Abstract

Among adolescents, low socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with greater exposure to tobacco cigarette advertising and cigarette use. However, associations among SES, e-cigarette advertising and e-cigarette use are not well understood. This study examined exposure to e-cigarette advertisements as a mediator of the relationship between SES and adolescent e-cigarette use. Adolescents (N=3,473; 51% Female) from 8 high schools in Connecticut completed an anonymous survey in Spring 2015. Mediation analysis was used to examine whether the total number of sources of recent e-cigarette advertising exposure (e.g., TV, radio, billboards, magazines, local stores [gas stations, convenience stores], vape shops, mall kiosks, tobacco shops, social media) mediated the association between SES (measured by the Family Affluence Scale) and past-month frequency of e-cigarette use. We clustered for school and controlled for other tobacco product use, age, sex, race/ethnicity and perceived social norms for e-cigarette use in the model. Our sample recently had seen advertisements via 2.1 (SD = 2.8) advertising channels. Mediation was supported (indirect effect: β =.01, SE=.00, 95% CI [.001, .010], p=.02), such that higher SES was associated with greater recent advertising exposure, which, in turn, was associated with greater frequency of e-cigarette use. Our study suggests that regulations to reduce youth exposure to e-cigarette advertisement may be especially relevant to higher SES youth. Future research should examine these associations longitudinally and evaluate which types of advertisements target different SES groups.

Keywords: SES, advertising, e-cigarettes, adolescents

E-cigarettes are the most popular tobacco product among adolescents, with 11.3% of high school students reporting current use (Jamal, 2017). Understanding factors that contribute to the uptake of e-cigarettes may inform the development of interventions to prevent youth exposure to nicotine and other potentially harmful constituents of e-cigarettes. As noted in the recent Surgeon General’s report on e-cigarettes, nicotine sustains addiction and interferes with typical adolescent brain development (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2016). While there is limited understanding of the health effects of e-liquid constituents, emerging evidence suggests that e-cigarette constituents may pose cardiovascular and respiratory risks (Bhatnagar, 2017; Shields et al., 2017). Further, many recent studies, including our own, have also observed that e-cigarette use progresses to future cigarette use among youth (Bold et al., 2018; Soneji et al., 2017). Thus, e-cigs are not without risks (Bhatnagar, 2017; Shields et al., 2017) and e-cig use progresses to future cigarette use among youth (Bold et al., 2018; Soneji et al., 2017). It is especially important to examine factors that contribute to e-cigarette use among vulnerable populations, such as youth with low socioeconomic status (SES). Low SES is associated with increased tobacco use among youth, greater likelihood of progression to chronic cigarette smoking in adulthood, and greater difficulty quitting smoking, all of which contribute to downstream disparities in cardiovascular disease, cancer and tobacco-related mortality (Nandi et al., 2014; Stringhini et al., 2017). However, few studies have examined the associations between SES and factors that affect the uptake of e-cigarettes by youth.

SES and E-cigarette Use

Although studies of the association between SES and e-cigarette use are scant, a recent study reported that low SES is associated with greater likelihood of past-month e-cigarette use among adolescents (Simon et al., 2017). However, other studies examining associations with past-month (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2015) and lifetime e-cigarette use (Moore et al., 2015) have observed no association. In adults, preliminary evidence suggests that high SES is associated with current e-cigarette use among current cigarette smokers (Brown et al., 2014), and trying e-cigarettes for smoking cessation among daily smokers (Pokhrel et al., 2014). Given these varied findings, further research is needed to clarify the association between SES and adolescent e-cigarette use. While incorporating many important variables, none of the aforementioned studies incorporated advertising exposure, which is known to influence tobacco use (Mantey et al., 2016). Further research is also needed to explore potential mediators of the association between SES and e-cigarette use. A mediator is a variable that statistically accounts for the effects of an independent variable on a dependent variable, and when considered with theory, explains how or why variables are related (Baron and Kenny, 1986). Understanding mediators of the relationship between SES and e-cigarette use may support the development of regulations to reduce SES-based disparities in tobacco exposure by identifying malleable targets for regulation. For example, regulations may limit the quantity of advertising in areas that are disproportionately targeted by tobacco companies.

Advertising Exposure: A Potential Mediator of the Association between SES and E-cigarette use

Advertising exposure may mediate the relationship between SES and e-cigarette use. Research has shown that e-cigarette advertisement spending has increased from $6.4 million in 2011 to $115 million in 2014 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016), with the most popular sources of advertisement being retail stores, followed by internet, television, and magazines/newspapers (Duke et al., 2014; Singh et al., 2016). Nearly 70% of middle and high school students report seeing e-cigarette advertisements in these venues (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016). Consistent with advertising’s theorized and empirically demonstrated ability to influence consumer attitudes and behavior (Nichifor, 2014), exposure to e-cigarette advertising has been associated with intentions to use and use of e-cigarettes in adolescents (Farrelly et al., 2015; Mantey et al., 2016) and e-cigarette use among young adults (Pokhrel et al., 2015).

Traditionally, residing in a low SES community, rather than a high SES community, is associated with greater exposure to cigarette advertisements (Seidenberg et al., 2010). Specifically, low-income communities often have more tobacco retailers, larger advertisements, lower mean advertised prices, and more advertisements located near schools (Seidenberg et al., 2010). However, at least one study has shown that higher SES, rather than lower SES, is associated with e-cigarette advertisement exposure among adults (Emery et al., 2014). Although it remains unclear why this may occur, high SES groups may be targeted because they are more likely than low SES groups to be early adopters of new technology (Kennedy and Funk, 2016; Pampel et al., 2010; Rogers, 2010) or more likely to have disposable income to buy new products (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017). Moreover, e-cigarette use may be more socially acceptable because the potential harms are not perceived to be as high as those of traditional cigarettes, even in highly educated populations (Baeza-Loya et al., 2014). Despite evidence for differential exposure by SES among adults, the association between SES and adolescent e-cigarette advertising exposure is unknown. However, given the findings that higher SES is associated with greater exposure to e-cigarette messaging in adults (Emery et al., 2014), and exposure to e-cigarette advertising is associated with greater ever use, current use, and susceptibility to use of e-cigarettes in adolescents (Camenga et al., 2018; Mantey et al., 2016), it is plausible to expect that advertising exposure mediates the association between SES and e-cigarette use.

The Current Study

The current study is the first to examine whether exposure to e-cigarette advertisement mediates the relationship between SES and past-month frequency of e-cigarette use among adolescents, while controlling for predictors of adolescent e-cigarette use (i.e., grade-level, sex, race/ethnicity, perceived e-cigarette use norms, and prior tobacco use). Previous research has shown that boys are twice as likely as girls to currently use e-cigarettes (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2015), white youth are more likely than racial/ethnic minorities to use e-cigarettes (Anand et al., 2015), reporting peer and family use of e-cigarettes is associated with e-cigarette use (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2015), and use of other tobacco products is associated with e-cigarette use (Geidne et al., 2016). Although research on SES, advertisement exposure, and adolescent e-cigarette use is lacking, based on the adult literature on SES and e-cigarette use (Brown et al., 2014; Emery et al., 2014)., we hypothesized that adolescents from higher SES backgrounds will have greater exposure to e-cigarette advertisement and that this exposure will be associated with greater use of e-cigarettes.

Methods

Survey Procedures

Adolescents (N = 7,045) from 8 high schools in Connecticut completed a survey in Spring 2015. Study procedures were approved by the Yale University Institutional Review Board and school administrators. Schools from 7 of 9 district reference groups (i.e. 9 different groups of schools in Connecticut that respectively share similar family income, parental education, parental occupation, and use of a language other than English at home) participated in the survey. Parents were notified of the study and instructed to contact the school if they wanted their child excluded from the survey. As a result, 2 students were excluded. Research staff informed students that their participation was voluntary and that their data would remain anonymous. Following these consent procedures, school-wide, paper and pencil surveys were administered during homeroom. Students received pens to compensate them for their study participation.

Sample

Two versions of the survey that assessed tobacco-related attitudes and behaviors were randomly administered in each high school. The current analysis is based on the subset of adolescents (n = 3,473) who received the version containing all variables of interest in this study.

Measures

Frequency of E-cigarette Use

Following the prompt, “How many days out of the past 30 did you use e-cigarettes?”, participants wrote the number of days they had used e-cigarettes in the past 30 days.

Socioeconomic Status (SES)

SES was assessed using the Family Affluence Scale (FAS), which has shown to be a reliable and a valid measure of SES among adolescents (Boyce and Dallago, 2004; Boyce et al., 2006). The 4 items examine 1) whether an adolescent’s family owns a car, van, or truck (no = 0; yes one = 1; yes, two or more = 2), 2) whether an adolescent has his/her own bedroom (no = 0; yes = 1), 3) the number of laptops/computers an adolescent’s family owns (none = 0; 1 = 1; 2 = 2; more than 2 = 3), and 4) whether an adolescent’s family had vacationed in the past 12 months (not at all = 0; once = 1; twice = 2; more than twice = 3). A summary score was created from the four items, with higher scores indicating higher SES.

Exposure to Advertisements

Exposure to advertisements was assessed using the following item: “Where have you recently seen e-cigarette advertisements (select all the apply)?” Response options included: 1) TV, 2) radio, 3) billboard, 4) magazines, 5) local stores (gas stations, convenience stores), 6) vape shops, 7) mall kiosks, 8) tobacco shops, 9) social media, and 10) I did not see any. For each option, responses were coded 1 if participants had seen the specific type of advertisement and 0 if participants had not seen a specific type of advertisement. Similar to prior studies, we calculated the sum of advertising exposure by adding the responses for choices 1 to 9 (Kasza et al., 2011; Li et al., 2009; Yong et al., 2008). The International Tobacco Control Survey has shown that inquiring about places youth have seen tobacco advertisements is a valid method to assess exposure to advertising in youth (Fong et al., 2006).

Covariates

Demographics

Participants reported their sex (male or female), grade level (9th, 10th, 11th or 12th), and race/ethnicity (White, Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, Middle Eastern).

Perceived Social Norms

Three separate covariates provided continuous measures of perceptions of male peer, female peer and adult e-cigarette use. We adapted items that are valid and reliable for assessing perceived social norms in tobacco use (Chassin et al., 1984) and e-cigarettes (Petrescu et al., 2017). Specifically, adolescents answered the following questions: 1) what percentage of males your age do you think use e-cigarettes? 2) what percentage of females your age do you think use e-cigarettes? and 3) what percentage of adults do you think use e-cigarettes?

Other tobacco product use

Participants indicated whether they had ever tried any of the following tobacco products: cigarettes, cigars, smokeless tobacco, blunts, hookah or cigarillos (recoded as 1 = tried any other tobacco product, 0 = did not try any other tobacco product).

Data Analytic Plan

We examined descriptive statistics and bivariate associations using SPSS version 24 (IBM, 2012). We conducted mediation analyses using the Model Indirect command in MPlus 7.4 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998–2013) to examine whether the effect of SES on past-30-day frequency of e-cigarette use was mediated by advertising exposure. Model Indirect uses the product of the coefficients approach to mediation analyses (see MacKinnon et al., 2007 for a review). In this approach, the amount of mediation (or indirect effect) is defined as the product of the coefficient for the association between the independent variable (e.g. SES) and the mediator (adverting exposure) and coefficient for the association between the mediator and the dependent variable (frequency of past 30-day e-cigarette use). Statistical significance was determined with the delta method and a 95% confidence interval that did not contain 0 (MacKinnon et al., 2007). If the indirect effect is statistically significant, then mediation exists. We used full information maximum likelihood estimation with robust estimates to handle missing data. When modeling complex samples, this approach is robust to non-normality and non-independence of observations. For all variables, fewer than 2% of cases were missing data. Since frequency of e-cigarette use was a count variable, with 81% of participants reporting no use, we applied a negative binomial distribution. We controlled for the effects of sex, grade level, race/ethnicity, use of any tobacco product (other than e-cigarettes) and perceived social norms on exposure to advertisements and frequency of e-cigarette use. We also accounted for clustering by school.

Results

Participants

Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. The sample was 50.7% female. Regarding race/ethnicity, due to small sample size, the “Other” category comprised participants who indicated they were American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and Middle Eastern on the survey. Participants could select more than one race/ethnicity. Therefore, a Multiracial category was created for participants who checked more than one race. After these considerations, the sample was 52.7% White, 14.7% Latino/a Hispanic, 14.6% Black, 12.0% Multi-Race, 3.4% Asian, and 2.6% Other. Participants were evenly distributed across 9–12 grades (23.1% to 26.5% for each grade). Regarding perceived social norms, on average adolescents perceived that 43.3% of males their age, 32.4% of females their age, and 46.2% of adults used e-cigarettes.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | Value | |

|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||

| Family Affluence Scale (n = 3,471): Mean (SD) | 6.3 (1.8) | |

| Female (n = 3,422): % | 50.7 | |

| Grade (n = 2,448): % | ||

| 9 | 29.3 | |

| 10 | 25.7 | |

| 11 | 23.5 | |

| 12 | 21.6 | |

| Race/Ethnicity (n = 3,454): % | ||

| White | 52.7 | |

| Black | 14.6 | |

| Hispanic | 14.7 | |

| Asian | 3.4 | |

| Other | 2.6 | |

| Multiracial | 12.0 | |

| Tobacco Use Variables | ||

| Past 30-day number of days of e-cigarette use (n = 3,190): Mean (SD) | 1.1 (4.9) | |

| Tried other tobacco products (3,473): % | 39.0 | |

| Percent of males your age you think use e-cigarettes (n = 2,929): Mean (SD) | 43.3 (26.3) | |

| Percent of females your age you think use e-cigarettes (n = 2,934): Mean (SD) | 32.4 (24.3) | |

| Percent of adults you think use e-cigarettes (n = 2,916): Mean (SD) | 46.2 (27.4) | |

| Advertising Exposure | ||

| Sum of Advertising Exposure (n = 3,473): Mean (SD) | 2.1 (2.8) |

SD = Standard deviation

Participants are adolescents from Connecticut who were surveyed in 2015.

On average, adolescents used e-cigarettes on 1.1 days (SD = 4.9) over the past 30-days, with 81.0 % of participants reporting no use. Thirty-nine percent of adolescents had ever tried tobacco products other than e-cigarettes. Participants recently had seen advertisements via 2.1 (SD = 2.8) channels of advertisement. Participants reported seeing advertisements via local stores (36.3%), TV (32.7%), vape shops (32.7%), magazines (23.2%), social media (23%), tobacco shops (20.3%), mall kiosks (16.3%), billboards (15.1%), and radio (11.7%). Fewer than 1% of adolescents reported that they had not seen any advertisements. The average score on the FAS was 6.2 (SD = 1.82; range 0–9).

Bivariate correlations indicated that SES was positively associated with total advertising exposure and that total advertising exposure was positively associated with past 30-day use of e-cigarettes. However, SES was not associated with past 30-day use of e-cigarettes (see Table 2 which also includes associations with covariates).

Table 2.

Spearman Correlations for Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||||||||||||

| 1. Family Affluence Scale (FAS) | 1.000 | |||||||||||||

| 2. Female (ref: Male) | 0.023 | 1.000 | ||||||||||||

| 3. Grade | −0.023 | .043* | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| 4. Black | −.257** | −0.021 | 0.034 | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| 5. Hispanic | −.293** | 0.002 | −0.011 | - | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 6. Asian | −0.026 | −0.013 | 0.009 | - | - | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 7. Other | −.097** | −.046* | 0.015 | - | - | - | 1.00 | |||||||

| 8. Multiracial | −.149** | 0.006 | −0.023 | - | - | - | - | 1.00 | ||||||

| Tobacco Use Variables | ||||||||||||||

| 9. Past 30-day number of days of e-cigarette use | 0.013 | −.041* | 0.029 | −.122** | −0.039 | −0.008 | −0.009 | −.047* | 1.000 | |||||

| 10. Tried other tobacco products | −.094** | −0.018 | .164** | 0.027 | .124** | −.062** | .074** | .061** | .378** | 1.000 | ||||

| 11. % of males your age you think use e-cigarettes | −0.015 | .060** | −0.025 | −0.027 | .079** | −0.028 | 0.041 | −0.012 | .151** | .099** | 1.000 | |||

| 12. % of females your age you think use e-cigarettes | −.080** | .110** | −0.029 | 0.016 | .134** | 0.015 | .056* | .055* | .108** | .081** | .765** | 1.000 | ||

| 13. %of adults you think use e-cigarettes | −.075** | .126** | −.102** | .087** | .165** | −0.016 | 0.035 | .048* | .056** | .104** | .563** | .562** | 1.000 | |

| Advertising Exposure | ||||||||||||||

| 14. Sum of Advertising Exposure | .099** | .086** | 0.024 | −.069** | −0.025 | −0.038 | −0.006 | 0.040 | .140** | .130** | .111** | .116** | .100** | 1.000 |

. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed).

Participants are adolescents from Connecticut who were surveyed in 2015.

Correlations among race variables are not available, as these categories are mutually exclusive.

Ns ranged from 1,643 to 2,273 for variables that are mutually exclusive (i.e. race variables).

Ns range from 2,761 and 3,473 for variables that are not mutually exclusive.

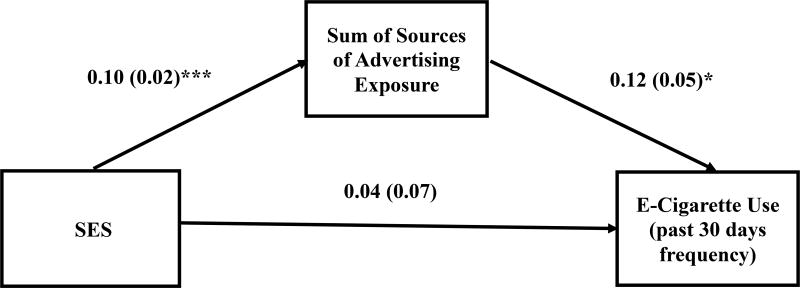

Mediation Analysis

Table 3 and Figure 1 show the results of the mediation analysis. Higher SES was associated with greater advertising exposure. Furthermore, exposure to more advertising was significantly associated with using e-cigarettes more frequently. The indirect effect of SES was modest, but statistically significant (β =.01, SE=.00, 95% CI [.001, .010], p=.02; B =.01, SE=.01, 95% CI [.003, .022], p=.01). The pattern of results suggest that SES indirectly influenced frequency of e-cigarette use such that higher SES was associated with greater exposure to e-cigarette advertising and this exposure was, in turn, associated with greater frequency of e-cigarette use.

Table 3.

Regression results predicting advertising exposure and number of days of e-cigarette us in the past 30 days

| Advertising Exposure Model | Days of E-cigarette Use Model | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Variables | β | B | SE | Est./S.E. | p | β | B | SE | Est./S.E. | p |

| Mediator | ||||||||||

| Sum of Advertising Exposure | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 2.47 | 0.014 |

| Independent Variable | ||||||||||

| SES | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.03 | 5.66 | 0.000 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.52 | 0.603 |

| Covariates | ||||||||||

| Female (ref: male) | 0.05 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 2.53 | 0.011 | −0.20 | −1.11 | 0.47 | −2.37 | 0.018 |

| Grade | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.45 | 0.654 | −0.16 | −0.89 | 0.37 | −2.40 | 0.016 |

| Black (ref: white) | −0.05 | −0.40 | 0.21 | −1.96 | 0.050 | −0.02 | −0.21 | 0.40 | −0.53 | 0.600 |

| Hispanic (ref: white) | −0.03 | −0.22 | 0.36 | −0.62 | 0.533 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.88 | 0.23 | 0.822 |

| Asian (ref: white) | −0.03 | −0.44 | 0.21 | −2.06 | 0.040 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.42 | −0.01 | 0.996 |

| Other (ref: white) | −0.01 | −0.09 | 0.35 | −0.27 | 0.789 | −0.18 | −0.69 | 0.34 | −2.03 | 0.042 |

| Multi-racial (ref: white) | 0.03 | 0.28 | 0.22 | 1.26 | 0.206 | −0.09 | −0.15 | 0.08 | −1.99 | 0.047 |

| Use of other tobacco products | 0.14 | 0.79 | 0.12 | 6.84 | 0.000 | 0.81 | 3.21 | 0.25 | 12.74 | 0.000 |

| % of males your age you think use e-cigarettes | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.87 | 0.062 | 0.39 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 3.64 | 0.000 |

| % of females your age you think use e-cigarettes | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 2.96 | 0.003 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.72 | 0.472 |

| % of adults you think use e-cigarettes | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 1.68 | 0.094 | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.71 | 0.477 |

Participants are adolescents from Connecticut who were surveyed in 2015. Standardized and unstandardized indirect effect of SES on frequency of e-cigarette use through advertising exposure: β =.01, SE=.00, 95% CI [.001, .010], p=.02; B =.01, SE=.01, 95% CI [.003, .022], p=.01

Figure 1.

Associations between SES and e-cigarette use through total number of sources of advertising exposure. Standardized estimates are shown with standard errors in parenthesis. Indirect effect: β =.01, SE=.00, 95% CI [.001, .010], p=.02. This model includes the following covariates: grade level in school, sex, race/ethnicity, having ever tried tobacco products other than e-cigarettes, and perceived social norms (i.e. perception of the percentage of adults, same age males and same age females who use e-cigarettes). Effects of covariates are not shown. This model also adjusts for clustering within school. Participants are adolescents from Connecticut who were surveyed in 2015. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Discussion

The current study is the first to demonstrate that exposure to e-cigarette advertisements mediates the relationship between SES and e-cigarette use in adolescents. Specifically, higher SES was associated with more exposure to e-cigarette advertising, and, in turn, with greater frequency of past month e-cigarette use. Our findings are consistent with prior research that has shown that higher SES is associated with greater exposure to e-cigarette messaging in adults (Emery et al., 2014) and research showing that exposure to e-cigarette advertising is associated with greater ever use, current use, and susceptibility to use of e-cigarettes in adolescents (Mantey et al., 2016). We did not observe a significant direct effect of SES on e-cigarette use, which is consistent with two prior studies (Barrington-Trimis et al., 2015; Moore et al., 2015), but not consistent with our prior research among a cohort sampled in 2014 which found that lower SES is associated with greater likelihood of e-cigarette use among adolescents (Simon et al., 2017). The difference in the association between SES and e-cigarette use in this study versus our prior cohort may be due to changes in the e-cigarette advertising climate. That is, research has shown that e-cigarette advertising has increased (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016), with widespread advertising exposure in higher SES communities (Emery et al., 2014). Alternatively, compared to our prior study, the current study included schools from a broader range of SES. The prior study included 3 schools from 3 of the 9 demographic reference groups (DRGs) in Connecticut whereas the current study included schools from 7 of 9 DRGS. The greater number of DRGs in the current study reflects increased variability in the range of socioeconomic background of communities and may provide a more accurate picture of SES differences in e-cigarette use.

Consistent with prior research showing that alternative tobacco products (including e-cigarettes) are more likely to be sold in higher income communities, higher SES adolescents in the current study reported being exposed to more e-cigarette advertisements than lower SES adolescents (Dai and Hao, 2016). Higher SES individuals may be more desirable targets for e-cigarette advertisements because they are more likely to adopt new technologies like e-cigarettes (Kennedy and Funk, 2016) and they have more disposable income to spend on e-cigarettes (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2017).

It is not clear how e-cigarette cost may influence e-cigarette use., a recent study that compared the cost of combustible cigarettes, disposable e-cigarettes and rechargeable e-cigarettes across 45 countries (including the US) found that a) combustible cigarettes cost less than disposable e-cigarettes in almost every country studied and b) e-liquids that are used with rechargeable e-cigarettes are cheaper per unit than combustible cigarettes, but the startup cost is high (Liber et al., 2017). Specifically, the study reported that in the US, the average cost of combustible cigarettes, disposable e-cigarettes and rechargeable e-cigarettes are $6.82, $7.99 and $9.99, respectively (Liber et al., 2017). Additional research is needed to determine the role of e-cigarette cost in use patterns among youth by SES.

This study highlights concerning levels of youth exposure to e-cigarette advertisement. Ninety-nine percent of youth reported exposure to one or more e-cigarette advertisements. Top sources for youth e-cigarette advertising exposure were local stores, TV, magazines and social media. It should be noted that one of the top sources of advertising for e-cigarettes was a context where cigarette advertisements have been banned (i.e., TV).

Our study has important implications for understanding disparities in nicotine exposure among youth as they relate to frequency of past month e-cigarette use. While tobacco regulation has contributed to steady declines in cigarette use among youth, these declines have occurred more quickly for higher SES rather than lower SES adolescents (Johnston et al., 2014). Considering the observed results, exposure to e-cigarette advertising among high SES youth may result in greater e-cigarette use among high SES youth, potentially slowing declines in nicotine exposure in this group, as many use e-cigarettes containing nicotine. Thus, efforts to reduce youth exposure to e-cigarette advertising may be especially relevant to high SES youth. Although the rates of advertising exposure generally were higher for high SES youth across all sources studied, regulatory efforts focused on targeting the top 4 advertising sources (i.e., local stores, TV, magazines, and social media) could significantly reduce exposure to e-cigarette advertising for all youth. Additionally, youth perceived high rates of use among their peers (males: 43.3%, female: 32.4%) and adults (46.2%). These perceived rates are higher than reported use rates (Dutra and Glantz, 2017; Schoenborn and Clarke, 2017). Perceiving such high rates of e-cigarette use is concerning, as social norms theory has linked such perceptions to future use (Perkins, 2003). These findings may point to the need for counter-marketing to correct perceptions among youth.

Although the results of this study have important implications for understanding youth e-cigarette use, they should be considered in light of several limitations. This study was cross-sectional, so the temporal ordering of the observed associations could not be determined definitively. Support for the direction examined in the current study is drawn from prior research that has used longitudinal data to demonstrate that advertising exposure predicted initiation of e-cigarettes (Camenga et al., 2018).

Another limitation is that this study relied on self-reported data and is therefore limited by participants’ ability and willingness to report honestly about their SES, e-cigarette use, and exposure to advertising. However, this concern is mitigated by the fact that our surveys were anonymous. An additional limitation is that detailed information about advertising (e.g., the specific timeframe of ad exposure, the frequency of exposure by channel or exposure to specific brands) was not collected. It is possible that seeing an advertisement everyday may be more influential than seeing an advertisement only once. At the same time, there are some advertisements that are so salient that the impact after viewing the advertisements once may be more influential than seeing other advertisements multiple times. Nevertheless, we used a method of assessing advertising exposure that has been valid in prior studies (Fong et al., 2006).. Future research should assess the effects of dose and salience of advertisements on e-cigarette use.

In conclusion, this study identified advertising exposure as a mediator of the association between SES and frequency of past month e-cigarette use. Specifically, high SES youth were more likely to report exposure to e-cigarette advertising, which, in turn, was associated with greater frequency of past month e-cigarette use. Identifying exposure to advertising as a potential mechanism through which SES exerts an effect on adolescent e-cigarette use is an important first step toward informing regulations to reduce disparities in nicotine exposure among high and low SES youth. Future research should continue to build upon this work by exploring the observed findings using longitudinal data, using more nuanced assessments of advertising exposure, and utilizing a nationally representative sample.

Highlights.

Mediators of the association between SES and e-cigarette use are yet unknown.

We examined data from 3,473 high school students.

Higher SES is associated with greater exposure to e-cigarette advertising.

Higher advertising exposure is associated with greater e-cigarette use.

Advertising exposure mediates the association between SES and e-cigarette use.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the FDA Center for Tobacco Products (CTP) [Yale TCORS P50DA036151]. PS’s efforts were partially supported by L40 DA042454. GK’s efforts are partially supported by National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University (CASAColumbia). KB’s efforts are supported by T32DA019426. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Food and Drug Administration.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Anand V, McGinty KL, O'Brien K, Guenthner G, Hahn E, Martin CA. E-cigarette use and beliefs among urban public high school students in North Carolina. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2015;57:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baeza-Loya S, Viswanath H, Carter A, Molfese DL, Velasquez KM, Baldwin PR, Thompson-Lake DGY, Sharp C, Fowler JC, et al. Perceptions about e-cigarette safety may lead to e-smoking during pregnancy. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic. 2014;78:243–52. doi: 10.1521/bumc.2014.78.3.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–82. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrington-Trimis JL, Berhane K, Unger JB, Cruz TB, Huh J, Leventhal AM, Urman R, Wang K, Howland S, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with adolescent electronic cigarette and cigarette use. Pediatrics. 2015;136:308–17. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar A. Are Electronic Cigarette Users at Increased Risk for Cardiovascular Disease? JAMA cardiology. 2017;2:237–38. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2016.5550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bold KW, Kong G, Camenga DR, Simon P, Cavallo D, Morean M, Krishnan-Sarin S. Youth tobacco use trajectories over time: e-cigarette use predicts subsequent cigarette smoking. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1):e20171832. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce W, Dallago L. Socioeconomic inequality. In: Currie C, Roberts C, Morgan A, Smith R, Settertobulte W, Samdal O, Rasmussen V, editors. Young people's health in context. Health behaviour in school-aged children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2001/2002 survey. 2004. pp. 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce W, Torsheim T, Currie C, Zambon A. The family affluence scale as a measure of national wealth: Validation of an adolescent self-report measure. Social Indicators Research. 2006;78:473–87. [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, West R, Beard E, Michie S, Shahab L, McNeill A. Prevalence and characteristics of e-cigarette users in Great Britain: Findings from a general population survey of smokers. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:1120–25. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camenga DR, Gutierrez KM, Kong G, Cavallo D, Simon P, Krishnan-Sarin S. E-cigarette advertising exposure in e-cigarette naïve adolescents and subsequent e-cigarette use: A longitudinal cohort study. Addictive Behaviors. 2018;81:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. E-cigarette Ads and Youth. CDC Vitalsigns; Atlanta, GA: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, Corty E, Olshavsky RW. Predicting the onset of cigarette smoking in adolescents: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1984;14:224–43. [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, Hao J. Geographic density and proximity of vape shops to colleges in the USA. Tobacco Control. 2016;26:379–85. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke JC, Lee YO, Kim AE, Watson KA, Arnold KY, Nonnemaker JM, Porter L. Exposure to electronic cigarette television advertisements among youth and young adults. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e29–e36. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra LM, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and national adolescent cigarette use: 2004–2014. Pediatrics. 2017 doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2450. e20162450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery SL, Vera L, Huang J, Szczypka G. Wanna know about vaping? Patterns of message exposure, seeking and sharing information about e-cigarettes across media platforms. Tobacco Control. 2014;23:iii17–iii25. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrelly MC, Duke JC, Crankshaw EC, Eggers ME, Lee YO, Nonnemaker JM, Kim AE, Porter L. A randomized trial of the effect of e-cigarette TV advertisements on intentions to use e-cigarettes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;49:686–93. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong GT, Cummings KM, Borland R, Hastings G, Hyland A, Giovino GA, Hammond D, Thompson ME. The conceptual framework of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project. Tobacco Control. 2006;15:iii3. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.015438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geidne S, Beckman L, Edvardsson I, Hulldin J. Prevalence and risk factors of electronic cigarette use among adolescents: Data from four Swedish municipalities. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2016;33:225–40. [Google Scholar]

- IBM. Version 21. IBM; Armonk, New York, USA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A. Tobacco Use Among Middle and High School Students—United States, 2011–2016. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2017;66 doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6623a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg J, Miech R. Demographic subgroup trends among adolescents in the use of various licit and illicit drugs, 1975–2013 (Monitoring the Future Occasional Paper No. 81) Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan, Institute for Social Research; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kasza KA, Hyland AJ, Brown A, Siahpush M, Yong H-H, McNeill AD, Li L, Cummings KM. The Effectiveness of Tobacco Marketing Regulations on Reducing Smokers’ Exposure to Advertising and Promotion: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2011;8:321–40. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8020321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy B, Funk C. 28% of Americans are ‘strong’early adopters of technology. Pew Research Center 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Yong HH, Borland R, Fong GT, Thompson ME, Jiang Y, Yang Y, Sirirassamee B, Hastings G, et al. Reported awareness of tobacco advertising and promotion in China compared to Thailand, Australia and the USA. Tobacco Control. 2009;18:222–27. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.027037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liber AC, Drope JM, Stoklosa M. Combustible cigarettes cost less to use than e-cigarettes: global evidence and tax policy implications. Tobacco Control. 2017;26:158–63. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Fairchild AJ, Fritz MS. Mediation analysis. Annual Review of Psychology. 2007;58:593–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantey DS, Cooper MR, Clendennen SL, Pasch KE, Perry CL. E-cigarette marketing exposure is associated with e-cigarette use among US youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2016;58:686–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore G, Hewitt G, Evans J, Littlecott HJ, Holliday J, Ahmed N, Moore L, Murphy S, Fletcher A. Electronic-cigarette use among young people in Wales: Evidence from two cross-sectional surveys. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007072. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén L. Mplus Version 7: User’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2013. [Google Scholar]

- Nandi A, Glymour MM, Subramanian S. Association among socioeconomic status, health behaviors, and all-cause mortality in the United States. Epidemiology. 2014;25:170–77. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nichifor B. Theoretical framework of advertising-some insights. Studies and Scientific Researches. 2014 Economics Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Pampel FC, Krueger PM, Denney JT. Socioeconomic Disparities in Health Behaviors. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010;36:349–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins H. The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse: A handbook for educators, counselors, and clinicians. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Petrescu DC, Vasiljevic M, Pepper JK, Ribisl KM, Marteau TM. What is the impact of e-cigarette adverts on children's perceptions of tobacco smoking? An experimental study. Tobacco Control. 2017;26:421. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-052940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Fagan P, Kehl L, Herzog TA. Receptivity to e-cigarette marketing, harm perceptions, and e-cigarette use. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2015;39:121–31. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.39.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pokhrel P, Little MA, Fagan P, Kawamoto CT, Herzog TA. Correlates of use of electronic cigarettes versus Nicotine Replacement Therapy for help with smoking cessation. Addictive behaviors. 2014;39:1869–73. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.07.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. Simon and Schuster: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenborn CA, Clarke TC. QuickStats: Percentage of Adults Who Ever Used an Ecigarette and Percentage Who Currently Use E-cigarettes, by Age Group-National Health Interview Survey, United States, 2016 (vol 66, pg 892, 2016) MMWR-Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2017;66:1238–38. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6633a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidenberg AB, Caughey RW, Rees VW, Connolly GN. Storefront cigarette advertising differs by community demographic profile. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2010;24:e26–e31. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.090618-QUAN-196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields PG, Berman M, Brasky TM, Freudenheim JL, Mathe E, McElroy JP, Song MA, Wewers MD. A Review of Pulmonary Toxicity of Electronic Cigarettes in the Context of Smoking: A Focus on Inflammation. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology. 2017;26:1175–91. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon P, Camenga DR, Kong G, Connell CM, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, Krishnan-Sarin S. Youth e-cigarette, blunt, and other tobacco use profiles: Does SES matter? Tobacco Regulatory Science. 2017;3:115–27. doi: 10.18001/TRS.3.1.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh T, Marynak K, Arrazola RA, Cox S, Rolle IV, King BA. Vital signs: Exposure to electronic cigarette advertising among middle school and high school students—United States, 2014. MMWR Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;64:1403–08. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6452a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, Leventhal AM, Unger JB, Gibson LA, Yang J, Primack BA, Andrews JA, et al. Association Between Initial Use of e-Cigarettes and Subsequent Cigarette Smoking Among Adolescents and Young Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA pediatrics. 2017;171:788–97. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringhini S, Carmeli C, Jokela M, Avendaño M, Muennig P, Guida F, Ricceri F, d'Errico A, Barros H, et al. Socioeconomic status and the 25 × 25 risk factors as determinants of premature mortality: A multicohort study and meta-analysis of 1·7 million men and women. The Lancet. 2017;389:1229–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32380-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Expenditures in 2015. BLS Reports 2017 [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2016. E-Cigarette use among youth and young adults. [Google Scholar]

- Yong H, Borland R, Hammond D, Sirirassamee B, Ritthiphakdee B, Awang R, Omar M, Kin F, Zain ZBM, et al. Levels and correlates of awareness of tobacco promotional activities among adult smokers in Malaysia and Thailand: findings from the International Tobacco Control Southeast Asia (ITC-SEA) Survey. Tobacco Control. 2008;17:46–52. doi: 10.1136/tc.2007.021964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]