Abstract

Clozapine is more efficacious than first-generation antipsychotics for positive and negative symptoms, although it is related with serious adverse effects. Because of this profile, it could also have an impact on cognition. Therefore, we evaluated learning ability of 31 treatment-resistant individuals with SZ using clozapine uninterruptedly for 18.23 ± 4.71 years and 26 non-treatment-resistant using other antipsychotics that never used clozapine. Long-term treatment with clozapine did not improve verbal learning ability better than other antipsychotics. Although clozapine has a unique profile for reducing clinical symptoms, it may not have an additional benefit for cognition when started later on the course of schizophrenia.

Keywords: Treatment-resistant schizophrenia, Clozapine, Long-term, Memory

Dear Editors,

Clozapine is effective in treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS) (Davis et al., 2003). However, it is related with serious adverse effects, such as agranulocytosis, which is the main reason for not to be the initial treatment option. Nonetheless, clozapine is associated with a higher rate of relapse prevention in schizophrenia (SZ) (Tiihonen et al., 2017), and it significantly reduces the mortality rate (Wimberley et al., 2017). Importantly, clozapine is more efficacious than first-generation antipsychotics for both positive and negative symptoms, in addition to improving patient's quality of life (Leucht et al., 2009). Because of this broad profile, it could also have an impact on cognitive performance. There are a few studies in the literature that report cognitive effects of clozapine use, but they have several limitations such as small sample sizes and open-label design (e.g. Hagger et al., 1993). A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials reported improvements in overall cognition and in specific cognitive domains in patients treated with clozapine (Woodward et al., 2005). However, publication biases of these studies question the validity of the findings. Furthermore, the included studies had a median duration of 14 weeks. Therefore, it is unclear what are the long-term effects of clozapine on cognition, especially on the patients' potential of learning. Verbal memory and learning impairment are core features of SZ (Schaefer et al., 2013) and they are highly associated with functioning in everyday life domains (Danion et al., 2007), therefore should be a key focus of interventions.

In this study, we evaluated the learning ability of 57 individuals with SZ from an outpatient facility, 31 TRS that have been using clozapine uninterruptedly for 18.23 ± 4.71 years (mean ± SD) and 26 non-treatment-resistant (NTR) using other antipsychotics that never used clozapine. Clozapine was initiated 9.40 ± 6.79 years after the diagnosis of SZ in TRS group. Participants underwent an interview to collect clinical and sociodemographic data, and had their learning ability assessed with the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised (HVLT-R). HVLT-R is a word-list task that measures verbal learning and episodic memory, and it is part of the MATRICS Consensus Battery for SZ (Nuechterlein et al., 2008). This study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, all subjects were advised about the procedure and signed the informed consent prior to participation.

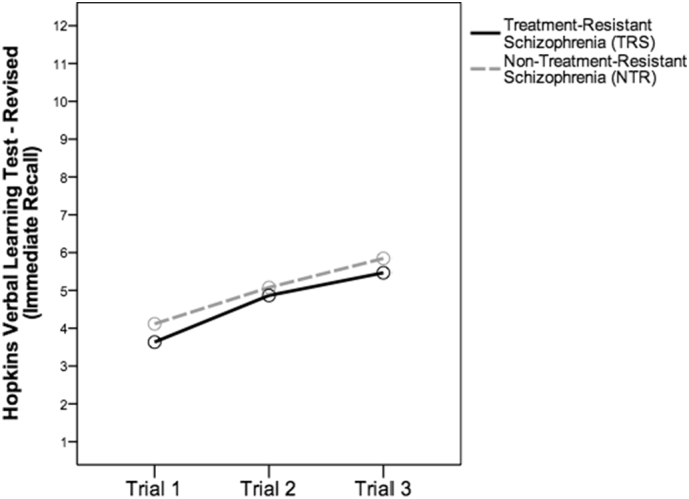

Participants had similar age in years (TRS: 48.48 ± 6.03, NTR: 51.27 ± 9.41, t(55) = −1.351, p = 0.182), illness duration in years (TRS: 27.42 ± 6.52, NTR: 25.81, t(55) = 0.770, p = 0.445), gender (TRS: 26 male, NTR: 17 male, χ2 (1) = 0.106, p = 0.131) and years of education (CZ: 9.19 ± 2.93, NZ: 8.35 ± 4.73, t(55) = 0.827, p = 0.412). TRS group had a younger age at diagnosis (CZ: 21.55 ± 4.07, NZ: 26.77 ± 8.13, t(35.29) = −2.977, p = 0.005) and currently had higher Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale 18-item (BPRS) total score (TRS: 17.52 ± 11.52, NTR: 11.54 ± 7.12, t(53) = 2.230, p = 0.03) and positive (sum of items 8, 11, 12, 15) scores (TRS: 5.23 ± 5.07, NTR: 1.92 ± 2.84, t(48.67) = 3.079, p = 0.003), but had similar negative scores (sum of items 3, 9, 13, 16) than NTR group (TRS: 4.26 ± 4.34, NTR: 3.60 ± 3.49, t(54) = 614, p = 0.542). The mean clozapine daily dose was 579.03 ± 175.01 mg for TRS group, and the mean antipsychotic daily dose of chlorpromazine equivalents was 566.20 ± 414.82 mg for NTR group. We performed a general linear model for the variance of the 3 trials of immediate recall across both groups and found that they had similar learning performances (F(54,1) = 0.499, p = 0.483) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Similar verbal learning performance in treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS) with long-term use of clozapine and non-treatment-resistant schizophrenia (NTR).

In our cross-sectional study, patients that had used clozapine for almost 20 years did not show better verbal learning ability than patients that used other antipsychotics. However, it has been recently suggested that clozapine should be used early in the disease for better functioning outcomes, ideally within the critical treatment window of up to 2.8 years after TRS diagnosis (Yoshimura et al., 2017), which was not the case for in our sample. Additionally, the TRS group presented higher scores on positive and total BPRS, and younger age at diagnosis, what could suggest more severity of the disease. Furthermore, these patients started the treatment with clozapine long after they were diagnosed (9.40 ± 6.79 years).

It is still unclear whether a prescription of this medication as a first line agent could prevent or improve cognitive impairment. However, it seems well stablished that the prescription should be at the time of TRS diagnosis. Although clozapine has a unique profile for reducing clinical symptoms, it may not have an additional benefit for cognitive performance better than other antipsychotics when started later on the course of schizophrenia. The present results have several limitations for more precise conclusions. Nonetheless, the available data converge to the need of follow-up studies in individuals with SZ at early use of clozapine to evaluate the cognitive performance.

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by CNPq, CAPES, FAPERGS and FIPE/HCPA, Brazil. It received grants from CNPq (Universal 443526/2014-1, PQ 304443/2014-0) and FAPERGS (PqG 17/2551-0001).

References

- Danion J.M., Huron C., Vidailhet P., Berna F. Functional mechanisms of episodic memory impairment in schizophrenia. Can. J. Psychiatr. 2007;52(11):693–701. doi: 10.1177/070674370705201103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis J.M., Chen N., Glick I.D. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of second-generation antipsychotics. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2003;60(6):553–564. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.6.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagger C., Buckley P., Kenny J.T., Friedman L., Ubogy D., Meltzer H.Y. Improvement in cognitive functions and psychiatric symptoms in treatment-refractory schizophrenic patients receiving clozapine. Biol. Psychiatry. 1993;34(10):702–712. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(93)90043-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S., Corves C., Arbter D., Engel R.R., Li C., Davis J.M. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):31–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein K.H., Green M.F., Kern R.S., Baade L.E., Barch D.M., Cohen J.D., Essock S., Fenton W.S., Frese F.J., 3rd, Gold J.M., Goldberg T., Heaton R.K., Keefe R.S., Kraemer H., Mesholam-Gately R., Seidman L.J., Stover E., Weinberger D.R., Young A.S., Zalcman S., Marder S.R. The MATRICS consensus cognitive battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):203–213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer J., Giangrande E., Weinberger D.R., Dickinson D. The global cognitive impairment in schizophrenia: consistent over decades and around the world. Schizophr. Res. 2013;150(1):42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiihonen J., Mittendorfer-Rutz E., Majak M., Mehtälä J., Hoti F., Jedenius E., Enkusson D., Leval A., Sermon J., Tanskanen A., Taipale H. Real-world effectiveness of antipsychotic treatments in a nationwide cohort of 29,823 patients with schizophrenia. JAMA Psychiat. 2017;74(7):686–693. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimberley T., MacCabe J.H., Laursen T.M., Sørensen H.J., Astrup A., Horsdal H.T., Gasse C., Støvring H. Mortality and self-harm in association with clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2017;174(10):990–998. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.16091097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward N.D., Purdon S.E., Meltzer H.Y., Zald D.H. A meta-analysis of neuropsychological change to clozapine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in schizophrenia. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8(3):457–472. doi: 10.1017/S146114570500516X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura B., Yada Y., So R., Takaki M., Yamada N. The critical treatment window of clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia: secondary analysis of an observational study. Psychiatry Res. 2017;250:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.01.064. Apr. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]