone or in combination for 3 days. Cell proliferation and apoptosis was determined by the CellTiter 96R AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation assay kit (Promega, USA) and flow cytometry with Annexin V/7-AAD (Beckman Coulter, USA), respectively, using the same protocol as reported in our previous study (15).

Soft agar colony formation assay

Soft agar colony formation was carried out using CytoSelect 96-Well Cell Transformation Assay (Cell Biolabs Inc, USA) according the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, a bottom layer of 1.2% agar solution was plated and solidified. A top layer of equal volumes of 1.2% agar solution, culture medium, and cell suspension (1,000 cells/well) was replated. Culture medium (100 µL) was added to the top layer of the soft agar and replaced with fresh medium every 3 days. The cells were incubated for 6–8 days at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Colonies were stained with 0.4% crystal violet (Sigma, USA) and counted under a light microscope.

Measurement of oxygen consumption rate (OCR), mitochondrial membrane potential, and ATP level

Cells were treated with ropivacaine for 24 h prior to measuring OCR, membrane potential, and ATP. Cells were then equilibrated to the un-buffered medium in a CO2-free incubator and transferred to the Seahorse XF24 extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience, USA). Analyses were performed at basal condition. Three mitochondrial inhibitors, oligomycin (1 mM), carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP; 300 mM), and rotenone (1 mM), were sequentially injected for measuring OCR under maximal condition. All injection reagents were adjusted to pH 7.4 on the day of the assay. The Seahorse XF-24 software calculated OCR automatically. Mitochondrial membrane potential was determined by flow cytometry with 5,5',6,6'-tetrachloro-1,1',3,3'-tetraethyl benzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1, Invitrogen) staining according to the manufacturer’s protocol. ATP levels were measured by CellTiter-Glo Luminiescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, WI, USA).

Measurement of oxidative stress and damage

Cells were treated with ropivacaine for 24 h. Mitochondrial superoxide was measured by staining cells with MitoSox Red according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The absorbance at ex/em of 510/580 nm was measured using Spectramax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices). Oxidative DNA damage was determined using the OxiSelect Oxidative DNA Damage ELISA Kit (Cell Biolabs).

Measurement of mitochondrial respiratory complex activity

Cells were treated with ropivacaine for 24 h prior to mitochondrial respiratory complex activity measurement. The activities of mitochondrial respiratory complexes I, II, IV, and V were measured using Mitochondrial Complex I, II, IV, and V Activity Assay Kits (Novagen, USA), respectively, according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Western blot (WB) analyses

Cells were lysed using 4% SDS containing a phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Invitrogen). Total protein concentration was determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific, USA). Equal amounts of total proteins were loaded and resolved using denaturing SDS–PAGE, and analyzed by WB using antibodies against phosphorylated and total Akt, mTOR, 4EBP1 and S6, and β-actin (Cell technology, USA).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired Student’s t-test. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Ropivacaine inhibits breast cancer growth, survival, and colony formation

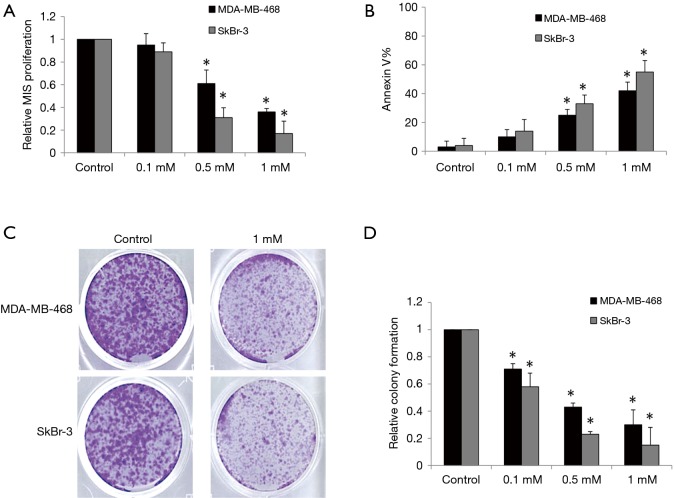

Ropivacaine has been shown to inhibit the growth of various types of cancer cells with an effective dose range of 0.1–10 mM (16,17). We therefore evaluated the effects of ropivacaine at concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, and 1 mM on the growth and survival of MDA-MB-468 and SkBr human breast cancer cells. MDA-MB-468 is a triple-negative breast cancer cell line with genetic amplification of the epithelial growth factor receptor (EFGR), whereas the SkBr-3 cell line overexpresses human epithelial growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) enriched (18). After 72 h of treatment, ropivacaine at concentrations of 0.5 and 1 mM significantly inhibited proliferation and induced apoptosis in a concentration-dependent manner in MDA-MB-468 and SkBr-3 cells (Figure 1A,B). SkBr-3 cells appear to be more sensitive to ropivacaine than MDA-MB-468 cells.

Figure 1.

Ropivacaine targets multiple aspects of breast cancer cells. Ropivacaine at 0.5 and 1 mM significantly decreases proliferation (A) and increases Annexin V (B) of MDA-MB-468 and SkBr cells. Annexin V-positive cells were considered as apoptotic cells. Representative photos taking at 10 days of an anchorage-independent colony-forming assay (C) and quantification of colonies (colonies were stained with 0.4% crystal violet, followed by gentle PBS wash. Magnification was taken at 50×) (D) showing the inhibitory effect of ropivacaine on colony formation of breast cancer cells. The data were derived from three independent experiments and presented as mean ± SEM. *, P<0.05, compared to control.

Anchorage-independent colony formation assay has been demonstrated to specifically assess the propagation and differentiation of subpopulations with “stem cell” properties within a cell line (19). We found that ropivacaine significantly inhibited anchorage-independent colony formation of MDA-MB-468 and SkBr-3 cells (Figure 1C,D). Interestingly, ropivacaine at 0.5 mM significantly inhibits colony formation but does not affect growth and survival, suggesting that the subpopulations of breast cancer cells with “stem cell” properties are more sensitive to ropivacaine than the bulky cell lines.

Ropivacaine disrupts mitochondrial function and induces oxidative stress in breast cancer cells

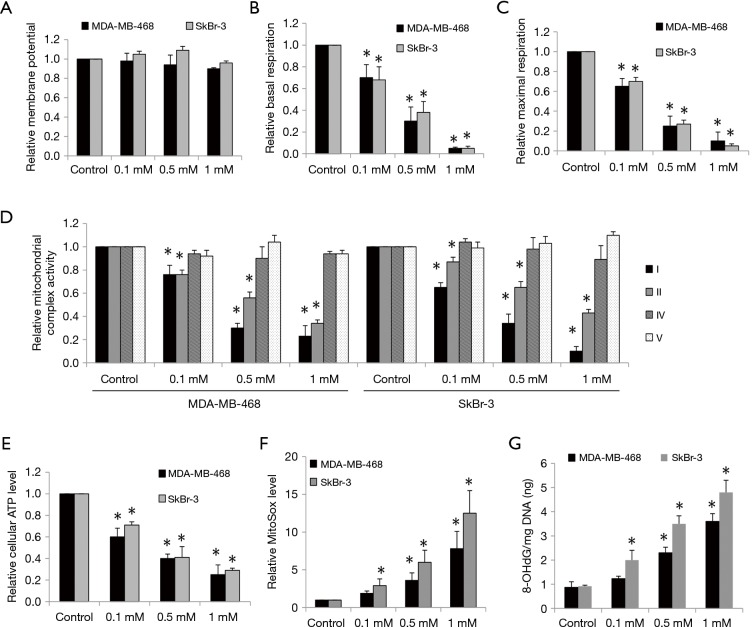

The inhibitory effects of ropivacaine on mitochondrial functions have been observed in various cell types (20,21). To investigate whether the effects of ropivacaine on breast cancer cells are due to mitochondrial dysfunction, we first examined mitochondrial membrane potential and mitochondrial respiration in cells exposed to ropivacaine. Ropivacaine did not affect mitochondrial membrane potential in MDA-MB-468 and SkBr-3 cells (Figure 2A). However, breast cancer cells treated with ropivacaine had reduced baseline and maximal mitochondrial respiration as measured by Seahorse XF24 extracellular flux analyzer (Figure 2B,C), suggesting that ropivacaine inhibits mitochondrial respiration. We further demonstrated that ropivacaine specifically suppressed mitochondrial respiratory complexes I and II, but did not suppress complexes IV and V in breast cancer cells (Figure 2D). This suggests that ropivacaine inhibits mitochondrial respiration by disrupting complex I and II activities. Consistent with the inhibition of mitochondrial respiration, a significant reduction in ATP levels and accumulation of oxidative stress and damage as shown by the increased levels of mitochondrial superoxide and 8-OHdG/mg DNA were observed in ropivacaine-treated breast cancer cells (Figure 2E,F,G). These results demonstrate that ropivacaine disrupts mitochondrial functions, which in turn leads to energy depletion, oxidative stress, and damage in breast cancer.

Figure 2.

Ropivacaine inhibits mitochondrial respiration and induces oxidative stress in breast cancer. (A) Ropivacaine does not affect mitochondrial membrane potential. Ropivacaine dose-dependently suppresses basal (B) and maximal OCR (C). (D) Ropivacaine inhibits activities of mitochondrial complex I and II but not IV and V. Ropivacaine decreases ATP levels (E) and increases mitochondrial superoxide (F) and 8-OHdG/mg DNA levels (G) in breast cancer cells. The data were derived from three independent experiments and presented as mean ± SEM. *, P<0.05, compared to control.

The inhibitory effects of ropivacaine are abolished in mitochondrial respiration-deficient breast cancer ρ0 cells

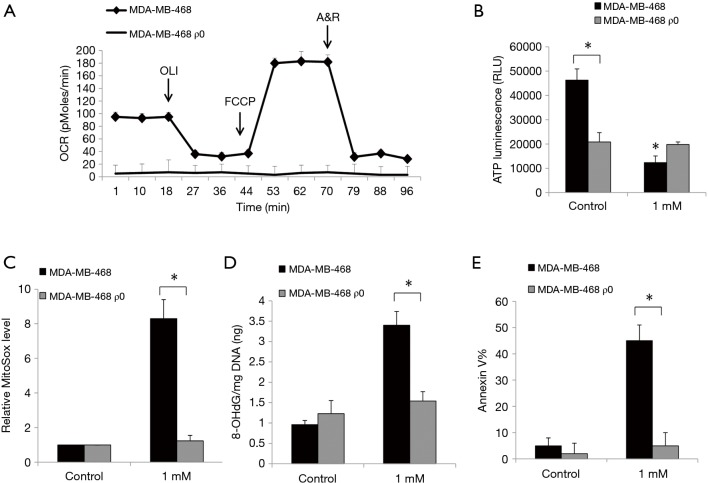

By culturing cells in the presence of ethidium bromide, we established ρ0 cells that lack mitochondrial DNA and thus are incapable of performing mitochondrial respiration (14). Although the generation of ρ0 cells from SkBr-3 cells was unsuccessful, we established ρ0 cells from MDA-MB-468 which have a minimal level of baseline oxygen consumption rate and are non-responsive to uncoupling of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation via FCCP (Figure 3A). We further observed a significantly decreased basal level of ATP in breast cancer ρ0 cells which is likely due to their mitochondrial respiration defects (Figure 3B). Notably, the inhibitory effects of ropivacaine on cellular ATP levels, mitochondrial superoxide, 8-OHdG/mg DNA, and Annexin V were observed in parental MDA-MB-468 but not in MDA-MB-468 ρ0 cells (Figure 3B,C,D,E). Taken together, mitochondrial functions are essential for the inhibitory effects of ropivacaine on breast cancer cells.

Figure 3.

Breast cancer ρ0 cells are resistant to ropivacaine treatment. (A) MDA-MB-468 ρ0 cells have minimal basal level of OCR and are non-responsive to FCCP. (B) ρ0 cells are resistant to ropivacaine-induced depletion of ATP. ATP levels are decreased in ρ0 cells than parental cells. ρ0 cells are resistant to ropivacaine in increasing levels of mitochondrial superoxide (C), 8-OHdG/mg DNA (D) and Annexin V (E). The data were derived from three independent experiments and presented as mean ± SEM. *, P<0.05, compared to MDA-MB-468.

Ropivacaine significantly enhances 5-FU’s effects in breast cancer cells by suppressing Akt/mTOR signaling pathway

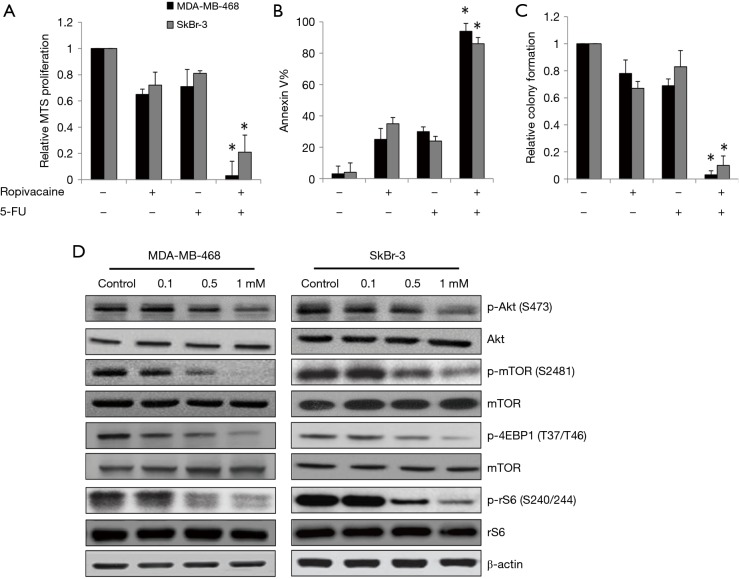

To investigate whether ropivacaine acts synergistically with a standard chemotherapeutic agent in breast cancer cells, we compared the effects of the combination of ropivacaine and 5-FU with those of each drug alone. We designed and performed combination studies using the concentration of ropivacaine or 5-FU that slightly or moderately affects breast cancer cells. Our results showed that combination of ropivacaine and 5-FU was significantly more effective than ropivacaine or 5-FU alone at inhibiting growth, survival, and colony formation (Figure 4A,B,C). Of note, nearly complete inhibition of the multiple biological activities of breast cancer was observed with the drug combination.

Figure 4.

Ropivacaine augments 5-FU’s inhibitory effects through suppresses mTOR signaling pathway in breast cancer cells. Ropivacaine significantly augments the effects of 5-FU in decreasing proliferation (A), inducing apoptosis (B) and inhibiting colony formation (C) in MDA-MB-468 and SkBr cells. 0.5 mM of ropivacaine and 1 µM of 5-FU were used for the combination study. *, P<0.05, compared to ropivacaine or 5-FU alone. (D) The phosphorylation of Akt, mTOR, rS6 and 4EBP1 are decreased by ropivacaine in breast cancer cells.

Because the Akt/mTOR pathway has been shown to control mitochondrial activity and biogenesis (22,23), we assessed the effects of ropivacaine on the essential molecules involved in the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. We observed decreased phosphorylation of Akt (S473) and mTOR (S2481) in MDA-MB-468 and SkBr cells exposed to ropivacaine (Figure 4D). Phosphorylation of mTOR signaling downstream effectors, such as the ribosomal S6 protein (rS6) and 4EBP1, was also decreased by ropivacaine (Figure 4D). These results suggest that ropivacaine augments the effects of chemotherapeutic agents in breast cancer cells, likely by suppressing the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway.

Discussion

Substantial evidence has shown that anesthetic management of a cancer patient could potentially influence long-term outcome. Although general anesthetics (e.g., opioids and volatile agents) have been speculated to promote tumor metastasis due to their immunosuppressive and pro-angiogenic effects, retrospective clinical trials on cancer patients suggest that regional and local anesthesia are independent beneficial factors for tumor recurrence after cancer surgery (4,24). Preclinical data also suggest that many local anesthetics have anti-proliferation and pro-apoptotic activities on cancer cell cultures and xenograft mouse model (12,17,25). Better understanding of the potential role of anesthetics in cancer will be helpful to select the optimal anesthetic regimens for better treatment outcomes in cancer patients. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of clinically used local anesthetics on breast cancer cell proliferation, colony formation, and survival.

The human breast cancer cell lines we selected to demonstrate the potential effects of ropivacaine were MDA-MB-468 and SkBr-3 cells. These two cell lines represent different cellular origin and display genetic heterogeneity with HER2 or EFGR overexpression which are highly resistant to standard chemotherapy (18). We show that ropivacaine inhibits proliferation, colony formation, and survival of MDA-MB-468 and SkBr-3 cells (Figure 1). Of note, ropivacaine seems to preferentially target breast cancer subpopulations with stem cell properties rather than bulky cells. The inhibitory effects of ropivacaine on proliferation, survival, and invasion have been demonstrated in hepatocellular carcinoma and lung and colon cancer (11,16,26). In line with these studies, our findings add breast cancer to the growing list of cancers inhibited by ropivacaine. We further show that the combination of ropivacaine and 5-FU (a standard chemotherapeutic agent for breast cancer treatment) achieves almost complete inhibition of all aspects of breast cancer activities when using a concentration of 5-FU that marginally inhibits breast cancer cells as single drug alone (Figure 4A,B,C). This suggests that ropivacaine is a useful addition to the treatment armamentarium for breast cancer. We and others have consistently demonstrated the direct anti-cancer effect of ropivacaine in cell-based cancer models. Other amide-linked local anesthetics, such as lidocaine and bupivacaine, have similar effects on cancer (27,28). Because all of the current studies are cell culture system-based, further investigations are warranted to evaluate the efficacy of amide-linked local anesthetics in patient-derived xenograft mouse models predictive of clinical outcomes, and ultimately clinical trials.

Although the inhibitory effects of ropivacaine have been reported in various cancers, the underlying mechanisms are not well understood. We demonstrated that mitochondrial dysfunction is the mechanism of action of ropivacaine in breast cancer. Ropivacaine significantly decreases mitochondrial respiration without affecting membrane potential by targeting mitochondrial respiratory complexes I and II but not IV or V (Figure 2A,B,C,D). The loss of activities in mitochondrial respiration-deficient cells confirms mitochondrial respiration as the essential target of ropivacaine in breast cancer (Figure 3). This is consistent with previous studies on the effects of ropivacaine on mitochondrial oxidation and bioenergetics in normal myocardial cells (20,29). Our findings extend the findings of previous work by demonstrating the inhibitory effects of ropivacaine on tumor cells. mTOR directly controls mitochondrial functions and inhibition of mTOR suppresses mitochondrial respiration in cancer cells (23). In agreement with this, we observed the decreased phosphorylation levels of essential molecules involved in Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in breast cancer cells exposed to ropivacaine (Figure 4D). Our work and that of others suggest that inhibition of Akt/mTOR negatively affects mitochondrial function and subsequently induces oxidative stress in breast cancer cells.

In summary, we are the first to systematically demonstrate the inhibitory effects of ropivacaine on breast cancer cells and to show mitochondrial dysfunction as its underlying mechanism. The synergism between ropivacaine and 5’-FU suggests that ropivacaine could be a useful addition to breast cancer treatment. Our study provides the fundamental evidence for clinical observations on the beneficial role of local anesthesia in reducing breast cancer recurrence. Since local anesthetics, which are usually given using an indwelling catheter, are also used for postoperative pain control, it is worthy of investigating whether continuous administration of local anesthetics by indwelling catheter has better efficacy than single administration during surgery. It is also noteworthy to investigate the various indwelling catheter locations, such as the surgical wound, intra-articular, or intrapleural area, to obtain the maximum benefit with minimal side effects using low drug concentrations.

Acknowledgements

Funding: This work was supported by a research grant provided by Jingzhou Central Hospital (201406016).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Gudaityte J, Dvylys D, Simeliunaite I. Anaesthetic challenges in cancer patients: current therapies and pain management. Acta Med Litu 2017;24:121-7. 10.6001/actamedica.v24i2.3493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Snyder GL, Greenberg S. Effect of anaesthetic technique and other perioperative factors on cancer recurrence. Br J Anaesth 2010;105:106-15. 10.1093/bja/aeq164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tavare AN, Perry NJ, Benzonana LL, et al. Cancer recurrence after surgery: direct and indirect effects of anesthetic agents. Int J Cancer 2012;130:1237-50. 10.1002/ijc.26448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mao L, Lin S, Lin J. The effects of anesthetics on tumor progression. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol 2013;5:1-10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Exadaktylos AK, Buggy DJ, Moriarty DC, et al. Can anesthetic technique for primary breast cancer surgery affect recurrence or metastasis? Anesthesiology 2006;105:660-4. 10.1097/00000542-200610000-00008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biki B, Mascha E, Moriarty DC, et al. Anesthetic technique for radical prostatectomy surgery affects cancer recurrence: a retrospective analysis. Anesthesiology 2008;109:180-7. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31817f5b73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Plein LM, Rittner HL. Opioids and the immune system - friend or foe. Br J Pharmacol 2017. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1111/bph.13750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piegeler T, Votta-Velis EG, Liu G, et al. Antimetastatic potential of amide-linked local anesthetics: inhibition of lung adenocarcinoma cell migration and inflammatory Src signaling independent of sodium channel blockade. Anesthesiology 2012;117:548-59. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182661977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sahu A, Kumar R, Hussain M, et al. Comparisons of single-injection thoracic paravertebral block with ropivacaine and bupivacaine in breast cancer surgery: A prospective, randomized, double-blinded study. Anesth Essays Res 2016;10:655-60. 10.4103/0259-1162.191109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heavner JE. Local anesthetics. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2007;20:336-42. 10.1097/ACO.0b013e3281c10a08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang HW, Wang LY, Jiang L, et al. Amide-linked local anesthetics induce apoptosis in human non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2016;8:2748-57. 10.21037/jtd.2016.09.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang YC, Hsu YC, Liu CL, et al. Local anesthetics induce apoptosis in human thyroid cancer cells through the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. PLoS One 2014;9:e89563. 10.1371/journal.pone.0089563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi K, Ohno S, Uchida S, et al. Cytotoxicity and type of cell death induced by local anesthetics in human oral normal and tumor cells. Anticancer Res 2012;32:2925-33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashiguchi K, Zhang-Akiyama QM. Establishment of human cell lines lacking mitochondrial DNA. Methods Mol Biol 2009;554:383-91. 10.1007/978-1-59745-521-3_23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu M, Li R, Zhang J. Repositioning of antibiotic levofloxacin as a mitochondrial biogenesis inhibitor to target breast cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016;471:639-45. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.02.072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Gac G, Angenard G, Clement B, et al. Local Anesthetics Inhibit the Growth of Human Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cells. Anesth Analg 2017;125:1600-9. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lucchinetti E, Awad AE, Rahman M, et al. Antiproliferative effects of local anesthetics on mesenchymal stem cells: potential implications for tumor spreading and wound healing. Anesthesiology 2012;116:841-56. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31824babfe [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sorlie T, Perou CM, Tibshirani R, et al. Gene expression patterns of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001;98:10869-74. 10.1073/pnas.191367098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao CF, Xie Q, Su YL, et al. Proliferation and invasion: plasticity in tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005;102:10528-33. 10.1073/pnas.0504367102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang S, Yao S, Li Q. Effects of ropivacaine and bupivacaine on rabbit myocardial energetic metabolism and mitochondria oxidation. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technolog Med Sci 2003;23:178-9, 183. 10.1007/BF02859950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grishko V, Xu M, Wilson G, et al. Apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction in human chondrocytes following exposure to lidocaine, bupivacaine, and ropivacaine. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92:609-18. 10.2106/JBJS.H.01847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morita M, Gravel SP, Chenard V, et al. mTORC1 controls mitochondrial activity and biogenesis through 4E-BP-dependent translational regulation. Cell Metab 2013;18:698-711. 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramanathan A, Schreiber SL. Direct control of mitochondrial function by mTOR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009;106:22229-32. 10.1073/pnas.0912074106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gottschalk A, Sharma S, Ford J, et al. Review article: the role of the perioperative period in recurrence after cancer surgery. Anesth Analg 2010;110:1636-43. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181de0ab6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoon JR, Whipple RA, Balzer EM, et al. Local anesthetics inhibit kinesin motility and microtentacle protrusions in human epithelial and breast tumor cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2011;129:691-701. 10.1007/s10549-010-1239-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baptista-Hon DT, Robertson FM, Robertson GB, et al. Potent inhibition by ropivacaine of metastatic colon cancer SW620 cell invasion and NaV1.5 channel function. Br J Anaesth 2014;113 Suppl 1:i39-i48. 10.1093/bja/aeu104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang L, Hu R, Cheng Y, et al. Lidocaine inhibits the proliferation of lung cancer by regulating the expression of GOLT1A. Cell Prolif 2017;50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xuan W, Zhao H, Hankin J, et al. Local anesthetic bupivacaine induced ovarian and prostate cancer apoptotic cell death and underlying mechanisms in vitro. Sci Rep 2016;6:26277. 10.1038/srep26277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sztark F, Malgat M, Dabadie P, et al. Comparison of the effects of bupivacaine and ropivacaine on heart cell mitochondrial bioenergetics. Anesthesiology 1998;88:1340-9. 10.1097/00000542-199805000-00026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]