Abstract

Pathogen source attribution studies are a useful tool for identifying reservoirs of human infection. Based on Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) data, such studies have identified chicken as a major source of C. jejuni human infection. The use of whole genome sequence-based typing methods offers potential to improve the precision of attribution beyond that which is possible from 7 MLST loci. Using published data and 156 novel C. jejuni genomes sequenced in this study, we performed probabilistic host source attribution of clinical C. jejuni isolates from France using three types of genotype data: comparative genomic fingerprints; MLST genes; 15 host segregating genes previously identified by whole genome sequencing. Consistent with previous studies, chicken was an important source of campylobacteriosis in France (31–63% of clinical isolates assigned). There was also evidence that ruminants are a source (22–55% of clinical isolates assigned), suggesting that further investigation of potential transmission routes from ruminants to human would be useful. Additionally, we found evidence of environmental and pet sources. However, the relative importance as sources varied according to the year of isolation and the genotyping technique used. Annual variations in attribution emphasize the dynamic nature of zoonotic transmission and the need to perform source attribution regularly.

Introduction

Campylobacter spp. are regarded as the most common foodborne bacterial zoonosis in Europe1, despite potential underestimation due to underreporting of cases2. In France, C. jejuni is responsible for nearly 80% of human infections while C. coli accounts for around 15%3. The economic burden of campylobacteriosis has been estimated to 2.4 billion euros annually in Europe4, with estimates of £50 million in 2008–2009 in the United Kingdom5 and 82 million euros in the Netherlands in 20116.

Campylobacter spp. are frequent colonizers of the digestive tract of domesticated animals such as livestock7–10 and pets11,12, as well as wild birds13–15, and have been isolated from environmental waters sources16,17. Accurately quantifying the relative importance of each Campylobacter reservoir in human infections constitutes an important aim in public health to develop control strategies to decrease the human and economic burden of campylobacteriosis. Previous source attribution studies, principally based upon Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) data18 which consists in the sequencing and the allele designation of 7 housekeeping genes of C. jejuni, have identified chicken as a major source of human infection worldwide, while ruminants, pets and environmental sources are also implicated19–22. However, MLST-based attribution has limited efficacy for source attribution of clinical cases from clonal complexes and sequence type that are isolated from multiple hosts, since they show identical allelic variations in the 7 studied genes23. Recently, a pan genome approach was used to investigate host signal within 411 C. jejuni genomes, and 15 markers were identified as promising candidates for source attribution as they allowed the segregation of C. jejuni isolates according to their host24. In addition, comparative genomic fingerprinting approach (CGF) has also been developed to genotype C. jejuni isolates with a high resolution25 and has been extensively used in Canada for routine surveillance of campylobacteriosis25–27. The CGF40 approach, which consists in the assessment of the presence/absence of 40 genes belonging to the accessory genome of C. jejuni through gene amplification, showed concordant results with MLST with a higher discriminatory power28, and could be an interesting alternative to MLST by potentially improving the accuracy of source attribution studies.

Here, we assessed the accuracy of attributions of C. jejuni isolates to their source based on MLST, CGF40 profiles and the 15 host segregating markers, and used the most accurate methods to identify the most likely origin of French campylobacteriosis from 2009 and 2015. Isolates originating from chicken, ruminant, pets, environmental waters and wild birds were considered as potential sources of human infection in the analysis.

Results

Clinical, animal, and environmental isolates genotyping using CGF40, MLST and whole genome sequencing (WGS)

C. jejuni clinical isolates from 2009 appeared to be highly diverse with 85 CGF40 clusters based on 100% of similarity between isolates, and 62 STs29. Clinical isolates from 2015 were also highly diverse with 229 CGF40 genotypes found. In addition, MLST performed on a subset of these clinical isolates (n = 79) using WGS, revealed 54 different STs, and 79% of the clinical isolates belonged to the 12 most common clonal complexes found (ST-21, ST-206, ST-257, ST-353, ST-48, ST-464, ST-22, ST-283, ST-42, ST-45, ST-52 and ST-658 complexes).

A total of 1,618 animal and environmental C. jejuni isolates from putative sources of human infection (i.e. chicken, ruminant, environment, and pets) constituted the comparison data set of CGF40 genotypes, while the comparison data sets of MLST and host-segregating markers profiles comprised respectively 857 and 740 isolates characterized in previous studies (Supplementary Table S1).

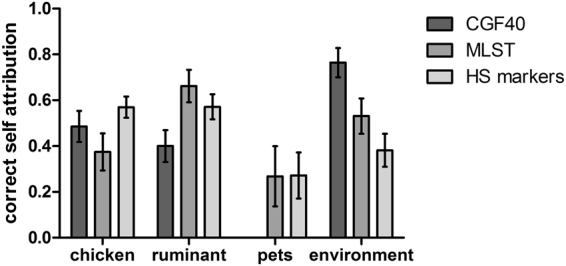

Accuracy of the several genotypes data in source attribution through self-attribution tests

The accuracy of the different genotyping methods in source attribution was assessed with isolates of a known origin. Self-attributions were performed on randomly selected subsets of isolates from each of the 4 putative contamination sources and the rates of correct self-attributions are shown in the Fig. 1. The probabilities of assignment of these isolates to the others sources are presented in the Table 1, as well as their confidence interval at 95%. The probabilities of correct self-attribution using CGF40 markers for source attribution were estimated to 49% in chicken (CI95% = 0.418, 0.553), 40% in ruminant (CI95% = 0.330, 0.469), 76% in environment (CI95% = 0.701, 0.828), and 0% (CI95% = 0.00, 0.00) in pets isolates. However, MLST allowed significantly higher correct self-attribution rates than CGF40 within ruminant (66%; CI95% = 0.591, 0.733) and pets isolates (27%; CI95% = 0.137, 0.399). Nevertheless, MLST showed a significantly lower rate within environmental isolates (53%; CI95% = 0.454, 0.608) than CGF40 since there was no overlap between their confidence interval at 95%, while a similar rate was observed within chicken isolates with 37% (CI95% = 0.294, 0.455) of correct self-attribution. Finally, the use of the 15 host-segregating markers in source attribution gave a correct self-attribution of 57% (CI95% = 0.524, 0.616) in chicken, which is significantly higher than using MSLT, while correct self-attribution rates, similar to MLST, were observed in ruminant (57%; CI95% = 0.517, 0.626), environmental (38%; CI95% = 0.309, 0.453) and pets isolates (27%; CI95% = 0.172, 0.372).

Figure 1.

Correct self-attribution rates of C. jejuni isolates from 4 putative contamination sources based on genomic data obtained with CGF40, MLST or WGS (15 host segregating markers).

Table 1.

Self-attribution of C. jejuni isolates from 4 putative sources of human infections using molecular data from CGF40, MLST or WGS using 15 host-segregating markers (HS markers).

| CGF40 | MLST | WGS (15 HS markers) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chicken | Ruminant | Environment | Pets | Chicken | Ruminant | Environment | Pets | Chicken | Ruminant | Environment | Pets | |

| Chicken | 0.49 (0.42–0.55) | 0.23 (0.17–0.29) | 0.27 (0.21–0.34) | 0.01 (−0.01–0.03) | 0.37 (0.29–0.46) | 0.27 (0.19–0.34) | 0.18 (0.10–0.26) | 0.18 (0.12–0.24) | 0.57 (0.52–0.62) | 0.11 (0.06–0.16) | 0.12 (0.03–0.21) | 0.20 (0.11–0.30) |

| Ruminant | 0.19 (0.10–0.28) | 0.40 (0.33–0.47) | 0.14 (0.06–0.23) | 0.26 (0.19–0.34) | 0.11 (0.05–0.17) | 0.66 (0.59–0.73) | 0.08 (0.03–0.13) | 0.15 (0.06–0.23) | 0.28 (0.21–0.34) | 0.57 (0.52–0.63) | 0.06 (0.02–0.11) | 0.09 (0.04–0.14) |

| Environment | 0.24 (0.17–0.30) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.76 (0.70–0.83) | 0.00 (0.00–0.00) | 0.08 (0.04–0.13) | 0.01 (0.00–0.01) | 0.53 (0.45–0.61) | 0.38 (0.30–0.45) | 0.20 (0.07–0.33) | 0.05 (0.02–0.07) | 0.38 (0.31–0.45) | 0.37 (0.28–0.47) |

| Pets | 0.38 (0.32–0.45) | 0.05 (0.03–0.08) | 0.56 (0.49–0.63) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | 0.33 (0.28–0.37) | 0.25 (0.22–0.27) | 0.16 (0.05–0.27) | 0.27 (0.14–0.40) | 0.32 (0.22–0.41) | 0.11 (0.07–0.17) | 0.30 (0.22–0.38) | 0.27 (0.17–0.37) |

Host populations in bold letters are populations for which isoaltes were tested in self-attribution tests. Self-attribution probabilities for a same host population are presented in line.

Source attribution of C. jejuni clinical isolates from 2009 and 2015

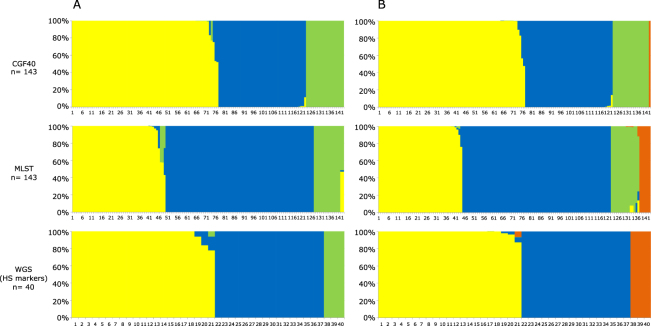

The probabilistic assignments of each clinical case from 2009 and 2015 to the different putative contamination sources were calculated using STRUCTURE software and are shown in Figs 2 and 3. Regarding clinical isolates from 2009 (Fig. 2A), MLST attributed 55% (CI95% = 0.468, 0.632) of isolates to ruminant, 34% (CI95% = 0.260, 0.413) to chicken and 11% (CI95% = 0.062, 0.163) to the environment. Based on the 15 host-segregating markers, we observed an equivalent attribution of clinical isolates in 2009 to chicken and ruminant with respectively 51% (CI95% = 0.355, 0.673) and 41% (CI95% = 0.253, 0.566), while the implication of the environment was estimated to 8% (CI95% = 0.0, 0.162). Finally, using the CGF40 data to perform source attribution, a higher implication of the chicken reservoir was observed (53%; CI95% = 0.447, 0.609) in clinical cases from 2009, while ruminant and the environment showed respectively 33% (CI95% = 0.253, 0.407) and 14% (CI95% = 0.084, 0.199) of attribution.

Figure 2.

Estimated source probabilities of French clinical isolates from 2009 using three genotyping methods for source attribution. (A) Probabilities of clinical isolates to originate from 3 putative sources (yellow: chicken; blue: ruminant, and green: environment), (B) Probabilities of clinical isolates to originate from 4 putative sources (yellow: chicken; blue: ruminant, green: environment, orange: pets). Each vertical bar represents one isolate, and the color of the bar shows the estimated probability that this isolate originates from each of the potential sources.

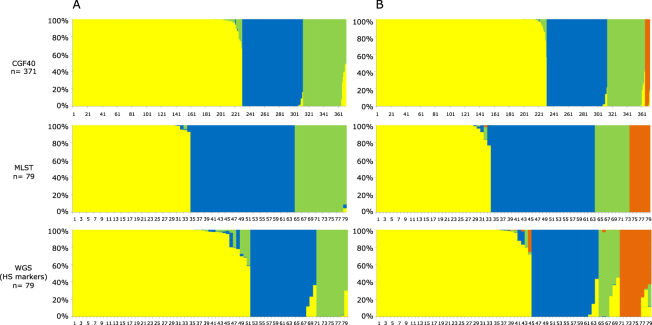

Figure 3.

Estimated source probabilities of French clinical isolates from 2015 using three genotyping methods for source attribution. (A) Probabilities of clinical isolates to originate from 3 putative sources (yellow: chicken; blue: ruminant, and green: environment), (B) Probabilities of clinical isolates to originate from 4 putative sources (yellow: chicken; blue: ruminant, green: environment, orange: pets). Each vertical bar represents one isolate, and the color of the bar shows the estimated probability that this isolate originates from each of the potential sources.

When pets were added as a putative source of human contamination in 2009 (Fig. 2B), some clinical isolates were attributed to this source but the global trends remained similar using CGF40 (Chicken: 53% [CI95% = 0.449, 0.613]; Ruminant: 33% [CI95% = 0.252, 0.406]; Environment: 13% [CI95% = 0.077, 0.189]; Pets: 1% [CI95% = 0.0, 0.021]) and MLST (Chicken: 31% [CI95% = 0.231, 0.383]; Ruminant: 55% [CI95% = 0.467, 0.631]; Environment: 10% [CI95% = 0.052, 0.149]; Pets: 4% [CI95% = 0.010, 0.076]). However, when the host segregating markers were used, all previously environment-assigned clinical isolates were attributed to pets while the attributions to chicken and ruminant were equivalent than previously (Chicken: 52% [CI95% = 0.360, 0.681]; Ruminant: 40% [0.245, 0.561]; Environment: 0% [CI95% = 0.00, 0.00]; Pets: 8% [CI95% = 0.00, 0.162]).

Clinical cases from 2015 were then probabilistically assigned to sources (Fig. 3). In MLST-based assignments, 43% (CI95% = 0.318, 0.539) of isolates were attributed to chicken, 38% (CI95% = 0.273, 0.491) to ruminants and 19% (CI95% = 0.101, 0.277) to the environment (Fig. 3A). The 15 host segregating markers allowed the assignment of 63% (CI95% = 0.532, 0.737), 24% (CI95% = 0.146, 0.331) and 13% (CI95% = 0.057, 0.197) of clinical isolates to the chicken, ruminant and environmental reservoirs respectively. These attributions were consistent with the proportions of clinical cases attributed to the chickens (62%; CI95% = 0.573, 0.670), ruminants (22%, CI95% = 0.178, 0.262) and environmental samples (16%, CI95% = 0.122, 0.194) using CGF40 data for source attribution.

When pets were included in the source attribution study as a potential source of human contamination in 2015 (Fig. 3B), global trends were unchanged except for the assignment based on host segregating markers, where 12% (CI95% = 0.050, 0.188) of clinical cases were assigned to pets, while assignment to the environment decreased to 7% (CI95% = 0.018, 0.119). Using CGF40 data or MLST in the STRUCTURE model, 2% (CI95% = 0.005, 0.032) and 8% (CI95% = 0.017, 0.136) of human isolates were respectively assigned to the pets reservoir.

Discussion

In this study, we attribute the source of clinical C. jejuni isolates using MLST, CGF40 genotypes and allelic variation within 15 host-segregating markers derived from WGS. While MLST has previously been widely used to assign a source to clinical isolates of Campylobacter spp.19,20,22,30–34, the use of CGF40 and WGS host-segregating markers are relatively recent24,35. The accuracy of each genotyping method was assessed by performing self-attribution tests. In these tests, host-segregating markers allowed the greatest rate of correct assignment of isolates from all hosts to their origin apart from environment isolates for which CGF40 gave a higher probability. These results are not surprising since host-segregating markers were picked for their potential to improve source attribution as they showed the highest rates of correct self-attribution in chicken and ruminant24. MLST gave equivalent probabilities of correct-assignment to host-segregating marker analysis in all hosts except for chicken isolates where attribution was lower than the host-segregating markers. Using CGF40, the probability of correct-assignment in chicken isolates was equivalent to the probability using the host segregating markers, but lower probabilities were observed in ruminant and pets isolates.

The difference of accuracy in self-attribution tests according to the genotyping method used, which may trigger differences in source attribution of clinical cases, could be explained by the resolution of data provided by each genotyping method. MLST and host segregating markers provide highly discriminatory data since they assess the allelic variation within each tested gene. For example, there were 35 to 59 different alleles among each MLST genes and from 27 to 169 different alleles in each host-segregating markers within the isolates from this study, while CGF40 produces only binary data (0 or 1) informing on presence or absence of 40 assay genes. Furthermore, data resolution is important especially in a probabilistic model like STRUCTURE which assumes that each host population is characterized by its own set of allelic frequencies, and in which low numbers of markers showing high levels of allelic diversity are more informative than randomly selected markers36. Indeed, if the genetic information provided by the genotyping method used to characterize isolates is not sufficient to discriminate isolates from several sources, misattributions of clinical cases to their source can occur using STRUCTURE33. This is consistent with conclusions of a recent study describing CGF40 as an alternative technique for source attribution in combination with comparative exposure assessment but not suitable using a source attribution model like the Asymmetric Island model20 since CGF40 do not provide enough details on genotypes compared with MLST35.

Based on large datasets of C. jejuni isolates from several putative sources of human contamination, the most likely origins of French campylobacteriosis from 2009 and 2015 were determined. In contrast to the majority of source attribution studies performed on MLST genes and using STRUCTURE software20,22,37, ruminants were the most common putative source of campylobacteriosis from 2009 in France (55%), and were equal to chicken in clinical cases from 2015 (38% for ruminant, 41–43% for chicken) based on MLST assignments. Nevertheless, this result is consistent with other source attribution studies33,38, and may support a greater role for the ruminant reservoir in campylobacteriosis39.

However, when host-segregating-based assignments were considered, as they showed a better accuracy in self-attribution than MLST, ruminant and chicken were equally important in France in 2009, but there were more attributions to chicken in 2015, comparable to other studies19–21,31,34,40. Despite a variation in the source attribution of clinical isolates from 2009 and 2015, both populations were mainly contaminated with agricultural C. jejuni which include isolates from chicken and ruminants. Contamination with chicken was especially associated with the consumption of broiler meat (undercooked)1,19,34,41–44. This is consistent with the high prevalence of Campylobacter spp. on carcasses and retail broiler meat in France estimated to 88% and 76% respectively45,46, and the important overlap between C. jejuni genotypes circulating in chicken and isolated in humans in France29.

Different risk factors were identified for human contamination by ruminants-associated Campylobacter spp. such as consumption of tripe or raw milk, barbecuing in non-urban areas, contact with garden soil or having a local and a regional tap water provider at home19,34,37,43,44. In addition to these, consumption of undercooked beef meat was identified as a risk factor for C. jejuni infections in France as well as in the Netherlands to a lesser extent42,47. However, despite a high prevalence of Campylobacter ssp. in French cattle10, the food-borne transmission of Campylobacter spp. is not clear, especially since no Campylobacter were detected in bovine meat in France48 in accordance with studies reporting rare beef or veal contamination49–51. On the other hand, cattle livers could be a non-negligible source of contamination in France since they constitute a popular dish in French cuisine and were shown to be highly contaminated by Campylobacter spp.51,52. As previously suggested19,33,35, contact with animals and the environmental contamination by ruminants, including water contamination, need also to be considered since Campylobacter spp. were shown to survive in bovine manure53 or during anaerobic digestion of livestock effluents in biogas plant54,55. Waterborne transmission of Campylobacter from ruminant to human has been previously reported56 and a recent 2-year study highlighted a high prevalence (80.7%) of Campylobacter spp. in environmental waters from intensive livestock farming areas in France57.

Implication of the environmental reservoir in our study, including environmental waters and wild birds, was low in 2009 (0–11% using MLST or the host-segregating markers) but slightly increased in 2015 (7–19% using MLST or the host-segregating markers). Our environmental-related estimates were in accordance with previous works19,33,34,37,58, which mainly associated these cases to consumption of untreated or private well water, practice of recreational activities related to water59–61, game consumption34, or contact with garden soil19, while consumption of drinking water in bottles were protective60. Consistent with this, contamination through the consumption of treated drinking water is unlikely in France as no Campylobacter were isolated from drinking water16, and from groundwater despite the detection in this case of C. jejuni and C. coli genomes in the samples62. However, it was reported that 50% of surface water upstream treatment plants were contaminated by Campylobacter spp. in Brittany, France16, suggesting that any failure in treatment (e.g. chlorination) could trigger to human contamination. This has been previously described worldwide43,63, as well as in France, where an agricultural contamination of groundwater was hypothesized64.

The role of wild birds in human contamination has been poorly investigated in France. As reported by Cody et al.58, several studies highlighted the contamination of equipment and surfaces in children playgrounds associated with a frequent hand-to-mouth behaviour in children65, and consumption of milk from bottle where the top had been pecked by birds66, as potential Campylobacter transmission routes from wild birds to human. In addition, isolation of C. jejuni belonging to wild bird-associated clonal complex (CC-177) in freshwater in France67 supports the previously described potential waterborne transmission of Campylobacter from wild birds to human68.

Companion animals including cat and dog were not highly involved in clinical cases in France (4% to 12% using MLST or the host-segregating markers), consistent with previous attributions22,31 and contrasting with the 25% of clinical cases attributed to pets in the Netherlands32. With regard to self-attribution tests, probabilities of correct assignment were generally low in pets regardless of the genotyping method used (MLST: 0.268 WGS: 0.272 CGF40: 0.0), suggesting an overlap of pets genotypes with those from the 3 others reservoirs. It is highlighted by the predominance of ST-45 in pets32,69, and its isolation in chicken29,68,70, environmental waters, wild birds58,65,71, and cattle24,72, indicating that chicken, ruminants or environment are likely to be significant sources of Campylobacter for pets through several transmission routes (e.g. food such as raw meat or offal). However, when pets are contaminated they may constitute a transmission route for chicken, ruminant or environmental-related Campylobacter to humans, suggesting that owning a companion animal increased human exposure to Campylobacter spp., emphasizing its role as risk factor32,41,59. Another potential scenario is the role of human in pets contamination, since these animals are likely to be fed with the same foods than their owner and especially with their food leftovers32.

Finally, our source attribution is not without limitations. While chicken and cattle C. jejuni collections show a national coverage10,45,46, pets and environmental populations may not be representative of C. jejuni from these reservoirs in France, as sampling surveys were locally conducted57,67,73. However, samplings were done on large period of time (6-month or 2-year period) to isolate a high number of strains in order to minimize this bias. In addition, the time span of strains isolation is important to consider, especially in a highly recombinant microorganism like Campylobacter, in which MLST genotypes were shown to be increasingly different over time74. However this bias can be nuanced as several studies identified a temporal stability in the population structure of isolates from chicken, wild birds and clinical cases75–77. Moreover, clinical cases studied here may not be representative of all notified French campylobacteriosis C. jejuni cases, since surveillance of campylobacteriosis in France is not mandatory leading to underestimate its incidence78. Therefore, it was not possible to get a representative collection of all cases occurring in France. However, in our study, we selected C. jejuni campylobacteriosis cases from the 10 most populated departments which represent 26% of the French population with 17,585,983 inhabitants (official statistics in 2014 from the National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies). Lastly, the comparison of our results with studies using different source attribution models could be discussed, nevertheless, for the two main models used for source attribution (STRUCTURE and Asymetric island model), Sheppard et al.20 showed that they produced consistent results.

In conclusion, a variation was observed in assignments of French clinical cases between 2009 and 2015 and according to the genotyping method used. The host segregating markers were the most accurate in self-attribution especially for chicken isolates and apart from environmental isolates. A predominant role of agricultural reservoirs (chicken and ruminant) was observed in campylobacteriosis from 2009 and 2015 in France, emphasizing the importance of intervention strategies to control Campylobacter in hosts in order to decrease the human burden. It is especially true for cattle where the environmental contamination by Campylobacter of human might be more important than the foodborne pathway, addressing the question of transmission routes for Campylobacter from ruminant to human, as no clear evidence is available. Nevertheless, since host-segregating markers allowed a higher accuracy in assignments of chicken isolates than MLST loci, it suggests that the importance of chicken in campylobacteriosis may be underestimated using MLST and could be more important than currently described. Finally, combining molecular and epidemiological approaches of source attribution may be of interest for further investigation of possible transmission routes for Campylobacter. In relation with French consumption habits and behaviour, this combining approach would be helpful to better understand campylobacteriosis epidemiology in France, and how different trends of source attribution can be obtained compared with our neighbouring countries.

Material and Methods

Clinical, animal, and environmental isolates

A total of 2132 C. jejuni isolates were collected between 2008 and 2016 in France, and characterized in this, and previous studies10,24,29,77,79. Clinical isolates were obtained from the National Reference Centre for Campylobacter and Helicobacter in France. In 2009, 3754 isolates from clinical cases of campylobacteriosis were obtained from 348 diagnostic bacteriology laboratories in public hospitals and private laboratories belonging to the National Surveillance System of campylobacteriosis in France80. C. jejuni was the most common species representing 81.4% (n = 3054) of Campylobacter spp. isolates80. Of these, C. jejuni isolates from the 10 most populated regions in France (n = 143) were considered for genotyping (CGF40, MLST, WGS) and included in this study24,29. In 2015, 5722 Campylobacter spp. isolates from campylobacteriosis were reported by laboratories from the National Surveillance System in France and identified by the National Reference Centre81. Of the 4704 C. jejuni isolates81, 371 isolates obtained from the 10 departments selected in 2009, were considered in this study. All isolates were successfully characterized using CGF4077, and a subset (n = 79) was characterized using MLST and WGS.

In addition, isolates originating from 4 potential sources of human infection were included in this study: (i) chickens, 644 isolates from 2008 and 2009, representative of the broiler production chain in France (national coverage of 9-month and 12-month sampling surveys performed at retail and slaughterhouse levels respectively)7,46; (ii) cattle, 42 isolates from 2013, and 649 from 2016 representative of the French cattle production (6-month sampling survey at slaughterhouse level allowing the analyses of 959 samples from 282 farms distributed among 32 French departments representative of the French production of cattle)10; (iii) environment, 122 isolates from 2013 to 2015 and from freshwater, sea water, sediment or mussels; (iv) pets, including 161 cat and dog isolates from 2014 and 2015. Isolates details and source publications are detailed in supplementary Table S1.

DNA extraction

Isolates stored at −80 °C, were subcultured onto Campylobacter selective blood-free agar (Karmali, Oxoid) in microaerobic conditions (85% N2, 10% CO2, 5% O2) at 42 °C for 48 h. Genomic DNA was extracted from one-day single-colony cultures incubated at 37 °C using the kit QiaAMP DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN) and quantified using the Qubit® 2.0 fluorometer and the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay kit (Invitrogen) following manufacturers’ recommendations.

Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF40)

CGF40 fingerprints were generated from 8 Multiplex PCRs according to primer sets previously published25 as well as experimental conditions29. The PCR results were converted into binary data corresponding to the absence (0) or the presence (1) of each of the 40 markers in the bacterial genomes and the CGF40 fingerprints of these 40 genes (CGF40) were stored into BioNumerics® software (v 7.6, Applied Maths, Belgium). Each binary CGF40 fingerprint was then used in the source attribution model to assign an origin to clinical C. jejuni isolates from 2009 and 2015. To perform this, all clinical, animal and environmental isolates were previously genotyped using CGF4010,29,77,79.

MultiLocus Sequence Typing (MLST)

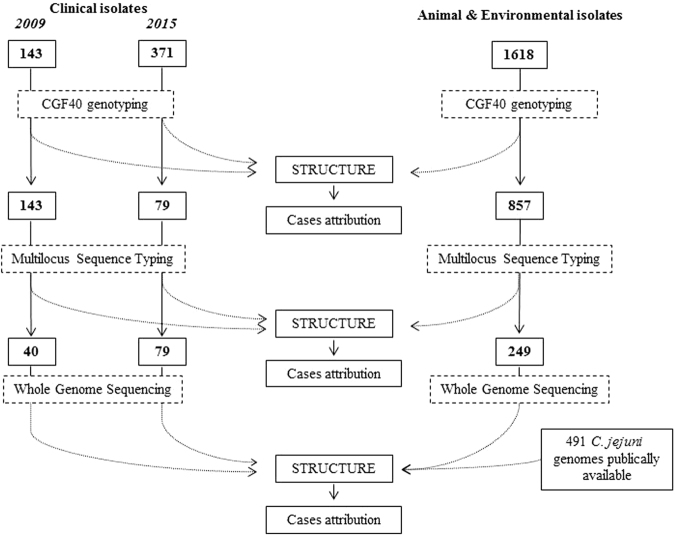

Alleles of the seven housekeeping MLST genes (aspA, glnA, gltA, glyA, pgm, tkt and uncA) were determined as previously described29. Alleles, sequence types (ST) and clonal complexes (CC) of isolates from cattle, pets, environment and clinical cases from 2015 were determined from whole genome sequence (WGS) data and by comparison of the sequences to the PubMLST database (http://pubmlst.org/campylobacter) on BIGSdb82. MLST characterization through WGS was performed using a subset of isolates from cattle, pets, environment and clinical cases from 2015, keeping the same proportion as for CGF40 genotypes. The global experimental design is presented in Fig. 4.

Figure 4.

Experimental design of the study.

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS)

Genomes were sequenced using the Ion Torrent technology on an Ion Torrent Proton machine (Life Technologies) according to previously published conditions24. Assemblies were produced by either MIRA version 4.0rc183 or SPAdes 3.1.184. Among 156 C. jejuni genomes newly sequenced, an average of 150 contigs was obtained with a median value of 62 contigs. The average of the total assembled sequence length is 1,715,087 bp (Supplementary Table S2).

French genomes sequenced in this study or previously24 were augmented with 491 genomes of C. jejuni isolated from chicken, ruminant, environmental water and wild birds from different countries and published in previous studies (Fig. 4)85–88. This gave a total of 859 C. jejuni genomes to constitute our study dataset (Supplementary Table S1) in which allelic variations among 15 host segregating markers24 was assessed for the source attribution study. These host-segregating markers were preferred to whole genome to perform source attribution, as their potential in source attribution has been demonstrated24, while the whole genome was shown to not improve assignment compared with MLST23.

Accuracy of the several genotypes data in source attribution through self-attribution tests

To assess the accuracy of attribution probabilities obtained with each genotyping method, self-attribution tests were performed within the different host populations, as described in previous studies using MLST or the host-segregating markers20,24. Random subsets of twenty isolates from each hosts population were assigned to a dataset from unknown origin and 10 independent self-attribution tests were performed to assign these isolates to a source. Accuracy of genotyping methods were considered as significantly different when no overlap of their 95% confidence interval were observed. Experimental conditions used were identical to those used to attribute a source to the clinical isolates.

Molecular source attribution of the clinical isolates

Probabilistic assignment of French human isolates from 2009 and 2015 to their most likely origin was performed separately using STRUCTURE software89. This software estimates the most likely origin of clinical isolates according to the similarity in alleles frequencies among the potential host populations and by assuming that each host population is characterized by its own set of allelic frequencies. CGF40 fingerprints, MLST profiles, and allelic profiles of the 15 host-segregating loci24 were used to attribute a source to clinical isolates according to previously published conditions24. Briefly, 100,000 burn-in steps with 100,000 subsequent iterations were run in STRUCTURE using the no-admixture model, assuming uncorrelated gene frequencies and using the STARTATPOPINFO parameter turned on. Clinical isolates were distinguished from host populations isolates using POPFLAG.

Host datasets used as a reference to probabilistically attribute a source to clinical isolates included isolates from 3 putative sources of contamination (chicken, cattle and environment) (Supplementary Table S1). Pets were added as a source of infection in a second analysis since their role in campylobacteriosis as reservoir or vector is not fully elucidated32,90,91.

Accession number(s)

Genome sequences generated as part of this study belong to the BioProject PRJNA357677 and were deposited in SRA (SRR6914212 to SRR6914375; see supplementary Table S2). The assemblies of genomes sequenced in earlier studies can be found in Dryad (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.28n35 and https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.m86k3) and NCBI (BioProject PRJNA312235 and BioProject PRJNA357677).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This publication made use of the Campylobacter Multi Locus Sequence Typing website (https://pubmlst.org/ campylobacter/) at the University of Oxford (Jolley & Maiden 2010, BMC Bioinformatics, 11:595). The authors thank Michèle Gourmelon from IFREMER and Francis Mégraud and Philippe Lehours from the National Reference Centre for Campylobacter and Helicobacter for kindly providing the environmental and clinical isolates of C. jejuni. This work was supported by the General Council of Côtes d’Armor (Conseil Départemental des Côtes d’Armor) and the General Directorate for Army (Direction Générale de l’Armement).

Author Contributions

A.T., S.K.S., M.C. and K.R. contributed to the conception and design of the study. A.T., V.R., S.Q., T.P., V.B., performed the laboratory analyses. E.H., F.T., P.L., produced whole genome sequences assemblies. A.T., E.H., G.M., L.M., contributed to bioinformaticss analyses of whole genome sequences. A.T., G.M., S.K.S., M.C., K.R., drafted the manuscript. All authors have substantially contributed to data interpretation, have critically reviewed the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-27558-z.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.EFSA & ECDC. The European Union summary report on trends and sources of zoonoses, zoonotic agents and food-borne outbreaks in 2015. EFSA Journal14, e04634-n/a, 10.2903/j.efsa.2016.4634 (2016).

- 2.Havelaar AH, Ivarsson S, Lofdahl M, Nauta MJ. Estimating the true incidence of campylobacteriosis and salmonellosis in the European Union, 2009. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:293–302. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812000568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bessede E, Lehours P, Labadi L, Bakiri S, Megraud F. Comparison of characteristics of patients infected by Campylobacter jejuni, Campylobacter coli, and Campylobacter fetus. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:328–330. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03029-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.EFSA. Scientific Opinion on Campylobacter in broiler meat production: control options and performance objectives and/or targets at different stages of the food chain. EFSA Journal9, 2105-n/a, 10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2105 (2011).

- 5.Tam CC, O’Brien SJ. Economic Cost of Campylobacter, Norovirus and Rotavirus Disease in the United Kingdom. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0138526. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mangen MJ, et al. Cost-of-illness and disease burden of food-related pathogens in the Netherlands, 2011. Int J Food Microbiol. 2015;196:84–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hue O, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for Campylobacter spp. contamination of broiler chicken carcasses at the slaughterhouse. Food Microbiol. 2010;27:992–999. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wittwer M, et al. Genetic diversity and antibiotic resistance patterns in a Campylobacter population isolated from poultry farms in Switzerland. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:2840–2847. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.6.2840-2847.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wieczorek K, Denis E, Lynch O, Osek J. Molecular characterization and antibiotic resistance profiling of Campylobacter isolated from cattle in Polish slaughterhouses. Food Microbiol. 2013;34:130–136. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thépault, A. et al. Prevalence of thermophilic Campylobacter in cattle production at slaughterhouse level in France and link between C. jejuni bovine strains and campylobacteriosis. Front Microbiol9, 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00471 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Holmberg M, Rosendal T, Engvall EO, Ohlson A, Lindberg A. Prevalence of thermophilic Campylobacter species in Swedish dogs and characterization of C. jejuni isolates. Acta Vet Scand. 2015;57:19. doi: 10.1186/s13028-015-0108-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acke E, et al. Prevalence of thermophilic Campylobacter species in household cats and dogs in Ireland. Vet Rec. 2009;164:44–47. doi: 10.1136/vr.164.2.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keller JI, Shriver WG. Prevalence of three Campylobacter species, C. jejuni, C. coli, and C. lari, using multilocus sequence typing in wild birds of the Mid-Atlantic region, USA. J Wildl Dis. 2014;50:31–41. doi: 10.7589/2013-06-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colles FM, Ali JS, Sheppard SK, McCarthy ND, Maiden MC. Campylobacter populations in wild and domesticated Mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos) Environ Microbiol Rep. 2011;3:574–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2011.00265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hald B, et al. Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in wild birds on Danish livestock farms. Acta Vet Scand. 2016;58:11. doi: 10.1186/s13028-016-0192-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Denis M, et al. Description and sources of contamination by Campylobacter spp. of river water destined for human consumption in Brittany, France. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2011;59:256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khan IU, et al. A national investigation of the prevalence and diversity of thermophilic Campylobacter species in agricultural watersheds in Canada. Water Res. 2014;61:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dingle KE, et al. Multilocus sequence typing system for Campylobacter jejuni. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:14–23. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.1.14-23.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mossong J, et al. Human Campylobacteriosis in Luxembourg, 2010–2013: A Case-Control Study Combined with Multilocus Sequence Typing for Source Attribution and Risk Factor Analysis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:20939. doi: 10.1038/srep20939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sheppard SK, et al. Campylobacter genotyping to determine the source of human infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1072–1078. doi: 10.1086/597402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mullner P, et al. Assigning the source of human campylobacteriosis in New Zealand: a comparative genetic and epidemiological approach. Infect Genet Evol. 2009;9:1311–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kittl S, Heckel G, Korczak BM, Kuhnert P. Source attribution of human Campylobacter isolates by MLST and fla-typing and association of genotypes with quinolone resistance. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dearlove BL, et al. Rapid host switching in generalist Campylobacter strains erodes the signal for tracing human infections. ISME J. 2016;10:721–729. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thépault, A. et al. Genome-Wide Identification of Host-Segregating Epidemiological Markers for Source Attribution in Campylobacter jejuni. Appl Environ Microbiol83, 10.1128/AEM.03085-16 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Taboada EN, et al. Development and validation of a comparative genomic fingerprinting method for high-resolution genotyping of Campylobacter jejuni. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:788–797. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00669-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carrillo, C. D. & Oyarzabal, O. A. In DNA Methods in Food Safety 185–204 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2014).

- 27.Taboada EN, Clark CG, Sproston EL, Carrillo CD. Current methods for molecular typing of Campylobacter species. J Microbiol Methods. 2013;95:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clark CG, et al. Comparison of molecular typing methods useful for detecting clusters of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli isolates through routine surveillance. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:798–809. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05733-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thépault, A. et al. A representative overview of the genetic diversity and lipooligosaccharide sialylation in Campylobacter jejuni along the broiler production chain in France and its comparison with human isolates. Int J Food Microbiol, 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2018.03.010 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Wilson DJ, et al. Tracing the source of campylobacteriosis. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosner BM, et al. A combined case-control and molecular source attribution study of human Campylobacter infections in Germany, 2011–2014. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5139. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05227-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mughini Gras L, et al. Increased risk for Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli infection of pet origin in dog owners and evidence for genetic association between strains causing infection in humans and their pets. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:2526–2535. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813000356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strachan NJ, et al. Attribution of Campylobacter infections in northeast Scotland to specific sources by use of multilocus sequence typing. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:1205–1208. doi: 10.1086/597417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mughini Gras L, et al. Risk factors for campylobacteriosis of chicken, ruminant, and environmental origin: a combined case-control and source attribution analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ravel A, et al. Source attribution of human campylobacteriosis at the point of exposure by combining comparative exposure assessment and subtype comparison based on comparative genomic fingerprinting. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183790. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porras-Hurtado L, et al. An overview of STRUCTURE: applications, parameter settings, and supporting software. Front Genet. 2013;4:98. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2013.00098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levesque S, et al. Campylobacteriosis in urban versus rural areas: a case-case study integrated with molecular typing to validate risk factors and to attribute sources of infection. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83731. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Haan CP, Kivisto RI, Hakkinen M, Corander J, Hanninen ML. Multilocus sequence types of Finnish bovine Campylobacter jejuni isolates and their attribution to human infections. BMC Microbiol. 2010;10:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Haan CP, Kivisto R, Hakkinen M, Rautelin H, Hanninen ML. Decreasing trend of overlapping multilocus sequence types between human and chicken Campylobacter jejuni isolates over a decade in Finland. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:5228–5236. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00581-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boysen L, et al. Source attribution of human campylobacteriosis in Denmark. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142:1599–1608. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813002719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neimann J, Engberg J, Molbak K, Wegener HC. A case-control study of risk factors for sporadic campylobacter infections in Denmark. Epidemiol Infect. 2003;130:353–366. doi: 10.1017/S0950268803008355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Doorduyn Y, et al. Risk factors for indigenous Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli infections in The Netherlands: a case-control study. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:1391–1404. doi: 10.1017/S095026881000052X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pires SM, Vigre H, Makela P, Hald T. Using outbreak data for source attribution of human salmonellosis and campylobacteriosis in Europe. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2010;7:1351–1361. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Domingues AR, Pires SM, Halasa T, Hald T. Source attribution of human campylobacteriosis using a meta-analysis of case-control studies of sporadic infections. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140:970–981. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811002676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hue O, et al. Campylobacter contamination of broiler caeca and carcasses at the slaughterhouse and correlation with Salmonella contamination. Food Microbiol. 2011;28:862–868. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guyard-Nicodeme M, et al. Prevalence and characterization of Campylobacter jejuni from chicken meat sold in French retail outlets. Int J Food Microbiol. 2015;203:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gallay A, et al. Risk factors for acquiring sporadic Campylobacter infection in France: results from a national case-control study. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:1477–1484. doi: 10.1086/587644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DGAl. Plan de surveillance 2012 de la contamination par Campylobacter et Salmonella des viandes bovines et porcines à la distribution. NOTE DE SERVICE DGAL/SDPRAT/N2013-8184. (2013).

- 49.Ghafir Y, China B, Dierick K, De Zutter L, Daube G. A seven-year survey of Campylobacter contamination in meat at different production stages in Belgium. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;116:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wong TL, et al. Prevalence, numbers, and subtypes of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in uncooked retail meat samples. J Food Prot. 2007;70:566–573. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-70.3.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Noormohamed A, Fakhr MK. A higher prevalence rate of Campylobacter in retail beef livers compared to other beef and pork meat cuts. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10:2058–2068. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10052058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strachan NJ, et al. Source attribution, prevalence and enumeration of Campylobacter spp. from retail liver. Int J Food Microbiol. 2012;153:234–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inglis GD, McAllister TA, Larney FJ, Topp E. Prolonged survival of Campylobacter species in bovine manure compost. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:1110–1119. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01902-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maynaud G, et al. Persistence and Potential Viable but Non-culturable State of Pathogenic Bacteria during Storage of Digestates from Agricultural Biogas Plants. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1469. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Repérant, E., Nagard, B., Pourcher A-M., Druilhe C. & M., D. Thermotolerant Campylobacter spp: detection and enumeration during anaerobic digestion of livestock effluents in 5 biogas plants. Abstracts of the 19th International Workshop on Campylobacter, Helicobacter and related organisms (CHRO), 10–14 September 2017, Nantes, France., p. 292 (2017).

- 56.Clark CG, et al. Characterization of waterborne outbreak-associated Campylobacter jejuni, Walkerton, Ontario. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1232–1241. doi: 10.3201/eid0910.020584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gourmelon M, et al. Occurrence of Campylobacter spp. in shellfish-harvesting areas and their catchments in France. Abstracts of the 18th International Workshop on Campylobacter, Helicobacter and related organisms (CHRO), 1–5 November 2015, Rotorua, New Zealand. Abstract. 2015;O106:p. 91. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cody AJ, et al. Wild bird-associated Campylobacter jejuni isolates are a consistent source of human disease, in Oxfordshire, United Kingdom. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2015;7:782–788. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pintar KDM, et al. A Comparative Exposure Assessment of Campylobacter in Ontario, Canada. Risk Anal. 2017;37:677–715. doi: 10.1111/risa.12653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ravel A, Pintar K, Nesbitt A, Pollari F. Non food-related risk factors of campylobacteriosis in Canada: a matched case-control study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:1016. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3679-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schonberg-Norio D, et al. Swimming and Campylobacter infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1474–1477. doi: 10.3201/eid1008.030924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tissier A, Denis M, Hartemann P, Gassilloud B. Development of a rapid and sensitive method combining a cellulose ester microfilter and a real-time quantitative PCR assay to detect Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli in 20 liters of drinking water or low-turbidity waters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:839–845. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06754-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuusi M, et al. An outbreak of gastroenteritis from a non-chlorinated community water supply. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:273–277. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.009928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gallay A, et al. A large multi-pathogen waterborne community outbreak linked to faecal contamination of a groundwater system, France, 2000. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12:561–570. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.French NP, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from wild-bird fecal material in children’s playgrounds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:779–783. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01979-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Riordan T, Humphrey TJ, Fowles A. A point source outbreak of campylobacter infection related to bird-pecked milk. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;110:261–265. doi: 10.1017/S0950268800068187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gourmelon, M. et al. Campylobacter jejuni at the level of a coastal catchment in France. Abstracts of the 19th International Workshop on Campylobacter, Helicobacter and related organisms (CHRO), 10–14 September 2017, Nantes, France., p. 314 (2017).

- 68.Mughini-Gras L, et al. Quantifying potential sources of surface water contamination with Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. Water Res. 2016;101:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2016.05.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Parsons BN, et al. Typing of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from dogs by use of multilocus sequence typing and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:3466–3471. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01046-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Colles FM, Jones K, Harding RM. & Maiden, M. C. Genetic diversity of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from farm animals and the farm environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:7409–7413. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7409-7413.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sopwith W, et al. Identification of potential environmentally adapted Campylobacter jejuni strain, United Kingdom. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1769–1773. doi: 10.3201/eid1411.071678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kwan PS, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Campylobacter jejuni populations in dairy cattle, wildlife, and the environment in a farmland area. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:5130–5138. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02198-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Thépault, A., Rose, V., Queguiner, M., Chemaly, M. & Rivoal, K. Pets: a reservoir for highly diverse Campylobacter jejuni and a potential source of human contamination. (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.Smid JH, et al. Practicalities of using non-local or non-recent multilocus sequence typing data for source attribution in space and time of human campylobacteriosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55029. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Griekspoor P, Engvall EO, Akerlind B, Olsen B, Waldenstrom J. Genetic diversity and host associations in Campylobacter jejuni from human cases and broilers in 2000 and 2008. Vet Microbiol. 2015;178:94–98. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Griekspoor P, Hansbro PM, Waldenstrom J, Olsen B. Campylobacter jejuni sequence types show remarkable spatial and temporal stability in Blackbirds. Infect Ecol Epidemiol. 2015;5:28383. doi: 10.3402/iee.v5.28383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rose, V. et al. A stable and highly diverse genetic structure in clinical Campylobacter jejuni isolates in 2009 and 2015. Abstracts of the 19th International Workshop on Campylobacter, Helicobacter and related organisms (CHRO), 10-14 September 2017, Nantes, France., p. 148 (2017).

- 78.Van Cauteren D, et al. Community Incidence of Campylobacteriosis and Nontyphoidal Salmonellosis, France, 2008-2013. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2015;12:664–669. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2015.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thépault, A. et al. A large scale survey describing the relationship between different animal reservoirs and human campylobacteriosis. International Association for Food Protection Annual Meeting, Saint Louis, Missouri, United States, July 31–August 3 (Communication orale). (2016).

- 80.King, L., Lehours, P. & Mégraud, F. Bilan de la surveillance des infections à Campylobacter chez l’homme en France en 2009. https://www.cnrch.fr/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/CNRCH-Bilan-surveillance-Campylobacter-reseau-2009.pdf (2010).

- 81.Van Cauteren, D., Lehours, P., Bessède, E., De Valk, H. & Mégraud, F. Bilan de la surveillance des infections à Campylobacter en France en 2015 https://www.cnrch.fr/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Bilan_Campylobacter_2015.pdf (2015).

- 82.Jolley KA. & Maiden, M. C. BIGSdb: Scalable analysis of bacterial genome variation at the population level. BMC Bioinformatics. 2010;11:595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chevreux, B., Wetter, T. & Suhai, S. In German conference on bioinformatics. 45–56 (Heidelberg).

- 84.Bankevich A, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yahara, K. et al. Genome-wide association of functional traits linked with Campylobacter jejuni survival from farm to fork. Report No. 2167-9843, (PeerJ Preprints, 2016). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 86.Sheppard SK, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies vitamin B5 biosynthesis as a host specificity factor in Campylobacter. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:11923–11927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305559110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sheppard SK, et al. Cryptic ecology among host generalist Campylobacter jejuni in domestic animals. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:2442–2451. doi: 10.1111/mec.12742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pascoe B, et al. genes for local bacteria: evidence of allopatry in the genomes of transatlantic Campylobacter populations. PeerJ Preprints. 2016;4:e2638v2631. doi: 10.1111/mec.14176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pritchard, J., Wen, X. & Falush, D. Documentation for structure software: Version 2.3. University of Chicago, Chicago, IL (2010).

- 90.Workman SN, Mathison GE, Lavoie MC. Pet dogs and chicken meat as reservoirs of Campylobacter spp. in Barbados. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2642–2650. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2642-2650.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Olson, C. K., Ethelberg, S., van Pelt, W. & Tauxe, R. V. In Campylobacter, Third Edition (American Society of Microbiology, 2008).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.