Abstract

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) are irreversibly inhibited by organophosphorus pesticides through formation of a covalent bond with the active site serine. Proteins that have no active site serine, for example albumin, are covalently modified on tyrosine and lysine. Chronic illness from pesticide exposure is not explained by inhibition of AChE and BChE. Our goal was to produce a monoclonal antibody that recognizes proteins diethoxyphosphorylated on tyrosine. Diethoxyphosphate-tyrosine adducts for 13 peptides were synthesized. The diethoxyphosphorylated (OP) peptides crosslinked to 4 different carrier proteins were used to immunize, boost, and screen mice. Monoclonal antibodies were produced with hybridoma technology. Monoclonal antibody depY was purified and characterized by ELISA, Western blotting, Biacore and Octet technology to determine binding affinity and binding specificity. DepY recognized diethoxyphospho-tyrosine independent of the amino acid sequence around the modified tyrosine and independent of the identity of the carrier protein or peptide. It had an IC50 of 3 × 10−9 M in a competition assay with OP tubulin. Kd values measured by Biacore and OctetRED96 were 10−8 M for OP-peptides and 1 × 10−12 M for OP-proteins. The limit of detection measured on Western blots hybridized with 0.14 μg/mL depY was 0.025 μg human albumin conjugated to YGGFL-OP. DepY was specific for diethoxyphospho-tyrosine (chlorpyrifos oxon adduct) as it failed to recognize diethoxyphospho-lysine, phosphoserine, phospho-tyrosine, phospho-threonine, dimethoxyphospho-tyrosine (dichlorvos adduct), dimethoxyphospho-serine, monomethoxyphospho-tyrosine (aged dichlorvos adduct), and cresylphospho-serine. In conclusion, a monoclonal antibody that specifically recognizes diethoxyphospho-tyrosine adducts has been developed. The depY monoclonal antibody could be useful for identifying new biomarkers of OP exposure.

Keywords: Chlorpyrifos oxon, dichlorvos, tyrosine adduct, antibody, mass spectrometry, Biacore, OctetRED96

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Organophosphorus pesticides can have the same toxic effects as chemical warfare agents because they share the same mechanism of acute toxicity, namely irreversible inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE).1 Furthermore, organophosphorus pesticides are readily available to persons intent on harming others. Taliban insurgents have poisoned schoolgirls in Afghanistan with parathion in several attacks. Proof of exposure can be obtained from blood samples drawn more than a month after the event through mass spectrometry analysis of diethoxyphospho-tyrosine adducts on blood proteins. A study by van der Schans found that the adduct on tyrosine 411 of human albumin was detectable in blood drawn 49 days after poisoning by chlorpyrifos.2 The same blood sample contained no detectable adducts on butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) because new BChE molecules had replaced the inhibited BChE. It is expected that a monoclonal antibody specific for diethoxyphospho-tyrosine could be used to detect exposure in a device similar to the one developed by Rapid Pathogen Screening, Inc.3 for nerve agent exposure. Such a device is simple to use and requires no expensive mass spectrometers.

A second application of a monoclonal antibody to diethoxyphosphorylated (OP) tyrosine would be for understanding chronic neurotoxicity from organophosphorus pesticide exposure. To date the only proteins known to be modified by organophosphorus pesticides in vivo are acetylcholinesterase, butyrylcholinesterase, carboxylesterase, and albumin. Acyl peptide hydrolase in red blood cells is a possible target, but evidence for reaction with organophosphorus pesticides in vivo has been demonstrated only in rats and only with dichlorvos.4 The proposed monoclonal antibody could be used to immunopurify diethoxyphospo-tyrosine-containing proteins in preparation for analysis by mass spectrometry. This would test the hypothesis that organophosphorus toxicants modify many proteins and that the consequence of modification is disruption of signaling pathways.5

The strategy we used to make our monoclonal antibody to diethoxyphospho-tyrosine is based on the strategy that produced the monoclonal antibody to phospho-tyrosine. 6 We conjugated 4 carrier proteins to 13 different OP-tyrosine peptides. Five conjugates were used as immunogen, a different 5 for boosting, and a different three for screening.

Materials and Methods

The following were from Sigma-Aldrich: human albumin, (accession P02768) Fluka 05418; bovine albumin (P02769) A-2153 and A-8022; ovalbumin (P01012) A-5503; lysozyme (P00698) L-6876; casein (mixture of isoforms P02662, PO2663, P02666, P02668) C-5890; aprotinin bovine (P00974) A-1153; Anti O-Phospho-tyrosine monoclonal antibody clone PY20 (Sigma P-4110); O-Phospho-L-tyrosine P-9405; 2-[Nmorpholino] ethanesulfonic acid M-8250; O-Phenylenediamine dihydrochloride P-8287; 1- ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide.HCl, Fluka 03450; Paraoxon-ethyl D-9286.

The following were from Thermo Scientific: Sulfo-NHS, N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide 24510; 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine solution N301; Nunc-Immuno MaxiSorp surface flat bottom 96 well polystyrene plate; Immulon 2HB Thermo 3455. The following were from Chem Service Inc: Chlorpyrifos oxon MET-674B; Dichlorvos PS-89. Peptides were purchased from American Peptide Co., Sigma-Aldrich, and Genscript. Mouse albumin (P07724) was from Innovative Research Inc., Novi, MI. Porcine tubulin (mixture of alpha and beta P02550, Q2XVP4, Q767L7, P02554) was from Cytoskeleton Inc T240. Protein G agarose was from Protein Mods LLC, Madison, WI. Horse anti-mouse IgG (heavy and light chains) conjugated to HRP was from Cell Signaling 7076. CNBr-activated Sepharose fast flow was from Amersham Biosciences 17-0981-01.

OP-Tyrosine peptides

Diethoxyphospho-tyrosine adducts formed spontaneously when peptides were incubated with an excess of chlorpyrifos oxon (CPO) or paraoxon at high pH. For example 70 mg of peptide YGGFL were incubated in 12 mL of 1 M Tris pH 10.8 with a 33 fold molar excess of paraoxon (0.1 mL of 4.16 M paraoxon) for 3 days at 37°C. During this time the pH dropped to pH 9. Unreacted paraoxon was separated from p-nitrophenol and peptides by extraction with chloroform. The yellow p-nitrophenol was separated from peptides on a C18 Alltech 900 mg cartridge or on a SepPak C18 cartridge (Waters) where the p-nitrophenol eluted with 0.1% (v/v) TFA in water, and the peptides eluted with 3 to 50% (v/v) acetonitrile. OP-labeled peptide was separated from unlabeled peptide by HPLC on a C18 Phenomenex column using a 1 h gradient from 0.1% TFA in water to 60% (v/v) acetonitrile. At each step, fractions containing the OP-peptide and the unlabeled peptide were identified by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry (4800 MALDI-TOF-TOF mass spectrometer, AB Sciex). Fragmentation analysis of the OP-peptide identified tyrosine as the residue modified by OP.

In a second example, 80 mg of peptide RSLYAS in 5.5 mL of 0.1 M sodium carbonate pH 10 was incubated with a 30-fold molar excess of CPO at 24°C for 24 h. Comparison of peak intensities in the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer showed that 60% of the peptide had been diethoxyphosphorylated on tyrosine. Excess CPO was extracted into chloroform. The OP-peptide was isolated by HPLC as above.

Quantitation of OP-peptide

The relationship between peptide quantity and absorbance in the UV range was established as follows. Peptide concentration was determined by the Protein Structure core facility at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Triplicate volumes of 3 funlabeled and 3 OP-peptide solutions were hydrolyzed and the amino acids quantified by reaction with ninhydrin. The absorbance spectra of the same peptide solutions were acquired on a Gilford spectrophotometer. Unlabeled peptides containing one tyrosine but no other aromatic residues, had an absorbance peak at 275 nm and an absorbance of 1500 for a 1 M solution in water measured in a 1 cm quartz cuvette (E275nm = 1500 M−1 cm−1). The same peptides modified on tyrosine by OP had an absorbance peak at 265 nm and an absorbance of 430 for a 1 M solution in water in a 1 cm quartz cuvette (E265nm = 430 M−1 cm−1).

Coupling of OP-tyrosine peptides to carrier proteins

OP-peptides were conjugated to carrier proteins using a procedure adapted from Belabassi et al. 7 For example, 1.9 mg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 720 μl of 0.1 M 2-[N-morpholino]ethanesulfonic acid (MES) pH 6.2 was conjugated to 4 mg of OP-peptide in the presence of 2.1 mg N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide (Sulfo-NHS) and 4.7 mg of 1-ethyl-3-(3 dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDC). The pH was adjusted to pH 6.2 with 5 M NaOH measured with pH strips. The 0.8 mL reaction volume was mixed in a rotating mixer (Roto-Torque rotating mixer, Cole Parmer Instruments) for 3 h at room temperature. Excess reagents were separated from OP-peptide-BSA by passage through a Dextran desalting column 5K molecular weight cut off.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to quantify number of OP-peptides crosslinked to carrier proteins

The number of OP-peptides crosslinked to the carrier proteins BSA, human serum albumin (HSA), ovalbumin (OVA) and lysozyme was quantified from the shift in mass of the carrier protein observed in the MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer, as described by Belabassi et al.7 Proteins were spotted onto a MALDI target plate with sinapinic acid. Mass data were acquired in a 4800 MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer (AB Sciex) set to linear high mass positive mode, range 30,000 to 100,000 Da, bin size 20 ns, detector voltage multiplier 0.95, delayed extraction 1650 nsec, low mass gate enabled, low mass gate offset 100 Da, collected 3000 shots with laser voltage set to 7800 V. The list of OP-tyrosine peptides conjugated to BSA, HSA, OVA and lysozyme is in Table S1 in the Supporting Information section. Samples are in 0.1 M MES buffer pH 6.2 at a concentration of 2.5 mg protein per mL.

Production of monoclonal antibodies

Antibodies were generated in mice by Syd Labs, Inc. using standard hybridoma fusion technology. Mice were immunized with BSA conjugated to 5 peptides diethoxyphosphorylated on tyrosine: PVYSR-OP, LYGLPR-OP, KYA-OP, HYRGPA-OP, and EPNVSY-OP. Mice were boosted with OVA conjugated to 3 peptides diethoxyphosphorylated on tyrosine: RSLYAS-OP, YGGFL-OP, YPF-OP and HSA conjugated to PPYRM-OP and QYDVRK-OP. Hybridomas were screened using lysozyme conjugated to RARYEM-OP, GGYR-OP, and KYK-OP. Thirty hybridoma culture media were rescreened with human albumin and mouse albumin modified by CPO. Hybridoma cells in well 3B9 were grown in 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium containing proprietary components (ProMab M10009). Monoclonal antibody in 580 mL culture medium was purified on a 10 mL column of Protein G agarose, yielding 19 mg of monoclonal antibody in 0.055 M citrate, 0.44 M potassium phosphate pH 6.7. The purified monoclonal antibody was named depY where dep is an abbreviation for diethoxyphosphate and Y is the code name for tyrosine.

DepY immobilized on Sepharose beads

CNBr-activated Sepharose (1 g) washed and swollen to 3 mL, was coupled to 4.7 mg of monoclonal antibody depY in 1 mL of 0.15 M sodium bicarbonate, 0.5 M NaCl pH 8. The quantity of bound depY was calculated from absorbance at 280 nm of the unbound supernatant compared to absorbance at 280 nm before crosslinking. It was calculated that 4.5 mg of depY was covalently bound to 3 mL Sepharose. The beads were washed with pH 8 buffer, 1 M NaCl, pH 3.5 buffer, and phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Beads were stored in 15 mL of PBS, 0.1% (w/v) azide. A 0.1 mL suspension contained 20 μl beads covalently bound to 30 μg of depY.

Dichlorvos modified peptide and immuno MALDI

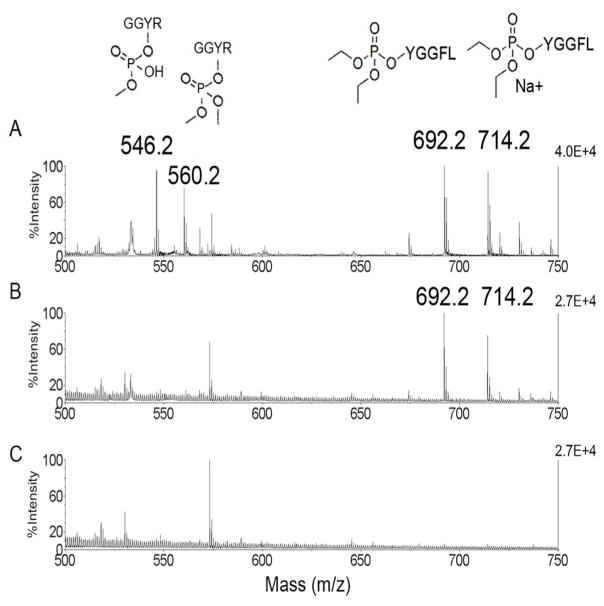

Dichlorvos makes the dimethoxyphospho adduct and ages to the monomethoxyphospho adduct on tyrosine. 8, 9 Chlorpyrifos oxon makes the diethoxyphospho adduct on tyrosine and does not age. 2, 10–13 To determine whether depY could distinguish between dimethoxyphospho-tyrosine (from dichlorvos) and diethoxyphospho-tyrosine (from chlorpyrifos) we synthesized the corresponding adducts on tyrosine in short peptides. Synthesis of the diethoxyphospho-tyrosine adduct on peptide YGGFL is described above. Synthesis of the dimethoxyphospho-tyrosine adduct on peptide GGYR was performed as follows. Peptide GGYR (Sigma G5386), 2.7 mM in 1 M Tris pH 10, was incubated with 81 mM dichlorvos at 37°C. After 12 days about 50% of the peptide was modified on tyrosine. The dichlorvos modified peptide was partially purified by HPLC on a C18 column. The identity of the modified residue, tyrosine, was determined by fragmentation analysis in the 4800 MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer. Binding to immobilized depY was evaluated by incubating 20 μl beads in 0.3 mL PBS with 0.01 mL of dichlorvos-GGYR and diethoxyphospho-tyrosine peptide YGGFL-OP for 2 h at room temperature. The negative control sample to check for nonspecific binding to Sepharose beads (no antibody) contained beads incubated with dichlorvos-GGYR and YGGFL-OP. Beads were washed with PBS and water. Bound peptides were released with 50% acetonitrile,1% TFA and visualized by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry with α-Cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid matrix. Monoisotopic masses for the positively charged ions are 560.2 (dimethoxyphospho-tyrosine adduct on GGYR), 546.2 (monomethoxyphospho-tyrosine adduct on GGYR) and 692.2 for YGGFL-OP (diethoxyphospho-tyrosine adduct on YGGFL).

Proteins treated with chlorpyrifos oxon

OP-proteins for ELISA and Western blots were produced by incubating 0.5 mg/mL bovine tubulin, porcine tubulin, human albumin, mouse albumin, casein, lysozyme, and aprotinin with 1.5 mM CPO in 20 mM TrisCl pH 8.9, 0.01% azide at room temperature for 7 days. Tryptic peptides of CPO-treated proteins were analyzed by LC-MS/MS to identify and quantify the modified residues. Appendix S1 in the Supporting Information section lists the modified residues and the extent of modification.

O-phospho-tyrosine conjugated to human albumin

Phosphorylated tyrosine is naturally present on many proteins in all cells.14 To determine whether a commercially available monoclonal antibody to phosphorylated tyrosine recognizes diethoxyphosphorylated-tyrosine we performed the following experiment. We prepared a positive control by crosslinking O-phospho-L-tyrosine to human albumin. O-phospho-L-tyrosine (2 mg in 0.5 mL 0.1 M MES, 0.9 M NaCl, 0.02% azide pH 4.7) was crosslinked to 0.2 mL of 10 mg/mL human albumin with EDC. After 2 h reaction at room temperature the sample was freed of excess reagents on a 5 mL desalting column.

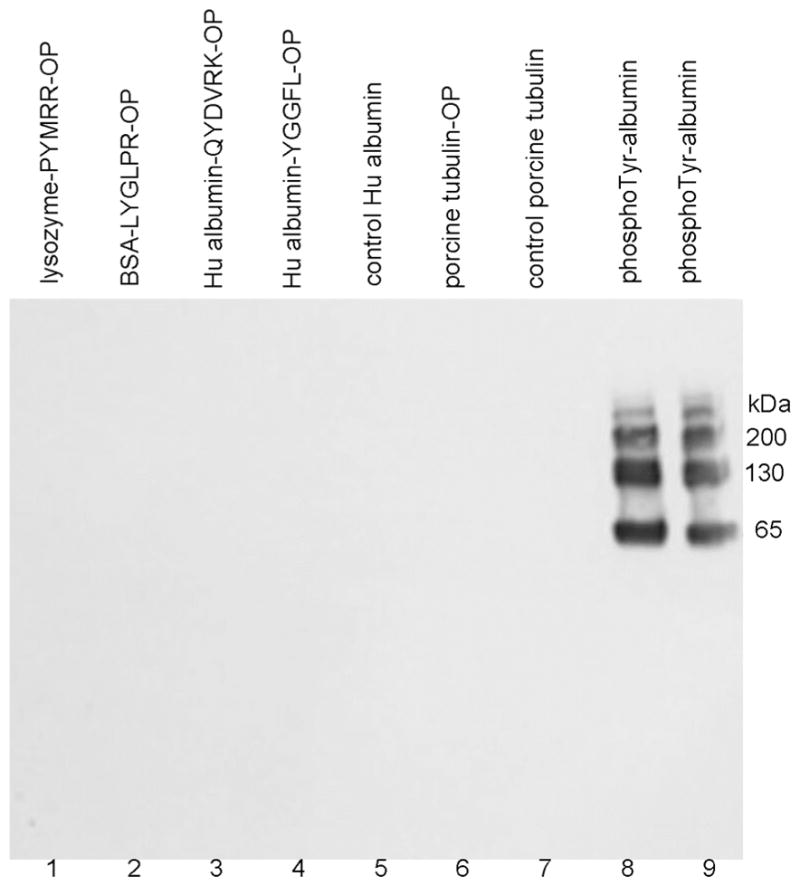

A set of diethoxyphosphorylated proteins and the positive control were subjected to SDS gel electrophoresis followed by transfer to a PVDF membrane. The membrane was hybridized with 0.5 μg/mL of anti O-phospho-L-tyrosine monoclonal antibody clone PY20 (Sigma P-4110) and visualized with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody.

Lysine-OP conjugated to human albumin

To determine whether depY recognized lysine-OP, we prepared diethoxyphospholysine by incubating 2 mM L-lysine in 25 mM ammonium bicarbonate pH 8 with 20 mM CPO at 37°C for 9 days. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry indicated that 50% of the 147 Da lysine had acquired an added mass of 136 to make an adduct of mass 283 Da. Excess CPO and unreacted lysine were separated from lysine-OP by passage through a C18 cartridge.

Human albumin (1.9 mg) in 800 μl of 0.1 M MES pH 6.2 was conjugated to 0.45 mg of lysine-OP in the presence of 2.1 mg Sulfo-NHS and 4.7 mg EDC. The pH was adjusted to pH 6.2 with 5 M NaOH measured with pH strips. The 0.8 mL reaction volume was mixed in a rotating mixer for 3 h at room temperature. Excess reagents were removed by passage through a Dextran desalting column 5K molecular weight cut off. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry in sinapinic acid indicated that each albumin molecule bound 14 lysine-OP.

The human albumin-lysine-OP conjugate was coated on an immulon plate at 1 μg per well. Control samples were human albumin (no OP) and the positive control, tubulin-OP. Binding of depY was evaluated by ELISA using a depY concentration of 0.2 μg in 100 μl.

ELISA

Immulon 96-well plates were coated with 1 μg antigen in 100 μL of pH 9.6 coating buffer (3 g Na2CO3 and 6 g NaHCO3 in 1 L water) per well at 4°C overnight. Wells were blocked with 1% (w/v) BSA in Tris buffered saline 20 mM TrisCl, 0.15 M NaCl pH 7.4 (TBS) at room temperature for 1 h, followed by one wash with TBS containing 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20 (TBST). Monoclonal antibody depY diluted to 0.02 μg/100 μL in 1% BSA/TBS was added to the wells. The plate was rocked 2 h at room temperature, washed 3 times with TBST, and incubated with horse radish peroxidase (HRP) conjugated anti-mouse IgG, 5 μL diluted into 20 mL of 1% BSA/TBS for 2 h at room temperature. After the plate was washed 5 times with TBST, wells received 100 μL of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) or a freshly prepared solution of O-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (4 mg tablet in 10 mL of 0.05 M phosphate-citrate pH 5.0 with 10 μl of 30% hydrogen peroxide). The HRP reaction was stopped after 20 min by addition of 100 μL of 0.16 M sulfuric acid. Absorbance at 405 nm for TMB reactions, or at 490 nm for O-phenylenediamine reactions, was recorded on a BioTek 96-well plate reader (Winooski, VT).

Western blot

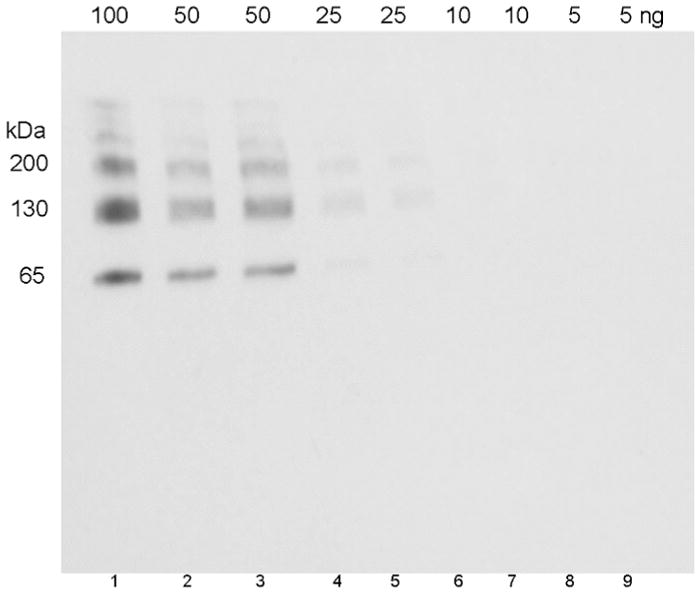

Samples containing 1 μg protein (Figure 2) or 5 to 100 ng protein (Figure 4) were electrophoresed on 4–20% (w/v) gradient precast gels (BioRad 456-8093). After electrophoresis proteins were electroblotted onto PVDF membrane. The membrane was hybridized with depY diluted to 0.14 μg/mL in 5% (w/v) non-fat milk in TBS at 4°C overnight. The membrane was washed 3 times with TBST and hybridized with 1:10,000 diluted secondary antibody (horse anti-mouse IgG conjugated to HRP) for 1 h at room temperature in 5% non-fat milk in TBS. Excess reagents were washed off with TBST. The signal was developed with Pierce ECL Western Blotting reagent (#32209) detected on X-ray film.

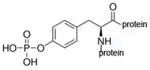

Figure 2.

Western blot hybridized with monoclonal antibody PY20 to phosphotyrosine. The SDS gel was loaded with 1 μg protein per lane. 1) lysozyme-PYMRR-OP, 2) BSA-LYGLPR-OP, 3) human albumin-QYDVRK-OP, 4) human albumin-YGGFL-OP, 5) control human albumin, 6) tubulin-OP, 7) control tubulin, 8) and 9) O-phospho-L-tyrosine-crosslinked to human albumin. Monoclonal antibody PY20 specifically recognized phosphotyrosine-labeled protein, but did not recognize diethoxyphosphorylated tyrosine labeled proteins.

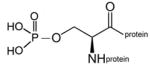

Figure 4.

Limit of detection of human albumin conjugated to OP-YGGFL (5 OP-peptides bound per albumin molecule). The SDS gel was loaded with 100 to 5 ng of antigen per lane. The Western blot was hybridized with 0.14 μg/mL depY.

Kd evaluated by competition ELISA

The ability of tubulin-OP to bind depY was evaluated by competition ELISA. A 96-well plate was coated with 1 μg per well of human albumin-QYDVRK-OP. The depY antibody diluted to 0.1 μg/mL in 1% BSA, pH 7.4 buffer was incubated with porcine tubulin-OP concentrations ranging from 10−17 M to 10−7 M for 1 h at room temperature. The mixtures were added to the 96-well plate and the availability of depY to bind the OPprotein in the wells was quantified from the signal intensity of the bound HRP-conjugated secondary antibody.

Kd of OP-peptides evaluated by Biacore analysis

Binding experiments were performed on a Biacore T-200 instrument at 25°C. The depY antibody was immobilized on a CM5 chip using EDC/NHS for crosslinking in 10 mM sodium acetate pH 5. Unoccupied sites were blocked with 1 M ethanolamine. OP-peptides in 10 mM HEPES buffer pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% (v/v) polyoxyethylenesorbitan were injected at a flow rate of 30 μL/min. Rate constants were measured for the following OP-peptides and the corresponding unlabeled peptide controls: YPF-OP and YPF; GGYP-OP and GGYP; LYGLPR-OP and LYGLPR; PPYRM-OP and PPYRM. OP-peptide concentrations ranged from 0 to 1000 nM. After each assay the chip was regenerated with 10 mM glycine pH 1.75. The surface plasmon resonance signal obtained in each individual reaction cycle was recorded as a sensorgram, which is a real-time pattern plotted in response units versus time. BIAevaluation T-200 soft-ware (version 2.0) was used to calculate the equilibrium binding affinity constant Kd. Chi square analysis was carried out between the actual sensorgram and the sensorgram generated from the BIAnalysis software to determine the accuracy of the analysis. A Chi square value below 1 is highly significant.

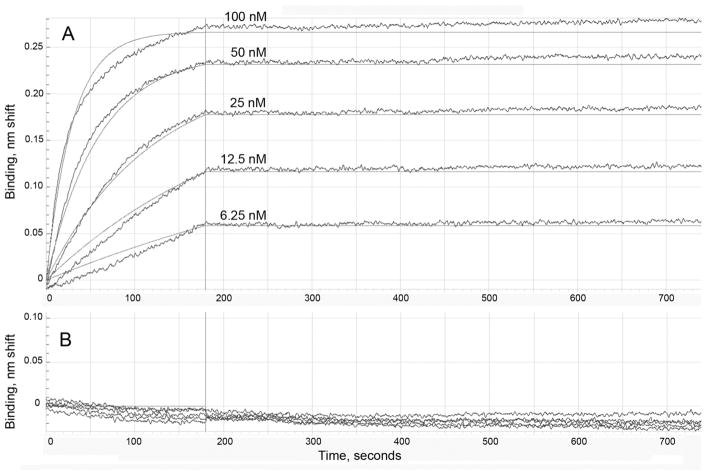

Kd of OP-proteins evaluated by Bio-Layered Interferometry on OctetRED96

Assays were performed by Dr. Udaya Yerramalla on the OctetRED96 instrument using Bio-Layer Interferometry, a label-free technology for measuring bio-molecular interactions. The depY antibody at 20 μg/mL was captured on a biosensor which had been coated with anti-mouse IgG Fc. The following samples were tested for binding to depY: porcine tubulin-OP and porcine tubulin control; casein-OP and casein control; ovalbumin-YPF-OP and ovalbumin-YPF control; BSA-LYGLPR-OP and BSA-LYGLPR control. Rate constants for association and dissociation were measured using sample concentrations of 100, 50, 25, 12.5, or 6.25 nM in PBS, 0.01% BSA, 0.002% Tween-20. Probes were dipped into buffer to measure the dissociation rate. The sensor surface was regenerated after each binding experiment with 10 mM glycine pH 1.75. The traces were processed using ForteBio Data Analysis Software (version 8.0, Pall ForteBio, CA, USA) and fit globally using a simple 1:1 Langmuir interaction model.

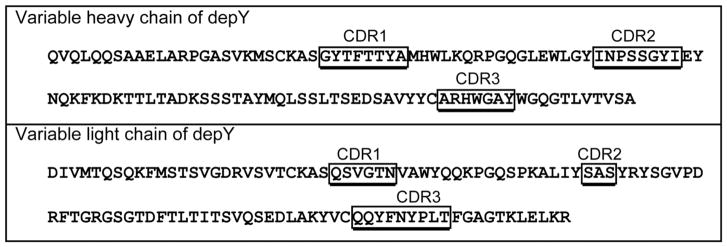

Sequence and Isotype of purified depY

Syd Labs Inc. sequenced the cDNA of depY using 5′ and 3′ RACE (Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends). To verify that the correct sequence had been captured from the hybridoma cells, the cDNA was cloned into expression vectors, transiently expressed in HEK293 cells and the secreted recombinant antibody purified on Protein A agarose beads. The recombinant depY antibody was tested by ELISA against a panel of 12 diethoxyphospho-tyrosine proteins and unlabeled control proteins. A duplicate 96-well plate was hybridized with depY purified from hybridoma cells. The isotype was determined by searching the cDNA sequence against the UniProt database.

Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS)

Data acquisition was performed with a Triple-TOF 6600 mass spectrometer (ABI Sciex, Framingham, MA) fitted with a Nanospray III source (AB SCIEX, Framingham, MA) and a Pico Tip emitter (# FS360-20-10-N-5-C12, New Objectives, Woburn, MA). The ion spray voltage was 2700 V, declustering potential 60 V, curtain gas 30 psi, nebulizer gas 10 psi, and interface heater temperature 150°C.

Peptides were introduced into the mass spectrometer using ultra high pressure liquid chromatography. A splitless Ultra 1D Plus ultrahigh pressure chromatography system (Eksigent, Dublin, CA) was coupled to the Triple-TOF via a cHiPLC Nanoflex microchip column system (Eksigent, Dublin, CA). The Nanoflex system uses a replaceable microfluidic trap column and a replaceable separation column. Both are packed with ChromXP C18 (3 μm, 120 A particles; Trap: 200 μm × 0.5 mm; Separation: 75 μm × 15 cm). Chromatography solvents were water/acetonitrile/formic acid (A: 100/0/0.1%, B: 0/100/0.1%). Picomole amounts of sample, in a 5 μl volume, were loaded. Trapping and desalting were carried out at 2 μL/min for 15 minutes with 100% mobile phase A. Separation was obtained with a linear gradient 5%A/95%B to 70%A/30% B over 60 min at a flow rate of 0.3 μL/min.

Statistics

Biacore and Octet data were fit to a 1:1 binding model. The accuracy of the reported Kd values was determined from Chi2 values. Chi2 is a measure of the average deviation of the experimental data from the fitted curve. Values less than 1 indicate an excellent fit. R2 is an estimate of the goodness of the fit. Values close to 1 indicate excellent fit.

Results

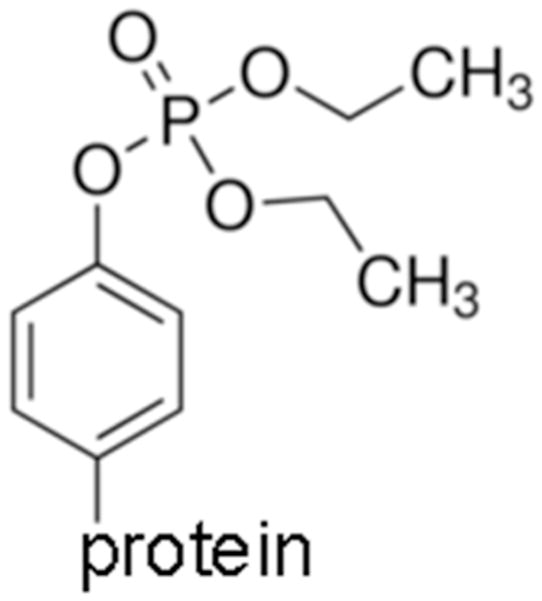

Antigen structure

OP adducts on the active site serine of AChE and BChE dealkylate in a process called aging. In contrast, diethoxyphospho adducts on tyrosine do not age.10–13, 15, 16 MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometry analysis of OP-peptides confirmed that all carried the diethoxyphosphate group on tyrosine shown in Figure 1 and none had aged to monoethoxyphosphate. However, we found that the dimethoxyphospho-tyrosine adduct on peptide GGYR, produced by reaction with dichlorvos, spontaneously aged to the monomethoxyphospho-tyrosine adduct, confirming a result previously reported by Bui-Nguyen et al. (2014).8

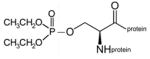

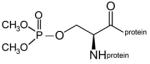

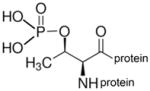

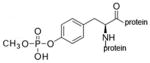

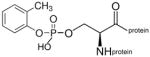

Figure 1.

Structure of diethoxyphospho-tyrosine, the antigen for antibody production. In this manuscript the abbreviation OP is used specifically for the diethoxyphospho adduct.

Monoclonal antibody depY recognizes diethoxyphospho-tyrosine independent of the amino acid context of the modified tyrosine

The initial ELISA screen of 30 hybridoma culture media yielded 4 samples that gave a good signal with human albumin-OP and mouse albumin-OP and no signal for control human and mouse albumin. A good signal was defined as absorbance at 405 nm in the range 0.2 to 0.4 after 20 min reaction with the HRP substrate. No signal was defined as background absorbance of 0.07 to 0.09 under the same conditions. After monoclonal antibodies from the 4 hybridoma culture media were purified and tested against a variety of diethoxyphospho-tyrosine proteins, one outperformed the others in terms of signal intensity in ELISA. DepY was selected for further characterization.

ELISA and Western blot results summarized in Table 1 show that monoclonal antibody depY recognized peptides and proteins containing diethoxyphospho-tyrosine regardless of the amino acid context of the OP-tyrosine. Two types of OP-labeled samples were tested in Table 1. One type was prepared by conjugating specific OP-tyrosine peptides to a carrier protein, for example, peptide QYDVRK-OP diethoxyphosphorylated on tyrosine was conjugated to human albumin. The second type of OP-modified sample was prepared by incubating proteins with chlorpyrifos oxon. Amino acid sequences around the OP-tyrosine and the percent modification in casein-OP, tubulin-OP, human albumin-OP, lysozyme-OP, and aprotinin-OP are provided in Appendix S1 in the Supporting Information section. Table 1 shows a range of %OP-Tyr in OP-proteins because some tyrosines were labeled extensively, whereas other tyrosines in the same protein were minimally labeled. For example, 13 tyrosines were diethoxyphosphorylated in the porcine tubulin alpha-1A chain, with the extent of modification ranging from 7% for Tyr357 to 69% for Y103 (see Appendix S1). Similarly, 13 tyrosines were diethoxyphosphorylated in the porcine tubulin alpha-1B chain, with the extent of modification ranging from 6% for Tyr83 to 67% for Tyr 103.

Table 1.

DepY recognizes diethoxyphospho-tyrosine independent of the amino acid sequence around the modified tyrosine*

| Antigen | ELISA | Western blot | # OP-Tyr/protein | %OP-Tyr |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hu albumin-QYDVRK-OP | +++ | ++++ | 7 | |

| Hu albumin control | − | − | 0 | |

| Hu albumin-YGGFL-OP | +++ | ++++ | 5 | |

| Bovine albumin-LYGLPR-OP | +++ | ++++ | 16 | |

| Bovine albumin control | − | − | 0 | |

| Lysozyme-GGYR-OP | ++++ | NA | 4, 10 & 16 | |

| Lysozyme-RARYEM-OP | ++++ | NA | 6 & 9 | |

| Lysozyme-PYYMRR-OP | +++ | ++ | 1 | |

| Lysozyme control | − | − | 0 | |

| Ovalbumin-RSLYAS-OP | +++ | NA | 18 & 22 | |

| Ovalbumin-YPF-OP | ++++ | NA | 6 & 14 | |

| Ovalbumin-YGGFL-OP | ++++ | NA | 5, 9 & 12 | |

| Ovalbumin control | − | NA | 0 | |

| Casein-OP (OP on Tyr) | +++ | +++ | 10–95% | |

| Casein control | − | − | 0 | |

| Bovine tubulin-OP (OP on Tyr + Lys) | +++ | +++++ | 12–26% | |

| Bovine tubulin control | − | − | 0 | |

| Porcine tubulin-OP (OP on Tyr + Lys) | +++ | +++++ | 6–69% | |

| Porcine tubulin control | − | − | 0 | |

| Human albumin-OP (OP on Tyr + Lys) | + | − | 21–98% | |

| Lysozyme-OP (OP on Tyr + Lys) | +++ | − | 3–5% | |

| Aprotinin-OP (OP on Tyr + Lys) | ++ | + | 10% | |

| Aprotinin control | − | − | 0 | |

| Mouse albumin-OP (OP on Tyr + Lys) | +++ | NA | 83% | |

| Mouse albumin control | − | NA | 0 |

OP refers to the diethoxyphospho adduct on tyrosine. The OP adduct is exclusively on tyrosine in the peptides and in casein. The OP adduct is on both tyrosine and lysine in human albumin, bovine tubulin, porcine tubulin, lysozyme, and aprotinin. However, monoclonal antibody depY does not recognize OP-Lys adducts. The (+) symbol represents signal intensity, where (+++++) represents the highest and (+) the lowest positive signal. The symbol (−) represents a negative result. NA is the symbol for data not available. # OP-Tyr/protein is the number of diethoxyphospho-Tyr peptides crosslinked per protein molecule as determined by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. %OP-Tyr refers to the percent OP labeling of multiple tyrosines in the protein where the identity of each OP-modified tyrosine and the extent of labeling was determined by LC-MS/MS; the location of the OPlabeled tyrosines and the % modified in each protein is described in Supporting Information Appendix S1.

Table 1 shows a rough correlation between the number of OP-Tyr peptides crosslinked per protein molecule and signal intensity in ELISA. For example lysozyme-PYYMRR-OP with only 1 OP-peptide bound per lysozyme molecule had a weaker signal in ELISA than lysozyme-GGYR-OP with 4, 10 and 16 OP-peptides bound. A similar rough correlation was observed for OP-proteins. For example, aprotinin-OP was modified on only one of its 4 tyrosine residues and only 10% of Tyr56 was diethoxyphosphoryalted. In contrast, porcine tubulin was modified on 13 out of 19 tyrosine residues in the alpha chains and on 8 and 11 out of 16 tyrosines in the beta chains. The level of modification ranged from 6 to 69%. Signal intensity for tubulin-OP was exceptionally high in Western blots, whereas signal intensity for aprotinin-OP was low.

It was concluded that depY recognized diethoxyphospho-tyrosine independent of the amino acid sequence around OP-tyrosine. This feature makes it possible to use the depY antibody in any species to search for unknown proteins diethoxyphosphorylated on tyrosine.

DepY does not recognize OP-lysine

Appendix S1 shows that proteins treated with chlorpyrifos oxon were modified on tyrosine and lysine. The exception was casein, which was modified exclusively on tyrosine. To determine whether depY recognized diethoxyphospho-lysine, we prepared diethoxyphospho-lysine and conjugated it to human albumin. The conjugated albumin bound 14 OP-lysine per albumin molecule. An immulon plate coated with 1 μg of OP-lysine-albumin per well, or with the positive control OP-tubulin was probed with 0.2 μg/100 μL of depY. We used a 10-fold higher antibody concentration than in our standard assays to overcome potential poor binding affinity. ELISA detected no binding of depY to OP-lysine-albumin, but strong binding to the positive control, OP-tubulin. It was concluded that depY does not recognize diethoxyphosphorylated-lysine.

DepY does not recognize phospho-tyrosine

Hundreds of proteins in a cell are phosphorylated on tyrosine at various times during the life a cell.14 The possibility that depY recognizes phospho-tyrosine was ruled out in a competition ELISA experiment. The competition ELISA was set up so that the antibody would be unavailable to bind OP-protein coated on the 96-well plate if O-phospho-tyrosine binds to the antibody in solution. DepY diluted to 0.1 μg/mL in 1% BSA/TBS was incubated with 10−3 to 10−13 M phospho-tyrosine for 1 h at room temperature. The antibody sites available for binding to human albumin-YGGFL-OP in a 96-well plate were evaluated by standard ELISA methods. It was found that binding of depY to human albumin YGGFL-OP was unaffected by the presence of phospho-Tyr. In conclusion, depY does not recognize phospho-Tyrosine.

Anti-phospho-L-tyrosine monoclonal antibody does not recognize diethoxyphospho-tyrosine

To determine whether anti-phospho-tyrosine monoclonal antibody PY20 recognized diethoxyphospho-tyrosine, we conjugated O-phospho-L-tyrosine to human albumin to serve as a positive control. Test samples in Figure 2 included lysozyme-PYMRR-OP, BSA-LYGLPR-OP, human albumin-QYDVRK-OP, human albumin-YGGFL-OP, control human albumin, porcine tubulin-OP, control porcine tubulin, and the positive control, O-phospho-L-tyrosine crosslinked to human albumin. The Western blot in Figure 2 shows that none of the diethoxyphospho-tyrosine samples (lanes 1–7) hybridized with PY20, but the positive control sample in lanes 8 and 9 gave a strong signal. Monomers, dimers, and multimers of the positive control sample in lanes 8 and 9 were formed during the crosslinking reaction with EDC. It was concluded that monoclonal antibody PY20 does not recognize diethoxyphospho-tyrosine-proteins, but does recognize the positive control O-phospho-L-tyrosine crosslinked to human albumin.

DepY does not recognize dichlorvos-modified tyrosine

DepY immobilized on Sepharose beads was incubated with dichlorvos-modified GGYR and chlorpyrifos oxon modified YGGFL to determine whether the antibody captured both types of modified tyrosine. Dichlorvos treatment produced the dimethoxyphospho adduct on tyrosine, a portion of which aged to the monomethoxyadduct. Chlorpyrifos oxon treatment produced the diethoxyphospho adduct on tyrosine, but no monoethoxyphospho adduct (no aged adduct). After beads were washed with PBS and water, the captured peptides were released with 50% acetonitrile, 1% TFA and identified by their masses in the 4800 Triple TOF mass spectrometer. Panel A in Figure 3 shows masses at 546.2 (monomethoxyphospho adduct) and 560.2 Da (dimethoxyphospho adduct) for the dichlorvos-modified peptide GGYR and masses at 692.2 (diethoxyphospho adduct) and 714.2 Da (diethoxyphospho adduct plus a sodium ion) for the CPO-modified peptide YGGFL before the peptides were treated with immobilized antibody. Panel B shows the peptides that were captured by the immobilized antibody; there are no masses for dichlorvosmodified GGYR at 546.2 and 560.2 Da, but there are strong signals for diethoxyphospho-YGGFL (chlorpyrifos oxon-modified) at 692.2 and its sodium ion at 714.2 Da. It was concluded that depY recognizes chlorpyrifos oxon modified-tyrosine, but not dichlorvos-modified tyrosine.

Figure 3.

Immuno MALDI demonstrating specific capture of diethoxyphospho-tyrosine modified peptide by antibody depY. A) Peptides before incubation with immobilized antibody. Dichlorvos-modified peptide GGYR has masses at 560.2 Da for the dimethoxyphospho adduct and 546.2 Da for the aged monomethoxyphospho adduct. Chlorpyrifos oxon modified peptide YGGFL has masses at 692.2 Da for the diethoxyphospho adduct on YGGFL and 714.2 Da for the sodiated ion. B) Peptides captured by the antibody were identified as the diethoxyphospho adduct on YGGFL. No ions for the dichlorvos-modified peptide were observed. C) Negative control beads (no antibody) captured no diethoxyphospho-Tyr modified peptides.

Specificity of monoclonal antibody depY for diethoxyphospho-tyrosine

Our goal was to determine whether monoclonal antibody depY recognized adducts in addition to diethoxyphospho-tyrosine. Naturally-occurring phospho-serine and phospho-threonine are present in casein. Phosphosite.org shows a total of 34 phospho-Ser and phospho-Thr sites in the casein isozymes. Control, untreated casein was not detected in ELISA or in Western blots, indicating that depY does not recognize phospho-serine or phospho-threonine.

A mixture of phospho-serine and cresylphospho-serine modified sites was created by inhibiting human butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) with cresyl saligenin phosphate, the toxic metabolite of tri-o-cresylphosphate.17, 18 This reagent makes a covalent bond with the active site serine 198 of human BChE to yield the phospho- and cresylphospho-serine modifications. A dimethoxyphospho adduct on the active site serine of BChE was prepared by inhibiting BChE with dichlorvos, and a diethoxyphospho adduct by inhibiting BChE with CPO. The inhibited BChE samples were boiled to unfold the protein and thus make available the active site serine residue, which in the native protein is buried deep inside the active site gorge.19 The boiled samples were coated on an immulon plate where binding of depY was evaluated by standard ELISA methods. The result showed that depY does not bind phospho-serine and cresylphospho-serine (BChE inhibited by cresyl saliginen phosphate, diethoxyphospho-serine (BChE inhibited by CPO), and dimethoxyphosphoserine (BChE inhibited by dichlorvos). It was concluded that depY does not recognize phospho-serine, phospho-threonine, diethoxyphospho-serine, dimethoxyphospho-serine, and cresylphospho-serine. Table 2 summarizes the hapten structures that were tested and found to be unreactive with depY.

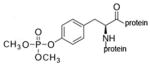

Table 2.

Haptens not recognized by monoclonal antibody depY.

|

diethoxyphospho-lysine protein |

O-phospho-L-tyrosine |

diethoxyphospho-serine protein |

phospho-tyrosine protein |

dimethoxyphospho-tyrosine protein |

phospho-serine protein |

dimethoxyphospho-serine protein |

phospho-threonine protein |

monomethoxyphospho-tyrosine protein |

o-cresylphospho-serine protein |

Limit of detection

The Western blot in Figure 4 shows that depY detects as little as 25 ng of human albumin conjugated to OP-YGGFL. The albumin conjugate has 5 bands on the Western blot because the crosslinking agent EDC crosslinked albumin to itself to form albumin dimers, trimers, tetramers, and pentamers.

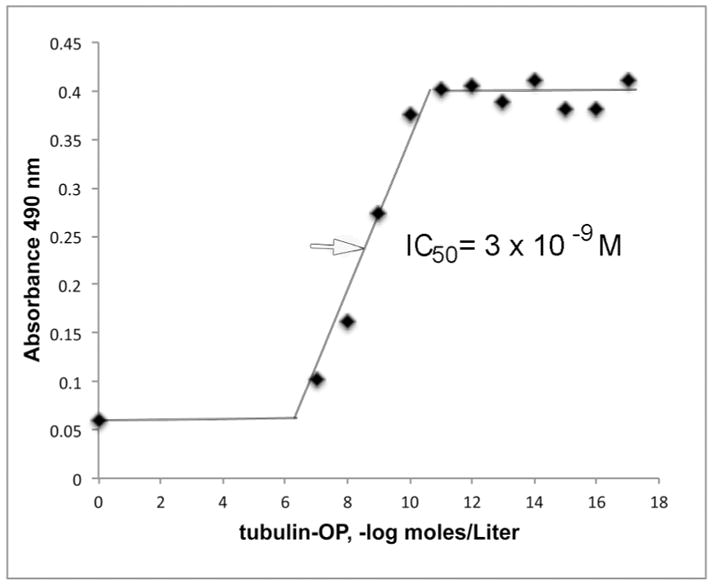

Competition ELISA to measure IC50

Binding of depY to human albumin-QYDVRK-OP coated on a 96-well immulon plate was observed in Figure 5 after the antibody was incubated with 10−17 M to 10−7 M concentrations of porcine tubulin-OP. It was found that 50% of the sites in 0.1 μg/mL depY were occupied by 3 × 10−9 M porcine tubulin-OP.

Figure 5.

Binding affinity of depY for porcine tubulin-OP. The IC50 is 3 × 10−9 M.

Binding affinity of OP-peptides measured by Biacore analysis

Binding to depY of small peptides modified on tyrosine by diethoxyphosphate was measured on a Biacore instrument. Table 3 shows Kd values ranging from 10−7 to 10−8 M. The unlabeled control peptides did not bind to depY in 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, 0.05% polyoxyethylenesorbitan.

Table 3.

Binding affinity measured on Biacore T-200 of monoclonal antibody depY for peptides modified on tyrosine by diethoxyphosphate

| Peptide | Kd, M | Chi2 |

|---|---|---|

| YPF-OP | 4.1 × 10−7 | 0.0076 |

| YPF control | No binding | - |

| GGYR-OP | 5.3 × 10−8 | 0.506 |

| GGYR control | No binding | - |

| LYGLPR-OP | 1.2 × 10−8 | 0.0263 |

| LYGLPR control | No binding | - |

| PPYRM-OP | 3.6 × 10−7 | 0.361 |

| PPYRM control | No binding | - |

Chi2 values below 1 are highly significant. The dash indicates Chi2 values too low to be measureable.

Binding affinity of OP-proteins measured by Bio-layer interferometry

Rate constants for association (kon) and dissociation (koff) were measured in an OctetRED96 instrument. Figure 6 shows the data for porcine tubulin-OP in panel A and for the control porcine tubulin in panel B. Table 4 shows that Kd values (koff divided by kon) were less than 1 × 10−12 M for porcine tubulin-OP, casein-OP, ovalbumin crosslinked to YPF-OP, and bovine albumin crosslinked to LYGLPR-OP. It was concluded that proteins labeled on tyrosine by diethoxyphosphate are tightly bound to monoclonal antibody depY despite the presence of 0.15 M sodium chloride in the assay buffer.

Figure 6.

Binding affinity of depY monoclonal antibody determined by biolayer interferometry using an OctetRED96 instrument. A) Binding and dissociation of porcine tubulin-OP modified on tyrosine by diethoxyphosphate. B) No binding to control porcine tubulin. The depY monoclonal antibody was captured on an anti-mouse IgG biosensor. A concentration series of 100, 50, 25, 12.5 and 6.25 nM porcine tubulin-OP was used to determine the association and dissociation rate constants and the binding affinity for depY. The data points are represented by wavy lines and the fitted data are shown as solid lines.

Table 4.

Binding affinity and rate constants measured on OctetRED96 of monoclonal antibody depY for proteins modified on tyrosine by diethoxyphosphate.

| Protein | kon (1/Ms) | koff (1/s) | Kd (M) | Chi2 | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porcine tubulin-OP | 2.44 E+05 | <1.0 E-7 | <1.0 E-12 | 0.014 | 0.99 |

| Porcine tubulin control | NA | NA | No binding | NA | NA |

| Casein-OP | 1.82 E+05 | <1.0 E-7 | <1.0 E-12 | 0.004 | 0.97 |

| Casein control | NA | NA | No binding | NA | NA |

| Ovalbumin-YPF-OP | 1.40 E+05 | <1.0 E-7 | <1.0 E-12 | 0.027 | 0.96 |

| Ovalbumin-YPF control | NA | NA | No binding | NA | NA |

| Bovine albumin-LYGLPR-OP | 2.08 E+05 | <1.0 E-7 | <1.0 E-12 | 0.176 | 0.93 |

| Bovine albumin-LYGLPR control | NA | NA | No binding | NA | NA |

Chi2 values less than 1 are highly significant. NA, not applicable.

Sequence and Isotype IgG2a kappa of depY

The recombinant depY with the sequence shown in Figure 7 had the same binding specificity as depY purified from hybridoma cells when tested by ELISA against a panel of 12 OP-tyrosine proteins. The unlabeled control proteins bound neither the recombinant nor the hybridoma depY. This result confirmed that the sequences in Figure 7 represent depY. The isotype of depY is IgG2a kappa. The nucleotide and translated amino acid sequences, have been deposited in GenBank.

Figure 7.

Amino acid sequences of the variable heavy and light chains of depY. The complementarity determining regions (CDR) were defined by IMGT/V-QUEST, http://www.imgt.org. GenBank accession numbers are MG182361 and MG182362.

Discussion

Rationale for choosing diethoxyphospho-tyrosine as target

This is the first report of a monoclonal antibody to the diethoxyphospho-tyrosine adduct on proteins independent of the amino acids around the modified tyrosine. The depY monoclonal antibody is expected to recognize adducts on any protein from any animal.

We and others have demonstrated that humans poisoned with organophosphorus pesticides have adducts on tyrosine 411 of serum albumin.2, 9, 11 We hypothesize that not only albumin but also other proteins are modified on tyrosine, but that these additional proteins occur in low abundance and need to be enriched before they can be identified. An antibody to OP-tyrosine would aid in identification of these hypothetical adducts. The hypothetical adducts could be proteins that are naturally phosphorylated and dephosphorylated during cell growth and differentiation20–22, but whose function is disrupted when they are irreversibly modified by OP.

Another good candidate for production of a monoclonal antibody would be Lysine- OP because lysines were modified in almost all the proteins we treated with CPO. V-type nerve agents have been demonstrated to phosphonylate 6 lysine residues in ubiquitin23 that are essential for the biological function of ubiquitin. Acetylated and methylated lysines are reversible posttranslational modifications that play key roles in regulating gene expression.24, 25 These functions could be impaired when lysine is irreversibly modified by OP. An antibody to OP-lysine together with antibodies to OP-tyrosine and OP-serine7 would be useful in future studies aimed at understanding chronic illness from OP exposure.

Limitation of monoclonal antibody depY

Tubulin and other proteins that are diethoxyphosphorylated on several residues are bound with high affinity (Kd 10−12 M) by monoclonal antibody depY, but peptides modified on a single tyrosine are bound with lower affinity (Kd 10−8 M). It may be possible to generate a higher affinity antibody in rabbit or by single B cell cloning.26, 27

Antibodies to organophosphorus adducts in the literature

Exposure to organophosphorus pesticides is accompanied by irreversible modification of the active site serine of AChE and BChE accompanied by loss of enzyme activity and toxicity. Common insecticide oxons such as chlorpyrifos oxon and paraoxon add a diethoxyphosphate group to serine. Over the years, several laboratories have tried to make antibodies that distinguish modified from unmodified AChE. The major difficulty in making such an antibody has been the fact that O-phosphylated-serine is unstable in vivo.7, 28 Animals produced no antibody because the phosphylated-serine was converted to dehydroalanine with loss of the ligand. This problem was solved by the group of Charles Thompson at the University of Montana by substituting a CH2 group for the side-chain OH in serine.7 The substitution prevented the phosphylated serine homolog from undergoing a beta-elimination reaction with loss of the OP ligand. They succeeded in producing monoclonal antibodies that recognize diethoxyphosphorylated-serine and monoethoxyphosphorylated-serine. Furthermore, they made their monoclonal antibodies available through neuromab.ucdavis.edu.

Monoclonal antibodies have been generated that recognize the pinacolyl methyl phosphonate (soman) and the VX adducts on tyrosine 411 of albumin.29 The monoclonals were made to a nerve-agent modified, 10-residue peptide of human albumin and are specific for adducts on albumin. Binding affinity evaluated by competition ELISA was in the nanomolar range.

Several laboratories have made monoclonals to a soman hapten for the purpose of neutralizing soman before it reacted with AChE.30–32 The monoclonals had limited success because they lacked sufficient affinity to reduce the in vivo concentration of soman to non-toxic levels.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

Supported by DLS/NCEH/CDC contract 200-2015-87939 (to OL) and Fred & Pamela Buffett Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA036727. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Public Health Preparedness and Response, and Defense Threat Reduction Agency 11-005-12430 (to TAB and RCJ).

Mass spectrometry data were obtained with the support of the Mass Spectrometry and Proteomics Core Facility at the University of Nebraska Medical Center. Amino acid quantities were obtained with the support of the Protein Structure Core Facility at the University of Nebraska Medical Center.

Abbreviations

- AChE

acetylcholinesterase

- BChE

butyrylcholinesterase

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- CPO

chlorpyrifos oxon

- DepY

mouse monoclonal antibody to diethoxyphospho-tyrosine

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide.HCl

- ELISA

enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- HRP

horse radish peroxidase

- HSA

human serum albumin

- IC50

The half maximal inhibitory concentration

- Kd

equilibrium dissociation constant (koff/kon)

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- MALDI-TOF

matrix assisted laser desorption ionization- time of flight mass spectrometry

- MES

2-[N-morpholino]ethanesulfonic acid

- OP

diethoxyphospho adduct produced by reaction with chlorpyrifos oxon or paraoxon

- OVA

ovalbumin

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- Sulfo-NHS

N-hydroxysulfosuccinimide

- TBS

Tris buffered saline 20 mM TrisCl, 0.15 M NaCl pH 7.4

- TBST

Tris buffered saline with 0.05% (v/v) Tween-20

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- TMB

3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Use of trade names is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Public Health Service, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Description of Supporting Information material. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org

Reagents for characterizing monoclonal antibody depY.

Table S1. Proteins diethoxyphosphorylated by chlorpyrifos oxon.

Figure S1. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to quantify number of OP-peptides cross-linked to carrier proteins.

Table S2. Diethoxyphospho-tyrosine peptides conjugated to carrier proteins used for immunization, boosting, screening, ELISA and Western blots.

Table S3. Diethoxyphospho-tyrosine peptides (no protein)

Table S4. Additional reagents for characterizing the specificity of depY

Appendix S1. Identification and quantitation of residues modified by reaction of proteins with chlorpyrifos oxon, analyzed by LC-MS/MS.

References

- 1.Pope C, Karanth S, Liu J. Pharmacology and toxicology of cholinesterase inhibitors: uses and misuses of a common mechanism of action. Environmental toxicology and pharmacology. 2005;19:433–446. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2004.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Schans MJ, Hulst AG, van der Riet-van Oeveren D, Noort D, Benschop HP, Dishovsky C. New tools in diagnosis and biomonitoring of intoxications with organophosphorothioates: Case studies with chlorpyrifos and diazinon. Chem Biol Interact. 2013;203:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.VanDine R, Babu UM, Condon P, Mendez A, Sambursky R. A 10-minute point-of-care assay for detection of blood protein adducts resulting from low level exposure to organophosphate nerve agents. Chem Biol Interact. 2013;203:108–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards PG, Johnson MK, Ray DE. Identification of acylpeptide hydrolase as a sensitive site for reaction with organophosphorus compounds and a potential target for cognitive enhancing drugs. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:577–583. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.3.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sindi RA, Harris W, Arnott G, Flaskos J, Lloyd Mills C, Hargreaves AJ. Chlorpyrifos- and chlorpyrifos oxon-induced neurite retraction in pre-differentiated N2a cells is associated with transient hyperphosphorylation of neurofilament heavy chain and ERK 1/2. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2016;308:20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glenney JR, Jr, Zokas L, Kamps MP. Monoclonal antibodies to phosphotyrosine. J Immunol Methods. 1988;109:277–285. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(88)90253-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belabassi Y, Chao CK, Holly R, George KM, Nagy JO, Thompson CM. Preparation and characterization of diethoxy- and monoethoxy phosphylated (‘aged’) serine haptens and use in the production of monoclonal antibodies. Chem Biol Interact. 2014;223C:134–140. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bui-Nguyen TM, Dennis WE, Jackson DA, Stallings JD, Lewis JA. Detection of dichlorvos adducts in a hepatocyte cell line. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:3583–3595. doi: 10.1021/pr5000076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li B, Ricordel I, Schopfer LM, Baud F, Megarbane B, Nachon F, Masson P, Lockridge O. Detection of adduct on tyrosine 411 of albumin in humans poisoned by dichlorvos. Toxicol Sci. 2010;116:23–31. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfq117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grigoryan H, Schopfer LM, Peeples ES, Duysen EG, Grigoryan M, Thompson CM, Lockridge O. Mass spectrometry identifies multiple organophosphorylated sites on tubulin. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;240:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.07.020. NIHMS:135197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li B, Eyer P, Eddleston M, Jiang W, Schopfer LM, Lockridge O. Protein tyrosine adduct in humans self-poisoned by chlorpyrifos. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;269:215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grigoryan H, Schopfer LM, Thompson CM, Terry AV, Masson P, Lockridge O. Mass spectrometry identifies covalent binding of soman, sarin, chlorpyrifos oxon, diisopropyl fluorophosphate, and FP-biotin to tyrosines on tubulin: a potential mechanism of long term toxicity by organophosphorus agents. Chem Biol Interact. 2008;175:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li B, Schopfer LM, Grigoryan H, Thompson CM, Hinrichs SH, Masson P, Lockridge O. Tyrosines of human and mouse transferrin covalently labeled by organophosphorus agents: a new motif for binding to proteins that have no active site serine. Toxicol Sci. 2009;107:144–155. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bian Y, Li L, Dong M, Liu X, Kaneko T, Cheng K, Liu H, Voss C, Cao X, Wang Y, Litchfield D, Ye M, Li SS, Zou H. Ultra-deep tyrosine phosphoproteomics enabled by a phosphotyrosine superbinder. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:959–966. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding SJ, Carr J, Carlson JE, Tong L, Xue W, Li Y, Schopfer LM, Li B, Nachon F, Asojo O, Thompson CM, Hinrichs SH, Masson P, Lockridge O. Five tyrosines and two serines in human albumin are labeled by the organophosphorus agent FP-biotin. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:1787–1794. doi: 10.1021/tx800144z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li B, Schopfer LM, Hinrichs SH, Masson P, Lockridge O. Matrixassisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry assay for organophosphorus toxicants bound to human albumin at Tyr411. Anal Biochem. 2007;361:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2006.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schopfer LM, Furlong CE, Lockridge O. Development of diagnostics in the search for an explanation of aerotoxic syndrome. Anal Biochem. 2010;404:64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carletti E, Schopfer LM, Colletier JP, Froment MT, Nachon F, Weik M, Lockridge O, Masson P. Reaction of Cresyl Saligenin Phosphate, the Organophosphorus Agent Implicated in Aerotoxic Syndrome, with Human Cholinesterases: Mechanistic Studies Employing Kinetics, Mass Spectrometry, and X-ray Structure Analysis. Chem Res Toxicol. 2011;24:797–808. doi: 10.1021/tx100447k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicolet Y, Lockridge O, Masson P, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Nachon F. Crystal structure of human butyrylcholinesterase and of its complexes with substrate and products. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41141–41147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ha JR, Siegel PM, Ursini-Siegel J. The Tyrosine Kinome Dictates Breast Cancer Heterogeneity and Therapeutic Responsiveness. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117:1971–1990. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunter T. Tyrosine phosphorylation: thirty years and counting. Current opinion in cell biology. 2009;21:140–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alonso A, Sasin J, Bottini N, Friedberg I, Friedberg I, Osterman A, Godzik A, Hunter T, Dixon J, Mustelin T. Protein tyrosine phosphatases in the human genome. Cell. 2004;117:699–711. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt C, Breyer F, Blum MM, Thiermann H, Worek F, John H. V-type nerve agents phosphonylate ubiquitin at biologically relevant lysine residues and induce intramolecular cyclization by an isopeptide bond. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-7706-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choudhary C, Kumar C, Gnad F, Nielsen ML, Rehman M, Walther TC, Olsen JV, Mann M. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and coregulates major cellular functions. Science. 2009;325:834–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Nuland R, Gozani O. Histone H4 Lysine 20 (H4K20) Methylation, Expanding the Signaling Potential of the Proteome One Methyl Moiety at a Time. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2016;15:755–764. doi: 10.1074/mcp.R115.054742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kurosawa N, Wakata Y, Inobe T, Kitamura H, Yoshioka M, Matsuzawa S, Kishi Y, Isobe M. Novel method for the high-throughput production of phosphorylation site-specific monoclonal antibodies. Scientific reports. 2016;6:25174. doi: 10.1038/srep25174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carbonetti S, Oliver BG, Vigdorovich V, Dambrauskas N, Sack B, Bergl E, Kappe SHI, Sather DN. A method for the isolation and characterization of functional murine monoclonal antibodies by single B cell cloning. J Immunol Methods. 2017;448:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacDonald M, Lanier M, Cashman J. Solid-phase synthesis of phosphonylated peptides. SYNLETT. 2010;13:1951–1954. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen S, Zhang J, Lumley L, Cashman JR. Immunodetection of serum albumin adducts as biomarkers for organophosphorus exposure. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;344:531–541. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.201368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jia P, Wang Y, Yu M, Wu J, Yang R, Zhao Y, Zhou L. An organophosphorus hapten used in the preparation of monoclonal antibody and as an active immunization vaccine in the detoxication of soman poisoning. Toxicol Lett. 2009;187:45–51. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson JK, Cerasoli DM, Lenz DE. Role of immunogen design in induction of soman-specific monoclonal antibodies. Immunol Lett. 2005;96:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hunter KW, Jr, Lenz DE, Brimfield AA, Naylor JA. Quantification of the organophosphorus nerve agent soman by competitive inhibition enzyme immunoassay using monoclonal antibody. FEBS Lett. 1982;149:147–151. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)81091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.