ABSTRACT

Few studies have been conducted on the susceptibility of bacteria to biocides. A total of 182 methicillin-resistant and -susceptible Staphylococcus aureus isolates collected from healthy or diseased humans and animals in Germany were included in the present study. Sixty-three isolates of animal origin and 119 human isolates were tested for their MICs to eight biocides or heavy metals by the broth microdilution method. The MIC50 and MIC90 values of human and animal isolates were equal or differed by not more than 1 dilution step, and statistical analysis revealed that differences between MICs of human and animal isolates were not significant. However, when taking into account the multilocus sequence type (MLST), a strong tendency (P = 0.054) to higher MICs of silver nitrate was detected for clonal complex 398 (CC398) isolates from humans compared to those from animals. Furthermore, a comparison of MIC values from isolates belonging to different clonal lineages revealed that important human lineages such as CC22 and CC5 exhibited significantly (P < 0.05) higher MICs for the biocides chlorhexidine, benzethonium chloride, and acriflavine than the main animal lineage sequence type 398 (ST398). Isolates with elevated MIC values were tested for the presence of biocide and heavy metal tolerance-mediating genes by PCR assays, and the following genes were detected: mepA (n [no. of isolates containing the gene] = 44), lmrS (n = 36), norA (n = 35), sepA (n = 22), mco (n = 5), czrC (n = 3), smr (n = 2), copA (n = 1), qacA and/or -B (n = 1), qacG (n = 2), and qacJ (n = 1). However, only for some compounds was a correlation between the presence of a biocide tolerance gene and the level of MIC values detected.

IMPORTANCE Biocides play an essential role in controlling the growth of microorganisms and the dissemination of nosocomial pathogens. In this study, we determined the susceptibility of methicillin-resistant and -susceptible S. aureus isolates from humans and animals to various biocides and heavy metal ions and analyzed differences in susceptibilities between important clonal lineages. In addition, the presence of biocide or heavy metal tolerance-mediating genes was investigated. We demonstrated that important human lineages such as CC22 and CC5 had significantly higher MIC values for chlorhexidine, benzethonium chloride, and acriflavine than the main farm animal lineage, ST398. In addition, it was shown that for some combinations of biocides and tolerance genes, significantly higher MICs were detected for carriers. These findings provide new insights into S. aureus biocide and heavy metal tolerance.

KEYWORDS: MIC values, susceptibility testing, Staphylococcus aureus, biocides, heavy metals, tolerance

INTRODUCTION

Staphylococcus aureus is a frequent colonizer of the nasal vestibules of humans and also of a large number of animal species (1, 2). Beyond asymptomatic carriage, S. aureus (in particular, methicillin-resistant S. aureus [MRSA]) regarded as one of the most important human nosocomial pathogens worldwide and are able to cause clinical conditions ranging from mild skin infections to life-threatening invasive infections (3). In animals, there are a variety of diseases caused by S. aureus, such as mastitis, botryomycosis, and urinary tract infections (4). Even though farm animals are often carriers of MRSA, they are only rarely infected. The frequent occurrence of MRSA, mainly of clonal complex 398 (CC398), in livestock and occasionally in humans exposed to livestock is a serious public health concern since transmission between animals and humans cannot be excluded (1, 4, 5).

To control the growth of microorganisms and the dissemination of nosocomial pathogens, biocides play an essential role and are used extensively for many topical and hard-surface applications (6, 7). The quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs) acriflavine, alkyldiaminoethyl glycine hydrochloride, benzalkonium chloride, and benzethonium chloride are membrane-active agents targeting the cytoplasmic membrane of bacteria. They are used as antiseptics and disinfectants for many clinical purposes, but also for hard-surface cleaning and deodorization (7, 8). Chlorhexidine, a bisbiguanide, is one of the most widely used active ingredients in antiseptic products and has long been used for its disinfectant and preservative properties. Of note, the biocide is included in decolonization strategies to decrease MRSA rates in hospitals (9). Chlorhexidine damages the outer cell layers and attacks the cytoplasmic membrane of bacteria (7). It has long been known that heavy metal ions such as Ag+, Co2+, and Zn2+ develop antimicrobial activity, and some compounds have been used for centuries (7, 10). Silver compounds are in use especially for the treatment of burns, chronic wounds, and eye infections, while nano-silver is used as a coating substance, e.g., for medical devices, food contact materials, or cosmetic products (11). In contrast, copper sulfate, zinc oxide, and much less frequently zinc chloride are used in livestock production as supplements to animal feed to reduce microbial growth (12). As a mode of action, an interaction of heavy metals such as silver salts with specific groups in enzymes and proteins or direct damage to bacterial membranes is assumed (7, 13).

While resistance to antibiotics is common, tolerance to biocides is believed to occur more rarely due to the multiplicity of targets within the bacterial cell (14). However, there are reports of MRSA with decreased susceptibility to various biocides or heavy metals, including benzalkonium chloride, chlorhexidine, and zinc chloride (15, 16). Tolerance to biocides is mainly a result from alterations in the cell envelope, enhanced efflux pump activity, or, notably in staphylococci, the acquisition of plasmid-mediated genes (7, 14).

Therefore the aims of the present study were (i) to determine the susceptibility of methicillin-resistant and -susceptible S. aureus isolates to various biocides and heavy metal ions, (ii) to analyze differences in susceptibilities between important clonal lineages, and (iii) to identify genetic determinants involved in biocide or heavy metal tolerance.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Results from biocide and heavy metal susceptibility testing.

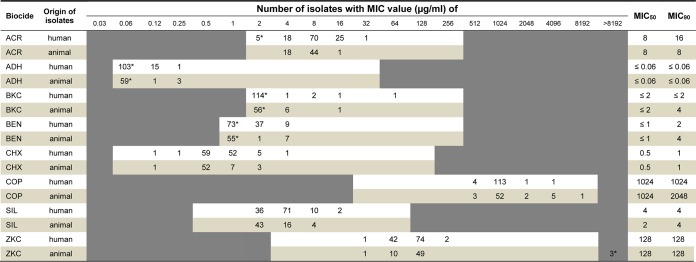

The results from susceptibility testing are shown in Table 1. The MIC values of the isolates ranged between ≤2 and 32 μg/ml acriflavine, ≤0.06 and 0.25 μg/ml alkyldiaminoethyl glycine hydrochloride, ≤2 and 64 μg/ml benzalkonium chloride, ≤1 and 4 μg/ml benzethonium chloride, 0.12 and 4 μg/ml chlorhexidine, 512 and 8,192 μg/ml copper sulfate, 2 and 16 μg/ml silver nitrate, and 32 and >8,192 μg/ml zinc chloride. Unimodal distributions of MICs were detected for most biocides and heavy metal ions, with the exception of benzalkonium chloride and zinc chloride, for which a bimodal (or multimodal) distribution was found. A bimodal distribution is considered to be indicative for the presence of an antibiotic-resistant (or less-susceptible) subpopulation of bacteria, typically due to mutational or acquired mechanisms of resistance (17). With regard to biocides, inconsistent findings have been reported. For most combinations of bacteria and biocides, unimodal distributions of MIC values were obtained. Even in the presence of genes known to mediate tolerance to biocides or heavy metals (e.g., qac genes in S. aureus), a unimodal distribution pattern of MICs was detected (17, 18). However, bimodal distributions were detected for specific combinations, such as S. aureus and triclosan susceptibility, Enterobacter and chlorhexidine susceptibility, or triclosan susceptibility of Escherichia coli and Enterobacter (17, 19).

TABLE 1.

Distribution of Staphylococcus aureus MIC values for biocides and heavy metal ionsa

ACR, acriflavine; ADH, alkyldiaminoethyl glycine hydrochloride; BKC, benzalkonium chloride; BEN, benzethonium chloride; CHX, chlorhexidine; COP, copper sulfate; SIL, silver nitrate; ZKC, zinc chloride. Asterisks indicate the number of isolates exhibiting a MIC that is greater than the highest concentration tested or less than or equal to the lowest concentration tested. The white and light-colored areas represent the tested ranges of biocides.

In the present study, the MIC50 and MIC90 values of almost all biocides or heavy metals were equal or differed by not more than 1 or 2 dilution steps. Only slight differences were detected between MIC50 and MIC90 values of human and animal isolates (Table 1). Slightly higher MIC90 values of animal isolates were found for benzalkonium chloride, benzethonium chloride, and copper sulfate, whereas isolates collected from humans exhibited higher MIC50 values of silver nitrate and higher MIC90 values of acriflavine (Table 1). In a study recently published by Morrissey et al. (17), S. aureus epidemiological cutoff values (ECOFFs) were set for the biocides chlorhexidine (8 μg/ml) and benzalkonium chloride (16 μg/ml) to differentiate a wild-type from a non-wild-type MIC phenotype. According to these ECOFFs, none of the isolates of the present study was considered non-wild type for chlorhexidine, with MIC50 and MIC90 values lower than those in the comparative study. In contrast, three isolates from the present strain collection from Germany were classified as benzalkonium chloride non-wild type, and MIC50/90 values were in a comparable range (17). However, it has to be taken into account that ECOFFs were only derived from human S. aureus isolates and did not include MICs of isolates from animals (17). Furthermore, analysis of 1,602 clinical S. aureus isolates by Furi and coworkers did not uncover a clear indication for chlorhexidine and benzalkonium chloride ECOFF values (18). For the other biocides and heavy metals tested, a classification of isolates as wild type or non-wild type was hampered by the lack of proposed ECOFF values. However, ECOFFs estimated by visual inspection of MIC distributions indicated values of ≥64 μg/ml for acriflavine, ≥0.5 μg/ml for alkyldiaminoethyl glycine hydrochloride, ≥8 μg/ml for benzalkonium chloride, ≥8 μg/ml for benzethonium chloride, ≥6 μg/ml for chlorhexidine, ≥4,096 for copper sulfate, ≥32 μg/ml for silver nitrate, and ≥512 μg/ml for zinc chloride for this strain collection.

Comparison of results from the present study to those of further studies is problematic, since different concentrations of biocides and heavy metals were tested and/or the methodologies used for MIC determinations were not identical (15, 20, 21). However, in a study from the United States, a broth dilution method according to CLSI guidelines was also used to determine chlorhexidine MICs of 829 MRSA isolates from nursing home residents. The values were 4-fold higher than those of the German isolates (22). Results from a study on 95 MRSA and 164 MSSA isolates from Malaysia revealed higher MIC values for benzethonium chloride, benzalkonium chloride (range of 3.9 to 15.6 μg/ml for both) and chlorhexidine (range of 10.3 to 20.7 μg/ml) than isolates of the present study (23). Similar ranges of MIC values (4 to 16 μg/ml) were detected in a study by Randall and coworkers, who investigated the susceptibility to silver nitrate of staphylococci collected between 1997 and 2010 in hospitals throughout Europe and Canada (13). Another study described chlorhexidine MIC values from 219 methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and 82 MRSA isolates that were collected in three African countries. There was a close similarity between the observed MIC range and the MICs of 90% of the isolates compared to the values found in the present study (24). In another study from Denmark, MICs of 43 S. aureus isolates obtained from farm animals were determined (12). The ranges of MICs for benzalkonium chloride and chlorhexidine were in good accordance with our results from animal isolates. However, MIC values for copper sulfate (lower) and zinc chloride (higher) differed slightly from MICs obtained in the present study.

Comparison of MIC values between isolates from animals and humans and between different clonal lineages.

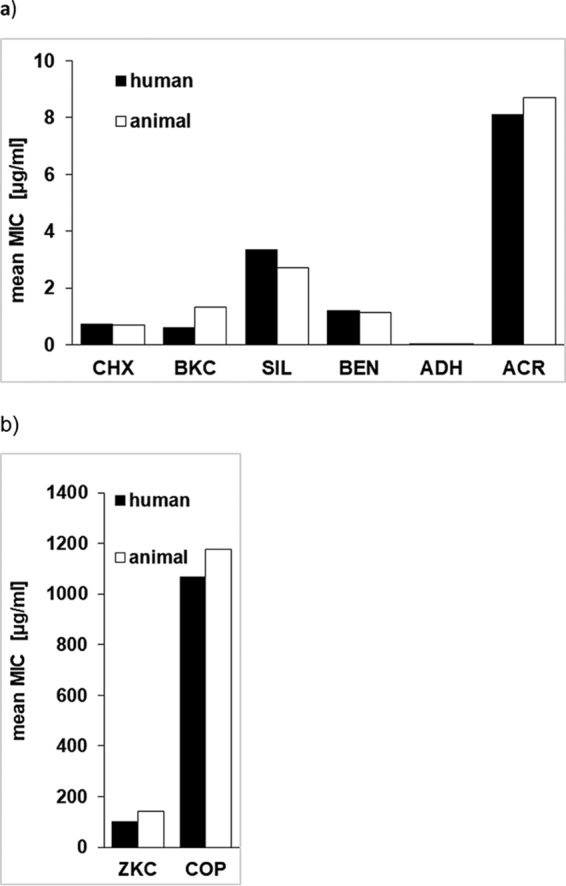

To detect differences in the susceptibilities of isolates from humans and animals and between isolates belonging to different clonal lineages, statistical analysis was performed. Although slight differences in MIC50/90 values from human and animal isolates were observed for some of the biocides (Table 1), statistical analysis revealed that MICs of human and animal isolates did not differ significantly (P > 0.05) (Fig. 1). Taking into account the MLST genotype, the results showed a strong tendency (P = 0.054) to higher MIC values of silver nitrate for human CC398 isolates compared to animal CC398 isolates. Since silver salts are in use for some clinical purposes, one might speculate that the selection pressure imposed by the use of silver led to higher MIC values of human isolates. For the other genotypes (CC5, CC9, and CC22), statistical analysis was not carried out due to the uneven distribution of human and animal isolates within the clonal lineages.

FIG 1.

Comparison of mean MIC values of silver nitrate (SIL), chlorhexidine (CHX), alkyldiaminoethyl glycine hydrochloride (ADH), benzethonium chloride (BEN), benzalkonium chloride (BKC), and acriflavine (ACR) (a) and zinc chloride (ZKC) and copper sulfate (COP) (b) between S. aureus isolates originating from humans and animals.

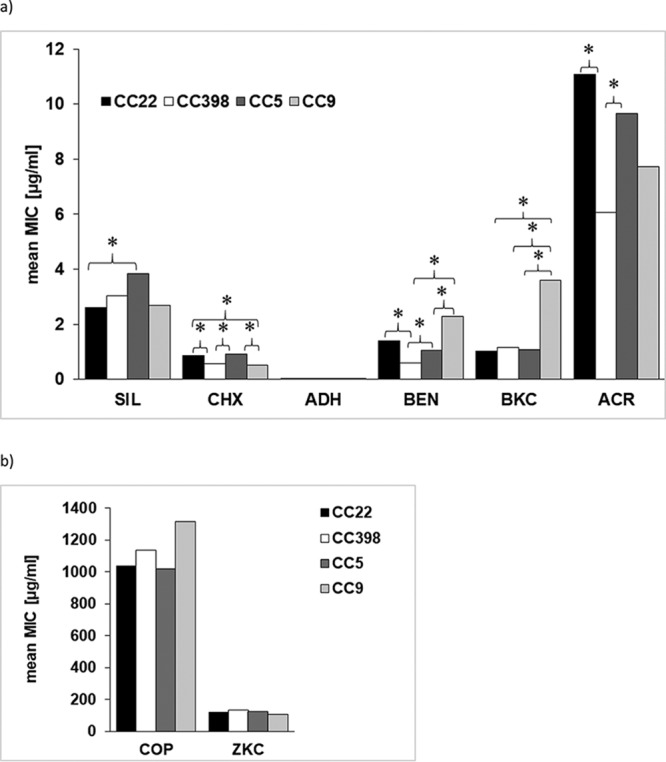

Analysis of differences in MIC values between clonal lineages (independent of the origin of isolates from humans or animals) revealed that isolates belonging to CC22 and CC5 (clonal lineages that are considered typically human and among the most frequently occurring lineages in Germany) exhibited significantly higher MICs of chlorhexidine (P = 0.0017 and P = 0.0002, respectively), benzethonium chloride (P < 0.0001 and P = 0.002), and acriflavine (P = 0.0002 and P = 0.0024) than isolates of sequence type 398 (ST398) (Fig. 2). The biocides chlorhexidine and benzethonium chloride are frequently used in hospitals, e.g., for MRSA decolonization and as active ingredients in household products (25, 26). Isolates of the lineages CC22 and CC5 also had significantly higher MICs of chlorhexidine (P = 0.0078 and P = 0.0032, respectively) than ST9 isolates. In contrast, isolates of ST9 showed significantly higher MIC values of benzalkonium chloride than isolates of the lineages CC22 (P < 0.0001), CC5 (P = 0.0002), and ST398 (P < 0.0001), and they exhibited higher MIC values of benzethonium chloride than CC5 (P = 0.0196) and ST398 (P < 0.0001) isolates. Furthermore, isolates of CC22 exhibited significantly (P = 0.005) lower MIC values of silver nitrate than isolates of CC5. For the other heavy metals (zinc chloride and copper sulfate) and biocides tested, no significant differences were detected between sequence types. The heavy metals copper and zinc are currently in use as feed additives in livestock farming (27). Zinc, mostly in form of zinc oxide, can be administered to piglets for 2 to 3 weeks postweaning as an antibiotic alternative to prevent colibacillosis, while copper sulfate is used to suppress bacterial action in the gut of farm animals with the objective of maximizing feed utilization (27, 28). Therefore, divergences in the susceptibilities between human and animal isolates or between clonal lineages to zinc chloride might have been expected, but did not come true for this strain collection. Statistically significant differences could also not be seen between isolates from diseased or colonized hosts. In addition, it should be noted that for some sequence types (e.g., ST9), only a limited number of isolates was available. Therefore, the results should be confirmed by including a greater number of isolates of this lineage.

FIG 2.

Comparison of mean MIC values of silver nitrate (SIL), chlorhexidine (CHX), alkyldiaminoethyl glycine hydrochloride (ADH), benzethonium chloride (BEN), benzalkonium chloride (BKC), and acriflavine (ACR) (a) and zinc chloride (ZKC) and copper sulfate (COP) (b) between S. aureus isolates belonging to clonal complexes CC22, CC398, CC5, and CC9. Statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) are indicated by asterisks.

PCR screening for the presence of biocide and heavy metal tolerance genes and localization on plasmids.

Isolates with MICs of ≥4 μg/ml benzalkonium chloride and/or 4 μg/ml benzethonium chloride (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) were screened for the presence of the genes qacA and/or qacB (here named “qacA/B” since the PCR assay detects both genes), qacG, qacH, qacJ, smr, norA, mepA, sepA, and lmrS, which are known to be involved in tolerance to quaternary ammonium compounds. A total of 10 isolates exhibited elevated MICs for both biocides, while 8 isolates from humans showed decreased susceptibility only to benzalkonium chloride (2 isolates) or benzethonium chloride (6 isolates). PCR analysis demonstrated that all isolates harbored mepA, and all except one were positive for the gene lmrS, while norA was detected in 13 isolates, sepA in 4 isolates, and smr in 2 isolates. Single isolates were positive for the qacA/B, qacG, and qacJ resistance genes (Table 2; Table S1). The gene qacH was not detected in our strain collection. Subsequent sequence analysis of the qacA/B PCR amplicon confirmed the presence of qacA in our strain collection. In contrast to the chromosomally located genes norA, lmrS, mepA, and sepA, the gene smr was found to be located on plasmids with estimated sizes of >25 kb in two MRSA isolates (ST225 and CC22, respectively). A plasmid localization of the genes qacA, qacB, and smr was previously reported for the majority of Staphylococcus species isolates (29–31). Nevertheless, the qacA/B gene was detected in the chromosome of a human ST45 MRSA isolate in this strain collection, whereas the genes qacG and qacJ were located on small plasmids of approximately 1.5 to 2.0 kb in the CC80 and ST398 strains. With regard to the chromosomally located genes norA and sepA, frequent occurrence in staphylococci (>90%) has recently been reported (32). In another study of clinical MRSA isolates from the United Kingdom, only 36.7% of isolates were positive for norA (33). In this study, the gene norA was present in 13 out of 18 isolates with elevated MICs. However, whether point mutations in the primer binding sites caused negative results in PCR assays for the chromosome-mediated determinants, as recently assumed by Liu and coworkers (32), remains to be clarified, just like the expression levels of the efflux genes.

TABLE 2.

PCR analysis of isolates and presence of biocide or heavy metal tolerance-mediating genes

| Biocide or heavy metal | MIC (μg/ml) | No. of isolates investigateda | No. of isolates positive for geneb | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quaternary ammonium compounds | lmrS | mepA | norA | sepA | qacA/B | qacG | qacH | qacJ | smr | ||

| Benzalkonium chloride | ≥4 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |||

| Benzethonium chloride | ≥4 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 11 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Acriflavine | ≥16 | 27 | 21 | 27 | 21 | 19 | 2 | ||||

| Bisbiguanides | lmrS | mepA | norA | sepA | qacA/B | qacG | qacH | qacJ | smr | ||

| Chlorhexidine | ≥2 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 5 | 3 | |||||

| Heavy metal ions | copA | mco | czrC | ||||||||

| Copper sulfate | ≥4,096 | 7 | 1 | 5 | NT | ||||||

| Zinc chloride | >8,192 | 3 | NT | NT | 3 | ||||||

Some isolates were included in PCR screening for more than one biocide or heavy metal ion and may therefore be listed repeatedly in this table.

NT, isolates were not tested for the tolerance-mediating genes listed above.

Of the 27 isolates with MIC values of ≥16 μg/ml acriflavine, all were positive for mepA, 21 were positive for norA, 21 for lmrS, 19 for sepA, and 2 for smr (Table S1). Only 6 of these isolates (including both smr-positive isolates) showed elevated MICs of benzalkonium chloride or benzethonium chloride, even though the norA, sepA, smr, and qac genes are known to be involved in tolerance to all quaternary ammonium compounds tested (34–36).

In eight out of nine isolates with a MIC of ≥2 μg/ml chlorhexidine, the gene lmrS was detected. Of these, five isolates additionally carried norA and two isolates sepA, and a single isolate was positive for sepA and norA, while neither qacA/B, qacG, qacH, qacJ, nor smr was present in isolates with elevated MICs. However, a correlation between the presence of tolerance-mediating genes and the level of MIC values could not been detected. This is in good accordance with a study by Skovgaard et al., who did not detect an association between the presence of qac genes and altered chlorhexidine susceptibility (37).

Among seven isolates with MICs of ≥4,096 μg/ml copper sulfate, five were positive for the gene mco encoding a multicopper oxidase. One of them carried a plasmid-located copper resistance gene, copA, in addition to mco; however, this isolate did not exhibit a MIC value of copper sulfate higher than those of the remaining isolates tested. For all but one mco-harboring S. aureus isolate and the copA-carrying isolate, a plasmid localization of the genes was detected, with plasmids ranging in size between 15 and 25 kb.

PCR amplicons for the zinc (and cadmium) resistance gene czrC were obtained in all three isolates exhibiting MICs of >8,192 μg/ml zinc chloride (Table 2). In these isolates (two MRSA ST398 isolates and the single MRSA ST9 isolate of avian origin), the gene was found to be located in the chromosome. As previously reported by Cavaco and coworkers, the gene czrC is linked to the staphylococcal chromosome cassette mec (SCCmec) element in MRSA CC398 isolates. Thus, the use of zinc chloride in animal production may lead to coselection of methicillin resistance in S. aureus (16, 28).

For comparison, 15 isolates with MICs of biocides far below the above-mentioned values were subjected to PCR analysis. The gene qacG was detected in a single isolate, while qacA/B, qacJ, and qacH were not present in the selected isolates. However, all isolates harbored the genes mepA and sepA, 13 isolates were positive for lmrS and 8 for copA, and 7 isolates each carried mco and norA.

Comparison of MIC values from isolates with and without tolerance genes.

To investigate differences in MIC values between isolates with and without tolerance genes, statistical analysis was performed. However, significant differences were neither detected for zinc chloride and isolates carrying or not carrying czrC (P = 0.22), nor for copper sulfate and isolates carrying the genes copA (P = 0.35) and mco (P = 0.20). For the bisbiguanide chlorhexidine, isolates carrying sepA, norA, and lmrS showed no significant differences in MICs compared to isolates negative for the genes. In contrast, significantly higher MICs were detected for the quaternary ammonium compounds benzethonium chloride and acriflavine and isolates carrying the genes lmrS (P = 0.03) and norA (P = 0.03), respectively, while there was no difference (P > 0.05) in MICs obtained from isolates positive or negative for the gene sepA (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Furthermore, the presence of the genes lmrS, norA, and sepA did not result in significantly higher MICs of benzalkonium chloride or alkyldiaminoethyl glycine hydrochloride (P > 0.05). For the other combinations of biocides and genes, a statistical analysis was precluded due to the low number of isolates positive for the genes or due to the presence of the gene (mepA) in all isolates investigated. Hence, these findings show that the presence of biocide or heavy metal tolerance-mediating genes is not always associated with elevated MICs of the compound. Only for some combinations of biocides and tolerance genes were significantly higher mean MICs detected for carriers (Table S2), indicating that the role of these genes and their interaction remain to be elucidated by including a larger number of isolates.

Conclusion.

In our strain collection, slight but statistically significant differences in the susceptibility to biocides and heavy metal ions have been detected between S. aureus isolates belonging to different major clonal lineages in Germany. However, further investigations are needed to elucidate the role of biocide tolerance-mediating genes and their association with elevated or lowered MIC values of the compounds.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates.

A total of 182 S. aureus isolates from humans (n = 119), animals (n = 59), and the environment of a veterinary practice (n = 4) were included in the study (Table 3). The isolates were part of the strain collections of the National Reference Centre for Staphylococci and Enterococci, Robert-Koch Institute, Wernigerode, Germany, and the Institute for Food Quality and Food Safety, University of Veterinary Medicine Hannover, Foundation, Hannover, Germany. The collection comprised 166 methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and 16 methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) isolates belonging to important human and animal clonal lineages in Germany. The MSSA isolates were included for comparison. The human isolates were collected in the years 2010 through 2011 from diseased and healthy people in Germany and included the following clonal lineages: CC5, CC8, CC22, CC30, CC45, CC80, CC121, ST1, ST7, ST9, ST12, ST15, ST25, ST34, ST59, ST88, ST97, ST101, ST152, ST225, ST398, and ST772 (Table 3). Animal isolates were collected over the past 8 years from diseased and healthy animals and from veterinary clinical settings in Germany and belonged to the clonal lineages ST1, ST9, ST20, ST50, ST97, ST133, ST398, ST425, ST504, ST1380, ST1643, and CC30 (Table 3). The isolates were stored at −80°C as cryopreserved cultures and were grown at 35 ± 1°C overnight on Columbia sheep blood agar (Oxoid, Wesel, Germany) prior to susceptibility testing.

TABLE 3.

Clonal lineages and origins of the MRSA and MSSA isolates used in this study

| MLST type or clonal complex (n) | spa type(s) (no. of isolates) | Origin(s) | Disease/colonization |

|---|---|---|---|

| ST398 (67) | t011 (33), t034 (23), t571 (3), t108 (1), t109 (1), t1451 (2), t1184 (1), t1197 (1), t6867 (2) | 29 poultry, 25 human, 5 pet animal, 1 dairy cow, 3 animal,a 4 veterinary practice interior | Poultry (29 colonized), human (12 diseased, 8 colonized, 5 NDb), pet animal (5 diseased), dairy cow (1 diseased), animal (3 ND), veterinary practice (4) |

| ST225, CC5 (22) | t003 (15), t002 (2), t067 (1), t214 (1), t311 (1), t481 (1), t7333 (1) | 22 human | Human (7 diseased, 3 colonized, 12 ND) |

| CC22 (19) | t005 (3), t022 (1), t025 (1), t032 (10), t1214 (1), t310 (1), t608 (1), t9062 (1) | 19 human | Human (9 diseased, 4 colonized, 6 ND) |

| CC8 (9) | t008 (6), t197 (1), t334 (1), t068 (1) | 9 human | Human (4 diseased, 3 colonized, 2 ND) |

| ST09 (8) | t1430 (7), t587 (1) | 7 poultry, 1 human | Poultry (7 colonized), human (1 diseased) |

| ST15 (6) | t084 (5), t094 (1) | 6 human | Human (5 diseased, 1 ND) |

| CC45 (5) | t015 (1), t303 (1), t004 (1), t1574 (1), t095 (1) | 5 human | Human (5 diseased) |

| ST133 (4) | t1181 (2), t6384 (1), t1403 (1) | 3 wild boar, 1 dairy cow | Wild boar (3 colonized), dairy cow (1 diseased) |

| CC30 (4) | t018 (1), t019 (2), t1347 (1) | 3 human, 1 dairy cow | Human (1 diseased, 1 colonized, 1 ND), dairy cow (1 diseased) |

| ST97 (4) | t267 (1), t224 (1), t359 (1), t521 (1) | 3 human, 1 dairy cow | Human (3 ND), dairy cow (1 diseased) |

| ST7 (4) | t091 (3), t1867 (1) | 4 human | Human (3 colonized, 1 ND) |

| CC80 (3) | t044 (2), t203 (1) | 3 human | Human (3 diseased) |

| CC121 (3) | t159 (1), t435 (1), t8660 (1) | 3 human | Human (1 diseased, 2 ND) |

| ST59 (3) | t163 (1), t437 (1), t216 (1) | 3 human | Human (2 diseased, 1 colonized) |

| ST1 (3) | t127 (2), t922 (1) | 2 human, 1 dairy cow | Human (2 diseased), dairy cow (1 diseased) |

| ST34 (3) | t089 (1), t166 (1), t2080 (1) | 3 human | Human (1 diseased, 1 colonized, 1 ND) |

| ST101 (2) | t056 (1), t150 (1) | 2 human | Human (2 diseased) |

| ST152 (2) | t595 (1), t355 (1) | 2 human | Human (1 colonized, 1 ND) |

| ST425 (2) | t6368 (1), t6782 (1) | 2 wild boar | Wild boar (2 colonized) |

| ST88 (1) | t1814 (1) | 1 human | Human (1 diseased) |

| ST772 (1) | t657 (1) | 1 human | Human (1 ND) |

| ST1643 (1) | t6385 (1) | 1 wild boar | Wild boar (1 colonized) |

| ST12 (1) | t160 (1) | 1 human | Human (1 diseased) |

| ST25 (1) | t078 (1) | 1 human | Human (1 diseased) |

| ST504 (1) | t529 (1) | 1 dairy cow | Dairy cow (1 diseased) |

| ST20 (1) | t1023 (1) | 1 dairy cow | Dairy cow (1 diseased) |

| ST50 (1) | t518 (1) | 1 dairy cow | Dairy cow (1 diseased) |

| ST1380 (1) | t2873 (1) | 1 dairy cow | Dairy cow (1 diseased) |

Animal species not documented.

ND, disease or colonization status not documented.

Susceptibility testing of biocides and heavy metal ions.

Determinations of MICs were performed in single tests in a broth microdilution assay using customized microtiter plates (Merlin Diagnostics, Bornheim-Hersel, Germany). The wells of the microtiter plates were coated with increasing concentrations of vacuum-dried biocides in 2-fold serial dilutions, including the following substances and test ranges: acriflavine, 2 to 256 μg/ml; alkyldiaminoethyl glycine hydrochloride, 0.0625 to 32 μg/ml; benzalkonium chloride, 2 to 256 μg/ml; benzethonium chloride, 1 to 256 μg/ml; chlorhexidine, 0.0625 to 128 μg/ml; copper sulfate, 32 to 8,192 μg/ml; silver nitrate, 0.5 to 64 μg/ml; and zinc chloride, 4 to 8,192 μg/ml. For MIC determinations, inoculum density, growth medium, and incubation times followed the recommendations given in the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) documents M07-A9 and VET01-A4 (38). In brief, a single S. aureus colony was inoculated in sterile sodium chloride solution and adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard. A volume of 50 μl of this suspension was diluted in 10 ml cation-supplemented Mueller-Hinton broth II (BD Diagnostics, Heidelberg, Germany) to achieve a concentration of approximately 5 × 105 S. aureus CFU/ml. Of this suspension, 50 μl was inoculated into each biocide-containing well and the microtiter plates were incubated at 35 ± 1°C. After 18 ± 2 h of incubation, the microtiter plates were analyzed visually and the lowest concentration preventing visible growth of bacteria was defined as the MIC. For quality control, microtiter plates contained the antimicrobial agent ciprofloxacin (test range, 0.015625 to 4 μg/ml) in addition to the panel of biocides. The quality control strain S. aureus ATCC 29213 was used each test day to test if MICs of ciprofloxacin were in the acceptable range. In addition, the Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis strains 7112 (susceptible) and 84482 (with elevated MICs of chlorhexidine, benzalkonium chloride, and acriflavine) were also tested each test day as quality controls. For both strains, MICs for the biocides chlorhexidine, benzalkonium chloride, and acriflavine were previously determined by the broth microdilution and agar dilution methods, and test ranges were compared with previous results (39). Elevated MICs of copper sulfate (≥4,096 μg/ml) and zinc chloride (≥256 μg/ml), for which endpoints of growth were difficult to interpret by broth microdilution due to the color or turbidity of the solved antimicrobial substances in the wells, were confirmed by the broth macrodilution method as described previously (39).

DNA preparation, PCR amplification, and sequence analysis.

S. aureus strains exhibiting elevated MIC values of biocides (isolates with MIC values at the right edge of the distribution; exact MIC values are presented in Results and Discussion) were investigated by PCR amplification for the presence of genes known to confer decreased susceptibility to biocides or heavy metals. For this, total genomic DNA was extracted by using the spin column protocol of the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). PCR amplifications included screening for the presence of the copper resistance genes copA and mco, the zinc and cadmium tolerance-mediating gene czrC, and genes encoding multidrug transporters of the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) (lmrS, norA, and qacA/B), the small multidrug resistance (SMR) family (qacG, qacH, qacJ, and smr), the resistance nodulation cell division family (sepA), and the multidrug and toxic compound extrusion (MATE) family (mepA). All primers used to amplify internal parts of the genes are shown in Table 4, along with the expected sizes of the amplicons and the annealing temperatures. The standard PCR was performed in a volume of 25 μl and included the use of Taq DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany) under the following conditions: an initial cycle of 95°C for 1 min, followed by 30 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at the annealing temperature as specified (Table 4), and 1 min at 72°C, with a final extension step of 72°C for 5 min. The specificity of all PCR amplicons was confirmed by sequencing (Eurofins Genomics MWG, Ebersberg, Germany). For the purpose of comparison, a smaller set of 15 isolates exhibiting lower MICs to all biocides or heavy metals (left edge of distributions) was also included in PCR screening of tolerance-mediating genes.

TABLE 4.

Primer sequences and PCR conditions

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) | Amplicon size (bp) | Annealing temp (°C) | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sepA-f | TGTACTTTCTGGTGCGAT | 176 | 52 | This study |

| sepA-r | GCTCGACTGCAAATATGA | |||

| mepA-f | TGCTATCTCTCTAACACTGCCA | 657 | 56 | This study |

| mepA-r | GCGAAGTTTCCATAATGTGC | |||

| norA-f | GATTGGTGGATTTATGGCAG | 509 | 56 | This study |

| norA-r | TTGTAATGGCTGGTCGTATC | |||

| mco-f | AAATGGCTCCAATGCTCG | 418 | 50 | This study |

| mco-r | ACGGGTGCTTCATACCACTC | |||

| lmrS-f | TGATGTCAATGGTTGGACC | 462 | 58 | This study |

| lmrS-r | AATGCGATGGCGATGTAG | |||

| smr-f | ATAAGTACTGAAGTTATTGGAAGT | 285 | 50 | 40 |

| smr-r | TTCCGAAAATGTTTAACGAAACTA | |||

| qacA/B-f | ATTCCATTGAGTGCCTTTGC | 198 | 52 | 41 |

| qacA/B-r | TGGCCCTTTCTTTAGGGTTT | |||

| qacH-f | CAAGTTGGGCAGGTTTAGGA | 121 | 52 | 41 |

| qacH-r | TGTGATGATCCGAATGTGTTT | |||

| qacG-fw | CAACAGAAATAATCGGAACT | 275 | 48 | 42 |

| qacG-rv | TACATTTAAGAGCACTACA | |||

| qacJ-fw | CTTATATTTAGTAATAGCG | 306 | 48 | 42 |

| qacJ-rv | GATCCAAAAACGTTAAGA | |||

| czrC-f | TAGCCACGATCATAGTCATG | 655 | 56 | 43 |

| czrC-r | ATCCTTGTTTTCCTTAGTGACTT | |||

| copA-f | CATGCTTTAGGCTTGGCAAT | 662 | 55 | 43 |

| copA-r | TCTTCTGGCATGAGTTGTGC |

Southern blotting.

Southern blot hybridization studies were performed with plasmid DNA and EcoRI- and BglII-digested genomic DNA of all isolates positive for one of the PCR-screened biocide or heavy metal tolerance genes. The gene probes consisted of the PCR-amplified internal fragments of the genes and were nonradioactively labeled by using the PCR digoxigenin (DIG) probe synthesis kit according to the manufacturer′s recommendations (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany).

Data evaluation and statistical analysis.

The primary aims of this study were the exploration of MICs and the investigation of differences in MIC values of MRSA and MSSA isolates for eight different biocides. Differences in MICs depending on the origin of isolates (animal or human), their clonal lineage (four lineages analyzed: ST398, CC22, CC5, and ST09), and the presence of specific resistance genes and their origins from diseased or colonized persons/animals were investigated. For this, the MICs were initially log transformed to base 2. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) models were used to analyze the effects of origin and clonal lineage as well as of origin and disease or colonization status of the host. The effects of the presence or absence of specific tolerance-mediating the genes were analyzed with the one-way ANOVA model. Due to the exploratory nature of the experiments, no multiple adjustments were performed and comparison-wise P values were reported. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Inna Pahl and Vera Nöding for excellent technical assistance.

This study was financially supported by the Fritz Ahrberg Foundation, Hannover, Germany, project no. 60070009. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00799-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fluit AC. 2012. Livestock-associated Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Microbiol Infect 18:735–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nübel U, Strommenger B, Layer F, Witte W. 2011. From types to trees: reconstructing the spatial spread of Staphylococcus aureus based on DNA variation. Int J Med Microbiol 301:614–618. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pantosti A. 2012. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus associated with animals and its relevance to human health. Front Microbiol 3:127. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Köck R, Harlizius J, Bressan N, Laerberg R, Wieler LH, Witte W, Deurenberg RH, Voss A, Becker K, Friedrich AW. 2009. Prevalence and molecular characteristics of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among pigs on German farms and import of livestock-related MRSA into hospitals. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 28:1375–1382. doi: 10.1007/s10096-009-0795-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chuang YY, Huang YC. 2015. Livestock-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Asia: an emerging issue? Int J Antimicrob Agents 45:334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Condell O, Iversen CS, Cooney KA, Power C, Walsh C, Burgess U, Fanning S. 2012. Efficacy of biocides used in the modern food industry to control Salmonella enterica, and links between biocide tolerance and resistance to clinically relevant antimicrobial compounds. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:3087–3097. doi: 10.1128/AEM.07534-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDonnell G, Russell AD. 1999. Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action, and resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev 12:147–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerba CP. 2015. Quaternary ammonium biocides: efficacy in application. Appl Environ Microbiol 81:464–469. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02633-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Landelle C, von Dach E, Haustein T, Agostinho A, Renzi G, Renzoni A, Pittet D, Schrenzel J, François P, Harbarth S. 2016. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of polyhexanide for topical decolonization of MRSA carriers. J Antimicrob Chemother 71:531–538. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castellano JJ, Shafii SM, Ko F, Donate G, Wright TE, Mannari RJ, Payne WG, Smith DJ, Robson MC. 2007. Comparative evaluation of silver-containing antimicrobial dressings and drugs. Int Wound J 4:114–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2007.00316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan TV. 2011. Applications of nanotechnology in food packaging and food safety: barrier materials, antimicrobials and sensors. J Colloid Interface Sci 363:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2011.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aarestrup FM, Seyfarth AM, Angen Ø. 2004. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Haemophilus parasuis and Histophilus somni from pigs and cattle in Denmark. Vet Microbiol 101:143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Randall CP, Oyama LB, Bostock JM, Chopra I, O'Neill AJ. 2013. The silver cation (Ag+): antistaphylococcal activity, mode of action and resistance studies. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:131–138. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poole K. 2002. Mechanisms of bacterial biocide and antibiotic resistance. J Appl Microbiol 92:55S–64S. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.92.5s1.8.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawai M, Yamada S, Ishidoshiro A, Oyamada Y, Ito H, Yamagishi JI. 2009. Cell-wall thickness: possible mechanism of acriflavine resistance in meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Med Microbiol 58:331–336. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.004184-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cavaco LM, Hasman H, Stegger M, Andersen PS, Skov R, Fluit AC, Ito T, Aarestrup FM. 2010. Cloning and occurrence of czrC, a gene conferring cadmium and zinc resistance in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus CC398 isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:3605–3608. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00058-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrissey I, Oggioni MR, Knight D, Curiao T, Coque T, Kalkanci A, Martinez JL, BIOHYPO Consortium . 2014. Evaluation of epidemiological cut-off values indicates that biocide resistant subpopulations are uncommon in natural isolates of clinically-relevant microorganisms. PLoS One 9:e86669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furi L, Ciusa ML, Knight D, Di Lorenzo V, Tocci N, Cirasola D, Aragones L, Coelho JR, Freitas AT, Marchi E, Moce L, Visa P, Northwood JB, Viti C, Borghi E, Orefici G, BIOHYPO Consortium, Morrissey I, Oggioni MR. 2013. Evaluation of reduced susceptibility to quaternary ammonium compounds and bisbiguanides in clinical isolates and laboratory-generated mutants of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3488–3497. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00498-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciusa ML, Furi L, Knight D, Decorosi F, Fondi M, Raggi C, Coelho JR, Aragones L, Moce L, Visa P, Freitas AT, Baldassarri L, Fanim R, Vitim C, Orefici G, Martinez JL, Morrissey I, Oggioni MR, BIOHYPO Consortium . 2012. A novel resistance mechanism to triclosan that suggests horizontal gene transfer and demonstrates a potential selective pressure for reduced biocide susceptibility in clinical strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Antimicrob Agents 40:210–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lambert RJ. 2004. Comparative analysis of antibiotic and antimicrobial biocide susceptibility data in clinical isolates of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa between 1989 and 2000. J Appl Microbiol 97:699–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kruk T, Szczepanowicz K, Stefańska J, Socha RP, Warszyński P. 2015. Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of monodisperse copper nanoparticles. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 128:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2015.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDanel JS, Murphy CR, Diekema DJ, Quan V, Kim DS, Peterson EM, Evans KD, Tan GL, Hayden MK, Huang SS. 2013. Chlorhexidine and mupirocin susceptibilities of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from colonized nursing home residents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:552–558. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01623-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghasemzadeh-Moghaddam H, van Belkum A, Hamat RA, van Wamel W, Neela V. 2014. Methicillin-susceptible and -resistant Staphylococcus aureus with high-level antiseptic and low-level mupirocin resistance in Malaysia. Microb Drug Resist 20:472–477. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2013.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Conceição T, Coelho C, de Lencastre H, Aires-de-Sousa M. 2016. High prevalence of biocide resistance determinants in Staphylococcus aureus isolates from three African countries. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 60:678–681. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02140-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagendran V, Wicking J, Ekbote A, Onyekwe T, Garvey LH. 2009. IgE-mediated chlorhexidine allergy: a new occupational hazard? Occup Med (Lond) 59:270–272. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqp042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benjamin B, Chris F, Salvador G, Melissa G, Susan N. 2012. Visual and confocal microscopic interpretation of patch tests to benzethonium chloride and benzalkonium chloride. Skin Res Technol 18:272–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2011.00577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nicholson FA, Chambers BJ, Williams JR, Unwin RJ. 1999. Heavy metal contents of livestock feeds and animal manures in England and Wales. Bioresour Technol 70:23–31. doi: 10.1016/S0960-8524(99)00017-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang F, Li Y, Yang M, Li W. 2012. Content of heavy metals in animal feeds and manures from farms of different scales in northeast China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 9:2658–2668. doi: 10.3390/ijerph9082658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ortega Morente E, Fernández-Fuentes MA, Grande Burgos MJ, Abriouel H, Pérez Pulido R, Gálvez A. 2013. Biocide tolerance in bacteria. Int J Food Microbiol 162:13–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leelaporn A, Paulsen IT, Tennent JM, Littlejohn TG, Skurray RA. 1994. Multidrug resistance to antiseptics and disinfectants in coagulase-negative staphylococci. J Med Microbiol 40:214–220. doi: 10.1099/00222615-40-3-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piddock LJ. 2006. Clinically relevant chromosomally encoded multidrug resistance efflux pumps in bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev 19:382–402. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.382-402.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu Q, Zhao H, Han L, Shu W, Wu Q, Ni Y. 2015. Frequency of biocide-resistant genes and susceptibility to chlorhexidine in high-level mupirocin-resistant, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MuH MRSA). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 82:278–283. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vali L, Davies SE, Lai LL, Dave J, Amyes SG. 2008. Frequency of biocide resistance genes, antibiotic resistance and the effect of chlorhexidine exposure on clinical methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother 61:524–532. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wassenaar TM, Ussery D, Nielsen LN, Ingmer H. 2015. Review and phylogenetic analysis of qac genes that reduce susceptibility to quaternary ammonium compounds in Staphylococcus species. Eur J Microbiol Immunol 5:44–61. doi: 10.1556/EuJMI-D-14-00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noguchi N, Suwa J, Narui K, Sasatsu M, Ito T, Hiramatsu K, Song JH. 2005. Susceptibilities to antiseptic agents and distribution of antiseptic-resistance genes qacA/B and smr of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated in Asia during 1998 and 1999. J Med Microbiol 54:557–565. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45902-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Narui K, Noguchi N, Wakasugi K, Sasatsu M. 2002. Cloning and characterization of a novel chromosomal drug efflux gene in Staphylococcus aureus. Biol Pharm Bull 25:1533–1536. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skovgaard S, Larsen MH, Nielsen LN, Skov RL, Wong C, Westh H, Ingmer H. 2013. Recently introduced qacA/B genes in Staphylococcus epidermidis do not increase chlorhexidine MIC/MBC. J Antimicrob Chemother 68:2226–2233. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2013. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk and dilution susceptibility tests for bacteria isolated from animals. Approved standard VET01-A4 and M07-A9, 4th ed CLSI, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rensch U, Klein G, Schwarz S, Kaspar H, de Jong A, Kehrenberg C. 2013. Comparative analysis of the susceptibility to triclosan and three other biocides of avian Salmonella enterica isolates collected 1979 through 1994 and 2004 through 2010. J Food Prot 76:653–656. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Couto I, Costa SS, Viveiros M, Martins M, Amaral L. 2008. Efflux-mediated response of Staphylococcus aureus exposed to ethidium bromide. J Antimicrob Chemother 62:504–513. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sidhu MS, Heir E, Leegaard T, Wiger K, Holck A. 2002. Frequency of disinfectant resistance genes and genetic linkage with beta-lactamase transposon Tn552 among clinical staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:2797–2803. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.9.2797-2803.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bjorland J, Steinum T, Kvitle B, Waage S, Sunde M, Heir E. 2005. Widespread distribution of disinfectant resistance genes among staphylococci of bovine and caprine origin in Norway. J Clin Microbiol 43:4363–4368. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.9.4363-4368.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gomez-Sanz E, Kadlec K, Fessler AT, Zarazaga M, Torres C, Schwarz S. 2013. Novel erm(T)-carrying multiresistance plasmids from porcine and human isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus ST398 that also harbor cadmium and copper resistance determinants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3275–3282. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00171-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.