Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study was to assess the oral health knowledge, behavior, and practices related to use of miswak (chewing stick) in population of Aseer Region, Saudi Arabia.

Subjects and Methods:

Of the 2023 participants, 1666 (83.3%) were females and 334 (16.7%) were males. The questionnaires having 10 online questions were used to assess the knowledge of oral hygiene methods, including frequency, reason, and methods for miswak use.

Statistical Analysis Used:

The survey data were collected and organized into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft Inc., USA) and were statistically analyzed utilizing the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.0 software (IBM Inc., USA). The statistical test used here was the Chi-square test, and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Results:

Participants responded regarding the primary oral hygiene methods; 46.5% respondents used toothbrushes, 44.5% used both toothbrushing and miswak, and 8% used only miswak as their primary tooth cleaning method. 28.2% respondents cleaned their teeth with tooth brush or miswak at least once a day, 37.6% twice, 28.4% whenever required, and 5.9% infrequently. Majority of the participants, i.e. 70.2% were using miswak with taper and as a brush to clean all tooth surfaces. About 84.7% feel fresh, and teeth are whiter after the use of miswak. Nearly, 84.7% prefer to continue using miswak in combination with other teeth cleaning methods, which may have more benefits.

Conclusions:

In our study, most common type of oral hygiene method employed is toothbrush and in combination with miswak. Chewing stick use was common among participants with religious advice being the dominant reason for usage.

Keywords: Knowledge, miswak, oral health, Saudi Arabia, toothbrush

Introduction

Oral health is an integral part of an individual's general health and over all well-being.[1] Good oral health not only enables a person to look and feel good; it is equally important in maintaining oral functions.[2] Oral hygiene is one of the most important daily routine practices and keeps the mouth and teeth clean and prevents many health problems.[3] Different oral hygiene methods have been used to overcome widely endemic diseases such as dental caries and oral infections. Due to increasing awareness and expected evolving population, the use of safe, effective, and economical products have expanded drastically. Modern dental care tools are designed to provide both a mechanical and chemical means of removing plaque and food residues from the surface and spaces between the teeth. Mechanical cleaning using the toothbrush plays the most vital role. The advancement of the modern tooth brushes can be traced back to chewing sticks used by the Babylonians (the Greek and Romans) 7000 years ago.[4] The use of miswak becomes very popular in the Muslim world including several African and Arab countries. The use of miswak in Muslim countries is treated as compulsory act for religious part.[5] It has been used by Muslims for more than 1000 years since the prophet Muhammad (S.A.W) realized its value as an oral hygiene device.[6]

The most common type of chewing stick, miswak, is derived from Salvadora persica, a small tree or shrub with a spongy stem and root, which is easy to crush between the teeth. Pieces of the root usually swell and become soft when soaked in water.[7] Miswak is a chewing stick used in many developing countries as a traditional toothbrush for oral hygiene.[8] In 1987, World Health Organization encouraged the developing nations to use miswak for oral hygiene because of tradition, availability, and low cost.[9] Recently, various authors have concluded that chewing sticks or its extract has therapeutic effect on gingival diseases.[10] As a consequence, users of oral hygiene products prefer natural components and a minimum of chemical additives in their toothpaste.[11] Therefore, natural supplements in oral healthcare products have become popular in the last decades, particularly in the Western industrial world and in Asian countries.[12]

Subjects and Methods

The study design was cross-sectional study involving 2023 participants from Saudi Arabia. The sample constitutes 1666 (83.3%) females and 334 (16.7%) males of age group between 20 and 65 years. This study was conducted between February and September 2016. The questionnaires elicited information on sociodemographic characteristics and 10 online questions assessing and a number of variables related to knowledge of oral hygiene methods, including frequency, reason, and methods for miswak use. The study was approved by the ethical approval committee at College of Dentistry King Khalid University, Abha. A written informed consent was obtained from all the study participants. All individuals were requested to complete a comprehensive questionnaire in Arabic (local Language). Each respondent was made aware about the aims of the study and provided instructions on how to fill the questionnaire.

Validity of questionnaire

To make sure about face validity and content validity of the questionnaire, it was submitted to experts’ review. The questions were finally approved by the experts (10 questions), and eventually, the opinions of the experts were asked on face validity. A pilot study was conducted among 100 individuals. In the pilot study, the individuals were asked for feedback on clarity of the questions and whether there was difficulty in answering the question. The individuals who participated in the pilot study were not included in the final sample, and no modification was required in the questionnaire.

Sample population

For this cross-sectional study, z value at confidence level of 95% (z) was 1.96, with prevalence of knowledge about miswak is 0.3 (p) and error (ε) of 2% was used to calculate the sample size. Calculated sample size required was 2016.

n – sample size.

z – z score.

p̂ – population proportion (probability).

ε – margin of error.

The survey data were collected and organized into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft Inc., USA), and were statistically analyzed utilizing the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.0 software (SPSS 20, IBM, Armonk, NY, United States of America). The statistical test used here was the Chi-square test, and P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Results

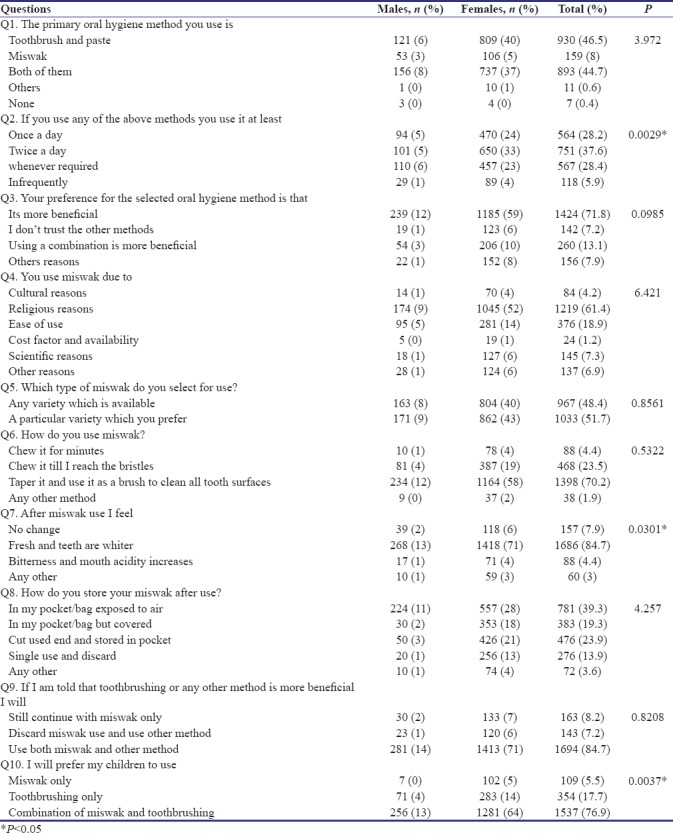

Total participants included in the study were 2023; 334 were males and 1666 were females of age group between 20 and 65 years. The results regarding percentage distribution between gender and number of study participants in terms of knowledge and attitude toward oral hygiene methods were summarized [Table 1]. When participants were asked regarding the primary oral hygiene methods, 46.5% respondents used toothbrushes, 44.5% used both toothbrushing and miswak, and 8% used only miswak as their primary tooth cleaning method. Number of times daily using oral hygiene method either toothbrushing or miswak were 28.2% once daily, 37.6% twice daily, 28.4% whenever required, and 5.9% infrequently. About 71.8% respondents attribute benefits to their preferred method of tooth cleaning. Nearly, 61.4% participants use miswak as primary oral hygiene method due to religious reasons. Majority of the participants, i.e. 70.2% were using miswak with taper and as a brush to clean all tooth surfaces. About 84.7% feel fresh, and teeth are whiter after the use of miswak whereas 4.4% respondents felt bitterness and increase in mouth acidity after use of miswak. 39.3% stored miswak for reuse in their upper pocket exposed to air, 19.3% in their upper pocket but covered while 23.9% stored it in their pocket after cutting off the used end. 13.9% discarded the miswak after single use. About 84.7% prefer to continue using miswak in combination with other teeth cleaning methods which may have more benefits. Nearly, 76.9% respondents would advise their children to use both toothbrushing and miswak in their daily oral hygiene practice whereas 5.5% advised only miswak for their children.

Table 1.

Comparison of males and females in terms of knowledge and attitude toward oral hygiene methods

Discussion

In our study, the types of oral hygiene aids that are used by participants are toothbrush (46.5%), miswak (8%), both using toothbrush and miswak (44.7%), and 0.4% do not use any of the mentioned oral hygiene aids. A similar study in Riyadh city showed that 82% respondents used toothbrush, 4% miswak while 3% used dental floss on daily basis. About 10% of the parents do not use any of the mentioned oral hygiene aids.[13] Similar study carried out in Jeddah city revealed that 84% of samples use toothbrush, 40% use miswak, and 20% use dental floss, respectively.[14] While the study in Riyadh revealed that 51.1% use toothbrush and 1% use miswak as the tooth cleaning aids.[15] While a study conducted in 2008 among 1115 male students in Al Hasa Saudi Arab reported that 45% were using miswak as a brushing tool.[16] This might be attributed to either difference in either venues or demographic origin or religious faith in both studies. Farsi et al. assessed the behavior, attitude, and knowledge in relation to periodontal health status in schoolgoing pupils. It was revealed that private schoolgoing pupils were more inclined toward the use of toothbrushes whereas governmental schoolgoing students used miswak as a main tool for maintaining oral health.[14] Another study by Wagner and Redford-Badwal identified low cultural knowledge among dental graduates.[17]

Our study reports that number of times daily using oral hygiene method either toothbrushing or miswak were 28.2% once daily, 37.6% twice daily, 28.4% whenever required, and 5.9% infrequently. In our study, the prevalence of daily brushing reported was similar to that reported in study conducted to assess the level and aspects of knowledge, attitudes, and practice related to oral health among pilgrims visiting Madinah.[18] They reported 21.2% of study participants were brushing once a daily, 30.7% brush twice a day, and 8.4% never brush. Similar study was reported in a Saudi Arabian study conducted in 2003 and found that 65% of students were doing brushing at least once.[19] When compared to another study conducted in Rijal Alma, Saudi Arabia is far less, they showed that 64.3% of the respondents cleaned their teeth once daily.[20] Toothbrushing with toothpaste is arguably the most common form of tooth cleaning practice by individuals in the industrialized countries whereas the chewing stick is often used as the sole cleansing agent by individuals in developing countries.[21] Most people in the developed countries show great interest in oral hygiene and that 16%–80% of boys in 32 countries in Europe and North America practiced tooth brushing more than once a day whereas girls reported better compliance 26%–89%.[22] While in India, only 69% of the population brush their teeth.[23] A national health survey in Pakistan showed that about 36% of the Pakistani population cleaned their teeth daily, irrespective of whether chewing sticks or toothbrush was employed, while 54% did so either on alternative days, weekly, or monthly.[24]

In our study, majority of the participants believe that use of miswak is due to religious reasons. Chewing sticks are considered the most popular among all of the dental care tools for their simplicity, availability, low cost, traditional, and religious value.[25] Because of the scientific merit of using miswak and the emphasis of using miswak as a cultural and religious belief among the Saudi population, the right method of using miswak as a cleaning technique to achieve maximum benefits should be stressed through various interventions. The right technique of using miswak should be taught.[14]

In our study, 84.7% prefer to continue using miswak in combination with other teeth cleaning methods which may have more benefits. In a study conducted in Jazan region, Saudi Arabia concluded that miswak stick was equally used with toothbrush for oral hygiene among secondary school students.[26] Another study was conducted to compare the effectiveness of two oral hygiene aids: chewing stick and manual toothbrush among dental students in Pakistan;[27] they concluded that chewing sticks (miswak) have revealed greater mechanical and chemical cleansing of oral tissues as compared to a toothbrush. Thus, this indicates that it may effectively and exclusively replace the toothbrush.

Conclusions

In our study, most common type of oral hygiene method employed is toothbrush and in combination with miswak. It is permitted to use toothbrush in combination with miswak for superior oral hygiene, and more possibilities should be explored to use miswak extracts in mouthwash and root canal irrigants. Chewing stick use was common among participants with religious advice being the dominant reason for usage. Evidence therefore suggests that miswak use along with tooth brushing can be a cost effective method to improve and maintain good oral health. In certain developing countries where use of toothbrush is still considered expensive, miswak is an ideal alternative oral hygiene tool. The overall knowledge regarding oral health was acceptable. Oral health promotion programs may be needed to improve oral health knowledge, attitude, and practices among developing countries.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gift HC, Atchison KA. Oral health, health, and health-related quality of life. Med Care. 1995;44:601–8. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199511001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdollahi M, Radfar M. A review of drug-induced oral reactions. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2003;4:10–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halawany HS. A review on miswak (Salvadora persica) and its effect on various aspects of oral health. Saudi Dent J. 2012;24:63–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sdentj.2011.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu CD, Darout IA, Skaug N. Chewing sticks: Timeless natural toothbrushes for oral cleansing. J Periodontal Res. 2001;36:275–84. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0765.2001.360502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Al-Sadhan RI, Almas K. Meswak (Chewing sticks); a cultural and scientific heritage. Saudi Dent J. 1999;11:80–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eid MA, Selim HA, al-Shammery AR. Relationship between chewing sticks (Miswak) and periodontal health. Part 1. Review of the literature and profile of the subjects. Quintessence Int. 1990;21:913–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patel PV, Shruthi S, Kumar S. Clinical effect of miswak as an adjunct to tooth brushing on gingivitis. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:84–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.94611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naseem S, Hashmi K, Fasih F, Sharafat S, Khanani R. In vitro evaluation of antimicrobial effect of miswak against common oral pathogens. Pak J Med Sci. 2014;30:398–403. doi: 10.12669/pjms.302.4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Oral Health Surveys: Basic Methods. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Obaida MI, Al-Essa MA, Asiri AA, Al-Rahla AA. Effectiveness of a 20% Miswak extract against a mixture of Candida albicans and Enterococcus faecalis. Saudi Med J. 2010;31:640–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Little JW. Complementary and alternative medicine: Impact on dentistry. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2004;98:137–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tripleo.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohan RP, Jacobsen PL. Herbal supplements: Considerations in dental practice. J Calif Dent Assoc. 2000;28:600–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Almulhim B, Alamro B. Knowledge and attitude toward oral health practice among the parents in Riyadh city. J Indian Acad Dent Spec Res. 2016;3:14–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farsi JM, Farghaly MM, Farsi N. Oral health knowledge, attitude and behaviour among Saudi school students in Jeddah city. J Dent. 2004;32:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wyne AH. Oral health knowledge in parents of Saudi cerebral palsy children. Neurosciences (Riyadh) 2007;12:306–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amin TT, Al-Abad BM. Oral hygiene practices, dental knowledge, dietary habits and their relation to caries among male primary school children in Al Hassa, Saudi Arabia. Int J Dent Hyg. 2008;6:361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wagner JA, Redford-Badwal D. Dental students’ beliefs about culture in patient care: Self-reported knowledge and importance. J Dent Educ. 2008;72:571–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abdulkhayum A, Bahakam O. Global oral health knowledge, attitude and practice among pilgrims visiting Madinah – A cross-sectional study. Eur J Pharma Med Res. 2017;4:8–14. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Sadhan SA. Oral health practices and dietary habits of intermediate school children in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Dent J. 2003;15:81–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Togoo RA, Yaseen SM, Zakirulla M, Nasim VS, Zamzami MA. Oral hygiene knowledge & practices among school children in a rural area of Southern Saudi Arabia. Int J Contemp Dent. 2012;3:57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Almas K, Al Shwaimi E, Al Shamrani H, Skaug N. The oral hygiene habits among intermediate and secondary schools students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Pak Oral Dent J. 2003;23:29–34. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maes L, Vereecken C, Vanobbergen J, Honkala S. Tooth brushing and social characteristics of families in 32 countries. Int Dent J. 2006;56:159–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.2006.tb00089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tewari A, Gauba K, Goyal A. Evaluation of existing status of knowledge, practice and attitude towards oral health of rural communities of Haryana – India. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 1991;9:21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asadi SG, Asadi ZG. Chewing sticks and the oral hygiene habits of the adult Pakistani population. Int Dent J. 1997;47:275–8. doi: 10.1002/j.1875-595x.1997.tb00789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riggs E, van Gemert C, Gussy M, Waters E, Kilpatrick N. Reflections on cultural diversity in oral health promotion and prevention. Glob Health Promot. 2012;19:60–3. doi: 10.1177/1757975911429872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ismail AD, Ali YM, Majed AA. Oral health related knowledge and behavior among secondary school students in Jazan region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Am J Health Res. 2016;4:138–42. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malik AS, Shaukat MS, Qureshi AA, Abdur R. Comparative effectiveness of chewing stick and toothbrush: A randomized clinical trial. N Am J Med Sci. 2014;6:333–7. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.136916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]